Chapter VI:

Service Support in Vietnam:

Transportation and Maintenance

Service support described in the next three chapters include the transportation, maintenance, construction, facilities engineering, real estate, communications and aviation elements logistics. Also service support includes food service, graves registration, laundry, bath and property disposal activities. There is also a brief discussion of other support missions unique to the Vietnam war.

Staggering amounts of supplies of all types (construction, maintenance, communication, aviation, transportation, and personal items for the soldier) traveled along extensive sea and air routes across the Pacific to Vietnam ports, into depots and storage areas, finally down primitive roads and an almost non-existent rail network to supply points where they were finally delivered to the individual soldier or unit.

Service support followed the same trail and to meet the challenge service support units also had to institute special management techniques.

Between 1965 and 1969 over 22 million short tons of dry cargo and over 14 million short tons of bulk petroleum were transported to Vietnam. In addition to the cargo there was also the requirement for transporting personnel. Approximately 2.2 million people were transported to Vietnam and approximately 1.7 million were returned to the U.S. during this period. All the petroleum and more than 95 percent of the dry cargo were transported by ship. The remainder of the dry cargo and 90 percent of the passengers travelled by air.

Because of the similarities in military and commercial transportation operations, the transportation corps had a good base of professional knowledge to draw upon. For the most part, transportation personnel sent to Vietnam, both officers and enlisted personnel, had been in the business before.

[157]

Transportation Buildup-1965-1966

This period was characterized by a rapid increase in combat troop strength and the tremendous influx of supplies and equipment for their support. The transportation units that arrived during the May to August 1965 period were company and detachment sized-units which were stationed along the coast.

They were occupied primarily with their mission performance, their daily existence, security, and improvement of their cantonment areas. The 11th Transportation Battalion (terminal) arrived in Saigon on 5 August 1965 to assume control of the Saigon military port from the U.S. Navy. Two days later, the 394th Transportation Battalion (terminal) arrived at Qui Nhon to assume command of transportation units in that area and plan for the September arrival of the 1st Cavalry Division at An Khe. On 23 September, the 10th Transportation Battalion (terminal) arrived at Cam Ranh Bay to assume responsibility for the Cam Ranh Bay terminal.

The 4th Transportation Command (terminal Command) was the first senior transportation command and control unit to arrive in Vietnam. It arrived on 12 August 1965 and was given technical and operational control of all land and water transportation units assigned to the 1st Logistical Command. Included in this mission were the operation of the Saigon port, the water terminals at Cam Ranh Bay, Qui Nhon, Phan Rang, Nha Trang and Vung Tau, and operation of the Army Air Terminal at Tan Son Nhut.

Transportation Expansion-1966-1969

By early 1966, the Saigon, Qui Nhon, and Cam Ranh Bay Support Commands were established. Each was given responsibility for complete logistic support within its area of operation. This included the control and operation of all common user land transportation and port and beach facilities within the area. The Saigon area was an exception with the 4th Transportation Command retaining responsibility for port operations under the operational control of the Commanding General, 1st Logistical Command. The 4th Transportation Command was thereby relieved of its South Vietnam-wide transportation command mission, and concentrated on the Saigon Port proper. Although the 4th was not organized or manned to perform a theater level transportation command mission, the Command had done the job well. To assist the support commands in managing port operations, the 5th Transportation Command (terminal A) was assigned to Qui Nhon

[158]

Support Command, and the 124th Transportation Terminal Command (terminal A) was assigned to Cam Ranh Bay in August 1966.

Movement Control Within South Vietnam

Until September 1965 no co-ordinated movement control agency existed in South Vietnam. Air transportation was managed at the local level by individual Air Traffic Coordinating Offices located at the various aerial ports. Water transport requirements were sent directly to the Military Sea Transport Service, Far East. Highway transport needs were met by local support elements. As a result of such localized, decentralized traffic management, transport resources were either wasted or ineffectually employed and management data were not exchanged. There was no overall knowledge of the capability of country-wide transportation facilities.

In September 1965, Commander U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, established a jointly staffed Traffic Management Agency under his operational control and the staff supervision of the J-4. The agency became fully operational in early 1966 and was assigned the mission to: 1. direct, control and supervise all functions incident to the efficient and economical use of freight and passenger transportation service required for movement of all Department of Defense sponsored personnel and cargo within the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, area of responsibility (this was later expanded to include U.S. Agency for International Development requirements) ; 2. serve as a point of contact for all users of military highway, railway, inland waterway, intra-coastal and troop carrier and cargo airlift capability as made available by the component commander; 3. arrange for movement; 4. advise and assist shippers and receivers to insure that such transport capability is effectively utilized; 5. prepare and maintain current plans in support of contingency plans and prepare other Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, plans as directed; 6. operate Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, Traffic Coordination Offices; 7. control movement of cargo and passengers into terminals through coordination with terminal operators; 8. maintain liaison with transport agencies of the host nation, host nation military organizations and appropriate U.S. Forces required to accomplish the assigned mission; 9. and control, manage and maintain the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, container express operation.

The mission letter established the principle of centralized direction and control of traffic management and related services

[159]

at Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, headquarters and decentralized traffic operations, services, and co-ordination at field offices operating in support of the component commands. It authorized the Commander, Traffic Management Agency, to communicate directly with the component commands, their units, installations, and activities concerning requirements, traffic management, and use of military owned transportation, with responsiveness to the requirements of each of the components as the guiding principle. Originally Traffic Management Agency was organized with a directorate staff and three traffic regions. To meet changing requirements, two additional traffic regions were established in 1968. The total strength of Traffic Management Agency in July 1968 was approximately 400 personnel. The regional headquarters, with their district and field traffic offices, as well as the Air Traffic Co-ordinating Offices were located adjacent to major shipping and receiving activities and provided a point of direct contact for all transportation users and operators. The Traffic Management Agency command communications network operated over dedicated circuits that connected headquarters with the regional headquarters-and each region to its subordinate district and field traffic offices.

Since its inception, Traffic Management Agency was authorized to coordinate directly with numerous agencies outside the specific Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, area of responsibility. The Traffic Management Agency was collocated with the Military Sea Transportation Service Office, Saigon, and was authorized direct communication with both Commanding Officer Military Sea Transportation Service, and Commanding Officer Military Sea Transportation Service, Far East. To co-ordinate and obtain sealift capabilities to support tactical operations, which could not be supported by available resources, Traffic Management Agency was authorized to communicate directly with the Commander, U.S. Seventh Fleet. The Air Transportation Coordination Offices representing all of the Services requested inter-theater airlift allocations from Military Airlift Command. For intra-theater airlift beyond the capability of Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, assets, Traffic Management Agency requested assistance through the Western Pacific Transportation Office. Traffic Management Agency provided cargo booking guidance to Western Pacific Transportation Office for inter-Pacific Command surface movements to Vietnam ports and also coordinated with the Pacific Command Movements Priority Agency regarding surface shipments from Continental U.S. to Vietnam.

