CHAPTER I

Early Involvements and Developments

On 24 November 1963 a large Viet Cong force attacked the Special Forces Camp at Hiep Hoa, Republic of Vietnam. Sergeant First Class Kenneth M. Roraback, working in the radio room, immediately notified higher headquarters of the situation. Heavy enemy fire damaged his gear and knocked out a portion of the radio room, but Sergeant Roraback remained at his station and attempted to repair his radio. When it became apparent that the radio was beyond repair, he destroyed what was left of the equipment, maneuvered through hostile fire, and used a light machine gun to cover withdrawal. He was taken by the Viet Cong and died in captivity. He was awarded posthumously the Silver Star for gallantry in action.

Sergeant Roraback's story points up more than his bravery. The early date, 1963, is a reminder that Army communicators were on duty in Vietnam, advising and supporting the Vietnamese Army, well before American tactical units were committed in 1965. The technical proficiency of Sergeant Roraback exemplifies the training and dedication of the American combat communicator the very fiber of communications in Vietnam. His courageous fight once he had accomplished his technical mission says that combat communicators were fighters as well as technicians who played vital parts in operating and maintaining the links that held American combat forces together.

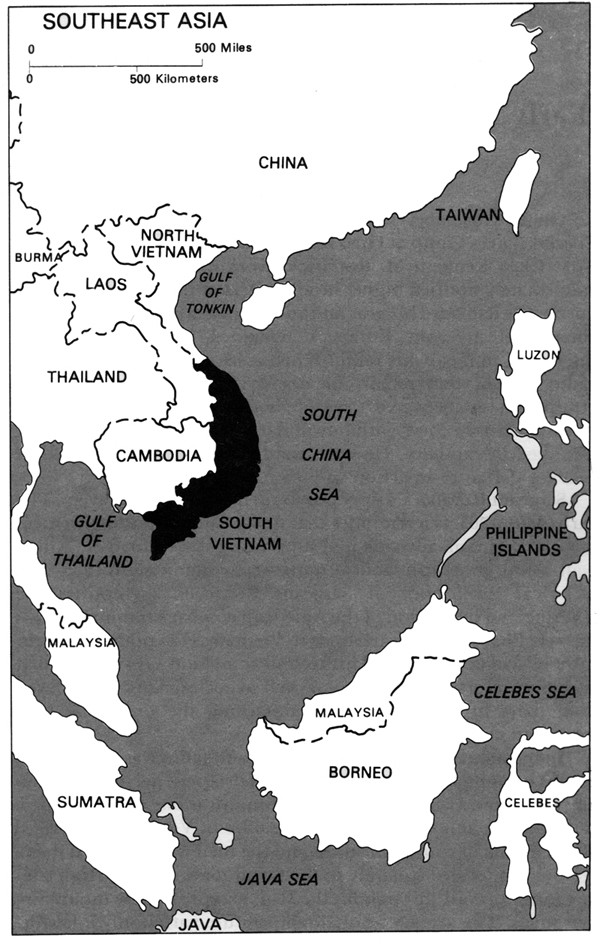

In most tactical operations in Vietnam, radio was the primary means of communication. Telephone, teletypewriter, data, facsimile, television, visual, and sound communications were also used. The climate and terrain of the Republic of Vietnam challenged those means of communication and the men who operated them. Vietnam is located squarely in the torrid zone. (Map 1) High temperatures prevail throughout the year, except in a few mountainous areas. The average annual temperature varies only a few degrees between Hue in the north (77°F) and Saigon in the south (81.5°F), with generally high humidity. The annual rainfall is heavy in all regions, torrential in some; it averages 128 inches at

[3]

MAP 1 - SOUTHWEST ASIA

[4]

Hue and about 80 inches at Saigon. These conditions had their effects on delicate electronic equipment and temperate zone troops.

