Map 1

CHAPTER I

The growing American commitment to the preservation of the Republic of Vietnam found its most dramatic manifestation in 1965 in the rapid manpower buildup carried out by the US Army. The expanding involvement of the Army Engineer forces was more a reaction to the growing US strength in Vietnam than the execution of a precisely drawn plan. From the time the first large contingent of Army engineer troops waded ashore at Cam Ranh Bay in June 1965, the demands upon the engineers were so immediate and overwhelming that their initial mission appeared impossible. At Cam Ranh the sand, the heat, tropical rains, and the incessant calls for engineer assistance all contributed to a discouraging situation, but the engineer troops there, as elsewhere in South Vietnam, were to establish themselves rapidly as formidable challengers of the impossible. In an amazingly short time they would change the face of a country, win the admiration and respect of those who depended upon them so heavily for support and facilities, and contribute substantially to the defense of the republic.

Beginning of the Troop Buildup

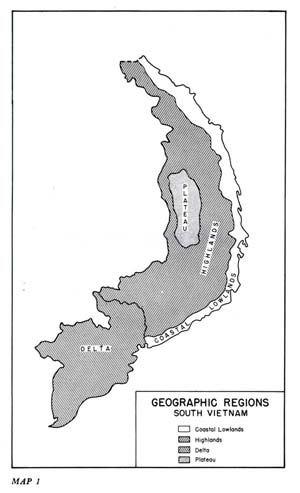

In January 1965 it was obvious that North Vietnam's immediate objective was a full-scale offensive aimed at cutting South Vietnam in two and capturing the local and district centers of government. If successful such a move would place the Saigon government in jeopardy and might give Hanoi its long-sought total victory. The United States responded to the urgency of the situation by deploying forces to the extent necessary to thwart any hopes Hanoi might entertain for an easy and immediate victory in the south.

The United States military commitment in South Vietnam in January 1965 consisted of about 23,000 men of whom fewer than a hundred were Army engineer troops. This force, the United States Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), consisted of a substantial number of US advisers with South Vietnamese units, Army and Marine Corps helicopter units with their necessary logistic support, the 5th US Special Forces Group, seven Air Force squadrons, a Navy headquarters command in Saigon, and an office

[3]

of the Navy's Bureau of Yards and Docks whose function it was to supervise civilian contractor construction support to the various US military elements in Vietnam. The civilian contractors alone, however, could not be expected to cope with a dangerously deteriorating military situation and the rapid influx of US Army forces.

Initial deployment of US ground combat forces took place in early March of 1965 when marines of the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade, later redesignated the III Marine Amphibious Force, landed at Da Nang and took up defensive positions in the very vulnerable northern provinces of South Vietnam. The 173d Airborne Brigade was airlifted from Okinawa to Bien Hoa on 5 May to relieve South Vietnamese Army forces of some of their security responsibilities and to free them for missions designed to search out and destroy threatening forces. With the growth in tactical responsibilities of US forces in 1965, more combat and logistical support units became necessary.

Late in 1964 General William C. Westmoreland as the senior US commander in South Vietnam had recommended to the US Joint Chiefs of Staff the deployment of an Army Engineer group and a logistical command to South Vietnam. Although the need for a sound logistical base and more extensive US support facilities was foreseen as early as 1962, resources for them had not been provided at the time. The Joint Chiefs approved General Westmoreland's request, noting that a "military capability was needed to supplement that of the construction contractor and to respond to a critical need for military engineers to accomplish work unsuitable for the contractor." On 15 January 1965 the request was forwarded to Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara, who turned it down after a task force visited South Vietnam in February. Instead, he approved deployment to Vietnam of 38 logistical planners and 37 operating personnel. General Westmoreland had requested 3,800 logistical troops and 2,400 engineers.

The director of the Pacific division of the Bureau of Yards and Docks, a naval officer, had stated that the contractor's "mobilization and rate of construction accomplishment can and will be promptly expanded as required by further program expansion." At that time, however, the potential extent of "further program expansion" was unknown. It was soon to become all too apparent that a critical gap with regard to engineer resources existed in contingency planning for the buildup of US forces.

