|

|

|

GENERAL BRINK

|

GENERAL TRAPNELL

|

CHAPTER I

The Formative Years: 1950-1962

In 1950 the United States began to grant military aid to the French forces in -Indochina in an effort to avert a Communist takeover of Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam. From that time U.S. military assistance, adapted to the increasing Communist threat, developed in three phases: military advice and assistance; operational support of the South Vietnamese armed forces; and, finally, the introduction of U.S. combat forces. The U.S. armed forces in each of these phases were fulfilling their mission under the U.S. policy of ensuring the freedom of Indochina and specifically the freedom of South Vietnam.

The direction, control, and administration of U.S. Armed forces throughout this period of U.S. commitment initially was vested in a military assistance advisory group and, beginning in 1962, in the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam. Both headquarters had joint staffs with representatives from all the armed services. Since the U.S. Army had the largest share of the mission of advising, training, and supporting the South Vietnamese armed forces, U.S. Army representation on the joint staffs and in the field was proportionately greater than that of the other services. The U.S. Army also provided the commanders of the Military Assistance Advisory Group and the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam.

The U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, was a unified command, more specifically a subordinate unified command, under the Commander in Chief, Pacific. Precedents for such an arrangement are found in the command and control structures of World War II. Lessons from that experience played an important role in establishing the doctrine for unified commands that, with modifications, was applied to the Korean War and the Vietnam conflict.

Joint Doctrine for Unified Commands

A unified command is a joint force of two or more service components under a single commander, constituted and designated by

[3]

the joint Chiefs of Staff. Generally, a unified command will have a broad, continuing mission that requires execution by significant forces of two or more services under single strategic direction. This was the case in .South Vietnam.

The current doctrine for unified commands is based on the National Security Act of 1947, which authorized the establishment of unified commands in the U.S. Armed forces. In 1958 an amendment to the act authorized the President to establish unified commands to carry out broad and continuing operations. Developing doctrine concerning the organization and operations of U.S. unified commands is the responsibility of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The "JCS Unified Command Plan" and FCS Publication 2: United Action Armed Forces (UNAAF) provide the guidelines governing the responsibilities of commanders in unified (multiservice) and specified (single service) forces. These publications include doctrine for unified operations and training.

The three military departments, under their respective service secretaries, organize, train, and equip forces for assignment to unified and specified commands. It is also the responsibility of the departments to give administrative and logistical support to the forces assigned to the unified commands. One of the primary functions of the Department of the Army, for example, is to organize, train, and equip Army forces for the conduct of prompt and sustained combat operations on land in order to defeat enemy land forces and to seize, occupy, and defend land areas.

Effective application of military power requires closely integrated efforts by the individual services. It is essential, . therefore, that unity of effort is maintained throughout the organizational structures as well. This goal is achieved through two separate chains of command-operational and administrative. Operational control runs from the President to the Secretary of Defense to the joint Chiefs of Staff to the unified, commands. The administrative logistical chain of command runs from the President to the Secretary of Defense to the secretaries of the military departments and then to the service components of the unified commands.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff have defined the duties of unified and specified commanders who use the forces provided by the military departments. The Joint Chiefs establish policy concerning the command, organization, operations, intelligence, logistics, and administration of service forces and their training for joint operations. These guidelines also apply to sub-unified commands.

Army doctrine for unified commands is set forth in FM 100-15: Larger Units, Theater Army Corps (December 1968). In this docu-

[4]

ment, Army policy governing command in a theater of operations during wartime varies from that presented by the joint Chiefs. According to the joint Chiefs, the unified commander does not additionally serve as a commander of any service component or another subordinate command unless authorized by the establishing authority. Current Army doctrine states:

During peacetime the theater army commander normally commands all Army troops, activities, and installations assigned to the theater. [However] . . . during wartime, the theater commander normally withdraws from the theater army commander operational control of army combat forces, theater army air defense forces, combat support forces, and other specified units required to accomplish the theater operational mission. The theater commander, therefore, normally exercises operational command of most tactical ground forces during wartime . . . . Exceptionally, during wartime the theater commander may direct the theater army commander to retain operational control of US ground force operations. In this instance, the theater army commander provides strategic and tactical direction to field armies and other tactical forces.

Both doctrines, however, agree that the commander of a subordinate unified command set up by a unified command with approval of the Secretary of Defense has responsibilities, authorities, and functions similar to those of the commander of a unified command, established by the President.

