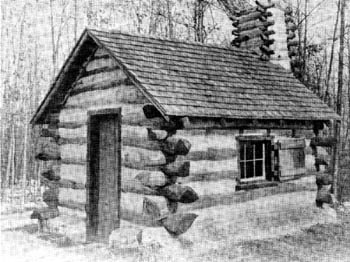

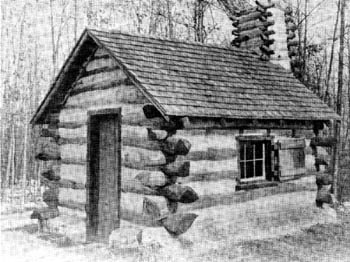

RECONSTRUCTION OF SOLDIERS, HUT AT VALLEY FORCE STATE PARK

Water Transportation

Handicapped by the difficulties of land transportation, the Quartermaster's Department early adopted the policy of using water routes wherever possible, primarily to expedite the movement of supplies but also, on occasion, of troops. The department was following an established practice, for the American colonists from pioneer days had utilized the country's navigable waters for travel and trade. The first settlers had built small boats-schooners, sloops, and piraguas-to sail the bays and coastal waters that separated, settlements. When they pushed inland, they used rivers as water routes. On the larger rivers sloops and schooners were common, but simpler boats-canoes, skiffs, pirogues, and bateaux-also furnished a ready means of transportation.

At the beginning of the Revolution when the Continental Army lay before Boston, the Quartermaster's Department had little need for water transportation. Nevertheless, even in 1775 the Quartermaster General included 50 pounds per month for boat repair in a monthly estimate of expenses in his department.1 Once the British evacuated Boston, Washington wanted to dispatch his troops quickly to New York. He ordered Quartermaster General Thomas Mifflin to Norwich, Connecticut, to make arrangements with Brig. Gen. William Heath and Brig. Gen. John Sullivan for the embarkation of their brigades and to contract for such transports as were necessary for the movement of the troops with their stores and equipment.2 A considerable number of transports were used. General Sullivan, for example, utilized twenty-three vessels in bringing his troops down Long Island Sound.3 Following the arrival of Washington's army in New York in the spring of 1776, the Hudson River became a vital supply artery, and boats of every description were much in demand. In time the Quartermaster's Department established a policy of engaging privately owned sloops and schooners whenever possible and of constructing and maintaining govemment-owned boats only when necessary. Generally, the latter were bateaux, scows, and barges.

The first widespread use of water transportation, however, antedated

1. Force, Am. Arch., 5th set., 2:1318.

2. Fitzpatrick, Writings of Washington, 4:429-30 (to Mifflin, 24 Mar 76).

3. Douglas S. Freeman, George Washington, 6 vols. (New York, 1948-52), 4:77.

129

Quartermaster activity on the Hudson. It occurred in the Northern Department in 1775 when boats were used to transport both men and supplies, though this effort was not under the direction of the Quartermaster's Department. Late in June Congress ordered Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler, commander of the Northern Department, to build boats for securing the waters adjacent to the captured forts of Ticonderoga and Crown Point and for dispatching an expedition into Canada.4 With the arrival of Washington in New York, the Quartermaster's Department assisted Schuyler by shipping up the Hudson nails, oakum, junk, and other supplies needed to build boats. The latter included bateaux, piraguas, and other vessels for use on Lake Champlain.5

While Schuyler coped with the problem of providing water transportation in the Northern Department, Assistant Quartermaster General Hugh Hughes contracted with the masters of privately owned sloops on the Hudson to deliver supplies to Washington. No example of these contracts has been found, but vessels apparently were usually engaged by the day. Their tonnage and the time they were employed were recorded, and payment was at a rate of so much per ton per day. When settlement, for example, was to be made for the vessels used in the Yorktown campaign, Superintendent of Finance Robert Morris considered that the price for transports should not exceed one shilling per ton. Vessels, however, might also be "engaged freight at a price per Barrel." On the Potomac River in the fall of 1781, the cost ran "3 [shillings] pr Barrel Virginia Currency."6 On the Hudson and later in the Yorktown campaign, sloop masters and their hands were allowed to draw rations; the cost was deducted from the final settlement due the owner for the use of his boat and from the wages paid the crew.

In addition to hiring vessels to transport supplies, the Quartermaster's Department in June 1776 began building boats. In anticipation of the arrival of the British at New York, Washington instructed Hughes to build six gondolas, or row galleys. Hughes sent out a purchasing agent to Staten Island, New York; to Elizabethtown, Rahway, and Newark, New Jersey; and to other nearby towns to contract for ship timber and two-inch planks, knees, scantlings, and oars. Benjamin Eyre was engaged to build these gondolas as well as bateaux. Hughes called on the various town committees

4. (1) JCC, 2:109-10 (27 Jun 75). (2) For logistical problems involved in transporting provisions for 10,000 men from Albany to St. John's in Canada, see Force, Am. Arch., 4th ser., 6:565-66.

5. (1) Hugh Hughes Letter Books (to Schuyler, 17 and 31 May 76). (2) Washington Papers, 27:106 (return, 4 Jun 76). (3) Fitzpatrick, Writings of Washington, 5:74-75 (to Schuyler, 22 May 76). (4) Force, Am. Arch., 4th set., 6:562-63 (Maj Gen Israel Putnam to Washington, 24 May 76).

6. (1) Morris Letter Book B, fols. 412-13 (to Deputy Quartermaster Donaldson Yeates, 28 Jan 82). (2) RG 93, Pickering Letters, 82:133 (to Assistant Deputy Quartermaster Joshua George, 23 Nov 81).

130

to assist his purchasing agent, and he sent another agent up the Hudson to obtain charcoal.

Although Hughes acted vigorously, the construction of boats did not advance to the point where the department could meet Washington's needs in the New York campaign. To enable the troops to accomplish the retreat from Long Island under cover of night, Hughes had to impress "all the Sloops, boats, and water craft from Spyghten Duyvil in the Hudson, to Hellgate on the sound."7 As the main army moved into New Jersey, Congress recommended that the Pennsylvania Council of Safety send one of its galleys along the New Jersey shore of the Delaware River from Philadelphia to Trenton to move all types of river craft to the Pennsylvania side in order to prevent their use by the enemy.8 Boats available for Washington's use were still largely those that could be impressed to meet specific needs.

In the course of the war the Continental Army often had to cross rivers. There were few bridges of any sort; such as did exist were primitive structures built over small creeks.9 There were no permanent bridges over broad rivers. Where possible, Washington's army used so-called floating bridges. When the British pressed their campaign in New York in 1776, for example, Washington sent an urgent request to William Duer to procure six anchors and cables of the size commonly used by sloops, in order to moor boats together as a bridge across the Harlem River.10 The troops of the Comte de Rochambeau and Washington marched over such floating bridges on their way to Yorktown in 1781.11 Where states maintained and operated floating bridges, as Pennsylvania did on the Schuylkill River, agreements were made between the state and the Quartermaster's Department for their use.12

Passage across broad rivers in the Revolutionary War was more commonly accomplished by the use of ferries. Those that were privately owned and operated were usually named for the owner, such as Wright's Ferry on the Susquehanna, Watkins' Ferry on the Potomac, and Coryell's Ferry on the Delaware. Use of private ferries required the payment of ferriage charges. Early in 1779 Quartermaster General Nathanael Greene entered

7. (1) Fitzpatrick, Writings of Washington, 27:461 (to Hughes, 22 Aug 84). (2) Hugh Hughes, Memorial and Documents in the Case of Colonel Hugh Hughes (Washington, 1802), p. 9 (Hughes to Washington, 31 Jul 84).

8. JCC, 6:1000 (2 Dec 76).

9. Early Pennsylvania legislation, for example, called for such bridges to be ten feet wide with a rail on each side. Dunbar, A History of Travel in America, p. 177.

10. Force, Am. Arch., 5th ser., 2:931 (Tench Tilghman to Duer, 7 Oct 76).

11. Thomas Scharf and Thompson Westcott, History of Philadelphia, 3 vols. (Philadelphia, 1884), 3:2141.

12. The first floating bridge on the Schuylkill was built under the direction of Maj. Gen. Israel Putnam, who was sent to Philadelphia in December 1776 "to superintend the works and give the necessary directions" to fortify the city as the British approached. When the British occupied the city in 1777, the Continental troops removed the bridge. When the British subsequently evacuated the city, they left intact a floating bridge which the Continental Army took over and

131

into an arrangement with John Coryell for the use of his ferry. Ferry rates varied according to the size of the river to be crossed. For the use of the Trenton Ferry, Deputy Quartermaster John Neilson agreed to pay its owner one half the price he received from private individuals.13 On the Hudson and elsewhere there were also public ferries, owned by the Quartermaster's Department and operated by ferrymen who worked for the department. These ferries provided free service for the passage of Continental personnel and property.14

It was the responsibility of the Quartermaster General to see that all ferries were in readiness when troops moved out on campaigns. It was considered advantageous, too, if a quartermaster could locate a ford and thus eliminate the delays occasioned by the use of a ferry. To accomplish his preparations, the Quartermaster General also might have troops familiar with the handling of boats detailed from the line to position bateaux, scows, and barges in readiness for ferriage.

