CHAPTER 2.5. FROM 9TH NOVEMBER TO 23RD DECEMBER, 1873.

Alone. Native signs. A stinking pit. Ninety miles from water. Elder's Creek. Hughes's Creek. The Colonel's range. Rampart-like range. Hills to the north-east. Jamieson's range. Return to Fort Mueller. Rain. Start for the Shoeing Camp once more. Lightning Rock. Nothing like leather. Pharaoh's inflictions. Photophobists. Hot weather. Fever and philosophy. Tietkens's tank. Gibson taken ill. Mysterious disappearance of water. Earthquake shock. Concussions and falling rocks. The glen. Cut an approach to the water. Another earthquake shock. A bough-house. Gardens. A journey northwards. Pine-clad hills. New line of ranges. Return to depot.

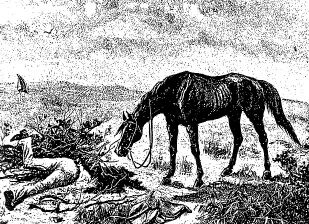

The following day was Sunday, the 9th of November, but was not a day of rest to any of us. Gibson and Jimmy started back with the packhorses for the Shoeing Camp, while I intended going westward, westward, and alone! I gave my horse another drink, and fixed a water-bag, containing about eight gallons, in a leather envelope up in a tree; and started away like errant knight on sad adventure bound, though unattended by any esquire or shield-bearer. I rode away west, over open triodia sandhills, with occasional dots of scrub between, for twenty miles. The horizon to the west was bounded by open, undulating rises of no elevation, but whether of sand or stone I could not determine. At this distance from the creek the sandhills mainly fell off, and the country was composed of ground thickly clothed with spinifex and covered all over with brown gravel. I gave my horse an hour's rest here, with the thermometer at 102° in the shade. There was no grass, and not being possessed of organs that could digest triodia he simply rested. On starting again, the hills I had left now almost entirely disappeared, and looked flattened out to a long low line. I travelled over many miles of burnt, stony, brown, gravelly undulations; at every four or five miles I obtained a view of similar country beyond; at thirty-five miles from the creek the country all round me was exactly alike, but here, on passing a rise that seemed a little more solid than the others, I noticed in a kind of little valley some signs of recent native encampments; and the feathers of birds strewn about—there were hawks', pigeons', and cockatoos' feathers. I rode towards them, and right under my horse's feet I saw a most singular hole in the ground. Dismounting, I found it was another of those extraordinary cups from whence the natives obtain water. This one was entirely filled up with boughs, and I had great difficulty in dragging them out, when I perceived that this orifice was of some depth and contained some water; but on reaching up a drop, with the greatest difficulty, in my hand, I found it was quite putrid; indeed, while taking out the boughs my nasal horgin, as Jimmy would call it, gave me the same information.

ILLUSTRATION 18

THE STINKING PIT.

I found the hole was choked up with rotten leaves, dead animals, birds, and all imaginable sorts of filth. On poking a stick down into it, seething bubbles aerated through the putrid mass, and yet the natives had evidently been living upon this fluid for some time; some of the fires in their camp were yet alight. I had very great difficulty in reaching down to bale any of this fluid into my canvas bucket. My horse seemed anxious to drink, but one bucketful was all he could manage. There was not more than five or six buckets of water in this hole; it made me quite sick to get the bucketful for the horse. There were a few hundred acres of silver grass in the little valley near, and as my horse began to feed with an apparent relish, I remained here, though I anticipated at any moment seeing a number of natives make their appearance. I said to myself, “Come one, come all, this rock shall fly from its firm base as soon as I.” No enemies came, and I passed the night with my horse feeding quietly close to where I lay. To this I attributed my safety.