Component and sub-unified commands are subordinate to the unified command in operational matters. In other words, the unified commander has operational command of these elements. The term "operational command" applies to the authority exercised by the commanders of unified commands. It is also used in other command situations such as combined commands. No commander is given more authority than he needs to accomplish his mission. The unified commander's instructions may be quite specific; the component commander, however, is usually given sufficient latitude to decide how best to use his forces to carry out the missions and tasks assigned to him by the unified commander. The sub-unified commander has the same authority as a unified commander over the elements in his command. The structure and organization of a sub-unified command are determined by the missions and tasks assigned to the commander, the volume and scope of the operations, and the forces available. With these factors in mind, the organization of a sub-unified command should be designed on the principles of centralized direction, decentralized execution, and common doctrine. Thus the integrity of the individual services is preserved.

[5]

The Beginning of U.S. Support to Vietnam

The U.S. command and control organization for directing and administering American military assistance for Vietnam was influenced by World War II and Korean precedents. The origins of American military assistance policies developed after World War II are found in the aggressive expansionist policies of the USSR and the need to strengthen the free nations of the world, whose security was vital to the United States. Out of the U.S. resolve to assist the Free World grew the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 1949 and the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) in 1954, established after France had lost in Indochina. Since U.S. Military assistance to Indochina in general and to Vietnam in particular was channeled through France during the first Indochina War (1946-1954), French influence was felt strongly in the early 1950s and also had its effect on the organization and operation of the U.S. Military Assistance Group in Indochina.

Military assistance after World War II was authorized on a regional, comprehensive scale by the Mutual Defense Assistance Act of 6 October 1949. Its chief objective was to strengthen the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, in which France was a key member. At the time, France was heavily engaged in the first Indochina War and U.S. Military assistance to Southeast Asia began to increase steadily. To supplement military assistance with economic aid, the U.S. Congress a year later sanctioned technical aid to underdeveloped nations by passing the Act for International Development, popularly known as the Point Four Program. In 1951 the two acts, along with other similar measures, were consolidated in the Mutual Security Act, which was revised again in 1953 and 1954 to meet the needs of the expanding Mutual Security program. An essential condition to be met before U.S. assistance could be given under this legislation was the conclusion of bilateral agreements between the United States and the recipient nation, which included the assurances that assistance would be reciprocal, that any equipment and information furnished would be secured, and especially that equipment would not be retransferred without U.S. consent.

Since it was the policy of the United States to support the peaceful and democratic evolution of nations toward self-government and independence, the State of Vietnam and the kingdoms of Laos and Cambodia could not receive U.S. Military assistance as long as they were ruled by France. Not until February 1950, after the French parliament had ratified agreements granting a

[6]

degree of autonomy to the Associated States of Indochina (Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia) within the French Union, could the U.S. government recognize these states and respond to French and Vietnamese requests for military and economic aid.

MAAG, Indochina: The Forerunner

On 8 May 1950 Secretary of State Dean G. Acheson concluded consultations with the French government in Paris and announced that the situation in Southeast Asia warranted both economic aid and military equipment for the Associated States of Indochina and for France. To supervise the flow of military. Assistance, Secretary of Defense George C. Marshall approved the establishment of a small military assistance advisory group. Total authorized strength at the time of its activation was 128 men. The first members of the group arrived in Saigon on 3 August 1950. After the necessary organizational tasks were completed, a provisional detachment Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG), Indochina-was organized on 17 September and assembled in the Saigon-Cholon area on 20 November 1950. The original structure, though temporary, provided for service representation by setting up Army, Navy, and Air Force sections within the group.

Military aid agreements between the United States and the governments of Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, and France were signed in Saigon on 23 December 1950. Known as the Penta-lateral Agreements, these accords formed the basis of U.S. economic and military support. U.S. Military assistance was administered by the newly constituted Military Assistance Advisory Group, Indochina. Its first chief was Brigadier General Francis G. Brink, who had assumed command on 10 October 1950. General Brink's main responsibility was to manage the U.S. Military assistance program for Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos and to provide logistical support for the French Union forces. Military training of Vietnamese units remained in the hands of the French Expeditionary Corps, and personnel of the U.S. advisory group had little, if any, influence and no authority in this matter. Because of this restriction, the chief function of the Military Assistance Advisory Group during the early years of U.S. Commitment in Indochina was to make sure that equipment supplied by the United States reached its prescribed destination and that it was properly maintained by French Union forces.

On 31 July 1952 General Brink was succeeded as chief of the advisory group by Major General Thomas J. H. Trapnell, who held this position for almost two years. The U.S. chain of command during 1950-1954 ran from the President, as Commander in Chief,

[7]

to the Department of the Navy (acting as executive agency), to the Commander in Chief, Pacific, and then to the chief of the Military Assistance Advisory Group in Indochina. Early in this period, the chiefs of the advisory groups dealt mainly with the Commander in Chief, Pacific, but when the war began to go badly for the French, higher authorities in Washington, including the President, took a more immediate interest. Increasingly, Washington became concerned about the effectiveness of U.S. Military aid to the French Union forces, the expansion of the Vietnamese National Army, and the conduct of the war.

