|

Satan's Progeny: the Question of the Text

Recent commentators on Stoker's novel Dracula have stressed the work's almost obsessive concern with issues of writing and textuality. Presenting a view of the text as excess of semiotic production, a blown-up monstrosity of genres and literary registers, Dracula embarks on a series of perspectives concerned with the "conditions, processes, and motivations upon which the production, circulation and exchange of its discourses depend" (Pope 1999: 68). The open-ended and multiple structure of the book has invited a number of examinations dealing with the relationship of text, gender and sexuality in the past, but my interest is restricted to the novel’s preoccupation with Christian symbolism and Christian anxiety about the status of written texts as documents and witnesses to pseudo-sacred events.1

As a novel that lives off a vast compilation of others texts, Dracula implies a whole host of biblical references, such as proverbs, psalms and fragments taken from the gospels or from the Old Testament prophetical books. It has generally been accepted to see this multiplicity in terms of the unique contribution it makes to Bakhtin's paradigm of the carnivalesque – a composite form according to which the various planes of information the novel provides exist less in a hierarchical than in a dialogical relation to each other (cf. Pope 1999: 69; Senf 1979). Recasting the issue so as to account for the many allusions to the gospels and the Evangelists, however, forces one to admit that the portions of written or transcribed text also serve to shape and encapsulate a textual world in accordance with the teachings of a tightly organized system of religious beliefs. In fact, Dracula properly seems to explore the process of doctrinal partitioning inherent in all forms of metaphysical enterprise entailing the establishing of a new Church or religious institution – a problem relating the novel to the widespread tendency among fin de siècle artists and writers to convert to Catholicism (cf. Feinendegen 2002; Hanson 1997) and thus to the widely felt need for new and meaningful spiritual, 'post-Anglican' options. Stoker draws on these developments, forcing his readers to acknowledge the living presence of biblical motifs and scenes while at the same time interlinking his array of carefully fragmented surfaces with the doctrine informing it and the concomitant cultural anxiety reflecting its status as open-ended und unfinished text, as a body of signs relating to other groups of signs, meanings and textual registers.

Before the novel can be analyzed, it seems necessary to provide some preliminary framing of my own discussion; the historical dimension of the making of the gospels needs brief consideration as a framing pattern in which Dracula comes to develop its own specific intention. Moreover, the fact that the gospels are Christian and therefore deeply imbued in a polarizing religious spirit, makes it necessary to explore the idea of Satan as a singular character derived from specifically Christian textual sources. The Count's satanic traits need not be emphasized here, since they are evident; but it is especially in relation to the other characters' desire to fix his identity that Dracula – and with him Van Helsing as his implied counterpart – acquires an extraordinary and intriguing symbolical status as a figure of hellish proportions.

It is well-known today that while angels often appear in the Hebrew Bible, Satan is virtually absent from the text. Only among some "first-century Jewish groups, prominently including the Essenes (who saw themselves as allied with angels) and the followers of Jesus, the figure variously called Satan, Beelzebub, or Belial [...] began to take on central importance."2 The eternal archetypal Antichrist, who stands in open rebellion against God, can be seen as a construct invented by early Christian zealots to "confirm their own identification with God and to demonize their opponents – first other Jews, then pagan, and later dissident Christians called heretics" (Pagels 1996: xvii). It is not unreasonable to assume that Stoker conceived of his elitist coterie of sworn compatriots in a similar vein, depicting them as apostles in quest of their own 'true faith'. Their strict control over textual matters and procedures is their primary weapon in this quest and therefore an adequate image of the 'apostolic mission' the novel engages. Figuring as a self-sufficient unity, characters Quincey Morris, Mina and Jonathan Harker, Van Helsing, Arthur Holmwood and John Steward frequently remind the reader of the early disciples or followers of Jesus and their keen interest in purging their faith from all oppositional views and forces to keep the newly established structure internally 'clean'.3 The vision of supernatural struggle they pursue and contain in their writing both expresses deeply ingrained religious anxieties and conflicts and raises them to the status of elements in a struggle of cosmic dimensions. As in the widely disputed case of Jesus brought to trial in front of the Jewish Sanhedrin (the council of elders), as reconstructed from the four gospel narratives (cf. Pagels 1996: 26–28, Nineham 1967: 400–12), the reader feels the whole persecution as unfolded in Dracula is only an invention of a later date, manipulated by a sworn circle of fanatics insisting on their own version of the truth and adapting it to their own immediate psychological needs; as Clive Leatherdale puts it: "The marshaled diary extracts and letters are themselves endowed with the status of scripture. Instead of the Gospels according to St. Matthews and St. Mark, we find Gospels according to Mr. Harker and Dr. Seward. [...] They constitute a 'revelation' of Dracula's existence, as the Bible offers a 'revelation' of Christ's" (Leatherdale 1985: 177).

