CHAPTER X

Alaska in the War, 1942

The slashing Japanese attack in the western and central Pacific in December 1941 opened the prospect of a more active military role for Alaska, especially if the Soviet Union became involved in the new Pacific war. Even before the Japanese struck, the United States had been hoping to obtain the use of Soviet air bases in the Vladivostok area, and, if Japan now attacked the maritime provinces of Siberia, the military collaboration of American and Soviet forces in the North Pacific appeared inevitable.

The Soviet Union, desperately involved against Germany in Europe, had neither the desire nor the resources for a two-front war if it could be avoided, although Marshal Joseph Stalin at first indicated that the Russians might be ready for some sort of positive action against Japan by the spring of 1942.1 As the new year opened, both General Buckner in Alaska and the military planners in Washington wanted to push the development of an air route through Alaska that would permit the operation of American aircraft from Russian bases against Japan, and President Roosevelt himself was keenly interested in the proposal.2 The President was also concerned about the danger of a Japanese raid on the new military installations in Alaska, more concerned, indeed, than were his military advisers. In mid-February he indicated his desire for a "complete plan" for establishing a striking force in Alaska and the Aleutian Islands and in pushing the execution of this plan as far as possible by midsummer.3

Taking into account the military situation in the western Pacific at the end of January 1942, the Army and Navy commanders in Alaska recommended a more specific plan for attacking Japan by way of the North Pacific. Noting that the other approaches to Japan were already protected by land

[253]

based aviation, they advocated the establishment as soon as possible of striking bases on the Siberian mainland and Sakhalin Island, and the development of a secure convoy route to the Russian naval base at Petropavlovsk on the Kamchatka Peninsula. Their plan would involve rushing work on the airfields already under construction in Alaska, improving the air route via Nome and across Bering Strait, and establishing a string of seaplane bases, to be protected by Army garrisons, in the Aleutians beyond Dutch Harbor and Umnak. It would also require a large air and ground reinforcement of Alaska, and immediate negotiation with the Russians to permit the development and use of Siberian bases.4

General DeWitt, in forwarding this proposal to Washington, concurred in its general concept, but he noted that the better part of a year would be needed to construct the facilities necessary for executing the plan and that, before Alaska could become a useful base for offensive operations, its successful defense must be assured. In Washington, Admiral King observed that the development of aviation facilities in Alaska was already well ahead of the ability of the War and Navy Departments to supply them with aircraft and that new and undefended air bases would be more of a liability than an asset. For the time being he was firmly opposed to the extension of aviation facilities in the Aleutians beyond Umnak, and indeed to any other preparations for offensive operations from Alaska until the Russians indicated a willingness to permit the operation of American planes from Siberian bases.5

While the plan of the Alaskan commanders for an offensive from Alaska was still under review, the President in early March asked for further study of the feasibility of opening the Aleutian route to Siberia, so that it could be used if Japan attacked the Soviet Union. 6 By March it was fairly evident that the Russians were not going to enter the Pacific war on their own initiative as long as they were heavily engaged in Europe, and therefore that they were very unlikely to give the Japanese cause for attack by opening their Far Eastern bases to American ships and planes, or even by letting Americans reconnoiter these bases as a step toward future offensive action from them. By the end of the month the Army and Navy had concluded, and so advised the President, that while the Alaskan air route via Nome might be used to deliver planes and other supplies to the Soviet Union, or to reinforce Russian air forces in Siberia if the Japanese attacked, it would be futile to do any more

[254]

planning toward these ends until the President was able to conclude an agreement with Marshal Stalin for military collaboration. General Buckner was informed that for the present his forces would have to remain on the strategic defensive and that he could expect only a modest augmentation of these forces and for defensive purposes only.7

Alaska became part of a designated theater of operations with the activation of the Western Defense Command on 11 December 1941, although under the restriction that General DeWitt as theater commander could not move major ground or air units from the west coast to Alaska without War Department consent. Before the month was over General Buckner had recommended that he be given unity of command over all military forces in Alaska, and the Army Air Forces had proposed that General Buckner be replaced by an Air Forces general officer since the Alaskan Defense Command area would be predominately an air theater so far as the Army was concerned. Neither proposal was approved, and the command of Alaskan forces remained unchanged until an active enemy threat developed in May 1942.8

At the outbreak of war the Army garrison in Alaska numbered about 21,500 officers and enlisted men. During the next five months this total nearly doubled, to a strength of 40,424 by the end of April 1942, considerably more than had been planned in the first wartime troop basis for the Alaska Defense Command.9 A considerable proportion of this total was accounted for by engineer troops needed to rush construction work at the new Alaskan air bases. Getting combat planes to these bases was a more difficult matter.

