CHAPTER II

The Command of

Continental Defense Forces

As the United States Army began its rapid expansion in the late summer of 1940 for the eventuality of war, it had a command organization far better adapted to the control of peacetime than of wartime operations. For many years the War Department had foreseen that this organization would have to be changed whenever a major war threatened, and it had planned accordingly. The plans for transforming the command system to a wartime basis were in fact partially carried out during the year and a half preceding the formal entry of the United States into World War II and immediately thereafter. They could not be carried out in full because the circumstances of American involvement in the war and the problems of defense during the initial mobilization of forces differed from those that had been assumed. Instead of beginning its mobilization on a relatively fixed M-day to deal with a clearly defined war situation, the Army spread its prewar expansion over many months during which the war outlook underwent continuous change. Even without these factors, the earlier plans for wartime organization would have required some modification because of the changed character and increasing complexities of warfare and therefore of the nature of the dangers that war would bring to the United States.

In planning for the command of active operations, the Army tried to adhere to certain basic strategic and organizational principles. It wanted to avoid dispersing its forces in a weak cordon defense of the frontier, whether of the continental United States or of the Western Hemisphere. Instead, it planned to group the bulk of Army ground and air forces in a mobile reserve within the continental United States. The very large expansion of the Army decided upon in the summer of 1940 required a tremendous training effort, and it was the Army's policy to meet current tactical needs with the least possible interference to the training program. In reorganizing its command structure, the Army tried to conform to the principle that the officers responsible for planning operations should also be responsible for executing them. Finally, the Army theoretically favored the establishment of unity of

[16]

command both over its own ground and air forces and over Army and Navy forces in potential or actual theaters of operations, although in practice not much progress was made in either direction before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Peacetime and Planned Wartime Organization

The National Defense Act of 1920 provided the basis for the establishment of a new command system for the Army after World War I. The War Department on 1 September 1920 established nine corps areas with fixed boundaries and gave their commanders full tactical and administrative control over all Army forces and installations within their areas except for those specifically exempted. The Army forces in the Panama Canal Zone, Hawaii, and the Philippines were organized into departments, identical in character and authority with die corps areas in the continental United States. Until the eve of World War II, the few Army troops in Puerto Rico and Alaska were not separately organized but were attached to the Second and Ninth Corps Areas, respectively. On 1 July 1939 Puerto Rico became a separate department, but Alaska remained under the Ninth Corps Area and successor defense agencies until 2 November 1943. Theoretically, from 1920 until 1932 Army forces at home and overseas were divided among three army areas, but these areas never had more than a nominal existence. Until the fall of 1932, the tactical control of the ground and air combat forces remained with the corps area commanders, who in turn were directly responsible to the Chief of Staff. Under the corps area commanders, the commanders of five coast artillery districts were responsible for planning and executing the Army's seacoast defense mission. Corps area commanders themselves were responsible for defending the Canadian and Mexican land frontiers and for protecting the nation against internal disturbances.1

The system of command began to change in the fall of 1932 when the War Department established four armies without fixed territorial bounds though located within the limits of specified corps areas-the First Army within the First, Second, and Third Corps Areas, for example. The initial "four-army" directives of 1932 seemed to indicate an intention to transfer

[17]

all tactical responsibility except for internal security measures from the corps area to the army commanders, but modifications of the four-army plan in 1933 and 1934 restricted the army commanders to war planning and the direction of field maneuvers within their areas. Furthermore, until the autumn of 1940 the armies were not given separate commanders and staffs to perform these functions; the senior corps area commander within an army area served as the army commander, and used his corps area staff to conduct the army's business.2 Since three of the four army headquarters changed location between 1932 and 1940, this last provision meant in practice that much army staff work had no continuity. Under these circumstances, although General Staff war plans after 1932 regularly specified that the armies should work out detailed area defense plans, the armies could do little effective planning of this sort before the fall of 1939.3

The War Plans Division of the General Staff defined the peacetime defense responsibilities of the corps area and army commanders in February 1940 in the following terms:

a. The missions of the several corps areas comprise: Defend as may be necessary important coastal areas in their respective corps areas; arrange with appropriate naval district commanders for cooperation of local naval defense forces in execution of assigned missions; provide anti-sabotage protection for such installations and establishments vital to national defense as cannot be adequately protected by local civil authorities; take necessary action under the Emergency Plan-WHITE ; 4 and, in certain cases, receive at detraining points, move to concentration areas, care for, supply, and move to ports of embarkation units designated for [overseas] movement.

b. The armies are responsible for coordinating the defense of the coastal frontiers of the corps areas included in their respective army area; for exercising general supervision of the arrangements made by those corps areas with the naval districts concerned for the cooperation of their local defense forces; and for effecting any necessary coordination of anti-sabotage measures along corps area boundaries.5

Irrespective of this definition, or of the wording of current regulations and directives, the army commanders during late 1939 and 1940 began to play a more active role in war planning and in the tactical direction of the military forces within their areas. Their authority was potentially enhanced by an act of 5 August 1939 giving them the rank of lieutenant-general and thus

[18]

GENERAL DRUM

making them superior in rank to the corps area commanders. A month later, after the outbreak of war in Europe, the War Department launched a series of immediate action measures to improve the Army's state of readiness. Thereafter, Lt. Gen. Hugh A. Drum, commanding the First Army (and Second Corps Area) on the east coast, and (from December 1939) Lt. Gen. John L. DeWitt, commanding the Fourth Army (and Ninth Corps Area) on the west coast, assumed the increasingly broad responsibility that circumstances required. Without any immediate change in existing regulations and directives, the army commanders began to exercise the superior tactical authority within their areas that had originally been proposed for them.

