Source: FM 100-5, Operations (May 1986), p. 107.

By 1990 those problems were either well in the past or on their way to resolution. Not only were new weapons in place, but military theorists and planners had also broadened the range of possible conflicts to include from small tactical deployments of short duration to a major war over a broad front. Meanwhile, the Army had addressed its internal problems. High standards of recruitment, training, and discipline were in place. In the intervening two decades, the service rebuilt itself around the concept of an all-volunteer force designed to integrate the Army Reserve and Army National Guard into its wartime organization. Army leaders evolved new doctrine for ready forces, focused on the acquisition of new equipment to support that doctrine, tied both together with rigorous training programs, and concentrated on leader development initiatives that increased officer and noncommissioned officer professionalism. By the summer of 1990 the U.S. Army was a technologically sophisticated, highly trained, well-led, and confident force.

26

noted an increase of five Soviet armored divisions in Europe, the continued restationing of Soviet Army divisions farther to the west, and a major improvement in equipment, with T-62 and T-72 tanks replacing older models and with a corresponding modernization of other classes of weapons.2 If general war had come to Europe during the 1970s, the U.S. Army and its NATO allies would have confronted Warsaw Pact armies that were both numerically and qualitatively superior.

The Arab-Israeli War that began on 6 October 1973 intensified concerns about the deadliness of modern weapons as well as the Army's Vietnam-era concentration on infantry-airmobile warfare at the expense of other forces.3 American observers who toured those battlefields began to create a new tactical vocabulary when they reported on the "new lethality" of a Middle Eastern battlefield where, in one month of fighting, the Israeli, Syrian, and Egyptian armies lost more tanks and artillery than existed in the entire United States Army, Europe. Improved technology in the form of antitank guided missiles, much more sophisticated and accurate fire-control systems, and vastly improved tank cannons heralded a far more costly and deadly future for conventional war. Technology likewise brought changes to battlefield tactics. Egyptian infantry armed with missiles enjoyed significant successes against Israeli tank units, bolstering the importance of carefully coordinated combined arms units.4 It seemed clear that in future wars American forces would fight powerful and well-equipped armies whose soldiers would be proficient in the use of extremely deadly weapons. Such fighting would consume large numbers of men and quantities of materiel. It became imperative for the Army to devise a way to win any future war quickly.5

Anew operations field manual, the Army's specific response to new conditions that required new doctrine, was preeminently the work of General William E. DePuy, commander of the new U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC). Surveying conditions of modern warfare that appeared to reconfirm the lessons of World War 11, DePuy wrote in 1976 much of a new edition of Field Manual 100-5 and enlisted the help of the combat arms schools' commandants to revise and improve his ideas. Depuy's Field Manual 100-5 initially touted a concept known as the Active Defense, which once more focused on "the primacy of the defense." The handbook evolved from its first publication to become the keystone of a family of Army manuals that completely replaced the doctrine being practiced at the end of the Vietnam War.6

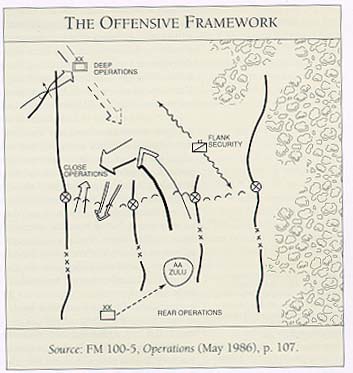

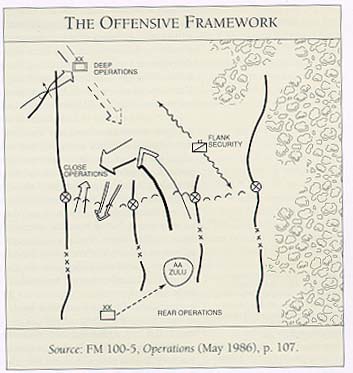

From these modest beginnings the Army's new doctrine, AirLand Battle, slowly emerged. In its final form AirLand doctrine was actually a clear articulation of fundamentals that American generals had understood and practiced as early as World War II, with an appropriate and explicit recognition of the role air power played in making decisive ground maneuver possible.7 The U.S. Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, acknowledged AirLand

27

The Offensive Framework

Source: FM 100-5, Operations (May 1986), p. 107.

Battle's basis in traditional concepts of maneuver warfare by teaching it and making frequent use of historical examples.8

In practical terms, the doctrine required commanders to supervise three types of operations simultaneously. In close operations, large tactical formations such as corps and divisions fought battles through maneuver, close combat, and indirect fire support. Deep operations helped to win the close battle by engaging enemy formations not in contact, chiefly through deception, deep surveillance, and ground and air interdiction of enemy reserves. Objectives of deep operations were to isolate the battlefield and influence when, where, and against whom later battles would be fought. Rear operations proceeded simultaneously with the other two and focused on assembling and moving reserves, redeploying fire support, continuing logistical efforts to sustain the battle, and providing continuity of command and control. Security operations, traffic control, and maintenance of lines of communications were critical to rear operations.

AirLand Battle generated an extended doctrinal and tactical discussion in the service journals after 1976 that helped to clarify and, occa

28

sionally, to modify the manual.9 General Donn A. Starry, who succeeded DePuy in 1977 at the Training and Doctrine Command, directed a substantial revision that concentrated on the offensive and added weight to the importance of deep operations by stressing the role of deep ground attack in disrupting the enemy's follow-on echelons of forces. Changes mainly dealt with ways to exploit what B. H. Liddell Hart described as the indirect approach in warfare by fighting the enemy along his line of least expectation in place or time.

The l982 edition of Field Manual 100-5 stressed that the Army had to "fight outnumbered and win" the first battle of the next war, a concept that required a trained and ready peacetime force. The manual acknowledged the armored battle as the heart of warfare, with the tank as the single most important weapon in the Army's arsenal. Success, however, hinged on a deft manipulation of all of the arms, but especially infantry, engineers, artillery, and air power, to give free rein to the maneuver forces. Using that mechanized force, the doctrine required commanders to seize the initiative from the enemy; act faster than the enemy could react; exploit depth through operations extending in space, time, and resources to keep the enemy off balance; and synchronize the combat power of ground and air forces at the decisive point of battle.

AirLand Battle doctrine had additional utility because it helped to define both the proper equipment for its execution and the appropriate organization of military units for battle. Indeed, the doctrine explicitly acknowledged the growth of technology both as a threat and as a requirement. The U.S. Army and its NATO allies could not match large Soviet and Warsaw Pact forces either in masses of manpower or in masses of materiel. To that extent, AirLand Battle was both an organizational strategy and a procurement strategy. To fight outnumbered and survive, the Army needed to better employ the nation's qualitative edge in technology.

