Reflecting Professor Brewster's own broad and eclectic interests in history, this lecture series has four goals: to provide students, faculty, and members of the larger community an opportunity to hear distinguished historians share their knowledge and mastery of the discipline; to stimulate an exchange of ideas and a continuing dialogue about issues of fundamental importance to mankind; to illuminate the present state of human affairs through the reflective prism of the past; and to support a critical requirement of modern times, the continuing process of education.

The first Brewster Lecture was presented in 1982 as part of East Carolina University's seventy-fifth anniversary celebration. The Lectures have been published since 1984. The current Lecture is eleventh in the series. The Department of History of East Carolina University is pleased to present the 1992 Lawrence F. Brewster Lecture, "After Columbus: Spain's Struggle for Atlantic Hegemony," by Geoffrey Parker, Professor of History at Yale University.

Mary Jo Bratton, Acting Chair

Department of History

Professor Parker is a prolific scholar who has authored numerous books, mostly on the history of Spain and her empire in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. His first monograph, The Army of Flanders and the Spanish Road, 1567-1659, which he wrote more than twenty years ago, remains the standard work on early modem Spanish military hegemony. In 1977 he published The Dutch Revolt, an analysis of Holland's war of independence against Spain, and a year later Philip II, a study of the man who dominated European affairs in the second half of the sixteenth century. In 1979 appeared his Europe in Crisis, 1598-1648 and Spain and the Netherlands, 1559-1659; and in 1984 The Thirty Years War, which reviewers have hailed as the most up-to-date and comprehensive account of that complex conflict. His most recent monographs are The Military Revolution: Military Innovation and the Rise of the West, 1500-1800 and The Spanish Armada, which he co-authored with Colin Martin. His Military Revolution received the Best Book of the Year Award in 1989 from the American Military Institute and the Dexter Prize from the Society for the History of Technology; The Spanish Armada made the British best seller charts for 14 weeks in 1988. All of these works have not only been translated into the major western languages but have appeared in paperback editions as well.

In addition, Professor Parker has edited at least eight books, among them The World: An Illustrated History, which was a Book of the Month Club selection. He is the editor of The Cambridge Illustrated History of Warfare, which is scheduled for publication in 1994. He has written dozens of scholarly essays and published numerous research guides and review essays.

Professor Parker has served as a consultant for several television productions on the history of Spain and Great Britain. A BBC Television broadcast on the quatercentenary of the voyage of the Spanish Armada, in which he was prominently featured, received the 1988 Best Television Documentary of the Year award in Britain. In 1992 he was featured in the PBS production on the "World of Columbus."

He is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society, a Fellow of the British Academy, and a Corresponding Fellow of the Spanish Royal Academy of History. In 1988 His Majesty the King of Spain conferred upon him the "Encomienda de la Orden de Isabel la Católica." We are honored to welcome him as our 11th Brewster Lecturer at East Carolina University.

Bodo Nischan

Professor of History

The "Columbus 500" commemoration recently focused attention upon the invasion of the Americas by groups of Europeans in the service of Spain in and immediately after the year 1492. Their achievement was indeed remarkable: within a generation-- by a combination of force, treachery and luck--they had established effective control over 750,000 square miles of the New World, an area four times as large as the peninsula from which most of them came, and over a population of some twenty million souls, seven times that of Spain. In addition, and equally remarkable, they had turned the ocean connecting southern Europe with the Caribbean into a Spanish Lake. The next generation of invaders did almost as well: the frontiers of European occupation were steadily advanced, even though the native population contained within them inexorably declined; and in the wake of Magellan's circumnavigation of the globe, the Pacific too became a Spanish Lake. All this formed the rich legacy of Columbus's epic voyage.

In an Atlas prepared for the future Philip II of Spain a half-century later, in 1542 (the year of the "New Laws" protecting the native Americans), the cosmographer Giovanni Battista Agnese gave pre-eminence to nautical achievements [see frontispiece]. Only two details of "human geography" adorned his map of the Spanish World: the sea-route to America and back, and Magellan's itinerary around the globe. At the time, both remained Hispanic monopolies.2 But by the first "centenary," in 1592, Columbus's legacy had been largely lost, for Spain's Atlantic hegemony was clearly shattered and her control of the Pacific lay under threat. It is true that some further spectacular additions had occurred, most notably the conquest of the Philippines in the 1570s and the acquisition of Portugal and her entire overseas empire in the 1580s, creating quite literally--and for the first time in History--an empire upon which the sun never set. But by 1592 it was an empire under siege. Francis Drake (known to Spaniards as "that notorious pirate" and to the rest of the world as "that heroic pioneer of the cause of freedom") led a small English fleet on a leisurely circumnavigation between 1577 and 1581, leaving a trail of destruction in his wake and returning with 100 tons of Spanish silver and 100 pounds of Spanish gold. In 1585 Drake took a far larger fleet to the Caribbean, sacking several Spanish settlements en route. And between 1589 and 1591 no less than 235 English ships sailed to America, taking by force what they failed to acquire by trade.3 The following decades saw more circumnavigations, more raids to the Caribbean, and more attacks on Spain's overseas colonies by her European enemies, while her surviving transatlantic trade could only function under the escort of flotillas so numerous that their cost undermined profits to the point where the trade itself began to wither. Worst of all, permanent settlements of English, French, Dutch and (eventually) Swedes and Germans sprang up along the eastern seaboard of the New World.

Of course not all of these developments were of equal significance because not all parts of the American continent were of equal value. The Deep South--Patagonia--was really only useful as a staging post on the arduous westward route around Cape Horn to Asia, while the Far North seemed to vindicate the native word that the Europeans encountered there most often: Canada, "it is worth nothing." Even the Pacific seaboard of North America was of questionable value: as late as 1848, in the wake of President Polk's Mexican War, many Americans felt that the "impenetrable mountains and dry narrow valleys" of California and "trackless, treeless... and utterly uninhabitable" New Mexico were not worth having (and were certainly not worth the $15 million that Mr. Polk had just paid for them).4 It is true that the Atlantic seaboard between the 37th and 42nd parallels--roughly from Roanoke to Manhattan--possessed great potential value thanks to their favorable climate and relative proximity to England; but the formidable bulk of the Appalachians, to say nothing of the tenacious opposition of the Indian nations in the region, made settlement in depth extremely difficult.

No, the "desirable" parts of America were precisely those areas acquired by the Iberian powers, from the river Plate to Florida in the east and from the river Bio-Bio to Baja California in the west. And any attempt to challenge the Iberian monopoly there was ruthlessly stifled. It was noticeable, however, that as time passed the preservation of that monopoly required increasing effort. Despite a spate of royal decrees ordering an increase in both the quantity and the size of ships laid down in the yards of Cantabria (so that between 1550 and 1570 Spain doubled its Atlantic tonnage), this shipbuilding program did not include the construction of ocean-going warships capable of operating effectively on the High Seas.5 Even the galleons specially constructed to escort the merchant convoys sailing to and from America were equipped with only a single gundeck and therefore could not serve as front-line warships.6 They were clearly unable to deal with the French expedition to Florida in 1565, which aimed at permanent settlement, and so the king was forced to commandeer merchant ships and supply them with ordnance, munitions and soldiers. In the end, however, 25 heavily armed merchantmen, commanded by Philip II's most successful High Seas Admiral Pedro Menéndez de Aviles, set forth and attacked the French settlers, persuaded them to surrender, and then massacred them.7

This stunning blow, coupled with a succession of civil wars, terminated France's presence in the Americas for half a century. And by the time she tried again, with Champlain and De Monts, Spain had already forfeited her hegemony in this continent to the far smaller and far less wealthy English. Precisely how Spain lost Columbus's legacy to Tudor England, through a fatal combination of misguided ambition and technical incompetence, is the subject of this presentation.

The story began in 1554 with the successful negotiations of the Emperor Charles V to marry his son and heir, Philip, to Queen Mary Tudor of England. This diplomatic and dynastic coup created a powerful new Habsburg constellation in western Europe, for the emperor (and later Philip II) also ruled Spain, much of Italy, the seventeen provinces of the Netherlands and the Free County of Burgundy, so that the acquisition of England completed the encirclement of France.8 However, in November 1558 Mary died, childless, and the English crown passed to her half-sister Elizabeth who soon showed unmistakable signs of wishing to reprotestantize her country. At first Philip, whose title "king of England" lapsed with his wife's death, tried to rectify the situation by matrimony--albeit with remarkably little enthusiasm. In January 1559, "feeling like a condemned man wondering what is to become of him," he asked for Elizabeth's hand in marriage but only, he emphasized, "to serve God and to see if this might prevent that lady from making the changes in religion that she has in mind." "Believe me," he told his ambassador in London, the count of Feria, "if it were not for God's sake, I would never do this. Nothing could or would make me do this except the clear knowledge that it might gain the kingdom [of England] for His service and faith."9 In the end, of course, Elizabeth rejected her graceless suitor and proceeded to effect "the changes in religion" required to make England Protestant again.

