Introduction

1 Retrospective reflections

2 Current considerations

2.2 Objectives

2.3 Description of course organization

2.4 Part I business English studies

2.5 Part II business English studies

2.6 Content-based language teaching and ESP

2.7 Some issues raised by content-based second language instruction

3 Prospective proposals

3.1 Curriculum development

3.2 What economics or business teaching is about: assumptions

3.3 Academic monitoring programme and research

3.4 Implications for teachers and their expected

qualifications

3.5 Implications for examinations

Conclusion

Introduction

The title of my paper suggests a tripartite temporal perspective: past, present and future. In the first part I shall limit my remarks on where we have come from to briefly summarizing developments in ESP-teaching and how business English (BE) is situated within the paradigm. In the course of this we shall see how closely the academic demands for English are tied up with professional requirements for English for business purposes. At the same time the utility of maintaining the distinction will be justified.

In the second part I shall describe some current syllabus / curriculum developments rather selectively, concentrating on the work of the department of English at the Vienna University of Economics and Business Administration. I shall make no claims to generalizability, since as will become clear, a major argument will be that creative, evolutionary adaptations to the demands of individual niches, settings and institutions are what drive both research and teaching in this field. Finally, in the third part, I shall broach some proposals for where English for business purposes might now proceed against the backdrop of the first two sections.

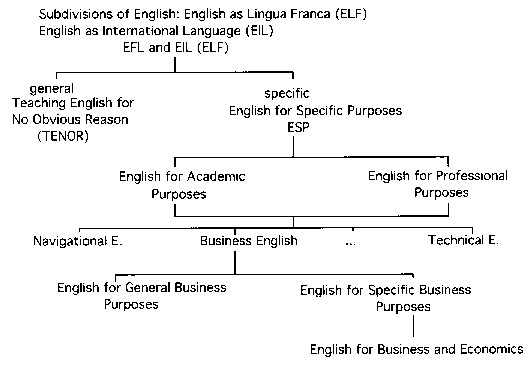

As a starting point perhaps I should make a few subdivisions in English. Figure 1 can serve to indicate what we are dealing with. As you can see, I begin with EIL (English as International Language) or ELF (that is, English as Lingua Franca). I prefer this term to EFL for a number of reasons. Then follows the well-known split into general or specific: Teaching English for No Obvious Reason (TENOR) or English for Specific Purposes (ESP). Following the ESP filter, we come to the well-worn distinction into EAP (English for Academic Purposes) or EOP (English for Occupational Purposes). Then we can select whichever specific purpose we find English is used for. Once we get down to Business English (from ELF) I find myself in good company with Maggie Jo St John (1996) who subdivides the umbrella term which is Business English further. It subsumes English for General Business Purposes (EGBP) and English for Specific Business Purposes (ESBP). This appears to be a working analytical distinction we can accept for the time being. Under the latter heading the term English for Business and Economics (in German this is "Wirtschaftsenglisch") is a specific perspective (adopted at the Vienna University of Economics and Business Administration). This can be shown to have an EAP or an EOP focus. I shall refer to this in more detail shortly.

To get some idea of how things have changed in ESP-circles consider the (1993) overview of Christine Johnson's under the section 'Describing Business English'. She lists things like: 1 Focus on specialist lexis, 2 Focus on gambits, 3 The case study approach, 4 Focus on business skills. Now, while all these focuses may be very relevant for their respective audiences and levels, there is an approach to teaching business English I find lacking, and which only gets mentioned en passant, in this otherwise quite admirable overview of business English. I am referring to EFL with a business or economics bias (BE), linked to content-based instruction or English-medium business studies instruction going on in tertiary education. Perhaps this goes beyond orthodox business English. This may mean that the defining process of business English is not sophisticated enough; I am not sure. At any rate it appears as if the scope of business English may have been narrower for Johnson than for me. Alternatively, and this may be the result of a narrow professional myopia coming from the Anglo-Saxon homeland perspective, for Maggie St John also ignores this area of expansion, it is logical that British-based commentators are unfamiliar with it. But as business English teaching expands in higher education, I would argue that this will become more important.