[160]

A significant point in the concept of Traffic Management Agency operations was that it did not exercise operational control of the transportation assets made available for common-user service. Rather, Traffic Management Agency operated on the basis of managing toward the optimum use of these assets. Forecasts of requirements were received from the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, component commands, U.S. Agency for International Development, Vietnam Regional Exchange Service, Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces, and other authorized users. These requirements were matched against available common-user transportation capability, based on priorities of movement established by the shippers. If requirements exceeded the capabilities, Traffic Management Agency inititated action to obtain the additional capability. If additional lift capability was not available, Traffic Management Agency would allocate the existing capability based on the policies, guidance, and priorities of Commander U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam.

The effectiveness of Traffic Management Agency improved as the theater situation stabilized, procedures were refined, operational problems were recognized, and solutions were developed. The lack of a centralized traffic management agency in South Vietnam during the early stages of the conflict contributed to an inefficient use of transportation resources. Movement control agencies proved to be highly effective in providing support to the tactical commander after the movement control agencies were implemented. Interface problems between Traffic Management Agency and the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, components continued to exist. Rather than invalidate the system, these problems highlighted the need for an agency like Traffic Management Agency.

Truck Transportation

During the deployment of tactical units in mid-1965 most highway transport units were located at or near the major port areas. They provided port and beach clearance and local and line haul in II and III Corps.

These services were initially provided by three truck companies at Saigon and Cam Ranh Bay and a combination of medium truck companies (two cargo and one Petroleum, Oils, and Lubricants) at Qui Nhon. These capabilities were increased through 1966 by the addition of more truck companies and command and control elements.

As force levels climbed, the requirements for highway trans-

[161]

portation units also increased. These requirements were met by three means: 1. the arrival of a Transportation Motor Transport Group Headquarters in Saigon plus the arrival of additional military truck units; 2. the use of commercial trucking contractors; and 3. the arrival of the 1st Transportation Company (GOER) in II Corps.

The 48th Transportation Group (Motor Transport) was the first truck group to arrive in South Vietnam and was assigned to the U.S. Army Support Command, Saigon in May 1966 to assume command of five truck companies then operating in III Corps. The 8th Transportation Group (Motor Transport) arrived at Qui Nhon in October 1966 and assumed command and control of the motor transport units in U.S. Army Support Command, Qui Nhon. The last truck group to arrive was the 500th Transportation Group (Motor Transport) which was assigned to the U.S. Army Support Command, Cam Ranh Bay in late October 1966. It was assigned responsibility for motor transport operations in the southern portion of II Corps.

In the summer of 1966 large scale combat operations in the Central Highlands put a severe strain on the motor transport units providing line haul support in the Pleiku area. Convoy commanders were required to continually operate over an insecure highway system. Convoy security support was provided by U.S. and Vietnamese units when priorities permitted; often the desired degree of support was not available. It was also desirable to have armored personnel carriers integrated into the convoy, but they were not always available. For this reason truck units employed the "hardened vehicle" concept (discussed in Chapter II). Within the 8th Transportation Group during the 1967-1968 time frame, the equivalent of one light truck company's capability was lost by converting their cargo vehicles to "hardened vehicles" to provide the necessary security.

Except in port and beach clearance and for local haul within secure areas, truck units operated only during daylight hours, thus achieving less productive tonnage than stated in Tables of Organization and Equipment which envision a 20 hour, two shift work day. Productivity was complicated by the unimproved roads which were made impassable by the monsoon rains. In September 1966, the GOER vehicle was introduced into Vietnam. The 1st Transportation Company (GOER) was the only company which utilized this vehicle. Total vehicles (GOER) assigned to the 1st Transportation Company (GOER) were 19. There were three configurations of the vehicle, the 8 ton vehicle, 8 ton 2,500 gallon

[162]

tanker, and the 10 ton wrecker. The GOER vehicle was a large tire, rough terrain, cargo carrying vehicle built and designed by the Caterpillar Tractor Company. The vehicles were quite versatile, having a cross country and swim capability. These vehicles were used extensively, but especially during the monsoon period. The GOERS were limited in their use, particularly on hard surface roads, and maintenance was difficult as repair parts had to come directly from Continental U.S. The service they performed was noteworthy in its effect on the transportation system.

The highway tonnages moved by a combination of military and commercial motor transport during the period December 1967-December 1968 was approximately ten million tons; and by the same means during the period January-July 1969, approximately five million tons were carried.

As the buildup continued it became apparent that the conventional military truck was not designed to handle palletized and containerized loads efficiently. The fixed sides of the cargo bodies on the 21/2-ton and 5-ton cargo trucks did not permit forklifts to reach the full length of the cargo compartment, therefore the push and pull method was used in loading and unloading operations causing damage to the truck bodies.

To facilitate operations, U.S. Army Vietnam obtained eighteen drop side cargo trucks from the U.S. Marine Corps to serve as test vehicles. The test proved that dropside trucks were highly desirable and effective cargo carriers and that through their use more cargo could be hauled with easier access to the entire length of the body and with little damage to the truck body. U.S. Army Vietnam requested that Department of the Army procure these trucks for use in Vietnam.

By the end of 1965, it was apparent to transportation planners that augmentation of military motor transport capability was necessary to clear the South Vietnamese port congestion. During the period March 1966-June 1966, the US Army Procurement Agency, Vietnam, awarded 10 major contracts for trucking services to augment the military capability. One of the major contractors used in Vietnam was the Vinnel Corporation which also provided stevedore support, beach and port clearance, and vessel maintenance support. The highway support offered by Vinnel included the operation of 30 Army-procured Kenworth trucks and trailers of the type and design used in the Arabian Desert. This vehicle was probably the most effective vehicle on the sand dunes of Cam Ranh Bay.

[163]

The three major trucking contractors used in the Saigon area were Equipment Inc., Philco Ford, and Do Thi Nuong. The Han Jin Company of Korea was utilized for trucking and stevedore services in the Qui Nhon area. The Alaskan Barge and Transport Company provided stevedore, trucking, and intra-coastal barge movement. Their intra-coastal operation utilized a considerable tug and barge fleet between Cam Ranh Bay and its outports. This intra-coastal barge movement included the entire South Vietnamese coast.

The use of contractor services for trucking, terminal, and marine purposes provided the extra punch needed in these operations, and provisions should be made to include in future planning consideration for use of contractors when the opportunity arises.

