Chapter X:

Conclusions and Summary

The joint river operations conducted by the U.S. Army

and Navy in South Vietnam contributed to the success of the military

campaign in the Mekong Delta and added substantially to U.S. knowledge of

riverine operations.

The strategic concept embodied in the plan for the Mekong Delta Mobile

Afloat Force and approved by General Westmoreland in 1966 proved sound and

provided a workable blueprint for a variety of projects carried out by the

Mobile Riverine Force in the two years it operated. The concept recognized

the importance of the Mekong Delta and its resources to the whole conflict.

Although the operations planned for the river force ranged from the vicinity

of Saigon south through the delta to Mui Bai Bung (Pointe de Ca Mau or Camau

Point) at the southern tip of Vietnam, early priority was given to areas in

southern III Corps and northern IV Corps. In executing the plan, the Mobile

Riverine Force was faithful to the priority assigned to the northern delta,

but never carried out fully the intent of the plan approved by General

Westmoreland to extend and sustain river operations south of the Bassac

River. The operations remained primarily north of the Bassac River in

keeping with the area of responsibility assigned to the 9th Infantry

Division in that area; the increasing role of the 2d Brigade in the

division's plans; and the decrease in operational control of the force by

the senior adviser of the IV Corps Tactical Zone.

Perhaps the most significant organizational aspect of the Mobile Afloat

Force concept was the integration of Army and Navy units to provide a force

uniquely tailored to the nature of the area of operations. Specifically, the

capabilities of the two services were used to the fullest by combining

tactical movement of maneuver and fire support units by land, air, and

water. To this combination was added the close support of the U.S. Air

Force. The Mobile Afloat Force plan stipulated that these mobile resources

were not to be dissipated on independent U.S. operations but were to be used

in close co-ordination with other U.S. and Free World Military Assistance

Forces.

[185]

The Mobile Riverine Force, which was the organizational implementation of

the Mobile Afloat Force concept, was a fortuitous union of the Navy's River

Assault Flotilla One and the Army's 2d Brigade, 9th Infantry Division.

Somewhat controlled by circumstances, events,. and time, the alliance

depended upon a spirit of co-operation and the initiative of the two

component commanders in the Mobile Riverine Force. Guidance for the

commanders was largely contained in the Mobile Afloat Force plan itself, and

from the outset it was up to the commanders to make the plan work. Although

many innovations were made to improve equipment and procedures, they caused

little deviation from the basic Mobile Afloat Force plan. The most important

innovation was the mounting of artillery on barges to provide the force with

the direct support of an artillery battalion that was so urgently needed.

Another innovation was the building of helicopter landing platforms on

armored troop carriers and the use of a helicopter landing barge as an

integral part of the forward brigade tactical command post. The adaptation

by the naval commander of placing the Ammi pontons alongside the Mobile

Riverine Base ships eliminated the need for cargo nets and enabled an entire

company to transfer from a barracks ship to assault craft safely in less

than twenty minutes.

The decision of Secretary of Defense McNamara in late 1966 to cut the

requested number of self-propelled barracks ships by three eliminated

berthing space for two of three infantry battalions. The Navy, however,

resourcefully provided space for one of the two battalions by giving the

force an APL-a barracks barge-and a larger LST of the 1152 class. The

Secretary of Defense's decision could have been disastrous to the execution

of the Mobile Afloat Force plan had these innovations by the Navy not been

made. Even so, the brigade was forced to operate without the third maneuver

battalion; the Army commander was obliged to double his efforts to secure

the co-operation of Vietnam Army and other U.S. units in order to make the

tactical operations of the Mobile Riverine Force successful. It can be

postulated that this effort by the brigade commander to assemble a

sufficient force consumed much attention and energy that could have been

applied to other problems. It can also be argued that the shortage of men

and the necessity to operate in conjunction with the Vietnam Army generated

successes that might not otherwise have been achieved if the full maneuver

force had been provided and if the force had operated less frequently in

co-ordination with Vietnam Army units. Although the original Mobile Afloat

Force concept provided for co-operative

[186]

and co-ordinated efforts with the Vietnam Army, the shortage of troops

increased the need for provincial and divisional units of the Vietnam Army

throughout the various areas in which the Mobile Riverine Force operated.

It should be noted that the mobile riverine base provided for in the

original plan made the force unique. When one considers that this Army and

Navy force of approximately 5,000 men, capable of combat and containing

within itself combat service support, could be moved from 100 to 200

kilometers in a 24-hour period and could then launch a day or night

operation within 30 minutes after anchoring, its true potential is apparent.

With such capabilities the force was able to carry out wide-ranging

operations into previously inaccessible or remote Viet Cong territory.

