EESE 9/2007

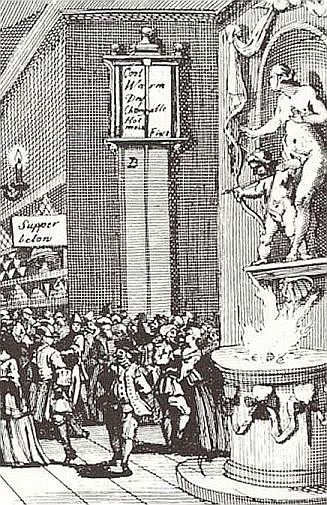

The Faltering Spirit of the Nation in the 1720s: |  "Cool – Warm – Dry – Changeable – Hot – Moist": "Cool – Warm – Dry – Changeable – Hot – Moist":Hogarth's "Lecherometer" (detail from "The Masquerade Ticket", 1727) |

It may be a commonplace in English history that the Societies for the Reformation of Manners tilted at the windmills of "necessary liberties",[1] even if their activities in the 1720s, as the number of convictions significantly rose, seemed to have achieved the success hoped for during a brief period. Under the raw capitalism of the post-revolution era and the impact of its secularisation, the English nation notoriously suffered from a lack of moral fibre, or as Paulson put it in the commentary on Hogarth's "Masquerade Ticket": "A social phenomenon stands secondarily for a political one; the point can be read either way: politics is reducible to sexual desire, or sexual desire is at the bottom of Britain's troubles."[2] Permissiveness appears to be the principal result of the ongoing processes of urbanisation and secularisation. Bishop Francis Hare, one of the great minds of early 18th-century England and a prominent political churchman,[3] preached on many festive and important occasions to the Whig establishment. Hare's 1730 sermon on, as I would like to put it here, encroaching secularization, or rather, on the achievements of the Societies for the Reformation of Manners provides a unique piece of cultural and ideological criticism for the period.[4] Thus Hare's sermon provides an invaluable source of information on the awareness of cultural change among the Anglican clergy.

Hare's Christian idealism shining through his statement on the prevalent decay of the nation's morals contrasts with the many voices of critique of contemporary capitalism as most prominently voiced in John Gay's Beggar's Opera just one year before. Viewing the state of society in early 18th-century London, one can easily draw the conclusion that moral campaigning proved to be one of the most obvious measures when expectations had begun to outrun the capacity to cope with reality. The problem is that there are acknowledged cultural norms ("Necessary Liberties"[5]) everybody is supposed to share and there are those rules the system forces upon the individual including the law of the jungle. In his many reports on everyday life in London around 1700 Edward Ward, better than any other writer of the period, created a multitude of London characters who just qualified for predators whatever their official role in society. In the decades after the Glorious Revolution, this is a conflict arising in the process of modernising English society: Christian tradition and secular law are seemingly at odds. This paper is to contrast Ned Ward's survey of the metropolis which ran into the 1720s to Bishop Hare's account of how middle-class democracy could fulfil the requirements of Christian society in an age of moral crisis.

As self-appointed devisers of the norm, or, to be fair, encouraged by the monarchs, the Societies for the Reformation of Manners go down in history as a morals police – "particularly pertinent to urban adolescent males, to the youths and apprentices"[6] – created as a "private initiative for public benefit, as a collective responsibility for individual sin". Given the current absence of adequate police forces in the metropolis right after the Glorious Revolution, the societies were to keep alive the fear of divine retribution similar to the apocalypse of the mid-seventeenth century and the belief in the law warranting a reformation of manners "through prosecution and criminal punishment, a strategy chosen by the Puritans of the seventeenth century as well as by the SRMs."[7] However, times called for measures to maintain social order against the pressure from problems such as poverty, crime, and disorder.[8] According to Rose, "the most distinctive characteristic of these reformation societies was their ecumenism." From the very start, they had to operate along a fault line against the "avowed enemies of the inter-denominational" activities.[9]

