Map 6

Fifth Expedition, 1876.

BOOK 5.

CHAPTER 5.1. FROM 18TH NOVEMBER, 1875, TO 10TH APRIL, 1876.

Remarks on the last expedition. Departure of my two officers. Expedition leaves Perth. Invited to York. Curiosity to see the caravan. Saleh and Tommy's yarns. Tipperary. Northam. Newcastle again. A pair of watch(ful) guards. St. Joseph's. Messrs. Clunes. The Benedictine monastery. Amusing incident. A new road. Berkshire Valley. Triumphal arch. Sandal-wood. Sheep poison. Cornamah. A survey party. Irwin House. Dongarra. An address presented. A French gentleman. Greenough Flats. Another address. Tommy's tricks. Champion Bay. Palmer's camp. A bull-camel poisoned. The Bowes. Yuin. A native desperado captured. His escape. Cheangwa. Native girls and boys. Depart for the interior. Natives follow us. Cooerminga. The Sandford. Moodilah. Barloweerie Peak. Pia Spring. Mount Murchison. Good pastoral country. Farewell to the last white man.

After having crossed the unknown central interior, and having traversed such a terrible region to accomplish that feat, it might be reasonably supposed that my labours as an explorer would cease, and that I might disband the expedition and send the members, camels, and equipment back to Adelaide by ship, especially as in my closing remarks on my last journey I said that I had accomplished the task I had undertaken, and effected the object of my expedition. This was certainly the case, but I regarded what had been done as only the half of my mission; and I was as anxious now to complete my work as I had been to commence it, when Sir Thomas Elder started me out. The remaining portion was no less than the completion of the line I had been compelled to leave unfinished by the untimely loss of Gibson, during my horse expedition of 1874. My readers will remember that, having pushed out west from my depot at Fort McKellar, in the Rawlinson Range, I had sighted another line of hills, which I had called the Alfred and Marie Range, and which I had been unable to reach. It was therefore my present wish and intention to traverse that particular region, and to connect my present explorations with my former ones with horses. By travelling northwards until I reached the proper latitude, I might make an eastern line to the Rawlinson Range. That Gibson's Desert existed, well I knew; but how far west from the Rawlinson it actually extended, was the problem I now wished to solve. As Sir Thomas Elder allowed me carte blanche, I began a fresh journey with this object. The incidents of that journey this last book will record.

My readers may imagine us enjoying all the gaieties and pleasures such a city as Perth, in Western Australia, could supply. Myself and two officers were quartered at the Weld Club; Alec Ross and the others had quarters at the United Service Club Hotel nearly opposite; and taking it altogether, we had very good times indeed. The fountains of champagne seemed loosened throughout the city during my stay; and the wine merchants became nervous lest the supply of what then became known as “Elder wine” should get exhausted. I paid a visit down the country southwards, to Bunbury, The Vasse, and other places of interest in that quarter. Our residence at Perth was extended to two months. Saleh was in his glory. The camels were out in a paddock, where they did not do very well, as there was only one kind of acacia tree upon which they could browse. Occasionally Saleh had to take two or three riding camels to Government House, as it became quite the thing, for a number of young ladies to go there and have a ride on them; and on those days Saleh was resplendent. On every finger, he wore a ring, he had new, white and coloured, silk and satin, clothes, covered with gilt braid; two silver watches, one in each side-pocket of his tunic; and two jockey whips, one in each hand. He used to tell people that he brought the expedition over, and when he went back he was sure Sir Thomas Elder would fit him out with an expedition of his own. Tommy was quite a young coloured swell, too; he would go about the town, fraternise with people, treat them to drinks at any hotel, and tell the landlord, when asked for payment, that the liquor was for the expedition. Every now and again I had little bills presented to me for refreshments supplied to Mr. Oldham. Alec Ross expended a good deal of his money in making presents to young ladies; and Peter Nicholls was quite a victim to the fair sex of his class. I managed to escape these terrible dangers, though I can't tell how.

Both my officers left for South Australia by the mail steamer. Mr. Tietkens was the more regretted. I did not wish him to leave, but he said he had private business to attend to. I did not request Mr. Young to accompany me on my return journey, so they went to Adelaide together. The remainder of the party stayed until the 13th of January, 1876, when the caravan departed from Perth on its homeward route to South Australia, having a new line of unexplored country to traverse before we could reach our goal. My projected route was to lie nearly 400 miles to the north of the one by which I arrived; and upon leaving Perth we travelled up the country, through the settled districts, to Champion Bay, and thence to Mount Gould, close to the River Murchison.

