CHAPTER 4.2. FROM 27TH JULY TO 6TH OCTOBER, 1875.

Ooldabinna depot. Tietkens and Young go north. I go west. A salt expanse. Dense scrubs. Deposit two casks of water. Silence and solitude. Native footmarks. A hollow. Fine vegetation. A native dam. Anxiety. A great plain. A dry march. Return to the depot. Rain. My officers' report. Depart for the west. Method of travelling. Kill a camel. Reach the dam. Death or victory. Leave the dam. The hazard of the die. Five days of scrubs. Enter a plain. A terrible journey. Saleh prays for a rock-hole. A dry basin at 242 miles. Watering camels in the desert. Seventeen days without water. Saved. Tommy finds a supply. The Great Victoria Desert. The Queen's Spring. Farther still west.

On leaving Youldeh I had the choice of first visiting the native well my two officers had found at the flat tops, eighty-two miles, or the further one at Ooldabinna, which was ninety-two. I decided to go straight for the latter. The weather was cool, and the camels could easily go that distance without water. Their loads were heavy, averaging now 550 pounds all round. The country all the way consisted first, of very high and heavy sandhills, with mallee scrubs and thick spinifex, with occasional grassy flats between, but at one place we actually crossed a space of nearly ten miles of open, good grassy limestone country. We travelled very slowly over this region. There was a little plant, something like mignonette, which the camels were extremely fond of; we met it first on the grassy ground just mentioned, and when we had travelled from fifteen to eighteen miles and found some of it we camped. It took us five days and a half to reach Ooldabinna, and by the time we arrived there I had travelled 1010 miles from Beltana on all courses. I found Ooldabinna to consist of a small, pretty, open space amongst the scrubs; it was just dotted over with mulga-trees, and was no doubt a very favourite resort of the native owners.

On the flat there was a place where for untold ages the natives have obtained their water supplies. There were several wells, but my experience immediately informed me that they were simply rockholes filled with soil from the periodical rain-waters over the little flat, the holes lying in the lowest ground, and I perceived that the water supply was very limited; fortunately, however, there was sufficient for our immediate requirements. The camels were not apparently thirsty when we arrived, but drank more the following day; this completely emptied all the wells, and our supply then depended upon the soakage, which was of such a small volume that I became greatly disenchanted with my new home. There was plenty of the mignonette plant, and the camels did very well; I wanted water here only for a month, but it seemed probable it would not last a week. We deepened all the wells, and were most anxious watchers of the fluid as it slowly percolated through the soil into the bottom of each. After I had been here two days, and the water supply was getting gradually but surely less, I naturally became most anxious to discover more, either in a west or northerly direction; and I again sent my two officers, Messrs. Tietkens and Young, to the north, to endeavour to discover a supply in that direction, while I determined to go myself to the west on a similar errand. I was desirous, as were they, that my two officers should share the honour of completing a line of discovery from Youldeh, northwards to the Everard and Musgrave Ranges, and thus connect those considerable geographical features with the coast-line at Fowler's Bay; and I promised them if they were fortunate and discovered more water for a depot to the north, that they should finish their line, whether I was successful to the west or not. This, ending at the Musgrave Ranges would form in itself a very interesting expedition. Those ranges lay nearly 200 miles to the north. As the Musgrave Range is probably the highest in South Australia and a continuous chain with the Everard Range, seventy or eighty miles this side of it, I had every reason to expect that my officers would be successful in discovering a fresh depot up in a northerly direction. Their present journey, however, was only to find a new place to which we might remove, as the water supply might cease at any moment, as at each succeeding day it became so considerably less. Otherwise this was a most pleasant little oasis, with such herbage for the camels that it enabled them to do with very little water, after their first good skinful.

We arrived here on Sunday, the 1st of August, and both parties left again on the 4th. Mr. Tietkens and Mr. Young took only their own riding and one baggage camel to carry water and other things; they had thirty gallons of water and ten days' provisions, as I expected they would easily discover water within less than 100 miles, when they would immediately return, as it might be necessary for them to remove the whole camp from this place. I trusted all this to them, requesting them, however, to hold out here as long as possible, as, if I returned unsuccessful from the west, my camels might be unable to go any farther.

I was sure that the region to the west was not likely to prove a Garden of Eden, and I thought it was not improbable that I might have to go 200 miles before I found any water. If unsuccessful in that way I should have precisely the same distance to come back again; therefore, with the probabilities of such a journey before me, I determined to carry out two casks of water to ninety or a hundred miles, send some of the camels back from that point and push on with the remainder. I took six excellent camels, three for riding and three for carrying loads—two carrying thirty gallons of water each, and the third provisions, rugs, gear, etc. I took Saleh, my only Afghan camel-man—usually they are called camel-drivers, but that is a misnomer, as all camels except riding ones must be led—and young Alec Ross; Saleh was to return with the camels from the place at which I should plant the casks, and Alec and I were to go on. The northern party left on the same day, leaving Peter Nicholls, my cook, and Tommy the black boy, to look after the camels and camp.

ILLUSTRATION 33

LITTLE SALT LAKE.

I will first give an outline of my journey to the west. The country, except in the immediate neighbourhood of the wells, was, as usual in this region, all sandhills and scrub, although at eighteen miles, steering west, I came upon the shores of a large salt depression, or lake-bed, which had numerous sandhill islands scattered about it. It appeared to extend to a considerable distance southerly. By digging we easily obtained a quantity of water, but it was all pure brine and utterly useless. After this we met lake-bed after lake-bed, all in a region of dense scrubs and sandhills for sixty miles, some were small, some large, though none of the size of the first one. At seventy-eight miles from Ooldabinna, having come as near west as it is possible to steer in such a country on a camel—of course I had a Gregory's compass—we had met no signs of water fit for man or animal to drink, though brine and bog existed in most of the lake-beds. The scrubs were very thick, and were chiefly mallee, the Eucalyptus dumosa, of course attended by its satellite spinifex. So dense indeed was the growth of the scrubs, that Alec Ross declared, figuratively speaking, “you could not see your hand before you.” We could seldom get a view a hundred yards in extent, and we wandered on farther and farther from the only place where we knew that water existed. At this distance, on the shores of a salt-lake, there was really a very pretty scene, though in such a frightful desert. A high, red earthy bank fringed with feathery mulga and bushes to the brink, overlooking the milk-white expanse of the lake, and all surrounded by a strip of open ground with the scrubs standing sullenly back. The open ground looked green, but not with fertility, for it was mostly composed of bushes of the dull green, salty samphire. It was the weird, hideous, and demoniacal beauty of absolute sterility that reigned here. From this place I decided to send Saleh back with two camels, as this was the middle of the fourth day. Saleh would have to camp by himself for at least two nights before he could reach the depot, and the thought of such a thing almost drove him distracted; I do not suppose he had ever camped out by himself in his life previously. He devoutly desired to continue on with us, but go he must, and go he did. We, however, carried the two casks that one of his camels had brought until we encamped for the fourth night, being now ninety miles from Ooldabinna.

