CHAPTER 1.6. FROM 15TH OCTOBER, 1872 TO 31ST JANUARY, 1873.

Move the camp to new creek. Revisit the pass. Hornets and diamond birds. More ornamented caves. Map study. Start for the mountain. A salt lake. A barrier. Brine ponds. Horses nearly lost. Exhausted horses. Follow the lake. A prospect wild and weird. Mount Olga. Sleepless animals. A day's rest. A National Gallery. Signal for natives. The lake again. High hill westward. Mount Unapproachable. McNicol's range. Heat increasing. Sufferings and dejection of the horses. Worrill's Pass. Glen Thirsty. Food all gone. Review of our situation. Horse staked. Pleasure of a bath. A journey eastward. Better regions. A fine creek. Fine open country. King's Creek. Carmichael's Crag. Penny's Creek. Stokes's Creek. A swim. Bagot's Creek. Termination of the range. Trickett's Creek. George Gill's range. Petermann's Creek. Return. Two natives. A host of aborigines. Break up the depot. Improvement in the horses. Carmichael's resolve. Levi's Range. Follow the Petermann. Enter a glen. Up a tree. Rapid retreat. Escape glen. A new creek. Fall over a bank. Middleton's Pass. Good country. Friendly natives. Rogers's Pass. Seymour's Range. A fenced-in water-hole. Briscoe's Pass. The Finke. Resight the pillar. Remarks on the Finke. Reach the telegraph line. Native boys. I buy one. The Charlotte Waters. Colonel Warburton. Arrive at the Peake. News of Dick. Reach Adelaide.

It was late in the day when we left Glen Edith, and consequently very much later by the time we had unpacked all the horses at the end of our twenty-nine mile stage; it was then too dark to reach the lower or best water-holes. To-day there was an uncommon reversal of the usual order in the weather—the early part of the day being hot and sultry, but towards evening the sky became overcast and cloudy, and the evening set in cold and windy. Next morning we found that one horse had staked himself in the coronet very severely, and that he was quite lame. I got some mulga wood out of the wound, but am afraid there is much still remaining. This wood, used by the natives for spear-heads, contains a virulent poisonous property, and a spear or stake wound with it is very dangerous. The little mare that foaled at Mount Udor, and was such an object of commiseration, has picked up wonderfully, and is now in good working condition. I have another mare, Marzetti, soon to foal; but as she is fat, I do not anticipate having to destroy her progeny. We did not move the camp to-day. Numbers of bronze-winged pigeons came to drink, and we shot several of them. The following day Mr. Carmichael and I again mounted our horses, taking with us a week's supply of rations, and started off intending to visit the high mountain seen at our last farthest point. We left Alec Robinson again in charge of the camp, as he had now got quite used to it, and said he liked it. He always had my little dog Monkey for a companion. When travelling through the spinifex we carried the little animal. He is an excellent watchdog, and not a bird can come near the camp without his giving warning. Alec had plenty of firearms and ammunition to defend himself with, in case of an attack from the natives. This, however, I did not anticipate; indeed, I wished they would come (in a friendly way), and had instructed Alec to endeavour to detain one or two of them until my return if they should chance to approach. Alec was a very strange, indeed disagreeable and sometimes uncivil, sort of man; he had found our travels so different from his preconceived ideas, as he thought he was going on a picnic, and he often grumbled and declared he would like to go back again. However, to remain at the camp, with nothing whatever to do and plenty to eat, admirably suited him, and I felt no compunction in leaving him by himself. I would not have asked him to remain if I were in any way alarmed at his position.

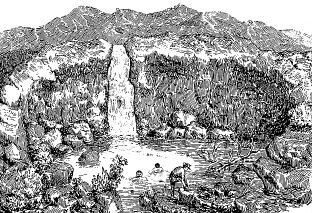

We travelled now by a slightly different route, more easterly, as there were other ridges in that direction, and we might find another and better watering place than that at the pass. It is only at or near ridges in this strange region that the traveller can expect to find water, as in the sandy beds of scrub intervening between them, water would simply sink away. We passed through some very thick mulga, which, being mostly dead, ripped our pack-bags, clothes, and skin, as we had continually to push the persistent boughs and branches aside to penetrate it. We reached a hill in twenty miles, and saw at a glance that no favourable signs of obtaining water existed, for it was merely a pile of loose stones or rocks standing up above the scrubs around. The view was desolate in the extreme; we had now come thirty miles, but we pushed on ten miles for another hill, to the south-east, and after penetrating the usual scrub, we reached its base in the dark, and camped. In the morning I climbed the hill, but no water could be seen or procured. This hill was rugged with broken granite boulders, scrubby with mulga and bushes, and covered with triodia to its summit. To the south a vague and strange horizon was visible; it appeared flat, as though a plain of great extent existed there, but as the mirage played upon it, I could not make anything of it. My old friend the high mountain loomed large and abrupt at a great distance off, and it bore 8° 30´ west from here, too great a distance for us to proceed to it at once, without first getting water for our horses, as it was possible that no water might exist even in the neighbourhood of such a considerable mountain. The horses rambled in the night; when they were found we started away for the little pass and glen where we knew water was to be got, and which was now some thirty miles away to the west-north-west. We reached it somewhat late. The day was hot, thermometer 98° in shade, and the horses very thirsty, but they could get no water until we had dug a place for them. Although we had reached our camping ground our day's work was only about to commence. We were not long in obtaining enough water for ourselves, such as it was—thick and dirty with a nauseous flavour—but first we had to tie the horses up, to prevent them jumping in on us. We found to our grief that but a poor supply was to be expected, and though we had not to dig very deep, yet we had to remove an enormous quantity of sand, so as to create a sufficient surface to get water to run in, and had to dig a tank twenty feet long by six feet deep, and six feet wide at the bottom, though at the top it was much wider. I may remark—and what I now say applies to almost every other water I ever got by digging in all my wanderings—that whenever we commenced to dig, a swarm of large and small red hornets immediately came around us, and, generally speaking, diamond birds (Amadina) would also come and twitter near, and when water was got, would drink in great numbers. With regard to the hornets, though they swarmed round our heads and faces in clouds, no one was ever stung by them, nature and instinct informing them that we were their friends. We worked and waited for two hours before one of our three horses could obtain a drink. The water came so slowly in that it took nearly all the night before the last animal's thirst was assuaged, as by the time the third got a drink, the first was ready to begin again, and they kept returning all through the night. We rested our horses here to-day to allow them to fill themselves with food, as no doubt they will require all the support they can get to sustain them in their work before we reach the distant mountain. We passed the day in enlarging the tank, and were glad to find that, though no increase in the supply of water was observable, still there seemed no diminution, as now a horse could fill himself at one spell. We took a stroll up into the rocks and gullies of the ridges, and found a Troglodytes' cave ornamented with the choicest specimens of aboriginal art. The rude figures of snakes were the principal objects, but hands, and devices for shields were also conspicuous. One hieroglyph was most striking; it consisted of two Roman numerals—a V and an I, placed together and representing the figure VI; they were both daubed over with spots, and were painted with red ochre. Several large rock-holes were seen, but they had all long lain dry. A few cypress pines grew upon the rocks in several places. The day was decidedly hot; the thermometer stood at 100° in the shade at three o'clock, and we had to fix up a cloth for an awning to get sufficient shade to sit under. Our only intellectual occupation was the study of a small map of Australia, showing the routes of the Australian explorers. How often we noted the facility with which other and more fortunate travellers dropped upon fine creeks and large rivers. We could only envy them their good fortune, and hope the future had some prizes in store for us also. The next morning, after taking three hours to water our horses, we started on the bearing of the high mount, which could not be seen from the low ground, the bearing being south 18° west. We got clear of the low hills of the glen, and almost immediately entered thick scrubs, varied by high sandhills, with casuarina and triodia on them. At twelve miles I noticed the sandhills became denuded of timber, and on our right a small and apparently grassy plain was visible; I took these signs as a favourable indication of a change of country. At three miles farther we had a white salt channel right in front of us, with some sheets of water in it; upon approaching I found it a perfect bog, and the water brine itself. We went round this channel to the left, and at length found a place firm enough to cross. We continued upon our course, and on ascending a high sandhill I found we had upon our right hand, and stretching away to the west, an enormous salt expanse, and it appeared as if we had hit exactly upon the eastern edge of it, at which we rejoiced greatly for a time. Continuing on our course over treeless sandhills for a mile or two, we found we had not escaped this feature quite so easily, for it was now right in our road; it appeared, however, to be bounded by sandhills a little more to the left, eastwards; so we went in that direction, but at each succeeding mile we saw more and more of this objectionable feature; it continually pushed us farther and farther to the east, until, having travelled about fifteen miles, and had it constantly on our right, it swept round under some more sandhills which hid it from us, till it lay east and west right athwart our path. It was most perplexing to me to be thus confronted by such an obstacle. We walked a distance on its surface, and to our weight it seemed firm enough, but the instant we tried our horses they almost disappeared. The surface was dry and encrusted with salt, but brine spurted out at every step the horses took. We dug a well under a sandhill, but only obtained brine.

