This interview was conducted 5 June 1991 at the Headquarters of the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault), Fort Campbell, Kentucky. The interviewers were MAJ Robert K. Wright, Jr. (XVIII Airborne Corps Historian), Mr. Rex Boggs (Curator, Don Pratt Museum), and 1LT Cliff Lippard (101st Airborne Division Historian).

Operations DESERT SHIELD and DESERT STORM vindicated the Army’s attention to training and readiness. This extensive interview conducted by Army historians provides one division commander’s view of how readiness helped achieve victory in the war against Iraq. It also contains insights into how a division commander dealt with the fast pace of the ground war. At the time of this interview, MG J.H. Binford Peay was nearing completion of his tour as commander of the 101st Airborne Division. Soon afterward, he was promoted to lieutenant general and assigned to the Pentagon as the Department of the Army’s Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations and Plans. In March 1993, he earned his fourth star and became the Army’s Vice Chief of Staff. In August 1994, he assumed command of the United States Central Command.

Throughout the interview, General Peay expresses confidence in the ability of his troops to overcome difficult challenges. He sees training and standards as two of the keys to the U.S. Army’s success against Iraq, helping create a force of ready professionals. General Peay discusses the 101st Airborne Division’s deployment to Saudi Arabia; its plans for a defense against an Iraqi attack; and finally the division’s role in the coalition offensive.

This transcript is offered as a most worthwhile addition to the growing

body of knowledge on the Persian Gulf war. We hope that it will generate

additional work by those interested in warfare in this century.

United States Army

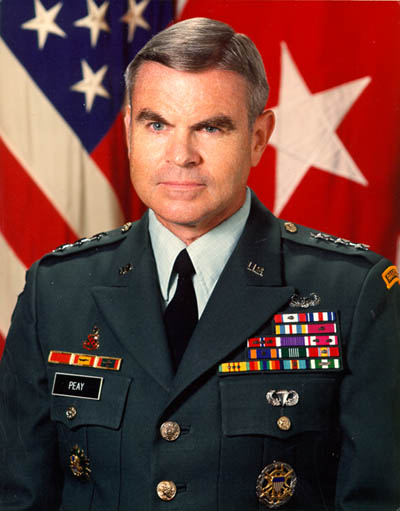

General J.H. Binford Peay III was born in 1940. Upon graduation from the Virginia Military Institute in 1962, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant and awarded a Bachelor of Science degree in Civil Engineering. He later earned a Master of Arts from George Washington University. His military education includes completion of the Field Artillery Officer Basic and Advanced Courses, the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, and the U.S. Army War College.

General Peay’s initial troop assignments were in Germany and Fort Carson, Colorado. From December 1964 to September 1966, he served as Aide-de-Camp to the Commanding General, 5th Infantry Division. He went on to serve in other assignments including two tours in the Republic of Vietnam. In his first tour from May 1967 to July 1968, he commanded both Headquarters Company, I Field Force Vietnam, and a firing battery (Battery B, 4th Battalion, 42d Artillery) with the 4th Infantry Division in the central highlands. During his second tour from August 1971 to June 1972, he served as the assistant operations officer for the 3d Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division, and as operations officer for the same division’s 1st Battalion, 21st Artillery.

After serving with the Army Military Personnel Center in Washington, DC, as a Field Artillery branch assignments officer, Peay was sent to Hawaii in 1975 to command the 2d Battalion, 11th Field Artillery, 25th Infantry Division. Following completion of the Army War College, he returned to Washington, DC, as Senior Aide to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and later as Chief of the Army Initiatives Group in the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Operation and Plans. He then moved to Fort Lewis, Washington, to serve as the I Corps’ Assistant Chief of Staff, G-3/Director of Plans and Training, and later became Commander, 9th Infantry Division Artillery. In 1985, he returned to Washington, DC, as Executive to the Chief of Staff, United States Army. He first became a Screaming Eagle in July 1987, when he became the Assistant Division Commander (Operations), 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) at Fort Campbell, Kentucky. Beginning in July 1988, he served a one year assignment as Deputy Commandant, Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

On 3 August 1989, General Peay returned to Fort Campbell to assume command of the 101st Airborne Division and led the division through Operations DESERT SHIELD and DESERT STORM in the Persian Gulf. Promoted to the rank of Lieutenant General, he was the Army’s Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations and Plans, and Senior Army Member, United States Military Committee from June 1991 until March 1993. He was promoted to General on 26 March 1993 and appointed as the Army’s twenty-fourth Vice Chief of Staff. He assumed his last active duty position, as Commander in Chief, United States Central Command, at MacDill Air Force Base, Florida, on 5 August 1994.

General Peay has received awards and decorations including the Army Distinguished Service Medal with two oak leaf clusters, the Silver Star, the Defense Superior Service Medal, the Legion of Merit with oak leaf cluster, the Bronze Star Medal with three oak leaf clusters, and the Purple Heart. He has also received the Meritorious Service Medal with two oak leaf clusters, several Air Medals, and the Army Commendation Medal. Additionally, he wears the Parachutist Badge, Ranger Tab, the Air Assault Badge, the Secretary of Defense Identification Badge, Joint Chiefs of Staff Identification Badge, and the Army General Staff Identification Badge.

Under Army Regulation 870-5, Military History: Responsibilities, Policies, and Procedures, military history detachments and historical offices send their interviews to the U.S. Army Center of Military History’s Oral History Activity where the tapes or transcripts can be used for the preparation of official histories. This interview is one of over 800 oral histories in the Center’s DESERT SHIELD/DESERT STORM Interview Tape (DSIT) collection and has the catalog number DSIT-AE-101.

As the XVIII Airborne Corps historian in Southwest Asia, MAJ Robert K. Wright, Jr., accompanied the 101st Airborne Division into Iraq and was the lead interviewer when General Peay participated in this oral history shortly after the division returned from Southwest Asia in 1991. After the Center transcribed the interview, Dr. Wright (first in his civilian job as corps’ historian and later after his transfer to the Center) completed the initial editing of the transcript. Stephen E. Everett and Dr. Richard A. Hunt of the Center’s Oral History Activity made further editorial refinements. The editors tried to maintain the interviewee’s wording and intent, but deleted false starts and added words and explanations when necessary for clarity.

General Peay and his staff assistant, LTC Randy Kolton, reviewed the edited transcript and clarified a number of points. Mr. Everett prepared the historical essay which provides background information for the 101st Airborne Division and air assault doctrine, as well as a brief summary of the division’s activities during DESERT SHIELD/DESERT STORM. Dr. Jeffrey J. Clarke, the Center’s Chief Historian, and Drs. Wright and Hunt offered helpful suggestions to improve the narrative and make it more appealing to a wider audience. CPT Gordon R. Quick, the Center’s military history intern and a 101st Division veteran, also added his insight, as did the Oral History Activity’s Dwight D. Oland. Steve Hardyman and John Birmingham of the Center’s Production Division assisted with the maps and the final publication format.

Questions and comments concerning this transcript should be sent to the Oral History Activity, U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1099 14th Street, N.W., Washington, DC 20005-3402.

The 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) has earned an honored place in American military history. Stationed at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, the division is known throughout the Army as "The Screaming Eagles" because of the unit’s distinctive shoulder sleeve insignia. The division fought at Normandy and Bastogne during World War II, and at Dak To and the A Shau Valley in the Vietnam war. To that list of battlefields can now be added FOBs (Forward Operating Bases) COBRA and VIPER, the Euphrates Valley, and other places from Operation DESERT STORM.

Organized as an air assault division, the 101st Airborne Division is normally equipped with over 200 helicopters, far more than other Army divisions. These helicopters give the 101st Division exceptional aerial mobility, serve as weapons platforms, and provide transport for soldiers and supplies. Air assault, however, is more than moving troops and equipment by air; it is a way of thinking about warfare. As set forth in Army Field Manual 90-4, Air Assault Operations, highly mobile combined arms teams undertake these missions to strike an enemy where he is most vulnerable. Routinely using the cover of darkness and able to cover extended distances, air assault infantry can catch an opponent unprepared by flying over enemy lines and terrain obstacles and landing on top of, or behind, enemy defensive positions. The 101st demonstrated this capability during DESERT STORM when its helicopters quickly transported troops and their equipment over distances far beyond the logistical capabilities of many nations’ armies. Air assault commanders can also "task organize," or tailor, their numerous organic aviation units for rapid redeployment to a variety of tactical situations. As commander of the 101st, MG J.H. Binford Peay III exploited this advantage, using the inherently flexible organization of the air assault division.