After Saleh left us we passed only one more salt lake, and then the country became entirely be-decked with unbroken scrub, while spinifex covered the whole ground. The scrubs consisted mostly of mallee, with patches of thick mulga, casuarinas, sandal-wood, not the sweet-scented sandal-wood of commerce, which inhabits the coast country of Western Australia, and quandong trees, another species of the sandal-wood family. Although this was in a cool time of the year—namely, near the end of the winter—the heat in the day-time was considerable, as the thermometer usually stood as high as 96° in the shade, it was necessary to completely shelter the casks from the sun; we therefore cut and fixed over them a thick covering of boughs and leaves, which was quite impervious to the solar ray, and if nothing disturbed them while we were absent, I had no fear of injury to the casks or of much loss from evaporation. No traces of any human inhabitants were seen, nor were the usually ever-present, tracks of native game, or their canine enemy the wild dingo, distinguishable upon the sands of this previously untrodden wilderness. The silence and the solitude of this mighty waste were appalling to the mind, and I almost regretted that I had sworn to conquer it. The only sound the ear could catch, as hour after hour we slowly glided on, was the passage of our noiseless treading and spongy-footed “ships” as they forced their way through the live and dead timber of the hideous scrubs. Thus we wandered on, farther from our camp, farther from our casks, and farther from everything we wished or required. A day and a half after Saleh left us, at our sixth night's encampment, we had left Ooldabinna 140 miles behind. I did not urge the camels to perform quick or extraordinary daily journeys, for upon the continuance of their powers and strength our own lives depended. When the camels got good bushes at night, they would fill themselves well, then lie down for a sleep, and towards morning chew their cud. When we found them contentedly doing so we knew they had had good food. I asked Alec one morning, when he brought them to the camp, if he had found them feeding; he replied, “Oh, no, they were all lying down chewing their kid.” Whenever the camels looked well after this we said, “Oh, they are all right, they've been chewing their ‘kid.’”

No water had yet been discovered, nor had any place where it could lodge been seen, even if the latter rain itself descended upon us, except indeed in the beds of the salt-lakes, where it would immediately have been converted into brine. On the seventh day of our march we had accomplished fifteen miles, when our attention was drawn to a plot of burnt spinifex, surrounded by the recent foot-prints of natives. This set us to scan the country in every direction where any view could be obtained. Alec Ross climbed a tree, and by the aid of field-glasses discovered the existence of a fall of country into a kind of hollow, with an apparently broken piece of open grassy ground some distance to the south-west. I determined to go to this spot, whatever might be the result, and proceeded towards it; after travelling five miles, and closely approaching it, I was disgusted to find that it was simply the bed of a salt-lake, but as we saw numerous native foot-prints and the tracks of emus, wild dogs, and other creatures, both going to and coming from it, we went on until we reached its lonely shore. There was an open space all round it, with here and there a few trees belonging to the surrounding scrubs that had either advanced on to, or had not receded from the open ground. The bed of the lake was white, salty-looking, and dry; There was, however, very fine herbage round the shores and on the open ground. There was plenty of the little purple pea-vetch, the mignonette plant, and Clianthus Dampierii, or Sturt's desert-pea, and we turned our four fine camels out to graze, or rather browse, upon whatever they chose to select, while we looked about in search of the water we felt sure must exist here.

The day was warm for this time of year, the thermometer standing at 95° in the shade. But before we went exploring for water we thought it well to have some dinner. The most inviting looking spot was at the opposite or southern end of the lake, which was oval-shaped; we had first touched upon it at its northern end. Alec Ross walked over to inspect that, and any other likely places, while I dug wells in the bed of the lake. The soil was reasonably good and moist, and on tasting it I could discover no taint of salt, nor had the surface the same sparkling incrustation of saline particles that I had noticed upon all the other lake-beds. At ten or eleven inches I reached the bedrock, and found the soil rested upon a rotten kind of bluish-green slate, but no water in the numerous holes I dug rewarded me, so I gave it up in despair and returned to the camp to await Alec's report of his wanderings. On the way I passed by some black oak-trees near the margin, and saw where the natives had tapped the roots of most of them for water. This I took to be a very poor sign of any other water existing here. I could see all round the lake, and if Alec was unsuccessful there was no other place to search. Alec was a long time away, and it was already late when he returned, but on his arrival he rejoiced me with the intelligence that, having fallen in with a lot of fresh native tracks, all trending round to the spot that looked so well from this side, he had followed them, and they led him to a small native clay-dam on a clay-pan containing a supply of yellow water. This information was, however, qualified by the remark that there was not enough water there for the whole of our mob of camels, although there was plenty for our present number. We immediately packed up and went over to our new-found treasure.

This spot is 156 miles straight from our last watering-place at Ooldabinna. I was very much pleased with our discovery, though the quantity of water was very small, but having found some, we thought we might find more in the neighbourhood. At that moment I believe if we had had all our camels here they could all have had a good drink, but the evaporation being so terribly rapid in this country, by the time I could return to Ooldabinna and then get back here, the water would be gone and the dam dry. “Sufficient unto the day is the evil thereof” is, however, a maxim that explorers must very often be contented to abide by. Our camels got as much water as they chose to drink; they were not very big animals, but I am sure 150 gallons was consumed amongst the four. They were hobbled out in the excellent herbage, which was better here than where we first outspanned them. There was splendid grass as well as herbage, but camels seldom, if ever, touch it. The clianthus pea and the vetch pea they ate ravenously, and when they can get those they require very little water.

No natives appeared to be now in the immediate neighbourhood. This was a very pretty and charming little oasis-camp. We got a few bronze-winged pigeons that came by mistake to water that night. The following morning we found the camels had decamped, in consequence of their having had long hobbles allowed them, as we did not suppose they would ramble away from such splendid herbage and water. Alec went after them very early, but had not returned by midday. During his absence I was extremely anxious, for, if he should be unable to track, and should return without them, our case would be almost hopeless. If camels are determined to stampede and can get a good start, there is frequently no overtaking them on foot. They are not like horses, which will return of their own accord to water. Camels know their own powers and their own independence of man, and I believe that a camel, if not in subjection, might live for months without water, provided it could get succulent food. How anxiously I listened as hour after hour I maundered about this spot for the tinkling sound of the camels' bells! How often fancy will deceive even the strongest minds! Twenty times during that morning I could have sworn I heard the bells, and yet they were miles out of earshot. When Alec and I and the camels were all here together I thought this a very pretty place, but oh, how hideous did it appear while I was here alone, with the harrowing thought of the camels being lost and Alec returning without them. Death itself in any terrors clad would have been a more welcome sight to me then and there, than Alec Ross without the camels. But Alec Ross was a right smart chance of a young bushman, and I knew that nothing would prevent him from getting the animals so long as their hobbles held. If, however, they succeeded in breaking them, it would be good-bye for ever. As they can go in their hobbles, unless short, if they have a mind to stampede, as fast as a man can walk in this region, and with a whole night's start with loose legs, pursuit would be hopeless. But surely at last I hear the bells! Yes; but, strange to say, I did not hear them until Alec and the camels actually appeared through the edge of scrub. Alec said they had gone miles, and were still pushing on in single file when he got up to them.

Now that I had found this water I was undecided what to do. It would be gone before I could return to it, and where I should find any more to the west it was impossible to say; it might be 100, it might be 200, it might even be 300 miles. God only knows where the waters are in such a region as this. I hesitated for the rest of the day—whether to go still farther west in search of water, or to return at once and risk the bringing of the whole party here. Tietkens and Young, I reflected, have found a new depot, and perhaps removed the whole party to it. Then, again, they might not, but have had to retreat to Youldeh. Eventually I decided to go on a few miles more to the west, in order to see whether the character of the country was in any way altered before I returned to the depot.

