CHAPTER III

The General Staff:

Its Origins and Powers

The powers and responsibilities of the World War II Chief of Staff and of the office that both counseled him in his planning and assisted him in the execution of his wishes sprang in part from authorization by Congress, 1 in part from direction by the President as Commander in Chief, and, in some cases, from an unopposed assumption of duty. They had been accumulated over a period of years, beginning with a stormy period immediately after the Spanish-American War when the blunders and confusion of the War Department direction during that conflict made clear the need of wholesale reforms. 2 The changes brought about under the far-seeing leadership of Secretary of War Elihu Root constituted a total reorganization. Previously the War Department, under the Secretary but sometimes in practical defiance of him (as when General Sherman moved his office away from Washington altogether),3 had been ruled in part by the Commanding General of the Army, and in part by the several chiefs of bureaus long entrenched in office and able through friendly Congressmen to influence or even dominate the Commanding General. Aided by the advice of a very few officers and by an industrious study of the military systems of Europe, Secretary Root practically drove through Congress the legislation that in 1903 produced the General Staff of the Army having forty-five members. The Chief of that Staff was recognized as the principal officer of the Army deriving his powers from the President as Commander in Chief by way of the Secretary of War, but his functions, it was clearly stated, would be

[57]

advisory rather than operative. This limitation of authority was a concession to an opposition so powerful and so varied that Secretary Root and his supporters saw that compromise was necessary. The veteran Commanding General of that day, Nelson A. Miles, was so fully opposed to the creation of a General Staff that the original bill had to be put over for one term of Congress; in that interval General Miles was retired from active duty. The principal chiefs of bureaus were equally opposed and longer-lived. They and their successors for many years after the Staff's creation effectively opposed reforms by exploiting in Congress the theory that a powerful General Staff would clamp militarism upon the nation.4 So powerful were the bureau chiefs and so confident of Congressional favor that the Adjutant General of 1912, a man of great capacity and will power, offered open defiance to the Chief of Staff and the Secretary as well, and was promptly relieved from duty.5 His voluntary retirement from the Army followed immediately. Even so, his continuing influence in Congress provided fuel for a Congressional vendetta against the current Chief of Staff and against the "militaristic" activities of the General Staff itself; accordingly the Staff's membership was reduced from the original forty-five to thirty-six. Four years later, the National Defense Act of 1916 (which otherwise was a considerable step toward coping with a war already raging in Europe) contained a clause that almost hopelessly crippled the Staff: it granted a small increase in the number of its officers but added a mischievous condition-that not more than half the total should be stationed "in or near the District of Columbia." 6 It left the United States with a General Staff of 19 officers, against Germany's 650. 7 The restriction had tragic consequences for the nation in 1917, but it supplied the next generation of Army officers with a memorable lesson upon the desir-

[58]

ability of keeping on good terms with Congress; the Chief of Staff in office on the eve of World War II was to display more tact and understanding than had his predecessor of a quarter century earlier, and this was destined to redound to his and to the nation's great advantage.

The General Stays Changing Pattern

The Staff had started out in 1903 with a membership ranging from general officers to captains. It contained a grouping that provided members with separate geographical responsibilities. By another grouping it was organized in three functional divisions, dealing respectively with administration, with information, and with planning, military education, and technical considerations. In 1908 the functional "divisions" became "sections" (these terms were exchanged back and forth for years to come) and the second and third were consolidated into one. Two years later Gen. Leonard Wood as Chief of Staff re-established three divisions, but on a wholly different scheme. This time the first division was responsible for the mobile army, the second for the coast artillery and other non-mobile installations, and the third for planning and military education, including the functioning of the War College. The elaborate fiction of 1903 (apparently necessary to get the General Staff started) that the Chief of Staff could be the Secretary's principal adviser and yet have no command authority over the rest of the Army and War Department now came to test in the case of Adjutant General Ainsworth, just referred to. As noted, the Chief of Staff won his fight, but he almost lost his war, for the legislative sequels of that conflict left the infant General Staff weaker in numbers than it had been before and with a set of war plans almost wholly unrelated to such realities as the availability of personnel and materiel alike. From its weakened state, made the worse on the eve of World War I by widespread isolationism and extreme pacifism in Congress and nation, with resultant hostility to Army preparedness, the War Department was revived by the appointment of a Secretary of War of exceptional capacity, Newton D. Baker, and by the actual arrival of war's compulsions. A mechanism so badly handled for years did not quickly start moving again. Of the incompetence and confusion of both Department and Staff there is ample evidence in the contemporary criticisms by Generals John J. Pershing, James G. Harbord, and Robert L. Bullard 8 and the later estimates of Gen. Peyton C. March.9 So acutely did

[59]

General Pershing, who had gone to France with the first elements of the American Expeditionary Forces in June 1917, need to have in Washington a Chief of Staff acquainted with modern war and with A. E. F. problems in particular that General March was brought back from France to fill that office and effect a reorganization. He did so with great speed and skill and effectiveness, but unhappily with such resultant enmities in Congress and with General Pershing himself as to forfeit much of the popular esteem which his brilliant and forceful labors deserved.10 These two outstanding figures of the 1918 Army had two opposed concepts of responsibility. General Pershing had gone abroad with authority which left no doubt that he was immediately responsible to the President as Commander in Chief, through the Secretary of War. It was equally clear that he was not subordinate to the Chief of Staff. More than a year later, under General Order 80, the new Chief of Staff became the "immediate advisor of the Secretary of War on all matters relating to the military establishment . . . charged by the Secretary of War with the planning, development and execution of the Army program," and took "rank and precedence over all officers of the Army." 11 It was a high authority that General March proceeded to exercise with respect to the entire Army organization in the United States and even with respect to the Assistant Secretaries of War; when their France-bound cables displeased him he "either tore them up or directed they be not sent." 12 Three thousand miles away, however, General Pershing continued to exercise the authority bestowed on him originally, and in a letter to Secretary Baker successfully resisted an attempt by General March to reduce that authority, to the end that the supply difficulties in the United States might be lightened.13 There was merit in both contentions, as there was in both contenders. General Pershing's needs were not only the normal needs of the field commander but those of a commander in a critical situation. He felt (as is the theme of his memoirs during this period) that influences among the French and English alike were seeking to have him relieved of the command in France, and that any lessening of his authority would do irreparable damage not only to him but to the A. E. F.; in particular he felt, and probably rightly, as

[60]

he wrote Mr. Baker, that "our organization here is so bound up with operations and training and supply and transportation of troops that it would be impossible to make it function if the control of our service of the rear were placed in Washington." Instead, General Pershing developed his own Services of Supply, A. E. F., under the highly competent Maj. Gen. J. G. Harbord who had been the Chief of Staff, A. E. F., before being given command of the Marine Brigade and later, the 2d Division. This efficient supply establishment provided a working liaison with Washington and also an experience that was to contribute mightily to the postwar planning of Staff and Army organization. General March's arguments, however, were so sound in principle, if not in immediate application to the 1918 emergency, that General Pershing himself in his invaluable constructive work in postwar Washington saw to it that the Chief of Staff should thereafter have the very powers that General March had asserted. It would appear that General Pershing was correct in his view as of that critical time and place, and that General March was correct in his view of the powers the Chief of Staff should have had long before, and thereafter did have.