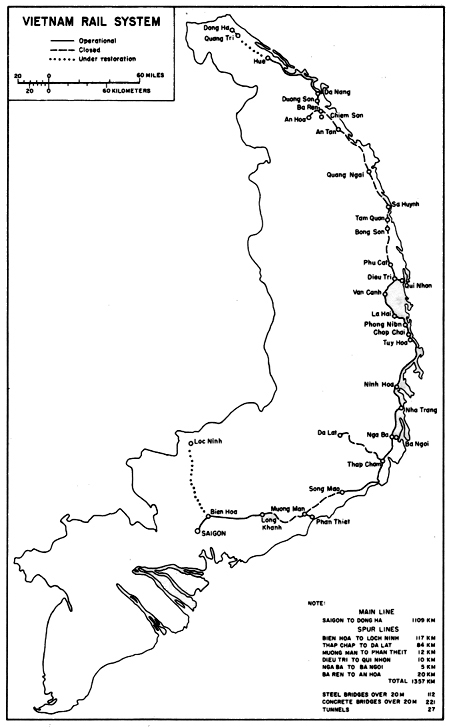

Rail Transportation

The Vietnam National Railway System was government owned, being operated under the supervision of the Ministry of Communications and Transportation. The Vietnam National Railway System originated at Saigon, and served the entire coastal area from Phan Thiet to Dong Ha. (Map 4) The overall condition of the roadbed and rolling stock was poor. The long period of intense interdiction and destruction by the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese regular units resulted in the railway system being unable to carry significant tonnages. The railroad was well engineered, however, with 413 bridges, 27 tunnels, controlling grades of less than 1½ percent, steel ties, and vertical elevations well above the waterways. In 1969, the rolling stock of the railroad consisted of 59 serviceable locomotives and over 500 serviceable freight cars. The major repair facility located in Saigon was well equipped to perform major engine and car repair. Other shop facilities along the length of the line were adequate to handle all types of minor repairs. The railroad employs approximately 3,500 personnel (operating crews, maintenance and construction forces) . Overall planning for railway restoration began in June 1966 as a joint effort by the Government of Vietnam and U.S. agencies. All reconstruction efforts were coordinated through three standing committees composed of members of Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, Government of Vietnam, U.S. Agency for International Development, and the Government of Vietnam Joint General Staff with primary responsibility for railway restoration resting with the joint Committee on railroad restoration. Actual construction was the responsibility of the Vietnam National Railway System except that rail spurs to U.S. military installations were

[164]

[165]

funded and built by US forces. U.S. Agency for International Development furnished construction materials such as rail, ties, structured steel, bridge trusses, and equipment. Funds programed for railway restoration were limited as shown in the following table:

PROGRAMING FOR RAILWAY RESTORATION

($ MILLIONS)

| Year | Government of Vietnam | U.S. AID | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1966 | $ .8 | --- | $ .8 |

| 1967 | 2.3 | $ 9.2 | 11.5 |

| 1968 | 2.6 | 3.1 | 5.7 |

| 1969 | 2.5 | 4.5 | 7.0 |

| Totals | $ 8.2 | 16.8 | $ 25.0 |

The U.S. Army had considerable interest in this railroad because of the potential it offered in the bulk movement of cargo at low rates. The system was used to support the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, construction program and transported hundreds of thousands of tons of rock and gravel to air base and highway sites. In 1967-1968, 200 U.S. procured freight cars were delivered. These cars were maintained and operated by the railroad for the U.S., and the freight rate for cargo handled on these cars was approximately 15 percent lower than normal rail rates.

Vietnamese personnel operated the engines, did their own repair work, and restored sections of track destroyed by the Viet Cong. To help the Vietnamese keep up to date, the U.S. Army assigned technical advisors to the railroad, but for the most part, the Vietnamese ran the whole operation.

Railway operations in Vietnam expanded in direct proportion to the interest and effort put forth by the U.S. And the Government of Vietnam. Besides providing low cost military transportation, railways helped the South Vietnamese in their social and economic development.

Air Transportation

Restrictions on land transportation placed added importance and reliance on intra-theater air transportation. The virtually nonexistent capability of the South Vietnamese Air Force air transport placed major reliance on U.S. air transport resources to support military operations. The main U.S. capability was provided by the Common Service Airlift System operated by the U.S. Air Force, and aircraft organic to the various military organizations.

[166]

The Common Service Airlift System was composed of fixed wing aircraft and provided tactical as well as intra-theater airlift. Organic aircraft were primarily employed by combat commanders for immediate battlefield mobility and support and were not readily available for intra-theater airlift purposes. Helicopters were not assigned to the Common Service Airlift System fleet, however they played an extensive and highly significant role which is discussed in some detail later in this chapter. The helicopter provided a highly versatile lift capability that had never been available in such great numbers in previous military operations. Use of the helicopter complemented the capability of the fixed wing aircraft and surface capability by operation from airfields and other areas to locations inaccessible to other forms of transport.

Initially the Common Service Airlift System was composed of U.S. Air Force C-123 and the C-7A aircraft of the Royal Australian Air Force and the U.S. Army. This fleet was augmented by U.S. Air Force C-130 aircraft in April 1965. The Common Service Airlift System organization further changed in January 1967 when the Chief of Staff, U.S. Army, and Chief of Staff, U.S. Air Force agreed that the C-7A aircraft assigned to the U.S. Army would be transferred to the U.S. Air Force.

Water Transportation

During the buildup phase, the few land lines of communication were in poor repair and subject to interdiction by enemy forces, and the mobility of U.S. Forces was achieved through the extensive use of water and air transportation.

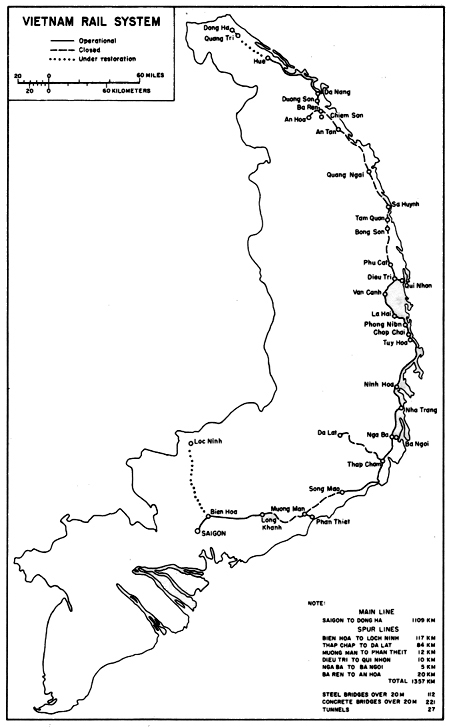

To fully exploit the potential of the long South Vietnamese coastline, and to supplement improvements in South Vietnam's four major deep water ports, a series of satellite shallow-draft ports were developed. (Map 5) The improvements permitted intra-coastal shipping to increase tonnages between 1965-1968 from several hundred tons to over three million tons.

Ports were rapidly expanded through the use of DeLong piers. These piers were quite versatile and were fabricated in a variety of sizes and configurations ranging from 55 feet to 427 feet long and 45 feet to 90 feet wide. They were towed from their ports of origin and quickly implaced at their destination. The DeLong pier is a good concept and a good facility, and should be included in future contingency plan packages.

Although the development of the four major deep draft ports was important to the support of forces in Vietnam, the use of numerous shallow draft ports and special operations, such as

[167]

[168]

Wunder Beach (Than My Thuy) were vital to the support of troops in such areas as I and IV Corps. Wunder Beach (Than My Thuy) in I Corps was a Logistics-Over-The-Shore type operation which was useful during the dry season. This beach operation allowed shallow draft vessels to unload directly on the beach without the use of piers and was an effective and efficient means of discharging cargo. The support of shallow draft operations required the use and coordination of the Military Sea Transportation Service, the Seventh Fleet LSTs in the Western Pacific, and the U. S. Army watercraft resources.

The U. S. Army Beach Discharge Lighter LTC John U. D. Page, which was made available for use in South Vietnamese waters after repeated requests and much delay, was useful in supporting intra-coastal requirements within the Cam Ranh Bay logistics complex (Nha Trang-Cam Ranh-Phan Rang). Control of the operation of this craft was retained at the Cam Ranh Bay Support Command. Because of its shallow draft and unrestricted loading ramp area, it was more versatile and valuable than an LST on a ship-for-ship basis. Although a prototype and unique in the Army inventory since the late 1950's, this craft has justified its additional procurement for the purpose of modernizing and increasing the versatility of the shallow draft fleet. This ship moved an average of 10,000 to 15,000 short tons per month. Her propulsion system was damaged in 1967, but demand for the ship's services delayed its movement to a shipyard in Japan for overhaul until almost a year later.