As noted in the preceding chapter, Alaska had no Army planes fit for combat when the Pacific war began. By 11 December a squadron each of modern pursuit and medium bombardment planes was being winterized for flight to Alaska, and the planes began to move at the beginning of January by way of the Northwest Staging Route of airfields built by the Canadians from Alberta northward. A number of these planes crashed en route, princi-

[255]

pally because of the inexperience of the pilots who flew them, and in early March only half the pursuits and a quarter of the bombers that had been sent were in shape for combat duty. The losses sustained in this emergency movement were primarily responsible for President Roosevelt's decision in early February to build a highway to Alaska by way of the airfields of the Northwest Staging Route.10

In response to General DeWitt's pleas for a much larger air reinforcement, the War Department in March announced plans for providing Alaska as soon as possible with five combat squadrons equipped with modern planes, two each of pursuit and medium bombardment and one of heavy bombardment planes. The actual strength in Alaska by the end of April was about a squadron each of pursuit and medium bombardment, and one B-17 heavy bombardment plane. These planes were all stationed at the Anchorage and Kodiak airfields and could not be moved westward to the new Alaska Peninsula and Umnak air bases then nearing completion without stripping the heart of the Alaskan military establishment of its means of air defense.11

The relative weakness of Army air forces in Alaska was compounded by slow progress in installing an aircraft warning service. In late 1941 the War Department had approved a plan calling for 20 radar sets so arranged as to guard all vital military installations in Alaska, but commitments to other areas after the fighting started made it necessary to reduce this number at first to 10 and in March to 5 sets. Brig. Gen. William C. Butler, commanding the newly designated Eleventh Air Force, was then called upon to submit a more modest air defense plan to match this allotment. General Butler pointed out that an integrated air defense of Alaska controlled from one headquarters was not feasible because of the large area to be protected, the many mountain ranges which form natural barriers and divide Alaska into isolated areas, and the lack of roads and internal communication networks. He proposed therefore to organize a series of self-sufficient local air defense areas for the protection of the more important airfields and bases. Air defense for other Alaskan installations would be provided after the defense of the three primary areas-Anchorage-Kodiak, Umnak-Dutch Harbor, Dixon Entrance-Sitka-and been insured. He therefore proposed to install the three detector sets en route at Sitka, at Lazy Bay on Kodiak Island, and

[256]

at Cape Wislow, Unalaska Island. One SCR-270 (mobile) was in operation at Anchorage and an SCR-271 was in operation at Cape Chiniak, Kodiak Islarid, at the time he made this proposal.12

A month later the War Department again increased the number of long-range radar sets to be allocated to Alaska to ten for planning purposes, and at the beginning of May General DeWitt reported a revised air defense plan for locating the detectors and establishing a central information center at Anchorage and ten regional filter centers to co-ordinate radar and pursuit aircraft operations. This was little more than a plan when the Japanese attacked in early June, and apparently the only radar operating at that moment was the one at Cape Chiniak on Kodiak Island.13 The arrival in May of four radar-equipped heavy bombers made offshore aerial patrols more efficient and gave the Army an alternate means of detecting enemy movements on the eve of the Japanese approach to the Aleutians.14

The Aleutian Islands extend in a long, sweeping curve for more than a thousand miles westward from the tip of the Alaska Peninsula. All of the islands are mountainous with no trees and little level ground suitable for the construction of airfields. From the shore line jagged peaks rise abruptly to an elevation of several thousand feet. The empty trough-shaped valleys are covered by tundra, a spongy mat of dead grass, on top of a layer of volcanic ash which when wet quickly churns into mud. Aleutian weather is notorious. Although the islands are not excessively cold, since they lie well below the Arctic Circle, rain, snow, and mist are the rule rather than the exception. These bare and almost unpopulated islands are also battered by violent winds and are hidden for much of the time in swirling fog.

On the globe the Aleutian chain appears to provide a natural route of approach toward either the continental United States or Japan. But the forbidding weather and wretched terrain made this seemingly natural route all but impracticable in 1942. Nevertheless, neither the United States nor Japan could afford to assume that the other would reject it as impracticable.

It will be recalled that the joint Board in late November 1941 had approved the construction of an Army airfield on Umnak Island, not only to

[257]

provide local air protection for the naval base at Dutch Harbor, but also for the broader purposes of blocking a Japanese advance toward the mainland and permitting the projection of Army air power into the more distant Aleutians. Army Engineers under the command of Col. Benjamin B. Talley began the construction of a runway at Otter Point on the northeastern end of Umnak in mid-January 1942 and soon thereafter undertook similar work on an intermediate base at Cold Bay near the tip of the Alaska Peninsula, where construction of an airfield had been started in 7941 by the Civil Aeronautics Administration. The Umnak base became the Army's Fort Glenn, and the Cold Bay base Fort Randall, with Fort Mears, the Army garrison for Dutch Harbor, in between. Both of the new fields were usable by 1 April, although just barely so. When the enemy approached two months later, Umnak had a garrison of about 4,000, Fort Mears of over 6,000, and Cold Bay of about 2,500, including engineer troops, but also including balanced complements of infantry and of field and antiaircraft artillery units. Generals Buckner and DeWitt had wanted a much larger combat force for the forward base on Umnak but had to be content with the 2,300 or so combat troops that the War Department had authorized.15

While the Umnak and Cold Bay airfields were being rushed to completion, the Japanese High Command was planning to attack and occupy points in the Aleutian Islands as part of their "second phase" offensive. By April Japanese planners had agreed on the main features of the operation. Japanese task forces were to undertake a two-pronged drive against Midway and the Aleutian Islands in the early part of June. Aside from its diversionary aspect to cover the Midway strike, the Aleutian phase of the operations was to be purely defensive. After capturing Midway and Kiska, the Japanese intended to use them as bases for an aerial patrol of North Pacific waters. The islands would also be outposts in a new defense perimeter that would be extended in due course to the Samoan and Fiji Islands and New Caledonia 16

The enemy knew little of American activities in the Aleutians since the war's beginning. The Japanese planners thought the United States had extensive military installations at Dutch Harbor and smaller garrisons on Adak, Kiska, and Attu. They also believed that there were one or two small air-

