On 19 April 1775 local Massachusetts militiamen and regular British troops began the War of American Independence at Lexington and Concord. The New England colonists reacted to this news by raising four separate armies. Each jurisdiction formed its force according to its particular experience in earlier wars and its individual interpretation of European military developments over the previous century. The speed of the American response stemmed from a decade of tension and from the tentative preparations for possible armed conflict that the colonists had made during the preceding months. The concentration of four separate armed forces at Boston under loose Massachusetts hegemony as a de facto regional army paved the way for establishing a national Continental Army.

The Continental Army was the product of European military science, but like all institutions developed by the American colonists, its European origins had been modified by the particular conditions of American experience. A proper appreciation of that Army in the context of its own times thus requires an understanding not only of the general developments in the military art of western civilization during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, but also of the particular martial traditions and experiences of the English colonists in North America.

In the seventeenth century Europeans developed a new range of weapons and gradually introduced them into their armies. At the same time a wave of dynastic wars in western Europe led to the creation of increasingly larger forces serving nation-states. Commanders and leading military theoreticians spent most of the eighteenth century developing organizational structures and tactical doctrines to exploit the potential of the new weapons and armies. The full impact of these changes came at the end of that century.1

1. The basic sources for this section are as follows: David Chandler, The Art of Warfare in the Age of Marlborough (New York: Hippocrene Books, 1976); Christopher Duffy, The Army of Frederick the Great (New York: Hippocrene Books, 1974); Robert S. Quimby, The Background of Napoleonic Warfare: The Theory of Military Tactics in Eighteenth Century France (New York: Columbia University Press, 1957); Richard Glover, Peninsular Preparation: The Reform of the British Army. 1795-1809 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1963); and Oliver Lyman Spaulding, Jr., Hoffman Nickerson, and John Womack Wright, Warfare: A Study of Military Methods From the Earliest Times (New York: Harcourt, Brace, and Co., 1925).

During the seventeenth century, the firearm replaced the pike as the basic infantry weapon. The original firearm, a heavy matchlock musket, suffered from several serious defects as a military weapon: it was cumbersome; reloading was long and complicated; the chance of misfire was extremely high, particularly in damp weather; and the lit match required to ignite the gunpowder charge betrayed positions in the dark. These defects, particularly at close quarters, required a proportion of each unit to carry pikes for defense against an attack by enemy cavalry or pikemen.

A technological breakthrough occurred in the second half of the century with the introduction of a new firing mechanism. It relied on the spark produced by a piece of flint striking a steel plate to touch off the propellant charge. Although still susceptible to moisture, the flintlock musket was lighter and more wieldy than its predecessor, had a higher rate of fire, and was easier to maintain. Late in the century, development of the socket bayonet complemented the flintlock musket. The bayonet, a foot-long triangular blade which slipped around the muzzle of the musket without blocking it, transformed the firearm into a pole weapon. The transition to the musket and bayonet combination gradually eliminated the need for defensive pikemen, who disappeared from most western European armies by the end of the first decade of the eighteenth century. Standardized flintlocks appeared shortly thereafter.

Whether produced at government arsenals or by private contractors, all eighteenth century muskets were inaccurate. Weighing over ten pounds and with a barrel over a yard long, they were difficult to aim. Flints tended to wear out after only twenty rounds, and even under ideal conditions the effective range of these smoothbore weapons, which fired one-ounce balls (two-thirds to three-quarters of an inch in diameter), was only about one hundred yards. An average soldier under the stress of combat could fire three rounds a minute for short periods, but he required considerable training to accomplish this feat. Since care in reloading was a major factor influencing accuracy, only the first round loaded before combat began was completely reliable.

New tactical formations and doctrine between 1688 and 1745 took advantage of these new weapons. The emergence of the infantry as a major factor on the battlefield gained momentum from the growing importance of firepower. Beginning with the War of the Spanish Succession (1702-14), generals sought literally to blast the enemy off the field with concentrated fire delivered at close range. They moved away from the massed formations which had characterized the era of the pike and adopted a deployment in long lines (linear tactics); by mid-century infantrymen in nearly every army stood three-deep to bring a maximum number of muskets into play. The critical firefight took place at ranges of between fifty and one hundred yards.

These weapons and tactics required adjustments in organization. Since the sixteenth century the regiment had formed the basic component of an army, providing administrative and tactical control over a group of companies. The need for better fire control in battle led to many complicated experiments. Ultimately, every army turned to a more manageable subelement, the platoon, whose fire could be controlled by a handful of officers and noncommissioned officers. Coordinating the actions of a number of these basic elements of fire (normally eight) produced the battalion, the basic element of maneuver. Most regiments were composed of two or more battalions, except in the British Army, where the regiment and battalion were normally synonymous. The relationship between the company (an administrative entity) and the platoon varied, but by the end of the century most armies were making them interchangeable.

Filled with rank and file trained to fire in unison at areas rather than individual targets, these units constituted the latest advances in organization at the time of the Seven Years' War (1756-63).

A second development during the eighteenth century was improved handling of armies on the battlefield. At the beginning of the century, armies marched overland in massed formation and took hours to deploy into line of battle. A commander who felt at a disadvantage refused battle and marched away or took refuge in fortifications. Engagements normally occurred when both generals wanted to fight. Several reforms were introduced to force battle on an unwilling opponent. The cadenced march step and standardized drill maneuvers sought to reduce the time needed to deploy and the confusion associated with forming a line of battle. These changes also allowed a commander to adjust his formations to the changing flow of a battle without risking total disruption of his ranks. Brigades and divisions controlled the movements of several battalions and increasingly became semipermanent.

Mobile field artillery also emerged in the eighteenth century. While heavy cannon continued to be important for fortresses and sieges, lighter guns were introduced to give direct support to the infantry. Standardized calibers eased administrative and logistical problems. Ballistics experts and metallurgists reduced the weight of the tubes, while others improved carriages. The French emerged with the best of the new artillery after reforms in 1764 by General Jean Baptiste de Gribeauval, an experienced combat officer and able theoretician. The new mobility enabled tacticians to consider artillery as a supporting arm whose function was firing at enemy personnel instead of engaging in artillery duels. In nearly every European army the artillery became a separate armed service, legally distinct from the infantry and cavalry.