Miracle workers or, Rereading the Satanic Verses

From the very beginning, the novel is entangled in matters of textual control, paradoxically insisting on the potentially disruptive and self-questioning nature of the text it produces; there is neither a supreme narrative voice nor a master discourse in Dracula:

How these papers have been placed in sequence will be made manifest in the reading of them. All needless matters have been eliminated, so that a history almost at variance with the possibilities of later-day belief may stand forth as simple fact. There is throughout no statement of past things wherein memory may err, for all the records chosen are exactly contemporary, given from the standpoints and within the range of knowledge of those who made them. (5)

As readers, we never learn the true identity of the author of these lines but, written as they are from the viewpoint of a higher narrational authority, they certainly must be interpreted as a cautionary note inviting the reader to soberly contemplate the process of textual production and to tell latent from manifest sense. The suggestion of temporal simultaneity ("exactly contemporary") is a first hint, moreover, that the novel is supposed to be read as a communal effort of individuals tied to each other through their role as witnesses to an incredible event as well as by the magical band which makes them feel about their experiences in a similar way. This textual ambivalence is displaced throughout the text's rendering of Dracula's story, yielding different levels of resonance and credibility and thus forcing the reader to develop a critical attitude towards the different genres, textual registers and narrators involved.

In addition to that, the passage raises another issue: it implies a sensitive reader enabled and entitled to do the reading for himself. Deprived of all scriptural or interpretive authority external to the text, such an addressee is likely to come very close to the ideal reader presupposed by Paul of Tarsus, a reader susceptible to acts of absolute faith and thrown back entirely on his or her own resources and self-supposed spiritual enlightenment: "The just shall live by faith" (Rom. 1:17).4 That the dimension of faith as rendered in the Scriptures is indeed a vital part of the tale is made plain fairly early in the colossal witch hunt the novel delineates; simple parables conceived for those who “seeing [that] they might not see, and hearing they might not understand” (Luke 8:10) are rendered alongside portions of ornate text intended for those who have in them the power to allow themselves to be convinced:

'My friend John, when the corn is grown, even before it has ripened – while the milk of its mother-earth is in him, and the sunshine has not yet begun to paint him with his gold, the husbandman he pull the ear and rub him between his rough hands, and blow away the green chaff, and say to you: "Look! He's good corn; he will make good crop when the time comes." ' (111)

The biblical pun Van Helsing employs to convince John Seward of the exiguity of prudent action points the reader to Luke 8:8 where a similar statement involves the notion of distinguishing devoted worshipers and new admirers from fierce unbelievers ("And when he had said these things, he cried, He that hath ears to hear, let him hear").5 At this point the central issue of Christian symbolism in Dracula comes into full view, with the reader asking himself who the ambiguous Van Helsing precisely is and whether he is supposed to be read as a messianic figure redeeming the other characters from the satanic spell cast upon them; does he command healing powers, or can he perform miracles like Jesus before him?6

A related question concerns the role of his counterpart, the vampiric Count and his voluntary female helpers. John Seward's zoophagous patient Renfield, for instance, expects a new "master" to descend soon who is associated, throughout the text, with the Count ("... the master is at hand", 96; "Come in, Lord and Master!", 245); his references and allusions are couched, however, in the same biblical terminology employed by Van Helsing and his circle. Thus, e. g., Renfield announces the new Lord in terms of a bride ("The bride-maidens rejoice the eyes that wait the coming of the bride; but when the bride draweth nigh, then the maidens shine not to the eyes that are filled"; 97),7 suggesting the Revelation of St. John as the only New Testament text in which the new heaven and new earth are visualized as a "bride adorned for her husband" (Rev. 21:2). What is the reader supposed to make of this? Is the new 'dispensation' enacted by the multi-transgressive Dracula in any way related to Van Helsing's more devout and bigoted counter-efforts? Or are the two characters supposed to be interpreted as two aspects of a formerly unified being, a terrible apparition or idol split in two halves to be reintegrated via a critical reading of the text? That one has to proceed circumspectly in this case is made apparent by John Seward's stern remarks on his patient's growing religious mania: "The real God taketh heed lest a sparrow fall; the God created from human vanity sees no difference between an eagle and a sparrow" (96).8 Like the reader himself whose attention is relentlessly being drawn to the sheer number of biblical references, Seward appears to feel the need for distinctions and clear demarcations in order not to be dragged to deeply into the labyrinth of his patient's mad conjectures. He appeals to the wisdom of ancient authorities in order to set his own disturbed mind at rest but the problem as such is not resolved by this, as both parties involved in the struggle for truth persistently invoke the authority of the Scriptures – these, however, collapse under the burden of having to justify the acts of two similarly fierce and ambiguous opponents!8

The struggle for truth and legitimacy surfacing in these passages reminds one of the power struggles the interpretation of the Scriptures caused in the decades immediately before and after the birth of Christ. The hardships and humiliations of defeat (the Temple had been destroyed by the Romans in A. D. 70), accompanied by long-standing division within the scattered Jewish communities, stimulated a growing number of apocalyptic religious teachers to rewrite the older texts and prophecies in order to adapt to the new political circumstances (Pagels 1996: 67f) – a historical parallel worth being considered here, as Stoker's novel is, quite similarly, located in a cultural climate goaded by the widespread fear of an ‘end time’ and strongly influenced by writers, artists and intellectuals looking for signs indicating that the world was coming to an end. Where, then, do Stoker's characters bring textual pressure to bear on circumstances they can no longer sustain or tolerate? And how do they, as insiders or 'elect', hope to achieve correct interpretations to the mysteries enveloping them?