The division’s successful air assaults in Southwest Asia drew on years of combat experience and doctrinal refinements. In Vietnam, the 101st had employed attached helicopters to locate the enemy and transport troops into combat. Reorganized in 1968 as an "airmobile" division, the 101st relied heavily on the mobility and flexibility provided by organic helicopter units. After the Vietnam war, the term "air assault" replaced "airmobile," and soldiers in

[2]

the newly designated air assault division refined their skills in areas such as rappelling from helicopters, unit aerial assaults, and sling-loading of equipment. In the 1970s and 1980s, the air assault division earned a place in the Army’s new operational doctrine, AirLand Battle, which was used in the war against Iraq.

In its simplest terms, AirLand Battle was based on four tenets: initiative, depth, agility, and synchronization.1 First, initiative encouraged soldiers at all levels to seize and exploit opportunities to gain advantages over opponents. Second, commanders were urged to use the entire depth of the battlefield and strike at rear echelon targets that supported frontline troops. Third, agility required commanders to react to enemy strengths and quickly strike at the enemy where he was vulnerable. Fourth, synchronization called for the commander to maximize available combined arms firepower on critical targets to achieve the greatest effect. These complementary tenets were the foundation for campaign planning in DESERT STORM.

The air assault division is well designed for AirLand Battle. It contains nine infantry battalions organized into three brigades. Each infantry battalion has an authorized strength of about forty officers and 640 enlisted personnel, organized into a headquarters company, three rifle companies, and an anti-armor company to provide extra firepower against enemy tanks. An aviation brigade with eight battalions provides the division with organic reconnaissance, attack, aeromedical, assault and logistical lift capabilities. Divisional combat support and combat service support elements round out the organization, and additional units can be attached to the division as required (see Chart 1).2

Air assault operations enable the division commander to seize and maintain

the operational and tactical initiative. With local air superiority, the

air assault division commander can move his units rapidly, bypassing enemy

strongpoints, concentrating forces, and exploiting opportunities. During

operations in Southwest Asia, the 101st Airborne Division skillfully employed

air assault tactics and validated the basic tenets of the AirLand Battle

doctrine.

Operations

DESERT SHIELD and DESERT STORM

On 2 August 1990 with little warning, Iraq, under the dictatorship of Saddam Hussein, invaded Kuwait and totally occupied the country in less than forty-eight hours, instigating a serious international crisis. Hussein commanded the world’s fourth largest field army, which included large numbers of modern Soviet-designed tanks and veterans seasoned by a long and bloody war with Iran. Saudi Arabia, Kuwait’s neighbor to the south,

[4]

fearing that its oil fields would be the Iraqi Army’s next objective, agreed on 6 August to accept U.S. military assistance.

Operation DESERT SHIELD began with the U.S. order to deploy air, ground, and sea forces to the region, among them the 101st Airborne Division, to help defend the Saudis against an anticipated Iraqi attack. On 8 August, thirty-six hours after receiving their alert notice, lead elements of the XVIII Airborne Corps’ 82d Airborne Division were enroute from Fort Bragg, North Carolina to Saudi Arabia. Seven days later, one 82d Airborne brigade drew a symbolic "line in the sand," warning Hussein not to cross the border. The 82d Airborne Division’s paratroopers were soon joined by growing numbers of soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines who came under GEN H. Norman Schwarzkopf, Commander in Chief of the U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM), the joint command responsible for U.S. operations in Southwest Asia. Other nations joined a coalition against Iraq. Eventually thirty-seven countries, among them Great Britain, France, Italy, Egypt, Syria, and other Arab nations in the region, provided troops or materiel.

CENTCOM’s initial objective was to bring enough ground, air, and sea power into Saudi Arabia to demonstrate America’s commitment to defend its ally and deter an Iraqi attack. In the early days of DESERT SHIELD, planners realized that available forces could not defend all of Saudi Arabia, but hoped that American planes could destroy enough Iraqi tanks to slow an invasion and allow American and Saudi ground forces to defend the major gulf ports until reinforcements arrived. The buildup of military forces necessitated the creation of a logistical base, forcing CENTCOM to balance the deployment of combat forces with the support troops and their supplies and equipment. The availability of air and sea transport, and the enormous distance between the United States and Saudi Arabia, also complicated the buildup and added to CENTCOM’s concerns. Although the 101st Airborne Division was designed to be rapidly deployable, logistics requirements and the demand for heavy "armored" forces governed the deployment of the division and other units to the desert.

Another XVIII Airborne Corps unit, the 24th Infantry Division (Mechanized)

actually began its deployment to the Gulf before the 101st Airborne Division.

The 24th Division was directed on 6 August to start moving its M1 Abrams

tanks, M2 Bradley Fighting Vehicles, and other equipment from Fort Stewart,

Georgia to the port of Savannah, where they would be loaded onto ships

for the long voyage to Saudi Arabia. By the first half of September personnel

and equipment for the 24th Division’s two brigades had arrived in theater.3

Meanwhile, on 10 August, the Army issued deployment orders for the 101st.

At that time, many of the division’s units were far from their home station

at Fort Campbell. Some units were scattered across the country supporting

Reserve Component summer training or conducting training exercises at West

Point, New York; others were abroad in Honduras and Panama, or preparing

to deploy to the Sinai as part of the Multinational Force and Observer

Organization. All units had to return to Kentucky as quickly as possible

to prepare for their mission in Saudi Arabia.

[5]

The division’s advance party arrived in Saudi Arabia on 15 August and began laying the groundwork for the rest of the 101st. CENTCOM placed a high priority on receiving anti-armor equipment, and the 101st’s attack helicopters, the division’s best anti-tank weapons, were sent first. The first planes carrying personnel and equipment from the 101st’s Aviation Brigade and the 2d Brigade’s "ready" battalion left Fort Campbell on 17 August. Over the next thirteen days, the 101st Division sent by air (in fifty-six Air Force C-141s and forty-nine C-5Bs) 117 helicopters, 487 vehicles, 123 equipment pallets, and 2,742 troops into the theater. In addition to its own units, the division also had to coordinate the rapid air deployment of the 2d Battalion, 229th Aviation (equipped with AH-64 Apache attack helicopters) from Fort Rucker, Alabama and the Target Acquisition Platoon of Troop A, 1st Squadron, 9th Cavalry (equipped with OH-58D Kiowa reconnaissance helicopters) from Fort Lewis, Washington. These two units would remain attached to the 101st throughout the operation, contributing to its overall combat power. The rest of the 2d Brigade, along with other elements, arrived by 10 September.

The remainder of the division’s equipment moved by convoy and rail to Jacksonville, Florida and was loaded aboard ships for the month-long voyage to Saudi Arabia. The first of the ten ships that carried the division’s equipment sailed on 19 August and the last left port on 10 September. The sailing time gave soldiers from the 3d and 1st Brigades a few extra days of preparation at Fort Campbell before deploying to the theater in commercial aircraft. Throughout September, division elements flew to the Arabian Gulf (Persian Gulf) where they married up with their equipment. All elements of the 101st were in Saudi Arabia by 6 October.

Division engineers constructed the division’s initial staging facility and base camp, Camp EAGLE II, near King Fahd International Airport (KFIA), just inland from the Arabian Gulf and northwest of Ad Damman. During the following weeks, the division carried out its defensive mission as a covering force in Area of Operations (AO) NORMANDY, a large 1,800 square mile (4,600 square kilometer) region lying about 130 miles northwest of the division base camp and 85 miles south of Kuwait. Within NORMANDY, the division had two forward operating bases (FOBs), BASTOGNE in the area’s eastern section near An Nu’ayriyah and OASIS located at an abandoned unnamed village in the western section. In the harsh desert environment, the 101st’s helicopters were instrumental in moving forces and supplies, and providing fires over this vast area.