We went about forty miles beyond the dam; the only alteration in the country consisted of a return to the salt-lake system that had ceased for so many miles prior to our reaching our little dam. At the furthest point we reached, 195 miles from the depot; it was upon the shore of another salt lake, no water of any kind was to be procured. The only horizon to be seen was about fifteen miles away, and was simply the rim of an undulation in the dreary scrubs covered with the usual timber—that is to say, a mixture of the Eucalyptus dumosa or mallee, casuarinas or black oaks, a few Grevilleas, hakea bushes, with leguminous trees and shrubs, such as mulga, and a kind of harsh-, silver wattle, looking bush. On the latter order of these trees and plants the camels find their sustenance. Two stunted specimens of the native orange-tree or capparis were seen where I had left the two casks. From my furthest point west, in latitude 29° 15´ and longitude 128° 3´ 30´´, I returned to the dam and found that even during my short absence of only three and a half days the diminution of the volume of water in it was amazing, and I was perfectly staggered at the decrease, which was at the rate of more than an inch per day. The dimensions of this singular little dam were very small: the depth was its most satisfactory feature. It was, as all native watering places are, funnel-shaped, and to the bottom of the funnel I could poke a stick about three feet, but a good deal of that depth was mud; the surface was not more than eight feet long, by three feet wide, its shape was elliptical; it was not full when we first saw it, having shrunk at least three feet from its highest water-mark. I now decided to return by a new and more southerly route to the depot, hoping to find some other waters on the way. At this dam we were 160 miles from Eucla Harbour, which I visited last February with my black boy Tommy and the three horses lost in pushing from Wynbring to the Finniss. North from Eucla, running inland, is a great plain. I now wished to determine how far north this plain actually extended. I was here in scrubs to the north of it. The last night we camped at the dam was exceedingly cold, the thermometer falling to 26° on the morning of the 16th of August, the day we left. I steered south-east, and we came out of the scrubs, which had been thinning, on to the great plain, in forty-nine or fifty miles. Changing my course here to east, we skirted along the edge of the plain for twenty-five miles. It was beautifully grassed, and had cotton and salt-bush on it: also some little clover hollows, in which rainwater lodges after a fall, but I saw none of any great capacity, and none that held any water. It was splendid country for the camels to travel over; no spinifex, no impediments for their feet, and no timber. A bicycle could be ridden, I believe, over the whole extent of this plain, which must be 500 or 600 miles long by nearly 200 miles broad, it being known as the Hampton plains in Western Australia, and ending, so to say, near Youldeh. Having determined where the plain extends at this part of it, I now changed my course to east north-east for 106 miles, through the usual sandhill scrubs and spinifex region, until we reached the track of the caravan from Youldeh, having been turned out of our straight course by a large salt lake, which most probably is the southern end of the one we met first, at eighteen miles west from Ooldabinna. By the tracks I could see that the party had not retreated to Youldeh, which was so far re-assuring. On the 22nd of August we camped on the main line of tracks, fifteen miles from home, when, soon after we started, it became very cloudy, and threatened to rain. The weather for the last six days has been very oppressive, the thermometer standing at 92 to 94°, every day when we outspanned, usually from eleven to half-past twelve, the hottest time of the day not having then been reached. As we approached the depot, some slight sprinklings of rain fell, and as we drew nearer and nearer, our anxiety to ascertain whether our comrades were yet there increased; also whether our camels, which had now come 196 miles from the dam, could get any water, for we had found none whatever on our return route. On mounting the last sandhill which shut out the view, we were pleased to see the flutterings of the canvas habitations in the hollow below, and soon after we were welcomed by our friends. Saleh had returned by himself all right, and I think much to his surprise had not been either killed, eaten, or lost in the bush. I was indeed glad to find the party still there, as I had great doubts whether they could hold out until my return. They were there, and that was about all, for the water in all the wells was barely sufficient to give our four camels a drink; there remained only a bucket or two of slush rather than water in the whole camp. It appeared, however, as though fortune were about to favour us, for the light droppings of rain continued, and before night we were compelled to seek the shelter of our tents. I was indeed thankful to Heaven for paying even a part of so longstanding a debt, although it owes me a good many showers yet; but being a patient creditor, I will wait. We were so anxious about the water that we were continually stirring out of the tents to see how the wells looked, and whether any water had yet ran into them, a slight trickling at length began to run into the best-catching of our wells, and although the rain did not continue long or fall heavily, yet a sufficiency drained into the receptacle to enable us to fill up all our water-holding vessels the next morning, and give a thorough good drink to all our camels. I will now give an account of how my two officers fared on their journey in search of a depot to the north.

Their first point was to the little native dam they had seen prior to the discovery of this place, and there they encamped the first night, ten miles from hence on a bearing of north 9° east. Leaving the dam, they went north for twenty-five miles over high sandhills and through scrubs, when they saw some fresh native tracks, and found a small and poor native well, in which there was only a bucketful or two of water. They continued their northern course for twenty-five miles farther, when they reached a hollow with natives' foot-marks all over it, and some diamond sparrows, Amadina of Gould. Again they were unsuccessful in all their searches for water. Going farther north for fifteen miles, they observed some smoke to the north-east, and reached the place in six or seven miles. Here they found and surprised a large family of natives, who had apparently only recently arrived. A wide and deep hollow or valley existed among high sandhill country, timbered mostly with a eucalyptus, which is simply a gigantic species of mallee, but as it grows singly, it resembles gum-trees. Having descended into this hollow, a mile and a half wide, they saw the natives, and were in hopes of obtaining some information from them, but unfortunately the whole mob decamped, uttering loud and prolonged cries. Following this valley still northwards they reached its head in about six miles, but could discover no place where the natives obtained their supplies of water. At this point they were travelling over burnt scrubby sandhill country still north, when the natives who had appeared so shy came running after them in a threatening manner, howling at them, and annoying them in every possible way. These people, who had now arrayed themselves in their war-paint, and had all their fighting weapons in hand, evidently meant mischief; but my officers managed to get away from them without coming to a hostile encounter. They endeavoured to parley with the natives and stopped for that purpose, but could gain no information whatever as to the waters in their territories. Four miles north were then travelled, over burnt country, and having failed in discovering any places or even signs, otherwise than the presence of black men, of places where water could be obtained, and being anxious about the state of the water supply at the depot, as I had advised them not to remain too long away from this point, whose position is in latitude 27° 48´ and longitude 131° 19´, they returned. The Musgrave Range, they said, was not more than 100 miles to the north of them, but they had not sighted it. They were greatly disappointed at their want of success, and returned by a slightly different route, searching in every likely-looking place for water, but finding none, though they are both of opinion that the country is watered by native wells, and had they had sufficient time to have more thoroughly investigated it, they would doubtless have been more successful. The Everard Range being about sixty miles south from the Musgrave chain, and they not having sighted it, I can scarcely think they could have been within 100 miles of the Musgrave, as from high sandhills that high feature should be visible at that distance.

When Alec Ross and I returned from the west the others had been back some days, and were most anxious to hear how we had got on out west.

