The

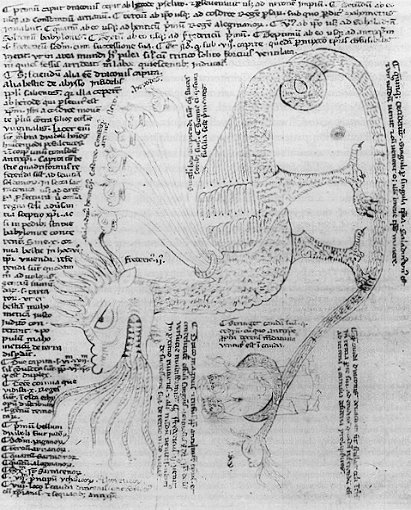

starting point for the following observations is a problematic feature

of a visual representation of the apocalyptic dragon in a Prague manuscript

from the middle of the 14th century (Fig. 1).[1]

In this manuscript the seven heads of the dragon bear the names of seven

evil rulers. The first four are Herodes, Nero, Constantius

and

Cosdroe, the last two Saladinus and Federicus IIus.

The fifth in the series, however, is HenricusIus, "Henry

the First". The identification of all these rulers with the heads of the

dragon characterizes them unmistakably as negative figures. In the case

of Herod and Nero this can be readily understood. Constantius has

been given the epithet Arianus by a marginal gloss and can, therefore,

easily be identified as Constantius II (337-361), a wayward son of the

Emperor Constantine the Great in the eyes of his Athanasian opponents[2],

and a man whose classification as a heretic branded him as diabolical in

the medieval world-view. The Persian King Chosroe II (591-628) is a virtually

unknown entity in the historical consciousness of today, but for educated

people in the Middle Ages his notoriety was firmly established. He had,

after all, conquered and destroyed Jerusalem in 614, carrying off to his

heathen kingdom for a time the true cross of Christ, which had been so

miraculously rediscovered by the Empress Helena three centuries before[3].

The Muslim Saladin, the destroyer of the first kingdom of Jerusalem, was

the unquestionable enemy of Christ and God, and as (292 Plate, 293)such

required no further attributes in order to be recognized as a negative

figure[4].

And it is a well-known fact that Frederick II was only seen by his loyal

Hohenstaufen followers as a shining light, his enemies condemning him as

the incarnation of Antichrist[5].

But how does Henry "the First" fit into this notorious company?

And

which Henry is meant, anyway? In modern historical writing the ordinal

number "the First" customarily refers to King Henry, the founder of the

Liudolfing dynasty of the Saxon emperors, and the text accompanying the

figure of the dragon seems to confirm this identification, as it accords

Henry the title of "rex"[6].

One might almost be tempted, therefore, to see in the designation of this

"first" Henry as one of the heads of the apocalyptic dragon a late revenge

for King Henry's much-discussed rejection of the anointment at his coronation,

reported by Widukind of Corvey[7]

and highly praised in modern times by a certain branch of German historical

research on account of its supposedly anticlerical nature[8].

An identification of the fifth head of the dragon with the first Saxon

king can even be found, as it seems, among medieval authors[9],

long before it became an established fact in some works of modern historiography[10].

But, on closer consideration, this idea must be abandoned. For in the (294)

context

of the tradition in which this figure of the apocalyptic dragon occurs

it is absolutely clear that the fifth head of the dragon cannot be linked

with this Henry.

The

representation of the dragon occurs in the midst of a sequence of diagrams,

so-called Figurae, in the tradition of Joachim of Fiore, which serve to

facilitate the understanding of certain basic concepts in the historico-theological

speculations of the Calabrian abbot and his disciples by presenting them

visually[11].

Now, in relevant passages of the work of Joachim our "Henricus primus"

is described as an "imperator", that is to say, as the first emperor of

this name. In a history of the Church which is envisaged as a series of

seven calamities occurring since the birth of Christ Henry is cited as

a contemporary of the popes Sylvester II, John XVII and XVIII, Sergius

IV and Benedict VIII, and as such marked as the emperor whose rule announces

the beginning of the fifth age of affliction, when emperors of German origin

robbed the Chruch of its freedom and led it into a new Babylonian Captivity[12].

The "Henry the First" of our figure of the dragon is not, or at least originally

not, therefore, the founder of the Liudolfing dynasty, who never wore the

imperial crown and is as a rule ignored in the catalogues of popes and

emperors of the High Middle Ages, particularly in those of Italian provenance[13].

It is, rather, his great-grandson of the same name, who is generally counted

as "the Second" in the series of German Henries.

The

attribution of the ordinal number "the First" to the second Henry was not

a quirk of the imagination of Joachim or his disciples. Medieval scholars

were perfectly capable of distinguishing between an "emperor" and a "king"[14].

But occasionally the distinction was ignored. One need only recall the

"R(ex)" Constantine and the "Rex" Charlemagne of the Triclinium mosaic

of the Lateran Palace[15]

or the lack of clarity (295) in King/Emperor Conrad III's use of

the title "rex Romanorum augustus" vis-à-vis the Basileus, whose

title for its part could be translated into Latin with either "rex" or

"imperator"[16].

It would not be surprising, therefore, if even in the Middle Ages not everyone

who contemplated our dragon clearly understood which Henry was originally

meant by its fifth head.

Now,

there can be no doubt that the so-called Imperial Church System reached

its peak under Henry II, and that no other ruler was as capable of using

the imperial church so efficiently[17].