The XVIII Airborne Corps planned to use the 101st Division to slow the considerable armor formations that would support any Iraqi thrust into Saudi Arabia. Only a limited number of roads would be available to invading Iraqi tanks, and the 101st’s ground and air elements could cover these routes. Each of the division’s organic and attached attack helicopter battalions had eighteen AH-64 Apaches or twenty-one AH-1 Cobras providing the 101st with a powerful punch and exceptional anti-tank capabilities. Flying low to the ground and using available desert terrain for cover, helicopters could strike hostile armor or their vulnerable logistical support deep behind forward lines. The Apache’s advanced sensors allowed the helicopters to fly at night and in inclement weather, thus creating a serious threat to the Iraqis. The division had at its disposal a variety of anti-tank systems, but perhaps the most effective were the sixteen Hellfire missiles carried by each Apache attack helicopter. In addition, every Cobra helicopter carried eight Tube-launched, Optically-tracked, Wire-guided (TOW) missiles. The lethality of these weapons sys-

[7]

tems explained why American commanders wanted the 101st’s attack helicopter battalions deployed to Saudi Arabia as soon as possible.

Adding to the division’s arsenal were another 180 TOW launchers mounted on High Mobility, Multi-purpose Wheeled Vehicles (known as HMMWVs, HUMVEEs, or HUMMERs). There were twenty TOW equipped HMMWVs located in each of the 101st Division’s nine anti-armor companies and, unlike Iraqi tanks, they were not bound to the road by the soft sand. HMMWVs could rapidly outmaneuver enemy tanks over desert terrain, and their TOW missiles could also outdistance the main guns of the Iraqi armor by up to 2,000 yards. In preparing to defend Saudi Arabia, the 101st formed mobile anti-armor teams with these assets and placed them forward to meet an Iraqi attack. Using the firepower of these weapons systems, complemented by aerial mobility and fire from the division artillery, the 101st would attempt to slow an enemy onslaught and then hand off the covering force battle to the 24th Infantry Division (Mechanized). Located behind the 101st, the 24th would fight the main battle against any invaders.

The 101st Division’s anti-tank capabilities expanded with the attachment of the 12th Aviation Brigade, which deployed from Europe to Saudi Arabia in late September and early October. The brigade consisted of two attack helicopter battalions, equipped with Apaches, and supporting lift units. Another unit, the 3d Armored Cavalry deployed from Fort Bliss, Texas in the second half of September. During Operation DESERT SHIELD the regiment came under the operational control of the 101st Airborne Division and played a key role in the division’s covering force plans. Also attached to the 101st during DESERT SHIELD, the 75th and 212th Field Artillery Brigades provided indirect fire support with their Multiple Launch Rocket Systems, and 155mm and 8-inch self-propelled howitzers. The 101st and its attached units constantly rehearsed their defensive plans and were prepared for an Iraqi attack.

With the October arrival of the 1st Cavalry Division (organized as an armored division), coalition leaders felt confident that they had more than sufficient strength to defend the important coastal region of Saudi Arabia. By 5 November, just three months after the initial deployment, XVIII Airborne Corps’ strength in Saudi Arabia included over 760 tanks, almost 1500 armored fighting vehicles, more than 500 artillery pieces, nearly 230 attack helicopters, and 107,300 soldiers. The coalition’s next step was to begin preparing its forces for a possible offensive to restore Kuwait’s independence if Iraq refused to remove its forces. In November, to provide the extra military forces needed to recapture Kuwait, President George Bush announced the deployment of additional American divisions from Europe and the United States to Saudi Arabia. These deployments clearly signaled the intention of the United States and its coalition partners to employ force to retake Kuwait, but Saddam Hussein refused to withdraw his occupying army.

The new armor and mechanized divisions provided the decisive ground combat power for coalition forces to go on the offensive and liberate Kuwait. The 1st and 3d Armored Divisions, the 1st Infantry Division (Mechanized), and the 2d Armored Cavalry arrived in Saudi Arabia over the next few months and came under the VII Corps. These divisions, together with the United Kingdom’s 1st Armoured Division, formed the spearhead that would cross into Iraq and confront the tanks of Hussein’s "elite" Republican Guard divisions, which were waiting in reserve far behind the Iraqi border defenses. Non-Republican Guard Iraqi divisions were dug in along the

[8]

Saudi border. These inferior divisions were concentrated from about forty miles west of the Wadi Al-Batin, one of the few natural terrain features along the Iraq-Kuwait border, along the entire distance of the Saudi border extending to the gulf. Behind these frontline troops Iraq had positioned a number of other divisions, including higher caliber armored and mechanized units to act as a mobile reserve, and the Republican Guard divisions, to act as a counterattack force. Numerous artillery groupments supplemented all these units.

GEN Schwarzkopf’s campaign to defeat Iraq and liberate Kuwait, Operation DESERT STORM, was scheduled to begin sometime after January 15, 1991, the United Nations’ deadline for the withdrawal of Iraqi forces from Kuwait. DESERT STORM would open with several weeks of an aggressive bombing campaign aimed at weakening Iraq’s infrastructure, command and control centers, and frontline positions. In the next phase, the ground offensive, Schwarzkopf planned to have Marine and Arab units tie down Iraqi forces along the Kuwaiti-Saudi border, while the tank-heavy VII Corps divisions would breach Iraqi defenses to the west of Wadi Al-Batin and engage the Iraqi divisions from the flank and rear. VII Corps’ goal was to defeat the Republican Guards and prevent them from counterattacking the Marine and Arab forces that would advance towards Kuwait City.

[9]

The mission of the 101st Division and other XVIII Airborne Corps units was to cover the left flank of the VII Corps and coalition forces, and strike deep inside Iraq to prevent retreating Iraqi troops from escaping across the Euphrates River. The 101st would also be in position to threaten the Iraqi capital of Baghdad. Two brigades of the 1st Cavalry Division, which had been removed from XVIII Airborne Corps to act as an army reserve in December 1990, would defend against a possible Iraqi counterattack at the Wadi Al-Batin and create the impression that the main coalition attack would come along the wadi.4 The 6th French Light Armored Division replaced the 1st Cavalry Division within XVIII Airborne Corps.

The plan also required both VII and XVIII Corps to reposition their forces to the west prior to the ground offensive. The execution of this movement was a significant accomplishment in itself. Most of the move took place after the war started and it escaped notice by Iraqi intel-

[10]

ligence thanks to allied deception operations and air supremacy. First, VII Corps maneuvered into line west of both Wadi Al-Batin and XVIII Airborne Corps, which was still protecting the gulf ports. Then, XVIII Airborne Corps, including the 101st, moved to the west leapfrogging VII Corps and occupying positions near the Iraqi border. Thus XVIII Airborne Corps anchored the far west of the coalition line, while U.S. Marine and Arab Coalition forces guarded the eastern portion. The 101st took eleven days to relocate northwest to a site near the Iraqi border, Tactical Assembly Area (TAA) CAMPBELL, about forty miles southeast of the Saudi town of Rafha. To reach CAMPBELL, the division moved over 600 miles by road and 300 by helicopter or Air Force C-130 transport planes.

XVIII Airborne Corps faced fewer and less concentrated Iraqi forces than did VII Corps, but its logistical challenge was far greater. The XVIII’s assembly areas were far from the coalition’s support bases along the coast and its troops had to cross enormous expanses of Iraq’s desert terrain to reach their objectives. Maintaining access to critical supplies such as fuel (consumption rates for the 101st’s helicopters paralleled fuel requirements for an armored division) was key to a successful operation. Logistical support for the corps entailed the establishment of forward logistics bases and running ground supply convoys along a series of lengthy main supply

[11]

routes (MSRs). The Trans-Arabia Pipeline (TAPLINE) Road, also known as MSR DODGE, was the main route that connected XVIII Airborne Corps to other coalition forces and Saudi Arabia’s coast. The corps’ main logistical base, CHARLIE, was located astride the TAPLINE Road about fifty miles southeast of Rafha. Corps engineers improved the old dirt trading routes that led about twenty miles north from the TAPLINE Road to the Iraqi border. From west to east these roads were MSRs TEXAS, NEWMARKET, and GEORGIA, and they would serve as the axes for the corps’ ground attack.

As the start of the ground war drew near, XVIII Airborne Corps completed preparations for its attack. On the corps’ far left, the 6th French Light Armored Division, supported by the 82d Airborne Division, would seize key blocking positions around As Salman, an Iraqi town about a hundred miles north of Rafha along MSR TEXAS. In the middle of the corps, the 101st Division would initiate a series of air assaults in order to occupy strategic positions in the Euphrates Valley and cut road connections between Baghdad and Kuwait City. Essential to this operation was the seizure and establishment of a forward operating base, called FOB COBRA, about eighty miles inside Iraq to serve as a staging area for additional assaults. Ground convoys carrying supplies and supporting troops would follow up the initial air assaults and advance north along MSR NEWMARKET to connect TAPLINE ROAD and COBRA. Corps logisticians also planned to establish MSR VIRGINIA as an east-west route connecting As Salman with points east. The 24th Infantry Division and the 3d Armored Cavalry would use MSR GEORGIA on the corps’ right flank and support the advances of VII Corps.