Early planning for the buildup and operations in Vietnam had little more to go on than tentative indications of the number of maneuver battalions that might be deployed. There was no generally accepted tactical concept, campaign plan, or scheme of logistic sup-

[4]

The most immediate consideration in any construction planning is the selection of the site, its preparation, and its development. Next, material and manpower requirements have to be studied with respect to the type of facilities to be constructed. Methods and particular techniques to be employed in construction are determined. Various options in design are considered and the choice is made on the basis of utility and materials available. Most important of all, requests have to be fed into supply channels to insure timely and sequential delivery of construction materials to the site in order that the project can be completed within the time allotted. The size and scope of the initial engineer work load in South Vietnam caused inevitable shortcuts in the planning process at various levels resulting in equally inevitable delays and complications in execution.

Convincing the Department of the Army staff, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Department of Defense officials that engineering requirements had expanded was made more difficult by the normal tendency of these organizations to wait for the statements of requirements sent in by the overseas commanders. These commanders, however, were ill prepared to make such crash estimates because they lacked enough qualified staff engineers. Indicative of the problem was the fact that the US Army Support Command, Vietnam, the predecessor of both the 1st Logistical Command and Headquarters, US Army, Vietnam, had only a very small number of engineers in the country. The assigned engineers had been committed primarily for maintenance of facilities in support of the advisory groups and for minor construction projects for the Army aviation units that were already engaged in supporting South Vietnamese forces.

The engineers in Vietnam worked hard to assemble a reasonably valid Army base development plan and construction program before the arrival of the first major engineer contingents. But force levels, tactical concepts, and stationing plans were so tenuous that precise long-range planning was impossible. Only through ingenuity and a

[5]

good bit of scrounging were some materials made available to the first engineer units to arrive in Vietnam.

Expansion of the Training Base

Throughout the spring and early summer of 1965 it was generally assumed both within the Department of the Army staff and at Headquarters, United States Continental Army Command, that any augmentation of the Army force structure would include at least a partial call-up of Reserve component units and men. As late as 22 July 1965 in a briefing to a conference of selected Army commanders, Major General Michael S. Davison, Acting Assistant Chief of Staff for Force Development, reported that on 16 July the Department of the Army had received tentative guidance which authorized an increase of 350,000 in the strength of the Army by the end of fiscal year 1966 (30 June 1967). Of this number, 100,000 spaces were to be filled by members of Reserve components.

Contingency plans for a manpower buildup in the Department of the Army contained the proposed call-up of Reserve components and men for a period not to exceed twelve months. Based upon experience gained during a partial mobilization in 1961, Continental Army Command plans had called for an even larger twoyear activation of Reserve component units. Experience had shown that Reserve units could be readied for deployment overseas much more quickly than could reorganized or newly activated units in the active Army. It was the contention of Continental Army Command that approximately seven months lead time was required to prepare Reserve units for relief from active duty, and that so much lead time tended to defeat the effectiveness of an activation of only twelve months. Policies set at higher levels, however, prohibited Reserve call-ups of a duration greater than one year, and consequently Continental Army Command's plan could not be supported.

In any event all such plans were rendered useless on 28 July 1965. On that date in a nationally televised press conference, President Lyndon B. Johnson announced plans for the buildup of US forces in South Vietnam. US combat forces in Vietnam would be increased immediately to 125,000 men, with additional forces to be deployed as necessary. This increase was to be accomplished, the President went on to say, through expansion of the active Army by increased draft calls, but no Reserve units or individuals were to be called up.

Since major planning policies for expanded US activity in, Southeast Asia had been based on the now fallacious assumption that a significant proportion of the necessary manpower would come

[6]

[7]

from Reserve components, the stage was set for shortages not only of units but also of men with technical training and managerial ability. In the understandable desire to maximize its readiness to fight, the Army tries to retain a high proportion of combat formations in its active forces in peacetime. The cost is always a shortage of ready-to-go support units, including engineers. Major General Thomas J. Hayes III described the situation when he observed that "supporting units seem to bear more than their share of losses as a Nation progressively reduces its Armed Forces in the years between wars." After the Korean War many military activities were turned over to civilians in the United States and the military establishment became more and more dependent on the Reserves for the majority of Army combat support units as well as technicians required for wartime operations.