The original Mobile Afloat Force concept had drawn heavily on the

successful features of French riverine operations and the subsequent

experience of the Vietnamese river assault groups. The Mobile Riverine Force

was able also to capitalize on the knowledge of shortcomings of these

earlier experiences. Both the French and the Vietnamese had used a fixed

operational base on land. French units were small, rarely consisting of more

than a company and five or six combat assault craft. Vietnam Army ground

commanders merely used the river assault groups to transport their forces:

Neither the French nor the Vietnamese had joint ground and naval forces.

Both lacked the helicopter for command and control, logistic resupply,

medical evacuation, and, most important, reconnaissance and troop movement.

The river bases of French and Vietnam armed forces proved more vulnerable,

especially during darkness, than did the afloat base of the Mobile Riverine

Force. Finally, the Mobile Riverine Force, because of its mobility, strength

of numbers, and Army-Navy co-operation, was capable of sustained operations

along a water line of communications that permitted a concentration of force

against widely separated enemy base areas. This was not true of the French

or Vietnam Army riverine operations because of the small size of the forces

and their dependence on a fixed base.

While the problem of command relationships did not inhibit the operations

of the Mobile Riverine Force, it was a tender point in the conduct of all

activities. Considering that the Army effort to develop riverine doctrine

was not accepted by the Navy component commander at the outset, the Mobile

Riverine Force might have been faced with insurmountable co-ordination

problems, but such was not the case. Relying on the Mobile Afloat Force

plan,

[187]

each component commander had a guide to follow as to common

objectives and procedures until doctrine was refined by combat experience.

No joint training for riverine operations was given in the United States

because of lack of time and the wide geographic separation of Mobile

Riverine Force units, but early joint training in Vietnam was planned.

Fortuitously, this training commenced at the river assault

squadron-battalion level under the supervision of the advance staff of River

Assault Flotilla One at Vung Tau. Although the training in the Rung Sat

Special Zone was under combat conditions, tactics and techniques were

developed at the boat and platoon, company and river division, battalion and

river assault squadron levels. During the period February-May 1967 the

flotilla and brigade staffs were able to arrive at a common understanding as

to organizational procedures and operational concepts. By starting at the

boat and platoon level, the Mobile Riverine Force procedures were built on

the needs of the lowest level units, and brigade and flotilla command and

staff procedures were developed to meet these needs. With the 2d Brigade

conducting tactical operations in the delta during the dry season of early

1967 and the flotilla staff co-ordinating the Rung Sat operations involving

2d Brigade battalions, both staffs gained valuable riverine experience

independently. Later, as part of the transition into the Mobile Riverine

Force, the advance staff of the flotilla joined the brigade staff in April

at Dong Tam. This also provided a necessary step from the single battalion

and river assault squadron level of operations to multi battalion, brigade

and flotilla operations in late April and May of 1967.

The Mobile Riverine Force command relationships as published in a

planning directive from Headquarters, Military Assistance Command, Vietnam,

were a compromise to obtain Navy participation in the Mobile Riverine Force.

Recognizing an ambiguous, undefined division of command responsibilities

between the Army and Navy commanders, the directive compensated for this in

part by instructing the chain of command of both the Army and the Navy at

each level within the theater to insure co-operative effort. It also

instructed the commanders at the lowest level, preferably at the Army and

Navy component level of the Mobile Riverine Force, to resolve any problems

that might arise. This planning directive, which incorporated the doctrine

of close support and mutual co-operation and co-ordination, successfully

established the tenor of what was to follow. The Navy was placed in a close

support

[188]

role that adhered closely to the Army principle of direct support. The

Navy's decision in mid-1966 to make command and security of the Mobile

Riverine Base an Army responsibility resolved a problem that could have

become very difficult. Actually the Navy commander assumed tactical control

only while the Mobile Riverine Base was being relocated. In all other

instances he was cast in the role of supporting commander as long as Navy

doctrine was not violated. The Army commander, acting in response to

directives, operational plans, and orders from his higher headquarters,

determined the plan of operations, which required the naval commander

to support his objective. The major factor influencing the relationship

between the Army and Navy commanders was the Navy commander's wish to

operate independently of the 9th U.S. Division. This insistence provided the

one element of disharmony in planning and conducting operations as an

integral part of the land campaign for the delta. While it was never stated,

it can be assumed that the Navy commander's position reflected the wishes of

his Navy chain of command to have separate operations. In defense of the

Navy's total effort, however, it can be said that the Navy commander was

quick to accede to the basic concept of employing the Mobile Riverine Force

in co-ordination with land operations. The activities of the Mobile Riverine

Force, in fact, were directly related to the total land campaign being

conducted in both III and IV Corps Tactical Zones. Joint operational orders

were published and the relationship of the Army and Navy staffs in all

planning and operational functions, including the establishment and manning

of a joint operations center, was very close.