Historically, therefore, it seems only too justifiable to regard him as

the gravedigger of the "Libertas ecclesiae", a word which was to become

the battle cry of ecclesiastical reform during the Investiture Contest[18].

But this same Henry II had also donated many imperial and royal lands for

the creation of pious foundations, among whom the Bishopric of Bamberg

was the most outstanding, and this was a source of profound concern for

imperially-minded contemporaries[19].

And this same Henry had been a model of Christian virtue, leading the married

life of a Joseph, as was said, with his wife Kunigunde, who was canonized

in 1200[20].

He himself had been canonized earlier, in 1146, and the cult of his person

was well-established by the time Joachim of Fiore declared him a member

of Satan's brood[21].

Joachim's ver(296)dict must, therefore, surprise us. For Henry had

been declared a saint by a pope, Eugenius III, and hence by an institution,

on whose authority Joachim had never cast even the shadow of a doubt. Moreover,

from an ecclesiastical point of view, Henry was portrayed positively both

by his contemporaries and later writers[22],

in contrast to Henry IV, Henry V and even Henry III, to say nothing of

Frederick Barbarossa, Henry VI or Frederick II. What, then, persuaded Joachim

and his circle to go against the public esteem for the holy Emperor Henry

"the First" and to make him one of the heads of the apocalyptic dragon?

It

is the object of the following presentation to clarify this question by

considering three points:

-(I)

Firstly the role of the Emperor Henry "the First" in the work of Joachim

of Fiore will be discussed.

-(II)

Secondly it will be shown that this is only possible in the context of

a consideration of the role of the Roman Empire as such under its German

rulers in the eschatological scheme of Joachim.

-(III)

Finally, the development of Joachim's concept of the German-Roman Empire

and of its representative figure, the Emperor Henry "the First", in the

eschatological tradition founded by Joachim will be examined.

As

sources both texts and figures will be drawn upon; the questions posed

relate to the Roman Empire from a late Hohenstaufen Italian perspective.

I can well imagine that Robert Benson would have appreciated the questions

set, the materials and the method.

I

How

then is the Emperor Henry "the First" presented in the works of Joachim

of Fiore? The question is not easy to answer, and the answer itself is

by no means unambiguous. The uncertainties begin with the canon of the

works of Joachim which can be unquestionably classified as genuine. As

we have seen, the Emperor Henry "the First" occurs as one of the heads

of the dragon of the Apocalypse in visual records, and the figure presented

at the beginning, in which the Emperor Frederick II is the seventh head,

that is the final Antichrist, is in this form certainly not an authentic

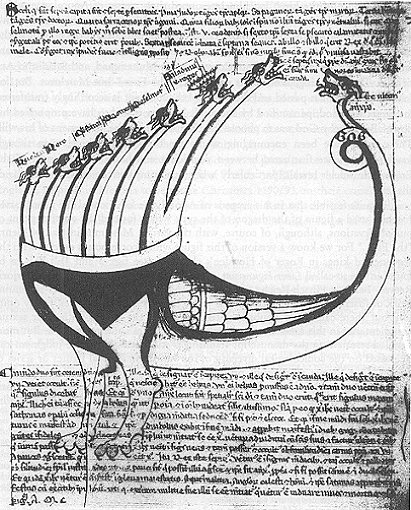

work of Joachim's. But Leone Tondelli has already pointed out quite correctly

that the list of rulers associated with the dragon's heads in our figure,

which is part of a widely disseminated type known to Tondelli from the

manuscript Vat. lat. 3822 (see fig. 2), is, with the exception of Frederick

II, based upon unquestionably authentic works of the Calabrian abbot[23].

These are the "Concordia Novi ac Veteris (297 Plate, 298) Testamenti"

and the Commentary on the Apocalypse, the two major works of Joachim in

regard to scope, significance and impact.

In

the "Concordia" Joachim presents in all its complexity his own particular

historico-theological concept of an historical parallelism between the

Old and the New Testaments, with 42 generations each, extending from Jacob

to Jesus Christ and from the birth of Christ, as Trinitarian speculations

indicate, to the dawn of a millenarian-like age of peace; there are overlapping

time zones of beginning (initiatio), fruitfulness (fructificatio)

and end, or, more properly, "completion" (consummatio) for each

period[24],

with quasi cyclical sequences of ages of peace and crisis in which periodization

patterns taken from the tradition of biblical exegesis are interpreted

according to number symbolism, with intertwined binary, ternary, quaternary,

septenary and decenary numbers[25].

In one of the septenary sequences, oriented on the seven seals of the Apocalypse,

Joachim interprets the effects of the divine will on the historical scene

as a series of seven calamities[26],

beginning in the Old Testament with the conflicts of the Egyptians with

the children of Israel; the parallel in the New Testament is the conflict

of the Early Church with the Jews. Under the fifth seal the relationship

between the Jewish kings of the Old Testament and the rulers of Babylon

has its parallel in the relationship between the popes since Zacharias

and the Franconian or German rulers. This relationship was a happy one

initially, at the time of the Franconian rulers, and, especially, Charlemagne

and the Ottonians, but since the times of the ‘German’ Emperor Henry "the

First" the Church was in distress[27].

Elsewhere in the "Concordia" the period of the Emperor Henry "the First"

is (299) specified by the position of the ruler within a catalogue

of popes and emperors in such a precise manner that, as has been said above,

there can be no doubt about the identity of that Henry[28].

