Military Traffic Management Command Terminal, Rota, Spain, the site

of transshipment operations during DESERT SHIELD

In response to a request by General Schwarzkopf, General Colin Powell, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, asked the services to begin identifying additional units for deployment. On 10 August 1990, Forces Command issued a deployment order for follow-on forces to Southwest Asia. The message provided an intelligence summary from which to plan and identify deployment requirements and shortages. The summary identified at least six Iraqi divisions in Kuwait with an additional five near Al Basrah. The summary concluded by positing courses of action that the Iraqis might take in response to the initial deployment: invading Saudi Arabia to occupy possible American entry points and seize oil production facilities; interdicting the air- and seaports of debarkation by conventionally or chemically armed aircraft and missiles; or attacking U.S. ships as they passed through the Persian Gulf with aircraft, mines, and missiles.

The message also outlined the force deployment objective. By 16 September Forces Command intended to deploy to Southwest Asia the two remaining ground maneuver brigades of the 82d Airborne Division, the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault), and the 24th Infantry Division (Mechanized). Added to the troop list to give the XVIII Airborne Corps more punch were the 3d Armored Cavalry and the 1st Cavalry Division. Thus, by mid-September Forces Command wanted to move into Saudi Arabia about 50,000 soldiers, over 700 tanks, 564 M113s, 572 M2 and M3 Bradleys, 145 AH-64 Apaches, 294 155-mm. self-propelled how-

70

itzers, 48 Patriot missile launchers, and thousands of other items of equipment ranging from generators to computer vans.1 The soldiers would travel by air and their equipment by sea.

Commanders of the installations where the units were located and of the units themselves were instructed to deploy according to a series of staggered dates. For example, General Edwin H. Burba, Jr., of Forces Command told the commander of Fort Bliss to send one Patriot air defense missile battalion to Southwest Asia no later than 18 August. He also directed the commander of III Corps, at Fort Hood, Texas, to move the 1st Cavalry Division and the 1st Brigade, 2d Armored Division, out by 16 September.

In identifying combat units to meet Central Command's needs, General Burba had an important decision to make. Both the 24th Infantry Division and the 1st Cavalry Division had only two active-duty brigades. The others were designated as roundout brigades of the Army National Guard, which were designed to bring the divisions up to full strength when mobilized. However, as of 8 August the reserve components had not been called, so the National Guard brigades were not available to augment the deploying divisions.

Despite the misgivings of many, the Department of Defense was firmly committed to the roundout system. From 1973 to 1989 the Army had grown from thirteen to eighteen divisions while maintaining a post-Vietnam personnel strength of around 785,000. That was accomplished partly by manning some continental United States active-duty divisions with only two maneuver brigades; the third divisional, or roundout, brigade would come from the reserve component. By mid-l990 six active Army divisions contained roundout brigades, all but one from the National Guard.

The 24th Infantry Division stationed at Fort Stewart, Georgia, was the first heavy division slated for deployment. The 48th Infantry Brigade of the Georgia National Guard served as its roundout brigade. When the 24th received deployment notification, no political decision had been made on the issue of reserve mobilization. This and other factors led Forces Command to select the Regular Army's nondivisional 197th Infantry Brigade at Fort Benning, Georgia, to deploy instead of the 48th.

71

Burba regarded the 197th as the best-qualified, readily available force to bring the 24th Division to full strength.

THE ROUNDOUT BRIGADE PROGRAM

| Active Component | Reserve Component |

|---|---|

| Army National Guard | |

| 1st Cavalry Division (Armored) | 155th Armored Brigade (Miss) |

| 4th Infantry Division (Mechanized) | 116th Cavalry Brigade (Idaho/Oreg/Nev) |

| 5th Infantry Division (Mechanized) | 256th Infantry Brigade (La) |

| 9th Infantry Division (Motorized) | 81st Infantry Brigade (Wash) |

| 10th Mountain Division (Light) | 27th Infantry Brigade (NY) |

| 24th Infantry Division (Mechanized) | 48th Infantry Brigade (Ga) |

| Army Reserve | |

| 6th Infantry Division (Light) | 205th Infantry Brigade |

Breaking the roundout connection between the 48th Brigade and its parent 24th Division touched off some debate. The nature of the dispute seemed surprising because everyone had been bracing for a hostile reaction to the calling of the reserve components. The outcry, however, came not from the public, but from reservists aggrieved because they were not called.

The roundout program had been designed to bring to full strength seven divisions stationed in the United States to stop a full-scale Warsaw Pact attack in central Europe or to meet a major contingency outside of Europe while maintaining strength along the Iron Curtain. Those scenarios presumed a full or even total mobilization. Despite public discussion to the contrary, it had never been assumed by the Army Staff that any of the roundout units would deploy with their parent organizations in a short-term scenario that did not involve the Soviet Union. The United States had enough combat forces to deal with the immediate crisis in August 1990. Retired Lt. Gen. John W. Woodmansee, Jr., former V Corps commander, summed up the feeling of many in the active components when he said, "it's patently absurd to take relatively untrained troops when you have trained troops available."3 Had the 48th deployed, it would have left behind in the United States ten highly trained heavy divisional brigades of the active component, an unhappy prospect for many in the Army leadership. Given the Capstone program, however, many reservists and the congressional delegations that represented them had assumed that in all circumstances the roundout unit would deploy with the parent division.

There was a second crucial reason for not calling the roundout brigades into active service. The call-up authorization granted on 22

72

August was limited in number and function. The Army's share of that 48,800-soldier increment, 25,000 combat support and combat service support personnel, was based directly on the number requested by Chief of Staff General Carl E. Vuono.4 The active components had adequate combat forces available and needed support personnel. The early mobilization of the Army National Guard combat brigades would have eaten into the initial call-up authorization without providing the support forces that the Regular Army needed most.

Other issues affected the call-up of the reserves. The most obvious was congressional support in terms of appropriations that had been dedicated to strengthening combat elements of the reserve components. Another concern centered on the question of Total Army viability. The total force policy was much on the minds of congressional leaders because the Persian Gulf crisis coincided with force reduction planning following the end of the Cold War. Implicit was their assumption that the reserve components would play an even larger role.

Congressman G. V. "Sonny" Montgomery of Mississippi raised those points in letters on 15 August to President Bush and on 24 and 28 August to Secretary of Defense Cheney.5 Those letters became part of a public debate that intensified in September. On the congressional side, in addition to Montgomery, the issue was joined most vocally by Congressman Les Aspin of Wisconsin, Chairman of the House Committee on Armed Services; Congresswoman Beverly B. Byron of Maryland; and Congressman Dave McCurdy of Oklahoma. They directed their observations to Secretary Cheney in a joint letter on 6 September 1990.6 In particular they stressed the need to test the Total Army policy, which by inference was associated with the roundout units. They tied the need for that test to the forthcoming force restructuring and reductions debate.

In reply, Secretary Cheney cited two reasons for not authorizing the call of the roundout brigades. First, he said, the military had not asked for them. Second, "the statutory time limits on the use of Selected Reserve units imposes artificial constraints on their employment." He was referring to the restrictions in Section 673b of Title 10, United States Code, that limited the call-up to ninety days renewable for ninety days. Too much of that time, he explained, would be spent on mobilization, training, and movement to make the remaining time in the Middle East worthwhile. He concluded that point by saying that "Congress has within its power the ability to lengthen the period of maximum service under Section 673b, to permit more effective use [of] Selected Reserve units."7 Those observations clearly implied that the failure to call the roundout units revolved around the time available to the units to be actively used. The difficulty lay with congressionally imposed limitations.