Several factors affected new equipment design. Among the most important was the flourishing technology encouraged by the pure and

29

applied research associated with space programs. Although the big five equipment originated in the years before AirLand Battle doctrine was first enunciated, that doctrine quickly had its effect on design criteria. Other factors were speed, survivability, and good communications, which were essential to economize on small forces and give them the advantages they required to defeat larger, but presumably more ponderous, enemies. Target acquisition and fire control were equally important, since the success of a numerically inferior force really depended on the ability to score first-round hits.

Such simply stated criteria were not easy to achieve, and all of the weapon programs suffered through years of mounting costs and production delays. A debate that was at once philosophical and fiscal raged around the new equipment, with some critics preferring simpler and cheaper machines, fielded in greater quantities.10 The Department of Defense persevered, however, in its preference for technologically superior systems and managed to retain funding for most of the proposed new weapons. Weapon systems were expensive, but defense analysts recognized that personnel costs were even higher and pointed out that the services could not afford the manpower to operate increased numbers of simpler weapons. Nevertheless, spectacular procurement failures, such as the Sergeant York division air defense gun, kept the issue before the public, and such cases kept program funding for other equally complex weapons on the agenda for debate.11

The first of the big five systems, the M1 Abrams tank, weathered considerable criticism and, in fact, began from the failure of a preceding tank program. The standard tanks in the Army inventory had been various models of the M48 and M60, both surpassed in some respects by new Soviet equipment. The XM803 was the successor to an abortive joint American-German Main Battle Tank-70 project and was intended to modernize the armored force. Concerned about expense, Congress withdrew funding for the XM803 in December 1971, thereby canceling the program, but agreed to leave the remaining surplus of $20 million in Army hands to continue conceptual studies.

For a time, designers considered arming tanks with missiles for long-range engagements. This innovation worked only moderately well in the M60A2 main battle tank and the M551 Sheridan armored reconnaissance vehicle, both of which were armed with the MGM51 Shillelagh gun launcher system. In the late 1960s, however, tank guns were rejuvenated by new technical developments that included a fin-stabilized, very high velocity projectile that used long-rod kinetic energy penetrators. Attention centered on 105-mm. and 120-mm. guns as the main armament of any new tank.

Armored protection was also an issue of tank modernization. The proliferation of antitank missiles that could be launched by dismounted infantry and mounted on helicopters and on all classes of vehicles demonstrated the need for considerable improvement. At the same

30

time, weight was an important consideration because the speed and agility of the tank would be important determinants of its tactical utility. No less important was crew survivability; even if the tank were damaged in battle, it was important that a trained tank crew have a reasonable chance of surviving to man a new vehicle.

The Army made the decision for a new tank series in 1972 and awarded developmental contracts in 1973. The first prototypes of the M1, known as the XM1, reached the testing stage in 1976, and the tank began to arrive in battalions in February 1980. The M1 enjoyed a low silhouette and a very high speed, thanks to an unfortunately voracious gas turbine engine. Chobham spaced armor (ceramic blocks set in resin between layers of conventional armor) resolved the problem of protection versus mobility. A sophisticated fire control system provided main gun stabilization for shooting on the move and a precise laser range finder, thermal-imaging night sights, and a digital ballistic computer solved the gunnery problem, thus maximizing the utility of the 105-mm. main gun. Assembly plants had manufactured more than 2,300 of the 62-ton M1 tank by January 1985, when the new version, the MlA1, was approved for full production. The MlA1 had improved armor and a 120mm. main gun that had increased range and kill probability. By the summer of 1990 several variations of the M1 had replaced the M60 in the active force and in a number of Army Reserve and National Guard battalions. Tankers had trained with the Abrams long enough to have confidence in it. In fact, many believed it was the first American tank since World War II that was qualitatively superior to Soviet models.12

The second of the big five systems was the companion vehicle to the Abrams tank: the M2 Bradley infantry fighting vehicle, also produced in a cavalry fighting version as the M3. Its predecessor, the M113 armored personnel carrier, dated back to the early 1960s and was really little more than a battle taxi. The 1973 Arab-Israeli War demonstrated that infantry should accompany tanks, but it was increasingly clear that the M113 could not perform that function because it was far slower than the M1, its obsolescence aside. European practice also influenced American plans for a new vehicle. German infantry used the well-armored Marder, a vehicle that carried seven infantrymen in addition to its crew of three, was armed with a 20-mm. gun and coaxial 7.62-mm. machine gun in a turret, and allowed the infantrymen to fight from within the vehicle. The French Army fielded a similar infantry vehicle in the AMX-1OP in 1973. The Soviets had their BMP-ls, which had a 73-mm. smoothbore cannon and an antitank guided missile, as early as the late 1960s. Variations of the BMP were generally considered the best infantry fighting vehicles in the world during the 1980s. The United States had fallen at least a decade behind in the development of infantry vehicles. General DePuy and General Starry, who at that time commanded the U.S. Army Armor Center and School at Fort Knox, Kentucky, agreed the Army needed a new infantry vehicle and began studies in that direction.

31

In 1980, when Congress restored funding to the Infantry Fighting Vehicle Program, the Army let contracts for prototypes, receiving the first production models the next year. Like the Abrams, the Bradley was a compromise among competing demands for mobility, armor protection, firepower, and dismounted infantry strength. As produced, the vehicle was thirty tons, but carried a 25-mm. cannon and 7.62-mm. coaxial machine gun to allow it to fight as a scout vehicle and a TOW (tube launched, optically tracked, wire command-link guided) missile launcher that enhanced the infantry battalion's antiarmor capability. The vehicle's interior was too small for the standard rifle squad of nine: it carried six or seven riflemen, depending on the model. That limitation led to discussions about using the vehicle as the "base of fire" element and to consequent revisions of tactical doctrine for maneuver. Critical to its usefulness in the combined arms team, however, the Bradley could keep up with the Abrams tank.

By 1990 forty-seven battalions and squadrons of the Regular Army and four Army National Guard battalions had M2 and M3 Bradleys. A continuing modernization program that began in 1987 gave the vehicles, redesignated the M2A1 and M3A1, the improved TOW 2 missile. Various redesigns to increase survivability of the Bradley began production in May 1988, with these most recent models designated the A2.13

The third of the big five systems was the AH-64A Apache attack helicopter. The experience of Vietnam showed that the existing attack helicopter, the AH-1 Cobra, was vulnerable even to light antiaircraft fire and lacked the agility to fly close to the ground for long periods of time. The AH-56A Cheyenne helicopter, canceled in 1969, had been intended to correct those deficiencies. The new attack helicopter program announced in August 1972 drew from the combat experience of the Cobra and the developmental experience of the Cheyenne to specify an aircraft that could absorb battle damage and had the power for rapid movement and heavy loads.14 The helicopter would have to be able to fly nap of the earth and maneuver with great agility to succeed in a new antitank mission on a high-intensity battlefield.15

The first prototypes flew in September 1975, and in December 1976 the Army selected the Hughes YAM-64 for production. Sophisticated night vision and target-sensing devices allowed the pilot to fly nap of the earth even at night. The aircraft's main weapon was the HELLFIRE (helicopter launched fire and forget) missile, sixteen of which could be carried in four launchers. In place of the antitank missile the Apache could carry seventy-six 70-mm. (2.75-inch) Hydra 70 folding-fin rockets. It could also mount a combination of eight HELLFIRE missiles and thirty-eight rockets. In the nose, the aircraft mounted a Hughes 30-mm. single-barrel chain gun.