The Quartermaster General sent out agents to survey roads. His agents also inspected bridges, made reports on needed repairs, and noted where new bridges might have to be built. He appealed to the states for aid, including the use of militia to repair roads and bridges. On the march a party of "pioneers," detailed by the commanding general of a division, usually moved in front of the column to assist the artificers in repairing bridges and bad places in the roads. The artificers took their orders from the Quartermaster General.15 It was the spring of 1782, however, before Congress authorized a Corps of Pioneers. It took this action in response to a proposal made by General Greene, then commanding the Southern Army, but it limited the Corps of Pioneers to one year's service with the Southern Army.16 No such corps served with the main Continental army.

utilized. This use led to an exchange of views about the bridge early in 1779 between the Quartermaster's Department and the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania, which was settled when Greene proposed paying a rent set by the state if the state reimbursed the department for the repairs it made to the bridge. When a freshet carried away the bridge early in 1780, Deputy Quartermaster General John Mitchell offered to replace it and keep it in repair for a year on condition that Continental troops, teams, and cattle be allowed to pass free of toll. The council accepted this offer and made the department responsible for the operation of the bridge and for the payment of a rent of 700 pounds a month, which was to be collected from private users of the bridge according to a schedule of fees set by the council. (1) Fitzpatrick, Writings of Washington, 6:340. (2) APS, Greene Letters, 8:87 (Joseph Reed to Greene, 4 Feb 79); 4:78 (Pettit to Greene, 20 Feb 79). (3) RG 11, CC Papers, item 173, 4:71 (Greene to Reed, 4 Feb 79). (4) Minutes of the Provincial Council of Pennsylvania, 13 vols. (Harrisburg, 1850-53), 12:269 (6 Mar 80).

13. (1) APS, Greene Letters, 9:107 (Reed to Greene, 28 Jun 79). (2) RG 93, Pickering Letters, 82:100-101 (to Deputy Quartermaster Claiborne, 17 Oct 81).

14. Ibid.

15. (1) Ibid., 82:167-68 (to Phillip Pye, 2 Aug 81). (2) Fitzpatrick, Writings of Washington, 12:90-91 (GO, 18 Jun 78); 23:69-71 (to Maj Gen Benjamin Lincoln, 31 Aug 81).

16. (1) RG 11, CC Papers, item 149, 1:175-78 (Greene to Pickering, I Mar 82). (2) JCC, 22:148-49 (26 Mar 82).

132

The Boat Department

When Nathanael Greene became Quartermaster General in 1778, he sought to centralize control by placing all matters relating to the construction and hire of boats and the employment of necessary personnel under the direction of a Boat Department. Little is known of the nature of its organization, but Benjamin Eyre, who had been building boats for the main army as early as 1776, became "superintendent of naval business" for the Quartermaster's Department, as Assistant Quartermaster General Charles Pettit expressed it.17 Greene contracted with Eyre for his services as superintendent and apparently gave him, among other duties, authority to operate all government ferries and to pay all expenses in connection with their operation and maintenance.18 Superintendent Eyre's authority, however, was exercised primarily in the Middle Department. On I July 1779 he submitted a return of the boats that he had built, their stations, the number of men employed in the Boat Department, and the amount disbursed in building boats from 1 May 1778 to 1 May 1779, the first year of his superintendency.19 The boats-four schooners, seventeen Durham boats, and a number of scows, flat-bottomed boats, bateaux, and rowboats-were located at Middletown and Wright's Ferry on the Susquehanna, at Watkins' Ferry on the Potomac, at Reading and the falls of the Schuylkill, at Coryell's Ferry and other places on the Delaware, and at Philadelphia.20

On 26 June 1779 the Boat Department employed 17 shipwrights under an assistant at Philadelphia; 2 assistants and 3 foremen directed the work of 65 shipwrights at Fort Pitt. The department also employed 125 men, including an assistant and 5 foremen, at Middletown and at Watkins' Ferry on the Potomac.21 Except for one assistant who was paid a commission, all of these men were salaried. An assistant was paid 20 dollars a day; a foreman, 15 to 16 dollars a day; and a shipwright, usually 12 dollars a day. Elsewhere, Greene's deputy in Connecticut, Nehemiah Hubbard, directed all boat activities for the Quartermaster's Department on the Connecticut River, as Deputy Quartermaster General Udny Hay did on the Hudson. Deputy Quartermaster General Morgan Lewis was responsible for water transportation in the Northern Department.

17. APS, Greene Letters, 4:78,(20 Feb 79).

18. Ibid., 4:83 (Pettit to Greene, 10 Feb 79); 11:7 (Greene to Pettit, 14.Feb 79). Whether Eyre was paid a commission or a salary for his services is not known.

19. (1) Ibid., 8:21. (2) Washington Papers, 3:92 (return, I Jul 79).

20. A Durham boat was a keelboat shaped like an Indian bark canoe-60 feet long, 8 feet wide, and 2 feet deep -which carried a mast with two sails and a crew of five. One steered, and two on each side pushed the boat forward with setting poles. It was named after its builder, Robert Durham of Pennsylvania, who had begun building them about 1750 for use on the Delaware River. Dunbar, A History of Travel in America, p. 282.

21. See APS, Greene Utters, 4:104, 111, for returns.

133

When Timothy Pickering became Quartermaster General in 1780 and made economy his watchword, the Boat Department ceased to exist. Pickering saw the need for a harbor master on the Hudson, where many large craft were employed, and he permitted Hugh Hughes to retain one. He urged a reduction of personnel at public ferries, maintaining that only one superintendent was necessary at each ferry, not one on each side of the river.22

Once it had acquired a number of boats for Army use, the. Quartermaster's Department in the winter months customarily laid up all boats not necessary for the use of the troops, such as those for the garrison on the Hudson, in order to preserve them for the next year's campaign. Ideally, winter was also the time for making repairs as well as building new bateaux and other boats. After 1778, however, the Quartermaster's Department was always so hampered by a lack of funds that such work could not be regularly accomplished.23 In consequence, when a campaign required the use of water transportation, preparations had to be made in great haste.

In the fall of 1779, for example, unofficial accounts that the fleet of Admiral Jean, Comte d'Estaing, was nearing the coast produced a flurry of activity in the Boat Department inasmuch as the reports led Washington to hope for a joint campaign against New York. In September Quartermaster General Greene ordered Deputy Quartermaster General Hay to build and repair flat-bottomed boats and directed, Capt. Moses Bush at Middletown, Connecticut, to build a number of river scows with higher than customary sides in order to accommodate cannon and wagons.24 Washington requested Greene to ready all public boats on the Hudson and bring them down from Albany to West Point and to collect all public boats on Long Island Sound. He further directed him to have as many other boats in readiness as Greene judged would be needed. He approved a plan proposed by Greene to have Superintendent Eyre in Philadelphia employ as many ship carpenters as were willing to engage "in the expedition" that was to be sent to build boats on the Hudson. 25 Some, members of Congress later expressed much dissatisfaction with the high wages Eyre had allowed the carpenters. While admitting that the wages were enormous, Assistant Quartermaster General John Cox insisted that they were not more than what merchants were paying at the time Eyre engaged the men.26 To further expedite boat building, Washington ordered all noncommissioned officers and privates in the brigades near West Point who were ship carpenters to report to the Quartermaster General. Deputy Quartermaster General Hay at Fishkill divided these men into

22. RG 93, Pickering Letters, 82:15-21 (to Hughes, 12 Jul 81).

23. (1) RG 11, CC Papers, item 173, 2:149 (Greene to Hay, 16 Nov 79). (2) Fitzpatrick, Writings of Washington, 18:364 (to Hay, 15 May 80); 459-60 (to Greene, 31 May 80).

