CHAPTER 2.2. FROM 22ND AUGUST TO 10TH SEPTEMBER, 1873.

A poor water supply. Seeds planted. Beautiful country. Ride westward. A chopped log. Magnetic hill. Singular scenery. Snail-shells. Cheering prospect westward. A new chain of hills. A nearer mountain. Vistas of green. Gibson finds water. Turtle backs. Ornamented Troglodytes' caves. Water and emus. Beef-wood-trees. Grassy lawns. Gum creek. Purple vetch. Cold dewy night. Jumbled turtle backs. Tietkens returns. I proceed. Two-storied native huts. Chinese doctrine. A wonderful mountain. Elegant trees. Extraordinary ridge. A garden. Nature imitates her imitator. Wild and strange view. Pool of water. A lonely camp. Between sleeping and waking. Extract from Byron for breakfast. Return for the party. Emus and water. Arrival of Tietkens. A good camp. Tietkens's birthday creek. Ascend the mountain. No signs of water. Gill's range. Flat-topped hill. The Everard range. High mounts westward. Snail shells. Altitude of the mountain. Pretty scenes. Parrot soup. The sentinel. Thermometer 26°. Frost. Lunar rainbow. A charming spot. A pool of water. Cones of the main range. A new pass. Dreams realised. A long glen. Glen Ferdinand. Mount Ferdinand. The Reid. Large creek. Disturb a native nation. Spears hurled. A regular attack. Repulse and return of the enemy. Their appearance. Encounter Creek. Mount Officer. The Currie. The Levinger. Excellent country. Horse-play. Mount Davenport. Small gap. A fairy space. The Fairies' Glen. Day dreams. Thermometer 24°. Ice. Mount Oberon. Titania's spring. Horses bewitched. Glen Watson. Mount Olga in view. The Musgrave range.

Upon inspection this morning we found but a poor supply of water had drained into our tank in the night, and that there was by no means sufficient for the remaining horses; these had no water yesterday. We passed the forenoon in still enlarging the tank, and as soon as a bucketful drained in, it was given to one of the horses. We planted the seeds of a lot of vegetables and trees here, such as Tasmanian blue gum, wattle, melons, pumpkins, cucumbers, maize, etc.; and then Mr. Tietkens and I got our horses and rode to the main hills to the west, in hopes of discovering more water. We started late, and it was dark when we reached the range. The country passed over between it and our encampment, was exceedingly beautiful; hills being thrown up in red ridges of bare rock, with the native fig-tree growing among the rocks, festooning them into infinite groups of beauty, while the ground upon which we rode was a perfect carpet of verdure. We were therefore in high anticipation of finding some waters equivalent to the scene; but as night was advancing, our search had to be delayed until the morrow. The dew was falling fast, the night air was cool, and deliciously laden with the scented exhalations from trees and shrubs and flowers. The odour of almonds was intense, reminding me of the perfumes of the wattle blooms of the southern, eastern, and more fertile portions of this continent. So exquisite was the aroma, that I recalled to my mind Gordon's beautiful lines:—

“In the spring when the wattle gold

trembles,

Twixt shadow and shine,

When each dew-laden air draught resembles;

A long draught of wine.”

So delightful indeed was the evening that it was late when we gave ourselves up to the oblivion of slumber, beneath the cool and starry sky. We made a fire against a log about eighteen inches thick; this was a limb from an adjacent blood-wood or red gum-tree, and this morning we discovered that it had been chopped off its parent stem either with an axe or tomahawk, and carried some forty or fifty yards from where it had originally fallen. This seemed very strange; in the first place for natives, so far out from civilisation as this, to have axes or tomahawks; and in the second place, to chop logs or boughs off a tree was totally against their practice. By sunrise we were upon the summit of the mountain; it consisted of enormous blocks and boulders of red granite, so riven and fissured that no water could possibly lodge upon it for an instant. I found it also to be highly magnetic, there being a great deal of ironstone about the rocks. It turned the compass needle from its true north point to 10° south of west, but the attraction ceased when the compass was removed four feet from contact with the rocks. The view from this mount was of singular and almost awful beauty. The mount, and all the others connected with it, rose simply like islands out of a vast ocean of scrub. The beauty of the locality lay entirely within itself. Innumerable red ridges ornamented with fig-trees, rising out of green and grassy slopes, met the eye everywhere to the east, north, and northeast, and the country between each was just sufficiently timbered to add a charm to the view. But the appearance of water still was wanting; no signs of it, or of any basin or hollow that could hold it, met the gaze in any direction, This alone was wanting to turn a wilderness into a garden.

There were four large mounts in this chain, higher than any of the rest, including the one I was on. Here we saw a quantity of what I at first thought were white sea-shells, but we found they were the bleached shells of land snails. Far away to the north some ranges appeared above the dense ocean of intervening scrubs. To the south, scrubs reigned supreme; but to the west, the region for which I was bound, the prospect looked far more cheering. The far horizon, there, was bounded by a very long and apparently connected chain of considerable elevation, seventy to eighty miles away. One conspicuous mountain, evidently nearer than the longer chain, bore 15° to the south of west, while an apparent gap or notch in the more distant line bore 23° south of west. The intervening country appeared all flat, and very much more open than in any other direction; I could discern long vistas of green grass, dotted with yellow immortelles, but as the perspective declined, these all became lost in lightly timbered country. These grassy glades were fair to see, reminding one somewhat of Merrie England's glades and Sherwood forests green, where errant knight in olden days rode forth in mailed sheen; and memory oft, the golden rover, recalls the tales of old romance, how ladie bright unto her lover, some young knight, smitten with her glance, would point out some heroic labour, some unheard-of deed of fame; he must carve out with his sabre, and ennoble thus his name. He, a giant must defeat sure, he must free the land from tain, he must kill some monstrous creature, or return not till 'twas slain. Then she'd smile on him victorious, call him the bravest in the land, fame and her, to win, how glorious—win and keep her heart and hand!

