|

|

|

| P R I N T E R - F R I E N D L Y F O R M A T | Return to Article |

D-Lib Magazine

July/August 2016

Volume 22, Number 7/8

Analysis of International Linked Data Survey for Implementers

Karen Smith-Yoshimura

OCLC Research

smithyok@oclc.org

DOI: 10.1045/july2016-smith-yoshimura

Abstract

The International Linked Data Survey for Implementers conducted by OCLC Research in 2014 and 2015 attracted responses from 90 institutions in 20 countries. This analysis of the 112 linked data projects or services described by the 2015 respondents — those that publish linked data, consume linked data, or both — indicates that most are primarily experimental in nature. This article provides an overview of the linked data projects or services institutions or organizations have implemented or are implementing, what data they publish and consume, the reasons respondents give for implementing linked data and the barriers encountered. Relatively small projects are emerging and provide a window into future opportunities. Applications that take advantage of linked data resources are currently few and are yet to demonstrate value over existing systems.

1 Introduction

The impetus for an "International Linked Data Survey for Implementers" was discussions with OCLC Research Library Partner1 metadata managers who were aware of some linked data projects or services but felt there must be more "out there" that they should know about. The survey instrument was designed in consultation with OCLC colleagues and a few OCLC Research Library Partners and beta tested by several linked data implementers. We conducted the initial survey in July and August 2014, distributing the link to the survey on multiple listservs and on Twitter. The target audience were those who had already implemented a linked data project or service, or were in the process of doing so. Questions were asked both about publishing linked data and consuming linked data. The results were published in a series of posts on the OCLC Research blog, HangingTogether.org.2

While the initial survey results received a generally appreciative response from readers, some noted and regretted the absence of several prominent linked data efforts in Europe. To address these gaps, we repeated the survey on 1 June 2015, with responses due by 31 July 2015.

2 Overview

Seventy-one institutions responded to the 2015 survey, compared to 48 in 2014. 29 responded to both, with a total of 90 responding institutions in 20 countries (see the list appended at the end of this article). Respondents from the US accounted for 43% of the total with 39 responses, followed by Spain (10), the United Kingdom (9) The Netherlands (6), Norway (4), and Canada (3). We received 2 responses each from Australia, France, Germany, Italy and Switzerland, and 1 response each from Austria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Ireland, Japan, Malaysia, Portugal, Singapore and Sweden.

We were successful in our recruiting responses from national libraries, with 14 national libraries (20% of the total) reporting they have implemented or are implementing linked data projects or services (compared to 4 in 2014). Academic libraries represented 31% of the 2015 respondents (23), followed by 9 multi-institutional networks (14%), 7 government (10%), 6 scholarly projects — hosted by a single responding institution but involving multiple institutions around a particular subject or theme (8%), 5 public libraries (6%), 3 museums (4%), 3 societies (4%) and one publisher. Examples from these sectors are presented in Section 5.

The 71 institutions responding to the 2015 survey reported a total of 168 linked data projects/services, of which 112 were described by respondents at various levels of detail. Two-thirds of the described linked data projects/services are in production, of which 61% have been in production for more than two years. This represents a doubling of the number of "mature" projects/services in production reported in 2014. Ten of the projects are "private", for that institution's use only.

| How long linked data project/service in production | 2015 | 2014 |

| Not yet in production | 37 | 27 |

| Less than one year | 19 | 13 |

| More than one year, less than two years | 10 | 12 |

| More than two years | 46 | 24 |

| Total projects/services described | 112 | 76 |

Table 1: Survey Responses on Time Linked Data Projects Have Been in Production

External groups involved:Thirty-five of the projects did not involve any external groups or organizations, but most (69%) did involve some level of external collaboration. In order of frequency named, the external collaborators were: other universities or research institutions; other libraries or archives; external consultants or developers; part of a national collaboration; other consortium members; a systems vendor; part of an international collaboration; a corporation or company; part of a state- or province-wide initiative; part of a discipline-specific collaboration; a scholarly society; a foundation.

Staffing: Almost all of the institutions that have implemented or are implementing linked data projects/services have added linked data to the responsibilities of current staff (98); only 14 have not. Twenty have staff dedicated to linked data projects (twelve of them in conjunction with adding linked data to the responsibilities of current staff). Four are adding or have added new staff with linked data expertise; thirteen are adding or have added temporary staff with linked data expertise; and seventeen are hiring or have hired external consultants with linked data expertise.