Joachim's

Commentary on the Apocalypse at first confirms this picture. In the so-called

"Liber introductorius in Apocalypsim", in which Joachim presents his hermeneutic

principles before beginning with the actual interpretation verse by verse,

he outlines the same pattern of periods based on the seven seals as in

the "Concordia", but with a number of clarifications and shifts of emphasis.

For example, he explicitly stresses the fact that the period of the fifth

seal stretches from Charlemagne to his own time (although "his own time"

can be taken with a grain of salt and can continue substantially beyond

his own lifetime), that the Old Testament parallel is the period of Chaldean

rule in Babylon, when the Jewish kingdom - in this context the typological

symbol for the Church - was destroyed. Above all, however, Joachim states

more specifically his complaints about the "distress" of the Church in

this period: secular princes, Christian in name only, and in reality worse

than the godless heathen peoples, tried to deprive the Church of its freedom

and to steal from it wherever they could. These are the classical themes

of the time of the Investiture Contest. The origin of these lamentable

conditions is, however, transferred quite emphatically to the times of

the Emperor Henry "the First"[29].

The

septenarian pattern and its analogues, the seven seals and the seven heads

of the dragon, are, of course, often drawn upon in Joachim’s commentary

on the Apocalypse. There is never any doubt that Herod, Nero, Constantius

Arianus, the Persian king Chosroe - whose place can be taken by the prophet

Mohammed, so to speak as Chosroe's heir[30]-

and Saladin as the sixth in the series represent the periods before the

first appearance of Antichrist and the subsequent Sabbath Age. But the

text quoted above is the only one which explicitly links the fifth epoch

with the Em(300)peror Henry "the First". Elsewhere the attribution

remains rather indefinite. The fifth head of the dragon could be, without

any name being mentioned, "one of the kings of the new Babylon", who, like

Lucifer, desired to sit upon the "mountain of the Testament" and to be

like God[31].

This sounds as if it were the perverted version of the vicarius Dei aspect

of the German imperial idea[32]!

The interpretation of Apocalypse 17, 8-10 is similarly indefinite in regard

to the person responsible, but all the more concrete in regard to the evils

suffered at his hands by the Church. Here seven heads, seven mountains

and seven kings are treated - the fifth king being described as the first

ruler to begin driving the Church in the West to its ruin by means of the

institution of lay investiture[33].

This is a further unequivocal reference to the themes of the Investiture

Contest, in which the right of the secular powers to intervene in the religious

sphere was seen as the greatest evil of the time. One last example: in

a sequence of pairs contrasting the shining lights of the Old Testament

with the shadowy figures of the New, in which Adam and Herod, Noah and

Nero, Abraham and Constantius Arianus, Moses and Mohammed, John the Baptist

and an unspecified eleventh king of Daniel's prophecy (usually Saladin)

form type and anti-type, King David is contrasted as a person with the

"King of Babylon" as an institution[34].

The

tendency to view the Roman Emperors of German origin as a collective entity

and not to blame their evil deeds on a single individual, and certainly

not on the holy Emperor Henry "the First", can be found already in the

"Concordia", which Joachim had finished writing in 1196 before the Commentary

on the Apocalypse, which he worked on at least until 1198/1199[35].

Here there is a remarkable uncertainty in re(301)gard to the threshold

for the beginning of the tribulations of the Church. Competing for acceptance

with the text referring to the Emperor Henry "the First" is a second text

which formulates the conflicts with the Church in a similar way, but attributes

them to a "King Henry" who is a contemporary of Leo IX, and can, therefore,

only be the Salian Henry III[36].

We can conclude, therefore, that Joachim's aim was not to establish a causal

relationship between one particular Henry and the ecclesiastical crisis

of his time, but to brand the entire period in which the German emperors

ruled as unholy[37].

Obviously none of them had in his eyes a so obviously negative profile

as Herod, Nero, the ‘Arian’ Constantius II, Chosroe/Mohammed or Saladin.

This

is also expressed in a further variation on the sequence of seven rulers.

In the interpretation of Apoc. 6.9, which deals with the opening of the

fifth seal, Joachim outlines a model of the persecution of the Church which

is primarily geographical in orientation, although it also includes a historical

periodization. He places the first persecution in Palestine (which calls

to mind Herod), the second in Rome (which corresponds with Nero), the third

in Greece (usually the position of Constantius Arianus), the fourth in

Arabia (which refers to Mohammed), the fifth, however, not in the Holy

Roman Empire, but in Mauritania and Spain. And for these regions Joachim

also mentions the name of a new ruler: Meselmutus[38].

This

(302) seems to be none other than the Almohad Mahdi Ibn Tumart

(died 1130)[39],

a Masmuda Berber (hence obviously the corruption of his name), whose successors

‘Abd al-Mu’min (1133-1163), Abu Ya‘qub Yusuf (1163-1184) and Abu Yusuf

Ya‘qub al-Mansur (1184-1199) conquered the whole of North Africa and Muslim

Spain, overawed the Christian kingdoms of the Iberian peninsula and, at

the battle of Alarcos in 1195, even succeeded for a while in bringing the

Reconquista to a standstill. The acute distress of Christian Spain, which

Joachim had heard about and which led him to see the threat of Islam as

persisting continuously from Mohammed, the representative of the fourth

period of persecution, to Saladin, the representative of the sixth, is

reflected in this variant of his scheme of Church history.

