In this contribution I would like to present some ideas on the application of valency theory to the analysis of English. The account provided will be rather sketchy and should be seen as part of an attempt to provide a more comprehensive view of English complementation patterns within a valency framework.

The ideas that I will develop here arise from work on a valency dictionary of English that I undertook with my co-editors David Heath, Ian Roe and Dieter Götz and which we expect to be published soon.1 While work on the English Valency Dictionary has shown the usefulness of the valency concept for lexicographical purposes, applying the theory to English has also opened up a large number of theoretical problems which deserve to be discussed. Furthermore, the overall aims of a dictionary, above all the requirements of user-friendliness, make it impossible to use the same descriptive categories that may seem appropriate for a more theory-oriented approach.

Given the large number of publications on the concept of valency, both within valency theory itself and within many other syntactic or lexicological theories, the main purpose of the following remarks is to provide an introduction to what I envisage as one possible model for describing valency relations in English. If some of the ideas are presented in a rather sketchy way, this is because the focus of this contribution lies on the basic principles of the theory and the general approach taken rather than on a comprehensive description of English valency structures as such.

Since existing valency descriptions of English (Emons 1974, Allerton 1982) differ widely with respect to some of their basic descriptive principles and since the present approach differs in important ways from both, it is necessary to state a few basic principles on which the following outline is based:

Valency theory takes an approach towards the analysis of sentences that focuses on the role that certain words play in sentences with respect to the necessity of occurrence of certain other elements. This largely, though not completely, coincides with what is often called complementation.

Since valency theory primarily addresses this question, it does not claim to give a comprehensive account of English syntax as attempted in grammars of English. Nor could it claim to present a model of language in the way that theories such as modern versions of phrase structure grammar or the various formulations of generative syntax do. Although valency theory can be seen as a subtheory of the model of dependency grammar3 as formulated by the French linguist Lucien Tesniére, up to a point it can also be regarded as being agnostic with respect to such general theoretical issues in the sense that insights provided by valency theory can be integrated relatively easily into a large number of differing theoretical approaches.

However, the particular perspective opened up by a valency approach provides arguments more easily compatible with some views of language than with others because it highlights the enormous dimension of individual, word-specific knowledge that is part of a native speaker's competence. Also, the application to English of a theory that was largely developed on the basis of other European languages may result in questioning the appropriateness of some of the categories that are established in such accounts of English complementation as the Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language (CGEL 1985) by Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik or the modified approach presented in English Syntactic Structures by Aarts and Aarts (1982/²1988).

Since the ideas of valency theory are probably most closely related to the ideas of approaches such as that of CGEL or that of Aarts/Aarts, it seems to make sense to highlight crucial differences between these and the approach outlined here. This is not to deny, of course, that valency phenomena have received considerable scholarly attention within other frameworks such as word grammar, functional grammar, lexical-functional grammar and many others, too. Although research carried out in such frameworks will also be made use of here, discussion of all principal differences between the valency approach and these other models would involve far too many fundamental issues and distort the presentation of the valency model so that with regard to the development of categories, other valency studies and approaches such as those of CGEL (1985) and Aarts/Aarts (1988) will provide the main points of reference.4

1.2 The development of valency theory

Valency theory originated in the work of the French structuralist Lucien Tesnière, in whose theory of dependency grammar valency plays a considerable role. However, the main impetus for the development of valency theory as such came not so much from work within dependency grammar as from foreign language teaching. The publication, in 1968, of the first valency dictionary of German verbs, the Wörterbuch zur Valenz und Distribution deutscher Verben, by the two East German linguists Helbig and Schenkel marks an important step in the development of the theory. Numerous theoretical publications, especially those by Helbig (1971 and 1992) and Bondzio (1971) or Welke (1988) in East Germany, and Heringer (1970 and 1996) and Engel (1977) in West Germany, have established it as arguably the most widely used model of complementation within German linguistics and have resulted in the publication of valency dictionaries not only for German (cf. eg. Engel and Schumacher 1976), but also for languages such as French (Busse/Dubost ²1983; Zöfgen 1985), Rumanian and Latin.

In view of the importance of the theory within Continental linguistics it is rather remarkable that its application to English has been relatively limited. Perhaps it is significant that the first studies devoted to the analysis of English complementation within a valency framework (Emons 1974 and 1978; Allerton 1982; Herbst 1983) were written at European (in the sense of non-British) universities, however the concept of valency has been gaining ground in British linguistics in recent years as well (cf. Leech 1981 and especially Matthews 1981, Somers 1984), especially since scepticism towards generative linguistics has been growing. Furthermore, a considerable number of approaches not directly linked, or indebted, to valency theory have pursued ideas similar to those of the valency approach in recent years by putting more emphasis on the central role of the verb etc. Nevertheless, a certain neglect of valency theory amongst British (and especially American) linguistics cannot be denied. This may be due to a variety of factors: English in this century has finally replaced Latin as the language on which the theoretical analysis of language is based, so theories not originating from English may have received less attention in the English-speaking world; as far as foreign language teaching is concerned the fact that the concept of valency may appear to be particularly appealing for case languages may have been as important as the fact that for English there already was a long tradition of teaching materials and dictionaries taking account of such problems in a slightly different form. Given the standard of the coverage of verb complementation in general learner's dictionaries such as the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English or the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary it is perhaps not surprising that the English Valency Dictionary will be the first such dictionary for English.