Although no water was found here, what it pleases me to call my mind was immediately made up. I would return at once to the camp, where water was so scarce, and trust all to the newly discovered chain to the west. Water must surely exist there, we had but to reach it. I named these mounts Ayers Range. Upon returning to our camp, six or seven miles off, I saw that a mere dribble of water remained in the tank. Gibson was away after the horses, and when he brought them, he informed me he had found another place, with some water lying on the rocks, and two native wells close by with water in them, much shallower than our present one, and that they were about three miles away. I rode off with him to inspect his new discovery, and saw there was sufficient surface water for our horses for a day or two.

These rocks are most singular, being mostly huge red, rounded solid blocks of stone, shaped like the backs of enormous turtles. I was much pleased with Gibson's discovery, and we moved the camp down to this spot, which we always after called the Turtle Back. The grass and herbage were excellent, but the horses had not had sufficient water since we arrived here. It is wonderful how in such a rocky region so little water appears to exist. The surface water was rather difficult for the horses to reach, as it lay upon the extreme summit of the rock, the sides of which were very steep and slippery. There were plenty of small birds; hawks and crows, a species of cockatoo, some pigeons, and eagles soaring high above. More seeds were planted here, the soil being very good. Upon the opposite or eastern side of this rock was a large ledge or cave, under which the Troglodytes of these realms had frequently encamped. It was ornamented with many of their rude representations of creeping things, amongst which the serpent class predominated; there were also other hideous shapes, of things such as can exist only in their imaginations, and they are but the weak endeavours of these benighted beings to give form and semblance to the symbolisms of the dread superstitions, that, haunting the vacant chambers of their darkened minds, pass amongst them in the place of either philosophy or religion.

Next morning, watering all our horses, and having a fine open-air bath on the top of the Turtle Back, Mr. Tietkens and I got three of them and again started for Ayers Range, nearly west. Reaching it, we travelled upon the bearing of the gap which we had seen in the most distant range. The country as we proceeded we found splendidly open, beautifully grassed, and it rose occasionally into some low ridges. At fifteen miles from the Turtle Back we found some clay-pans with water, where we turned out our horses for an hour. A mob of emus came to inspect us, and Mr. Tietkens shot one in a fleshy part of the neck, which rather helped it to run away at full speed instead of detaining, so that we might capture it. Next some parallel ridges lying north and south were crossed, where some beefwood, or Grevillea trees, ornamented the scene, the country again opening into beautiful grassy lawns. One or two creek channels were crossed, and a larger one farther on, whose timber indeed would scarcely reach our course; as it would not come to us, we went to it. The gum-timber upon it was thick and vigorous—it came from the north-westward. A quantity of the so called tea-tree [Melaleuca] grew here. In two miles up the channel we found where a low ridge crossed and formed a kind of low pass. An old native well existed here, which, upon cleaning out with a quart pot, disclosed the element of our search to our view at a depth of nearly five feet. The natives always make these wells of such an abominable shape, that of a funnel, never thinking how awkward they must be to white men with horses—some people are so unfeeling! It took us a long time to water our three horses. There was a quantity of the little purple vetch here, of which all animals are so fond, and which is so fattening. There was plenty of this herb at the Turtle Back, and wherever it grows it gives the country a lovely carnation tinge; this, blending with the bright green of the grass, and the yellow and other tinted hues of several kinds of flowers, impresses on the whole region the appearance of a garden.

In the morning, in consequence of a cold and dewy night, the horses declined to drink. Regaining our yesterday's course, we continued for ten miles, when we noticed that the nearest mountain seen from Ayers Range was now not more than thirty miles away. It appeared red, bald, and of some altitude; to our left was another mass of jumbled turtle backs, and we turned to search for water among them. A small gum creek to the south-south-east was first visited and left in disgust, and all the rocks and hills we searched, were equally destitute of water. We wasted the rest of the day in fruitless search; Nature seemed to have made no effort whatever to form any such thing as a rockhole, and we saw no place where the natives had ever even dug. We had been riding from morning until night, and we had neither found water nor reached the mountain. We returned to our last night's camp, where the sand had all fallen into the well, and we had our last night's performance with the quart pot to do over again.

In the morning I decided to send Mr. Tietkens back to the camp to bring the party here, while I went to the mountain to search for water. We now discovered we had brought but a poor supply of food, and that a hearty supper would demolish the lot, so we had to be sadly economical. When we got our horses the next morning we departed, each on his separate errand—Mr. Tietkens for the camp, I for the mountain. I made a straight course for it, and in three or four miles found the country exceedingly scrubby. At ten miles I came upon a number of native huts, which were of large dimensions and two-storied; by this I mean they had an upper attic, or cupboard recess. When the natives return to these, I suppose they know of some water, or else get it out of the roots of trees. The scrubs became thicker and thicker, and only at intervals could the mountain be seen. At a spot where the natives had burnt the old grass, and where some new rich vegetation grew, I gave my horse the benefit of an hour's rest, for he had come twenty-two miles. The day was delightful; the thermometer registered only 76° in the shade. I had had a very poor breakfast, and now had an excellent appetite for all the dinner I could command, and I could not help thinking that there is a great deal of sound philosophy in the Chinese doctrine, That the seat of the mind and the intellect is situate in the stomach.