Was there, at least in the seventeen-thirties as the Reformation of Manners movement petered out, a growing recognition by the leading moralists such as Francis Hare, one of the most prominent controversialists of the age, that the theological modes of relating man to reality and to afterlife might in themselves have severe limitations? Sin could startle the London public no longer, but with the gin crisis worse was to come – meaning both the devastating effects on the lower classes and the political-economic involvement by the then prime minister, Robert Walpole – and new measures, or, more fundamentally, new thought had to be envisaged in order to grasp the effects of new structures underlying everyday experience. Adam Smith had finally acknowledged the impact of market-forces on human society: utilitarian, demand-driven, consumerist, hedonistic.[10]

Originally founded in 1690 in the Tower Hamlets, the Societies, however, had been a forceful social movement in early eighteenth century England, owing their origin to a moment of crisis (an unprecedented wave of crime) and to the enthusiasm for voluntary 'social' work and for spiritual improvement. The evolution of the movement should be understood in terms of how cultural norms are imposed upon society and validated against the process of change and in terms of their failure.

The 1720s mark the first decade of Robert Walpole's reign as prime minister (1721-42) in the period of Whig supremacy, due to which public interest in politics diminished, and the impact of modernisation and secularisation made itself felt to a larger part of the population.[11] Worst of all, the South Sea Bubble, i.e. the first stock-exchange crash in the modern world of finance, caused long years of trauma.[12] Raw capitalism was showing its ugly face. This was also the decade of hedonism, of unbridled lust and uncontrollable greed which seemed to have replace religious strife. Handel's Italian opera veered towards its untimely demise; masquerades having taken over the venue of the opera. However, pleasure was unlimited; in 1726 36 different plays were staged by London theatres. In 1727, the coronation banquet of King George II displayed a hitherto unseen sumptuousness as food and drink dominated the new consumer society. Problems of digestion and corpulence became the principal concern of Dr George Cheyne culminating in his famous study on The English Malady (1733). The authorities interfered with popular masked balls both for their parody of established society and for the importance of the ever growing London scene of homosexuals.

Literature reacted, as satire reached its bleakest peak: Swift's Gulliver's Travels (1726), Pope's Dunciad (1728), Mandeville's Modest Defence of Public Stews (1724), Swift's Modest Proposal (1929), Gay's Beggar's Opera (1728). Young Fielding attacked Heydegger, the famous organiser of operas and parties, in his poem "The masquerade" (1728), and Walpole in his farce Tom Thumb: a Tragedy (1730). Pat Rogers suggested "After the Deluge" as a fit subtitle for Defoe's Tour through the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724), emphasizing the overthrow of accepted social values as the book's pervading theme.[13] Defoe's novels of human predators, females in particular, Moll Flanders (1722), Roxana (1724), which he wrote after Robinson Crusoe, give ample evidence not only of the seamy side of London life, but of modern society. As the minority voice of the decent majority, Steele's Conscious Lovers (1722), his last play, seemed to be out of tune. As it was, Hogarth, in his early career, caught the spirit of the age in works like the "South Sea Scheme" (1721), the "Masquerade Ticket" (1727) with its notorious "lecherometers" and, finally, the "Sleeping Congregation" (1728). The twenties were the decade to be fittingly characterized as lecherous. Unsurprisingly, it was the age when the Societies for the Reformation of Manners were needed and when their score soared.[14] According to the historian's verdict, the prime minister was the true figurehead of the age: "Both in public and in private Walpole enjoyed living life to the full at other people's expenses."[15]

Some 15 years after being launched, the Societies had gained notoriety, although their finest day in the early 1720s was still to come. Who really were the 'Reformers'? Membership lists obviously have not been unearthed yet.[16] We must therefore rely on contemporary evidence, whatever the appearance of the Societies' agents and the fallacy with which they were described and whatever the distortions by satire on informing and corruption. The Societies' agents prominently feature in Ward's London, and Ward was their principal detractor, as it appears. So it makes sense to line up Ward and Bishop Hare to throw new light on the question of how efficient an official moral policy really proved.