That issue, as old as the Constitution, involved the executive powers of the commander in chief and the legislative war-making powers. The operative sections of Title 10 had been deliberately crafted to require

73

close consultation between the executive branch and Congress if the president wanted to use extensive force. The president had the power to use as many as 1 million reservists for two years simply by declaring a national emergency. That was a step the administration did not want to take in early September. Even within the 200,000 troops available under presidential authority, Secretary Cheney only authorized the call-up of the minimum needed for the short run.

The debate continued into October By that time, the House Armed Services Committee characterized the failure to call combat reservists as "anti-reserve bias."8 Led by those critics, Congress took up Secretary Cheney's challenge and crafted an exception to Section 673b. Signed into law on 5 November, the amendment extended the period for which the president could activate reserve-component combat units from a total of 180 days to 360 days for fiscal year 1991. The provision weakened any argument that a lack of time to mobilize, train, deploy, serve, and redeploy prevented call-up of the roundout units.

At Forts Hood and Bliss the pace was as intense as it was at Bragg, Campbell, and Stewart. Although the 1st Cavalry Division and 3d Armored Cavalry were to be the last major Army combat elements to deploy, that fact did not lessen the sense of urgency. Early in the movement, both sent liaison officers to the XVIII Airborne Corps headquarters to study the experiences of units that had already gone. On 22 August the 3d Armored Cavalry began moving its equipment to Beaumont, Texas. Over the next five days twelve trains delivered the regiment's heavy equipment to the port. Its aircraft flew to Beaumont, where they were disassembled and packed for shipment.

The 1st Cavalry Division at Fort Hood, with the 1st Brigade of the 2d Armored Division attached, began moving to the Port of Houston on 4 September and started loading ships two days later.10 The division's first ships, of an eventual fifteen, were on their way by 9 September and arrived in Saudi Arabia on 3-4 October. By the first week in November the division was in the desert setting up its defensive positions and training for combat.

Deployment activities were not limited to the United States. On 15 August the Joint Chiefs of Staff ordered the United States European Command to send an attack helicopter brigade from the United States

74-75

Map 6 U.S. Combat Units Available for Desert Storm 1990

76

Map 7 U.S. Combat Units Available for Desert Storm 1990

77

Army, Europe, to Saudi Arabia. The 12th Aviation Brigade, assigned to the V Corps in Germany, met the requirement. The brigade's deployment started a steady stream of troops and materiel that flowed from Europe to the Middle East to support Operation DESERT SHIELD. It also set the precedent for transfer of American troops from their NATO roles in Europe to service in Southwest Asia. Through the remainder of August, in addition to the 12th Aviation Brigade, an air ambulance company and four chemical reconnaissance platoons deployed. By the end of the month the 12th began moving by land and air to the port of Livorno, Italy, to meet its ships. By 13 September the brigade had loaded three vessels bound for Saudi Arabia. The 12th arrived on 2 October and was in its assembly area by early October.

78

Military Traffic Management Command Terminal, Rota, Spain, the site

of transshipment operations during DESERT SHIELD

The MTMC headquarters in Falls Church, Virginia, managed its far-flung activities through four subordinate commands. The Eastern Area ran U.S. Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico ports from Bayonne, New Jersey. The Western Area operated U.S. Pacific ports in addition to Japanese and Korean operations from San Francisco, California. The European Division handled western European facilities from near Rotterdam, the Netherlands. The Transportation Engineering Activity in Newport News, Virginia, provided technical support.

The command's 5,900-member worldwide staff included 2,154 civilians who were Army reservists and 22 who were Navy reservists. These people, who served as individual mobilization augmentees or in a few highly specialized units, provided the surge capacity needed to operate the ports during the deployment. Their units, among the least well known of Army organizations, did jobs that were vital to the movement of troops. Deployment control units, each of which had an authorized strength of 39 officers and 44 enlisted people, broke down into twelve teams that helped units at their home stations prepare equipment for movement to a port of embarkation and served as a liaison with the port. Transportation terminal units of 28 officers and 47 soldiers managed the traffic operations of military ports. They prepared loading plans and manifests, received equipment, supervised the overall operation, and contracted labor to load the ships. The unit commander also usually commanded the port. Another type, port security detachments of 3 officers and 64 enlisted personnel, managed overall port security in conjunction with police, Coast Guard, and other security forces. Cargo documentation detachments of 8 enlisted personnel documented the loading, unloading, and transferring of cargo from one form of transportation to another. They worked at all types of terminals and could document the movement of 500 short tons of cargo or 480 containers per day. Railway support units of 5 officers and 142 enlisted people provided railway equipment operating specialists. The scope of support this organization offered was vast: in the first sixty days, 520,000 tons of cargo and 107,000 passengers deployed.

79

Thirty more reservists volunteered to help on 11 August, and the equipment from the 101st Division began arriving the next day. It was only on 13 August that his command got permission to accept the volunteers who had offered their services and started work. In twenty days that ad hoc unit directed the loading of all ten ships of 101st Airborne Division equipment.

Port operations at Beaumont, Texas (top), and Sunny Point, North Carolina (bottom)

The tempo could not be maintained without whole units operating within a normal structure. On 27 August, during the first reserve call-up, five terminal units were activated. Col. Richard Simmons, commander of the 1181st U.S. Army Transportation Terminal Unit, who had already been working at the port with twenty-four other volunteer members of his unit, took command of the Port of Jacksonville.

The same process unfolded at Savannah, the port of embarkation for the 24th Infantry Division and the 197th Infantry Brigade. Volunteers from the 1182d and 1189th U.S. Army Transportation Terminal Units from Charleston, South Carolina, began the process. The 1185th U.S. Army Transportation Terminal Unit from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, diverted to Savannah, Georgia, from Wilmington, North Carolina, where it was to have begun its annual two-week training exercise on 13 August, soon joined them. When the two-week tour ended, the 1185th went on extended active duty with the other terminal units. The first ship with 24th Division equipment left Savannah on 13 August. The 1185th, commanded by Col. Donald R. Detterline, stayed on and worked at Savannah, proceeding to Wilmington and Sunny Point, North Carolina; Bayonne; Newport News; and Rotterdam. The unit ended its long tour of duty on 24 July 1991.

The use of volunteers, mobilization augmentees, and units on annual training in addition to Regular Army forces was a makeshift, but workable, approach to opening and operating military ports throughout the United States. Once the decision to activate the reserves was made, a more permanent structure developed. On 27 August the Army activated five terminal units, two port security units, and a deployment control unit in addition to other movement control units. These units supported the entire East Coast deployment from home installation to port operations at Bayonne, Wilmington, Savannah, Jacksonville, Houston and Beaumont, Texas, and the Military Ocean Terminal at Sunny Point, a specialized facility for handling munitions. When the reinforcement of VII

80

Corps forces began in November, the 1181st, 1182d, 1185th, and 1189th terminal units deployed to Amsterdam and Rotterdam in the Netherlands; to Antwerp, Belgium; and to Bremerhaven, Germany. The 1190th U.S. Army Deployment Control Unit set up headquarters in Stuttgart, Germany, to support deployment of VII Corps to Saudi Arabia.