During the air war the 101st Division continued preparing for the ground offensive, rehearsing air assaults and the establishment of forward operating bases. Some division elements had already been in combat. Apache helicopters from the 101st had helped open the air war early on 17 January 1991, flying inside Iraq to destroy two early warning radar sites before they could alert Baghdad of the impending air attacks. In the weeks that followed, MG Peay kept the division ready for action. In the days preceding the main ground attack on 24 February (G-Day), the division launched a series of reconnaissance raids into Iraq. These forays captured enemy soldiers and the experience also honed the soldiers’ combat edge for the air assaults that were soon to follow.

On G-Day, the 101st Division’s 1st Brigade, reinforced by a battalion from the 2d Brigade, air assaulted about ninety-five miles north from TAA CAMPBELL into the patch of desert that would become FOB COBRA. Apaches, artillery, and Air Force A-10s (ground support aircraft) forced a battalion of dug-in Iraqi defenders from their bunkers, quickly allowing troops to secure COBRA. CH-47D Chinooks (a medium transport helicopter) and ground convoys operating along MSR NEWMARKET rushed fuel, ammunition, and other supplies into COBRA. By the afternoon of 24 February, combat elements of the 1st Brigade and the Aviation Brigade had established massive refueling and rearming points at the FOB for the division’s helicopters. Meanwhile, the 3d Brigade prepared to pass through COBRA and land in the Euphrates valley.

Deteriorating weather threatened to cancel or delay some of the division’s northward operations, but instead of waiting MG Peay and his 3d Brigade commander decided to move early. In a series of assaults that began in the late morning on G+1, 25 February, the 3d

[12]

[13]

Brigade left TAA CAMPBELL and flew a total of 155 miles north, taking and holding positions in the Euphrates River valley in a region termed AO EAGLE. This second assault effectively cut Highway 8, the main road between Baghdad and Basra, that supported the Iraqi Army in Kuwait. With the occupation of AO Eagle, the 101st had successfully advanced another eighty-five miles northeast of COBRA and positioned forces about 145 miles southeast of Baghdad. The division spent the next day (26 February, G+2) reinforcing AO EAGLE and preparing for its eastward attack.

On the fourth day of the ground war, 27 February (G+3), two infantry

battalions from the division’s 2d Brigade and a third from the 1st Brigade

boarded helicopters that carried them almost another ninety-five miles

east to establish FOB VIPER. At this time, one route over the Euphrates

River and nearby swamps had been left open to channel the withdrawal of

the retreating Iraqis. Four Apache battalions (two from the attached 12th

Aviation Brigade and two from the 101st), operating from VIPER on the afternoon

of G+3, launched coordinated attacks over the Euphrates against enemy units

moving north from Basra into Engagement Area (EA) THOMAS. In what some

called the "Battle of the Causeway," the Apaches ravaged the Iraqi forces

seeking the "safety" of the north bank of the river. During the evening

hours of G+3, the division prepared to launch its 1st Brigade from FOB

COBRA through VIPER into EA THOMAS. This maneuver would have firmly closed

the door on the escaping Iraqi Army by blocking the north-south Basra road,

but early on the morning of G+4, 28 February, the 101st Division received

word of the cease-fire.

[14]

The coalition had won an unexpectedly rapid victory with far fewer casualties than expected. U.S. Army units moved across the desert in rapid advances that flattened all Iraqi resistance. Kuwait was liberated and Iraqi forces were in full retreat. With the end of hostilities, the 101st secured and manned defensive positions and collected enemy equipment for destruction. The division also treated sick or injured Iraqi civilians and military personnel. Although the 101st suffered no combat deaths during the four day ground war, the attached 2d Battalion, 229th Aviation was less fortunate. Five soldiers were killed when hostile fire brought down their Blackhawk helicopter which was on a combat search and rescue mission to recover an Air Force pilot. Iraqi forces captured three members of the Blackhawk crew and released them soon after the war.

The Screaming Eagles returned to the United States in stages. In the first phase, about nine hundred men from the 2d Brigade left FOB Viper in Iraq for TAA Campbell on 6 March. Boarding commercial planes at Dhahran on 8 March, the 2d Brigade soldiers flew back to Fort Campbell via Germany and New York. Amid an Iraqi rebellion against Hussein and the turmoil of thousands of Iraqi and Kuwaiti refugees, the rest of the 101st stood ready in case of trouble. Gradually, division elements pulled back to Saudi Arabia, leaving the 3d Brigade and elements of the division support command on occupation duty in AO EAGLE until the 2d Armored Cavalry and the 11th Aviation Brigade relieved the brigade around 24 March.

When the last 101st convoy left Iraq on 25 March, the rest of the division was busy preparing for redeployment from Saudi Arabia to Fort Campbell. After months in the desert the troops were eager to get home, but equipment had to be cleaned, accounted for, and prepared for shipment to the United States. Most division soldiers flew home between 3 and 15 April. MG Peay arrived at Fort Campbell on 13 April, where he, four hundred soldiers, and the returning divisional colors met a celebrating crowd that gathered at the base’s airfield. For security, some soldiers remained in Saudi Arabia with the division’s equipment while it was moved to Saudi ports for shipment back to Fort Campbell. The last "Screaming Eagle" soldier left Saudi Arabia for home on 1 May 1991.

In this interview, MG Peay offers his personal insights into his actions

as commander of the 101st during DESERT STORM while the historic events

were fresh in his mind. He explains how he prepared the 101st to fight,

and how they moved, fought, and thoroughly dominated Iraqi forces. What

is so significant, but difficult to appreciate, is the pace and range of

the 101st’s operations. In the midst of war, division elements moved 150

miles north behind enemy lines in two days and then turned east to continue

the attack. Greatly dependent on aviation for mobility, the 101st travelled

far greater distances and employed more firepower than pre-AirLand Battle

planners would have imagined.

NOTES

1 The 1993 edition of FM 100-5, Operations, was first based on the operational experiences of recent combat in Panama and Southwest Asia, and its authors added "versatility" as a fifth tenet.

2 The 101st was part of the XVIII Airborne Corps, the Army's rapid deployment force, headquartered at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, under the command of LTG Gary E. Luck. Other major units in the corps (prior to DESERT SHIELD) included the 82d Airborne Division, 24th Infantry Division (Mechanized), and the 10th Mountain Division (Light), as well as several separate brigades and a large number of corps level combat support and combat service support units.

3 The 197th Infantry Brigade arrived from Fort Benning, Georgia by the middle of September and was attached to the 24th Division as its third divisional brigade.

4 The 1st "Tiger" Brigade, 2d Armored Division,

which deployed as the 1st Cavalry Division's third brigade, was attached

to the U.S. Marines to provide them with the extra firepower of the brigade's

Abrams M1A1 tanks.

I’ll simply say I was blessed with great people. Generals Hugh Shelton and Ron Adams were wonderful Assistant Division Commanders. Absolutely "pros" and also fun to be with. William (Joe) Bolt, the Division Chief of Staff, was a seasoned Colonel who had been the Division G-3 and a Battalion Commander in the division earlier. Tough and qualified across the board from tactics to finance. Stephen Weiss did what you wanted the Division Command Sergeant Major to do. Out and about, fixing problems, enforcing standards, and supporting the NCOs. All the Colonel Commanders did superbly. Randy Anderson, the DIVARTY [Division Artillery] Commander, pulled together a most sophisticated fire support plan in the covering force and rehearsed it; our air defense, signal, and engineer troops were always committed. They never had a break from the time of deployment until we returned to Campbell. And the DISCOM [Division Support Command]—aviation maintenance, main support, S&T, medical, etc.—kept the troops going forward. Stu Gerald managed all that ably backed up by a splendid 101st Corps Support Group that reconfigured "on the fly" from a TDA to TOE organization (at Campbell) under Roy Beauchamp. Tom Garrett deployed within the first week of assuming command of our large aviation brigade and performed marvelously. Finally with Colonels Greg Gile, John MacDonald, Ted Purdom, Tom Hill, and Bob Clark, we had five great brigade commanders that led from the front and promoted standards throughout.