A crucial scene occurs during a talk between John Seward and Mina Harker engaging the issues of transcription and memorizing recorded later in Mina’s journal. Both characters have in mind the problem of committing to paper the urgency of their emotions in view of the preceding events:

I took the cover off my typewriter, and said to Dr Seward: -

'Let me write this all out now. We must be ready for Dr Van Helsing when he comes. I have sent a telegram to Jonathan to come on here when he arrives in London from Whitby. In this matter dates are everything, and I think that if we get all our material ready, and have every item put in chronological order, we shall have done much.' [...] He accordingly set the phonograph at a slow pace, and I began to typewrite from the beginning of the seventh cylinder. I used manifold, and so took three copies of the diary, just as I had done with all the rest. (198)

The passage not only registers the accuracy with which events are banned on paper, copied and multiplied; in fact, it also acknowledges the magical bond emerging between the workers thus involved in their task of preparing everything for the 'coming' of Van Helsing: "How good and thoughtful he [Seward] is; the world seems full of good men – even if there are monsters in it" (ibid.). It is indeed their writing and typing out as individual acts of witnessing and commemorating which brings Mina and John closer to each other, switching on some kind of currency between them later to be extended to the other group members, and turning them all into human 'threads' interwoven in a texture of mutually revealed and sustained writings. Already at this point in the narrative, Van Helsing has turned into a figure of almost messianic proportions, piecing together the fragments of the others' disrupted lives and giving meaning and new direction to the tormented biographies thus salvaged. Critics frequently have remarked, quite persuasively, that his unique rendition of the Count as a dreadful ogre does not so much shed light on the vampire as a real or identifiable being but rather helps act out the group's "repressed fantasies" and their hidden wish to identify with the aggressor's needs and desires (Roth 1977: 118; cf. Bronfen 1998: 40–47). It is only fair to assume that the difference and demonic opposition thus manifested and located in the Count help closing off the fragile community against enemies and opponents, thus enabling a whole variety of new (and partly outrageous) in-group relationships.10

Yet how can the participants know, contaminated by fear and insanity as they are, that it is not just another "false prophet" (Matt. 24:24) they are inviting into their house? With their strong sense of mission and power for attracting and influencing new disciples Dracula and Van Helsing seem to have more things in common than the reader is at first prepared to admit. Both share a notion of loyalty implying complete self-abandonment and a turning round of their disciples’ rational faculties. John Seward, uncertain about Van Helsing’s suggestion of a vampire as the actual cause of all their troubles, is the only one to develop, if only transitionally, doubts about the Dutch Professor's sanity of mind. ("I have no doubt he believes it all. I wonder if his mind can have become in any way unhinged", 181). Moreover, the text itself seems to express some of these anxieties about identity and interpretative authority by invoking not only prophecies or OT narratives but passages variously taken from the New Testament Gospels and Letters. According to Elaine Pagels, the assertion of a "diabolic" opposition against Christian practices must be regarded as an invention of the early Christian communities themselves who, threatened on all sides by pagans, dissidents and Gnostic heretics, quickly became used to vilify and demonize their religious enemies (Pagels 1996: 84). Van Helsing and Dracula are both implied in this specifically New Testament context, thus suggesting a head-on cosmic struggle for power and predominance over their potential followers. Both, to varying degree, resemble the satanic figure turned into the caricature of a scribe in Matt. 4:1–11, a "debater skilled in verbal challenge and adept in quoting the Scriptures for diabolic purposes" (Pagels 1996: 81) – a fact which makes it difficult to distinguish the chivalrous Van Helsing from the supposedly real and more outspokenly aggressive tempter Dracula. In order to finally differentiate the false prophet (or Satan) from the real one and the truth from the many contradictory reports circulating (and thus to escape eternal damnation), Mina’s group has to shoulder the task outlined above – compiling a gospel of indexed texts separating the true messiah from the 'false' one in such a way that it may entirely stand for itself, resting on nothing but the credibility of facts reported and the coherence of narrative details depicted ("In this matter dates are everything", 198). The problem involved in this, however, is how to legitimate and establish such a text without recourse to any external authority or realm of positive fact, in a situation of grossest bewilderment and moral confusion. As Dracula reveals, the whole thing is founded, in fact, on an act of pure faith in the other group members' sincerity:11

'You do not know me,' I said. 'When you have read those papers – my own diary and my husband’s also, which I have typed – you will know me better. I have not faltered in giving every thought of my own heart in this cause; but, of course, you do not know me – yet; and I must not expect you to trust me so far.' (196)

Mina's whole-hearted and sentimental plea is puzzling insofar as it appears to involve a complete disclosure of even the most intimate facts of her private life – a public revelation uncommon in the context of Victorian moral standards which often relegated women to the margins of social life and discourse.12 Her transgression, inspired in a 'weak' but faithful moment of trust in a like-minded individual gravitating towards her own world of enfeebled emotions, deliberately evokes the notion of a new mode of communal existence sustained by sectarian attitudes knocking over well-established social views and norms. The whole enterprise is indeed founded on an act of faith in a higher yet ineffable authority as continually requisitioned by Van Helsing: "'My thesis is this: I want you to believe.' 'To believe what?' 'To believe in things that you cannot'" (172). John Seward, Van Helsing's former student and still considerably loyal to his teacher's ideas, is frequently reprimanded for not being pliant enough in his responsiveness – a Doubting Thomas eventually to be persuaded. Van Helsing’s numerous efforts to expand his power over the browbeaten group are undeniably informed by scriptural terms and models employed to accelerate an intense situation of utter fidelity and devotion:

'You are a clever man, friend John; you reason well, and your wit is bold; but you are too prejudiced. You do not let your eyes see nor your ears hear [my emphasis], and that which is outside your daily life is not of account to you.' (170)

Like an avenging, omnipotent God or clandestine sect leader, Van Helsing impinges on the other characters' private lives, turning their moral world upside down and forcing them, time and time again, to open their hearts completely and reveal their secrets to him alone:

He [Van Helsing] answered with a grave kindness: -

'I know it was hard for you to quite trust me then, for to trust such violence needs to understand; and I take it that you do not – that you cannot – trust me now, for you do not yet understand. And there may be more times when I shall want you to trust when you cannot[.] [...] But the time will come when your trust shall be whole and complete in me, and when you shall understand as though the sunlight himself shone through. Then you shall bless me from first to last of your own sake, and for the sake of others, and for her dear sake to whom I swore to protect.' (153)

It is not only Van Helsing's constant alluding to scriptural models and instances which makes him look like a paternal yet menacing sun-idol or underworld Osiris in these scenes, a bearer of glad tidings and thus connoting the savior's life and narrative; what indicates and even enhances his status as a figure of quasi-divine proportions as well is the large number of references made to wounds inflicted on him in the past. The novel itself abounds with the imagery of physical wounds;13 yet only some of them relate to Van Helsing in a very specific way, representing him as a sufferer who carries around with himself a dark, unnamable secret marking him as one of the 'chosen few'. The most startlingly meaningful scene in this context occurs relatively early, after Seward’s initial letter seeking aid from his former teacher; the Dutch professor answers immediately:

My good Friend,-

When I have received your letter I am already coming to you. [...] Tell your friend that when that time you suck from my wound so swiftly the poison of the gangrene from that knife that our other friend, too nervous, let slip, you did more for him when he wants my aids and you call for them than all his great fortune could do. (106)

A traumatic injury, part of an event buried in the unexplained past that binds these men to each other, returns, surfacing only in a few hastily written notes. But Van Helsing's constant obsession with wounds does not only refer the reader to a subdued homosexual context in Dracula at this point (cf. Schaffer 1994: 384ff); in fact, the injuries constantly re-imagined and relived also relate Van Helsing to the figure of Christ, if only in a most spuriously metaphorical way. The blood he is prepared to give, multiplied and enriched by the blood of his disciples Morris, Seward and Arthur Holmwood, transforms him, by and large, into an uncanny double or negative counterpart of the Count who makes no bones at all about his continuous need for the fresh blood of new devotees, demanding total homage and submission from every loyal subject. Indeed, the two are shown to be not distant but intimate enemies – the one the other's trusted colleague, close associate, brother even.14 If this figurative relationship demonstrates anything at all, then it is the insight that this most dangerous enemy did not originate, as one might expect, as an outsider, an alien or a stranger. On the contrary: he materialized right out of the centre of the group's own unresolved and unacknowledged emotional conflicts, an unruly image of repressed inner fears and desires ever in need of control and domestication. Control over this enemy, the narrative seeks to point out, can only be exerted and sustained through specific forms of textual practice 'entombing' the dark Lord forever in a vault of carefully ordered signifiers. It is these specific forms and the meaning they produce we need to turn to now.

Imprisoned in a Book: Mina and the 'Four Evangelists'

The writing and putting together of the texts and the anxiety informing and accompanying their compilation is mainly relegated to Mina Harker and thus connected to her more than any other figure in Dracula. As a sensitive character caught between male and female domestic worlds – "She has a man’s brain [...] and a woman's heart" (207), as Van Helsing at one point proudly notes – Mina is particularly prone to losing her firm grasp of reality. She needs to be protected from "Satan's forays" (Pagels 1996: 150) into virgin territory more than the other characters (for the devil generally prefers to prey on members of one’s own peer group); and more than the others she must therefore be included in the practices of unifying the group internally. She is thus assigned the strategic task of typing out the different accounts, "knitting together in chronological order every scrap of evidence they have" (199).15 What precisely is the role of this compilation? I suggest regarding the whole enterprise as a complex reorientation move from one set of beliefs to another one, mounted to avoid a potentially menacing and alien external world – a move couched, nonetheless, in the established rhetoric of redemption: all souls deemed in peril must be included in the act of conversion. Unable to find a true point of communication with others about the disaster so suddenly and unpredictably brought upon them and thus finding themselves isolated in an increasingly hostile and meaningless environment, Mina and her circle wish to ingest it, to make it theirs alone. This incorporation of the other has a variety of connotations all suggesting an initiation rite based on and carried through for the purpose of an internal closure mechanism.

Everything Mina and her circle intend to do or carry out is grounded in a collective agreement mediated through writing; every single act of textualization implies the acceptance of another individual's views into the group – it should not go unnoticed that John Seward, Jonathan and others all contribute pieces of text or diary typed or written – and his or her adoption of the norms and practices advocated by the group ("everything [...] is of interest to our little community", 206; "We have told our secrets, and yet no one who has told is the worse for it", 208). To write a "connected narrative" (199) in which everything fits and matches the singular records is the foremost aim in this venture, indicating the participants' desire to employ autobiography for their aim of group identity formation and personal salvation. To "put down with exactness all that happened" (241) is thus not only an attempt at a truthful rendering of experiences; in fact, its represents an act of self-assertion to be judged primarily by the 'other'; for, before credibility can be awarded every item recorded must stand the test of re-evaluation through other group members, so that, at the end, events can be fixed and confirmed because every other participant has at his or her command exactly the same piece of information ("I glanced at Van Helsing, and saw my conviction reflected in his eyes", 217). Writing thus proves a two-edged weapon in the process of exorcizing the satanic Dracula; it demonstrates the group's paradoxical need for authority in order to be liberated, to be set free from the terrible images of their own apprehension.

