EESE 7/2007

Title-pages and Frontispieces

of Popular Accounts and Newgate Calendars (1600-1870)

Uwe Böker (Dresden)

Title-page and Frontispiece: Their Economic Function

The eighteenth-century prison had various functions.56 Prisoners were confined while awaiting their trials or the execution of a sentence; petty offenders were often sentenced to short terms of incarceration, as were those held for vagrancy. Although there were special prisons for debtors in London, as the Fleet and the Marshalsea, even in Newgate there were a great number of people imprisoned for debt, often living there together with their wives and children. According to Daniel Defoe's Tour through the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724-26), one might have found, at the beginning of the eighteenth century, "more public and private prisons, and houses of confinement [in London], than in any city in Europe, perhaps as many as in all the capital cities of Europe put together". Defoe's long list of prisons includes the famous Newgate, which, for his fictional character Moll Flanders, was a "dismal Place: [...] the hellish Noise, the Roaring, Swearing and Clamour, the Stench and Nastiness, and all the dreadful crowd of Afflicting things that I saw there [...] make the Place seem an Emblem of Hell itself".57 People in real life were of a similar opinion, comparing Newgate a "tomb for the living". Thus, for Capt. Alexander Smith, in his popular collection of criminal biographies, it was a "place of calamity, [...] a confused Chaos [...] a bottomless pit of violence, and a Tower of Babel, where all are speakers and no hearers". No wonder than that Newgate was associated with a special kind of criminal narrative, the so-called Newgate Calendar. These publications will be analysed later on.

In the case of some of the official or semi-official publications of trial accounts there are similar kinds of layout which already hint at a new development: title-pages and frontispieces emphasise the authenticity of the materials included in a trial account. This is the case with The Arraignment, Tryal and Condemnation of Stephen Colledge for High-Treason [...] (1681) with a frontispiece of the accused in half-profile looking at the reader.71 Underneath the rectangular half portrait in running script there is the name of the accused, and, in the second line: "The Protestant Joiner". Another noteworthy example is The Whole Proceedings [...] against Simon Lord Lovat, for High Treason,72 with an engraved replica of William Hogarth's familiar portrait; on the title-page the printer mostly used Roman (upper case and italics):73

Lord Lovat was one of the highland rebels of 1745 who had been beaten at Culloden; when he was sent to London as a prisoner, he was visited by Hogarth on his way to the capital: he is depicted sitting on an arm-chair, counting the clans that fought for the Pretender; on the table on his left are his "Memoirs", as well as a pen and inkstand. Hogarth's portrait proved to be one of his most popular etchings; over a period of several weeks Hogarth daily earned £12 for this work, and during the execution of Lord Lovat there were more people interested in getting hold of a copy.74

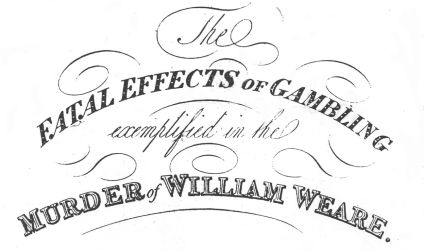

One of the most spectacular cases during the eighteenth thirties was John Thurtell's and Joseph Hunt's murder of William Weare (1824).84 The publication under discussion has two different title-pages following one another: a first one richly ornamented which is opposite the frontispiece (fig. 7), the other one giving the title itself, together with the contents ("biographical sketches of the parties concerned; Gambler's Course; a Complete Exposé of the whole System of Gambling in the Metropolis"). The printer used a variety of fonts (fig. 8): Egyptienne, i.e. slab seerif; black letter and classical antiqua, upper case. There is, in addition, an Epigraph from a play: "— Shame, beggary, and imprisonment, unpitied misery, the stings of conscience, and the curses of mankind, shall make life hateful to him - till at last his own hand end him".85

Accounts, Criminals, and Sensational Reading Matter

A similar sensational case was that of „Renwick Williams, commonly called The Monster", tried for assaulting and wounding a Miss Ann Porter at the Old Bailey in July 1790. There is a framed frontispiece depicting the "Monster" in court, again in profile: Williams standing upright in court in front of a window, the lower parts of his body hidden behind the spiked dock and there are some papers and an inkstand. The trial account was taken in shorthand by L. Williams, Esq., printed for D. Brewman in London, and cost one shilling.88 A similar frontispiece with the accused in the court room behind a spiked dock and in front of a window, can be found in The Northern Impostor; Being a faithful Narrative of the Adventures, and Deceptions, of James George Semple, commonly called Major Semple [...], printed in 1786.89 Semple who is depicted as a modish gallant on the frontispiece and is called "a genius who has excited as much curiosity as his depredations have caused alarm" (p. 117), was sentenced to transportation for seven years, and he was cautioned by the Recorder "against imagining that the genteel accomplishments which he possessed were any mitigation of the offence" (p. 120).

Since the middle of the century one could buy ever more comprehensive collections of criminal biographies, like The Bloody Register [...] (1764), John Villette's The Annals of Newgate, or the Malefactor's Register (1776; fig. 13), as well as collections often edited an annotated from a legal point of view by barristers of the Inner Temple such as James Mountague (The Old Bailey chronicle [...]; 1783/84), William Jackson (The New and Complete Newgate Calendar [...], 1795, enlarged edition 1818), Andrew Knapp and William Baldwin (The Newgate Calendar [...], 1824-1826), and Camden Pelham (The Chronicles of Crime; or, the New Newgate Calendar, 1841; a later edition 1886).106

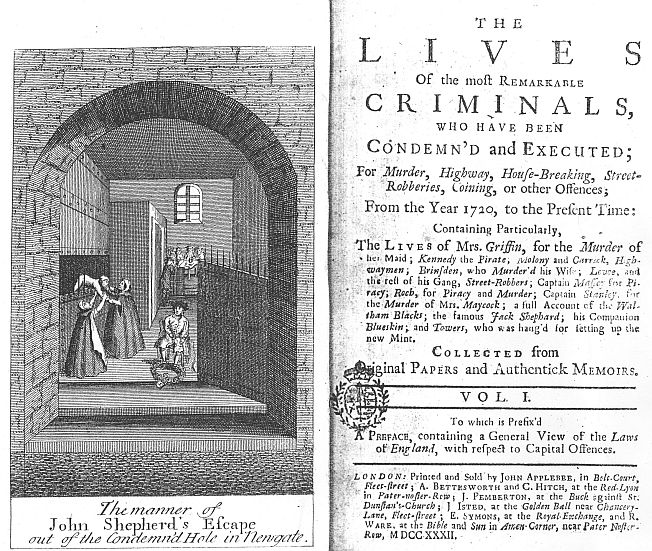

Already Applebee's The Lives of the most Remarkable Criminals (1732; fig. 15) aims at the well-to-do and reasonably educated reader. The title-page says in so many words that the accounts are "Collected from Original Papers and Authentic Memoirs", and the first volume has a "Preface, containing a General View of the Laws of England, with respect to Capital Offences". The frontispiece offers a view of the inside of Newgate prison: while in the background there are some gentlemen sitting around a table; in the front we see a heavily manacled prisoner, while another one slips through the prison bars with the help of two women. The prison door is open; the illustration shows "The manner of John Shepherd's Escape out of the Condemn'd Hole in Newgate". To take a later example, John Villette's The Annals of Newgate; or, The Malefactors Register (1776), is, according to the title-page "Calculated To expose the Deformity of Vice, the Infamy and Punishments naturally attending those who deviate from the Paths of Virtue; and intended as a Beacon to warn the rising Generation against Temptations, the Allurements, and the Dangers of bad Company". Some part of these Annals are "extracted from authentic Records", while "the Histories and Transactions of the modern Convicts" have been "communicated by the unhappy Sufferers themselves". There is an epigraph from Pope's Essay on Man, warning the reader: "Vice is a Monster of such frightful Mien, / As, to be hated, needs not to be seen".111 The frontispiece of Villette's second volume depicts "His Majesty George the Third: Personating Justice & Mercy [see the scales and the writ of pardon in his hands]; Which Virtues he has happily united, as will appear in the Course of this Work".

The almost identical title-pages of these four volumes emphasise the entertaining and morally uplifting nature of the accounts ("interesting memoirs", "occasional anecdotes and observations"). The black latter fonts used for the phrase „The Laws of England" emphasise the time-honoured nature of law. Smaller framed illustrations on the title-pages show a view of Newgate (I), of Surrey Gaol, Horsemonger Lane (II), of the Penitentiary, Milbank (III), and of The Tower of London (IV).

The addition of title-pages to printed books, different from the usage during the manuscript area, has been "one of the most distinct, visible advances from script to print".1 It was developed not so much to display the printer's skill than as a marketing tool. Thus it is considered to be "ot a direct response to the technological change that printing embodies, but to the economics implicit in the technology".2

Researchers have, however, not always been unanimous about the meaning of the terms title-page and frontispiece. Although 'title-page' was sometimes used as an umbrella term for the beginnings of a book,3 it is by now common practice to consider the frontispiece, or to use H.D.L. Vervliet's term frontispiece orné,4 a separate entity; separate from the title-page that is a book's opening, and separate in turn from the table of contents and the text itself.5 The frontispiece usually faces the title-page; but both may contain woodcuts, engravings, and other kinds of illustratioons.

The title-page with its more or less abbreviated identification of the book's content developed out of a blank page used for protective reasons, helping in addition to identify a given pile of sheets.6 Modest label-titles, announcing the contents of the book in an abbreviated form, soon were used for promotional and advertising aims. They were decorated by woodcuts that, however, often had nothing to do with the text itself,7 but gave, besides the contents, details about author, printer, publisher and/or bookseller and the price of the book.8 Because of the absence of front covers or jackets as we have them nowadays, the title-page and the frontispiece were of utmost economic importance for the bookseller, giving the customer the opportunity to gauge the merits of a book.