2 Basic categories of valency theory

2.1 Syntactic and semantic valency

2.1.1 Complements and adjuncts

Valency theory attributes a central role to the verb seeing the verb as the element that determines how many other elements occur in a sentence. Thus, in sentences such as5

(1a)AC

Newlyn lies at the western end of Mount's Bay.

(2a)AC

By the 1880s there was a well-developed tourist industry in west Cornwall.

(3a)AC

By the turn of the century Newlyn had changed.

it is clearly the verbs lie, be and change that determine the structure of the sentence since lie requires the presence of a subject and an adverbial, be also requires two elements, whereas change only requires a subject:

(1b)

*Newlyn lies.

(1c)

*lies at the western end of Mount's Bay.

(2b)

*By the 1880s was a well developed tourist industry in west Cornwall.

(2c)

*By the 1880s there was in west Cornwall.

(2d)

There was a well developed tourist industry.

(3b)

Newlyn had changed.

(3c)

*By the turn of the century had changed.

It is a verb's property to determine the number of other elements that have to occur in a sentence for it to be grammatical that has been termed its valency. However, since not all elements are dependent on a particular governing element, a distinction has to be made between elements which are - and which thus are part of the valency of a word - and elements which are not. The former are often referred to as complements (actants in Tesnière's; Ergänzungen in established German terminology; Allerton 1982 uses the term verb elaborators); the latter as adjuncts (circonstants and Angaben respectively, termed peripheral elements by Matthews 1981). Adjuncts differ from complements in that, firstly, their occurrence in a sentence is not dependent on the governing word (or predicator) of the sentence and, secondly, they are not determined in form by the predicator.

Thus, adjuncts such as by the 1880s or in west Cornwall can occur in a large number of sentences; i.e. they are - to employ a term first used by Heringer (1968) - freely addable:

(2e)

By the 1880s, the Tamar Bridge had been built.

(2f)

Many stone circles can be found in west Cornwall.

(2g)

Newlyn can be regarded as one of the most important fishing ports in west Cornwall.

etc.

It is obvious that adjuncts are not totally freely addable since their occurrence is subject to general semantic compatbility but the important distinguishing criterion with respect to complements is that the occurrence of adjuncts is not in any way dependent on particular lexical items.6

2.1.2 Quantitative and qualitative - syntactic and semantic valency

Since adjuncts occur independently of the presence of individual words in a sentence, they lie outside the scope of valency. The term valency comprises elements that are word-specific in the sense that their occurrence cannot be explained in terms of generalizable properties; rather their occurrence is dependent on an individual lexical item, which will be called its governing element, or, for the sake of consistency with other theories, predicator.

Complements are those elements that satisfy the valency requirements of a predicator at the formal syntactic level, but this syntactic valency finds its corrollary at the level of semantics so that a distinction betwen syntactic and semantic valency can be made.

The syntactic valency of a word can then (provisionally) be defined as the number of complements it takes.

At the level of form, the valency of a predicator is seen in terms of the complements that a predicator takes. This involves:

(4a)DC Amy went and kissed him.

where the complement Amy represents one argument ('the person who kisses') and him the other ('the person who is being kissed'). In the case of a plural subject, however, as in

(4b)DC I doubt that they ever even kissed.

there is only one complement, which expresses both arguments at the syntactic level. Similarly, one could argue that in

(2a)AC By the 1880s there was a well-developed tourist industry in west Cornwall.

there is a complement of be without necessarily expressing any argument. Since a considerable amount of research has been carried out on the argument structure of predicators - ranging, e.g. from Fillmore's (1968) case grammar approach to Haegeman's (1991) outline of argument structure - , the following outline will be concerned with syntactic valency. Nevertheless, complements will be seen as (possibly complex) linguistic signs which consist of one or more morphemes and which express arguments.

2.2 Obligatory and optional complements

2.2.1. Three types of complement

The distinction between complements and adjuncts is, as will become apparent, by no means clear-cut but rather a typical instance of gradience. Bearing in mind the prototypical character of these categories it seems appropriate to divide the elements occurring in a sentence into four groups with respect to their relation to the governing word: obligatory complements, optional complements, contextually optional complements, and adjuncts.

2.2.2 Obligatory complements

Obligatory complements and adjuncts, the elements at the two opposite ends of the scale, can be most easily distinguished from one another:

Obligatory complements are complements which have to be expressed for the predicator to be used in a grammatical sentence.

