Appendix A

MAJOR GENERAL ROBERT

R. PLOGER'S BRIEFING OF

GENERAL WILLIAM C. WESTMORELAND, 4 NOVEMBER 1965

(Reproduced May 1971 from notes of the original briefing cards.)

General Westmoreland, General Norton, Gentlemen:

In the following briefing I shall cover four separate points. First of all I shall present an appraisal of the engineer situation as it appears for the United States Army, Vietnam. Second, I shall address some peculiar aspects of the engineer environment in South Vietnam. Third, I shall present the logical conclusions and follow with my recommendations.

First, then, a summary of the engineer situation. The mission of the engineers as I see it may be briefly stated as follows: Within allocated engineer resources, it is the mission of the engineer organization of the United States Army, Vietnam, to enhance and promote the capabilities of USARV to win in South Vietnam. This mission is performed through three distinct types of activities: First, by providing support to tactical operations; second, by constructing the required logistical facilities; and third, by making the environment amenable to our interests.

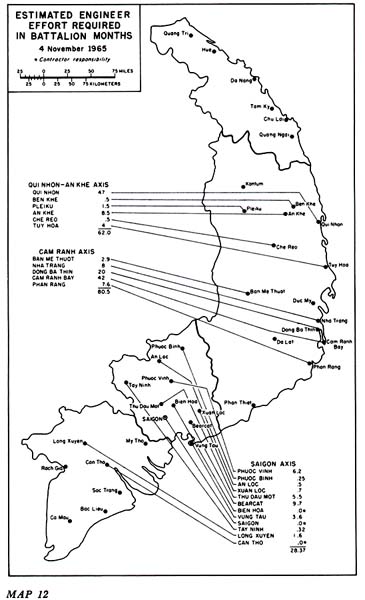

To determine the requirements, then to meet our mission, the first element calls for a certain amount of engineer support. This is an indefinable quantity; we are unable, at any given point in time by way of forecast, to determine precisely how much of the total available engineer effort must be allocated to the tactical situation. The second part of our mission, that of constructing logistical facilities, is more easily estimated. On this map is a presentation of our geographical distribution of engineer effort required for construction of facilities which currently have been identified as necessary. (Map 12) Note that in the Saigon axis area we have a total requirement of approximately 28.37 battalion-months of engineer effort. In the Cam Ranh Bay axis it is estimated that a total of 80.5 battalion-months of effort will be required and in the northern Qui Nhon-An Khe axis it appears that we require a total of 62 battalion-months of work. One battalion-month comprises the expected output of either one construction battalion or one combat battalion plus a light equipment company as applied against the already identified items in the construction program for fiscal years 1965 and

[199]

[200]

1966 already presented to Department of the Army. Thus, we have a total for the Army of 170 battalion-months of work ahead of us and please note that this omits any requirements for formal construction for the Air Force. A substantial portion of this total is devoted to cantonments and since our total engineer work load will be dependent on the standards that we accept for ourselves, I would like at this point to outline precisely what are the several standards for cantonments. First of all for a proposed cantonment area, Standard 1, there is merely an access road from the highway into a bivouac area. Standard 2 provides tentage without floors, cleared areas, and pit latrines. Standard 3 adds floors to all housing and provides fixed buildings with electricity for kitchens, administration, and showers. For Standard 4, all housing (still tents) and latrines are provided with electricity, a building is furnished for eating, an elementary water disposal system of sewer pipes leads from the kitchen and showers, and the surface of the access road is stabilized. Standard 5 provides for a bituminous road into the area from the main route and the addition of waterborne sewage facilities doing away with the latrines. The development is progressive from Standard 1 to Standard 5, Modified, for each cantonment area. (See Appendix B.)

Turning now to our capabilities, our present engineer strength incountry is in the order of 7,900 officers and men. Looked at another way this is equivalent to 8.4 battalions when the capabilities of our mix of engineer units is appropriately weighted. It is apparent then, that we have a total work load of 170 battalion-months with only 8 plus battalions, leaving a total time requirement of almost 2 years to accomplish all of the Army work if there is no commitment of engineer troops to the support of tactical operations. Obviously, with much to be done and little with which to do it, the question of priority must be addressed. The 18th Engineer Brigade headquarters has developed a proposed program of priorities. These are based upon the need of American troops to be able first, to fight; second, to move; and third, to maintain themselves. I call your attention to the listing of priorities for allocation of engineer troop effort and construction material, running from number one, clearing and grubbing of troop areas (largely an equipment effort), through field fortifications, clearing fields of fire, preparation of water supply points beyond the capabilities of tactical units, installation of LST ramps and bollards, on through to chapels, the final item listed. (See Appendix F.) I shall later request you to approve this priority listing for use throughout the Republic of Vietnam.

Let me now turn to some additional aspects of the engineer situation. With reference to equipment, I wish to raise two points. First of all, engineer effort is intimately tied to equipment which, in turn, is dependent on maintenance and the availability of spare parts. Without adequate spare parts support, our equipment becomes deadlined with a

[201]

resultant delay in accomplishing our mission. At this time, with a total of 1,218 pieces of construction equipment we have some 190 which have been deadlined for more than 7 days. We have been making and will continue to make strenuous efforts to overcome this problem. A second point with reference to equipment is that engineer equipment has good tactical flexibility but little strategic flexibility. That is to say, it is easy to move engineer equipment between local points over short distances-we can move them at a fast rate of speed. When long distance movement is required the major items of equipment must be packed, and since they are heavy and bulky, transport is difficult and time-consuming. This is particularly true in South Vietnam where it is impossible to move by road between the several axes of effort, from Saigon, for example, to Qui Nhon or Cam Ranh Bay. It is a major effort to prepare such things as earthmoving scrapers, rockcrushers, or float bridge trucks for movement by water between two ports, as from a location in the south of Vietnam to the central area or farther north. Thus, it becomes important to predetermine the best initial location of equipment as it arrives from the United States in order to insure that it is most effectively used over a long time.