Philip II now faced an awkward dilemma. Unless he acted swiftly, Elizabeth's new religious settlement might become entrenched and therefore far more difficult to destroy at a later date. In a confidential letter to Ambassador Feria in March 1559 the king expressed his frustration:

This is certainly the most difficult decision I have ever faced in my whole life... and it grieves me to see what is happening over there [in England], and to be unable to take the steps to stop it that I want, while the steps I can take seem far milder than such a great evil deserves... But at the moment I lack the resources to do anything.

Later in the letter, the king returned to his point in a more forceful and calculating way:

The evil that is taking place in that kingdom has caused me the anger and confusion I have mentioned... but I believe we must try to remedy it without involving me or any of my vassals in a declaration of war until we have enjoyed the benefits of peace [for a while].10

The need to use force against Elizabethan England was thus explicitly recognized by Philip II from the very beginning. Moreover, at this time there was a good chance that firm measures might have succeeded: support for Protestantism remained largely confined to the southeast, with most English folk elsewhere (and, more importantly, most of the political and religious elite) apparently content to remain subject to Rome.11

However, two considerations ruled out an immediate assault on the Tudor state: first, after eight years of continuous war against both France and the Turks, Philip II's treasury in the spring of 1559 was empty and the funds to mount a major invasion of England were not readily available. Second, and more serious, the next in succession to the English throne, according to most observers, was Mary Stuart Queen of Scots who was, at this stage, even less acceptable to Spain than Elizabeth. On the one hand Mary's Catholic credentials were open to question for, although she subsequently played the role of Counter-Reformation martyr to perfection, it was a late development: in the 1560s, while she ruled Scotland, most of her ministers were Protestants and she eventually granted official recognition to the Protestant church and married a Protestant according to the Protestant rite. On the other hand, Mary Stuart was a French princess: her mother was French, she grew up in France, and her first husband was King Francis II of France! Together they styled themselves unambiguously "Francis and Mary, sovereigns of France, Scotland, England and Ireland": the titles appeared on their official seal [see plate 1], in their official documents, even (at least when the English ambassador came to call) on their dinner service. Although Francis died in 1560 and Mary returned reluctantly to Scotland, she remained French to the core: she continued to write almost all her letters in French, and in her Will of 1566 all of the first seven (and ten of the first twelve) beneficiaries were her French relatives. Small wonder that Philip II could see no advantage in toppling the neutral Elizabeth simply to turn England into a French satellite. When in 1565 Mary wrote to ask him for aid against common enemies of the Roman Church, the king only offered her assistance in Scotland.12

In 1567, however, a group of Scottish nobles rebelled against Mary and imprisoned her. After a few months she escaped from her captors and rode into England to seek the support of her apparently friendly neighbor and cousin. It was the biggest mistake of her life: Elizabeth promptly imprisoned her and kept her confined until, nineteen years later, she had her executed. From the moment Mary crossed the Border, the uneasy truce between Protestant England and Catholic Spain was doomed.

Philip II's initial reaction to Mary Stuart's flight was to urge his ambassador in England, Don Guerau de Spes, to steer clear of her.13 But Spes was not the man to neglect an opportunity to plot. Indefatigably he worked to win Mary's confidence and to put her in touch with dissident English Catholics, many of whom rose in rebellion against Elizabeth in 1569. With equal energy he worked to make the queen's ill-advised decision to detain a convoy transporting a consignment of treasure to Philip II's army in the Netherlands seem like a declaration of war, persuading the king to sequester all English property found in his dominions and to impose a trade embargo against England--measures which Elizabeth inevitably reciprocated.14

The turning-point, however, came in 1571 when Philip II lent his support to the plot of a Florentine adventurer, Roberto Ridolfi, and a group of English Catholics aimed at the removal of thequeeninfavorofMaryStuart. The king promised to dispatch a flotilla from Spain to the North Sea, where it would convoy 10,000 troops drawn from his forces stationed in the Netherlands, commanded by his most successful general (the duke of Alba), across to the coast of England to coincide with the Catholic uprising.15 In the event, the conspiracy was detected and the conspirators destroyed before they could act; but the extent of Spain's participation in the Ridolfi plot stood fully revealed. A letter written in September 1571 by Elizabeth's principal adviser, William Cecil Lord Burghley, made it clear that the queen already knew all about Mary's plans to escape and flee to Spain, where she would marry her son James to Philip II's daughter; and, above all, that she knew of Mary's "labors and devices to stir up a new rebellion in this realm [of England] and to have the king of Spain assist it."16

From this point on, Elizabeth never trusted Spain and its monarch again. Instead she openly welcomed and succored rebels against Philip, whether in the Netherlands, in America, or (after the Spanish annexation of 1580) in Portugal. She also tolerated, and sometimes directly supported, privateering activity against Spanish interests: no less than 11 major English expeditions sailed to the Caribbean between 1572 and 1577, plundering Spanish property and killing Spanish subjects.

Naturally, Philip II bitterly resented all this, but his hands were tied because, six months after the failure of the Ridolfi plot, the Netherlands--the designated launching pad for Spain's "army of liberation"--erupted in revolt and the rebels managed to entrench themselves in the maritime provinces of Holland and Zealand. Despite some important military successes, it soon became obvious that victory in the Low Countries depended upon securing command of the North Sea. Accordingly, in February 1574 the king signed orders to create a warfleet based on Santander "both to clear the western coasts and the Channel [of Dutch pirates] and to recapture some ports in the Netherlands occupied by the rebels." Pedro Menéndez de Avilés (the victor of Florida) was placed in command. The following month, however, Philip's frustration at the aid provided to the rebels by both Elizabeth and the French Protestants led him to transform both the scale and the aims of the operation. Orders were issued for the embargo of a total of 224 merchant ships in the ports of Spain, from which Menéndez could choose his task force, and a total of 11,000 men were to be made ready.17 Their goal was (first) to attack England, either by a direct assault or else via Ireland, and also if possible to destroy the Protestant pirate bases on the west coast of France, before going on to recapture the Dutch strongholds.18

This, of course, represented a totally impossible goal for a single campaigning season. Simply to locate and load the artillery and other equipment required to turn a merchantman into a fighting ship took months and, for such a huge undertaking (as Menéndez and several of Philip II's councilors pointed out), "it could take years."19 Sure enough, by September 1574 the great fleet for the conquest of England, Ireland, western France and the rebellious Dutch provinces had not even been collected into a single port and, worse still, many of the men assembled-- including Pedro Menéndez --had died of disease. So, with regret, the king admitted defeat and ordered the fleet to be stood down. He had squandered over 500,000 ducats on it; far more seriously, he had publicly demonstrated the limits to Spain's naval capacity.20 Admittedly, the following year, some 50 vessels carrying troops did leave Spain, causing near panic in England as they entered the Channel; but they were under strict orders to sail direct to the Netherlands--and even then some of the crews mutinied and demanded a return to Spain while others ran aground on the coast of Flanders.21 The Dutch Revolt therefore continued.

For a full decade after this reverse the king confined himself--rather like Elizabeth--to indirect attacks. He lent support to a papal plan to invade southwest Ireland and foment a major rebellion against English rule, and in 1580 the 800 Spanish and Italian volunteers who landed at Smerwick in County Kerry sailed in Spanish ships from a Spanish port; but Philip II was able to claim, when challenged, that they sailed under papal aegis and had nothing to do with him-- just as, the next year, the queen could assert that Drake had circumnavigated the world and plundered Spanish possessions entirely without her knowledge or consent.

At just this moment, possession of the Portuguese empire was thrown wide open by the death of the last legitimate male member of the house of Avis, leaving Philip II as the closest heir. In the course of 1580, thanks to a brilliant combined operation, mainland Portugal was occupied and orders were issued for all overseas possessions to recognize Philip as their lawful ruler. Moreover, apart from the wealth and resources of the Portuguese empire, Philip II gained an Atlantic battlefleet--ten huge fighting galleons constructed in the 1570s by the Portuguese crown for the defense of seaborne trade--together with the great natural harbor of Lisbon in which to station it. Apart from the Royal Navy, which at this time numbered scarcely 20 fighting ships, Philip now possessed the best warfleet in the Western World.

