CHAPTER III

The Buildup Years, 1965-1967

The situation at the beginning of 1965 was critical. By taking advantage of the civil unrest and political instability that had prevailed since mid-1963, the enemy had grown stronger and tightened his hold on the countryside. Estimates of enemy strength had risen from a total of 30,000 in November 1963 to 212,000 by July 1965. The Viet Cong launched their first division-size attack against the village of Binh Gia close to Saigon where they destroyed two South Vietnam Army battalions and remained on the battlefield for four days instead of following their usual hit-and-run tactics. North Vietnamese units and reinforcements had now joined the battle and were arriving at a rate of nearly 1,000 men per month. Both the North Vietnam Army and the Viet Cong were now armed with modern weapons such as the AK47 assault rifle, giving them a firepower advantage over the South Vietnam Army which was still fighting with American weapons of World War II vintage. Enemy strategy was evidently based on the assumption that the United States would not increase its involvement and that, weak as it was, the government of South Vietnam would collapse from its own weight if pushed hard enough.

After the death of President Diem in November 1963, South Vietnam had been controlled by a number of coalition governments. Each proved incapable of providing centralized direction to the war effort, and the pacification program ground to a halt. The majority of rural areas still remained under Viet Cong control or were "contested" in the enemy's favor. The involvement of military officials in the political upheaval, the consequent widespread reassignment and adjustments within the military command and staff structure, and the setbacks in offensive operations, all brought armed forces morale and effectiveness to a new low. The internal turmoil and collapse of the government also severely hampered mobilization and recruiting efforts. Almost all combat units were below authorized strength and desertion rates continued to soar. Some paramilitary units simply disbanded and melted away; the better South Vietnam Army units were spending most of their energies reacting to enemy initiatives. It was apparent

[47]

that the South Vietnam government could not prevent the enemy from taking over the country.

Consideration of and planning for the introduction of U.S. combat forces into South Vietnam began in late 1964. These forces were to be used primarily to defend and secure U.S. installations and activities. Further planning received impetus on 7 February 1965, when the Viet Cong attacked the MACV Advisor Compound and the Camp Holloway airfield at Pleiku. American forces suffered 136 casualties and twenty-two aircraft were damaged or destroyed. Three days later, Viet Cong terrorists destroyed the enlisted billets in Qui Nhon causing forty-four more American losses. These events demanded a strong response.

Obviously the war was entering a new phase for the United States. In spite of its ever-increasing aid and buildup of advisory and operational support personnel, it had not been able to reverse the deteriorating military situation. Only new and decisive action on its part could prevent the collapse of the government of South Vietnam.

Military Assistance Command Advisory Expansion

In early 1965 the United States met the challenge with the decision to introduce U.S. combat forces into South Vietnam. The arrival of U.S. Marine units at Da Nang in March 1965 was followed by a massive buildup of U.S. forces over the next three years. A peak strength of more than 543,000 was reached in May 1969. While U.S. combat forces undoubtedly prevented the military defeat of the South Vietnam government, American assumption of the major combat role has been the subject of much controversy. Critics have charged that the United States took the war away from the Vietnamese and made participation in the struggle meaningless for them. "Why fight when the Americans will fight our battles for us?" many argued. Americans have been accused of letting impatience blur their long-range vision for developing the Vietnamese military forces and of being too prone to do the job themselves. But, again, the claim must be taken into account that without U.S. combat intervention, the South Vietnam armed forces would have ceased to exist.

General Westmoreland divided the U.S. effort in South Vietnam into two parts: first, the tactical effort to destroy the Viet Cong and North Vietnam Army main force units and, second, the effort to help South Vietnam develop a viable government able to exercise effective control throughout the country. The two aims were closely related, with the second calling for a greater emphasis

[48]

in establishing security in the villages and hamlets, and in the extension of South Vietnam government influence and control. To help accomplish the second objective, sector (province) and subsector (district) advisory teams working with South Vietnam government officials at province and district level had to be strengthened and expanded, and their efforts focused on specific programs and goals.

Concurrent with U.S. combat force buildup, the advisory effort expanded at a rapid pace. Planning for the extension of the advisory program to the subsector level was under U.S. and Vietnamese consideration in late 1963 and early 1964. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, envisaged that advisory teams would deal primarily with the paramilitary forces (police and pacification cadre) and would supervise most of the unit training, advise the district chief on operations, and assist in operational planning. Experimental teams were planned for deployment in the spring of 1964; if these teams were successful the program was to be expanded later in the year. Planners raised a number of possible objections: some felt that the limited South Vietnamese staff at district level would be overwhelmed by advice and advisers; that Communist propaganda portraying the South Vietnam government as a U.S. puppet would be more effective than American claims, and that the U.S. military-civilian balance in personnel providing pacification advice at the provincial level would be disrupted. In addition, more American personnel in isolated areas would mean greater casualties. Nevertheless, the commander stuck to his decision.

The pilot teams, each consisting of one officer and one noncommissioned officer, began operating in April and May 1964. One team was deployed to each of the thirteen districts in the provinces surrounding Saigon. At first progress was minimal. There was no standard district organization and little similarity between districts. The government of Vietnam was in the process of building up its district staffs and was experiencing its own growing pains. Trained talent was at a premium. For the most part district chiefs were left to develop their own organizations with what limited manpower and talent they could obtain.

Within a month encouraging signs began to emerge. Districts which had been isolated and remote slowly became close members of the provincial family. As communications improved, some districts became active in provincial affairs. Economic and social bonds were made, and military co-ordination was greatly improved. Later, as the teams became firmly established, other advantages began to emerge. Support of all types became available to the

[49]

district chief who thereby acquired more prestige; at the same time, the U.S. obtained fresh insights into local conditions, activities, requirements, attitudes, and aspirations of the people. The pilot teams did become involved in the U.S. Operations Mission and the U.S. Information Service areas of interest, but without the disruption that had been feared earlier. Advice and assistance was furnished in planning and executing educational, economic, agricultural, youth, and information programs. In fact, the advisory teams in some areas devoted up to 80 percent of their energy to nonmilitary matters. However, usually the amount of time spent was equally divided between military and civil activities.

Basing his action on the gratifying results of the pilot teams, the Secretary of Defense approved plans to expand the program at a conference in Hawaii in June 1964. Planning and preparation for an additional one hundred teams began immediately. Each team would consist of two officers and three enlisted personnel. The title of subsector advisory team was derived from the district's military designation subsector. Prospective team locations were determined from recommendations submitted by senior advisers in each corps area. Terms of reference were developed based on lessons learned by the pilot teams; the teams were instructed to extend the capabilities of the Operations Mission and the Information Service, but only if directed by their local representatives. To better prepare incoming advisory personnel, a two-week Military Assistance Training Advisor course was established in Saigon

By 1965 the planning and preparations had paid dividends, and the deployment of the additional teams was practically complete. Most of the advantages claimed by the pilot teams were verified and many of those who had voiced strong opinion against the program were won over. The new teams met and overcame the same basic problems that the original thirteen had encountered. They enthusiastically assumed broad and unfamiliar responsibilities with very little specific guidance. Guidance was purposely general and, as was made abundantly clear, variety was the only consistency at subsector level. As the sole U.S. representation below provincial level, the team was the sole executor of the U.S. Effort in the South Vietnamese countryside.

By the end of the year many new districts were under consideration for assignment of advisory teams, and with some locations slated to receive U.S. Army Special Forces A detachments. Under study were ways to determine the best means of augmenting team capabilities (operations, training, security, and so forth) and of supporting teams with certain hard skills (intelligence, engineer

[50]

medical, and other skills). Missions and duties were also under revision to better suit the changing situation.