As to the General Staff itself (luring World War I, there were similar convulsions in its composition, dictated by new necessity springing from new situations and from experience itself, and also dictated by views of changing Chiefs of Staff as to the proper mechanism for attaining results. The peacetime three-divisional Staff mechanism that General Wood had set up in 1910 went through the changes demanded by war, and in early 1918, just prior to General March's accession, it was reorganized with five divisions.14 These were named Executive, War Plans, Purchase and Supply, Storage and Traffic, and Operations. Experience showed that the third and fourth of these divisions could be combined to advantage, and they were so combined under the new Director of Purchase, Storage and Traffic, Maj. Gen. George W. Goethals, in an organization suggestive of the Army Service Forces in a later war. Later, General Order 86 (18 September 1918) set up a Personnel Branch in the Operations Division. General Order 80 likewise created as a separate division what had been a Military Intelligence Branch, hitherto a part of War Plans and later included in the Operations Division. Intelligence had already been accepted as a major element in General Pershing's Staff at GHQ, A. E. F., which General Pershing modeled closely and conveniently upon the French General Staff. This A. E. F. organization (in contrast with that in Washington) had five divi-

[61]

sions, G-1, Personnel and Administration; G-2, Intelligence; G-3, Operations; G-4, Supplies; and G-5, Training. It served as a model for the postwar General Staff in Washington, with changes suitable for peacetime whereby G-3 and G5 were combined, and a fifth division, War Plans, took on the new duties of planning against future wars.

The task of reorganizing after World War I the Office of the Chief of Staff and the General Staff and the War Department itself was a sobering experience for the professional Army. It could not be undertaken without recognition that the organization existing up to 1917 had failed to meet requirements,15 and that in fact it was not the Army and the Staff in Washington, so much as it was the civilian Secretary of War, Mr. Baker, and his civilian advisers, who had driven through the reorganization of February 1918.16 That the Staff had been fearfully handicapped by restrictive legislation in peacetime has already been pointed out, but it does not appear that the Staff, fully utilized such opportunities as came its way. Attention must be given to the post-factum testimony of Maj. Gen. Johnson Hagood, one of the Department's severest critics although himself a member of the Staff in the years marked by his complaints. He recalls that on one occasion he presented General Wood with a sheaf of Staff memoranda. "I suggested that he select at random roc, of these . . . and predicted that none of them would bear upon any question relating to war and that no more than three of them would bear upon a question of any consequence in relation to peace or war. He did so and found my prediction true." 17 Granting that the facts lost no color in General Hagood's accomplished recital of them, his eminence in the Army and Staff and his record of achievement warrant attention to his severe postwar judgment that

. . . the fourteen years, 1903-17, during which the General Staff had been in existence had not been spent in making plans for war, the purpose for which it was created, but in squabbling over the control of the routine peacetime administration and supply of the

[62]

Regular Army and in attempts to place the blame for unpreparedness upon Congress . . . . Our unpreparedness did not come from lack of money, lack of soldiers, or lack of supplies. It came from lack of brains, or perhaps it would be fairer to say, lack of genius . . . .

The whole General Staff and War Department Organization generally fell like a house of cards and a new organization had to be created during the process of the war . . . . Why, seeing these things, did I not do something to correct them? The answer is that I did not see them, or seeing them did not understand. Hindsight is better than foresight.18

It was the completeness of the 1917 debacle, as clear to the civilian as to the military, that influenced the completeness of the 1920 change. In impressive contrast was the success attained by the A. E. F., and this contrast encouraged the adoption of the A. E. F. set-up, wartime creation though it was, as the model for a peacetime Staff in Washington. At the head would be General Pershing himself, followed by a succession of men who had been his trusted lieutenants in France. It was the experience of 1918 that dictated the very composition of the new General Staff. The whole Staff concept, for years to come, was that a new war would be a simulacrum of 1918.

The National Defense Act of 1920 was by no means what the Army wished, as expressed in General March's recommendations, transmitted by Mr. Baker with modifications of his own. The request had been for a General Staff of 226 officers; the grant was of 93 at Washington, but with no limit imposed on the number of Staff officers with troops. The function of the General Staff in Washington was to remain deliberative rather than administrative, evidence of Congress' continuing suspicion of "militarism"; there was an abiding recollection of 1903 pledges that the General Staff was to concern itself with planning and co-ordination, and with "supervision" as distinguished from "command." The operating activities for the whole Staff (for a time designated as Operations, Military Intelligence, War Plans, Supply) were set forth.19 A significant and lasting reform gave to the civilian Assistant Secretary of War supervision of the procurement of supplies and equipment (not their design or calculation). It recognized the extremely useful work of Mr. Baker's Assistant Secretary, Benedict Crowell, in bringing order from 1917 chaos, and in the permanent organization of 1921 made the Assistant Secretary's office legally responsible for procurement. Upon the energy and capacity of that official, guided by the planning of the General Staff and eventually supported by President and Congress, thereafter depended the progress the Army should make toward

[63]

preparedness. In these important respects the Harbord Board's recommendations, warmly supported by General Pershing and accepted by the Secretary, provided a basis for General Staff thinking for years to come. The Staff's setup, therefore, during almost the whole interval between World War I and World War II, can profitably be examined in order to understand how the Army did its planning.

Army Regulations 10-15, affecting the General Staff, as of 1921 went through only minor revisions until early 1942. They included the following specifications:

The Chief of Staff is the immediate advisor of the Secretary of War on all matters relating to the Military Establishment and is charged by the Secretary of War with the planning, development and execution of the military program. He shall cause the War Department General Staff to prepare the necessary plans for recruiting, mobilizing, organizing, supplying, equipping and training the Army ["of the United States" was later inserted] for use in the national defense and for demobilization. As the agent, and in the name of the Secretary of War, he issues such orders as will insure that the plans of the War Department are harmoniously executed by all branches and agencies of the Military Establishment, and that the Army program is carried out speedily and efficiently. 20

To this was added in the revision of 18 August 1936 the following significant paragraph

[He] is in peace, by direction of the President, the Commanding General of the Field Forces and in that capacity directs the field organization and the general training of the several armies, of the overseas forces, and of the G. H. Q. units. He continues to exercise command of the field forces after the outbreak of war until such time as the President shall have specifically designated a commanding general thereof. 21