We had superb equipment with Apaches and Blackhawk helicopters, had "slimmed" our division structure down in size making it more versatile, had undergone a year of intensive training, and perfected our air assault doctrine and tactical techniques. All of this was enhanced by a proud history and hard-working professional soldiers, NCOs, and officers. The Screaming Eagles and the Army were blessed with this team. And the Army deserves a lot of credit for developing and growing these officers and this division. What a thrill and an honor to be in their presence.

MAJ WRIGHT: This is an Operation DESERT SHIELD/DESERT STORM interview with MG J.H. Binford Peay, III on 5 June 1991 in the Headquarters of the 101st Airborne Division, at Fort Campbell, Kentucky. The interviewing official is MAJ Robert K. Wright from the XVIII Airborne Corps History Office, along with Mr. Rex Boggs, Museum Curator, and 1LT Cliff Lippard, Division Historical Officer. General Peay commanded the 101st Division in Southwest Asia, 1990-1991.

Sir, what were the highlights of your military career prior to coming to the division; particularly those assignments that prepared you for the challenges you would face as the division commander during DESERT SHIELD and DESERT STORM?

MG PEAY: All of the assignments and duties are important. I think you have to look at the assignments you had as a youngster that helped teach you about soldiers and proficiency, as well as, perhaps, some of the career-building assignments that you had later that provide seasoning and obviously, also the great Army school system. I had some great NCOs guide, counsel, and teach me in troop assignments initially in Germany. Later, I had an assignment working for MG Autrey Maroun, former commanding general of the 5th Mech [5th Infantry Division] stationed at Fort Carson, in the 1965 time frame, as his senior aide. I learned a lot from that gentleman in terms of what goes on in divisions, and about standards and discipline.

Clearly, the company and battery commands that I had in Vietnam in the 1967-1968 period, two different commands there, gave me my first taste of the combat business . . . its horror and yet its boredom, and what you must demand as a commander in combat. And later, as a battalion S-3 on my second Vietnam tour in the 1st Cavalry Division, which was an airmobile division employing many of the concepts that we use today in the 101st.

I had a direct support artillery battalion in the 25th [Infantry Division] under COL [later LTG] Bill [William Henry] Schneider, who cared deeply about people and families, and logistics as well as artillery. MG [later GEN] [Robert] RisCassi was my division commander when I had a DIVARTY in the 9th [Infantry Division] at Fort Lewis. He was a superb and respected commander and teacher . . . using the innovative mission of the high-tech light division he was charged to experiment with and put on the ground . . . and taught us all so much about the fight at the operational level as well as institutionalizing advanced training doctrine. We had a wonderful time and the division was "packed" with great officers all working as a team. LTG

[18]

(Retired) John Brandenburg had I Corps and under his leadership he built it from ground-up, teaching us about command pace, style, responsibility, and decentralization. He also knew the reserve [component] business and we had a good time. Lewis was a terrific assignment.

Later, working for GEN John A. Wickham as his executive officer when he was the Chief of Staff of the United States Army, I learned a lot about officership from him . . . caring, values, ethics, leadership . . . and greatness. My tour in Command and General Staff College as the Deputy Commandant was very helpful in continuing to study the evolving doctrine, both tactical and operational. General [Carl E.] Vuono’s [Army Chief of Staff from 1987 through Operation DESERT STORM] imprint was placed on so many of us during this period. I could have stayed there five years. Finally, being the assistant division commander in the division for a year was very helpful in understanding the division and being current as to the challenges that lay ahead.

I really don’t think you can point to any one assignment. I was very fortunate to work for so many professionals over the years and their teaching and example were instrumental in the desert war.

MAJ WRIGHT: When, exactly, did you take over command of the division, sir?

MG PEAY: 3 August 1989.

MAJ WRIGHT: So roughly a year before the crisis started in Kuwait?

MG PEAY: A year ahead. I had been the assistant division commander and had only been gone from the division for one year, so I was very fortunate in a four-year period to have spent three years in the division.

MAJ WRIGHT: What was the focus of the training program within the division on the eve of the crisis? In other words, what scenarios had you been looking at for the potential employment of the division before the deployment to Kuwait?

MG PEAY: We were a multipurpose division that was training across the spectrum of conflict. In the three months prior to the alert, we were training more on the Latin American scenario—and the Caribbean—against a number of different war plans that we had focused in that area. But ninety days prior to that we had worked high-intensity scenarios, and we had just come off a CPX [Command Post Exercise] at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, where we had worked Southwest Asia as the focus of our war plan.

MAJ WRIGHT: That was INTERNAL LOOK?

MG PEAY: Yes, INTERNAL LOOK.

MAJ WRIGHT: Was that a useful exercise in terms of preparing you; or was it somewhat deceptive in the sense that it was a map exercise?

MG PEAY: Well, I think it was helpful in that it put the focus back on the Middle East. We had focused a lot on the Middle East the previous year in our CPXs and map exercises. So after a

[19]

year, INTERNAL LOOK gave us the chance to focus back on that region. In terms of exact terrain analysis and all that, the actual map exercise was not properly set. It was focused in the Al Hufuf area [south southwest of the city of Dhahran] in Saudi Arabia, not in the covering force or Rafha [a Saudi city close to Iraq] area, where we finally kicked off DESERT STORM. So the locations were different, but some of the terrain was similar. The employment considerations going over there were about the same and we got to work the battle staff and the BOS [Battle Operating System].

MAJ WRIGHT: What was the sequence of events in alerting the division, sir? When did you get first word to stand by and then start moving?

MG PEAY: I was at Virginia Beach, Virginia, on leave with my family when the word came down. BG [Henry] Hugh Shelton and BG Ron Adams, and COL Joe Bolt, division chief of staff, started through the normal kind of N-Hour alert procedures.1 The division duty officer notified the commands through our Emergency Operations Center. And then we started the normal kinds of things that we had trained and trained for with corps and division EDREs [Emergency Deployment Readiness Exercises]—movement to US Atlantic Command Field Training Exercise OCEAN VENTURE, movement to JRTC [Joint Readiness Training Center, Fort Chaffee, Arkansas] and NTC [National Training Center, Fort Irwin, California]. So there was nothing out of the ordinary except this one was for real. I came back from leave within a couple days. Back here, I just fitted into the process that was well under way at that time. The team was already moving.

MAJ WRIGHT: That was a benefit of the division having an Notification-Hour sequence and a regular EDRE program. When you got the word to go, everybody knew what they were supposed to do; you didn’t have to do a lot of reinventing the wheel at the last second.

MG PEAY: Well, that was a benefit. We had trained at that hard, but the real difference was that we were a "seasoned team." We’d been together for a year, and some of us had been together for three years. We knew each other intimately, knew by the sound of our voices if we had a problem we had to work on, felt we could discuss problems openly, and always were focussed on how to make the air assault business more proficient and innovative. From my perspective, it rolled just like clockwork. It was greased. We met all the timelines and deployed out by rail, sea, convoy, and strategic air.

MAJ WRIGHT: As the division started deploying, were you given a free hand in configuring the package in increments? Were you told to go "shooters heavy" [priority on combat elements] . . . ?

MG PEAY: We were directed early on to send the Apache [AH-64] gunship helicopter battalions early, followed by the Cobras [AH-1S, helicopter gunships].2 We were reinforced with an

[20]

Apache battalion from Fort Rucker and were told to send major elements of the Aviation Brigade first. The Division Ready Brigade [DRB] moved out next, which is a little different sequence. It’s a different order of move-out procedure. We normally fall out in brigade task forces with full combat support and combat service support slices. In this case, they wanted the Aviation Brigade "pure." There were no major problems. We just had to juggle it, and change the order of march out of here. We followed that force right behind with the Division Ready Brigade and the rest of the division.

MAJ WRIGHT: Was Jacksonville, Florida the normal port that the division had assumed it would go out of?

MG PEAY: Yes.

MAJ WRIGHT: So everybody knew the strip maps and knew the route?