Its qualities were soon demonstrated. The Azores archipelago refused to recognize the Spanish succession and in 1582 an expeditionary force of 60 ships, led by the royal galleons and commanded by the resourceful and experienced marquis of Santa Cruz, sailed forth from Lisbon and destroyed the rebel fleet (assisted by French and English vessels) in battle. Only the island of Terceira now held out and in 1583 an even larger Armada, consisting of 98 ships and over 15,000 men (again commanded by Santa Cruz), carried out a skillful combined operation and reconquered it.

These events caused a sensation in Spain. Frenzied rejoicing took place and, according to a disgusted foreign ambassador, some Spaniards were so moved by euphoria that they claimed that ''even Christ was no longer safe in Paradise, for the marquis might go there to bring him back and crucify him all over again."22 Nor was celebration confined to verbal hyperbole: a bowl commemorating the Terceira landings (found among the wreckage of one of the Spanish Armada vessels that foundered off Ireland) shows Spain's warrior patron saint with new attributes. He still rides a charger, with his sword-arm raised to strike down his foes; but these foes are no longer cowering infidels. Instead they are the swirling waves of the Ocean Sea, waves now subdued by Spain along with the human enemies who sought refuge amongst them [see "Bowl"].

The euphoria even affected Santa Cruz who, flushed by his success, pointed out to the king in August 1583 that:

Victories as complete as the one God has been pleased to grant Your Majesty in these [Azores] islands normally spur princes on to other enterprises; and since Our Lord has made Your Majesty such a great king, it is just that you should follow up this victory by making arrangements for the invasion of England next year.

He recommended adding more vessels and troops to his victorious forces, and concentrating the expeditionary force in Lisbon in preparation for a rapid descent on the English coast as close to London as possible.23

There was much in favor of this belligerent stance. On the one hand, Elizabeth had allowed her fleet to decay: no new galJeon5 were launched from the royal dockyard5 between 1577 and 1586, and only two were rebuilt. On the other, although the number of English privateering raids seemed impressive, their achievements did not. Only Drake's circumnavigation returned a respectable profit, and even then perhaps three-quarters of those who set out died on the voyage. More typical was the troublesome voyage of Edward Fenton in 1582, which was supposed to sail to the Moluccas by way of Cape Horn and bring home a rich cargo of spices. It did not quite work out that way. The chief pilot, Mr. Thomas Hood, rejoiced in his unorthodox methods of navigation. "I give not a fart for... cosmography," he boasted, "for I can tell more than all the cosmographers in the world." Not surprisingly he guided his little fleet, not to the Moluccas, but first to Africa and then to the river Plate, where it was attacked by a Spanish squadron at a time when the crews were drunk. The damage sustained was so severe that most ships had to head back home, while one steered into the coast of Brazil and was wrecked, delivering the men aboard to the native Indians who (so it was rumored) enslaved the fittest and ate the rest.24

Nevertheless, although all the comforting details of Fenton's failure were known to Philip II, he remained reluctant to contemplate a new strike against Elizabeth. In response to Santa Cruz's suggestion, it is true, he did commission a number of cartographic surveys of the British coasts and studied the fate of previous invasions of England (from the Romans and Saxons down to the Smerwick landing); while he also consulted his military commander in the Netherlands, Alessandro Farnese, prince of Parma, to see if support for Santa Cruz's fleet might be provided from Flanders.25 But Parma demurred for, in the course of 1583, his troops regained the key ports of the Flemish coast--Dunkirk and Nieuwpoort--and stood poised to recapture some major cities of the interior. In 1584, Parma daringly decided to reduce Antwerp, boasting a population of 100,000 and five miles of state-of-the-art fortifications. His plan involved a blockade of the entire river system of the south Netherlands, with a massive fortified bridge across the Scheldt itself below Antwerp, in order to prevent the arrival of relief from either the sea or the interior.

Philip II approved and, as long as the siege of Antwerp continued (that is to say, for an entire year), he refused to act elsewhere and expressed irritation when others failed to endorse his strategic priorities. Thus a fervent request from the newly elected Pope Sixtus V in May 1585 for the king to undertake some "outstanding enterprise" (such as the invasion of England) led him to scribble angrily on the back of the letter:

Doesn't [the reconquest of] the Low Countries seem "outstanding" to them? Do they never consider how much it costs? There is little to be said about the English idea: one should stick to reality.26

For a time after this outburst it seemed as if the pope would settle for the recapture of Geneva, formerly a territory of the dukes of Savoy and now the citadel of Calvinism; but Sixtus soon returned to his demand that Spain should invade England before moving against Holland and Zealand, whose powers of resistance had been so amply demonstrated in the 1570s. But again Philip rejected the idea: the war in the Netherlands, he pointed out, was so expensive that no further commitment could be undertaken until all the rebellious provinces had been regained. He also called attention to the fact that he fought in the Low Countries in order to avoid any "concessions over religion" and "to maintain obedience there to God and his Holy See." He therefore invited the pope to contribute to the costs of the operation.27

But Sixtus V was both tenacious and resourceful: he now decided to send a personal envoy to Spain. His choice fell upon Luigi Dovara, a courtier of the grand duke of Florence, who took with him a promise that, should Spain attack England, both the papacy and Tuscany would contribute handsomely to the costs. This proposal, too, met with a deafening silence, and Dovara was beginning to abandon hope when news arrived at Court that an English expeditionary force led by Sir Francis Drake had invaded Galicia on 7 October 1585. Just over two weeks later, on 24 October, Philip II informed both the pope and the grand duke that he accepted their invitation to invade England and instructed his ambassador in Rome to ascertain how much papal money would be on the table.28

The origins of this remarkable volte-face, which began the Homeric duel that would decide the fate of the Americas, may be traced back to the consequences of the death, at the age of 29, of Francis Hercules, duke of Anjou, in June 1584. Anjou, although incompetent and unprepossessing, fulfilled two important political functions. First, the Dutch provinces in revolt against Philip II had in 1581 chosen him as their sovereign ruler; the duke, styled "prince and lord of the Netherlands," accordingly moved to Antwerp (then the rebels' capital), brought with him a powerful French army, and helped to maintain it with French gold.29 His death jeopardized continuing French support for the Dutch--especially after the assassination of William of Orange the following month--and so the survival of the rebellion itself.30 Second, under the "Salic Law" that restricted succession to the French crown to the nearest male relative of the monarch, Anjou had ranked as heir presumptive to his childless brother Henry III. His death left Henry of Bourbon, king of Navarre and leader of the French Protestants, as the nearest relative to Henry III in the male line. Since French Catholics considered any Protestant claimant totally unacceptable, militants among them created a paramilitary organization, the "League," dominated by Henry, duke of Guise, and dedicated to securing a Catholic succession. Guise promptly forged an alliance with Philip II, both to secure Spanish military assistance should civil war break out in France and to acquire Spanish funds to help keep the League's army prepared. The treaty of Joinville, signed on 31 December 1584, guaranteed both objectives. Then, in 1585, Henry III first refused a Dutch invitation to succeed his late brother as prince and lord of the Netherlands and then signed a formal agreement with Guise, the treaty of Nemours, ceding several important towns to the League's control and promising to assist its efforts to extirpate Protestantism.