Also by the end of the year, 169 subsector advisory teams had deployed (133 MACV and 36 Special Forces men), with a total strength of about 1,100. Advisory teams were also assigned to all forty-three sectors (38 MACV and 5 Special Forces men). Over-all field advisory strength rose from 4,741 to 5,377 in 1965. It should be noted that these individuals were almost all experienced officers and noncommissioned officers, and thus represented a commitment not reflected in the bare statistical data.

The program continued to expand over the next several years. Although the results achieved were encouraging, continued evaluation and improvements were made. During the same period, the U.S. combat buildup generated an urgent demand for resources, talent, and command attention. Planners had to take care to ensure that the advisory teams were not slighted. The program, although relatively small, had proved to have a widespread and important influence on the war, with the effectiveness of the program depending on quality rather than quantity. A major study was initiated in June 1966 to evaluate and determine ways to improve the effectiveness of the sector and subsector advisory teams. In assessing the program planners analyzed the team composition, team-member training, and the command emphasis necessary to improve the program. The following recommendations of the study were approved by General Westmoreland on 1 July.

1. The greatest degree of tailoring of the subsector team organization to fit conditions should be encouraged, and the composition of all subsector teams should be evaluated in light of additional skills available; the composition should be altered where necessary to suit the situation of each district (psychological operations advisers, civil affairs advisers, engineer advisers, and so forth).

2. Special attention should be directed to the selection and preparatory training of officers designated as subsector advisers, including a twelve-week language course and a six-week civil affairs adviser course. Military Assistance Command recommended that preparatory training courses for subsector advisers be consolidated at one location in continental United States to relieve the necessity for extended temporary duty before the assignment of future advisers to South Vietnam.

3. Command emphasis is needed to make the advisory effort a priority program and ensure that officers assigned as subsector advisers not be used to fill other spaces in the command, and that

[51]

officers serving as subsector advisers serve their full tour in that capacity.

4. Exact requirements for helicopter support throughout the country for sector and subsector advisers should be determined, and, a special priority allocation of helicopter resources should be made to meet those requirements.

By late 1966, reassignment of sector and subsector advisory personnel was minimal and authorized only for compelling reasons. General Westmoreland was concerned with obtaining stability of personnel and wanted every effort made to ensure that these positions had at least the minimum degree of continuity. In addition, steps were taken, to extend selected advisers of unique experience or qualifications up to one year beyond the normal tour length. Extensions were to be both voluntary and involuntary, but in practice only those willing to have their tours extended were nominated.

In 1967, with new adviser requirements still being generated, analysts undertook a major study to examine the current advisory effort and review the existing strength authorizations and requirements that had been identified in the fiscal year 1968 South Vietnam armed forces structure. Brigadier General Edward M. Flanagan, Jr., then Training Directorate chief of Military Assistance Command in Vietnam, supervised the study; his objective was to develop the framework on which an improved advisory program could be constructed using the existing organization as a point of departure. Further, the study was to determine if the existing efforts were being properly applied and to recommend any reorientation deemed appropriate. The study recommendations called for a deletion of 1965 advisory spaces from the MACV staff, 940 spaces from the sector advisory chain, and 562 spaces from the tactical advisory chain. The study approved elimination of the spaces from the tactical chain and Military Assistance Command, but the sector chain remained intact.

A second major study undertaken in 1967 was known as Project 640. This study addressed itself to the absence of any central staff agency to co-ordinate and monitor the advisory effort. Past experience had shown that many activities related to the advisory and military assistance effort encompassed many staff areas of interest and that the MACV staff was not appropriately organized to carry out its responsibilities in these matters. The study thus recommended the establishment of a single staff agency to act as the focal point for the advisory effort. By the end of the year, the Office of the Chief of Staff, Military Assistance Command, Military Assistance, (MACMA) had been established under the supervision

[52]

of Brigadier General Donnelly P. Bolton. The mission of the Military Assistance staff was to supervise, coordinate, monitor, and evaluate, in conjunction with appropriate agencies, the joint advisory effort and the Military Assistance Program for the government of Vietnam.

In the same year, 1967, while most of the South Vietnam Army infantry units were being employed in a pacification role, another significant expansion of the advisory effort took place. On a visit to Vietnam in January, the JCS chairman, General Earle G. Wheeler, emphasized the importance of providing physical security to the rural areas and the need "to insure effective transition of this substantial portion of ARVN from search-and-destroy or clear-and-hold operations to local security activities." Wheeler asked, "Is it not essential that these ARVN forces be imbued with the vital importance of their task and be rapidly trained for it, and would it not be wise to assign American officers—as advisors to all ARVN local security detachments of company size and larger?" Subsequent studies indicated the following advantages would accrue by assigning advisers to company-size units:

1. improved combat effectiveness.

2. enhanced unit effectiveness in winning the willing support of the people to the South Vietnam government,

3. improved unit civic action and psychological warfare operations, and

4. expedited completion of the Revolutionary Development (pacification) process.

As a result, additional adviser spaces were requested to provide one additional officer and enlisted man for each battalion conducting independent operations in support of the pacification effort, an effort that U.S. advisers were now indirectly supervising at almost every level.

U.S. Army Special Forces Advisory Programs

On 1 January 1965, U.S. Army Special Forces in Vietnam was organized into four C detachments, five B detachments, forty-four A detachments, and support units. The C detachments were assigned to each corps tactical zone to provide command and control for all U.S. Special Forces elements in the zone, B detachments were intermediate control elements, and A detachments were small teams of twelve to thirteen men which furnished the major portion of the advisory support to the Civilian Irregular Defense Group. Although the number of units was increased as the need arose, their organizational structure remained the same.

[53]

In addition to providing advisory support to the CIDG Program and to the sectors and subsectors assigned to them by the MACV commander, the U.S. Army Special Forces provided advisory support to five other endeavors: the Apache Force program, the Mike Force, the Delta Force, the CIDG motivational program, and special intelligence missions.

The Apache Force involved the use of small, highly mobile teams of indigenous personnel. Teams were commanded by a U.S. Special Forces officer, but worked with regular U.S. units and remained under the control of a U.S. unit commander; their mission was to find and fix enemy forces until larger and stronger units could be brought in. They also secured drop zones and landing zones, located enemy lines of communication, and provided intelligence to the U.S. commander. Each team consisted of four pathfinder, reconnaissance, and combat teams to find the enemy, and three CIDG companies to fix him in place. When U.S. Forces were committed, the Apache Force came under the operational control of the U.S. Commander for the duration of the operation. At the end of the year the program had not been officially implemented, but troops had been recruited in all four corps tactical zones, and CIDG units in the II Corps Tactical Zone were giving this type of support on an informal basis to the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile).

Mike Forces were companies of indigenous tribal personnel recruited and held in reserve by each of the C detachments and at the 5th Special Forces Group headquarters at Nha Trang to provide reaction forces in support of CIDG units within the corp tactical zone. These units were not a part of the Civilian Irregular Defense Group but were recruited and paid by U.S. Army Special Forces.

Delta Forces were similar in concept to the Apache units. The force was advised by a U.S. Special Force detachment and consisted of twelve ten-man hunter-killer teams (each composed of two U.S. Special Forces men and eight Vietnamese Special Forces volunteers) and four South Vietnam Army airborne/ranger companies with U.S. Special Forces advisers down to platoon level. This force was supported by four Vietnamese Air Force H-34 helicopters and two Vietnamese C-47 aircraft. The mission of the Delta Force was to infiltrate Viet Cong controlled territory within the borders of South Vietnam and gather intelligence. The airborne/ranger elements permitted the force to exploit lucrative targets immediately; these hunter-killer teams were also used successfully in gathering target intelligence and in assessing B-52 air strikes.