Suddenly deprived of their anticipated reservoir of trained and skilled manpower, the services in varying degrees experienced difficulty in meeting initial and subsequent requirements for logistic and combat support troops and units. The Army was hit hardest of all. Its strength requirements increased rapidly, and with already critical deficiencies in the support units the decision not to mobilize the Reserves or to allow selective call-up of experienced men led the Army to draw necessary men from other theaters. New units were later activated in the United States and soon after sent to South Vietnam; the peak of the engineer buildup was reached in January of 1968. (Map 2, Charts 1 and 2)

Since nearly half the Army's engineers and engineer equipment rested with Reserve components, equipment in the early stages of expansion had to be gathered from Reserve units all over the country to outfit fully those Regular Army units alerted for Vietnam. Crash training programs, intensive recruitment of civil service employees, reduction of stateside and European tours of duty, and volunteer programs were initiated to help fill immediate manpower needs. When these programs failed to meet the demands, the Army began to place officers of its other branches on detail in the Corps of Engineers.

The Army had to expand its training base to provide the troops necessary to meet Vietnam deployment schedules as well as to satisfy the worldwide requirements for individual replacements in accordance with the Army's rotational overseas service policy. The US Continental Army Command had the responsibility for shipping entire units as well as individual replacements to Vietnam and at the same time maintaining an adequate strategic Army force and training base in the United States.

The Continental Army Command's principal centers for engi-

[8]

CHART

1-LOCATION OF ENGINEER UNITS IN THE UNITED STATES,

JANUARY 1965

| Fort Belvoir, Virginia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Fort Benning, Georgia |

|

|

|

|

| Fort Bliss, Texas |

|

|

|

|

[9]

CHART 1-LOCATION

OF ENGINEER UNITS IN THE UNITED STATES,

JANUARY 1965-Continued

| Fort Bragg, North Carolina |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Fort Campbell, Kentucky |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Fort Carson, Colorado |

|

| Columbus Army Depot, Ohio |

|

|

| Fort Devens, Massachusetts |

|

|

|

| Fort Dix, New Jersey |

|

| Fort Gordon, Georgia |

|

[10]

CHART 1-LOCATION

OF ENGINEER UNITS IN THE UNITED STATES,

JANUARY 1965-Continued

| Granite City Army Depot, Illinois |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Fort Hood, Texas |

|

|

|

|

|

| Fort Knox, Kentucky |

|

| Fort Lee, Virginia |

|

|

|

|

|

| Fort Lewis, Washington |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Loring Air Force Base, Maine |

|

| Fort Meade, Maryland |

|

| Fort Ord, California |

|

| Fort Polk, Louisiana |

|

|

| Presidio of San Francisco, California |

|

[11]

CHART 1-LOCATION

OF ENGINEER UNITS IN THE UNITED STATES,

JANUARY 1965-Continued

| Fort Riley, Kansas |

|

|

|

| Fort Rucker, Alabama |

|

| Fort Sill, Oklahoma |

|

| Fort Stewart, Georgia |

|

| Fort Story, Virginia |

|

|

|

| West Point, New York |

|

|

| Fort Wolters, Texas |

|

| Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHART

2-ENGINEER UNITS ON ACTIVE DUTY, CONTINENTAL UNITED

STATES, JULY 1965

| Engineer Group Headquarters |

|

|

|

| Combat Engineer |

|

|

|

[12]

CHART 2-ENGINEER

UNITS ON ACTIVE DUTY, CONTINENTAL UNITED

STATES, JULY 1965-Continued

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Construction Engineer |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Float Bridge |

|

|

|

|

|

| Panel Bridge |

|

|

|

|

| Light Equipment |

|

|

[13]

CHART 2-ENGINEER

UNITS ON ACTIVE DUTY, CONTINENTAL UNITED

STATES, JULY 1965-Continued

|

|

| Construction Support |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Map Depot |

|

| Base Photo Map |

|

| Engineer Utility |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Engineer Dump Truck |

|

| Engineer Pipeline |

|

| Water Transport |

|

|

| Well Drilling |

|

|

|

|

| Engineer Heavy Maintenance2 |

|

| Engineer Maintenance and Support Group Headquarters |

|

| Direct Support Maintenance |

|

|

[14]

CHART

2-ENGINEER UNITS ON ACTIVE DUTY, CONTINENTAL UNITED

STATES, JULY 1965-Continued

|

|

|

|

|

| Field Maintenance |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Special Equipment Maintenance |

|

|

|

|

| Depot |

|

| Amphibious |

|

|

|

| General Support |

|

|

|

| Parts |

|

|

| Firefighting |

|

|

| Forestry |

|

|

| Water Purification |

|

|

|

[15]