The

‘Meselmut’ variant achieved a certain degree of prominence, when the rulers

of the Western kingdoms, Philip II Augustus of France and Richard the Lionheart

of England stopped in Messina to celebrate Christmas 1190/91 on their crusade

to the Holy Land. Here a memorable encounter between Richard the Lionheart

and Joachim of Fiore took place, which is reported by the chronicler Roger

of Howden[40].

(303)

In

the presence of the king Joachim interpreted those verses of the Apocalypse

which had led him to develop in his commentaries his model of the seven

royal dragon's heads responsible for the seven periods of persecution inflicted

on the Church in the course of its history and threatening it in the immediate

future. The seven kings are familiar to us, from Herod to Nero, Constantius

to Mohammed and Saladin to Antichrist. The fifth king, however, is not

Henry "the First", but ‘Meselmut’. But for Joachim his time has passed

and the threat of the moment is accordingly transferred to the sixth period,

personified by Saladin[41].

Joachim is said to have prophesied his downfall, whereby God was to choose

the English king as the instrument of His will. These must have been encouraging

words for the crusader king, even though Joachim's audience fluctuated

between scepticism and hope, as the report of the English chronicler reveals,

particularly when one compares the varying versions of the text.

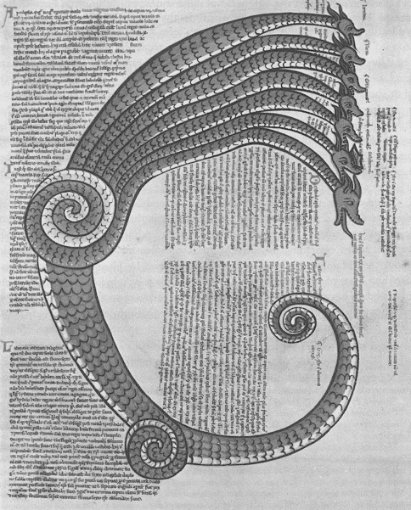

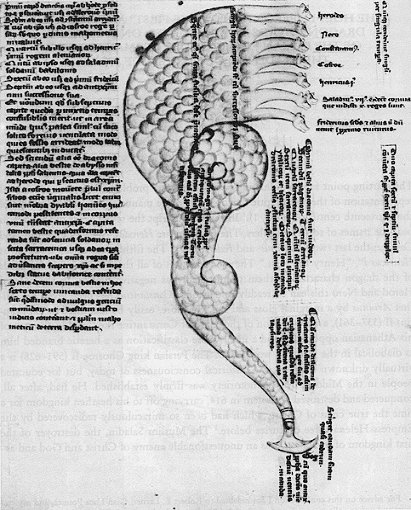

It

is quite feasible that in his exegesis of the Apocalypse for Richard the

Lionheart Joachim used a figure of the dragon of the type which formed

the starting point of our observations, although, of course, with the variant

‘Meselmut’ instead of Henry "the First". For we know a version of this

figure which corresponds exactly with the sequence of kings in Roger of

Howden's chronicle (see figs. 3 and 4)[42].

It is to be found in the so-called "Liber Figurarum", which, according

to the research of Marjorie Reeves, Beatrice Hirsch-Reich and Leone Tondelli,

is regarded as a genuine work of Joachim's[43].

The final word has yet to be spoken in this matter, in my opinion, but

there can be no doubt that the totality of the figures with their textual

commentaries in this "Liber" are closely related to Joachim´s authentic

work. But more detailed research on the manuscript tradition is still necessary,

before judgement can be passed on the codicological diversity of the various

individual figures or series of figures. Our Prague manuscript provides

an illustrative example. The type of sequence in it clearly shows signs

of post-Joachimist revision[44],

and yet Marjorie Reeves rightly emphasizes that elements of the genuine

Joachim are handed down in (304-5 Plates, 306) it[45];

she even argues that this later series of illustrations, which historical

research has named "Praemissiones" because it usually precedes the pseudo-Joachimist

Commentary on Isaiah[46],

makes use of draft versions which seem to be older than the "Liber Figurarum"[47].

It seems, therefore, fitting to discuss the sequences of ‘figurae’ preserved

in the "Liber Figurarum" or the "Praemissiones" as a unit, regardless of

the differences in kind, time, and, in view of Joachim, authenticity.

It

should be noted in this connection that the tradition of illustration accompanying

Joachim's exegesis of the seven-headed dragon of the Apocalypse occurring

in the "Liber Figurarum" found its way into the Italian chronicles in the

1280's through the works of Salimbene of Parma and Albertus Milioli of

Reggio Emilia[48].

Even earlier, around 1255, the type of figure of the dragon known from

the "Praemissiones" can be found in theological literature in a distinctio

on Antichrist written by the Franciscan Thomas of Pavia[49].

The

development and tradition of alternative models for the fifth royal head

of the apocalyptic dragon, with, on the one hand, the threat posed by the

German kings and emperors to the internal constitution of the Church, and,

on the other, the external threat emanating from the Saracens, complements

the observations made about the instability of the role of protagonist

played by Henry "the First" or indeed any other particular persons as the

rulers of the new Babylon in the fifth epoch of Church history. The contribution

of a particular ruler to the events of the age which was to be symbolized

by his name was, for Joachim, evidently not decisive. What mattered to

him was the overall character of an entire epoch. Hence, Henry (307)

"the

First", who normally occurs as Henry II in the list of rulers, could change

places with his namesake Henry III; or the position of representative of

the epoch could be left unfilled, or the source of threat in its entirety

could be changed, with Muslims replacing Germans and a ‘Meselmut’ substituting

for Henry "the First"[50].