[54]

The airborne/ranger companies were also used in support of besieged camps, notably Plei Me in Pleiku Province.

The CIDG motivational program consisted of two groups of approximately fifty Viet Cong defectors recruited, trained, and equipped by U.S. Special Forces; in I and IV Corps Tactical Zones the groups moved into areas under pacification, provided their own security, performed civic action, and furnished motivational indoctrination to the indigenous population. Each team had eight U.S. Special Forces advisors.

Concurrent with the increases in U.S. combat and advisory forces, a massive buildup and training program for the Republic of Vietnam armed forces gradually unfolded. This development was consistent with the U.S. basic commitment—to create a South Vietnamese armed force capable of defending South Vietnam with minimal outside assistance. In this respect limited financial resources were always a pressing problem. It was not until mid-1965 with the appearance of the Ky-Thieu regime that a viable government existed which was able to effectively promulgate economic constraints and enlistment inducements and incentives. Only then could force structure plans be instituted with some assurance that means were available to carry them out.

Under legislation and policies in effect before March 1966, the Republic of Vietnam armed forces were supported through the Military Assistance Program. The program was designed to support friendly nations under peacetime conditions and was restricted by worldwide ceilings established by congressional legislation. During this period, dollar ceilings and equipment requirements recommended through submission of plans and programs to the Office of the Secretary of Defense were not necessarily approved. Programming (and eventual delivery) of equipment during this era was governed by the ceilings authorized and the funds appropriated. The expansion and development of the South Vietnam Army was thus circumscribed by these ceilings, and often only those measures which Military Assistance Command felt were most important were approved. Although these ceilings proved to be sufficiently flexible to enable programming to correct major deficiencies, continual price increases and replacement of equipment lost in combat placed a severe strain on available MAP funds. Other factors limiting the development of the South Vietnam Army under the Military Assistance Program included:

1. restrictions governing offshore (foreign) procurement which

[55]

were instituted because of U.S. deficiencies in the international balance of payments;

2. legislative prohibitions on procurement of materiel in anticipation of future appropriations; and the

3. normal practice of supplying older equipment to MAP recipients to purify U.S. stocks.

In March 1966 the support of the Republic of Vietnam armed forces was transferred from the MAP appropriations to the regular defense budget. This measure reduced the strain on the limited MAP funds and allowed U.S.and South Vietnamese military forces to be financed through a common budget. Since then, funding limitations were dependent more on the situation within South Vietnam than in the United States. As a corollary, the government of Vietnam defense budget was limited by U.S. ceilings placed on piaster expenditures. Although these ceilings had no direct limiting effect on improvement of the armed forces, inflationary trends in the economy were a matter of utmost concern when determining the force structure. More and higher paid troops might mean fewer farmers, less taxes, and higher food prices; in this way the piaster ceiling limited expansion. The ceiling also limited U.S. troop spending within South Vietnam.

South Vietnamese manpower was another major problem area in the expansion of the Republic of Vietnam armed forces. Difficulties were caused by an ineffective conscription program and a continually high desertion rate. The conscription program dated back to September 1957, but Vietnamese military authorities had never made any real effort to enforce conscription laws, and by the end of 1965 an estimated 232,000 youths had been able to evade military service. More pressure was now placed on the South Vietnam government to correct this problem.

With expansion underway in 1964, Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, undertook a manpower resources survey to determine if sufficient manpower was available in areas of South Vietnam government control to make up the required military forces needed to defeat the insurgency. The survey estimated that about 365,000 men were available and qualified for the regular forces, and that an additional 800,000 men could meet other force requirements. The survey confirmed that the planned force goals were not impossible, and the results were subsequently used as the basis for manpower planning procurement.

Manpower procurement was assisted by the promulgation of

[56]

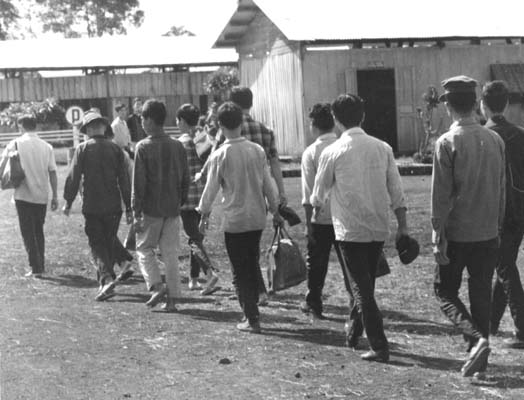

New Territorial Recruits

more stringent draft, laws during 1964. On 6 April the National Public Service Decree declared that all male Vietnamese citizens from twenty to forty-five years were subject to service in the military and civil defense establishment. Subsequent decrees prescribed draft criteria and lengths of service, and another incorporated the Regional Forces and Popular Forces into the regular force (Republic of Vietnam armed forces) organization. A review of the South Vietnam government laws by a representative of the U.S. National Selective Service concluded that the draft laws were adequate, but better enforcement was urgently needed.

Because of the great concern with manpower problems, the U.S. (Embassy) Mission Personnel and Manpower Committee was established in August 1964. The committee was chaired by the MACV J-1 (Personnel Staff Chief) with representation from other U.S. agencies and worked closely with a counterpart South Vietnam committee. The two groups recommended a collective call-up of youths aged twenty to twenty-five followed by a strict enforcement period. The recommendation was approved and in August the government of Vietnam made plans for a preliminary call-up in IV Corps Tactical Zone. The test mobilization pointed out the need for extensive prior planning to include transportation, food, and orientation for the draftees, and these measures were quickly incorporated into a national plan. A Mobilization Directorate was

[57]

also established in August within the Ministry of Defense to direct the call-up and Military Assistance Command supplied advisory support.

A nationwide call-up was conducted from 20 October to 2 November, and a one-month enforcement phase followed to apprehend and induct draft dodgers. Pre-call-up publicity emphasized that this was the last time youths twenty to twenty-five could voluntarily report and that the "tough" measures to apprehend and punish evaders would follow. Initial results were gratifying as over 11,600 conscripts were inducted into the regular forces. Careful planning, effective publicity, and creditability of the enforcement procedures accounted for the success. Unfortunately, the enforcement phase was less than satisfactory. Its implementation required the execution of detailed procedures by province chiefs and local officials, and this execution was not done in a uniform manner. The failure fully to enforce the initial call-up took the sting out of the program, and subsequent draft calls in late November and early December brought fewer recruits than were anticipated or needed to meet force level goals.

Shortages in draftee quotas made it impossible for the Republic of Vietnam armed forces to meet the proposed force level goals for 1965. General Westmoreland was disappointed and in a letter to Ambassador Maxwell D. Taylor on 16 December 1964 summarized his position:

. . . it is imperative for the GVN to act now to vigorously enforce the call-up; widely publicize the program to discharge personnel who have been involuntarily extended, pointing out the obligation of other citizens to bear arms to make discharges possible; acquire sufficient personnel to offset losses through discharge action and attain authorized force levels; take positive action to prepare for further call-up of personnel by year group to increase the force levels according to current plans.

Although this plea was followed by an announcement that draft dodgers would be rounded up, particularly in the Saigon area, the South Vietnam government had taken no positive action by the end of the year, and it was not until April 1966 that the government issued a new series of decrees to enforce existing draft laws and provide punishment for deserters and their accomplices (these new measures, which are discussed later in the chapter, finally did provide some relief of the turbulent manpower situation).