Funding: Twenty-five of the projects received grant funding to implement linked data; nearly three-quarters (82) are funded by the library/archive and/or the parent institution. Five linked data projects received funding support from partner institutions; one received corporate funding and one was privately funded.

As many projects are still at an early stage (pre-implementation or early implementation), relatively few respondents were prepared to assess their projects' success. 46 reported that their linked data project or service was successful or "mostly" successful. Comments on measuring success clustered around:

- Data re-use: One expectation of linked data is that it will enable broader use of local data by more communities. Although one respondent noted that other websites on campus consumed their data and that different data resources were successfully integrated, a couple noted the difficulty to ascertain how much of their data is being disseminated and re-used.

- Increased discoverability: One goal for publishing linked data is to increase the discoverability of the institution's resources. One pointed to high search engine ranking for its collections' rare content as a success metric.

- New knowledge creation: Some see repositioning library knowledge work and providing access to its resources through the semantic Web as a network activity enriching researchers' understanding. One pointed to better support of multilingualism by fetching multilingual labels from linked data vocabularies.

- Thought leadership: The linked data efforts demonstrated that the institution was taking the initiative in laying the groundwork for a future, different environment. The metrics used include good publicity and feedback among library linked data communities, demonstrating linked data possibilities and the influence on others' linked data projects.

- Preparation for the semantic Web: A couple noted the benefits of preparing their existing metadata and facilitating metadata remediation for the semantic Web — even without any tangible improvements yet — and that it is a worthwhile investment of resources.

- Operational success: Metrics used include working well with other services that use the data and inspiring others to contribute content. One noted that publishing digital collections as linked data improved discoverability and connections with related data sets, and another that crawlers know what to do with their linked data.

- Organizational development: Even absent metrics demonstrating linked data's value to others, linked data projects still provide professional development for staff.

- Organizational transformation: Changing catalog data management from MARC-based records to RDF modeling and linked data principles will require new workflows across the library community, now hampered by data duplication. Linked data can give non-librarian content specialists more control over the authorities they use.

In both the 2014 and 2015 surveys, most projects/services both consume and publish linked data. Relatively few only publish linked data.

| How linked data is used | 2015 survey | 2014 survey |

| Consume linked data | 38 | 25 |

| Publish linked data | 10 | 4 |

| Both consume & publish | 64 | 47 |

Table 2: Survey Responses on How Linked Data Is Used

3 What and Why Linked Data Is Published

Given the relatively large representation of libraries among respondents, it is no surprise that bibliographic and authority data are the most common types of data published (56 and 45 responses respectively), with descriptive metadata a close third (43). Other types of data published as linked data reported: Ontologies/vocabularies (30), digital collections (26), geographic data (18), datasets (16), data about museum objects (10), encoded archival descriptions (5), organizational data (5) and data about researchers or library staff (2).

Most of the linked data datasets are small. Of the 67 responses reporting their datasets' size, 39 were less than 10 million triples and 19 were more than 100 million triples. Only three reported sizes of over 1 billion triples: North-Rhine-Westphalian Library Service Center (1-5 billion), the Norwegian University of Science and Technology's "various" linked data projects totaling 15 billion triples, and OCLC's WorldCat Linked Data (15 billion triples).

Comparing the 2014 and 2015 survey results, the key motivations to publish linked data appear unchanged. While the number of responses increased due to greater survey participation, the relative rank of motivations remained the same, as shown in Table 3.

| Chief Motivations for Publishing Linked Data | 2015 | 2014 |

| Expose data to a larger audience on the Web. | 91% | 88% |

| Demonstrate what could be done with datasets as linked data. | 80% | 80% |

| Heard about linked data and wanted to try it out by exposing some local data as linked data. | 58% | 41% |

| Explore whether publishing data as linked data will improve Search Engine Optimization (SEO) for local resources. | 38% | 18% |

Table 3: Chief Motivations for Publishing Linked Data

A few responded that their administrations had specifically requested that they expose their data as linked data. The British Library noted that their linked data services were part of the UK Government's Public Sector Initiative. Other reasons written in included:

- The need to publish linked data to consume it and to re-use it in future projects

- Maximize interoperability and reusability of the data

- Testing BIBFRAME3 and schema.org

- A project requirement

- Provide stable, integrated, normalized data on research activities across the institution.