A second major change in the command structure occurred in 1935 with the creation of the General Headquarters (GHQ Air Force. This organization centralized control over all tactical air units in the continental United States under one commander. Until the fall of 1940 air units under the GHQ Air Force were divided among three wings located adjacent to the Atlantic, Gulf, and Pacific coasts. The GHQ Air Force commander was directly responsible to the Chief of Staff until 2 March 1939, when he was placed under the intermediate command of the Chief of the Air Corps. The removal of air units from the control of armies and corps areas did not change the responsibility of their commanders for planning the co-ordinated ground and air defense of their areas, but increasingly the air organization began to engage in defense planning on its own behalf.6

The proper development and co-ordination of the means for air defense presented the Army with a new organizational problem late in 1939. Suc-

[19]

cessful air defense depended upon the integrated action of interceptor planes, antiaircraft guns, and aircraft warning devices for detecting the approach of hostile aircraft. Interceptor aircraft were then under GHQ Air Force command, and most antiaircraft units were controlled by the coast artillery district commanders. The armies had been specifically charged in 1935 with planning for the employment of antiaircraft artillery and aircraft warning devices in air defense. The War Plans Division officer most concerned with the development of long-range radar equipment urged in November 1939 that corps area commanders be made responsible for planning its employment. Noting that the Fourth Army had previously turned over this task to coast defense commanders, he observed that an air attack on the United States was as likely to strike deep in the interior as against the coast. Therefore, he contended, only the corps areas provided a framework that could plan the nationwide employment of aircraft warning devices. A War Plans Division colleague expressed opposing views and urged that aircraft warning plans be a responsibility of the army commanders because they would presumably be called upon to execute these plans in the event of a real emergency. His views prevailed, and the War Department on 23 May 1940 directed the army commanders to develop plans for the effective use of aircraft warning devices and to select the sites for the location of detector stations.7

The graver problem of organizing a co-ordinated and effective air defense system under a united command occupied the attention of an Army Air Defense Board during the winter of 1939-40 There was general agreement that the War Department ought to create a new type of command that could exercise control over the various air defense elements in an emergency. The Air Corps wanted this new organization to be under the GHQ Air Force. After much discussion General Marshall decided to create an experimental Air Defense Command in the northeastern United States and to place it under the First Army. The War Department specified that its commander, although put under First Army Command, should be free to co-ordinate details of his work with the GHQ Air Force and corps area commanders.8

The division of responsibility for war planning and immediate defense action among corps area, army, Air Defense Command, and GHQ Air Force commanders did not matter too much so long as the likelihood of an attack on the continental United States appeared remote and the size of the Army

[20]

GENERAL DEWITT

was still too small to justify the establishment of the more elaborate organization planned for wartime. A transition toward reorganization became mandatory as the actual threat of war loomed in May and June 1940, and as the Army thereafter began its rapid expansion and the tremendous task of training the new Army for war employment if that should become necessary.

In the wartime organization planned under the Defense Act of 1920 the capstone was to be a General Headquarters (GHQ). Until otherwise directed by the President; the Chief of Staff in wartime was also to serve as Commanding General of the Field Forces and to direct both ground and air operations through GHQ. Under GHQ, there might be one or more active theaters of operations, with commanders who would exercise full authority over all Army activities within theater boundaries. Theaters of operations might be established either overseas or in the continental United States; the remainder of the continental United States not included in theaters of operations would constitute the zone of the interior.9 The four armies in the continental United States on M-day (or before, if so directed by the War Department) would assume full responsibility for the defense of their areas against external attack; at the same time, they were to be prepared to move to a theater of operations if so directed. The corps area commanders on M-day would retain tactical responsibility for internal security only within the zone of the interior; theater commanders in the continental United States would assume this as well as all other tactical responsibilities.

The armed services had agreed to coordinate their frontier defense activities in peace and war in accordance with the provisions of Joint Action of the Army and the Navy, as revised by the joint Board in 1935 and subsequently amended. During peace, Joint Action provided for the co-ordination of local seacoast defense preparations between the Army's corps area com-

[21]

manders (or alternately, through the tatter's subsidiary coast artillery district and harbor defense commanders) and the corresponding naval district commanders. Army commanders were responsible in peacetime for planning wartime coastal defense measures, and on M-day they were to assume responsibility for their execution. Joint Action provided for the establishment of four coastal frontiers (North Atlantic, Southern, Pacific, and Great Lakes and for their subdivision in war into sectors and subsectors. These coastal frontiers were to become active commands in wartime, at which time the Army's coast artillery districts were to cease to exist as such and their commanders and staffs were to man the Army's portion of the wartime coast defense organization and be responsible in turn to the army commanders.10 The coastal command system prescribed in Joint Action had two outstanding deficiencies. First, it did not provide an effective means for establishing unity of command where it was really required. Unity of command was not established anywhere until the attack on Pearl Harbor illustrated the disastrous consequences of not doing so. Second, there was no clear delineation of Army and Navy responsibility for coastal air defense, and thus there was no agreement as to how an effective air defense of coastal regions should be organized and controlled.

Reorganization, July 1940-December 1941

The critical situation facing the United States in June 1940 furnished the immediate impetus for the first steps toward the establishment of a wartime command organization. With Britain's early downfall still considered probable, and therefore the chance of early American involvement in the war believed likely, the War Department in July moved to activate GHQ. The order establishing a nucleus of GHQ specified that GHQ's purpose was to assist the Commanding General of the Field Forces in the exercise of "jurisdiction similar to that of Army Commanders" over all mobile ground and air and fixed harbor defense forces in the continental United States. Army commanders at this time had jurisdiction over war planning and field maneuvers within their areas, but GHQ's activities for the time being were expressly confined to the over-all direction and supervision of combat training.11

The War Department also turned its attention, coincidentally with the establishment of GHQ, to a reorganization of the field forces in the con-

[22]

tinental United States in order to give better direction to their training and to improve their readiness for action should the nation become involved in the war. This reorganization had to be adjusted to the rapid increase in the Army's strength that followed the induction of the National Guard, approved by Congress in August 1940, and the passage of selective service legislation in September. These measures together with an increase in Regular Army strength were to multiply the Army's numbers more than fivefold by the summer of 1941, and most of the men and units that were brought into federal service required intensive training. What the Army needed in 1940 and 1941 was a command system that would improve the normal peacetime machinery for the planning and direction of operations without unduly disrupting training.

The problem of fitting the Army's air arm into an effective reorganization of command was complicated by additional factors. Air Corps officers wanted a greater degree of autonomy in planning and directing the employment of air power, and they tended to resist the adoption of any organizational scheme that would place air planning and operations under ground commanders. The airmen had good reason for maintaining their position, since the problem of continental and hemisphere defense seemed increasingly to be primarily one of air defense. The technological improvement of aircraft also tended to render obsolete the older plans for coastal defense organization. The greater range and mobility of the new combat planes made it undesirable to set up any organization that would require the attachment of air units to relatively small territorial commands and restrict their employment to the confines of these commands. The scarcity of combat aircraft added emphasis to the other arguments against territorial attachment. In June 1940 the Army had adopted an ambitious program for organizing and equipping fifty-four air combat groups, but national policy after September dictated the diversion of an increasingly large proportion of American combat aircraft production to Great Britain and the other nations fighting the Axis Powers. During late 1940 and most of 1941, therefore, almost all of the combat airplanes available to the Army within the continental United States had to be used in training. There was virtually no "GHQ Reserve" of combat planes and units, and units in training had to be designated for current defense employment if that became necessary. The effective training of the rapidly expanding air forces required that in the meantime these units remain under air command.