The army which naturally exercised the greatest influence on the American colonies was the British. Great Britain enjoyed a unique status among the great powers during this period because its strong navy gave it security from attack by its neighbors. One consequence was that the British Army at first lagged behind the other European armies in adopting the reforms of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, but by the time of the Seven Years' War, it had adopted the major ones. In fact, it had led the way in introducing many techniques of infantry fire control. Its slow and ad hoc growth as an institution, however, had produced an inefficient and extremely complex administrative and logistical superstructure. Authority and responsibility were divided between two major Army commands (the British and Irish Establishments), between the Army proper and the Ordnance Department (controlling artillery, engineers, and munitions), and between the civilian Secretary at War and the military Commander in Chief (when that office was filled). Strategic direction was shared by two or three civilian Secretaries of State. At times the various individuals responsible for these chains of command cooperated, and the system functioned well. However, when breakdowns occurred, the British Army appeared leaderless and inept.2

English military institutions formed part of the cultural inheritance which the first colonists brought to America. Immigrants and occasional contact with the British

2. Glover, Peninsular Preparation, pp. 2, 12.

Army kept the colonists informed about newer developments. The most important of the inherited institutions was the militia, which dated back to Anglo-Saxon times, but the specific conditions of colonial settlement produced important modifications. Other variations crept in as the defensive needs of the colonies began to outstrip the capabilities of the militia.

The Tudors had revived the English militia in the sixteenth century as an inexpensive alternative to a large permanent army. They used the traditional universal obligation to serve in the defense of the realm as a basis for sustaining a body of voluntary "trained bands." The members of the general population acted as a reserve force through their possession of arms, and various fines levied on them in relation to their obligations furnished financial support for the trained bands. The county lords lieutenant provided organization, geographical identity, and central direction.3

The first settlements in Virginia, Plymouth, Massachusetts Bay, and Connecticut all recruited professional soldiers to act as military advisers. The colonists recognized from the beginning that both the Indians and England's European rivals posed potential threats. The Jamestown trading post organized itself into a virtual regimental garrison, complete with companies and squads. Plymouth, on the advice of Miles Standish, organized four companies of militia within two years of its founding. The Massachusetts Bay Colony profited from the experiences of the earlier settlements. In 1629 its first expedition left England for Salem with a militia company already organized and equipped with the latest weapons.

During the course of the seventeenth century the colonists adapted the English militia system to meet their own particular needs. Several regional patterns emerged. In the Chesapeake Bay area a plantation economy took root, leading to dispersed settlement. Virginia and Maryland formed their militia companies from all the residents of a particular area. In New England religion and a different economy led to a town-based residential system. Each town formed one or more militia companies as soon as possible after establishing its local government. South Carolina had a plantation economy, but its settlers came from Barbados and brought a large slave population with them. Its militia followed the example of Barbados and placed a heavy emphasis on controlling the slaves. Pennsylvania, on the other hand, did not pass a law establishing a mandatory militia until 1777. The differences in the militia establishments among these colonies in part explain later variations in organizing units for the Continental Army in 1775-76.

Growth in each colony soon led to innovations. In Massachusetts, for example, an excess of noncommissioned officers over European norms allowed for forming subordinate elements, or "demi-companies," which received a field test in a 1635 punitive expedition against Indians on Block Island. When the colony then grouped its fifteen

3. Unless otherwise noted, this section is based on the studies of colonial militias listed in the bibliography and on the following: Darrett A. Rutman, "A Militant New World, 1607-1640: America's First Generation, Its Martial Spirit, Its Tradition Of Arms, Its Militia Organization, Its wars" (Ph.D. diss., University of Virginia, 1959); Patrick Mitchell Malone, "Indian and English Military Systems in New England in the Seventeenth century (Ph.D. diss., Brown university, 1971); John W. Shy, "A New Look at Colonial Militia," William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser., 20 (1963):175-85; Timothy Breen, "English Origins and New World Development: The case of the Covenanted Militia in Seventeenth-Century Massachusetts," Past and Present 57 (1972):74-96; Douglas Edward Leach, Arms for Empire: A Military History of the British Colonies in North America. 1607-1763 (New York: Macmillan Co., 1973); and Howard H. Peckham, The Colonial Wars, 1689-1762 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1964).

companies into three regional regiments in December 1636, it became the first English-speaking government to adopt permanent regiments. Other colonies followed: Maryland and Plymouth in 1658, Virginia in 1666, and Connecticut in 1672. Standing regiments appeared in the English Army only in the 1640's.

Another modification of the European heritage occurred in the choice of weapons. Wilderness conditions accentuated the flintlock musket's advantages. By 1675 nearly every colony required its militiamen to own flintlocks rather than matchlocks: American armies thus completed this transition a quarter of a century before European armies. Many colonists hunted, but few had ever fought in a formal line of battle. Militia training consequently stressed individual marksmanship rather than massed firing at an area, which had been the norm in the Old World. A specific byproduct of this emphasis was the refinement of the rifle—a hunting weapon with German roots—by gunsmiths in Pennsylvania. The Pennsylvania rifle was longer than the standard musket but had a smaller bore (usually .45-caliber). Grooves, or rifling, cut into the barrel imparted spin to the ball and allowed a trained marksman to hit targets at up to 400 yards. As a military weapon the rifle was effective in skirmishing, but its slow rate of fire and lack of a bayonet placed riflemen at a disadvantage in open terrain.

By the eighteenth century the colonial militia, like the English trained bands, was armed with flintlocks and was organized geographically. The southern colonies with one regiment per county were closest to the "shire" system; the more densely populated northern colonies normally formed several regiments in each county. Most colonies gave both administrative and command responsibilities to the colonel of each regiment and dispensed with the office of county lieutenant. Local elites in both the mother country and America dominated the militia officer positions, whether elected or appointed, just as they controlled all other aspects of society. Ultimate responsibility for the militia was a function of the Crown. In England it was exercised for the Crown by the county lords lieutenant; in America, by the governor. The financial powers of the elective lower houses of the colonial legislatures, however, placed major limits on a governor's prerogatives.