Before leaving the city I was invited by the Mayor and Municipality of the town of York, to visit that locality; this invitation I, of course, accepted, as I was supposed to be out on show. My party now consisted of only four other members besides myself, namely, young Alec Ross, now promoted to the post of second in command, Peter Nicholls, still cook, Saleh, and Tommy Oldham. At York we were entertained, upon our arrival, at a dinner. York was a very agreeable little agricultural town, the next in size to Fremantle. Bushmen, farmers, and country people generally, flocked in crowds to see both us and the camels. It was amusing to watch them, and to hear the remarks they made. Saleh and Tommy used to tell the most outrageous yarns about them; how they could travel ten miles an hour with their loads, how they carried water in their humps, that the cows ate their calves, that the riding bulls would tear their riders' legs off with their teeth if they couldn't get rid of them in any other way. These yarns were not restricted to York, they were always going on.

The day after leaving York we passed Mr. Samuel Burgess's establishment, called Tipperary, where we were splendidly entertained at a dinner, with his brothers and family. The Messrs. Burgess are among the oldest and wealthiest residents in the Colony. From hence we travelled towards a town-site called Northam, and from thence to Newcastle, where we were entertained upon our first arrival. A lady in Newcastle, Mrs. Dr. Mayhew, presented me with a pair of little spotted puppies, male and female, to act for us, as she thought, as watch(ful) guards against the attacks of hostile natives in the interior. And although they never distinguished themselves very much in that particular line, the little creatures were often a source of amusement in the camp; and I shall always cherish a feeling of gratitude to the donor for them.

At ten miles from Newcastle is Culham, the hospitable residence of the well-known and universally respected Squire Phillips, of an old Oxford family in England, and a very old settler in the Colony of Western Australia. On our arrival at Culham we were, as we had formerly been, most generously received; and the kindness and hospitality we met, induced us to remain for some days. When leaving I took young Johnny Phillips with me to give him an insight into the mysteries of camel travelling, so far as Champion Bay. On our road up the country we met with the greatest hospitality from every settler, whose establishment the caravan passed. At every station they vied with each other as to who should show us the greatest kindness. It seems invidious to mention names, and yet it might appear as though I were ungrateful if I seemed to forget my old friends; for I am a true believer in the dictum, of all black crimes, accurst ingratitude's the worst. Leaving Culham, we first went a few miles to Mr. Beare's station and residence, whither Squire Phillips accompanied us. Our next friend was Mr. Butler, at the St. Joseph's schoolhouse, where he had formerly presented me with an address. Next we came to the Messrs. Clunes, where we remained half an hour to refresh, en route for New Norcia, the Spanish Catholic Benedictine Monastery presided over by the good Bishop Salvado, and where we remained for the night; the Bishop welcoming us as cordially as before. Our next halt was at the McPhersons', Glentromie, only four or five miles from the Mission. Our host here was a fine, hospitable old Scotchman, who has a most valuable and excellent property. From Glentromie we went to the Hon. O'Grady Lefroy's station, Walebing, where his son, Mr. Henry Lefroy, welcomed us again as he had done so cordially on our first visit. At every place where we halted, country people continually came riding and driving in to see the camels, and an amusing incident occurred here. Young Lefroy had a tidy old housekeeper, who was quite the grande dame amongst the young wives and daughters of the surrounding farmers. I remained on Sunday, and, as usual, a crowd of people came. The camp was situated 200 yards from the buildings, and covered a good space of ground, the camels always being curled round into a circle whenever we camped; the huge bags and leather-covered boxes and pack-saddles filling up most of the space. On this Sunday afternoon a number of women, and girls, were escorted over by the housekeeper. Alec and I had come to the camp just before them, and we watched as they came up very slowly and cautiously to the camp. I was on the point of going over to them, and saying that I was sorry the camels were away feeding, but something Alec Ross said, restrained me, and we waited—the old housekeeper doing the show. To let the others see how clever she was, she came right up to the loads, the others following, and said, “Ah, the poor things!” One of the new arrivals said, “Oh, the poor things, how still and quiet they are,” the girls stretching their necks, and nearly staring their eyes out. Alec and I were choking with laughter, and I went up and said, “My dear creature, these are not the camels, these are the loads; the camels are away in the bush, feeding.” The old lady seemed greatly annoyed, while the others, in chorus, said, “Oh, oh! what, ain't those the camels there?” etc. By that time the old lady had vanished.