Long before sunrise I was away from this dismal place, not giving my horse any more of the disgusting water. In a mile or two I came to the top of one of those undulations which at various distances bound the horizon. They are but swells a little higher than the rest of the country. How far this formation would extend was the question, and what other feature that lay beyond, at which water could be obtained, was a difficult problem to solve. From its appearance I was compelled to suppose that it would remain unaltered for a very considerable distance. From this rise all I could see was another; this I reached in nine miles. Nearly all the country hereabout had been burnt, but not very recently. The ground was still covered with gravel, with here and there small patches of scrub, the country in general being very good for travelling. I felt sure it would be necessary to travel 150 miles at least before a watered spot could be found. How ardently I wished for a camel; for what is a horse where waters do not exist except at great distances apart? I pushed on to the next rising ground, ten miles, being nearly twenty from where I had camped. The view from here was precisely similar to the former ones. My horse had not travelled well this morning, he seemed to possess but little pluck. Although he was fat yesterday, he is literally poor now. This horse's name was Pratt; he was a poor weak creature, and died subsequently from thirst. I am afraid the putrid water has made him ill, for I have had great difficulty in getting him to go. I turned him out here for an hour at eleven o'clock, when the thermometer indicated 102° in the shade. The horse simply stood in the shade of a small belt of mulga, but he would not try to eat. To the south about a mile there was apparently a more solid rise, and I walked over to it, but there was no cup either to cheer or inebriate. I was now over fifty miles from my water-bag, which was hanging in a tree at the mercy of the winds and waves, not to mention its removal by natives, and if I lost that I should probably lose my life as well. I was now ninety miles from the Shoeing Camp, and unless I was prepared to go on for another hundred miles; ten, fifteen, twenty, or fifty would be of little or no use. It was as much as my horse would do to get back alive. From this point I returned. The animal went so slowly that it was dusk when I got back to the Cup, where I observed, by the removal of several boughs, that natives had been here in my absence. They had put a lot of boughs back into the hole again. I had no doubt they were close to me now, and felt sure they were watching me and my movements with lynx-like glances from their dark metallic eyes. I looked upon my miserable wretch of a horse as a safeguard from them. He would not eat, but immediately hobbled off to the pit, and I was afraid he would jump in before I could stop him, he was so eager for drink. It was an exceedingly difficult operation to get water out of this abominable hole, as the bucket could not be dipped into it, nor could I reach the frightful fluid at all without hanging my head down, with my legs stretched across the mouth of it, while I baled the foetid mixture into the bucket with one of my boots, as I had no other utensil. What with the position I was in and the horrible odour which rose from the seething fluid, I was seized with violent retching. The horse gulped down the first half of the bucket with avidity, but after that he would only sip at it, and I was glad enough to find that the one bucketful I had baled out of the pit was sufficient. I don't think any consideration would have induced me to bale out another.

Having had but little sleep, I rode away at three o'clock next morning. The horse looked wretched and went worse. It was past midday when I had gone twenty miles, when, entering sandhill country, I was afraid he would knock up altogether. After an hour and a half's rest he seemed better; he walked away almost briskly, and we reached the water-bag much earlier than I expected. Here we both had a good drink, although he would have emptied the bag three times over if he could have got it. The day had been hot.

When I left this singular watercourse, where plenty of water existed in its upper portions, but was either too bitter or too salt for use, I named it Elder's Creek. The other that joins it I called Hughes's Creek, and the range in which they exist the Colonel's Range.

There was not much water left for the horse. He was standing close to the bag for some hours before daylight. He drank it up and away we went, having forty miles to go. I arrived very late. Everything was well except the water supply, and that was gradually ceasing. In a week there will be none. The day had been pleasant and cool.

Several more days were spent here, re-digging and enlarging the old tank and trying to find a new. Gibson and I went to some hills to the south, with a rampart-like face. The place swarmed with pigeons, but we could find no water. We could hear the birds crooning and cooing in all directions as we rode, “like the moan of doves in immemorial elms, and the murmurings of innumerable bees.” This rampart-like ridge was festooned with cypress pines, and had there been water there, I should have thought it a very pretty place. Every day was telling upon the water at the camp. We had to return unsuccessful, having found none. The horses were loose, and rambled about in several mobs and all directions, and at night we could not get them all together. The water was now so low that, growl as we may, go we must. It was five p.m. on the 17th of November when we left. The nearest water now to us that I knew of was at Fort Mueller, but I decided to return to it by a different route from that we had arrived on, and as some hills lay north-easterly, and some were pretty high, we went away in that direction.