[258]

craft carriers as well as cruisers and destroyers operating in Aleutian waters. But they knew nothing of the new airfields east and west of Dutch Harbor then nearing completion.17 The Japanese plan for operations issued on 5 May 1942 reflected this faulty knowledge. Under the plan the Northern Area Force, commanded by Vice Adm. Boshiro Hosogaya, was to contain three separate task forces to carry out the operation. Leading the attack would be the Second Mobile Force, Rear Adm. Kakuji Kakuta commanding, built around the two small carriers Junyo and Ryujo, and including two heavy cruisers and three destroyers, with the mission of bombing shipping, planes, and shore installations at Dutch Harbor and on Adak. It would also provide cover for the landing forces, the Adak-Attu Occupation Force consisting of an Army detachment of approximately 1,200 troops with naval escort, which was first to occupy Adak and destroy United States forces found there, and then to withdraw and assist in the occupation of Kiska and Attu, and a second group, a special naval landing force of 550 combat and 700 labor troops, which was to occupy Kiska. By destroying American bases and occupying islands in the outer Aleutians, the Japanese hoped to prevent the Americans from launching a sea and air offensive by way of the North Pacific and to obstruct military collaboration between the United States and the Soviet Union.18

From the beginning of hostilities the War Department had recognized the vulnerability of the new bases in southern Alaska and particularly of the exposed installations in the Dutch Harbor area. Temporarily, Japan's uninterrupted drive into southwestern Pacific and Indian Ocean areas eased concern over Alaska, but it soon revived. In mid-March G-2 warned that a Japanese attempt to seize the Aleutians or raid the mainland of Alaska in order to prevent the United States from using the northern approach to Japan and to obstruct communication between the United States and the Soviet Union could be expected at any time.19 After the Doolittle raid on Tokyo in April, it was generally expected in Washington that the Japanese would retaliate by raiding the west coast or Alaska.

The first definite indication that Alaska would be among the targets in a new Japanese offensive eastward was obtained from intercepts in late April. These revealed that the Japanese were concentrating striking forces at Truk

[259]

and in home waters, and that the admiral in command at Truk "had just requested information and charts from Tokyo on the close-in waters along the Aleutians and as far eastward as Kodiak Island and to the north a little short of Nome." 20 While Washington interpreted this information as a definite threat to Alaska, it also concluded that at least another month would pass before the Japanese could attack. On 3 May General DeWitt relayed the information to General Buckner and renewed his plea for the assignment of a pursuit squadron to the airfield at Umnak, which was now operational.21 More intercepts in May pinpointed the Japanese objectives as Midway Island and Dutch Harbor, and by 21 May the United States knew fairly accurately what the strength of the Japanese Northern Area Force would be and when it would strike- 1 June, or shortly thereafter.22

The Army and Navy took quick steps to counter the anticipated Japanese blow. As a precaution the War Department directed that the Umnak field and other facilities in danger of capture be prepared for demolition, but in transmitting this order General DeWitt assured General Buckner that additional means for defending Fort Glenn would be provided.23 The Navy prepared to reinforce its existing minuscule "Alaskan Navy" by establishing a new Task Force 8, under the command of Rear Adm. Robert A. Theobald, and assembling its principal components (five cruisers, fourteen destroyers, six submarines, and auxiliaries) off Kodiak as rapidly as possible.24 On 21 May General Marshall and Admiral King declared a state of fleet-opposed invasion prospectively in effect "until and if invasion in force of Kodiak or Continental Alaska become imminent." At the same time they directed that all Army and Navy air units then in Alaska should be put into a task force to be commanded by the Army's General Butler, who in turn would report to the new Task Force 8 commander on his arrival in Alaska. Army ground forces were kept under Army command, and General Buckner was to coordinate their employment with those of naval forces by mutual co-operation.25 When Admiral Theobald reached Kodiak on 27 May, he and General Buckner agreed to maintain these command relationships unless the.

[260]

Japanese captured a base in the Umnak-Dutch Harbor-Cold Bay area, in which event an invasion of the mainland might be deemed imminent and unity of command over land and shore-based defense forces might therefore be vested in the Army.26 These preparations and command arrangements reflected a widespread belief among American planners and commanders that the Japanese were bent on capturing Dutch Harbor.

Before Admiral Theobald reached Kodiak, General Butler had begun to move Army planes forward to the new Cold Bay and Umnak air bases, where adequate supplies of gasoline and bombs had already been stockpiled. By 1 June 1 heavy and 6 medium bombers and 17 pursuits (now called fighters) had reached Fort Glenn on Umnak, and 6 medium bombers and 16 fighters were at Cold Bay-all the planes their unfinished airfields were believed able to accommodate. On the same day the Navy had 8 radar-equipped patrol planes operating from Dutch Harbor. Air reinforcements, including extra pilots, were being rushed from the continental west coast to Alaska, to bring its strength in modern Army combat planes to 10 heavy and 34 medium bombers and 95 fighters. All these planes were for use at Elmendorf Field and beyond, since by this time the Royal Canadian Air Force had two squadrons of fighter planes at the Annette Island base in southeastern Alaska (and near the British Columbia port of Prince Rupert) and the intermediate Yakutat base had no planes assigned. The total Army strength in Alaska by 1 June was about 45,000 officers and enlisted men, of whom about 13,000 were at Fort Randall and the Aleutian bases. 27