This obstruction was apparently six or seven miles across, but whether what we took for its opposite shores were islands or the main, I could not determine. We saw several sandhill islands, some very high and deeply red, to which the mirage gave the effect of their floating in an ocean of water. Farther along the shore eastwards were several high red sandhills; to these we went and dug another well and got more brine. We could see the lake stretching away east or east-south-east as far as the glasses could carry the vision. Here we made another attempt to cross, but the horses were all floundering about in the bottomless bed of this infernal lake before we could look round. I made sure they would be swallowed up before our eyes. We were powerless to help them, for we could not get near owing to the bog, and we sank up over our knees, where the crust was broken, in hot salt mud. All I could do was to crack my whip to prevent the horses from ceasing to exert themselves, and although it was but a few moments that they were in this danger, to me it seemed an eternity. They staggered at last out of the quagmire, heads, backs, saddles, everything covered with blue mud, their mouths were filled with salt mud also, and they were completely exhausted when they reached firm ground. We let them rest in the shade of some quandong trees, which grew in great numbers round about here. From Mount Udor to the shores of this lake the country had been continually falling. The northern base of each ridge, as we travelled, seemed higher by many feet than the southern, and I had hoped to come upon something better than this. I thought such a continued fall of country might lead to a considerable watercourse or freshwater basin; but this salt bog was dreadful, the more especially as it prevented me reaching the mountain which appeared so inviting beyond.

Not seeing any possibility of pushing south, and thinking after all it might not be so far round the lake to the west, I turned to where we had struck the first salt channel, and resolved to try what a more westerly line would produce. The channel in question was now some fifteen miles away to the north-westward, and by the time we got back there the day was done and “the darkness had fallen from the wings of night.” We had travelled nearly fifty miles, the horses were almost dead; the thermometer stood at 100° in the shade when we rested under the quandongs. In the night blankets were unendurable. Had there been any food for them the horses could not eat for thirst, and were too much fatigued by yesterday's toil to go out of sight of our camping place. We followed along the course of the lake north of west for seven miles, when we were checked by a salt arm running north-eastwards; this we could not cross until we had gone up it a distance of three miles. Then we made for some low ridges lying west-south-west and reached them in twelve miles. There was neither watercourse, channel, nor rock-holes; we wandered for several miles round the ridges, looking for water, but without success, and got back on our morning's tracks when we had travelled thirty miles. From the top of these ridges the lake could be seen stretching away to the west or west-south-west in vast proportions, having several salt arms running back from it at various distances. Very far to the west was another ridge, but it was too distant for me to reach now, as to-night the horses would have been two nights without water, and the probability was they would get none there if they reached it. I determined to visit it, however, but I felt I must first return to the tank in the little glen to refresh the exhausted horses. From where we are, the prospect is wild and weird, with the white bed of the great lake sweeping nearly the whole southern horizon. The country near the lake consists of open sandhills, thickly bushed and covered with triodia; farther back grew casuarinas and mulga scrubs.

It was long past the middle of the day when I descended from the hill. We had no alternative but to return to the only spot where we knew water was to be had; this was now distant twenty-one miles to the north-east, so we departed in a straight line for it. I was heartily annoyed at being baffled in my attempt to reach the mountain, which I now thought more than ever would offer a route out of this terrible region; but it seemed impossible to escape from it. I named this eminence Mount Olga, and the great salt feature which obstructed me Lake Amadeus, in honour of two enlightened royal patrons of science. The horses were now exceedingly weak; the bogging of yesterday had taken a great deal of strength out of them, and the heat of the last two days had contributed to weaken them (the thermometer to-day went up to 101° in shade). They could now only travel slowly, so that it was late at night when we reached the little tank. Fifty miles over such disheartening country to-day has been almost too much for the poor animals. In the tank there was only sufficient water for one horse; the others had to be tied up and wait their turns to drink, and the water percolated so slowly through the sand it was nearly midnight before they were all satisfied and begun to feed. What wonderful creatures horses are! They can work for two and three days and go three nights without water, but they can go for ever without sleep; it is true they do sleep, but equally true that they can go without sleeping. If I took my choice of all creation for a beast to guard and give me warning while I slept, I would select the horse, for he is the most sleepless creature Nature has made. Horses seem to know this; for if you should by chance catch one asleep he seems very indignant either with you or himself.