MG PEAY: Well, we had gone to Jacksonville with certain of our leadership on TEWTs [Tactical Exercise Without Troops], but we had never moved significant elements to Jacksonville. We had to go down there and fall in with our own port team and with a port support agency that was put together to also help us out from Fort Benning, Georgia, [the army base nearest to Jacksonville]. Those were new procedures that had to be worked out, but professionals made them quickly come together. Really, it was not the bottleneck that it could have been, and I think the reason for that was the flexibility of the leadership.

MAJ WRIGHT: Did most of your materiel move by ground convoy? Did your helicopters self-deploy?

MG PEAY: We moved the division [equipment generally] by ground convoy. The 101st Corps Support Group followed right behind it by rail. So we could have gone either way. We practiced both procedures. The speed of this thing just had the ground convoys closing a lot quicker, so we got that underway, and then as the rail cars got in here and got going, we followed by rail; self-deployed our helicopters to Jacksonville.

The strategic air movement of the men and equipment of our aviation brigade and our 2d Brigade went from Campbell Army Airfield by U.S. Air Force aircraft. Then our other soldiers departed in the follow-on flights of Civilian Reserve Air Fleet [CRAF].3 This multi-faceted move was well coordinated. In addition, the 5th Special Forces Group stationed at Campbell flowed simultaneously with our 3rd Brigade. So Campbell Army Airfield and the Garrison Support and Post Trans[portation] Team were very busy.

[21]

MAJ WRIGHT: Did that move have to be timed to insure that the soldiers didn’t arrive in Saudi Arabia too far ahead of the ships?

MG PEAY: Right. We held them. The average sailing time was twenty to twenty-one days. All ten of our ships—1.2 million square feet—made it in that particular time frame. We did not have any significant problems on the seas, so we closed our soldiers and married them up with the ships . . . and then married the full division together in Saudi Arabia, closing with those that went early by strategic airlift.

MAJ WRIGHT: What kind of threat did you expect in the initial days of your deployment? Did you figure that you would have to fight your way ashore?

MG PEAY: No, we were not going to fight our way ashore, but we thought that we could be in combat in a very short period after arrival. That’s why we tactically configured all of our loads, and went out as a combined arms team, with the Division Ready Brigade. As it turned out, we were not going to go immediately into combat, although we had the farthest north mission in the covering force. We then started configuring to have our passengers meet their equipment, draw it at port, and march north up into sector.

MAJ WRIGHT: In terms of your aviation assets, did you push out very early the Apache-heavy force with the associated scout helicopters, as well?

MG PEAY: Are you talking strategically or tactically?

MAJ WRIGHT: The strategic deployment.

MG PEAY: Normally, we don’t. Normally, we send out the Division Ready Brigade, which has an Apache element with it. It has a cavalry element, a lift element, a field artillery element. At this time, GEN H. Norman Schwarzkopf, CINC CENTCOM [Commander in Chief Central Command], called for the Apaches first. I think he did that for defense and deterrence purposes, sending a signal that we had this anti-tank capability on the ground and were prepared to use it.

MAJ WRIGHT: So as the rest of the division flowed in, then you were able to return to your habitual brigade relationships?

MG PEAY: The same habitual brigade organization, but it was also the integration of all the aviation across the division back under the division fold.

MAJ WRIGHT: Through all this time, did you also have the added responsibility for picking up the 12th Aviation Brigade as it flowed in from Europe?

MG PEAY: No. After we were in-country awhile, we were informed the 12th Aviation Brigade was going to come, and at that time XVIII Airborne Corps assigned them under our [the 101st’s] operational control. We did not know we would get them until several weeks after we were in country.

[22]

MAJ WRIGHT: Did that pose any problem, or was the division staff, because of dealing with so many helicopters, able to just accept another aviation brigade—a second aviation brigade?

MG PEAY: I don’t think it caused any problems. We went through the normal staff lay-down on receiving a unit, which gave us increased divisional capability. I was glad to have them. They had a splendid, splendid commander in COL Emmett Gibson. A quiet professional. I thought we worked very well together as a team. They were a great addition, a great command.

MAJ WRIGHT: The Apache battalion out of Fort Rucker—the 2d Battalion, 229th Aviation—was added to the division from a corps-level asset?

MG PEAY: Right.

MAJ WRIGHT: So at some point, say in late September when the 12th was up and functioning, you were controlling four or five gunship battalions?

MG PEAY: Yes, four Apache battalions; one AH-1 Cobra battalion and a cav[alry] AH-1 Cobra battalion; three UH-60 lift battalions; a command [and control] battalion of thirty UH-1H Hueys and then the forty-five CH-47s Chinook cargo helicopters in our Chinook battalion.4

MAJ WRIGHT: So at that point you had one of the larger air forces in the world, if it were ranked that way.

MG PEAY: Well, I don’t know if it’s an air force. We had, with no question, the largest helicopter fleet in the world under our division’s control.

MAJ WRIGHT: As you built that fleet up, had you experienced any learning curve on the staff, to realize that things were going well, or that there were things that needed to be fixed?

MG PEAY: Well, your question hits at the acclimatization challenge .

. . the impact on fuel and maintenance and all that business. We knew for

years in our division that you had to pay close attention to fueling and

maintenance. We called fueling "the Achilles heel" of our division. There

was a lot of safety considerations involved in that. There was a lot of

robustness; there were new pumping systems, many storage bags, ammo, and

fuel lines to be careful with in high temperatures and blowing sand. We

worked all through that, and we knew those were the challenges. We just

took time to work them, and we had the "pros" that could work them. So

what had been our stateside problem just became a larger problem, in terms

of magnitude, based on the volume that we now were supporting in the fight

and the hot temperatures and sand.

[23]

We did a lot of smart things acquiring newer pump systems, more fuel bladders, more fuel bags, more sling gear. We did a lot of "matting" work to hold the dust down. Painted blades every night to work against blade erosion. Built up our "bank" time, [hours of flying time prior to scheduled maintenance]. Those kinds of things. We got a few clamshells5 so our great maintainers could work around the clock under those things to keep the birds turning, from a maintenance perspective. Flushed all of our engines, used sanators6 out of our chemical company to help do that. We just got very serious about maintenance and safety training, and quickly spread those lessons learned throughout the division and our recently attached units. We learned how to put in these, what appeared to be semi-fixed facilities, i.e., matting or putting down oil solutions to hold the dust down and clamshells. We learned how to do that very quickly, so we could maintain the pace of operations and maintain our fleet, and we tried to think of ways to rest our aviators in the heat of the day as they had to fly at night.

MAJ WRIGHT: As the division settled into its initial base area, Camp EAGLE II at King Fahd International Airport, did you have any problems in getting space allocated for the division’s flight line, since you had, I think, special operations people there and the Air Force was also a heavy user of that facility?

MG PEAY: Well, anytime you’ve got projection armies that are going to go into a relatively bare-base kind of environment, you run through the initial frustrations of acquiring land and where you’re going to set up, and that kind of thing. We had some frustrations involving that, but I wouldn’t describe them as major problems.

We were allocated a portion on King Fahd International Airport for our helicopters. It was obviously way too crowded. Yet at the same time, we didn’t want to put the fleet initially way out in the desert and have it "go to its knees" because of maintenance problems, because we didn’t have the gear in there initially to provide the protection and maintenance of the fleets on the desert floor. So we moved the division to a place we built called Camp EAGLE II, about five miles northwest of King Fahd Airport; we set up a ten thousand man base camp there to get our soldiers under cover. When we got there, it was 142 degrees on the airfield tarmac, and 128 degrees on the desert floor, so we had to get the soldiers under cover, or else they just wouldn’t have made it.

The same problem then accrued to the aviation fleet. We ended up putting our aviators, our battalions, in the King Fahd parking lot to get them under cover. Now that parking lot also was reinforced cement, so it provided some defense also in terms of incoming [SS-1C] SCUD rounds and those kinds of things. We had our engineers look at all that. We felt that it did offer protection and it was massive in size, but I always worried about the terrorist problem. We never liked this solution, but we had to get our aviation team quickly under cover.

We were concerned all along with the volume of aviation on that airport. I never was comfortable with that arrangement either. Incoming missiles, terrorist threats, and aircraft safety were our concerns. So we quickly started moving forward to the covering force area as the

[24]

brigades closed with their slices. We set up a rotating concept, where we kept two-thirds of the division forward for thirty days, and one-third of the division back at Camp EAGLE II and at King Fahd airport. We rotated those in triangular fashion: thirty days forward, fifteen days back. This allowed us to do some extensive training in the covering force. It provided our aviation and the rest of our materiel a bed-down place much further north, where it had a better reaction and response posture; and insured greater security from incoming SCUDs back at King Fahd, because we’d thinned down the fleet.