Early in the Vietnam buildup Landing Craft, Mechanized (LCM) and Landing Craft, Utility (LCU), were used to perform ship-to-shore and selective discharge operations and for limited intercoastal and inland waterway operations. These craft were supported in the lighterage role by amphibians of the LARC V (5 ton) and LARC LX (60 ton) (formerly known as BARC) classes. As deep draft piers were developed, some of these craft were diverted to other missions, such as the Wunder Beach operation, where no port facilities existed.

Due to the periodic shortage of tugs in the Saigon area, LCMs were frequently used to tow ammunition barges from the in-stream deep draft discharge sites at Nha Be and later at Cat Lai, to barge discharge sites dispersed throughout the area.

In northern I Corps, LCMs were used on the Perfume and Cua Viet Rivers to shuttle dry cargo and petroleum, oils, and lubricants from coastal transfer sites to Hue and Dong Ha.

In addition to their normal lighterage use, LCMs were em-

[169]

ployed in performing a variety of harbor service functions such as resupply, maintenance, ferry service, and patrol and were also used in direct support of tactical operations.

As the capacity of deep draft piers improved, both the Army's and the Navy's LCUs were shifted to intra-coastal and inlandwater ways. The use of LCUs accounted for approximately 29 percent of the total cargo moved intra-coastally during that year. Prior to the completion of the LST ramps at Tan My, Navy LCUs, with periodic Army support, were the primary media for resupply to northern I Corps. Extensive use of LCUs was also made for operations in the Saigon-Vung Tau-Delta complex. In late 1967 six SKILAKs, commercial off-the-shelf LCU/YFU type craft, were procured by the Navy to support operations in I Corps.

To help alleviate the shortage of lighterage and coastal shipping capability, Commander U. S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, recommended that a contract be negotiated with Alaska Barge and Transport Company. The concept of utilizing civilian contractors was approved by the Secretary of Defense in November 1965 and he directed the Military Sea Transportation Service to negotiate the contract. By 8 December the contract was signed and operations began in early 1966. This intra-coastal augmentation included a barge-tug fleet among which were two stripped down LST hulls for use as barges.

Because only one major port, Cam Ranh Bay, had a deep draft pier for the discharge of ammunition, a large number of the available barges were used to support the ammunition discharge program. The ammunition discharge in the Saigon-Cat Lai (Nha Be) complex, for example, was in effect a combination stream discharge and inland waterway distribution system and placed a heavy requirement on the available barge assets. In each major port complex, contractor-furnished lighterage augmented the limited military capability that was available.

A new requirement was announced in 1967 to move a minimum of 85,000 short tons per month of crushed rock into the Delta to support the highway rehabilitation program. This program increased the shallow draft barge and tug requirements and necessitated expansion of the contract support provided by Alaska Barge and Transport and another company, the Luzon Stevedoring Company.

A number of LSTs were being utilized for carrying cargo from Far Eastern Pacific ports to South Vietnam. To relieve pressure on LST assets and in order to make more shallow-draft shipping available in South Vietnam, the Commanding Officer, Military Sea

[170]

Transportation Service, Far East procured small foreign flag ships and retained some of the Continental U.S. -to-South Vietnam shipping resources for intra-theater use. This additional deep-draft shipping plus the improvements in ship turn-around time in South Vietnamese ports contributed substantially to decreasing the pressure on LST resources and permitted a greater use of LSTs for deliveries to shallow-draft ports in lieu of LCM's and LCU's. Nevertheless, LST requirements continued to be sufficiently heavy to maintain pressure on the allocation and use of theater LST assets.

Transshipment of cargo from major South Vietnamese ports to areas supported by over-the-beach unloading continued on a large scale, although Commander in Chief Pacific favored the development of additional deep-water berths in various ports such as Vung Ro, Qui Nhon, and Vung Tau in order to reduce dependence on LST operations.

The maritime fleet which supported the resupply of combat operations in South Vietnam was inadequate and outdated. Although a majority of the vessels had been in moth balls, they were worn out. These ships required an extensive amount of repair to put them in service and keep them afloat. It would have been more cost effective if we had had a fleet of ships designed to meet the requirements for movement of troops and military cargo.

Containerization

Containerization was an important logistic concept used extensively in Vietnam. About 1950 the Army first developed a concept of utilizing a standard-sized container to give a semblance of automation to the movement of supplies through the pipeline from Continental U.S. stations and depots to overseas units and depots. The standard steel container called container express with a capacity of 9,000 lbs was designed to be carried on trucks and rail cars and be handled by the general purpose 5-ton capacity cargo gear on most ocean freighters.

The Army efforts in containerization originated with the port and supply problems in World War II and Korea and made use of the advances made by other services and industry in unitization and palletization of cargo. All services stressed palletization. In addition to the Army and Air Force investments in container express containers, the Marines had developed two standard-sized mount-out boxes for deploying forces; and the Air Force developed its 463-L system to handle palletized cargo in aircraft.

In early 1965 the Army and the Air Force jointly owned an inventory of almost 100,000 container express containers. Every

[171]

major U. S. Army unit moving to the theater carried its accompanying spare parts and supplies in containers. For example, the U. S. 1st Cavalry deployment included about 2,500 containers, all prominently marked with the big yellow division patch. Army aviation units used containers with prebinned stockage of the myriad of small items-rivets, cotter pins, and nuts and bolts peculiar to aviation support and utilized in large volumes. As the conflict escalated, there was more and more demand for containers, and eventually the theater inventory exceeded 150,000 (of the total 200,000 units then owned by the Army and Air Force).

The 150,000 units in-theater represented about six million square feet of covered storage. This figure is impressive when compared to the fact that only about 11 million square feet of covered storage had been built in the entire theater by the middle of 1969. Few of the containers moved into the theater ever returned. They satisfied a wide variety of needs for shelter including dispensaries, command posts, PXs, and bunkers.

Containers played an integral part in a special project to make Cam Ranh Bay a major U. S. Army supply base. As in most locations in Vietnam, the construction of depot facilities did not keep pace with the influx of supplies and equipment. It was estimated in January 1966 that the Cam Ranh Bay depot would be supporting a force of 95,000 men by the end of June 1966. In an effort to overcome the lack of depot facilities, the Army Materiel Command prepared, in effect, a prepackaged container depot containing a 60-day stockage level of repair parts for all units supported by the depot at Cam Ranh Bay. When completed, the entire package of about 53,000 line items together with a library of manuals, stock records, locator cards, and other documentation, was contained in 70 military van semitrailers and 437 binned containers.

This represented container-oriented logistics in a highly sophisticated form and was also a good example of the integration of supply and transportation systems. The project packages arrived at Cam Ranh Bay on 21 May 1966 and a total of 13,538 material release orders were issued during the first 10 days of operation with only 26 warehouse denials-less than 0.2 percent.