I have myself written about this sector in European tertiary education in Alexander (1988). I identified two main purposes for which students required English: academic purposes (to complete their course of study) and occupational purposes (each was to have a six-month placement in a work environment). This meant that the students I was then teaching needed 'the full gamut of skills' to enable them to cope, but primarily, oral skills and the receptive skill of reading.

I do not wish to be misunderstood. Clearly there is much going on under the heading of business English that fits into what I called the 'orthodox' heading, and as co-author with Leo Jones of New International Business English, I would be the last to ignore this area. But as we know from the field of ESP in general the needs of learners are devastatingly disparate and varied.

In the 1970s I acted as ESP consultant to academics in biology, electrical engineering and information science who wanted their students to read and discuss in English the relevant technical literature. Coming now to my current professional activities it is clear that both expectations and needs under the umbrella of business English are equally as wide-ranging. Nor is this quite as recent as we might sometimes be led to believe. There has long been a market for English for business purposes, perhaps since 1553, according to Anthony Howatt's history of English teaching. Correspondence and learning to deal with written documents was focused on from the beginning. (Cf. Pickett 1989.) But, as we all know, demands and focuses change over time.

St John (1996) comments aptly that when it comes to business English materials there is increasing demand on the part of teachers and learners for material with more specific content. Perhaps this is related in part to an early construct underlying specific purposes English, namely, that it consisted of general English plus specialized-vocabulary. Certainly, demand for courses emphasizing terminology of specialist areas was widespread in the 70s. Also the requirement that students be enabled to deal with specialist reading materials in their respective disciplines is linked (see Mackay & Mountford, 1978 and Robinson, 1980). I have just referred to the experience I had in one of my many university jobs. This found me advising colleagues and team-teaching with them on computer programming and biology courses in English! Today this emphasis is still to be found in the requests non-ESP specialists make of ESP advisers. And I am sure most of you could relate similar anecdotes in your own professional settings.

Which brings me to current considerations.

As a start to this section consider this quotation:

Thus commences a significant article on how lectures in a second language proceed in Hong Kong. Austria is clearly not Hong Kong, yet many of the comments and the findings reported upon in the article (Flowerdew and Miller 1996 and Flowerdew 1994) can serve to order our thinking on research and teaching practices in a university (such as Vienna University of Economics and Business Administration (WU)) where a large portion of student lectures takes place in English.

2.1 Business English courses at Vienna University of Economics and Business Administration

It is a fact that much academic discourse, many lectures and much teaching now is conducted at the Vienna University of Economics and Business Administration (Wirtschaftsuniversität or WU) in English. Indeed English is a compulsory subject in several courses of study there. English is widely being employed in management training and business administration courses, both for exchange students from other universities and for summer courses, but also when foreign scholars take up visiting professorships at our university and teach our students. Moreover this internationally oriented aspect of the teaching at the WU is set to expand in the coming academic year or two.

It is against the background of both this specific local situation and the general, global expansion of business English in Europe that we can describe the form taken by English courses designed for students of commerce, business administration and economics at one of the largest Universities of Economics and Business Administration in Europe - the WU-Wien.

2.2 Objectives

We can consider the objectives of business English courses at Vienna University of Economics and Business Administration by slipping momentarily into 'marketer-speak'. Let us ask the following question. What is the product of the English department at the Vienna University of Economics and Business Administration? This is the general answer given in a student newspaper, where the work of the department was presented originally in German ("Ziel: die Studierenden zu befähigen, die Fremdsprache im Alltag, Studium und Beruf erfolgreich einzusetzen"). Rendered in English -- The objective is to enable students to employ the foreign language successfully in everyday situations, in their studies and in their professional life or occupations. Clearly, this may appear a tall order: everyday English, English for academic purposes and English for occupational purposes. But a communicative orientation is central, as has been acknowledged in the last ten to fifteen years (cf. Alexander 1983).

2.3 Description of course organization

In keeping with the division into Part I and Part II studies at the university as a whole the department's business English courses are subdivided into two parts.