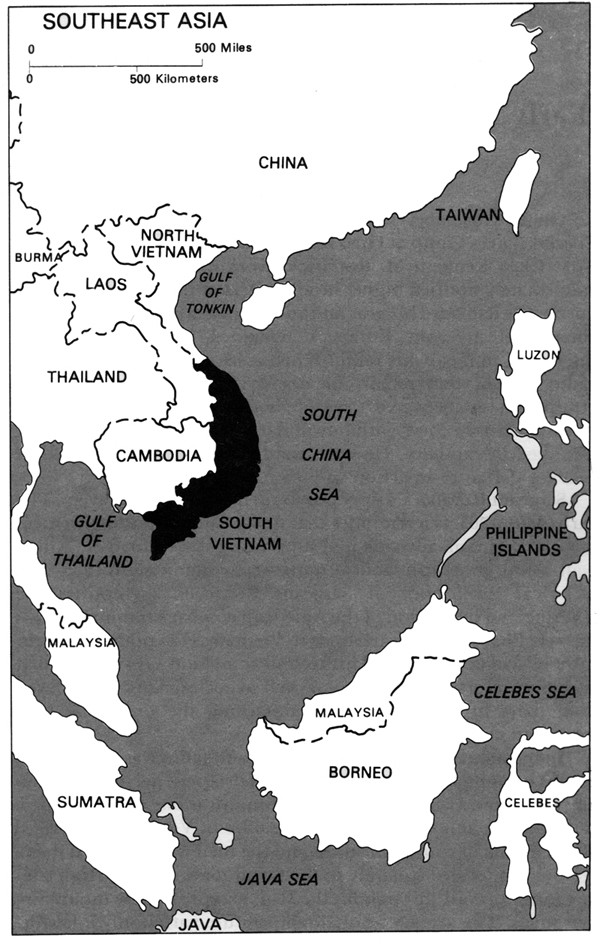

The Republic of Vietnam has three major regions: the Mekong Delta, the Highlands, and the Central Lowlands. (Map 2) The Mekong Delta comprises the southern two-fifths of the country. Its fertile alluvial plains, favored by heavy rainfall, make it one of the great rice-growing areas of the world to economists-and one of the world's largest mud-holes to troops trying to operate there. The delta is interlaced with a series of rivers consisting of the five branches of the Mekong, which total about 300 miles in length, and three smaller rivers: the Dong Nai, the Saigon, and the Vain Co Dong. This low, level plain is seldom more than ten feet above sea level, and, during the flood season, the only dry land to be found is generally that forming the banks of the rivers and canals. These levees and dikes, built for flood control, are used extensively as village sites. Despite its shortage of solid ground, the delta region is very heavily populated, with more than 2,000 people per square mile in some areas. The water network of rivers, streams, and canals; the flat, soft terrain; and the dense population influenced the nature of military operations that were undertaken to combat enemy forces there.

The Highlands (or the Chaine Annamitique) dominate the area of Vietnam northward from the Mekong Delta to the demarcation line. The Chaine Annamitique, with its several high plateaus, is an extension of the rugged mountains that originate in Tibet and China. The Chaine forms the border between the Republic of Vietnam and the Khmer Republic (Cambodia) to a point about fifty miles north of Saigon. This natural border is irregular in height and shape with numerous spurs dividing the coastal strip into a series of compartments that make north-south communications difficult. Included in the Chaine is a plateau region known as the Central Highlands that covers approximately 20,000 square miles. The northern part extends from Ban Me Thuot about 175 miles north to the Ngoc An peak. It varies in height from 600 to 1,600 feet with a few peaks rising much higher. This 5,400-squaremile area is covered mainly with bamboo and tropical broadleaf forests interspersed with farms and rubber plantations. The southern part of the Central Highlands is generally more than 3,000 feet above sea level and features broadleaf evergreen forests at the higher elevations and bamboo on the lower slopes. Monte Lang Vian, near the mountain resort city of Da Lat, is 7,380 feet high. This sparsely populated, rugged terrain of the Central Highlands was the scene for major action as American units and their allies

[5]

MAP 2 - GEOGRAPHIC REGIONS

[6]

tried to keep the enemy from moving men and materiel in force toward the Central Lowlands.

The Central Lowlands consist of a narrow coastal strip wedged between the slopes of the Chaine Annamitique to its west and the South China Sea to the east. The extensive cultivation of rice and other crops in this fertile region and an active fishing fleet support the heaviest population concentration other than that of the Saigon and delta regions. Numerous ports, airfields, and military bases were developed in the Central Lowlands to support U.S. military operations both there and in the Central Highlands. Quang Tri, Hue, Phu Bai, Da Nang, Chu Lai, Quang Ngai, Phu Cat, Qui Nhon, Tuy Hoa, Ninh Hoa, Nha Trang, Cam Ranh Bay, Phan Rang, and Phan Thiet are but a few of the Central Lowlands places which became familiar to U.S. soldiers and the news media.