The authority conveyed in the 1921 version's first sentence, for the "planning, development and execution of the military program," appears to be all-inclusive, and almost certainly was so designed by its framers, under the eyes of General Pershing. Under later Chiefs of Staff doubts appear to have arisen about the completeness of their control of the Army itself; whatever the doubts, they were resolved in 1936 by insertion in Army Regulations of the additional paragraph just cited, which puts into written form what presumably had been the intention of the 1921 planners. The precise legal authority for this assumption is not

[64]

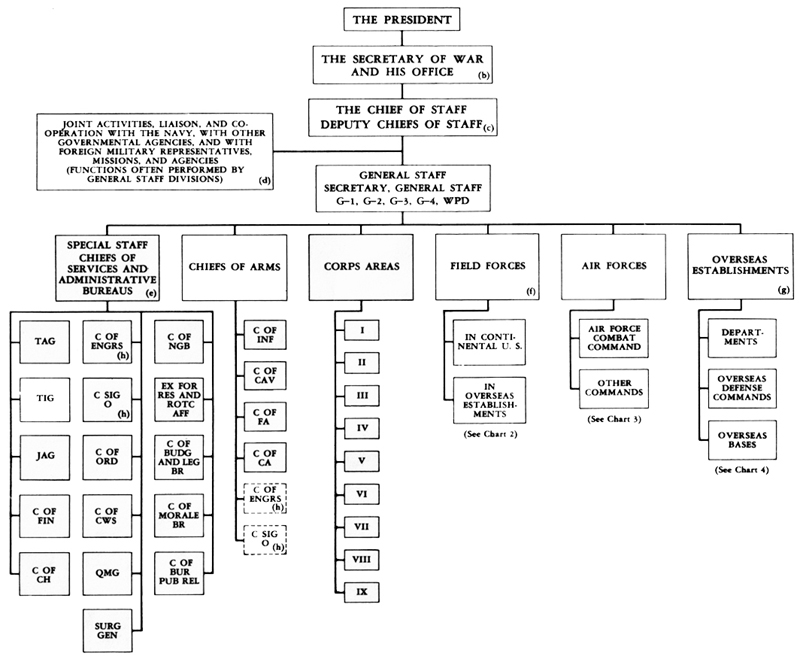

CHART 1.- CHIEF OF STAFF'S RESPONSIBILITIES: 1 DECEMBER 1941 (a)

(a) A simplified chart, necessarily incomplete, for graphic representation of major relationships. More detailed relationships are shown variously in Charts 2, 3, and 4. See also Greenfield, Palmer, and Wiley, The Army Ground Forces Organization of Ground Combat Troops, Charts pages 14, 18, 118, 120, and Otto L. Nelson, Jr., National Security and the General Staff (Washington 1946), Charts 7, 8 ff.

(b) Included Under Secretary and Assistant Secretaries

(c) Included three Deputy Chiefs of Staff, as follows:

1. For administrative matters and ground elements (less Armored Force).

2. For supply matters and Armored Force.

3. For air elements. Deputy Chief of Staff for Air was also Chief of the Army Air Forces

(d) Included participation on joint Board, United States-Canadian Joint Board for Defense, co-operation with British Mission, Lend-Lease, and other agencies.

(e) Included agencies of War Department reporting to the Chief of Staff directly or through the General Staff on administrative, supply, and service matters.

(f) The Chief of Staff was also Commanding General of the Field Forces. He exercised this command through GHQ, and, in the case of the Hawaiian and Philippine Departments, through the respective Department Commanders.

(g) Included administrative and supply elements and elements of the field forces, air and ground, assigned as protective garrisons.

(h) The Corps of Engineers and the Signal Corps were also classified as arms as well as services

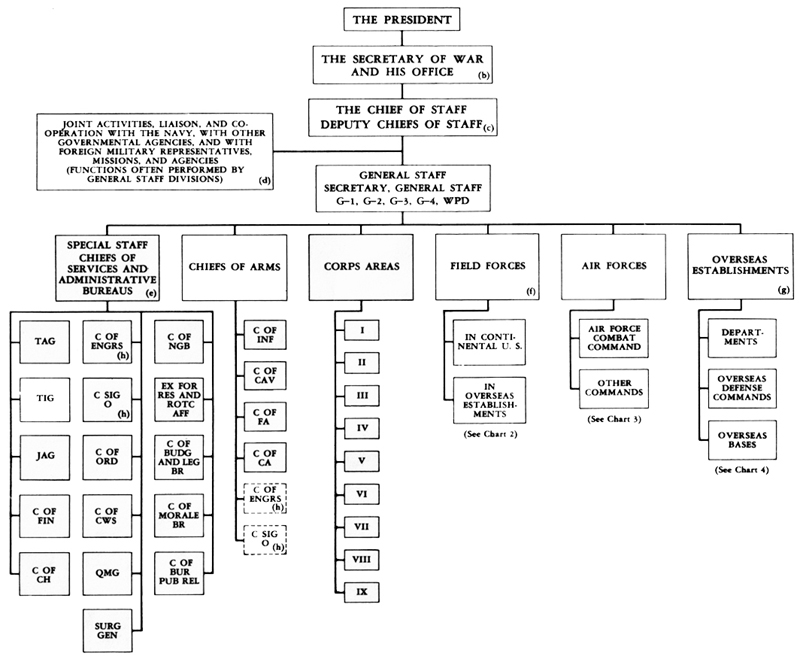

CHART 2.- CHIEF OF STAFF'S COMMAND OF THE FIELD FORCES AS EXERCISED THROUGH GHQ: 1 DECEMBER 1941

(a) Each army included its assigned corps (with component divisions and corps troops) and army troops.

(b) Each defense command in the continental United States included (as applicable) its component sectors, its harbor defense, its mobile ground troops (as assigned by army and corps), and its air force (when so directed by the War Department). The army commanders also served as commanding generals of the defense commands. Mobile troops for the defense commands were assigned from the armies, corps, and GHQ reserve. As applicable, defense commands were co-ordinated with naval coastal frontiers for co-operative action and joint defense operations.

(c) Included ground and air units specifically assigned to GHQ by the War Department as a reserve.

(d) Included special forces set up under GHQ by War Department direction for particular tasks and missions.

(e) GHQ direct supervision was confined to the armored divisions and separate tank battalions of the Armored Force-it did not exercise control or supervision over organization, school or replacement matters, which were under the Chief of the Armored Force who reported to the War Department.

(f) See also Chart 4.

(g) Included Alaska.

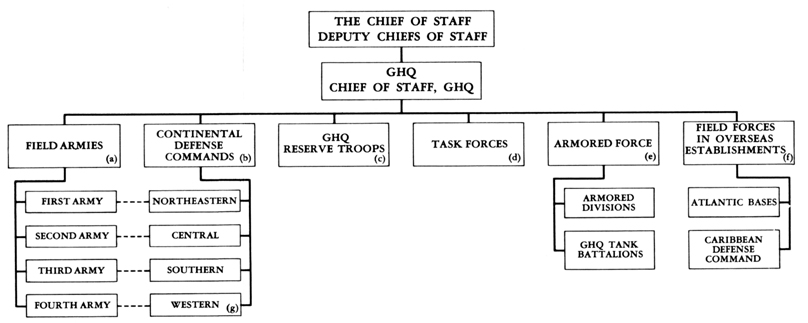

CHART 3.- EXERCISE OF THE CHIEF OF STAFF'S COMMANDS OF THE ARMY AIR FORCES: 1 DECEMBER 1941 (a)

(a) A simplified chart showing only major relationships, with detail omitted.