With the easing of the critical Atlantic situation from September 1940 onward, the Army was able to concentrate more attention on training its

[23]

rapidly growing forces for future operations. Accordingly, the next moves toward a tactical reorganization were associated more with training than with the planning and direction of operations. A proposal of the G-3 Division of the General Staff in July 1940 that the corps areas be provided with additional tactical headquarters to facilitate training grew into a War Department directive of 3 October 1940 ordering the separation of the field armies and the corps areas. This directive and supplementary War Department orders provided the armies with separate commanders and staffs, and contemplated also a complete segregation of army and corps area headquarters and functions. The armies were given command of the ground combat forces, which had hitherto been under corps area control except during maneuvers, and the armies now assumed full responsibility for planning and directing the employment of these troops in the defense of the continental United States against external attack. Though the corps area commanders retained their responsibility for internal security measures, the corps areas thereafter became essentially supply and administrative agencies.12

The War Department similarly initiated a reorganization of the combat air forces in the summer of 1940, after the adoption of the fifty-four group program. In August the Chief of Staff, General George C. Marshall, directed the establishment of four air districts to replace the existing three-wing subordinate organization of the GHQ Air Force. These air districts were intended primarily to facilitate the supervision of training. Under the four air districts, GHQ Air Force units were to be organized initially into seventeen wings and forty groups. The existing Air Defense Command, operating in the northeast United States under the direction of the First Army commander, was to serve as a model for a nationwide air defense command system. This air reorganization was only partially carried through in 1940; the air districts were not activated until 15 January 1941, and the expansion of the air defense command system was not approved until March 1941. In the meantime, the War Department on 19 November 1940 removed the GHQ Air Force from the control of the Chief of the Air Corps and placed it under GHQ. The appointment, shortly before this change, of Maj. Gen. Henry H. Arnold, the Chief of the Air Corps, to the additional post of Deputy Chief of Staff made it possible for him to continue to exert a measure of control over the operations of the GHQ Air Force.13

[24]

The organizational changes of late 1940 left a confused and unsatisfactory definition of responsibility for the planning and direction of current and future defense tasks in the continental United States. The confusion was such that subordinate ground and air commanders had to be reminded in December that GHQ still had no functions except those associated with training.14 The four armies had acquired responsibility for planning and controlling operations, but the armies were not territorial organizations and in theory were subject to transfer from their areas to overseas theaters of operations. The situation seemed to call for a new type of fixed territorial defense organization. In October 1940 the GHQ staff, noting that neither the armies nor the planned coastal frontier organization met existing requirements, proposed that four territorial defense commands be organized, with bounds approximating those of the armies. Maj. Gen. Lesley J. McNair, the GHQ Chief of Staff, personally objected to the term "defense commands" and wanted the new organizations called "theaters." Whatever they were called, these defense areas in peacetime were to engage only in planning and were to be commanded by army commanders assisted by a small separate staff, but they were to be so organized that in time of war they could be transformed into a theater of operations type of organization which would operate under GHQ and command the ground and air forces assigned for the execution of continental defense missions.15

The War Plans Division incorporated the GHQ proposal for the creation of defense commands into a study on continental defense organization prepared by Col. Jonathan W. Anderson in late 1940 and presented to the Chief of Staff in mid-January 1941. It appeared to Colonel Anderson that the wartime defense organization prescribed by Joint Action of the Army and the Navy was archaic, since Joint Action provided for a narrow coastal frontier defense only, whereas the possibilities of air attack now required a defense in depth well into the interior of the country. Furthermore, political considerations demanded at least an outline defense organization for the

[25]

whole continental area. General McNair, in discussing these matters with Colonel Anderson, emphasized the desirability of holding to a minimum the forces tactically assigned to the First, Third, and Fourth Armies guarding the seacoast frontiers, and of keeping as many combat units as possible with the Second Army in the interior. General McNair's thought was: "If we give to the First Army three corps, regardless of their needs .... they will plan the employment and distribution of three corps, and . . . it may be difficult at a critical time to pry these troops loose." The First Army, on the other hand, naturally and strongly advocated a defense organization that would give it wartime control over all ground and air forces within its area, peacetime control of a nucleus of bombardment as well as pursuit aviation, and full air defense responsibility. It also wanted to extend the boundaries of the North Atlantic Coastal Frontier to include all United States garrisons established in the North Atlantic area. In principle, War Plans and GHQ agreed on the necessity of holding the ground and air forces assigned to defense missions to a minimum, and of retaining all possible forces in GHQ ground and air reserves from which they could be allocated to active theaters as necessary. General McNair wanted to place the air defense commands in peacetime under GHQ Air Force control in order to facilitate their training; War Plans wanted them under the defense commands in order to establish unity of command in peacetime over all Army defense elements that would be under the defense (or theater) commander in time of war.16

The issue of where to put the air defense commands in the new continental defense organization had deeper implications. Giving the GHQ Air Force control over all air defense means would be another big step toward air autonomy. In November 1940, before War Plans circulated its continental defense proposal for comment, G-3 had taken the initiative in suggesting that the existing Air Defense Command and new commands modeled after it be put under the air districts, and that the air districts, under the GHQ Air Force, be given a very different function from that approved for them by General Marshall the preceding August. They would become tactical as well as training and administrative organizations. Each air district would have a bombardment-fighter force for offensive air operations and an air defense command for defensive purposes. This scheme would centralize air defense control for the whole United States in one

[26]

headquarters, to be located in Washington. Subject to the over-all control of GHQ, the GHQ Air Force would collaborate directly with the Navy in fending off sea and air invaders until an actual land invasion of the continental United States occurred; only then would unity of command over all ground and air forces be established. Adhering to these views, G-3 refused to concur in the War Plans study. In the meantime, and after he had heard "disturbing rumors," the commanding general of the GHQ Air Force urged General Marshall to put all air defense elements under the air districts and thus under his force. When General Marshall found time in mid-January to study and discuss the War Plans, G-3, and GHQ Air Force proposals, he noted that he was "considerably impressed" with the G3 argument. This argument was further fortified shortly thereafter by Lt. Col. William K. Harrison, Jr., of the War Plans Division who, after observing the Air Defense Command's exercises at Mitchel Field, likewise recommended that the air defense commands be put under the air districts.17