Starting again and gaining a rise in the dense ocean of scrub, I got a sight of the mountain, whose appearance was most wonderful; it seemed so rifted and riven, and had acres of bare red rock without a shrub or tree upon it. I next found myself under the shadow of a huge rock towering above me amidst the scrubs, but too hidden to perceive until I reached it. On ascending it I was much pleased to discover, at a mile and a half off, the gum timber of a creek which meandered through this wilderness. On gaining its banks I was disappointed to find that its channel was very flat and poorly defined, though the timber upon it was splendid. Elegant upright creamy stems supported their umbrageous tops, whose roots must surely extend downwards to a moistened soil. On each bank of the creek was a strip of green and open ground, so richly grassed and so beautifully bedecked with flowers that it seemed like suddenly escaping from purgatory into paradise when emerging from the recesses of the scrubs on to the banks of this beautiful, I wish I might call it, stream.

Opposite to where I struck it stood an extraordinary hill or ridge, consisting of a huge red turtle back having a number of enormous red stones almost egg-shaped, traversing, or rather standing in a row upon, its whole length like a line of elliptical Tors. I could compare it to nothing else than an enormous oolitic monster of the turtle kind carrying its eggs upon its back. A few cypress pine-trees grew in the interstices of the rocks, giving it a most elegant appearance. Hoping to find some rock or other reservoir of water, I rode over to this creature, or feature. Before reaching its foot, I came upon a small piece of open, firm, grassy ground, most beautifully variegated with many-coloured vegetation, with a small bare piece of ground in the centre, with rain water lying on it. The place was so exquisitely lovely it seemed as if only rustic garden seats were wanting, to prove that it had been laid out by the hand of man. But it was only an instance of one of Nature's freaks, in which she had so successfully imitated her imitator, Art. I watered my horse and left him to graze on this delectable spot, while I climbed the oolitic's back. There was not sufficient water in the garden for all my horses, and it was actually necessary for me to find more, or else the region would be untenable.

The view from this hill was wild and strange; the high, bald forehead of the mountain was still four or five miles away, the country between being all scrub. The creek came from the south-westward, and was lost in the scrubs to the east of north. A thick and vigorous clump of eucalypts down the creek induced me first to visit them, but the channel was hopelessly dry. Returning, I next went up the creek, and came to a place where great boulders of stone crossed the bed, and where several large-sized holes existed, but were now dry. Hard by, however, I found a damp spot, and near it in the sand a native well, not more than two feet deep, and having water in it. Still farther up I found an overhanging rock, with a good pool of water at its foot, and I was now satisfied with my day's work. Here I camped. I made a fire at a large log lying in the creek bed; my horse was up to his eyes in most magnificent herbage, and I could not help envying him as I watched him devouring his food. I felt somewhat lonely, and cogitated that what has been written or said by cynics, solitaries, or Byrons, of the delights of loneliness, has no real home in the human heart. Nothing could appal the mind so much as the contemplation of eternal solitude. Well may another kind of poet exclaim, Oh, solitude! where are the charms that sages have seen in thy face? for human sympathy is one of the passions of human nature. Natives had been here very recently, and the scrubs were burning, not far off to the northwards, in the neighbourhood of the creek channel. As night descended, I lay me down by my bright camp fire in peace to sleep, though doubtless there are very many of my readers who would scarcely like to do the same. Such a situation might naturally lead one to consider how many people have lain similarly down at night, in fancied security, to be awakened only by the enemies' tomahawk crashing through their skulls. Such thoughts, if they intruded themselves upon my mind, were expelled by others that wandered away to different scenes and distant friends, for this Childe Harold also had a mother not forgot, and sisters whom he loved, but saw them not, ere yet his weary pilgrimage begun.

Dreams also, between sleeping and waking, passed swiftly through my brain, and in my lonely sleep I had real dreams, sweet, fanciful, and bright, mostly connected with the enterprise upon which I had embarked—dreams that I had wandered into, and was passing through, tracts of fabulously lovely glades, with groves and grottos green, watered by never-failing streams of crystal, dotted with clusters of magnificent palm-trees, and having groves, charming groves, of the fairest of pines, of groves “whose rich trees wept odorous gums and balm.”

“And all throughout the night there reigned

the sense

Of waking dream, with luscious thoughts o'erladen;

Of joy too conscious made, and too intense,

By the swift advent of this longed-for aidenn.”

On awaking, however, I was forced to reflect, how “mysterious are these laws! The vision's finer than the view: her landscape Nature never draws so fair as fancy drew.” The morning was cold, the thermometer stood at 28°, and now—

“The morn was up again, the dewy morn;

With breath all incense, and with cheek all bloom,

Laughing the clouds away with playful scorn,

And smiling, as if earth contained no tomb:

And glowing into day.”

With this charming extract from Byron for breakfast I saddled my horse, having nothing more to detain me here, intending to bring up the whole party as soon as possible.

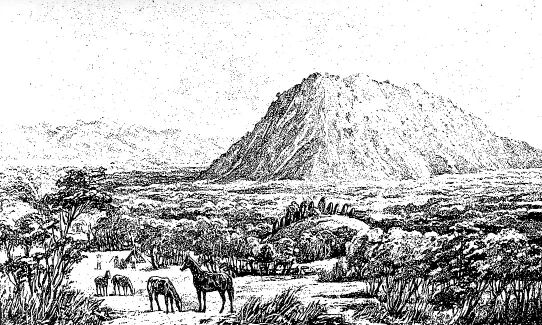

ILLUSTRATION 13

TIETKEN'S BIRTHDAY CREEK AND MOUNT CARNARVON.