Disturbed by the rise of the Dissent, which Bishop Hare bitterly resented for all his life, many writers of the period attacked them as a menace to the nation, as Ned Ward described the presence in everyday life of a social phenomenon which was hardly adequately rendered in the annual sermons of the Societies. This is the raw material of reality, which poses a problem of categorization between the historian's reasoning and the extreme of emotion experienced by the writer who bore, fictitiously or not, witness to social change. So we can take this picture of London night life from "Hudibras Redivivus: or, A Burlesque Poem on the Times" (1705-07) for granted. "Hudibrastic" refers to Samuel Butler's anti-puritan satire the first part of which was published in 1663.[17] In an age still dominated by religion, the Calvinistic fusion of religious fervour and acquisitive behaviour was a scandal to many. The hypocrisy of Dissenting capitalists was Ward's principal object of attack.

Ned Ward still defined status in terms of the ownership of land; he was a bestselling author, a middle-of-the-road Tory and a staunch supporter of the Church of England, although once fined and pilloried when he had attacked the Queen herself for leniency to the supposed enemies of the Church.18 In the following Hudibrastic verses, Ned Ward’s objections are made plain. Whatever the statements from the throne and the leading prelates of the Church of England encouraging the Societies, the Reformers are of substance radically Dissent or Low Church rather than Church establishment, which is a fact one has to keep in mind. "The Saints", as continuously denounced by Ward, are driven, first of all, by their material interest, masked by their religious fervour. The number of prostitutes in the streets of London steadily increased in spite of the Societies' combined efforts and made the concomitant phenomenon of corruption the more visible, "Those Paramours of Pimps and Bayli's,/ Creep out from Garrets and from Allies, /Pursu'd by poor reforming Rogues, /As Bitches Proud by Curs and Dogs". In Ward's eyes, the Dissent has sunk into the mire of vice and corruption, but due to their political representation, "faction", as he calls it derisively, the Protestants are protected by the press, their opinion leaders, as long as England is haunted by the ghost of the radical Rump Parliament. Moreover, Ward's observations remind one of a piece of inspired historiography by Bristow on the operations of the Societies. I call it 'inspired', because Bristow has omitted any factual evidence apart from a possible reference to Woodward's popular Disswasive from the sin of drunkenness (1701); what he says, however, makes a lot of sense, when the agents were briefed for service in the trenches:

Some of the Religious Societies formed themselves into groups of informers. Whipped into a frenzy of indignation at prayer meetings and armed with a handbook describing, among others things, what it looked like to be drunk, they showed little mercy to the poor.[19]

Historically, "Hudibras Redivivus" describes modern society as shaped by the Dissent:

'Twas now about that Hour of Night,[20] |

The famous moral weeklies produced by Steele and Addison may be considered the nucleus of the rising middle-class culture of England. Both the Tatler and the Spectator bring a different point of view to this. Normally they just do not take any notice of what some historians now consider an important social movement, or they refer casually and ironically to it demonstrating their disregard. On a rare occasion, in Spectator No. 8 (9 March 1711), a letter from the director of one of the societies is printed. If this piece is authentic or just a fake by a clever journalist must still be decided by researchers. What should be definitely viewed with suspicion is the director's claim to being at the controls of the whole nation, presumably not only morally, and his pedant's stubbornness and the fanaticism with which the organisations have been spread street by street all over England. This craze for keeping the nation under constant surveillance is nothing less than a parody of the societies' self-display in many pamphlets. In the following, the director refers to a "Midnight Masque" which shows that the maxim is still accepted that vice is practiced by the respectable in private, while by the poor in public, which makes all the difference and which, in turn, takes up the powerful argument used by Defoe and Swift and others against the Reformers: "As all the Persons who compose this lawless Assembly are masqued, we dare not attack any of them in our Way, lest we should send a Woman of Quality to Bridewell or a Peer of Great-Britain to the Counter." (Spectator 8, 9 March 1711). Even Steele's way of dismissing claims for censuring the British stage or Tickell's casual remark in the Tatler, in 1709 and 1714 respectively, aim at bringing home to the Reformers their cultural defeat and their marginality: "The remonstrance of T.C. against the Profanation of the Sabbath by Barbers, Shoe-Cleaners, &c. had better be offered to the Societies of the Reformers." (Tatler 619, 1714). This sounds like letting his own side down, as, surprisingly enough, Steele seemed to have belonged to the active members of a Society.[21]

