[21]

Before considering the climactic battles of 1968 it is well to consider several significant developments in the I Corps Tactical Zone: the project for an anti-infiltration system, the increasing use of other Free World Forces, the buildup of logistical facilities in the area north of the Hai Van Pass, and the upgrading of the Vietnamese Army in the northern provinces.

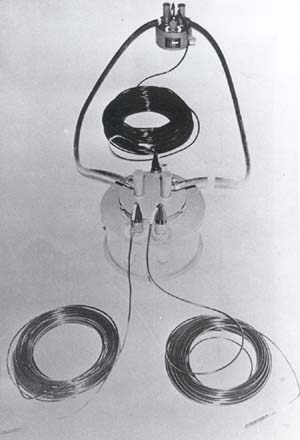

The anti-infiltration system, popularly known as the McNamara Line or Electric Fence, was envisioned as a 40-kilometer-long physical barrier supported by early warning devices and carefully selected fortified positions constructed on key terrain and manned as appropriate. It was intended to counter the massive infiltration of North Vietnamese troops and equipment across the demilitarized zone. The sensors, early warning devices, were designed to be used in a linear obstacle field. (Diagram 1) The balance pressure system would indicate any increase in weight, such as that produced by a person walking over it. The infrared intrusion detector operated in a manner similar to burglar detectors or an electric eye used to open the door of many business establishments. Unattended seismic detectors were used to note and report earth vibrations such as those caused by a group of men walking down a trail. Acoustic sensors transmitted the sound when men stepped on small explosive devices.

The majority of the firepower supporting the system came from artillery, tactical air fire, and naval gunfire. The system was designed to reduce the need for costly operations in an area constantly subjected to enemy-directed artillery and mortar fire from adjacent sanctuaries. The marines also hoped to use the anti-infiltration system to detect enemy incursions and movements at greater ranges. The system was an overall effort to counter both enemy infiltration and direct invasion by making enemy movement across the demilitarized zone simultaneously more expensive for the attacker and less expensive for the defender.

Work on the project began in April 1967. As the year pro-

22

gressed, both the intensity of the enemy's mortar, artillery, and rocket fire and the changing military situation slowed down the development of the strong points and the construction of obstacles. The project was shelved when the buildup of U.S. forces in I Corps pre-empted the logistical support needed to supply the construction material.

Although the barrier was never completed, certain portions of it were sufficiently developed to permit their use. The defense positions along the line were turned over to the Vietnamese Army, thereby freeing the American troops for mobile operations. Some of the early warning devices later used during the siege of Khe Sanh were reported to be effective. The information derived from the sensors provided targeting data for bombing and artillery strikes. While alone no deterrent to enemy movement, they provided a portion of the information that enabled friendly forces to bring the enemy under fire. (Diagram 2) The monitoring devices could be dropped from planes and helicopters, hung in trees, placed along river banks, or buried underground.

In 1970 Congressional hearings were called to discuss the value of the instruments. They were credited with saving many lives by giving ground troops early warnings of attack. The sensors were credited further with increasing enemy personnel and equipment

23

BALANCE PRESSURE SENSOR SYSTEM

losses as well as providing the Army with combat surveillance that worked by day or night. They were said to improve the effectiveness of air interdiction of enemy truck-borne troops and supplies and to

24

DIAGRAM 2-SAMPLE TACTICAL APPLICATIONS

conserve manpower. Some troop commanders stated that the use of the sensors permitted them to fight a major battle without the presence of their men. The sensors contributed to what was a difficult and, possibly the most important, task: finding the enemy and keeping track of his movements.

Aside from the conventional U.S. Army organizations, other U.S. and Free World Military Assistance Forces contributed to the failure of the North Vietnamese to achieve significant success in I Corps. Among these were the U.S. Special Forces, the Vietnamese Civilian Irregular Defense Group, the Vietnamese Special Forces, the Republic of Korea Marines, and the Australian Advisors. (Chart 1)

The U.S. Special Forces in Vietnam were prominent in their advisory role in which they assisted the Vietnamese Special Forces in organizing, training and leading Civilian Irregular Defense Group companies on operational missions. These companies had

25

CHART 1- U.S. Marine and Popular Forces Combined

Action Platoon Organization

more than 3,000 men in I Corps and usually operated from isolated Special Forces camps, like that at Lang Vei. The U.S. Special Forces often provided the means of reporting enemy activities in sparsely populated areas of the country. Not as well known were the U.S. Special Forces' long-range patrol teams which roamed the areas normally thought as being under enemy control. These teams provided much valuable information on enemy locations and activities. On occasion they harassed the enemy by conducting ambushes or raids in areas where the enemy felt himself secure.