Yet at the same time these actions allowed us to come back and stand down our soldiers [the brigade Task Force teams] for a number of days, to do some close-in training, recovery, maintenance, and that kind of good stuff across the entire division. So that was the concept.

MAJ WRIGHT: As you set up the two forward brigades, one worked out of Forward Operating Base BASTOGNE [just south of the city of An Nu’ayriyah] and the other one out of Forward Operating Base OASIS [to the west of BASTOGNE and south of AO NORMANDY]?

MG PEAY: That’s right.

MAJ WRIGHT: And your position there was to provide anchors on both ends of the covering force area,7 as a pivot on each end of the line for your defensive mission?

MG PEAY: Well, those two bases were set up, because they were at about the right distance that would support this enormous covering force. There we received additional units, the 12th Combat Aviation Brigade that you mentioned, plus we received the 3d Armored Cavalry Regiment [ACR] out of Fort Bliss, Texas, and the 75th and 212th Field Artillery Brigades from Fort Sill, and a number of other smaller attachments, MP [Military Police] companies, Chemical companies, those kinds of things.

We set up two Forward Operating Bases [FOBs], BASTOGNE and OASIS, that were about a four-plus hour road march north of Camp EAGLE II, an hour-plus by Blackhawk. Then forward of those forward operating bases were our 1st, 2d and 3d Brigades; the 3d Armored Cavalry Regiment; the 12th Combat Aviation Brigade; our Aviation Brigade itself; and two large Field Artillery brigades out of Fort Sill, Oklahoma. We had all those working for us in this enormous covering force. It covered New Hampshire and Vermont in terms of size. Forward of those operating bases, we put in a new logistical concept, known as logistical assault bases [LABs], that worked in tandem with the forward operating bases, where we "tailored and reduced logistics" so it was very flexible. We concentrated on the significant supplies, the war-fighting supplies only, and that allowed us to be very mobile. That’s how we set the covering force and then rehearsed our plans a number of times. Finally we placed the Division Assault Command Post forward at BASTOGNE.

MAJ WRIGHT: The covering force battle being essentially given to the 101st, with the attachments, put a great deal of stress on you, because you served as the linkage between the main battle area of the XVIII Airborne Corps and the EPAC [Eastern Province Area Command] forces that were up forward to the north: the Gulf Cooperation Council units and the Saudi forces up

[25]

forward. And to a certain extent, you also had a coordination problem with the Marines on your seaward flank, or eastern flank.

How had you envisioned the hand-over of the battle involving all those different elements?

MG PEAY: Well, we put liaison teams forward with the Saudis. The Saudis also had special operations forces that we worked with as well. The combination of the liaison teams and the special operating forces teams allowed us then to work the reinforcing fires from the United States Air Force, from our own Apaches, and our long range field artillery. So the first thing we did was try to work through the coordination process, to call for fires, to reinforce with fires, in case those forces were getting hit.

From there we attempted, not with enormous success, to work detailed plans of passage of lines as to where the Saudis would pass through [heading south]. We were never able—with final authority—to understand if they would pass to the south for a short distance and then cut over to the east to the coast, or if they would pass [due south] on through our covering force, back to the 24th Infantry Division main battle area and then to the rear. That was one of the frustrations, among others, getting our hands around everyone in our zone and orchestrating the action.

The Marine Corps was on our right. We had a boundary. There was some concern between the two forces as to whether a part of that flank was open and not secure, because forces were or were not physically on the ground.

MAJ WRIGHT: In terms of how you envisioned the defensive battle being fought had the Iraqis come across the border, did you see them coming in a single, heavy push down the coast or did you envision that they would come in a broad front?

MG PEAY: I can really only speak to my part of that. In our portion, the corps portion, we perceived an attack by three divisions in the first echelon. Two of those divisions would come straight south, towards An Nu’ayriyah [city near FOB BASTOGNE], which our troops nicknamed "Bastogne," because of the same semblance of arteries and lines of communications to our previous history.8 So we envisioned an attack straight down through our covering force by two divisions, with the third division (reinforced) coming in from the northwest, then south, and then turning southeast, right down the TAPLINE [Trans-Arabian Pipeline] Road. The correlation [or balance] of forces was weighted to the enemy in terms of artillery and tanks. Yet, the way we put the covering force in and the combined arms fight we were going to fight; the fact that we knew the ground; the fact that we had rehearsed it and rehearsed it and rehearsed it, and trained on it—made me very confident that the Iraqis would run into a wall of fire with all the reinforced artillery that we had; all the TOWs [Tube-launched, Optically-tracked, Wire-guided antitank weapons] that we had deployed in mobile teams; our Air Force; and our Apaches. Frankly, I don’t think he would have gotten through the covering force area.

MAJ WRIGHT: As the plan was laid out, assuming that you had handed over the fight then to the main battle area, did you have an assignment to pass through the 24th, reconstitute, and then participate in the counterattack with the 1st Cavalry Division?

[26]

MG PEAY: No, we . . . [would not have passed] through the 24th. The 3d ACR . . . [was to pass] through the 24th and. . . to corps reserve. They . . . [would be] detached from me once they crossed into the main battle area. The 12th Combat Aviation Brigade passed back through our 3d Brigade and went to an assembly area where they offered local counterattack capability. Our other brigades conducted a normal covering force mission. Pulling back, passing through—in the case of our 1st Brigade passing through our 2d Brigade. Our 3d Brigade came on back through the 24th and cut over to the west, and then we reformed the division as a "guard force" on the west side of the 24th Division. We then were prepared to provide a screen cover along the west side of the 1st Cavalry Division that had the counterattack mission as it counterattacked from the south to the north, with focus to the east.

MAJ WRIGHT: Had it gone to that stage, and had we gone to a counterattack, did you envision, because you had such a preponderance of the deep strike assets within the corps, that you would be stretched to maintain the pressure and the pace? If we counterattacked, did you see the enemy collapsing fairly quickly so that we could have made a big dash towards Kuwait?

MG PEAY: No, I don’t think we went that far with it. At that stage we were never considering anything more than a reestablishment of a new covering force area north of the 1st Cav, and then to await instructions for future operations.

MAJ WRIGHT: In October, as the theater starts maturing, I know from your situation reports and commander’s comments in the situation reports that you began talking a lot about the importance of planning for future operations and envisioning what the mature theater would look like. Would you elaborate a little bit on what your thinking was, and how the Army starts looking at the build-up of force?

MG PEAY: I’m not so sure I ever got a good feel for what the mature theater would look like. I understood the XVIII Airborne Corps part of it. I always had concerns about enough haul capability at the theater level or the ability to distribute supplies internal to the theater as our outfit was daily providing trucks and lift helicopters. And that’s not a knock on the theater, it’s just a part of how you have to fight, and there were a lot of priorities. The VII Corps was coming in, and as we moved to a new mission, I wanted to come back south and do one or two days of refitting before moving that far to the west for the attack. So I’m not sure the theater ever really got mature. And I’m not so sure it ever would, under these circumstances.

MAJ WRIGHT: I guess the theater gave the 101st responsibility to chop [or attach] one brigade to VII Corps to help them as they displaced into the desert, and sort of screen them. Did that cause you some problems, given the fact that you had wanted to get that stand-down time to do maintenance?

MG PEAY: Well, it wasn’t so much getting stand-down time to do maintenance. I just wanted to do a little refit across the board: from soldier uniforms to issuing ammunition, to going over rules of engagement, to giving the soldiers some rest and cleanliness one final time. I just wanted to do some basic soldier business in EAGLE II for a couple days. There was no problem.

[27]

Again, I think it’s part of our EDRE program back at home, and it’s the capability our division has. CENTCOM wanted a force that could very quickly get over to the Hafar al Batin [a town near the TAPLINE Road and adjacent to] the Wadi al Batin area [that extended northward to Iraq], to protect against what was perceived as a spoiling attack on the night of I believe the 15th or 16th of January.

