Wages and Rents

|

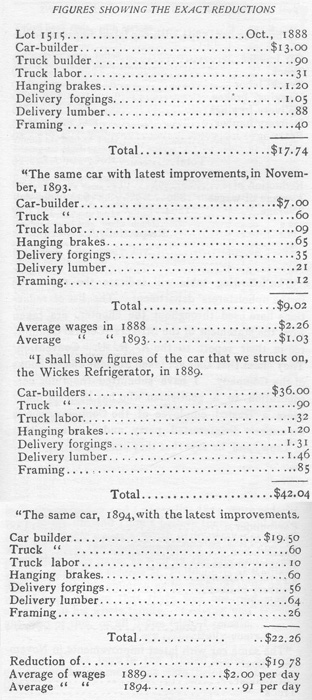

In the town of Pullman all the land, elaborate buildings, and humble homes were owned by the company. Everything, even the church, was rented out at prices so high that no one could afford to pay them. Richard T. Ely wrote in 1885 that rents in Pullman were three-fifths what they were in Chicago. Mr. Pullman stated that the average rental was $3.00 per room. However, the average of actual rents paid and the true number of houses rented was much higher than $3.00. Adding water and gas to the bill, a seven-room Pullman cottage rented for $28.96; the same house in Chicago was $18.00 to $20.00. As a Kensington real estate dealer wrote to Mr. Pullman: In a publishment of a recent interview with you it is stated that your renting department charges rents in Pullman in competition with rents in the adjoining towns of Kensington, Roseland, and Gano. If you sincerely believe this to be true, it would be well for you to personally investigate, as with my six years' experience in the renting business, I know it to be a positive fact that flats and cottages containing parlor, dining-room, two bedrooms and kitchen, with use of water and yard, have been and are rented for $10 and $12, for which similar accomodations you charge $16 and $18 at least." Higher rents might have been a small price to pay to live in a town surrounded by beauty and a corporation that did everything. However, workers were afraid to seek cheaper housing off Pullman grounds because the company gave preference to Pullman residents. In the beginning workers earned a fair wage. Yet by August of 1893, Mr. Pullman began cutting wages and laying off workers in response to a general depression of trade. The average cut in wages was 33 percent. In many cases, however, it was 40 to 50 percent. Workers' wages were reduced without subsequent reductions in rents. In many cases, workers could not even work full-time at the reduced wages, but were still expected to pay rent in full and on time.

In fact, the entire financial burden of the depression was carried by the workers. There were no wage cuts for managers or personnel and there were no reductions in stockholder dividends. There was a rent reduction--for shopkeepers only. Yet as Rev. Carwardine stated, the Pullman Palace Car Company at the time of the strike had a $27,000,000 surplus, capitalization of $30,000,000 and a quarterly dividend of $600,000 in three months. |