After the United States, the nation which supplied the greatest amount of assistance to the Republic of Vietnam was the Republic of Korea. This aid was particularly significant in light of the potentially explosive security situation that existed along the Republic's borders with the Communist Regime of North Korea. It was also indicative of the concern which the Republic of Korea manifested for the freedom, progress, and liberty of its Asian contemporaries.

26

The Koreans entered I Corps Tactical Zone in August of 1966 when the Korean 2d Marine (Dragon) Brigade moved south of Chu Lai in northern Quang Ngai Province. Previously this unit had assumed the role of mobile trouble-shooter and had moved from its first location at Cam Ranh Bay to Tuy Hoa, then to the new zone south of Chu Lai. In 1966 and the following year, the brigade was in the vicinity of Hoi An, Quang Nam Province. Each time, the brigade's arrival in I Corps enabled the U.S. Marines to shift their forces further north where the continuing and increasing threat of invasion across the demilitarized zone existed.

The Koreans proved themselves adept in establishing rapport with the local population by stressing the kinship of aspirations and the "brotherhood" of the Asiatic peoples. Because many of the Korean troops had agricultural backgrounds, a natural kinship developed with the rural inhabitants of South Vietnam. Improvements in farming techniques and village accommodations resulted.

Korean forces conducted a number of the most imaginative and skillful operations of the war. They proved themselves to be masters in the patient collection of intelligence and in the effective use of it.

The Growth of Logistic Facilities

The development of logistic facilities had a great influence on the war in the northern provinces. The deployment of major Army units into I Corps in 1967 required the establishment of a support facility at Da Nang to furnish supplies peculiar to the Army. Eventually this organization assumed responsibility for Army support activities in Chu Lai and was required to establish a subordinate support command in the Phu Bai area with a forward support area at Dong Ha. In each of these areas, construction of troop billets, storage areas, roads, water supply systems, and various other facilities was required to provide adequate support for combat operations.

Before 1967, at General Westmoreland's direction, a campaign planning group had been established at United States Army, Vietnam, Headquarters. By mid-January 1967 this group had a contingency plan for troops, ports, roads, airfields, pipelines, combat support units, and service support units. The plan included requirements for a force about the size of the Free World Military Force that eventually deployed to I Corps. This foresight provided a detailed plan that was adaptable to the situation which developed in the northern provinces.

Logistic support in northern I Corps was dependent upon hazardous coastal shipping systems running north from the great

27

AERIAL VIEW OF HIGHWAY NORTH OF DA NANG

deep-water port of Da Nang to several shallower off-loading points in the vicinity of Hue and Dong Ha. The huge quantities of construction material required to build fortifications south of the de-

28

militarized zone greatly taxed these already overloaded facilities and resources. To meet the existing requirements and plans for major operations in the A Shau Valley and other enemy base areas in the north during 1968, the number of landing craft sites north of the Hai Van Pass was increased to 18 and tonnage capacity was increased ten-fold from 540 tons per day to 5,550.

A most ambitious road project was the opening of coastal Route I along its entire length from the demilitarized zone to Saigon. This undertaking involved a series of military and engineering operations by many units stationed along the route, first to secure the road in the various tactical areas of operation, then to replace destroyed bridges and repair damaged sections of the route. Major sections of the road in the Da Nang area of Quang Nam Province of I Corps had been secured in the spring of 1965, when U.S. Marine units first moved into the area. In the spring of 1967, the 3d Marine Division secured the section north of the Hai Van Pass in Thua Thien and Quang Tri Provinces. Meanwhile, in the southern provinces of I Corps, Task Force OREGON cleared the section running from northern Quang Ngai through Quang Tin and into the southern part of Quang Nam Province.

Upgrading of the Vietnamese Army Forces

During 1967, the role of the 1st Vietnamese Army Division in I Corps expanded. In an effort to assist the division in adopting a larger role and to assume increased responsibility, planners took certain steps to increase its firepower. Starting in September 1967, the 1st Vietnamese Division's firepower was supplemented by the provision of such crew-served weapons as the 106-mm. recoilless rifle, 60-mm. mortars, and the modern M60 machine gun. Later in the year the division was further strengthened by the issue of the M16 rifle. There followed a noticeable increase in the morale of the division. With this greatly improved firepower, the division could be counted on for a larger part in the battles in the northern zone. A regiment of the Vietnamese 1st Division later relieved the marines occupying a sector of the defenses facing the demilitarized zone.

The Vietnamese 1st Division was given priority for this equipment in order to increase its firepower and to minimize the number of U.S. forces needed in northern I Corps, where the war continued to intensify. In the following year, the same process was repeated with the Vietnamese 2d Division in the southern portion of I Corps Tactical Zone. When their firepower was upgraded in similar fashion, they in turn assumed a larger combat role.

page created 15 January 2002