CHART 2-ENGINEER

UNITS ON ACTIVE DUTY, CONTINENTAL UNITED

STATES, JULY 1965-Continued

| Port Construction |

|

|

| Water Tank |

|

|

|

|

| Gas Generator |

|

|

|

Carbon Dioxide Generator |

|

| Topographic |

|

|

|

| Base Survey |

|

| Reproduction Base |

|

| Geodetic Survey |

|

| Terrain |

|

| Technical Intelligence Research |

|

|

|

1 Deployed to South Vietnam before January 1968.

2 The functions of engineer equipment maintenance were reassigned by the Army to Ordnance Corps carrier units in 1965. Consequently few engineer maintenance units were sent to South Vietnam. Most provided personnel fillers and were soon inactivated.

neer training were Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, and Fort Belvoir, Virginia. Like other Army training centers, their operations and training programs had been greatly curtailed during the years after Korea. Now their facilities would again undergo a tremendous expansion within a very short time. It is a tribute to the command's flexibility and responsiveness that the manpower crisis was met; the 235,000-man increase in Army strength had been absorbed by Continental Army Command by 20 June 1966.

Within the Army engineer troop structure, the major problems in the expansion of US efforts in South Vietnam arose from shortages of men, equipment, and materials. The proportion of Engineer

[16]

units in the active Army before the buildup promised to be woefully inadequate. In a situation in which most equipment had to be bought through a time-consuming procedure of competitive procurement, availability of equipment was the deciding factor not only in the activation of new units within the continental United States but also in establishing dates for unit readiness. Since there were critical shortages of technically trained officers and certain enlisted specialists such as equipment operators and maintenance men, new recruits in steadily rising numbers were funneled into the advanced individual training facilities at Forts Leonard Wood and Belvoir to be schooled in basic engineering skills.

When increased draft calls and a related jump in enlistments raised the number of men to be trained beyond the capacity of the existing training base, new programs had to be instituted. To bring units to full strength as soon as possible as well as to relieve some of the stress on normal training facilities, Strategic Army Forces units were assigned some of the responsibility for training recruits under what was known as the "train and retain as permanent party" system. Under this program a specialized unit could train men to fill particular positions in the unit with the prospect of keeping them to alleviate its own shortages. Because of the diversity of engineer training, however, this program was of limited usefulness in bringing engineer units to full capability, particularly in the face of equipment shortages within units as they underwent training. The relatively slow rate at which new men could be trained and made available through established training bases presented a particularly acute problem to new diverse engineer units demanding a high degree of technical expertise. (Table 1)

A most serious problem was the shortage among enlisted men of qualified noncommissioned officers. Throughout the process of recruit training, stress was placed on the development of leadership qualities as well as technical proficiency. Those individuals who demonstrated talent for leadership were singled out early in their training cycles and given opportunities to qualify for advancement to positions of greater responsibility through assignment to a noncommissioned officer academy or an officer candidate school. Since there was a critical need to develop noncommissioned officers rapidly and continuously, academies were organized to produce competent noncoms in much the same way as the officer candidate schools produced second lieutenants. Forts Leonard Wood and Belvoir conducted courses designed to instruct new noncommissioned officers in leadership principles and to improve their technical proficiency before they were sent to Vietnam. Some of these men became of further value to the Army by returning from serviceTABLE 1-ENGINEER OFFICER AND ENLISTED SPECIAL SKILLS REQUIRED AND AVAILABLE IN NONDIVISIONAL UNITS IN SOUTH VIETNAM, JANUARY 1968

Engineer Officer Requirements, US Army, Vietnam

|

Grade |

Required |

Operational |

|---|---|---|

|

Colonel |

29 |

26 |

|

Lieutenant Colonel |

119 |

110 |

|

Major |

253 |

186 |

|

Captain |

755 |

278 |

|

Lieutenant |

1,056 |

1,247 |

|

Warrant Officer |

141 |

107 |

|

Total |

2,353 |

1,954 |

Engineer Enlisted

Military Occupational Specialties (MOS)