The important next step in the development was the invention of the emblematic title-page ornamented with allusive and learned images, emblems or visual symbols as "a second language".9 From an aesthetic point of view one might distinguish between four types of designs, either dividing the title-page into geometrical compartments, showing a single overall design, a cartouche design animated by characters from the classical world, or using an architectural device like the 'Triumphant Arch' on the title-page of Michael Drayton's Poly-olbion, or a chorographical Description of Great Britain (1612-1622).10 These architectural title-pages in the form of a monument celebrate the fame of the author or honour the subject.11 Behind this design might be the intimate relationship between building and writing as expressed in "An Epigram explaining the Frontispiece of this Worke" in John Guillim's A Displaye of Heraldrie (1610).12

Emblems, symbols and other allegorical devices were considered to suggest some hidden meaning, asking the learned reader to work this out by himself.13 As early as 1565 Hadrianus Junius remarked in his Emblemata that emblems in general "keep the reader's mind in suspense and surmise, [...] draw him to admiration with an increase of delight, especially when they conceal in a pleasant obscurity, as if beneath a veil, something of solid excellence under apt and subtle inventions".14 It is true that emblematic title-pages served as a means "to communicate complex ideas by means of visual images";15 but the ultimate end of including elaborate designs must have been an economic one.16 As printing was and is an industrial process that requires a considerable amount of capital and the coordination of several producing and distributing craftsmen, the frontispiece added symbolic value to a book on the market, however restricted the readership might have been. In some cases, as that of the early French works of Pierre Gringore, economic reasons dictated the layout of the books' openings. As has been shown by Cynthia J. Brown, the early title-pages do not mention the author, as in the case of translations into English: it were the printers Richard Pynson and Wynkyn de Worde who would profit from a publication.17 This changed, however, as Gringore, with a certain rise in prestige, began to wield control over the publication of his works.

Authorial presence on the title-page is, on the other hand, a fact in the case of well-known learned and humanistic authors whose portraits were, in addition, displayed on the title-pages. As Corbett and Lightbown remark, authors 'publishing' their own books during the Middle Ages, i.e. during the times of manuscript publication, had themselves frequently been portrayed on the presentation copies of their manuscript,18 one famous example being John Lydgate presenting the book of The Pilgrimage of the Life of Man to the Earl of Salisbury.19 Such presentation pictures have usually been regarded as constituting the act of final and definite publication.20 In later periods the authors' portraits are sometimes following the engraved title-page, but more often than not portraits are included on the title-page itself, usually in the form of an oval miniature, together with the engravers' names ("fecit" or "sculpsit"). Nevertheless, title-pages and frontispieces are not only means by which "great authors" used to translate "their intellectual and literary concepts into the forms of pictorial art, exercising their imagination in another sphere".21 They are without doubt an elaborate means to convince the prospective buyer to purchase the book, thus serving as rhetorical and persuasive means in the process of book distribution. This is emphasised by Anette Frese's analysis of Barocke Titelgraphik. Illustrations on sixteenth and seventeenth century German title-pages and frontispieces had two functions: to tell the reader that the book in questions was meant to convey learning and wisdom, and that it was a commercial item to be sold.22 Frese therefore illustrates the process of distribution and the ways and means of presenting and selling books in the respective Cologne or Frankfort bookshops.23 Here analysis thus emphasises the fact that, in Cynthia J. Brown's words, the title-page from the beginning "came to symbolise the capitalistic nature of printing. It ultimately served as a promotional tool for advertising and a number of people stood to profit from such publicity".24

The Early English Book Markets

English printing and bookselling was, as on the continent, a commercial enterprise, and from Caxton onward those who sold books on the marketplace had to explore its potential.25 As the extent of literacy was severely restricted, book buyers during the sixteenth century predominantly came from the ranks of the nobility, the gentry and the upper tradesmen, later on there were also wealthier farmers and the members of the merchant class as book buyers, an indication of a gradual evolvement of a print-dependent society. Nevertheless, printing, in view of the limited market and a population that as a rule did not spend its money for non-essentials, remained an expensive commodity.

Books or pamphlets for a more general reading public as a rule had no hard protective covering, but were unbound26 and thus could be sold at a lower price. As the elite abstained from writing for the printing press, the needy professionals had to rely on the market, thus they were from the beginning dismissed as an "vncountable rabble of ryming Ballet makers and compylers of senceless sonets, who be most busy to stuffe euery stall full of grosse deuises and vnlearned pamphlets".27

George Thomason's collection of c. 23,000 newsbooks and pamphlet published during the 1640s and 1650s is an indication not only of the vast amount of political propaganda during the Civil War but also of the evolving market and the usefulness of printed material, at least in the eyes of those who argued for the freedom of the printing press, like John Milton (see his Areopagitica), or the Levellers who demanded a complete freedom of the press.28 With the return of the Stuarts, however, licensing and censorship were again important weapons to silence the political opposition, reinforcing most of the provisos of the 1637 Star Chamber Decree. The first victim in Roger L'Estrange's campaign against the radical press was the printer John Twyn who, after a trial in February 1664, was hanged, disembowelled, and dismembered.29 L'Estrange later warned others that they would suffer "like brother Twyn". In response to pressures like these, the Quakers developed the idea of an 'official' underground press to get their unlicensed writings into print. As printers omitted imprint details for fear of prosecution, we do not know much about the actual printing and publishing processes of the underground presses.

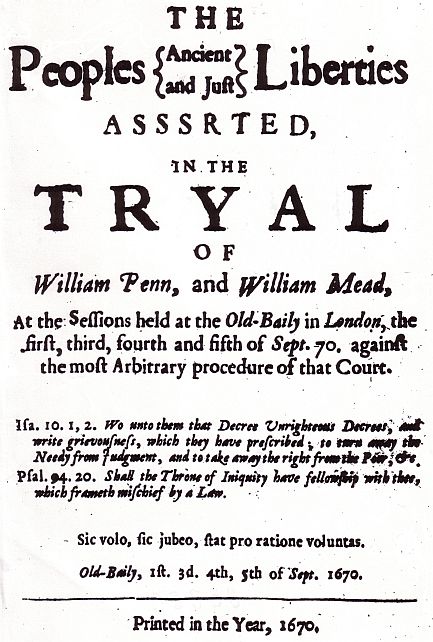

Title-page of the unofficial and unlicensed trial account of

William Penn and William Mead (1670)

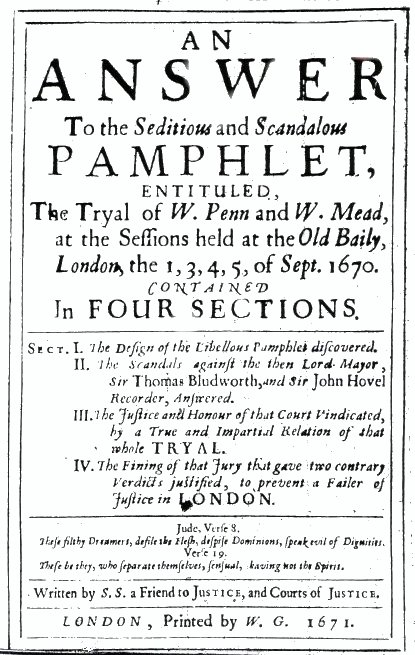

Frontispiece of the answer to

the Trial Account of Penn and Mead (1671)

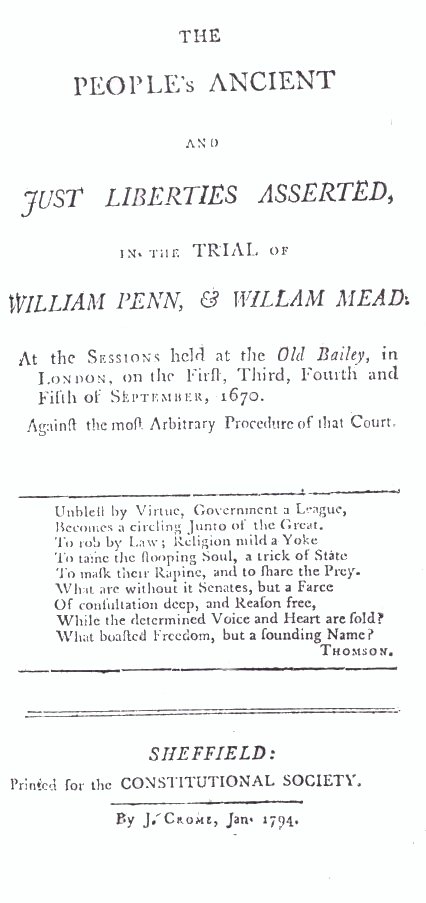

Frontispiece of the 1794 Reprint of

the Trial Account of Penn and Mead

Books published for a reading public, eager to be entertained, were another matter. As J. Paul Hunter has pointed out, journalism and the publication of various kinds of obviously inexpensive "true accounts" during the seventeenth century reflect accelerated secularism and a growing interest in private and personal topics.30 One of the known interests was that in those forms of abnormal and criminal behaviour that seemed to threaten the public peace. Relevant publications included, as Hunter remarks, "accounts of robberies, household quarrels, discoveries of witchcraft, fires, and all sorts of out-of-the ordinary events occurring to ordinary people in ordinary circumstances".31 Books like the 1677 collection entitled A true relation of all the bloody murders that have been committed in and about the citie and suburbs of London, since the 4th of this instant June were written and published in order to be "a Monument [...] with this kind of Inscription, Look upon me, and learn to fear God [...] There are Pillars of Salt set up every where for our remembrance".32 Thus moral education and entertainment went together.