This process can be observed elsewhere as well, when, for example, the

prophet Mohammed replaces the Persian king Chosroe[51]

or the Arian barbarian kingdoms of the Goths, the Vandals, and the Lombards

take the place of Constantius Arianus[52].

It is also in evidence in explicit remarks to the effect that the individual

protagonist alone does not personify an epoch; he does so only together

with his successors[53].

Joachim's tentative attempts to identify the rulers who would persecute

the Church in the sixth epoch, of which he felt himself to be on the threshold,

or even in the future seventh epoch[54],

can also be mentioned in this context. It is, in general, characteristic

of Joachim's historico-theological thinking that he does not lose himself

in details, but tries to name fundamental conditions[55].

For him history had a meaning only in a very global sense, as the place

for the implementation of the divine will. Human beings and, specifically,

rulers as the protagonists of history were as such unimportant. They merely

possessed a symbolic function within a greater framework of historical

epochs and were accordingly interchangeable.

One

should not, therefore, be disturbed by the fact that Joachim did not assign

to Henry "the First" the role of representative of the fifth epoch of tribulation

in the history of the Church in all the relevant passages in his work.

He did at least always mean him with the title "the First". One could in

any case make no greater mistake than to try to harmonize all the elusive

statements about the person of the representative of an age, reducing them

to a common denominator. Nor does Joachim really contradict himself. He

is constant in the substance of his statements, varying only the accidentals.

(308)

But

regardless of the mutability of details, one must, nevertheless, ask how

precisely the holy Emperor Henry "the First" could become the typical representative

of a power repressing the Church. Why, for example, did not Joachim choose

one of the Ottonians or a Salian in his place? He could easily have done

so! His sequence of historical ages by no means involved only one vale

of tears after the other, which the Church must continually pass through

in the course of its history. In his concept of history, rather, persecutions

alternated with times of peace, periods of decline with golden ages, in

an almost cyclical way. The one is in fact the prerequisite for the other[56].

Each age begins with a period of order and stability, which then is followed

by a period of crisis, and when this is overcome the process begins again

from the start. Hence the foundation of a new Church by Christ is followed

by the Jewish persecution in the time of the apostles, the expansion of

the early Church throughout the entire Roman Empire leads to the persecution

of the Christians by Nero and his successors; and after this is overcome

with the conversion of Constantine the Great by Pope Sylvester, the Church

takes on leading functions within the State, which in turn endanger it,

when it permits the domination of Arian heretics; this then provoked divine

punishment in the shape of Chosroe's Persians and Mohammed's Saracens,

until the alliance of the Franconian rulers with the Papacy from the times

of King Pepin and Pope Zacharias, and particularly since Charlemagne, and

the transfer of the Empire to the Germans at the time of Otto I led to

a felicitous age for the Church. A new turn for the worse was inevitable

according to this scheme, but nothing really forced Joachim to let it take

place in the age of the Emperor Henry "the First", so that Saladin's deeds

could be understood as a scourge of God and the approaching catastrophe

placed in the sixth epoch, which was to be followed by the seventh and

final age on earth with the prospect of a sabbatical period of spiritual

illumination and peace.[57]

Why, therefore, did he make just this choice?

One

reason might have been that Joachim had restricted his freedom of choice

by the use of mechanically applied numerical series of generations lasting

thirty years for the division of the ages; and according to this method

of calculation the moment of crisis in the fifth period should have occurred

during the rule of the Emperor Henry "the First" which roughly marked the

middle between the reign of the early (309) Carolingians and the

end of their and their German successors’ realm as predicted by Joachim

of Fiore[58].

But that alone could hardly have persuaded Joachim to allow the tribulations

of the fifth age to begin precisely with this emperor, if he had not had

other substantial reasons for the choice. For he was always generous in

setting the limits of tolerance for his calculations[59].

It must, rather, be the case that he was acquainted with traditions in

which the Emperor Henry "the First" appeared in an unfavourable light.

It is at present not possible to say exactly what these traditions might

have been, as insufficient research has been done on the sources of Joachim's

historical knowledge. It can be assumed that for his plan of the ages divided

according to sequences of generations he drew upon a catalogue of popes

and emperors which had been popular since the time of Hugh of St Victor,

particularly among the Italian chroniclers[60].

But such catalogues hardly ever contained details about events during a

period of rule or evaluations of the government of a ruler. Joachim must,

therefore, also have had access to more substantial historical works. As

has been said, however, there is a need for clarification here. At the

moment one can only say that the works must have contained information

on the later period of Saxon rule similar to that found in the "Honorantiae

civitatis Papiae" or the Tiburtine Sibyl[61].

Here, as a reaction against the regime of Theophanu and the elements of

a rule of terror imposed on Rome for a time by Otto III, and also against

the Saracen threat to Southern Italy at the time of our Henry "the First",

a truly grim picture of the rule of a German emperor at the turn of the

first millennium is painted from an Italian point of view. In contrast

to Nero, Henry "the First" is, apart from the ominous prospects of his

rule, not made personally responsible for the disasters during his reign,

and, in spite of all the criticism, the statements of the Tiburtine Sibyl

and the "Honorantiae" are too few and too flimsy to be evaluated as evidence

of an established tradition determining the historical interpretation of

an age. But they do provide proof (310) that a tradition with a

strongly negative assessment of the time of Henry "the First" at least

existed in Italy, which cannot be said of German historiography[62].