The biggest difference between the English trained bands and the colonial militia was the latter's more comprehensive membership. Few free adult males were exempted by law from participating: the clergy, some conscientious objectors, and a handful of other special groups. This situation was the result of the first settlers' immediate need for local defense, a need absent in England since the days of the Spanish Armada. But in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, the danger to the more settled regions subsided. Although a militia structure based on an area's total male population was an admirable goal for local defense, taking the men for military service disrupted a colony's economy during extended crises or lengthy offensives. As other institutions emerged, the militia was left as "a local training center and a replacement pool, a country selective service system and a law enforcing agency, an induction camp and a primitive supply depot."4

As early as the 1620's in Virginia and in the 1630's during the Pequot War in New England, temporary detachments were drawn from the militia companies for field operations against the Indians. Volunteers or drafted quotas formed the detachments. This expedient practice minimized economic dislocation and concentrated field lead-

4. Louis Morton, "The Origins of American Military Policy," Military Affairs 22 (1958):80.

ership in the hands of the most experienced officers. But even the detachments were seen as disrupting community life too much, and eventually they were employed primarily as garrisons. A different type of force emerged in the 1670's. Hired volunteers ranged the frontiers, patrolling between outposts and giving early warning of any Indian attack. Other volunteers combined with friendly Indians for offensive operations deep in the wilderness where European tactics were ineffective. The memoirs of the most successful leader of these mixed forces, Benjamin Church, were published by his son Thomas in 1716 and represent the first American military manual.5

During the Imperial Wars (1689-1762) against Spanish and French colonies, regiments completely separated from the militia system were raised for specific campaigns. These units, called Provincials, were patterned after regular British regiments and were recruited by the individual colonial governors and legislatures, who appointed the officers. Bounties were used to induce recruits, and the officers enjoyed a status greater than that of equivalent militia officers. Although new regiments were raised each year, in most colonies a large percentage of officers had years of service. Provincial field officers tended to be members of the legislature who had compiled long service in the militia. The company officers, responsible for most of the recruiting, were drawn from popular junior militia officers with demonstrated military skills.6 The most famous Provincial units were formed by Maj. Robert Rogers of New Hampshire during the French and Indian War. His separate companies of rangers were recruited throughout the northern colonies and were paid directly by the British Army. They performed reconnaissance for the regular forces invading Canada and conducted occasional long-range raids against the French and their Indian allies.

The French and Indian War was different from earlier wars in one very important way. Formerly Great Britain had been content to leave fighting in North America to the colonists and had furnished only naval and logistical aid. William Pitt's ministry reversed that policy, and the regular British Army now carried out the major combat operations. The Provincials were relegated to support and reserve functions. Americans resented this treatment, particularly when they saw British commanders such as Edward Braddock and James Abercromby perform poorly in the wilderness. At the same time, Britons formed a negative opinion of the fighting qualities of the Provincials. British recruiting techniques and impressment of food, quarters, and transport created other tensions: The resulting residual bitterness contributed to the growing breach between the colonies and the mother country during the following decade.

During the years following the Seven Years' War, the central government in London adopted a series of policies which altered the traditional relationship between England and the American colonies. The colonists, whose political institutions were rapidly maturing, resented English intervention in what they viewed as their internal

5. Benjamin Church, The History of the Great Indian

War of 1675 and 1676, Commonly Called Philip's War. Also. The Old French

and Indian Wars, From 1689 to 1704, ed. Samuel G. Drake (Hartford:

Silas Andrus & Son, 1854).

6. Ranz E. Esbenshade, "Sober, Modest Men of Confined

Ideas: The Officer Corps of Provincial New Hampshire" (Master's thesis,

University of New Hampshire, 1976).

TIMOTHY PICKERING (1745-1829), author of a military manual and commander of a regiment of Essex County, Massachusetts, militia, served the Continental Army as adjutant general, quartermaster general, and member of the Board of War. (Portrait by Charles Willson Peale, 1792.)

affairs. Many different issues led to a growing alienation. By 1774 there was a real potential for armed confrontation.7

A change in British military policy was a catalyst for the controversy. After the 1763 Peace of Paris, London decided to create an American Establishment and to tax the colonists to pay for it. In the eyes of London planners, this army, patterned on a similar garrison stationed in Ireland for nearly a century, would serve several useful ends. It would enable the British Army to retain more regiments in peacetime than it could have otherwise. The regiments in America were to secure the newly won territories of Canada and Florida from French or Spanish attack and also to act as a buffer between the colonists and the Indians. The Americans felt that these troops served no useful purpose, particularly when the majority moved from the frontier to coastal cities to simplify logistics. As tensions rose, the colonists became more suspicious of British aims and increasingly saw the regular regiments as a "standing army" stationed in their midst to enforce unpopular legislation.

Political leaders cited the American Establishment in their rhetoric as an example of the British government's corruption and unconstitutional policies. Threats to use the troops in New York City to enforce the Stamp Act and to act as police during later land unrest in the Hudson River Valley caused initial concern. A major affront in American eyes came when Britain transferred several regiments to Boston in the immediate aftermath of protests over taxes imposed by the Townshend Act. To Americans this pattern paralleled the actions of the Stuarts in England in the late seventeenth

7. Basic sources for this section are the following: Alan Rogers, Empire and Liberty: American Resistance to British Authority. 1755-1763 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974); John Shy, Toward Lexington: The Role of the British Army in the Coming of the American Revolution (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1965); and David Ammerman, In The Common Cause: American Response to the Coercive Acts of 1774 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1974).

century. In 1770 the Boston Massacre proved this point to a large body of the American people.8

Other American leaders moved beyond rhetoric to counter force with force. For instance, the Sons of Liberty emerged in New York in 1765-66 as a paramilitary organization in direct response to British troop movements. Even more intense reactions came in Massachusetts, the center of opposition to British policy. Although most troops withdrew from Boston in 1771, a garrison remained. Local politicians began agitating for serious militia reforms to create a force capable of offering opposition to the British Army if it returned in strength. A number of individuals who later occupied important positions in the Continental Army, such as Timothy Pickering ("A Military Citizen") and William Heath ("A Military Countryman"), contributed articles to the Massachusetts press advocating such reforms. Others organized voluntary military companies for extra training.9

When British troops returned to Boston in far greater numbers after the Boston Tea Party of 1773, the final phase of tension began. If Americans needed any further proof of British intent, this action and Parliament's punitive "Coercive Acts" furnished it. Military preparations quickened throughout New England, and the First Continental Congress met at Philadelphia in September to direct a concerted effort to secure a redress of American grievances. New Englanders removed militia officers known to be loyal to the Crown and increased the tempo of training. By the autumn of 1774 calls arose for forming a unified colonial army of observation that could take the field if hostilities erupted.10 Similar trends, although less pronounced, existed in the middle and southern colonies.