24. RG 11, CC Papers, item 173, 2:95-96 (Greene to Hay, 12 Sep 79).

25. Fitzpatrick, Writings of Washington, 16:341-42, 423 -24 (to Greene, 26 Sep and 2 Oct 79).

26. APS, Greene Letters, 9:31 (Cox to Greene, 2 Nov 79).

134

small companies of ten men each. To stimulate production, he promised a reward to the company that turned out the most bateaux. Production, however, was hampered by a lack of boards and planks, which early in October had not yet arrived from Albany.27

Greene requested Deputy Quartermaster General Morgan Lewis to hurry the movement of these supplies. Lewis, operating on orders received earlier from Greene, had been repairing and building boats. Early in October he informed Greene that he had sent sixteen bateaux to Fishkill and expected to send forty more within a fortnight. Furthermore, he had called in all boats from the Mohawk River and had employed every available carpenter at Schenectady and Albany.28

In Connecticut Deputy Quartermaster Hubbard gathered scows at the government shipyard at Chatham. After consulting with Captain Bush, he reported to Greene that only sixteen of them were suitable for the purpose intended. They would be made ready, Hubbard wrote, adding that Bush thought that if time permitted he could build one scow a day for ten days. Hubbard already had set the sawmills in operation to provide 30,000 feet of planks in ten days. He needed cash, however, to pay the wages of carpenters, who would not engage to work on the scows unless they were paid every Saturday night as in private boatyards. The work did not proceed as fast as Hubbard had expected. At the end of the first week in November, five scows had been completed and twelve were on the stocks. "The lumber of which they are made," he noted, "was standing in the woods when I received my orders."29 But by that time the anticipated cooperation with the French had failed to materialize, and the boat preparations came to -a halt-much to Deputy Quartermaster General Hay's relief. He reported that 193 bateaux had been built, but he was worried about the scarcity of boards available for building barracks, repairing wagons, and making arms chests.30

When Washington again hoped for an allied operation by land and sea against the British in 1781, there were few boats on hand, and most of these were in need of repairs. As usual, the major part of the boats had been laid up during the winter months. Deputy Quartermaster Hughes submitted a report in April 1781 on all the government-owned boats on the Hudson and Mohawk Rivers. Most of these-195-were bateaux; only 18 were in good condition, but the major part were reparable. Hughes listed 2 barges, 2 scows, and 3 skiffs in good condition. Of the 12 flat-bottomed boats, 6 were in good condition and 5 were reparable. There were also 2 whaleboats, both

27. (1) Fitzpatrick, Writings of Washington, 16:424 (6 Oct 79). (2) APS, Greene Letters, 3:50, 529 (Hay to Greene, 7 and 9 Oct 79). (3) RG 11, CC Papers, item 173, 4:231 (Greene to Lewis, 9 Oct 79).

28. APS, Greene Letters, 3:82 (Lewis to Greene, 7 Oct 79).

29. Ibid., 3:77, 81 (Hubbard to Greene, I I and 20 Oct 79); 9:63 (same to same, 9 Nov 79).

30. Ibid., 8:52 (Hay to Greene, 29 Oct 79).

135

of which were in need of repairs. Of the 12 gunboats, only one was in good condition, but 10 were reparable. A sloop and a pettiauger were in good condition, but of the 3 schooners, 2 needed repairs.31 The report was not unusual. It certainly indicated that the water transportation that would be required in any cooperative effort with the French was not ready.

By 7 June Washington was stressing the "almost infinite importance" of having the boats ready for use and urging Quartermaster General Pickering to take every necessary measure. Three days later, still greatly concerned about the preparation of boats, he requested a return listing all boats from Albany to Dobbs Ferry; they were to be classified as fit for service, reparable, or irreparable. Moreover, he wanted all those fit for service to be collected at once at West Point. Should Pickering not have enough tar for repair work, he was to impress it under a warrant either from the governor of New York or the Commander in Chief.32

In this emergency General Schuyler offered to build 100 bateaux in 20 days. Washington requested Pickering to lend Schuyler every assistance in completing the much needed boats.33 To provide the total of 200 bateaux required for the campaign, an additional 100 bateaux were to be built in 30 days by artificers under the direction of the Quartermaster's Department. Nails and oakum were in great demand, and Pickering urgently appealed to Deputy Quartermasters Samuel Miles and John Neilson to send these supplies from Pennsylvania and New Jersey, promising payment to the wagoners delivering them. He also undertook to obtain assistance from Superintendent of Finance Robert Morris. Miles had already procured and provided a considerable quantity of spikes and deck nails. Although the required small-sized nails were not available in Pennsylvania, Pickering anticipated that he would still be able to meet Schuyler's needs.34 The search for nails went on. An assistant deputy in New Jersey reported that a Mr. Ogden could furnish 300 pounds weekly for hard money or "the Exchange," an equivalent amount of paper money. This quantity was "pitiful," Pickering lamented, when he needed 1,600 pounds of 8-penny nails and 2,200 pounds of 10-penny nails within 20 days.35

In mid-July Washington requested Schuyler to send down the Hudson all the boats that were finished. Most of the allied army was then gathered in New York. On 14 August, however, Washington learned that Admiral de Grasse planned to sail to the Chesapeake Bay. When Washington then boldly shifted his plans from an attack on the British in New York to an

31, Washington Papers, 169:103 (return, 2 Apr 81).

32. Fitzpatrick, Writings of Washington, 22:177-78, 1%-97 (to Pickering, 7 and 10 Jun 81).

33. Ibid., 22:235 (to Schuyler, 19 Jun 81); 275-76 (to Pickering, 28 Jun 81).

34, (1) RG 93, Pickering Letters, 82:1-3 (to Neilson, 29 Jun 81). (2) Washington Papers, 178:45 (to Jonathan Trumbull, Jr., 29 Jun 81). (3) See also Fitzpatrick, Writings of Washington, 22:288 (to Schuyler, 30 Jun 81).

35. RG 93, Pickering Letters, 82:4-5 (to Aaron Forman, I Jul 81); 5 (to Hughes, same date).

136

entrapment of Cornwallis in Virginia, he wrote to de Grasse on 17 August that it would be essential for him to send up to the Elk River at the head of Chesapeake Bay all his transports and other vessels suitable for conveying the French and American troops down the bay. Washington assured him that he would endeavor to send as many vessels as could be found in Baltimore and other ports to the Elk, but he warned that he had reason to believe that they would be few in number. At the same time, he wrote to Robert Morris and requested that he take all measures for securing these vessels. Washington added that he was directing Pickering to collect all the small craft on the Delaware River to transport troops from Trenton to Christiana Bridge.36

In the meantime, Pickering was making preparations for ferrying the troops across the Hudson. It took a letter from Washington, however, to induce Maj. Gen. Alexander McDougall to detail the 150 men that the Quartermaster General had requested to bring 30 boats from Wapping Creek to King's Ferry. Pickering also urged Deputy Quartermaster Hughes to send scows and every other boat that he could secure.37 On 19 August Washington dispatched Pickering to King's Ferry to supervise the transportation of the troops-some 4,000 French and 2,000 American-across the river with their artillery, stores, and baggage. Within two days the Americans had crossed .the Hudson; only some wagons of the Commissary and Quartermaster's Departments remained behind so as not to delay the passage of the French troops. The crossing of men and supplies was completed by 27 August. To deceive the enemy, Washington mounted 30 flatboats, each able to carry 40 men, on carriages and sent them across the river with the French troops, judging that they also would be useful to him later in Virginia. These boats, together with some clothing, entrenching tools, and other stores, were placed in the care of Col. Philip Van Cortlandt.38

Transportation was a primary function of the Quartermaster General, but the movement of troops and their stores by water to Yorktown was for the most part accomplished by direct orders from Washington to subordinates in the Quartermaster's Department and to line officers of the Continental Army. Quartermaster General Pickering arrived in Philadelphia on 30 August, where he remained for the next week, sending out directions to his subordinates. By that time, Washington was demanding his presence with the American detachment. Pickering arrived at Head of Elk on 7 September and at Williamsburg, Virginia, after an overland journey, on 16 September 1781.

36. Fitzpatrick, Writings of Washington, 23:10-11 (to de Grasse, 17 Aug 81); 11 (to Morris, same date).

37. (1) Ibid., 23:16-17 (to McDougall, 18 Aug 81). (2) RG 93, Pickering Letters, 127:226 (to Hughes, same date).

38. (1) Fitzpatrick, Diaries of George Washington, 2:255-57. (2) Fitzpatrick, Writings of Washington, 23:48-49, 61 (to Van Cortlandt, 25 and 28 Aug 81).