Full-scale production began in 1982, and the Army received the first aircraft in December 1983. As of the end of 1990 the McDonnell Douglas Helicopter Company (which purchased Hughes in 1984) had

32

delivered 629 Apaches, which equipped 19 active attack helicopter battalions. When production was completed, the Apaches were intended to equip 26 Regular Army, 2 Reserve, and 12 National Guard battalions, a total of 807 aircraft.16

The fourth of the big five systems, the fleet of utility helicopters, had already been modernized with the fielding of the UH-60A Black Hawk to replace the UH-1 Iroquois used during the Vietnam War. The Black Hawk could lift an entire infantry squad or a 105-mm. howitzer with its crew and some ammunition. The new utility helicopter was both faster and quieter than the UH-1.

The last of the big five equipment was the Patriot air defense missile, conceived in 1965 as a replacement for the HAWK (homing all the way killer) and the Nike-Hercules, both based on 1950s' technology. The Patriot benefited from lessons drawn from design of the antiballistic missile system, particularly the highly capable phased-array radar. The solid fuel Patriot missile required no maintenance and had the speed and agility to match known threats. At the same time, its system design was more compact, more mobile, and demanded smaller crews than previous air defense missiles. Despite its many advantages, or perhaps because of the ambitious design that yielded those advantages, the development program of the missile, initially known as the SAM-D (surface-to-air missile developmental), was extraordinarily long, virtually spanning the entire careers of officers commissioned at the end of the 1960s. The long gestation period and escalating costs incident to the Patriot's technical sophistication made it a continuing target of both press and congressional critics. Despite controversy, the missile went into production in the early 1980s, and the Army fielded the first fire units in 1984.

A single battalion with Patriot missiles had more firepower than several HAWK battalions, the mainstay of the 32d Army Air Defense Command in Germany. Initial fielding plans envisaged forty-two units, or batteries, in Europe and eighteen in the United States, but funding and various delays slowed the deployment. By 1991 only ten half-battalions, each with three batteries, were active.

Originally designed as an antiaircraft weapon guided by a computer and radar system that could cope with multiple targets, the Patriot also had the potential to defend against battlefield tactical missiles such as the Soviet FROG (free rocket over ground) and Scud. About the time the first units were fielded, the Army began to explore the possibility that the Patriot could also have an ATBM, or antitactical ballistic missile, mission. In 1988 testing authenticated the PAC-1 (Patriot antitactical ballistic missile capability, phase one) computer software, which was promptly installed in existing systems. The PAC-2 upgrade was still being tested in early 1991.

The Patriot missile, in the hands of the troops in the summer of 1990, was expected to be very effective against attacking aircraft and to have a limited capability to intercept rockets and missiles.17 The Patriot was not, however, a divisional air defense weapon, although it could

33

extend a certain amount of air defense protection over the battlefield from sites in a corps area. Air defense protection of the division still relied on the Vulcan gun and Chaparral missile, stopgap weapons more than twenty years old, and on the light Stinger missile. The failure of the Sergeant York gun project and the continuing difficulties involved in selecting its successor meant that the air defense modernization program essentially stopped forward of the division rear boundary.

The big five were by no means the only significant equipment modernization programs the Army pursued between 1970 and 1991. Other important Army purchases included the multiple launch rocket system (MLRS); a new generation of tube artillery to upgrade fire support; improved small arms; tactical-wheeled vehicles, such as a new 5-ton truck; and a family of new command, control, communications, and intelligence hardware. By the summer of 1990 this equipment had been tested and delivered to Army divisions.

While most of those developments began before the Training and Doctrine Command's first publication of AirLand Battle doctrine, a close relationship between doctrine and equipment swiftly developed. Weapons modernization encouraged doctrinal thinkers to consider more ambitious concepts that would exploit the capabilities new systems offered. A successful melding of the two, however, depended on the creation of tactical organizations that were properly designed to use the weapons in accordance with the doctrine. So, while doctrinal development and equipment modernization were under way, force designers also reexamined the structure of the field army.

America's isolated strategic position posed additional problems, particularly in view of the growth of Soviet conventional power in Europe and an evident Warsaw Pact intention to fight a quick ground war that would yield victory before the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) could mobilize and before the United States could send divisions across the Atlantic.19 Time thus governed decisions that led to forward deployment of substantial ground forces in overseas theaters and the pre-positioning of military equipment in threatened areas. Issues of

34

strategic force projection likewise influenced decisions about the types, numbers, and composition of divisions.

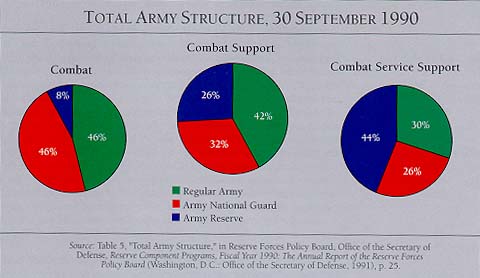

Fiscal and political considerations also loomed large. With the end of the Vietnam War, Congress abolished the vastly unpopular draft, created the all-volunteer force, and cut the Army's appropriation. The consequence was necessarily a much heavier reliance on reserve components, which was known as the Total Army concept.20 Under this principle, the Army transferred many essential technical services and combat units to the Army Reserve and Army National Guard. As an economy measure, some Regular Army divisions were reconfigured with only two active-duty brigades instead of three. Upon mobilization, they were to be assigned a National Guard "roundout" brigade that trained with the division in peacetime.21 Such plans ensured that equipment modernization would extend to the reserve components, with such equipment as M1 Abrams and Bradley fighting vehicles going to National Guard battalions at the same time they were issued to the Regular Army.

Such pragmatism had as much to do with Army organization as what might be called philosophical questions. Differing schools of thought within the Army tended to pull force designers in different directions. There were those, strongly influenced by the war in Vietnam, who believed that the future of warfare lay in similar wars, probably in the Third World. Accordingly, they emphasized counterinsurgency doctrine and light and airmobile infantry organization. Advocates of light divisions found justification for their ideas in the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, when it appeared possible that the United States might have to confront Soviet forces outside the boundaries of Europe. That uncertainty encouraged ideas that called for the creation of light, quickly deployable infantry divisions.

Still, the emphasis within the Army throughout the decade of the 1970s remained on conventional war in Europe, where Chief of Staff General Creighton W Abrams, General DePuy, and like-minded officers believed the greatest hazard, if not the greatest probability of war, existed. They conceived of an intense armored battle, reminiscent of World War II, to be fought in the European theater. If the Army could fight the most intense battle possible, some argued, it also had the ability to fight wars of lesser magnitude.