It was absolutely necessary to give our horses a day's rest, as they looked so much out of sorts this morning. A quarter of the day was spent in watering them, and by that time it was quite hot, and we had to erect an awning for shade. We were overrun by ants, and pestered by flies, so in self-defence we took another walk into the gullies, revisited the aboriginal National Gallery of paintings and hieroglyphics, and then returned to our shade and our ants. Again we pored over the little German map, and again envied more prosperous explorers. The thermometer had stood at 101° in the shade, and the greatest pleasure we experienced that day was to see the orb of day descend. The atmosphere had been surcharged all day with smoke, and haze hung over all the land, for the Autochthones were ever busy at their hunting fires, especially upon the opposite side of the great lake; but at night the blaze of nearer ones kept up a perpetual light, and though the fires may have been miles away they appeared to be quite close. I also had fallen into the custom of the country, and had set fire to several extensive beds of triodia, which had burned with unabated fury; so brilliant, indeed, was the illumination that I could see to read by the light. I kindled these fires in hopes some of the natives might come and interview us, but no doubt in such a poorly watered region the native population cannot be great, and the few who do inhabit it had evidently abandoned this particular portion of it until rains should fall and enable them to hunt while water remained in it.

Last night, the 23rd October, was sultry, and blankets utterly useless. The flies and ants were wide awake, and the only thing we could congratulate ourselves upon, was the absence of mosquitoes. At dawn the thermometer stood at 70° and a warm breeze blew gently from the north. The horses were found early, but as it took nearly three hours to water them we did not leave the glen till past eight o'clock. This time I intended to return to the ridges we had last left, and which now bore a little to the west of south-west, twenty-one miles away. We made a detour so as to inspect some other ridges near where we had been last. Stony and low ridgy ground was first met, but the scrubs were all around. At fifteen miles we came upon a little firm clayey plain with some salt bushes, and it also had upon it some clay pans, but they had long been dry. We found the northern face of the ridges just as waterless as the southern, which we had previously searched. The far hills or ridges to the west, which I now intended to visit, bore nearly west. Another salt bush plain was next crossed; this was nearly three miles long. We now gave the horses an hour's spell, the thermometer showing 102° in the shade; then, re-saddling, we went on, and it was nine o'clock at night when we found ourselves under the shadows of the hills we had steered for, having them on the north of us.

I searched in the dark, but could find no feature likely to supply us with water; we had to encamp in a nest of triodia without any water, having travelled forty-eight miles through the usual kind of country that occupies this region's space. At daylight the thermometer registered 70°, that being the lowest during the night. On ascending the hill above us, there was but one feature to gaze upon—the lake still stretching away, not only in undiminished, but evidently increasing size, towards the west and north-west. Several lateral channels were thrown out from the parent bed at various distances, some broad and some narrow. A line of ridges, with one hill much more prominent than any I had seen about this country, appeared close down upon the shores of the lake; it bore from the hill I stood upon south 68° west, and was about twenty miles off. A long broad salt arm, however, ran up at the back of it between it and me, but just opposite there appeared a narrow place that I thought we might cross to reach it.

The ridge I was on was red granite, but there was neither creek nor rock-hole about it. We now departed for the high hill westward, crossing a very boggy salt channel with great difficulty, at five miles; in five more we came to the arm. It appeared firm, but unfortunately one of the horses got frightfully bogged, and it was only by the most frantic exertions that we at length got him out. The bottom of this dreadful feature, if it has a bottom, seems composed entirely of hot, blue, briny mud. Our exertions in extricating the horse made us extremely thirsty; the hill looked more inviting the nearer we got to it, so, still hoping to reach it, I followed up the arm for about seven miles in a north west direction. It proved, however, quite impassable, and it seemed utterly useless to attempt to reach the range, as we could not tell how far we might have to travel before we could get round the arm. I believe it continues in a semicircle and joins the lake again, thus isolating the hill I wished to visit. This now seemed an island it was impossible to reach. We were sixty-five miles away from the only water we knew of, with no likelihood of any nearer; there might certainly be water at the mount I wished to reach, but it was unapproachable, and I called it by that name; no doubt, had I been able to reach it, my progress would still have been impeded to the west by the huge lake itself. I could get no water except brine upon its shores, and I had no appliances to distil that; could I have done so, I would have followed this feature, hideous as it is, as no doubt sooner or later some watercourses must fall into it either from the south or the west. We were, however, a hundred miles from the camp, with only one man left there, and sixty-five from the nearest water. I had no choice but to retreat, baffled, like Eyre with his Lake Torrens in 1840, at all points. On the southern shore of the lake, and apparently a very long way off, a range of hills bore south 30° west; this range had a pinkish appearance and seemed of some length. Mr. Carmichael wished me to call it McNicol's Range, after a friend of his, and this I did. We turned our wretched horses' heads once more in the direction of our little tank, and had good reason perhaps to thank our stars that we got away alive from the lone unhallowed shore of this pernicious sea. We kept on twenty-eight miles before we camped, and looked at two or three places, on the way ineffectually, for some signs of water, having gone forty-seven miles; thermometer in shade 103°, the heat increasing one degree a day for several days. When we camped we were hungry, thirsty, tired, covered all over with dry salt mud; so that it is not to be wondered at if our spirits were not at a very high point, especially as we were making a forced retreat. The night was hot, cloudy, and sultry, and rain clouds gathered in the sky. At about 1 a.m. the distant rumblings of thunder were heard to the west-north-west, and I was in hopes some rain might fall, as it was apparently approaching; the thunder was not loud, but the lightning was most extraordinarily vivid; only a few drops of rain fell, and the rest of the night was even closer and more sultry than before.

Ere the stars had left the sky we were in our saddles again; the horses looked most pitiable objects, their flanks drawn in, the natural vent was distended to an open and extraordinary cavity; their eyes hollow and sunken, which is always the case with horses when greatly in want of water. Two days of such stages will thoroughly test the finest horse that ever stepped. We had thirty-six miles yet to travel to reach the water. The horses being so jaded, it was late in the afternoon when they at last crawled into the little glen; the last few miles being over stones made the pace more slow. Not even their knowledge of the near presence of water availed to inspirit them in the least; probably they knew they would have to wait for hours at the tank, when they arrived, before their cravings for water could be appeased. The thermometer to-day was 104° in the shade. When we arrived the horses had walked 131 miles without a drink, and it was no wonder that the poor creatures were exhausted. When one horse had drank what little water there was, we had to re-dig the tank, for the wind or some other cause had knocked a vast amount of the sand into it again. Some natives also had visited the place while we were away, their fresh tracks were visible in the sand around, and on the top of the tank. They must have stared to see such a piece of excavation in their territory. When the horses did get water, two of them rolled, and groaned, and kicked, so that I thought they were going to die; one was a mare, she seemed the worst, another was a strong young horse which had carried me well, the third was my old favourite riding-horse; this time he had only carried the pack, and was badly bogged; he was the only one that did not appear distressed when filled with water, the other two lay about in evident pain until morning. About the middle of the night thunder was again heard, and flash after flash of even more vivid lightnings than that of the previous night enlightened the glen; so bright were the flashes, being alternately fork and sheet lightning, that for nearly an hour the glare never ceased. The thunder was much louder than last night's, and a slight mizzling rain for about an hour fell. The barometer had fallen considerably for the last two days, so I anticipated a change. The rain was too slight to be of any use; the temperature of the atmosphere, however, was quite changed, for by the morning the thermometer was down to 48°.