(b) Chief of Army Air Forces was also Deputy Chief of Staff for Air. He exercised his command of the Air Forces through his own Air Staff.

(c) Commanded the tactical air forces in the continental United States. Air units sent to overseas establishments came under the command of the commander of the area to which they were assigned.

(d) Each air force included its interceptor, bomber, air support, and air force base commands.

(e) Specially organized for the support of armored forces.

(f) Included air service areas and air depots.

(g) Included procurement and development.

(h) Included inspection, personnel, legal, medical, and fiscal affairs, buildings and grounds.

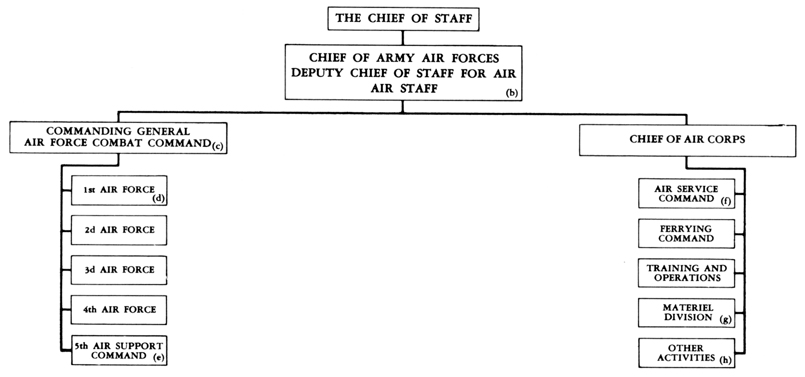

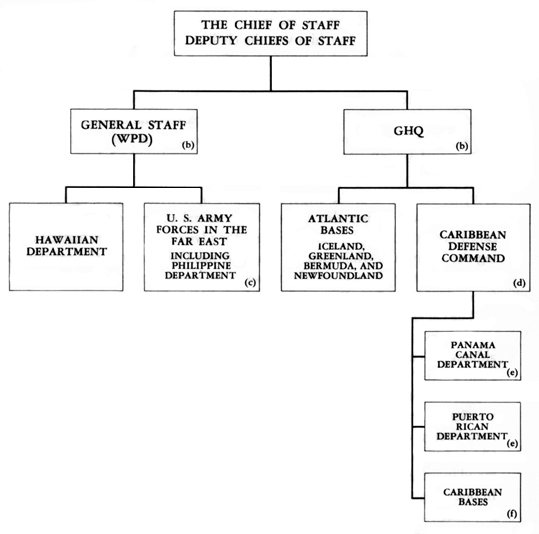

CHART 4.- EXERCISE OF THE CHIEF OF STAFF'S COMMAND OF OVERSEAS ESTABLISHMENTS, INCLUDING DEPARTMENTS, DEFENSE COMMANDS, AND BASES: 1 DECEMBER 1941 (a)

(a) A simplified chart showing only major relationships, and omitting detail.

(b) In the case of the Hawaiian and Philippine Departments, the Chief of Staff exercised command directly through the Department Commander, via his General Staff. WPD was the General Staff division primarily concerned with overseas departments. Command of the other establishments indicated was exercised through GHQ as of 1 December 1941. In a number of activities, such as supply, construction, etc, GHQ dealt through the General Staff divisions in the exercise of its control over overseas establishments. The departments, defense commands, and bases indicated included supply, administrative and tactical elements, including field force units for protective garrisons, both ground and air.

(c) At this time the Philippine Department was part of a larger command, United States Army Forces in the Far East, Gen. Douglas MacArthur being Commanding General of both.

(d) Activated in February 1941, to place the Panama Canal and Puerto Rican Departments and all bases protecting the approaches to the Panama Canal under a unified command. The command was placed under GHQ on 1 December 1941. The Caribbean Defense Command and its component organizations were co-ordinated with the naval sea frontiers for co-operative action and joint defense operations.

(e) Organized as Puerto Rican Sector and Panama Sector for unified tactical defense within the Caribbean Defense Command-administered as departments for supply. Lt. Gen. Frank M. Andrews was Commanding General of both the Caribbean Defense Command and Panama Canal Department.

(f) These bases included the United States Army establishments in the Bahamas, Trinidad, St. Lucia, Jamaica, Antigua, British Guiana, Surinam, Curacao, and Aruba.

[65]

quotable, but the large powers of the Chief of Staff over the entire Army were not openly questioned thereafter.

The Chief of Staff was the military chief of the War Department, but not its highest authority. Over him was the civilian Secretary of War who, in the wording of Army Regulations of that time, "directly represents the President . . .; his acts are the President's acts, and his directions and orders are the President's directions and orders." 22 The Secretary's approval was required on all matters of Army policy and in his name departmental decisions were made and actions taken. To both the President and the Secretary of War the Chief of Staff was adviser (President Roosevelt's executive order of 5 July 1939 provided immediate contact between White House and the military chiefs of Army and Navy in the realms of "strategy, tactics and operations"). By long established custom, he was adviser also to the Congressional committees which naturally called upon the Army's principal figures for advice on legislative matters affecting the Army, and while General Marshall was Chief of Staff this relationship was particularly close. Similarly he was a principal Army spokesman in conferences with the State Department and other branches of government at need.

The Chief of Staff's occupation, of course, was in the control of all the Army's activities as summarized in the Regulations. This control was not questioned, although General Marshall was never designated formally as "commander of Field Forces" and never asked to be. Control was exercised largely through the five sections of the General Staff which, with Deputies and Secretary of the General Staff, composed the "Office of the Chief of Staff." Under this office, which must be regarded as a unity functioning in the name as well as the interest of the Chief of Staff himself, the Army was directed through specified chains of command indicated broadly in Chart 1, portraying the set-up as of 1 December 1941. In one category immediately below the Office of the Chief of Staff were all the branches that provided the supplies of the Army (Quartermaster Corps, Ordnance Department, etc.) and all the bureaus that performed its administrative functions (such as Adjutant General, judge Advocate General, and Finance Division), these making up the Special Staff as distinguished from the General Staff. In another category were the chiefs of the several combat arms (Infantry, Field Artillery, and so on). In another were the nine corps areas into which continental United States was divided (the corps areas by this time being concerned with supply and administration rather than with tactical command). In another cate-

[66]