While contemplating the doctrinal issues that led to publication of Field Manual 100-5, General DePuy also questioned the appropriateness of existing tactical organization to meet the Warsaw Pact threat. DePuy suggested and General Frederick C. Weyand, who succeeded Abrams as chief of staff in 1974, agreed that the Army should study the problem more closely. Thus, in May 1976, DePuy organized the Division Restructuring Study Group to consider how the Army divisions might best use existing weapons of the 1970s and the planned weapons of the 1980s. DePuy's force structure planners, like those con-

35

cerned with phrasing the new doctrine, were also powerfully influenced by the 1973 Arab-Israeli War. 22

The Division Restructuring Study Group investigated the optimum size of armored and mechanized divisions and the best mix of types of battalions within divisions. Weapons capabilities frankly influenced much of the work and had a powerful effect on force design. Planners noted a continuing trend toward an increasing number of technicians and combat support troops (the "tail") to keep a decreasing number of combat troops (the "teeth") in action. In general, the group concluded that the division should retain three brigades, each brigade having a mix of armored and mechanized infantry battalions and supported by the same artillery and combat service units. To simplify the task of the combat company commander, the group recommended grouping the same type of weapons together in the same organization, rather than mixing them in units, and transferring the task of coordinating fire support from the company commander to the more experienced battalion commander. Other recommendations suggested creating a combat aviation battalion to consolidate the employment of helicopters and adjusting the numbers of weapons in various units.23

General Starry, commander of the Training and Doctrine Command, had reservations about various details of the Division Restructuring Study. He was especially concerned that an emphasis on the division and tactics was too limiting. In his view, the operational level of war above the division demanded the focus of Army attention. After reviewing an evaluation of the Division Restructuring Plan, Starry ordered his planners to build on that work in a study he called Division 86.

The Division 86 proposal examined existing and proposed doctrine in designing organizations that could both exploit modern firepower and foster the introduction of new weapons and equipment. In outlining an armored division with six tank and four mechanized infantry battalions and a mechanized division with five tank and five mechanized infantry battalions, it also concentrated on heavy divisions specifically designed for combat in Europe, rather than on the generic division. Anticipating a faster pace of battle, planners also tried to give the divisions flexibility by increasing the number of junior leaders in troop units, thereby decreasing the span of control.

The Army adopted Division 86 before approving and publishing the new AirLand Battle doctrine, yet General Starry's planners assumed that the new doctrine would be accepted and therefore used it to state the tasks the new divisions would be called on to accomplish. Similar efforts, collectively known as the Army 86 studies, pondered the correct structure for the infantry division, the corps, and larger organizations.24 Although Infantry Division 86 moved in the direction of a much lighter organization that would be easy to transport to other continents, such rapidly deployable contingency forces lacked the endurance and, frankly, the survivability, to fight alongside NATO divisions in open terrain. The

36

Total Army Structure, 30 September 1990

Source: Table 5, "Total Army Structure," in Reserve Forces

Policy Board, Office of the Secretary of Defense, Reserve Component Programs,

Fiscal Year 1990: The Annual Report of the Reserve Forces Policy Board (Washington,

D.C.: Office of the Secretary of Defense, 1991) p. 25.

search for a high-technology solution that would give light divisions such capacity led to a wide range of inconclusive experiments with the 9th Infantry Division, officially designated a test unit.

Under the "Army of Excellence" program, military leaders investigated further the plans for a heavier mechanized and armored force begun by Division 86 but reconsidered the role of light divisions. In August 1983 Chief of Staff General John A. Wickham, Jr., directed the Training and Doctrine Command to restudy the entire question of organization. The resulting Army of Excellence force design acknowledged the need for smaller, easily transportable light infantry divisions for the expressed purpose of fighting limited wars. At the same time, the plan kept the heavy divisions proposed by the Division 86 study, although with some modifications.25

Thus the new force structure-five corps with a total of twenty-eight divisions-available to the U.S. Army in the summer of 1990 was the product of almost twenty years of evolving design that had carefully evaluated the requirements of doctrine for battle and the capabilities of modern weapons. Army leaders now believed that they had found a satisfactory way to maximize the combat power of the division, enabling it confidently to fight a larger enemy force. The other vital task had been to devise a training system that imparted the necessary skills so that properly organized and equipped soldiers could carry out their combat and support functions, effectively accomplishing the goals specified by the new doctrine.

37

New Training

The Renaissance infantryman who trailed a pike and followed the flag, like his successor in later wars who shouldered a musket and stood in the line of battle, needed stamina and courage, but required neither a particularly high order of intelligence nor sophisticated training. The modern infantryman, expected to master a wide range of skills and think for himself on an extended battlefield, faces a far more daunting challenge. To prepare such soldiers for contemporary battle, TRADOC planners in the 1970s and 1980s evolved a comprehensive and interconnected training program that systematically developed individual and unit proficiency and then tested that competence in exercises intended to be tough and realistic.26

Individual training was the heart of the program, and the Training and Doctrine Command gradually developed a methodology for training, which clearly defined the desired skills and then trained the soldier to master those skills.27 This technique cut away much of the superfluous and was an exceptional approach to the repetitive tasks that made up much of soldier training. Once the soldier mastered the skills appropriate to his grade, skill qualification tests continued to measure his grasp of his profession through a series of written and actual performance tests.

The training of leaders for those soldiers became increasingly important through the 1970s and 1980s.28 By the summer of 1990 the Training and Doctrine Command had created a coherent series of schools that trained officers in their principal duties at each major turning point in their careers.29 Lieutenants began with an officer basic course that introduced them to the duties of their branch of service and, after a leavening of experience as senior lieutenants or junior captains, returned for an officer advanced course designed to train them for the requirements of company, battery, and troop command. The new Combined Arms and Services Staff School (CAS3) at Fort Leavenworth instructed successful unit commanders in the art of battalion staff duty. The premier officer school remained the Command and General Staff College, which junior majors attended before serving as executive and operations officers of battalions and brigades. Although all Army schools taught the concepts and language of AirLand Battle, it was at Leavenworth that the professional officer attained real fluency in that doctrine. For the selected few, a second year at Fort Leavenworth in the School of Advanced Military Studies offered preparation as division operations officers and Army strategists. Finally, those lieutenant colonels with successful battalion commands behind them might be chosen to attend the services' prestigious senior schools: the Army War College, Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania; the Navy War College, Newport, Rhode Island; the Air War College, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama; and the National War College or Industrial College of the Armed Forces, Fort McNair, Washington, D.C. Beyond those major schools, officers might attend one

38

Map 4 Unified Command Areas 1990

or more short courses in subjects ranging from foreign language to mess management.30 The career officer thus expected to spend roughly one year of every four in some sort of school, either as student or as teacher.