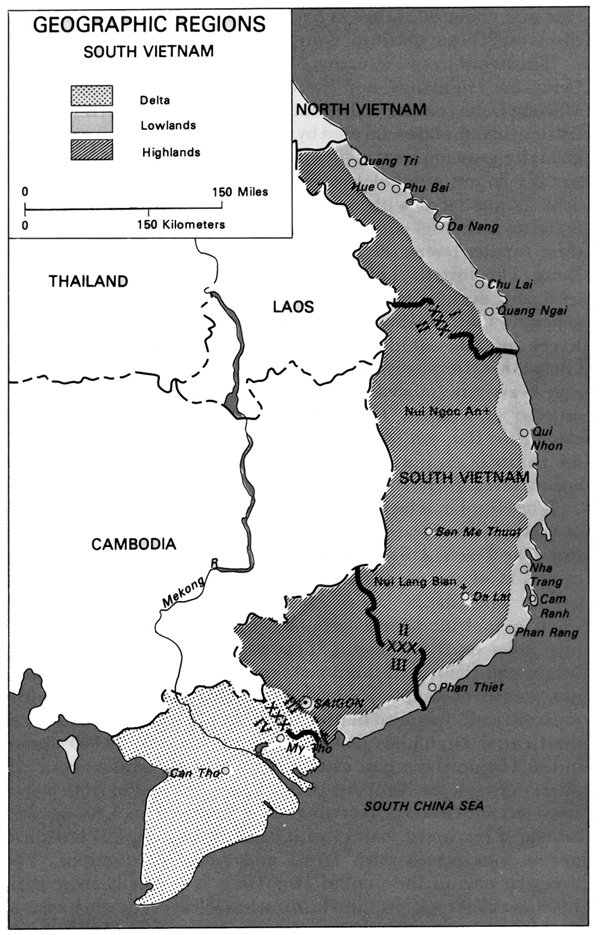

The land affected tactical communications in seven divisions, four separate brigades, and one armored cavalry regiment. (Map 3)

The commitment of major U.S. combat forces to Vietnam in 1965 followed a deepening American involvement which had begun in 1950. In 1960 Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem, faced with a rapidly deteriorating situation in the countryside, declared a state of all-out war against the Viet Cong and asked for increased American aid. In late 1961 President John F. Kennedy sanctioned the operational support of Vietnamese forces by American forces. Eight company-size aviation units, two specialty aviation detachments, and two maintenance support companies were deployed to Vietnam during the following twelve months. The size of the new deployments and the new mission made an increase in communications support imperative. The first unit of the U.S. Army ground forces to arrive in Vietnam was a communications unit, the 39th Signal Battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Lotus B. Blackwell. First contingents of the battalion arrived in Vietnam in February 1962; the complete battalion was there by July.

The battalion's first job was to establish and maintain a countrywide communications system to provide command and control for the new operational support and expanded advisory missions. Code-named BACK PORCH, a tropospheric scatter radio system extended the length of the country, from the demilitarized zone in the north to the Mekong Delta in the south, and marked the first time this type of "mountain hopping" equipment was used in a combat environment. The battalion also operated telephone exchanges and communications centers throughout the country to

[7]

MAP 3 - AMERICAN UNITS IN VIETNAM

[8]

RADIO TELEPHONE OPERATOR

tie the Military Assistance Advisory Group headquarters to essential subordinate organizations and Vietnamese agencies. Although much of this mission involved communications well above the division level, the 39th Signal Battalion was the pioneer for many divisional operations that followed.

An early assignment of the 39th was to help install a special radio net for the village defense forces. The net tying the units together employed the amplitude modulated radio set AN/ GRG-109 at several subordinate stations in each broad operational area, all controlled from a central headquarters in Saigon. Although the net control station remained open around the clock for emergency reception, normal radio contact was made only on a scheduled basis using international Morse code.

Within the operational areas, an internal communications system employed commercial amplitude modulated (AM) voice radios, TR-20's, with other interested agencies, subordinate operational bases, and selected villages. These lower nets worked twenty-four hours a day but with traffic controlled to save battery power and to permit emergency traffic. The net control station was generally either manned or monitored by American advisers; the village and other net radios were operated by trained local Vietnamese. Light manpack sets, which would have enabled roving patrols to tie into the village radio nets, were in short supply

[9]

at the time. According to one of the early advisers, Major Ron Shackleton, the old model AN/PRC-6 and AN/PRC-10 radios were tried but were too short ranging; they did see some limited use, however, by close-in observation teams and listening posts. Within operational bases, telephone wire was installed between defensive points and command posts.

Village defense radios had been installed largely as part of a special project sponsored by the United States Operations Mission, a component of the Agency for International Development. Chief Warrant Officer George R. McSparren and a team of twenty enlisted men from the 232d Signal Company, 39th Signal Battalion, worked on the project for about six months during 1962, but more help was needed. Then the 72d Signal Detachment (Provisional), consisting of seventy-two enlisted men under the command of Captain Robert A. Wiggins, was sent on temporary duty to Vietnam. It was attached to the 39th Signal Battalion during late 1962 and early 1963 to take over radio operations in the hamlets throughout the Republic of Vietnam. In five months the operation was well under way, and the unit was awarded the Meritorious Unit Citation for its efforts.