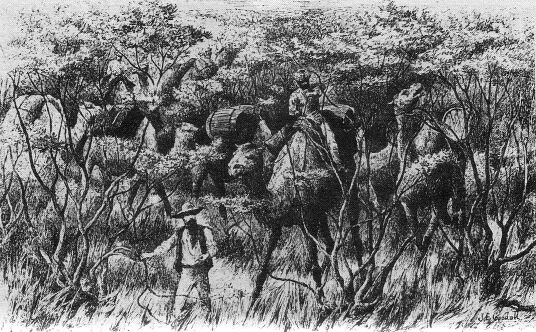

The usual anxiety at the camp was the question of water supply; I had found so little where I had been, and the water here was failing rapidly every day. Had it not been for last night's rain, we should be in a great difficulty this morning. Now, however, we had got our supply replenished by the light rain, and for the moment all was well; but it did not follow that because it rained here it must also rain at the little dam 160 miles away. Yet I decided to take the whole party to it, and as, by the blessing of Providence, we now had sufficient water for the purpose, to carry as much as we possibly could, so that if no rain had fallen at the dam when we arrived there, we should give the camels what water they carried and keep pushing on west, and trust to fate, or fortune, or chance, or Providence, or whatever it might be, that would bring us to water beyond. On the 24th August, having filled up everything that could hold a drop of water, we departed from this little isolated spot, having certainly 160 miles of desert without water to traverse, and perhaps none to be found at the end. Now, having everything ready, and watered our camels, we folded our tents like the Arabs, and as silently stole away. In consequence of having to carry so much water, our loads upon leaving Ooldabinna were enormously heavy, and the weather became annoyingly hot just as we began our journey. The four camels which Alec Ross and I had out with us looked wretched objects beside their more fortunate companions that had been resting at Ooldabinna, and were now in excellent condition; our unfortunates, on the contrary, had been travelling for seventeen days at the rate of twenty-three miles per day, with only one drink of water in the interval. These four were certainly excellent animals. Alec rode my little riding cow Reechy. I had a splendid gelding, which I named the Pearl Beyond all Price, though he was only called the Pearl. He was a beautiful white camel. Another cow I called the Wild Gazelle, and we had a young bull that afterwards became Mr. Tietkens's riding camel. It is unnecessary to record each day's proceedings through these wretched scrubs, as the record of “each dreary to-morrow but repeats the dull tale of to-day.” But I may here remark that camels have a great advantage over horses in these dense wildernesses, for the former are so tall that their loads are mostly raised into the less resisting upper branches of the low trees of which these scrubs are usually composed, whereas the horses' loads being so much nearer the ground have to be dragged through the stouter and stronger lower limbs of the trees. Again, camels travel in one long single file, and where the leading camel forces his way the others all follow. It is of great importance to have some good leading camels. My arrangement for traversing these scrubs was as follows:—Saleh on his riding gelding, the most lion-hearted creature in the whole mob, although Saleh was always beating or swearing at him in Hindostanee, led the whole caravan, which was divided into three separate lots; at every sixth there was a break, and one of the party rode ahead of the next six, and so on. The method of leading was, when the scrubs permitted, the steersman would ride; if they were too thick for correct steering, he would walk; then a man riding or leading a riding camel to guide Saleh, who led the baggage mob. Four of us used to steer. I had taught Alec Ross, and we took an hour about, at a time. Immediately behind Saleh came three bull camels loaded with casks of water, each cask holding twenty gallons. These used to crash and smash down and through the branches, so that the passage was much clearer after them. All the rest of the equipment, including water-beds, boxes, etc., was encased in huge leather bags, except one cow's load; this, with the bags of flour on two other camels, was enveloped in green hide. The fortunate rider at the extreme end had a somewhat open groove to ride in. This last place was the privilege of the steersman when his hour of agony was up. After the caravan had forced its way through this forest primeval, there was generally left an open serpentine line about six feet above the ground, through the trees, and when a person was on this line they could see that something unusual must have passed through. On the ground was a narrower line about two feet wide, and sometimes as much as a foot deep, where one animal after another had stepped. In my former journals I mentioned that the spinifex wounded the horses' feet, and disfigured their coronets, it also used to take a good deal of hair off some of the horses' legs; but in the case of the camels, although it did not seem to excoriate them, it took every hair off their legs up to three feet from the ground, and their limbs turned black, and were as bright and shiny as a newly polished boot. The camels' hair was much finer than that of the horses', but their skin was much thicker, and while the horses' legs were punctured and suppurating, the camels' were all as hard as steel and bright as bayonets.

What breakfast we had was always taken very early, before it was light enough to track the camels; then, while some of the party went after them, the others' duty was to have all the saddles and packs ready for instant loading. Our shortest record of leaving a camp (On a piece of open ground.) was half an hour from the instant the first camel was caught, but it usually took the best part of an hour before a clearance could be effected. Upon leaving Ooldabinna we had our westerly tracks to follow; this made the road easier. At the ninety-mile place, where I left the two water casks, we were glad to find them all safe, and in consequence of the shade we had put over them, there had been no loss of water from evaporation. On the sixth night from Ooldabinna we were well on our way towards the little dam, having come 120 miles. The heat had been very oppressive. At dusk of that day some clouds obscured the sky, and light rain fell, continuing nearly all night. On the seventh day, the 30th of August, there was every appearance of wet setting in. I was very thankful, for now I felt sure we should find more water in the little dam than when I left it. We quietly ensconced ourselves under our tents in the midst of the scrubs, and might be said to have enjoyed a holiday as a respite and repose, in contrast to our usual perpetual motion. The ground was far too porous to hold any surface water, and had our camels wanted it never so much, it could only be caught upon some outspread tarpaulins; but what with the descending moisture, the water we carried and the rain we caught, we could now give them as much as they liked to drink, and I now felt sure of getting more when we arrived at the little dam. During the night of the 29th one of our best cow-camels calved. Unfortunately the animal strained herself so severely in one of her hips, or other part of her hind legs, that she could not rise from the ground. She seemed also paralysed with cold. Her little mite of a calf had to be killed. We milked the mother as well as we could while she was lying down, and we fed and watered her—at least we offered her food and water, but she was in too great pain to eat. Camel calves are, in proportion to their mothers, the most diminutive but pretty little objects imaginable. I delayed here an additional day on the poor creature's account, but all our efforts to raise her proved unsuccessful. I could not leave the poor dumb brute on the ground to die by inches slowly, by famine, and alone, so I in mercy shot her just before we left the place, and left her dead alongside the progeny that she had brought to life in such a wilderness, only at the expense of her own. She had been Mr. Tietkens's hack, and one of our best riding camels. We had now little over forty miles to go to reach the dam, and as all our water had been consumed, and the vessels were empty, the loads now were light enough. On the 3rd of September we arrived, and were delighted to find that not only had the dam been replenished, but it was full to overflowing. A little water was actually visible in the lake-bed alongside of it, at the southern end, but it was unfit for drinking.