Thus in

(1a)AC Newlyn lies at the western end of Mount's Bay.

both Newlyn and at the western end of Mount's Bay are obligatory complements because neither element can be deleted. Sentence (1a) is a good illustration of the fact that obligatory complements are semanteme-constituting (Brinker 1977: 115) since they cannot be deleted without making a sentence either ungrammatical or changing the meaning of the predicator: A sentence such as

(1b) Newlyn lies.

could of course be seen as meaningful if Newlyn were taken as a person's name but the meaning of lie would also be different. In the same way, a verb such as consider has an obligatory valency of 2 in the sense 'think about carefully' and of 3 in the sense 'have a certain view of someone or something':

(5a)DC Students, in considering a college, should look carefully at who teaches lower-division courses.

(5b)DC His

enemies consider him dangerous.

2.2.3 Optional and contextually optional complements

Whereas the distinction between obligatory complements and adjuncts can be established relatively easily by means of a deletion test, optional complements take an intermediate position since they can be deleted but still belong to the valency structure of a predicator being determined by it in their form. Thus, there does not seem to be a difference in the meaning of read in (6a) and (6b) and that of object in (7a) and (7b).

(6a)DC

And how can you possibly stop reading now?

(6b)DC

She'd go off to bed and read a book.

(7a)DC

He looked directly at me for the first time, challenging me to object.

(7b)DC

Most creative people object to the notion that the work they do comes easily.

Despite the deletability of the underlined elements in (6b) and (7b), it would not be appropriate to classify them as adjuncts. The most important criterion for regarding them as complements is that their occurrence is word-specific in the sense that their form (noun phrase and toprepositional phrase) is dependent on the predicators read and object. For this reason, such elements have been called optional complements.

Allerton (1982) outlines a very important difference between optional complements, which refers to the conditions under which a complement can be deleted. Whereas a sentence such as

(6c) She was reading all afternoon.

seems a perfectly natural utterance, which can serve as an answer to a question of the type

(6d) What did she do yesterday?,

this is not true of a sentence such as

(7c) He objected.

In other words, with a verb such as object a monovalent use only seems possible if it is clear from the context what somebody objected to, whereas in the case of read no such contextual specification is required. Allerton (1982: 68-9) has introduced the terms contextual deletion for the former type (object, watch) and indefinite deletion (read) for the latter.8 However, the use of the term deletion implies that the divalent use represents a primary pattern which is modified through a process of deletion, which is a view that we would not subscribe to. In particular, the term deletion seems inappropriate if it is taken to mean "verbatim recoverability"9 because no such requirement holds in this case. It is not necessary for the hearer/reader to be able to "retrieve" any original wording supposedly underlying the divalent sentence

(7d) Most creative people would object.

Quite the contrary, it is irrelevant whether (7b) contains the word idea or notion or whether the same meaning is expressed in a totally different way. What matters is that the hearer/reader is able to identify the referent of the argument contained in the complement structure of the corresponding predicator. Thus, terms such as contextually optional complement and optional complement seem more appropriate:

A contextually optional complement is an element that is dependent on the predicator in form but which does not have to be expressed syntactically if and only if the argument it represents is identifiable from the context.

An optional complement is an element that is dependent on the predicator in form but which does not have to be expressed syntactically at all.

2.3 Optional

complements and adjuncts

2.3.1 Syntactic test criteria

The distinction between optional complements and adjuncts has been central to the development of valency theory. Numerous syntactic tests to establish the distinction have been developed for languages such as German10, but also for English.11 None of them are really satisfactory because all such tests can do is to find common syntactic properties for elements that share the same defining criteria.

2.3.2 One-word adverbs or adverbial clauses

Some of the criteria that have been suggested simply have to do with the fact that adjuncts are typically adverbials. This means that they are not determined in their morphological form by the governing word. Thus, in a sentence such as

| (8a)AC | Following Ben Nicholson's first visit to St Ives he painted a number of landscapes and sea paintings of Porthmeor beach. |

the optional complement can only be realized by a noun phrase or a who-/what-clause:

(8b) He painted what he saw.

The adjunct is not subject to any such restrictions determined by the predicator of the sentence:

It is especially the possibility of replacing an adjunct by an adverbial clause (as in (8g)) or by a one-word verb adverb (as in (8f)) that has been taken to establish the distinction between adjuncts and optional complements.12 It is important to point out, however, that the adjunct criteria also apply to obligatory complements if they take the form of adverbials:

(1a)AC Newlyn lies at the western end of Mount's Bay.

(1d) Newlyn lies there.

2.3.3 Positional mobility

One criterion that can be used to establish the distinction between complements and adjuncts is positional mobility. The order of complements is relatively stable and cannot be changed without changing the theme/rheme-structure or the information focus of the sentence. Thus

(8h) A number of landscapes and sea paintings of Porthmeor beach he painted.

would certainly seem marked in a way in which (8i) is not

| (8i) | He painted a number of landscapes and sea paintings of Porthmeor beach following Ben Nicholson's first visit to St Ives. |

Although deviation from a thematically unmarked sentence structure is also a matter of degree, positional mobility can be considered an important indicator with respect to the adjunct status of an element. In this respect, similar restrictions seem to apply both to obligatory complements realized by adverbials and to optional complements:

(1e)

*At the western end of Mount's Bay Newlyn lies.