Mina's role in the ceremony is of particular interest in this respect, charged as it is with the symbolism of a rite de passage and the accompanying ritual of initiation. When Van Helsing places a wafer on her forehead to purge the girl from her 'sins', it burns into the flesh and leaves a 'mark' on her skin; it is thus a painful inscription indicating Mina's special status in the group but also a ritual mutilation of her body to be interpreted – at least partly – as return to a primitive form of inscribing, a means of identifying her as a neophyte, submissive and liminal yet also marking the transition from her former identity to a new social self in the group’s inner circle.16 Her vulnerable body is seen by the other members as a blank slate on which to inscribe the knowledge and 'wisdom' of the group, in respects that pertain to the new status. In his influential study Rites of Passage, anthropologist Arnold Van Gennep has maintained that the ordeals and humiliations, often of a grossly psychological character, to which neophytes are submitted represent partly a destruction of a previous status and partly a tempering of their essence in order to prepare them to cope with their new responsibilities and restrain them in advance from abusing their new privileges. (130)

Mina, in other words, has entered the 'adult' social order, leaving behind her innocent or 'childhood' self which proved a hindrance rather than enrichment of the group’s enterprises. She participates in the group's ceremony as a 'living text', retaining the intensely physical reality of the inscription / mutilation but also accomplishing the transition from her former self to the rules of the new community: "Then without a word we all knelt down together, and, all holding hands, swore to be true to each other. We men pledged ourselves to raise the veil of sorrow from the head of her whom, each in his own way, we loved; and we prayed for help and guidance in the terrible task which lay before us" (259).

Conversion to a group's normative principles, personal salvation and the act of writing thus converge in the act of Mina's initiation. Having internalized the system of social valuations of the group to which she belongs, she now conceives of her new self as a dignified subject, enabled to make the system part of her own identity. Still, her role in the process is somewhat peculiar; for where the (male) others 'inscribe' meaning on a human body by, e.g., driving stakes through a dead woman's – Lucy's – body,17 Mina inscribes through her producing textual surfaces that give meaning to formerly opaque events; her acts of inscription never kill as they appropriate or signify possession alone. Generally, her routines of first penetrating into a matter and then compiling and collating her information prove far more efficient with regard to the group’s exorcizing purposes and intentions. She thus represents, in every respect, the firm and respected civilizing female dominating conservative Victorian mythology (cf. Auerbach 1982: 15ff); it is up to her to further refine the ancient ritual and to erase the traces of violent primitivism still adhering to it.

In one of his earlier essays, Michel Foucault has traced this practice of commemorating through writing to the classical genre of hypomnemata, a mode of preserving the memory of things read, heard or thought over a period of time and as such connected with the gradual development of a self projecting and designing itself through textual practices. The point about hypomnemata was, Foucault argues, "to collect the already said, to reassemble that which one could hear or read, and this to an end which is nothing less than the constitution of oneself" (Foucault 1984: 365).

In Dracula, Mina increasingly assumes control over this process of constituting the group's inward self, confirming the force of the ritual while also restraining and domesticating the exuberant and increasingly untamable energies of the male avengers. The actual point about this new constellation in Dracula is that the "self-mastery" Foucault highlights as the most prominent aspect of hypomnemata (cf. 360), has been displaced to include the group as a whole. Identifying with each other and for one another, the different members manage to dissolve their former, self-sufficient and reliant selves and merge to evolve into a higher form of communality. From now on, this new interlocuting 'self-as-other' represents the supreme standards of a true creed the group has craved for ever since the arrival of the curiously split and annihilating Dracula/Van Helsing phantom. How much this means to the group and its self-conception is made clear in the final paragraph in which Van Helsing, speaking for all characters, denies the need for external evidence and confirmation:

'We could hardly ask anyone, even did we wish to, to accept these [papers] as proof of so wild a story.' [...] 'We want no proofs; we ask none to believe us! This boy will some day know what a brave and gallant woman his mother is. Already he knows her sweetness and loving care; later on he will understand how some men so loved her, that they did dare so much for her sake.' (327)

Vamping together the different records – type-written letters, diaries, wax cylinders and memoranda – has helped close the gap opened by the Count's traumatic arrival. The work has produced coherence and new meaning in the relations between different groups of signs and levels of understanding but it cannot be denied that all this was accomplished at high costs: the collectively 'produced' child symbolizes ultimate denial of the acute loss once felt by the different group members and the specter still haunting them after the Count's destruction, namely their defeat as individuals challenged to master a severe personal crisis each for him- or herself. The classical ideal of nineteenth-century bourgeois ideology – constitution and care of the self, or carrying out one's civic responsibilities – has been undermined by this act of submergence, dissolved into the authorizing power of the other.

