The Demise of the Interurban

Version #1: The interurban had its heyday as long as its technological development stayed ahead of that of the automobile. Once the automobile became an effective vehicle it meshed with the American spirit of individualism. State and municipal governments were forced to yield to public demand and shift funds from the development and maintenance of interurban cars and lines and shift to paving roads.

Version #2: The interurban was an effective competitor of the automobile and heavy locomotive for quite awhile. This ended when powerful companies conspired to bring the interurban era to an end in favor of diesel buses, diesel trains, and the automobile. At the end of the day the American people are consumers and can only purchase what large corporations offer to sell them.

While the first version is basically the story of the demise of the interurban in many places, the second version is more true elsewhere. Where competition and general economic factors were not enough to kill off the interurban, monopolistic practices by industry behemoths did the rest.

Robert Snell provides the teeth for Version #2. In 1974 Snell testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee's Subcommittee on Antitrust and Monopoly in favor of breaking up the Big Three automakers. At the time of his testimony the United States was crippled by the energy crisis. All across the nation Americans were waiting in long lines to put gas into their big American cars. Snell testified that, led by General Motors, the American auto industry had engaged in monopolistic practices for decades that were not good for the nation.

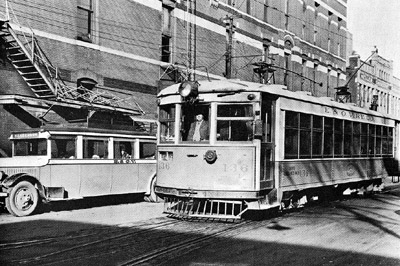

| Among these monopolistic practices was what Snell called "dieselization." This was a strategy of purchasing electric transit systems and either closing them down or placing a financial tourniquet on them. Left to rust, shiny new diesel buses and automobiles seemed quite attractive. A bus and an interurban pose side-by-side to the right. |  |

GM's destruction of electric transit systems across the country left millions of urban residents without an attractive alternative to automotive travel. Pollution-free rail networks, with their private rights of way, were vastly superior in terms of speed and comfort to smoke-belching, rattle-bang GM buses which bogged down with cars and trucks in traffic...To prevent the cities it motorized from rebuilding rail systems or buying electric buses, GM and its highway allies prohibited them by contract from purchasing "any new equipment using any fuel or means of propulsion other than gas." Ultimately, the diesel buses drove away patrons and bankrupt bus-operating companies. (Snell 1868)

Snell focuses much of his testimony on Los Angeles. He states that "what happened there was not unique. GM was involved in the ruin of more than 100 electric rail and bus systems in 56 cities, including New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore. St. Louis, Oakland, Salt Lake City, Lincoln, Nebr., and Los Angeles" (1844).

What happened to this region? General Motors, Standard Oil of California, Firestone Tire, and others, organizing holding companies which scrapped the pollution-free electric trains, tore down the power transmission lines, ripped up the tracks, and placed GM motor buses, fueled by Standard Oil and equipped with Firestone Tires, on every L.A. street.The extent of American government's disaffection with this situation is personified in Senator Roman Hruska who was quite belligerent with Snell during the hearing. After Snell had explained the Los Angeles situation in much greater detail than we have here, the senator still did not quite understand.

Sen. Hruska: When nobody would ride them anymore, and couldn't because streetcar tracks didn't reach into suburbs, then no longer did they keep the streetcar companies.

Snell: I'd like to point out that the Pacific Electric not only reached to the suburbs but it connected distant cities and that, in fact, there was no decline in patronage in 1940 when General Motors acquired the rails; they were moving 80 million passengers a year.

Sen. Hruska: How much of an expanse is covered by that map? What is the easternmost terminal?

Snell: Seventy-five miles.

Sen. Hruska: Seventy-five miles?

Snell: That's correct.

Sen. Hruska: Isn't that wonderful. And yet it wasn't enough. It folded, didn't it?

Snell: It didn't fold, Senator; it was acqired by General Motors and its auto-industrial allies and destroyed.

Sen. Hruska: What?

Snell: It did not fold. It was acqired by General Motors and other industrial interests and destroyed.

Sen. Hruska: And what did they do with it?

Snell: They destroyed it.

Sen. Hruska: They destroyed it?

Snell: Yes.(1857)

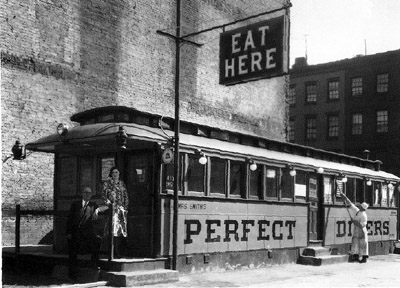

In recent decades new electric commuter "light rail" systems have revived the spirit of the interurban. For example, the Washington area "Metro" fits Hilton's definition almost perfectly (it goes underground in the city rather than running on streets). What is left of the old interurban cars? Many have been preserved for nostalgia in museums, many of which still run on closed loops. Others have been converted to homes or diners (left). Their heyday lasts only in photos and the stories of those who remember the interurban era.

In recent decades new electric commuter "light rail" systems have revived the spirit of the interurban. For example, the Washington area "Metro" fits Hilton's definition almost perfectly (it goes underground in the city rather than running on streets). What is left of the old interurban cars? Many have been preserved for nostalgia in museums, many of which still run on closed loops. Others have been converted to homes or diners (left). Their heyday lasts only in photos and the stories of those who remember the interurban era.