The new crime publications coming from the printing presses, already well before the lapse of the licensing act in 1695, belonged to a variety of formats and genres. One of these was the conversion narrative that described the spiritual transformation of the condemned prisoners.33 Others were the execution accounts prepared by the Ordinary of Newgate Prison, the trial reports giving transcripts of courtroom proceedings, newspaper reports and crime broadsheets, all of these developing into the so-called Newgate Calendars to be analysed later on.

Early Title-Pages and Illustrations of Crime Writings

As we can see from Joseph H. Marshburn's and Alan R. Velie's edition of "pamphlets and ballads of crime and sin", as early as 1591 the title-page of collections of "strange and inhuman murders" was embellished with a woodcut. The title (in Roman, different sizes, except for "printed in London" which is in black letter) reads: "Sundrye strange and inhumaine Murthers, / lately committed. / The first of a Father that hired a man to kill three of his children neere / To Ashford in Kent: / The second of master Page of Plymoth, murdered by the consent of his / owne wife: with the strange discouerie of sundrie other murthers. / Wherein is described the odiousnesse of murther, with the vengeance which God infli- / cteth on murtherers."34

The title-page gives a sensational summary of the book itself, and has, in addition, a framed woodcut showing a man with an axe raised above his head, surrounded by four corpses of those already murdered, one of them approached by a dog. On the left there is a man in black, hands and feet like bird's claws, his right hand outstretched towards the murderer, obviously representing death. One of the criminal cases narrated was that of the murder of Master Page of Plymouth, perpetrated by his wife's lover who had been strangling him and breaking his neck against the bedstead, one of the main sources of Thomas Dekker and Ben Johnson's tragedy, Page of Plymouth, that was performed by the Admiral's Men in 1599, but now lost.35 The case was well-known and thus worthy of being shown on the title-page of a book that was not written for the select audience of learned and well-educated readers but for a larger English reading public. Authors and printers were well aware of the fact that they did not publish for purposes of aesthetic delight but for economic reasons.36

Another case of an embellished title-page of 1624 reads as follows: "The crying Murther: / Contayning the cruell and most horrible Butcher / of Mr. TRAT, Curate of olde Cleaue; who was first murther / as he trauailed vpon the high way, then was brought home to his house [?] / and there was quartered and imboweld: his quarters and bowels being / [af]terwards perboyld and salted vp, in a most strange and fearfull manner. For this fact / the Iudgement of my Lord chief Baron TANFIELD, the young Peter Smethwicke, A / [n]drew Baker, Cyrill Austen, and Alice Walker were executed this last Summer / Assizes, the 24. of Iuly, at Stone Gallowes, neere Taunton / In Summerset-shire".37

The framed woodcut underneath shows a grim looking bearded man in front of a tub, a knife in his left hand, half a leg in his right hand; in front of him, seen in profile, there is a woman, obviously Alice Walker; and another man on the right, a bigger knife in his right hand, a human head in the other; and in front of him another human being who is disembowelling a carcass: the right leg has already been severed from the trunk of his body. This is a rather coarse, but highly sensational woodcut that certainly was able to attract buyers looking for sensation: "AT LONDON: / Printed by Edw: Allde for Nathaniell Butter. / 1624". The murder had been perpetrated in Taunton in Somerset on June 24, 1623, but the trial was deferred by Chief Baron Tanfield until the last summer assizes of 1624. Although the narrator gives the reader the circumstantial evidence as well as the words of the accused protesting their innocence, he is clearly on the side of the court that later on found the accused guilty of murder. They were hanged as "obstinate and unrepenting sinners", protesting their innocence to the last, and there seem to have been various people who did not believe in their guilt. Thus the murder and the trial had enough publicity that helped to sell the "attractive" book.

About thirty years later James Hind came to be one of the illustrious highwaymen and rogues of the Commonwealth period. Hind had remained loyal to Charles I and, after having served in the royalist army, was imprisoned at the beginning of the fifties. A great number of pamphlets38 narrate Hind's almost legendary "merry pranks, witty jests, unparalleled attempts, and strange designs".39 Judging from the pamphlet with the title We have brought our hogs to a fair market, Hind seems to have committed his crimes well aware of their political implications, bidding his compatriots "to keep your hands from picking and stealing, and to be in charity with all men, except the caterpillars of the times, viz., long-gownmen, committeemen, excisement, sequestrators, and other sacrilegious persons. I do likewise strictly order and command, that you keep your hands from shedding of innocent blood; that you relieve the poor, help the needy, clothe the naked, and in so doing you will eternize your fame to all ages: and the cutting trade renowned".40 The title-page of this pamphlet provokingly promises to describe "the appearing of a strange Vision on Munday morning last, with a Crown upon his head; the Speech and Command that were then given to Cap. Hind; and the manner how it vanished away".41 The vision, as we learn, will be that of the late King Charles, saying "Repent, repent, and the King of Kings will have mercy on a Thief".42 In the centre of the page we see the cut of the King, "a Crown upon his head".43

The simple title-page of A Pill to purge Melancholy: Or, Merry Newes from Newgate [...] does not only give a sensational summery of Hind's pranks, but also tries to capture the reader with the journalistic promise that they will find a "variety of other delightfull Passages, never heretofore published by any Pen".44 Even before being arrested on 9 November 1651, people in London had been able to buy G.F.'s Hind's Ramble, or, the Description of His Manner and Course of Life, presumably published on 27 October 1651.45 And they could read about his arrest in the Weekly Intelligencer of the Commonwealth for Tuesday, 11 November that same year.46

As Hind was a well-known highwayman, immediately after his apprehension a pamphlet was published under the following long and wordy title: "The true and perfect / RELATION / Of the taking of Captain / JAMES HIND: / ON / Sabbath-Day last in the Evening at a Bar- / bers house in the Strand neer Clements / CHURCH: / With / The manner how he was discovered and ap- / prehended: His examination before the Councel / of State; And his Confession touching the / King of Scots. / ALSO / An Order from the Councel of State con- / cerning the said Captain Hind; The bringing of / him down to Newgate (yesterday) in a Coach; / And his Declaration and Speech deliv- / vered in prison."

As the syllabification indicates, this pamphlet was printed in a great hurry and the pressure of time obviously did not allow the printers to give the text on the title page a symmetrical shape. The reason for this might have been, as in the case of The crying Murther, the use of a very simple decorative border. Borders surrounding text-pages or title-pages were usually produced as separate cuts; they were costly and therefore re-used several times so that the dimensions of the internal space must have been a problem to the printers in the case of long and wordy titles.47 The True and Perfect Relation was obviously printed as a sensational pamphlet directly on the occasion of Hind's apprehension, and it obviously had to compete with a great number of rival prints devoting themselves to the Hind „myth". Thus it is understandable that printers tried to catch the eyes of their book buyers.48

The Trial of Captain Hind on Friday Last before the Honorable Court at the Sessions in the Old Bailey, printed by George Horton, who had already published An Excellent Comedy, Called, The Prince of Priggs Revels, a fourteen pages long series of dramatic sketches, is a different case.49 The word "TRIAL" on this title page is given in Roman square capitals and in an eye-catching display in larger type, more than thrice the height as those used for "Captain James Hind on Friday last before [...]". There follows a kind of summary in relatively small letters, and at the end, in square brackets: "Published for general satisfaction, by him who des- / cribes himself", and the "author's" name: JAMES HIND. The summary part seems to have been done in a very simple way, the printer being hampered by the limited space because of the illustration underneath. This depicts the court room in the Old Bailey, with the judges and the scribes in the centre of the background, several others, obviously the twelve (actually there are only eleven) jurymen on the right-hand side, and others on the left-hand side. In the centre of this title-page illustration we see James Hind in chains ("These are filthy gingling spurs"),50 upright and not facing the court but the reader. This wood cut illustration must have been done in a hurry, considering the fact that the trial on 12 December was doubtless of great interest to Londoners, although it was known that it would be adjourned to the city of Oxford and tried again by a Council of War in August the next year. In fact the title woodcut is the same as had already been used for a 1643 newsbook A Perfect Divrnall of the Passages in Parliament.51

Hind was sent to court in Reading and subsequently convicted of murder. But as the sentence was nullified he was removed to Worcester where, after being convicted of treason against the State, he was drawn, hanged, and quartered on 24 September 1652. Hind, the dismembered body of whom was hung over the various gates of the city, his head being taken down and buried after seven days,52 like Strodtman in 1701, and Mary Edmonsdon in 1759, "dropped like stones into the public consciousness", according to Lincoln B. Faller.53 This dropping like a stone into the consciousness was more or less a commercial affair as it was the result of the speedy printing presses pouring out fictions and legends. At least Hind himself is said to have remarked in one of these pamphlets, after a gentleman had pulled "two Books out of his pocket; the one entitled, Hinds Ramble[,] the other Hinds Exploits", that he had already seen them: "[...] upon the word of a Christian, they were fictions".54

Title-Page and Frontispiece of Merry Newes from Newgate

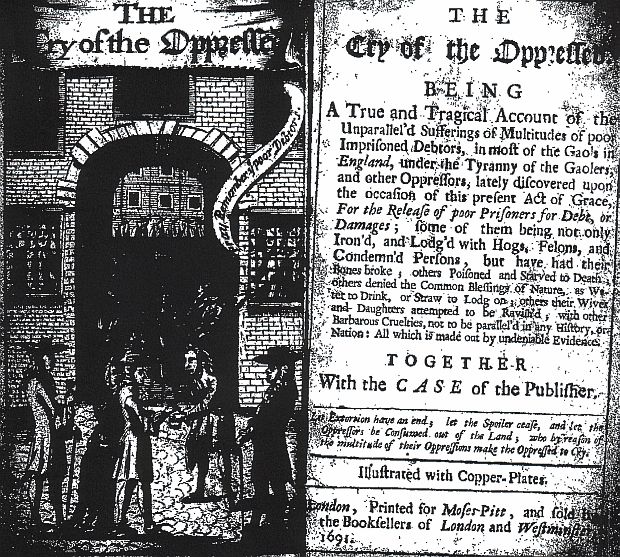

The place name Newgate seems to have been of some promotional value; this is indicated by the use of Newgate in subtitles such as: A Pill to purge Melancholy: Or, Merry Newes from Newgate or We have brought our hogs to a fair market or Strange News from Newgate. A book describing the situation in debtors' prisons was published a few years after the Glorious Revolution, the bookseller Moses Pitt's The Cry of the Oppressed (1691). This book giving a rather dreary account of the situation in debtors' prisons is illustrated with a number of copper plates. The frontispiece of The Cry of the Oppressed (fig. 1) depicts the entrance of a prison; there are some people in front of the building, some of them in manacles, others are looking out of barred windows, and there is a banner saying: "Pray remember poor debtors".