A second action to increase the manpower of the South Vietnam Army was the initiation of a comprehensive recruiting campaign which included extensive publicity, enlistment bonuses, special

[58]

training for recruiters, and accelerated quotas for unit recruiting. These measures together with the call-up enabled the regular forces to exceed their authorized strength levels by the end of 1964. By mid-1965, however, desertions had eroded all regular force increases and by 1966 the problem was still unsolved.

Because of the urgency of the manpower situation, in June 1966 General Westmoreland directed that a study be made to find a comprehensive solution to the problem. The ensuing study warned that if the current situation continued, the rate of manpower consumption would exhaust primary manpower sources by mid-1968 and secondary military manpower sources by the end of 1969. Government of Vietnam manpower resources still lacked over-all central direction; as a result, there were gross imbalances in the manpower pools, which supported the diverse, and often conflicting government programs. The single organization charged with manpower planning, the Directorate of Mobilization, was a subordinate agency of the Ministry of Defense and organizationally was not in a position to exert national control over manpower resources. The study concluded that a requirement existed for orderly distribution of available manpower among users, and that a general mobilization would be preferable to a partial mobilization, although the latter would be better than the existing haphazard system. The study recommended the formation of a study group of interested agencies (the Embassy, U.S. Agency for International Development, Military Assistance Command) to analyze available data on manpower and materiel resources and to do the initial planning required. Afterward, a joint U.S.-South Vietnamese commission should be established to analyze the existing governmental structure and determine what additional machinery would be required to accomplish a general mobilization. General Westmoreland agreed with the study's recommendations and on 15 June sent a letter to the U.S. Ambassador supporting its proposals.

General Westmoreland recognized that the demands on military manpower were great and that there was also a heavy and increasing demand for qualified manpower by the private and governmental sectors of South Vietnam. Uncoordinated attempts to correct the military problem would have adverse effects on the remaining sectors. While the South Vietnam government had failed to organize itself to meet the heavy calls on its manpower, solutions demanded that a determination be made of total manpower assets and total requirements, and that the two then be balanced. Aware of the serious implications of total mobilization, Westmoreland recommended that a U.S. committee to study mobilization be

[59]

established under the direction of the Embassy and include USAID and MACV representation. A joint U.S.-South Vietnamese commission would then be set up to integrate the preliminary aspects of the study into a combined program for mobilization which would be appropriate for both governmental and social structures.

When no action was taken on this proposal, General Westmoreland sent in May 1967 a second letter to the U.S. Ambassador on the subject. He again stressed the need for a mobilization plan. As a result, the ambassador established a special manpower advisory mission composed of economic, labor, and management specialists from the United States. This mission, in coordination with the Embassy and Military Assistance Command, developed the basic planning necessary for mobilization. Discussions then began with the Vietnamese government, and on 24 October 1967 laws outlining plans for a partial mobilization were decreed. However, there was no implementing legislation and some question existed as to whether the South Vietnam government was strong enough to carry the measures out. At the time, governmental stability was still in critical condition and anything that might threaten that stability or cause the government to be unpopular had to be treated with care.

Desertions continued to be a thorny matter throughout this period. The encouraging gains in the manpower situation made in late 1964 lasted only briefly owing to the rising number of “unapproved leaves” during 1965. Military Assistance Command undertook several studies to determine the causes for the excessively high desertion rates and noted the following contributing factors:

1. overly restrictive leave policies;

2. family separation;

3. lack of command attention to personnel management and soldier welfare such as pay, housing, and promotions;

4. general dissatisfaction with military life;

5. tolerance of military and civil authorities toward desertion;

6. apparent public apathy toward the war;

7. increasingly heavy combat losses;

8. poor apprehension and punishment of offenders; and

9. misuse of certain types of units (especially Ranger and Popular Forces) by higher headquarters.

Desertions were especially prevalent in III Corps Tactical Zone because of the proximity of Saigon, where a deserter could readily

[60]

lose himself. The nearby South Vietnam Army 5th Infantry Division alone lost 2,510 soldiers through desertion in the first quarter of 1966.

To attack the roots of the desertion problem, Military Assistance Command pressed many corrective programs and actions during the next several years. Among the more significant measures were the streamlining of administrative procedures, establishment of an Adjutant General's School, a liberal awards policy, improved leave policies, improved promotion system, battlefield promotions, direct appointments, and improvements in the standard of living for the South Vietnam Army to include pay increases and expansion of the commissary system, a self-help dependents housing program, and veterans rehabilitation programs. These activities had only mixed short-term success and by themselves represented only a part of the larger problem noted above.

Desertion rates tended to be confusing because the South Vietnam government classified as deserters those individuals with less than ninety days' service who were absent without leave (AWOL) more than six (later fifteen) days, and those who were absent more than fifteen days while en route to a new duty station. It was also suspected that desertion and recruiting statistics included some persons who had illegally transferred from one force to a more desirable one-for example, from the South Vietnam Army to the Popular Forces. Military Assistance Command had proposed substantial changes in this approach and recommended that a uniform period of thirty days unauthorized absence be the criterion; after that time the individual would be punished by the commander and a punishment book used to record the action. But Republic of Vietnam armed forces were unresponsive to these recommendations.

Orders published during 1965 removed all effective disciplinary restraint to desertion by allowing deserters to escape prosecution by signing a pledge not to desert again, after which, rather than being jailed, they were returned to duty. Before this step the armed forces code of military justice had provided strict penalties for desertion in wartime, ranging from six years imprisonment to death. The reduction in severity of punishment for desertion was partially explained by the overcrowded conditions of Vietnamese jails and Vietnamese unwillingness to levy harsh penalties for what was not considered a serious crime. But desertions from all components of the Vietnamese armed forces had risen from 73,000 in 1964 to 113,000 in 1965 and it seemed likely that this trend would continue in 1966.

To remedy this state of affairs, a series of decrees in April and

[61]

July established new penalties for deserters and their accomplices. First offenders would be punished by making them "battlefield laborers" for a minimum of five years; all pay, death, and disability benefits were forfeited. Battlefield laborers were to perform such duties as repairing roads and bridges, transporting ammunition, digging emplacements, burying the dead, setting up temporary camps, and in general performing hard labor details. Repeat offenders were to receive increased punishment; for a second offense, the penalty was five to twenty years hard labor; and if a deserter escaped while undergoing punishment, the punishment was doubled for the first offense and was death for the second. Civilians convicted of aiding and abetting deserters were to be sentenced to five years punishment at hard labor.

Emphasizing the gravity of the desertion problem and the importance he attached to the new laws, in July 1966 General Westmoreland sent a communiqué to all advisory personnel stating his conviction that "The present for operations strength of each unit must be raised. The minimum acceptable number to conduct a battalion operation is considered to be 450 men. The most important single improvement that can be made in the RVNAF to achieve this goal is a solution to the desertion problem; and to this end, advisory effort must be focused."

After a trip to the Van Kiep National Training Center in early July, the MACV J-1 reported that as a consequence of Vietnamese armed forces new AWOL and desertion measures, improvement was evident; no AWOL's or desertion occurred in the 2,000-man camp for the preceding seven days. Later, as the good results of the decrees became more apparent, the MACV commander congratulated the Chief, Joint General Staff, for the forceful and enthusiastic manner in which the desertion problem was being attacked. But privately, his optimism remained restrained.

