CHAPTER XII

The Training Base

If the military organizations are to survive for long on the field of battle, they must be constantly strengthened by trained men to replace those lost through rotation, promotion, sickness, or battle. Both in quantity and quality, the U.S. Army training establishment measured up to the Vietnam war expansion and the demand for trained replacements. To this end, many training courses had to be run on three shifts, around the clock. Skilled military instructors were assigned first to. the classroom, then to Vietnam, then to the classroom again. Many worked not only their full duty shifts but also added hours repairing equipment and doing other work which helped ensure that the training program would go on. At a number of communications training installations, civilian staff members and civilian instructors also played a crucial part in the herculean task of meeting the demands for trained technicians. Their corresponding stability, expertise, and dedication often made the difference between success and failure when the military staff was riddled by overseas levies. Together, the civilian and military teams got the job done.

Before the Vietnam war, training in the technical services such as the Signal Corps had been the responsibility of the chief of the service concerned. The chief signal officer had under his command the Signal Training Command at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, which directed all Signal Corps field training activities, including the Signal School at Fort Monmouth, the Signal Training Center at Fort Gordon, Georgia, and the Training Command Detachment at Fort Bliss, Texas. He also held responsibilities for signal research and development and for signal supply and procurement.

Shortly after assuming his duties in 1961, Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara directed a number of special studies aimed at improving management practices within the Department of Defense. One of these special studies was Project 80, "Study of the Functions, Organization and Procedures of the Department of the Army." The study was made by a hand-picked task force of military

[87]

men and civilians headed by deputy comptroller of the Army Leonard W. Hoelscher. The study began on 17 February 1961 upon the approval of the study plan by Army Chief of Staff General George H. Decker. As the Hoelscher committee neared completion of its report, representatives of the deputy chief of staff for logistics raised strong objections to some features. Brigadier General James M. Illig and Dr. Wilfred J. Garvin took particular exception to the technical service chiefs' losing their responsibilities for the technical training and career management of their personnel. They expressed the view that combat arms agencies such as the Continental Army Command and the Office of Personnel Operations could not produce the kind of skilled technicians required in an era of rapid technological change for service throughout the Army and Department of Defense.

The Hoelscher committee submitted its report in October 1961 and was disbanded except for a small residual staff. General Decker appointed a general staff committee under Lieutenant General David W. Traub, Comptroller of the Army, to study the Hoelscher committee report and recommend what actions the Army should take. The Traub committee supported the recommendation that technical training be transferred to the Continental Army Command.

Secretary McNamara pushed for action. At an 8 December 1961 meeting with the, Army technical services chief, he asked for their views on the broad aspects of the reorganization plan. Chief Signal Officer Major General Ralph T. Nelson concurred in the recommended changes.

On 16 January 1962, President Kennedy sent the reorganization recommendations of Secretary McNamara to Congress. Under the provisions of the McCormick-Curtis amendment to the Defense Reorganization Act of 1958, the proposals went into effect on 17 February 1962 when Congress failed to exercise its right to object within thirty days. Secretary McNamara pushed implementation. On 1 August 1962 the chief signal officer was placed under the general staff supervision of the deputy chief of staff for operations. The Signal Corps part of the reorganization was completed on 28 February 1964 when the chief signal officer was divested of his remaining field activities and was integrated into the staff of the deputy chief of staff for operations as Chief, Communications-Electronics, under the provisions of Department of the Army General Order 28.

The U.S. combat support phase of the Vietnam war began in late 1961 and the combat phase in mid-1965. Between these two

[88]

crucial dates, direct responsibility for the training of Signal Corps technicians was transferred from the chief signal officer to the commander of the Continental Army Command; the procurement and distribution of Signal Corps equipment was transferred from the chief signal officer to the commander of the new Army Materiel Command; and the responsibilities for training publications and technical publications were transferred to the new Combat Developments Command and Army Materiel Command, respectively.

Among the many schools run by the Continental Army Command were schools representing most of the branches of the Army with the exception of those schools in the medical, legal, and intelligence fields which were the responsibilities of the appropriate Department of the Army staff members. The schools most closely associated with divisional communications were the Southeastern Signal School at Fort Gordon, Georgia; the Signal School at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey; the Field Artillery School at Fort Sill, Oklahoma; the Armor School at Fort Knox, Kentucky; and the Infantry School at Fort Benning, Georgia. All others, including the higher level staff colleges and senior service schools, had an interest in the quality and utilization of the product but little part in its development.