137

Hearing late in August that de Grasse might already be in the Chesapeake Bay, Washington realized that there was no time to lose in making preparations for water transportation from Trenton to Christiana Bridge and from Head of Elk down the bay to Virginia. The Quartermaster General was then still on the Hudson, so Washington himself wrote to Deputy Quartermaster Miles in Pennsylvania, directing him to engage immediately all craft suitable for navigating the Delaware River that could be found in Philadelphia or in the creeks above and below it and to call on the Superintendent of Finance for any help or advice. He asked Morris to use his influence in Baltimore to get any vessels in that port to come up to Head of Elk to assist in transportation. He supplemented. these efforts by writing to Governor Thomas Sim Lee of Maryland, requesting that he aid Morris, who had "the principal agency in procuring water transportation."39

At the same time, Morris requested the Baltimore merchants Mathew Ridley and William Smith to engage Chesapeake Bay craft. On 28 August he advised Ridley that he was sending an express to Deputy Quartermaster Donaldson Yeates at Head of Elk to gather as many vessels as he could at that place by 5 September and to apply to Ridley and Smith for any needed advice and assistance. Transports for 6,000 to 7,000 men were to be hired on the best terms that could be obtained and on credit if possible. In a postscript to Ridley, Morris took care to add that procurement of vessels was the proper business of the Quartermaster's Department. If Ridley and Smith engaged any vessels before Yeates arrived at Baltimore, the firm was to turn them over to the deputy quartermaster.40

Washington thought there might be insufficient water transportation between Trenton and Christiana Bridge. He advised Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln, who was in charge of embarkation at Trenton, that the delicate question would then arise of how to apportion the craft equally between the French, and American troops. Rochambeau, however, elected to have the French troops march by land from Trenton to Head of Elk, thereby making available a larger number of craft for transporting American baggage and troops.41 Still fearful that there would not be sufficient craft to embark all the American troops, stores, and baggage, Washington directed General Lincoln to confer with Col. John Lamb of the Artillery to determine which cannon, carriages, ordnance stores, and baggage would be most cumbersome and heavy to transport by land and to give preference to sending these stores and equipment by water. He further instructed Lincoln to send from Trenton 100 picked men who were experienced in water transportation to

39. Ibid., 23:50-52 (to Morris, 27 Aug 81); 57-58 (to Gov Lee, 27 Aug 81).

40. (1) Morris Letter Book A, fols. 290-91 (to Yeates, 28 Aug 81); 291-92 (to Mathew Ridley, same date). (2) For a register of the vessels taken into service by Yeates, including their tonnage, valuation, and daily pay, as well as the valuation of the slaves employed on them, see RG 93, Misc Numbered Docs 26800.

41. Fitzpatrick, Writings of Washington, 23:59-60, 71-72 (to Lincoln, 28 and 31 Aug 81).

138

assist in embarking troops and forwarding stores from Philadelphia. He was also to appoint an officer to superintend the embarkation at Trenton and another to supervise the debarkation of men and supplies at Christiana Bridge. The latter was to be accompanied by a number of troops who were to assist in unloading and then forwarding stores and baggage at the debarkation point. Washington enclosed a list of craft being sent to Trenton. A week later he sent Lincoln specific instructions for combat loading the boats.42

After arriving at Philadelphia, Pickering on 31 August advised Lt. Col. Henry Dearborn, deputy quartermaster with the main army, that thirty teams were bringing boats. He directed that the carpenters were to repair any damages the boats might have sustained. For this purpose Deputy Quartermaster Neilson was sending a few barrels of tar. Pickering ordered that fifteen of the best boat carriages be selected, disassembled, and put on board the boats, to be forwarded, with such troops as could be carried, to Christiana Bridge. From there all the boats could then be carried overland to Head of Elk in two trips; if only ten boat carriages could be used, three trips would do the job. To prevent delay in putting the boat carriages back together, he directed that all the parts of a particular carriage were to be marked alike. Wagonmaster Thomas Cogswell's branding iron, he suggested, would be most convenient for marking.43

Continuing his supervision of transportation, Pickering wrote to Deputy Quartermaster Yeates that the troops would embark at Trenton on 1 September and arrive at Christiana Bridge as soon as wind and tide permitted. He was to give every assistance in landing stores, and Pickering informed him that Brig. Gen. Moses Hazen was going to Christiana Bridge to superintend the business there. Under instructions from Washington, General Ham was to speed the transportation of supplies to Head of Elk. Colonel Lamb of the Artillery was to assort and forward the ordnance stores that ought to be sent first.44

As Washington had anticipated, there were insufficient transports to embark all the troops at Head of Elk. He appealed to the "gentlemen of the eastern shore of Maryland" to send all their vessels to Baltimore in order to transport troops down the bay from that port. The time it would take to march them by land to Williamsburg could not be spared. A week later he requested the assistance of Admiral de Grasse in moving the troops down Chesapeake Bay. Persistent and strenuous efforts brought the troops to Virginia. On 23 September Washington wrote from Williamsburg to Maj. Gen. William Heath

42. Ibid., 23:69-71 (to Lincoln, 31 Aug 8 1). The list of boats, probably taken from one made by Miles of water craft engaged at Philadelphia on 30 August 1781, showed a total of 31 craft--4 wood flats, 4 schooners, and 23 sloops-with an estimated total capacity of 4,150 men. See 23:98 -101 (to Lincoln, 7 Sep 81).

43. RG 93, Pickering Letters, 82:176-78 (to Dearborn, 31 Aug 81).

44. (1) Ibid., 82:180 (to Yeates, I Sep 81). (2) Fitzpatrick, Writings of Washington, 23:78 (to Hazen, 2 Sep 81).

139

that those who had departed from Head of Elk were disembarking and the rest were expected shortly.45

In the operation against Cornwallis, Pickering began by issuing orders to various masters of sloops to bring corn from the James River and flour and forage from Head of Elk along with any other stores still remaining there.46 Early in October Governor Thomas Nelson of Virginia designated Commodore James Barron to take over the direction of the vessels employed in this service, and Pickering's orders were thereafter sent to Barron. Pickering directed him not only to send vessels to the several ports and landings where provisions, forage, and stores were lodged but also to furnish any vessels requested by Wadsworth and Carter, agents for the French army. He was to send vessels to such places as they designated for supplies for that army. Pickering ordered Barron to keep a record of the time of departure and arrival of every vessel. He was to report any delays or improper management by masters of vessels so that they could be discharged, and he was to discharge any vessels found unserviceable. Pickering directed him especially to keep an exact record of services performed for the French. He authorized Barron to issue rations to the crews of the vessels by giving orders to the nearest commissaries.47 Barrron worked closely with Pickering in discharging vessels unfit for further service and in forming others into squadrons to bring supplies from different ports. During the course of the campaign, a considerable number of schooners and sloops engaged in transporting forage, provisions, and military stores were impressed.48

When the American detachment dispersed after the surrender of Cornwallis, Washington instructed Pickering to send the sick and the artillery pieces and ordnance stores by transports to the north. He left it to the Quartermaster General to make the necessary arrangements.49 To Pickering also fell the task of settling the accounts for water transportation. He communicated with Ridley and Pringle of Baltimore, who had been authorized by Morris to settle with the owners and masters of vessels employed on the Chesapeake Bay in the Yorktown expedition. Although final settlement for these vessels could not be made until the accounts of monies advanced and provisions furnished were received, Pickering proposed paying half their hire as soon as possible to relieve any financial distress. To expedite final settlement, he requested Commissary General of Issues Charles Stewart

45. (1) Ibid., 23:96-97 (circular, 7 Sep 81); 116-17 (to de Grasse, 15 Sep 81); 129-30 (to Heath, 23 Sep 81), (2) For an estimate of vessels taken into transport service at Baltimore by Assistant Deputy Quartermaster David Poe, see RG 93, Misc Numbered Docs 26675.

46. RG 93, Pickering Letters, 82:207-08 (3 Oct 81).

47. Ibid., 82:208-11 (to Barron, 3 Oct 81).

48. See RG 93, Misc Numbered Docs 27593 (Return of Craft Impressed, 30 Oct 81); 27594 (Return of Craft Impressed into Continental Service by Capt George Webb, 29 Oct 81).

49. Fitzpatrick, Writings of Washington, 23:281-82 (to Pickering, 27 Oct 81).

140

to forward the accounts of all rations drawn by the owners of vessels.50 By November Morris had furnished some funds to Deputy Quartermaster Miles for settling transport hire and had authorized him to sell government owned schooners and pay the masters and men their wages.51 As the year ended, craft that had been assembled for the campaign had been dismissed, and during the remainder of the war the boats in use by the Quartermaster's Department dwindled to a few on the Hudson.

Sheltering the Troops

Providing shelter for the troops was an arduous and time-consuming responsibility of the Quartermaster General. Assisted by the Chief Engineer, he marked out encampment sites. His selection of a location for a winter encampment necessitated a considerable amount of riding about the

countryside. In his recommendations to the Commander in Chief, he took into account such factors as availability of water and woodland at the

proposed site, its accessibility for the delivery of supplies, and its defensive position.52 Laying out camps and assigning quarters was the initial task. The Quartermaster General also had to supply boards for the construction of barracks and huts, straw for bedding, firewood for cooking and heating, and tentage when the troops were in the field.

The troops at Cambridge in 1775 erected a variety of shelters for their protection. Rev. William Emerson found it "diverting to walk among the camps," for they were as different in their form as the owners were in their dress.