We travelled through the usual poor country, and crossed several dry water-channels. In one I thought to get a drink for the horses. The party having gone on, I overtook them and sent Gibson back with the shovel. We brought the horses back to the place, but he gave a very gloomy opinion of it. The supply was so poor that, after working and watching the horses all night, they could only get a bucketful each by morning, and I was much vexed at having wasted time and energy in such a wretched spot, which we left in huge disgust, and continued on our course. Very poor regions were traversed, every likely-looking spot was searched for water. I had been steering for a big hill from the Shoeing Camp; a dry creek issued from its slopes. Here the hills ceased in this northerly direction, only to the east and south-east could ranges be seen, and it is only in them that water can be expected in this region. Fort Mueller was nearly fifty miles away, on a bearing of 30° south of east. We now turned towards it. A detached, jagged, and inviting-looking range lay a little to the east of north-east; it appeared similar to the Fort Mueller hills. I called it Jamieson's* Range, but did not visit it. Half the day was lost in useless searching for water, and we encamped without any; thermometer 104° at ten a.m. At night we camped on an open piece of spinifex country. We had thunder and lightning, and about six heat-drops of rain fell.

The next day we proceeded on our course for Fort Mueller; at twelve miles we had a shower of rain, with thunder and lightning, that lasted a few seconds only. We were at a bare rock, and had the rain lasted with the same force for only a minute, we could have given our horses a drink upon the spot, but as it was we got none. The horses ran all about licking the rock with their parched tongues.

Late at night we reached our old encampment, where we had got water in the sandy bed of the creek. It was now no longer here, and we had to go further up. I went on ahead to look for a spot, and returning, met the horses in hobbles going up the creek, some right in the bed. I intended to have dug a tank for them, but the others let them go too soon. I consoled myself by thinking that they had only to go far enough, and they would get water on the surface. With the exception of the one bucket each, this was their fourth night without water. The sky was now as black as pitch; it thundered and lightened, and there was every appearance of a fall of rain, but only a light mist or heavy dew fell for an hour or two; it was so light and the temperature so hot that we all lay without a rag on till morning.

At earliest dawn Mr. Tietkens and I took the shovel and walked to where we heard the horsebells. Twelve of the poor animals were lying in the bed of the creek, with limbs stretched out as if dead, but we were truly glad to find they were still alive, though some of them could not get up. Some that were standing up were working away with their hobbled feet the best way they could, stamping out the sand trying to dig out little tanks, and one old stager had actually reached the water in his tank, so we drove him away and dug out a proper place. We got all the horses watered by nine o'clock. It was four a.m. when we began to dig, and our exercise gave us an excellent appetite for our breakfast. Gibson built a small bough gunyah, under which we sat, with the thermometer at 102°.

In the afternoon the sky became overcast, and at six p.m. rain actually began to fall heavily, but only for a quarter of an hour, though it continued to drip for two or three hours. During and after that we had heavy thunder and most vivid lightnings. The thermometer at nine fell to 48°; in the sun to-day it had been 176°, the difference being 128° in a few hours, and we thought we should be frozen stiff where we stood. A slight trickle of surface water came down the creek channel. The rain seemed to have come from the west, and I resolved to push out there again and see. This was Friday; a day's rest was actually required by the horses, and the following day being Sunday, we yet remained.

MONDAY, 24TH NOVEMBER.

We had thunder, lightnings, and sprinklings of rain again during last night. We made another departure for the Shoeing Camp and Elder's Creek. At the bare rock previously mentioned, which was sixteen miles en route 30° north of west, we found the rain had left sufficient water for us, and we camped. The native well was full, and water also lay upon the rock. The place now seemed exceedingly pretty, totally different from its original appearance, when we could get no water at it. How wonderful is the difference the all-important element creates! While we were here another thunderstorm came up from the west and refilled all the basins, which the horses had considerably reduced. I called this the Lightning Rock, as on both our visits the lightning played so vividly around us. Just as we were starting, more thunder and lightnings and five minutes' rain came.