The next step forward in utilization of intermodal containers (containers that can be shipped by rail, truck, air or ship) in support of operations in Vietnam was the introduction of container ship support by Sea-Land Services, Inc. These ships were designed to carry the more familiar Sea-Land container which is essentially a trailer van that can be set on a trailer bed and be pulled by a truck (or on a rail flat car) . The container can be removed from

[172]

the trailer bed and set on the container ship. Special type cranes are needed either at the port or incorporated on the ship. In 1966 Sea-Land began providing container service to the Army on Okinawa. Sea-Land container support was extended to the Navy at Subic Bay in the Philippines. In 1967 Sea-Land was introduced into Vietnam. Since that time every command concerned with the support of U.S. Forces in Vietnam expressed satisfaction with the degree of success achieved in the container ship operations moving general cargo and perishable subsistence into Vietnam.

Ammunition was also successfully handled in container ship service. During December 1969 and January 1970, a Test of Container-',zed Shipment of Ammunition was conducted to determine the feasibility of shipping ammunition from the United States to Vietnam by container ship service. A self-sustaining container ship was used in the test to move 226 containers of ammunition from the United States to Cam Ranh Bay. Some of the containers were unloaded in the ammunition depot at Cam Ranh Bay; others were transshipped on lighterage to Qui Nhon and on to forward supply points. The test was such a success that the 1st Logistical Command recommended the initiation of regularly scheduled ammunition resupply in container ships to reduce order and ship time and provide savings in pipeline inventory. The requirement for initial procurement of container materials handling equipment during the wind-down period in Southeast Asia and the establishment of new procedures for container movement of ammunition resulted in a decision not to use containers for routine ammunition movement.

Experiences of Southeast Asia show real advantages in the use of containers. Cargo is moved faster, there is less damage and loss of cargo and there are major savings in handling costs and packaging. The new transportation technique requires the use of large and expensive equipment and special container materials handling equipment, to include ship or shore side gantry cranes. Accounting and control procedures must also be developed to effectively operate a container system. The system approach must be followed as the size and weight of container limit improvision. If self-sustaining ships are not available, shore side equipment must be provided. All containers and their materials handling equipment must be compatible for both surface (road, rail, sea) and air movement of containers.

Experience with large intermodal containers in Vietnam clearly indicated that their full exploitation could greatly enhance the

[173]

transportation, storage and handling of supplies. The following four advantages speak for themselves:

1. Container ships can be discharged 7 to 10 times faster than breakbulk ships and with fewer personnel. Drastic reductions in berthing space and in port operating personnel requirements also result.

2. The practicality of operating directly out of containers prebinned in the United States is feasible and was demonstrated at Cam Ranh Bay.

3. All recipients of containerized cargo noted a reduction in damaged and lost cargo-particularly ammunition, perishable items, and PX supplies.

4. Because cargo is moved intact in a container from the Continental U.S. to the depot or directly to a forward unit, problems in sorting and identifying cargo are minimized.

Augmenting the container service were Roll-on-Roll-off ships. The Roll-on-Roll-off concept provided a land and water express service comprising the through put concept of cargo between continental United States depots and overseas depots; and also between inter- and intra-theater depots. Cargo is checked at the point of origin and loaded aboard a trailer type conveyance, transported to. a vessel at the port of loading, rolled into the vessel, stowed, and rolled off at the port of discharge and dispatched to forward destinations.

The Roll-on-Roll-off operation combined the U.S. Army Trailer Service Agency with Military Sea Transportation Service Roll-on-Roll-off type ships to facilitate the- movement of general cargo. The service was used for providing scheduled depot-to-depot delivery of combat support items, and gave a faster, more flexible response to theater logistics requirements. It reduced the intransit exposure of ship and cargo to enemy action, reduced oversea supply point requirements, and reduced shiploading and discharge times. It also lessened the requirement for permanent port and rail facilities.

The Roll-on-Roll-off service which had been operating in support of Europe was transferred to Okinawa to support operations in Southeast Asia. Beginning in March 1966, this service operated between Okinawa, Cam Ranh Bay, Saigon, Qui Nhon and Bangkok.

The Military Sea Transportation Service ships Comet, Transglobe, and Taurus plus 2,400 trailers were used in the Roll-on-Roll-off operations. A typical Roll-on-Roll-off ship had the capacity

[174]

to transport Roll-on-Roll-off trailers, containers, or large or small military vehicles.

Materiel Handling Equipment was in short supply during the early build-up in Vietnam. This significantly impaired the unloading of materiel from transportation vehicles and the movement of materiel within the storage areas. This equipment was especially critical due to the palletization concept of stocking and moving supplies. Resupply and retrograde at the most forward logistic support areas were almost totally dependent on Materiel Handling Equipment. Shortages of Materiel Handling Equipment prevented the realization of the full potential of the palletization concept.

In an attempt to meet the urgent demands for Matériel Handling Equipment during the early period, 47 different makes and models were procured. However, this resulted in an almost impossible task of stocking repair parts, which in turn created a high equipment deadline rate. This rate was not lowered until a standardization program was instituted. In 1966, steps were taken to reduce the 47 models to five commercial models plus two rough terrain fork lifts. By August 1967, this has been accomplished and the Matériel Handling Equipment situation improved.

The U.S. maintenance capability (less aircraft) in South Vietnam in March 1965 consisted of a three-bay third echelon maintenance shop in downtown Saigon limited to vehicle and armament repair and instrument calibration, with a work force of ten personnel.

Adequate facilities in early 1965 were a problem. For example, an old rice mill located along the Saigon Canal was selected and acquired in May 1965 for the Saigon area maintenance facility. The buildings were of brick construction with dirt floors covered with two feet of rice hulls. Maintenance personnel removed and disposed of the rice hulls and cleaned out the buildings. Lacking engineer support, maintenance personnel poured their own concrete floors using a road grader to spread the concrete and installed the necessary electrical wiring in the buildings. The maintenance shops were opened one building at a time as they were made usable.

Many direct support and general support units arrived in 1965 without Authorized Stockage Lists or Prescribed Load Lists of repair parts. This problem was the result of three things. Continental U.S. activities did not know what units or types of equipment the direct support or general support units were to support;

[175]

therefore adequate parts lists could not be prepared. Requests from Continental U.S. to the 1st Logistical Command for units and equipment densities could not be satisfied because the information of units and equipment enroute to South Vietnam was not available. In addition, the very fluid tactical situation in South Vietnam in early 1965, with the resultant changes in in-country deployment of combat units, made it almost impossible to develop unit densities of equipment to be supported with any reasonable degree of accuracy. The maintenance effort started short of repair parts and it did not recover until mid-1966. The interim period was characterized by a highly skilled maintenance capability without sufficient repair parts to utilize this capability to the maximum. This period was also characterized by unusually low Operational Readiness rates for engineer equipment, Materiel Handling Equipment, trucks, water craft and generators. All of these were essential items in properly carrying out the logistical mission.

Maintenance Support Positive reevaluated the Army Maintenance System to provide for performance of tasks at the level that provides maximum readiness and cost effectiveness, achieves the best mix of modular and piece parts repair, increases the use of modular design of new equipment, expands direct exchange, improves design and application of test, measurement and diagnostic equipment, optimizes use of mobile maintenance and reduces requirements for complicated tools at the forward levels of maintenance. The maintenance structure must be flexible enough to combine selected levels of maintenance within the Army force structure to permit responsive, effective and efficient application of resources to sustain or improve the operational readiness of a complex commodity or weapon system.