All these developments enormously strengthened Philip II's international position. On the one hand, they improved his chances of reconquering the Netherlands; on the other, they ensured that, for the first time since his accession, he had nothing to fear from France. For precisely the same reasons, these events terrified Elizabeth. In October 1584, in the wake of the death of Anjou and Orange, her Privy Council conducted a major review of the Netherlands situation and concluded that without foreign aid the Dutch cause seemed hopeless. They urged the queen to intervene.31 Elizabeth refused, hoping against hope that Henry III would continue to support the Dutch, as his brother Anjou had done; but she did agree that, if no help came from other quarters, England would have to provide assistance.32 When, therefore, in March 1585 Henry III indicated that he would not help the Dutch, the queen began negotiations for a formal alliance with the rebel Republic.33 33

Although she wished to delay open support for the Dutch for as long as possible, fearing that it would lead directly to all-out war with Spain, Elizabeth did agree to sponsor another naval attack on Spanish overseas interests. Between July and December 1584, with the aid of a substantial grant from her Treasury, Sir Francis Drake assembled a fleet of 15 ships (two of them warships loaned from the Royal Navy) and 20 pinnaces, with 1600 men (500 of them soldiers) for an expedition to the East Indies.34 The following month the queen suspended the project-- although she allowed Sir Richard Grenville to lead a flotilla to create a fortified settlement in the Americas (which briefly took root at Roanoke in North Carolina)--but Philip II's decision in May 1585 to embargo all shipping, merchandise and men from northern Europe found in Iberian ports provoked another flurry of activity. In June the queen commissioned a small squadron to sail to Newfoundland with orders to attack the Iberian fishing fleet (it later returned to England with many boats and about 600 captive mariners) while in July her Privy Council issued letters of marque to enable subjects affected by the embargo to recoup their losses from any ship sailing under Philip II's colors.35

News of the alliances forged by the French Catholic League, first with Philip II and then with Henry III, finally seems to have persuaded Elizabeth of the need to sanction direct action against the king of Spain. In July 1585 Drake received permission to start purchasing stores and pressing men for his voyage "into forraine parts."36 One month later the queen signed the treaty of Nonsuch with the Dutch Republic which promised to provide over 6000 regular troops for their army, to pay for one quarter of their defense budget, and to supply an experienced councilor to coordinate government in the rebel provinces and to lead their army. In return the Republic promised to surrender three strategic ports to England to serve as sureties until the queen's expenses were repaid after the end of the war.

The treaty came too late to save Antwerp, which fell on 17 August, but within a month (as Parma was quick to note) over 4000 English troops had arrived at Flushing, one of the three ports ceded by the treaty.37 Meanwhile, Drake's squadron of 25 ships (2 of them royal warships) and 8 pinnaces, carrying 1900 men (1200 of them soldiers) sailed from Plymouth on 24 September 1585. On 7 October they arrived off Galicia and for the next ten days raided several villages in the vicinity of Vigo and Bayona, desecrating churches, collecting booty, and taking hostages.38

Why exactly Drake chose to land in Galicia remains unclear, for neither his commission nor his instructions seem to have survived. Perhaps he needed to take on stores following a hasty departure from England; perhaps, as one of his officers later wrote, he wished to undertake some act of bravado "to make our proceedings known to the king of Spain."39 Either way, however, England's succession of aggressive acts--kidnapping the fishing fleet, issuing letters of marque, sending soldiers and subsidies under treaty to assist rebellious subjects, and now invading the peninsula- -could only seem to Philip II like a declaration of war.

Nevertheless, the responses among Spain's leaders to Drake's depredations varied. In Lisbon, the marquis of Santa Cruz drew up a memorandum of necessary defensive measures to prevent further attacks on the peninsula, to clear the seas of hostile vessels, and to safeguard Spanish America against the possibility that Drake might continue his depredations there.40 But Don Rodrigo de Castro, archbishop of Seville, roundly condemned the document as cravenly pusillanimous and in November complained bitterly to the government. What was the point, he inquired, of simply chasing after Drake, who was a fine sailor with a powerful fleet? Surely the best way to end the English menace was to attack England and, since Drake would probably be absent from home waters for some months, "if we are going to undertake such a campaign there will never be a better time."41 The king, who had already decided to accept the pope's invitation to conquer England, entirely agreed.

Philip II now commissioned his principal advisor on foreign affairs, Don Juan de Zúñiga, to prepare a thorough review of Spain's strategic priorities in the light of recent developments. Zúñiga identified four major enemies--the Turks, the French, the Dutch and the English--and reasoned that the Turks, although previously Spain's foremost problem, had committed so many resources to their struggle with Persia that a defensive posture would suffice in the Mediterranean, while the French, also once a major threat, were now so thoroughly mired in their own civil disputes that, although it might be necessary to intervene at some stage in order to prolong them, the cost to Philip II was unlikely to be high. This left the Dutch and the English. The former, it is true, had been a thorn in Spain's flesh since the rebellion of 1572 because every Spanish success seemed to be followed by some countervailing reverse; but at least the problem, although costly and humiliating, remained confined to the Low Countries. The English menace was quite different: it was new and it threatened the entire Hispanic world, for Elizabeth was clearly supporting the Dutch as well as Drake. Zúñiga insisted that England had now openly broken with Spain, and that "to fight a purely defensive war is to court a huge and permanent expense because we have to defend the Indies, Spain and the convoys traveling between them." An amphibious operation of overwhelming strength, he reasoned, therefore represented the most effective form of defense and also the cheapest. The diversion of resources to the Enterprise of England might temporarily compromise both the reconquest of the Netherlands and also the security of Spanish America; but Zúñiga felt the risk must be taken because, unless England were cowed, no part of Philip II's empire would be safe.42

The apparent wisdom of Zúñiga's analysis was soon demonstrated. On the one hand, the duke of Parma reported a massive build-up of English forces in Holland, paid for by English subsidies, culminating in December 1585 with the arrival of Elizabeth's favorite, the earl of Leicester, who was sworn in as Governor-General of the rebellious provinces. On the other, a constant stream of information poured back to Spain on the destruction caused by Drake: in the Canaries, in the Cape Verde Islands and finally in the Caribbean (where first Santo Domingo, then Cartagena and finally St. Augustine were all sacked). The new English colony at Roanoke (North Carolina) was also resupplied. Few of Philip II's subjects doubted that a direct attack on England now represented the only sure way to preserve the security of Spain, the Netherlands, and Columbus's legacy--the Americas and the "Spanish Lake." As the king put it:

Seeing how the English are taking over Holland and Zealand, and how they infest the Indies and the High Seas, it is clear that defensive measures no longer suffice to secure everything. Instead we need to put their own house to the torch, and in such a way that they will have to deal with it and abandon everything else.43

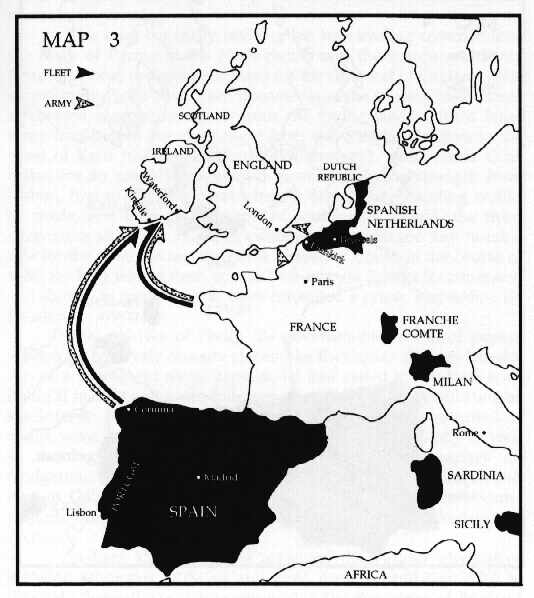

However it is one thing to decide that England must be "put to the torch," and quite another to make it happen. Given England's traditional strength by sea, experience has shown that (until the development of airpower) only four strategies offered reasonable prospects of a successful invasion [see maps 1-4].

The first consisted of a simultaneous combined operation by a fleet strong enough both to defeat the opposing English navy and to shepherd across the Channel an army sufficient to accomplish the conquest. William I in 1066 and William III in 1688 both employed this technique successfully; the French also attempted it in 1692, 1759 and 1779 but failed. The second possible strategy involved assembling an army in secret near the Channel while sending out a fleet from some other port as a decoy (to lure away the Royal Navy) so that a convoy of light and nimble transports could ferry the army across the Channel unescorted. Napoleon favored this ploy in 1804-5 but likewise failed. The third possible strategy represented a variant of the second: a diversionary assault on Ireland to lure away England's main defensive forces, leaving the mainland relatively open to invasion. The French (yet again) attempted this, with partial success, in 1760 and 1798. And, finally, a surprise assault might be essayed--witness Henry VII in 1485 (successfully), and Harald Hardrada in 1066 and the French in 1743-4 (both unsuccessfully).44

That all four possibilities received consideration in 1587-8 is a remarkable tribute to the vision and competence of Philip II and his "national security advisors"; that they tried to undertake three of them at once is a searing condemnation of Spain's methods of strategic planning.

The king began by inviting his two leading commanders, the duke of Parma in the Netherlands and the marquis of Santa Cruz in Lisbon, to devise warplans for the conquest of England. Not surprisingly, both men cast themselves in the starring role: Parma advocated a surprise attack from the Netherlands with a large army transported one dark night from the coast of Flanders to the coast of Kent (the fourth alternative strategy), while Santa Cruz called for an amphibious assault in overwhelming strength from Lisbon, first to the Irish coast where a diversionary landing would be made, and then on the coast of southeast England (the third alternative strategy). Neither commander envisaged any notable role for the other. When the plans arrived at Court, in the course of 1586, the king turned them over to Don Juan de Zúñiga for comment; and Zúñiga in turn seems to have consulted a priest, Bernardino de Escalante.