The Transportation Command, responsible for moving the joint force and its equipment, had other priorities and, at times, requirements simply exceeded availability of resources. On 11 August, for example, XVIII Airborne Corps needed the equivalent of 40 C-141 aircraft to move 4,000 passengers and a portion of the vehicles that belonged to the 82d Division's ready brigade. It expected only thirty-one.12 The number of aircraft increased only when the Civil Reserve Air Fleet, a program for the emergency use of the nation's civil air carriers, was activated on 17 August for the first time in its forty-year existence.13

Shipping was scarcer than aircraft. Four ready reserve fleet ships expected to be available by 17 August were delayed for almost a week. Mechanical problems beset other vessels.14 Moreover, some ships were not designed to expedite the loading of equipment. The majority were break-bulk carriers onto which cranes lifted individual pieces of equipment through deck hatches. Once under way, those ships were also slower than the fast sealift ships.

On 11 August the first of the fast sealift ships, the USNS Capella and USNS Altair, steamed into the Port of Savannah to begin loading the 24th Infantry Division's equipment. The reservists and regulars of the ready brigade of the 24th Infantry Division and the 1185th U.S. Army Transportation Terminal Unit of the Army Reserve began loading the brigade's equipment on the Capella in midafternoon and finished in less than forty-eight hours. The vessel sailed for Saudi Arabia on 13 August, loaded with 88 M1 tanks, 26 M2 infantry fighting vehicles, 12 M3 cavalry fighting vehicles, 9 multiple launch rocket system launchers, 6 AH-IS Cobras, 4 OH-58 Kiowas, and 3 self-propelled 20-mm. Vulcan air defense guns. The Vulcans were carried on deck, along with Stinger antiaircraft missiles, to provide air defense for the ship in case of attack after it passed through the Strait of Hormuz and crossed the Persian Gulf heading for the Saudi ports. Also on board were one hundred soldiers of the 24th Infantry Division who accompanied the unit's equipment and would help unload the ship at the end of the two-week voyage.

81

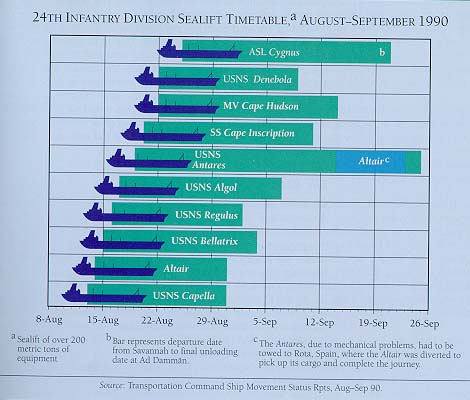

24th Infantry Division Sealift Timetable, a August-September 1990

a Sealift of over 200 Metric tons of equipment

b Bar represents departure date from Savannah to final unloading

date at Ad Damman.

c The Antares, due to mechanical problems had to be towed

to Rota, Spain, where the Altair was diverted to pick up its cargo and

complete the journey.

Source: Transportation Command Ship Movement Status Rpts, Aug-Sep 90.

Problems with the USNS Antares delayed completion of the 24th Division's movement. The vessel departed Savannah on 19 August with elements of the 24th's support command and Aviation Brigade on board. While en route the ship had serious boiler problems and had to be towed to Spain for repairs. With the Antares unable to complete the trip, the USNS Altair was diverted from its return voyage to the United States to take on the cargo of the Antares. The Altair sailed from Rota, Spain, on 14 September. The breakdown of the Antares delayed completion of the 24th Division's deployment by over two weeks. The division finished its move to Saudi Arabia on 25 September with the unloading of the Altair. The ten-ship sealift took forty-six days to move over 200 metric tons of equipment.15

The first ship carrying 101st equipment, the MV American Eagle, left Jacksonville on 19 August with 9 105-mm. towed howitzers, 3 Cobras, 3 Kiowas, and 20 Chinook transportation helicopters. The ship began

82

unloading in Saudi Arabia on 9 September. The division finished its movement to Saudi Arabia thirty days later.16

The 3d Armored Cavalry started loading its first ship on 27 August at Beaumont. Four days later it set sail. During its first day at sea the ship suffered mechanical problems and returned to port for quick repair. The problem was less serious than the trouble that beset the Antares, and the vessel returned to sea within several days. From 26 August to 10 September the 3d loaded five ships. Another of its transports suffered mechanical problems and was towed to Jacksonville for repair.17 Although the regiment's original schedule called for arrival in Saudi Arabia before the end of September, it did not finish unloading its equipment until 17 October.18

The request contained 63,400 combat support and combat service support personnel in 614 units and 11,000 medical personnel. The 48th Infantry Brigade of the Georgia National Guard and the 155th Armored Brigade of the Mississippi National Guard, each containing 2,750 troops, were also included in the initial package although it was projected that they would not deploy. In draft letters prepared on 14 August for the president's signature to notify Speaker of the House of Representatives Thomas S. Foley (Washington) and President Pro Tempore of the Senate Robert C. Byrd (West Virginia) of the call-up, General Powell added a paragraph indicating that reserve combat troops might be needed in the Middle East. However, he later agreed with a Joint Chiefs recommendation that only those units actually requested by the service components of Central Command should be activated for deployment and that the units to be mobilized for U.S. service should be justified on a case-by-case basis by the service secretaries.21

The first three weeks of August were filled with long hours of difficult analysis, coordination, and negotiation. Faced with a formidable task, the staff planners tended toward large numbers within a projected 200,000 limit. The Bush administration, though prepared to authorize

83

as many reserves as necessary to support operations, wanted no more than the minimum required. Every unit called had to serve an essential mission and be seen by the public as being absolutely necessary for the task.22 The administration and the Army wanted to avoid the perception that the lives of reservists, their families, and their communities were being disrupted for no good reason. The results of those considerations could be seen in the declining numbers of required troops in each revision of the proposed force list.

On 15 August Secretary Cheney asked President Bush to execute his authority to call up the Selected Reserve, while the final numbers were still being worked out.23 Several days later, Bush decided to activate reserve forces. On 22 August he promulgated the decision in Executive Order 12727. In letters to Congressman Foley and Senator Byrd informing them of his decision, the president did not mention reserve combat units.24

Having received presidential authorization, Secretary Cheney directed the Army to call up Selected Reserve units, but many fewer than had originally been discussed. In the last briefing Cheney received on the day the decision was announced, General Powell asked for a total of 46,703 reservists from all services. That number included 4,912 Army reservists for call-up in August and an additional 19,822 by 1 October. Secretary Cheney authorized the call-up of 48,800 people for all services. Of those, the Army was authorized to activate 25,000 reservists drawn exclusively from combat support and combat service support units, thus eliminating the combat brigades from immediate call-up.25

The first reserve call-up triggered a major debate that lasted throughout the crisis and remains unresolved. Despite the Total Army policy in place since 1973, major currents worked against it. One was a fear within the administration that a large reserve call-up would generate a hostile backlash against the Persian Gulf policy and ruin efforts to build a domestic and international consensus. Policy makers were aware of the antiwar sentiment of the Vietnam War years, and there remained a lingering institutional memory of the negative response in 1961 during the Berlin crisis when the 49th Armored Division of the Texas National Guard and Wisconsin's 32d Infantry Division were called but not actively used. The public had little understanding of or patience with the concept of activating those divisions to reconstitute the forces in the United States to prepare for further emergencies. There was also an underlying fear among some government officials that a reserve call-up would trigger a public reaction against the use of "civilians," now reservists rather than draftees, in anything less than a total effort of the World War II variety. Those considerations seem to have played a role in limiting the number of reservists called in the first three months of the crisis.