The effectiveness of divisional communications depended heavily on the skills and dedication of the enlisted technicians who installed and manned the systems that carried the voice of command. The Southeastern Signal School at Fort Gordon generally taught most of those enlisted military occupational specialties that fell in the tactical area while the Signal School at Fort Monmouth taught the strategic and fixed stations skills. (See Appendix A.) Communications training also went on at a number of Army training centers. For example, training in military occupational specialty 05B, radio telephone operator, was conducted under the doctrinal monitorship or proponency of the Southeastern Signal School at Fort Dix, New Jersey; Fort Jackson, South Carolina; Fort Knox, Kentucky; Fort Huachuca, Arizona; and Fort Ord, California. Training in other heavy volume military occupational specialties was conducted under Southeastern Signal School proponency at Fort Polk, Louisiana; Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri; Fort Dix; Fort Jackson; Fort Huachuca; and Fort Ord.

When the Vietnam war began, an expanding Army increased its divisional requirements. The training load doubled. In 1962 the Southeastern Signal School graduated 16,643 tactical communicators; in 1967 it graduated 42,901. Wartime training under the

[89]

ground rules that were in effect became a mammoth task.

Some of those rules established for the Vietnam war were to have a distinct impact on the training establishment and differed from those existing in previous wars. Some of these ground rules were imposed on the Army and some were, at least partially, self-imposed.

In World War II, the draft period was "for the duration plus six months." For the Vietnam war, it was for two years. This ground rule for the Vietnam war further aggravated the training problem because the non-Regular Army personnel who developed experience in a combat tour did not have enough time left in the service to man other units or to act as instructors. Nor could a draftee be sent to a unit outside the combat area for any lengthy period of on-the-job seasoning after his school training and still have time left for a Vietnam tour. The training establishment had to train people to fill both requirements, combat and noncombat. The twelve-month Vietnam tour, coupled with the loss rate for all other causes, meant a heavy personnel turnover. This, in turn, meant a quantity requirement against the training establishment, especially when the Army was expanding rapidly to meet ever-rising strength levels in Vietnam.

Experienced communications personnel who could be used as instructors were in short supply. This understrength was further aggravated by a ground rule which authorized some instructors to be absent for half of each training day to attend civilian job training under Project Transition. This well-intentioned project was open to servicemen within six months of the expiration of their term of service and was designed to provide a more orderly transition into the civilian job market. The top priority task of training communicators for the battlefield was degraded by the loss of these experienced instructors. In 1968 the Southeastern Signal School estimated that over a hundred thousand hours had been lost to Project Transition at a time when such a loss could be ill afforded.

The presidential decision not to call up any significant number of reserve component elements or individuals posed a number of problems. The impact on the training establishment was felt primarily in the junior officer and noncommissioned officer areas. Both the instructor corps and the student support units needed more junior officers and noncommissioned officers of maturity and experience. The ground rules precluded looking to the reserve components for assistance.

Another problem was the lack of an adequate ground rule for the distribution of new equipment. For the training base to develop

[90]

operators and repairmen, it must get a proper portion of the early production of new items of equipment to use for training. All too often the training base had to fight tooth and nail for what should have been recognized as a normal requirement. Similarly, when new items of equipment come into the inventory to replace older models, the changeover frequently takes many years. Economic considerations concerning maintaining production lines, stretching out costs over a number of fiscal years, and getting the most for the dollar by using the old equipment longer in lower priority units have a degree of validity. In the training establishment, these ground rules frequently resulted in having to instruct on more than one generation of equipment at the same time or in instructing students on a generation of equipment different from that which their unit of assignment would have. In equipment changeover, the ground rules on timing were frequently governed more by fiscal considerations rather than by training and operational needs. Student deferment was another of the ground rules that affected the training base. The existence of a large college population meant that the input to the armed forces as a whole was not a true cross-section of the talent which could have been available. Subtract from the available input those volunteers accepted by the Air Force, the Navy, and the reserve components, and a quality problem starts to appear. In training technicians for the communications field, the quality of input matters.