Perhaps the only area where a clear delineation of responsibility was not

possible was at the boat and river division, river assault squadron, and

battalion levels. The Navy river assault squadron organization did not

parallel that of the Army battalion. Both the platoon leader and the company

commander were dealing with Navy enlisted men, while the battalion commander

was dealing with a lieutenant senior grade or a lieutenant commander without

a comparable supporting staff equivalent to the staff of the battalion he

was supporting. The Navy was thus placed in an awkward position,

particularly in the event of enemy attack against an assault craft convoy.

During the first six months to a year of operations, and prior to rotation

of the initial Navy and Army commanders, it was normal procedure for the

Navy element to answer directly to the Army officer in command during

assault craft movements. The Navy craft did not use direct fire unless

explicitly authorized by

[189]

the brigade commander. As time passed and commanders rotated. however,

the procedures established in the Rung Sat and in tile first six months of

Mobile Riverine Force operations became vague and ambiguous since they were

not committed to written joint Standing operating procedures. The

difference in staff's below the brigade and river flotilla level fostered a

centralization at the flotilla and brigade level in planning, control, and

execution. While the Mobile Riverine Force operations gradually adhered

more to the principle of decentralized planning and execution, future

Mobile Riverine Force organizations should correct the disparity in the command and control organizations between echelons of

the two services.

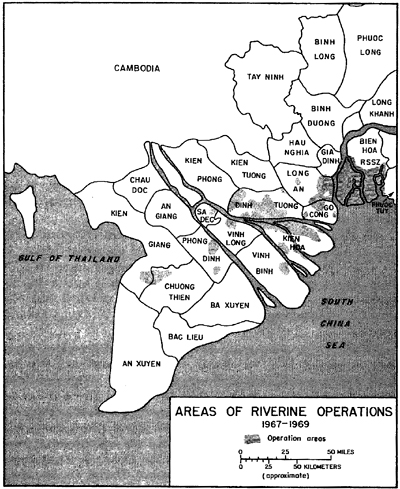

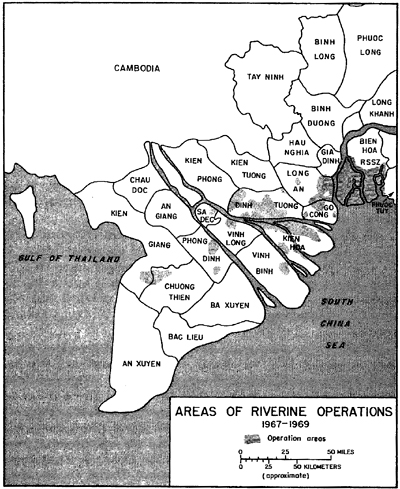

The first year of operations of the

Mobile Riverine Force was highly

successful because the original Mobile Afloat Force concept was carried out

faithfully. The operations of the Mobile Riverine Force were

wide-ranging-the force was in combat in nine provinces and the Run; Sat

Special Zone. These were essentially strike operations against remote enemy

base areas drat in some instances had not been penetrated in force for two

or three years. From these base areas the main force Viet Cong units and the

political underground had influenced the local population whose support

was vital to the strategy of the Viet Cong. Because of the hold and frequent

movement of the large Mobile Riverine Base from which strike operations

could be launched with ease, the element of surprise so important to combat

success was achieved. In most cases enemy defenses and tactics were directed

toward evasion or resistance to air and land assaults. Early riverine

operations often capitalized on these energy dispositions. Later, wren the enemy learned to orient his defenses toward

the waterways, the 9th

Division commander provided the helicopter support necessary to enable

troops to maneuver rapidly front the land side against the enemy. As the first U.S. maneuver unit to conduct sustained operations in tile IV Corps

Tactical 'hone, the Mobile Riverine Force developed good relationships with the

commander of tile 7th Vietnam Army Division ;in([ elements of the 25th

Vietnam Army Division. Co-ordinated large-scale operations were conducted in

a number of remote areas, contributing to the erosion of Viet Gong

strength, which before the advent of the U.S. forces in the area had been

equal to that of the Vietnam Army. While the efforts of the Mobile

Riverine Force were primarily concentrated against Long An and Dinh Tuong

Provinces, key economic provinces for control of the delta, the force also

was able to strike in Go Gong and Kien Hoa Provinces. Although only

indirectly related to pacifi-

[190]

cation, the limitations imposed on Viet Cong movement and the losses

inflicted on Viet Cong units resulted in a reduction in the influence of the

Viet Cong on the people in the area.

During the Tet offensive of January-February 1968, the Mobile Riverine

Force was used in succession against Viet Cong forces in the populous cities

of My Tho, Vinh Long, and Can Tho, which were seriously threatened. After

the battles for these cities, the Mobile Riverine Force was credited with

having "saved the delta" by its direct action against the enemy in

these important centers before the Vietnam Army was able to rally its

forces. Here again the fact that this large, concentrated force with its own

base could be moved so rapidly over such great distances was the key to the

Mobile Riverine Force's success against the Viet Cong in the IV Corps

Tactical Zone.