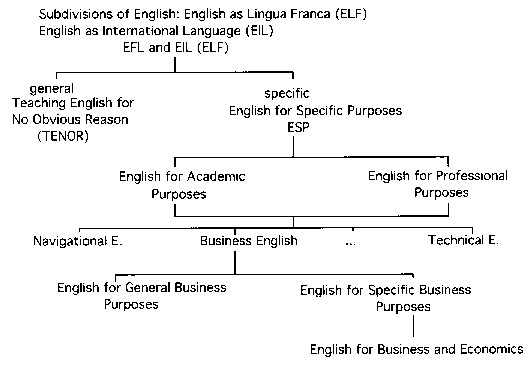

From the point of view of students there is a core set of requirements in Part I with some options and then depending on whether they are pursuing Business Administration or Commerce, in the latter case course requirements in Part II of their studies. These are briefly summarized in Figure 2.

2.4 Part I Business English studies

Part I is subdivided into Proseminar I and Proseminar II which must be done in that order. A brief discussion of the semester outlines will serve to bring out the specific content-based language teaching and communicative orientation of these courses. Topics are the major organizational principle with business communication linked in to this. Proseminar I is organized around 'the business', 'contract of sale', 'marketing' and 'personnel management'. While Proseminar II revolves around the following six business topics: 'business organizations', 'management and organisation', 'financial management', 'stock exchange', 'banking', 'international trade', and 'the economy as a whole'. Clearly grammar and vocabulary are not neglected. But they are dealt with in a functional fashion if and when it is deemed necessary by the lecturers. Likewise, at this level, practice in business communication skills may be facilitated by commercially available textbooks (cf. Alexander 1991 and Jones and Alexander 1996) or customized materials, where appropriate.

2.5 Part II Business English studies

In Part II students are required to take Proseminar III, the successful completion of which is a pre-requisite for enrolment in the seminar in business English. When it comes to the seminars in Part II, there are a number of problems which can arise relating to academic skills expected in the English department.

Firstly, developed reading skills are presupposed for the library research and preparation of the seminar paper which is part of the seminar course requirement. Written academic skills of students may not have been explicitly trained hitherto. In the proseminars the emphasis is on business writing skills, letters, reports and memoranda. Owing to time constraints only limited provision can be made in the Part I modules to deal with the language aspects of students' written work. Rightly or wrongly, it is assumed that they have acquired the skills of writing academic papers in their mother tongue. The transition to the English-speaking side of their studies is assumed to proceed autonomously. Such assumptions are a feature of Austrian university education in general.

As the differences in rhetorical and formal presentation between English-language and German-language academic papers are great, students in our department are provided with a very detailed style sheet on how the formal, presentational side of the paper is to be dealt with. The assistants who support the professor are available to give tutorial guidance on finding a topic and getting started on the personal research and writing of the paper. On the oral side, students are given the opportunity to attend a coaching session in which they are advised by a native speaker, usually an exchange lector in the department, on the oral presentation of their topic prior to the seminar. When it comes to expectations concerning seminar discussions, it has to be said that one encounters wide disparity in performance. While occasional students have been in the United States as school students and are very fluent, others may be unable to contribute in a thoughtful and articulate fashion to the seminar discussions. Hence explicit advice on ways of dealing in English with reasoning and argumentation may well be required.

At this point I would like to make especial reference to the lectures which students are required to attend in our department. In part I students are expected to choose 3 hours (or 7 hours depending on options) of lectures to attend, in part II six hours. The choice of topics is left up to the students to make. Personal preferences concerning areas of future specialization can thus be a guide to choice. Students are expected to discuss topics from their chosen lectures in the Part I and II oral examinations they take.

Let me list some of the subject matter dealt with this term: Accounting (US / UK / A), Business Organizations, the Economies of English-speaking Countries, Private Investment, Marketing, Personnel Management, Money and Banking, International Trade, Risk Management in International Trade, the US Economy, etc. Most of the lecturers have qualifications in business studies or economics in addition to qualifications and longstanding experience in business English teaching. It should be stressed that the English department makes no attempt to duplicate what goes on in other departments in the university. Rather it prefers to see one of its tasks as shadowing business topics or dealing with background material to the English-speaking world and issues of intercultural communication. But it is clear that the language content treated will follow from the material primarily selected as of interest in itself for students of business studies. To summarize: this is an approach which starts with subject matter and builds in language material, such as terminology and proficiency in dealing with relevant texts, where this is deemed necessary.

