"Long-lost Blake Paintings Fetch £ 5m"

Addendum (March 2003)

Karl Josef Höltgen (Erlangen)

According to a number of recent press reports1 the nineteen watercolours by William Blake for Robert Blair's poem The Grave have now been sold for a record price of more than £ 5 million.2 This is considerably more than Dominic Winter, the Wiltshire auctioneer who arranged the verification and first assessment of the treasures by Blake experts, had originally expected, i.e. over £ 1 million. A private sale to an anonymous overseas collector took place after the settlement of a High Court battle over ownership. The publicity generated by the court action may well have pushed up the price but the staggering amount can only be explained by the absolute uniqueness of these works of Blake and their unusual provenance and discovery. In 2001 two booksellers from Ilkley, Yorkshire, found them in a Glasgow secondhand bookshop, bought them and took them to Dominic Winter. A London art dealer who eventually negotiated the sale compares the extraordinary find to that of the Dead Sea scrolls. The discovery resulted in a huge financial windfall for those lucky booksellers in Ilkley and Glasgow. It has brought to light lost artefacts of great cultural value, extended Blake's canon and stimulated Blake scholarship. The full significance of the nineteen watercolours will, one hopes, be revealed in a future critical edition.

In his magisterial new biography of Blake, The Stranger from Paradise (Yale 2001), G.E. Bentley, Jr calls the publisher Robert Cromek Blake's "sometime patron and bête noire". Apparently Blake produced no less than forty drawings intended for The Grave. Cromek accepted only twenty, for a fee of £ 31. The artist turned them into finished engravable designs in 1808. They must represent the nineteen recovered watercolours and an unexplained additional one. The fee was truly miserable as it included the publishing rights for The Grave with twelve engravings which Blake had expected to do himself but were given to Schiavonetti instead. This work saw five editions from 1806 to c. 1874. They account for different states of the plates. Around 1812 Cromek's widow Elizabeth was able to finance the engraving of Stothard's The Canterbury Pilgrims (a rival picture to Blake's work of the same name) by selling the plates of The Grave to the art dealer Ackermann for £ 120. However, she received only one pound and five shillings when she sold the nineteen watercolour designs in Edinburgh in 1836. They disappeared and fell into oblivion until their rediscovery in Glasgow in 2001. Some record of them survived in the form of the twelve published engravings. Scholars are now waiting to see the nineteen watercolours, to find out how these nineteen relate to the twelve engraved plates and how the two art media differ in style and effect.

The watercolours have never been seen by the public, with the exception of some members of the Royal Academy, artists, critics and connoisseurs like Fuseli and John Thurston and Joseph Thomas (the authors of Religious Emblems, 1809) for whom Cromek would have made special arrangements. These previews, together with a subscription list and Cromek's Prospectus of November 1805 brought about useful pre-publication sales promotion for The Grave. Cromek quoted in the Prospectus Fuseli's appreciative observations on the watercolour designs. He also exhibited a "Specimen of the Stile of Engraving" in his house, possibly Death's Door, Blake's only engraved plate for the series which was, however, excluded from The Grave in favour of Schiavonetti's print of the same design (see Martin Butlin, William Blake, Exhibition Catalogue, Tate Gallery, 1978, nos. 152, 153. Watercolours nos. 156 and 158 are also related to The Grave).

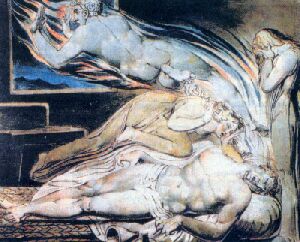

One sample of the watercolours has now been published in the press, a colour print of the Death of the Strong Wicked Man, the most striking of all:

Photograph: DOMINIC WINTER

It shows how the violent facial expression and convulsive body language of the hardened sinner on his deathbed as portrayed in the black and white version can be intensified by colour:3: the pale flesh of the dying man and his "corporeal" soul, the brown garments of the despairing wife and daughter, the black and blue of cold and lifeless space behind the open window and the orange, blue and white flames hurling the sinner's soul toward eternal damnation. If this chamber of horror seems too much for an "improving book" one should realise that it also offers the consolation of The Death of the Good Old Man and the joy of The Meeting of a Family in Heaven.

Notes

1 See the following Web sites:

2 See my previous article on Blake's emblems (EESE 2/2002).

3 See fig. 13 and fig. 14, ibid.