FOUR DEPUTY CHIEFS IN THE LATE PREWAR PERIOD

|

Maj. Gen. Stanley D. Embick |

Maj. Gen. Richard C. Moore |

|

Maj. Gen. William Bryden |

Maj. Gen. H. H. Arnold |

[67]

SECRETARIES OF THE GENERAL STAFF IN THE LATE PREWAR PERIOD

|

Lt. Col. Robert L. Eichelberger |

Lt. Col. Harold R. Bull |

|

Col. Orlando Ward |

Brig. Gen. Walter B. Smith |

[68]

gory were the field forces, of which the Chief of Staff of the Army had been the designated commander since 1936. In another were the overseas establishments. In another the Air Forces. The last three categories were themselves divided in so complex a manner as to call for portrayal in separate charts, 2, 3, and 4. It was the confusing character of the command arrangement in these echelons, difficult even to chart in a wholly logical arrangement, which, not unnaturally, aroused discontent with the General Staff organization and in late 1941 led to the declaration that reorganization would be necessary. Whether or not there was compelling need for so complete a rearrangement of controls as came about was disputed, but this new setup was decreed in March 1942.23

The graphic charts (1-4) suggest rather than portray the manner in which the Chief of Staffs large responsibilities were delegated throughout these various categories and areas of command. The immense labors that he performed in person are not as readily portrayed by charts as by a record of the major events in which he was a principal actor. The mechanisms whereby the Office of the Chief of Staff functioned, however, are discernible in its composition and in the recital of responsibilities allotted to its several elements.

These elements in the years just before World War II included the Deputy Chief of Staff (to the one deputy listed in 1936 Army Regulations two more were added later), the Secretary of the General Staff, and the five Staff Divisions. The duties of the original single Deputy were recited in the regulations, thus: "The Deputy Chief will assist the Chief of Staff and will act for him . . . will report directly to the Secretary of War in all matters not involving the establishment of military policies." 24

The Deputy Chief was particularly charged with legislative and budgetary matters, and also with general supervision of all the General Staff Divisions. Oddly, from 1921 until 1939 this important office had no statutory basis for existence, even a 3 June 1938 amendment to the National Defense Act of 1920 having failed to correct the omission. The office was established administratively in 1921 to meet an obvious need but only in March 1939 did G-1 make recommendations effecting the change- and then apparently because of the necessity of assigning

[69]

to the Deputy's post one of the "88 other officers" to which the General Staff was limited. General Craig, then Chief of Staff, supported the recommendation, likewise stressing his reluctance "to assign an officer to the position from among the limited number authorized for the performance of the detailed work of the Staff," and in July 1939 Congress provided legal authority for the Deputy's appointment.

The same bill effected another long-delayed correction to which the G-1 memorandum also had invited attention. The 1920 act had created a General Staff of four divisions (G-1, G-2, G-3, and G-4), each under a general officer of the line. When the Staff was reorganized on 1 September 1921 the War Plans Division was added, but there being no legal authority for the assignment of a fifth general officer one of the five divisions, of necessity, had to be headed by a colonel. Except during short periods thereafter this was the lot of the Intelligence Division (G-2) whose chief was thus inferior in rank to the other four Assistant Chiefs of Staff, to his opposite number in the Navy, and to a number of foreign military attaches with whom he had frequent dealings, an embarrassment which it was possible to end only in 1939.25

The administrative work of 1940 became so overpowering as to exceed the capacity of the existing Deputy Chief of Staff, and not only was a second deputy created but, in an attempt to meet the special needs of the growing air establishment, an additional acting deputy was added in the person of the Chief of the Air Corps. General Marshall defined the fields of activity for these three so as to grant to one deputy concern over studies and papers on all personnel matters (except in air and armored components); training, organization, and operations of ground components (except armor); all other Staff matters not allotted the other deputies. The other deputy was jointly responsible in personnel matters for the Armored Force; he was solely responsible for studies and papers on training, organization, and operations of armor and for those on construction, maintenance and supply (except air), transportation, land acquisition, and hospitalization; for a time he handled Air Corps co-ordination too.

[70]

The acting deputy collaborated with the first-named deputy on air personnel papers, and was solely responsible for papers on all other matters touching the air component. For several months the three deputies or their representatives met in daily conference for a joint examination of Staff papers, partly to keep each informed on the other's work, partly to expedite necessary concurrence.26

The Secretary of the General Staff

The Secretary of the General Staff was concerned with records and paper work and with the collection of statistical information of military importance.27 In point of fact he usually did for his chief a great deal of analysis, liaison, and administration, repeatedly functioning much as a deputy chief of staff, serving as a link between Staff and Line and War College and Schools, preferably with a self-effacement that averted resentments. He had to have a stupendous memory in order to keep abreast of all these streams of Army plans and operations. It was inevitable that for such a confidential position secretaries would be selected on the basis of high military qualifications, and that some of them would be transferred to important duties in the combat theaters.28

The War Department General Staff as a whole was "charged with preparation in time of peace of the plans outlined" as the Chief of Staff's responsibility, and in a national emergency

with the creation and maintenance of the necessary and proper forces for use in the field. To this end it will, under the Chief of Staff, coordinate the development in peace and war of the separate arms and services so as to insure the existence of a well balanced and efficient military team .... The divisions and subdivisions of the War Department General Staff will not engage in administrative duties for the performance of which an agency exists, but will confine themselves to the preparation of plans and policies (particularly those concerning mobilization) and to the supervision of the execution of such plans and policies as may be approved by the Secretary of War.29

[71]

One may note in the last quoted sentence the traditional limitation of the General Staff to plans and policies and supervision in just those words, with one significant exception: administration was specifically barred in those duties "for the performance of which an agency exists." By implication it was permitted elsewhere. Here was a crevice in the ancient wall of Staff limitations. During World War II it was to be widened by WPD, and eventually all the Staff sections were to be headed by "directors," and the Staff functions were to become largely directive, rather than solely planning and supervisory. Further in this same section of the regulations, after a formal naming of the Personnel (G-1), Military Intelligence (G-2), Operations and Training (G-3), Supply (G-4), and War Plans Divisions, it was specified that WPD "will, in the event of mobilization of G. H. Q., be increased by one or more officers from each of the other General Staff divisions, so as to enable it to furnish the nucleus of the General Staff of G. H. Q. 30 This specification was in line with the concept previously noted, of a GHQ which in the event of war would move off to war under command of the officer who was currently Chief of Staff, unless otherwise directed by the President. (This concept was not altered officially, although many officers felt it was sure to collapse on war's arrival, reasoning that the field command would be given to someone younger than the Chief of Staff was likely to be.)

Duties of the Five Assistant Chiefs of Staff

The normal duties of each of the five divisions were set forth in detail, and to make clear their normal functioning as planning and supervising bodies only, not as operating commands, each division was allotted the "preparation of plans and policies and supervision of all activities." Personnel (G-1) was concerned specifically with

Procurement, classification, assignment, promotion, transfer, retirement, and discharge of all personnel of the Army of the United States (which includes Regular Army, National Guard, Organized Reserves, Officers' Reserve Corps and Enlisted Reserve Corps).