To assess the value and effectiveness of U.S. Military aid and to try to exert influence in at least some proportion to the growing U.S. Commitment, Admiral Arthur W. Radford, Commander in Chief. Pacific, sent Lieutenant General John W. O'Daniel, Commanding General, U.S. Army, Pacific, on three trips to Indochina. General O'Daniel's visits were made after General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny had been replaced by General Raoul Salan on 1 April 1952, and after General Henri-Eugene Navarre had succeeded General Salan in May of the following year. General O'Daniel's efforts to observe the activities of the French command were only moderately successful. In no way was he able to influence either plans or operations.

General Navarre realized from the beginning that the French Union forces were overextended and tied to defensive positions. He therefore developed a -military plan, subsequently named after him,

[8]

that called for expanding the Vietnamese National Army and assigning it the defensive missions, thus releasing French forces for mobile operations. General Navarre also intended to form more light mobile battalions, and he expected reinforcements from France. With additional U.S. arms and equipment for his forces, Navarre planned to hold the Red River Delta and Cochinchina while building up his mobile reserves. By avoiding decisive battles during the dry season from October 1953 to April 1954, Navarre hoped to assemble his mobile strike forces for an offensive that by 1955 would result in a draw at least. The military plan had a pacification counterpart that would secure the areas under Viet Minh influence.

His plans were unsuccessful, however, despite increased U.S. shipments of arms and equipment. The French politely but firmly prevented American advisers and General O'Daniel from intervening in what they considered their own business. Following instructions from Paris to block the Communist advance into Laos, General Navarre in November 1953 decided to occupy and defend Dien Bien Phu. This fatal decision was based on grave miscalculations, and the Viet Minh overran Dien Bien Phu on 8 May 1954. Their tactical victory marked the end of effective French military operations in the first Indochina War, although fighting continued until 20 July, the date the Geneva Accords were signed.

The Geneva Accords of 20 July 1954 officially ended the fighting in Indochina. As a condition for its participation in the Geneva conference, the United States stipulated that an armistice agreement must at least preserve the southern half of Vietnam. This prerequisite was fulfilled by dividing Vietnam at the 17th parallel. The Geneva agreement also gave independence to Laos and Cambodia. Neither the United States nor the government of South Vietnam formally acknowledged the Geneva Accords, but in a separate, unilateral declaration the United States agreed to adhere to the terms of the agreements.

Some of the provisions contained in articles of the Geneva agreements were to have unforeseen and lasting effects on the organization and application of U.S. Military assistance and on the developing command and control arrangements of the U.S. Military Assistance Advisory Group. Among these provisions was Article 16, which prohibited the introduction into Vietnam of troops and other military personnel that had not been in the country at the time of the cease-fire. The provision also fixed the number of advisers in the military assistance group at 888, the total number of

[9]

French and Americans in the country on the armistice date. Of the total, the French representation consisted of 262 advisers with the military assistance group and 284 with the Vietnamese Navy and Air Force. Of the 342 Americans only 128 were advisers, as originally authorized before the cease-fire. The remaining spaces were filled on an emergency basis, temporarily with fifteen officers, newly assigned,- and almost two hundred Air Force technicians. These technicians were in Vietnam because they had accompanied forty aircraft given to the French early in 1954. Even though the U.S. Advisory role in Vietnam was about to change drastically, the magic figure of 342 was on the board and would be difficult to alter.

Articles 1719 contained restrictions regarding weapons, equipment, ammunition, bases, and military alliances. Shipment of new types of arms, ammunition, and materiel was forbidden. Only on a piece-by-piece basis could worn-out or defective items be replaced, and then only through designated control points. Neither North nor South Vietnam was to establish new military bases, nor could any foreign power exercise control over a military base in Vietnam. Furthermore, neither the North nor the South was to enter into any military alliance or allow itself to be used as an instrument for the resumption of hostilities.