(1f)

At the western end of Mount's Bay lies Newlyn.

2.3.4 Question tests

The permissible types of question form are a very useful criterion in the case of adjective valency. Complements can typically be elicited by questions containing pronominal forms such as who or what, whereas adjuncts can typically be elicited by adverbial question forms:

| (9a)DC | Tickets will be available at the door. |

| (9b) | Where will tickets be available? |

| (9c) | *What will tickets be available at? |

| (9d)DC | The peaceful use of nuclear energy should be made available to non-nuclear states. |

| (9e) | Who should the peaceful use of nuclear energy be made available to? |

| (9f) | *Where should the peaceful use of nuclear energy be made available? |

This question criterion can also be applied to the analysis of verb valency. Thus the who-/what-questions clearly elicit the complements in the case of

| (8a)AC | Following Ben Nicholson's first visit to St Ives he painted a number of landscapes and sea paintings of Porthmeor beach. |

| (8j) | Who painted a number of landscapes and sea paintings of Porthmeor beach? |

| (8k) | What did he paint? |

whereas the adjunct clause requires an adverbial question form

| (8l) | When did he paint a number of landscapes and sea paintings of Porthmeor beach? |

Unfortunately, who/what-questions are also possible for a number of elements which on the basis of the defining criteria ought to be regarded as adjuncts since they are clearly optional:

(i) purpose-phrases and purpose clauses

| (10a)AC | In March 1930 Wood was in London for the opening of Cochrane's Review. |

| (10b) | What was he in London for? |

| (11a)AC | To achieve a more emotional relationship with his subject, Lanyon chose specific sites in Cornwall. |

| (11b) | What did he choose specific sites in Cornwall for? |

(ii) with-phrases expressing accompaniment

| (12a)AC | Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth had invited the two most promising younger artists, John Wells and Peter Lanyon, to exhibit with them. |

| (12b) | Who were they invited to exhibit with? |

Since such elements are clearly freely addable, it is obvious that the who-/what-question test, which also proves problematical with certain types of locatives or metaphorical uses of locatives13, cannot be considered to be entirely satisfactory.

2.4 Different types of necessity

2.4.1 Valency and communicative necessity

What has to be borne in mind that valency classifications of the kind illustrated above - especially the distinction between adjuncts and the three types of complement identified - is a kind of abstraction despite the surfaceorientation of the valency approach. What is meant by describing adjuncts or optional complements as deletable is that their deletion would not result in an ungrammatical sentence. It is obvious that deletion of such an element could however seriously affect the communicative value of an utterance in pragmatic terms.

Thus, for example, while in a sentence such as

| (13a)DC | The coastguards recommend using the inshore passage from this time until up to two hours before high water. |

the time adverbial is clearly an adjunct and is thus to be considered deletable, it may well contain essential information in the context in which the utterance was made. In particular,

(13b) The coastguards recommend using the inshore passage.

would not be acceptable as a reply to the question

(13c) When should the inshore passage be used?

However, it is obvious that communicative necessity which is concerned with the rhematic content of an utterance is a different phenomenon from the kind of valency necessity discussed above.

2.4.2 Subjects: valency and structural necessity

In the above analyses, subjects of verbs have been classified as obligatory complements. Although this is common practice in valency theory there may be good reason to question the wisdom of such a classification. The subject in a sentence such as

(5b)DC His enemies consider him dangerous.

is classified as an obligatory complement because of the unacceptability of

(5c) *consider him dangerous.

The reasons for the unacceptability of (5c) may be independent of the valency structure of the verb consider, however, because sentences containing only two complements are perfectly natural with this meaning of consider as in

(5d)DC The telephone has come to be considered a necessity.

Passives are not the only instances where the complements that function as subjects in the corresponding active sentence are not expressed. For instance, it seems that imperatives such as

(14)DC Pack your photo gear well, insure it to its replacement value.

share the defining criteria of contextually optional complements because the referent of the argument can easily be identified. Furthermore, certain types of subordinate clause such as

(1d) Lying at the western end of Mount's Bay, Newlyn attracted many artists.

present a similar problem in that they can be viewed as subjectless.

For these reasons, the mere fact that an element occurs as the subject of a verb should not be considered a sufficiently good reason for classifying it as an obligatory complement (Herbst/Roe 1996). The obligatory nature of such complements in active sentences is entirely due to a different kind of necessity to be termed structural necessity, which, in this case, is a requirement that main clauses that are not imperatives have a subject in English. Thus, it would be wrong to classify the subject of watch in

(15a)DC Someone was watching her.