Measures for conserving manpower.

Replacements of personnel (conforming to G-3 priorities).

Army Regulations, uniforms, etc.; decorations.

Religion, recreation, morale work (by agreement with G-3), Red Cross, and similar agencies.

Enemy aliens, prisoners of war, conscientious objectors.31

[72]

The allotments to Military Intelligence (G-2) were:

Military drawings and maps.

Military attaches and observers.

Intelligence personnel of units.

Liaison with other intelligence agencies.

Codes and ciphers.

Translations.

Public relations and censorship 32 (both of which were to be elsewhere allotted before or during World War II).

The allotments to Operations and Training (G-3) were:

Organization of all branches of the Army of the United States.

Assignment of units to higher organizations.

Tables of allowance and equipment so far as related to major items.

Distribution and training of all units.

Training publications.

Military schools and military training in civilian institutions.

Consultation with G-4 and WPD on types of equipment.

Priorities in assigning replacements and equipment.

Troop movements.

Military police.

Military publications. 33

The allotments to Supply Division (G-4) were:

Basic supply plans to enable the supply arms and services to prepare their own detailed plans.

Distribution, storage, and issue of supplies.

Transportation.

Traffic control.

Tables of allowance and equipment (in concert with G-3 and WPD).

Inventories.

Procurement of real estate. Construction and maintenance of buildings.

Hospitalization.

Distribution of noncombat troops (in concert with G-3).

Property responsibility. 34

[73]

The allotments to WPD were as follows:

Plans for use in the theater of war of military forces, separately or in connection with the naval forces, in the national defense.

Location and armament of land and coast fortifications.

Estimate of forces required and the times needed.

Initial strategic deployment.

Actual operations.

Consultation with Operations, Training and Supply Divisions on major items of equipment.

Peacetime maneuvers.35

The theory was that all five of these sections or divisions were on even level, and this theory was restated from time to time to smooth the feelings of the various G's when WPD assumed superiority. Yet that superiority, which had formal recognition only late in 1941, was implicit from the beginning. It was suggested in the statement of ultimate duties that on the approach of war WPD would supply the new General Headquarters with a nucleus of its personnel. This could mean only that this personnel would be the principal advisers of the Chief of Staff in the event of his becoming the field commander whom GHQ would serve; it was natural that in peacetime this same personnel would be looked to by him for advice. If its potential responsibility was to be high, its current preparation for responsibility would be high, and on that assumption its personnel would presumably be selected for exceptional merit. 36 As a planning body it had to be informed of the Chief of Staff's complete wishes, and also of the supply and mobilization possibilities in fullest detail. The first relationship stimulated the second, and the second relationship was designed to give WPD the exact information needed for its labors in planning. Thus WPD in the end had to have all the data that had been or could be assembled separately by the several G's. It had, for effective planning, to do a good deal of co-ordinating among the G's, and also between line units and supply branches, and also between one departmental command and another. In 1936 Brig. Gen. Walter Krueger noted that in war there would be need for "a group in the General Staff capable of advising the Chief of Staff on broad strategical aspects." 37 When General Strong

[74]

was Chief of WPD in 1939 he remarked: "There is not an activity of the War Department . . . that does not tie in with the work of the Division." 38 It is not surprising therefore to find a maximum of the larger problems of the Army, even before Pearl Harbor, being referred by the Chief of Staff to WPD for study, or being invited to the Chief of Staff's attention by the current head of WPD.

The routine coordination of the several divisions was one of the functions of the Deputy Chief of Staff, who for this and other purposes made use of a General Council made up of himself, the Assistant Chiefs, and the executive officer for the Assistant Secretary. When the discussion was to include matters of interest to The Adjutant General and the chiefs of arms and services, temporary membership in the General Council was extended to include them.

All-inclusiveness of the Chief of Staff's Responsibility

It is apparent both from the all-inclusive language defining the Chief of Staff's powers, and from the language reciting the detailed functions of his advisers and assistants, that by this written authority as well as by growing tradition the Chief of Staff was accountable in some degree for almost everything that was done or not done by the Army. His enormous responsibilities, however, were not balanced by the power to fulfill them, and could not be. His policy recommendations had to meet the approval of his superiors, the Secretary and the President. His plans had to be implemented by Congressional authorization and appropriation, and it will be seen that even on the brink of war these requisites were not always fulfilled.

Precisely where the Chief of Staff's immediate responsibility began, as far as the Staff duties were concerned, is difficult to define for the reason that the Staff officers functioned not as individuals but as agents for the Chief of Staff. Their relationship to him is discussed in a great many texts including, notably, those of Maj. Gen. Otto L. Nelson, Jr., and Brig. Gen. John McAuley Palmer,39 but seldom more understandingly than by the latter in his discussion of the General Staff as properly "the General's Staff"; by that concept the Staff officers are the aides of the General, doing for him what he would do for himself if he had time and facilities. The aid that the Chief of Staff habitually received from his assistant chiefs and from the latter's subordinates is indeterminable

[75]

from the record, just as comparable aid is indeterminable in the management of any large industrial enterprise. A general superintendent who is in theory responsible for all operations gives oral orders to his juniors and receives from them supplemental or corrective advice, likewise oral, which time may show to have been the factor determining success or failure. Yet the record of these communications, too, is nonexistent.

How Staff Divisions Functioned

This constant interchange of instruction and advice within the General Staff and among the arms and branches is not fully evident in the written records of Staff activities. Examination may disclose, for instance, without related papers, a momentous recommendation signed by a chief of section that was forwarded intact to the Navy prior to Joint Board consideration, or to the Secretary of War and thence to the President leading to its eventual enunciation as a military policy. That single document can be misleading as to responsibility, and will remain so until there is access to related papers that would disclose a succession of previous events. To illustrate, the matter at issue can have originated with an unnamed officer in a subsection and risen by stages to the section chief's attention. Or it can have originated with the Chief of Staff himself or with higher authority, by whom it was passed down to the section chief for study and recommendation, and by him passed further down to the appropriate subsection. Whatever the document's appearance, it certainly did not burst suddenly from the brain of the signer of record. Rather, it normally was the result of days or weeks of thought by a number of officers in a number of offices. In a fairly typical case, a subject of military concern makes its first appearance in Staff papers as a memorandum or a note of an oral communication, sometimes direct from the Chief of Staff, more often from the Deputy Chief or from The Adjutant General, or from the Secretary of the General Staff, one of whose duties was the informal "farming out" to appropriate Staff sections of such ideas as the Chief of Staff wished explored by those specialists. Frequently the suggestion was given orally at a routine conference or at an impromptu meeting with no precise instructions and apparently with no clear purpose beyond a desire to have a broad subject explored for its military possibilities.