Throughout the year the campaign continued to thrive. Posters highlighted the consequences of AWOL and desertion, and letters went to families of all deserters urging their return. On 8 August another desertion decree granted amnesty to individuals who had deserted from one force in order to join another and who were serving honorably in the force to which they had deserted.

In an effort to assist the South Vietnam Army reduce its desertion rate and improve its combat effectiveness, General Westmoreland directed that U.S. units adopt certain Vietnam Army units. Close association was planned between the U.S. 1st Infantry Division and the South Vietnam Army 5th Division and between the U.S. 25th Infantry Division and the South Vietnam Army 25th Division. The program was designed to provide U.S. help in estab-

[62]

lishing adequate exchange and commissary services, in erecting adequate dependent housing, and in combined tactical operations.

The USMACV also co-operated by preventing American civil and military agencies and contractors from hiring deserters. In October 1966, Military Assistance Command published a directive which required U.S. Agencies to screen their employees for deserters and draft evaders, and which specified the documentation an individual had to present before he was hired. Since the directive did not apply to other Mission agencies, however, loopholes still existed. To plug these holes, the MACV commander asked the embassy to publish a similar directive which would apply to U.S. Agencies not supervised by Military Assistance Command.

Throughout 1966 and 1967 progress was slow and painful. But through continued emphasis on the problem by advisers, together with the initiation of programs to attack the root causes of desertion (such programs, for example, as improving leadership, personnel, management, personnel services, and training) and stricter enforcement of desertion laws, a certain amount of headway was made. By the end of 1967 desertions had fallen by about 30 percent, and the desertion rate (per thousand) had dropped from the 16.2 of 1966 to 10.5. However, desertions continued to constitute one of the most critical problems facing the South Vietnam Army. Strong and continuous measures emphasizing the need for improvement of leadership, of the day-to-day living environment of the soldier and his dependents, and of the motivation and indoctrination of the citizen were mandatory if the rate was to be kept to an acceptable level.

Economic and Social Improvement

On 11 January 1967, the MACV commander met with his principal staff officers and component commanders to discuss means of improving South Vietnam armed forces effectiveness. The new role of the South Vietnam Army soldier in the pacification program emphasized the need to improve his lot in life. Obviously a program designed to improve the well-being of the people would not succeed if one of the main participants was worse off than those he was trying to help. At the time of the meeting, the four most important areas for consideration were field and garrison rations, food for South Vietnam Army dependents, cantonments, and dependent housing.

The South Vietnam armed forces pay system did not include a ration allowance; subsistence-in-kind or increased pay would have improved the system, but whatever measures were adopted had to

[63]

be flexible enough to meet local conditions. U.S. help might be extended in several ways; one of the most practical was assistance-in-kind in the form of staples. The South Vietnam government would pay for the items, and the United States would use the money for expenses in South Vietnam. Captured rice was another source of rations. The MACV commander directed the commanding general of U.S. Army, Vietnam, to assume responsibility for improving field ration utilization, for garrison ration commodities, and for the distribution system. When the field ration was issued, 33 piasters (about 25 cents) was deducted from the soldier's pay; as this reduction lowered the food-buying power of the family man, he preferred not to receive the ration and sold it when it was issued to him. Thus the United States recommended that the ration be issued free of charge and in lieu of pay increases. The garrison ration consisted of certain basic foods distributed through South Vietnam armed forces quartermaster depots at fixed prices and locally procured perishables and was supported through payroll deductions. Only rice was occasionally short, and U.S. Army, Vietnam, requested that the South Vietnam government ensure that sufficient allocations of rice be made available to the Vietnamese armed forces. Also noteworthy was the establishment for the first time, on 21 February 1967, of unit messes in regular armed forces and Regional Forces company-size units.

U.S. Army, Vietnam, was also tasked with improving the armed forces commissary system with respect to the use of dependent food purchases and to consolidate the Post Exchange and Commissary into one system. By early May negotiations for U.S. support of the Vietnamese armed forces commissary system had been concluded. The agreement stipulated that the United States would supply rice, sugar, canned condensed sweetened milk, canned meat or fish, cooking oil, and salt (or acceptable substitutes) for one year at a maximum cost to the United States of $42 million. The food items were to be imported into South Vietnam tax-free, for exclusive distribution through the armed forces commissary system. No food items were authorized for transfer to other South Vietnam government agencies, but would be sold only to armed forces personnel and their dependents at a cost which would be significantly less than on the open market, but still high enough to produce sufficient revenue to fund improvements to the system and to allow eventual U.S. withdrawal, and for its extension, if mutually agreeable. Piaster receipts from sales would remain the property of the commissary system and were not authorized for any other South Vietnam government agency; the government also agreed to provide the United States with a monthly financial statement. The agreement

[64]

contained provisions for continuation of the system after U.S. withdrawal, if mutually agreeable. The formal accord was signed on 26 May by Commander, U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, and Chief, Joint General Staff, at DA Nang.

The Cantonment Program consisted of two parts; first, cantonments programmed and funded in the government of Vietnam defense budget (50 percent government of Vietnam and 50 percent U.S. Joint Support Funds) and, second, the U.S.-sponsored cantonment construction plan which provided cantonments for the force structure increase units of fiscal years 1965, 1966, and 1967. The Vietnamese armed forces cantonment program was hampered somewhat by competition for limited materiel, labor, and transportation. The major difficulty was the lack of a master plan, compounded by possible changes in the location of South Vietnam armed forces units participating in pacification.

The Vietnamese armed forces Department of Housing Program had been initiated in April 1961 for soldiers below the grade of sergeant. In 1964 the program was expanded to include all ranks and a separate Regional Forces program was begun. No Popular Forces housing existed, since individuals normally resided in their own homes. The calendar year 1967 government of Vietnam defense budget contained 300 million piasters to complete previous building programs and to construct both officer and enlisted quarters; the houses to be erected with the 1967 funds were ten-family units, providing each family with a living area 3.5 meters by 10.5 meters. Spiraling costs were expected to limit new construction to no more than 3,000 units. On 11 January 1967 the MACV commander assigned the principal U.S. responsibility for the program to U.S. Army, Vietnam, while the MACV Directorate of Construction was responsible for co-ordinating policy and programs and for funding.

As mentioned briefly in Chapter II, Military Assistance Command had completed a study in the last half of 1964 addressing itself to the Vietnamese armed forces levels. The study had proposed two alternatives: alternative one provided for an increase of 30,339 men in the regular forces, 35,387 in the Regional Forces, and 10,815 men in the Popular Forces; and alternative two provided for an increase of 47,556 in the regular forces and identical increases in the Regional and Popular Forces. Alternative one was approved, with some modifications, on 23 January 1965, and force levels were fixed at 275,058 for regular forces, 137,187 for the

[65]

Regional Forces, and 185,000 for the Popular Forces. But by 13 April 1965, with no improvement in the military or political situation, alternative two increases were also approved and the regular force ceiling rose to 292,305. These increases were used to raise the number of South Vietnam Army infantry battalions from 119 (93 infantry, 20 Ranger, and 6 airborne) to 150. To avoid activating new headquarters units, one new infantry battalion was added to each Vietnam Army regiment (a later adjustment to 149 battalions was made when the activation of two additional airborne battalions took up the spaces of about three infantry battalions). Activation of these units began immediately, and by the end of the year twenty-four were either in the field or in training areas.