During the spring of 1968 when the Mobile Riverine Force was placed under

the operational control of the senior adviser of IV Corps, it again

successfully penetrated remote areas. The IV Corps, however, had not the

aircraft or supplies to sustain Mobile Riverine Force operations, and the

force :was therefore available only intermittently to the senior adviser of

the IV Corps Tactical Zone.

When 9th Division headquarters moved from Bearcat to Dong Tam in August

1.968, its mission was concentrated in Long An, Dinh Tuong, and Kien Hoa

Provinces. (Map 16) With this focusing of the area of responsibility on the

Mekong Delta, it can be assumed that the division commander strongly wished

to integrate the Mobile Riverine Force into the divisional effort. Further,

a renewed emphasis on pacification shifted the strategy away from strike

operations, and as a consequence the Mobile Riverine Force largely

concentrated on Kien Hoa Province. During the late summer of 1968

helicopters for troop lift were almost eliminated from the support of the

force. The 9th U.S. Division decided to provide airlift chiefly for the

other two operating brigades and to place almost total reliance on water

movement for the 2d Brigade. This decision was a deviation from the initial

operational plan of employing the Mobile Riverine Force for strikes

utilizing boats and helicopters, a plan that had proved successful in the

previous year's operations. Not until October of 1968 was the Mobile

Riverine Force again provided with helicopters in keeping with the initial

concept.

Restriction to one geographical area had limited the force in mid-1968,

especially in respect to attempting surprise, and it was

[191]

MAP 16

obliged to resort to other means of deception. The Viet Cong were able,

however, to analyze and anticipate movements on the waterways, reportedly by

using a warning system established along the banks. Because of limited and

predictable water routes and a growing enemy knowledge of the Mobile

Riverine Force, river ambushes became more common. When aircraft were

lacking, the force was unable to retaliate except from the water. Nor was it

any longer permitted to make the long moves to new areas as set forth in the

Mobile Afloat Force concept. With the full use of helicopters beginning in

October, the force produced results comparable with

[192]

or superior to those of other 9th Division brigades and with the results

obtained by the Mobile Riverine Force during its first year in South

Vietnam.

The Mobile Riverine Force made significant contributions to the war in

Vietnam. Its presence in 1967 and 1968 tipped the balance of power in the

northern portion of the Mekong Delta in favor of the U.S. and South Vietnam

forces. Dong Tam was developed as a division base without reducing the firm

ground available to Vietnamese units in the delta and activities of the base

increased the security of the important nearby city of My Tho. The Dong Tam

area at one time had been under strong Viet Cong influence, and main force

and local enemy units moved virtually at will until U.S. occupation of Dong

Tam began in January 1967. As operations by battalions slated to join the

Mobile Riverine Force continued, both the 514th and the 263d Viet Cong

Battalions were brushed back from the populated area into the more remote

Plain of Reeds. Even though the Viet Cong 261st Main. Force Battalion was

brought as a reinforcement from Kien Hoa into Dinh Tuong Province in June of

1967, the combined operations of the Mobile Riverine Force and 7th Vietnam

Army Division kept the Viet Cong from moving freely around Dong Tam.

Riverine operations inflicted significant casualties on Viet Cong units and

made them less effective. Highway 4, the main ground artery of the delta,

which was often closed to traffic in the period 1965 through early 1967, was

opened and the farm produce of the delta, both for domestic and export

purposes, could reach the markets. With the completion of Dong Tam Base, the

9th Division headquarters and three brigades were finally able to move into

Dinh Tuong Province and the security of the northern portion of the delta

was vastly improved. When the Navy extended its efforts to the Plain of

Reeds and far to the west toward the Cambodian border in late 1968 and 1969,

its operations were made easier by the earlier operations of the Mobile

Riverine Force during 1967 and 1968. The Navy SEA LORDS operations evolved

from the concept that fielded the Mobile Riverine Force and GAME WARDEN

operations.

The Mobile Riverine Force wrote a distinct chapter in U.S. military

history. The joint contributions made by the Army and Navy resulted in the

accumulation of a body of knowledge that has been translated into service

publications setting forth joint doctrine on riverine operations. In the

event of future riverine operations, the service doctrine recognizes the

need for a joint task force com-

[193]

mander to provide unity of command. Those involved in the early

operations of the Mobile Riverine Force possessed no prior riverine

experience and were forced to rely on historic examples, their own judgment,

and related Army and Navy doctrine to build a new American force. While

basic service differences did arise from time to time, those immediately

responsible at all echelons from the soldier and sailor on up found

reasonable solutions and carried them out effectively and harmoniously to

the credit of both services.

[194]

Page created 29 May 2001

Previous Chapter

Return to the Table of Contents