The little reservoir had now six feet of water in it; there was sufficient for all my expected requirements. The camels could drink at their ease and pleasure. The herbage and grass was more green and luxuriant than ever, and to my eyes it now appeared a far more pretty scene. There were the magenta-coloured vetch, the scarlet desert-pea, and numerous other leguminous plants, bushes, and trees, of which the camels are so fond. Mr. Young informed me that he had seen two or three natives from the spot at which we pitched our tents, but I saw none, and they never returned while we were in occupation of their property. This would be considered a pretty spot anywhere, but coming suddenly on it from the dull and sombre scrubs, the contrast makes it additionally striking. In the background to the south were some high red sandhills, on which grew some scattered casuarina of the black oak kind, which is a different variety from, and not so elegant or shady a tree as, the finer desert oak, which usually grows in more open regions. I have not as yet seen any of them on this expedition. All round the lake is a green and open space with scrubs standing back, and the white lake-bed in the centre. The little dam was situated on a piece of clay ground where rain-water from the foot of some of the sandhills could run into the lake; and here the natives had made a clumsy and (ab)original attempt at storing the water, having dug out the tank in the wrong place, at least not in the best position for catching the rain-water. I felt sure there was to be a waterless track beyond, so I stayed at this agreeable place for a week, in order to recruit the camels, and more particularly to enable another cow to calve. During this interval of repose we had continued oppressive weather, the thermometer standing from 92 and 94 to 96° every afternoon, but the nights were agreeably cool, if not cold. We had generally very cloudy mornings; the flies were particularly numerous and troublesome, and I became convinced that any further travel to the west would have to be carried on under very unfavourable circumstances. This little dam was situated in latitude 29° 19´ 4´´, and longitude 128° 38´ 16´´, showing that we had crossed the boundary line between the two colonies of South and Western Australia, the 129th meridian. I therefore called this the Boundary Dam. It must be recollected that we are and have been for 7 1/2° of longitude—that is to say, for 450 miles of westing, and 130 miles of northing—occupying the intervening period between the 9th of June, to the 3rd of September, entirely enveloped in dense scrubs, and I may say that very few if any explorers have ever before had such a region to traverse. I had managed to penetrate this country up to the present point, and it was not to be wondered at if we all ardently longed for a change. Even a bare, boundless expanse of desert sand would be welcomed as an alternative to the dark and dreary scrubs that surrounded us. However, it appeared evident to me, as I had traversed nothing but scrubs for hundreds of miles from the east, and had found no water of any size whatever in all the distance I had yet come, that no waters really existed in this country, except an occasional native well or native dam, and those only at considerable distances apart. Concluding this to be the case, and my object being that the expedition should reach the city of Perth, I decided there was only one way to accomplish this—namely, to go thither, at any risk, and trust to Providence for an occasional supply of water here and there in the intermediate distance. I desired to make for a hill or mountain called Mount Churchman by Augustus Churchman Gregory in 1846. I had no written record of water existing there, but my chart showed that Mount Churchman had been visited by two or three other travellers since that date, and it was presumable that water did permanently exist there. The hill was, however, distant from this dam considerably over 600 miles in a straight line, and too far away for it to be possible we could reach it unless we should discover some new watering places between. I was able to carry a good supply of water in casks, water-beds and bags; and to enable me to carry this I had done away with various articles, and made the loads as light as possible; but it was merely lightening them of one commodity to load them with a corresponding weight of water. At the end of a week I was tired of the listless life at the camp. The cow camel had not calved, and showed no greater disposition to do so now than when we arrived, so I determined to delay no longer on her account. The animals had done remarkably well here, as the feed was so excellent. The water that had been lying in the bed of the lake when we arrived had now dried up, and the quantity taken by ourselves and the camels from the little dam was telling very considerably upon its store—a plain intimation to us that it would soon become exhausted, and that for the sustenance of life more must be procured. Where the next favoured spot would be found, who could tell? The last water we had met was over 150 miles away; the next might be double that distance. Having considered all these matters, I informed my officers and men that I had determined to push westward, without a thought of retreat, no matter what the result might be; that it was a matter of life or death for us; we must push through or die in the scrubs. I added that if any more than one of the party desired to retreat, I would provide them with rations and camels, when they could either return to Fowler's Bay by the way we had come, or descend to Eucla Station on the coast, which lay south nearly 170 miles distant.

I represented that we were probably in the worst desert upon the face of the earth, but that fact should give us all the more pleasure in conquering it. We were surrounded on all sides by dense scrubs, and the sooner we forced our way out of them the better. It was of course a desperate thing to do, and I believe very few people would or could rush madly into a totally unknown wilderness, where the nearest known water was 650 miles away. But I had sworn to go to Perth or die in the attempt, and I inspired the whole of my party with my own enthusiasm. One and all declared that they would live or die with me. The natives belonging to this place had never come near us, therefore we could get no information concerning any other waters in this region. Owing to the difficulty of holding conversation with wild tribes, it is highly probable that if we had met them we should have got no information of value from them. When wild natives can be induced to approach and speak to the first travellers who trespass on their domains, they simply repeat, as well as they can, every word and action of the whites; this becomes so annoying that it is better to be without them. When they get to be more intimate and less nervous they also generally become more familiar, and want to see if white people are white all over, and to satisfy their curiosity in many ways. This region evidently does not support a very numerous tribe, and there is not much game in it. I have never visited any part of Australia so devoid of animal life.

On the 10th of September everything was ready, and I departed, declaring that:—

“Though the scrubs may range around me,

My camel shall bear me on;

Though the desert may surround me,

It hath springs that shall be won.”

Mounting my little fairy camel Reechy, I “whispered to her westward, westward, and with speed she darted onward.” The morning was cloudy and cool, and I anticipated a change from the quite sufficiently hot weather we had lately had, although I did not expect rain. We had no notion of how far we might have to go, or how many days might elapse before we came to any other water, but we left our friendly little dam in high hopes and excellent spirits, hoping to discover not only water, but some more agreeable geographical features than we had as yet encountered. I had set my own and all my companions' lives upon a cast, and will stand the hazard of the die, and I may add that each one displayed at starting into the new unknown, the greatest desire and eagerness for our attempt. On leaving the depot I had determined to travel on a course that would enable me to reach the 30th parallel of latitude at about its intersection with the 125th meridian of longitude; for I thought it probable the scrubs might terminate sooner in that direction than in one more northerly. Our course was therefore on a bearing of south 76° west; this left the line of salt lakes Alec Ross and I had formerly visited, and which lay west, on our right or northwards of us. Immediately after the start we entered thick scrubs as usual; they were mostly composed of the black oak, casuarina, with mulga and sandal-wood, not of commerce. We passed by the edge of two small salt depressions at six and nine miles; at ten miles we were overtaken by a shower of rain, and at eleven miles, as it was still raining slightly, we encamped on the edge of another lake. During the evening we saved sufficient water by means of our tarpaulins for all our own requirements. During the night it also rained at intervals, and we collected a lot of water and put it into a large canvas trough used for watering the camels when they cannot reach the water themselves. I carried two of these troughs, which held sufficient water for them all when at a watered camp, but not immediately after a dry stage; then they required to be filled three or four times. On the following morning, however, as we had but just left the depot, the camels would not drink, and as all our vessels were full, the water in the trough had to be poured out upon the ground as a libation to the Fates. In consequence of having to dry a number of things, we did not get away until past midday, and at eleven miles upon our course, after passing two small salt lagoons, we came upon a much larger one, where there was good herbage. This we took advantage of, and encamped there. Camels will not eat anything from which they cannot extract moisture, by which process they are enabled to go so long without water. The recent rain had left some sheets of water in the lake-bed at various places, but they were all as salt as brine—in fact brine itself.