The label of zealous fundamentalism stuck to the Reformers. Patrick Dillon argued that "The high church maverick Henry Sacheverell had criticised the Societies' campaigns as 'the unwarranted effects of an idle, incroaching, impertinent, and medling curiosity [...] the base product of ill-nature, spiritual pride, censoriousness and sanctified spleen."[22] In his 1709 Sermon on The Communication of Sin, Sacheverell had attacked the Societies' tolerance to dissenters among their ranks.[23] Francis Hare, the then Bishop of St. Asaph and Chichester and nearly Archbishop of Canterbury and former tutor to Robert Walpole held similar views for all his life.[24] How important this argument still was in the early 1730s, can be seen in Hogarth's Harlot's Progress, Plate no. 3 (1732), entitled "Apprehended by a Magistrate" and referring to events in the preceding year. The evangelical magistrate Sir John Gonson, the most famous harlot-hunter of the period, appears in the rear and is counterbalanced by the portrait of Sacheverell in the foreground. Obviously, although siding with Captain Mackheath on the other portrait, the notorious preacher does not stand for chaos and disorder, but for his legendary defence of high-church interests and decency – two champions "of the right of the poor against the busybody reformers".[25] The longevity of the conflict between High Church and Low Church may be telling, and it easily escapes the reader. The butt of Hogarth's emblematic criticism is the Walpole system; Hogarth leans on a nostalgic Tory vision of a better past before the dawn of capitalism, which had many prominent followers at the period.

In the following I would like to discuss point by point the tenets of Christian culture in Francis Hare's Sermon Preached to the Societies for Reformation of Manners in January 1730.Bristow takes up a quote by the Bishop of St. Asaph to summarize his main concern: "If the People of lower condition are at all reformed, the Societies are justified."[26]

After the South Sea Bubble and the gin craze increasingly making itself felt in the metropolis, the Societies' activities had reached a peak with nearly 7000 convictions in one year in the early twenties. But reality had definitely changed its face. Men like Sir John Gonson, the driving force behind the movement, "had lifted the curtain on life in the slums, and found nothing but depravity" [27] and were striving for political action. In principle, Hare's suggestion cannot be dismissed, however far from reality or practicality it was.

This is the point I would like to take up in detail. Given the gin craze with its ever more devastating effect on the London population and the economic interest behind it, i.e. a small number of wealthy brewers and distillers and Walpole collecting tax money from them to ensure his own survival as prime minister under George II and to prevent legislation against the gin industry, the condition of England should have raised the question of how far the system of early capitalism and individual interest (see Mandeville) actually was to be recognized as such, if one did not opt for Old Testament fundamentalism. So what were the categories of Hare's discourse on the crisis of a nation obviously "false to itself" (4)? What was in the multi-columned ledger of the Societies apart from roughly 100.000 convictions for various offences? The societies were in the grip of book-keeping mania. Obviously, the metropolis had changed for the worse, reality – or was it just human nature under the conditions of capitalism – resistant to improvement. No single factor, however, appears decisive. Can we talk, in general, of cultural norms both traditional and post-Glorious Revolution ones failing and invalidating the Christian world picture and sapping the determination not to be bowed in the face of sin and vice? Obviously, Hare cannot give up Christianity and become an English social engineer of the 20th century Welfare state. I would like to sum up his argument in a few points:

- Living conditions in the metropolis due to population growth

- The conspiracy of evil emanating from the "houses of the vicious"

- The middling classes are the backbone of the nation.

- Righteous Laws and Legislation – the failure of the system

- Informing is the breach of a central cultural norm.