ILLUSTRATION 14

ON BIRTHDAY CREEK.

I now, however, returned by a more southerly route, and found the scrubs less thick, and came to some low red rises in them. Having travelled east, I now turned on the bearing for the tea-tree creek, where the party ought now to be. At six miles on this line I came upon some open ground, and saw several emus. This induced me to look around for water, and I found some clay-pans with enough water to last a week. I was very well pleased, as this would save time and trouble in digging at the tea-tree. The water here was certainly rather thick, and scarcely fit for human organisms, at least for white ones, though it might suit black ones well enough, and it was good enough for our horses, which was the greatest consideration. I rested my horse here for an hour, and then rode to the tea-tree. The party, however, were not there, and I waited in expectation of their arrival. In about an hour Mr. Tietkens came and informed me that on his return to the camp the other day he had found a nice little water, six miles from here, and where the party was, and to which we now rode together. At this agreeable little spot were the three essentials for an explorer's camp—that is to say, wood, water, and grass. From there we went to my clay pans, and the next day to my lonely camp of dreams. This, the 30th August, was an auspicious day in our travels, it being no less than Mr. Tietkens's nine-and-twentieth birthday. We celebrated it with what honours the expedition stores would afford, obtaining a flat bottle of spirits from the medical department, with which we drank to his health and many happier returns of the day. In honour of the occasion I called this Tietkens's Birthday Creek, and hereby proclaim it unto the nations that such should be its name for ever. The camp was not moved, but Mr. Tietkens and I rode over to the high mountain to-day, taking with us all the apparatus necessary for so great an ascent—that is to say, thermometer, barometer, compass, field glasses, quart pot, waterbag, and matches. In about four miles we reached its foot, and found its sides so bare and steep that I took off my boots for the ascent. It was formed for the most part like a stupendous turtle back, of a conglomerate granite, with no signs of water, or any places that would retain it for a moment, round or near its base. Upon reaching its summit, the view was most extensive in every direction except the west, and though the horizon was bounded in all directions by ranges, yet scrubs filled the entire spaces between. To the north lay a long and very distant range, which I thought might be the Gill's Range of my last expedition, though it would certainly be a stretch either of imagination or vision, for that range was nearly 140 miles away.

To the north-westward was a flat-topped hill, rising like a table from an ocean of scrub; it was very much higher than such hills usually are. This was Mount Conner. To the south, and at a considerable distance away, lay another range of some length, apparently also of considerable altitude. I called this the Everard Range. The horizon westward was bounded by a continuous mass of hills or mountains, from the centre of which Birthday Creek seemed to issue. Many of the mounts westward appeared of considerable elevation. The natives were burning the scrubs west and north-west. On the bare rocks of this mountain we saw several white, bleached snail-shells. I was grieved to find that my barometer had met with an accident in our climb; however, by testing the boiling point of water I obtained the altitude.

Water boiled at 206°, giving an elevation of 3085 feet above the level of the sea, it being about 1200 feet above the surrounding country. The view of Birthday Creek winding along in little bends through the scrubs from its parent mountains, was most pleasing. Down below us were some very pretty little scenes. One was a small sandy channel, like a plough furrow, with a few eucalyptus trees upon it, running from a ravine near the foot of this mount, which passed at about a mile through two red mounds of rock, only just wide enough apart to admit of its passage. A few cypress pines were growing close to the little gorge. On any other part of the earth's surface, if, indeed, such another place could be found, water must certainly exist also, but here there was none. We had a perfect bird's-eye view of the spot. We could only hope, for beauty and natural harmony's sake, that water must exist, at least below the surface, if not above. Having completed our survey, we descended barefooted as before.

On reaching the camp, Gibson and Jimmy had shot some parrots and other birds, which must have flown down the barrels of their guns, otherwise they never could have hit them, and we had an excellent supper of parrot soup. Just here we have only seen parrots, magpies and a few pigeons, though plenty of kangaroo, wallaby, and emu; but have not succeeded in bagging any of the latter game, as they are exceedingly shy and difficult to approach, from being so continually hunted by the natives. I named this very singular feature Mount Carnarvon, or The Sentinel, as soon I found

“The mountain there did stand

T sentinel enchanted land.”

The night was cold; mercury down to 26°. What little dew fell became frosted; there was not sufficient to call it frozen. I found my position here to be in latitude 26° 3´, longitude 132° 29´.

In the night of the 1st September, heavy clouds were flying fastly over us, and a few drops of rain fell at intervals. About ten o'clock p.m. I observed a lunar rainbow in the northern horizon; its diameter was only about fifteen degrees. There were no prismatic colours visible about it. To-day was clear, fine, but rather windy. We travelled up the creek, skirting its banks, but cutting off the bends. We had low ridges on our right. The creek came for some distance from the south-west, then more southerly, then at ten miles, more directly from the hills to the west. The country along its banks was excellent, and the scenery most beautiful—pine-clad, red, and rocky hills being scattered about in various directions, while further to the west and south-west the high, bold, and very rugged chain rose into peaks and points. We only travelled sixteen miles, and encamped close to a pretty little pine-clad hill, on the north bank of the creek, where some rocks traversed the bed, and we easily obtained a good supply of water. The grass and herbage being magnificent, the horses were in a fine way to enjoy themselves.