II

Although

the personal responsibility of the Emperor Henry "the First" for Joachim

of Fiore's negative view of the age of world history beginning with the

German emperors may have been negligible, the Roman Empire under German

rule which should eventually lead to a quasi millennarian kingdom of peace

was, nonetheless, for Joachim unquestionably a negative force[63].

From the point of view of the customary eschatological tradition this need

not necessarily have been the case. It is no matter whether we take the

Pseudo-Methodius, Adso of Montier-en-Der, the Tiburtine Sibyl or, in Joachim's

own time, the magnificent Hohenstaufen "Ludus de Antichristo"[64],

to name only the most important writings of this genre: all the eschatological

texts before Joachim assigned to the Roman Emperor as the Last World Emperor

the role of the ‘Katechon’, the bulwark against the evil forces, who would

depose his crown on the altar of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem,

and, of all the Christian powers, would resist Antichrist most manfully,

until he was forced to submit to the unleashed forces of Hell, after which

the true Christ would appear, announcing for all mankind the beginning

of eternity and the end of all tribulations[65].

But for Joachim Henry "the First" and the empire he embodies is a satanic,

anti-Christian power, without any positive features apart from its involuntary

function as the scourge of God in the fulfilment of the divine plan of

salvation[66].

This is without doubt a new accent in the eschatological tableau of the

medieval world-view. (311)

It

would be, however, an exaggeration of the significance of the German-Roman

Empire in Joachim's view of history, if we forgot that, in spite of all

the potential power of the Empire for the oppression of the Church, Joachim

saw its influence as limited only to the secular field and located the

true source of the sufferings of the Church at a higher level, namely in

its general moral and spiritual decay.

He

presents variations on this idea at different places in his commentary

on the Apocalypse. I will pick out one of them from the "Liber introductorius

in Apocalypsim"[67].

Here Joachim explains that the final, that is to say the sixth age beginning

with the incarnation of Christ follows the seven days of creation in its

structural development, with six days of labour and toil and one day of

rest and peace. In accordance with this scheme of the historical process

Joachim assigned to the six "working days" - which can be equated with

six ages of trials and tribulations - five orders of the Church, whose

essence he had deduced from certain sections of the Apocalypse. In each

of the first five ages he envisaged a dominant order of the elect opposing

a specific evil power, whereas in the sixth age all the forces of good

and evil are engaged in battle[68].

The first of these orders of the elect is the Ordo apostolicus, whose members,

the bishops of the first seven patriarchal churches, fought against the

"synagoga Iudeorum"; the second is the Ordo martyrum, which suffered under

the persecution of heathen idolaters; the third is the Ordo doctorum, which

took up the struggle against the Arian heretics; the fourth is the Ordo

virginum, which was persecuted by the Saracens[69].

Joachim's views on the fifth order vary. On the one hand it is the Roman

Church, in the spiritual sense the heavenly Jerusalem, or the community

of the faithful in the kingdom of God, who fight against the ‘new Babylon’,

and specifically against the might of the German-Roman Empire, whose spiritual

properties are judged to be diabolical. On the other hand, in a more sublime

sense this Ordo is the Church as a whole, which is involved in conflict

with the community of the reprobate[70].

(312)

This

is not the only place in which the idea is expressed that the history of

the world is a reflection of the cosmic struggle between God and Satan

and that the historical personages are merely the protagonists of celestial

forces, which simply change their outward shape and the field of battle.

Hence, the material substance of historical conflicts can be stripped of

all individuality and reduced to a general basic pattern of good and evil

actions[71].

Joachim's

speculative shift to a general level to which the individual historical

figures are related and from which they acquire their significance within

the divine plan was not without consequences for the actual historical

personages in his concept of history. The transfer of the paradigm of persecution

from the secular to the spiritual level of cosmic opposition between the

civitas terrena and the civitas caelestis, to use Augustine's concepts,

had a levelling effect upon all the occurrences of external hardship experienced

by the Church. The historical events were only variables, the constant

being the permanent conflict between God and Satan. So nothing was lost

in regard to the substance or accuracy of a statement if the players on

the stage of history changed their roles and if completely different historical

individuals were accorded the same timeless significance. For Joachim it

was a matter of indifference whether the German-Roman Empire or the empires

of Islam from Mohammed to ‘Meselmut’ and Saladin were to be regarded as

the appointed enemies of the Church in the fifth age of the New Testament.

In the final analysis he could forego the use of (313)

such historically

significant secular figures altogether and transfer the history of this

time entirely to the inner space of the Church, where all that matters

is whether every individual leads a good or bad life and observes or disobeys

God's commandments. The reason for the easiness of change in the specific

choice of content filling up the general frame could be seen as originating

from the different levels of sense required by the principles of biblical

exegesis which Joachim used for his historico-theological thinking. According

to such a scheme the Emperor Henry „the First“ or ‘Meselmut’ would fit

the sensus historicus or litteralis, the clerics and monks the tropological

or moral sense, and the concept of the Church in general as opposed to

the reprobates clearly has anagogic character.

III

Somewhere

between the political interpretation of the fifth age as a conflict between

the Roman kings and emperors of German origin on the one hand and the popes

and other prelates as the defenders of the ‘Libertas ecclesiae’ on the

other and the spiritual interpretation of the opposing parties as "filii

Babylonis"

and "filii Ierusalem" there is a semi-political, semi-spiritual interpretation.

This is the equation of the Church at large (generalis ecclesiae),

with the secular clergy and the canons regular as the forces on the side

of God and apostates from the Church's own ranks as the quasi-Babylonian

enemies of God[72].