The archives of Philip II's government are full of papers written by relatively obscure clerics like Escalante. Born in Laredo, son of a prominent naval captain, he had sailed to England with Philip II in 1554 and spent fourteen months there before enlisting as a soldier in the Spanish Army of Flanders. He then returned to Spain, went to university and evidently studied geography as well as theology, for he later wrote two excellent treatises on navigation. After his ordination, he also served as an Inquisitor, first in Galicia and then in Andalucia, until in 1581 he became majordomo to the fire-eating archbishop of Seville, Don Rodrigo de Castro.

In June 1586 Escalante reviewed the various alternative invasion strategies in detail and even drew a campaign map to illustrate them--the only one concerning the Enterprise of England to survive [see plate 3]. First [on the left of the map] he noted that a fleet from Lisbon could undertake a daring voyage into the North Atlantic directly to Scotland, where it would regroup before launching its main attack ("The seas are high and dangerous," Escalante warned, "but through Christ Jesus crucified everything is possible"). An attack into the Irish Sea might be a second potential strategy although the Royal Navy, whose forces appear at the entrance of the English Channel, made this too a high risk operation. No less dangerous was a surprise attack from Flanders to Dover, and on to London (defended by "E Greet Tuura" [The Great Tower]). Escalante therefore suggested a combination of the two distinct strategies advanced by Santa Cruz and Parma. A Grand Fleet of 120 galleons, galeasses, galleys, merchantmen and pinnaces, cavalry, should be concentrated in Lisbon and then launched against either Waterford in Ireland or Milford Haven in Wales. At the same time the Army of Flanders was to be reinforced, first to tie down Leicester and the English expeditionary force in Holland and then to cross the Channel in small ships in preparation for a surprise march on London while Elizabeth's forces were occupied elsewhere.45

This ingenious scheme, backed up by a wealth of detail on the political and physical geography of the British Isles, clearly convinced Don Juan de Zúñiga because his own letter of advice to the king largely reiterated the plan proposed by Escalante. Zúñiga merely added the observation that, since Spain would gain no advantage from the direct annexation of England ("because of the cost of defending it"), the newly conquered realm should be bestowed upon a friendly Catholic ruler. He suggested Mary Stuart --but recommended that she should marry a more dependable Catholic prince, such as the duke of Parma.46

The king too was convinced, for on 26 July 1586 a "masterplan" was sent to both Brussels and Lisbon commanding the concentration of forces for a dual assault on the Tudor state [see map 5]. A formidable Armada would sail from Lisbon, carrying all available troops together with most of the equipment--above all a powerful siege train--needed for the land campaign, directly to Ireland. There it would put ashore assault troops and secure a beachhead, thus distracting Elizabeth's naval forces and neutralizing their potential for resistance when, after some two months, the Armada suddenly left Ireland and made for the Channel. At that point, and not before, the main invasion force of 30,000 veterans from the Army of Flanders would embark on the flotilla of small ships, assembled in secret, and leave the ports of Flanders under Parma's personal command for the coast of Kent while the Grand Fleet cruised off the North Foreland and secured local command of the sea. Parma's men, together with reinforcements and the siege train from the fleet, would then make a dash for London and seize the city--preferably with Elizabeth and her ministers still in it.

One wonders whether Philip II realized the full implications of this plan. In retrospect, Santa Cruz's proposal contained much merit. The events of 1588 proved that, once they got their Armada to sea, the Spaniards experienced little difficulty in moving 60,000 tons of shipping from one end of the Channel to the other, despite repeated assaults upon it. And the Kinsale landing of 1601 showed how easily an invader could secure and fortify a beachhead in southern Ireland. Likewise, Parma's concept of a surprise landing in Kent had much to recommend it: time and again, his troops had proved their invincibility under his leadership, and the largely untrained English forces, taken by surprise, would probably have succumbed swiftly to the Army of Flanders as it marched upon London. The Armada's undoing, and the loss of Spain's Atlantic hegemony, ultimately resulted from the decision to unite the fleet from Spain with the army from the Netherlands as an essential prelude to launching the invasion.47

Why did they do it? Zúñiga had played an outstanding role in coordinating the naval campaigns of the Mediterranean for almost twenty years, and Philip II had also participated in many victorious campaigns in the past, most notably the conquest of Portugal and the Azores between 1580 and 1583. But Philip II was merely an armchair strategist. He had virtually no firsthand experience of any form of military planning: technical, tactical, operational, theater or grand strategy were all a closed book to him. Worse still, he would not allow others to fill these critical gaps because Philip II's autocratic system of government ensured that no one else ever subjected the masterplan to critical scrutiny. Zúñiga, who had both the authority and the knowledge to raise objections, died in the autumn of 1586 and none of the king's other ministers--not even those involved in executing the plan--were allowed to demand how, precisely, two large and totally independent forces, with operational bases separated by more than a thousand miles of ocean, could attain the accuracy of time and place necessary to accomplish their link-up. Nor were the campaign commanders permitted to require an explanation of how the vulnerable and lightly armed barges collected in Flanders would evade the Dutch and English warships stationed offshore specifically to intercept and destroy them. Above all, no one could insist that there should be a "fall-back strategy" in case the junction of the two main components of the plan proved to be impossible.

For none of these prudent procedures formed part of Philip II's style of government. Instead, an aura of "messianic imperialism" pervaded policy-making at his Court. He and his ministers justified difficult political choices on the grounds that they were necessary not only for the interests of Spain but also for the cause of God; attributed victories to divine intervention and favor; and rationalized defeats and failures either as a Divine attempt to test Spain's steadfastness and devotion (thus providing a spur to future sacrifices and endeavors) or else as a punishment for momentary human presumption.48

Of course, an element of "providentialism" lurked in the strategic thinking of almost all states in the century following the Reformation, as religious and political issues became ever more tightly intertwined and the Bible served as a guide to secular as well as spiritual salvation. Most nations in this period regarded themselves as the new "Chosen People," enjoying a special relationship with God. Thus Philip II's arch-enemies, the English and the Dutch, also regarded their victories as the result of direct divine intervention; the inscription on a Dutch medal struck to celebrate the destruction of the Spanish Armada was typical: "God blew and they were scattered." Likewise they saw their History as pre-determined by Providence, and viewed their wars against Spain as a sort of "Protestant Crusade."49 But messianic sentiments ran far more strongly in Spain, where many felt that an inscrutable yet benevolent Providence had created the Habsburg empire through a complex sequence of dynastic accidents (by premature deaths and infertile unions as well as by judicious marriages) and had also led Columbus to America, Cortés to Mexico, Pizarro to Peru, and finally Philip II to Portugal and the Philippines--all to the greater glory of Spain and her rulers. Surely, then, that same Providence would in time humble France, defeat England and extirpate Protestantism? Friends and foes alike came to see the Spanish Monarchy as an almost supernatural force. More than all other states, wrote Tommaso Campanella, "it is founded upon the occult providence of God and not on either prudence or human force," its whole history resembling a heroic progression in which disasters--even the Moorish Conquest of 711 and, eventually, the Spanish Armada of 1588-- seemed mere episodes in Spain's inexorable (if somewhat erratic) advance toward world monarchy.50

Naturally this apocalyptic interpretation proved particularly popular among the numerous clerics who advised Philip II. Thus in 1571, the happy coincidence of the spectacular victory of Lepanto over the Turks and the birth of an heir to Philip II provoked a veritable torrent of letters from the king's chief minister, Cardinal Diego de Espinosa, drawing the attention of anyone who would listen to these indubitable signs of God's special Providence towards Spain "which leaves us with little more to desire but much to expect from His Divine mercy." Espinosa hailed Lepanto as "the greatest victory recorded since the drowning of Pharaoh's army in the Red Sea," while the king commissioned Titian, the foremost painter of the age, to produce a vast commemorative canvas of the two happy events (The Allegory of Lepan to). In Italy, many speculated that Philip would continue, with God's grace, to reconquer the Holy Land and revive the title emperor of the east";51 while the king himself resolved to persevere in his plan to invade England in support of the Ridolfi plot despite the arrest of the chief conspirators, because:

I am so keen to achieve the consummation of this enterprise, I am so attached to it in my heart, and I am so convinced that God our Savior must embrace it as His own cause, that I cannot be dissuaded. Nor can I accept or believe the contrary.52

The king only agreed to cancel the project, with great regret, two months later.