US Army, Vietnam

|

MOs |

Title |

Authorized |

Operational |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

12A10a |

Pioneer |

2,281 |

4,078 |

|||

|

12B20 |

Combat Engineer |

3,465 |

2,754 |

|||

|

12B2N |

Combat Engineer |

0 |

13 |

|||

|

12B30 |

Combat Engineer |

939 |

534 |

|||

|

12B40 |

Combat Engineer |

1,739 |

1,085 |

|||

|

12B4N |

Combat Engineer |

0 |

34 |

|||

|

12B50 |

Combat Engineer |

27 |

19 |

|||

|

12C20 |

Bridge Specialist |

835 |

656 |

|||

|

12C30 |

Bridge Specialist |

0 |

24 |

|||

|

12C40 |

Bridge Specialist |

220 |

207 |

|||

|

12C50 |

Bridge Specialist. |

1 |

1 |

|||

|

12D40 |

Combat Engineer Operations and Intelligence NCO |

24 |

12 |

|||

|

12D50 |

Combat Engineer Operations and Intelligence NCO |

4 |

3 |

|||

[18]

Engineer Enlisted

Military Occupational Specialties (MOs)

US Army, Vietnam-Continued

| MOs | Title | Authorized | Operational |

|---|---|---|---|

|

12Z50 |

Combat Engineer Senior Sergeant |

157 |

139 |

|

51A10a |

Construction and Utilities Specialist |

837 |

416 |

|

51B20a |

Carpenter |

1,588 |

1,999 |

|

51C20 |

Structures Specialist |

158 |

63 |

|

51C30 |

Structures Specialist |

111 |

55 |

|

51D20 |

Mason |

187 |

147 |

|

51E20 |

Camouflage Specialist |

0 |

4 |

|

51E40 |

Camouflage Specialist |

2 |

1 |

|

51F20 |

Pipeline Specialist |

56 |

30 |

|

51F40 |

Pipeline Specialist |

66 |

26 |

|

51F50 |

Pipeline Specialist |

7 |

1 |

|

51G20 |

Soils Analyst |

63 |

56 |

|

51H40 |

Construction Foreman |

557 |

380 |

|

51H50 |

Construction Foreman |

125 |

109 |

|

51H20 |

Heating and Ventilation Specialist |

21 |

12 |

|

51F30 |

Heating and Ventilation Specialist |

16 |

10 |

|

51K20 |

Plumber |

653 |

462 |

|

51L20a |

Refrigeration Specialist |

199 |

199 |

|

51M20 |

Firefighter |

378 |

338 |

|

51M40 |

Firefighter |

114 |

61 |

|

51N20a |

Water Supply Specialist |

464 |

497 |

|

51N40 |

Water Supply Specialist |

103 |

73 |

|

51N50 |

Water Supply Specialist |

1 |

0 |

|

51020 |

Utilities Foreman |

74 |

82 |

|

51P40 |

Terrain Analyst |

34 |

17 |

|

52A10 |

Powerman |

404 |

79 |

|

52B20a |

Power Operator and Mechanic |

938 |

1,004 |

|

52B30 |

Power Operator and Mechanic |

404 |

222 |

|

52C20 |

Power Pack Specialist |

77 |

15 |

|

52D20 |

Power Generator Repairman |

242 |

134 |

|

52D40 |

Power Generator Repairman |

22 |

22 |

[19]

TABLE 1-ENGINEER OFFICER AND ENLISTED SPECIAL SKILLS REQUIRED AND AVAILABLE IN NONDIVISIONAL UNITS IN SOUTH VIETNAM, JANUARY 1968-Continued

Engineer Enlisted

Military Occupational Specialties (MOs)

US Army, Vietnam

|

MOs |

Title |

Authorized |

Operational |

|---|---|---|---|

|

52E20 |

Power Station Operator |

20 |

8 |

|

52E40 |

Power Station Operator |

6 |

7 |

|

52F20 |

Electrician |

698 |

479 |

|

52G20 |

High Voltage Electrician |

0 |

2 |

|

53B20 |

Oxygen and Acetylene Production Specialist |

75 |

45 |

|

53B40 |

Oxygen and Acetylene Production Specialist |

3 |

0 |

|

53C20 |

Carbon Dioxide Production Specialist |

14 |

5 |

|

53C40 |

Carbon Dioxide Production Specialist |

6 |

0 |

|

62A10 |

Engineer Equipment Assistant |

1,543 |

838 |

|

62B10a |

Engineer Equipment Repairman |

1,313 |

1,773 |

|

62B30 |

Engineer Equipment Repairman |

686 |

838 |

|

62B40 |

Engineer Equipment Repairman |

42 |

41 |

|

62C20 |

Engineer Missile Equipment Specialist |

8 |

50 |

|

62C30 |

Engineer Missile Equipment Specialist |

10 |

13 |

|

62C40 |

Engineer Missile Equipment Specialist |

7 |

13 |

|

62D20a |

Surfacing Equipment Specialist |

347 |

395 |

|

62D40 |

Surfacing Equipment Specialist |

40 |

30 |

|

62E20a |

Construction Machine Operator |

3,915 |

4,715 |

|

62E30 |

Construction Machine Operator |

596 |

284 |

|

62E40 |

Construction Machine Operator |

460 |

452 |

|

62E50 |

Construction Machine Operator |

30 |

12 |

|

62F20a |

Crane Shovel Operator |

131 |

604 |

|

62F30 |

Crane Shovel Operator |

813 |

394 |

|

62G20a |

Quarryman |

396 |

421 |

[20]