Skepticism over the use of roundout maneuver brigades in the combat divisions also fueled the controversy. Long before the crisis, civilian military analysts had raised questions about the ability of National Guard

84

maneuver units to reach the proficiency of their Capstone partners.26 That skepticism also existed in the Regular Army. Maj. Gen. Robert E. Wagner, commander of the Army Reserve Officers Training Corps Command, said publicly in 1986 what many believed. "Our service is literally choking on our reserve components....Our reserve components are not combat-ready, particularly National Guard combat units. Roundout is not working. Those units will not be prepared to go to war in synchronization with their affiliated active-duty formations."27

As the public debate continued, Forces Command worked to create a reserve force list. Once Secretary Cheney gave his approval, units were alerted on 24 August, and fifty-seven units containing almost four thousand reservists were activated on 27 and 28 August. In addition to troop unit personnel, by the end of August 2,500 Army National Guard and Army Reserve volunteers and over 1,000 individual mobilization augmentees were on active duty.

Although the units were typical of the hundreds that followed in later months, they reflected the needs of the early days of the crisis. They varied in size from the 142d Military Intelligence Battalion's five-member prisoner-interrogation teams of the Utah National Guard to the 295-soldier 5064th U.S. Army Reserve Garrison from Detroit, Michigan. Functionally those units in the August call-up fell into four distinct areas: support for the continental United States, movement support, support of the deployed force, and medical support.

The first two categories consisted of relatively small numbers. Within the United States, the 3320th, 3397th, and 5064th U.S. Army Reserve Garrisons provided administrative support at mobilization stations, and a U.S. Army Reserve Intelligence Support Element was assigned to Forces Command. Those involved in assisting the movement of troops, equipment, and supplies to the ports of embarkation and from ports of debarkation in Saudi Arabia did a wide array of jobs. Twenty-six transportation units, including cargo documentation, movement control, freight consolidation and distribution, transportation terminals, and port security detachments, were activated. The terminal units were those that had already been serving under two-week orders. The six-member 1158th Transportation Detachment (Movement Control) of the Colorado National Guard was alerted on 24 August and activated on the twenty-seventh. It arrived at Fort Carson, Colorado, on the thirtieth, and became the first guard unit to deploy to Southwest Asia on 9 September.

85

Desert evacuation exercise by 44th Medical Brigade medics

during the conflict-the Medical Specialist Corps, Dental Corps, Medical Service Corps, Veterinary Corps, Nurse Corps, and Medical Corps. The process of medical mobilization and the transition to wartime presented some unique problems.

The Health Services Command provided both peacetime and wartime care for service members and their families. Those duties required the simultaneous existence of two types of medical organizations. The peacetime organization provided a complete range of medical care in permanent U.S. and overseas facilities. After Iraq's invasion of Kuwait, the system continued to provide normal medical care but took on new duties. The Health Services Command provided medical and dental support for the mobilization stations; expanded the hospital beds available in the continental United States by 4,000; provided personnel to Central Command, Europe; and deployed reserve-component

86

units. It also certified that all the deploying reserve medical units met the personnel, equipment, and training criteria.

Medical operations in support of Operation DESERT SHIELD began the second week of August when the Army Medical Department received the dual mission of deployment to Southwest Asia and the continuous care of soldiers and their families in the United States and overseas. By the end of the month the 44th Medical Brigade, the 47th Field Hospital, the 28th Combat Support Hospital, and the 5th Surgical Hospital (Mobile Army) were on their way. At first the deployment created a shortage of trained medical personnel. More than 1,700 volunteers-from the Retired Reserve, from the Individual Ready Reserve, and from the Selected Reserve's Individual Mobilization Augmentees and Troop Program Units-responded to the request for help and were placed in health care facilities from which the active-duty people were deploying.

The Army Medical Department prepared to meet the intense needs of combat operations by providing care ranging from combat medics at the forward line to field hospitals in the communications zone. With the onset of Operation DESERT SHIELD, medical assets began to shift to support the field units. The key to this transition was the Professional Officer Filler System (PROFIS). This system matched Regular Army medical professionals with vacancies in deploying medical units. As the medical staff shifted to deploying units, Army leadership looked to the reserve components for the remaining manpower necessary to accomplish the mission.

During previous mobilizations, increased demands had been matched by a declining need to provide dependent and retired health care. In August, however, General Vuono instructed The Surgeon General, Lt. Gen. Frank F Ledford, Jr., to continue medical service to all beneficiaries. That verbal instruction was followed early in September lay a strongly worded letter from Congressman John P. Murtha of Pennsylvania, Chairman of the Defense Subcommittee of the House Committee on Appropriations, to Secretary Cheney. Murtha said that the failure to replace deploying medical personnel on a one-to-one basis with reservists degraded patient care and increased expenses by raising the costs of CHAMPUS, the Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Uniformed Services that used civilian providers reimbursed by the government to treat dependents and retirees when uniformed military care was not available. "This," Murtha stated, was "totally unacceptable and must be remedied." 28

General Powell disagreed with some specific points of Congressman Murtha's letter.29 The patient load at many U.S. facilities, such as Fort Stewart, the home of the 24th Division, had gone down dramatically, precluding the need for one-on-one replacement. General Powell also noted that while CHAMPUS was expensive, so was calling up additional reservists. Finally, he pointed out that calling too many reservists could have a detrimental impact on the civilian health care system.

87

Secretary of Defense Cheney, balancing Congressman Murtha's concerns and General Powell's appraisal, communicated to the service secretaries the mandate to support DESERT SHIELD, to continue all peacetime care, and to maintain the same level of CHAMPUS expenditures. Beginning in August, the Health Services Command moved quickly within that framework to activate more medical reservists to support its mission.

Fifteen hundred Army Medical Department reservists from eleven units were activated on 28 August 1990. A problem immediately became apparent as mobilization progressed. The stateside hospitals needed replacements for health care professionals who had gone into deploying units under PROFIS. Planners had always assumed that individual ready reservists would fill that need during mobilization. The reserve activation of August 1990, however, was taking place under terms of Title 10, United States Code, Section 673b, which limited the call-up to members of the Selected Reserve. This included only specifically assigned individual mobilization augmentees and members of units that were designed to remain intact.

The Health Services Command used 800 of the medical personnel who had volunteered in the first days of the crisis, but they were not sufficient to fill the need.30 It appeared that entire hospitals and dental detachments would have to be activated to get enough health care providers, including physicians, dentists, nurses, physician assistants, and Army Medical Service Corps officers. Such unit call-ups would activate many unneeded reservists, who in turn would use many of the limited spaces that Cheney had authorized. In addition, the medical personnel were not needed in large numbers at any one hospital.