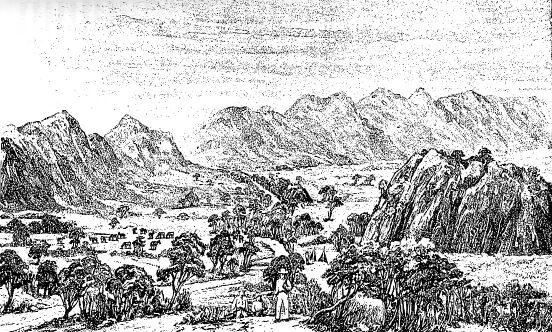

This spot is one of the most charming that even imagination could paint. In the background were the high and pointed peaks of the main chain, from which sloped a delightful green valley; through this the creek meandered, here and there winding round the foot of little pine-clad hills of unvarying red colour, whilst the earth from which they sprung was covered with a carpet of verdure and vegetation of almost every imaginable hue. It was happiness to lie at ease upon such a carpet and gaze upon such a scene, and it was happiness the more ecstatic to know that I was the first of a civilised race of men who had ever beheld it. My visions of a former night really seemed to be prophetic. The trend of the creek, and the valley down which it came, was about 25° south of west. We soon found it became contracted by impinging hills. At ten miles from camp we found a pool of water in the bed. In about a couple of miles farther, to my surprise I found we had reached its head and its source, which was the drainage of a big hill. There was no more water and no rock-holes, neither was there any gorge. Some triodia grew on the hills, but none on the lower ground. The valley now changed into a charming amphitheatre. We had thus traced our Birthday Creek, to its own birthplace. It has a short course, but a merry one, and had ended for us at its proper beginning. As there appeared to be no water in the amphitheatre, we returned to the pool we had seen in the creek. Several small branch creeks running through pretty little valleys joined our creek to-day. We were now near some of the higher cones of the main chain, and could see that they were all entirely timberless, and that triodia grew upon their sides. The spot we were now encamped upon was another scene of exquisite sylvan beauty. We had now been a month in the field, as to-morrow was the 4th of September, and I could certainly congratulate myself upon the result of my first month's labour.

The night was cold and windy, dense nimbus clouds hovered just above the mountain peaks, and threatened a heavy downpour of rain, but the driving gale scattered them into the gelid regions of space, and after sunrise we had a perfectly clear sky. I intended this morning to push through what seemed now, as it had always seemed from the first moment I saw this range, a main gap through the chain. Going north round a pointed hill, we were soon in the trend of the pass; in five miles we reached the banks of a new creek, running westerly into another, or else into a large eucalyptus flat or swamp, which had no apparent outlet. This heavy timber could be seen for two or three miles. Advancing still further, I soon discovered that we were upon the reedy banks of a fast flowing stream, whose murmuring waters, ever rushing idly and unheeded on, were now for the first time disclosed to the delighted eyes of their discoverer.

Here I had found a spot where Nature truly had

“Shed o'er the scene her purest of crystal, her brightest of green.”

This was really a delightful discovery. Everything was of the best kind here—timber, water, grass, and mountains. In all my wanderings, over thousands of miles in Australia, I never saw a more delightful and fanciful region than this, and one indeed where a white man might live and be happy. My dreams of a former night were of a verity realised.

Geographically speaking, we had suddenly come almost upon the extreme head of a large water course. Its trend here was nearly south, and I found it now ran through a long glen in that direction.

We saw several fine pools and ponds, where the reeds opened in the channel, and we flushed up and shot several lots of ducks. This creek and glen I have named respectively the Ferdinand and Glen Ferdinand, after the Christian name of Baron von Mueller. (The names having a star * against them in this book denote contributors to the fund raised by Baron Mueller* for this expedition.—E.G.) The glen extended nearly five miles, and where it ended, the water ceased to show upon the surface. At the end of the glen we encamped, and I do not remember any day's work during my life which gave me more pleasure than this, for I trust it will be believed that:—

“The proud desire of sowing broad the germs

of lasting worth

Shall challenge give to scornful laugh of careless sons of

earth;

Though mirth deride, the pilgrim feet that tread the desert

plain,

The thought that cheers me onward is, I have not lived in

vain.”

After our dinner Mr. Tietkens and I ascended the highest mountain in the neighbourhood—several others not far away were higher, but this was the most convenient. Water boiled at its summit at 204°, which gives an altitude above sea level of 4131 feet, it being about 1500 feet above the surrounding country. I called this Mount Ferdinand, and another higher point nearly west of it I called Mount James-Winter*. The view all round from west to north was shut out. To the south and south-east other ranges existed. The timber of the Ferdinand could be traced for many miles in a southerly direction; it finally became lost in the distance in a timbered if not a scrubby country. This mountain was highly magnetic. I am surprised at seeing so few signs of natives in this region. We returned to the camp and sowed seeds of many cereals, fodder plants, and vegetables. A great quantity of tea-tree grew in this glen. The water was pure and fresh.

Two or three miles farther down, the creek passed between two hills; the configuration of the mountains now compelled me to take a south-westerly valley for my road. In a few miles another fine creek-channel came out of the range to the north of us, near the foot of Mount James-Winter; it soon joined a larger one, up which was plenty of running water; this I called the Reid*. We were now traversing another very pretty valley running nearly west, with fine cotton and salt-bush flats, while picturesque cypress pines covered the hills on both sides of us. Under some hills which obstructed our course was another creek, where we encamped, the grass and herbage being most excellent; and this also was a very pretty place. Our latitude here was 26° 24´.