Most projects/services that have been implemented received an average of fewer than 1,000 requests a day over the previous six months. The seven most heavily used linked data datasets as measured by average number of requests a day, with over 100,000 requests per day are:

- Europeana, which aggregates metadata for digital objects from museums, archives and audiovisual archives across Europe

- The Getty Vocabularies: Art & Architecture Thesaurus (AAT), Getty Thesaurus of Geographic Place Names (TGN) and Union List of Artist Names (ULAN)

- Library of Congress' Linked Data Service with over 50 vocabularies

- National Diet Library's NDL Search, providing access to bibliographic data from Japanese libraries, archives, museums and academic research institutions.

- North Rhine-Westphalian Library Service Center's Linked Open Data service, providing access to bibliographic resources, libraries and related organizations and authority data.

- OCLC's WorldCat Linked Data, a catalog of over 370 million bibliographic records made experimentally available in linked data form.

- OCLC's Virtual International Authority File (VIAF), an aggregation of over 40 authority files from different countries and regions.

Another six linked data datasets receive between 10,000 and 50,000 requests a day:

- American Numismatic Society's nomisma Thesaurus of numismatic concepts

- Bibliothèque nationale de France's data.bnf.fr, providing access to the BnF's collections and providing a hub among different resources

- British Library's British National Bibliography

- National Diet Library's Authority Data

- OCLC's WorldCat Works, the high-level description of a resource common to all editions of a work

- OCLC's FAST (Faceted Application of Subject Headings), a faceted subject heading schema derived from Library of Congress' subject headings

Linked data datasets use a variety of RDF vocabularies and ontologies, and most use multiple ones. The datasets respondents named, in the order of the frequency cited, are:

- Simple Knowledge Organization System (skos)

- Friend of a Friend (foaf)

- DCMI Metadata Terms (dcterms)

- Dublin Core Metadata Element Set (dce)

- Schema.org vocabulary (schema)

- The Bibliographic Ontology (bibo)

- Local Vocabulary

VOCABS rda - Europeana Data Model vocabulary (edm)

- ISBD elements (isbd)

WGS84 Geo Positioning (geo) - BIBFRAME Vocabulary (bf)

- Expression of Core FRBR Concepts in RDF (frbr)

- The Event Ontology (event)

- Metadata Authority Description Schema (mads)

- CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model (crm)

- BIO: A vocabulary for biographical information (bio)

MODS RDF Ontology

The OAI ORE terms vocabulary (ore)

Core Organization Ontology (org) - DPLA Metadata Application Profile (MAP)

FRBR-aligned Bibliographic Ontology (fabio)

Library extension of schema.org (lib)

Music Ontology (mo)

VIVO Core Ontology (vivo) - Archival collections ontology (arch)

ISNI (International Standard Name Identifier — ontology yet to be published)

RDA Group 2 Elements (rdag2) - British Library Terms RDF schema (blt)

Data Catalog Vocabulary (dcat)

EAC-CPF Descriptions Ontology for Linked Archival Data (eac-cpf)

Nomisma Ontology - Radatana

Review Vocabulary (rev)

Licenses:4 Twenty-six projects/services do not announce any explicit license; an equal number apply CC0 1.0 Universal, the most common license used. Other licenses that respondents use, in order of frequency, are:

- Open Data Commons Attribution (ODC-BY)

- Open Data Commons Open Database License (ODC-ODbl)

- Public Domain Dedication and License or PPDL

- Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives (BY-NC-ND)

- French Government's Open Licence (similar to ODC-BY)

- Creative Commons Attribution 3.0

- Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike 3.0

- Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

- Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License

- Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial ShareAlike 4.0 International (BY-NC-SA)

- Open Data Commons Attribution-ShareAlike Community Norms

Accessibility: Of the 74 projects or services that publish linked data, 19 do not currently make their data accessible outside their institution. Most of the 74% that do offer multiple methods. Web pages are the most common method, followed by content negotiation, file dumps, SPARQL endpoint, SPARQL editor and applications. The most common serialization of linked data used is RDF/XML. Other serializations that are less often used by order of frequency cited are: Turtle, JSON-LD, N-Triples, RDFa Core, RDF/JSON, Notation3 and N-Quads.