An intensive and month-long round of discussions with respect to the peacetime continental defense system followed. Those who favored placing the air defense commands under the four territorial commands argued that there must be unity and continuity of command in peace and war over all defense elements. This argument undoubtedly would have carried more weight if the United States had been closer to war and its continental area more imminently threatened. Everyone agreed that in time of war each theater commander should have control over all air and ground forces within his area. But, as General Arnold pointed out, under existing circumstances it was impossible to foresee where real theaters of operations might be required, and thus it was impossible to delimit them in peacetime. General Arnold believed that the greatest immediate need was for air defense commands overseas in Hawaii and Panama, and that the GHQ Air Force was the proper agency for training mobile air defense commands within the United States that could be sent overseas where needed. He argued therefore that "the United States should be considered basically as a Zone of the Interior," in which "all elements of the Field Forces must be prepared for overseas operations primarily, and the defense of the United States secondarily."18

[27]

Maj. Gen. James E. Chaney, commanding the existing Air Defense Command, joined in urging the Chief of Staff to put air defense under the GHQ Air Force.19 Finally, after extended discussion, General Marshall decided to put the air defense system under the direction of the GHQ Air Force in time of peace and then directed the War Plans Division to work out a continental defense organization on this basis.20

Accordingly the War Department on 17 March 1941 directed that the continental United States be divided into four strategic areas (Northeast, Central, Southern, and Western) to be known as defense commands. It defined a defense command as "a territorial agency with appropriate staff designed to coordinate or prepare to initiate the execution of all plans for the employment of Army Forces and installations against enemy action in that portion of the United States lying within the command boundaries." 21 The new commands were to operate under the direction of GHQ, but not until the War Department enlarged the GHQ staff so that it could undertake this additional responsibility.22

The defense commands were made responsible during peacetime for planning the defense of their areas against ground and air attack, the corps area commanders retaining their responsibility for internal security plans and measures. Other features of the new command system were described in some remarks of Colonel Anderson:

The four Army Commanders, in addition to their responsibilities as Army Commanders, are designated as Commanding Generals, Defense Commands. The responsibility of the Commanding General, Defense Command, includes all planning for the defense of the area, the coordination of these plans with the Navy, and the execution of them in war until such time as the War Department directs to the contrary. The Commanding General, GHQ Air Force, is given the responsibility for the peacetime organization and training for air operations and air defense throughout the entire continental United States. He exercises this responsibility through four Air Forces, each of these Air Forces replacing one of the existing Air Districts. In addition, he is responsible for the aviation and air defense portions of the defense plans for Defense

[28]

Commands. Each Air Force is organized as a bomber command and an interceptor command, the latter replacing the currently named Air Defense Command. The above organization centralizes under the Commanding General, GHQ Air Force, full control and responsibility for the peacetime development and training of aviation and means and methods of air defense. It decentralizes to the Commanding Generals, Defense Commands, responsibility for peacetime planning for coordination with the Navy and for execution of defense in war. It provides for unity of command in all elements employed in each Defense Command.23

The new organization in effect was designed to free the armies from defense responsibilities and thereby permit them to give their full attention to training ground combat units. Though the new defense commands, when activated in June and July, actually consisted of only a few headquarters staff officers engaged in regional planning, the defense command promised to provide a suitable means of transition toward a wartime theater organization, should that become necessary.

The March 1941 reorganization marked a further step toward air autonomy, but the Air Corps had plans for a new and more sweeping air reorganization. Nor was the Air Corps alone in questioning the adequacy of the March reorganization. Before the month was over General Marshall had given his approval to a virtually independent handling of air matters within the War Department.24 In April Secretary of War Stimson noted that the defense system established in March struck him as a "dangerous arrangement" pregnant with "possibilities for misunderstanding and trouble." 25 Mr. Stimson had previously indicated his approval of a unified command system for the Army's air forces, and in his own office he had elevated Robert A. Lovett to the long-vacant post of Assistant Secretary of War for Air. With encouragement such as this, the Air Corps continued between April and June to work out the details of its planned reorganization.

In the air reorganization approved and instituted in June the GHQ Air Force disappeared. The new air establishment was an integral part of the War Department placed directly under the Chief of Staff. Its Chief, General Arnold, continued to occupy the position of Deputy Chief of Staff for Air as well. The Army Air Forces had two components, the Air Corps to handle service functions, and the Air Force Combat Command to control combat training, planning, and operations. The charter of the Army Air Forces -Army Regulations 95-5 issued on 20 June 1941- in effect gave it complete

[29]

authority over air defense planning and operations within the continental United States, at least until theaters of operations were established there. The Chief of the Army Air Forces delegated his specific responsibility for air defense planning to the Air Force Combat Command, which in turn called upon the commanders of the four regional air forces for local defense plans.

The War Department gave the Army Air Forces authority over air defense planning and operations within the United States without revoking any of the responsibility allocated in March to the defense commanders for all defense planning-air as well as ground-within their areas. To add to the confusion, their area defense plans were to be subject to the review and approval not of the Army Air Forces but of GHQ as soon as it was activated as an operational headquarters, as it was about to be.26 The following statement, agreed on by the Army Air Forces and the War Plans Division, represented an early effort to clarify the situation:

The Chief of the Army Air Forces, pursuant to policies, directions and instructions from the Secretary of War, has been made responsible for the organization, planning, training, and execution of active air defense measures, for continental United States. Active operations will be controlled by G.H.Q. These operations will be directed by appropriate commanders, either ground or air, as may be dictated by the situation.27

Subsequently, General Arnold agreed that neither the Army Air Forces nor its component Air Force Combat Command had any official authority to conduct or control air combat operations within a theater of operations established either overseas or within the continental United States.28

These interpretations failed to meet the basic objections leveled by the War Plans Division against the new air organization on the eve of its establishment. The War Plans staff then noted that "the essentials of proper organization require that responsibility and authority be centered in a single agency, and that where this authority and responsibility lie be clearly and definitely stated," and also that "no organization should be set up which requires material change to pass from a peace to a war basis." According to the War Plans Division, the new air organization failed in two vital points when tested by these principles. Noting that Assistant Secretary Lovett in

[30]

presenting the air organization for approval had agreed that GHQ should be ultimately responsible for the planning and conduct of operations, War Plans nevertheless held that the air organization as proposed failed "to grant the Commanding General of the Field Forces at GHQ command authority over all the means." The proposed organization also failed "to prescribe a rapid and certain means of coordinated employment of ground and air forces." 29 All of which meant that while the air reorganization of June 1941 brought order within the Army's air arm, it had not eliminated the "possibilities for misunderstandings and trouble" that Secretary Stimson had foreseen after the March 1941 reorganization.