Some are made of boards, and some of sail-cloth. Some partly of one and partly of the other. Again, others are made of stone and turf, brick or brush. Some are thrown up in a hurry; others curiously wrought with doors and windows, done with wreaths and withes, in the manner of a basket. Some are your proper tents and marquees, looking like the regular camp of the enemy. In these are the Rhode Islanders, who are furnished with tent-equipage, and everything in the most exact English style.53

Such was the unmilitary scene that Washington viewed upon his arrival to take command of the Continental Army. Among the tasks that early demanded the attention of Quartermaster General Mifflin was providing quarters for the troops during the siege of Boston. In the fall of 1775 he submitted to Washington an estimate for housing 12,000 troops.54 He proposed

50. RG 93, Pickering Letters, 82:109 (to Ridley and Pringle, 28 Oct 8 1); 111 (to Stewart, 28 Oct 81).

51. Morris Diary, 1:91 (22 Nov 81).

52. (1) Fitzpatrick, Writings of Washington, 4:514 (GO, 25 Apr 76); 8:492-94 (to Mifflin, 28 Jul 77); 17:118-19 (to Greene, 17 Nov 79). (2) See also Washington Papers, 120:72-73 (Biddle to Greene, 6 Nov 79). (3) RG 11, CC Papers, item 173, 2:281-84 (Greene to Washington, 23 Nov 79).

53. George Washington, The Writings of George Washington, ed. Jared Sparks, 13 vols. (Boston, 1834-37). 3:491.

54. Force, Am. Arch., 4th ser., 3:1045 (5 Oct 75).

141

building 90 barracks at Cambridge and 30 at Roxbury. Each barrack was to house 100 men. Divided into 6 rooms, each barrack was to be 90 by 16 feet in size. By any standards this barrack would provide very cramped quarters. Mifflin estimated that it would cost 12,000 pounds to build the 120 barracks. This sum included not only the cost of the materials but also the additional wages-20 shillings per month-that would be paid to the soldiers detailed to build the barracks. The Revolutionary soldier quickly found that bearing arms was only one of the duties he would be called upon to perform.

Washington concluded that winter would arrive before the troops could be housed in barracks. To shelter his troops, he considered it necessary to appropriate the homes of those citizens who had fled Cambridge, even though many were then returning. He therefore requested the Massachusetts General Court to take action.55 Although barracks were later built, initially the troops were quartered in private houses.

The construction of these first barracks in Cambridge subsequently raised a problem. Apparently the Quartermaster's Department had failed to enter into any agreement with the owner of the land on which they were built. In the summer of 1779 the owner began dismantling one of the barracks, converting it to his own use, and he threatened to take down all the others. The guard protecting the barracks and magazine confined the owner for an hour, whereupon the latter sued the guard. Failing to obtain any help from the Massachusetts General Court, Deputy Quartermaster General Thomas Chase appealed to the Quartermaster General for instructions. He reported that the barracks had sustained more than 50,000 dollars damage.

Greene advised Chase to negotiate with the owner and to enter into a contract that provided a reasonable compensation for the use of his land. Greene then appealed to the Continental Congress for some action that would ensure permanent security not only for barracks but for all types of government property. He complained that too many people were convinced that they had a right to apply to their own use any government property that "fell in their way, by accident or otherwise." Consequently, thousands of arms as well as various other military stores had been carried away. He suggested that Congress recommend to the states the enactment of laws which would permit the Quartermaster General or his deputies to appoint representatives who would fix the value and rent of the lands on which public buildings stood or were erected, the agreement being binding on both parties. He thought there also ought to be state laws that would impose large fines on inhabitants with government property in their hands who failed to report it to the nearest public agent within ten days after -it came into their possession.56 This

55 (1) Fitzpatrick, Writings of Washington, 4:17-18 (6 Oct 75). (2) Lacking tents, a, certain number of the Massachusetts troops who had first taken up arms had been accommodated in empty buildings of Harvard College and in empty houses. Allen French, The First Year of the American Revolution (Boston, 1934), p. 184.

56. RG 11, CC Papers, item 155, 1:154 (Chase to Greene, 1 Jul 79); 147-50 (Greene to Pres of Cong, 12 Jul 79).

142

problem of appropriation of government property was not resolved, although it became customary to contract for the use of such privately owned property as buildings, land, and ferries.

Late in November 1775 the Continental Congress resolved that the troops were to be supplied with fuel and bedding at its expense.57 The Quartermaster General therefore was responsible for providing wood, straw, and blankets as well as camp equipage. Mifflin in October had estimated that an allowance of 1 ½ cords of firewood per week per 100 men would lead to a consumption of 8,000 cords of wood in six months by Washington's army. The Quartermaster's Department almost at once encountered difficulty in issuing wood to the troops because little or none was brought to camp for sale. Washington suspected that the owners of wood were holding it from the market in order to create an artificial scarcity and raise prices. In response to his request for remedial measures, the Massachusetts General Court called on the selectmen of designated towns to supply wood daily according to quotas that it proposed. The New York Convention later came to the aid of the main army by purchasing and sending cords of wood for its use in 1776 when the troops had moved to New York.58

Lacking wood, soldiers in the field helped themselves to fences, trees, and even buildings near their camps. Washington ordered officers commanding the guards to be particularly attentive to prevent such depredations. Subsequently, axmen were detailed from brigades to march with the pickets when the main army moved. The axmen not only prepared timber for repairing roads but when the army arrived at a new encampment, they also cut firewood for their respective brigades. Working under the direction of brigade quartermasters, these men were relieved from all guard and other ordinary duty. However, when an action was expected, they delivered their axes to the brigade quartermasters and rejoined their units.59

Though some cords of firewood were obtained by contract, this method of supply appears to have been limited to providing for troops in barracks at posts. The more usual method throughout the war was to detail troops to cut the wood needed by the garrison or camp during the winter. The necessary axes, cross-saws, butte rings, and wedges were furnished by the storekeepers to the brigade quartermasters, who were held accountable for them.60

The Quartermaster's Department also provided entrenching tools, as well as froes, handsaws, augers, and other tools used in erecting huts.

57. JCC, 3:377 (27 Nov 75).

58. (1) Fitzpatrick, Writings of Washington, 4:17-18, 47-48, (to Mass. legislature, 6 and 27 Oct 75). (2) Force, Am. Arch., 4th ser., 3:1045 (estimate, 5 Oct 75); 4:1318 (2 Dec 75); 5th set., 3:207-08 (30 Sep 76).

59. Fitzpatrick, Writings of Washington, 5:12-13 (GO, 5 May 76); 9:286 (GO, 30 Sep 77).

60. (1) Ibid., 25:59-60 (to Pickering, 24 Aug 82); 134-36 (GO, 7 Sep 82). (2) RG 93, Pickering Letters, 84:97-99 (9 Sep 82).

143

Quartermasters issued tools only as needed by the troops, but, whether by intent or carelessness, the men frequently failed to return them. Such was the extent of this "embezzlement of the public tools" that Washington in June 1776 directed the Quartermaster General to have each tool branded with the mark "CXIII," meaning "the Continent and the thirteen colonies." After the colonies declared their independence, this brand was changed to "U.S." In the summer of 1776 Washington also introduced the idea of property accountability. All officers commanding a party or detachment detailed to work on any project were to be held accountable for the tools they received; any lost while in their care had to be paid for by the officers. A soldier who lost or destroyed a tool delivered to him had its price deducted from his next pay and in addition was punished "according to the nature of the offense." 61

The fall of the year usually found Washington concerned with the problem of providing shelter for his troops during the winter months. Anticipating the need for placing troops in barracks when the campaign of 1776 closed, Washington in September urged Quartermaster General Stephen Moylan to begin accumulating the materials necessary for building barracks at King's Bridge, New York, or nearby posts. As long as the enemy did not obstruct the Hudson, he pointed out, these materials could be readily shipped down it. Assistant Quartermaster General Hugh Hughes immediately dispatched a purchasing agent to obtain boards, shingles, bricks, lime, and other needed supplies. In addition, the agent was to engage three companies of carpenters; each was to consist of thirty men, a captain, and other officers, who were all promised the same pay and rations as those already in service.62

When Thomas Mifflin resumed the duties of Quartermaster General, efforts to construct these barracks went forward at an accelerated pace. He solicited the aid of the New York Convention in procuring boards. The latter sent out an agent authorized not only to purchase needed supplies but also to impress them if they could not be procured with the owner's consent.63 William Duer had expressed an interest in constructing the barracks, and Mifflin accepted his offer, hoping that the Quartermaster General's own agents consequently would have to spend little time on this business. Duer apparently acted as Mifflin's superintendent for building the barracks in New York, which, according to instructions received from the Quartermaster General, were to be "calculated for 2,000 men." Washington was then too preoccupied to give attention to either the construction or the precise location of these barracks. Mifflin, however, had consulted the general officers, who advocated building one set of barracks a mile or two east of the

61. Fitzpatrick, Writings of Washington, 5:157 (GO, 18 Jun 76); 7:284 (to Mifflin, 13 Mar 77).

62. (1) Force, Am. Arch., 5th ser., 2:257 (Tench Tilghman to Moylan, 9 Sep 76). (2) Hugh Hughes Letter Books (12 Sep 76).