A solution was devised that met legal requirements and limited the original call-up to the professional care givers who were needed. Each Army unit had a unique unit identification code, a combination of letters and numbers. From the 3297th U.S. Army Hospital, a 1,000-bed U.S. Army Reserve hospital stationed in Chamblee, Georgia, the Health Services Command created five "derivative" or modified units, each with a similar code number but distinct in the last digit. They contained only professional health care providers and no administrative personnel. Those new units, the 3297th U.S. Army Hospital sections 2, 3, and 4 plus the 3297th U.S. Army Hospital Augmentation, were activated on 28 August with only the health care professionals from the parent unit. The new units did not serve as teams, however, because the personnel were not needed in large numbers at any one hospital. Individuals were dispersed to hospitals across the country as needed.

In that way, eighteen of the twenty-four U.S. Army hospitals in the contiguous United States were eventually called to active duty in two phases. In phase one, beginning in August, nine derivative hospitals and two derivative dental units were activated. Then, in phase two, the remainder of the hospitals were alerted on 14 December and called to active duty on 8 January 1991. That process was used for other types of

88

89

units including the training divisions, schools, and intelligence units among others.

On 6 December 1990, the U.S. Army Forces Central Command Medical Group (Echelons Above Corps) (Provisional) was established. The Central Command Medical Group was the higher headquarters for four medical groups and several direct reporting units in the Southwest Asia theater of operations. The VII Corps and the XVIII Airborne Corps provided additional hospitals and medical resources tailored to meet the mission. More than 24,000 health care personnel deployed to Southwest Asia. Theater-wide, the forty-four hospitals provided 13,580 beds in four countries. After the liberation of Kuwait, a combat support hospital was located in Kuwait City.

Combat support elements contained 1,900 military policemen, including the headquarters of the 112th and 160th Military Police Battalions and twelve military police companies. Given the history of Iraq's use of chemical weapons against the Iranians and Kurds, the threat of chemical warfare was taken seriously throughout the crisis, and of the seven chemical units activated, six were nuclear, biological, and chemical defense and decontamination units.

Combat service support units formed the largest segment of the September call-up. Although the medical contingent of that phase was small, it included the first operational units-four helicopter ambulance detachments-deployed. Twenty-three quartermaster units included fifteen water purification and distribution elements and six petroleum supply units. Five ordnance conventional ammunition companies added another one thousand troopers to the list. The largest single element of the September call-up was provided by the Transportation Corps. Twenty-one truck companies and twenty-three movement and transportation management units were included in the 4,100 soldiers that constituted over 30 percent of the total.

Vehicles were a major part of the equipment supply problem that had always plagued the reserve components and were of particular concern during DESERT SHIELD. Although Congress had made large appropriations for the reserves in recent years, at the time of the call-up many units did not meet the Army's deployment standard. The issue involved the serviceability of equipment and its compatibility with

90

the newest equipment issued to the Regular Army. The National Guard alone at the end of September was short 10,000 5-ton trucks nationwide.31 In the case of the guard, units were brought to adequate readiness by sharing equipment among the units within individual states. During the crisis almost 3,300 pieces of equipment were redistributed between units in Alabama alone.32 When shortages persisted the Department of the Army assigned vehicles right off the assembly line. The 1461st Transportation Company (Light Truck) of the Michigan National Guard sent its drivers from Fort Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania, to Marysville, Ohio, to pick up 50 M939A2 5-ton trucks as they rolled out of the factory. The 253d Transportation Company (Light/Medium Truck) of the New Jersey National Guard got its on-the-road training the same way, convoying 46 new M923A2 trucks from the Ohio factory to Fort Dix, New Jersey.

By October the units called in August and September had been integrated into the Regular Army and were serving in every phase of the operation except as infantry, armor, and artillery units. They were joined then by thirty-eight additional units containing 4,700 troops. These were called up in three increments, the largest on 11 October, with two additional units activated on both 15 and 19 October. As in September the bulk of these reserve forces supported the combat force defending Saudi Arabia. As part of this call-up thirteen truck companies and a transportation battalion headquarters were activated. The Quartermaster Corps provided eight petroleum, water, and heavy material supply units. Five combat support maintenance companies, a supply company, two postal units, and a personnel services company rounded out the combat service support elements. Combat support troops included an aviation company and three combat engineer companies. In addition to these companies, a derivative unit headquarters of the 416th Engineer Command was activated. The 416th Engineer Command Headquarters (minus), commanded by Maj. Gen. Terrence D. Mulcahy, became the command element of ARCENT's 416th Engineer Group. Those turned out to be the last units called up during the initial deterrent or defensive phase of Operation DESERT SHIELD.

At the mobilization stations, units made final prepara-

91

tions for movement. They completed all the administrative tasks involved in preparation for overseas movement, were brought to full personnel and equipment strength, and undertook further training as time allowed. There, arriving units fell under the command of the garrison commander, who was supported by the installation garrison and a readiness group.33

Installation garrisons and jointly located active troop units, also often in the process of deployment, provided administrative support. In addition, many reserve-component units were called up specifically to support the mobilization effort. The 3397th U.S. Army Reserve Garrison from Chattanooga, Tennessee, for example, was one of four such units that provided installation support. It was mobilized on 27 August and served at Fort Campbell, Kentucky. Although it maintained its unit status, it was completely integrated into the active garrison already in place. That support included medical screening and care, bringing units to full strength, issuing equipment, and training within the limited time and facilities available.

As in all previous mobilizations, administrative processing was complex and time consuming. Although requirements and guidelines had been in place for years, many units and individual reservists lacked such basic necessities as wills, checking accounts and the accompanying "Sure-Pay"-direct pay deposit-paperwork, and panographic X-rays.

Dental and other medical conditions caused some serious delays but did not hinder deployment of many individuals. In some reserve units as many as 50 percent of the soldiers lacked dental X-rays and many needed extensive dental work, although that did not affect deployability. In addition, many reserve officers over forty years old had not received cardiovascular screening. That also did not affect deployability unless serious problems were discovered during routine screening, but it slowed the mobilization process somewhat. In one unit screening delays affected half of the officers.34 Requirements for eyeglasses and hearing aids caused similar delays.

Army readiness groups of the Regular Army played major roles in mobilization of reserve units. Thirty readiness groups operated in the continental armies, eight each in the First and Second United States Armies, five in the Fourth and Sixth United States Armies, and four in the Fifth United States Army. In peacetime they helped reserve-component units reach and maintain high levels of readiness and during wartime assisted them to mobilize and deploy. The readiness groups were organized into combat arms, combat support, and administrative branches, and each branch was further subdivided into small teams. When alert orders were issued, readiness groups dispatched liaison teams to home stations to facilitate administrative preparation. Once mobilization was ordered, each readiness group formed mobilization assistance teams that joined the units at their home station, helped them move to the mobilization station, supervised postmobilization training, and ultimately provided the garrison commander with the information needed for a decision on unit validation.

92

At the mobilization stations the mobilization assistance teams helped plan and supervise predeployment training and advised the commander about the status of units at the station. Ultimately, it was the responsibility of the garrison commander to validate each unit, that is, to certify that each unit met the personnel, equipment, and training criteria for deployment. The readiness group, however, actually supervised the validation process.

Throughout that process the headquarters of the continental armies were key coordinators. They ensured that units in their respective geographical areas were brought to full equipment and personnel strength. They achieved that primarily through a distribution process. At home and mobilization stations, personnel were balanced between units, leaving some units understrength and unavailable for activation. If the mobilization stations did not have the necessary resources to accomplish the task, then the continental army took over and redistributed troops and equipment between installations within its geographical boundaries. The continental armies referred personnel problems they could not resolve to Forces Command. Forces Command in turn worked with the Army Personnel Command, which distributed personnel at the national level.