In the meantime the passage of the Lend-Lease Act in March 1941 followed by President Roosevelt's decision to extend the scope of American naval operations in the North Atlantic had again presented the prospect of active if limited American involvement in the war. It appeared by May that the Army might be ordered on short notice to arrange the dispatch of expeditionary forces from the United States to sundry strategic points along the Atlantic front. Such an order was actually issued on 22 May when the President directed that the Army and Navy prepare an expeditionary force ready to sail to the Azores within one month's time. The preparation and dispatch of a force of this sort required a type of detailed theater planning and executive supervision that no War Department agency was then prepared to perform.

General Marshall met this need by establishing an operations section in GHQ. The directive for this new agency, which he approved on 24 June, stated that GHQ should also prepare to divest itself of its training functions, thus indicating the intention of translating GHQ into the type of operational headquarters contemplated in prewar planning. GHQ was granted broad powers to plan and to control military operations, but only when it was authorized by the War Department to do so for specified commands and areas. When GHQ assumed its new operational functions on 3 July 1941, it also had instructions to take over the responsibility for defense planning in the continental United States as soon as its operational staff was ready to handle the work.30

As things worked out, before Pearl Harbor GHQ was not given the authority to command the new continental defense organization established in March and June 1941, and it had only limited authority over continental

[31]

defense planning. The terms of the new GHQ directive and a statement in the War Department RAINBOW 5 plan distributed in July together were interpreted by the War Plans Division and GHQ as giving the latter the responsibility for supervising the preparation of plans by the defense commands in the continental United States. Subsequently the War Department specifically authorized GHQ to supervise the preparation of continental as well as overseas regional defense plans and to consult with appropriate representatives of the Army Air Forces, the defense commands, and overseas organizations in the execution of this responsibility.31 Neither GHQ nor the defense commands were given the authority to approve or disapprove continental air defense plans; they could only coordinate the air defense portion of over-all plans with the plans of the Army Air Forces.

The operational mission of GHQ was further complicated by a fundamental difference of opinion as to how best to organize for continental and overseas defense. The method prescribed in March 1941 contemplated the segregation of continental defense forces from those of overseas areas and bases. Generals Drum and DeWitt, commanding the armies and defense commands on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts, favored the linking of continental and overseas forces as the best way of permitting the projection of Army power in the direction of a hostile threat. General DeWitt wanted to keep Alaska under his command, and General Drum's Northeast Defense Command headquarters in August 1941 assumed that even Army bases established in Great Britain would come under its authority.32 The Army Air Forces wanted to establish northeastern and northwestern air theaters that would tie in overseas areas and bases with the air forces stationed along the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of the United States.33 Under this plan the air strength of outlying bases could be kept at a bare minimum, since reinforcements could be readily shuttled from the continental United States without violating command boundaries.

But a system under which the continental air forces would provide overseas reinforcements on call was incompatible with a defense organization segregating continental and overseas Army forces. With the armies in theory also movable organizations, a similar incompatibility existed in the Army-continental defense command relationship at the time of Pearl Harbor.

[32]

When the United States went to war on 7 December 1941, the Army's responsibility for defending the nation's continental area rested with the four armies and four air forces rather than with the defense commands that had been activated earlier in the year. The first step toward translating these continental defense commands into something more than planning agencies was taken the day before the Japanese struck in the Pacific. As a result of a suggestion first put forward by the War Plans Division in August 1941, the War Department on 6 December directed that the command of harbor and coast defense units should pass from army to defense commanders not later than 1 January 1942.34 The outbreak of war precipitated more far-reaching changes. After conferring with his principal subordinates on 11 December, General Marshall decided to designate the Western Defense Command (including Alaska as a theater of operations. Instructions to this effect were immediately dispatched to General DeWitt, who took command of the new theater before midnight the same day.35 Also on the 11th, General Drum, the commander of the First Army, arranged an informal system for coordinating Army and Navy defense forces in the northeastern United States that lasted until the establishment of the Eastern Theater of Operations a fortnight later.36 On both coasts the commanders proceeded to organize the defense system long contemplated in Army and Navy planning, coastal frontier sectors and subsectors replacing the peacetime coast artillery district and local harbor defense organizations.

The Western Defense Command as a theater commanded the Fourth Army, the Second and Fourth Air Forces, and the Ninth Corps Area. General DeWitt retained personal command of the now subordinate Fourth Army and exercised control through a combined theater and army headquarters. As a theater commander, General DeWitt controlled all Army troops and installations within the bounds of the Western Defense Command (which comprised California, Oregon, Washington, Nevada, Idaho, Arizona, Utah, Montana, and Alaska), except those specifically exempted by War Department instructions. These instructions imposed three important categories of limitations on his authority: those associated with the organization and movement of air units within his theater; those connected with the move-

[33]

ment of ground and air units and supplies through his theater to overseas destinations; and those pertaining to nontactical functions and installations that were kept under direct War Department control. The first group of limitations was designed to prevent any undue infringement of the autonomy of the air organization, its training of air units, and their availability for quick transfer to other theaters. The second and third groups were essential to the establishment of any theater of operations within the continental United States. These limitations did not seriously restrict General DeWitt's freedom to use the means available within his theater for defending it against both external and internal attacks.37

On the east coast General Drum by conference had arranged an interim working organization for the Northeast Defense Command and a method of coastal defense collaboration between Army and Navy commanders. The First Army established a central headquarters to control all antiaircraft artillery units in the Northeast Defense Command. The Army and Navy commands set up a Joint Operations Office in New York that served as a model for joint operations centers which the Chief of Staff and Chief of Naval Operations asked other commands to establish. General Drum nevertheless believed that the informal arrangements made were inadequate, and he recommended the activation of the Northeast Defense Command as the supreme Army authority in the northeastern United States.38