Planning and study of the force structure requirements was a continuous activity. By 5 November 1965, additional increases had been requested to provide for a regular force of 311,458 troops in fiscal year 1966 and 325,256 in fiscal year 1967. The fiscal year 1966 increases were primarily to flesh out the existing structure in the areas of command and control, psychological operations, and the replacement pipeline. Pipeline increases were needed to reduce the tendency to "fill" units with untrained personnel and allow the growing force structure a longer manpower lead time. As training became more complex, both longer lead times and greater pipeline increases would be necessary.

Increases for fiscal year 1967 included 3 infantry battalions (to replace those traded off for 2 airborne battalions in 1965), 1 infantry regiment, 1 artillery battery (105-mm.), 2 military police companies, 1 Marine battalion, 1 civil affairs company, 4 psychological warfare companies, 81 Regional Forces companies (to accommodate the expanding pacification program), and 15,000 spaces for the Regional Forces and other augmentations to increase the capability of existing Vietnamese armed forces units. Larger increases were needed, but the manpower situation would not make such increases possible. The U.S. Secretary of Defense gave his verbal approve for the new ceilings in Saigon on 28 November 1965.

The requested force increases represented the maximum strength that the manpower base could support. Accessions of 20,000 per month would be required to attain and sustain these levels; maintenance of these levels past 1969 would call for the recovery of significant manpower resources from Viet Cong controlled areas or the extension of military terms of service and recall of veterans. Manpower limitations were of course qualitative as well as quantitative. It was becoming increasingly difficult to obtain and train able leaders for the rapidly expanding forces.

[66]

The formation of new units continued throughout 1966. However, the general manpower shortage was making it difficult to sustain this high growth rate. A moratorium on the activation of new units was finally called, and the fiscal 1966 Vietnamese force structure was stabilized at a total strength of 633,645 consisting of 315,660 regulars (277,363 Army, 15,833 Navy, 7,172 Marine Corps, and 15,292 Air Force), 141,731 Regional Forces, and 176,254 Popular Forces.

Discussions between Military Assistance Command and the Joint General Staff on the manpower situation during May and June 1966 explored the possibility of suspending unit activations called for in the fiscal year 1967 force structure. On 30 June General Westmoreland wrote the JGS chief that the objectives of the fiscal year 1967 force structure might not be attainable and should be re-examined to afford a more realistic alignment of forces as a means of increasing combat effectiveness. He cited desertions and unauthorized units as major causes for the unsatisfactory strength situation, and asserted that it was imperative for the activation of additional units to be suspended for the remainder of 1966. Units authorized for early activation to meet operational requirements were exempted from the suspension.

General Westmoreland's immediate concern was the declining present-for-combat strength of the Vietnamese Army infantry units. MACV studies showed that, as of 28 February 1966, South Vietnam Army divisions averaged 90 percent of authorized strength, and battalions averaged 85 percent. But only 62 percent of authorized strength was being mustered for combat operations in the field. There were two major reasons for this disparity. First, division and regimental commanders had organized a number of ad hoc units such as strike and reaction forces, reconnaissance and security units, and recruiting teams. Second, large numbers of deserters, long-term hospital patients, and soldiers killed in action continued to be carried on the rolls long after their names should have been deleted.

In reviewing the South Vietnam Army strength problem, planners particularly scrutinized unauthorized units. One type of unit found in almost all infantry regiments was the reconnaissance company. That a need existed for this kind of unit was indicated in a subsequent study. Approval was given to develop the organization for a regimental reconnaissance company which could be incorporated into the normal force structure.

[67]

In order to give his review efforts a broader base, Westmoreland tasked the U.S. Senior Advisors in each of the four corps tactical zones and other major armed forces components to initiate detailed support of the South Vietnamese organizations. Were they all being used according to their organizational mission, did they contribute effectively to the over-all mission, or could they be reduced in TOE strength, absorbed into other units, or deleted entirely? Replies from the field cited only a few examples of improper employment; in some instances such employment was caused by lack of proper equipment (for instance, armored cars in Regional Forces mechanized platoons), and in others it was due to local reasons (such as using reconnaissance companies as housekeeping units). In I Corps Tactical Zone the Senior Advisor felt that the Ranger battalions though not properly employed still were contributing to the war effort. In IV Corps Tactical Zone the only significant-shortcoming noted was the continued use of provisional regimental reconnaissance companies. The survey located quite a few units which could be deleted entirely or which could be absorbed into other units. There were several inadequately trained scout companies which, if they failed to respond to organizational training, were recommended for deletion, conversion to Regional or Popular Forces, or absorption into other units. It was also recommended that armored units be absorbed into the regular infantry divisions. But in most cases the U.S. Senior Advisors felt that assigned Vietnamese Army units were necessary and contributed to the over-all mission.

In 1967, with the authorized force level still frozen at the fiscal year 1966-67 strength of 633,645, planning for fiscal year 1968 force levels began. On 26 April recommended fiscal year 1968 force levels were submitted and proved substantially higher than the present ceiling. The fiscal year 1968 program called for a total strength of 678,728 with the Vietnamese Army level at 288,908, Regional Forces at 186,868, and the Popular Forces at 163,088. Whether South Vietnam could support further increases was a question mark.

The development of fiscal year 1968 force structure was long and complex. Inflationary trends, South Vietnam government mobilization policies, the balance of forces, and especially the availability of manpower assets were considered. The new force level was based on an estimated population of 16,500,000; this number was considered sufficient to support the new levels through December 1968 but projections beyond that date were tenuous. A review conducted in late May tentatively identified additional spaces needed in the regular force, and the fiscal year 1968 force

[68]

level was further increased to 685,739. The most important cause of these increases was the need for additional territorial (Regional and Popular Forces) units in areas recently brought under friendly control. Such expansion also increased the recruiting base, but the lag between the growth of the recruiting base and the growth of the Vietnamese Army was considerable. Thus the May review again addressed the question of whether these increases were attainable within the planned time frame, taking into account leadership potential, recruiting capability, equipment availability as well as available manpower and budgetary limitations. With certain augmentations, the training base and logistical support structure was considered adequate to support an increase in the force structure, but available leadership resources were likely to be severely strained. However, as before, to strain these resources appeared to be the more desirable alternative.

In July 1967 the Joint Chiefs of Staff asked that the revised fiscal year 1968 force level be reconciled with the earlier estimates. Military Assistance Command replied that the structure review had considered alternative force structures and various mixes of Regional and Popular Forces and regular forces. When examined within the context of projected U.S. troop deployments, anticipated enemy activities, and projected operational plans, the April estimate had proved too low. In addition, the fiscal year 1968 force levels were based on the assumption that the South Vietnam government would mobilize its manpower in January 1968 by lowering the draft age to nineteen, extending tours by one year, and recalling selected reservists. The U.S. Mission had long urged such measures and the JGS chief seemed to view the prospects favorably. While the Vietnamese armed forces manpower resources would support these levels, they were the maximum that could be sustained. The armed forces perennial leadership problem could be partially solved by retraining and calling up qualified and experienced combat leaders, phasing unit activations over a two-year period, and employing U.S. training teams with new Regional Forces companies. In the end, the revised fiscal year 1968 force level was confirmed and a force level of 685,739 (303,356 South Vietnam Army, 16,003 Navy, 7,321 Marine Corps, 16,448 Air Forces, 182,971 Regional Forces, and 159,640 Popular Forces) was authorized.