(15b)DC The men just watched and laughed.

as obligatory because they cannot be deleted since in a passive sentence such as

(15c)DC We are being watched.

the subject cannot be deleted either. Nevertheless, on the basis of sentences such as (15b), her in (15a) would be seen as a contextually optional complement. Such observations show that although for the sake of methodological simplification it may be convenient to determine the status of a complement as obligatory or optional on the basis of active declarative sentences alone, this results in a misleading analysis. It thus seems appropriate to separate structural necessity and necessity at the level of valency. Strictly speaking, obligatory complements should thus not be defined as complements that cannot be deleted but as complements that always have to be expressed.

In fact, these considerations present a strong argument against considering passives as being "derived" from actives. If active and passive sentences are seen as alternative structures, which, of course, exhibit regular correspondences, valency phenomena of this kind can more easily accounted for. This emancipated view of the passive will also influence the classification of complements presented in chapter 3.

3 Complement classes in English

3.1 The levels of valency and sentence structure

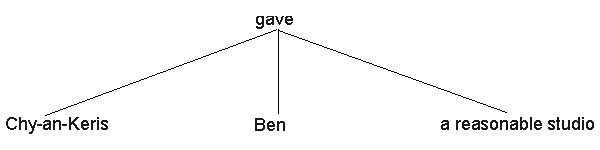

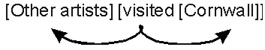

Since the valency of the verb is the decisive factor determining the number of complements required for a sentence to be grammatical, it is the verb that also largely determines the overall structure of the sentence. In dependency theory, this has been taken as an argument in favour of attributing a central role to the verb within the sentence hierarchy and to see the other elements as dependent on it in the sense that the possibility of their occurrence is determined by the valency properties of the governing element. This is often represented in graphs, called stemmata in dependency theory, of the following kind (where the broken line signifies the adjunct-character):

(1)AC Other

artists visited Cornwall in the first half of the nineteenth century.

(2) Chy-an-Keris gave Ben a reasonable studio

.

.

Two properties of such stemmata are made apparent by these examples:

In a way, as Baumgärtner (1970) and Heringer (1970)15 have pointed out, a dependency analysis presupposes a constituency analysis since the constituents are the elements between which dependencies can be postulated. Apart from this, it seems that both views highlight different but equally important aspects of sentence structure. For this reason, it makes sense to combine the two principles, as exemplified, for example, in the type of representation suggested by Matthews:

In particular, it seems that the traditional distinction between subject and predicate can also be fruitfully applied to valency theory. Here, a distinction can be made between a broad view of the category predicate, which distinguishes the subject from the rest of the sentence, and a narrow view, where the predicate consists of the verb and its objects:

| subject | predicate (broad view) |

| Other artists | visited Cornwall in the first half of the nineteenth century |

| subject | predicate (narrow view) |

| Other artists | visited Cornwall |

Although the broad view of the predicate serves to explain the scope of certain pro-forms, it is the second analysis that comes closer to incorporating valency considerations. In a slightly modified form, this is reflected in the approach developed by Aarts and Aarts (1988: 127), who divide the sentence into the obligatory constituents of subject and predicate (which consists of a predicator and complements) and the optional constituent adverbial so that (1) could receive the following representation:

SENTENCE | |||

| SUBJECT | PREDICATE | ADVERBIAL | |

| . | PREDICATOR | COMPLEMENT | : |

| Other artists | visited | Cornwall | in the first half of the nineteenth century |

Since Aarts and Aarts (1988) use the term adverbial to refer to the adjuncts of valency theory and classify adverbs or prepositional phrases that are part of the valency of the verb as complements (thus avoiding one of the pitfalls of the CGEL account of complementation) their analysis comes rather close to a valency approach. Aarts and Aarts do not, however, include the subject amongst the complements of the verb.

An analysis of this kind, which attributes a special status to the subject of the sentence, obscures the fact that the subject is quite clearly realized by an element that is part of the valency of the verb and thus ought to be classified as a complement. On the other hand, a valency description that denies the subject any special status obscures the special conditions of optionality applicable to all complements that can function as subjects. The relationship between active and corresponding passive sentences serves to prove both points.

These difficulties can be resolved by regarding sentence structure and valency as two different levels of description, as was indicated by the distinction between structural necessity and valency necessity in Chapter 2. Such considerations are very much in line with an argument presented by Matthews (1981: 104), who, starting off from the nineteenth century distinction between grammatical subject and psychological subject16, points out that two uses of the term subject have to be distinguished - one of a subject as opposed to a predicate, one of a subject as opposed to an object. This distinction is reflected in Allerton's (1982: 43) categories "surface subject" and "valency subject".

Thus, it seems appropriate to make a distinction - corresponding to that outlined by Aarts and Aarts - between subject, predicate and adjunct at the level of sentence structure and to use the terms predicator and complement referring to the level of valency.17

| STRUCTURE | subject | predicate | adjunct |

| VALENCY | complement | predicator (+ complements) | : |

Valency, quite clearly, has to be seen as a phenomenon to be accounted for within the lexicon of the language.18 Since, as Chapter 2 has shown, different senses of a word can open up different valency structures, valency must be seen as a property of lexical units as defined by Cruse (1986: 77), i.e. as "the union of a lexical form and a single sense".