Technologies: The technologies used by respondents to publish linked data are diverse, and most used multiple technologies. Table 4 lists the technologies used in order of frequency.

| No. of Projects Used | Technology (order of frequency) |

| 10 or more | SPARQL, Java, XSLT, Zorba |

| 2-9 | Solr, Virtuoso Universal Server (provides SPARQL endpoint), Google Refine, Jena Applications, RDF Store, Drupal7, Python, Apache Fuseki, ElasticSearch, Perl, Metafacture, DIGIBIB, MongoDB, 4store, Apache Marmotta, BlazeGraph, GraphDB (formerly OWLIM by Ontotext Software), Hydra, Numishare (built on Orbeon, eXist and Solr), Rails |

| 1 | Apache Tomcat, Cubicweb, Django, dotNetRDF, Fedora Commons, Hbase/Hadoop, JAX-RS, Joomla, LibHub, Mapping Memory Mapper (3M), MARC Report and MARC Global (from The MARC of Quality), MySQL, Node.js, Oracle, PoolParty, Protègè, Pubby, r2rml-parses, Ruby, Ruby Virtuoso triplestore, Sesame, skosmos, Wordpress |

Table 4: Technologies Used for Publishing Linked Data

Barriers: The primary barriers to publishing linked data cited by respondents, in the order of the most cited are:

- Steep learning curve for staff

- Inconsistency of legacy data

- Selecting appropriate ontologies to represent our data

- Establishing the links

- Little documentation or advice on how to build the systems

- Lack of tools

- Immature software

- Ascertaining who owns the data

Several also noted as additional barriers restrictive licenses, insufficient resources, data sets too large to publish as a whole (and difficult for others to consume), insufficient institutional support and adapting the current infrastructure with linked data technologies.

4 What and Why Linked Data Is Consumed

Shown below are the linked data resources most consumed by the 2015 survey respondents (those consumed by 12 or more projects) in order of the most frequently cited. (Astericks denote resources from institutions that are survey respondents.)

- Virtual International Authority File (VIAF)*

- DBpedia

- GeoNames

- id.loc.gov*

- Resources the respondents convert to linked data themselves

- Getty's Art and Architecture Thesaurus*

- FAST Linked Data*

- WorldCat.org*

- data.bnf.fr*

- Deutsche National Bibliothek Linked Data Services*

These could be considered successful publishers of linked data by the degree to which others consume the data provided. Library respondents who have implemented projects consuming linked data from other sources generally chose sources in the library domain to consume rather than expanding their universe to non-library sources, with DBpedia and GeoNames being the two exceptions.

Other linked data sources consumed by at least four projects or services in order of frequency cited: WorldCat.org Works, ISNI (International Standard Name Identifier), Europeana, Lexvo, DPLA (Digital Public Library of America), Wikidata, ORCID (Open Researcher and Contributor ID), AGROVAC (United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization), Hispana, Nomisma.org and Pleiades Gazetteer of Ancient Places.

Although the numbers differed between the 2014 and 2015 surveys, the primary reasons for institutions to consume linked data had similar rankings, as shown in Table 4.

| Chief Motivations for Consuming Linked Data | 2015 | 2014 |

| Provide local users with a richer experience. | 76% | 73% |

| Enhance local data by consuming linked data from other sources. | 74% | 77% |

| More effective internal metadata management. | 48% | 33% |

| Greater accuracy and scope in local search results. | 40% | 25% |

| Explore whether consuming linked data from external sources will improve Search Engine Optimization (SEO) for local resources. | 28% | 25% |

| Experiment with combining different types of data into a single triple store. | 25% | 31% |

| Heard about linked data and wanted to try it out by using linked data resources. | 25% | 27% |

Table 5: Chief Motivations for Consuming Linked Data

Barriers: The primary barriers to consuming linked data cited by respondents, in the order of the most cited:

- Matching, disambiguating and aligning source data and linked data resources

- Mapping of vocabulary

- What's published as linked data is not always reusable or lacks URIs

- Lack of authority control

- Datasets not being updated

- Size of RDF dumps

Understanding how data is structured before using it - Volatility of data format of dumps, and

- Lack of tools

Unstable endpoints - It's difficult to get other institutions to do their own harmonization between objects and concepts

Service reliability - Disambiguation of terms across different languages is difficult

Other barriers written in included: licenses more restrictive than ODC-BY; institutions viewing linked data as research projects rather than infrastructure; insufficient number of linked data datasets of local interest; API limits; and insufficient resources to incorporate consumed linked data into routine workflows.

5 Examples in Production

The spreadsheet5 containing all responses to both the 2014 and 2015 surveys includes the links to the 75 linked data projects or services in production reported in 2015. A few examples from the different types of respondents are described here.

5.1 National Libraries

Most of the 16 national library linked data projects or services in production provide access to their bibliographic and authority records as linked data. Three national libraries' linked data datasets are among the top 12 consumed by all respondents: id.loc.gov (Library of Congress), data.bnf.fr (Bibliothèque nationale de France) and DNB Linked Data Service (German National Library).