Interest in the militia was matched during 1774 and early 1775 by a concern for war supplies. Adam Stephen, later a major general in the Continental Army, spoke for many in 1774 when he warned Virginia politicians that artillery, arms, and ammunition were in short supply in the colonies. His suggestions to encourage domestic production and importation from Europe were echoed by others who agreed with his statement that if enough arms and ammunition were available, "individuals may suffer, but the gates of hell cannot prevail against America."11 Imports of arms and powder

8. John Todd White, "Standing Armies in Time Of war: Republican

Theory and Military Practice During the American Revolution" (Ph.D. diss.,

George Washington university, 1978), pp. 1-111; Lawrence Delbert Cress,

"The Standing Army, the Militia, and the New Republic: Changing Attitudes

Toward the Military in American Society, 1768 to 18209' (Ph.D. diss., University

of Virginia, 1976), pp. 80-128.

9. Ronald L. Boucher, "The Colonial Militia as a Social

Institution: Salem, Massachusetts, 1764-1775," Military Affairs 37

(1973):125-26; Stewart Lewis Gates, "Disorder and Social Organization:

The Militia in Connecticut Public Life, 1660-1860" (Ph.D. diss., University

of Connecticut, 1975), pp. 35-38; Roger Champagne, "The Military Association

of the Sons of Liberty,'' New-York Historical Society Quarterly 41

( 1957):338-50.

10. David Richard Millar, "The Militia, the Army, and

Independency in Colonial Massachusetts" (Ph.D. diss., Cornell University,

1967), pp. 284-88; Peter Force, ed., American Archives: A Collection

of Authentic Records, State Papers, Debates, and Letters and Other Notices

of Public Affairs, 9 vols. (Washington: M. St. Clair Clarke and Peter

Force, 1839-53), 4th ser., 1:739-40, 787-88; J. Hammond Trumbull and Charles

C. Hoadley, comps., The Public Records of the Colony of Connecticut,

15 vols. (Hartford, 1850-90), 14:296, 308-9, 327-28, 343-46 (hereafter

cited as Conn. Records); John Russell Bartlett, ed., Records

of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations in New England,

9 vols. (Providence, 18-64, 7:247, 257-71 (hereafter cited as R.

I. Records); Nathanael Greene, The Papers of General Nathanael Greene,

ed. Richard K. Showman et al. (Chapel Hill: university of North Carolina

Press, 1976- ), 1:68-76; Historical Magazine, 2d ser., 7 (1870):22-26.

11. Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 1:739-40.

grew by October 1774 to such a degree that British officials became alarmed. Individual colonial governments began to move existing stores beyond the reach of British seizure and to encourage domestic manufacturers. Massachusetts took the lead in collecting munitions, as it did in reforming the militia.12

The First Continental Congress rejected a proposal by Richard Henry Lee of Virginia to form a nationwide militia but did adopt a plan for concerted economic protest. The plan provided for a boycott of British goods after 1 December 1774 and authorized forming enforcement committees which quickly became de facto governments at the colony and local levels. The committees also secured political control over the countryside, a control which British authorities were never able to shake. This political control included leadership of the militia, and that institution became an instrument of resistance to the British. Instead of being intimidated by Britain's Coercive Acts of 1774, the colonists were moving toward armed resistance.

Thus in the years immediately before 1775, tensions built to the point that the leaders in each colony foresaw the possibility of violence. They reacted by gathering war materials and restoring the militia (or volunteer forces) to a level of readiness not seen since the early days of settlement. British officers in America were aware of the colonists' actions but dismissed them as "mere bullying."13 Given these attitudes, the presence of Maj. Gen. Thomas Gage's garrison in Boston, and the advanced state of preparation in Massachusetts, it is not surprising that war began in that colony.

The Massachusetts Provincial Congress met as a shadow government and on 26 October 1774 adopted a comprehensive military program based on the militia. It created the executive Committees of Safety and of Supplies and gave the former the power to order out the militia in an emergency. It also directed the militia officers to reorganize their commands into more efficient units, to conduct new elections, to drill according to the latest British manual, and to organize one-quarter of the colony's force into "minute companies." The minutemen constituted special units within the militia system whose members agreed to undergo additional training and to hold themselves ready to turn out quickly ("at a minute's notice") for emergencies. Jedediah Preble, Artemas Ward, and Seth Pomeroy, three politicians who had served in the French and Indian War, were elected general officers of the militia. A month later two younger general officers were added: John Thomas (a veteran of the French and Indian War) and William Heath (a militiamen with a reputation as an administrator). During periods of congressional recess, the Committee of Safety and the Committee of Supplies collected material and established depots.14

12. Ibid., pp. 746, 841-45, 858, 881, 953, 1002, 1022,

1032, 1041-42, 1066, 1077, 1080, 1143-45, 1332-34, 1365-70; Paul H. Smith

et al., eds., Letters of Delegates to Congress. 1774-1789 (Washington:

Library of congress, 1976- ), 1:266-71, 298-301.

13. Hugh Earl Percy, Letters of Hugh Earl Percy From

Boston and New York 1774-1776, ed. Charles Knowles Bolton (Boston:

Charles L Goodspeed, 1902), pp. 35-37; see also W. Glanville Evelyn, Memoir

and Letters of Captain W. Glanville Evelyn, of the 4th Regiment (''King's

Own") From North America, 1774-1776, ed. G. D. Scull (Oxford: James

Parker and Co., 1879), pp. 31-37.

14. Unless otherwise noted, this section is based on

Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 1:830-53, 993-1008, 1322-69;

2:461, 524, 609-10, 663, 742-830, 1347-1518.

ARTEMAS WARD (1727-1800) of Massachusetts became the Continental Army's senior major general and first commander of the Eastern Department. (Portrait by Charles Willson Peale, ca. 1794.)

After new elections were held, the Provincial Congress reconvened in February 1775. It clarified the Committee of Safety's powers, reappointed the five generals, and added John Whitcomb, another politically active veteran, as a sixth general.15 The Congress also altered its basic military policy. In the face of increased tension, it took steps to augment the militia with a more permanent force patterned after the earlier Provincials. Regulations for this "Constitutional Army" were adopted on 5 April.