We can thus characterize the overall orientation of the syllabus as a species of content-based language instruction (cf. Brinton, Snow & Wesche (1989)). Clearly this focus will vary in emphasis from level to level. At the proseminar I and II levels it will perhaps be more general than at the proseminar III or seminar level. And in the lectures it will be more prominent again than in the proseminars. These varied forms of instruction serve to pick up differing needs and requirements. After all, we nominally receive students with matura level (GCSE advanced-level) English knowledge, at least on paper. This tends to be disparate and non-uniform. We cannot presuppose a homogeneous range and level of proficiency in general English. Moreover, despite the evening classes with mature students which some lecturers teach, the fact remains that the vast majority of students are pre-experience students of commerce and business. This means that they have little or no knowledge of the practice of business, nor of the more general business studies and economics which provide the centre of interest of the language work done. Consequently there is much virgin territory in both content and language terms to be entered here.

In a sense this is both the challenge and the opportunity which our department has attempted to grasp in the recent past. A possible starting point for elucidating what I mean might be the ambiguous German term used to refer to the field: "Englische Wirtschaftssprache".

What exactly does Englische Wirtschaftssprache mean? Consider the various emphases and differing focuses of some of the possible translation equivalents: 'English of business', 'English in business', 'English for business' and 'Doing business in English'. Then given the ambiguity of the German term: also 'English of economics', 'English in economics', 'English for economics' and 'Doing economics in English', or the 'language of economics and business in English', 'English for students of economics' (EAP) or 'English for prospective business people' (EOP), to mention just a selection of the myriad possibilities. Clearly we can see that all the aspects hinted at could well be legitimate areas of focus.

2.6 Content-based language teaching and ESP

Certainly, what all these characterizations have in common is that at their centre you find the English language needs of second language learners "for whom the learning of English is auxiliary to some other professional or academic purpose", as Henry Widdowson (1983) puts it. LSP courses have long been aimed at preparing learners for real-world demands. Our BE-courses are primarily designed to equip students with the content of business English and a familiarization with the use of English in business settings: business skills, mastery of business situations in English, ability to deal with content specific to areas of business such as accounting, insurance, banking, economics, marketing, personnel management and so on.

At this point some thoughts on content-based language teaching are in order. 'English for business and economics' is a perspective (adopted at the WU), certainly as far as the over-all thrust is concerned. This is true for teaching and logically when it comes to examinations we also see that this is their focus. As we have said, BE teachers are asked to let the content dictate the selection and sequencing of language items to be taught and not the other way around. The activities of the classes -- the proseminars in part I and the seminars in part II, as well as the courses of academic lectures offered in both Part I and Part II -- are geared to stimulating students to think and learn through the use of the foreign language. Through communicating in English, through using English to grapple with their specialist content and terminology, they come to expand their mastery of English.

We can safely assume that it is nowadays generally agreed that there is a close relationship between concepts to be learned and the language used to teach and learn them. Moreover, who can doubt, either, that linguistic abilities are integral for reasoning, argumentation and the expression of factual knowledge? The close integration between academic and intellectual skills, such as presentation and explanation, and their articulation and expression via the medium of language (whether mother tongue or foreign language) is also generally acknowledged in business English studies (cf. Alexander 1988). Indeed it seems that difficulties in solving reasoning problems may be due equally or more so to the linguistic properties of language than to the inherent difficulty of the cognitive processes specific to concepts and propositions. That this is not an unproblematic observation to make is evident. But once one has determined to take up the challenge posed by the use of English as a world language, mentioned at the beginning of this section, there can be no going back.

The intellectual challenge for individual learners and students studying in and through the medium of English is no mean task. Nor is the intellectual and academic demand on lecturers to be proficient in the subject matter of business and economics something to be overlooked. This makes the suitability of such an approach for a course of university studies all that more obvious. See Gaffield-Vile (1996) and Brinton, Snow & Wesche (1989) for more discussion of content-based language instruction. It may sound glib to propagate the subject integration of the language learning and teaching process. Demonstrating that it is indeed a serious issue may entail trying to make explicit some of the assumptions underlying it as well as some of the likely problems.