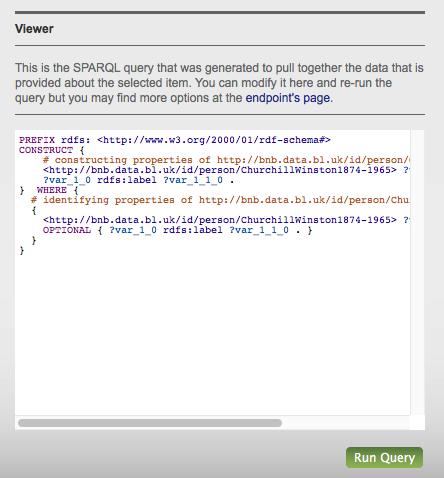

The British Library was one of the first to make its national bibliography available as linked open data, exposing it in bulk. It is considered successful as it has been selected for the UK National Information Infrastructure and its data model has been influential. Entities include links to both ISNI (International Standard Name Identifier) and VIAF identifiers. The end of the html page for an entity shows the SPARQL query to retrieve the result that people can modify and re-run, as illustrated below:

Figure 1: The British National Bibliography's SPARQL Query Viewer

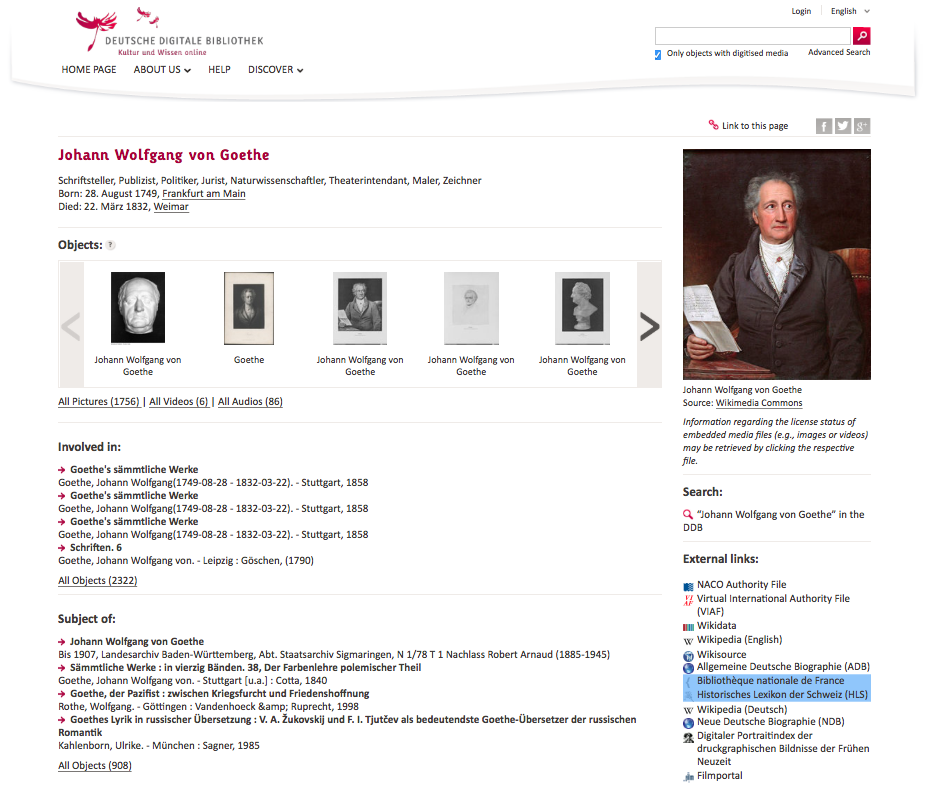

The German National Library described four projects that publish linked data: German National Bibliography, German Integrated Authority File (GND), its BIBFRAME prototype, and Entity Facts, which aggregates information about entities from various sources in a data model facilitating reuse by developers without domain knowledge. Its Web interface provides information in German and English (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Screen shot of Example from German National Library's Entity Facts

The National Diet Library reported on 5 projects in the 2015 survey that publish linked data: bibliographic data, authority data, International Standard Identifier for Libraries and Related Organizations (ISIL) for Japan, an aggregation of resources related to the Great East Japan earthquake of 2011 and the Nippon Decimal Classification (the Japanese standard classification system), currently being converted into linked data.