- The moral elite

- Education and the family

- Philosophy: the risk of liberty and the failure of the enlightenment

This means that the system of Christian norms cannot cope with migration in England and the concentration of a large part of the British population in London:

The immediate general cause of most Villanies is certainly the extreme Misery and Poverty great numbers are reduced to; but whence comes this Misery and Poverty? Come they not from a want of honest Industry, and of an early Education in the Principles of Piety and Virtue? The want of this has made Men vicious, and Vice has made them poor.(30)

The following quote reminds one of the famous passage in Book IV of Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels describing the state of England:

For these Places are the Nurseries of all kinds of Impiety and Vice, the Harbours of lewd Women, who could not swarm as they do in our Streets, if they had not these Places to retreat to; the receptacles of Sharpers, Thieves, Gamesters, Bullies, and what not. Nothing is to be seen or heard in them but profane Cursing and Swearing, Lewdness of all kinds, Drinking, Gaming, Cheating, Fighting; nothing but what tends to the Destruction of Estate and Health, Parts and Reputation, to make a distemper'd Body, and infeeble and enervate the Mind, and render it insensible to every thing that is wise or good; nothing in short but what tends to the Ruin of the whole Man, Body and Soul, here and hereafter. (26-27)

[...…] are the middling People, the lower Orders of Men, more vicious than they were formerly? If they are not, the Objection affects not these Societies, for it is to these latter sort chiefly, if not wholly, they confine themselves; these are the men they endeavour to reform, upon whose Industry and Virtue the Strength and the Riches of the Nation so much depend." (23)

The system does not work because of corruption and political networking, which, by definition, are the same:

Whence is it we feel so little effect from such wholesome and good laws?"- "The Laws cannot execute themselves, they are but a dead letter." (6)

Why, when it is so much in the Power of the Magistrate to hinder it, do Profaneness and Immorality so often go unpunished? (7)

Vice, they fear, has a strong Party on its side, and wicked Men seldom are without their Confederates and Friends. (8)

Some would insinuate as a reason of neglect in some Magistrates, a cause much more blameable than any of the former, and that is, the love of unrighteous Gain, which tempts Men to sell Justice, and make a Trade of the Powers committed to them. (12)

'Tis possible indeed the remissness and neglect of Magistrates in not executing the Laws against Prophaneness and Immorality may sometimes proceed from a cause less scandalous than some of those I have mentioned, but not less pernicious; and that is Party Rage and Malice. (13)

This obviously derives from the Cromwell era. Informing proved the Achilles heel of the movement as informers had never been accepted by the public, although they were necessary in court. Thus Hare was fighting a losing battle, whatever his reasons in favour of informers, which is rather an embarrassing whitewash. His rhetoric is getting more and more pompous:

But could men distinguish a little, and raise their Minds above vulgar Prejudices, they would see this point in quite another light. When Information is given to a Magistrate against profane and immoral Practices, from an honest Heart, that fears God and loves his Neighbour, when it stands clear of all imputations that can in the least blemish it, when it is not done for reward or to get Money by it, when it proceeds not from personal Pique or Revenge, but from disinterested Views, and a real concern for the Publick good, and even for the Party offending, when it is not made in Secret and in the Dark, but dares to come into the open Light, and he that makes it is ready not only to accuse, but to prove, what has such an Information in it that is odious besides the Name? (19)

A second paradox connected with it was the idea of the moral elite and their "conduct above reproach", which, in politics, especially in the aftermath of revolution, has always been the supreme illusion. In his 1702 satire on reforming Defoe had already expressed serious doubts.

And whatever Success they may have in reforming others, they can't possibly give a greater proof of their own Piety and Goodness; they have put themselves under a Necessity of being strictly Virtuous, since otherwise they could not fail to draw upon themselves the severest Censures. (21)End of quote – what they actually did.

How to rescue the English nation?