The noncommissioned officer (NCO) corps also required a formal school structure, which ultimately paralleled that of the officer corps.31 Initially, the young specialist or sergeant attended the primary leadership development course at his local NCO academy, a school designed to prepare him for sergeant's duties. The basic noncommissioned officer course trained sergeants to serve as staff sergeants (squad leaders) in their arm or service. Local commanders selected the soldiers who attended that course.

39

Staff sergeants and sergeants first class selected by a Department of the Army board attended the advanced noncommissioned officer course, where the curriculum prepared them to serve as platoon sergeants and in equivalent duties elsewhere in the Army. At the apex of the structure stood the U.S. Army Sergeants Major Academy at Fort Bliss, Texas, where a 22 week course qualified senior sergeants for the top noncommissioned officer jobs in the Army.

Professional development, of course, went hand in hand with both individual training and unit training programs. Progressively more sophisticated programs melded the individual's skills into those of the squad,

40

platoon, company, and battalion. Just as the individual was tested, so were units, which underwent a regular cycle of evaluations, known at the lowest level as the Army Training and Evaluation Program. Periodically, both Regular Army and reserve-component units in the continental United States went to the National Training Center at Fort Irwin, California, where brigade-size forces fought realistic, unscripted maneuver battles against an Army unit specially trained and equipped to emulate Warsaw Pact forces.32 Brigades assigned in Europe conducted similar exercises at the Combat Maneuver Training Center at Hohenfels, Germany, while light forces exercised at the Joint Readiness Training Center at Fort Chaffee, Arkansas.

Tactical units of the Army were subject to further tests and evaluations, the most important of which were exercises to reinforce units in Europe, generally known as REFORGER, the short form for "return of forces to Germany." Similarly, units went to the Middle East in BRIGHT STAR exercises, conducted in cooperation with the armed forces of the Republic of Egypt, and to Korea in TEAM SPIRIT exercises. Periodic readiness evaluations tested divisions' capacity for quick deployment, especially the 82d Airborne Division, long the Army's quick reaction force, and the new light divisions that had been designed for short-notice contingency operations.

As the Army entered the summer of 1990 it was probably better trained than at any time in its history and certainly better trained than it had been on the eves of World War 1, World War II, and the Korean War. Sound training practices produced confident soldiers. Realistic exercises acquainted soldiers with the stress of battle as well as peacetime training could hope to manage. Force-on-force maneuvers, such as those at the National Training Center, tested the abilities of battalion and brigade commanders to make the combined arms doctrine work and confirmed commanders' confidence in their doctrine, their equipment, and their soldiers. But as thorough and professional as Army training was, the most important fact was that all training and exercises were specifically keyed to the doctrinal precepts laid down in Field Manual 100-5. Training brought the diverse strands of AirLand Battle together.

AirLand Battle would have been merely another academic exercise, however, had the Army not attended to the problems of morale, discipline, and professionalism that were obvious at the end of the Vietnam War. By confronting drug abuse, racism, and indiscipline directly, leaders gradually corrected the ills that beset the Army in 1972. Schools and progressive military education played a part, as did strict qualitative management procedures that discharged the worst offenders. More importantly, officer and NCO education stressed the basics of leadership and responsibility to correct the problems that existed at the end of the Vietnam War. Over time, in one of its most striking accomplishments, the Army cured itself.33

41

Army accomplishments over the years after the end of the Vietnam War were impressive. By 1990 the claim could reasonably be made that the service had arrived at a sound doctrine, the proper weapons, an appropriate organization, and a satisfactorily trained, high-quality force to fight the intense war for which General DePuy and his successors had planned. International developments in the first half of the year seemed, however, to have made the Army's modernization unnecessary. The apparent collapse of Soviet power and withdrawal of Soviet armies into the Soviet Union itself, the disintegration of the Warsaw Pact, and the pending unification of Germany removed the justification for maintaining a powerful U.S. Army in Europe. In view of all of these developments, the immediate political question was whether the nation needed to maintain such a large and expensive Army. In the interests of fiscal retrenchment, the Army projected budgets for the following five years that would decrease the total size of the active service from approximately 780,000 in 1989 to approximately 535,000 soldiers in 1995.34

Even after the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait and even while Army units were in the midst of frantic preparations for movement to Saudi Arabia, Army organizations concerned with "downsizing" the service to meet the long-range strength ceilings continued to work. Army QUICKSILVER and VANGUARD task forces had deliberated on the size of the Army's field and base force structure, recommending inactivations that now directly affected the forces preparing to deploy to the Middle East. The "Army 2000" study group at Headquarters, Department of the Army, considered the implications of such decreases in size and pondered the ways a smaller Army could continue to carry out its major missions. Among the major actions that the group managed in July and August 1990 was a scheduled command post exercise named HOMEWARD BOUND, designed to test a possible removal of Army units from Europe.35 Army 2000 staff officers also weighed concerns voiced at the highest levels of the service that the drive to save defense dollars not produce another "hollow" force and thus reproduce the disaster of Task Force SMITH in July 1950 at the start of the Korean War.36

Department of the Army planners in operations and logistics found themselves in the anomalous situation of pulling together the combat and support units scheduled for deployment to the Middle East at the same time that their colleagues in personnel were proceeding with plans for a reduction in force. The latter plans were temporarily suspended when the Army's deployment to Saudi Arabia was announced, and orders went out likewise suspending retirements from active duty and routine separations from the Army. Still, uncertainty about the future, both for individuals and for major Army units, persisted as the Army prepared for overseas service and, possibly, for war.

42

Despite improvements in personnel, doctrine, and weapons, the Army that went to Saudi Arabia was largely inexperienced. The limited combat actions in Grenada and Panama, which were not real tests of AirLand Battle doctrine, gave very few soldiers experience under fire. The URGENT FURY operation in Grenada involved fewer than 8,000 Army soldiers, with actual Army combat being limited to the 1st and 2d Battalions of the 75th Ranger Regiment and certain units of the 82d Airborne Division. In fact, Army strength on the island during the period of combat probably did not exceed 2,500, and the heaviest combat, occurring during the first hours of the landing on 25 October 1983, was borne by Company A, 1st Battalion, 75th Rangers.37 The fighting during Operation JUST CAUSE in Panama was similarly limited, although more Army units, totaling about 27,000 soldiers, participated.