5.2 Networks

Digital Public Library of America provides access to public domain and openly licensed content held by archives, libraries, museums, and other cultural heritage institutions in the United States6.

Europeana aggregates metadata for digital objects from libraries, museums, and archives across Europe. Its Europeana data model (EDM) is based on semantic web principles. It fetches multilingual labels from linked data vocabularies.

The North Rhine-Westphalian Library Service Center (hbz) publishes one of the largest linked data datasets (1-5 billion triples). Its linked open data API provides access to 20 million bibliographic records and 45 million holdings from the hbz union catalog; to authority data from the German Integrated Authority File (GND); and to library address data from the German International Standard Identifier for Libraries and Related Organizations (ISIL) registry.

OCLC has published well over 20 billion RDF triples extracted from MARC records and library authority files. This constitutes the largest library aggregation of linked data resources in the world. Three of these linked data sources (FAST, VIAF and WorldCat) were among the top 10 linked data sources consumed by the 2015 survey respondents.

5.3 Academic Libraries

Most academic library respondents' linked data projects are experimental in nature. North Carolina State University's Organization Name Linked Data database includes links created by its Acquisitions and Discovery staff to descriptions of the same organization in other linked data sources, including the Virtual International Authority File (VIAF), the Library of Congress Name Authority File (LCNAF), Dbpedia, Freebase, and International Standard Name Identifier (ISNI).

5.4 Public Libraries

Few public libraries responded to the survey, and only two have projects or services in production. Arapahoe Library District is an early adopter of the LibHub initiative7 to have its catalog Web accessible. The Oslo Public Library converted its MARC catalog to RDF linked data enriched with information harvested from external sources and constructed with SPARQL update queries. Its collection of book reviews written by Norwegian libraries link to the bibliographic data.

5.5 Museums

Few museums responded to the survey. The British Museum's Semantic Web Collection Online is organized around the CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model to harmonize its data with that from other cultural heritage organizations.

5.6 Scholarly projects

Dalhousie University's Institute for Big Data Analytics hosts the multidisciplinary and multinational Muninn Project aggregating data about World War I in archives around the world. It extracts data from digitized documents and converts it into structured databases that can support further research. It also hosts the Canadian Writing Research Collaboratory, an online infrastructure project to investigate links between writers, texts, places, groups, policies, and events.

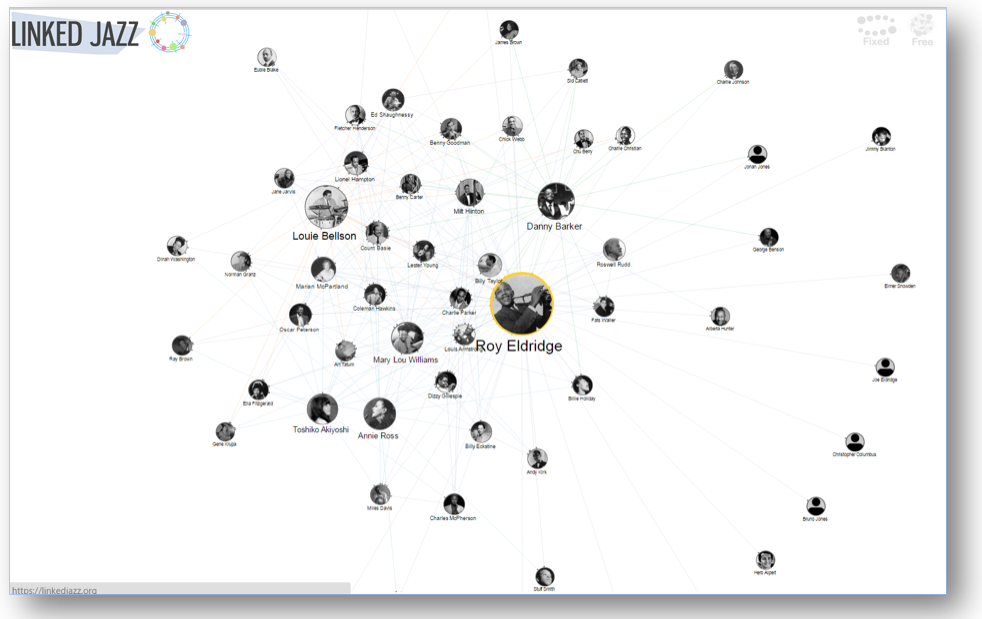

The Pratt Institute's Linked Jazz project applies Linked Open Data technologies to digital heritage materials and explores the implications of linked data in the user experience. It exposes relationships between musicians and enables jazz enthusiasts to make more connections. It generates triples from the content of interview transcripts from five jazz archives — from the data rather than converting existing metadata. The first phase of the project was funded through an OCLC/ALISE Library and Information Science Research grant. [8]

Figure 3: Screen shot of a Linked Jazz display

Nomisma is a collaborative, international project among cultural heritage institutions hosted by the American Numismatic Society providing a linked open data thesaurus of numismatic terms and identifiers.