This

pattern of interpretation leads directly to one of the two eschatological

traditions established by the successors of Joachim, to which we will now

turn. This tradition is associated with the names of the Spiritual Franciscan

Petrus Johannis Olivi and his disciple Ubertino da Casale.

In

his commentary on the Apocalypse concluded in 1297 Petrus Johannis Olivi

made substantial use of the spirit and the letter of Joachim's work[73].

Occasionally he (314) drew upon pseudo-Joachimist writings[74],

but he borrowed mainly from the genuine works, i.e. the "Concordia" and

the commentary on the Apocalypse. From these sources Henry "the First"

as the protagonist of the threat to the Church emanating from the German-Roman

Empire also found his way into Olivi's commentary on the Apocalypse. It

speaks, moreover, for the thoroughness of Olivi's reading of Joachim that,

although he fails to mention ‘Meselmut’, he did not suppress the Muslim

variant of persecution in the fifth age, even though it is not in the foreground

of Joachim's treatment[75].

Petrus

Johannis Olivi does not merely adopt Joachim's ideas; he transforms them

quite substantially. In the end, the pattern of history in his work is

completely different in structure and accentuation. Olivi does take over

Joachim's scheme of the seven ages of tribulation of the Church, which

of course is oriented on the number symbolism of the Book of Revelation,

and he refers again and again to the pattern of the ages together with

the names of the evil rulers and peoples assigned to them. But for him

these are only loose temporal and biographical starting points for his

interpretation. According to Olivi the history of the Church is less a

chain of external catastrophes and more a process of inner decay. His treatment

of the first three ages of the Apostolic and Primitive Church with its

persecutions by Herod's Jews, the age of the martyrs with the persecutions

of Nero's heathens and the age of doctrinal disputes with the heretical

followers of Constantius Arianus corresponds thoroughly with Joachim's

ideas. But their conceptions begin to differ with the fourth age. Joachim's

rich and variable range of possible applications of the paradigm of the

persecution of the Church is radically narrowed down to the aspect of its

inner decay. For Olivi, the fourth age is reduced to the time of the anchorites,

symbolized by St Anthony and St Paul the Hermit. The fifth age is the age

of the Vita communis of monks and secular clergy, who had in part modelled

their lives on strict guiding principles, but had also partly compromised

those principles by accepting worldly possessions. For this last-mentioned

kind of imperfect spiritual life the key word is "condescensio"[76].

(315)

We

have seen that Joachim had already formulated this view, but only as one

of several possible interpretations. For Olivi it is the only interpretation.

Olivi opens the fifth age in almost the same way as Joachim with Charlemagne,

who is shown to have endowed the Church generously with secular goods.

For Olivi, however, there is no turning point during the rule of Henry

"the First"; the entire period required the evangelical revival of the

sixth age[77],

which is introduced and symbolized by none other than St Francis. The seventh

age of the Church would then begin with the persecution by Antichrist and

end with the Last Judgement and would lead into an eighth age of everlasting

heavenly bliss[78].

In

this spiritualized view of Church history the actual historical factors

have acquired a different weight in comparison to their significance in

the works of Joachim. What counts for Olivi are evangelical life styles

practised by quasi-professional followers of Christ, ideally personified

in St Francis and his disciples, and contrasted with the more or less corrupt

life of the secular clergy and the traditional orders. When the content

of Church history is pervaded by questions of the true Christian way of

life, questions about the political existence of the Church necessarily

lose their force. Hence, the Roman Empire as an eschatological factor sinks

in the work of Olivi to the level of an empty frame. The Emperor Henry

"the First" figures only as a scholarly reminiscence from the works of

Joachim and the Empire which he embodies no longer enjoys an independent

existence as an anti-clerical power; it merely provides the situational

framework for the conflicts of the diverging forms of life within the Church.

The

fact that the Roman Empire plays no part as a powerful political factor

in Olivi's work can be readily understood as the result of the actual decline

in its power after the death of Frederick II. In 1297, when he wrote his

commentary on the Apocalypse, and even later, in 1305, when Ubertino da

Casale composed his "Arbor vitae (316) crucifixae Jesu"[79],

a work in complete accordance with the basic eschatological ideas of Olivi,

the Empire had been living in the shadows for about half a century. At

that time there had been no emperor even in name since the death of Frederick

II!

The

situation was very different in regard to the eschatological ideas circulating

publicly shortly before the middle of the thirteenth century. This brings

me to the second tradition of eschatological writing stemming from Joachim.

In the years immediately following the fall of Jerusalem in 1187 and at

the height of the Almohad offensive around the turn of the 12/13th centuries

- that is approximately during Joachim's lifetime - Islam could be regarded

as the public enemy number one of the Church. But after the triumphal advances

of the Spanish kings following the battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212,

the conquest of almost all of the Iberian peninsula by the middle of the

thirteenth century, the agreements with the Muslims in the Holy Land subsequent

to the Third Crusade and, even more strikingly if only temporarily, the

rule over Jerusalem by the Christians as a result of Frederick II's negotiations

with Sultan al-Kamil in 1229, and, last not least, the victory of the Mongols

over the Islamic Empire in the Middle East[80],

Islam no longer seemed to pose a direct existential threat to the Church.