The War Department appreciated the desirability of centralizing the Army's command authority on the east coast, but it also recognized that the situation there differed fundamentally from that on the Pacific coast since there was no likelihood of any sizable land or air attack along the Atlantic front. Furthermore, the existing defense organization could not be readily translated into a theater of operations; the east coast was divided between two defense commands, the Northeast and the Southern, and each extended far into the interior of the continent. Air defense forces had to be organized so that they could be concentrated anywhere along the Atlantic coast, both in the continental United States and seaward to Newfoundland in the north and to the Caribbean in the south.39 With nothing more than minor air or naval attacks foreseeable, there seemed to be no justification for a theater

[34]

organization of forces extending any great distance into the interior. Therefore, instead of activating the Northeast Defense Command, the Army established a new Eastern Theater of Operations under General Drum's command. The Eastern theater included Newfoundland and the continental coast from Maine to the Gulf of Mexico at the Florida-Alabama line, and extended inland to a line drawn about four hundred miles from the Atlantic coast. The theater forces consisted initially of the First Army, the First and Third Air Forces, units assigned or attached to the First, Second, and Third Corps Areas, the forces of the Newfoundland Base Command, and "all other units now stationed in the Eastern Theater of Operations." Units of these forces currently located outside the theater's boundaries were also put at the disposal of its commanding general. The limitations imposed on the theater commander's authority were virtually the same as those prescribed for the Western Defense Command. The new theater became active at noon on 24 December 1941.40

The War Department placed GHQ in command of the continental theaters established in December 1941, but did not extend its authority to include the Central and Southern Defense Commands.41 These commands, occupying about 55 percent of the continental United States, changed in area, but their authority and means for carrying out defense measures remained poorly defined until March 1942. As long as the Eastern and Western theaters lasted as such, the zone of the interior was restricted, in theory, to the areas of the Central and Southern Defense Commands. In accordance with prewar plans the corps areas' responsibility for internal security measures had passed to the theater commanders, but it remained with the corps areas in the zone of the interior. In both theaters the commanders began to organize a theater-type supply system and in doing so made further inroads on the functions of the corps areas.

The greatest anomaly in the December reorganization, and the one that called for immediate remedy, was the air defense situation. The War Department's theater directives placed the four existing continental air forces under

[35]

theater command, over the strong protest of the Army Air Forces, but left the Air Force Combat Command responsible for air defense measures in the Central and Southern Defense Commands. Early in January the Second and Third Air Forces were moved inland from the theaters and again came under Air Force Combat Command control, a move that did not satisfy the Army Air Forces, which wanted either to regain responsibility for all air defense means and measures in the continental United States or to be excused from any such responsibility altogether. General Arnold, as Chief of the Army Air Forces, protested to the War Department in late January that he was unable to discharge his assigned responsibilities for continental air defense; but as Deputy Chief of Staff for Air, General Arnold directed that no action be taken on this protest, except to use it as an additional argument for War Department reorganization.42

The garrisons of the two continental theaters at the beginning of 1942 contained the bulk of the trained or partly trained combat ground and air units of the Army in the continental United States. Their forces included nineteen of the thirty-four divisions, most of the antiaircraft regiments, and more than two-thirds of the available combat air units. A good many of the ground combat troops were being used to guard vital installations-a task for which Army field force units were neither designed nor trained. Despite instructions directing the theater commanders to continue the maximum degree of training compatible with tactical assignments, the existing deployment of ground and air forces was bound to interfere seriously with training, and furthermore it was threatening to freeze the bulk of the Army's forces in a perimeter defense of the continental United States. Only the imminent threat of large-scale invasion could have justified a continued deployment of this sort. Since it was soon evident that no such threat was in the offing on either coast, GHQ had begun to study ways and means of reducing the theater areas and garrisons even before the activation of the Eastern theater on 24 December.43

To correct the situation, GHQ proposed that the Eastern and Western theaters be reduced to coastal frontier areas approximately one hundred miles wide, with Newfoundland separated from the Eastern theater. Instead of com-

[36]

manding the bulk of the field forces, the theaters were to be considered as task forces and would contain the air, antiaircraft, harbor defense, and troop guard units actually needed for defending the coasts against minor attacks. The First and Fourth Armies were to be separated from the theaters, or at least partially segregated from them, so that all of the armies could concentrate on training larger field units. The corps areas would also be removed from theater control and would assume all supply functions. The basic idea of the GHQ plan was to "reduce theater forces to the minimum required fox defense of the coastal frontier, based on the present situation, and to return the maximum number of field forces to a training status." 44 The War Plans Division agreed with the premises underlying GHQ's proposals but disagreed with the remedies suggested. War Plans wanted to maintain the existing theater boundaries but to restrict interference with training by large-scale exemption of units and installations from theater control. It wanted to keep Newfoundland in the Eastern theater in order to permit its ready air reinforcement. Pending the training of military police battalions that could replace the field units currently on internal guard duty, War Plans wanted to keep internal security responsibility under the theaters in order to avoid confusion and duplication in the assignment of troops to guard duty.45

To resolve the conflicting recommendations of GHQ and the War Plans Division on continental organization, General Marshall decided to send Brig. Gen. Mark W. Clark, Deputy Chief of Staff of GHQ, to make a survey of conditions on the west coast. Before General Clark's departure, the Chief of Staff apparently also decided that Generals Drum and DeWitt must be retained as commanders of the First and Fourth Armies, thus disposing of GHQ's recommendation that the armies and theaters be separated. After conferences with General DeWitt and other Army officials, General Clark recommended to General Marshall the abolition of theater status but the retention of the existing bounds of the Western and Eastern commands-the latter to be designated the Eastern Defense Command. The principal mobile ground force units to be assigned to the Eastern and Western commands would be approximately five and six regimental combat teams, respectively. He also proposed to divorce the corps areas and their functions from the defense commands, and to allot all internal security responsibility to the corps area commanders as soon as military police or other special types of guard units became available to replace field force units in guarding installations. The

[37]

only exception would be the retention by the Western Defense Command of responsibility for guarding certain vital aircraft factories on the west coast. These proposals would have placed the four continental defense commands on a common plane, except that the Eastern and Western commands would have retained control of defensive air units and responsibility for air defense measures and also, of course, would have had the great bulk of the forces assigned to defense missions.46