The horses were not fit to travel, so we had to remain, with nothing to do, but consult the little map again, and lay off my position on it. My farthest point I found to be in latitude 24° 38´ and longitude 130°. For the second time I had reached nearly the same meridian. I had been repulsed at both points, which were about a hundred miles apart, in the first instance by dry stony ranges in the midst of dense scrubs, and in the second by a huge salt lake equally destitute of fresh water. It appears to me plain enough that a much more northerly or else more southerly course must be pursued to reach the western coast, at all events in such a country, it will be only by time and perseverance that any explorer can penetrate it. I think I remarked before that we entered this little glen through a pass about half-a-mile long, between two hills of red sandstone. I named this Worrill's Pass, after another friend of Mr. Carmichael. The little glen in which we dug out the tank I could only call Glen Thirsty, for we never returned to it but ourselves and our horses, were choking for water. Our supply of rations, although we had eked it out with the greatest possible economy, was consumed, for we brought only a week's supply, and we had now been absent ten days from home, and we should have to fast all to-morrow, until we reached the depot; but as the horses were unable to carry us, we were forced to remain.

During the day I had a long conversation with Mr. Carmichael upon our affairs in general, and our stock of provisions in particular; the conclusion we arrived at was, that having been nearly three months out, we had not progressed so far in the time as we had expected. We had found the country so dry that until rains fell, it seemed scarcely probable that we should be able to penetrate farther to the west, and if we had to remain in depot for a month or two, it was necessary by some means to economise our stores, and the only way to do so was to dispense with the services of Alec Robinson. It would be necessary, of course, in the first place, to find a creek to the eastward, which would take him to the Finke, and by the means of the same watercourse we might eventually get round to the southern shores of Lake Amadeus, and reach Mount Olga at last.

In our journey up the Finke two or three creeks had joined from the west, and as we were now beyond the sources of any of these, it would be necessary to discover some road to one or the other before Robinson could be parted with. By dispensing with his services, as he was willing to go, we should have sufficient provisions left to enable us to hold out for some months longer: even if we had to wait so long as the usual rainy season in this part of the country, which is about January and February, we should still have several months' provisions to start again with. In all these considerations Mr. Carmichael fully agreed, and it was decided that I should inform Alec of our resolution so soon as we returned to the camp. After the usual nearly three hours' work to water our horses, we turned our backs for the last time upon Glen Thirsty, where we had so often returned with exhausted and choking horses.

I must admit that I was getting anxious about Robinson and the state of things at the camp. In going through Worrill's Pass, we noticed that scarcely a tree had escaped from being struck by the lightning; branches and boughs lay scattered about, and several pines from the summits of the ridges had been blasted from their eminence. I was not very much surprised, for I expected to be lightning-struck myself, as I scarcely ever saw such lightning before. We got back to Robinson and the camp at 5 p.m. My old horse that carried the pack had gone quite lame, and this caused us to travel very slowly. Robinson was alive and quite well, and the little dog was overjoyed to greet us. Robinson reported that natives had been frequently in the neighbourhood, and had lit fires close to the camp, but would not show themselves. Marzetti's mare had foaled, the progeny being a daughter; the horse that was staked was worse, and I found my old horse had also ran a mulga stake into his coronet. I probed the wounds of both, but could not get any wood out. Carmichael and I both thought we would like a day's rest; and if I did not do much work, at least I thought a good deal.

The lame horses are worse: the poisonous mulga must be in the wounds, but I can't get it out. What a pleasure it is, not only to have plenty of water to drink, but actually to have sufficient for a bath! I told Robinson of my views regarding him, but said he must yet remain until some eastern waters could be found. On the 30th October, Mr. Carmichael and I, with three fresh horses, started again. In my travels southerly I had noticed a conspicuous range of some elevation quite distinct from the ridges at which our camp was fixed, and lying nearly east, where an almost overhanging crag formed its north-western face. This range I now decided to visit. To get out of the ridges in which our creek exists, we had to follow the trend of a valley formed by what are sometimes called reaphook hills; these ran about east-south-east. In a few miles we crossed an insignificant little creek with a few gum-trees; it had a small pool of water in its bed: the valley was well grassed and open, and the triodia was also absent. A small pass ushered us into a new valley, in which were several peculiar conical hills. Passing over a saddle-like pass, between two of them, we came to a flat, open valley running all the way to the foot of the new range, with a creek channel between. The range appeared very red and rocky, being composed of enormous masses of red sandstone; the upper portion of it was bare, with the exception of a few cypress pines, moored in the rifled rock, and, I suppose, proof to the tempest's shock. A fine-looking creek, lined with gum-trees, issued from a gorge. We followed up the channel, and Mr. Carmichael found a fine little sheet of water in a stony hole, about 400 yards long and forty yards wide. This had about four feet of water in it; the grass was green, and all round the foot of the range the country was open, beautifully grassed, green, and delightful to look at. Having found so eligible a spot, we encamped: how different from our former line of march! We strolled up through the rocky gorge, and found several rock reservoirs with plenty of water; some palm-like Zamias were seen along the rocks. Down the channel, about south-west, the creek passed through a kind of low gorge about three miles away. Smoke was seen there, and no doubt it was an encampment of the natives. Since the heavy though dry thunderstorm at Glen Thirsty, the temperature has been much cooler. I called this King's Creek. Another on the western flat beyond joins it. I called the north-west point of this range Carmichael's Crag. The range trended a little south of east, and we decided to follow along its southern face, which was open, grassy, and beautifully green; it was by far the most agreeable and pleasant country we had met.

ILLUSTRATION 7

PENNY'S CREEK.

At about five miles we crossed another creek coming immediately out of the range, where it issued from under a high and precipitous wall of rock, underneath which was a splendid deep and pellucid basin of the purest water, which came rushing into and out of it through fissures in the mountain: it then formed a small swamp thickly set with reeds, which covered an area of several acres, having plenty of water among them. I called this Penny's Creek. Half a mile beyond it was a similar one and reed bed, but no such splendid rock reservoir. Farther along the range other channels issued too, with fine rock water-holes. At eighteen miles we reached a much larger one than we had yet seen: I hoped this might reach the Finke. We followed it into the range, where it came down through a glen: here we found three fine rock-holes with good supplies of water in them. The glen and rock is all red sandstone: the place reminded me somewhat of Captain Sturt's Depot Glen in the Grey ranges of his Central Australian Expedition, only the rock formation is different, though a cliff overhangs both places, and there are other points of resemblance. I named this Stokes's Creek.