Frontispiece of The Cry of the Oppressed, printed for Moses Pitt, 1691

The title appears at the top of the frontispiece as well as of the title-page, the words "Cry of the Oppressed" printed in black letter; whereas the article "THE" and the present perfect "BEING" are capitalised and in "white" letters.55 The rest after „being" is one long sentence: everything except the first line is slightly indented, but after the tenth line the type-face gets smaller, obviously in order to accommodate the material to the page. The printer's had obviously miscalculated the layout but did not want to reset the title-page. The text reads as follows:

A True and Tragical Account of the / Unparrallel'd Sufferings of Multitudes of poor / Imprisoned Debtors, in most of the Gaols in / England, under the Tyranny of the Gaolers, / and other Oppressors, lately discovered upon / the occasion of this present Act of Grace, / For the Release of poor Prisoners for Debt, or / Damages; some of them being not only / Iron'd, and Lodg'd with Hogs, Felons, and / Condemn'd Persons, but have had their / Bones broke; others Poisoned and Starved to Death, / others denied the Common Blessings of Nature, as Wa- / ter to Drink, or Straw to Lodg on; other their Wives / and Daughters attempted to be Ravishe'd, with other /Barbarous Cruelties, not to be parallel'd in any History, or / Nation: All which is made out by undeniable Evidence. / TOGETHER / With the Case of the Publisher. Let Extortion have an end; let the Spoiler cease, and let the / Oppressors be Consumed out of the Land; who by reason of / the multitude of their Oppression make the Opressed to Cry.

Individual Trial Accounts and Biographies

With the expansion of the urban and provincial leisure market during the eighteenth century,58 ever more readers were eager to get hold of shorter separate trial accounts and portraits of criminals as well as of more voluminous collections such as James Caulfield's Remarkable Persons.59 As the Gentleman's Magazine remarked in 1794: "Science [i.e. learning in general] now seldom makes her appearance without the expensive foppery of gilding, lettering, and unnecessary engravings [...]".60 It is true that engravings or etchings tended to be plagiarised and used in one publication after the other, thus being evidence of the process of stereotyping.61 But whereas during the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries prints portraying more respectable sitters usually follow idealised patterns and portraits of the accused were at first glance indistinguishable from formal portraits,62 there is a new development from the middle of the eighteenth century onward. Although there are a number of frontispieces emphasising, out of commercial reasons, the sensational nature of crime, some authors/publishers were nevertheless aiming at greater veracity and authenticity and thus at respectability. The narrative technique of circumstantial realism as found in Daniel Defoe goes together with an stronger emphasis on probability and certainty in general,63 with a more scientific approach towards portraiture, based on the anatomy of the human body,64 and in matters of judicial fact finding, with an elaboration of the law of circumstantial evidence.65

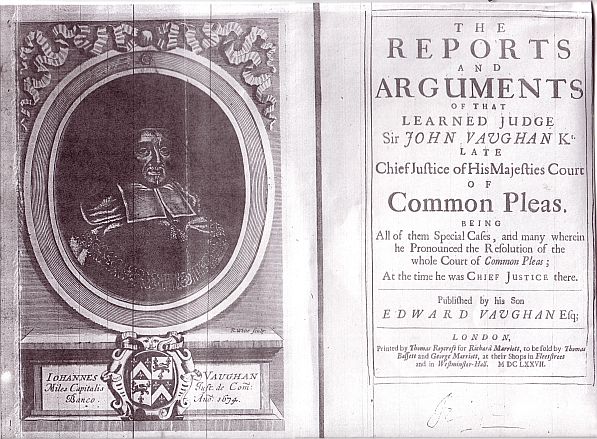

In order to assess the frontispieces of some of the trial accounts from a historical point of view, it is necessary to show the similarities with other juridical publications. One example is The Reports and Arguments of that Learned Judge Sir John Vaughan Kt. Late Chief Justice of His Majesties Court of Common Pleas (1677; fig. 2). Vaughan had been responsible for establishing the principle of non-coercion of jurors in his decision on Bushel's case, and in the course of his career he had been knighted.66 There is a frontispiece with an oval medallion of the engraved and idealised portrait, like, e.g., the frontispiece of Gilbert Burnet's Some Passages of the Life and Death Of the Right Honourable John Earl of Rochester (1680).67 Above Vaughan's portrait there is a convoluted, spiral shaped scroll,68 and it is placed on a plinth below; on its front we see Vaughan's coat of arms, and on the right and the left side his name in Latin.69 Those who bought this book must have been educated gentlemen.70

Frontispiece and title-page of John Vaughan's The Reports and Arguments (1677)

Portrait of Simon Lord Lovat (after William Hogarth);

frontispiece of The Whole Proceedings

Several of the separate trial accounts published during the eighteenth and at the beginning of the nineteenth centuries are embellished in a similar way, some of them with portraits in oval medallions or framed rectangulars. On 30 June, 1797, G. Thomson published The Whole Trial and Defence of Richard Parker [...] (fig. 4).75 Parker, "the president of the Committee of Delegates for the redress if Grievances on Board the Sandwich at the Nore", was tried before a court martial on board the Neptune and sentenced to be hung from the yardarm of a battleship. The account was taken in "Short-Hand", underlining its authenticity, as does Parker's portrait: he is looking into the far distance, aware of what is awaiting him.7676 The trial of Parker is also included in The Genuine Lives, Trials, and Execution of James Macklay, and Martin Clinch (1797).77 Whereas the price of the first publication was six-pence, this one, embellished with an engraving showing Parker's execution on the yardarm, cost nine-pence.

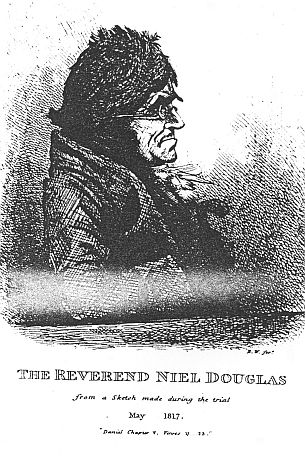

Another case is the frontispiece of The Trial of Tho. Radcliffe Crawley (1802) who was indicted for the Murder of two women in Dublin. The accused is shown in half profile, looking dejectedly to the ground. His head is tilted down but his eyes appear to be looking forward, sullenly meeting his fate. Again there is an authenticating remark on the title-page.78 In April 1806 Edward Jefferey printed, "by the Express Apointment of the Sheriff", The Trial of Richard Patch, for the Wilful Murder of Mr. Isaac Blight.79 The half-portrait of the accused who, too, is not looking at the observer, was taken, according to the information on the bottom of the frontispiece (fig. 5), "[f]rom an original Drawing taken in Court during the Trial", and the account itself reproduced by two short-hand writers. The title-page wets the reader's appetite in addition by announcing two further "Portraits of Richard Patch and Esther Kitchener, Taken in court, expressly for the Publication".80 There is also a framed portrait on the frontispiece of Trial of Mary Ann Tocker (1818) who was accused of a libel on the Vice-Warden of the Stannary-Court, Devon. The text on the title-page says that the defence is given "verbatim as delivered by the defendant"; the same is said of her „address to the Jury".81 The printer of this account, like those of the aforementioned publications, used about eight different types of letters (Baskerville: capital, non-capital, italics, bold-face, and open). Marry Anne Tocker's portrait is of a rectangular shape, lightly framed, and the woman is again looking into the far distance; she is quite handsome, with black hair and in a fashionable dress, sitting on a chair, obviously somewhere outside her house. The Rev. Niel Douglas whose trial for sedition took place before the High court of Justiciary in Edinburgh, May 1817, is shown in profile.82 From the frontispiece (fig. 6) we learn that the portrait was reproduced "from a sketch made during the trial", and the title-page names the shorthand writer.83 The reverend, accused of sedition, looks like an embittered intellectual, his lower lip protruding over the upper lip.