Up to this point we had returned upon the road we had formerly travelled to Perth; now we left our old line, and continued up the telegraph line, and main overland road, from Perth to Champion Bay. Here we shortly entered what in this Colony is called the Victoria Plains district. I found the whole region covered with thick timber, if not actual scrubs; here and there was a slight opening covered with a thorny vegetation three or four feet high. It struck me as being such a queer name, but I subsequently found that in Western Australia a plain means level country, no matter how densely covered with scrubs; undulating scrubs are thickets, and so on. Several times I was mystified by people telling me they knew there were plains to the east, which I had found to be all scrubs, with timber twenty to thirty feet high densely packed on it. The next place we visited, was Mr. James Clinche's establishment at Berkshire Valley, and our reception there was most enthusiastic. A triumphal arch was erected over the bridge that spanned the creek upon which the place was located, the arch having scrolls with mottoes waving and flags flying in our honour. Here was feasting and flaring with a vengeance. Mr. Clinche's hospitality was unbounded. We were pressed to remain a week, or month, or a year; but we only rested one day, the weather being exceedingly hot. Mr. Clinche had a magnificent flower and fruit garden, with fruit-trees of many kinds en espalier; these, he said, throve remarkably well. Mr. Clinche persisted in making me take away several bottles of fluid, whose contents need not be specifically particularised. Formerly the sandal-wood-tree of commerce abounded all over the settled districts of Western Australia. Merchants and others in Perth, Fremantle, York, and other places, were buyers for any quantity. At his place Mr. Clinche had a huge stack of I know not how many hundred tons. He informed me he usually paid about eight pounds sterling per measurement ton. The markets were London, Hong Kong, and Calcutta. A very profitable trade for many years was carried on in this article; the supply is now very limited.

There was a great deal of the poison-plant all over this country, not the Gyrostemon, but a sheep-poisoning plant of the Gastrolobium family; and I was always in a state of anxiety for fear the camels should eat any of it. The shepherds in this Colony, whose flocks are generally not larger than 500, are supposed to know every individual poison-plant on their beat, and to keep their sheep off it; but with us, it was all chance work, for we couldn't tie the camels up every night, and we could not control them in what they should eat. Our next friends were a brother of the McPherson at Glentromie and his wife. The name of this property was Cornamah; there was a telegraph station at this place. Both here and at Berkshire Valley Mrs. McPherson and Miss Clinche are the operators. Next to this, we reached Mr. Cook's station, called Arrino, where Mrs. Cook is telegraph mistress. Mr. Cook we had met at New Norcia, on his way down to Perth. We had lunch at Arrino, and Mrs. Cook gave me a sheep. I had, however, taken it out of one of their flocks the night before, as we camped with some black shepherds and shepherdesses, who were very pleased to see the camels, and called them emus, a name that nearly all the West Australian natives gave them.

After leaving Arrino we met Mr. Brooklyn and Mr. King, two Government surveyors, at whose camp we rested a day. The heat was excessive, the thermometer during that day going up 115° in the shade. The following day we reached a farm belonging to Mr. Goodwin, where we had a drink of beer all round. That evening we reached an establishment called Irwin House, on the Irwin River, formerly the residence of Mr. Lock Burgess, who was in partnership there with Squire Phillips. Mr. Burgess having gone to England, the property was leased to Mr. Fane, where we again met Mrs. Fane and her daughters, whom we had first met at Culham. This is a fine cattle run and farming property. From thence we went to Dongarra, a town-site also on the Irwin. On reaching this river, we found ourselves in one of the principal agricultural districts of Western Australia, and at Dongarra we were met by a number of the gentlemen of the district, and an address was presented to me by Mr. Laurence, the Resident Magistrate. After leaving Dongarra, we were entertained at his house by Mr. Bell; and here we met a French gentleman of a strong Irish descent, with fine white eyes and a thick shock head, of red hair; he gazed intently both at us and the camels. I don't know which he thought the more uncouth of the two kinds of beasts. At last he found sufficient English to say, “Do dem tings goo faar in a deayah, ehah?” When he sat down to dinner with us, he put his mutton chop on his hand, which he rested on his plate. The latter seemed to be quite an unknown article of furniture to him, and yet I was told his father was very well to do.

The next town-site we reached was the Greenough—pronounced Greenuff—Flats, being in another very excellent agricultural district; here another address was presented to me, and we were entertained at an excellent lunch. As usual, great numbers of people came to inspect us, and the camels, the latter laying down with their loads on previous to being let go. Often, when strangers would come too near, some of the more timid camels would jump up instantly, and the people not being on their guard, would often have torn faces and bleeding noses before they could get out of the way. On this occasion a tall, gaunt man and his wife, I supposed, were gazing at Tommy's riding camel as she carried the two little dogs in bags, one on each side. Tommy was standing near, trying to make her jump up, but she was too quiet, and preferred lying down. Any how, Tommy would have his joke—so, as the man who was gazing most intently at the pups said, “What's them things, young man?” he replied, “Oh, that's hee's pickaninnies”—sex having no more existence in a black boy's vocabulary than in a highlander's. Then the tall man said to the wife, “Oh, lord, look yer, see how they carries their young.” Only the pup's heads appeared, a string round the neck keeping them in; “but they looks like dogs too, don't they?” With that he put his huge face down, so as to gaze more intently at them, when the little dog, who had been teased a good deal and had got snappish, gave a growl and snapped at his nose. The secret was out; with a withering glance at Tommy and the camels, he silently walked away—the lady following.