In neither case was there serious opposition of the kind the Army had been training for decades to meet. Far and away the most important aspects of Operations URGENT FURY and JUST CAUSE were their utility in testing the effectiveness of U.S. joint forces command-and-control procedures, areas in which both operations, as well as subsequent joint deployments, revealed continuing problems.38 Joint doctrine, a matter of concern since the Goldwater-Nichols Defense Reorganization Act of 1986 emphasized it, was far from complete.39 Not until 1990 did the Army, acting for the Joint Chiefs of Staff, complete drafts of Joint Publication 3-0, Doctrine for Unified and Joint Operations, and prepare Joint Publication 3-07, Joint Doctrine for Low-Intensity Conflict, as a test manual to be issued late in the year. The two most important volumes, Campaign Planning and Contingency Operations, remained to be written.40

Still, the important questions that remained blunted the edge of pervasive official optimism as the Army deployed to the Middle East during the summer of 1990. Chief among them was how well new weapons would perform. The M1 series Abrams and M2 and M3 Bradleys had never faced combat. Neither had the multiple launch rocket system, the Patriot missile, the AH-64A Apache, or modern command, control, and communications mechanisms that were supposed to weld those sophisticated implements into a coherent fighting system.41 Problems with weapons procurement over the preceding decade had conditioned many to doubt how well the new high-technology weapons would perform. As a result, media pundits and military commentators warned of a long and bloody war of attrition if the Middle East crisis could not be resolved through negotiation.42

The volunteer Army was a second source of concern. Overshadowed in the public eye by discussions about the efficacy of modern weapons and within the Army by the immediate concerns of preparing for war, the question of how to guarantee an adequate stream of trained replacements and a sufficient supply of new equipment loomed behind the possibility that the ground battle would be long and costly. The Army of July 1990, regulars and reservists, was the Army

Table 1 THE JOINT COMMAND STRUCTURE, 1990

| UNIFIED | SPECIFIED |

|---|---|

|

Geographic Specialized |

Strategic Air Command (SAC) Forces Command (FORSCOM) |

with which the nation would have to fight any war. Lacking the mechanism of an active draft, the Army had no way to assure replacements for extensive battle casualties. Similarly, without a mobilization of the industrial base, weapons production remained at a peacetime level.

The United States Central Command, responsible for northeast Africa, Southwest Asia, and the surrounding waters, commanded U.S. forces during DESERT SHIELD and DESERT STORM. General H. Norman Schwarzkopf, Jr., commander of Central Command, controlled all of the Army, Navy, Marine, and Air Force elements assigned to the theater of operations. He reported to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Colin Powell. The Army component of Central Command (ARCENT) was the Third United States Army, colocated in peacetime with Forces Command at Fort McPherson, Georgia. At the beginning

44

of the operation, Central Command, which had no forces assigned to it during peacetime, requested troops from Forces Command, which allocated units stationed in the continental United States.

Gen. H Norman Schwarzkopf

The Department of the Army performed its crisis role in accordance with service roles and missions as modified under the Goldwater-Nichols Act. In an attempt to streamline and create a more responsive and efficient Defense Department, Congress had altered the internal relations between the civilian secretariat and the Army Staff within the Department of the Army headquarters. While the secretariat acquired greater administrative and financial control, the Joint Chiefs of Staff gained increased responsibility in the operational area.44 Under the new guidelines, the Joint Chiefs remained a corporate body with the service chiefs as members, but the chairman became the principal military adviser to the secretary of defense and the president. Reorganization gave the chairman of the Joint Chiefs the option of consulting with the service chiefs but did not require it. In addition, the joint chairman no longer had to forward to the secretary of defense, the National Security Council, or the president the dissenting and alternative views of the other members of the Joint Chiefs.45 Congress also gave the operational unified and specified commanders greater authority over subordinate forces and provided them a greater role in acquisition of resources and materiel for specific military contingencies.

Throughout the crisis, the Army Staff supported ARCENT logistically and administratively. The staff had responsibility for ensuring that units identified to deploy into the theater were the best available for the mission; that they were adequately manned, equipped, and trained; that

United States Central Command, headquartered at MacDill Air Force Base, Tampa, Florida

45

other Army and Department of Defense assets were available to sustain and support the force; and, if not, that they were obtained and delivered for deployment in a timely manner. As a result, the staff was heavily involved in virtually every aspect of the force buildup and sustainment planning and execution. In addition, it had responsibility for coordination among the Army's major commands in the United States, with the Army component commands in the unified and specified commands, with the Joint Chiefs and the defense secretariat, and with civilian industry and agencies for procurement, contracting, and a broad spectrum of other areas related to the national industrial base. It also managed Department of Defense programs in support of the civil sector and other government agencies.

The Army's chief of staff, General Carl E. Vuono, took pride in his personal familiarity with virtually every major Army commander in the field and in the support base. In providing the Army resources necessary to support their plans and prepare for contingencies, General Vuono worked closely with these commanders, assuring that any disagreements over resources were resolved before they became issues that required intervention by the secretary of defense. In particular, he and General Schwarzkopf had known each other for more than three decades. This personal relationship created an atmosphere of mutual trust and confidence.46

From the Army Staff in the Pentagon to individual soldiers in rifle companies, many strands came together to make up the Army of DESERT STORM. Overall, the soldiers preparing for deployment to Saudi Arabia in the late summer of 1990 shared a pervasive confidence in their units, their weapons, and their own capabilities. Their leaders were equally sure that, in the doctrine they had so thoroughly rehearsed, they held the keys to battlefield success. The Iraqi invasion of Kuwait chanced to come at a moment when the United States Army was completing its twenty-year process of modernization and reform. The Army of 1990 was without a doubt the most proficient and professional military force the United States had ever fielded at the beginning of a foreign war.

Notes

1 On problems within the military at the end of the Vietnam War, see William L. Hauser, America's Army in Crisis (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973); Paul L. Savage and Richard A. Gabriel, Crisis in Command: Mismanagement in the Army (New York: Hill and Wang, 1978); Charles C. Moskos, Jr., "The American Combat Soldier in Vietnam," Journal of Social Issues 31 (1975); Data on Vietnam Era Veterans (Washington, D.C.: Reports and Statistics Service, Office of the Controller, Veterans Administration, June 1971); Lee N. Robbins, The Vietnam Drug User Returns (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1974); Edward L. King, The Death of the Army (New York: Saturday Review Press, 1972); and Comprehensive Report: Leadership for the 1970s, USAWC Study of Leadership for the Professional Soldier (Carlisle Barracks, Pa.: Army War College [AWC], 1971).

2 For summaries of the military balance, see Amos A. Jordan and William J. Taylor, American National Security: Policy and Process (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1981); and John M. Collins, American and Soviet Military Trends Since the Cuban Missile Crisis (Washington, D.C.: Center for Strategic and international Studies, 1978).

3 Chaim Herzog, The Arab-Israeli Wars: War and Peace in the Middle East (New York: Random House, 1982), introduces the extensive literature on the war. Also see Herzog, The War of Atonement: October 1973 (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1975).

4 Jac Weller, "Infantry and the October War: Foot Soldiers in the Desert," Army 24 (August 1974).

5 TRADOC Annual Rpt of Major Activities, FY 1974, pp. 14-19; and TRADOC Annual Rpt of Major Activities, FY 1975, ch. 1.

6 Quote from John L. Romjue, From Active Defense to AirLand Battle: The Development of Army Doctrine 1973-1982 (Fort Monroe, Va.: TRADOC, 1984), pp. 14-15. To survey the doctrine's evolution, see ibid., passim, and Donn A. Starry, "To Change an Army," Military Review (March 1983).