The relationship between the valency structure of a lexical unit and its occurrence in discourse has a parallel in the semantic properties of a polysemous lexical item and its occurrence in discourse. The valency structure of a lexical unit contains a potential of the realizations in actual sentences depending on the degree of optionality and the form of its complements; one of which is selected in the occurrence in an actual sentence in very much the same way as one sense of a polysemous item is selected when it is used.

In an actual sentence, the complements fill positions in the two obligatory constituents of sentence structure since they occur either as the subject of the sentence or as elements within the predicate. A complement can thus be seen as a combination of its formal realization in sentence structure and the semantic role expressed of the argument by it. Since the relationship between active and passive sentences is not regarded here as one in which the one structure is derived from the other but as alternative forms of expression, where appropriate, the different morphological forms a complement takes in active and passive clauses must be part of its formal specification.

Since complements are seen as forms expressing semantic roles, the formal classification of the complements need not, and indeed should not, reflect any semantic properties (because this is part of the semantic description of the same complement). This is one of the reasons why traditional categories such as object or attribute provide an unsuitable basis for the description of complement classes, at least as long as semantic criteria are crucial to their definition.

In the approach taken here, the formal aspect of the complement will be described in terms of the following specifications:

(i) its morphological properties

(ii) its positional properties

(iii) its ability to occur as subject.19

3.2.2 Morphological properties of complements

The constituent level at which complements are identified is that of the phrase or clause. The classification of phrases employed by Aarts and Aarts (1988), which is similar to that of CGEL (1985)20, will be used as a basis to determine the following complement classes:

3.2.3 Positional properties: [C]1, [C]2

Information on the position or sequence of complements is largely redundant since it can be deduced from the morphological type of complement and the ability to occur as subject. Since, for instance, NP-complements tend to precede PP-complements etc., no specification as to their sequence will be provided. This will only be done in cases where two otherwise formally identical complements occur with the same lexical unit. In this case, the figures 1 and 2 will be used to indicate their relative position to each other.21

3.2.4 Ability to occur as subject

3.2.4.1 [C]a, [C]p, [C]o

There are several reasons why ability to occur as subject should be part of a valency description. Firstly, as has been shown in Chapter 2, classifying complements as obligatory, optional and contextually optional is insufficient because elements that are subjects can be obligatory or optional irrespective of the valency classification on the grounds of structural necessity. It is thus important to specify in the valency description whether a complement can occur as subject in order to make clear under which conditions specifications as to its optionality may apply. Secondly, the ability to function as subject entails a number of formal properties which would have to be part of the formal description of the complements anyway. Thirdly, these complements have different formal properties when they do not occur as subjects.

There are various ways of accommodating this information, however. One would be to simply classify all the subjects of sentences (3a) - (6a) as one complement class:

(3a)AC

She (3A) visited him (3B) frequently in Brittany and Newlyn.

(4a)AC

Newlyn (4A) is a sort of English Concarneau (4B).

(5a)AC

Both (5A) had beautiful natural settings (5B).

(6a)AC

Both towns (6B) had already been discovered by painters (6A).

However, this would mean attributing different valency descriptions to predicators in active and passive sentences. Because of the obvious relatedness of active and passive sentences and because valency is a property of lexical units and not of sentences it may however seem preferable to express the fact that the same semantic roles can be expressed in a different form in the case of (3a) and (6a) but not in the case of (4a) and (5a) by considering them as alternative formal realizations of the same complement.

Possibility of occurrence as the subject of a passive sentence is a distinguishing criterion between complements such as 3B and 6B on the one hand and 4B and 5B on the other so that two complement types will have to be distinguished within the B-group.

Correspondingly, a similar distinction could be made within the A-group since the arguments expressed by 3A and 6A can either occur as subjects in an active sentence or in the form of a byphrase, termed perjects by Allerton (1982), in a passive sentence. However, such a notation would be redundant because it would also coincide with the corresponding distinction in the Bgroup.22

On the basis of these considerations, three values as the ability to occur as subject will be identified for complements [C]:23

| [C]a | the complement can occur |

| : |

|

| [C]p | the complement can occur |

| : |

|

| [C]o | the complement occurs after the verb phrase |

Obvious specifications to go with indices a and p are that

(i) the rules of optionality for subjects apply (ii) if more than one complement is specified as [C]p only one of them can occur as subject in a clause.

Any additional specifications that are necessary for particular complement types will be given below.

3.2.4.2 Restrictions

For a complement to be marked [C]p is a necessary but not a sufficient condition that a passive clause can occur. The fact that some restrictions on the passive are features of a particular verb or verb meaning can easily be accommodated in the valency description by not attributing the particular lexical unit a [C]p. Since have in (5a)

(5a)AC Both had beautiful natural settings.

is clearly a different lexical unit from have in

(5b)QE Everybody had a nice time.

there is no problem in describing the valency structure of (5a) as containing a [C]o and that of (5b) as containing a [C]p to account for

(5c)

*Beautiful natural settings were had by both.