2.7 Some issues raised by content-based second language instruction

There may be a number of ways of addressing the issues. Firstly, are subject integration and content-based second language instruction the same thing or variations on the same theme? Secondly, are we teaching content in order to expand language competence? Thirdly, are we focusing on business subject matter, and, just by the way, doing it in English? In the space available here we can do no more than briefly comment on these issues.

We are familiar with research over the past 30 years or so which has looked at the close relationship between concepts to be learned and the language used to teach and learn them. It is a truism in educational circles that "Linguistic processes are integral for reasoning and expression of knowledge". We have all encountered students who have difficulties in solving reasoning problems. As mentioned, also, we know that a large percentage of these difficulties stems equally, or more, from weaknesses in linguistic abilities rather than from failing to grasp the inherent difficulty of the propositions and concepts specific to the problem. Although, here again, we have to beware that we do not unnecessarily create dichotomies and thus create oppositions which in individual student cases may be more generally linked.

Clearly such analytical questions may serve to mask the fact that we may more likely be being confronted with a pragmatic situation where English is increasingly being used as the medium of instruction at university level in countries where the first language is not English. Which came first? The principled attempt to make sense of what we ought to be doing, or the almost imperceptible shift in communicational practices and international pressures?

Martin Herles neatly formulates what could equally be conceived of as a real dilemma or a straw-man in his article (1996) "Business English or Business in English -- teaching form and substance at university level". I myself do not accept that such dichotomies are helpful. We know these are the intellectual baggage or inheritance of our western scholarship tradition, where we may have been trained to see things dualistically in "either-or" categories. If, instead we adopt a monist approach and use "more-or-less" categories, perhaps we can come to see that business English or business in English is neither a dilemma nor a straw-man. For it is a multiple activity. The analytical division should not be confused with a holistic capability and process which each has to develop. We should be thankful for this.

The status quo of business English with the educational and occupational developments it has set in motion have come about as a result of pragmatic responses. This is a fact of life which we do well to accept and not as something to be bemoaned, reformulated or theorized away. Hence we will see that such university departments as the department of business English at the Vienna University of Economics and Business Administration are faced with an exciting challenge both academically and professionally. As long as we are prepared to face up to our responsibility to provide some intellectual and developmental leadership in the moulding and shaping of the educational and curriculum input, we will find that there is much for young academic researchers and teachers in the area of business English or English for economics and related disciplines to get their research and development teeth into.

This final section turns briefly to some of the controversies, special areas, preoccupations and expected avenues we shall be going down in the near future. These are in the first instance of a threefold nature. There are the directions in which teaching can be usefully overhauled. This is the issue of curriculum planning and development in response to novel external needs and demands. Then we need to highlight some of the areas which have an internal dynamic underlying them in part, in which further research into English for business studies, especially, for academic reasons, might be focused. And thirdly, some of the implications for teachers and their expected qualifications will be discussed. It would appear that a double set of qualifications in the ideal case would be desirable.

3.1 Curriculum development

New pressures have come to affect our curriculum development. Real-world pressure or changes in macro-societal and economic circumstances. For instance, the increasing requirements for students to communicate both academically, in courses of study abroad, as in the European Union programmes, or in occupational tasks on work placements (Alexander, 1988 and 1991). In adult education and in-company training programmes we have noted the rapid shift towards communicative objectives in the past 15 years (see Alexander, 1983). As English has begun to become ELF (English as a Lingua Franca), so have methods and materials and examination procedures served to affect and influence what counts as business English (cf. Alexander in press). But related to this is also the issue of what assumptions about economics and business are held by teaching staff. What are the objectives of subject experts?