The Provincial Congress made a momentous decision three days later. By a vote of 96 of 103 members present, a report on the "State of the Province" was approved. The report stated that "the present dangerous and alarming situation of our publick affairs, renders it necessary for this Colony to make preparations for their security and defence by raising and establishing an Army." The projected volunteer force was to include more than just Massachusetts men, and delegates were sent to the other New England colonies to urge their participation. On 14 April the Committee of Safety was instructed to begin selecting field officers for Massachusetts' contingent. These officers, in turn, were to assist the committee in selecting captains, who would appoint subalterns. Minuteman officers were given preference. Officers selected would then raise their regiments and companies, as the Provincial officers had done.

After initiating its plans for a New England army, the Provincial Congress adjourned on 15 April. It reassembled on the 22d after the events at Lexington and Concord. The first order of business was accumulating testimony to prove to the English people that Gage's troops had been the aggressors.16 The congress then turned its attention to forming a volunteer army from the men who had massed around Boston. The Committee of Safety had already taken tentative steps in this direction. On 21 April

15. The age of some of the generals raises some doubt about their

ability to take to the field: Pomeroy was 68, Preble 67, Whitcomb 61, Thomas

50, Ward 47, and Heath 37.

16. The testimony collected was published as A Narrative of

the Excursions and Ravages of the King's Troops . . . (Worcester: Isaiah

Thomas, 1775).

13

TABLE 1- INFANTRY REGIMENTS, 1775

| Field | Staff | Each Company | Aggregate | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colony | Colonel | Lieutenant Colonel | Major | Adjutant | Quartermaster | Surgeon | Surgeon’s Mate | Chaplain | Number of Companies | Captain | Lieutenant | Ensign | Sergeant | Corporal | Drummer | Fifer | Privates | Officers | Staff Officers | Noncommisioned Officers |

Drummers and Fifers | Privates | Total Strength |

| Massachusetts | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 46 | 33 | 6 | 80 | 20 | 460 | 599 |

| New Hampshire | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 53 | 33 | 5 | 60 | 20 | 530 | 648 |

| Rhode Island | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 10a | 1b | 1b | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 49 | 33 | 4 | 60 | 20 | 490 | 607 |

| Connecticut | 1c | 1 | 1c | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 10 | 1d | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 90c | 40 | 6 | 80 | 20 | 900c | 1.046e |

| New York | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 64 | 33 | 5 | 60 | 20 | 640 | 758 |

a One regiment only nine companies.

b Three companies in each regiment with captain-lieutenant instead of captain.

c Where colonel was general officer two majors authorized.

d Three companies without caplain.

e 7th and 8th Connecticut Regiments had only 65 privates per company.

the committee had approved an enlistment format; 8,000 effectives were to serve until 31 December in regiments consisting of a colonel, a lieutenant colonel, a major, and 9 companies. The committee planned to have each-company consist of 3 officers, 4 sergeants, a drummer, a fifer, and 70 rank and file, though it subsequently reduced the latter figure to 50. The pre-Lexington plan had been to form an army by apportioning quotas of men on the various towns, a traditional colonial device. The committee decided instead to have the generals survey the men at the siege lines at Boston to persuade them to remain. Its decisions were preliminary since final authority rested with the Provincial Congress. As confusion spread, on 23 April General Ward, the commander of the siege, suggested that the congress use smaller units to retain a maximum number of officers.

The Provincial Congress incorporated Ward's suggestions into a comprehensive plan that it adopted the same day. It called for a New England army of 30,000 men, of which Massachusetts would furnish 13,600. The regimental organization adopted for the infantry called for 598 men: a colonel, a lieutenant colonel, a major, an adjutant, a quartermaster, a chaplain, a surgeon, 2 surgeon's mates, and 10 companies. Each company was to have a captain, 2 lieutenants, an ensign, and 55 enlisted men. On 25 April, following additional discussions with the Committee of Safety, this structure was confirmed with one change: it also accepted the committee's suggestion that each regiment headed by a general officer have two majors. (Table 1) Finally, after some discussion, it approved pay scales for the new force.

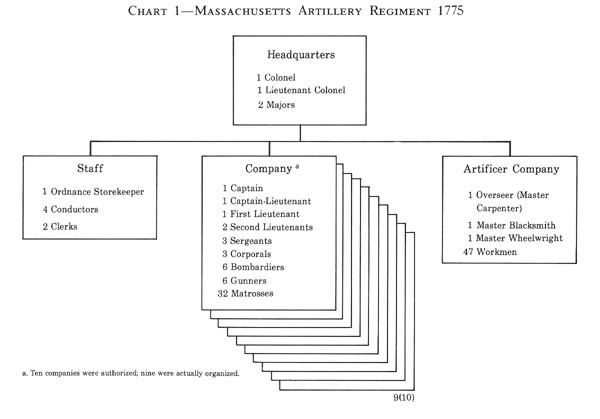

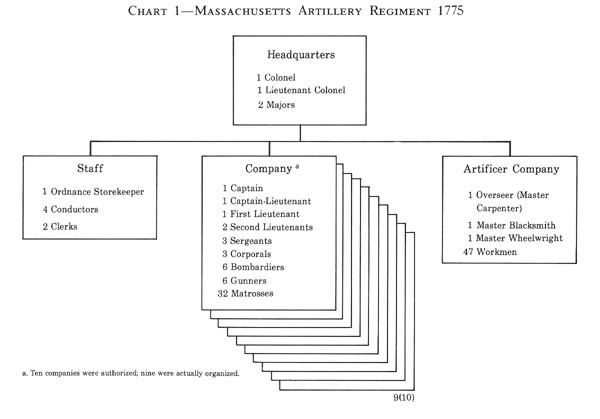

The Massachusetts plan called for artillerymen as well as infantry regiments. As early as 23 February the Committee of Safety, planning to train artillery companies, had distributed field guns to selected militia regiments. On 13 April the Provincial Congress had directed the committee to form six companies for the planned volunteer army. On 6 May congress adopted an organization of 4 officers, 4 sergeants, 4 corporals, a drummer, a fifer, and 32 matrosses, or privates, for each company. Four days

later it rescinded that organization and sent a committee to confer with Richard Gridley on the propriety of organizing a full artillery regiment. Gridley, hero of the 1745 capture of Louisbourg, was the colony's leading expert on artillery. Following the talks, on 12 May the Provincial Congress authorized a ten-company regiment. (Chart 1) Four days later it gave Gridley the command.