In October 1967 the Secretary of Defense approved the fiscal year 1968 force level of 685,739, contingent upon the implementation of the necessary manpower mobilization measures. But all activations were to be handled on a case-by-case basis until a joint MACV JGS activation schedule could be developed and approved. The activation schedule would be dependent on manpower avail-

[69]

ability, recruiting experience, the continued development of leadership potential, the maintenance of adequate present-for-operations strength, the availability of equipment, and the capability of the support base. Again on 18 November the JGS chief was informed that many South Vietnam Army infantry units still had extremely low present-for duty or field strengths. But despite this situation, an activation scheduled for the new Army units was approved on 9 December 1967. At the end of 1967 actual South Vietnam armed forces strength was approximately 643,000. The new units to be activated between January and April 1968 made mandatory increased recruiting through new mobilization decrees.

In January 1967 General Westmoreland approved a step which he had vetoed only months before-withdrawal of MAP support from unproductive or ineffective Vietnamese army forces units. The MAP Directorate initiated a program aimed at identifying unproductive units, and in April it sent a letter to Chief, Joint General Staff informing him of the program and potential candidates to be deprived of support. The U.S. Navy planned to reduce its support of the South Vietnam Navy by $7,800 during fiscal year 1968 by discontinuing support for two ex-fishing boats because they were not slated to perform any mission assigned to the Vietnamese Navy. Other likely candidates from the Vietnamese Navy were underwater demolition teams not properly employed, and a light cargo ship which was used in a training role rather than in logistic support. The South Vietnam Army also had units nominated to have MAP support withdrawn. In II Corps Tactical Zone the 22d and 23d Ranger Battalions and in III Corps Tactical Zone the 5th Armored Cavalry Regiment had ineffective leadership and were assigned inappropriate missions. Restoration of support would be contingent upon institution of corrective action. Westmoreland wanted the program continued with a final evaluation of unproductive units every June and December; this action would give Vietnamese armed forces time to take remedial actions. Curtailing support to regimental headquarters companies could present serious problems, but a possible solution would be to inactivate the regiment and use its productive battalions elsewhere. Loss of a battalion was not desirable but, if necessary, a regiment could learn to operate with three battalions instead of the four that most had. General Westmoreland stated that Military Assistance Command was the administrator of U.S. funds and equipment and was responsible for ensuring productive utilization of U.S. resources.

The JGS chief wrote to the MACV commander on 3 May requesting that the Joint General Staff and the MACV staff work together to improve substandard units. The MACV commander

[70]

concurred and directed the MACV staff to co-ordinate directly with the joint General Staff in improving substandard Vietnamese armed forces units as they were identified. Since corrective measures had been initiated in the 22d and 23d Ranger Battalions and in the 5th Armored Cavalry Regiment, General Westmoreland decided to continue military assistance to them, but he proposed that the units be placed on probation until their effectiveness was conclusively established.

In early August the MAP Directorate identified additional Vietnamese armed forces units for possible withdrawal of MAP support. Eighteen Regional Forces companies, sixteen Popular Forces platoons, and fourteen Popular Forces squads constituted the majority of the unsatisfactory or marginal units. Besides these, two South Vietnam Army infantry battalions, an armored cavalry regiment, an engineer battalion, a reconnaissance troop, and an armored car platoon were identified as unsatisfactory. Deficient leadership, defective training, obsolete equipment, and meager personnel strength caused the low ratings. Deficient leadership was present in all but seven instances. One company commander was described as "seldom present" and "preoccupied with his own safety and comfort," while another was "absent for a two-month period due to self-inflicted leg wound." Obsolete equipment caused two poor ratings, and low personnel strength appeared in twenty-six others. Defective training programs accompanied deficient leadership in almost every instance. Further force increases were obviously contingent on whether Vietnamese armed forces leaders could bring their poorer units up to acceptable standards.

During this period both the missions and composition of the territorial forces became stabilized. The Regional Forces were voluntary units organized within a province for use within that province and consisted of rifle companies, riverboat companies, and support units. The Popular Forces were voluntary locally recruited forces, organized into squads and platoons, used primarily as security forces in villages and hamlets. Regional Forces strength for fiscal years 1965 and 1966 had been set at 137,187 men organized into 759 companies; fiscal year 1967 force structure authorized 888 companies, an increase of 121 over fiscal year 1966, with a strength of 155,322 men. The emphasis on revolutionary development at the Honolulu conference meant that more Regional Forces companies would be needed to extend South Vietnam government influence into recently cleared areas or into national priority areas.

[71]

In order to gain lead-time, 31 companies scheduled for activation before 1 July, 21 were programmed for national priority areas, and 10 for corps priority areas. The remaining fifty companies were scheduled for activation between July 1966 and June 1967.

General Westmoreland believed that the territorial forces were one of the keys to pacification, but felt they were not receiving enough attention from the South Vietnam government. U.S. financial support for continual larger force levels was not enough. The Regional and Popular Forces depended on volunteers to swell their ranks, and often such individuals joined only to escape the more burdensome service in the regular Army. As Vietnamese armed forces recruiting pressures grew more intense, however, competition for manpower increased and territorial strength declined in 1965 and 1966. High desertion rates of the territorial forces and recruiting restraints placed on them by the Joint General Staff in 1966 were the immediate causes. These restrictions prohibited the Popular Forces from recruiting men from twenty to twenty-five years of age; later in the year further bans prevented them from recruiting those in the seventeen to thirty bracket. To make matters worse, the restrictions were retroactive to 1 January 1966, making the status of some 17,000 recruits in the restricted age group illegal. Although these restrictions were later relaxed in September and the Popular Forces were authorized to retain the recruits in the retroactive category, the change came too late to compensate for the losses of the first nine months.

The Regional Forces and Popular Forces command and control structure presented another dilemma. Territorial forces constituted approximately 50 percent of the total South Vietnam armed forces structure, but, in view of their size, they enjoyed a much smaller proportion of support. They were far down in priority for training, equipment, and leadership, resulting in marginal or unsatisfactory ratings in almost every category of their activities. The root of the problem was the chain of command. The Regional and Popular Forces central headquarters, whose mission was to command and manage the Regional and Popular Forces units throughout the country, did not have operational control of the units (except for the seven Regional and Popular Forces national training centers); the actual control of the Regional and Popular Forces was exercised by corps and divisions through sector commands.

In September 1966 the government of Vietnam decided to integrate the separate Regional Forces and Popular Forces headquarters at the Joint General Staff, corps, division, sector, and subsector into the regular military commands at these echelons. Two advantages

[72]

ensued from this arrangement: fewer people were required for staff duty, thus releasing personnel for duty in the field; also, the new arrangement would provide more efficient logistical support of Regional and Popular Forces units. The integration placed operations, administration, and support of the Regional and Popular Forces under the responsible tactical commanders throughout the armed forces and thus provided for a more unified effort throughout the chain of command. The organization also placed Regional and Popular Forces troops under the command of sector and subsector commanders; since these commanders were closely connected with pacification, it was thought likely that Regional and Popular Forces troops would be used in their proper role of pacification support. A new position, the Chief of Central Agency and concurrently Deputy Chief of Staff for Regional and Popular Forces at Joint General Staff of the South Vietnam armed forces, was formed and made responsible for recommending policy and guidelines for the Regional and Popular Forces. The reorganization was to take place in two stages and be completed by the end of the year. It was mid-1967, however, before the new command relationships had been sorted out and the more serious problems resolved.