From here I steered to the one-bucket tank, and at one place actually saw water lying upon the ground, which was a most extraordinary circumstance. I was in great hopes the country to the west had been well visited by the rains. The country to-day was all dense scrubs, in which we saw a Mus conditor's nest. When in these scrubs I always ride in advance with a horse's bell fixed on my stirrup, so that those behind, although they cannot see, may yet hear which way to come. Continually working this bell has almost deprived me of the faculty of hearing; the constant passage of the horses through these direful scrubs has worn out more canvas bags than ever entered into my calculations. Every night after travelling, some, if not all the bags, are sure to be ripped, causing the frequent loss of flour and various small articles that get jerked out. This has gone on to such an extent that every ounce of twine has been used up; the only supply we can now get is by unravelling some canvas. Ourselves and our clothes, as well as our pack-bags, get continually torn also. Any one in future traversing these regions must be equipped entirely in leather; there must be leather shirts and leather trousers, leather hats, leather heads, and leather hearts, for nothing else can stand in a region such as this.

We continued on our course for the one-bucket place; but searching some others of better appearance, I was surprised to find that not a drop of rain had fallen, and I began to feel alarmed that the Shoeing Camp should also have been unvisited. One of the horses was unwell, and concealed himself in the scrubs; some time was lost in recovering him. As it was dark and too late to go on farther, we had to encamp without water, nor was there any grass.

The following day we arrived at the old camp, at which there had been some little rain. The horses were choking, and rushed up the gully like mad; we had to drive them into a little yard we had made when here previously, as a whole lot of them treading into the tank at once might ruin it for ever. The horse that hid himself yesterday knocked up to-day, and Gibson remained to bring him on; he came four hours after us, though we only left him three miles away. There was not sufficient water in the tank for all the horses; I was greatly grieved to find that so little could be got.

The camp ground had now become simply a moving mass of ants; they were bad enough when we left, but now they were frightful; they swarmed over everything, and bit us to the verge of madness. It is eleven days since we left this place, and now having returned, it seems highly probable that I shall soon be compelled to retreat again. Last night the ants were unbearable to Mr. Tietkens and myself, but Gibson and Jimmy do not appear to lose any sleep on their account. With the aid of a quart pot and a tin dish I managed to get some sort of a bath; but this is a luxury the traveller in these regions must in a great measure learn to do without. My garments and person were so perfumed with smashed ants, that I could almost believe I had been bathing in a vinegar cask. It was useless to start away from here with all the horses, without knowing how, or if any, rains had fallen out west. I therefore despatched Mr. Tietkens and Jimmy to take a tour round to all our former places. At twenty-five miles was the almost bare rocky hill which I called par excellence the Cups, from the number of those little stone indentures upon its surface, which I first saw on the 19th of October, this being the 29th of November. If no water was there, I directed Mr. Tietkens then only to visit Elder's Creek and return; for if there was none at the Cups, there would be but little likelihood of any in other places.

Gibson and I had a most miserable day at the camp. The ants were dreadful; the hot winds blew clouds of sandy dust all through and over the place; the thermometer was at 102°. We repaired several pack-bags. A few mosquitoes for variety paid us persistent attentions during the early part of the night; but their stings and bites were delightful pleasures compared to the agonies inflicted on us by the myriads of small black ants. Another hot wind and sand-dust day; still sewing and repairing pack-bags to get them into something like order and usefulness.