The regiment formed in June. Neither Gridley nor William Burbeck, his assistant, could concentrate on it since they had also been appointed the colony's two engineers on 26 April. In June the Committee of Safety added a logistical staff and an organic company of artificers (skilled workmen) to do maintenance. The important post of ordnance storekeeper went to Ezekiel Cheever. The company officers came largely from the several Boston militia artillery companies, particularly Adino Paddock's which had received extensive training from British artillerymen in the 1760's and was composed mostly of skilled artisans and Sons of Liberty. Two of its members, John Crane and Ebenezer Stevens, had moved to Providence, Rhode Island, in 1774 after the closing of the port of Boston. Their close ties enabled the Rhode Island artillerymen to merge easily with the regiment in 1776.17

In spite of careful preparations, Massachusetts entered the war in a state of chaos. The Provincial Congress and the Committee of Safety frequently found themselves working at cross-purposes. Confusion over the size and configuration of the army created duplication of effort, and prospective officers were recruited under a variety of authorities. The minutemen and other militia who had responded to Lexington by

17. John Austin Stevens, "Ebenezer Stevens, Lieut. Col. of Artillery in the Continental Army," Magazine of American History 1 (1877):588-92; Asa Bird Gardner, "Henry Burbeck: Brevet Brigadier-General United States Army—Founder of the United States Military Academy," ibid., 9(1883):252.

besieging Boston, moreover, were not prepared to remain in the field for an extended period, although later arrivals were more inclined to serve a full term (until 31 December).

Order began to emerge in May when formats for commissions and oaths were codified. Mustermasters were appointed to examine enlistment rolls at Cambridge and Roxbury so that the Committee of Safety could certify officers for commissioning. Regiments emerged with a geographic basis, drawing their precedence from that of the militia which furnished the majority of their men. Since all commissions were dated 19 May 1775, the touchy matter of seniority remained to be settled later. By the end of June twenty-six regiments had been certified, plus part of a regiment whose status as a Massachusetts or New Hampshire unit was unresolved.

During early June 1775, the Massachusetts army achieved a relatively final form. The Provincial Congress decided on 13 June to retain in service a force of one artillery and twenty-three infantry regiments. This limit was altered ten days later when the raising of troops specifically for coastal defense released Edmund Phinney's Cumberland County regiment from that mission to join the army. The Congress also resolved the status of the generals. Ward retained the overall command he had exercised since the outbreak of hostilities. John Whitcomb, William Heath, and Ebenezer Frye were designated major generals.18

With remarkable speed, committees of correspondence spread the traumatic news of Lexington and Concord beyond the borders of Massachusetts. By 24 April New York City had the details and Philadelphia had them by the next day. Savannah, the city farthest from the scene of the engagement, received the news on 10 May.19 Massachusetts' call for a joint army of observation was answered by the three other New England colonies—New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Connecticut. Each responded in its own way. Within two months three small armies joined the Massachusetts troops at Boston, and a council of war began strategic coordination. This regional force paved the way for the creation of a national institution, the Continental Army.

New Hampshiremen responded as individuals and in small groups to the news of Lexington. On 25 April, anticipating formal aid from New Hampshire, the Massachusetts Committee of Safety directed Paul Dudley Sargent of Hillsborough County to raise a regiment from these individuals.20 Four days earlier the New Hampshire Provincial Congress had convened in emergency session. After considering a copy of Massachusetts' plan for a New England army, the New Hampshire body sent three of its members to confer with the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, but deferred further action until it could mobilize public support and make adequate financial plans.21

18. The coast defense troops remained in state service

instead of becoming Continentals. Joseph Warren, who was to have been senior

major general, was killed at Bunker Hill before he received his commission.

19. Frank Luther Mott, "The Newspaper Coverage of Lexington

and Concord." New England Quarterly 17 (1944):489-505.

20. When New Hampshire did not accept responsibility

for Sergent's regiment, Massachusetts did.

21. This section on New Hampshire is based on the following:

Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 2:37779, 401, 429-30, 519-24,

639-60, 745, 868, 1005-7, 1022-23, 1069-70, 1092, 1176-86, 1529; 4:1-20;

John Sullivan, Letters and Papers of Major-General John Sullivan, Continental

Army, ed. Otis G. Hammond, 3 vols. (Concord: New Hampshire Historical

Society, 1930-39), 1:58-60; and Chandler Eastman Potter, Military History

of New Hampshire, From Its Settlement. in 1623, to the Year 1861, 2

vols. (Concord: Adjutant General's Office, 1866), 1:263-272.

On 18 May the full Provincial Congress resolved to raise men "to join in the common cause of defending our just rights and liberties." Legislation on 20 May created a Committee of Safety and authorized a 2,000-man quota for the New England army. This figure included those New Hampshiremen already in service at Boston. The initial plan called for regiments organized on the same pattern as those in Massachusetts, but two days later, on 22 May, the Congress adopted a more specific plan. (See Chart 1.) It created three regiments and dispatched two officials to Cambridge to muster the volunteers who had gone to Massachusetts as one of those regiments. The volunteers had already elected John Stark, a veteran of Rogers' Rangers, as their colonel.

On 23 May the Provincial Congress appointed Nathaniel Folsom as the general officer to command the colony's forces, and the Committee of Safety began to nominate officers for the three regiments. On 24 May Enoch Poor of Exeter received command of the second of the regiments with an order to organize it immediately. On 1 June the congress appointed the officers of the 3d New Hampshire Regiment, the command going to James Reed of Fitzwilliam. Reed raised it in Strafford and Rockingham counties. Two days later the congress designated the regiment at Boston the 1st, or "eldest," Regiment, and confirmed Stark and its other field officers.

Folsom initially received the rank of brigadier general with duties similar to those of such officers in Massachusetts, except that he had no regimental command. On 6 June the Provincial Congress reaffirmed his authority as the commanding general, under General Ward, of all New Hampshire forces, and at the end of the month it promoted him to major general. Jealousy by the volunteers at Boston limited his authority for a time. When Reed assembled his 3d New Hampshire Regiment at Boston on 14 June, he received two of Stark's surplus companies to round out the unit. Poor's 2d New Hampshire Regiment was detained to defend the colony from possible British attack, but it was ordered to Cambridge on 18 June. Its last company arrived in early August. Although Folsom had wanted an artillery company to support his regiments, New Hampshire had no officers qualified to command one. The best the Provincial Congress could do was to send artillery pieces for the Massachusetts men to use.