But the situation was totally different in regard to the late Hohenstaufen

empire. It is not chance that three pseudo-Joachimist works begin with

fictitious addresses to the Emperor Henry VI[81],

who, on entering his Sicilian inheritance, surpassed his father, Frederick

Barbarossa, in achieving hegemonial power for the Empire in Europe. Already

his rule had its despotic features, but paled to insignificance in comparison

with the regime of his son, Frederick II, whose life and death struggle

with the papacy riveted the attention of the public of his time.

The

recourse to Joachim's Henry "the First" as the prototype of the existential

threat to the Church emanating from the Roman Empire under German rule

belongs to this historical context. The change from the Muslims to the

Germans as enemy number one of the Church is most strikingly expressed

in the figure-collection of the so-called "Praemissiones" which precede

the pseudo-Joachimist Commentary on Isaiah. (317) This has been

discussed in detail above. The Commentary on Isaiah itself, written in

Southern Italy around 1260/1267, also refers to Joachim's interpretations

of the dragon's heads. Joachim's historical patterns remain totally vague,

but the enmity towards the Church of the German-Roman Empire in the person

of Henry "the First" and indeed the German princes in general is all the

more clearly expressed[82].

Henry

"the First" and the Roman Empire under German rulers as the precursors

of Antichrist in the shape of Frederick II can also be found in other works

of the Joachimist eschatological tradition in the middle of the thirteenth

century. We come across him as one of the leading figures of the Roman

Empire who harassed the Church in the enlarged versions of the pseudo-Joachimist

Commentary on Jeremiah, which probably stems from Joachim's own Order of

S. Giovanni in Fiore and must have been completed in 1242 or 1248/49[83].

Another example where we find (318) Henry "the First" as one ruler

representing the ‘new Babylon’, is the "Expositio super Sibillis et Merlino",

written between 1245 and 1250 under Joachim’s name, and preserved in two

strongly divergent forms[84].

Finally, the "De oneribus prophetarum", a work probably composed around

1255/56 in Franciscan circles and also circulating under Joachim's fictitious

authorship, follows Joachim in identifying Henry as the fifth head of the

apocalyptic dragon, and this time in Joachim's most extreme critical view

as the force which has set up its Satanic throne in the ‘North’ - a metaphor

for (319) the kingdom of evil -, and whose final successor is prophesied

to be the most malevolent of all[85].

Still

regarded as eschatologically relevant in the writings of the mid-thirteenth

century because of its actual historical significance, the Empire was accorded

only marginal rank, as we have seen, by the turn of the 13/14th centuries,

if it was mentioned at all in the eschatological literature[86].

But from the middle of the 14th century on it began to attract attention

again. The strangest evidence is provided by the "Breviloquium super concordia

Novi et Veteris testamenti", written in the 50's of the 14th century by

an unknown author from the circle of Catalonian Beguines in the tradition

of Olivi, Arnald of Villanova and - as the title of the work unmistakably

indicates - Joachim of Fiore[87].

Like Olivi, the author deals primarily with the spiritual state of the

Church, but its well-being is for him much more profoundly influenced by

the historical effects of the activities of the political powers, Pope

and Emperor[88].

He develops his ideas by adopting in an almost slavish way Joachim's scheme

of the generations, which he continues up to the middle of the fourteenth

century, interpreting it spiritually with the help of the scheme of the

seven-headed dragon of the Apocalypse[89].

In this way not only the empire but also the Roman Emperors in the line

of Henry "the First" are upgraded as a frame for eschatological events.

The part played by Henry in the destiny of the Church is, however, reduced

to a place in the list of em(320)perors[90].

The role as representative of the imperial power threatening the Church

is taken over instead by Frederick II and Louis the Bavarian[91].

Here, too, the empire as an eschatological force reflects its actual historical

significance[92].

This

assessment is valid in a rather different way for the other eschatological

writings of the Late Middle Ages, regardless of whether they are in the

Joachimist tradition or not. It applies, for example, to the works written

in the papal prison of Avignon by the Franciscan Jean de Roquetaillade,

the "Liber secretorum eventuum" of 1349 and the "Vade mecum in tribulatione"

of 1356[93],

or to a work compiled from all possible different traditions, the so-called

Telesphorus, which was composed in the time of the Great Schism[94].

The mention of the empire in these works cannot, how(321)ever, be

attributed primarily to the Joachimist tradition; it is, rather, the result

of the revival, in specifically French guise, of the legend of the Last

World Emperor[95].

It is almost a matter of course that the Empire also makes an appearance

in the German reformist tracts of the fifteenth century, which were saturated

with the eschatological conceptions of the Last World Emperor and the millennium

of peace[96],

and continually revolve around the idea of a renewal of both Empire and

Church[97].

But these writings owe very little to the Joachimist tradition. Joachim's

characteristic scheme of a rigidly fixed sequence of ages within which

the Roman Empire under German rule fulfils its role, still impressively

presented in the "Breviloquium" in spite of its schematic nature, is to

be found nowhere, as far as I can see, in the eschatological literature

of the late fourteenth and the fifteenth century[98].

There

is no trace whatever in the historical consciousness of this time of an

eschatological role for the Emperor Henry "the First". Or perhaps there

is, although it is of a rather unexpected kind! When the layman Nicholas

of Buldesdorf, who believed himself to be the incarnation of the Last World

Emperor, the Angelic Pope and the Messiah all in one, appeared at the Council

of Basle to be sentenced to death and burnt at the stake in 1446 as a false

prophet and heretic, he claimed to have acted at (322) the behest

of two saints. The one was St Emmeram, a local saint to whom he presumably

felt a special attachment. The other was the holy Emperor Henry[99].