In preliminary stages of planning the Staff sections were equally informal. Thus, G-4 made many oral inquiries direct to the separate supply services before

[76]

bringing a subject to the general attention of the Staff; some of these inquiries appear to have risen previously in the mind of the Chief of Staff or to have been brought to his attention from outside his establishment. Where the record of a study is complete, it becomes obvious that, once the original suggestion was fully explored within one of the Staff or service sections, it was immediately exposed to criticism and correction by others. It moved up the ladder for approval and down for revision. It was referred to conferences for concurrence and in cases of nonconcurrence (which were frequent) it was sent back for further study. The typical routine of such a study was prolonged, but it was thorough, and it was designed to delay the making of a final, formal recommendation until all available objections to it had been heard and overcome. If the subject was important enough to justify the close attention of the Chief of Staff, the papers usually moved with celerity.

It is for this reason that the activities of the Chief of Staff as an individual are not clearly delineated in the record, but invisibly overflow the notations, infinitely influenced from above and below. The actual origin of a fully considered proposal is usually beyond determination even by those who participated in making it. The thing in question was done (or left undone) not by an individual but by a multiminded unity known as the Office of the Chief of Staff, and often one can focus responsibility no more closely than that. For the final decision the Chief of Staff in person as signing authority must reasonably be held accountable, but with the observer's awareness that the Chief of Staffs actual responsibility often was shared with a great many others.

Numberless suggestive illustrations might be mentioned. Thus, in noting General Marshall's recurring prewar efforts to reconcile the views of the Ground Forces and Air Forces, 40 and to provide the latter with what can be called controlled autonomy, which was among his most significant achievements, one must observe that in this period his Assistant Chief of Staff for Operations (G-3) was Maj. Gen. (later Lt. Gen.) Frank M. Andrews, not only a distinguished aviator but the first aviator to hold that high post in the Army's General Staff. General Andrews, whose death in an airplane accident early in the war ended a career of large accomplishment and larger promise, was a proved believer in co-operation; the influence of such an adviser on such an issue can hardly have been negligible, however fragmentary are the written records.

[77]

General Marshall's frequent contacts with General Embick (whose capacities had qualified him as interim consultant for Mr. Roosevelt on a notable occasion dealt with in Chapter XII) may be presumed to have had an influence transcending that which appears in the record. The same can be surmised of General Strong with whom as chief of WPD and later of Intelligence there were numberless discussions; of General McNair of the 1940-42 GHQ; of Maj. Gen. Henry H. Arnold of the Air Forces; of numerous other frequently seen authorities of Staff or Line. But the responsibility for a judgment reached, a policy fixed, an action ordered, a critical step taken (or not taken) on time and in the right direction often can be attributed only to the widely inclusive Office of the Chief of Staff, where official responsibility lodges for the bold decision and the large achievement or, equally, for the dubious one, the delay and the undisguisable mistake.

With the increasing complexity of warfare, the things that the high command of a large army has to know, or know about, have taken on great number and great variety. They involve not only basic military matters of organization and equipment and tactics and strategy, but technical, mechanical, political, economic, scientific, and psychological factors, in the United States and abroad, in degrees that call for specialized knowledge beyond the powers of one man. They involve also administrative machinery in numerous echelons, and there is a resultant problem of how the essential information can be so strained and channeled as to reach the high command in the desired form and amount, and also how the essential controls are to be exercised so as to attain maximum speed and efficiency. A considerable administrative betterment in the original organization had been effected in 1926 when the Assistant Secretary's office initiated a study of long-range equipment needs that would permit standardizing (by the General Staff), cooperation with the Navy in corresponding effort, and resultant planning of procurement (by the Assistant Secretary's office) on a much more efficient basis than by the earlier system of divided responsibility.41 It was a prolonged struggle but it was rewarded in 1937 by the completion of the Protective Mobilization Plan which-although not sufficiently projected into the future-at least set forth the nation's initial defense requirements as then seen, in terms of manpower and equipment and organization. The PMP force was a long time coming, but the objective now was defined and, even though it was not quickly attained, the General Staff's planning thus early was of incalculable value in assuring its ultimate attainment.

[78]

The "Joint Board" of Army and Navy

Those phases of planning which called for coordination with the Navy were carried on through mechanisms that were set up as continuing bodies but that, not unnaturally, functioned chiefly when there was something specific to do. The Joint Army and Navy Board, usually referred to as the Joint Board, was the high instrument of this coordination and so remained until in 1942 it was superseded, in practical effect, by the joint Chiefs of Staff. It was originally created in 1903 by agreement of the Secretaries of War and Navy 42 but it had suspended meetings, oddly, in 1913 and 1914 when World War I was about to start; it renewed its meetings in October 1915, and was formally reconstituted by new orders at the end of that war.43 In its new creation the Chief of Staff, Chief of G-3, and Chief of WPD made up the Army component; their colleagues were the Chief of Naval Operations, the Assistant Chief, and the Director of Navy's WPD. Later the Army's G-3 was replaced on the board by the Deputy Chief of Staff. Both Army and Navy eventually added their chief air officers as representatives from their own air arms.44 Matters of munitions supply requiring coordination to prevent wasteful duplication and competition were handled by the Army and Navy Munitions Board operating with a civilian chairman. Matters of co-ordinated policy and planning were the functions of the Joint Board. It was consultative, and advisory to the Commander in Chief, not executive, and positive action came only when it was required. Under these circumstances it can be seen that there was not always unanimity-indeed that for such purposes unanimity was not necessarily a virtue; the power of decision was the President's.

There was no requirement for monthly meetings of the Joint Board if need for them did not exist, and even in the winter of 1939-40, with Europe's armies deployed for war, there were no meetings between 11 October and 21 February; there were none in March 1940, nor in August. None were necessary because there existed an active and useful adjunct called the Joint Planning Committee, made up of the two services' War Plans chiefs and their first assistants. This committee met much more frequently and, with full understanding of the views of

[79]

superiors, threshed out difficulties and came to tentative agreements which then, if necessary, could be laid before the joint Board for formal approval. In practice, the "serial" (or subject under consideration) on which agreement had been reached was then "canceled" by the board as finished business with no discussion beyond that which had already taken place in the committee. Points on which the committee could not agree were laid before the Joint Board, sometimes settled there, sometimes returned to the committee for further study under new instructions, sometimes laid before the President for decision. In May 1941 the planning chiefs' assistants were assigned to a "Joint Strategical Committee" to thresh out details of joint war and operating plans for their chiefs, and in much the same manner come to agreement on a program for submission to the Planning Committee and ultimately to the board. Other planning matters normally were referred to ad hoc subcommittees of the Planning Committee and similarly expedited.