At one p.m. Mr. Tietkens returned from the west, and reported that the whole country in that direction had been entirely unvisited by rains, with the exception of the Cups, and there, out of several dozen rocky indents, barely sufficient water for their three horses could be got. Elder's Creek, the Cob tank, the Colonel's Range, Hughes's Creek, and all the ranges lying between here and there, the way they returned, were perfectly dry, not a drop of moisture having fallen in all that region. Will it evermore be thus? Jupiter impluvius? Thermometer to-day 106° in shade. The water supply is so rapidly decreasing that in two days it will be gone. This is certainly not a delightful position to hold, indeed it is one of the most horrible of imaginable encampments. The small water supply is distant about a mile from the camp, and we have to carry it down in kegs on a horse, and often when we go for it, we find the horses have just emptied and dirtied the tank. We are eaten alive by flies, ants, and mosquitoes, and our existence here cannot be deemed a happy one. Whatever could have obfuscated the brains of Moses, when he omitted to inflict Pharaoh with such exquisite torturers as ants, I cannot imagine. In a fiery region like to this I am photophobist enough to think I could wallow at ease, in blissful repose, in darkness, amongst cool and watery frogs; but ants, oh ants, are frightful! Like Othello, I am perplexed in the extreme—rain threatens every day, I don't like to go and I can't stay. Over some hills Mr. Tietkens and I found an old rocky native well, and worked for hours with shovel and levers, to shift great boulders of rock, and on the 4th of December we finally left the deceitful Shoeing Camp—never, I hope, to return. The new place was no better; it was two and a half miles away, in a wretched, scrubby, rocky, dry hole, and by moving some monstrous rocks, which left holes where they formerly rested, some water drained in, so that by night the horses were all satisfied. There was a hot, tropical, sultry feeling in the atmosphere all day, though it was not actually so hot as most days lately; some terrific lightnings occurred here on the night of the 5th of December, but we heard no thunder. On the 6th and 7th Mr. Tietkens and I tried several places to the eastwards for water, but without success. At three p.m. of the 7th, we had thunder and lightning, but no rain; thermometer 106°. On returning to camp, we were told that the water was rapidly failing, it becoming fine by degrees and beautifully less. At night the heavens were illuminated for hours by the most wonderful lightnings; it was, I suppose, too distant to permit the sound of thunder to be heard. On the 8th we made sure that rain would fall, the night and morning were very hot. We had clouds, thunder, lightning, thermometer 112° and every mortal disagreeable thing we wanted; so how could we expect rain? but here, thanks to Moses, or Pharaoh, or Providence, or the rocks, we were not troubled with ants. The next day we cleared out; the water was gone, so we went also. The thermometer was 110° in the shade when we finally left these miserable hills. We steered away again for Fort Mueller, via the Lightning Rock, which was forty-five miles away. We traversed a country nearly all scrub, passing some hills and searching channels and gullies as we went. We only got over twenty-one miles by night; I had been very unwell for the last three or four days, and to-day I was almost too ill to sit on my horse; I had fever, pains all over, and a splitting headache. The country being all scrub, I was compelled as usual to ride with a bell on my stirrup. Jingle jangle all day long; what with heat, fever, and the pain I was in, and the din of that infernal bell, I really thought it no sin to wish myself out of this world, and into a better, cooler, and less noisy one, where not even:—

“To heavenly harps the angelic choir,

Circling the throne of the eternal King; “

should:—

“With hallowed lips and holy fire,

Rejoice their hymns of praise to sing;”

which revived in my mind vague opinions with regard to our notions of heaven. If only to sit for ever singing hymns before Jehovah's throne is to be the future occupation of our souls, it is doubtful if the thought should be so pleasing, as the opinions of Plato and other philosophers, and which Addison has rendered to us thus:—

“Eternity, thou pleasing, dreadful

thought,

Through what variety of untried being,

Through what new scenes and changes must we pass

The wide, the unbounded prospect lies before me,” etc.

But I am trenching upon debatable ground, and have no desire to enter an argument upon the subject. It is doubtless better to believe the tenets taught us in our childhood, than to seek at mature age to unravel a mystery which it is self-evident the Great Creator never intended that man in this state of existence should become acquainted with. However, I'll say no more on such a subject, it is quite foreign to the matter of my travels, and does not ease my fever in any way—in fact it rather augments it.

The next morning, the 10th, I was worse, and it was agony to have to rise, let alone to ride. We reached the Lightning Rock at three p.m., when the thermometer indicated 110°. The water was all but gone from the native well, but a small quantity was obtained by digging. I was too ill to do anything. A number of native fig-trees were growing on this rock, and while Gibson was using the shovel, Mr. Tietkens went to get some for me, as he thought they might do me good. It was most fortunate that he went, for though he did not get any figs, he found a fine rock water-hole which we had not seen before, and where all the horses could drink their fill. I was never more delighted in my life. The thought of moving again to-morrow was killing—indeed I had intended to remain, but this enabled us all to do so. It was as much as I could do to move even the mile, to where we shifted our camp; thermometer 108°. By the next day, 12th, the horses had considerably reduced the water, and by to-morrow it will be gone. This basin would be of some size were it cleaned out; we could not tell what depth it was, as it is now almost entirely filled with the debris of ages. Its shape is elliptical, and is thirty feet long by fifteen broad, its sides being even more abrupt than perpendicular—that is to say, shelving inwards—and the horses could only water by jumping down at one place. There was about three feet of water, the rest being all soil. To-day was much cooler. I called this Tietkens's Tank. On the 14th, the water was gone, the tank dry, and all the horses away to the east, and it was past three when they were brought back. Unfortunately, Gibson's little dog Toby followed him out to-day and never returned. After we started I sent Gibson back to await the poor pup's return, but at night Gibson came without Toby; I told him he could have any horses he liked to go back for him to-morrow, and I would have gone myself only I was still too ill. During the night Gibson was taken ill just as I had been; therefore poor Toby was never recovered. We have still one little dog of mine which I bought in Adelaide, of the same kind as Toby, that is to say, the small black-and-tan English terrier, though I regret to say he is decidedly not, of the breed of that Billy indeed, who used to kill rats for a bet; I forget how many one morning he ate, but you'll find it in sporting books yet. It was very late when we reached our old bough gunyah camp; there was no water. I intended going up farther, but, being behind, Mr. Tietkens and Jimmy had began to unload, and some of the horses were hobbled out when I arrived; Gibson was still behind. For the second time I have been compelled to retreat to this range; shall I ever get away from it? When we left the rock, the thermometer indicated 110° in the shade.