Philip II constantly equated his own interests, and those of the lands that he ruled, with those of God. Thus in the 1560s he refused to moderate his stand against heresy in the Netherlands because he claimed that "if the Catholic faith is lost, my estates will be lost with it"; and he urged his advisors "To tell me in all things what you think is best for the service of God, which is my principal aim, and so for my service." Before long, the two had become inseparable: "You are engaged in God's service and in mine-- which is the same thing," he reassured one of his dispirited commanders in 1573.53

This persistent belief in Spain's "manifest destiny"--that, in the contemporary phrase, "God is Spanish"54 --even influenced strategy on a practical level. In 1571 Philip II's correspondence concerning the proposed invasion of England saw the king at his most Messianic--and unrealistic. He freely admitted that his deep conviction that God was on his side "leads me to understand matters differently [from other people], and makes me play down the difficulties and problems which spring up; so that all the things that could either divert or stop me from carrying through this business seem less threatening to me."55 The same reptilian certitude about his divine mission to conquer England re-appeared in 1587-8. Philip II possessed total confidence that, at the critical moment, God would intervene directly to crown Spain's efforts with success in spite of all the odds. When, in 1587, Santa Cruz complained about the insanity of launching the Armada against England so late in the year, the king replied serenely:

We are fully aware of the risk that is incurred by sending a major fleet in winter through the Channel without a safe harbor, but... since it is all for His cause, God will send good weather.56In February 1588, when Santa Cruz's successor, the duke of Medina Sidonia, argued that the whole Armada venture was ill-conceived and almost inevitably doomed to failure, he received the rebuke: "Do not depress us with fears for the fate of the Armada, because in such a cause God will make sure it succeeds." A few months later, when a storm damaged some of the ships, drove others into Corunna, and scattered the rest, Medina Sidonia suggested that these reverses might be a sign from God to desist; but the king replied confidently:

If this were an unjust war, one could indeed take this storm as a sign from Our Lord to cease offending Him; but being as just as it is, one cannot believe that He will disband it, but rather will grant it more favor than we could hope."I have dedicated this enterprise to God," the king concluded briskly. "Get on, then, and do your part!"57 Upon such rocks of blinkered intransigence, rational calculations of Spain's strategic advantage foundered.

And yet, for all its faults, Philip II's Grand Design for the conquest of England did come within an ace of success, even though circumstances dictated certain changes in his original plan. In the first place, the execution of Mary Stuart in February 1587 threw wide open the question of who should succeed Elizabeth after the Spanish conquest. Armed with family trees and dynastic treatises, Philip II at first claimed to be the lawful heir to the English throne by virtue of his descent from the house of Lancaster. In the end he was dissuaded from making this public and instead accepted that, subject to papal approval and investiture, he could nominate a ruler of his choice to restore and uphold the Catholic faith.58 Next, in April 1587 Queen Elizabeth, goaded by news of Philip II's preparations by both land and sea, launched Sir Francis Drake on what today would be called a "pre-emptive strike" and was then known as "the singeing of the king of Spain's beard." Neither the sack of Cadiz nor even the destruction of stores and ships proved critical; but Drake's subsequent--and well-publicized--departure to intercept the returning Portuguese and American treasure galleons forced Santa Cruz to take the Armada to sea in July, not against England, but to await the returning fleets off the Azores. Although the marquis accomplished this feat brilliantly, losing just one East Indiaman to Drake, he only returned to Iberian waters in October, with storm-damaged ships and sick men. As a consequence, the Enterprise of England could not take place in 1587 and Spain's Grand Strategy required rethinking.

Philip II worked hard. On 14 September he issued a new masterplan. It contained no word of invading Ireland; instead Santa Cruz received orders to sail with the entire fleet "in the name of God straight to the English Channel and go along it until you have anchored off Margate head." It would there form a protective screen off the Thames to prevent the English fleet from interfering with Parma's barges as they sailed from the ports of Flanders to the beaches of Kent. The fleet would send advance warning of its approach, so that Parma "will therefore be so well prepared that, when [he] finds the narrow seas thus secured, with the Armada riding off the said headland or else cruising off the mouth of the Thames,... [he] will immediately send the whole army over in the boats [he has] prepared." And Parma, for his part, was commanded not to stir from the Flemish coast until the fleet arrived. But of precisely how the army in its barges was to reach the security of the fleet, there was still not a word. It was, to say the least, an unfortunate oversight.

But perhaps the king did not think it mattered, for he had two more diplomatic tricks up his sleeve: the simultaneous paralysis of both France and the Dutch Republic. At a meeting with the Spanish ambassador in late April 1588 the duke of Guise, acting on behalf of the Catholic League, agreed to engineer a general rebellion in France the moment he heard of the Armada's departure. The immediate payment of 100,000 crowns in gold to the League's leaders clinched the deal. Guise, however, was no longer able to control the enthusiasm of his subordinates, and early in May the Paris Catholics began to agitate for a takeover of the city. When, on 12 May 1588, Henry III deployed his Swiss Guards to preserve order, the entire city erupted into violence, erecting barricades against the king's troops and forcing him to flee from his capital. The "Day of Barricades" made Guise the master of Paris and shortly afterwards he became "lieutenant-general of the kingdom."

Philip II's support for the French Catholic League since 1585 had thus paid handsome dividends. Admittedly he had intended that Guise should capture Henry III and force him to make concessions--including free access to ports such as Boulogne and Calais--as the Armada entered the Channel. But even without that crowning achievement the towns of Picardy as well as Paris remained in League hands, and friendly forces now held the Channel ports.

Spain's diplomacy also ensured--rather more surprisingly-- that the Dutch rendered precious little aid to England. As rumors of Spain's imminent invasion multiplied, Elizabeth began serious negotiations for a ceasefire with a team of diplomats that Philip II and Parma had graciously supplied. The queen begged her Dutch allies to join her in the talks and, when they refused, the English troops in the Netherlands attempted to seize a number of strategic towns in the Republic. They failed, but England was now totally discredited. Nevertheless Philip ordered the talks with Elizabeth's diplomats to be prolonged and authorized his agents to hint at concessions. To his delight, the English took the bait-- sending commissioners to Ostend (a town loyal to the States- General) in February 1588; moving to Spanish territory at Bourbourg (near Dunkirk) in May; even allowing one of their number, Sir James Croft, to discuss terms for English withdrawal from the Netherlands. Spanish propaganda made much political capital out of "perfidious Albion" with the already suspicious Dutch. It is true that Elizabeth also gained something from the talks (above all an observation post in Flanders from which to monitor Parma's military preparations), but she lost far more by forfeiting the trust of the Dutch. In the end, the blockade squadron of Justinus of Nassau--a mere 35 ships, all of them small and lightly gunned-- only took up station off the Flanders coast in July 1588.59

A few days later, on 6 August 1588, following Philip II's simplified masterplan, a Grand Fleet of some 125 vessels carrying some 18,000 soldiers, "the greatest and strongest combination that ever was gathered in Christendom" (as even the English admitted), dropped anchor off Calais. Only 25 miles away, 30,000 veterans of the Army of Flanders began to embark on the 215 ships and barges prepared for them in the harbors of Dunkirk and Nieuwpoort according to the meticulous schedule drawn up by the duke of Parma. Meanwhile, from their anchorage off Calais, where they received welcome provisions from the benevolent Catholic governor, the men aboard the fleet could almost make out the designated landing-place just south of Ramsgate, where the Romans, the Saxons and the Danes had all landed successfully in the past.

With England diplomatically isolated and France in friendly hands, anything could have happened at this point; and for the next thirty-six hours, until the daring English fireship attack (which disordered the fleet's combat order) and their even more daring close-range gunnery assault on 8 August 1588 (which drove it far from the rendezvous off the coast of Flanders), the fate of Columbus's legacy hung in the balance. Had either of the English stratagems miscarried, Parma would have had time to march his forces down to the waiting fleet; or had the wind suddenly changed, blowing the Dutch blockade squadron off station (as in fact happened a few days later), Parma's flotilla (perhaps escorted by the heavily-gunned, shallow-draft galeasses) could have put to sea. In either case, an independent, Protestant England could scarcely have survived.