We rested here an hour and had a swim in one of the rocky basins. How different to regions westward, where we could not get enough water to drink, let alone to swim in! The water ran down through the glen as far as the rock-holes, where it sank into the ground. Thermometer 102° to-day. We continued along the range, having a fine stretch of open grassy country to travel upon, and in five miles reached another creek, whose reed beds and water filled the whole glen. This I named Bagot's Creek. For some miles no other creek issued, till, approaching the eastern end of the range, we had a piece of broken stony ground and some mulga for a few miles, when we came to a sudden fall into a lower valley, which was again open, grassy, and green. We could then see that the range ended, but sent out one more creek, which meandered down the valley towards some other hills beyond; this valley was of a clayey soil, and the creek had some clay holes with water in them. Following it three miles farther, we found that it emptied itself into a much larger stony mountain stream; I named this Trickett's Creek, after a friend of Mr. Carmichael's. The range which had thrown out so many creeks, and contained so much water, and which is over forty miles in length, I named George Gill's Range, after my brother-in-law. The country round its foot is by far the best I have seen in this region; and could it be transported to any civilised land, its springs, glens, gorges, ferns, Zamias, and flowers, would charm the eyes and hearts of toil-worn men who are condemned to live and die in crowded towns.

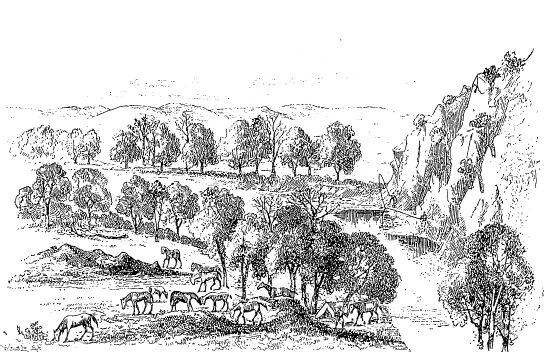

The new creek now just discovered had a large stony water-hole immediately above and below the junction of Trickett's Creek, and as we approached the lower one, I noticed several native wurleys just deserted; their owners having seen us while we only thought of them, had fled at our approach, and left all their valuables behind. These consisted of clubs, spears, shields, drinking vessels, yam sticks, with other and all the usual appliances of well-furnished aboriginal gentlemen's establishments. Three young native dog-puppies came out, however, to welcome us, but when we dismounted and they smelt us, not being used to such refined odours as our garments probably exhaled, they fled howling. The natives had left some food cooking, and when I cooeyed they answered, but would not come near. This creek was of some size; it seemed to pass through a valley in a new range further eastwards. It came from the north-west, apparently draining the northern side of Gill's Range. I called it Petermann's Creek. We were now sixty-five miles from our depot, and had been most successful in our efforts to find a route to allow of the departure of Robinson, as it appeared that this creek would surely reach the Finke, though we afterwards found it did not. I intended upon returning here to endeavour to discover a line of country round the south-eastern extremity of Lake Amadeus, so as to reach Mount Olga at last. We now turned our horses' heads again for our home camp, and continued travelling until we reached Stokes's Creek, where we encamped after a good long day's march.

This morning, as we were approaching Penny's Creek, we saw two natives looking most intently at our outgoing horse tracks, along which they were slowly walking, with their backs towards us. They neither saw nor heard us until we were close upon their heels. Each carried two enormously long spears, two-thirds mulga wood and one-third reed at the throwing end, of course having the instrument with which they project these spears, called by some tribes of natives only, but indiscriminately all over the country by whites, a wommerah. It is in the form of a flat ellipse, elongated to a sort of tail at the holding end, and short-pointed at the projecting end; a kangaroo's claw or wild dog's tooth is firmly fixed by gum and gut-strings. The projectile force of this implement is enormous, and these spears can be thrown with the greatest precision for more than a hundred yards. They also had narrow shields, three to four feet long, to protect themselves from hostile spears, with a handle cut out in the centre. These two natives had their hair tied up in a kind of chignon at the back of the head, the hair being dragged back off the forehead from infancy. This mode gave them a wild though somewhat effeminate appearance; others, again, wear their hair in long thick curls reaching down the shoulders, beautifully elaborated with iguanas' or emus' fat and red ochre. This applies only to the men; the women's hair is worn either cut with flints or bitten off short. So soon as the two natives heard, and then looking round saw us, they scampered off like emus, running along as close to the ground as it is possible for any two-legged creature to do. One was quite a young fellow, the other full grown. They ran up the side of the hills, and kept travelling along parallel to us; but though we stopped and called, and signalled with boughs, they would not come close, and the oftener I tried to come near them on foot, the faster they ran. They continued alongside us until King's Creek was reached, where we rested the horses for an hour. We soon became aware that a number of natives were in our vicinity, our original two yelling and shouting to inform the others of our advent, and presently we saw a whole nation of them coming from the glen or gorge to the south-west, where I had noticed camp-fires on my first arrival here. The new people were also shouting and yelling in the most furious and demoniacal manner; and our former two, as though deputed by the others, now approached us much nearer than before, and came within twenty yards of us, but holding their spears fixed in their wommerahs, in such a position that they could use them instantly if they desired. The slightest incident might have induced them to spear us, but we appeared to be at our ease, and endeavoured to parley with them. The men were not handsome or fat, but were very well made, and, as is the case with most of the natives of these parts, were rather tall, namely five feet eight and nine inches. When they had come close enough, the elder began to harangue us, and evidently desired us to know that we were trespassers, and were to be off forthwith, as he waved us away in the direction we had come from. The whole host then took up the signal, howled, yelled, and waved their hands and weapons at us. Fortunately, however, they did not actually attack us; we were not very well prepared for attack, as we had only a revolver each, our guns and rifles being left with Robinson. As our horses were frightened and would not feed, we hurried our departure, when we were saluted with rounds of cheers and blessings, i.e. yells and curses in their charming dialect, until we were fairly out of sight and hearing. On reaching the camp, Alec reported that no natives had been seen during our absence. On inspecting the two lame horses, it appeared they were worse than ever.