Niel Douglas:

The trial of the Rev. Neil Douglas [...] (1817)

Richard Patch:

The trial for Richard Patch, for the wilful murder [...] (1806)

John Thurtell:

The fatal effects of gambling exemplified in the murder of Wm. Weare [...] (1824)

Viscount Melville:

The trial by impeachment, of Henry Lord Viscount Melville [...] (1806)

The variety of fonts used for the first title-page of

The Fatal Effects of Gambling exemplified in the murder of William Weare [...]) (1824)

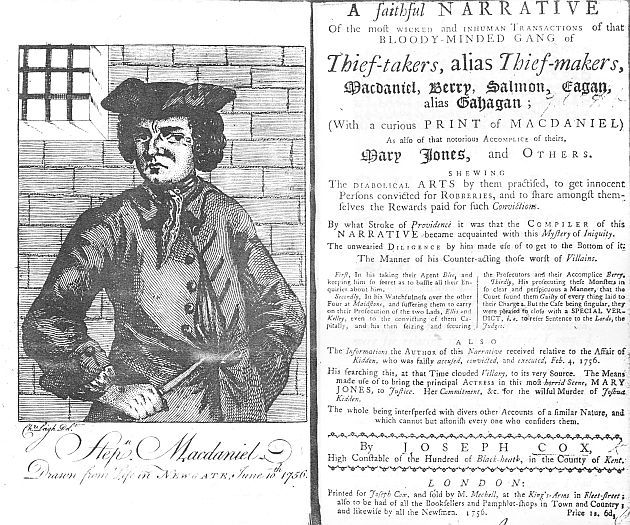

Apart from these quite simple portraits there are others frontispiece illustrations that either depict the interior view of a prison or a courtroom, or of the crime itself. This is a result of the growing market for prints and portraits of notorious criminals. Portraits are often said to be drawn "from Life". Thus A faithful NARRATIVE / of the most WICKED and INHUMAN TRANSACTIONS of that Bloody Minded Gang of Thief-takers, alias Thief-makers, Macdaniel, Berry, Salmon, Eagan, alias Gahagan; (With a curious Print of Macdaniel), by the High Constable Joseph Cox, depicts the grim looking prisoner in his cell with his dagger in his right hand: "Drawn from Life in Newgate, June 10th 1756".86 The title-page of this 1756 pamphlet (fig. 9) is composed of forty lines, some of them set in double columns, and telling the reader that he will read about "The DIABOLICAL ARTS by [the thief-takers] practised, to get innocent Persons convicted for ROBBERIES and to share amongst themselves the Rewards paid for such Convictions". There are more remarks indicating the sensational and entertaining nature of the material collected by the "Compiler of this Narrative": "The whole being interspersed with divers other Accounts of a similar Nature, and which cannot but astonish every one who considers them".87

Portrait of Stephen Macdaniel: frontispiece of A Faithful Narrative […] by Joseph Cox (1756).

There are two more trial accounts with similar frontispieces to be mentioned here. The first one is An Account of the Trial of Thomas Muir, one of those accused for "seditious practices" as members of Reform societies before the High Court of Justiciary in Edinburgh in 1793. In spite of Sheridan's intervention in the House of Commons, Muir was sentenced to fourteen years transportation to Botany Bay. Thomas Muir, "Esq. Younger, of Huntersville", is discovered standing upright in the court room, obviously addressing the bar, with some papers in his outstretched right hand, his left hand resting on his bosom.90 The epigraph on the title-page is from Tacitus' Agricola, the hero of which had subdued the whole of the British isle with the exception of the Scottish highlands: "Dedimus profecto grande patientiae documentum; et sicut vetus aetas vidit, quid ultimum in libertate esset; ita nos quid in servitute, adempto per inquisitiones et loquendi audiendique commercio".91 The meaning of this quotation – the contrast between the liberty of the past and the present as a period of servitude – is clear sign of the political struggles during the years immediately after the French Revolution and the repercussions of Edmund Burke's French Revolution. The use of Latin is an indication of an educated readership, as is the quotation from James Thomson's "Liberty" (1735) on the title-page of The Peoples Ancient and Just Liberties asserted, in the Tryal of William Penn, and William Mead (1670; fig. 10), reissued under William Penn's name by the Sheffield Constitutional Society in 1794,92 or the Bible quotation from Mat. xxvi. 60 on the title-page of The Trial of Lord George Gordon for High Treason (1781).93

The Account of the Trial of William Brodie, and George Smith (1788) is comparable to the Muir account. Brodie and Smith had been accused of breaking into, and robbing, the general excise office of Scotland. Brodie is shown on the frontispiece in his prison cell, a gentleman with his left hand resting on his heart. Nevertheless, the reader is warned with a quotation from Alexander Pope's Imitations of Horace: "Read this and tremble! Ye who 'scape the laws".94 This account, too, seems to address the educated reader. The same is true of the Narrative of the Murder of the Late Rev. J. Waterhouse (1827). The title-page promises "A view of the Rectory House & Church" (the frontispiece), and the „Ground Plan of the Premises, and a Portrait of Slade".95 The quotation on the title-page is adapted from Shakespeare's A Winter's Tale: "You have undone a man of fourscore years, / That thought to fill his grave in quiet. And now / The hangman must put on thy shroud, and lay thee / Where no priest shovels in the dust. – / Peace to his soul, if God's pleasure be! / Forbear to judge, for we are sinners all".96

There are some frontispieces of a very different and more obviously sensational nature. In the case of the patricide Charles Drew (1740),97 we see the son shooting his father who is standing, a candle in his right hand, thunderstruck on his doorstep. From the title-page of The Trial of Isaac Prescott, Esq. [...] for Wanton, Tyrannical, unprovoked, and savage Cruelty, towards Jane Prescott, his Wife (1781) the reader learns that it "appears, by this Trial, that Captain Prescott is so very ingenious in the art of tormenting, and has contrived so many new and extraordinary modes of punishment for a woman, that he appears fully qualified to preside at a Spanish inquisition". In the next sentence the author refers the reader back to the still well known sadism of Mrs. Brownrigg, "but our hero has refined upon her cruelties; and [...] has invented a system of his own".98 The frontispiece depicts two scenes of violence, the first one in a garden, a lady approached by her lustful husband, the other one on board a ship, the captain obviously inviting a common seaman to rape his wife whose skirt has already been invitingly lifted up. The dramatic frontispiece of The Whole Trial of the Incendiaries before the Recorder of London (price one shilling; 1790; fig. 11) explains: "Jobbins & Flindall, setting Fire to the hayloft, at the Red Lyon, Aldersgate Street". The two criminals are shown descending from the hayloft after having started the fire.99

Trial accounts of those accused of criminal conversation are of a similar spectacular nature. The title-page of The Trial of Captain Elwin (1807?) claims to include "the intercepted letters" and announces the "Damages" to be "Two Thousand Pounds!!!". This account is "embellished with a plate", the engraving showing Capt. Elwin and Lady Brograve entwined in front of a tent, while the unsuspecting husband is obviously looking through a telescope at the sea from a high cliff nearby. There is a similar eye-catching announcement on the title-page of the same printers The Trial of Thomas Sheridan, Esq. (1807?): "Damages Fifteen-Hundred Pounds!!! / Embellished with the shooting-scene". The engraved frontispiece (fig. 12) depicts an obviously dramatic scene on the staircase: Sheridan is escaping from an old hag who has a sort of weapon (or a candlestick?) in her left hand, while the lightly-clad wife of Peter Cambell is watching the scene through the half-opened door of her bedroom, another witness looking down from behind the railings of the stairs. Both accounts were published by J. Day in London in 1807, and the price was one shilling.

Collections of Criminal Biographies, Trials and Executions.

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries single trial accounts, criminal biographies, last dying words etc. were published in more expensive collections, today known under the title of Newgate Calendar. The term had originally been used for a document compiled by the keeper of Newgate, the list of those admitted to the gaol during the previous four weeks. From 1684 onward, the Ordinary (chaplain) of Newgate began publishing the Ordinary's Account after each hanging day in London. As this was a mercenary venture, ordinaries like the Rev. Samuel Smith, Dr. John Allen or Paul Lorrain were attacked for taking money from the prisoners and for publishing „an incoherent Magazine of Trash and Scandal".100 Besides that, there were collections of criminal biographies like A Complete History of the Lives and Robberies of the Most Notorious Highwaymen [...] (1719),101 Charles Johnson's A General History of the Robberies & Murders of the Most Notorious Pirates (1724),102 Capt. Alexander Smith's Memoirs of the Life and Times of the Famous Jonathan Wilde [...] (1726)103 or the Lives of the Most Remarkable Criminals [...] (1735).104 Apart from that there are collections of more or less authentic, though abridged trial accounts like the Compleat Collection Of Remarkable Tryals [...] at the Sessions-House in the Old Baily [...] (1718),105 or Select Trials for Murders, Robberies, Rapes, Sodomy, Coining, and other Offences [...] (1734/35, 1742, 1744 and 1764).

Frontispiece and title-page of The Proceedings (1730)

When discussing the popularity and the readership of these collections, the authors' and publishers' general aims should be kept in mind. Whereas for Smith, Johnson or the publisher Applebee11107 the aspect of entertaining reading seems to have been paramount, the barristers' collections had more educational and moral aims. Be that as it may, these publications proved to be popular and influential, counting William Godwin, William Thackeray or Charles Dickens amongst their readers. According to Rayner Heppenstall, the Newgate Calendar was for the most part "literature of a rather poor kind, fit only to inspire literature in others".108 But as Stephen Knight remarks correctly, The Newgate Calendar was published for a more educated and wealthy readership, it was seasoned with stern moral warnings and offering the stories for the educational guidance of parents.109 We should keep in mind that book prices in England were quite high, except for pirated editions, around the turn of the eighteenth century.110 No wonder that differences between the title-pages of learned books and of Select Trials or Newgate Calendars are but slight. The graphic layout of Patrick Colquhoun's A Treatise on the Police of the Metropolis (1796; fig. 14) is not really different from William Jackson's New and Complete Newgate Calendar (1795).