The personnel system managers at Department of the Army level maintained a strong emphasis on limiting the number of military occupational specialties and related special skill or training identifiers. This policy led to problems, especially in the communications field. The training base would provide specialized training of individuals to meet battlefield requirements, only to have the individual end up in the wrong location. The personnel system could not identify the individuals well enough to get them to where the need existed. This difficulty was noted by the Continental Army Command Training Liaison Team which visited Vietnam in August-September 1967. Colonel Edward E. Moran, the signal representative on one of the early liaison teams, stated in his trip report that procedure was required whereby individuals who received specialized post-military occupational specialty functional training could be identified in Vietnam and be assigned to units requiring those specialized skills. Instances were noted where jobs requiring specialized training were filled by untrained personnel, while trained individuals were assigned elsewhere.

Shortly after the combat phase of the Vietnam war began, liai-

[91]

son between Continental Army Command schools and battlefield elements was established by a number of methods. One was visits by the training liaison teams. Colonel Moran's trip report stated that the purposes of his trip and its overall objectives were to establish a responsive system of feedback data from the field to responsible schools, determine the quality of and specific deficiencies found in school graduates, ascertain potential problem areas, and gather data which would be directly applicable to courses of instruction.

Liaison visits were as effective as the power of observation and analysis of the team members, the effort expended, and the cooperation of the host command. Colonel Moran's summary comments reflect the effectiveness of this early liaison visit.

Colonel Moran's team found that Continental Army Command Signal School graduates performed well in Vietnam. The speed with which they became fully effective on the job depended directly upon their training on specific equipment makes and models in use in Vietnam, the extent to which their training was systems oriented, and the length of time between completion of schooling and reporting to unit assignments in Vietnam. In the great majority of cases one week or less of on-the-job training was sufficient.

The types and items of equipment used in Vietnam in some cases had been phased out of school courses in favor of newer equipment. Colonel Moran recommended that older equipment be reinstated in pertinent courses until its use had been discontinued in Vietnam. In other instances, greater emphasis should have been placed on specific aspects of training to increase early effectiveness on the job.

Communications systems training should be emphasized, Colonel Moran found, and the requirement to fight as infantry as well as perform as technicians should be impressed upon the signal school student during training.

The team found signal units generally up to authorized personnel strength, although critical shortages existed in a number of specific military occupational specialties. In many instances, school graduates with post-military occupational specialty graduation functional training were not assigned to units requiring the training. Cable splicer, 36E, school graduates were not available on requisition. A course in Vietnam was necessary to fill this need.

In many instances, Colonel Moran found, slow supply response to emergency ("Red Ball") repair parts requisitions delayed the repair of critically needed communications equipment.

The team thought the U.S. Army, Vietnam, headquarters bimonthly publication, "Command Communications," established

[92]

in September 1966, was an effective organ for feedback on communications experience.

Certain revisions or changes in emphasis of school courses were indicated. For example, the fixed station technical controller, 32D, needed to be trained in specific facility control operations as performed in Vietnam. Particularly important were circuit standards, equipment interfacing, local operation procedures, restoring circuitry, and operation of the AN/MRQ-73. Communications center specialist, 72B, training required greater emphasis upon perforated tape reading, message transmission rather than reception, message format, and classified material accounting.

Another liaison channel was initiated on 22 August 1967 by Brigadier General William M. Van Harlingen when he wrote to Major General Walter B. Richardson, the commander of the U.S. Army Training Center and Fort Gordon. General Van Harlingen stated that since arriving in Vietnam he had felt a need for exchanging information with the Southeastern Signal Corps School, from his viewpoint both as the 1st Signal Brigade commander and as the assistant chief of staff for communications-electronics for U.S. Army, Vietnam. He had some unusual problems in training because of the environment and because of much new equipment being put to its first large-scale use. On both counts General Van Harlingen suggested an informal monthly information exchange with the school. General Richardson enthusiastically endorsed the recommendation.

As this liaison grew, detailed reports from the battle area came to the school and equally detailed replies returned. In a 13 October 1967 letter, General Van Harlingen discussed difficulties in maintaining the AN/GRC-106 radios. The deadline rate increased from 14.43 percent for the January-June period to 16.6 percent for the June-September period. A shortage of repair parts contributed to approximately 50 percent of that rate during the first period but to less than 5 percent in the second period. The shortage of qualified single sideband radio repairmen was most critical at that time. General Van Harlingen sent a technical assistance team from General Dynamics to the field to survey the training problem, give remedial operator and maintenance training, and observe repair shop procedure. The team would also give command staff orientation and evaluate the effectiveness of the new equipment training team and the utilization of repairmen trained by the team. He hoped also to receive an interim report on 1st Logistics Command repair facilities before 15 October and to include it in his next letter. In early September a member of General Van Harlingen's staff

[93]

attended a Distribution and Allocation Committee meeting at the office of the Army deputy chief of staff for logistics. At that meeting, representatives supported a recommendation to divert two hundred AN/GRC-106's plus a few AN/GRC-142's and 122's and AN/VSC-3's to Continental Army Command for immediate distribution to the schools. The hope was that this equipment would improve both operator and maintenance training.