Forces deploying from the United States therefore faced serious equipment shortages. Given sufficient time, they could take equipment from other units not deploying. For example, the 5th Infantry Division at Fort Polk, Louisiana, filled radio shortages in the 197th Infantry Brigade. When sharing did not work, deploying units identified shortages and submitted requisitions through the supply system, hoping those requisitions would be expedited for delivery before deployment. In the days after notification of deployment the 24th Infantry Division placed requisitions valued at $50 million for vehicles, ammunition, flak jackets, uniforms, and other requirements. 35

93

Basically units deployed with what they had, not necessarily the best the Army owned. Modern equipment generally went first to units that were deployed in forward areas. Units in the United States waited their turn. For example, armor units in Europe had MlAl tanks equipped with 120-mm. cannons and chemical protection, while the 24th Infantry Division had M1 tanks with the less powerful 105-mm. guns and outdated chemical protection. The 197th Infantry Brigade had some even older M60A3s from the previous generation of tanks. The Army reassessed its modernization plans while concentrating on getting a credible deterrent force into the Saudi Arabian desert.

Ammunition was of paramount importance. There were critical shortages of artillery antitank ammunition, ball and tracer ammunition for M16A2 rifles, dual-purpose artillery munitions, and others.36 As of 8 August the 24th Infantry Division had only enough stock at its local ammunition supply point to provision a single brigade-size task force. Other units faced similar situations, and Army depots worked overtime during August. At Letterkenny Army Depot in Pennsylvania, for example, workers pulled ammunition from storage in over 900 ammunition storage igloos and loaded as many as fifteen trucks a day for shipment to deploying units.37

Once alerted, soldiers at Forts Bragg, Benning, Stewart, Campbell, Hood, Bliss, Huachuca (Arizona), and elsewhere, found themselves in the throes of preparing for deployment. Not only did they prepare themselves, but they also repaired and packed equipment. One battalion of the 1st Brigade, 2d Armored Division, had to replace the gun tubes on 21 of its 58 tanks, put new sets of track on 24 others, and changed 430 roadwheels before it could finish loading its materiel.38 Ammunition accompanying the troops was issued and stored on vehicles. Medical sets were checked, stocked, and packed.

Some critical equipment such as communications gear and attack helicopters went with the soldiers by air, but the bulk of the equipment that went by sea had to be railroaded, driven, or flown to the ports to be loaded for the two-week voyage to Saudi Arabia. Once the ships were loaded, the soldiers returned to their home stations to train on individual and unit skills and to enjoy their last days at home before they had to begin processing for overseas movement. Their air movement overseas would be geared to the expected arrival date of their equipment.

Every component of the Army supported the deployment effort. The Army Materiel Command provided the equipment and supplies that the Army needed to fight. It also took on the added task of providing equipment, vehicles, and parts to allied countries in accordance with guidance and priorities from the Department of Defense. Depots, supply facilities, and shops throughout the country produced the equipment, parts, ammunition, meals, and other items essential to the maintenance and sustainment of the force.

94

Despite heroic efforts on the part of agencies such as the Army Materiel Command, deploying units faced critical shortages of supplies and equipment. Scarcely one week after the initial deployment order, the XVIII Airborne Corps reported shortages in desert camouflage uniforms and chemical protective overgarments at Fort Bragg.39 Other installations also reported shortages of uniforms and overgarments.40

On 18 August additional chemical protective overgarments were released for issue from U.S. Army, Europe, stocks. U.S. stocks of desert camouflage uniforms were also released as the logistics system increased production. On 19 August Secretary Cheney and General Vuono learned that the Army had enough desert uniforms to support the deploying forces at two sets per soldier. Meanwhile, the Defense Personnel Support Center, which had enough cloth on hand to make 200,000 more, redirected two contractors to produce the uniforms and expedited the procurement of an additional 1 million.41 While efforts continued to increase production, the vast stores of equipment and supplies in Europe helped ease immediate needs. On 21 August a shipment of chemical suits went from Europe to Fort Bragg. Later a direct supply line between Europe and Saudi Arabia met needs for clothing, tents, radios, and other scarce items of supply.42

The largest and most significant shipment of items from European stocks during the first phase of DESERT SHIELD involved tanks. In October Secretary Cheney's office approved a request to replace the Army's older models in Saudi Arabia. Over 600 newer MlA1 tanks with 120-mm. guns and chemical overpressure protection were shipped from pre-positioned stocks in Germany.

Although the shipment of tanks from Germany was by far the largest force modernization activity during DESERT SHIELD, there were others. From the beginning of the deployment, modernization efforts enhanced ARCENT capabilities. These efforts were managed centrally from Army headquarters at the Pentagon. As General Vuono had promised, they proceeded without disrupting readiness. Modernization ranged from the shipment of improved kitchen trailers to off-the-shelf purchases of tactical locating devices and, in other areas, took the form of incremental improvements to current models of equipment. Overall, the changes had a positive effect on troop morale. 43

Incremental improvements were particularly important in the case of helicopters. Operations in the Saudi desert gave Army aviation units some rare challenges. The pilots had some desert flying experience from training at the National Training Center at Fort Irwin and during Central Command's biennial exercise BRIGHT STAR in Egypt conducted with Egyptian forces, but flying and maintaining aircraft in Saudi Arabia was unique. The fine desert sand eroded the leading edges of rotor blades, clogged fuel lines and particle separators, and pitted windscreens. The Army's aviation community studied each problem, looking for solutions with the least effect on operations and readiness. To protect rotor blades

95

from erosion caused by airborne sand, a special paint, and later a special tape, was applied to the blades' leading edge. Improved particle separators were developed and shipped to the area of operations for installation. Windscreen covers were tested and purchased. They were particularly important because pitted windscreens affected the ability of the pilots to fly at night.

The erosion caused by the blowing sand distorted images in the pilots' night vision goggles and increased the chances of accidents. Resolving problems associated with flying and fighting at night was crucial. The Army's ability to do so would provide it a clear-cut advantage over Iraqi forces.

Maintaining the morale of soldiers, the bedrock of an Army's efficiency,

became one of the commander's most important tasks. In the austere physical,

cultural, and social environment of Saudi Arabia the soldier's morale took

on an added significance, and commanders found and

|

|

|

|

|

96

|

|

|

|

|

applied field expedient solutions to the problems. Recreation specialists from the United States established programs and recreation centers. "Care packages" from relatives and even strangers in the United States also helped. Nevertheless, as Col. Theodore W Reid of the 197th Infantry Brigade observed, keeping up the morale of the troops as they adapted to life in their primitive camps, operating bases, and firing positions in the desert was "darned tough." 45

The Army went to great lengths to grapple with this situation. Within a week of the beginning of the deployment, the XVIII Airborne Corps' forward command post in Saudi Arabia asked for mobile field post exchanges, and the dispatch of health and comfort items for deployed troops. Mail service started soon after the first deployments. At first a trickle, the flow quickly turned into a torrent. A microwave system went into Dhahran on 15 August for Armed Forces Radio and Television Service's broadcasters and technicians.46 Army field rations, including the infamous MREs, were supplemented by fruits, vegetables, and other products from the local economy. Roving hamburger stands, dubbed Wolfmobiles after the ARCENT food service officer who set them up, soon made their rounds.