Next morning I was a little better, but Gibson was very ill—indeed I thought he was going to die, and would he had died quietly there. Mr. Tietkens and I walked up the creek to look for the horses. We found and took about half of them to the surface water up in the narrow glen. When we arrived, there was plenty of water running merrily along the creek channel, and there were several nice ponds full, but when we brought the second lot to the place an hour and a half afterwards, the stream had ceased to flow, and the nice ponds just mentioned were all but empty and dry. This completely staggered me to find the drainage cease so suddenly. The day was very hot, 110°, when we returned to camp.

I was in a state of bewilderment at the thought of the water having so quickly disappeared, and I was wondering where I should have to retreat to next, as it appeared that in a day or two there would literally be no water at all. I felt ill again from my morning's walk, and lay down in the 110° of shade, afforded by the bough gunyah which Gibson had formerly made.

I had scarcely settled myself on my rug when a most pronounced shock of earthquake occurred, the volcanic wave, which caused a sound like thunder, passing along from west to east right under us, shook the ground and the gunyah so violently as to make me jump up as though nothing was the matter with me. As the wave passed on, we heard up in the glen to the east of us great concussions, and the sounds of smashing and falling rocks hurled from their native eminences rumbling and crashing into the glen below. The atmosphere was very still to-day, and the sky clear except to the deceitful west.

Gibson is still so ill that we did not move the camp. I was in a great state of anxiety about the water supply, and Tietkens and I walked first after the horses, and then took them up to the glen, where I was enchanted to behold the stream again in full flow, and the sheets of surface water as large, and as fine as when we first saw them yesterday. I was puzzled at this singular circumstance, and concluded that the earthquake had shaken the foundations of the hills, and thus forced the water up; but from whatsoever cause it proceeded, I was exceedingly glad to see it. To-day was much cooler than yesterday. At three p.m. the same time of day, we had another shock of earthquake similar to that of yesterday, only that the volcanic wave passed along a little northerly of the camp, and the sounds of breaking and falling rocks came from over the hills to the north-east of us.

Gibson was better on the 17th, and we moved the camp up into the glen where the surface water existed. We pitched our encampment upon a small piece of rising ground, where there was a fine little pool of water in the creek bed, partly formed of rocks, over which the purling streamlet fell, forming a most agreeable little basin for a bath.

The day was comparatively cool, 100°. The glen here is almost entirely choked up with tea-trees, and we had to cut great quantities of wood away so as to approach the water easily. The tea-tree is the only timber here for firewood; many trees are of some size, being seven or eight inches through, but mostly very crooked and gnarled. The green wood appears to burn almost as well as the dead, and forms good ash for baking dampers. Again to-day we had our usual shock of earthquake and at the usual time. Next day at three p.m., earthquake, quivering hills, broken and toppling rocks, with scared and agitated rock wallabies. This seemed a very ticklish, if not extremely dangerous place for a depot. Rocks overhung and frowned down upon us in every direction; a very few of these let loose by an earthquake would soon put a period to any further explorations on our part. We passed a great portion of to-day (18th) in erecting a fine large bough-house; they are so much cooler than tents. We also cleared several patches of rich brown soil, and made little Gardens (de Plantes), putting in all sorts of garden and other seeds. I have now discovered that towards afternoon, when the heat is greatest the flow of water ceases in the creek daily; but at night, during the morning hours and up to about midday, the little stream flows murmuring on over the stones and through the sand as merrily as one can wish. Fort Mueller cannot be said to be a pretty spot, for it is so confined by the frowning, battlemented, fortress-like walls of black and broken hills, that there is scarcely room to turn round in it, and attacks by the natives are much to be dreaded here.