On 25 May the enemy carrier force for the Dutch Harbor assault sortied from Ominato in northern Honshu, and thick weather protected its approach to the target. A naval patrol plane spotted the enemy about 400 miles south of Kiska in the early afternoon of 2 June, and unusual radio activity later on the same day also helped to alert the defenders. In the early morning hours of 3 June, Admiral Kakuta's Second Mobile Force was in launching position south of Dutch Harbor, but less than half the planes launched reached their objective. Starting about 0545, seventeen bombers and fighters from Ryujo attacked Fort Mears and naval installations at Dutch Harbor, inflicting some damage on barracks and other facilities and killing about twenty-five soldiers and sailors. The Japanese lost two planes to antiaircraft fire. At 0900 the enemy launched a second strike aimed at a group of five American destroyers

[261]

sighted by one of the planes of the first attack force, but the weather closed in and concealed the American ships and the enemy could not find them. Four Japanese seaplanes that were launched from cruisers flew over Umnak. P-40 fighters from the new Otter Point airfield attacked them and destroyed two. Overcast hid the field, and not until the following day did the Japanese discover the existence of the new American forward air base.28

After recovering its planes, the enemy task force moved off in a southwesterly direction. During the night Admiral Kakuta changed course for Adak, which he had been ordered to soften up. But the weather was so bad that Kakuta decided to cancel the Adak attack and return for a second assault on Dutch Harbor. Late on 4 June Japanese planes struck again and destroyed four oil storage tanks, demolished a wing of the naval hospital, and partially destroyed the beached barracks ship Northwestern. Army and Navy casualties at Dutch Harbor for the two days were forty-three killed (thirty-three of them Army) and about fifty wounded. Both Dutch Harbor attacks were opposed by intense antiaircraft fire from land artillery supported by the naval guns fired from ships in the harbor. And, however startling they were, the attacks had little effect on the use of Dutch Harbor as a forward naval base.

While Army planes based on Umnak and at Cold Bay were not able to prevent the enemy from bombing and strafing Dutch Harbor, planes from Umnak did intercept 8 of the Junyo planes returning from the second day's attack and shot down 4 of them while losing 2 of their own. Army and Navy efforts on 3 June to locate and attack the enemy carrier force were fruitless. The next morning a Navy patrol plane spotted the enemy, and several flights of Army planes attacked during the day. In the early afternoon a medium bomber dropped a torpedo on or beside one of the carriers, but it failed to explode. Six heavy bombers were flown forward from Kodiak on 4 June, and 2 of them succeeded in locating and bombing the enemy force. Before the day was over, other medium bombers from Umnak fired two torpedoes at an enemy cruiser. Contemporary claims by flight crews of explosions and hits were all denied by the Japanese after the war, and apparently the enemy surface ships escaped unscathed. During the whole action the Japanese lost about 10 planes, the Army 5 (and at least fifteen airmen), and 6 Navy patrol planes were put out of action.

[262]

In the much larger action off Midway to the south, the Japanese suffered a severe setback, and momentarily they suspended their plans for landings in the western Aleutians and turned the Northern Area Force task forces homeward. Then, on 5 June, with the Adak landing abandoned for the time being, Admiral Hosogaya ordered the Adak-Attu Occupation Force to proceed to Attu, where its 11,200 troops began to land on 7 June, the day before the special naval force landed on Kiska. At the time of the landings the enemy intention was to stay only temporarily, and to withdraw before winter. Kiska without Midway no longer had any value as a base for patrolling the ocean between the Aleutian and Hawaiian chains; but Kiska and Attu in Japanese hands did block the Americans from using the Aleutians as a route for launching an offensive on Japan, and holding them had at least a distinct nuisance value. Before the end of June, therefore, the Japanese decided to stay and to build airfields on both islands.29

After the Dutch Harbor raid the Navy sent the patrol tender Gillis forward to Atka Island, and a Navy plane operating from Atka discovered the Japanese occupation of Kiska on the afternoon of 10 June. During the next three days Army bombers from Cold Bay and Umnak and Navy planes from Atka bombed the Kiska landing area as best they could through heavy overcast, but without much visible effect. A threatened counterattack by Japanese flying boats against Atka led to the withdrawal of the Gillis, and thereafter the bombing of Kiska was left to Army planes. Only about half the missions flown by them during June and July were able even to locate the target, and those that did inflicted comparatively minor damage. Weather was the great enemy in Aleutian air operations during the summer and fall of 1942; only nine of the seventy-two planes lost by the Eleventh Air Force through 31 October were destroyed in combat. The evident impossibility of bombing the enemy out of Kiska from the air persuaded the Navy to attempt a surface bombardment. After two tries in late July had been frustrated by dense fog, a naval force headed by four cruisers succeeded in bombing Kiska for half an hour on 7 August and inflicting considerable damage, but not enough to budge the Japanese. It became evident that only a joint and fairly large-scale

[263]

operation to recapture the enemy-held islands would get the Japanese out of the Aleutians.30