All the riding camels and most of the pet baggage camels were passionately fond of bread. I always put a piece under the flap of my saddle, and so soon as Reechy came to the camp of a morning, she would come and lie down by it, and root about till she found it. Lots of the people, especially boys and children, mostly brought their lunch, as coming to see the camels was quite a holiday affair, and whenever they incautiously began to eat in the camp, half a dozen camels would try to take the food from them. One cunning old camel called Cocky, a huge beast, whose hump was over seven feet from the ground, with his head high up in the air, and pretending not to notice anything of the kind, would sidle slowly up towards any people who were eating, and swooping his long neck down, with his soft tumid lips would take the food out of their mouths or hands—to their utter astonishment and dismay. Another source of amusement with us was, when any man wanted to have a ride, we always put him on Peter Nicholls's camel, then he was led for a certain distance from the camp, when the rider was asked whether he was all right? He was sure to say, “Yes.” “Well, then, take the reins,” we would say; and so soon as the camel found himself free, he would set to work and buck and gallop back to the camp; in nine cases out of ten the rider fell off, and those who didn't never wished to get on any more. With the young ladies we met on our journeys through the settled districts, I took care that no accidents should happen, and always gave them Reechy or Alec's cow Buzoe. At the Greenough, a ball was given in the evening. (I should surely be forgetting myself were I to omit to mention our kind friend, Mr. Maley, the miller at Greenough, who took us to his house, gave us a lunch, and literally flooded us with champagne.) We were now only a short distance from Champion Bay, the town-site being called Geraldton; it was the 16th February when we reached it. Outside the town we were met by a number of gentlemen on horseback, and were escorted into it by them.

On arrival we were invited to a lunch. Champion Bay, or rather Geraldton, is the thriving centre of what is, for Western Australia, a large agricultural and pastoral district. It is the most busy and bustling place I have seen on this side of the continent. It is situated upon the western coast of Australia, in latitude 28° 40´ and longitude 114° 42´ 30´´, lying about north-north-west from Perth, and distant 250 miles in a straight line, although to reach it by land more than 300 miles have to be traversed. I delayed in the neighbourhood of Geraldton for the arrival of the English and Colonial mails, at the hospitable encampment of Mr. James Palmer, a gentleman from Melbourne, who was contractor for the first line of railway, from Champion Bay to Northampton, ever undertaken in Western Australia.

While we delayed here, Mr. Tietkens's fine young riding bull got poisoned, and though we did everything we possibly could for him, he first went cranky, and subsequently died. I was very much grieved; he was such a splendid hack, and so quiet and kind; I greatly deplored his loss. The only substance I could find that he had eaten was Gyrostemon, there being plenty of it here. Upon leaving Mr. Palmer's camp we next visited a station called the Bowes—being on the Bowes Creek, and belonging to Mr. Thomas Burgess, whose father entertained us so well at Tipperary, near York. Mr. Burgess and his wife most cordially welcomed us. This was a most delightful place, and so homelike; it was with regret that I left it behind, Mrs. Burgess being the last white lady I might ever see.

Mr. Burgess had another station called Yuin, about 115 miles easterly from here, and where his nephews, the two Messrs. Wittenoom, resided. They also have a station lying north-east by north called Cheangwa. On the fifth day from the Bowes we reached Yuin. The country was in a very dry state. All the stock had been removed to Cheangwa, where rains had fallen, and grass existed in abundance. At Yuin Mr. Burgess had just completed the erection of, I should say, the largest wool-shed in the Colony. The waters on the station consist of shallow wells and springs all over it. It is situated up the Greenough River. Before reaching Cheangwa I met the elder of the two Wittenooms, whom I had previously known in Melbourne; his younger brother was expected back from a trip to the north and east, where he had gone to look for new pastoral runs. When he returned, he told us he had not only been very successful in that way, but had succeeded in capturing a native desperado, against whom a warrant was out, and who had robbed some shepherds' huts, and speared, if not killed, a shepherd in their employ. Mr. Frank Wittenoom was leading this individual alongside of his horse, intending to take him to Geraldton to be dealt with by the police magistrate there. But O, tempora mutantur! One fine night, when apparently chained fast to a verandah post, the fellow managed to slip out of his shackles, quietly walked away, and left his fetters behind him, to the unbounded mortification of his captor, who looked unutterable things, and though he did not say much, he probably thought the more. This escape occurred at Yuin, to which place I had returned with Mr. E. Wittenoom, to await the arrival of Mr. Burgess. When we were all conversing in the house, and discussing some excellent sauterne, the opportunity for his successful attempt was seized by the prisoner. He effected his escape through the good offices of a confederate friend, a civilised young black fellow, who pretended he wanted his hair cut, and got a pair of sheep shears from Mr. Wittenoom during the day for that apparent purpose, saying that the captive would cut it for him. Of course the shears were not returned, and at night the captive or his friend used them to prise open a split link of the chain which secured him, and away he went as free as a bird in the air.