The initiation of the Red Ball Express in December 1965, as a result of the Secretary of Defense's visit to South Vietnam, was a great help in improving operational readiness rates for critical items. As Authorized Stockage Lists and Prescribed Load Lists were developed and received, adequate maintenance facilities were developed, and supported units were stabilized, the Operational Readiness rates increased to the highest ever found in a combat zone. However, these rates were made possible only through the expensive replacement of entire components (engines, differentials, transmissions) at direct support levels. Table 10 shows the Operational Readiness rates for some selected items of equipment between June 1966 and June 1970.

[176]

TABLE 10-OPERATIONAL READINESS (IN PERCENT)

| Items | Military Assistance Command, Vietnam Objective |

Actual Operational Readiness Rates | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| June 1966 | June 1967* | June 1970** | ||

| Tractors | 80 | 80 | 88 | 82 |

| Rough Terrain Fork Lift | 80 | 82 | 87 | 82 |

| M109 How (SP) | 85 | 92 | 92 | 87 |

| M107 Gun (SP) | 85 | 85 | 86 | 93 |

| Generators | 80 | 85 | 89 | 87 |

| (all types) | ||||

| 5-Ton Trucks | 90 | 88 | 90 | 88 |

| (all types) | ||||

* 1968 and 1969 operational readiness rates did not differ materially from those shown for 1967.

** Slight decline shows the impact of Cambodian Operations.

Reorganization in Combat

The war in Vietnam occurred at a time of significant changes in the Army's organizational structure. At the start of the buildup, maintenance support was provided by units of the Technical Services: Chemical, Engineer, Medical, Ordnance, Quartermaster, Signal, and Transportation. Units organized and trained by the Technical Services performed support operations at the field level under doctrine and detailed procedures developed by each Technical Service. The system contained inherent disadvantages because of its fragmentation into seven virtually autonomous structures. In some instances, all seven Technical Services were involved in the support of a single end item, such as a tank. In mid-1966, a reorganization to the Combat Service to the Theater Army concept was begun in Vietnam. This was a large undertaking. It required deactivation of old units, activation of new units, realignment of functions, realignment of personnel, and redistribution of equipment. Combat Service to the Theater Army eliminated Technical Services maintenance units (except medical) and created a functional organization that was compatible with the existing force structure, the divisions and the commodity oriented Continental U.S. base. It eliminated duplication of maintenance training, skills, tools, and test equipment. It was also designed to reduce the span of control of the force commander, increase responsiveness, and provide one stop service and support. The effectiveness of maintenance, however, was impeded initially by the turbulence caused by this reorganization.

The U.S. Army Vietnam maintenance system included all categories of maintenance from the operator's level to limited depot overhaul, as well as calibration of equipment, controlled

[177]

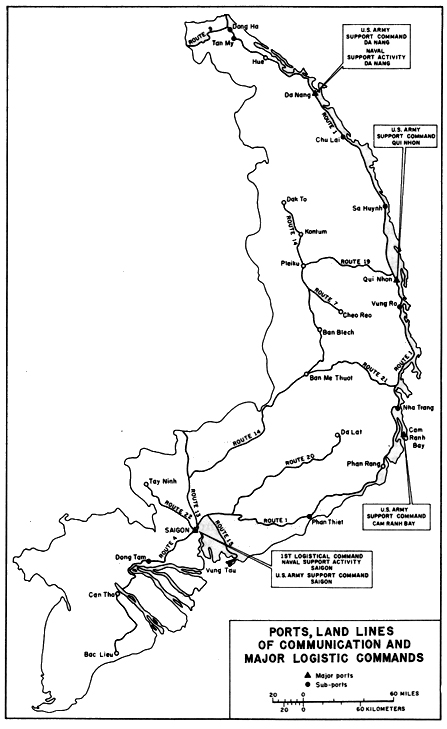

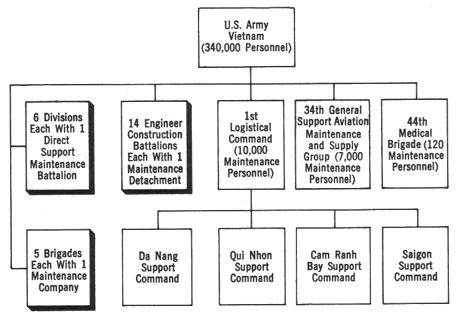

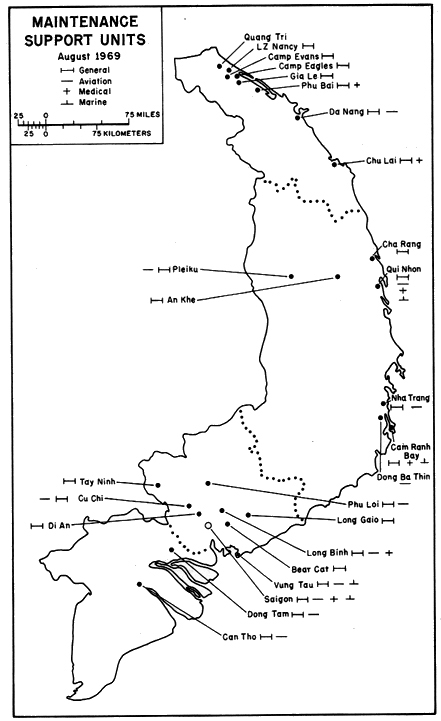

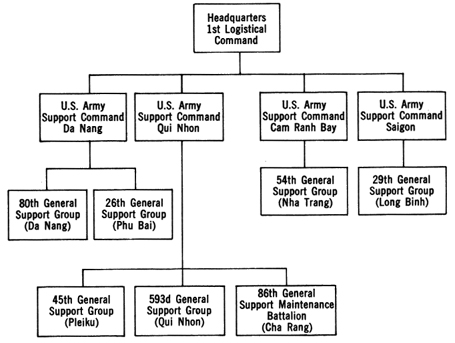

cannibalization, and repair parts supply. Chart 12 depicts the organizational relationship, and the approximate troop strengths of the major maintenance elements of U.S. Army Vietnam as of August 1969. The 1st Logistical Command provided maintenance support of ground equipment to all U.S. Army forces. The U.S. Navy provided common item maintenance support, when requested, to Free World Military Assistance Forces. Map 6 depicts the general location and nature of maintenance support units in Vietnam. All categories of maintenance support were primarily accomplished through the four Support Commands of the 1st Logistical Command. Emphasis was on direct support as far forward as practicable. General support maintenance was provided primarily from the larger logistics bases where more stabilized conditions existed. Depot level maintenance by military units was minimized by the use of contractors in-country and off-shore depot maintenance support.