The next major matter of concern to all engineers is that of construction material. Some 25 million dollars of building materials have been ordered. They have not yet been delivered. We are faced then with universal shortages in all areas. Local materials are almost nonexistent. Possible exceptions are lumber, rock, and sand, although each of these requires major effort to get the material into a usable form. There is little available lumber which is not required for use in the local economy. I estimate that we require a total of 325 thousand tons of materials for accomplishment of the fiscal year 1965 and 1966 construction program. As is borne out by past experience in previous wars, about 15 percent of a total theater tonnage will be required for delivery of construction materials. Translated into terms of shipping this means that one out of every seven ships arriving at South Vietnam should be loaded with construction materials.

Like major items of engineer construction equipment, engineer materials are highly immobile, difficult to move, and this immobility creates a serious handicap. To avoid multiple handling, careful scheduling must be observed in determining how much of each shipload should be off-loaded at each port.

An additional serious problem marks your engineer construction operations in South Vietnam. A fundamental difference exists between operations in this theater and those in the normal theater. Previously, construction supplies at the time of their departure from the United States were considered as expended. Accountability for them in terms of cost was discontinued. They were treated as operational materials

[202]

just like ammunition. In this theater we find that construction materials are not expendable. We must account for how they are used and where they are used. We have an approach to this problem which will allow full accountability of Military Construction, Army, funds and still insure that funds will not dictate supply levels. I call the approach the limited war construction accountability program and I will be prepared to brief you on this subject at a later time if you wish. So much for the engineer picture in South Vietnam.

Let me now turn to the engineer environment. In a physical sense our engineers will be operating in tightly confined spaces . . . carefully limited in the area in which they operate. Within this area they are faced with serious problems of drainage. In general, engineers from the United States are not acquainted with the tremendous quantities of rainfall typical of tropical climates. We find also a very high water table, particularly in the southern regions, as for example in the delta, which create construction problems for foundations. Also, our lines of communication are highly vulnerable to disruption not only by enemy action but also by severe monsoon rains. With a high rate of water runoff the numerous bridges and culverts will require substantial engineer effort to retain them in operation. With reference to political environment we find some new circumstances. We are faced with the necessity to obtain real estate through governmental operations before we may begin building. Since the operation of normal economics has absorbed all prime real estate, we may expect any well-drained land or that which has been farmed will generally be denied to our troops and to construction for all elements of the Army. We shall be expected to do our building on land which is ill-suited for construction. A Public Works Ministry has responsibility for road work throughout the country. It has little capability and yet we must conduct careful liaison on our works in connection with the road system. In another area, looking to the long range future, the addition of systems of waterborne sewage will require easements for passing through private land from our construction sites to the nearest waterways. Here once more we have a requirement for close coordination with the governmental authorities of our host nation. In the economic realm we find a very small work force of any competence in construction skills as we know them. And resources even to meet the needs of local people are totally inadequate. With the influx of large numbers of Americans in recent months our soldiers have proceeded individually to buy in the local market construction materials such as lumber, nails, cement and the like. The result has been a startling inflation. Aggregate, that is, broken-up stone which the Vietnamese provide largely by hammer and individual "elbowgrease" has increased in price by 135 percent in the last 90 days. Nails have increased in cost 35 percent. Lumber prices today are double what

[203]

they were 3 months ago. Even the military environment is unusual from an engineer point of view. Military requirements for base construction include such things as floodlights for security with the intent of lighting up the battlefield at night instead of seeking to camouflage or hide our installations. This prospect promises to introduce new requirements for electric power. We must coordinate our activities with the Army of South Vietnam and its activities. The intermixing of our respective organizations promises to complicate our operations. We find our operations and requirements seem to be unrelated to our capabilities. There are cries from all directions for engineer assistance, and yet, as I pointed out, we are severely constrained in our ability to respond. Your own military commanders have great expectations of what they wish to receive in the way of engineer support. One major installation commander has informed me that he expects his base to be developed to the equivalent of Fort Benning before he will be satisfied. Every commander expects early delivery of materials, money, and allocation of any available effort and yet we find inadequacies in all of these areas. The inescapable conclusion is that engineer operations for the foreseeable future will be a continuous allocation of shortages. Nonetheless, we shall attack our problems with vigor and seek to provide assistance where it will most benefit your mission. I have the following recommendations: First, I request that you approve the priorities as they have been presented here today. Second, I request you to emphasize to all commanders that they must lower their expectations at least for the near future. For my part, I shall seek to inform them of our capabilities and lend all possible assistance. Third, I ask your support in encouraging your commanders to do as much cantonment construction as possible through self-help on a gradual scale of upgrading rather than relying entirely on engineers. I would propose that for the present we set Standard 4 as our objective in our cantonment construction. This concludes my briefing.

(NB: At the conclusion of the meeting, after the briefing by General Ploger, Engineer, United States Army, Vietnam, General Westmoreland approved the priorities as presented and accepted the principle of gradual upgrading to Standard 4 as an initial objective.)

[204]

Return to the Table of Contents