To ensure compliance with these and other provisions of the Geneva agreements, International Control Commissions were set up for Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. Each commission consisted of representatives from India, Canada, and Poland, their staffs, and inspection teams. The strength of the International Control Commission in Vietnam-about 670 members-indicated its very considerable inspection and control capability. Because of the terms of the Geneva agreements, the commission's operations tended to favor North Vietnam, while restricting the functions of the Military Assistance Advisory Group and increasing its work load. The U.S. objective of creating a national army and achieving an effective military status for South Vietnam thus was severely handicapped. On the other hand, however, as late as 1959, the International Control Commission was praised by the chief of the U.S. Advisory group in 1959 as benefiting South Vietnam and operating as a possible deterrent to Viet Cong attack. South Vietnam thus gained valuable time, which allowed for political consolidation, economic development, and progress toward the establishment of a balanced military force.

The agony of Dien Bien Phu and the rapidly declining fortunes of the French forces fighting in Vietnam placed Washington in a

[10]

GENERAL O'DANIEL

dilemma.. The French request for U.S. Armed intervention sharply divided President Dwight D. Eisenhower's advisers. The President decided that U.S. intervention could become a reality only if undertaken with the help of U.S. allies, with the approval of the Congress, and with independence for the Associated States of Indochina. None of these prerequisites was met. During the deliberations on the U.S. course of action, the President consulted with General O'Daniel and subsequently persuaded him to postpone his retirement and accept the assignment as chief of the Military Assistance Advisory Group in Indochina. In deference to French sensibilities and to ensure the seniority of the French Commander in Chief in Indochina, O'Daniel relinquished his third star and reverted to the rank of major general.

On 12 April 1954 General O'Daniel replaced General Trapnell and became the third U.S. Army officer to head the advisory group. He brought with him another expert on Indochina, Lieutenant Colonel William B. Rosson. Within two months General O'Daniel obtained French agreement on U.S. participation in training the Vietnamese armed forces. French collaboration with U.S. elements was prodded by the French defeats on the battlefield and the replacement of General Navarre by General Paul Ely. General Ely as High Commissioner for Vietnam and Commander in Chief, French Expeditionary Corps, combined the civil and military authority still exercised by France.

The understanding on U.S. training assistance the Ely-O'Daniel agreement-had been reached informally on 15 June 1954. It was 3 December, however, before diplomatic clearance allowed the formation of a nucleus of the Franco-American Mission to the Armed Forces of Vietnam. President Eisenhower's special envoy to Saigon, General J. Lawton Collins, concluded a formal agreement with General Ely on 13 December. This agreement provided for the autonomy of the Armed Forces of the State of Vietnam by 1 July 1955 and gave the chief of the U.S. Advisory group in Indochina the authority to assist the government of Viet-

[11]

nam in organizing and training its armed forces, beginning 1 January 1955. The agreement also ensured over-all French control of military operations in Indochina.

The Ely-Collins agreement fundamentally changed the U.S. Assistance role in Indochina from one of materiel supply and delivery to a true military assistance and advisory role in support of Vietnamese government. With this step, the United States for the first time became fully involved in the future of South Vietnam. The new situation called for a basic reorganization of the advisory group to meet its enlarged responsibilities. In close collaboration with the French, General O'Daniel organized the Training Relations and Instruction Mission (TRIM) on 1 February 1955. The U.S. Military Assistance Advisory Group, in a combined effort with the South Vietnamese and the French, was operating on three levels. Policy was established on the highest level by a committee consisting of the Vietnamese Minister of Defense, a senior French general, and the chief of the U.S. Advisory group; a co-ordinating committee on the Defense Ministry level was composed of the same French and U.S. representatives and the Chief of Staff of the Vietnamese armed forces; and, in the field, heads of training teams were attached to Vietnamese units.

These combined arrangements for training the Vietnamese Army continued for fourteen months until the French High Command in Indochina was deactivated on 28 April 1956. On the following day, personnel from the Training Relations and Instruction Mission were reassigned to MAAG's Combat Arms Training and Organization Division. For another year, the French continued to provide advisers to the Vietnamese Navy and Air Force. During its existence, the training mission had 217 spaces for U.S. Military personnel, almost two-thirds of the 342 spaces authorized for the entire advisory group. The proportionately high commitment to training activities was undertaken even though it reduced MAAG's ability to deal adequately with growing logistical problems. From the beginning of its operations, most difficulties encountered by the advisory group could be attributed to the shortage of personnel, which in turn stemmed from the ceiling imposed by the Geneva agreements.