63. Force, Am. Arch., 5th ser., 3:207-08 (30 Sep 76).

144

mouth of the Peekskill River and another set near the town of Fishkill. They proposed that the barracks be 36 feet long, 19 feet wide, and about 7 feet high in the upright on each side.64

Boards proved to be so scarce that a sufficient number could not be procured in time, and it became necessary to complete the barracks with mud walls. To expedite the completion of these winter quarters, Duer applied to the New York Committee of Safety for 100 militiamen to work on the construction. The committee ordered the men out, but it added that since they would be constantly on fatigue duty, they ought to be allowed three eighths of a dollar per day and Continental rations.65 The barracks were completed, but the main Continental army went into quarters in Morristown in the winter of 1776-77.

In the course of the war, barracks were built at various places-Trenton, Albany, West Point, and elsewhere. Carpenters among the companies of artificers employed by the Quartermaster's Department constructed the barracks. Not infrequently, however, carpenters among the troops were detailed to assist in the preparation of timber for joists, rafters, and the like.66 Once barracks were constructed, they were placed under the charge of the barrackmaster general in the Quartermaster's Department.67 There were deputy barrackmasters general in the military departments. They appointed barrackmasters, who were responsible for receiving and issuing candles, collecting and issuing firewood, and assigning space to those entitled to it. Occasionally, the barrackmaster also located quarters for soldiers in private houses. As might be expected, the number of barrackmasters increased to the point where Washington early in 1779 thought the barrackmaster general ought to be called upon for a list of his appointees so that the Quartermaster General would be able to determine their usefulness and what reductions in personnel might be made.68

Until 1779 control over barracks and responsibility for them had been vested in the Quartermaster General. Late in January of that year Quartermaster General Greene, to his surprise, received a letter from a barrackmaster general newly appointed by the Board of War. No report by the board setting forth its reasons for this action has been found, although it may be

64. Ibid., 5th ser., 2:1254 (Mifflin to Duer, 26 Oct 76).

65. Ibid., 5th ser., 3:302 (8 Nov 76).

66. (1) See Washington Papers, 88:63 (Pettit to Washington, 16 Oct 78). (2) In the winter of 1780 Private Joseph Plum Martin and his fellow soldiers arrived at West Point. They were quartered in old barracks until new ones could be built. They began work immediately. They went to a point six miles down the river to hew timber, carried it on their shoulders to the river, and then rafted it to West Point. They had completed this work when carpenters arrived to undertake the construction. By New Year's Day the new barracks were ready. George E. Sheer, ed., Private Yankee Doodle (Boston, 1962), p. 209.

67. JCC, 7:359 (14 May 77). This first regulatory act for the Quartermaster's Department set the pay of a barrackmaster general at 75 dollars a month.

68. Fitzpatrick, Writings of Washington, 14:65 (memo to Committee of Conference, _Jan 79).

145

surmised that the appointment grew out of a concern about barracks for Burgoyne's vanquished Convention troops, who were not the responsibility of the Quartermaster General. In any event, Greene received notice of this change not from the Board of War but from its new appointee, Isaac Melcher, who thought it advisable to clarify his duties to prevent misunderstandings with the Quartermaster's Department. Based on his reading of the orders he had received from the board, he considered that his principal duty was to provide and furnish barracks, storehouses, and other buildings on the application of the Quartermaster General or on the order of the commanding officer of a military department. He also believed that he was responsible for supplying such barrack utensils as were allowed and for furnishing wood, straw, soap, and candles. After an appeal for harmony between himself and Greene, he concluded by stating that his duty was principally confined to troops in quarters and that of the Quartermaster General to those in the field.69

Some months went by before Greene wrote to inquire about the Board of War's action. Whether Melcher was following the board's intent, or whether he had completely misunderstood his duties-and this seems likely since he also was taking over some supply duties of the Commissary General of Purchases-his responsibilities as barrackmaster general were thereafter restricted to the barracks in Philadelphia and to the barracks of the Convention troops in Virginia.70

Six months later, in the interest of economy, Congress abolished Melcher's department. Some two weeks earlier it had directed the Board of War to discharge immediately all supernumerary officers in that department. All duties were returned to the Quartermaster's Department, but with the admonition that they were to be performed without adding officers for the purpose.71 Thereafter quartermasters also served as barrackmasters.

Even the best barracks must have provided uncomfortable quarters. With bunks rising in tiers against the walls, the barracks were so ill-lit by the small candle allowance that men retired when darkness fell. Nor was there sufficient wood to provide adequate warmth, and vermin infested the straw used for bedding. Lacking tents in the summer of 1776, troops at Ticonderoga were lodged in the old barracks at the fort. General Schuyler wrote, "They are crowded in vile barracks, which, with the natural inattention of the soldiery to cleanliness, has already been productive of disease, and numbers are daily rendered unfit for duty." The Revolutionary soldier ignored sanitary regulations. Joseph Trumbull found the houses sheltering troops at Cambridge "so nasty" that men were growing sick and daily dying. Conditions were no better later in the war, for in 1780 Joseph Plum Martin, a

69. APS, Greene Letters, 1:275 (Melcher to Greene, 25 Jan 79).

70. See Washington Papers, 171:63 (Pickering to Alexander Hamilton, 20 Apr 81).

71. (1) JCC, 16:76 (20 Jan 80). (2) APS, Greene Letters, 2:181 (Benjamin Stoddert to Pettit, 26 Jan 80).

146

Revolutionary soldier, related how, until new barracks could be built, the troops were lodged in the old ones at West Point "where there were rats enough, had they been men to garrison twenty West Points."72

Melcher had considered it his duty to furnish barrack utensils-camp kettles, wooden pails, and similar equipment-but Pickering, whose service on the Board of War and as Quartermaster General made him much better informed, stated that barrack utensils had never been regularly supplied. The troops used the utensils they brought with them from the field. When the Secretary at War in 1782 considered issuing a regulation setting forth a formal allowance of barrack utensils, Quartermaster General Pickering judged it best to avoid doing so, for it would be difficult, if not impracticable, to supply the items. If any barrack utensils were to be supplied on a regular basis when the troops were in winter quarters, the demand, he pointed out, would be so great as to occasion considerable expense.73

Troops stationed at posts such as West Point or Trenton were garrisoned in barracks, as were those detailed to guard magazines of supplies. On occasion the dispersal of the troops during the winter resulted in some regiments being quartered in barracks. Generally, however, most of the Continental Army lived in the field, sheltered in tents during campaigns or in huts at winter encampments. Tentage was always scarce during the war. Dependent on the importation of duck for tents, Washington in 1775 wanted good care taken of the tents the troops had. As soon as the troops moved into winter quarters, he ordered the tents that had been in use delivered to the Quartermaster General. Thus was established the policy of turning in to The Quartermaster's Department all tents at the end of a campaign so that they could be washed and repaired by artificers under the department's direction and stored and reissued for use in the next campaign.74

The Continental Army in 1775 was not a disciplined force, and despite repeated orders Washington found tents "standing uninhabited and in a Disgraceful and Ruinous Situation" after some of his men had been quartered in houses in January 1776. Proper storage and maintenance of supplies was not noticeably improved at a later date. A visitor to Fishkill Landing in December 1776 found tar, tents, and other Continental stores "wasting to a great degree. " The dock was afloat with the tar; the tents were in a heap, wet and consequently rotting. Deputy Quartermaster General James Abeel

72. (1) Force, Am. Arch., 4th ser., 3:50 (Schuyler to Washington, 6 Aug 75). See also 4th ser., 2:1703 (same to Cong, 21 Jul 75). (2) French, First Year of the American Revolution, p. 184. (3) Scheer, Private Yankee Doodle, p.. 209.

73. RG 93, Pickering Letters, 85:207-15 (to Lincoln, 30 Nov 82).

74. (1) Fitzpatrick, Writings of Washington, 4:109 (GO, 22 Nov 75). For similar orders of a later date, see 21:73 -74 (GO, 9 Jan 8 1); 25:453 - 54 (GO, 20 Dec 82). (2) RG 93, Pickering Letters, 83:40-43 (to Brig Gen James Clinton, Col Elias Dayton, Assistant Deputy Quartermaster Forman, 26 Jan 82).