Meeting in emergency session in response to the news of Lexington, the Rhode Island Assembly on 25 April decided to raise 1,500 men "properly armed and disciplined, to continue in this Colony, as an Army of Observation; to repel any insults or violence that may be offered to the inhabitants; and also, if it be necessary for the safety and preservation of any of the Colonies, that they be ordered to march out of this Colony, and join and cooperate with the Forces of our neighbouring Colonies."22 It deferred substantive action until the regular May session. In the interim the commander of the Providence County militia brigade offered Massachusetts the services of his three battalions; other individuals went off to Boston as volunteers.

At the regular May session, the Rhode Island Assembly created an "Army of Observation" and a Committee of Safety. Because Governor Joseph Wanton remained loyal to the Crown, the colony's secretary signed the commissions. Deputy Governor Nicholas Cooke soon replaced Wanton. Rhode Island organized its contingent as a balanced brigade under Brig. Gen. Nathanael Greene, thus adopting a different ap-

22. Force, American Archives, 4th ser., 2:390. For Rhode Island see the following: ibid., 431, 590, 900; Bartlett, Rhode Island Records 7:308-61; Greene Papers, 1:78-85; and Rhode Island Historical Society Collections, 6:108-9.

proach than that of the other New England colonies. (See Chart 1.) Greene's staff included a brigade adjutant and a brigade commissary responsible for logistics. The troops formed three regiments (two with eight companies and one with seven) and a company of artillery.23 Greene, Cooke, and the Committee of Safety arranged the officers; since all commissions were dated 8 May, seniority was resolved by drawing lots. The three regiments rotated posts of honor to avoid establishing a system of precedence. One regiment was raised in Bristol and Newport Counties by Thomas Church; another was raised by Daniel Hitchcock in Providence County. A business associate of Greene's, James Mitchell Varnum, was given command of the regiment from King's and Kent counties, while John Crane, formerly of Boston, became captain of the artillery company.

Companies left for Boston as quickly as possible. Hitchcock's and Church's regiments had assembled there by 4 June, the date that Greene opened his headquarters. The artillery company, armed with four field pieces and escorting a dozen heavy guns, also arrived in early June. Varnum's regiment arrived several weeks later. The Rhode Island Assembly reconvened on 12 June and remained in session until 10 July. During this period it settled various logistical and disciplinary matters and added a secretary, a baker, and a chaplain to the brigade's staff. It also raised six new companies, two for each regiment. Greene was given the power, in consultation with the field officers, to fill vacancies, and he was placed under the "command and direction" of the Commander in Chief of the "combined American army" in Massachusetts.24

On 21 April representatives from Massachusetts met with the Connecticut Committee of Correspondence in the home of Governor Jonathan Trumbull at Lebanon. Trumbull sent his son David to inform Massachusetts that a special session of the Connecticut assembly would meet as soon as possible. While some Connecticut militia units marched to Boston on hearing of Lexington, most followed the advice of the governor to wait until the assembly could act. The wisdom of this course was confirmed by news that although Israel Putnam had asserted a loose hegemony over the volunteers, a formal command structure was needed before they would become effective.25

The special session convened at Hartford on 26 April, and the next day the Connecticut Assembly ordered that six regiments be raised, each containing ten companies. (See Chart 1.) Officers were appointed on 28 April and arranged on 1 May. At the time the assembly believed that these 6,000 men represented 25 percent of the colony's militia strength; they were obligated to serve until 10 December. The companies were apportioned among the several counties according to population. Connecticut's regimental structure followed a somewhat older model than that chosen by the other colonies and was considerably larger. Connecticut placed generals in direct command of regiments, as Massachusetts did, but followed Rhode Island's example in having field officers command companies. This left generals filling three roles at the same

23. The artillery company consisted of a captain (later

major), captain-lieutenant (later captain), 3 lieutenants, a conductor,

2 sergeants, 2 bombardiers, 4 gunners, 4 corporals, 2 drummers, 2 fifers,

and 75 privates.

24. Some pieces of legislation stated that troops were

to serve until 1 December; others, until 31 December. The latter date became

official.

25. This section on Connecticut is based on the following:

Conn. Records, 14:413-40; 15:1-109; Force, American Archives,

4th ser., 2:370-73, 383-84, 423-24, 731, 1000-1002, 1010; and Wladimir

Edgar Hagelin and Ralph A. Brown, eds., "Connecticut Farmers at Bunker

Hill: The Diary of Colonel Experience Storrs," New England Quarterly

28 (1955):84-89.

time—that of general, colonel, and captain. Rather than assigning an extra lieutenant to each field officer's company, as Rhode Island did, Connecticut merely designated the senior lieutenant in each colonel's company as a captain-lieutenant. On the other hand, the Connecticut organization called for each company to contain four officers rather than the three the other New England jurisdictions provided. The assembly appointed Joseph Spencer and Israel Putnam brigadier generals and David Wooster major general. It assigned supply responsibilities to Joseph Trumbull, another of the governor's sons, by appointing him commissary general.

After a recess the assembly reconvened on 11 May and remained in session for the rest of the month, passing legislation that resolved a number of logistical, administrative, and disciplinary problems. It defined the regimental adjutant as a distinct officer. It also appointed Samuel Mott as the colony's engineer, with the rank of lieutenant colonel, and ordered him to Fort Ticonderoga. This session created a Committee of Safety, also known as the Committee of Defense or the Committee of War, which served for the rest of the war as the governor's executive and advisory body. The assembly considered, but rejected, reorganizing the six regiments into eight to bring the size of these units more into conformity with that of the regiments from the other colonies. Another special session (1-6 July) added two more regiments, but these were smaller than the earlier ones. The assembly reduced the number of privates in these regiments by nearly a third, while retaining their same organization and superstructure, and then ordered both to Boston.