We alerted our 2d Brigade, because it was well forward in the covering force area. Moved it by our organic aviation and ground [transportation assets]. We gave it one of our division Apache battalions, a lift battalion, an artillery battalion, and further beefed up the brigade task force and quickly moved in (in less than a two-day period) up in the Wadi area. At that time, 2d Brigade commanded by COL Ted Purdom was "chopped" initially to VII Corps, and then later "chopped" to the 1st Cavalry Division, that came up from the south to provide protection in the King Khalid Military City [KKMC] area [south of TAPLINE Road]. We did that, and then we continued with our plans to take the division (minus) back down south [for refitting] and then start the seven-day movement of forces far to the northwest [all in January].

MAJ WRIGHT: As you worked through the movement to the west, how soon in the planning process had you been alerted by corps that you would be going way out to the west?

MG PEAY: We had been working a war plan out there since mid-December. In fact, we called it DESERT RENDEZVOUS I and then DESERT RENDEZVOUS II, as I recall. The first plan had us far, far to the west. That was logistically unsupportable,9 because of the distances, and secondly, it did not meet the time lines, logistically, from the viewpoint of the rest of the theater. We could not use up the theater’s haul [transportation] assets to push us that far west, because if you take away from those haul assets, they would not be able to move the rest of the corps, or the rest of the theater. So we developed a RENDEZVOUS II plan, which brought us a good thirty-five miles east of Rafha where we eventually launched our attack from assembly areas in that location [Tactical Assembly Area (TAA) CAMPBELL].

So from December on, we had been eyeing that area, and had started conceptual thinking on how to move the division that way. I think our training at home, particularly the way that we had "multi-deployed," [using different transportation modes to move different elements of the division] going to Saudi Arabia as well as to many of our training exercises, enabled us then to multi-deploy the division strategically, intra-theater, by U.S. Air Force [C-130 Hercules aircraft], by ground transport with the division transportation office, and by self-deploying our aviation assets. That combination closed the division in seven days.10

MAJ WRIGHT: Which represented a substantial movement of men and materiel over a fairly substantial distance.

[28]

MG PEAY: I think we went more than 700 miles to Rafha plus all our necessary supplies to fight.

MAJ WRIGHT: In the corps scenario for what would turn out to be DESERT STORM, was the 101st always envisioned, as the corps evolved that plan, as the deep strike capability of the corps when it went to the offense?

MG PEAY: I don’t know if "always." I think it was for this plan. There was some consideration of having the 82d Airborne Division jump. They discounted that because of winds, desert conditions, unknown enemy situations, and they also wanted the 82d to be with the smaller French division, and so they decided not to jump. So our division had the mission that we had trained for, for years.

MAJ WRIGHT: And this was the first time ever that we had attempted to fight that deep a battle. We’ve trained on it, but this was the first time that it was ever really executed, in the sense of being able to project that kind of force that deep by other than a jump.

MG PEAY: It’s the first time in history that we put that many aircraft and that many sorties on one day that far north. For DESERT STORM, we basically went 155 miles north to [AO EAGLE]; 95 miles the first day [to FOB COBRA]. We reached 155 miles the second day [AO EAGLE at LZ SAND]. The first day alone we flew about 370-plus aircraft and over a thousand sorties on G-Day alone, 24 February.

MAJ WRIGHT: You felt fairly confident with your staff. As you looked at the mission that you had been given by LTG Gary Luck [Commanding General, XVIII Airborne Corps] to put the force into what would be FOB COBRA in Iraq, were you confident that you could accomplish that mission? Were you confident that you were trained and ready to go?

MG PEAY: Well, I felt we were seasoned. The pace of training at Campbell, the NTC, and JRTC plus corps exercises the previous year had been enormous. The six months in the desert just "added" to it. Our soldiers were battle-hardened, or desert-tough before we went in. Our team was well greased and oiled. Our "battle notes" were solid.11 We had rehearsed and practiced a lot things in that six months over there. Then we went to the reconnaissance phase, G-minus, it turned out to be a ten-day reconnaissance. We had planned for seven, but in the ten-day reconnaissance period we got a pretty good feel for what was out there [north of TAA CAMPBELL].

We took down some of those air defenses early on. We captured an enemy infantry battalion.12 We learned a lot about the battlefield, talking to those guys. We learned a lot about their soldiers. I felt there was enough distance in there to evade the air defense concerns, and I thought we could get deep, then, particularly after we talked to some of the EPWs [Enemy

[29]

Prisoners of War]. I just didn’t feel that they were the same kind of soldiers that we had in our Army. I also didn’t think they knew where we were. So when we attacked out of there on G-Day, it turned out that was true. We got very deep, long before the enemy knew it.

MAJ WRIGHT: As you assigned the taskings internally within the division for the execution of the plan, what factors came into play in assigning the different brigades their responsibilities?

MG PEAY: Well, each of the brigades could have done any of these missions. I was very comfortable with COL Tom Hill in 1st Brigade, because we had done quite a bit of work on setting up forward operating bases with his brigade where we had to get a lot of fuel in and built-up quickly. I knew that Tom Hill understood my intent in terms of what I wanted done logistically to support this operation, so I was very comfortable in continuing to give him that mission.

The 2d Brigade was late closing in the TAA [Tactical Assembly Area CAMPBELL]. They closed during the reconnaissance period before G-Day, so I didn’t want to give them the initial shot, 155 miles deep. I wanted to go with Bob Clark and the 3d Brigade, because they were available, and we could do more rehearsing and go over the plans in great detail with him, without doubling up COL Ted Purdom, [the 2d Brigade commander] with several additional plans to think about at that time.

So the concept then was to let Hill go in first [to FOB COBRA]; let Clark follow deep [to AO EAGLE]; bring Purdom up to COBRA very quickly; and then have Purdom conduct a similar kind of thing as Clark, far to the east to FOB VIPER, as we headed toward Tallil and then Basra.13 Any of the three brigades could have done the missions, any of the missions, whether it was setting up and securing the logistical bases, conducting the air assaults, or cutting lines of communication deep.

MAJ WRIGHT: In terms of the task structure, you beefed up 1st Brigade with an additional battalion for that first day, to . . . ?

MG PEAY: To seize the objective. Forward Operating Base COBRA was two-thirds the size of the entire Fort Campbell area. We spread it out because I wasn’t sure of the chemical threat, and I did not want to have a midair accident in there at night during refueling. So we put in an enormous number of fuel bladders and fuel blivets14 and hosing, and we wanted to get some business done in a hurry. So we put four infantry battalions in there, and a hot refuel kind of thing to push out the aircraft as quickly as possible around the clock. Simultaneously, the Chinook guys brought in bladders of fuel to build up that capability for the attack and the lift birds to use. LTC John D. Broderick [Commander, 426th Supply and Transport Battalion] did some remarkable innovation in the fuel and pump business as he set up what the troops nicknamed a bunch of "7-Eleven stores with gas."

MAJ WRIGHT: In terms of how the division employs its infantry for any kind of operation, it is pretty much the way you actually used them in this one. The infantry were part of the com-

[30]

bined arms team. Therefore, you had to have the artillery up with them, their TOWs had to be up with them, and then you worked them very closely with the helicopters so that they worked out of the same bases. You didn’t have some of the communications problems that earlier generations had. I’m thinking about the use of the helicopter in Vietnam, bringing them in and then having the helicopters take off again and just leaving your troops out there. It’s one difference I noticed, for example, from the airmobile usages in Vietnam to the air assault techniques today. On the eve of G-Day, the 1st Brigade camped right alongside the helicopters they would board in the morning; and then at COBRA, the helicopters were always within that same area. Did this arrangement result in tighter bonding, more teamwork, maybe?

MG PEAY: Well, that’s generally correct. You can do it both ways. Compared to most units, I think, we have a more integrated approach to aviation in our unit. But then you can use the infantry in different ways. You can use the infantry to secure the aviation at times, while you go deep with the aviation; or you can use the aviation to be quickly available to move the infantry around the battlefield to cut the various lines of communication or destroy the enemy. In this war we did both of them.

MAJ WRIGHT: And again, having your own aviation assets inherently gave you flexibility over, say, a standard infantry division?

MG PEAY: No question about that. You know a lot of people say we are a light division. We really are kind of a "medium" division. We’re a multipurpose division that can do both—fight low and high intensity. So it’s a special division in terms of its structure, its organization, and brings those special pieces to the battle area. In this case, it was assigned suitable missions. The missions that we had were exactly the right ones for our division.

MAJ WRIGHT: Strike deep, cut the lines of communications, and . . .

MG PEAY: Speed, mobility, agility, great anti-tank capability . . . versatility.