147

still later charged that many tents had been lost in the campaign of 1777 "owing to their lying wet in the wagons." With this loss in mind, he inquired of Greene at the end of the 1778 campaign whether orders ought not to be given to have all tents dried and sent to Morristown for repair if the troops were coming into New Jersey.75

Though tents-bell tents, horseman's tents, wall tents, common tents for soldiers, and marquees for officers-were essential items of supply in the field, their availability was dependent upon the importation of duck and canvas by private merchants or the Secret Committee. As in the case of other needed supplies, the Continental Congress sought unsuccessfully to promote domestic production of hemp, flax, and cotton, and it recommended that the various legislatures consider ways and means of introducing the manufacture of duck and sailcloth.76

Initially, and until the Secret Committee was able to procure textiles abroad, the Quartermaster's Department had to rely on whatever fabrics were available in the colonies. The Continental Congress in the summer of 1775 applied to the Committee of Philadelphia for whatever quantity of duck, Russia sheeting, tow cloth, osnaburg, and ticklenburg that could be procured in that City.77 Any suitable fabric was in demand, for it required 21 ½ square yards of duck to make a common tent for six men. In October 1776 "country linen fit for tents" was selling at three shillings and sixpence a square yard, but prices spiraled upward, reflecting demand, as the war continued.78

Textiles in the colonies were quickly depleted. When Congress on 30 August 1776 directed James Mease, then acting as its agent, to procure in Philadelphia any cloth fit for making tents, the only supply available was a parcel of light sailcloth in the hands of the Marine Committee. Congress thereupon directed that committee to deliver the sailcloth to Mease. At the same time, it directed the Secret Committee to write to the Continental agents in the eastern states to purchase all duck and other cloth fit for tents which they could procure in their respective states. The Marine Committee remonstrated, alleging that none of the Continental vessels could sail if the sailcloth was taken, but it was told that the soldiers would have tents even if "the Yards of those Continental Frigates and Cruizers that had sails made up" had to be stripped.79

75. (1) Jonathan Burton, Diary and Orderly Book of Sergeant Jonathan Burton, ed. Isaac W. Hammond (Concord, N.H., 1885), p. 11. (2) Force, Am. Arch., 5th ser., 3:1098 (Henry Schenk to pres, N.Y. Committee of Safety, 6 Dec 76). (3) APS, Greene Letters, 10:49 (Abeel to Greene, 9 Nov 78).

76. JCC, 4:224 (21 Mar 76).

77. Ibid., 2:190 (19 Jul 75). See also 3:258 (21 Sep 75); 4:102-03 (30 Jan 70).

78. Force, Am. Arch., 5th ser., 2:988 (Md. Council of Safety to Col Thomas Bond, 11 Oct 76).

79. (1) JCC, 5:718 - 19, 735 (30 Aug and 4 Sep 76). (2) Burnett, Letters. 2:109 (Robert Morris to Md. Council of Safety, I Oct 76).

148

By such means the troops were at least partially equipped with tents at the beginning of the war.80 The loss of tents at Fort Washington, New York, and in the evacuation of New York City, however, exacerbated the shortage. The British raid against Danbury, Connecticut, in April 1777 caused a loss of 1,700 tents, among other stores, and struck a hard blow at the preparations the Quartermaster's Department was making for the 1777 campaign. Late in May the Quartermaster General reported that preparations were complete except in regard to tents. When Washington studied Mifflin's account of the tents he had provided, Washington concluded that some regiments must have drawn more tents than their share.81 Subsequently, allowances were set forth in General Orders. An order published in September allowed one soldier's tent for the field officers of each regiment, one for every

four, commissioned officers, one for eight sergeants, drummers, and fife players, and one for every eight privates. In 1779, the Quartermaster General was authorized to issue to each regiment one marquee and one horseman's tent for the field officers; one horseman's tent for the officers of each company; one wall tent each for the adjutant, quartermaster, surgeon and mate, and paymaster; one common tent each for the sergeant major, the quartermaster sergeant, the fife and the noncommissioned officers of each company; and one common tent for every six privates, including drummers and fife players.82

The Quartermaster's Department continued to be hard pressed to supply tents. Fabric was at a premium. In the process of repairing tents during the winter, quartermasters had their artificers convert the fabric of tents that could not be made serviceable into wagon covers, forage bags, and knapsacks. Twine and cordage were also much in demand. Deputy Quartmmaster General Abeel, who served as the agent for camp equipage under Quartermaster General Greene, complained that the repair work of his tentmakers would come to a halt unless he was promptly supplied with twine.83

Inflated prices increased the difficulty of procuring new tents. So hampered was the Quartermaster General that he estimated the American troops would lack 1,500 tents if Washington's hopes for a cooperative effort with Admiral d'Estaing materialized in the fall of 1779. In consequence, Washington appealed to Massachusetts to furnish that number of tents. The firm of Otis and Henley, which had been procuring duck and manufacturing tents, for the department, extending credit for the purpose, was in dire need of

80. In September 1776 Washington complained that at least one third of his army lacked tents and that those the troops did have were worn and in bad condition. Force, Am. Arch., 5th ser., 2:257 (Tilghman to Moylan, 9 Sep 76).

81. (1) Fitzpatrick, Writings of Washington, 8:145 (to Mifflin, 31 May 75). (2) Washington Papers, 47:19, 116-17 (Mifflin to Washington, 19 and 27 May 77).

82. Fitzpatrick, Writings of Washington, 9:213 (GO, 13 Sep 77); 15:162-63 (GO, 27 May 79).

83. APS, Greene Letters, 8:3 (Abeel to Greene, 13 Feb 79); 5:30, 75 (same to same, 19 and 26 May 79).

149

cash to pay its creditors. Greene promised relief and urged the partners to continue procurement. So gloomy did the prospect of any procurement in the following year become that Greene proposed that tents be obtained by allocating the number wanted to the seaport towns of the New England states and appealing to designated merchants there to obtain the tents.84

A report from the Board of War in the fall of 1780 led Congress to order John Bradford, the Continental Agent at Boston, to deliver to the Quartermaster General all the duck in his hands suitable for tents. Pickering planned to order his deputy to receive the duck, have it made into tents, and deliver the tents to Springfield, Massachusetts.85 But Pickering got no duck, for Bradford said it was all needed by the Navy. Still searching for duck in 1781, Pickering again applied to the Board of War, and Congress ordered Bradford to deliver to the Quartermaster General all duck suitable for tents. Bradford rigidly construed the language of the resolution; the heavy duck he had, he argued, was not proper for tents. Pickering again appealed to the Board of War for help. Apparently the Continental Agent intended to sell the duck to raise money for the Navy, but the Quartermaster's Department had no funds to purchase it. "We leave it to the determination of Congress, whether the essential article of Tents is not of the most consequence to the public," the board reported to Congress late in May 1781. Bradford had on hand at least 1,000 pieces of duck, which at a conservative estimate would make more than 3,000 tents. These tents were essential for the coming campaign in view of the uncertainty about the number of tents that the states would supply. Congress thereupon ordered delivery of the duck to the Quartermaster General, instructing him to use the suitable pieces for tents and to exchange the remainder, except what was necessary for other purposes in the department (such as wagon covers and sails for craft on the Hudson), for light duck or other materials fit for tents.86

In early June Pickering submitted a return of tents that included repaired tents, new ones, and those then being manufactured. In addition to marquees, wall tents, and horseman's tents, there were some 2,000 common tents. Over 1,000 more were expected from the states, but Pickering admitted that too much dependence could not be placed on receiving these.87 Neither on the eve of the Yorktown campaign nor at any time during the war was the Quartermaster's Department able to provide an adequate supply of tents to Washington's army.

84. (1) Fitzpatrick, Writings of Washington, 16:426 (to Jeremiah Powell, 7 Oct 79). (2) APS, Greene Letters, 9:9 (Otis and Henley to Greene, 24 Nov 79). (3) RG 11, CC Papers, item 173, 4:259-61 (Greene to Otis and Henley, 13 Dec 79). (4) Washington Papers, 141:20 (Greene to Washington, 8 Jul 80).

85. (1) JCC, 18:962 (21. Oct 80). (2) RG 11, CC Papers, item 192, fol. 37 (Pickering to Pres of Cong, 30 Oct 80).

86. (1) RG 93, Pickering Letters, 123:161 - 63 (to Board of War, 22 Apr 81). (2) JCC, 20:452 53, 550-51 (27 Apr and 28 May 81).