We had a very sudden dry thunderstorm, which cooled the air. Next day I sent Alec and Carmichael over to the first little five-mile creek eastwards with the two lame horses, so that we can pick them up en route to-morrow. They reported that the horses could scarcely travel at all; I thought if I could get them to Penny's Creek I would leave them there. This little depot camp was at length broken up, after it had existed here from 15th October to 5th November. I never expected, after being nearly three months out, that I should be pushing to the eastwards, when every hope and wish I had was to go in exactly the opposite direction, and I could only console myself with the thought that I was going to the east to get to the west at last. I have great hopes that if I can once set my foot upon Mount Olga, my route to the west may be unimpeded. I had not seen all the horses together for some time, and when they were mustered this morning, I found they had all greatly improved in condition, and almost the fattest among them was the little mare that had foaled at Mount Udor. Marzetti's mare looked very well also.

It was past midday when we turned our backs upon Tempe's Vale. At the five-mile creek we got the two lame horses, and reached King's Creek somewhat late in the afternoon. As we neared it, we saw several natives' smokes, and immediately the whole region seemed alive with aborigines, men, women, and children running down from the highest points of the mountain to join the tribe below, where they all congregated. The yelling, howling, shrieking, and gesticulating they kept up was, to say the least, annoying. When we began to unpack the horses, they crowded closer round us, carrying their knotted sticks, long spears, and other fighting implements. I did not notice any boomerangs among them, and I did not request them to send for any. They were growing very troublesome, and evidently meant mischief. I rode towards a mob of them and cracked my whip, which had no effect in dispersing them. They made a sudden pause, and then gave a sudden shout or howl. It seemed as if they knew, or had heard something, of white men's ways, for when I unstrapped my rifle, and holding it up, warning them away, to my great astonishment they departed; they probably wanted to find out if we possessed such things, and I trust they were satisfied, for they gave us up apparently as a bad lot.

It appeared the exertion of travelling had improved the go of the lame horses, so I took them along with the others in the morning; I did not like the idea of leaving them anywhere on this range, as the natives would certainly spear, and probably eat them. We got them along to Stokes's Creek, and encamped at the swimming rock-hole.

After our frugal supper a circumstance occurred which completely put an end to my expedition. Mr. Carmichael informed me that he had made up his mind not to continue in the field any longer, for as Alec Robinson was going away, he should do so too. Of course I could not control him; he was a volunteer, and had contributed towards the expenses of the expedition. We had never fallen out, and I thought he was as ardent in the cause of exploration as I was, so that when he informed me of his resolve it came upon me as a complete surprise. My arguments were all in vain; in vain I showed how, with the stock of provisions we had, we might keep the field for months. I even offered to retreat to the Finke, so that we should not have such arduous work for want of water, but it was all useless.

It was with distress that I lay down on my blankets that night, after what he had said. I scarcely knew what to do. I had yet a lot of horses heavily loaded with provisions; but to take them out into a waterless, desert country by myself, was impossible. We only went a short distance—to Bagot's Creek, where I renewed my arguments. Mr. Carmichael's reply was, that he had made up his mind and nothing should alter it; the consequence was that with one companion I had, so to speak, discharged, and another who discharged himself, any further exploration was out of the question. I had no other object now in view but to hasten my return to civilisation, in hopes of reorganising my expedition. We were now in full retreat for the telegraph line; but as I still traversed a region previously unexplored, I may as well continue my narrative to the close. Marzetti's foal couldn't travel, and had to be killed at Bagot's Creek.

On Friday, the 8th November, the party, now silent, still moved under my directions. We travelled over the same ground that Mr. Carmichael and I had formerly done, until we reached the Petermann in the Levi Range. The natives and their pups had departed. The hills approached this creek so close as to form a valley; there were several water-holes in the creek; we followed its course as far as the valley existed. When the country opened, the creek spread out, and the water ceased to appear in its bed. We kept moving all day; towards evening I saw some gum-trees under some hills two or three miles southwards, and as some smoke appeared above the hills, I knew that natives must have been there lately, and that water might be got there. Accordingly, leaving Carmichael and Robinson to go on with the horses, I rode over, and found there was the channel of a small creek, which narrowed into a kind of glen the farther I penetrated. The grass was burning on all the hillsides, and as I went still farther up, I could hear the voices of the natives, and I felt pretty sure of finding water. I was, however, slightly anxious as to what reception I should get. I soon saw a single native leisurely walking along in front of me with an iguana in his hand, taking it home for supper. He carried several spears, a wommerah, and a shield, and had long curled locks hanging down his shoulders. My horse's nose nearly touched his back before he was aware of my presence, when, looking behind him, he gave a sudden start, held up his two hands, dropped his iguana and his spears, uttered a tremendous yell as a warning to his tribe, and bounded up the rocks in front of us like a wallaby. I then passed under a eucalyptus-tree, in whose foliage two ancient warriors had hastily secreted themselves. I stopped a second and looked up at them, they also looked at me; they presented a most ludicrous appearance. A little farther on there were several rows of wurleys, and I could perceive the men urging the women and children away, as they doubtless supposed many more white men were in company with me, never supposing I could possibly be alone. While the women and children were departing up the rocks, the men snatched up spears and other weapons, and followed the women slowly towards the rocks. The glen had here narrowed to a gorge, the rocks on either side being not more than eighty to a hundred feet high. It is no exaggeration to say that the summits of the rocks on either side of the glen were lined with natives; they could almost touch me with their spears. I did not feel quite at home in this charming retreat, although I was the cynosure of a myriad eyes. The natives stood upon the edge of the rocks like statues, some pointing their spears menacingly towards me, and I certainly expected that some dozens would be thrown at me. Both parties seemed paralysed by the appearance of the other. I scarcely knew what to do; I knew if I turned to retreat that every spear would be launched at me. I was, metaphorically, transfixed to the spot. I thought the only thing to do was to brave the situation out, as

“Cowards, 'tis said, in certain

situations

Derive a sort of courage from despair;

And then perform, from downright desperation,

Much bolder deeds than many a braver man would dare.”

ILLUSTRATION 8

ESCAPE GLEN—THE ADVANCE.

ILLUSTRATION 9

ESCAPE GLEN—THE RETREAT.

ILLUSTRATION 10

MIDDLETON'S PASS AND FISH PONDS.