Between April and September 1965, 15 maintenance companies arrived in Vietnam. By late 1968, 35 maintenance companies were operating in Vietnam. The four Support Commands directed and co-ordinated maintenance services within their areas of responsibility. The nuclei of the maintenance organizations were the general support groups which also served as the command and control headquarters for direct support and general support batta-

CHART 12-ORGANIZATION OF U.S. ARMY VIETNAM MAINTENANCE SYSTEM

(AUGUST 1969)

[178]

[179]

lions. (Chart 13) Composite battalions were also formed within the Support Commands, to assure service within geographical areas. For example, the 57th Transportation Battalion, located at Chu Lai, served as the composite headquarters for two maintenance companies, a transportation company, a supply and services company and several quartermaster platoons. In addition each combat division and separate brigade had its own organic direct support capability. The 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment was an exception. It obtained its maintenance support from the 1st Logistical Command on an area basis. As elements of the regiment relocated, the nearest 1st Logistical Command unit provided service. This method of support proved unsatisfactory because of the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment's high and fluctuating maintenance demands. In the future such organizations should be assigned an organic maintenance unit.

The many isolated positions, such as fire bases and landing zones, were supported through a system of maintenance detachments and contact teams provided from the available resources of support command units. In the major base complexes such as at Long Binh, Da Nang, Pleiku, Qui Nhon and Cam Ranh Bay,

CHART 13-THE 1ST LOGISTICAL COMMAND MAINTENANCE STRUCTURE

(AUGUST 1969)

[180]

forces were concentrated enough to employ conventional battalion-sized maintenance units occupying permanent type facilities.

The in-country maintenance of medical equipment was primarily performed by base and advanced medical depots with the 32d Medical Depot providing technical assistance. However, medical units themselves, operating under the control of the 44th Medical Brigade (which was supervised by the U.S. Army Vietnam Surgeon), performed limited maintenance. Medical maintenance shops were colocated with medical supply depots. The base depot was located at Cam Ranh Bay and subordinate advanced depots were located at Phu Bai, Chu Lai, Qui Nhon, and Long Binh.

Equipment Repair Problems

Generally speaking, U.S. Army equipment in South Vietnam was the best ever fielded in combat. However, the lack of equipment standardization was a frustrating problem. For instance, initially 145 different sizes and types of commercial generators were used by the Army in Vietnam. Repair parts supply was difficult, at best, requiring extraordinary efforts for procurement, and in many cases the repair parts that were available lacked interchangeability. The situation was much the same with material handling equipment. In March of 1966, steps were taken to reduce the 47 Materiel Handling Equipment models then in use to five commercial models plus two rough terrain fork lifts. By August 1967, this was completed.

Another major problem was the difficulty in maintaining some equipment due to its design. Under the adverse environmental conditions encountered in Vietnam, the problem was magnified. For example, the road wheel oil fill plugs on the M551 Sheridan vehicle were located on the inside of the wheels making it necessary for a crew member to crawl underneath the vehicle to reach them. During the monsoon season this was virtually impossible unless the vehicle was inside a building or shelter of some sort. Also, there was no satisfactory way to keep twigs and leaves from being sucked up against the radiator of the M551 and cutting off the required air flow. Therefore engines overheated. Practically all U.S. engines used dry-type air cleaners. To blow off the dust and wash them in soapy water as required by the manuals was not a practical operation under Vietnam combat conditions.

While Operational Readiness rates were high, this was due to the expensive replacements of entire components. The wear out rate of engines, differentials, and transmissions was abnormally high and this was at least partially attributable to operator abuse

[181]

and inadequate organizational maintenance. The cost and efforts involved in transporting, overhauling, and storing the components that should not have been worn out were significant and preventable.

Though not a maintenance fault, failures of multifuel engines created the requirement for a major off-shore maintenance effort and a sizeable supply problem. In January 1967, more than 300 5-ton trucks were deadlined in Vietnam because of inoperative multifuel engines (a similar condition existed for 2½-ton trucks) due to cracked blocks, blown head gaskets, valve stems and connecting rods. A study indicated that many failures occurred between 9,000 and 10,000 miles and that the units hardest hit were the line haul transportation units whose engines were subjected to continuous use (2,000 miles per month in Vietnam). The prospect for improvement at this point was negligible because of the lack of repair parts and overhaul capacity. Multifuel engines powered both 2½- and 5-ton trucks. A similar condition also existed in Thailand. The annual engine replacement rate of 6 per 100 vehicles per year increased to a rate of one engine per vehicle per year.

By the summer of 1967, an airlift program, Red Ball Express was put into effect in an attempt to alleviate the shortage of engines and repair parts. The Red Ball Express was designed to be used in lieu of normal procedures exclusively to expedite repair parts to remove equipment from deadline status. Reserved and predictable airlift was made available for this purpose. The seriousness of the situation led to a multifuel engine conference on 28 August 1967. The conference resulted in several recommendations, the most significant of which was that three multifuel engines, LD 427, LD 465, and LDS 465, were to be placed under Closed Loop Support management because of the inability of units in the field to cope with the maintenance problem. A further recommendation was made that return to the Continental U.S. be authorized for vehicles that could not be supported with multifuel repair parts or replacement engine assemblies. Because a large percentage of the producers' production capacity was consumed in end items assembly, some repair parts and new replacement engine assemblies were not readily available. Department of the Army approved the recommendations of the conference and directed that necessary retrograde, overhaul, and shipping operations be initiated immediately.

Although the conference had focused attention on the supply aspect and premature failure of engines, significant intangibles

[182]

remained unsolved, including proper operation of vehicles and user maintenance. Because of the characteristic difference of the multifuel engine from the standard internal combustion engine, periodic maintenance and specific mandatory operational procedures differed sharply from procedures used with other vehicles and required closer attention. Simply put, despite years of testing effort, the multifuel engine did not possess the ruggedness and tolerance to withstand the abuses inherent in field operations.

Marine Maintenance

With the exception of the newly developed amphibian river patrol boats and Amphibious Cargo Resupply Lighters, there was only one US Army vessel in South Vietnam less than 14 years old. This vessel, the beach discharge lighter Page, was the only ocean going vessel that was not of World War II design. As part of the effort to maintain the over-age fleet, a systematic overhaul of all craft began in 1967, but a shortage of repair parts caused delays. For instance, 14 tugs, or 38 percent of the tug fleet, were being overhauled in out-of-country shipyards at one time. Five of these tugs had been undergoing overhaul for more than one year. This made it necessary to lease seven commercial tugs at a cost of $1,283,000 per year to insure continuity of tug boat service. The excessive amount of man-hours and dollars spent to maintain the obsolete vessels and equipment of the marine fleet make it clear that these should be replaced by an up-to-date fleet.