7 Field Manual (FM) 100-5, Operations (May 1986); Robert A. Doughty, The Evolution of U.S. Army Tactical Doctrine, 1946-1976, Leavenworth Paper I (Fort Leavenworth, Kans.: Command and General Staff College JCGSCI, 1979); Romjue, From Active Defense to AirLand Battle; Paul H Herbert, Deciding What Has to Be Done: General William E. DePuy and the 1976 Edition of FM 100-5, operations, Leavenworth Paper 16 (Fort Leavenworth, Kans.: CGSC, 1988); and Ronne L. Brownlee and William J. Mullen III, Changing An Army: An Oral History of General William E. DePuy, USA Retired (Carlisle Barracks, Pa.: Military History Institute [MHI1, 1985).

8 Field Manual 100-5 uses historical examples to illuminate the discussion of doctrine. The Command and General Staff College tactics instruction similarly uses examples of high intensity World War II operations. The same was true of Leavenworth's battle analysis class. Christopher R. Gabel, The 4th Armored Division in the Encirclement of Nancy (Fort Leavenworth, Kans.: CGSC, 1986), p. 23.

9 For a sample of the discussion, see "Army's Training and Doctrine Command: Getting Ready to Win the First Battle ... and the Rest," Armed Forces Journal International 114 (May 1977); William E. DePuy, "FM 100-5 Revisited," Army 30 (November 1980), John S. Doerfel, "The Operational Art of the AirLand Battle," Military Review 62 (May 1982); Robert A. Doughty and L. D. Holder, "Images of the Future Battlefield," Military Review 58 (January 1978); Gregory Fontenot and Matthew D. Roberts, "Plugging Holes and Mending Fences," Infantry (May-June 1978); William S. Lind, "Some Doctrinal Questions for the United States Army," Military Review 57 (March 1977), Dan G. Loomis, "FM 100-5 Operations: A Review," Military Review 57 (March 1977); John M. Oseth, "FM 100-5 Revisited: A Need for Better Foundation Concepts?," Military Review 60 (March 1980); Donn A. Starry, "A Tactical Evolution-FM 100-5," Military Review 58 (August 1978); Robert E. Wagner, "Active Defense and All That," Military Review 60 (August 1980), and Huba Wass de Czege and L. D. Holder, "The New FM 100-5," Military Review 62 (July 1982).

10 These themes were treated most thoroughly in the years after 1980 by the Military Reform Caucus, an informal group of members of Congress, military analysts, and journalists. On the caucus and its criticisms, see MS, Theresa Kraus, The Military Reform Caucus [Center of Military History (CMH), 1987]. Reformers focused on concrete issues of how to train, equip, and organize military forces, rather than on questions of strategy, and often used Dana Rasor's Project on Military Procurement to communicate with the press. Members held diverse views, but among those criticizing the complexity and costs of weapons were Walter Kross, Military Reform: The High-Tech Debate in Tactical Air Forces (Washington, D.C.: National Defense University [NDU] Press, 1985); and James Fallows, National Defense (New York: Random House, 1981). For a general survey, see Asa A. Clark et al., The Defense Reform Debate: Issues and Analysis (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984).

11 MS, Bruce R. Pirme, Duster to DIVAD: The Army's Search for a Radar-Directed Gun [CMH, 1987].

12 Orr Kelly, King of the Killing Zone: The Story of the MI, America's Super Tank (New York: W. W. Norton, 1989); Steve E. Dietrich and Bruce R. Pirnie, Developing the Armored Force: Experiences and Visions. An Interview With MG Robert J. Sunell, USA Retired (Washington, D.C.: CMH, 1989).

13 Department of the Army (DA), Weapon Systems: United States Army, 1991 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1991), p. 17; Bruce R. Pirme, From Half-Track to Bradley: Evolution Of the Infantry Fighting Vehicle (Washington, D.C.: CMH, 1987); "M2A2/M3A2 Bradley Fighting Vehicles," Army 41:6 June 1991).

14 On the relationship between close air support issues, requirements for aircraft designed to participate in the direct ground battle, the competition for missions, and the design of the Cheyenne helicopter, see Charles E. Kirkpatrick, The Army and the A-10: The Army's Role in Developing Close Air Support Aircraft, 1961-1971 (Washington, D.C.: CMH, 1987).

15 As distinguished from simple lowlevel flight, nap of the earth is flight close to the earth's surface, following the contours of the ground as closely as possible. . Airspeed and altitude vary according to terrain, weather, and the enemy situation.

16 Weapon Systems: United States Army, 1991, p. 21; "The AH-64A Apache Attack Helicopter," Army 41:4 (April 1991).

17 "Army's Patriot: High-Tech Superstar of Desert Storm," Army 41:3 (March 1991); "Modernization Program Systems Prove Themselves in the Desert," Army 41:5 (May 1991) For further information on the Patriot system, see Appendix A.

18 On the development of Army divisions between World War II and the 1970s, see John C. Binkley, "A History of U.S. Army Force Structuring" Military Review 57 ,February 1977): 67-82; A. J. Bacevich, The Pentomic Era: The U.S. Army Between Korea and Vietnam (Washington, D.C.: NDU Press, Robert P. Haffa, Jr., Rational , Prudent Choices: Planning U.S. Forces (Washington, D.C.: NDU 1988); William W. Kaufmann, Planning Conventional Forces, 1980 (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, 1982); Virgil Ney, Evolution of the U.S. Army Division 1939-1968 (Fort Belvoir, Va.: Combat Developments Command [CDC], 1969); John J. Tolson, Airmobility, 1961-1971, Vietnam Studies (Washington, D.C.: CMH, 1973); Maxwell D. Taylor, Swords and Plowshares (New York: W. W. Norton, 1972); and Glen Hawkins, United States Army Force Structure and Force Design Initiatives, 1939-1989 (Washington, D.C.: CMH, 1991).

19 For a discussion of this and related issues, see Haffa, Rational Methods, Prudent Choices: Planning U.S. Forces; and Kaufmann, Planning Conventional Forces, 1950-1980.

20 On the volunteer Army, see Willard Latham, The Modern Volunteer Army Program: The Benning Experiment, 1970-1972 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1974), and Harold G. Moore and Jeff M. Tuten, Building a Volunteer Army: The Fort Ord Contribution (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1975).

21 In reaction to the failure to use the reserves in Vietnam, General Creighton Abrams, during his term as Army chief of staff, deliberately structured the Army Reserve and National Guard with respect to the Regular Army so that it would literally be impossible to go to war without calling up the citizen-soldiers. See Lewis Sorley, "Creighton Abrams and Active-Reserve Integration in Wartime," Parameters 21:2 (Summer 1991): 35-50.