In the meantime, the United States decided to decentralize MAAG operations, thus dividing command and administrative burdens and strengthening the U.S. Advisory efforts in Indochina. A reorganization of the Military Assistance Advisory Group was also needed to adjust to significant political developments in the area. On 16 May 1955 the United States and Cambodia signed an agreement for direct military aid-a move followed on 25 Septem-

[12]

ber by Cambodia's declaring itself a free and independent state. On 20 July, Vietnam announced that it would not participate in talks for the reunification of North and South Vietnam through the elections that were scheduled for the following year, according to the Geneva agreements. On 26 October Premier Ngo Dinh Diem proclaimed the Republic of Vietnam, after deposing former Emperor and Head of State Bao Dai through a national referendum. Diem also became the supreme commander of South Vietnam's armed forces. Meanwhile, in Laos, a coalition government was being negotiated that would include the Communist Pathet Lao group. (An accord was finally reached on 5 August 1956.) In the midst of these events, the last French High Commissioner left Saigon on 16 August 1955. Because of these developments, a reorganization of U.S. Military assistance to the newly independent states of Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos was needed. Consequently, on 13 June 1955 the Military Assistance Advisory Group, Cambodia, was organized in Phnom Penh. Assistance operations in Cambodia and Laos had differed significantly from those in South Vietnam, because activities in Cambodia and Laos had been limited to logistical support. Therefore, the mission of the newly formed advisory group in Cambodia was primarily logistical, in contrast to the mission of the one in Saigon, which included advisory and training duties. Until 1 November 1955, when the Military Assistance Advisory Group, Indochina, was redesignated the Military Assistance Advisory Group, Vietnam, General O'Daniel retained the responsibility for the U.S. Navy and Air Force efforts in Cambodia. To comply with the Geneva agreements, U.S. Military assistance and advisory activities in Laos were less conspicuous than in the rest of Indochina. In December 1955 the United States established a Programs Evaluation Office in Vietnam, which was in charge of military assistance. The Programs Evaluation Office operated under the Operations Mission of the U.S. Embassy. An overlap of functions existed in assisting the Royal Lao Air Force. The Air Force section of the Military Assistance Advisory Group, Vietnam, continued to control all military aviation matters in and for Laos. Thus by the end of 1955, the advisory group in Vietnam was no longer responsible for military assistance programming and maintenance inspection for Laos and Cambodia. The final separation of MAAG duties for Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia was accomplished by 26 October 1956.

In spite of its reduced responsibilities, the Military Assistance Advisory Group, Vietnam, was still too busy to carry out all its remaining duties effectively. While the combined training, including good relations and co-operation with French personnel,

[13]

GENERAL WILLIAMS

was proceeding satisfactorily, a bottleneck developed in the area of logistics. Logistic problems had started with the withdrawal of the French Expeditionary Corps. Until the pullout, the French had not allowed the Vietnamese to handle logistics. But with the rapid reduction of their forces, the French handed over logistical responsibilities to the Vietnamese Army at a rate far exceeding the army's ability to assume such. duties. The Vietnamese had no personnel trained in logistical operations because the French had not provided the special training.

The Military Assistance Advisory Group, Vietnam, meanwhile had other problems, caused by the difficulty in finding, recovering, relocating, and shipping out excess equipment of the Mutual Defense Assistance Program. Not only did General O'Daniel have to struggle with a logistical nightmare, but he was also hard pressed for personnel in his training mission, because the French were reducing their contingent of advisers. By 18 November 1955, the day General O'Daniel left Vietnam, the French contingent in the training mission had decreased to fifty-eight men.

Lieutenant General Samuel T. Williams was General O'Daniel's successor. One of General Williams' first tasks was to obtain additional personnel to compensate for the reduction of the French element and to handle his mounting logistical requirements. General Williams' plea for more men was supported by the Commander in Chief, Pacific, but Washington was harder to convince. Interpreting Article 16 of the Geneva Accords narrowly, Washington authorities were reluctant to make a move toward any conspicuous increase in the strength of military personnel in South Vietnam. In talks with members of the International Control Commission and the government of South Vietnam, General Williams had ascertained that a one-for-one substitution of U.S. advisers for the departing French would not be considered a violation of the Geneva Accords.

After long and careful deliberation, officials in Washington skirted the issue by maintaining the authorized strength of the Military Assistance Advisory Group, Vietnam, at 342 men. On the

[14]

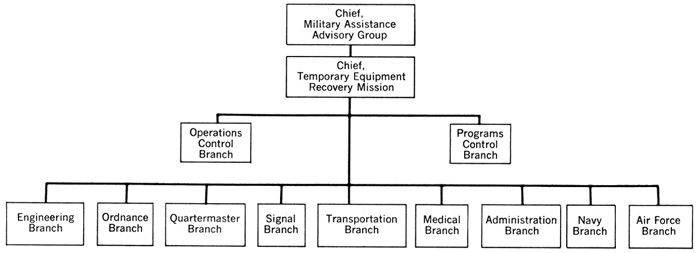

other hand, to help General Williams solve his logistical problems, the Temporary Equipment Recovery Mission (TERM) was established on 1 June 1956 with a strength of 350 men. Its primary task was to locate, catalog, ship out, and rebuild excess U.S. Military equipment. In addition, the recovery mission was to assist the Vietnamese in training their armed forces, with a view to establishing their own workable logistical support system. Although the activity was subordinate to the MAAG chief in Vietnam, it was not a part of the Military Assistance Advisory Group. (Chart 1)