There was general agreement on the major purpose of the new GHQ recommendations-a sharp reduction in field forces currently assigned to the theater commands. General DeWitt vigorously disagreed with the proposal to remove the Ninth Corps Area and particularly its control of antisabotage measures from his jurisdiction.47 General DeWitt's position was supported wholly or in part in the War Department by the Provost Marshal General, by the War Plans Division, by G-1, and by G-3. All agreed that internal security in the Western Defense Command should remain a defense command responsibility. War Plans wanted both Eastern and Western commands to retain it, and also wanted to keep the theater designations.48

Before any action could be taken on the GHQ recommendations and the objections raised thereto, a new element entered the picture. The decision made in February for a sweeping reorganization of the Army high command required a further modification of the continental defense organization, since the reorganization contemplated placing the corps areas under a new service command. General Marshall therefore approved General Clark's GHQ plan in principle, but he directed that it be revised to conform to the proposed general reorganization of the Army and modified in other minor particulars.49

The general reorganization of 9 March 1942 reduced the War Department to two parts, the civilian offices of the Secretary of War and his assistants, and the military staff headed by the Chief of Staff and consisting of the War Department General and Special Staff divisions. Under the Chief of Staff,

[38]

three major commands-the Army Ground Forces, the Army Air Forces, and the Services of Supply (redesignated Army Service Forces a year later)- absorbed many of the old War Department bureaus and assumed- control of all nondefense functions of the Army within the continental United States. GHQ was abolished, its training functions being absorbed by the Army Ground Forces, and its operating functions by the War Plans Division. This division (soon renamed the Operations Division) became the Chief of Staff's command post for directing operations. Thus the. continental theaters and commands came under the command direction of the War Plans Division, while the corps areas (presently renamed service commands) were placed under the intermediate control of the Services of Supply.50

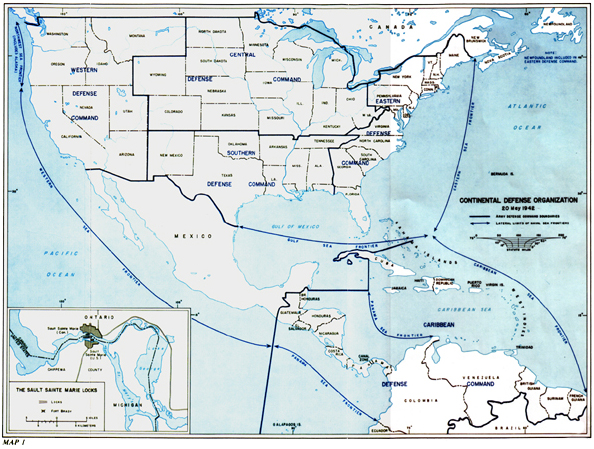

On the same day that the Army published the general reorganization plan, General McNair, who was about to take command of the new Army Ground Forces, proposed to General Marshall a scheme for shifting most of the larger field force units from continental theater to Army Ground Forces control. He also proposed that the First and Fourth Armies remain under the Eastern and Western commands but that they be virtually divorced from the training of large units (corps and divisions), most of which would be put under the Second and Third Armies.51 His recommendations were followed generally in the continental reorganization that became effective on 20 March. (Map 1)

In this reorganization the Eastern Theater of Operations was abolished and the Eastern Defense Command was established within the same area.52 Newfoundland remained under the administrative control of the Eastern Defense Command, and a month later the Bermuda Base Command was similarly attached to it. The Western Defense Command kept its bounds, including Alaska, and its theater status, but at this time the War Department intended that it too would cease to be a theater of operations as soon as the movement of the bulk of the Japanese population into the interior had been completed. All but one of the divisions were taken away from (though not necessarily taken out of) the Eastern Defense Command; the Western Defense Command kept direct control of two divisions, and the other major units within its bounds were placed under a joint control with the Army Ground Forces. The Eastern and Western Defense commanders might never-

[39]

Continental Defense Organization - 20 May 1942

theless use any troops within their bounds in an emergency. Under the initial directive, the Western Defense Command continued to command the Ninth Corps Area, including its supply and internal security functions; in the rest of the United States the corps areas and all their functions passed to the control of the Services of Supply. A fortnight later the War Department also removed the Ninth Corps Area from Western Defense Command control, but the defense commander retained responsibility for Japanese and enemy alien evacuation and for guarding installations, as well as control over troops assigned to carry out these activities. The commanding generals of the Second and Third Armies continued to command the Central and Southern Defense Commands, which were now clearly charged with all Army responsibilities for repelling external surface and air attacks on their areas. Since this directive specifically exempted the air forces within the Central and Southern Defense Commands from defensive missions, the interior defense commands could get air support only by calling upon air units assigned to the Eastern and Western Defense Commands. The First and Fourth Air Forces remained with the Eastern and Western commands, which were also directed to centralize control over all antiaircraft units under the Air Forces' interceptor commands.53

Soon after this reorganization, confusion developed over the control of internal security measures. The War Department on 22 April rectified the situation by authorizing the defense commanders to establish military areas within their commands. Within the military areas, the defense functions of the corps area commanders were to be put under the "direction and supervisory control" of the defense commanders, and otherwise the defense commanders were made "responsible for the planning and execution of all defense measures." 54 Shortly thereafter, and with War Department approval, Generals Drum and DeWitt created military areas coextensive with the boundaries of their commands, and the Southern Defense Command established a military area along the entire Gulf coast. Thus in a wide belt along the coastal frontiers of the continental United States the Army continued to maintain unity of command and centralized control over all means assigned to defense.