I was choking with thirst, though in vain I looked for a sheet of water; but seeing where they had dug out some sand, I advanced to one or two wells in which I could see water, but without a shovel only a native could get any out of such a funnel-shaped hole. In sheer desperation I dismounted and picked up a small wooden utensil from one of the wurleys, thinking if I could only get a drink I should summon up pluck for the last desperate plunge. I could only manage to get up a few mouthfuls of dirty water, and my horse was trying to get in on top of me. So far as I could see, there were only two or three of these places where all those natives got water. I remounted my horse, one of the best and fastest I have. He knew exactly what I wanted because he wished it also, and that was to be gone. I mounted slowly with my face to the enemy, but the instant I was on he sprang round and was away with a bound that almost left me behind; then such demoniacal yells greeted my ears as I had never heard before and do not wish to hear again; the echoes of the voices of these now indignant and infuriated creatures reverberating through the defiles of the hills, and the uncouth sounds of the voices themselves smote so discordantly on my own and my horse's ears that we went out of that glen faster, oh! ever so much faster, than we went in. I heard a horrid sound of spears, sticks, and other weapons, striking violently upon the ground behind me, but I did not stop to pick up any of them, or even to look round to see what caused it. Upon rejoining my companions, as we now seldom spoke to one another, I merely told them I had seen water and natives, but that it was hardly worth while to go back to the place, but that they could go if they liked. Robinson asked me why I had ridden my horse West Australian—shortened to W.A., but usually called Guts, from his persistent attention to his “inwards”—so hard when there seemed no likelihood's of our getting any water for the night? I said, “Ride him back and see.” I called this place Escape Glen. In two or three miles after I overtook them, the Petermann became exhausted on the plains. We pushed on nearly east, as now we must strike the Finke in forty-five to fifty miles; but we had to camp that night without water. The lame horses went better the farther they were driven. I hoped to travel the lameness out of them, as instances of that kind have occurred with me more than once. We were away from our dry camp early, and had scarcely proceeded two miles when we struck the bank of a broad sandy-bedded creek, which was almost as broad as the Finke itself: just where we struck it was on top of a red bank twenty or thirty feet high. The horses naturally looking down into the bed below, one steady old file of a horse, that carried my boxes with the instruments, papers, quicksilver, etc., went too close, the bank crumbled under him, and down he fell, raising a cloud of red dust. I rode up immediately, expecting to see a fine smash, but no, there he was, walking along on the sandy bed below, as comfortable as he had been on top, not a strap strained or a box shifted in the least. The bed here was dry. Robinson rode on ahead and shortly found two fine large ponds under a hill which ended abruptly over them. On our side a few low ridges ran to meet it, thus forming a kind of pass. Here we outspanned; it was a splendid place. Carmichael and Robinson caught a great quantity of fish with hook and line. I called these Middleton's Pass and Fish Ponds. The country all round was open, grassy, and fit for stock. The next day we got plenty more fish; they were a species of perch, the largest one caught weighed, I dare say, three pounds; they had a great resemblance to Murray cod, which is a species of perch. I saw from the hill overhanging the water that the creek trended south-east. Going in that direction we did not, however, meet it; so turning more easterly, we sighted some pointed hills, and found the creek went between them, forming another pass, where there was another water-hole under the rocks. This, no doubt, had been of large dimensions, but was now gradually getting filled with sand; there was, however, a considerable quantity of water, and it was literally alive with fish, insomuch that the water had a disagreeable and fishy taste. Great numbers of the dead fish were floating upon the water. Here we met a considerable number of natives, and although the women would not come close, several of the men did, and made themselves useful by holding some of the horses' bridles and getting firewood. Most of them had names given them by their godfathers at their baptism, that is to say, either by the officers or men of the Overland Telegraph Construction parties. This was my thirty-second camp; I called it Rogers's Pass; twenty-two miles was our day's stage. From here two conspicuous semi-conical hills, or as I should say, truncated cones, of almost identical appearance, caught my attention; they bore nearly south 60° east.

ILLUSTRATION 11

JUNCTION OF THE PALMER AND FINKE.

Bidding adieu to our sable friends, who had had breakfast with us and again made themselves useful, we started for the twins. To the south of them was a range of some length; of this the twins formed a part. I called it Seymour's Range, and a conic hill at its western end Mount Ormerod. We passed the twins in eleven miles, and found some water in the creek near a peculiar red sandstone hill, Mount Quin; the general course of the creek was south 70° east. Seymour's Range, together with Mounts Quin and Ormerod, had a series of watermarks in horizontal lines along their face, similar to Johnston's Range, seen when first starting, the two ranges lying east and west of one another; the latter-named range we were again rapidly approaching. Not far from Mount Quin I found some clay water-holes in a lateral channel. The creek now ran nearly east, and having taken my latitude this morning by Aldeberan, I was sure of what I anticipated, namely, that I was running down the creek I had called Number 2. It was one that joined the Finke at my outgoing Number 2 camp. We found a water-hole to-day, fenced in by the natives. There was a low range to the south-west, and a tent-shaped hill more easterly. We rested the horses at the fenced-in water-hole. I walked to the top of the tent hill, and saw the creek went through another pass to the north-east. In the afternoon I rode over to this pass and found some ponds of water on this side of it. A bullock whose tracks I had seen further up the creek had got bogged here. We next travelled through the pass, which I called Briscoe's Pass, the creek now turning up nearly north-east; in six miles further it ran under a hill, which I well remembered in going out; at thirteen miles from the camp it ended in the broader bosom of the Finke, where there was a fine water-hole at the junction, in the bed of the smaller creek, which was called the Palmer. The Finke now appeared very different to when we passed up. It then had a stream of water running along its channel, but was now almost dry, except that water appeared at intervals upon the surface of the white and sandy bed, which, however, was generally either salty or bitter; others, again, were drinkable enough. Upon reaching the river we camped.

My expedition was over. I had failed certainly in my object, which was to penetrate to the sources of the Murchison River, but not through any fault of mine, as I think any impartial reader will admit. Our outgoing tracks were very indistinct, but yet recognisable; we camped again at Number 1. Our next line was nearly east, along the course of the Finke, passing a few miles south of Chambers's Pillar. I had left it but twelve weeks and four days; during that interval I had traversed and laid down over a thousand miles of previously totally unknown country. Had I been fortunate enough to have fallen upon a good or even a fair line of country, the distance I actually travelled would have taken me across the continent.

I may here make a few remarks upon the Finke. It is usually called a river, although its water does not always show upon the surface. Overlanders, i.e. parties travelling up or down the road along the South Australian Trans-Continental Telegraph line, where the water does show on the surface, call them springs. The water is always running underneath the sand, but in certain places it becomes impregnated with mineral and salty formations, which gives the water a disagreeable taste. This peculiar drain no doubt rises in the western portions of the McDonnell Range, not far from where I traced it to, and runs for over 500 miles straight in a general south-westerly direction, finally entering the northern end of Lake Eyre. It drains an enormous area of Central South Australia, and on the parallels of 24, 25, 26° of south latitude, no other stream exists between it and the Murchison or the Ashburton, a distance in either case of nearly 1,100 miles, and thus it will be seen it is the only Central Australian river.