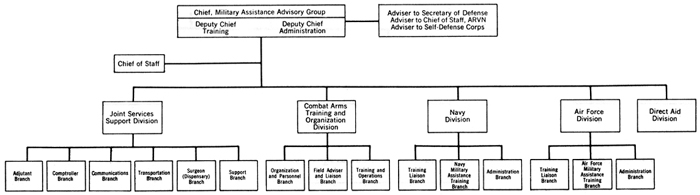

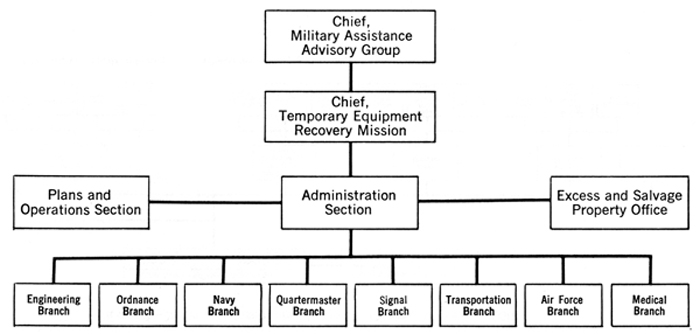

For the next four years, General Williams tried to have the strength of the advisory group raised to 888, the total number of U.S. and French advisers in Vietnam at the time of the armistice. Since the work load of the Temporary Equipment Recovery Mission was decreasing, the logical step was to integrate TERM personnel into the Military Assistance Advisory Group, Vietnam. General Williams believed that raising the strength of the advisory group by merging the two activities would not violate the intent or letter of the Geneva Accords. In April 1960 he reported that the International Control Commission had favorably considered the request to increase MAAG's strength from 342 to 685 spaces, 7 spaces less than the combined totals of the two activities but still over 200 men short of the July 1954 figure. On 5 May 1960 the U.S. Government announced that, at the request of the government of South Vietnam, the proposed increase would be authorized. During the following months TERM personnel were integrated into the Military Assistance Advisory Group, Vietnam, which was itself reorganized. (Charts 2 and 3)

After the armistice in the summer of 1954 the United States was chiefly concerned with the possibility of overt aggression from North Vietnam. To meet this potential external threat to the developing state of South Vietnam, the United States had formed the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) and had placed South Vietnam under its protection. Sine South Vietnam was prohibited from joining any alliance, SEATO's protective shield represented a strong deterrent to the proclaimed intentions of the North Vietnamese to unify all of Vietnam under Communist rule. This security was especially vital to South Vietnam, because it was just beginning to consolidate and establish the authority of the central government in Saigon.

An essential element in making the consolidation process work was the South Vietnamese Army. The army was no more than a

[15]

CHART 1-TEMPORARY EQUIPMENT RECOVERY MISSION, 1956

Source: Letter, HQ MAAG, Vietnam, dated 18 August 1956, subject: Brief Summary of Past Significant Events.

[16]

CHART 2-MILITARY ASSISTANCE ADVISORY GROUP, VIETNAM, 1956

Source: Letter, HQ MAAG, Vietnam, dated 18 August 1956, subject: Brief Summary of Past Significant Events.

[17]

CHART 3-TEMPORARY EQUIPMENT RECOVERY MISSION, 1960

Source: Study on Army Aspects of the Military Assistance Program in Vietnam (Ft. Leavenworth: HQ, USACGSC, 10 January 1980), p. D-6-1.

[18]

concept when the first Indochina War ended. The mission of the Military Assistance Advisory Group was to make this concept a reality. The South Vietnamese government depended on the army to provide a pool of administrators in the capital, the provinces, and the districts; to establish internal security; and to defend the country against outside aggression.

The obstacles in the way of achieving a central authority were towering. The army was rife with dissension, disloyalty, and corruption. Religious sects, such as the Hoa Hao and Cao Dai, and a gangster organization, the Binh Xuyen, had their own armed forces and were using them in a power struggle. In the Central Highlands, the Montagnards, ethnic tribal groups, refused to acknowledge the central government. In addition, some one million Catholic refugees from North Vietnam were being relocated in the south, upsetting a delicate religious balance. The progress of the Diem government toward stability must therefore be measured against this chaotic background.