3.2 What economics or business teaching is about: assumptions

In this context I can do no more than lay open the issue. Clearly we can benefit by stating explicitly some of our underlying assumptions and unspoken presuppositions held concerning the scope of the subject matter of business studies, economics and the mix of management and other topics offered at the Vienna University of Economics and Business Administration. For example, how do we go about ascertaining what we need to teach. One aspect we need to consider concerns the implications for how such subject matter components or modules can be realistically integrated with the teaching programme in the department and how and at which specific stages in the curriculum they are sequenced. Like most things in human existence, serial, one-thing-after-another-approaches are called for. "First things first," may well be a workable starting point. A curriculum system which nominally has a Part I and a Part II macro-architecture will seemingly lend itself to selectional and staging criteria precisely along such lines. A discussion of minimal requirements may be as far as we need to proceed initially. If so, so much the better. Perhaps it suffices to simply get such statements out into the open. And, naturally enough, we also need to think through what consequences the subject matter treatments have for language proficiency components and separate language skills.

In particular, we need to underline the insight that knowledge of language and knowledge of the world (and hence economics, etc., i.e., subject matter) are not incompatible. They are interlinked. I have already made this general point. Economists themselves are becoming more self-conscious about how their discourse itself constitutes a sizeable portion of the discipline's thrust (cf. Alexander 1996b and in press). This point perhaps needs little mention in a context in which the policy of linking business and economic subject matter with business English learning is broadly accepted as a desirable goal. There may arguably be differences of opinion about the way or the trajectory to be pursued towards this goal.

This is what the syllabus or curriculum planning component in our thinking is about: how to devise the means, and the most economical at that, for achieving the stated goals. Perhaps we need to stress that we 'learn' or acquire both systems of academic knowledge and foreign language knowledge via activating our textual knowledge. Certainly a textual focus is one which some of my former colleagues, for example at Birmingham University, UK, have found very helpful. (I shall say little about this here. See my review of Henderson, Dudley-Evans and Backhouse, Alexander 1996b.) There is a related point I can bring in at this juncture.

3.3 Academic monitoring programme and research

Where subject experts are engaged in lecturing in English on management and related topics in an Austrian university setting it is evident that some form of academic monitoring programme and research project can be of assistance in assessing how effective such teaching is and for making recommendations for improvements and ongoing curriculum development. A useful research paradigm would be the academic lecture comprehension process and its implications for active academic lecturers (see Flowerdew 1994).

This is where there is a key consultant role to be played by the department of English Language with especial reference to business English. Our research activities and experience have already addressed such issues. Moreover, the department remains very closely in touch with the language teaching and learning research which is proceeding on an international plane in the area of content-based English language programmes. (Cf. Flowerdew, Gaffield, etc.)

3.4 Implications for teachers and their expected qualifications

Let us now turn very briefly to some of the implications for teachers and their expected qualifications such a content-based English language programme entails. It would appear that a double set of qualifications in the ideal case would be desirable. If, as is currently the case, this is not feasible, then teachers should be encouraged to obtain the necessary additional qualification. This has been a successful strategy in the case of our own department.

I move on lastly to implications of the foregoing for examinations

3.5 Implications for examinations

Since content-based second language instruction is based on the assumption that language can be effectively taught through the medium of subject matter content, this must be validly dealt with and considered when examining students. (I have already discussed some of these issues elsewhere in Alexander 1988.)

Certainly there will be implications for examinations in our content-based curriculum. The experience of a Finnish-based colleague provides some useful insights into what one might aim for on the side of communicative skills (see Marsh, 1991). What do we in Vienna expect our degree examinations to examine? The written papers? The orals or vivas? Can there be a principled solution to examination setting? Perhaps not. Rather we require a pragmatic response which simultaneously encapsulates the needs and demands which the wider world of English for business and economics provides as input. The link to the objectives and curriculum are paramount. But I have no space to pursue this aspect here.

In conclusion, I would like to stress that ESP, and BE in particular, almost by definition, can scarcely deal with the universal. Our individual institutions and national settings make specific and sometimes idiosyncratic demands upon our resources. To be sure, we can learn much from observing what has gone on in the past, what people do in other countries and indeed in comparable institutions. This is why the international framework of a professional association such as the International Association of Teachers of English as a Foreign Language (IATEFL) and its SIGs (Special Interest Groups) can provide sustenance and support. But having said this, I must stress that we have individually to learn to walk by ourselves. Perhaps we can profit by observing how our colleagues' gait and posture looks elsewhere and how they have managed to deal with the terrain in their own neck of the woods. It is in this spirit that this contribution is to be taken. I leave it up to, or, in modern parlance, down to you to make of it what you will.