Engineer Enlisted

Military Occupational Specialties (MOs)

US Army, Vietnam-Continued

|

MOs |

Title |

Authorized |

Operational |

|---|---|---|---|

|

62G30 |

Quarryman |

566 |

21 |

|

62G40 |

Quarryman |

27 |

29 |

|

81A10 |

General Draftsman |

158 |

113 |

|

81B20a |

Construction Draftsman |

186 |

231 |

|

81B40 |

Construction Draftsman |

6 |

6 |

|

81C20a |

Cartographic Draftsman |

80 |

66 |

|

81C40 |

Cartographic Draftsman |

7 |

3 |

|

81C50 |

Cartographic Draftsman |

4 |

2 |

|

81D20a |

Map Compiler |

6 |

7 |

|

81D30 |

Map Compiler |

12 |

4 |

|

81D40 |

Map Compiler |

6 |

5 |

|

81F20 |

Illustrator |

23 |

41 |

|

81F40 |

Model Maker |

0 |

3 |

|

82A10 |

Rodman and Tapeman |

117 |

10 |

|

82A20 |

Construction Surveyor |

142 |

178 |

|

82B40 |

Construction Surveyor |

22 |

9 |

|

82D20a |

Topographic Surveyor |

24 |

38 |

|

82D40 |

Topographic Surveyor |

8 |

7 |

|

82E20 |

Topographic Computer |

14 |

16 |

|

82E40 |

Topographic Computer |

2 |

3 |

|

Total |

30,162 |

28,284 |

|

a Military occupational specialties for which advanced individual training was provided during 1965-1970.

[21]

CHART 3-GRADUATES

OF OFFICER CANDIDATE SCHOOL AT FORT BELVOIR,

CUMULATIVE OUTPUT, 1966-1971

in Vietnam and teaching new recruits, but many at the conclusion of two years of draft service took with them to civilian life their Army-developed skills and experience.

The expansion of the officer candidate school system provides one of the more easily chronicled examples of the race between requirements and resources in the period of troop buildup. In the spring of 1965 the dearth of junior engineer officers was even more critical than that of noncommissioned officers. In response to this urgent need for new leadership talent, the Engineer Officer Candidate School at Fort Belvoir was reactivated in the fall of 1965. The

[22]

first class began on 15 November, and by 30 June 1966, 1,132 junior engineer officer graduates had been commissioned. The number climbed steadily and when the school at Fort Belvoir closed on 1 January 1971 it had graduated a total of 10,380 second lieutenants, not all of whom entered the Corps of Engineers. (Chart 3)

Because the engineers lacked the manpower base in the active Army at the beginning of the troop buildup and because the facilities for engineer recruit training were largely limited to two posts, units going to South Vietnam during the first year of the buildup proved short of engineer experience and skills. But the engineers' reputation for resourcefulness and determination which became their trademark in Vietnam had its beginning in their preparations for deployment. The professional Engineer Corps commanders at all levels continuously strove to bring newly activated or reorganized units to an acceptable degree of readiness in spite of compressed training times and frequently in the face of understrength cadres and equipment shortages.

The first contingent of US Army engineers in Vietnam faced the challenge of developing a base of support activities in a combat zone with a logistical backup consisting of a single source of supplies at a distance of nine to twelve thousand miles across the Pacific Ocean. When the decision was made in 1965 to expand the role of the United States in the defense of the Republic of Vietnam, it was apparent at once that a large complex of airfields, roads, ports, pipelines, storage facilities, and cantonments to support tactical operations would be needed. And soon after he arrived in South Vietnam the engineer soldier-enlisted man or officer-realized that he was essential to the total effort. His sense of purpose and his ability to improvise with whatever materials could be scraped together quickly made him indispensable.

[23]

Go To:

Return to the Table of Contents