By 1957 what few had expected to see in South Vietnam-political stability-had been accomplished. The economy was on a sound basis and improving. The armed forces had defeated the dissidents. The achievement obliterated Communist expectations of a take-over more or less by default. Diem's refusal to allow a referendum in 1956 apparently had deprived the North Vietnamese of a legal means by which to gain control of the south.

In 1957 the Communist North Vietnamese Lao Dong Party therefore decided on a change of strategy for winning its objective. The strategy was not new; it was a revival of the Viet Minh insurrection against French domination, and the tactics were those of guerrilla warfare, terror, sabotage, kidnapping, and assassination. The goal was to paralyze the Diem administration by eliminating government officials and severing contact between the countryside and Saigon. At the same time, the Communists would usurp government control, either openly or surreptitiously, depending on the local situation. The new insurgents became known as the Viet Cong, and their political arm was the National Liberation Front, proclaimed in December 1960.

The first, faint signs of a change in Communist strategy, from the plan to take over South Vietnam through political means supported by external pressure to a policy of subversion and insurgency within the country, began to be noticed in 1957. The following year, the Viet Cong intensified and extended their political and guerrilla operations to a point where they created serious problems that threatened South Vietnamese government control in the countryside. Prodded by General Williams and faced with an election,

[19]

President Diem belatedly ordered countermeasures in 1959 and committed more forces to internal security. But after the elections, in the fall of 1959, the Viet Cong began to gain the upper hand. Government control was eroding, the countryside and the cities were being isolated from one another, and the economy was suffering.

The crisis called for a re-evaluation of the U.S. effort. In March 1960 General Lyman L. Lemnitzer, U.S. Army Chief of Staff, visited South Vietnam. He reported to the joint Chiefs of Staff that the situation had deteriorated markedly during the past months. President Diem had declared the country to be in a state of all-out war against the Viet Cong and requested increased U.S. Assistance in materiel and training. General Lemnitzer supported the request and recommended that the training and organization of the Vietnamese Army should be modified to shift the emphasis from conventional to antiguerrilla warfare training. He offered U.S. Army personnel, in the form of mobile training teams, to help achieve this objective. In April the Commander in Chief, Pacific, recommended that a co-ordinated plan be developed for the over-all U.S. Effort in support of the government of South Vietnam. The Departments of State and Defense sanctioned this recommendation.

In Saigon the U.S. Ambassador, the chief of the advisory group, and other senior officials, constituting what was known as the Country Team, drew up a planning document that dealt with the political, military, economic, and psychological requirements for fighting the Communist insurgency. This Counterinsurgency Plan for South Vietnam contained significant reforms, many of which had been proposed to the government of South Vietnam for some time but had not been accepted. Among the prominent features of the Counterinsurgency Plan were the reorganization of the South Vietnamese command and control organization; an increase in Vietnam's armed forces from 150,000 to 170,000 men; and additional funds of about $49 million to support the plan. The Counterinsurgency Plan urged the Vietnamese to streamline their command structure to allow for central direction, to eliminate overlapping functions, and to pool military, paramilitary, and civilian resources.

The Military Assistance Advisory Group was also eager to provide more advisers at lower levels of command. At the beginning of the U.S. Training effort, advisers had been limited to higher commands down to the division level, and to schools, training centers, territorial headquarters, and logistic installations. Only on a very small scale and on a temporary basis had U.S. Advisers been attached to battalion-size units. The new emphasis on counter-

[20]

GENERAL MCGARR. (Photograph taken before his promotion to lieutenant general.)

insurgency training early in 1960 changed this situation. In May 1960, coinciding with the integration of TERM personnel into the advisory group, the MAAG chief was authorized to increase the number of personnel assignments to field advisory duties at battalion levels. These assignments remained temporary, however, and were still made selectively-mainly to armored, artillery, and marine battalions. Toward the end of 1960, the government of Vietnam transferred the paramilitary forces of its Civil Guard and Self Defense Corps from the Interior Ministry to the Ministry of Defense. Both organizations, vital to the maintenance of security in the provinces and districts, thus became eligible for MAAG training and assistance. In addition, U.S. Special Forces teams began training the newly established, 5,000-man, Vietnamese Ranger force by the end of 1960. Clearly, the U.S. Commitment in Vietnam was growing. At this time, General Williams ended his almost five-year tour as MAAG chief. He was succeeded by Lieutenant General Lionel C. McGarr on 1 September 1960.