The Army Air Forces challenged this unity and centralized control in June 1942 by raising anew the question of responsibility for continental air

[40]

defense, and specifically by asking that the First and Fourth Air Forces be returned to its control. The Air Forces also proposed to reorganize the four fighter commands directly responsible for active air defense measures along geographic lines very different from those of the defense commands. The fighter commands would also be given control of blackouts, dimouts, and radio broadcasts. The War Department passed these proposals on to the defense commanders and to Army Ground Forces for comment.55

Army Ground Forces' single comment on the proposals was, "Centralizing air defense would disrupt unity of command in the defense commands .... Since unity of command is deemed vital, the proposals are not favored." 56 This was the main reason for the War Department's rejection of the Air Forces' requests. Though recognizing that Air control would at least in theory permit a more uniform and better integrated continental air defense system, the War Department held that "the principle of unity of command within the geographical subdivisions is of paramount importance in order that the local defense effort may be coordinated under one commander located at the scene of action." 57 Besides, as General Drum pointed out, by midsummer of 1942 the existing continental defense organization was beginning to function in as efficient a manner as the limited means of the defense commanders permitted. He added a comment worthy of inclusion in any study of organization:

The success or failure of any organization depends as much on its being thoroughly understood by all concerned and competently administered by all echelons as on its original form. The present organization includes all elements essential to an effective defense grouped under a single responsible commander, has been developed for and is particularly well-suited to the assigned mission, and has the advantage of months of trial and error.58

General DeWitt considered that the proposed changes were "dangerously unsound and academic," that they would cripple the entire structure of west coast and Alaskan defense, and that in any event it was absurd to centralize control of west coast air defense in Washington, three thousand or more miles from the scene of action.59 The views of the defense commanders prevailed, and for the time being both the responsibility and the control of air defense

[41]

means remained with the Eastern and Western Defense Commands. The Southern and Central Defense Commands kept the responsibility but never did get independent control of active air defense elements.

Before Pearl Harbor no one raised the issue of Army-Navy unity of command over continental United States defense forces. Immediately thereafter, the Chief of the Army Air Forces proposed that he be given command of all Army, Navy, and Marine Corps air operations launched from continental bases. General Arnold pointed out that in accordance with the RAINBOW g plan the Army Air Forces was responsible for the active air defense of the continental United States, and that the very limited number of combat and patrol aircraft available to both services seemed to require centralized control of those at hand. The War Plans Division recommended to General Marshall the establishment of air unity of command only on the more exposed west coast. 60 The creation of continental theaters of operations during December and the allocation to them of active air defense responsibility changed one premise underlying General Arnold's proposal; and for the time being General Marshall withheld action on it.

The devastating submarine offensive that developed along the Atlantic coast from January 1942 onward, and the continued threat of carrier-based air attack on the west coast, required as much offshore air reconnaissance as the Army and Navy could provide, as well as bombardment aviation ready to strike at submarine and surface vessels. The conduct of air reconnaissance and bombardment operations against ships (unless they comprised a hostile invasion force was a Navy mission, and the theoretical argument for Navy unity of command over such operations was sound enough. But in early 1942 the Navy had very few shore-based planes available for such work, and the Army had to provide the bulk of the planes so employed on both coasts. The Army's air arm in early 1942 was itself too short of trained bombardment units to assign any of them permanently to reconnaissance, which from the Air Forces' point of view was distinctly a secondary mission. Besides, by the end of January both continental theater commanders had worked out satisfactory arrangements with the Navy for co-ordination of air operations over the sea. At General Marshall's request, General Clark of GHQ had also investigated this problem on the west coast in late January. He joined with the local commanders in recommending against any attempt to establish air unity of command there. The Navy had so few planes that almost all of the reconnaissance was being done by the Army anyway, and the co-ordination of

[42]

Army and Navy air operations was as good as could be expected under the circumstances. 61

The Navy rather than the Army was the first to propose a system of command unity for continental frontiers. This development came about in connection with a reorganization and redesignation of naval coastal defense forces. "Sea frontiers" were replacing "naval coastal frontiers"; and these sea frontiers, which were to contain almost all of the Navy's coastal combat forces (ships and planes, were being put under fleet command. The Navy's fleet commander, Admiral Ernest J. King, proposed that the sea frontiers also command all Army air units allocated to overwater operations. General Marshall countered with the proposal "that full unity of command in all continental coastal frontiers and Alaska be vested in the Army over all naval forces which do not normally accompany the fleet." 62

Informal discussion between General Marshall and Admiral King in mid-February produced a tentative agreement on continental unity of command. This arrangement would have placed the Navy's sea frontier commanders under Army command except during fleet operations off the coast. It would have put Army harbor defense forces except antiaircraft units, and all other Army units engaged in operations "involving missions in or over sea areas," under the Navy sea frontier commanders. Thus Army overwater air operations would have been under intermediate Navy command, but the Army theater or defense commander would have retained authority to allot, withhold, or rotate air units for this purpose as he desired. During adjacent fleet operations, the normally allotted sea frontier forces (Army and Navy would have been under fleet command, but this command would not have extended to other Army continental defense forces. Details of the arrangement were still unsettled when General Marshall and Admiral King transmitted an interim joint directive on 25 March vesting the Navy sea frontier commanders immediately with unity of command "over all Army air units allocated by defense commanders for operations over the sea for the protection of shipping and for antisubmarine and other operations against enemy seaborne activities." 63

[43]

Instead of the agreement contemplated during February and March, the Army and Navy in April agreed on a different plan for continental coastal command-the essential difference being that in a "state of non-invasion" unity of command would not extend beyond the scope of the 25 March directive. If invasion threatened, the Army and Navy chiefs were to declare either a "state of fleet-opposed invasion" or a "state of Army-opposed invasion." In the first case, the only change in the normal command relationship would be to put under Army command such local naval defense forces as were exempt from sea frontier command. In the second case, the Army would command all coastal defense forces, including those of the Navy's sea frontiers. Admiral King and General Marshall on 18 April declared a "state of non-invasion" to exist, and within the continental defense commands (except in Alaska) this condition remained unchanged throughout the war. Unity of command in the continental United States during World War II was therefore confined to Navy command of Army air units allocated to the Navy's sea frontier commands for overwater missions.64

After mid-1942 the need for continental defense activity progressively declined, but it was not until September 1943 that the First and Fourth Armies were separated from the Eastern and Western Defense Commands, and the First and Fourth Air Forces taken away from them and restored to the Army Air Forces. Thereafter the theory of Army unity of command was maintained by prescribing that, with War Department approval, the commanding generals of the Eastern and Western Defense Commands might assume command of any air units within their territorial jurisdiction to meet a serious hostile threat.65 On 27 October 1943 the War Department terminated the Western Defense Command's theater status, detached Alaska from it, and designated the latter a separate theater of operations effective 1 November 1943. The Eastern Defense Command absorbed the functions and area of the Central Defense Command at the beginning of 1944, and a year later similarly absorbed the Southern Defense Command. Thus the Army's continental defense structure remaining in 1945 was a mere shell of that created in December 1942, but organizationally it still reflected the principles advocated in prewar planning of wartime unified command responsibility and over-all territorial coverage.

[44]

page created 30 May 2002