(5d)QE

A nice time was had by everybody.24

However, there are restrictions - discussed at length, amongst others, by Stein (1979: 97-102) - on the use of the passive which do not apply to a complement class as such:

(8) *His head was shaken by the handsome, bald doctor.

Similarly, the use of other passive forms seems to be very restricted and to involve special semantic components such as that of "observable result" (Stein 1979: 80) in cases such as

(9)QE The bed had not been slept in.

Thus there are a number of constraints on the use of the passive which lie outside the scope of a valency description.25 The index p refers to the general ability of a complement class to function as the subject of a passive sentence. It must not, however, not be taken to be applicable to every lexical item that can occur in that complement class or to every context.

3.2.5 Complement classes as formal categories

The distinction between the three types of complement class [C]a, [C]p and [C]o resembles that between such functional categories as subject, object and one for which various names have been used such as predicative (Jespersen 1914), subject complement and object complement (CGEL) or subject attribute and object attribute (Aarts/Aarts 1988), apart from the fact that the passive is often considered to be a derived and not an alternative form. Both CGEL and Aarts/Aarts use such functional labels as the basis for their accounts of complementation. This is not done here for a number of reasons:

Firstly, as the outline below will make obvious, such categories are often established by means of semantic criteria, which in this account is part of the semantic description of the complement.

Secondly, the use of the term object is by no means unambiguous. One might see [C]p as a term corresponding to the traditional notion of object, one characteristic of which, according to CGEL (10.7), is that it "may generally become the subject of the corresponding passive clause". However, as is pointed out in CGEL (16.27) this does not apply to the so-called middle verbs have, lack, suit and resemble. Thus beautiful natural settings in

(5a)AC Both had beautiful natural settings.

would still be classified as a direct object in CGEL, as is, by the way, the to-infinitive of a verb such as want on the grounds that the noun phrase object can become the subject of a passive.26

| (10a)DC | Sinclair was also wanted by Manchester City. |

| (10b)DC | Ireland's new president has said that she wants to extend the hand of friendship to both communities in Northern Ireland. |

| (10c) | *It is wanted to extend the hand of friendship to both communities in Northern Ireland. |

Such inadequacies can, of course, be overcome by a more restricted use of the term object. Thus Aarts and Aarts (1988) use the term object to refer to [NP]p-s and would classify beautiful natural settings in (5a) as a predicator complement; similarly Allerton (1982) makes a distinction between objects, which are passivizable, and objoids, which are not.

Allerton's distinction between valency subjects, objects and objoids, indeed focuses on the same linguistic features as [C]s, [C]p and [C]o. However, given the facts of a verb such as want - where the NP-complement, but not the infinitival complement, can function as a passive subject, - it seems at least more economical to give priority to the morphological information and provide information on the ability to occur as subject in the form of an index. Furthermore, one might argue that by classifying an element as an object in a particular sentence one attributes it a particular function within this sentence. This, however, is at least arguable because the difference between an object and objoid does not concern the sentence under analysis but another sentence which is seen as derived from it. Since this is at least partly understood in Allerton's (1982: 45) model through the distinction between valency subjects and surface subjects, the differences between his and the present approach lie more in the assumed relationship of active and passive sentences and the terminology employed than in the actual classificatory principles.

3.3 Noun phrase complements

3.3.1 Complement classes [NP]a, [NP]p, [NP]o

Despite the marginal role of case marking in English, in the case of noun phrases, examples such as

(3a)AC She visited him frequently in Brittany and Newlyn.

show that case could indeed be used to identify different complement classes. It is obvious that noun phrases with no apparent case markings belong to the corresponding complement classes because they share positional criteria and can be seen to commute with them.27

(3b)

Juliette de Guise visited Stanhope Forbes.

(3c)

His mother visited the painter.

Since subjective case always coincides with occurrence as subject (and the objective case can be considered the unmarked case in English), it is sufficient for this information on case to be integrated into the characterisation of the complement classes:

| [NP]a | a noun phrase which can occur |

| : |

|

| [NP]p | a noun phrase which can occur |

| : |

|

| [NP]o | a noun phrase which occurs |

| : |

|

The noun phrase complements examples (3) - (6) can be classified accordingly:

(3a)AC

She [NP]a visited him [NP]pfrequently in Brittany and Newlyn.

(4a)AC

Newlyn [NP]a is a sort of English Concarneau[NP]o .

(5a)AC

Both [NP]a had beautiful natural settings[NP]o.

(6a)AC

Both towns [NP]p had already been discovered by painters [NP]a.

As has been pointed out above, this description of the NPcomplements entails information on word order. Since this is not sufficient in cases where two complements otherwise having the same specifications (with different semantic roles) occur, their order will be indicated by a subscript.