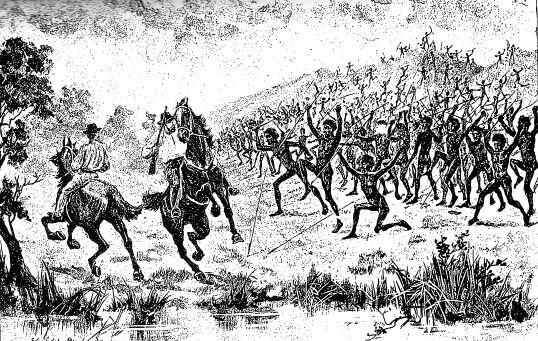

ILLUSTRATION 15

ENCOUNTER WITH THE NATIVES AT “THE OFFICER,” MUSGRAVE RANGE.

Gibson went away on horseback this morning to find the others, but came back on foot to say he had lost the one he started with. We eventually got them all, and proceeded down the creek south, then through a little gap west, on to the banks of a fine large creek with excellent timber on it. The natives were burning the grass up the channel north-westerly. Mr. Tietkens and I rode up in advance to reconnoitre; we went nearly three miles, when we came to running water. At the same time we evidently disturbed a considerable number of natives, who raised a most frightful outcry at our sudden and unexpected advent amongst them. Those nearest to us walked slowly into the reeds, rushes, tea-trees, and high salt bushes, but deliberately watching our every movement. While watering our horses a great many from the outskirts ran at us, poising and quivering their spears, some of which were over ten feet long; of these, every individual had an extraordinary number. When they saw us sitting quietly, but not comfortably, on our horses, which became very frightened and impatient, they renewed their horrible yells and gesticulations, some waving us away, others climbing trees, and directing their spears at us from the branches. Another lot on the opposite side of the creek now came rushing up with spears advanced and ensigns spread, and with their yells and cries encouraged those near to spear us. They seemed, however, to have some doubts of the nature or vulnerability of our horses. At the head of our new assailants was one sophisticated enough to be able to call out, “Walk, white fellow, walk;” but as we still remained immobile, he induced some others to join in making a rush at us, and they hurled their jagged spears at us before we could get out of the way. It was fortunate indeed that we were at the extreme distance that these weapons can be projected, for they struck the ground right amongst our horses' hoofs, making them more restive than ever.

I now let our assailants see we were not quite so helpless as they might have supposed. I unslipped my rifle, and the bullet, going so suddenly between two of these worthies and smashing some boughs just behind them, produced silence amongst the whole congregation, at least for a moment. All this time we were anxiously awaiting the arrival of Gibson and Jimmy, as my instructions were that if we did not return in a given time, they were to follow after us. But these valiant retainers, who admitted they heard the firing, preferred to remain out of harm's way, leaving us to kill or be killed, as the fortunes of war might determine; and we at length had to retreat from our sable enemies, and go and find our white friends. We got the mob of horses up, but the yelling of these fiends in human form, the clouds of smoke from the burning grass and bushes, and the many disagreeable odours incident to a large native village, and the yapping and howling of a lot of starving dogs, all combined to make us and our horses exceedingly restless. They seemed somewhat overawed by the number of the horses, and though they crowded round from all directions, for there were more than 200 of them, the women and children being sent away over the hills at our first approach, they did not then throw any more spears. I selected as open a piece of ground as I could get for the camp, which, however, was very small, back from the water, and nearly under the foot of a hill. When they saw us dismount, for I believe they had previously believed ourselves and our horses to form one animal, and begin to unload the horses, they proceeded properly to work themselves up for a regular onslaught. So long as the horses remained close, they seemed disinclined to attack, but when they were hobbled and went away, the enemy made a grand sortie, rushing down the hill at the back of the camp where they had congregated, towards us in a body with spears fitted in pose and yelling their war cries.

Our lives were in imminent danger; we had out all the firearms we could muster; these amounted to two rifles, two shot guns, and five revolvers. I watched with great keenness the motion of their arms that gives the propulsion to their spears, and the instant I observed that, I ordered a discharge of the two rifles and one gun, as it was no use waiting to be speared first. I delayed almost a second too long, for at the instant I gave the word several spears had left the enemy's hands, and it was with great good fortune we avoided them. Our shots, as I had ordered, cut up the ground at their feet, and sent the sand and gravel into their eyes and faces; this and the noise of the discharge made the great body of them pause. Availing ourselves of this interval, we ran to attack them, firing our revolvers in quick succession as we ran. This, with the noise and the to them extraordinary phenomenon of a projectile approaching them which they could not see, drove them up into the hills from which they had approached us, and they were quiet for nearly an hour, except for their unceasing howls and yells, during which time we made an attempt at getting some dinner. That meal, however, was not completed when we saw them stealing down on us again. Again they came more than a hundred strong, with heads held back, and arms at fullest tension to give their spears the greatest projective force, when, just as they came within spear shot, for we knew the exact distance now, we gave them another volley, striking the sand up just before their feet; again they halted, consulting one another by looks and signs, when the discharge of Gibson's gun, with two long-distance cartridges, decided them, and they ran back, but only to come again. In consequence of our not shooting any of them, they began to jeer and laugh at us, slapping their backsides at and jumping about in front of us, and indecently daring and deriding us. These were evidently some of those lewd fellows of the baser sort (Acts 17 5). We were at length compelled to send some rifle bullets into such close proximity to some of their limbs that at last they really did believe we were dangerous folk after all. Towards night their attentions ceased, and though they camped just on the opposite side of the creek, they did not trouble us any more. Of course we kept a pretty sharp watch during the night. The men of this nation were tall, big, and exceedingly hirsute, and in excellent bodily condition. They reminded me of, as no doubt they are, the prototypes of the account given by the natives of the Charlotte Waters telegraph station, on my first expedition, who declared that out to the west were tribes of wild blacks who were cannibals, who were covered with hair, and had long manes hanging down their backs.