Title-page of Patrick Colquhoun's A Treatise on the Police of the Metropolis (1797)

The six volumes of William Jackson's The New and Complete Newgate Calendar (the 1795 and 1818 editions are almost identical) display a wordy title-page, using all the available fonts, and the authenticity is again emphasised by phrases like "containing new and authentic accounts", "comprehending all the most material Passages in the Sessions Papers", "containing the most faithful narratives ever yet published", "properly arrainged from the Records of the Courts". On the other hand, the moral and education aims are underlined by means of some verses: "How dreadful the fate of the Wretches who fall / A Victim of Laws they have broke! / Of Vice, the beginning is frequently small, / But how fatal at length is the Stroke! / The Contents of these Volumes will amply display / The steps which Offenders have trod: / Learn hence, then, each Reader, the Laws to obey / Of your Country, your King, and your God". The title-page of the whole 1795 edition shows an engraving of Newgate from the outside. The frontispieces of the other volumes are illustrated by „elegant copper plates", depicting a „View of Hounslow Heath, with the Gibet and Men hanging in Chains" (1795, II); "The Recorder making the Report of the capital Convicts to His Majesty in Council" (1795, III); "View of the Public Office Bow Street with Sir John Fielding presiding & a Prisoner under examination" (1795, IV); "The New Sessions-House in the Old Bailey" as well as „The New Goal of Newgate" (1795, IV); "View of the New-Prison, Clerkenwell" and "Representation of Tothfields-Bridewell Westminster" (1795, VI). The 1818 frontispieces are even more finely wrought, showing amongst others "An Exact Representation of the Manner of Executing Criminals, on the New Scaffold and Gallows opposite the New Gaol of Newgate in the Old Bailey" – "Accurately Engraved for the New Newgate Calendar which (being the only Complete Work of this Kind) is published by Alex. Hogg at the King's Arms No. 16 Paternoster Row" (1818, I); "The House of Correction, Cold Bath Fields. The View taken near Grays Inn Road" (1818, III); "A Man Publickly whipped in the Sessions House Yard in the Old Bailey" (1818, V); "The Surrey County Gaol in Horse Monger Lane, near Stones end, Southwark and the new manner of Executing Criminals thereon" (1818, VI, part I). Except for the last two frontispieces (and some others mentioned above) that could have inspired readers of the horror of corporeal punishment and death by hanging, all the other illustrations depict the outsides of prisons and bridewells.

The frontispieces of Andrew Knapp and William Baldwin's The Newgate Calendar are reproductions of already published prints: portraits of Sarah Malcolm (1824, I; fig. 16), Elizabeth Brownrigg (1825, II), Renwick Williams (1825, III), and Henry Fauntleroy, Esq. (1826, IV).

Andrew Knapp and William Baldwin, The Newgate Calendar (1824).

Frontspiece with the portrait of Sarah Malcolm after William Hogarth.

It is true that, due to a rise in literacy and the efforts of societies like that "for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge" or "for Promoting Christian Knowledge", during the eighteen thirties and eighteen forties reading became more widespread. Many critics complained about the distribution of what the Statistical Society of London called "novels of the lowest character, being chiefly imitations of Fashionable novels, containing no good, although probably nothing decidedly bad". Whereas this category made up for 46%, they found only 0,45% of books "decidedly bad", besides 3,92% "Miscellaneous Old Books, Newgate Calendar, &c."112 Readers that were unable to afford the more expensive books bought cheap criminal biographies of the popular romance type.113 Thus Camden Pelham's Chronicles of Crime still see as their aim "the maintenance of virtue and good order", although "the general aspect of the state of crime in this country is now [seen as] infinitely less alarming than formerly".114 No wonder that the publishers thought it would be most promising if they would use an altogether different type of frontispiece, that is, using original drawings by Charles Dickens's illustrator Phiz. Although all the illustrations included in the two volumes depict, sometimes in a very melodramatic way, a crime that is the subject of one of the accounts, the frontispiece and the illustration on the title-page of volume seem to indicate an altogether humorous subject matter. On the frontispiece we see a man in ragged clothes who does not succeed to get the "good bed" advertised on the door; and in addition, the text underneath this and the illustration on the title-page are misleading. The title-page shows the fat mayor of Bristol escaping, with the help of some servants, across a wall. The frontispiece of volume II shows a "Trial by Battle"; it resembles in a way the coloured frontispiece of Gilbert Abbott A'Beckett's Comic Blackstone (1887): there is a succession of the representatives of the various influences on British Law, beginning with "Julius Caesar – Roman Law", up to a fat Lady holding up a guide with the inscription „Victoria Comic Blackstone".115

2 See Margaret M. Smith, The Title-page: Its Early Development 1460-1510 (London & New Castle, DE: The British Library & Oak Knoll Press, 2000), p. 12; see on Smith's study, Uwe Böker, "Commercialisation and the Renaissance Title-page". In: IASLonline [15.11.2004] URL: http://iasl.uni-muenchen.de/rezensio/liste/Boeker0712346872_1159.html.

03 Smith, Title-page, p. 13.

04 H.D.L. Vervliet, "Les origines du frontispiece architectural", Gutenberg-Jahrbuch (1958), pp. 222-31.

5 Smith, Title-page, pp. 14-5. Smith follows here R.B. McKerrow who remarked that "a title-page [is] a separate page setting forth in a conspicuous manner the title of the book which follows it, and not containing any part of the book itself". R.B. McKerrow, An Introduction to Bibliography for Literary Students (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1927), p.88.

6 Smith, Title-page, pp. 21-2.

7 Ibid., p. 75, and n. 1.

8 Ibid., pp. 91ff.

9 Margery Corbett & Ronald Lightbown, The Comely Frontispiece: The Emblematic Title-Page in England 1550-1660 (London, Henley and Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1979), p. 1.

10 Ibid., p. 3. See chap. 13 on Drayton, see the illustration on p. 152.

11 Ibid., pp. 8-9.

12 Quot. ibid., p. 9. "The noble Pindare doth compare somewhere, / Writing with Building, and instructs vs there, / That euery great and goodly Edifice, / Doth aske to haue a comely Frontispiece".

13 Ibid., p. 18.

14 Quot. ibid.

15 Ibid., p. 34.

16 See Annette Frese, Barocke Titelgraphik am Beispiel der Verlagsstadt Köln (1570-1700): Funktion, Sujet, Typologie (Köln & Wien: Böhlau, 1989), p. 9. Frese, p. 54, speaks about the tendency to include enigmatic title-pages that were meant to induce the readers to buy such books. See also the quotation from the German poet Georg Friedrich Harsdörffer, p. 62.

17 Cynthia J. Brown, "The Interaction between Author and Printer: Title Pages and Colophons of Early French Imprints", Soundings, 33 (1992), No. 29, pp. 33-53, here p. 38.

18 Corbett & Lightbown, The Comely Frontispage, p. 43. For medieval presentation copies see Uwe Böker, "The Epistle Mendicant in Mediaeval and Renaissance Literature: The Sociology and Poetics of a Genre", in The Living Middle Ages: Studies in Mediaeval Literature and Its Tradition. A Festschrift for Karl Heinz Göller, ed. Uwe Böker, Manfred Markus & Rainer Schöwerling (Stuttgart & Regensburg: Belser, 1989), pp. 137-186.

19 Cf. Derek Pearsall, John Lydgate (London: Routledge, 1970), illustrations between pp. 166 & 167, cf. pp. 173 & 69-70.

20 Cf. Robert K. Root, "Publication before Printing", PMLA, 28 (1913), pp. 417-431.

21 Corbett & Lightbown, The Comely Frontispage, p. 47.

22 Frese, Barocke Titelgraphik, p. 9.

23 Ibid., pp. 11-2.

24 Brown, "The Interaction between Author and Printer", p. 33.

25 See John Feather, A History of British Publishing (London & New York: Routledge, 1988), p. 19ff.

26 Blood and Knavery: A Collection of English Renaissance Pamphlets and Ballads of Crime and Sin, ed. by Joseph H. Marshburn & Alan R. Velie (Rutherford: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1973), pp. 13-4.

27 William Webbe (1586), as quot. in Marshburn, p. 15. As to the situation a century later, see Uwe Böker, "'The distressed writer': Sozialhistorische Bedingungen eines berufsspezifischen Stereotyps in der Literatur und Kritik des frühen 18. Jahrhunderts", in Erstarrtes Denken: Studien zu Klischee, Stereotyp und Vorurteil in der englischsprachigen Literatur, ed. by Günther Blaicher (Tübingen: Niemeyer, 1986), pp. 140-53.

28 Feather, History of Printing, pp. 44-8.

29 See Uwe Böker, "Institutionalised Rules of Discourse and the Court Room as a Site of the Public Sphere", in: Sites of Discourse - Public and Private Spheres - Legal Culture, ed. by Uwe Böker & Julie Hibbard (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2002), pp. 35-66.

30 J. Paul Hunter, Before Novels. The Cultural Contexts of Eighteenth Century English Fiction (New York & London: Norton, 1990), pp. 180-1.

31 Ibid., p. 181.

32 Quot. ibid., p. 184.

33 Cf. Daniel A. Cohen, Pillars of Salt, Monuments of Grace. New England Crime Literature and the Origins of American Popular Culture, 1674-1860 (New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press 1993), p. 13.

34 The title-page (including the woodcut) is reproduced in facsimile as the title page of Marshburn & Velie's publication.

35 See Marshburn & Velie, Blood and Knavery, p. 58.

36 Whereas the title-page is in Roman letters, the text itself, except for the titles of the two chapters, are in black letter. For the change from black letter to Roman letter and the cultural significance of typography throughout the seventeenth century, see E.P. Goldschmidt, The Printed Book of the Renaissance: Three Lectures on Type, Illustration, Ornament (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1950), p. 25 (2nd ed. Amsterdam: van Heusden, 1966); and Charles C. Mish, "Black Letter as a Social Discriminant in the Seventeenth Century", PMLA, 68 (1953), pp. 627-30.

37 Marshburn & Velie, Blood and Knavery, p. 14 (facsimile).

38 Ibid., pp. 103-4. Cf. Lincoln B. Faller, "The Myth of Captain James Hind: A Type of Primitive Fiction before Defoe", New York Public Library Bulletin 79 (1975/1976), pp. 139-66, and his Turned to Account: The Forms and Functions of Criminal Biography in late Seventeenth- and early Eighteenth-century England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987).

39 This is a quotation from We have brought our hogs to a fair market or Strange News from Newgate, repr. Marshburn & Velie, Blood and Knavery, p. 104-5.