In its completeness, this submittal also works to include Mina who, at the end, re-emerges as a latter-day Virgin Mary in whom the other characters recognize traits such as obedience, resourceful intelligence and thankfulness – "good women, whose lives and whose truths may make good lesson for the children that are to be" (166), as Van Helsing puts it. Like the texts she has typed and supervised, she is associated with the apostolic mission the group sets out to accomplish and the quest for the 'divine script' of the good God they seek to communally reread and reinterpret in the light of their present experiences. Mina also has been wrested from the hands of the 'evil one' who never ceases to intrude upon the group, subjecting her to the role of a submissive inferior; this alone affords her a particular status in the community as one tempted but then reborn to share the gift of a new life:

And you, their best beloved one, are now to me, flesh of my flesh; blood of my blood; kin of my kin; my bountiful wine-press for a while; and shall be later on my companion and my helper. (252)

Referring the reader to Genesis (2:23),18 Dracula here claims for himself the position of divine authority, again demonstrating the will to power he shares with Van Helsing and assimilating the anxiety inherent in the group's projective activities. At one point he even burns all their texts (cf. 249), the flickering "blue flames" suggesting the burning of unhallowed texts written by heretics instead of devout followers of the true faith.19 The continuous duplication of motifs and scenes in the novel never permits one to believe that the 'good' father-figure (Van Helsing) has finally conquered Satan; everything is constantly left open, suggesting that the stakes in this struggle are eternal, and that victory is always uncertain. (The only comfort is that those who participate in this cosmic drama cannot lose, even if they sacrifice their own life like Quincey Morris who dies, a "wounded man", proud to "have been of any service" and celebrating victory with the rest of the "Holy circle" [326] at the end of the text.) The disquieting feeling remains that the inquisitors have become so caught up in the thoughts and motives of their supposed enemy that their identities are entirely dependent upon him. The object they are persecuting is actually an externalized image of the desires they continually have to repress, their violence only a self-defeating attempt to reincorporate what they have lost, an internal scene which refuses to go away;20 as a consequence, they never manage to live up to the fact that without an opponent to crush they have no power at all, and no validity – they are incomplete.21 It is thus only in their writing and their mutual encouragement that they can persecute a reincarnation of what they have never been able totally to suppress within. Requiring assurance that their traditional beliefs are not breaking down, they project all their hopes onto the modes of textual production and inscription and thus – metonymically – on Mina who, in the course of this process, is transformed into a signifier in a (male) code of loyalty and devotion informed by Christian ideas, her obedience to the associated terms and conditions a value to be passed from one generation to the next.

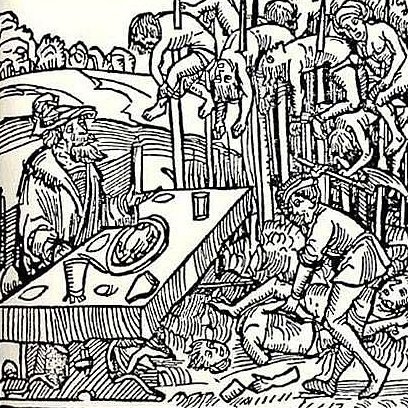

Quelle: Wikipedia Commons

One the whole, then, Stoker manages to offer a tantalizingly new denouement to the puzzle created by fin de siècle criticism of attitudes to the self and the authority ascribed to it by a secular tradition of introspection and self-examination. By shifting the burden of judgment about their anxieties and responsibilities from an external or internal authority to a process of mutual verification through signifying acts, his characters acquire a completely new outlook on the problem of salvation. Their authority and personal well-being no longer depends on their own judgment and ability but on a new form of writing-as-revelation, a deeply interwoven texture of symbols, modes and discursive patterns revealing, in their combination, a divine script illuminating every detail of their lives so as to make it meaningful. And since the laws of the 'corpus' have declared themselves in the course of its writing, no conformity with external models is expected. Freely handing themselves over to an ineffable and evasive spiritual authority approachable only through writing, the converts are turned into subjects fit only for the purpose of securing release – become, in fact, modules of a totalizing fantasy created in the realm of the Other, the space of Dracula as meta-father and master signifier. Their agency as producers of credible and verifiable texts thus secured, they can freely embark on their mission of redeeming themselves, the point of "interpretation" being that

there are insiders and outsiders, the former having, or professing to have, immediate access to the mystery, the latter […] excluded from the elect who mistrust or despise their unauthorized divinations, which may indeed, for all the delight they give, be without absolute value. (Kermode 1979: xi)

Mina's eccentric clique possesses a communication system at odds with officialdom, and it is this new contract that matters and the idea of it that establishes, in Dracula, a new inward-directed authority to rival the old: Where Dracula, messiah of the old dispensation, wishes to establish a new kingdom "founded on shared blood" (Warwick 1999: 86), Van Helsing's enlightened circle shares a vampiric hunger for textual presences, for a shared realm of exchangeable and circulating narrative possibilities legitimizing and guaranteeing a satisfactory unity of identity. This involves a transition from one realm to another – from the ancient blood-relations of race, nation and empire to the new ones of textual performance and discursive authority – and from a language of the sovereign self to a superior form of authorizing inscription in which the focus is on the dramatization of making, not on the description of a finished object. Behind its sensationalist façade, its morbidity and obsession with bodily secrets to be revealed and controlled, Dracula thus manifests the 'glad tidings' of a cluster of wary and self-modernizing selves discovering the subject of their necessary quest for truth not in a predetermined and fixed 'real' but in the process of making, weaving and joining it.