Another early communications assignment involved avionics, the application of electronics to aviation and astronautics. Much of the early operational support of the Vietnamese armed forces centered on airmobility, which placed the highest premium on good communications between aircraft, particularly helicopters, and between aircraft and ground. To ensure higher echelon avionics maintenance support for the aviation units, six signal detachments (avionics) arrived in Vietnam during 1962: the 69th, 70th, 255th, 256th, 257th, and 258th. These detachments filled a vital need in supporting the communications and electronics equipment of the aviation units already in Vietnam and of those that followed. This activity came under the signal officer of the United States Army Support Group, Vietnam, the component U.S. Army headquarters within the Military Assistance Advisory Group, who employed a qualified avionics officer to coordinate all avionics support activities. Although serious shortages of qualified personnel beset the program at the start, the problem was resolved and the avionics detachments became an invaluable part of the communications team.

As aviation support expanded and the enemy began to adjust his operations and tactics to counter the helicopter threat, heavier and more frequent ground fire was encountered both in the air and on landing zones, causing a marked increase in damaged and

[10]

destroyed aircraft. Aircraft and avionics mechanics and other available ground crewmen took turns riding "shotgun" at helicopter doorway positions to suppress the hostile fire. The practice had an inevitable ill effect on avionics and helicopter maintenance, and, in the fall of 1962, when the Military Assistance Advisory Group asked for help, a program was started to train men for specific duty as aerial door gunners. The 25th Infantry Division in Hawaii lent early assistance by providing specially trained volunteers on temporary duty as door gunners; they permitted avionics maintenance personnel to return to their specialties.

As the scope and complexity of American involvement increased, a need arose for an organization that could apply, test, and evaluate new methods and techniques (including communications) called for in the combat environment of counterinsurgency warfare. This led, in late 1962, to the establishment of the Army Concept Team in Vietnam under Brigadier General Edward L. Rowny. One of the team's earliest projects was generated by pleas from U.S. advisers for a better way to control and coordinate the communications means available to the South Vietnamese commanders they were assisting.

With the role of airmobility vastly expanding, command and control had assumed a new importance. Because the usual reaction to the hit-and-run tactics of the Viet Cong was a quick airmobile response, it demanded a helicopter command post from which the Vietnamese commander, together with his adviser and a limited staff, could get quickly to an area under attack, develop a plan of action, and commit reaction forces rapidly. That procedure often meant briefing the reaction forces en route to the objective, coordinating with other friendly forces, and husbanding additional support as needed; in short, using several radios at the same time. Trying to do that within the confines of a helicopter passenger compartment, where space, weight, and power were at a premium, was no small task. The commander and his staff had to compete with the high noise level in the cabin to talk to each other and to the crew members. They also needed some sort of work surface for map layouts and overlays.

An early attempt to meet these needs was made by lashing down three FM (frequency modulated) radios (AN/PRC-10) together in the passenger compartment and mounting the antennas at 45degree angles on the skids. Although such a "lash up" was used with some success, it was cumbersome and provided only FM channels when very high frequency and high frequency single sideband were also needed because of the extensive range and

[11]

variety of activities involved. The expedient also failed to provide for communications within the helicopter.

In early 1963, the Army Concept Team defined the requirements for an aerial command post for command control of ground and air operations and submitted a proposed evaluation plan. The plan was approved by the Commanding General of the U.S. Army Combat Developments Command and the U.S. Army Electronics Research and Development Agency at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, which dispatched a two-man team to Vietnam in August to determine how the Electronics Laboratory might assist. In the end, four command post communications system consoles for UH-1B helicopters were fabricated. Each. included an operations table and a compact five-position interphone system independent of the aircraft interphone but capable of entry into that system. Each console also provided equipment for two different frequency modulated radio channels, an independent very high frequency amplitude modulated radio circuit, a high frequency single sideband circuit, and access to the aircraft's ultra frequency amplitude modulated command radio-certainly a full spectrum of radio coverage to meet almost any contingency.