On the 21st of November we reached the telegraph line at the junction of the Finke and the Hugh. The weather during this month, and almost to its close, was much cooler than the preceding one. The horses were divided between us—Robinson getting six, Carmichael four, and I five. Carmichael and Robinson went down the country, in company, in advance of me, as fast as they could. I travelled more slowly by myself. One night, when near what is called the Horse-shoe bend of the Finke, I had turned out my horses, and as it seemed inclined to rain, was erecting a small tent, and on looking round for the tomahawk to drive a stake into the ground, was surprised to notice a very handsome little black boy, about nine or ten years old, quite close to me. I patted him on the head, whereupon he smiled very sweetly, and began to talk most fluently in his own language. I found he interspersed his remarks frequently with the words Larapinta, white fellow, and yarraman (horses). He told me two white men, Carmichael and Robinson, and ten horses, had gone down, and that white fellows, with horses and camel drays (Gosse's expedition), had just gone up the line. While we were talking, two smaller boys came up and were patted, and patted me in return.

The water on the surface here was bitter, and I had not been able to find any good, but these little imps of iniquity took my tin billy, scratched a hole in the sand, and immediately procured delicious water; so I got them to help to water the horses. I asked the elder boy, whom I christened Tommy, if he would come along with me and the yarramans; of these they seemed very fond, as they began kissing while helping to water them. Tommy then found a word or two of English, and said, “You master?” The natives always like to know who they are dealing with, whether a person is a master or a servant. I replied, “Yes, mine master.” He then said, “Mine (him) ridem yarraman.” “Oh, yes.” “Which one?” “That one,” said I, pointing to old Cocky, and said, “That's Cocky.” Then the boy went up to the horse, and said, “Cocky, you ridem me?” Turning to me, he said, “All right, master, you and me Burr-r-r-r-r.” I was very well pleased to think I should get such a nice little fellow so easily. It was now near evening, and knowing that these youngsters couldn't possibly be very far from their fathers or mothers, I asked, “Where black fellow?” Tommy said, quite nonchalantly, “Black fellow come up!” and presently I heard voices, and saw a whole host of men, women, and children. Then these three boys set up a long squeaky harangue to the others, and three or four men and five or six boys came running up to me. One was a middle-aged, good-looking man; with him were two boys, and Tommy gave me to understand that these were his father and brothers. The father drew Tommy towards him, and ranged his three boys in a row, and when I looked at them, it was impossible to doubt their relationship—they were all three so wonderfully alike. Dozens more men, boys, and women came round—some of the girls being exceedingly pretty. To feed so large a host, would have required all my horses as well as my stock of rations, so I singled out Tommy, his two brothers, and the other original little two, at the same time, giving Tommy's father about half a damper I had already cooked, and told him that Tommy was my boy. He shook his head slowly, and would not accept the damper, walking somewhat sorrowfully away. However, I sent it to him by Tommy, and told him to tell his father he was going with me and the horses. The damper was taken that time. It did not rain, and the five youngsters all slept near me, while the tribe encamped a hundred yards away. I was not quite sure whether to expect an attack from such a number of natives. I did not feel quite at ease; though these were, so to say, civilised people, they were known to be great thieves; and I never went out of sight of my belongings, as in many cases the more civilised they are, the more villainous they may be. In the morning Tommy's father seemed to have thought better of my proposal, thinking probably it was a good thing for one of his boys to have a white master. I may say nearly all the civilised youngsters, and a good many old ones too, like to get work, regular rations, and tobacco, from the cattle or telegraph stations, which of course do employ a good many. When one of these is tired of his work, he has to bring up a substitute and inform his employer, and thus a continual change goes on. The boys brought up the horses, and breakfast being eaten, the father led Tommy up to me and put his little hand in mine; at the same time giving me a small piece of stick, and pretending to thrash him; represented to me that, if he didn't behave himself, I was to thrash him. I gave the old fellow some old clothes (Tommy I had already dressed up), also some flour, tea, and sugar, and lifted the child on to old Cocky's saddle, which had a valise in front, with two straps for the monkey to cling on by. A dozen or two youngsters now also wanted to come on foot. I pretended to be very angry, and Tommy must have said something that induced them to remain. I led the horse the boy was riding, and had to drive the other three in front of me. When we departed, the natives gave us some howls or cheers, and finally we got out of their reach. The boy seemed quite delighted with his new situation, and talked away at a great rate. As soon as we reached the road, by some extraordinary chance, all my stock of wax matches, carried by Badger, caught alight; a perfect volcano ensued, and the novel sight of a pack-horse on fire occurred. This sent him mad, and away he and the two other pack-horses flew down the road, over the sandhills, and were out of sight in no time. I told the boy to cling on as I started to gallop after them. He did so for a bit, but slipping on one side, Cocky gave a buck, and sent Tommy flying into some stumps of timber cut down for the passage of the telegraph line, and the boy fell on a stump and broke his arm near the shoulder. I tied my horse up and went to help the child, who screamed and bit at me, and said something about his people killing me. Every time I tried to touch or pacify him it was the same. I did not know what to do, the horses were miles away. I decided to leave the boy where he was, go after the horses, and then return with them to my last night's camp, and give the boy back to his father. When he saw me mount, he howled and yelled, but I gave him to understand what I was going to do and he lay down and cried. I was full of pity for the poor little creature, and I only left him to return. I started away, and not until I had been at full gallop for an hour did I sight the runaway horses. Cocky got away when the accident occurred, and galloped after and found the others, and his advent evidently set them off a second time. Returning to the boy, I saw some smoke, and on approaching close, found a young black fellow also there. He had bound up the child's arm with leaves, and wrapped it up with bits of bark; and when I came he damped it with water from my bag. I then suggested to these two to return; but oh no, the new chap was evidently bound to seek his fortune in London—that is to say, at the Charlotte Waters Station—and he merely remarked, “You, mine, boy, Burr-r-r-r-r, white fellow wurley;” he also said, “Mine, boy, walk, you, yarraman—mine, boy, sleep you wurley, you Burr-r-r-r-r yarraman.” All this meant that they would walk and I might ride, and that they would camp with me at night. Off I went and left them, as I had a good way to go. I rode and they walked to the Charlotte. I got the little boy regular meals at the station; but his arm was still bad, and I don't know if it ever got right. I never saw him again.

At the Charlotte Waters I met Colonel Warburton and his son; they were going into the regions I had just returned from. I gave them all the information they asked, and showed them my map; but they and Gosse's expedition went further up the line to the Alice springs, in the McDonnell Ranges, for a starting-point. I was very kindly received here again, and remained a few days. My old horse Cocky had got bad again, in consequence of his galloping with the packhorses, and I left him behind me at the Charlotte, in charge of Mr. Johnston. On arrival at the Peake, I found that Mr. Bagot had broken his collar-bone by a fall from a horse. I drove him to the Blinman Mine, where we took the coach for Adelaide. At Beltana, before we reached the Blinman Mine, I heard that my former black boy Dick was in that neighbourhood, and Mr. Chandler, whom I had met at the Charlotte Waters, and who was now stationed here, promised to get and keep him for me until I either came or sent for him: this he did. And thus ends the first book of my explorations.