97

cessions to the armies protecting them, especially within the military bases shared by U.S. and Saudi troops.

Particularly stressful to the Saudis was the role of female soldiers during the crisis. The Saudis found uniformed female soldiers, who lived in the same billets as male soldiers and frequently gave orders to men, disconcerting and almost incomprehensible. Concessions had to be made by all to protect host nation sensibilities while giving the soldiers enough latitude to accomplish their jobs.

Although women are forbidden to drive in Saudi Arabia, U.S. servicewomen could discreetly drive vehicles while on duty. Women who ventured off base, however, were sometimes required to wear black robes and veils, depending on the location of the base and the policies of the military district in which it was located. Generally, female troops were most restricted in urban areas, where their chances for contact with host nationals were greatest. If shopping off-base, women were required to have a male escort, and men and women were discouraged from engaging in public physical contact.47 The restrictions on dress and activities placed on women angered many male and female soldiers, as well as Congresswoman Patricia Schroeder of Colorado. "Can you imagine," she asked, "if we sent black soldiers to South Africa and asked them to go along with apartheid rules?" 48

Since alcoholic beverages were forbidden in Saudi Arabia, Army leadership enforced that prohibition. Soldiers turned to other methods of relaxation and entertainment, one of which was an increased use of tobacco. 49

Another potential problem centered on religion and the overt practice of religious beliefs. Saudi Arabia forbade the practice of any religion except Islam. Although the Army leadership realized that they could not ask soldiers to refrain from practicing their religion without precipitating a severe morale problem, they asked Army chaplains to be discreet in their activities, to the point of limiting Christmas celebrations. The chaplains tried to comply with these restraints, while many soldiers, isolated from their families and attempting to deal with the harsh desert environment, were in the process of discovering an increased interest in religion.50 Soldiers were asked to refrain from displaying religious symbols outside and indoors in areas frequented by the Saudis, and the Army chaplains were asked to remove their insignia when outside of U.S.-controlled areas.

Initially, the Saudis requested that such terms as "church services" and "chaplains" not be used and that the phrases "morale services" and "morale officers" be substituted.51 The ban on the terms "chaplain" and "church service" was lifted in January. As a general rule, those troops located near major urban areas experienced more restrictions than did those in areas of infrequent contact with host nationals.

Saudi customs officials closely inspected all incoming mail for the U.S. troops and strictly enforced the ban on mailing religious materials to private individuals. In December the Saudis lifted that prohibition. 52

98

Regardless of the prohibitions, chaplains in Southwest Asia conducted 17,394 Protestant services attended by 649,281 soldiers. In addition, 9,421 Catholic services attracted 425,772 attendees, and 390 Jewish services drew an attendance of 9,803. Almost 900 other types of religious services were held for 22,539 interested troops. A special Passover Seder was organized for 350 Jewish soldiers on board the Cunard Princess, a rest and recreation ship leased by the U.S. government. Working with the Saudi government, the chaplains also organized a small haj, or pilgrimage, to Mecca for U.S. Muslim soldiers.53

The 681 chaplains included 560 Protestants, 115 Catholics, and 6 Jews. Between them they distributed a variety of religious literature and objects, among them over 300,000 books and pamphlets, 150,000 audio tapes, and 700 menorahs. That material had been shipped to Southwest Asia by the Military Airlift Command and was not subject to the mailing prohibitions.54

The chaplains managed to finesse their way around the delicate issue of communion wine. Roman Catholics, Episcopalians, and some Lutherans required wine for the sacrament. As wine was forbidden in Saudi Arabia, the chaplains came up with the idea of a "chaplain consumable resupply kit," a box containing enough wine, grape juice, crosses, scriptures, communion wafers, and rosaries to last two weeks.55

By 18 August action officers had prepared a briefing discussing various strategies for supporting long-term force commitments in Southwest Asia for presentation to General Vuono. Among the matters requiring immediate attention of the chief of staff was the establishment of individual or unit rotations. A decision to conduct such rotation raised questions regarding whether units should deploy with their own equipment or should assume responsibility for equipment already in the theater and whether unit equipment would be modernized. The length of a tour of duty also remained a serious issue. 57

99

On 15 October Central Command presented its recommendations for a DESERT SHIELD rotation policy to the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Central Command suggested two different schemes. For combat and support units at operating bases and defensive positions in the desert, Central Command wanted a six- to eight-month cycle. For other units and personnel in less demanding environments the command recommended a twelve-month tour of duty. General Schwarzkopf and his planners were to maintain the existing combat capability indefinitely; to preserve the continuity of planning, operations, coalition relationships, and the understanding of the culture and environment; to establish and maintain equity among services; to provide tactical reliefs of units; and, when possible, to have incoming units take over major weapon systems and equipment. The assumptions that influenced the development of the policy and its objectives included the expectation that Central Command's force structure and mission would stay the same, that DESERT SHIELD would last at least one year, and that rotation would be phased so all units would not be replaced all at once. The plan also assumed that force modernization activities would not adversely affect rotations, that the first priority was preserving combat capability, and that if the mission changed the rotation policy too would be changed or terminated.58

The Army Staff and the Army's subordinate headquarters evaluated and adjusted the Army's deployment procedures to support that proposal and possible revisions. On 13 October Army Central Command, anticipating the announcement of a rotation policy, asked for the assignment of specially trained noncommissioned officers to help formulate the redeployment troop list.59 Three days later Forces Command hosted a two-day workshop to create a data base for the redeployment of units. The goal was to identify active and reserve units that could exchange with units deployed to Saudi Arabia. Forces Command wanted to develop and distribute the data base to its subordinate headquarters by 1 November, but reminded its subordinates that "the decision on rotation and timing are currently unknown." Indeed, final choices on rotation awaited more basic decisions. If coalition forces were about to become involved in ejecting the Iraqis from Kuwait, reinforcement, not rotation, would become the focus of planning. 60

By the time that these discussions took place, the SHIELD had expanded dramatically. Three complete combat divisions of the XVIII Airborne Corps had reached Saudi Arabia from the United States. So had advance elements of the 1st Cavalry Division, the entire 3d Armored Cavalry, and the first of a steady flow of reserve-component units. Six Patriot battalions and the 12th Aviation Brigade had come from Germany. The soldiers in Operation DESERT SHIELD were acclimating themselves to the physical and cultural environment, and, as their numbers grew, their vulnerability to an Iraqi attack was diminishing.

Notes

1 Equipment numbers from Chart, DESERT SHIELD Combat System Deployment, filed in Army Operations Daybook no. 3, 11-17 Sep 90.

2 Lewis Sorley, "Creighton Abrams and Active-Reserve Integration in Wartime," Parameters 21:2 (Summer 1991): 43-50.

3 New York Times, 29 Sep 90, p. 4.

4 Memo, Secretary of Defense Richard Cheney for Secretaries of the Military Departments and Chairman of the joint Chiefs of Staff, 23 Aug 90; Vuono interview, 3 Aug 92.

5 Ltr, Congressman G. V. Montgomery to Secretary of Defense Richard Cheney, 24 Aug 90; Ltr, Montgomery to Cheney, 28 Aug 90.