Deployment of the Connecticut regiments followed a pattern established during the colonial period. In the Imperial Wars the colony had been responsible for reinforcing its neighbors, supporting New York on the northern frontier around Albany and assuming primary responsibility for the defense of western Massachusetts. In 1775 Spencer's 2d and Putnam's 3d Connecticut Regiments, raised in the northeastern and north-central portions of the colony, naturally marched to Boston. Samuel Parsons' 6th, from the southeast, followed as soon as the vital port of New London was secure. Benjamin Hinman's 4th, from Litchfield County in the northwest, went to Fort Ticonderoga, where the county's men had served in earlier wars. The 1st under Wooster and the 5th under David Waterbury, from Fairfield and New Haven Counties, respectively, in the southwest, prepared to secure New York City.26 News of the battle of Bunker Hill led Governor Trumbull to place the men in Massachusetts temporarily under the command of General Ward. At the same time the 1st and 5th regiments were ordered into New York, subject to the orders of the Continental Congress and the New York Provincial Congress.

Although the three other New England colonies, in responding to Massachusetts' plan for a joint army, experienced delays in fielding their regiments, these delays turned out to be a blessing. The regiments were formed in a rational manner that avoided the confusion that had plagued Massachusetts' efforts. Only the 1st New Hampshire Regiment, organized from the volunteers at Boston, experienced the same organizational troubles the Massachusetts regiments did.

26. Richard H. Marcus, "The Connecticut Valley: A Problem in Intercolonial Defense," Military Affairs 33 (1969):230-42; Marcus A. McCorison, "Colonial Defense of the Upper Connecticut Valley," Vermont History, n.s., 30 (1962):50-62. Some companies were diverted to sectors other than their regiment's to meet immediate needs.

For all these New England troops, however, arms and ammunition were in short supply even though efforts had been made to accumulate them. The available weapons were mostly English military muskets—known colloquially as Tower or Brown Bess muskets—left over from earlier wars, and domestically manufactured hunting weapons. The scarcity of gunpowder, lead (for musket balls), and paper (for cartridges) was severe. These shortages were immediate and severely limited the operations of the New England troops. It would take years for the domestic arms industry to become established despite the best efforts of local governments. In the interim, imports from France, other European nations, and Mexico City were needed.27

The New England army that assembled around Boston in the aftermath of Lexington and Concord reflected, in its modifications of European military institutions, nearly two centuries of American colonial experience. Its emergence was a microcosm of the evolution of colonial military institutions. The common colonial heritage explains why the four colonies adopted organizational patterns that were very similar; particular experiences and individual backgrounds account for the variations.

The initial American response to the possibility of armed confrontation with British authorities had been a strengthening of the militia. Each colony took steps to replace aged or unreliable leaders and to reorganize units for greater efficiency. Training was increased. By 1775 most colonies were able to restore the militia to a degree of defensive competence not seen for a century or more. As the crisis worsened, American leaders moved beyond the basic militia. They began to prepare provisional militia units that could muster at short notice and remain in the field for longer periods. Whether volunteer companies or minutemen, these units were a response to the same need to minimize economic disruption that seventeenth century colonists had faced. The New England army that came into being at the instigation of Massachusetts moved a step beyond the minutemen. Like its Provincial model, this regional force was composed of regiments standing apart from the militia system, although drawing heavily on it for its recruits.

The Massachusetts Provincial Congress had set the minimum force needed to meet the British threat at some 30,000 men. By July a substantial portion of that total had assembled around Boston.28 Not counting artillery and several regiments that had not reported to Boston, the New England force consisted of 26 infantry regiments from Massachusetts and 3 each from New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Connecticut. On paper these units had 99 field officers, 866 company and 144 staff officers, and 18,538 enlisted men. This total was more than 2,500 men below authorized levels. More importantly, it included 1,600 sick and almost 1,500 on furlough or detached duty. These regiments were still only partially organized. Only nine from Massachusetts had

27. David Lewis Salay, "Arming for War: The Production

of War Material in Pennsylvania for the American Armies of the Revolution"

(Ph.D. diss., University of Delaware, 1977), pp. 165-204; James Allen Lewis,

"New Spain During the American Revolution, 1779-1783: A Viceroyalty at

War" (Ph.D. diss., Duke University, 1975), p. 52; Orlando W. Stephenson,

"The Supply of Gunpowder in 1776," American Historical Review 30

(1925):271-81; and Neil L. York, "Clandestine Aid and the American Revolutionary

War Effort: A Re-Examination," Military Affairs 43 (1979):26-30.

28. Record Group (RG) 93, National Archives (general

return, main army, 19 July 1775).

reached a paper strength of 95 percent; five were below 80 percent of their authorized levels and were, therefore, of questionable combat value.

These deficiencies were due in part to the lack of any centralized control over the army, or, rather, the collection of separate armies. The forces raised by each of the New England colonies in response to Massachusetts' call for assistance arrived piecemeal and were assigned positions and responsibilities around Boston according to the needs of the moment. The only coordination was furnished by a committee form of leadership. The Massachusetts commanders established a council of war on 20 April, and senior officers from the other colonies joined it as they arrived. Although it worked closely with the Massachusetts civil authorities, the council did not really command; it merely worked out consensus views. In practice this arrangement not only prevented effective planning but blocked the individual regiments from making their needs known. Incomplete information proved to be a major problem in the early months of the Boston siege.29

On 17 June the regional army fought its first engagement, a battle which revealed its weaknesses and its strengths. The council of war decided to apply pressure on the Boston garrison by occupying dominating hills on Charlestown Peninsula. It did not prepare an adequate plan, committing units piecemeal without sufficient ammunition or a clearly delineated chain of command. The British decided to launch a frontal assault in the hope of demoralizing the New Englanders. From the security of hasty fieldworks the defenders shattered two attacks with accurate musketry. A third assault drove them from the peninsula. Sir William Howe, staggered by a 42 percent casualty rate, realized he could not afford to let the colonists again fight from prepared positions since that advantage compensated for many of their weaknesses. He reported to his superiors in London after the battle: "When I look to the consequences of it, in the loss of so many brave Officers, I do it with horror—The Success is too dearly bought."30

The New England army had been defeated, although it had inflicted heavy losses on the enemy. The colonists had to find solutions to the problems highlighted by the battle, but it was already clear that these solutions required a national army. The search turned to Philadelphia where the Continental Congress was in session.

29. William Henshaw, The orderly book of Colonel William Henshaw,

of the American army, April 20-September 26, 1775 (Boston: A. Williams,

1881), pp. 13-39.

30. John Fortescue, ed., The Correspondence of King George

the Third from 1760 to December 1783, 2d ed., 6 vols. (London: Frank Cass

& Co., 1967), 3:220-24.

page updated 4 May 2001