The Joint Chiefs of Staff had decided as much on 15 June, in their first discussion of the enemy occupation of Attu and Kiska. They also agreed that the sooner a determined effort was made to oust the Japanese from the Aleutians, the lesser the means that would be required to do it. At this time they considered it likely that the Aleutian attack and occupation was part of a holding action designed to screen a northward thrust by Japanese forces into Siberia's maritime provinces and the Kamchatka Peninsula. Following this discussion Admiral King and General Marshall sent warnings to the theater commanders that a Japanese attack on the Soviet Union might also include the occupation of St. Lawrence Island and of Nome and its adjacent airfields on the Seward Peninsula.31

The Chief of Staff took a personal hand in ordering the rush movement of reinforcements to Nome, then guarded by a single infantry company. He directed General Buckner to transfer twenty antiaircraft guns with their crews by air from Anchorage to Nome, where they had arrived by 21 June. During the succeeding two weeks 140 additional planeloads of men and equipment were flown in. Supplementing the air movement, ships from Seward carried troops, guns, ammunition, and vehicles to Nome, and by early July it had a garrison of more than 2,000 men. Far to the south of Nome, the Army on 17 June established a garrison of 1,400 officers and enlisted men at Port Heiden on the north side of the Alaska Peninsula, with the mission of developing and holding an air base intermediate between the Kodiak and Cold Bay fields, this new garrison becoming the Army's Fort Morrow. By mid-July the Army was also maintaining intelligence detachments on St. Lawrence Island and in the Pribilofs to keep track of enemy movements.32

The striking power of the Eleventh Air Force substantially increased following the enemy attack in early June, which occurred as air reinforcements were being rushed to Alaska and its forward bases. On 30 June the War

[264]

Department allotted the Alaskan air forces 2 heavy and 2 medium bombardment squadrons and one fighter group of 4 squadrons, all equipped with modern planes suitable for the Alaskan environment, and with substantial overstrengths in planes and crews to take care of operational losses. During the summer and fall of 1942 this strength was fairly well maintained. The new tactical air units sent to Alaska also had the support of a greatly increased flow of service units and supplies, including much more adequate radar equipment, and they were reinforced by the forward movement in June of 2 squadrons of Royal Canadian Air Force planes to Anchorage and beyond. Thereafter, air operations in the Aleutians became an Allied effort. The ground strength of the Alaska Defense Command was also substantially increased during the summer of 1942, and by the end of August its forces numbered about 71,500 officers and enlisted men.33

Both General DeWitt and General Buckner interpreted the Japanese occupation of Attu and Kiska and especially the enemy build-up on the latter island as preparation for an offensive eastward with the capture of Dutch Harbor as the initial objective. Both wanted to use Army and Marine Corps forces available in Alaska and on the west coast to mount an expedition against Kiska as soon as possible, and they wanted to cover this operation and perhaps draw the enemy into a decisive naval engagement by using American naval power in Hawaiian waters as well as that in Task Force 8. General Buckner's more specific plan called for an initial occupation of Tanaga Island and the quick construction of an airfield there to provide close support by land-based aviation during the Kiska operation.34

As the theater commanders were preparing these recommendations, they were disturbed by a visit from Brig. Gen. Laurence S. Kuter, Deputy Chief of the Air Staff, who rather bluntly informed them that the War Department considered the Aleutian situation of little consequence and Alaska a minor theater of operations that should be kept strictly on the defensive with no further Army air reinforcements. The Chief of Staff promptly disavowed General Kuter as a spokesman for the War Department on such matters as these, but the latter's views did reflect a growing disinclination in Washington to commit large forces in an Aleutian offensive. Instead, the Army and Navy decided, as stated in a joint directive of 2 July, to undertake limited offensive

[265]

operations in the southern Pacific, a decision that virtually ruled out the use of major Pacific Fleet forces, including the Amphibious Force, in North Pacific operations, at least during 1942. Admiral King personally communicated this decision to General DeWitt on 6 July. In effect, it meant that any Aleutian offensive would have to be confined to what could be done with Army and Navy forces already in Alaska, bolstered by such units as General DeWitt could spare from west coast ground forces already under his command.35

Operations in Alaska during and after the Japanese attack and landings revealed a certain amount of interservice discord. The lack of co-ordination between the services can in part be attributed to the physical separation of the Army and Navy headquarters. Navy headquarters were located on Kodiak Island, and Army headquarters were at Fort Richardson near Anchorage, nearly three hundred miles away. The joint operations center previously set up by the Army at Anchorage proved practically worthless and had to be replaced by a similar establishment at Kodiak. Until the new center began functioning in August, the exchange of intelligence information between Navy and Army was slow and faulty.36

The control and conduct of air operations provided another source of friction. General Buckner was highly incensed by a complaint, attributed to a naval officer in Alaska and transmitted to the general by the War Department, that Army air units had been slow in responding to Navy requests for air support during the Dutch Harbor raid because of the Army's lack of understanding of command arrangements. He informed General DeWitt that the delays had been caused by limited communications, lack of sufficient bombardment aviation, and the exhaustion of pilots and crews who had been forced to fly in fog and the almost continuous daylight then prevalent, rather than any misunderstanding about command.37 In fact, the directive to place

[266]

both Army and Navy air units under the command of the senior Army air officer in Alaska, General Butler, was not put into full effect until peremptory orders from Washington required that it be done.38 The situation was aggravated by a lively personality clash among the senior Alaskan commanders, which tended to undermine the formal command arrangements that had been made.39