The potential consequences of the Armada's victory should not be underestimated. Had England been conquered and Catholicized, the Dutch Revolt would have swiftly collapsed; while with France controlled by a grateful Catholic League and entirely surrounded by Habsburg states, it too would surely have become a Spanish satellite. Only Iberian colonies would have flourished in North America; Portugal and her empire would have been gradually integrated into a single Iberian superstate; Van Diemen and Cook would have claimed Australasia for the Catholic Church; and--more practically--we would have celebrated Columbus Day on October the 23rd, according to the Gregorian Calendar, instead of eleven days too early!

But of course the tactical flair of Elizabeth's admirals and the technological superiority of her ships produced a different outcome. Instead of the victory he expected, restoring to his empire the security and prosperity that had been under threat for twenty years, Philip II's overambitious enterprise (which culminated in the destruction of almost half his fleet and the death or disgrace of almost all his senior naval officers) provoked a succession of ever- larger raids on Spain's Atlantic shipping and overseas colonies by the English and, slightly later, by the Dutch. From Florida to the Straits of Magellan and back to California, Spain was forced to spend prodigiously on state-of-the-art defenses against the new maritime threat; the extant colonial fortifications of Cartagena, San Juan de Puerto Rico and scores of other sites testify to the size of the undertaking. The Pacific too now required fortifications--as at Manila and Cebu--so costly that by 1620 the royal treasury in Mexico was obliged to send more silver to finance the defense of the Philippines than it remitted back to Spain.60 Barely a century after Columbus, thanks to the failure of the Armada, the era of "Spanish lakes" had gone forever and, although the southern and central parts of the American continent remained under Iberian control for another two centuries, control over the areas to the north gradually passed to the victors of 1588.

Notes

1. Unless otherwise stated, all dates in the text and notes are given New Style. I should like to thank Edward N. Luttwak, John A. Lynn and Williamson A. Murray for helpful suggestions on the study of early modern strategy; and also Professor Emeritus Lawrence F. Brewster for the generosity that made possible the presentation and publication of this lecture.

2. The John Carter Brown Library at Providence (RI) now owns the atlas: see the facsimile edition by C. Wiener and F. Spitzer, Portulan de Charles-Quint donné à Philippe II (Paris, 1875). An excellent reproduction may be found in the endpapers of J.H. Elliott, Spain and its world 1500-1700. Selected essays (New Haven, 1989). See also H.R. Wagner, "The manuscript atlases of Battista Agnese," Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, 25 (1931): 74-5. Some 70 Agnese "atlases," almost all of similar design, have survived.

3. The best account of Drake's achievements is still K.R. Andrews, Drake's voyages (London, 1967). For the English in the Caribbean (and elsewhere) after 1585 see Andrews, Elizabethan privateering. English privateering during the Spanish War, 1585-1603 (Cambridge, 1964).

4. Quotations from R. W. Johannsen, A new era for the United States: Americans and the war with Mexico (Urbana, 1975), 16.

5. On the growth of the Mediterranean fleet see the table in C. Parker, Spain and the Netherlands 1559-1659. Ten essays (London, 1979), 130; on the development of an Atlantic fleet see the data provided by J. L. Casado Soto and I. A. A. Thompson in M. J. Rodriguez Salgado and S. Adams, eds., England, Spain and the Gran Armada 1585-1604. Essays from the Anglo-Spanish conferences, London and Madrid, 1988 (Edinburgh, 1991), 70-133, especially pp. 70f. and 98f. On Spain's Atlantic fleet, see I. A. A. Thompson, War and government in Habsburg Spain, 1560-1620 (London, 1976), part iii; S. H. Barkman, "Guipúzcoan shipping in 1571" in Anglo-American contributions to Basque studies: essays in honor of Jon Bilbao (Reno, 1977), 73-81; and M. Pi Corrales, Felipe II y la lucha por el dominio del mar (Madrid, 1989).

6. Spain had in fact managed to send battle squadrons into the North Sea in the 1550s, especially in conjunction with the Royal Navy while Philip II was king of England; but by 1572 the capacity had been lost. See J. L. Casado Soto, Los barcos españoles del siglo XVI y la Gran Armada de 1588 (Madrid, 1988), 35-44.

7. Two expeditions sailed to regain Florida, the first of 8 ships in 1565 and the second of 17 ships in 1566: see E. Lyon, The enterprise of Florida. Pedro Menéndez de Avilés and the Spanish conquest of 1565-8 (Gainesville, 1976). Even this venture cost 275,000 ducats (op. cit., 181-3). See also the documents concerning the embargo of 47 ships for the king's planned expedition to Flanders in 1567 quoted in C. Parker, The Dutch Revolt (3rd ed., Harmondsworth, 1984), 292 n. 28, and the accounts in A[rchivo] G[eneral del S[imancas] Contaduria del Sueldo, 2a Epoca 197.

8. The best discussion of the implications of the Tudor marriage is H. Lutz, Christianitas Afflicta. Europa, das Reich, und die päpstliche Politik im Niedergang der Hegemonie Kaiser Karls V. 1552-1556 (Göttingen, 1964), 208-9: he notes that it not only affected France, but also Charles's brother Ferdinand because it ended all hope that the latter might inherit the Netherlands and made it clear that the Spanish Habsburgs would be more powerful than their Austrian cousins.

9. A[rchivo de la Casa de] M[edina] C[eli, Seville,] 7/249/11-12, Philip II to the count of Feria, his ambassador in London, 10 and 28 January 1559, holograph. In fact Elizabeth seems to have broached the subject of marriage to Philip II herself in December 1558, almost immediately after her succession: see M. J. Rodríguez Salgado, The changing face of empire. Charles V, Philip II and Habsburg authority 1551-1559 (Cambridge, 1988), 319.

10. AMC 7/249/12, Philip II to Feria, 21 March 1559, holograph.

11. See the important essays of C. Haigh and R. Hutton in C. Haigh, ed., The English Reformation revised (England, 1987) demonstrating the lack of any spontaneous moves towards Protestantism in 1558-9 except in the Home Counties.

12. P.0. de Törne, Don Juan d'Autriche et les projets de conquête de l'Angleterre. Etude historique sur dix années du seizième siècle, 2 vols. (Helsingfors, 1915-28) 1: 7-18. On the embargo of 1563-5 see G. D. Ramsay, The city of London in international politics at the accession of Elizabeth Tudor (Manchester, 1975), passim; and G. E. Wells, "Antwerp and the government of Philip II 1555-67" (Cornell University Ph.D. thesis, 1982), 277-300.

13. J. Calvar Gross, J. I. González-Aller Hierro, M. de Dueñas Fontán and M. del C. Merida Valverde, [La] B[atalla del] M[ar] O[céano], 2 vols. (Madrid, 1988-9), 1:1-4, Instructions to Spes, 28 June 1568.

14. For details see C. Read, "Queen Elizabeth's seizure of the duke of Alba's payships," Journal of Modern History, 5 (1933): 443-64; and the documents printed in BMO, 1:6-78.

15. Interestingly, the king still balked at sending direct aid to Mary: in August 1571, just when he expected Ridolfi to act, Philip forbade Alba to send troops to assist Mary's cause in Scotland "in order to avoid open war with the queen of England." The duke only received authorization to provide money to Mary's Scottish supporters: Algemeen Rijksarchief, The Hague, le Afdeling: Spaanse-Nederlandse Regering te Brussel 14B/14, Philip II to Alba, 30 August 1571.

16. P. Collinson, The English captivity of Mary Queen of Scots (Sheffield, 1987), 42f.: Cecil to the earl of Shrewsbury, Mary's custodian, 5 September 1571. It should be noted that earlier that same day the government arrested the duke of Norfolk--on whom the success of the Ridolfi plot depended--and sent him to the Tower.

17. M. Pi Corrales, España y las potencias nórdicas. "La otra invencible" 1574 (Madrid, 1983), 191-6, "Relación de los navios... que se junta en Santander" (31 May 1574). There is an interesting parallel here with the dramatic strategic changes made to the "Enterprise of England" in 1585-8: see G. Parker, The Grand Strategy of Philip II (New Haven, forthcoming), chap. 6.

18. See the documents cited in Pi Corrales, España, 89, 103, 181-4.

19. I[nstituto de] V[alencia de] D[on] J[uan, Madrid,] 53 carpeta 3/64, the king to Mateo Vázquez, 17 May 1574.

20. "More than half a million" spent on the "Armada de Santander" in the course of 1574 was the figure given by the President of the Council of Finance: IVDJ 24/103, "Parecer de Juan de Ovando," 25 Mar. 1575. Other details on the fleet from Pi Corrales, "La otra invencible," chaps. 5-10.