Indeed our Schools themselves are in general on a sad Foot, and highly deserve the Consideration of the Legislature, how to render them more useful; that the Time which is now employed for many years, and a great Expence, to learn nothing, or what to the greatest part will never be of any use, may be spent in forming their Minds and Manner to the best Advantage […]. (32)But secularisation had made deep inroads into the culture:

The Skirts of the Town on a Sunday Morning, in tolerable Weather, are as crowded with Sights of this kind, as if People were posting to some Fair or market; a most scandalous Sight, and a very great Indication of the dissoluteness of our Manners, and remissness of Family-Government. (38)

'Tis in vain to talk of the Decay of trade, or to complain of the increase of Vice, while private Families are so ill governed, and Luxury and Idleness take the place of Frugality and Industry. There lies the Root of the Evil, and till that is removed, all that either Magistrates or these Societies can do, is comparatively little. (42)

If this Care was ever necessary, it is so now, not only from the great increase of Profaness and Immorality, and the terrible effects we feel, (and more we have reason to apprehend from them) but from the prodigious increase of the Town, which is become in some sort the whole Kingdom, such vast Numbers from all Parts constantly resort to it. (43)

It is in truth come to that pass, that Licentiousness has taken the place and name of Liberty, and nothing is thought Liberty, which does not leave Men an unrestrained Power of saying and doing what they please, at least in every thing relating to themselves. Reasonable Liberty is a Language they don't understand; Liberty in their opinion, ceases to be so, the minute it comes under rules and limitations. (44)Of course, quite understandably, the press is the origin of moral decay:

There is the same reason for restraining Liberty in the Subject as there is for limiting Power in the Prince [...]. (46)

Licentiousness every where prevails, and we feel the sad effects of it; it has produced [...] such a contempt of all Authority, whether Sacred or Civil, as was never before known in this Nation [...]. especially since this great Licentiousness of Manners is accompanied by a no less Licentiousness of the Press [...]. Infidelity is propagated with the greatest Industry, and religion treated as mere Imposture, an imposition upon Mankind [...]. The Licentiousness of this kind has been many Years growing upon us, but a love of Liberty would not let Men timely see what was aimed at. (47)Hare's conclusion, however, is, in a way, timelessly true: "How can Society subsist, if publick and private Faith, which are the cement of it, are destroyed?" (49)

As it appears, eighteenth-century culture could hardly be steered to something like social engineering and more sophisticated and job-oriented economic policies, and the underlying power structure took long to be changed. Defoe and Mandeville did the first vital step in modernising the appropriate paradigms of thought. Understandably, Hare was unable to adopt to the new conditions. Modern secular society can hardly be managed on the lines of public and private faith, however important they are.

Notes

[1] A minister complaining about the indifference of justices of peace referred under this heading to the new secular cultural norms; cf. Thomas Newman, Reformation or Mockery, argued, from the general use of the Lord's-Prayer: A Sermon Preach'd to the Societies for the Reformation of Manners at Salter's Hall, June 30, 1729 (London, 1729), 28.

[2] Ronald Paulson, Hogarth. Vol. 1: "The Modern Moral Subject" 1697-1732 (New Brunswick and London: Rutgers University Press, 1991), 169.

[3] Hare was offered the post of usher of the Exchequer by Walpole in 1722 and was later 'shortlisted' for the see of Canterbury; see Alexander Pettit, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, s.v. Hare (www.oxforddnb.com); Pettit, "The Francis Hare Controversy of 1732," British Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies 17 (1994), 41-53, here: 42; see the chapter "Vom geistlichen Gelehrten zum Prediger der Kriegsfraktion" ['from the learned reverend to the preacher of the war party'] in the exhaustive study by Jens Metzdorf, Politik – Propaganda – Patronage. Francis Hare und die englische Publizistik im Spanischen Erbfolgekrieg (Mainz: von Zabern, 2000), 78-97; and Heinz-Joachim Müllenbrock, The Culture of Contention. A Rhetorical Analysis of the Political Controversy about the Ending of the War of the Spanish Succession, 1710-1713 (München: Fink, 1997), passim. Hare was appointed Chaplain General to the Duke of Marlborough and the keeper of his military journal, cf. Robert D. Horn, "Marlborough's First Biographer: Dr. Francis Hare," Huntingdon Library Quarterly 20: 2 (1957), 145-162, here 147.