40 Ibid., p. 106. For similar remarks see the quotations in Faller, Turned to Account, p. 10-1.

41 Quot. ibid., p. 14.

42 Ibid.

43 According to Faller, the cut is about two and a half inches high; see ibid., p. 10.

44 Marshburn & Velie, Blood and Knavery, p. 113.

45 Faller, Turned to Account, p. 216, n. 5. According to Faller, 'G.F.' may be identified as George Fidge; the date of publication has been entered in hand on the title page of the copy in the British Library. G.F. was also the author of The English Gusman; or the History Of that Unparallel'd Thief James Hind. There is a facsimile of this title-page in Marshburn & Velie, Blood and Knavery, p. 137, as well as of No Jest like a trite Jest: Being a Compendious Record of the Merry Life and mad exploits of Capt. James Hind, published after Hind's execution on 24 September 1652. See Marshburn & Velie, p. 140.

46 Faller, Turned to Account, pp. 7-8.

47 Smith, Title-page, p. 126.

48 For the other Hind-pamphlets published in 1651 and 1652, see Faller's bibliography in Turned to Account, pp. 291-3.

49 See the facsimile of the title-page in Marshburn & Velie, Blood and Knavery, p. 132. On the Excellent Comedy, see Faller, Turned to Account, p. 9.

50 These are Hind's words, see Marshburn & Velie, Blood and Knavery, p. 133.

51 See the facsimile reproduction in P.M. Handover, Printing in London From 1476 to Modern Times (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1960), p. 115. The illustration is on the upper half, the text of the news on the lower part of the page.

52 Faller, Turned to Account, p. 7.

53 Ibid., p. 2.

54 Quot. ibid., p. 10.

55 For the significance of black letter printing, see fn. 36 above. As Steinberg, Five Hundred Years of Printing, p. 168, remarks, the English government had "championed the black-letter 'Bishops' Bible of 1568; England was to be the last European nation to admit Roman type as the standard for vernacular printing" (for the 1584 frontispiece of this Bible, see Handover, Printing in London, p. 79; cf. the frontispiece of the 1645 Holy Bible). When Robert Barker, the King's Printer, issued the Authorized Version, it was both in Roman and black-letter editions. For the use of black letter printing in legal history, see J.H. Baker, The Common Law Tradition: Lawyers, Books and the Law (London: Hambledon Press, 2000), pp. 208-9. Although by the first half of the seventeenth-century black-letter type had gone out of fashion (Steinberg, p. 176), it was still being used to print fiction of the second romance type harking back to medieval times, as well as certain types of ballads. Later on, black letter was used for mock purposes. See Handover, pp. 149-50; Blackletter: Type and National Identity, ed. by Peter Bain & Paul Shaw (New York: The Herb Lubalin Study Center of Design and Typography, 1998).

56 See Randall McGowen, "The Well-Ordered Prison: England, 1780-1865", in The Oxford History of the Prison: The Practice of Punishment in Western Society, ed. by Norval Morris & David J. Rothman (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), pp. 71-99, see esp. pp. 72ff.; Uwe Böker, "The Prison and the Penitentiary as Sites of Public Counter-Discourse", in: Böker & Hibbard, pp. 211-48.

57 Cf. Daniel Defoe, A Tour through the Whole Island of Great Britain. Abr. and ed. with intro. and notes by Pat Rogers (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971). For the following quotations from Defoe, Smith and others, cf. Uwe Böker, "The Prison and the Penitentiary as Sites of Public Counter-Discourse", in Böker & Hibbard, pp. 211ff.

58 See John Feather, The Provincial Book Trade in Eighteenth-Century England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), pp. 32ff.

59 See Sheila O'Connell, The Popular Print in England 1550-1850 (London: The British Museum Press, 1999), p. 198ff. O'Connell refers to James Caulfield, Portraits, memoirs, and characters of remarkable persons from the reign of Edward the Third, to the Revolution. Collected from the mostauthentic accounts extant (London: pinted for J. Caulfield & Isaac Herbert, 1794/1795; repr. London: Hurst 1821). For a similar market for reproductions of prints in France, see Jean Adhémar, Europäische Graphik im 18. Jahrhundert (Köln: Edition Berend von Nottbeck, n.d.), p. 128ff.

60 Gentleman's Magazine, 64 (1794), 47, as quoted in Richard D. Altick, The English Common Reader: A Social History of the Mass Reading Public, 1800-1900 (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1963), p. 52.

61 See e.g. Hogarth's frontispiece 'Head of Samuel Butler', which is actually a copy of John White's mezzotint of the portrait of the painter Jean-Baptiste Monnoyer; see Joseph Burke & Colin Caldwell, Hogarth: the Complete Engravings (Secaucus, NJ: The Wellfleet Press, n.d.), no. 79.

62 See O'Connell, The Popular Print, p. 94.

63 See Barbara J. Shapiro, Probability and Certainty in Seventeenth-Century England: A Study of the Relationships between Natural Science, Religion, History, Law, and Literature (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1983).

64 Thomas Kirchner, L'expression des passions: Ausdruck als Darstellungsproblem in der französischen Kunst und Kunsttheorie des 17. und 18. Jahrhunderts (Mainz: von Zabern, 1991), esp. chap. x and pp. 316-8.

65 Alexander Welsh, Strong Representations: Narrative and Circumstantial Evidence in England (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992).

66 See Böker, "Institutionalised Rules of Discourse".

67 See the fascimile of the frontispiece and the title-page in Graham Greene, Lord Rochester's Monkey: Being the Life of John Wilmot, Second Earl of Rochester (London: Bodley Head, 1974), p. 209.

68 The ornament resembles that on one of the portraits of Titus Oates, as reproduced in Greene, ibid., p. 169.

69 This resembles Hogarth's 'Jacobus Gibbs / Architectus. 1747'. See Burke & Caldwell, Hogarth, no. 215.

70 Vaughan was appointed chief justice of the Common Pleas in May 1668, and knighted. See Edward Foss, A Biographical Dictionary of the Judges of England: From the Conquest to the Present Time 1066-1870(London: Murray, 1870), pp. 686-7. Vaughan who died in 1674 was buried in the Temple Church where there is a marble to his memory.

71 (London: Thomas Basset 1681). As the page in front of the title-page announces, the printer, Thomas Basset, was authorised by Francis North, Lord Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas, to print this trial account. For the political context of the Colledge trial, see Harold Weber, Paper Bullets: Print and Kingship under Charles II (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1996), chap. 5.

72 (London: Samuel Billingsley, 1747). As we learn from the page in front of the title-page, Billingsgate is appointed in pursuance of an order of the House of Peers, to print the whole proceedings. For Lord Lovat who was beheaded on 9 April 1747, see The Complete Newgate Calendar [...], collated and edited with some appendices by J.L. Rayner & G.T. Crook, 5 vols (London: Privately printed for the Navarre Society, 1926), III, p. 137; cf. also Knapp & Baldwin's new version of The Newgate Calendar (London: J. Robins, 1824, vol. I); 1825 (vol. II); 1825 (vol. III); 1826 (vol. IV), I, p. 492 (ill. "Lord Lovat beheaded on Tower Hill"); see also "Lord Lovat", after William Hogarth, National Library of Scotland, Blaikie Collection, an adaptation of Hogarth's familiar portrait. See Richard Sharp, The Engraved Record of the Jacobite Movement (Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1996), p. 33 and 174. For Hogarth's Lovat, see Burke & Caldwell, Hogarth, no. 102.

73 Berthold Hinz & Hartmut Krug, William Hogarth 1697-1764. Erste Auflage als Katalog einer Ausstellung der Neuen Gesellschaft für Bildende Kunst in der Staatlichen Kunsthalle Berlin 1980 (Gießen: Anabas, 21986.

74 For cheap illustrated broadsides, see The Whole Execution and Behaviour of Simon Lord Lovat, as reproduced in O'Connell, The Popular Print, pp. 92-3. Whereas the text itself describes the collapse of one of the viewing stands near the scaffold, the illustration is taken from a seventeenth-century woodblock, originally made for the execution of Charles I.

75 (London: G. Thompson 1797).

76 His case is narrated in Raynor & Crook, Newgate, IV, p. 128, and in Knapp & Baldwin, Newgate, III, p. 264 (ill. 'The Execution of Parker'; as well as in William Jackson, The New and Complete Newgate Calendar; or, villany displayed in all its branches, etc. New edition, with great additions, illustrated with [...] copper plates (London: Alexander Hogg, 1818), VI, p. 497 ('interesting detail of his execution').

77 (London: Robert Turner, 1797).

78 (Dublin: A. Sleater [1802?]). The case was tried in March 1802.

79 (London: Edward Jeffery, 1806). For a different account, see Fairburn's edition of the trial of Richard Patch [...] (London: John Fairburn, 1806).

80 For more information on the Patch case who was hung on top of the New Prison, Borough of Southwark, 8 April 1806, at which accommodation was provided for the Royal Family, see Knapp & Baldwin, Newgate, III, p. 410; Raynor & Crook, Newgate, IV, p. 307.

81 (London: Henry White, sen., 1818).

82 (Edinburgh: John Robertson, 1817).

83 (Edinburgh: Printed for John Robertson, sold in Edinburgh and London, 1817).

84 (London: J. Nichols and son, 1824). For this case, see Knapp & Baldwin, Newgate, IV, pp. 353-73. For the publicity of this case, see Henry Jones, Account of the Murder of the Late Mr. William Weare (London, 1824); The Fatal Effects of Gambling Exemplified in the Murder of Wm. Weare (London, 1824); Pierce Egan, Trial of John Thurtell and Joseph Hunt (London, 1824); Recollections of John Thurtell (London, 1824); Trial of Thurtell and Hunt, ed. by Eric R. Watson (Edinburgh: Hodge 1920). See also Robert Altick, Victorian Studies in Scarlet (London: Dent, 1972), between pp. 160 & 161; for the Thurtell play The Gamblers; or, The Murderers at the desolate Cottage, see ibid., p. 90.