21. P[ublic] R[ecord] O[ffice, London] S[tate] P[apers] 12/105/123, Walsingham to Burghley, 6 October 1574, reporting the arrival of "48 sayle of Spanyshe men of warre" off the coast of Devon. For some time panic gripped the English government: see the documents assembled by R. Pollitt for the Navy Records Society (forthcoming). In the event, a real Spanish naval presence in the North Sea only came in the seventeenth century: see R. A. Stradling, The Armada of Flanders. Spanish maritime policy and European war, 1568-1668 (Cambridge, 1992).

22. B[ibliothèque] N[ationale de] P[aris], Fonds français 16108/425-7, M. de St Gouard to Henry III, 7 October 1582.

23. BMO 1: 395f, Santa Cruz to Philip II, 9 August 1583 (see also the king's reply dated 23 September, ibid., 406.) By a curious coincidence, Pope Gregory XIII attempted at precisely this moment to rekindle the king's interest in invading England: see ibid., 406-9, Philip II to the count of Olivares, his ambassador in Rome, 24 September 1583 (with supporting documents), in reply to the pope's letter of 16 August proposing the enterprise of England.

24. Details from E. G. R. Taylor, ed., The troublesome voyage of Captain Edward Fenton 1582-3. Narratives and documents (Hakluyt Society, 2nd series, vol.113, London, 1959); and E. S. Donno, ed., An Elizabethan in 1582. The diary of Richard Madox, Fellow of All Souls' (Hakluyt Society, 2nd series, vol.147, London, 1976), especially p. 151.

25. BMO 1:405f., Philip II to Parma, 12 September 1583.

26. BMO 1:478, royal apostil on Olivares to Philip II, 4 June 1585.

27. AGS Estado 946/85-8 and 103f., Olivares to Philip II, 13 July (about the "empresa de Ginebra") and 28 July 1585; BMO 1:496 and AGS Estado 946/229 Philip II to Olivares, 2 and 22 August 1585. See also G. Altadonna, "Cartas de Felipe II a Carlos Manuel II duque de Saboya (1583-96)," Cuadernos de investigación histórica, 9 (1986), 157: Philip II to the duke of Savoy, 23 August 1585, approving the idea of an assault on Geneva as suggested by the pope.

28. BMO 1:527-8 and 536-7, Philip II to the pope and the Grand Duke of Tuscany, 24 October 1585, and "Lo que se responde a Su Santidad." The editors of BMO assert that Dovara's project concerned a Spanish attack on Algiers, but this is nowhere stated in the documents they print. By contrast, the instructions issued on 28 February 1585 to Dovara (A[rchivio di] S[tato] F[lorence] Mediceo del principato 2636/123f.), and Dovara's correspondence with the Grand Duke (ASF Mediceo 5022/357ff.) makes it clear that the "empresa" referred only to England. See also AGS Estado 1452/20, Philip II to Grand Duke, 27 July 1585.

29. See Parker, Dutch Revolt, 197, 205-7; and M. P. Holt, The duke of Anjou and the politique struggle during the wars of religion (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 157-9.

30. Anjou's mother, the perceptive Catherine de Medici, thought that the death of Anjou and Orange would facilitate Philip II's victory in the Netherlands: see BNP Cinq Cents Colbert 473/589, Catherine to Michel de Castelnau, 25 July 1584 (my thanks to Dr. Mack P. Holt for this reference).

31. See PRO SP 83/23/59f. "The resolution of ye conference had upon the question of whyther hir Majesty shuld presently releve the States of ye Low Countryes of Holland and Zelland or no" (holograph notes by Lord Burghley). See also ibid., fos 49-58 and 61.

32. PRO SP 83/23/115-17, Elizabeth's Instruction to William Davidson, 13 November 1585 OS; and N. Japikse, Resolutiën der Staten Generaal van 1576 tot 1609 (The Hague, 1919), 4:515, Resolution of 8 December 1584 on Davidson's offer.

33. B[ritish] L[ibraryj Harleian Ms. 168/102-5, "A consultacion... touchinge an aide to be sent in to Hollande againste the king of Spaine" (18 March 1585 0S). See the excellent account of the tortuous negotiations in F. G. Oosterhoff, Leicester and the Netherlands 1586-87 (Utrecht, 1988), 38-40. On the disunity of the Republic at this time see A. van der Woude, "De crisis in de Opstand na de val van Antwerpen," Bijdragen voor de Geschiedenis van Nederland, 14 (1959-60): 38-57 and 81-104.

34. The total cost was estimated at £40,000, of which the queen agreed to contribute almost half in cash and ships. PRO SP 12/46/159, 171 and 178 document the issues of money in 1584 (with copies in PRO Audit Office 1/1685/20A, plus receipts for payment, starting with £3500 paid to Drake in August 1584); BL Lansdowne Ms 41/9 Burghley memorandum "The charge of the voyage to the Moluccas", 24 November 1584 OS.

35. PRO SP 12/179/48, Commission to Bernard Drake, 20 June 1585 OS, copy; SP 12/180/40 "Articles set downe... for the marchantes, owners of shippes and others whose goodes have ben arrested in Spaigne," 9 July 1585 0S. Rodríguez Salgado and Adams, England, 46, note that letters of reprisal began to be issued three days later.

36. PRO SP 46/17/160, Warrant of Elizabeth I, 1 July 1585 0S, and fo. 172, Privy Council warrant, 11 July 1585 OS. Piecing together the history of Drake's expedition is complicated by the absence of the Privy Council Register for 1582-86.

37. See Oosterhoff, Leicester, 39-45.

38. For details see AGS Guerra Antigua 179/87, Licenciado Antolínez to Philip II, 14 November 1585. For the English side, see M. F. Keeler, Sir Francis Drake's West Indian Voyage 1585-86 (London, 1981: Hakluyt Society, 2nd series, Vol.148).

39. See the discussion of motives and sources in Rodríguez Salgado and Adams, England, 59.

40. BMO 1: 529-31, "Memorial" sent by Santa Cruz to Philip II, 26 October 1585.

41. IVDJ 23/385, "Parecer del Cardenal de Sevilla sobre lo del cosano" (15 November 1585), forwarded to Philip II by Hernando de Vega, President of the council of the Indies, on 30 November. This and the preceding document are discussed in the excellent article of A. Gonzalez Palencia, "Drake y los orígenes del podeno naval inglés," in F. Perez Minguez, ed., Reivindicación histórica del siglo XVI (Madrid, 1928), 281-320.

42. IVDJ 32/225, "A su magestad, del Comendador Mayor" (undated, but late 1585; holograph). Zúñiga had handled all the papers concerning Drake's raid on Galicia: see BMO 1:521 (document 461).

43. G. Maura Gamazo, duke of Maura, El designio de Felipe II y el episodio de la Armada Invencible (Madrid, 1957), 167, Don Juan de Idiáquez to the duke of Medina Sidonia, 28 February 1587. For other similar views, see Pérez Mínguez, Reivindicación, 308, and C. Martin and G. Parker, The Spanish Armada (London, 1988), 118.

44. I am grateful to Paul C. Allen for discussing this point with me. For the history of two spectacular failures, see P. Aubrey, The defeat of James Stuart's Armada, 1692 (Leicester, 1979), and A. T. Patterson, The other Armada: the Franco-Spanish attempt to invade Britain in 1779 (Manchester, 1960). Although all France's invasion attempts in the eighteenth century failed, they did temporarily hamper British intervention on the European continent: see the perceptive remarks of J. M. Black in M. Duffy, ed., Parameters of British Naval Power 1650-1850 (Exeter, 1992), 44f and 115.

45. On Escalante see the introduction to B. de Escalante, Diálogos del arte militar (Seville, 1583: 2nd edn., ed. J. L. Casado Soto and G. Parker, Laredo, 1992). The "Discurso" of June 1586 is printed in BMO 2:207-11.

46. BMO 2:212, "Parecer" of Don Juan de Zúñiga ('une/July 1586).

47. It is interesting to note that precisely the same error was made in 1779: the success of the invasion hinged not only upon joining together fleets from several ports (Toulon, Cádiz, Brest...) but also upon picking up an army stationed in two different ports (St Malo and Le Havre).

48. See the classic discussion of the origins of Spanish "messianic imperialism" in the 1520s in M. Bataillon, Erasmo y España: Estudios sobre la Historia Espiritual del Siglo XVI (2nd ed., Mexico, 1950), 226-31; and F. Yates, Astraea. The Imperial Theme in the Sixteenth Century (London, 1975), 1-28.