References

Auerbach, Nina (1982). Woman and the Demon: The Life of a Victorian Myth. Cambridge, MA, and London: Harvard UP.

Bronfen, Elizabeth (1998). "Jean-Martin Charcots Vampire: Die Sprache der Hysterie als Herausforderung an das Gesetz", in: Hysterisierungen, ed. Gerd Kimmerle. Tübingen: Edition diskord, 9–49.

Carroll, Robert, and Stephen Prickett (eds.) (1997). The Bible. Authorized King James Version. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Ehrman, Bart D. (2003). Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. New York: Oxford UP.

Feinendegen, Hildegard (2002). Dekadenz und Katholizismus. Konversion in der englischen Literatur des Fin de siècle. Paderborn et al.: Ferdinand Schöningh.

Foucault, Michel (1984). "On the Genealogy of Ethics: An Overview of Work in Progress", in: The Foucault Reader, ed. Paul Rabinow. New York: Pantheon Books, 359–72.

Garnett, Rhys (1990). "Dracula and The Beetle: Imperial and Sexual Guilt and Fear in Late Victorian Fantasy", in: Science Fiction Roots and Branches: Contemporary Critical Approaches. Houndmills, Basingstoke: Macmillan, 30–54.

Gay, Peter (1985). The Bourgeois Experience: Victoria to Freud. Vol. I: Education of the Senses. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hanson, Ellis (1997). Decadence and Catholicism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP.

Jackson, Rosemary (1981). Fantasy: The Literature of Subversion. London: Methuen.

Kermode, Frank (1979). The Genesis of Secrecy: On the Interpretation of Narrative. Cambridge, MA, and London: Harvard UP.

Kittler, Friedrich A. (1985). Aufschreibesysteme 1800–1900. München: Fink.

Leatherdale, Clive (1985). Dracula: The Novel and the Legend. A Study of Bram Stoker’s Gothic Masterpiece. Wellingborough, Northamptonshire: The Aquarian Press.

Nineham, Dennis (1967). The Gospel of St. Mark. Baltimore: Penguin.

Pagels, Elaine (1996). The Origin of Satan. New York: Vintage.

Pope, Rebecca A. (1999). "Writing and Biting in Dracula, in: Dracula. New Casebooks. Ed. Gelnnis Byron. Houndsmills, Basingstoke: Macmillan, 68–92.

Richardson, Maurice (1959). "The Psychoanalysis of Ghost Stories", in: The Twentieth Century 166: 419–31.

Roth, Phyllis A. (1977). "Suddenly Sexual Women in Dracula", in: Literature and Psychology 27: 113–21.

Schaffer, Talia (1994). "'A Wilde Desire Took Me': The Homoerotic History of Dracula", in: English Literary History 61.2: 381–425.

Seed, David (1985). "The Narrative Method of Dracula", in: Nineteenth-Century Fiction 40: 61–75.

Senf, Carol (1979). "Dracula: The Unseen Face in the Mirror”, in: Journal of Narrative Technique 19: 160–70.

Spivey, Robert A., and D. Moody Smith (1989). Anatomy of the New Testament. New York: Macmillan.

Stegemann, Hartmut (1999). "Jüdische Apokalyptik: Anfang und ursprüngliche Bedeutung", in: Jüngste Tage: Die Gegenwart der Apokalyptik, ed. Michael N. Ebertz & Reinhold Zwick. Freiburg i. Br.: Herder, 30–49.

Stoker, Bram (1997). Dracula. Authoritative text. Ed. Nina Auerbach and David J. Skal. New York and London: W. W. Norton.

Van Gennep, Arnold (1960). The Rites of Passage. U of Chicago P.

Vermes, Geza (2004). The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English. Revised Edition. London: Penguin.

Wall, Geoffrey (1984). "Different from Writing: Dracula in 1897", in: Literature and History 10: 15–23.

Warwick, Alexandra (1999). "Lost Cities: London's Apocalypse", in: Spectral Readings: Towards a Gothic Geography, ed. Glennis Byron and David Punter. Houndmills, Basingstoke: Macmillan, 73–87.

Notes

1 See, e.g., Pope 1999, Seed 1985 Senf 1979, and Wall 1984. A short but instructive analysis of the novel's various gadgets or machines conveying written text can be found in Kittler (1985): 449–52. My critical emphasis differs from these writers, in particular with regard to the functional uses of narrative and narrative or textual method in the context of Christian views and ideas.

2 Pagels (1995) xvii; see also Ehrman (2003: 113ff). For information on the Essenes and other Jewish apocalyptic groups of see Vermes 2004 and Stegemann 1999. The relation to the Dead Sea scrolls is particularly instructive in this respect, since it has become known that ancient scriptural copyists felt relatively free to "improve the composition which they were reproducing"; their holy texts were never identical. The "scribal creative freedom" Vermes notes in the Essenes context (23) thus resembles the different ‘redactions’ and manipulative textual interventions of Stoker’s characters.

3 The mental receptiveness needed for this act of Faith is emphasized early in the novel, in Mina Harker's remark about how some dark figures on the beach, "half-shrouded in the mist", can "see men like trees walking" (73, referring to Mark 8:24 and thus to the constant possibility, in the text, of miraculous intervention).