Following the Manila conference, with its proposal to withdraw U.S. troops and Free World Military Assistance Forces from South Vietnam within six months, as the other side withdrew and stopped infiltrating, and as the level of violence subsided, Military Assistance Command noted that the conference communiqué did not provide for U.S. military advisory personnel to remain after a withdrawal. In these circumstances, besides strengthening the civilian components of the mission, it was considered prudent to consider immediate organization and training of a national constabulary under the guidance of Military Assistance Command. One suggestion was to draw upon Regional Forces and Popular Forces as a manpower source, while another was to designate the Regional Forces as a provincial police force and Popular Forces as a village police force. General Westmoreland agreed that early organization, with MACV assistance, of a constabulary was necessary to provide a force which would not be subject to negotiations. It appeared to Westmoreland, however, that direct military participation should be terminated as soon as possible. Several advantages were to be gained from building on the Regional and Popular Forces base, since those forces, besides constituting an organized force, already had an assigned mission which would not be changed substantially by conversion; other paramilitary forces could be readily integrated into the program as well.

To organize a constabulary required planning and study and

[73]

the development of a concept of organization and operation. To provide the planning and development, an interagency study group was formed. The group completed its work in December 1966 and recommended that a Rural Constabulary be formed, utilizing the Police Field Force as a base and opening up all manpower resources, including the armed forces, to recruitment. The study group also proposed using Popular Forces personnel as a recruiting base for pacification cadre. General Westmoreland, however, continued to support the concept of converting the Regional and Popular Forces into a territorial constabulary and pointed out the uselessness of pacification cadre without local security supplied by a strong popular force or its equivalent.

The Civilian Irregular Defense Group

At the beginning of 1966 only 28,430 CIDG personnel were enrolled in 200 companies, although a strength of 37,250 was authorized for both fiscal year 1966 and 1967, which would have allowed a total buildup of 249 companies.

In 1965 a U.S. study group formulated a detailed plan for converting the majority of CIDG companies to Regional Forces companies by the end of 1965 and the remainder by the end of 1966. On 15 September 1965, the Joint General Staff had agreed to the plan in principle, but recommended that the conversion be voluntary; the Joint General Staff recognized the desirability of incorporating all military and paramilitary organizations into the South Vietnam armed forces, but recognized that the unique role of Civilian Irregular Defense Group remained valid for the immediate future. In concept, as the areas in which CIDG units were operating became more suited for Regional Forces operations, the CIDG units would be converted to Regional Forces. U.S. and South Vietnamese Special Forces then would move to other locations and recruit and train other CIDG forces. General Westmoreland recommended slow and deliberate conversion, with the use of two or three camps as pilot models.

Initially, three camps were chosen for conversion: Plei Do Lim in Pleiku Province, Buon Ea Yang in Darlac Province, and An Phu in Chau Doc Province. Numerous delays ensued before the test was completed in August. Initial problems centered around the disadvantages of conversion to the participants: reduced resupply capability, since the U.S. Army Special Forces was no longer supplying the camp; a decrease in pay to some unmarried personnel when converted; and increased pressure on South Vietnam armed forces deserters who had joined the Civilian Irregular Defense

[74]

Group. When coupled with the traditional distrust of the Montagnards for the South Vietnam government, the unpopularity of conversion and its temporary suspension in 1966 was not surprising.

Paralleling the expansion of the South Vietnam armed forces massive efforts were made to improve the quality of the armed forces and training programs represented one of the most efficient ways to bring this about. While the old adage that units "learn to fight by fighting" is true, fighting alone was not enough. In Southeast Asia it was necessary to win and to keep winning a complex war where set-piece battles often gave only the illusion of victory. Thus, the advisory effort was devoted to creating not only an army that was tactically and technically proficient, but also a professional one that could cope with the social, economic, and political turmoil in which it operated and from which it was derived.

The greatest obstacle in improving and training the armed forces was the lack of qualified leadership at all levels, both officer and noncommissioned officer. This deficiency had been a continuing source of concern and one which seriously affected all efforts to create an effective combat force. Battalion and company commanders were often inexperienced and lacked initiative; few operations were conducted in the absence of detailed orders. Senior commanders issued directives, but failed to supervise their execution, and results were usually negligible. U.S. advisers continually cited poor leadership as the foremost reason for unit ineffectiveness. But with the lack of replacements, unsatisfactory commanders were seldom relieved. This situation was an unfortunate by-product of the rapid expansion of the military without a strong base of experienced leaders; the shortage of able personnel to occupy civil administrative positions only made the military problem more severe.

Looking back on his career as Deputy Senior Advisor in II Corps Tactical Zone in 1966-67, Major General Richard M. Lee concluded that the basic problem

was not a lack of knowledge or training facilities to do the job expertly, but a disinclination of many ARVN officers to take the time and effort to train their troops carefully and thoroughly. The Vietnamese had been intermittently at war since World War II with only an occasional respite; many ARVN officers looked at the war as a long pull rather than on a one-year basis, as we Americans tended to see our personal contributions. They tended to take the weekends off. They were not inclined to go in for the intensive training methods that the US forces were accustomed to at that time.

[75]

Lee went on to point out that many Vietnamese officers were not "training oriented" and also noted the class bias of the officer corps:

It appeared to me that the ARVN officers as a group came from the middle and upper-educated classes of Vietnamese society, comprised primarily of a few of the old aristocracy, the officer group created by the French military during the Indo-China War, and the rising Commercial/business classes from the major cities, particularly Saigon. While there were many outstanding exceptions, surprisingly large numbers of this officer corps seemed to lack aggressiveness, leadership ability, and a full professional commitment to their profession. This had a pervasive, adverse impact on training. Considerable numbers of ARVN field officers seemed to prefer rear area assignment rather than combat command. Some sought political jobs (in provinces and districts), I reluctantly conclude, so that they could avoid the rigors, boredom, and dangers of training and combat, and a few (I suspect but cannot prove) [sought] to use their positions for personal or even financial advantage.

Lee ended this candid assessment by suggesting a democratization of the corps by "integrating and broadening the officer base, making it more egalitarian and opening a means of sought-after upward mobility."

Before July 1966, efforts to improve leadership were isolated and had met with little success. That month a Command Leadership Committee was formed consisting of the South Vietnam Joint General Staff chairman and five general officers. Under MACV guidance, the committee was charged with the formulation of comprehensive programs to improve leadership quality and personnel effectiveness throughout the Vietnamese armed forces. Several noteworthy actions resulted. A career management program for officers was implemented which provided for rotation of officers between command, staff, and school assignments, and the assignment of newly commissioned officers to combat units. The program was similar to the career management policies of the U.S. Army. In 1967 the Officer Annual Promotion Procedure incorporated efficiency reports into the selection process for the first time and opened the findings of the board to their military audience; the number of officers considered, the number selected, and the point average of each were all published. That same year, the Noncommissioned Officer Annual Promotion Procedure also made full disclosure to the field of the board's proceedings and considered noncommissioned officers strictly on their merits; unlike past practice, no consideration was given to unit noncommissioned officer strength, and imbalances were corrected through unit transfers after the promotion announcements had been made. A revised selection process for attendance at the Saigon Command and General Staff

[76]

Training At Phu Cat

College was instituted; student selections were made by the Joint General Staff rather than by allocating quotas to subordinate commands. The current position and promotion potential of candidates would weigh more significantly. A Vietnamese-authored Small Unit Leaders Guide was published containing sections on leadership, discipline, troop leading procedures, and company administration and was issued to all company commanders and platoon and squad

[77]

Range Practice With New M16 Rifle

leaders. A revitalization of the South Vietnam armed forces Inspector General system was also undertaken; reforms were patterned after the U.S. Inspector General system and incorporated personal complaint and redress procedures. Military Assistance Command provided sixteen Inspector General advisers to assist and monitor the effort. Finally a comprehensive Personnel Records Management Program was implemented in an effort to establish an accurate, responsive system for qualitative and quantitative identification of all personnel.