* Paper given at ELT Links British Council/IATEFL SIG Symposium, University of Vienna, 26-28 September 1996.

| economics | business administr. |

commerce main for.lang. - 2nd. for.lang. |

business education |

| Part I |

obligatory subject PS I (2 hours) oral exam |

obligatory subject PS I (2 hours) oral exam |

obligatory subject PS I (2 hours) oral exam |

obligatory subject PS I (2 hours) 1st diploma |

optional subject PS I (2 hours) oral exam |

| Part II |

optional subject English for foreign trade prerequisite: PSIII(2hours) oral exam or English as no English in PS I (2hours) oral exam |

optional subject English for foreign trade prerequisite: PSIII(2hours) oral exam or English as no English in PS I (2hours) oral exam |

obligatory subject PSIII(2 hours) 2nd diploma |

optional subject English for foreign trade prerequisite: oral exam or English as no English in PS I (2hours) oral exam |

References

Alexander, Richard J. (1983): "Communicative syllabuses and communicatively oriented textbooks: the theory and practice in adult English teaching in the Federal Republic of Germany". In: L.A.U.T., Series B, Paper 90.

Alexander, Richard J. (1988): "Examining the spoken English of students of European business studies: purposes, problems and perspectives". In: System 16, 41 - 47.

Alexander, Richard J. (1991): "How specific should English for Business Purposes be?" In: Pluridicta 20 (Odense, Denmark) ISSN 0902 - 2406.

Alexander, Richard J. (1996a): "Teaching International Business English". In: English Language Teaching News 28, February 1996, 25-26.

Alexander, Richard J. (1996b): Review of W. Henderson, T. Dudley-Evans and R. Backhouse (eds.): Economics and Language. In: Applied Linguistics 17, 1: 143-145.

Alexander, Richard J. (in press): "The recent register of economics. Article No.: 163". In: H. Steger and H. E. Wiegand (Hrsg.): Fachsprachen. Languages for Special Purposes. Ein internationales Handbuch zur Fachsprachenforschung und Terminologiewissenschaft. Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter.

Brinton, Donna M., M. A. Snow & M. B. Wesche (1989): Content-Based Second Language Instruction. Boston, Mass.: Heinle & Heinle Publishers.

Flowerdew, John (ed.) (1996): Academic Listening. Research Perspectives. Cambridge etc.: Cambridge University Press.

Flowerdew, John and Miller, Lindsay (1996): "Lectures in a Second Language: Notes Towards a Cultural Grammar". In: English for Specific Purposes 15/2: 121-1440.

Gaffield-Vile, Nancy (1996): "Content-based second language instruction at the tertiary level". In: ELT Journal 50/2, 108-114.

Herles, Martin (1996): "Business English or Business in English - teaching form and substance at university level". In: English Language Teaching News 28 (Feb.), 46-47.

Johnson, Christine (1993): "State of the art article: Business English". In: Language Teaching 26, 201-209.

Jones, Leo and Alexander, Richard J. (1996): New International Business English. Communication skills in English for business purposes. Student's Book. Cambridge etc.: Cambridge University Press.

Lewis, Michael (1993): The Lexical Approach. The State of ELT and a Way Forward. Hove: Language Teaching Publications.

Mackay, R. & Mountford, A. (eds.) (1978): English for Specific Purposes. London: Longman.

Marsh, David (1991): "The Finnish Foreign Language Diploma for Professional Purposes" In: Pluridicta 19 (Odense, Denmark) ISSN 0902 - 2406.

Pickett, Douglas (1989): "The Sleeping Giant: Investigations in Business English". In: Language International 1.1, 5-11.

Robinson, P. C. (1980): ESP(English for Specific Purposes). Oxford: Pergamon Press.

St John, Maggie Jo (1996): "Business is Booming: Business English in the 1990s". In: English for Specific Purposes 15/1, 3-18.

Widdowson, Henry (1983): Learning Purpose and Language Use. Oxford: Oxford University Press.