The country we passed through to-day was entirely scrubs, except where the salt basins intervened, and nothing but scrubs could be seen ahead, or indeed in any other direction. The latitude of the camp on this lake was 29° 24´ 8´´, and it was twenty-two miles from the dam. We continued our march and proceeded still upon the same course, still under our usual routine of steering. By the fifth night of our travels we had met no water or any places that could hold it, and apparently we had left all the salt basins behind. Up to this point we had been continually in dense scrubs, but here the country became a little more open; myal timber, acacia, generally took the places of the mallee and the casuarinas; the spinifex disappeared, and real grass grew in its place. I was in hopes of finding water if we should debouch upon a plain, or perhaps discover some ranges or hills which the scrubs might have hidden from us. On the sixth day of our march we entered fairly on a plain, the country being very well grassed. It also had several kinds of salsolaceous bushes upon it; these furnish excellent fodder plants for all herbivorous animals. Although the soil was not very good, being sand mixed with clay, it was a very hard and good travelling country; the camels' feet left scarcely any impression on it, and only by the flattened grass and crushed plants trodden to earth by our heavy-weighing ships, could our trail now be followed. The plain appeared to extend a great distance all around us. A solemn stillness pervaded the atmosphere; nobody spoke much above a whisper. Once we saw some wild turkey bustards, and Mr. Young managed to wing one of them on the seventh day from the dam. On the seventh night the cow, for which we had delayed there, calved, but her bull-calf had to be destroyed, as we could not delay for it on the march. The old cow was in very good condition, went off her milk in a day or two, and continued on the journey as though nothing had occurred. On the eighth we had cold fowl for breakfast, with a modicum of water. On the ninth and tenth days of our march the plains continued, and I began to think we were more liable to die for want of water on them than in the dense and hideous scrubs we had been so anxious to leave behind. Although the region now was all a plain, no views of any extent could be obtained, as the country still rolled on in endless undulations at various distances apart, just as in the scrubs. It was evident that the regions we were traversing were utterly waterless, and in all the distance we had come in ten days, no spot had been found where water could lodge. It was totally uninhabited by either man or animal, not a track of a single marsupial, emu, or wild dog was to be seen, and we seemed to have penetrated into a region utterly unknown to man, and as utterly forsaken by God. We had now come 190 miles from water, and our prospects of obtaining any appeared more and more hopeless. Vainly indeed it seemed that I might say—with the mariner on the ocean—“Full many a green spot needs must be in this wide waste of misery, Or the traveller worn and wan never thus could voyage on.” But where was the oasis for us? Where the bright region of rest? And now, when days had many of them passed away, and no places had been met where water was, the party presented a sad and solemn procession, as though each and all of us was stalking slowly onward to his tomb. Some murmurs of regret reached my ears; but I was prepared for more than that. Whenever we camped, Saleh would stand before me, gaze fixedly into my face and generally say: “Mister Gile, when you get water?” I pretended to laugh at the idea, and say. “Water? pooh! There's no water in this country, Saleh. I didn't come here to find water, I came here to die, and you said you'd come and die too.” Then he would ponder awhile, and say: “I think some camel he die to-morrow, Mr. Gile” I would say: “No, Saleh, they can't possibly live till to-morrow, I think they will all die to-night.” Then he: “Oh, Mr. Gile, I think we all die soon now.” Then I: “Oh yes, Saleh, we'll all be dead in a day or two.” When he found he couldn't get any satisfaction out of me he would begin to pray, and ask me which was the east. I would point south: down he would go on his knees, and abase himself in the sand, keeping his head in it for some time. Afterwards he would have a smoke, and I would ask: “What's the matter, Saleh? what have you been doing?” “Ah, Mr. Gile,” was his answer, “I been pray to my God to give you a rock-hole to-morrow.” I said, “Why, Saleh, if the rock-hole isn't there already there won't be time for your God to make it; besides, if you can get what you want by praying for it, let me have a fresh-water lake, or a running river, that will take us right away to Perth. What's the use of a paltry rock-hole?” Then he said solemnly, “Ah, Mr. Gile, you not religious.”

On the eleventh day the plains died off, and we re-entered a new bed of scrubs—again consisting of mallee, casuarinas, desert sandal-wood, and quandong-trees of the same family; the ground was overgrown with spinifex. By the night of the twelfth day from the dam, having daily increased our rate of progress, we had traversed scrubs more undulating than previously, consisting of the usual kinds of trees. At sundown we descended into a hollow; I thought this would prove the bed of another salt lake, but I found it to be a rain-water basin or very large clay-pan, and although there were signs of the former presence of natives, the whole basin, grass, and herbage about it, were as dry as the desert around. Having found a place where water could lodge, I was certainly disappointed at finding none in it, as this showed that no rain whatever had fallen here, where it might have remained, when we had good but useless showers immediately upon leaving the dam. From the appearance of the vegetation no rains could possibly have visited this spot for many months, if not years. The grass was white and dry, and ready to blow away with any wind.

We had now travelled 242 miles from the little dam, and I thought it advisable here to give our lion-hearted camels a day's respite, and to apportion out to them the water that some of them had carried for that purpose. By the time we reached this distance from the last water, although no one had openly uttered the word retreat, all knowing it would be useless, still I was not unassailed by croakings of some of the ravens of the party, who advised me, for the sake of saving our own and some of the camels' lives, to sacrifice a certain number of the worst, and not give these unfortunates any water at all. But I represented that it would be cruel, wrong, and unjust to pursue such a course, and yet expect these neglected ones still to travel on with us; for even in their dejected state some, or even all, might actually go as far without water as the others would go with; and as for turning them adrift, or shooting them in a mob—which was also mooted—so long as they could travel, that was out of the question. So I declined all counsel, and declared it should be a case of all sink or all swim. In the middle of the thirteenth day, during which we rested for the purpose, the water was fairly divided among the camels; the quantity given to each was only a little over four gallons—about equivalent to four thimblesful to a man. There were eighteen grown camels and one calf, Youldeh, the quantity given was about eighty gallons. To give away this quantity of water in such a region was like parting with our blood; but it was the creatures' right, and carried expressly for them; and with the renewed vigour which even that small quantity imparted to them, our own lives seemed to obtain a new lease. Unfortunately, the old cow which calved at Youldeh, and whose she-calf is the prettiest and nicest little pet in the world, has begun to fail in her milk, and I am afraid the young animal will be unable to hold out to the end of this desert, if indeed it has an end this side of Perth. The position of this dry basin is in latitude 30° 7´ 3´´, and longitude 124° 41´ 2´´. Since reaching the 125th meridian, my course had been 5° more southerly, and on departing from this wretched basin on the 22nd of September, with animals greatly refreshed and carrying much lighter loads, we immediately entered dense scrubs, composed as usual of mallee, with its friend the spinifex, black oaks, and numerous gigantic mallee-like gum-trees. It seemed that distance, which lends enchantment to the view, was the only chance for our lives; distance, distance, unknown distance seemed to be our only goal. The country rose immediately from this depression into high and rolling hills of sand, and here I was surprised to find that a number of the melancholy cypress pines ornamented both the sandy hills and the spinifex depressions through and over which we went. Here, indeed, some few occasional signs and traces of the former presence of natives existed. The only water they can possibly get in this region must be from the roots of the trees. A great number of the so-called native poplar-trees, of two varieties, Codonocarpus, were now met, and the camels took huge bites at them as they passed by. The smaller vegetation assumed the familiar similitude to that around the Mount Olga of my two first horse expeditions. Two wild dog puppies were seen and caught by my black boy Tommy and Nicholls, in the scrubs to-day, the fourteenth from the dam. Tommy and others had also found a few Lowans', Leipoa ocellata, nests, and we secured a few of the pink-tinted eggs; this was the laying season. These, with the turkey Mr. Young had shot on the plain, were the only adjuncts to our supplies that we had obtained from this region. After to-day's stage there was nothing but the native poplar for the camels to eat, and they devoured the leaves with great apparent relish, though to my human taste it is about the most disgusting of vegetables. The following day, fifteenth from water, we accomplished twenty-six miles of scrubs. Our latitude here was 30° 17´. The country continued to rise into sandhills, from which the only views obtainable presented spaces precisely similar to those already traversed and left behind to the eastwards, and if it were only from our experience of what we had passed, that we were to gather intelligence of what was before us in the future, then would our future be gloomy indeed.