War Department officials were cognizant of the discord in Alaska and endeavored to rectify the situation without fanfare. In June, when General Kuter visited Alaska, he investigated the controversial air command question and was authorized to take such remedial action on the spot as he could. And when, in August, Col. Carl Russell of the Operations Division set out for Alaska as the military representative on a Senate investigating committee, he was asked "to unofficially familiarize himself with the relations between the Army and Navy in Alaska." 40 Governor Ernest Gruening, the Alaska War Council, and the Senate's Chandler Committee were less patient. They urged the War Department to establish a unified command in Alaska at once in order to meet the potential threat of an enemy invasion. As a result the matter was referred to the joint Chiefs of Staff for consideration. After careful study, they decided against any change in the command arrangements in Alaska. Ultimately, as a result of a discreet transfer of personnel, interservice friction and discord largely disappeared.41

Until these transfers had been effected, command relationships were an important factor in reopening for discussion two proposals argued during 1941. The one was whether the commanding general in Alaska ought to be an air officer. The other was the closely related question of whether the Alaska Defense Command ought to be detached from the Western Defense Command and established as a separate theater of operations.

The Chief of Staff informed General DeWitt in September 1942 that the War Department contemplated replacing General Buckner by a senior air officer and establishing an Alaskan Department in the near future. The

[267]

professed reason for the change was that Army planners had "always had in mind that after the ground forces were well established in the Aleutians the command should pass to an air man as that would be the principal arm of operation." 42 It is far more likely that the real reason General Marshall proposed to make the change in command was to permit a quiet shift in personnel that would eliminate one basic cause of friction between the services. At any rate, after the Alaskan naval commander had been replaced, and after a close and harmonious working relationship developed between his successor and the commanding general of the Alaska Defense Command, the matter was not pressed.

Once again General DeWitt argued vigorously against the proposal to separate Alaska from the Western Defense Command, reviewing in detail the reasons he had given in the spring of 1941. He maintained that the Alaska and Western Defense Commands were strategically interlocked by a single mission. He also argued that supply and administrative matters could be more effectively administered by a single command than otherwise. Washington staff planners, on the contrary, favored an independent Alaskan command. They felt that from the strategic point of view there was no more reason for Alaska to remain under the Western Defense Command than for Hawaii to be in the same subordinate relationship. They argued that because of the improvement in supply procedures and communication facilities a separate Alaskan theater was entirely feasible. They believed that the size of Army forces in Alaska and the possibility of major operations in the area justified the establishment of a separate command.43 For the time being nothing was done to alter the chain of command, although the matter remained a subject of staff study throughout the winter of 1942 and for most of 1943.

As noted above, Japanese action against the Aleutians immediately renewed American anticipation of Soviet involvement in the Pacific war, and as late as 11 July Army intelligence was forecasting a Japanese attack on Siberia in the near future as a virtual certainty.44 During May, Soviet interest in the Alaskan air route to Siberia had also revived, and on 8 June Ambassador Maxim M. Litvinov told Mr. Harry Hopkins that the Soviet Government

[268]

"had agreed to our flying bombers to Russia via Alaska and Siberia." Mr. Hopkins guessed that the real reason behind this Soviet agreement was to prepare the way for the flight of American bombers to the Vladivostok area in the event Japan attacked.45 After the discussion of the North Pacific situation by the joint Chiefs on 15 June, they drafted a message to be sent by President Roosevelt to Marshal Stalin, expressing the President's pleasure with Soviet agreement to use the Alaska-Siberia air route for ferrying lend-lease planes to Europe, and proposing the immediate exchange of detailed military information and staff conversations to prepare the way for collaboration against Japan in the North Pacific. Marshal Stalin's response suggested that American planes being sent to the western front be taken over by Soviet flyers at Nome or elsewhere in Alaska, and, while agreeing to staff conversations in Moscow he was very noncommittal about military collaboration in the Far East.46

Following this exchange the United States sent Maj. Gen. Follett Bradley to Moscow for staff conversations, and the Army Air Forces began to prepare Ladd Field at Fairbanks (rather than Nome) as the delivery point for lend-lease planes destined to the Soviet Union.47 When General Bradley reached Moscow at the end of July, he found Russian officials primarily interested in the ferrying project. They professed no alarm over a Japanese threat to Siberia and were evidently as determined as ever to avoid a two-front war as long as they were hard-pressed by the Germans in Europe.

The planes for the Soviet Union were flown by way of the Northwest Staging Route to Ladd Field at Fairbanks, which was designated an exempt station under Army Air Forces' control, although support of the ferrying operation became one of the principal missions of the Alaska Defense Command. The first planes from the continental United States reached Fairbanks in September 1942 and, after inspection and acceptance by the Russians, were flown off by them before the end of the month. For the first six months many difficulties plagued the operation, but eventually the Alaskan air route became the principal means for delivering aircraft to the Soviet Union. The

[269]

route to Fairbanks also provided a means for delivering planes to the Eleventh Air Force, and transport service along the route gave some essential support to military operations in the Aleutians and beyond. But the air route operated by the Army through northwestern Canada and across Alaska served principally and very largely the purpose of delivering airplanes to the Russians, an activity which continued unabated until the summer of 1945. 48