4 All quotations are taken from the Authorized King James Version of the Bible (ed. Carroll and Prickett 1997).

5 This proverb is reiterated in some parts of the New Testament, thus delimiting those inspired by true Pauline faith from those who stubbornly adhere to the doctrine of ancient law; see, e.g., Mark 4: 11–12, or Rom. 11:8, where Paul remarks, with an eye to the tribes of Israel: "(According as it is written, God hath given them the spirit of slumber, eyes that they should not see, and ears that they should not hear;) unto this day."

6 It should be pointed out at this point that there always has been a certain ambiguity about miracles in the NT. This scepticism can even be found in the gospel of Mark, one of the most ingenuous of New Testament texts when it comes to miracles (see Mark 3:21 f). Healing miracles always could have been the work of God or the devil; by no means did they "prove messiahship" (Spivey and Smith 1989: 197). It appears to have been part of Stoker's intention to employ, for his purpose, the very same knowledge about the reliability of miracle stories.

7 The meaning of this is not entirely clear; Renfield seems to suggest that the new age will be overshadowed by acts of unspeakable terror. This is reinforced by the fact that the zoophagous madman prepares himself for the new dispensation by consuming small animals. Indeed, he positively fattens on them, first making spiders consume small flies, then a bird the spider, and finally consuming the bird himself. This sequential introjective phantasy is important as it points the reader to the intended union between the Lord (Dracula) and his 'bride' (Renfield).

8 Another reference to the NT (Matt. 10:29): "Are not two sparrows sold for a farthing? and one of them shall not fall on the ground without your Father."

9 This transpires when Van Helsing's use of a communion wafer to brand Mina's forehead suggests occult practices going far beyond the pale of traditional Catholic ceremonies (187). What is at stake here is indeed the question whether Stoker, being Irish and a confirmed Protestant himself, had in mind a critique of Britain's Catholic heritage. For details on this issue see Leatherdale 1985: 195.

10 The almost insane form this mutuality assumes is reflected in the child who, at the novel's end, is seen as a result of the group's spiritual communion and common effort rather than the product of a sexual union between one man and one woman. The alliance created through writing is so strong that with Renfield they even accept a veritable madman into their "Holy circle" (318, 326).

11 In this respect, their Gospel does indeed represent a new 'Tract for the Times', providing a language and mode stabilizing itself through discursive interaction in times unstable and deprived of solid and reliable patterns of recognition. Like the early Christian texts, their compilation places a new scriptural canon at the center of life as a replacement for the ruined 'Temple' of a previous order.

12 There were exceptions, of course. For details, see Peter Gay's inspiring exploration of Victorian bedrooms in his Education of the Senses (Gay 1985: 111–33).

13 See especially the pages 62, 88 and 106.

14 Van Helsing verifies this resemblance when he, en passant, drops a comment on the Count: "He cannot go where he lists" (211). The statement calls to mind John 3:8, "The wind bloweth where it listeth", in which the Holy Spirit is equated with the wind's liberty to go where it wants. Beyond that, the statement also renders visible Van Helsing's marked competitive ambitions, his 'fraternal' jealousy and resentment of the Count who continuously appears to be one step ahead of his persecutor.

15 In the face of Mina's uncertain role, Rebecca Pope acknowledges a double structure in the text, a "consistent weaving of two (opposing) logics – represented by the patriarchal textualising of women on the one hand and, on the other, a female appropriation of textuality as a means of restricting patriarchy and its strategies." (Pope 1999: 89)

16 Rosemary Jackson has remarked that the scene "remains one of the most extreme inversions of the Christian myth. [...] It blasphemes against Christian sacraments – [...] The vampire baptism in which Mina is 'tainted' has elements of a travesty of the Mass." (Jackson 1981: 119) A similar point has been made by Rhys Garnett in her comparative reading of the text (see Garnett 1990: 49f). I cannot agree with her view, however, that the conflict between faith and science as deployed by Stoker is resolved in favour of "faith, to which science becomes secondary and subordinate." (50)

17 See the scene of Lucy's violent impalement on p. 192f.

18 The highly ambiguous scene also recalls NT texts Rev. 19:15 and Matt. 21: 33–34, however: "Hear another parable: There was a certain householder, which planted a vineyard, and hedged it round about, and digged a winepress in it, and built a tower, and let it out to husbandmen, and went into a far country: And when the time of the fruit drew near, he sent his servants to the husbandmen, that they might receive the fruits of it."

19 It has to be remarked that it is Lucy, of all characters, who feels uncertain about her transgressive desires and describes them in religious terms as "heresy" (60).

20 The exaggerated erotic or sexual nature of many descriptions needs no comment here; readers differ with regard to clarifying the specific form(s) of repressed sexuality explored in the book, however. While Phyllis Roth recognizes a strong preoccupation with the "primal scene in oral terms" (Roth 1977: 116), Maurice Richardson highlights the multitude of fantasies acted out in Dracula which he defines, rather broadly, as an "incestuous, necrophilous, oral-anal-sadistic all-in-wrestling match" (1959: 427).

21 This is another aspect relating the narrative to the New Testament gospels; see Frank Kermode who made the point that the figure of Judas in the gospels is, first and foremost, a function of the narrative which needs an opponent for Jesus (Kermode 1979: 85f).

|

|