5.7 Publishers

Springer is the only publisher to respond to our survey. It is making data about scientific conferences available as Linked Open Data to make information about publications, authors, topics and conferences easier to explore and to facilitate analysis of the productivity and impact of authors, research institutions and conferences.

6 Conclusion

The responses to the 2015 survey may be considered a snapshot of a linked data environment still evolving. We have a partial view of the landscape, as our analysis is confined to those who responded to the survey, primarily from the library domain. Many of the projects described are experimental in nature, as indicated by a wide range of ontologies and technologies used.

Linked data projects have focused on the data. Developing linked data services that provide new or better value to communities than the current architecture will require developing applications taking advantage of multiple linked data sources and integrating datasets from different domains. Several noted that linked data enabled them to overcome silos of data within their own institution.

A number of the projects and services described are multi-institutional and collaborative. Such collaboration may help alleviate lack of resources at the institutional level while providing a means to scale learning where local expertise is scarce. Respondents noted the value of the learning experiences provided by working with linked data as preparation for a more "web aware" environment. Educational motivation may be the primary driver for institutional involvement. Respondents offered advice for others considering a linked data project, including:

- Focus on what you want to achieve, not technical stuff.

- Model data that solves your use cases.

- Strive for long-term data reconciliation and consolidation.

- Add distinctive value: Build on what you have that others don't.

- Pick a problem you can solve.

- Involve your institution/community.

- Have a good understanding of linked data structure, available ontologies and your own data.

- Consume your own published data.

- Consider legal issues from the beginning.

- Read as widely as possible and consult community experts.

- Start now! Just do it!

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the contributions of OCLC colleagues Jean Godby, Constance Malpas and Jeff Young to this article.

References

| 1 | The OCLC Research Library Partnership allies like-minded research libraries in twelve countries, providing a venue to undertake cooperative actions that benefit scholars and researchers everywhere. |

| 2 | The results of the 2014 survey were posted on HangingTogether.org between 28 August 2014 and 8 September 2014: Linked Data Survey results 1 — Who's doing it; Linked Data Survey results 2 — Examples in production; Linked Data Survey results 3 — Why and what institutions are consuming; Linked Data Survey results 4 — Why and what institutions are publishing; Linked Data Survey results 5 — Technical details; Linked Data Survey results 6 — Advice from the implementers. |

| 3 | BIBFRAME is the Bibliographic Framework Initiative launched by the Library of Congress to provide a foundation for the future of bibliographic description in the broader networked world. |

| 4 | The W3C provides an overview of licensing for linked open data. See also Open Data Commons (ODC) licenses and Creative Commons (CC) licenses. |

| 5 | Spreadsheets with the complete responses to both the 2014 and 2015 International Linked Data Survey for Implementers are publicly available from OCLC here. |

| 6 | See the current list of the DPLA's partners. |

| 7 | The Libhub initiative's goal is to raise the visibility of libraries on the Web by "exploring the promise of BIBFRAME and Linked Data." |

| 8 | OCLC Research and the Association for Library and Information Science Education (ALISE) annually collaborate to offer grant awards up to $15,000 to support one-year research projects that offer innovative approaches to integrate new technologies and that conduct research contributing to a better understanding of the information environment and user behaviors. For more information, see: http://www.oclc.org/research/grants.html. |

Appendix: Institutions Responding to International Linked Data Survey for Implementers

| Institution | Country | 2015 Survey | 2014 Survey |

| ABES | France | X | |

| Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional para el Desarrollo (AECID) | Spain | X | |

| American Antiquarian Society | USA | X | |

| American Numismatic Society | USA | X | X |

| Anythink Libraries | USA | X | |

| Arapahoe Library District | USA | X | |

| Archaeology Data Service (UK) | UK | X | |

| Biblioteca della Camera dei deputati (Italy) | Italy | X | X |

| Biblioteca. Real Academia Nacional de Medicina | Spain | X | |

| Biblioteca Valenciana Nicolau Primitiu | Spain | X | |

| Biblioteca Virtual de Derecho Aragonés | Spain | X | |

| Bibliotheque nationale de France | France | X | |

| BIBSYS NTNU (Norwegian University of Science and Technology) University Library | Norway | X | X |