The first consoles arrived in Vietnam in December 1963 and were issued to the 145th Aviation Battalion and the Delta Aviation Battalion (Provisional) for evaluation. The battalions found the original design to be too ambitious. Because of the size and weight of the console, two single seats normally occupied by the aerial door gunners had to be removed, and the additional weight upset the helicopter's center of gravity. Nevertheless, when the map board and table were eliminated and the single sideband radio relocated, the console performed so well that in July 1964 the U.S. Military Assistance Command stated an urgent requirement for a heliborne command post (HCP) for each Vietnamese division and one each for the Vietnamese II, III, and IV Corps.

The console was ultimately designated the AN/ASC-6. The thirteen required, along with two for backup, were fabricated at the Lexington-Bluegrass Army Depot in Kentucky and rushed to Vietnam. They were tested from late 1964 to early 1965 and were successfully used in all sections of Vietnam from Da Nang in the north to Pleiku in the Central Highlands and the Mekong Delta in the south. Headed by Lieutenant Colonel Clarence H. Ellis, Jr., a five-man team conducting the evaluation included two communicators, Major Cecil E. Wroten and Captain Wilmer L. Preston. The test report commended the assistance of another communicator, Captain James A. Weatherman, and the Avionics Office of the U.S.

[12]

EARLY COMMAND COMMUNICATIONS CONSOLE with aircraft radios.

Army Support Command, Vietnam. Eighty-five more consoles of the AN /ASC-6 model would be obtained and deployed to Vietnam over the next four years.

Among conclusions noted in the test report was that standard aircraft radios and antennas were better suited for installation in the heliborne command post than were ground radios and antennas, a controversial conclusion that would arise again later. The report also noted that the command post functioned most effectively at altitudes between 1,500 and 2,500 feet, a compromise between observing activity on the ground and avoiding ground fire and other aircraft. In response to another conclusion that the command post had to be capable of longer flight time than troop transports or armed helicopters, a fifty-gallon auxiliary gas tank was placed in the space under the passenger seats.

The utility of the heliborne command post was so apparent that even as the test was going on, fifteen more were procured and placed in routine use. The heliborne command post, wrote Brigadier General John K. Boles, Jr., in forwarding the test report, " . . . is the single piece of new materiel which should have the most influence on improving the conduct of the war in Vietnam."

While those steps to improve airmobility operations were being taken in Vietnam, parallel efforts were under way at Fort Benning, Georgia. The 11th Air Assault Division was activated at Fort Benning on 15 February 1963 following recommendations made by a special board studying tactical mobility requirements, known as

[13]

EARLY COMMAND COMMUNICATIONS CONSOLE with VRC-12 series radios.

the Howze Board (its chief was Lieutenant General Hamilton H. Howze). This extraordinary division was given a high priority on personnel and equipment; it was tasked to develop new and radical airmobile concepts and operational procedures.

As an action officer working in combat development on the Department of Army staff, I had the good fortune to serve on a team that visited the 11 th Air Assault Division during this time. The division commander, Major General Harry W. O. Kinnard, invited our team to a Saturday morning "think tank" session, a weekly practice within the division. At these sessions commanders and staff kicked around ideas, no matter how far-fetched, that pertained to airmobile operations and improved command and control. Our team was deeply impressed to see an entire division dedicated to talking through and then trying out bold tactical airmobile concepts that were no more than vague ideas a few years before. From those sessions emerged much of the embryonic doctrine that later guided the redesignated 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) to its dramatic combat successes in Vietnam.

Communications in airmobile operations received considerable thought and attention. In early 1964, the division signal officer, Lieutenant Colonel Tom M. Nicholson, asked the U.S. Army Electronics Command for assistance in designing and fabricating an airborne tactical operations center to be installed in the UH-1 helicopter. In the process, when the question of air versus ground radios arose, the 11th Assault Division chose ground radios primarily for supply and maintenance reasons. Using the same

[14]

type of radios as used by ground maneuver units in the heliborne command consoles would permit rapid replacement of a damaged or inoperative radio at almost any supply point or battalion maintenance facility within the division area. It would also ease the problem of obtaining spare parts. There were also operational advantages over the aircraft radios in that ground radios were compatible and had a greater range because of their higher average power output.

The Communications Department of the U.S. Army Electronics Research and Development Laboratories at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, directed by Robert S. Boykin, received the project. Built to 11th Air Assault Division specifications, a model was delivered in March 1964 and installed with the assistance of a laboratory team. Following limited operational testing at Fort Benning, the model unit was returned to the laboratories in May with a list of proposed modifications. The unit was finally designated the Airborne Communications Control AN/ASC-5, and fifteen more were built for the division by Lexington-Bluegrass Army Depot. The AN/ASC-5 served its purpose well at that time but was later modified and redesignated the AN/ARC-122-.

[15]

|

Go to: |

|

|

Last Updated 3 October 2003