I had Mr. Burgess's and Mr. Wittenoom's company to Cheangwa, and on arrival there my party had everything ready for a start. We arranged for a final meeting with our kind friends at a spring called Pia, at the far northern end of Mr. Wittenoom's run. A great number of natives were assembled round Cheangwa: this is always the case at all frontier stations, in the Australian squatting bush. Some of the girls and young women were exceedingly pretty; the men were not so attractive, but the boys were good-looking youngsters. The young ladies were exceedingly talkative; they called the camels emus, or, as they pronounced it, immu. Several of these girls declared their intention of coming with us. There were Annies, and Lizzies, Lauras, and Kittys, and Judys, by the dozen. One interesting young person in undress uniform came up to me and said, “This is Judy, I am Judy; you Melbourne walk? me Melbourne walk too!” I said, “Oh, all right, my dear;” to this she replied, “Then you'll have to gib me dress.” I gave her a shirt.

When we left Cheangwa a number of the natives persisted in following us, and though we outpaced them in travelling, they stopping to hunt on the way, they found their way to the camp after us. By some of the men and boys we were led to a water-hole of some length, called Cooerminga, about eleven miles nearly north from Cheangwa. As the day was very warm, we and the natives all indulged promiscuously in the luxury of swimming, diving, and splashing about in all directions. It might be said that:—

“By yon mossy boulder, see an ebony

shoulder,

Dazzling the beholder, rises o'er the blue;

But a moment's thinking, sends the Naiad sinking,

With a modest shrinking, from the gazer's view.”

The day after we crossed the dry channel of what is called the River Sandford, and at two or three miles beyond it, we were shown another water called Moodilah, six miles from our last night's encampment. We were so hampered with the girls that we did not travel very rapidly over this part of the continent. Moodilah lay a little to the east of north from Cooerminga; Barloweerie Peak bore north 37° west from camp, the latitude of which was 27° 11´ 8´´. On Saturday, the 8th of April, we went nearly north to Pia Spring, where the following day we met for the last time, Messrs. Burgess and Wittenoom. We had some bottles of champagne cooling in canvas water-buckets, and we had an excellent lunch. The girls still remained with us, and if we liked we might have stayed to “sit with these dark Orianas in groves by the murmuring sea.”

On Sunday, the 9th of April, we all remained in peace, if not happiness, at Pia Spring; its position is in latitude 27° 7´ and longitude 116° 30´. The days were still very hot, and as the country produced no umbrageous trees, we had to erect awnings with tarpaulins to enable us to rest in comfort, the thermometer in the shade indicating 100°. Pia is a small granite rock-hole or basin, which contains no great supply of water, but seems to be permanently supplied by springs from below. From here Mount Murchison, near the eastern bank of the River Murchison, bore north 73° east, twenty-three or twenty-four miles away, and Barloweerie, behind us, bore south 48° west, eight miles.

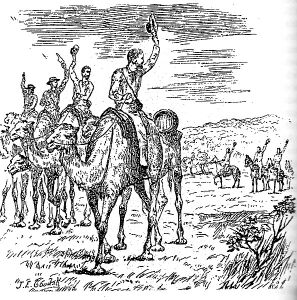

ILLUSTRATION 43

FAREWELL TO WESTERN AUSTRALIA.

The country belonging to Mr. Burgess and the Messrs. Wittenoom Brothers appeared to me the best and most extensive pastoral property I had seen in Western Australia. Water is obtained in wells and springs all over the country, at a depth of four or five feet; there are, besides, many long standing pools of rain-water on the runs. Mr. Burgess told me of a water-hole in a creek, called Natta, nine or ten miles off, where I intend to go next. On Monday, the 10th of April, we bade farewell to our two kind friends, the last white men we should see. We finished the champagne, and parted.