None of these men, who perhaps were only the warriors of the tribe, were either old or grey-haired, and although their features in general were not handsome, some of the younger ones' faces were prepossessing. Some of them wore the chignon, and others long curls; the youngest ones who wore curls looked at a distance like women. A number were painted with red ochre, and some were in full war costume, with feathered crowns and head dresses, armlets and anklets of feathers, and having alternate stripes of red and white upon the upper portions of their bodies; the majority of course were in undress uniform. I knew as soon as I arrived in this region that it must be well if not densely populated, for it is next to impossible in Australia for an explorer to discover excellent and well-watered regions without coming into deadly conflict with the aboriginal inhabitants. The aborigines are always the aggressors, but then the white man is a trespasser in the first instance, which is a cause sufficient for any atrocity to be committed upon him. I named this Encounter Creek The Officer.* There was a high mount to the north-east from here, which lay nearly west from Mount James-Winter, which I called Mount Officer.*

Though there was a sound of revelry or devilry by night in the enemy's camp, ours was not passed in music, and we could not therefore listen to the low harmonics that undertone sweet music's roll. Gibson got one of the horses which was in sight, to go and find the others, while Mr. Tietkens took Jimmy with him to the top of a hill in order to take some bearings for me, while I remained at the camp. No sooner did the natives see me alone than they recommenced their malpractices. I had my arsenal in pretty good fighting order, and determined, if they persisted in attacking me, to let some of them know the consequences. I was afraid that some might spear me from behind while others engaged me in front. I therefore had to be doubly on the alert. A mob of them came, and I fired in the air, then on the ground, at one side of them and then at the other. At last they fell back, and when the others and the horses appeared, though they kept close round us, watching every movement, yelling perpetually, they desisted from further attack. I was very gratified to think afterwards that no blood had been shed, and that we had got rid of our enemies with only the loss of a little ammunition. Although this was Sunday, I did not feel quite so safe as if I were in a church or chapel, and I determined not to remain. The horses were frightened at the incessant and discordant yells and shrieks of these fiends, and our ears also were perfectly deafened with their outcries.

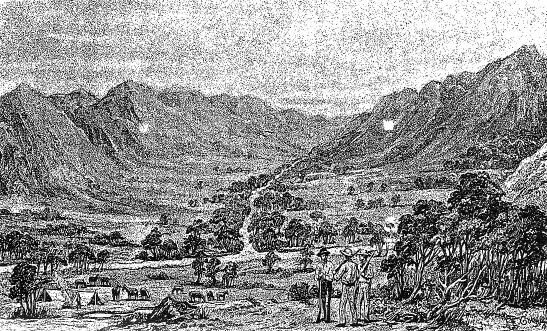

We departed, leaving the aboriginal owners of this splendid piece of land in the peaceful possession of their beautiful hunting grounds, and travelled west through a small gap into a fine valley. The main range continued stretching away north of us in high and heavy masses of hills, and with a fine open country to the south. At ten miles we came to another fine creek, where I found water running; this I called the Currie*. It was late when, in six miles further, we reached another creek, where we got water and a delightful camp. I called this the Levinger*. The country to-day was excellent, being fine open, grassy valleys all the way; all along our route in this range we saw great quantities of white snail-shells, in heaps, at old native encampments, and generally close to their fireplaces. In crevices and under rocks we found plenty of the living snails, large and brown; it was evident the natives cook and eat them, the shells turning white in the fire, also by exposure to the sun. On starting again we travelled about west-north-west, and we passed through a piece of timbered country; at twelve miles we arrived at another fine watercourse. The horses were almost unmanageable with flashness, running about with their mouths full of the rich herbage, kicking up their heels and biting at one another, in a perfect state of horse-play. It was almost laughable to see them, with such heavy packs on their backs, attempting such elephantine gambols; so I kept them going, to steady them a bit. The creek here I called Winter* Water. At five miles farther we passed a very high mountain in the range, which appeared the highest I had seen; I named it Mount Davenport. We next passed through a small gap, over a low hill, and immediately on our appearance we heard the yells and outcries of natives down on a small flat below. All we saw, however, was a small, and I hope happy, family, consisting of two men, one woman, and another youthful individual, but whether male or female I was not sufficiently near to determine. When they saw us descend from the little hill, they very quickly walked away, like respectable people. Continuing our course in nearly the same direction, west-north-west, and passing two little creeks, I climbed a small hill and saw a most beautiful valley about a mile away, stretching north-west, with eucalyptus or gum timber up at the head of it. The valley appeared entirely enclosed by hills, and was a most enticing sight. Travelling on through 200 or 300 yards of mulga, we came out on the open ground, which was really a sight that would delight the eyes of a traveller, even in the Province of Cashmere or any other region of the earth. The ground was covered with a rich carpet of grass and herbage; conspicuous amongst the latter was an abundance of the little purple vetch, which, spreading over thousands of acres of ground, gave a lovely pink or magenta tinge to the whole scene. I also saw that there was another valley running nearly north, with another creek meandering through it, apparently joining the one first seen.

ILLUSTRATION 16

THE FAIRIES' GLEN.