| Big Data Institute | Canada | X | |

| British Library | UK | X | X |

| British Museum | UK | X | X |

| Carleton College | USA | X | X |

| Charles University in Prague | Czech Republic | X | |

| Chemical Heritage Foundation | USA | X | |

| Colorado College | USA | X | x |

| Colorado State University | USA | X | X |

| Columbia University | USA | X | |

| Consejería de Educación, Cultura y Deportes Gobierno de Castilla-La Mancha, Españaa | Spain | X | |

| Consorci de Serveis Universitaris de Catalunya | Spain | X | |

| Cornell University | USA | X | X |

| Dartmouth College | USA | X | |

| Data Archiving and Networked Services, Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences | The Netherlands | X | |

| Digital Public Library of America | USA | X | X |

| Diputación de Málaga. Cultura y Deportes. Biblioteca Cánovas del Castillo | Spain | X | |

| Europeana Foundation | The Netherlands | X | X |

| Evansville Vanderburgh Public Library | USA | X | |

| Fundacción Ignacio Larramendi (Spain) | Spain | X | X |

| German National Library | Germany | X | |

| Goldsmiths' College | UK | X | |

| Haute école de gestion de Genève (SwissBib) | Switzerland | X | |

| J. Paul Getty Trust | USA | X | |

| Koninklijke Bibliotheek | The Netherlands | X | |

| Laurentian University | Canada | X | |

| Library of Congress | USA | X | X |

| Ministry of Defense (Spain) | Spain | X | |

| Minnesota Historical Society | USA | X | X |

| Missoula Public Library | USA | X | |

| National Diet Library | Japan | X | |

| National Library Board (NLB) of Singapore | Singapore | X | |

| National Library of Malaysia | Malaysia | X | |

| National Library of Medicine | USA | X | X |

| National Library of Portugal | Portugal | X | |

| National Library of Spain | Spain | X | |

| National Library of Sweden | Sweden | X | |

| National Library of Wales | UK | X | |

| National Széchényi Library | Hungary | X | |

| New York Public Library | USA | X | |

| New York University | USA | X | |

| North Carolina State University Libraries | USA | X | X |

| North Rhine-Westphalian Library Service Center | Germany | X | |

| NTNU (Norwegian University of Science and Technology) University Library | Norway | X | X |

| OCLC | USA | X | X |

| Ohio State University | USA | X | |

| Oslo Public Library | Norway | X | X |

| Pratt Institute | USA | X | |

| Public Record Office, Victoria | Australia | X | |

| Queen's University Library | Australia | X | |

| RERO — Library Network of Western Switzerland | Switzerland | X | |

| Research Libraries UK | UK | X | |

| Smithsonian | USA | X | X |

| Springer | USA | X | X |

| Stanford University | USA | X | X |

| Stichting Bibliotheek.nl | The Netherlands | X | |

| The European Library | The Netherlands | X | X |

| Tresoar (Leeuwarden — The Netherlands) | The Netherlands | X | |

| Università degli Studi Roma TRE | Italy | X | |

| University College Dublin | Ireland | X | |

| University College London (UCL) | UK | X | |

| University of Alberta Libraries | Canada | X | X |

| University of Applied Sciences St. Poelten | Austria | X | |

| University of Bergen Library | Norway | X | X |

| University of British Columbia | Canada | X | |

| University of California-Irvine | USA | X | X |

| University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign | USA | X | |

| University of Liverpool | UK | X | |

| University of Nevada, Las Vegas | USA | X | |

| University of North Texas | USA | X | |

| University of Oxford | UK | X | |

| University of Pennsylvania Libraries | USA | X | X |

| University of Tennessee, Knoxville | USA | X | |

| University of Texas at Austin | USA | X | X |

| Villanova University | USA | X | |

| Wellcome Library | UK | X | |

| Western Michigan University | USA | X | X |

| Yale Center for British Art | USA | X |

About the Author

Karen Smith-Yoshimura is Senior Program Officer at OCLC and works with research institutions affiliated with the transnational OCLC Research Library Partnership on issues related to creating and managing metadata. She is based in the OCLC Research office in San Mateo, CA.

|

|

|

| P R I N T E R - F R I E N D L Y F O R M A T | Return to Article |