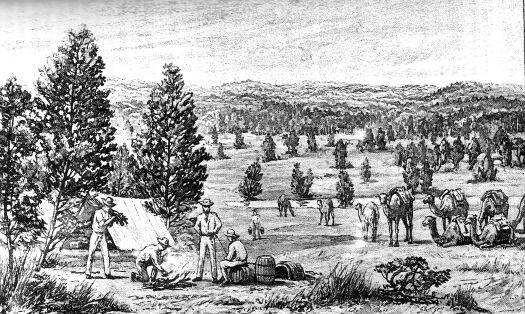

ILLUSTRATION 34

IN QUEEN VICTORIA'S DESERT

At twelve o'clock on the sixteenth day some natives' smoke was seen straight on our course, and also some of their foot-marks. The days throughout this march had been warm; the thermometer at twelve o'clock, when we let the camels lie down, with their loads on, for an hour, usually stood at 94, 95, or 96°, while in the afternoon it was some degrees hotter. On Saturday, the 25th of September, being the sixteenth day from the water at the Boundary Dam, we travelled twenty-seven miles, still on our course, through mallee and spinifex, pines, casuarinas, and quandong-trees, and noticed for the first time upon this expedition some very fine specimens of the Australian grass-tree, Xanthorrhoea; the giant mallee were also numerous. The latter give a most extraordinary appearance to the scenes they adorn, for they cheat the eye of the traveller into the belief that he is passing through tracts of alluvial soil, and gazing, upon the water-indicating gum-trees. This night we reached a most abominable encampment; there was nothing that the camels could eat, and the ground was entirely covered with great bunches of spinifex. Before us, and all along the western horizon, we had a black-looking and scrubby rise of very high sandhills; each of us noticed its resemblance to those sandhills which had confronted us to the north and east when at Youldeh. By observation we found that we were upon the same latitude, but had reached a point in longitude 500 miles to the west of it. It is highly probable that no water exists in a straight line between the two places. Shortly before evening, Mr. Young was in advance steering, but he kept so close under the sun—it being now so near the equinox, the sun set nearly west, and our course being 21° south of west—I had to go forward and tell him that he was not steering rightly. Of course he became indignant, and saying, “Perhaps you'll steer, then, if you don't think I can!” he handed me the compass. I took it in silence and steered more southerly, in the proper direction of our course; this led us over a long white ridge of sand, and brought us to the hollow where, as I said before, we had such a wretched encampment. I mention this as a circumstance attaches to it. The fate of empires at times has hung upon a thread, and our fate now hung upon my action. We had come 323 miles without having seen a drop of water. There was silence and melancholy in the camp; and was it to be wondered at if, in such a region and under such circumstances, there was:—

“A load on each spirit, a cloud o'er each

soul,

With eyes that could scan not, our destiny's scroll.”

Every man seemed to turn his eyes on me. I was the great centre of attraction; every action of mine was held to have some peculiar meaning. I was continually asked night after night if we should get water the following day? The reply, “How can I tell?” was insufficient; I was supposed to know to an inch where water was and exactly when we could reach it. I believe all except the officers thought I was making for a known water, for although I had explained the situation before leaving the dam, it was only now that they were beginning to comprehend its full meaning. Towards the line of dark sandhills, which formed the western horizon, was a great fall of country into a kind of hollow, and on the following morning, the seventeenth day from the dam, Mr. Tietkens appeared greatly impressed with the belief that we were in the neighbourhood of water. I said nothing of my own impressions, for I thought something of the kind also, although I said I would not believe it. It was Mr. Tietkens's turn to steer, and he started on foot ahead of the string of camels for that purpose. He gave Tommy his little riding-bull, the best leading camel we have, and told him to go on top of a white sandhill to our left, a little south of us, and try if he could find any fresh blacks' tracks, or other indications of water. I did not know that Tommy had gone, nor could I see that Tietkens was walking—it was an extraordinary event when the whole string of camels could be seen at once in a line in this country—and we had been travelling some two miles and a half when Alec Ross and Peter Nicholls declared that they heard Tommy calling out “water!” I never will believe these things until they are proved, so I kept the party still going on. However, even I, soon ceased to doubt, for Tommy came rushing through the scrubs full gallop, and, between a scream and a howl, yelled out quite loud enough now even for me to hear, “Water! water! plenty water here! come on! come on! this way! this way! come on, Mr. Giles! mine been find 'em plenty water!” I checked his excitement a moment and asked whether it was a native well he had found, and should we have to work at it with the shovel? Tommy said, “No fear shovel, that fellow water sit down meself (i.e. itself) along a ground, camel he drink 'em meself.” Of course we turned the long string after him. Soon after he left us he had ascended the white sandhill whither Mr. Tietkens had sent him, and what sight was presented to his view! A little open oval space of grass land, half a mile away, surrounded entirely by pine-trees, and falling into a small funnel-shaped hollow, looked at from above. He said that before he ascended the sandhill he had seen the tracks of an emu, and on descending he found the bird's track went for the little open circle. He then followed it to the spot, and saw a miniature lake lying in the sand, with plenty of that inestimable fluid which he had not beheld for more than 300 miles. He watered his camel, and then rushed after us, as we were slowly passing on ignorantly by this life-sustaining prize, to death and doom. Had Mr. Young steered rightly the day before—whenever it was his turn during that day I had had to tell him to make farther south—we should have had this treasure right upon our course; and had I not checked his incorrect steering in the evening, we should have passed under the northern face of a long, white sandhill more than two miles north of this water. Neither Tommy nor anybody else would have seen the place on which it lies, as it is completely hidden in the scrubs; as it was, we should have passed within a mile of it if Mr. Tietkens had not sent Tommy to look out, though I had made up my mind not to enter the high sandhills beyond without a search in this hollow, for my experience told me if there was no water in it, none could exist in this terrible region at all, and we must have found the tracks of natives, or wild dogs or emus leading to the water. Such characters in the book of Nature the explorer cannot fail to read, as we afterwards saw numerous native foot-marks all about. When we arrived with the camels at this newly-discovered liquid gem, I found it answered to Tommy's description. It is the most singularly-placed water I have ever seen, lying in a small hollow in the centre of a little grassy flat, and surrounded by clumps of the funereal pines, “in a desert inaccessible, under the shade of melancholy boughs.” While watering my little camel at its welcome waters, I might well exclaim, “In the desert a fountain is springing”—though in this wide waste there's too many a tree. The water is no doubt permanent, for it is supplied by the drainage of the sandhills that surround it, and it rests on a substratum of impervious clay. It lies exposed to view in a small open basin, the water being only about 150 yards in circumference and from two to three feet deep. Farther up the slopes, at much higher levels, native wells had been sunk in all directions—in each and all of these there was water. One large well, apparently a natural one, lay twelve or thirteen feet higher up than the largest basin, and contained a plentiful supply of pure water. Beyond the immediate precincts of this open space the scrubs abound.

It may be imagined how thankful we were for the discovery of this only and lonely watered spot, after traversing such a desert. How much longer and farther the expedition could have gone on without water we were now saved the necessity of guessing, but this I may truly say, that Sir Thomas Elder's South Australian camels are second to none in the world for strength and endurance. From both a human and humane point of view, it was most fortunate to have found this spring, and with it a respite, not only from our unceasing march, but from the terrible pressure on our minds of our perilous situation; for the painful fact was ever before us, that even after struggling bravely through hundreds of miles of frightful scrubs, we might die like dogs in the desert at last, unheard of and unknown. On me the most severe was the strain; for myself I cared not, I had so often died in spirit in my direful journeys that actual death was nothing to me. But for vanity, or fame, or honour, or greed, and to seek the bubble reputation, I had brought six other human beings into a dreadful strait, and the hollow eyes and gaunt, appealing glances that were always fixed on me were terrible to bear; but I gathered some support from a proverb of Solomon: “If thou faint in the day of adversity, thy strength is small.” Mount Churchman, the place I was endeavouring to reach, was yet some 350 miles distant; this discovery, it was therefore evident, was the entire salvation of the whole party.

During our march for these sixteen or seventeen days from the little dam, I had not put the members of my party upon an actual short allowance of water. Before we watered the camels we had over 100 gallons of water, yet the implied restraint was so great that we were all in a continual state of thirst during the whole time, and the small quantity of water consumed—of course we never had any tea or coffee—showed how all had restrained themselves.

ILLUSTRATION 35

QUEEN VICTORIA'S SPRING.

Geographical features have been terribly scarce upon this expedition, and this peculiar spring is the first permanent water I have found. I have ventured to dedicate it to our most gracious Queen. The great desert in which I found it, and which will most probably extend to the west as far as it does to the east, I have also honoured with Her Majesty's mighty name, calling it the Great Victoria Desert, and the spring, Queen Victoria's Spring. In future times these may be celebrated localities in the British Monarch's dominions. I have no Victoria or Albert Nyanzas, no Tanganyikas, Lualabas, or Zambezes, like the great African travellers, to honour with Her Majesty's name, but the humble offering of a little spring in a hideous desert, which, had it surrounded the great geographical features I have enumerated, might well have kept them concealed for ever, will not, I trust, be deemed unacceptable in Her Majesty's eyes, when offered by a loyal and most faithful subject.