In his reply on 26 October 1967, General Richardson indicated that the Signal School at Fort Gordon recognized the difficulty in maintaining the radio set AN/GRC-106. There was a high deadline rate for the training equipment; of the twenty-two sets on hand, only eleven were working. To compensate, Continental Army Command had allocated thirty more sets for the school from current production runs. This action supported his view that if the Signal School was to provide trained, qualified men for new equipment, it must receive its training allocation from early production runs.

In another letter on 15 May 1968, General Van Harlingen noted that a Continental Army Command liaison team had recently completed its quarterly visit to Vietnam. Colonel Theodore F. Schweitzer, the director of instruction at the U.S. Army Signal Center and School at Fort Monmouth, was the signal representative on the team. The team visited Military Assistance Command, his headquarters, each field force, five divisions, two separate infantry brigades, and the 1st Signal Brigade and several of its units throughout the command. Colonel Schweitzer met and discussed signal training with commanders, staffs, and enlisted communications specialists in all these organizations. He made the following general observations: Enlisted and officer students did not receive sufficient instruction on the Army Equipment Records System (TAERS). Students being trained on communications equipment normally mounted on a vehicle with a power generator as a part of the total package should receive training in 1st echelon maintenance of the vehicle, trailer, and power generator. Maintenance personnel in general were well trained in circuitry, in reading schematics, and in repairing equipment once the fault was found, but they should be better trained to identify and isolate trouble. There was a lag in receipt of trained operators and maintenance personnel for new equipment being introduced into Vietnam, but Southeast Asia Signal School was training selected cadre personnel from units already in the country. Carrier wave, Morse code, was not being used in any unit contacted, so continuing training in Morse code for the 05B and 05C should be studied to determine if it could

[94]

be eliminated. Communications officers (MOS 0200) were particularly well trained to perform the communications functions within the combat battalions, but they were also required in most cases to perform as duty officers in the battalion tactical operations centers and were not trained in that area.

Colonel Schweitzer found the most frequent complaint about newly arrived radio relay and carrier attendants (MOS 31M) was that their school training barely prepared them for the job in Vietnam. They were weak in knowledge of erecting and connecting the antenna; many indicated that training in antenna erection consisted of observing demonstrations. Personnel also needed training on the new AACOMS pulse code modulated (PCM) equipment and in the maintenance of the vehicles and generators associated with radio relay equipment.

Colonel Schweitzer noted several deficiencies in the training of radio teletypewriter operators (MOS 05C). Personnel arriving in Vietnam lacked knowledge in the fundamentals of HF operation. They were unfamiliar with space diversity operation, and their knowledge of antennas was generally poor. Most needed additional training on the KW-7 security equipment.

Colonel Schweitzer concluded that with these exceptions the training of communications personnel appeared to be satisfactory for operations in Vietnam. General Van Harlingen agreed with the observations and recommendations. This comprehensive report of the Continental Army Command liaison team was studied in depth at the Signal School. The school was already aware of a number of the problem areas and had made progress toward eliminating them.

Troubleshooting by maintenance personnel was considered the most important aspect of all maintenance training. The trend was toward less theory anti more training with the actual equipment to be used on the job. Evaluations during training were planned to determine any deficiencies. The lag in the arrival of operators and maintenance personnel trained for new equipment continued to be a problem and was constantly addressed by the school. Training on pulse code modulated equipment appeared to be the major area of concern. The school's main problem in this area was the lack or the late receipt of sufficient quantities of new equipment to conduct adequate training. As a part of the effort to do everything possible to relieve that problem and to provide the 31 M course the minimum equipment required, the school consolidated the PCM equipment available in that course.

Liaison by correspondence continued periodically for several

[95]

years. Further liaison came by way of senior members of the Signal Corps who spoke to graduating officer classes at the Southeastern Signal School. These occasions provided excellent opportunities for personal exchanges of views with the school staff on training problems related to tactical communications and frequently resulted in further discussions by correspondence.