6 Ltr, Congressmen Aspin, Montgomery, and McCurdy and Congresswoman Byron, to Secretary of Defense Cheney, 6 Sep 90.

7 Ltr, Secretary of Defense Cheney to Congressman Aspin, 18 Sep 90.

8 House Armed Services Committee, News Release, Anti-Reserve Bias Behind Combat Unit Absence, 16 Oct 90.

9 Msg, COMUSARCENT, 8 Oct 90, sub: ARCENT MAIN G3 Sitrep.

10 Memo for Secretary of the Army/Chief of Staff of the Army, 2 Sep 90, sub: Army Operations Update Operation DESERT SHIELD Information Memorandum Number 26.

11 MS, John R. Brinkerhoff, Loading the Ships for DESERT STORM: The Total Army in Action in the Military Traffic Management Command [Washington, D.C.: Office, Chief of the Army Reserve, 1991].

12 Information Paper, Army Operations Center, 11 Aug 90, sub: Current Operations Situation, 11 Aug 90.

13 Memo, DCSOPS for Secretary of the Army/Chief of Staff of the Army, 18 Aug 90, sub: Army Operations Update Operation DESERT SHIELD-Information Memorandum Number 11.

14 Ibid.; Memo, DCSOPS for Secretary of the Army/Chief of Staff of the Army, 27 Aug 90, sub: Army Operations Update Operation DESERT SHIELD-Information Memorandum Number 20.

15 Msg, Cdr, XVIII Airborne Corps, to CINCFOR, 22 Aug 90, sub: XVIII Abn Corps Sitrep No. 15; Msg, COMUSARCENT to USCINCCENT, 20 Aug 90, sub: ARCENT AFRDDTO Sitrep; Msg, CINCFOR to CJCS, 16 Sep 90, sub: FORSCOM FCJ3-CAT Sitrep No. 40, Memo for Secretary of the Army/Chief of Staff of the Army, 2 5 Sep 90, sub: Army Operations Update Operation DESERT SHIELD-Information Memorandum Number 49; TRANSCOM Ship Movement Status Rpts, Aug-Sep 90.

16 Msg COMUSARCENT, 8 Oct 90, sub: ARCENT MAIN G3 Sitrep.

17 Msg, FORSCOM Sitrep, 13 Sep 90.

18 Msg, COMUSARCENT to AIG 11743, 17 Oct 90, sub: ARCENT MAIN G3 Sitrep.

19 Msg, CINCFOR to CJCS, 8 Aug 90, sub: FORSCOM Situation Report.

20 Joint Staff (JS) Action Processing Form, Crisis Action Team (CAT) 0067, 11 Aug 90.

21 JS Form 136L, 17 Aug 90, initialed "CP"

22 CAT Tasking Form 8302, 17 Aug 90.

23 CAT Tasking Form 8241, 16 Aug 90.

24 Ltr, President Bush to Speaker of the House of Representatives and President Pro Tempore of the Senate, 22 Aug 90.

25 Memo, Secretary of Defense Richard Cheney for Secretaries of the Military Departments and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, 23 Aug 90.

26 See, for example, Martin Binkin and William W. Kaufmann, U.S. Army Guard and Reserve: Rhetoric, Realities, and Risks (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, 1989).

27 Ltr, Maj Gen Wagner to Gen Vuono, 25 Aug 86, quoted in Binkin and Kaufmann, U.S. Army Guard and Reserve, p. 96.

28 Ltr, Congressman John P. Murtha to Secretary of Defense Richard B. Cheney, 11 Sep 90.

29 Memo, Gen Colin Powell for the Secretary of Defense, 19 Oct 90 .

30 Information Paper, DASG-PTM, 28 Dec 90, sub: Deployment/Activation of AMEDD Personnel for Operation DESERT SHIELD.

31 National Guard Bureau, Operation DESERT STORM Briefing Book 4, tab 28.

32 Draft MS, National Guard Bureau, ARNG After Action Report, Part 11: Lessons Learned [3 June 1991], p. 39, citing JULLS No. 43028-76914 (00014).

33 Andrulis Research Corporation, Preliminary Report: Phase 1-Operation Desert Shield (Bethesda, Md.: Andrulis Research Corporation, 1990), p. 13.

34 Ibid., p. 13.

35 Soldiers 45:11 (November 1990): 10.

36 Msg Cdr, 24th Infantry Division, to Cdr, FORSCOM (Personal for Maj Gen Pagonis, J4, FORSCOM), 8 Aug 90, sub: Key Ammunition Short Falls-24th Infantry Division (Mech).

37 Soldiers 45:11 (November 1990): 10.

38 Army Times, 10 Jun 91, p. 16.

39 Msg, CINCFOR to CJCS, 16 Aug 90, sub: Sitrep, 15 Aug 90.

40 Msg, Cdr, TRANSCEN, to Cdr, FORSCOM, 19 Aug 90, sub: Installation Sitrep Number 7.

41 Memo, Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations and Plans for Secretary of the Army and the Chief of Staff, 19 Aug 90, sub: Army Operations Update Operation DESERT SHIELD-Information Memorandum Number 12.

42 Msg, Cdr, XVIII Airborne Corps, to CINCFOR, 22 Aug 90, sub: Sitrep No. 15, 22 Aug 90.

43 Vuono interview, 3 Aug 92.

44 Soldiers 45: 11 (November 1990): 13-14.

45 Soldiers 45: 10 (October 1990): 36.

46 Msg Cdr, XVIII Airborne Corps, to CINCFOR, 14 Aug 90, sub: Sitrep No. 7, 14 Aug 90.

47 Molly Moore, "For Female Soldiers, Different Rules," Washington Post, 23 Aug 90, p. D 1; James LeMoyne, "Army Women and the Saudis: The Encounter Shocks Both," New York Times, 25 Sep 90, p. 1.

48 "Our Women in the Desert," Newsweek (10 September 1990): 22.

49 Information Paper, Stanley Prepscius, DAPE-HR-PR, 19 Mar 9 1.

50 Interv, Henry O. Malone and Susan Canedy with Chaplain (Col) Gaylord E. Hader, 14 Jun 91.

51 Ibid.

52 Information Paper, Chaplain (Lt Col) Jack Anderson, DAPE-HR-S, Religious Support For Deployed Personnel During Operation DESERT SHIELD/STORM (All Services), n.d.

53 Ibid.; Hatter interview.

54 Information Paper, Chaplain Anderson, Religious Support For Deployed Personnel; Geraldine Baum, "Baptism of Fire," Los Angeles Times, 2 Jan 91.

55 Hatter interview.

56 Discussion Paper, Strategic Planning Team, Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations, Department of the Army, 29 Aug 90, sub: DESERT SHIELD-Why We Are There: A Discussion of Strategy and Policy.

57 Briefing Slides, Sustaining the SWA Force, in the Army Operations Center Daybook no, 3, 11-17 Sep 90.

58 Msg, USCINCCENT to joint Chiefs of Staff UCS), 15 Oct 90, sub: DESERT SHIELD Theater Rotation Policy.

59 Msg, COMUSARCENT, 13 Oct 90, sub: USARCENT MAIN G3 Sitrep.

60 Msg, CINCFOR to Cdr, First U.S. Army, 20 Oct 90, sub: Operation DESERT SHIELD Rotational Units; Vuono interview, 3 Aug 92.

page updated 7 June 2001

Return to the Table of Contents