In Washington the Eisenhower administration was replaced by the Kennedy administration. Among President John F. Kennedy's first concerns was the situation in Vietnam. At this crucial time, the Country Team's proposals for countering the Viet Cong insurgency arrived in Washington. Subsequently, the President decided to continue U.S. support for South Vietnam and increased both funds and personnel in support of the Diem government. On 3 April 1961 the United States and South Vietnam signed the Treaty of Amity and Economic Relations in Saigon. One week later President Diem won re-election in his country by an overwhelming majority. To strengthen U.S.-Vietnamese ties further, President Kennedy sent Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson to Saigon on 11 May. In a joint communiqué issued two days later, the United States announced it would grant additional U.S. Military and economic aid to South Vietnam in its fight against Communist forces.

These measures, taken by President Kennedy, were based on

[21]

preliminary surveys and consultations and on the recommendations of a temporary organization set up to deal with the crisis. In January 1961 the Secretary of Defense, Thomas S. Gates, Jr., had dispatched Major General Edward G. Lansdale to Vietnam. On the general's return, the Deputy Secretary of Defense, Roswell L. Gilpatric, was put in charge of an interdepartmental task force, subsequently known as Task Force, Vietnam, which identified and defined the actions the new administration was about to undertake. In Saigon a counterpart task force was established, its members taken from the Country Team. In addition, General McGarr, the MAAG chief, was brought to Washington in April to give his advice.

Washington had also accepted significant points of the Country Team's Counterinsurgency Plan, including support by the Military Assistance Program for a 20,000-man increase in the Vietnamese armed forces, for a 68,000-man Civil Guard and a 40,000-man Self Defense Corps, and for more U.S. Advisers for these additional forces. In May President Kennedy appointed Frederick C. Nolting, Jr., as Ambassador to South Vietnam, replacing Elbridge Durbrow. An economic survey mission, headed by Dr. Eugene Staley of the Stanford Research Institute, visited Vietnam during June and July and submitted its findings to President Kennedy on 29 July 1961. Later, in an address to the Vietnamese National Assembly in October 1961, President Diem referred to Dr. Staley's report, emphasizing the inseparable impact of military and economic assistance on internal security.

Soon after the return of the Staley mission, President Kennedy announced at a press conference on 11 October 1961 that General Maxwell D. Taylor would visit Vietnam to investigate the military situation and would report back to him personally. Dr. Walt W. Rostow, Chairman of the Policy Planning Council, Department of State, accompanied General Taylor. Upon its return, the Taylor Rostow mission recommended a substantial increase in the U.S. Advisory effort; U.S. Combat support (mainly tactical airlift); further expansion of the Vietnamese armed forces; and support for the strategic hamlet program, an early attempt at Vietnamization.

Subsequently, the military effort was directed primarily at carrying out these proposals. The task was more than the MAAG headquarters in Vietnam could handle. In November 1961 therefore President Kennedy decided to upgrade the U.S. Command by forming the U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), and selected General Paul D. Harkins as commander. General Harkins had been serving as Deputy Commanding General, U.S. Army, Pacific, and had been actively involved in the Pacific Com-

[22]

MAIN ENTRANCE TO MAAG HEADQUARTERS LOCATED ON TRAN HUNG DAO BOULEVARD, 1962.

mand's contingency planning for Vietnam. Following an interview with President Kennedy in early 1962, he went to Saigon and established Headquarters, Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, on 8 February 1962.

From 7 November 1950 through 7 February 1962 a single headquarters provided command and control for the U.S. Military effort in Vietnam. The number of authorized spaces increased from the original 128 in 1950 to 2,394 by early 1962.

The responsibility for directing and controlling military assistance programs lay with both the legislative and executive branches of the U.S. Government The Mutual Defense Assistance Act of 1949 provided the basis for these programs in Vietnam. Within the executive branch, major assistance duties were performed by the Office of the President, the Department of Defense, and the Department of State. Policies and objectives of military assistance to Vietnam from 1950 to 1962 were based on decisions made by three different administration.

[23]

In the Department of Defense the joint Chiefs of Staff' determined the military objectives. The Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs coordinated the broad political and military guidelines established by the White House and the Departments of State and Defense. The Commander in Chief, Pacific, provided specific guidance and direction to Headquarters, Military Assistance Advisory Group, Vietnam.

As the President's personal representative, the U.S. Ambassador to South Vietnam was charged with over-all responsibility for the co-ordination and supervision of U.S. activities in Vietnam. On political and economic matters, he was guided by the Department of State. The chief of the Military Assistance Advisory Group in Vietnam was responsible to the ambassador for military matters under the Mutual Security Program and, as senior military adviser, was a member of the Country Team.

[24]

|

Last updated 8 December 2003

|