With the decisions on Pacific strategy that Admiral King had communicated to him in mind, General DeWitt on 16 July submitted a more modest plan for a joint offensive in the Aleutians. Engineer reconnaissance in late June had indicated the feasibility of constructing an airfield quickly on Tanaga Island, located about 400 miles west of Umnak and 200 miles from Kiska, and it was this survey that had prompted General Buckner to recommend the occupation of Tanaga as the first step in a drive on Kiska. General DeWitt now proposed it as "the next best step to the occupation of Kiska to thwart the enemy's eastward movement," and as an essential move toward the capture of Kiska eventually. He planned to send an initial garrison of 3,200 Army troops to Tanaga, including infantry and artillery elements from the west coast, and to do so during August if the Navy's Alaskan forces were prepared to cover the landing.49

In Washington, discussion of this proposal developed a preference of the Navy for a landing on Adak Island, about sixty miles east of Tanaga. Adak, the Navy believed, had a better and less exposed harbor; on the other hand, the information then available to the Army indicated it would take much longer to build an airfield there. A directive of the joint Chiefs, announced on 5 August and confirmed five days later, apparently settled the argument in favor of Tanaga. But, on 15 August, Admiral Theobald reported that his survey board had advised that an occupation of Tanaga would present the Navy with serious navigational hazards, and Admiral King thereupon withdrew his approval of the Tanaga operation. Confronted with the choice of Adak or no forward advance, General DeWitt agreed to go along with the Navy and occupy Adak. The revised joint directive for this operation, dispatched on 22 August, suggested a supporting occupation of Atka Island to the east of Adak to provide an intermediate emergency landing field for

[270]

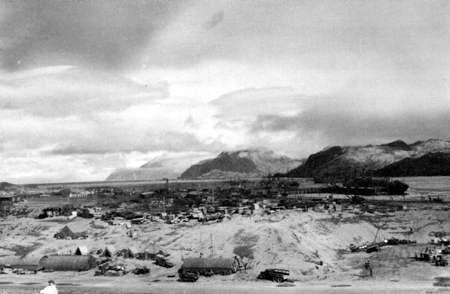

CONSTRUCTION ON ADAK. Airport and harbor (top). Dredging sand from an inlet to fill in the airfield (bottom).

[271]

fighter planes, and a skeleton movement of Army troops to Tanaga at the time of the Adak landing to deceive the enemy. The theater commanders considered the Tanaga suggestion impracticable, but the Atka occupation was carried out by an Army force of 800 men on 16 September.50

In the meantime, preliminary reconnaissance landings on Adak on 26 and 27 August had failed to discover any enemy forces on the island, and three days later an Army force of about 4,500 began to come ashore. The fortuitous discovery that a tidal basin near the landing area could be used as an airfield site solved anticipated construction problems on that score. Army engineers installed an ingenious drainage system which with fills provided a usable airfield in less than two weeks, instead of the two or three months that had been forecast. The Army planned to increase the Adak garrison to more than 10,000 men by mid-October, and thus to make it the strongest as well as the most advanced of the Alaskan bases.51

A few days after the Adak landing General DeWitt ordered the Alaska Defense Command to send an Army detachment to St. Paul and St. George Islands in the Pribilofs, from which the native population had been evacuated in June. A Joint Chiefs directive of 6 September confirmed this move, which in transmission crossed a vigorous message of protest from Admiral Theobald. At his insistence the operation was briefly deferred, an Army force of 800 finally landing on St. Paul on 19 September, where it was housed in the abandoned civilian dwellings and where it built a fighter strip that was ready for use by the end of October.52

The new base at Adak soon proved its worth. On 14 September a force of twelve B-24 heavy bombers accompanied by twenty-eight fighters from Adak delivered a strong attack on Kiska. The planes encountered intense fire from Japanese antiaircraft guns whose numbers had been increased by the withdrawal of antiaircraft forces from Attu only four days before. Nevertheless, the attack was highly successful. While fighters of the 42d and 54th Squadrons strafed installations, shelled three small submarines, and left a large four-motor flying boat burning in the harbor, the B-24's were

[272]

chalking up hits on enemy shipping and on base installations. Two mine sweepers and three cargo vessels were considered sunk or badly damaged, several other seaplanes were destroyed, and fires set on shore. Losses among the attackers were limited to two P-38 fighters that collided in midair while chasing the same enemy fighter. Then a long spell of bad weather intervened. The attack was resumed on 25 September, when a combined United States-Canadian force struck another hard blow against Kiska. Nearly every day for the next three weeks, and sometimes twice a day, American and Canadian planes shot up the Japanese installations or bombed shipping in Kiska Harbor. During September slightly more than 116 tons of bombs were dropped on the enemy, almost twice as much as in the entire period up to 1 September; and in the following month, October, 200 tons of bombs were dropped. On 14 October a particularly strong formation exploded a supply dump on Kiska and started large fires in the Japanese camp area. Two days later a flight of six medium bombers sank one Japanese destroyer and damaged another. Then, beginning in November, bad weather and the withdrawal of heavy bombers from action restricted air operations until February to reconnaissance and occasional bombings.53

The repeated bombings of Kiska during the summer had persuaded the enemy that the Americans aimed to recapture it, and in order to strengthen Kiska the Japanese on 24 August put all of their Aleutian forces under naval command and ordered the Army garrison on Attu to move to Kiska. The movement was completed by 16 September, after destruction of the defense installations so laboriously undertaken on Attu. Following a second reorganization of the enemy's North Pacific forces in late October, the Japanese Army increased its garrison in the Kuril Islands and reoccupied Attu. By early November enemy forces on Kiska numbered about 4,000 and those on Attu about 1,000. The Japanese counted on darkness and the weather to protect them from any serious American attack before the following March, and in the meantime they hoped to complete airfields for land-based planes on Kiska and on Shemya Island near Attu, something they were never able to do. Throughout the Aleutian Campaign the Japanese had to depend either on carriers, which made their last visit in July 1942, or on planes that could be floated; and weak air attacks on Adak during October did little more than illustrate the ineffectiveness of enemy air power. The Japanese also hoped to occupy Amchitka Island, about eighty miles southeast of Kiska, to bar another