87. Washington Papers, 176:32-37 (Pickering to David Humphreys, 5 Jun 81).

150

The many flimsy tents furnished the troops provided little shelter in the summer and practically none in the winter. Yet troops often lay in tents in December and sometimes as late as February. "We are still in Tents" on Christmas Day, Surgeon Albigence Waldo recorded, "when we ought to be in Huts." Private Martin recalled that when he arrived in New Jersey in mid December 1779, heading for Basking Ridge, he helped in clearing a site of snow, in pitching three or four tents that faced each other, and in building a fire in the center. "Sometimes we could procure an armful of buckwheat straw to lie upon, which we deemed a luxury."88

As soon as possible after arriving at a winter encampment site, the troops began to build huts. Early in the war no uniformity was imposed on hutting the troops. Much of the sickness among the troops at Valley Forge in the winter of 1777-78 was occasioned, according to Washington, by improper methods used in constructing huts, some of which were sunk in the ground and others covered with earth. To prevent a repetition of the consequences that had resulted from improper hutting, he directed, as the time approached for winter encampment the next year, that all officers were to make sure their men followed the instructions of the Quartermaster General in building their huts. He ordered that the huts were to be roofed with boards, slabs, or large shingles; that they were not to be covered with earth or turf and that the men were not to dig into the ground except to level the surface. Moreover, he directed that the men were to erect bunks to keep themselves off the ground and build proper stands to preserve their arms and accouterments from damage.89

The troops spent some six to eight weeks constructing log huts and continued to live under cover of canvas tents until February 1779, suffering extremely from exposure to cold and storms. The soldiers constructed the huts from the trunks of trees which they cut into various lengths, notching them at the ends so that they could be dovetailed at the four comers. The spaces between the logs were filled with a plastering consisting of mud and clay, and the roof was covered with hewn slabs. A chimney, centered on a wall, was then built of stone, if obtainable, or of smaller pieces of timber; both the outer and inner sides of a timber chimney were covered with clay plaster to protect the wood against the fire. The door and windows, which moved on wooden hinges, were formed by sawing openings into the log walls. James Thacher, a Continental Army surgeon, wrote that in this manner "our soldiers, without nails, and almost without tools, except the axe and saw, provided for their officers and for themselves comfortable and convenient quarters, with little or no expense to the public."90

88. (1) "Diary of Surgeon Albigence Waldo, of the Connecticut Line," Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 21 (1897): 312. (2) Sheer, Private Yankee Doodle, p, 166.

89. Fitzpatrick, Writings of Washington, 13:395 (GO, 14 Dec 78).

90. Thacher, A Military Journal During the American Revolutionary War, pp. 155-56.

151

RECONSTRUCTION OF SOLDIERS, HUT AT VALLEY FORCE STATE PARK

Generally, the soldiers cut the logs for their huts, but in the winter of 1779-80 the Quartermaster's Department made a great effort to provide boards for hutting the troops. As early as mid-September 1779, the Quartermaster General instructed Assistant Quartermaster General Cox and Deputy Quartermaster General Moore Furman at Trenton to procure 200,000 feet of boards. Shipment had to be delayed until the precise location of the camp was selected.91 But when Washington decided upon a position "back of Mr. Kembles," about three miles southwest of Morristown, the distance that the boards had to be brought and the fact that the troops arrived promptly led to the construction of another "log-house city." When Greene learned of the site, he wrote to some brigade commanders whose troops were already nearby that he hoped there would be sufficient wood in the area for "hutting and firing if it is used properly." The brigade quartermasters were to draw tools as well as a plan for hutting from the storekeeper at Deputy Quartermaster General Abeel's store in Morristown.92

Very strict attention was given to allocating ground to the brigades and to building the huts. Washington had instructed the Quartermaster General

91. (1) APS, Greene letters, 9:26 (Claiborne to Cox, 16 Sep 79). (2) RG 11, CC Papers, item 173, 2:75 - 76, 77 - 79;4:207 (Greene to Furman, 17 Sep, 11 Nov, and I Dec 79).

92. Ibid., item 173, 4:201 (Greene to St. Clair et al., 16 Dec 79).

152

to specify the precise dimensions of the huts to be erected, and he warned that any deviation would result in the hut's being pulled down. He thought the placement and form of the Pennsylvania huts at Raritan, New Jersey, the previous winter provided a good model.93 As built by the troops using the method of construction already described, the soldier's hut, which housed 12 men, was generally 12 feet wide and 15 to 16 feet long. The officer's hut had 2 chimneys, was divided into 2 apartments, and was occupied by 3 or 4 officers. Once the huts were completed, the last thing the troops did was "to hew stuff and build us up cabins or berths to sleep in, and then the buildings were fitted for the reception of gentleman soldiers, with all their rich and gay furniture.94

At subsequent winter encampments, Washington continued to insist that huts were to conform to the plan and dimensions set forth by the Quartermaster General. By 1782 he thought that "even some degree of elegance should be attended to in the construction of the hut." In Pickering's regulations for hutting in the last winter of the war, huts for both officers and soldiers were increased in size. Instead of one room, the soldier's hut now had two rooms, each about 18 by 16 feet and 7 feet in height.95

Quartermaster Artificers

Whether in constructing barracks at a post, building or repairing boats, or maintaining a wagon train in working order, the Continental Army needed artificers both in the field and at posts. When none were available, soldiers had to be detailed from the line. This frequent necessity distressed Washington, since the strength of the force he could put in the field was thereby diminished. Employing artificers at daily wages would have imposed a heavy financial burden; instead, the Continental Army initially resorted to raising companies of artificers. Such companies of skilled civilian workmen were raised by master artisans to perform specific tasks, such as the building of barracks or the construction of bateaux. The master artisan served as the foreman or superintendent of the company.

Mifflin's organization of the Quartermaster's Department in 1775 included civilian artificers, and at least some were organized into companies, headed by master artisans. When Maj. Gen. Charles Lee was sent to supervise the defenses at the southern tip of Manhattan Island early in 1776, he promptly suggested to the Provincial Congress of New York that it establish a corps of artificers. That body at once agreed to create a company of about sixty men, including officers (master artisans). The artificers were to have

93. Fitzpatrick, Writings of Washington, 17:137 (GO, 19 Nov 79).

94. Sheer, Private Yankee Doodle, p. 169

95. (1) Fitzpatrick, Writings of Washington, 25:303 (GO. 28 Oct 82). (2) RG 93, Pickering Letters, 84:254-57 (to Washington, 4 Nov 82): 85:243-44 (circular. 7 Nov 82).

153

the same pay-10 dollars a month-that the companies of artificers at Cambridge received.96

Early in 1776 the Northern Department required more artificers than the main Continental army, and initial procedures for raising companies of artificers were developed there. On 6 January General Schuyler entered into an agreement with a master artificer, Jacob Hilton of Albany, to go to Fort George, Ticonderoga, and other places with his men to build bateaux and other vessels as directed. This company of ship carpenters provided its own tools. The men were paid 8 shillings in New York currency a day, and Hilton received 10 shillings. Their wages began on the day they left Albany, but they forfeited them if they left their assigned post without authorization. Schuyler agreed to provide these artificers with a larger ration than was allowed to soldiers.97 It became customary throughout the war for the Commissary General to issue one and a half rations and one gill of rum per day to an artificer. Similar contracts for raising companies of artificers by master artificers were made later in the year.98 For the most part these early companies of civilian artificers appear to have been raised only to accomplish specific tasks before being discharged.

Quartermaster General Mifflin introduced a change in this procedure, though it was put into effect months after he had vacated his office. Under orders received earlier from Mifflin, Maj. Elisha Painter in May 1778 directed the enlistment for the duration of the war of a company of artificers consisting of carpenters and wheelwrights, who were to provide their own tools. Each artificer was paid 171/3 dollars per month and received in addition a 20-dollar bounty and a suit of clothes; he also was entitled to every other perquisite granted by Congress to battalion soldiers in the Continental Army. He was subject to all the rules and regulations of the Continental Army.99 Mifflin apparently had held out the hope that officers commanding this and subsequent companies-that is, the master artisans-would be commissioned in the Continental Army.

After Nathanael Greene became Quartermaster General, he appointed Col. Jeduthan Baldwin, on 29 July 1778, to the command and superintendency of all the artificers in the Quartermaster's Department belonging to the Continental Army. All officers-most of them were designated captains-commanding companies of artificers had to make returns to Colonel Baldwin of the number of men in their companies. A monthly return submitted by Baldwin on 1 December 1778 listed 18 company commanders. Of these, 11 reported the number of artificers in their companies. Thus, there

96. Force, Am. Arch., 4th ser., 5:260 (Lee to N.Y. Prov Cong, 14 Feb 76); 269 (15 Feb 76).

97. Ibid., 4th ser., 6:1074.

98, See ibid., 4th ser., 6:1071-72, 1074-75 (Schuyler to Gov Trumbull and to pres, Mass. Assembly, 25 Jun 76); 5th ser., 3:1249-50 (memorandum of agreement with artificers, Northern Army, 16 Dee 76).