Major General William B. Latta, commander of the U.S. Army Electronics Command, visited Fort Gordon as a graduation speaker and examined the training being conducted. He later indicated to Colonel Moran that training for the radio relay specialist, 31 M, was lacking in three respects. The, course was too short, even though it had been increased from twelve to fourteen weeks. Too much time was lost in the three-week training on pulse code modulated equipment and the losses from three-shift operation. The practical work was conducted on a parade ground and did not give the necessary training for field conditions. General Latta recommended a two-week period in the field. System training was a necessity for the radio relay specialist. On-the-job training was cited by General Latta as essential "to polish previously attained knowledge and skills." It was not acceptable to prepare men only as apprentices for further training in their units.

Many other means were used to make school training as relevant as possible. The rotation of enlisted instructors between combat duty and classroom duty provided realism. Incorporation of lessons learned and other operational reports from Vietnam into the training program was pushed. Exit interviews made by Vietnam veterans upon completing their tours were analyzed for their contribution. Major Clark Jonathan Bailey II, signal officer of the 11 th Armored Cavalry Regiment, pointed out in his interview that he, the regimental officers, and the noncommissioned officers all felt that the military occupational specialty training was not adequate. He specifically cited the radio mechanic/radio repairman, MOS 31B, and the radio teletypewriter operator, 05C. Men in these specialties were trained to repair components but they did not understand nor could they analyze communications systems. Major Bailey also noted that they did not seem to understand the basic principles of how to overcome adverse communications conditions and made little effort to correct problems before calling for a repairman.

Within the limitations of their funds, equipment, instructors, and facilities, the schools and training centers tried to respond to the field. One limitation on their ability to respond was a 10 percent restriction on changes in course content. Any greater change

[96]

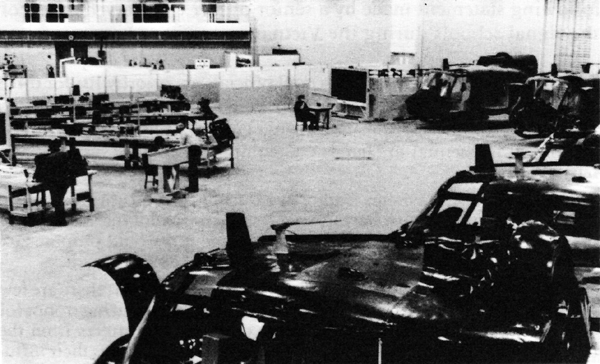

BRANT HALL, new home of avionics maintenance courses at Fort Gordon.

required Continental Army Command approval. The time required to process change requests and the questionable technical capability of the command to evaluate them provided difficulties for the schools. Another source of conflict in the repair field was with the Army Materiel Command over the adequacy and timeliness of technical manuals. Some of these difficulties could possibly be attributed to the newness of the responsibilities assigned by the Project 80 reorganization, but improvement in these areas remained a high priority from the viewpoint of the schools throughout the war.

On 12 September 1966, Continental Army Command issued a letter, "Policy Guidance-Electronics Training." This letter presented a training formula that applied primarily to the repair field. In this formula the available time (for enlistments and training) and the average aptitude of trainees were, for the moment, constants; the method of training was the only variable to manipulate. The letter went on to give specific Department of Defense guidance and objectives, but what it all added up to was a major challenge to the training establishments. Through the dedication of many individuals, the training establishment overcame limitations in the areas of equipment, personnel, facilities, and funds to meet and support the Vietnam war requirements.

One view of the lessons which should have been learned by the training establishment from these experiences is summed up in the

[97]

following statement made by a senior officer who served at one of the signal schools during the Vietnam war period:

From the viewpoint of a service school official, my priority list for three changes to improve on Vietnam War school experiences would be:

1. Higher Training Equipment Priority: Early and adequate issuance of equipment is essential to "hands on" equipment oriented operator and repair courses.

2. Greater Course Revision Authority: During time of war, the service school commandant must have greater responsibility for the adequacy of his instruction and greater authority to change it. I would propose 20% authority in course length and 40% authority in course content.

3. Higher Officer and Instruction Priority: In time of war, there are few stateside missions higher in real priority that of preparing troops for combat. Upon completing their combat duty, top performers from the combat zone must be brought back to the school system where their influence can be magnified.

[98]

|

Go to: |

|

Last Updated 3 October 2003