[273]

American move westward. While enemy orders referred to Kiska as "the key position on the northern attacking route against the United States in the future," it is fairly evident that the Japanese had no such design and were attempting only to block the American advance.54

United States Army and Navy leaders were in agreement by October that the only satisfactory solution of the Aleutian situation would be to launch an amphibious assault on Kiska. They assumed that the core of the assault force would have to be an infantry division or its equivalent and that this division would need at least three months of special training. The division and its supporting forces could not be made ready for the operation before March 1943 at the earliest, and in any event the Aleutian environment during the intervening months would be at its worst. These considerations, coupled with a crisis in the Guadalcanal operation in the South Pacific, led in November to the stripping of Task Force 8, and it would not be able to command and cover an assault on Kiska until its strength was restored. In the meantime, the most the Army and Navy could do in the Aleutians would be to expand and strengthen their forward bases.55

As soon as the airfield on Adak was in operation, General Buckner and Admiral Theobald began preparations for the occupation of Tanaga, which they planned to do by the end of October.56 As originally conceived, this was to be a defensive measure intended to thwart a Japanese move in the direction of Adak. For the purpose of supporting an assault on Kiska, Tanaga offered no particular advantage over Adak.

In Washington Army and Navy planners since August had been considering an occupation of Amchitka, and at the War Department's suggestion a reconnaissance of Amchitka was carried out at the end of September to determine how long it would take to construct an airfield there. The reconnaissance indicated that the construction would be difficult, and therefore General DeWitt strongly objected when General Marshall asked him whether Amchitka could be substituted for Tanaga, especially since the Chief of Staff in the same message warned that Alaskan naval strength might be drastically reduced in the near future. When General Marshall

[274]

repeated the Amchitka proposal at the end of October, General DeWitt postponed the Tanaga operation, which was to have started on I November, and directed General Buckner to arrange with Admiral Theobald for a new survey of Amchitka. The appointed survey party remained at Fort Glenn for more than a month, with General DeWitt's concurrence, because Admiral Theobald thought its transport by Navy plane to Amchitka too risky in view of the increased enemy strength on Kiska and enemy patrol activity in its vicinity.57

Then, on 13 December, General DeWitt discussed the situation in the Aleutians with Rear Adm. Thomas C. Kinkaid, who was on his way to Alaska to relieve Admiral Theobald as commander of Task Force 8. Admiral Kinkaid, who had recently commanded a carrier group in the Solomons, was fully acquainted with Japanese capabilities as well as the course of the war in the South Pacific. Having been briefed by Admiral Nimitz on the Aleutians, he had reached the conclusion that an airfield had to be built on Amchitka to prevent the Japanese from building one there. In a discussion with Admiral Kinkaid, General DeWitt agreed to call off the occupation of Tanaga and to substitute the Amchitka operation. Admiral King, who was also in San Francisco conferring with Admiral Nimitz, immediately concurred. The reports from San Francisco led to the prompt dispatch of the Amchitka reconnaissance party, which visited the island on 17-19 December.58

On his return to Washington Admiral King submitted the draft of a joint directive to General Marshall, calling not only for the occupation of Amchitka immediately if the new survey proved to be favorable, but also for the selection of Army forces for the Kiska assault and initiation of their training. General Marshall agreed, on condition that the reconnaissance of Amchitka indicated that an airfield could be built there within a reasonable time and provided, further, that no definite target date was set for the invasion of Kiska. These conditions were acceptable to Admiral King, and on 18 December the Joint Chiefs of Staff issued a directive to this effect. Two days later General DeWitt reported that the reconnaissance party had returned with news that a fighter strip could be built on Amchitka in two or three weeks and a main airfield with a 5,000-foot runway in three or four

[275]

months. He assumed, therefore, that, in accordance with the joint directive, the Amchitka landing should be made as soon as possible.59

Bad weather frustrated the first attempt to land troops on Amchitka on 9 January 1943, but during the night of ii January a small security detachment was put ashore from the destroyer Worden. The next morning a combat team of nearly 2,000 men, under the command of Brig. Gen. Lloyd E. Jones, disembarked without opposition. The only enemies were the weather, the unpredictable current, and the rock-studded waters through which the landing was made. The Worden, after landing the security party, ran onto a rock pinnacle and sank with the loss of fourteen men. The first night the main body of troops were on shore a gale blew up that smashed a considerable number of the landing boats and swept the transport Arthur Middleton aground. The second day brought a blizzard. And so it went for almost two weeks. When the weather cleared, the Japanese discovered what was happening on Amchitka. Beginning on 24 January, Japanese planes made a number of light bombing and strafing attacks on the island but failed to halt work on an airfield. By 16 February, the fighter strip was ready for limited operation. On that day eight P-40's arrived on Amchitka, and within a week they were running patrols over Kiska. 60

The stage was now set for the next phase of operations, amphibious attacks to eject the Japanese from their Aleutian footholds.

[276]

page created 30 May 2002