On our arrival here our camels drank as only thirsty camels can, and great was our own delight to find ourselves again enabled to drink at will and indulge in the luxury of a bath. Added to both these pleasures was a more generous diet, so that we became quite enamoured of our new home. At this spring the thorny vegetation of the desert grew alongside the more agreeable water-plants at the water's edge, so that fertility and sterility stood side by side. Mr. Young planted some seeds of numerous vegetables, plants, and trees, and among others some of the giant bamboo, Dendrocalamus striatus, also Tasmanian blue gum and wattles. I am afraid these products of Nature will never reach maturity, for the natives are continually burning the rough grass and spinifex, and on a favourably windy occasion these will consume everything green or dry, down to the water's edge. There seems to be very little native game here, though a number of bronze-winged pigeons came to water at night and morning. There are, however, so many small native wells besides the larger sheet, for them to drink at, and also such a quantity of a thorny vegetation to screen them, that we have not been very successful in getting any. Our best shot, Mr. Young, succeeded in bagging only four or five. It was necessary, now that we had found this spring, to give our noble camels a fair respite, the more so as the food they will eat is very scarce about here, as we have yet over 300 miles to travel to reach Mount Churchman, with every probability of getting no water between. There are many curious flying and creeping insects here, but we have not been fortunate in catching many. Last night, however, I managed to secure and methylate a good-sized scorpion. After resting under the umbrageous foliage of the cypress-pines, among which our encampment was fixed for a week, the party and camels had all recovered from the thirst and fatigue of our late march, and it really seemed impossible to believe that such a stretch of country as 325 miles could actually have been traversed between this and the last water. The weather during our halt had been very warm, the thermometer had tried to go over 100° in the shade, but fell short by one degree. Yesterday was an abominable day; a heated tornado blew from the west from morning until night and continued until this morning, when, without apparent change otherwise, and no clouds, the temperature of the wind entirely altered and we had an exceedingly cool and delightful day. We found the position of this spring to be in latitude 30° 25´ 30´´ and longitude 123° 21´ 13´´. On leaving a depot and making a start early in the morning, camels, like horses, may not be particularly inclined to fill themselves with water, while they might do so in the middle of the day, and thus may leave a depot on a long dry march not half filled. The Arabs in Egypt and other camel countries, when starting for a desert march, force the animals, as I have seen—that is, read of—to fill themselves up by using bullocks' horns for funnels and pouring the water down their throats till the creatures are ready to burst. The camels, knowing by experience, so soon as the horns are stuck into their mouths, that they are bound for a desert march, fill up accordingly.

Strange to say, though I had brought from Port Augusta almost every article that could be mentioned for the journey, yet I did not bring any bullocks' horns, and it was too late now to send Tommy back to procure some; we consequently could not fill up our camels at starting, after the Arab fashion. In order to obviate any disadvantage on this account, to-day I sent, with Mr. Tietkens and Alec Ross, three camels, loaded with water, to be deposited about twenty-five miles on our next line of route, so that the camels could top up en passant. The water was to be poured into two canvas troughs and covered over with a tarpaulin. This took two days going and coming, but we remained yet another two, at the Queen's Spring.

Before I leave that spot I had perhaps better remark that it might prove a very difficult, perhaps dangerous place, to any other traveller to attempt to find, because, although there are many white sandhills in the neighbourhood, the open space on which the water lies is so small in area and so closely surrounded by scrubs, that it cannot be seen from any conspicuous one, nor can any conspicuous sandhill, distinguishable at any distance, be seen from it. It lies at or near the south-west end of a mass of white-faced sandhills; there are none to the south or west of it. While we remained here a few aboriginals prowled about the camp, but they never showed themselves. On the top of the bank, above all the wells, was a beaten corroborree path, where these denizens of the desert have often held their feasts and dances. Tommy found a number of long, flat, sword-like weapons close by, and brought four or five of them into the camp. They were ornamented after the usual Australian aboriginal fashion, some with slanting cuts or grooves along the blade, others with square, elliptical, or rounded figures; several of these two-handed swords were seven feet long, and four or five inches wide; wielded with good force, they were formidable enough to cut a man in half at a blow.

This spring could not be the only water in this region; I believe there was plenty more in the immediate neighbourhood, as the natives never came to water here. It was singular how we should have dropped upon such a scene, and penetrated thus the desert's vastness, to the scrub-secluded fastness of these Austral-Indians' home. Mr. Young and I collected a great many specimens of plants, flowers, insects, and reptiles. Among the flowers was the marvellous red, white, blue, and yellow wax-like flower of a hideous little gnarled and stunted mallee-tree; it is impossible to keep these flowers unless they could be hermetically preserved in glass; all I collected and most carefully put away in separate tin boxes fell to pieces, and lost their colours. The collection of specimens of all kinds got mislaid in Adelaide. Some grass-trees grew in the vicinity of this spring to a height of over twenty feet. On the evening of the 5th of October a small snake and several very large scorpions came crawling about us as we sat round the fire; we managed to bottle the scorpions, but though we wounded the snake it escaped; I was very anxious to methylate him also, but it appeared he had other ideas, and I should not be at all surprised if a pressing interview with his undertaker was one of them.

One evening a discussion arose about the moon, and Saleh was trying to teach Tommy something, God knows what, about it. Amongst other assertions he informed Tommy that the moon travelled from east to west, “because, you see, Tommy,” he said, “he like the sun—sun travel west too.” Tommy shook his head very sapiently, and said, “No, I don't think that, I think moon go the other way.” “No fear,” said Saleh, “how could it?” Then Peter Nicholls was asked, and he couldn't tell; he thought Saleh was right, because the moon did set in the west. So Tommy said, “Oh, well, I'll ask Mr. Giles,” and they came to where Mr. T, Mr. Y., and I were seated, and told us the argument. I said, “No, Saleh, the moon travels just the other way.” Then Tommy said, “I tole you so, I know,” but of course he couldn't explain himself. Saleh was scandalised, and all his religious ideas seemed upset. So I said, “Well, now, Saleh, you say the moon travels to the west; now do you see where she is to-night, between those two stars?” “Oh, yes,” he said, “I see.” I said, “If to-morrow night she is on the east side of that one,” pointing to one, “she must have travelled east to get there, mustn't she?” “Oh, no,” said Saleh, “she can't go there, she must come down west like the sun,” etc. In vain we showed him the next night how she had moved still farther east among the stars; that was nothing to him. It would have been far easier to have converted him to Christianity than to make him alter his original opinion. With regard to Tommy's ideas, I may say that nearly all Australian natives are familiar with the motions of the heavenly bodies, knowing the difference between a star and a planet, and all tribes that I have been acquainted with have proper names for each, the moon also being a very particular object of their attention.

While at this water we occasionally saw hawks, crows, corellas, a pink-feathered kind of cockatoo, and black magpies, which in some parts of the country are also called mutton birds, and pigeons. One day Peter Nicholls shot a queer kind of carrion bird, not so large as a crow, although its wings were as long. It had the peculiar dancing hop of the crow, its plumage was of a dark slate colour, with whitish tips to the wings, its beak was similar to a crow's.

We had now been at this depot for nine days, and on the 6th of October we left it behind to the eastward, as we had done all the other resting places we had found. I desired to go as straight as possible for Mount Churchman. Its position by the chart is in latitude 29° 58´, and longitude 118°. Straight lines on a map and straight lines through dense scrubs are, however, totally different, and, go as straight as we could, we must make it many miles farther than its distance showed by the chart.