In late 1940 the senior body's meetings became much more frequent, being called at need to consider matters which would not await delay. Weekly meetings were formally established on 2 July 1941. The meetings developed discussions of questions which thereupon were turned over to committee for tentative agreement, or they were disposed of on the spot as far as joint policy was concerned, so that each service could proceed with its own planning in the field under discussion. Thus at the February 1940 meeting there were discussions, without vote, upon the respective services' duties and responsibilities in connection with harbor mines, with underwater listening devices, with interservice communications, and other matters with regard to the proposed joint exercises 45 After general views were indicated, particular agreement was left to the Planning Committee. There also was on this same occasion a discussion of "increasing Army Air and Navy Aviation in the Philippines . . . as an additional deterrent to Japanese expansion" and mention that "Japanese control of the Dutch East Indies would involve 90% of the United States' rubber and tin supply." Also, two months before the burst of Blitzkrieg, there was new consideration of a memorandum that on 10 November 1939 (there had been no Joint Board meeting between October and February) General Strong, the Army's WPD chief, had written to the Chief of Staff to point out the potential usefulness of Trinidad for hemisphere defense.46 The Navy pointed out that further development of Alaskan bases at Sitka and Kodiak called for further

[80]

defense installations by the Army. 47 This is a fairly typical recital of the board agenda at the meetings of the period. The discussions produced agreement on a great many issues. They did not result in action on all issues, nor did the discussions of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and its created committees, which in the 1942 reorganization took over the work of the joint Board and its elements and continued to function throughout the war by unanimity or not at all.

Was the Prewar Staff Effective?

That the Army's Staff and Command organization of 1921, as revised piecemeal in the next twenty years, was still unsuited to great emergency is pointed out bluntly by General Nelson.48 He lists sixty-one separate officials of the Army and War Department who in 1941 had theoretical access to the Chief of Staff; in addition there were necessary and desirable contacts of frequent occurrence with the Navy (through the Joint Board), with the State and Treasury Departments, with the White House, with Congressional committees and individual Congressmen, with scientists and other nonpolitical visitors, and with certain foreign military attaches. Such numerous contacts by one man were impossible of maintenance, and the Staff of prewar days took over many of the Chief's obligations. Nevertheless the unwieldiness of the arrangement was one of the reasons cited for the complete Army and Staff reorganization, studied long before Pearl Harbor and finally effected in March 1942.

The rising emergency proved the old Staff organization unsound, not merely in its division of duties but in its stated restriction to "planning, policy and supervision." The Army mechanism was too vast to move without actual direction and command by the Chief of Staff himself. His Staff, or a part of it, would have to operate as well as plan. The planners' devising of a GHQ mechanism years before provided its own evidence of planners' preknowledge of the fact; but either the mechanism they devised or the personnel manning it was not adequate for the emergency. The Staff divisions had statutory power to supervise and advise activities but not to order them except by direction of the Chief of Staff, and this was generally sought by one of the section chiefs only after polite request

[81]

for concurrence by other sections affected. Exceptions to this routine were made only in emergency, and as late as June 1941 WPD complained that there was no normal machinery for "prompt decision and expeditious action" upon an issue.49 A General Staff which had passed 600 members in 1941 and which in the interest of the rapidly expanding field units had to make swift and binding decisions of a command nature, could not limit itself to "planning, policy and supervision" without serious sacrifice of efficiency in a time of national crisis. Accordingly, the decisions were made, with or without clearly stated authority. In General Nelson's words: "The War Department General Staff had to operate in 1941-indeed every section of it operated." 50 Had the authority been publicly questioned, which it was not, the defense of this untraditional action would probably have been found in the language of Army Regulations, I, 4, previously quoted, barring the Staff only from "administrative duties for which an agency exists"; patently there was no such agency visible.

The larger question of General Staff efficiency in prewar days is not merely a matter of mechanisms and technique, however. The Staff function was to plan and prepare for war on a sound basis of accurate information appropriately applied and to cope with the new problems of strategy and techniques which arise in a changing world. Later chapters will disclose varying degrees of accomplishment of their functions by all sections of the Staff, ranging from examples of exceptional foresight to examples of extraordinary dullness of perception, from contagious energy to inexplicable lethargy. Neither information nor its application was impeccable. Estimates of foreign powers' capabilities and intentions were often far from right. There were inaccurate estimates of America's own capabilities, a notable example being in the plans for mobilization of the Ground Forces treated at length in other volumes of this series; 51 the plans met with repeated corrections and delays because of embarrassing conflicts with manpower needs for Air Forces, for Navy, and for industry. The Army's ambitious plans for the early raising of large troop units had to be altered radically because of belated discovery that weapons and other equipment that these units would require could not be supplied by industry until many months after the date proposed for recruitment of the troops. 52 Indeed a large part of the difficulties that beset the War Department in its 1939-41 effort to build up the Army into a bal-

[82]

anced force in being, however small or large, was the shortage of equipment, thoroughly known to informed persons in Staff and services but surprisingly unfamiliar to others who most certainly should have been informed through proper Staff coordination among the materiel-minded, the personnel-minded, and the tactics-minded elements of that very Staff. There were impressive estimates of needs but the estimates were not converted into goods, and one of the purposes of ensuing discussion is to explore, rather than determine, the extent to which Staff, War Department, Commander in Chief, and Congress were responsible respectively for the delay in bringing about that conversion, and for that contemning of the time factor to which General Craig referred feelingly in his farewell message as Chief of Staff. 53

All aspects of military planning are mutually dependent, supply upon troop raising and troop raising upon supply, and both upon the nation's civilian economy in the several aspects of its manpower, industry, raw materials, transportation, power, and finance. Planning is useful only as it is informed and realistic and thorough and continuous. This is the basis of every planning system, and supposedly of performance too. The extent of the General Staff's responsibilities was clear enough. The pattern of the divisions' functions was explicit, and so was the plan for coordination and for direction. The method of educating industry, the design for industrial mobilization (responsibility for which the Assistant Secretary of War assumed under the 1920 Defense Act), the means of raising manpower, and the recruitment of skills had been considered long before the war, approved, and methodically set down in type.

Yet the halting and confused progress of rearming in 1939-41 showed that not enough progress had been made in translating plans into reality. The mutual relationships of all these tasks were not sufficiently understood by all members of the General Staff, much less by high civilian authority in government. As World War II approached, therefore, there was a lack of exact coordination in planning which, atop the paucity of appropriations discussed in Chapter II, gravely delayed performance. The task of the Chief of Staff and his greatly expanded office, when the United States was at length drawn into a war long in the making, was to do what should have been done earlier as well as what had to be done upon the opening of hostilities, and to do both with the greatest dispatch, now that time, too long squandered, was no longer available. The relentless pressure of necessity would accomplish in months what pleas and

[83]

arguments had failed to accomplish in years. It would do so at heavy cost in dollars and with errors in judgment which possibly, but not certainly, might have been avoided had there still been time for careful consideration of alternatives. The record shows the errors; it does not provide sure evidence that the alternatives would have been more profitable.

[84]

page created 13 March 2003