22 John L. Ronrue, A History of Army 86, 2 vols. (Fort Monroe, Va.: TRADOC, 1982).

23 Complete recommendations are in Division Restructuring Study (Fort Monroe, Va.: TRADOC, 1977).

24 See Rorrijue, A History of Army 86, vol. 2. chs. II, III, IV.

25 See The Army of Excellence Final Report, 3 vols. (Fort Leavenworth, Kans.: U.S. Army Combined Arms Combat Development Activity Force Design Directorate, 1984).

26 Critiques from within the Army, such as Arthur S. Collins, Jr., Common Sense Training: A Working Philosophy for Leaders (San Rafael, Presidio Press, 1978), spurred changes to training methods.

27 TRADOC Regulation 350-7, Systems Approach to Training (1988), discusses the design of Army training; FM 25-100, Training the Force (1988), outlines the principles of all Army training. In 1990, FM 25-101, Battle-Focused Training, applied those principles to battalions and smaller organizations.

28 Major studies include Officer Personnel Management System (OPMS) Task Group, Review of Army Officer Educational System, 3 vols. Washington, D.C.: DA, 1971), known as the Norris Report; [TRADOC OPMS Task Group], Education of Army Officers Under the Personnel Management System, 2 vols. (Fort Monroe, Va.: TRADOC, 1975); [Study Group for the Review of Education and Training for Officers], Review of Education and Training For Officers (RETO), 5 vols. Washington, D.C.: DA, 1978) and [Study Group for the Chief of Staff, Army], Professional Development of Officers Study Final Report, 6 vols. (Washington, D.C.: DA, 1985).

29 The Army outlined the skills it expected an officer to develop at each grade in the Military Qualification Standards (MQS). Standard Testing Program (STP) 21-I-MQS, Military Qualification Standards I: Manual of Common Tasks (Precommissioning Requirements) (Washington, D.C.: DA, 1990); STP 21-II-MQS, Military Qualification Standards II: Manual of Common Tasks for Lieutenants and Captains (Washington, D.C.: DA, 1991).

30 Army Regulation (AR) 351-1, Individual Military Education and Training (1987), outlines the structure of the Army's formal schools, for the scope of resident training, see DA Pamphlet 351-4, Army Formal Schools Catalog (1990).

31 DA Pamphlet 600-25, U.S. Army Noncommissioned Officer Professional Development Guide (Washington, D.C.: DA, 1987).

32 Daniel P. Bolger, Dragons at War: 2-34 Infantry in the Mojave (Novato, Calif.: Presidio Press, 1986), depicts the realism of NTC training. The Army's goal was to send each active maneuver battalion to the National Training Center every two years, and each reserve-component roundout maneuver battalion every four years. Army Focus (Washington, D.C.: DA, 1990), p. 32. See also Anne E. Chapman, The Origins and Development of the National Training Center, 1976-1984 (Fort Monroe, Va.: Office of the Command Historian, United States Army Training and Doctrine Command, 1992).

33 For evidence of progress, see the Department of the Army Historical Summary (Washington, D.C.: CMH, annually) for fiscal years 1972-1986. They show a progressive decrease in the "indicators of indiscipline." At the same time, standards of recruitment and retention improved. Ninety percent of Army recruits graduated from high school in 1986, compared to 54.3 percent in fiscal year 1980.

34 Various sections of Army Focus (September 1990) consider these questions. Especially see "National Security Environment," pp. 5-14.

35 Army Concepts Analysis Agency CAA) for Deputy Chief of for Operations and Plans (DCSOPS), 6 Aug 90, sub: CPX HOMEWARD BOUND.

36 Memo for Commander/Chief, CMH, 11 Jul 90, sub: Selcom Meeting, 10 July 1990. For details on the Task Force SMITH debacle, see Roy E. Appleman, South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu (June-November 1950) , United States Army in the Korean War (Washington, D.C.: CMH 1961), ch.6.

37 CMH Fact Sheet, 9 Apr 91, sub: U.S. Army Operation URGENT FURY Statistics.

38 The broadest survey of the era, although one that hews very much to orthodox judgments about Army performance in these skirmishes, is Daniel P. Bolger, Americans at War: 1975-1986, An Era of Violent Peace (Novato, Calif.: Presidio Press, 1988).

39 For a summary, see MS, Theresa Kraus, DOD Reorganization and the Army Staff [CMH, 1990]. A discussion of earlier attempts at reorganization is Edgar F. Raines, Jr., and David R. Campbell, The Army and the Joint Chiefs of Staff: Evolution of Army ideas on the Command, Control, and Coordination of the U.S. Armed Forces, 1942-1985 (Washington, D.C.: CMH, 1986).

40 Army Focus (September 1990), p. 23.

41 The limited combat in Grenada and Panama did not rigorously test the systems used by Army units in those actions. In Panama, for example, eleven AH-64A aircraft flew a total of 246 combat hours, of which 138 were at night. Other weapon and communications systems were similarly unproven. A General Accounting Office analysis of hardware employment in Grenada (URGENT FURY), Lebanon, Libya (ELDORADO CANYON), and deployments to the Persian Gulf (EARNEST WILL) showed "significant problems" with joint communications equipment and several categories of precision-guided munitions. [United States General Accounting Office], Report to the Chairman, Committee on Government operations, House of Representatives, U.S. Weapons: The Low-Intensity Threat Is Not Necessarily a Low-Technology Threat, USGAO/PEMD-90-13 (March 1990), app. II.

42 such discussions began as soon as the possibility of war arose. The best articulated warnings about the dangers of a ground war came from analyst Edward Luttwak in various television interviews as the virtually unopposed air campaign unfolded. Also see, for example, Gary Hart, "The Military's New Myths," New York Times, 30 Jan 91; "Intimations of a Long War," Washington Post, 25 Jan 91; "M1A1 will get stem test from T-72," Washington Times, 24 Jan 91.

43 Title 10, United States Code (USC), secs. 161-67.

44 HQ, DA, Report to Congress: Army implementation of Title V, DOD Reorganization Act of 1986 (Washington, D.C.: DA, 1987), pp. i-3; Association of the United States Army (AUSA), Fact Sheet: Department of Defense Reorganization Act of 1986, A Primer (Arlington, Va.: AUSA, 1987), pp. 1-5.

45 Draft Reorganization Bill, Talking Paper, DAMO-SSP, 3 Feb 87, included with Defense Organization: Meeting with Senators Goldwater and Nunn, filed with materials regarding Department of Defense Reorganization, 1985-1987, Historical Resources Branch, CMH.

46 Interv, Brig Gen Harold W. Nelson with General Carl E. Vuono, USA (Ret.), 3 Aug 92, Washington, D.C. Also see Bob Woodward, The Commanders (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1991), pp. 303-04.

page updated 7 June 2001