We have had to clear the ground round our fort of the stones and huge bunches of triodia which we found there. The slopes of the hills are also thickly clothed with this dreadful grass. The horses feed some three or four miles away on the fine open grassy country which, as I mentioned before, surrounds this range. The herbage being so excellent here, the horses got so fresh, we had to build a yard with the tea-tree timber to run them in when we wanted to catch any. I still hope rain will fall, and lodge at Elder's Creek, a hundred miles to the west, so as to enable me to push out westward again. Nearly every day the sky is overcast, and rain threatens to fall, especially towards the north, where a number of unconnected ridges or low ranges lie. Mr. Tietkens and I prepared to start northerly to-morrow, the 20th, to inspect them.

We got out in that direction about twenty miles, passed near a hill I named Mount Scott*, and found a small creek, but no water. The country appeared to have been totally unvisited by rains.

We carried some water in a keg for ourselves, but the horses got none. The country passed over to-day was mostly red sandhills, recently burnt, and on that account free from spinifex. We travelled about north, 40° east. We next steered away for a dark-looking, bluff-ending hill, nearly north-north-east. Before arriving at it we searched among a lot of pine-clad hills for water without effect, reaching the hill in twenty-two miles. Resting our horses, we ascended the hill; from it I discovered, with glasses, that to the north and round easterly and westerly a number of ranges lay at a very considerable distance. The nearest, which lay north, was evidently sixty or seventy miles off. These ranges appeared to be of some length, but were not sufficiently raised above the ocean of scrubs, which occupied the intervening spaces, and rose into high and higher undulations, to allow me to form an opinion with regard to their altitude. Those east of north appeared higher and farther away, and were bolder and more pointed in outline. None of them were seen with the naked eye at first, but, when once seen with the field-glasses, the mind's eye would always represent them to us, floating and faintly waving apparently skywards in their vague and distant mirage. This discovery instantly created a burning desire in both of us to be off and reach them; but there were one or two preliminary determinations to be considered before starting. We are now nearly fifty miles from Fort Mueller, and the horses have been all one day, all one night, and half to-day without water. There might certainly be water at the new ranges, but then again there might not, and although they were at least sixty miles off, our horses might easily reach them. If, however, no water were found, they and perhaps we could never return. My reader must not confound a hundred miles' walk in this region with the same distance in any other. The greatest walker that ever stepped would find more than his match here. In the first place the feet sink in the loose and sandy soil, in the second it is densely covered with the hideous porcupine; to avoid the constant prickings from this the walker is compelled to raise his feet to an unnatural height; and another hideous vegetation, which I call sage-bush, obstructs even more, although it does not pain so much as the irritans. Again, the ground being hot enough to burn the soles off one's boots, with the thermometer at something like 180° in the sun, and the choking from thirst at every movement of the body, is enough to make any one pause before he foolishly gets himself into such a predicament. Discretion in such a case is by far the better part of valour—for valour wasted upon burning sands to no purpose is like love's labour lost.

Close about in all directions, except north, were broken masses of hills, and we decided to search among them for a new point of departure. We re-saddled our horses, and searched those nearest, that is to say easterly; but no water was found, nor any place that could hold it for an hour after it fell from the sky. Then we went north-west, to a bare-looking hill, and others with pines ornamenting their tops; but after travelling and searching all day, and the horses doing forty-six miles, we had to camp again without water.

In the night the thermometer went down to 62°. I was so cold that I had to light a fire to lie down by. All this day was uselessly lost in various traverses and searchings without reward; and after travelling forty-two miles, the unfortunate horses had to go again for the third night without water. We were, however, nearing the depot again, and reached it, in sixteen miles, early the next morning. Thankful enough we were to have plenty of water to drink, a bath, and change of clothes.