[4] A Sermon Preached to the Societies for Reformation of Manners (January 1730).

[5] See also Shelley Burtt, "The Societies for the Reformation of Manners: between John Locke and the Devil in Augustan England," The Margins of Orthodoxy. Heterodox Writing and Cultural Response, 1660-1750, ed. by Peter Lund (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 163.

[6] Cf. John Spurr, "The Church, the Societies and the Moral Revolution of 1688," The Church of England c. 1689 – c. 1833 , ed. by . John Walsh, Colin Haydon, and Stephen Taylor (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 136.

[7] Ibid., 156.

[8] Cf. Robert B. Shoemaker, "Reforming the City: The Reformation of Manners Campaign in London, 1690-1738," Stilling the Grumbling Hive. The Response to Social and Economic Problems in England, 1689-1750, ed. by Lee Davidson, Tim Hitchcock, Tim Keirn and Robert B. Shoemaker (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1992), 99.

[9] Craig Rose, England in the 1690s: Revolution, Religion and War (Oxford: Blackwell, 1999), 207; 209.

[10] Cf. Roy Porter, "Enlightenment and Pleasure," Pleasure in the Eighteenth Century, ed. by Roy Porter and Marie Mulvey Roberts (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1996), 17.

[11] Cf. Julian Hoppit, A Land of Liberty? England 1689 – 1727 (Oxford: Clarendon, 2000), 417.

[12] Cf. Pat Rogers, The Augustan Vision (London: Methuen, 1974), 106; George Rudé, Hanoverian London 1714-1808 (Phoenix Mill: Sutton, 2003 [1971]), 34-35. Rudé refers to Maitland's account in the History of London (1806). For the rise of the oligarchy and the middle classes see Paul Langford, A Polite and Commercial People. England 1727-1783 (Oxford: Clarendon, 1989), chap. 3.

[13] Augustan Vision, 106.

[14] Cf. for a good survey Terry Castle, Masquerade and Civilization: the Carnivalesque in Eighteenth-century English Culture and Fiction (London: Methuen, 1986). One of the best descriptions of a masked ball was provided by Ned Ward, The Amorous Bugbears (1725).

[15] Hoppit, A Land of Liberty?, 442.

[16] Cf. Edward J. Bristow, Vice and Vigilance. Purity Movements in Britain since 1700 (Dublin: Gill and Macmillan, 1977); see, however, Shoemaker, "Reforming the City".

[17] In Ward's generation Butler was held in high esteem. Hudibras was reprinted in 1704, 1710 (with illustrations) and in 1726 with illustrations by Hogarth. See Paulson, Hogarth, Vol. 1, 142-49.

[18] See the hitherto only monograph by Howard W. Troyer, Ned Ward of Grub Street. A Study of Sub-Literary London in the Eighteenth Century (London: Frank Cass, 1968 [1946]).

[19] Bristow, Vice and Vigilance, 18.

[20] Hudibras Redivivus; Or, A Burlesque Poem on the Times (London, 1705-1706).

[21] See Bristow, Vice and Vigilance, 19.

[22] The Much Lamented Death of Madam Geneva (2002).

[23] Burtt, "Societies for the Reformation of Manners", 58.

[24] Cf. Alex Pettit in DNB.

[25] Bristow, Vice and Vigilance, 19. This seems to be more to the point than Ronald Paulson's sophisticated reference to an underlying discussion of deism. Paulson, however, is not wholly consistent with the combination of High-Church ideology and the concern for poverty and squalor among the lower classes. See Paulson, Hogarth. Vol.1, 20-21, 294-95, 298-99.

[26] A Sermon Preached to the Societies for Reformation of Manners: at St. Mary-le-Bow, on Tuesday January the 5th, 1730. By ... Francis Lord Bishop of St. Asaph (London, 1731), 24; unless otherwise noted, I am quoting from this microfilmed edition.

[27] Dillon, Madam Geneva, 44.