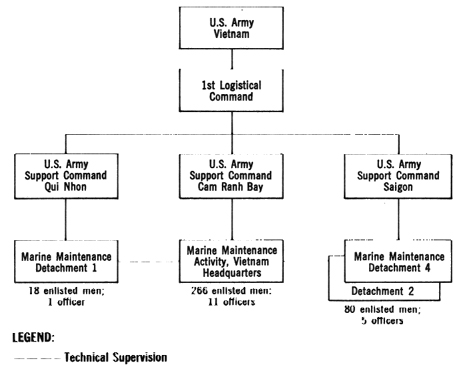

The U.S. Army marine fleet consisted of amphibious and conventional lighters, landing craft, tug boats, barges and other vessels up to 2,200 long tons capacity. To support this fleet, the Marine Maintenance Activity, Vietnam was organized in 1966, with headquarters at Cam Ranh Bay. In 1967 the Marine Maintenance Activity, Vietnam consisted of a headquarters and four small detachments which were positioned in the areas with the largest concentration of marine craft. One was located at Qui Nhon, one at Cam Ranh Bay, and two under the Saigon Support Command. The Marine Maintenance Activity supported the II, III and IV Corps, while the U.S. Navy supported the I Corps. Maintenance beyond the capacity of the Marine Maintenance Activity was accomplished by in-country contractors and at off-shore facilities. Overall responsibility for the marine maintenance mission rested with .U.S. Army Vietnam while operational control was the responsibility of the support commands. The Marine Maintenance Activity exercised technical supervision over the four detachments. The Marine Maintenance Activity, Vietnam

[183]

organization with detachment strengths, as of August 1969, is depicted in Chart 14.

Maintenance Support of Common Items

The major area of interface between the military services and maintenance systems occurred with the support of common items. In general, common maintenance support between the U.S. military services was very limited. Similar to the area of common supply support, the objective of each service for logistical self-sufficiency dominated in the buildup period and tended to persist for the duration. Commonality of equipment too was limited, and effective common maintenance support was frequently impaired by the geographical deployment of the maintenance unit and the "customer" unit in different tactical zones. Insufficient stockage of both common and peculiar repair parts also impeded common maintenance support. An example of this was the equipment of the 3d Armored Cavalry Squadron, 5th Regiment, 9th Division, attached to the 1st Marine Division at Da Nang. Although the Marine Corps did provide Class 1, II, III and V supply to the squadron it was unable to furnish maintenance support. The latter was provided by the U.S. Army Maintenance unit located at Da Nang until the Squadron was withdrawn from the zone and returned to the III Corps area. The U.S. Air Force and Navy received some maintenance support from the Army on such common items as administrative type vehicles in other tactical areas. This same type of general maintenance support was provided to medical and aviation units by the 1st Logistical Command and included some tactical vehicles. For example the Army provided maintenance support for UH-1 helicopters used by the Navy in its "Seawolf" operation and for the Air Force modernization program of 0-1 aircraft and UH-1 helicopters for transfer to allied forces. Conversely under the Army-Air Force basic support agreements the Air Force allocated some 11,000 man-hours per month of its commercial contract capability for maintenance support of Army aircraft. Repair of Army owned test sets and special equipment was also accomplished by the Air Force when appropriate under these arrangements. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, and adviser units lacking maintenance capability were also offered maintenance support. Cooperative exchange arrangements with the Navy were also conducted by the 1st Logistical Command through the Support Commands. For example, the recapping of Army tires and the re-winding of unserviceable motors was accomplished under Navy contracts. Under similar support arrangements the

[184]

CHART 14 - ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE, MARINE MAINTENANCE ACTIVITY, VIETNAM (AUGUST 1969)

Army maintained Marine Corps radar equipment to assure operational readiness. Conversely, the Marine Corps maintenance teams in the Da Nang Area assisted the Army in repairing and cleaning office machines.

The Army also provided maintenance support for common items of materiel in the hands of allied forces, beyond the capability of these forces. These services were furnished under cooperative logistics support arrangements with the allied nations involved.

Maintenance Workload

By 1966, maintenance support was characterized by the heavy over-loading of direct support maintenance units whose normal mission was to repair and return equipment to using units. General support maintenance units were forced to assume direct support missions. The Army reported to the Secretary of Defense on 29 August 1968 that 88 percent of the general support capability had been diverted to direct support level tasks. The resultant lack of general support was compensated for by the stand-

[185]

ardization of equipment, offshore maintenance support, and the Closed Loop System. General support maintenance in-country increased from 371/2 percent of total maintenance in 1966 to 49 percent in 1968.

U.S. Army Vietnam reported that the Army Equipment Records System was generally ineffective in Vietnam. While its objectives were valid, the system was too cumbersome to be used under the stress of combat. It required the collection of detailed information on all the equipment, but this required a level of skill which was not available. The Army equipment records procedures have since been revised and simplified. The new system, designated The Army Maintenance Management System, reduced the organizational reporting and recording effort at the crew and mechanic level by 80 percent and reduced automatic data processing by 50 percent.

Offshore Maintenance Problems

As maintenance requirements in Vietnam increased, it was essential that overhaul capabilities be established in the Pacific Theater to provide responsive support and reduce the lengthy overhaul pipeline. With the development in 1967 of Closed Loop support for armored personnel carriers in Vietnam, the Sagami depot maintenance capabilities in Japan were expanded to enable it to support the requirements of the Eighth Army, U.S. Army Vietnam and the South Vietnamese Army. Production schedules were increased after a successful effort to recruit additional personnel. A labor force of approximately 615 was employed at Sagami by the end of June 1967.

Okinawa continued the marine craft maintenance programs, with a strength of 210 personnel devoted to that mission. In 1967, as U.S. Army Vietnam overhaul requirements continued to increase, the problem with multifuel engines required the establishment of overhaul and modification programs on Okinawa. The number of maintenance personnel was increased to 1,381. These programs included maintenance of trucks, construction equipment, electronics and communication equipment, materials handling equipment, and marine craft.

During 1966 and 1967, maintenance units were deployed to Okinawa as a part of the 2d Logistical Command, which was charged with the support of island forces and offshore general support for Vietnam. The general support workload was primarily for tactical wheeled vehicles, generators, materials handling equipment, and electronic communications items, and amounted to 50

[186]

percent of the Vietnam requirement. This level of effort was maintained through 1969.

In 1965, Army overseas depot level maintenance existed on a limited basis in Germany and Japan. Depot maintenance activities were manned principally by local nationals with few spaces authorized for officers and non-commissioned officers. The only Army depot level facility in the Pacific was located at U.S. Army Depot Command, Sagami, Japan. Depot capability in Japan consisted of a work force of 504 local nationals devoted to maintenance of Military Assistance.

By 1969, overhaul in the Pacific reached a cost level of $35 million. Production of combat vehicles in Japan was increased to 100 personnel carriers and 12 tanks per month. Marine craft maintenance contracting functions were assumed from the Navy and the use of all existing commercial facilities continued. By the end of June 1970, the following offshore organic depot maintenance personnel strengths had been reached.

| Military | DA Civilian | Local Nationals | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Okinawa | 754 | 141 | 1014 | 1909 |

| Japan | 56 | 37 | 1257 | 1350 |

| 3259 |

Phasedown of Maintenance Support

Combat units in process of standing-down prior to redeployment from South Vietnam turned in large quantities of equipment. During September 1969, a Special Criteria for Retrograde of Army Materiel was instituted for Southeast Asia. This criteria provided simplified inspection and classification procedures for quickly determining the condition of materiel being considered for reissue, retrograde, or maintenance. As a result, equipment can be classified and retrograded promptly with less skilled personnel than would be required if full technical inspections were used. Some scrap may have been shipped out of country and some serviceable assets may have been scrapped, but equipment was moved at the same rate troops were withdrawn. Generally serviceable equipment was retained. Only borderline unserviceable items may have been misclassified. This was not a great price to pay to insure meeting troop withdrawal and equipment turn-in schedules.

[187]

page created 2 January 2003