Passing across this fairy space, I noticed the whitish appearances that usually accompany springs and flood-marks in this region. We soon reached a most splendid kind of stone trough, under a little stony bank, which formed an excellent spring, running into and filling the little trough, running out at the lower end, disappearing below the surface, evidently perfectly satisfied with the duties it had to perform.

This was really the most delightful spot I ever saw; a region like a garden, with springs of the purest water spouting out of the ground, ever flowing into a charming little basin a hundred yards long by twenty feet wide and four feet deep. There was a quantity of the tea-tree bush growing along the various channels, which all contained running water.

The valley is surrounded by picturesque hills, and I am certain it is the most charming and romantic spot I ever shall behold. I immediately christened it the Fairies' Glen, for it had all the characteristics to my mind of fairyland. Here we encamped. I would not have missed finding such a spot, upon—I will not say what consideration. Here also of course we saw numbers of both ancient and modern native huts, and this is no doubt an old-established and favourite camping ground. And how could it be otherwise? No creatures of the human race could view these scenes with apathy or dislike, nor would any sentient beings part with such a patrimony at any price but that of their blood. But the great Designer of the universe, in the long past periods of creation, permitted a fiat to be recorded, that the beings whom it was His pleasure in the first instance to place amidst these lovely scenes, must eventually be swept from the face of the earth by others more intellectual, more dearly beloved and gifted than they. Progressive improvement is undoubtedly the order of creation, and we perhaps in our turn may be as ruthlessly driven from the earth by another race of yet unknown beings, of an order infinitely higher, infinitely more beloved, than we. On me, perchance, the eternal obloquy of the execution of God's doom may rest, for being the first to lead the way, with prying eye and trespassing foot, into regions so fair and so remote; but being guiltless alike in act or intention to shed the blood of any human creature, I must accept it without a sigh.

The night here was cold, the mercury at daylight being down to 24°, and there was ice on the water or tea left in the pannikins or billies overnight.

This place was so charming that I could not tear myself away. Mr. Tietkens and I walked to and climbed up a high mount, about three miles north-easterly from camp; it was of some elevation. We ascended by a gorge having eucalyptus and callitris pines halfway up. We found water running from one little basin to another, and high up, near the summit, was a bare rock over which water was gushing. To us, as we climbed towards it, it appeared like a monstrous diamond hung in mid-air, flashing back the rays of the morning sun. I called this Mount Oberon, after Shakespeare's King of the Fairies. The view from its summit was limited. To the west the hills of this chain still run on; to the east I could see Mount Ferdinand. The valley in which the camp and water was situate lay in all its loveliness at our feet, and the little natural trough in its centre, now reduced in size by distance, looked like a silver thread, or, indeed, it appeared more as though Titania, the Queen of the Fairies, had for a moment laid her magic silver wand upon the grass, and was reposing in the sunlight among the herbage and the flowers. The day was lovely, the sky serene and clear, and a gentle zephyr-like breeze merely agitated the atmosphere. As we sat gazing over this delightful scene, and having found also so many lovely spots in this chain of mountains, I was tempted to believe I had discovered regions which might eventually support, not only flocks and herds, but which would become the centres of population also, each individual amongst whom would envy me us being the first discoverer of the scenes it so delighted them to view. For here were:—

“Long dreamy lawns, and birds on happy

wings

Keeping their homes in never-rifled bowers;

Cool fountains filling with their murmuring

The sunny silence 'twixt the charming hours.”

In the afternoon we returned to the camp, and again and again wondered at the singular manner in which the water existed here. Five hundred yards above or below there is no sign of water, but in that intermediate space a stream gushes out of the ground, fills a splendid little trough, and gushes into the ground again: emblematic indeed of the ephemeral existence of humanity—we rise out of the dust, flash for a brief moment in the light of life, and in another we are gone. We planted seeds here; I called it Titania's Spring, the watercourse in which it exists I called Moffatt's* Creek.

The night was totally different from the former, the mercury not falling below 66°. The horses upon being brought up to the camp this morning on foot, displayed such abominable liveliness and flashness, that there was no catching them. One colt, Blackie, who was the leader of the riot, I just managed at length to catch, and then we had to drive the others several times round the camp at a gallop, before their exuberance had in a measure subsided. It seemed, indeed, as if the fairies had been bewitching them during the night. It was late when we left the lovely spot. A pretty valley running north-west, with a creek in it, was our next road; our track wound about through the most splendidly grassed valleys, mostly having a trend westerly. At twelve miles we saw the gum timber of a watercourse, apparently debouching through a glen. Of course there was water, and a channel filled with reeds, down which the current ran in never-failing streams. This spot was another of those charming gems which exist in such numbers in this chain. This was another of those “secret nooks in a pleasant land, by the frolic fairies planned.” I called the place Glen Watson*. From a hill near I discovered that this chain had now become broken, and though it continues to run on still farther west, it seemed as though it would shortly end. The Mount Olga of my former expedition was now in view, and bore north 17° west, a considerable distance away. I was most anxious to visit it. On my former journey I had made many endeavours to reach it, but was prevented; now, however, I hoped no obstacle would occur, and I shall travel towards it to-morrow. There was more than a mile of running water here, the horses were up to their eyes in the most luxuriant vegetation, and our encampment was again in a most romantic spot. Ah! why should regions so lovely be traversed so soon? This chain of mountains is called the Musgrave Range. A heavy dew fell last night, produced, I imagine, by the moisture in the glen, and not by extraneous atmospheric causes, as we have had none for some nights previously.