In the last decades of the nineteenth century

Native Americans suffered countless assaults and indigneties under a brutal, and

congressionally mandated, program aimed at incorporating the Native American into

mainstream America. This period, known as the Gilded Age, was in fact the age of

incorporation, a time when developments like the railroad and the telegraph made the vast

United States a smaller and more manageble place. Americans were introduced to national

brands, national corporations, and national pastimes as they developed an increasingly

incorporated national culture. The message sent by the White City at the Columbian Fair of

1893, "the first expression of American thought as unity," represented the

fulfillment of an incorporated American culture(Trachtenberg 220).

Not all Americans shared in this unity of thought. Chief Simon Pokagon, whose

family had originally owned the section of Chicago upon which the White City was built,

wrote the "Red Man's Rebuke" in order to vent his frustration at lack of

representation accorded to the first Americans. As thier relative absence from the Fair's

exhibits suggests Native Americans remained unincorporated in the age of incorporation.

Yet in this generic age mainstream white America worked

hard to force Native Americans to assimilate and take thier place among the already

incorporated. The experience of the Native American in this period, a time defined by the

massacre of hundreds at Wounded Knee

and the assassination and imprisonment of thier leaders most notably Crazy Horse and Geronimo, illustrates the extreme nature of the

forced assimilation of thier culture.

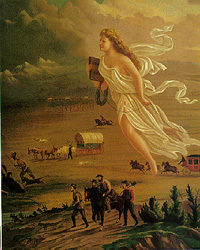

As John Gast's painting "American Progress"(shown above)

suggests the traditional Native American, a dying breed even at the onset of the Gilded

Age, remained cast as the "savage other," the outsider, and signified, to the

agents of incorporation, a road block to the "grand drama of progress." Native

American warriors like Sitting Bull, Chief Joseph, and

Geronimo remained the enemies of incorporation.

Native Americans represented a special problem to those who sought

to incorporate the west and saw the land as a resource to be exploited. In The Incorporation of America

Alan Trachtenberg explains the problem posed by Native Americans to the agents of

incorporation: "The Indian projected a fact of a different order from land and

resources: a human fact of racial and cultural difference not as easily incorporated as

minerals and soil and timber"(27).

Thus in the Gilded Age white Americans were increasingly interested

in solving the so-called "Indian problem and attempted through various means to

figure out "how to get rid of it in the easiest and quickest way possible, and to

bring the Indian and every Indian in to" their incorporated culture.

The agents and agencies of incorporation took various forms. In 1887

the movement to forcibly incorporate the Native Americans was legalized when Congress

passed the Dawes Severalty or General

Allotment Act. The Dawes Act offered Native Americans a choice between thier own

legally sanction extinction and incorporation. It, according to Alan Trachtenberg:

| "implied a theory and pedagogical vision of America

itself.....manifested in practical terms. To every male Indian 'who has voluntarily taken

up ....his residence apart from any tribe... and has adopted the habits of civilized[read

white] life,' the act offered not only an allotment of land for private cultivation but

the prospect of full American citizenship. It offered a choice: either abandon Indian

society and culture, and thus become a 'free' American, or remain an Indian socially and

legally dependent.

|

NEXT: THE NATIVE AMERICAN IN POPULAR CULTURE