85 The epigraph does not seem to be from Edward Moore's The Gamester, 1753. I have, however, been unable so far to get hold of a copy of either James Shirley's The Gamester (1633/1637) or Susannah Centlivre's play of the same title (1705).

86 He has a dagger in his right hand: did he get it from the engraver for the purposes of making the sketch?

87 The price of this pamphlet was 1s.6d. For MacDaniel and the other accused, see Raynor & Crook, Newgate, III, p. 237, and Knapp & Baldwin, Newgate, II, p. 212.- A Faithful Narrative Of the most wicked and inhuman Transactions of that Bloody-Minded Gang of Thief-takers, alias Thief-makers, Macdaniel, Berry, Salmon, Egan, alias Gahagan; (with a curious Print of MacDaniel) As also of that notorious Accomplice of theirs, Mary Jones, and Others, shewing The Diabolical Acts by them practiced, to get innocent Persons convicted for Robberies, and to share amongst themselves the Rewards paid for such Conviction. By what Stroke of Providence it was that the Compiler of this Narrative became acquainted with this Mystery of Iniquity [...]. By Joseph Cox, High Constable of the Hundred of Black-heath, in the County of Kent (London: Printed for Joseph Cox [...], 1756).

88 (London: D. Brewman, [1790]). See also Raynor & Crook, Newgate, IV, p. 180; Knapp & Baldwin, Newgate, III, p. 161. See also W. Dent's "The Monster" (BMC 7730, ?12 July 1790), in J.A. Sharpe, Crime and the Law in English Satirical Prints, 1600-1832 (Cambridge: Chadwyck-Healey, 1986), p. 184.

89 (London: G. Kearsley, 1786).

90 (Edinburgh: J. Robertson, 1793). Cf. Knapp & Baldwin, Newgate, III, p. 202.- See the illustration "Transport for Sedition", in Hugh Anderson, Farewell to Judges & Juries: The Broadside Ballad & Convict Transportation to Australia, 1788-1868 (Hotham Hill, Victoria/Australia: Red Rooster Press, 2000), p. 308.

91 The epigraph is from Tacitus' De vita Agricolae. See Cornelii Taciti De Vita Agricolae, ed. by H. Furneaux, 2nd rev. ed. by J.G.C. Anderson (Oxford: Clarendon Press 1922), p. 4.

92 The Society for Constitutional Information did not have local branches, but other Constitutional Societies, founded and conducted independently, corresponded with London.

93 There is a remark on the title-page saying that this account was "published under the Inspection of his Lordship's Friends", and that they have added "several original papers relating to the subject". The account was printed by J. Mennons in Edinburgh, "Price only Sixpence".

94 (Edinburgh: William Creech, 1788). See Alexander Pope, "The First Satire of the Second Book of Horace. Satire I. To Mr. Fortescue', line 118. The Poetical Works of Alexander Pope, ed. by Adolphus William Ward (London: Macmillan, 1961), p. 289 (the original text reads: ''Hear this, and tremble! you, who 'scape the Laws".

95 (Huntingdon: T. Lovell, 1827). See the "Narrative" unpaginated after the table of contents; the portrait of Joshua Slade, "drawn from life", is on p. 46.

96 Shakepeare, The Winter's Tale, Act IV, Sc. Iv, reads: "Shepherd I cannot speak, nor think / Nor dare to know that which I know. O sir! / You have undone a man of fourscore three, / That thought to fill his grave in quiet, yea, /To die upon the bed my father died, / To lie close by his honest bones: but now / Some hangman must put on my shroud and lay me / Where no priest shovels in dust. O cursed wretch, / That knew'st this was the prince, / and wouldst adventure / To mingle faith with him! Undone! undone! / If I might die within this hour, I have lived / To die when I desire". It is not clear if the text came from a bowdlerised version of the play or if it was changed by the author or the printer.

97 The Suffolk parricide; being the trial, life, transactions, and last dying words, of Charles Drew [...] (London: Standen, 1740). Cf. Knapp & Baldwin, Newgate, I, p. 421, and the engraving 'Charles Drew shooting his Father', from The Suffolk Parricide (1740); the scene takes place outside the father's house, there is an eye-witness to be seen; cf. Faller, Turned to Account, p. 58.

98 For Mrs. Brownrigg, hung for torturing and murdering her female apprentices at Tyburn, 14 Sept. 1767, see: Raynor & Crook, Newgate, IV, p. 46 (see the illustration 'Elizabeth Brownrigg', facing p. 47); Knapp & Baldwin, Newgate, II, p. 369 (with 'Elizabeth Brownrigg. Executed for Cruelty and Murder', II, frontispiece; 'Elizabeth Brownrigg cruelly flogging her Apprentice, Mary Clifford', p. 369).- Only the formula "Entered at Stationers Hall" on the Prescott title-page is in black letter.

99 The Whole Trial of the Incendiaries, before the Recorder of London [...] (London: M'Clean, 1790?). Cf. Raynor & Crook, IV, p. 178.

100 See Drunks, Whores and Idle Apprentices: Criminal Biographies of the Eighteenth Century, ed. and intr. by Philip Rawlings (London: Routledge, 1992), p. 5. Cf. The Newgate Calendar, intro. by Clive Emsley (Ware: Wordsworth Classics, 1997); Eighteenth-Century Popular Culture: A Selection, ed. by John Mullan & Christopher Reid (Oxford: University Press, 2000): there are extracts from Thomas Purney, The Ordinary of Newgate his Account, of the Behaviour Confession and Last Dying Speeches of the Four Malefactors that Was Executed at Tyburn on Monday May the 24th 1725; and from J. Guthrie, The Ordinary of Newgate his Account, of the Behaviour, Confession, and dying Words of the Malefactors, Who Were executed at Tyburn, on Monday the 11th of this Instant November, 1728; see also Lucy Moore, The Thieves' Opera: The Remarkable Lives and Deaths of Jonathan Wild, Thief Taker, and Jack Sheppard, House Breaker (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1998); Lucy Moore, Con Men and Cutpurses: Scenes from the Hogarthian Underworld (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2001).

101 A Complete History of the Lives and Robberies of the Most Notorious Highwaymen, Footpads, Shoplifts, & Cheats of both Sexes. Wherein their most Secret and Barbarous Murders, Unparalleled Robberies, Notorious Thefts, and Unheard of Cheats are set in a true Light and exposed to Public view, for the Common Benefit of Mankind, ed. by Arthur L. Hayward (London: Routledge 1926; = repr. from the 5th ed., published in three 12mo volumes, in 1719).

102 Charles Johnsons, A General History of the Robberies & Murders of the Most Notorious Pirates. (1724). With an introduction and commentary by David Cordingly (London: Conway, 2002); see Uwe Böker, "Das Geschäft mit der Kriminalität. Publikationen über die Londoner Unterwelt", in IASL-online (24.10. 2002), http://iasl.uni-muenchen.de/rezensio/liste/boeker.htm (24.10. 2002).

103 Capt. Alexander Smith, Memoirs of the Life and Times of the Famous Jonathan Wilde [...]. Facs. ed. with a new intro. by Malcolm J. Bosse (New York: Garland Publishing, 1973).

104 See the modern edition: Lives of the Most Remarkable Criminals [...], ed. by Arthur L. Hayward (London: Routledge, 1927).

105 Compleat Collection Of Remarkable Tryals Of the Most Notorious Malefactors at the Sessions-House in the Old Baily, for near Fifty Years past, vol. 1 (London: Printed for J. Phillips; and Sold by J. Brotherton and W. Meadows at the Black-Bull in Cornhill, and J. Roberts in Warwick-lane, 1718).

106 The 1795 Jackson title-page is richly ornamented, using a variety of fonts: script, classical antiqua (modern face), upper case, italics and others.

107 For John Applebee (c. 1689-1750), see Karl T. Winkler, Handwerk und Markt: Druckerhandwerk, Vertriebswesen und Tagesschrifttum in London, 1695-1750 (Stuttgart: Steiner, 1993), pp. 261ff.; and Michael Harris, "Trials and Criminal Biographies: A Case Study in Distribution", in: Sale and Distribution of Books from 1700, ed. by Robin Myers & Michael Harris (Oxford: Polytechnic Press, 1982), pp. 1-36.

108 Rayner Heppenstall, Reflections on The Newgate Calendar (London: Allen 1975), p. x.

109 Stephen Knight, Form and Ideology in Crime Fiction (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1980). See a 1779 'moral frontispiece' reproduced in The Newgate Calendar, ed. and sel. by Sir Norman Birkett (London: The Folio Society, 1951), plate preceding p. 16.

110 See Altick, The English Common Reader, pp. 51ff., on the relations between book prices and commodity prices.

111 Essay on Man, II, 217f.; The Poetical Works, p. 206.

112 [Edgell Wyatt Edgell], "Third Report of a Committee of the Statistical Society of London appointed to enquire into the State of Education of Westminster", Journal of the Statistical Society of London, 1 (1838), pp. 447-492, here p. 485.

113 See Louis James, Fiction for the Working Man 1830-50: A Study of the Literature Produced for the Working Classes in Early Victorian Urban England (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1973), pp.170ff.

114 Camden Pelham, The Chronicles of Crime: Or, the new Newgate Calendar [...] (London: Miles, 1886), I, pp. v and viii.

115 G.A. A'Beckett, The Comic Blackstone, rev. and ext. by Arthur Wm. A'Beckett, with ten full-page coloured illustrations and others by Harry Furniss (1887, repr. Southampton: Ashford 1985).