(2)AC

Chy-an-Keris [NP]a gave Ben [NP]p1a reasonable studio [NP]p2.

3.3.2 Alternative approaches: subject and object attributes

In 3.2.5 it has been pointed out that the distinctions established through the criterion of the ability of a complement to occur as subject approximate those between subjects, objects and objoids, for example. The category [NP]o does not fully correspond to the categories of objoid or predicator complement, however, since both Allerton (1982) and Aarts and Aarts (1988) introduce further distinctions. Thus, while Aarts and Aarts classify beautiful natural settings in (5a) as a predicator complement, they would classify a sort of English Concarneau as in

(4a)AC

Newlyn is a sort of English Concarneau.

as a subject attribute. Subject and object attribute, which correspond to CGEL's subject and object complement, are defined by Aarts and Aarts (1988: 140) predominantly in semantic terms -"what is expressed by the subject attribute constituent is predicated

of the subject" (and correspondingly for the object attribute). The same applies to Emons's (1974) complement class E5.28 Similarly, Allerton's (1982: 83-5) distinction between match objoids, measure objoids and possession objoids is mainly semantic in character.29 Since such semantic properties of complements are covered by the description of semantic valency (i.e. through the assignment of different semantic roles to the various complements), it would seem inappropriate to take them as the basis for identifying different formal complement classes.30

The categories subject and object attribute Aarts and Aarts (1988) posit are parallelled in Allerton's (1982: 81) model by a category that, following Jespersen, (1933) he calls predicative. Allerton (1982: 81) establishes it on the basis of a syntactic criterion, namely "its capacity for being replaced by an adjective phrase with a similar function." Although in many such cases both adjective phrase and noun phrase complementation occur

(4a)AC

Newlyn is a sort of English Concarneau.

(4b)

Newlyn is beautiful.

there are many verbs which permit only one possibility:31

(7)DC

He was elected the first mayor of Tywyn.

(8)DC

She kept quiet.

Since a test such as the one suggested by Allerton would only establish the prototype of categories, but not distinguish them clearly, and since, furthermore, the information that a particular verb takes both an [NP]o complement and an adjectival complement is part of its valency structure anyway, there does not seem to be any merit in distinguishing this type of complement from [NP]o.

3.3.3 An alternative approach: direct and indirect object

In the approach outlined here, the traditional categories of indirect and direct object are distinguished by a numerical index signifying their relative position to each other in the clause. This has the advantage of allowing precise statements as to possible passivization.32 Furthermore, it avoids the ambiguity of the term indirect object. CGEL (10.7) use indirect object only to refer to noun phrases, whereas many traditional grammars use it for the noun phrase object as well as its prepositional paraphrase.

(9a)DC

You can always give me some money.

(9b)DC

Give it to the bride.

What is perhaps more important is the fact that the noun phrase "generally corresponds to a prepositional phrase, which is generally placed after the direct object" is taken as a defining criterion in many approaches such as CGEL (10.7). While in CGEL, this covers cases such as

(10a)CC

Pour me a drink.

(10b)

Pour a drink for me.

Aarts and Aarts (1988: 139) make a distinction between an indirect object, which can be replaced by a to-phrase33, and a benefactive object, which can be replaced by a for-phrase (and "cannot, as a rule, become the subject of a passive sentence".) For Emons (1974: 129), the substitutability of a noun phrase and a prepositional phrase is a reason for establishing a separate complement class E4, which is characterized by the presence of prepositional as well as non-prepositional elements, although he restricts membership of this class to to-phrases since he attributes adjunct status to for-phrases as in (10b).

However, since, as in the case of the subject and object attributes discussed above, the semantic correspondence between a noun phrase and a prepositional phrase will be expressed by semantic roles in the semantic description of the complement, there is no need to specify the character of the complement class any further than by indicating its relative position with respect to another [NP]p with a different semantic role.

3.4

Adjective phrase complements

Adjective phrase complements [AdjP]o occur in sentences such as

(11)AC

Their paintings were tonal and silvery.

(12)AC

He had walked over to Helston, and then to Porthleven, which he found attractive.

(13)DC

She is capable of playing very well.

(14)AC

He found the weather too poor for outdoor walking.

Adjectives phrases can also occur as subjects, but only in pseudo-cleft sentences:

(15) Green is how she wanted it painted.

3.5

Clause complements

3.5.1 [CL]a, [CL]p, [CL]o and the problem of discontinuous realisation

All three types of complement - [C]a, [C]p, [C]o - can be realized not just by phrases, but also by clauses:

| (16a)AC | To take a line from top to bottom and keep it alive was a real challenge. |

| (17a)AC | Peter Lanyon felt strongly that figuration and abstraction were not incompatible. |

| (18)AC | The simplicity of this format allowed Heron to concentrate on the play of colour against colour. |

One complication in the analysis of clause complements is presented by the existence of alternative constructions with it:

(16b)

It was a real challenge to take a line from top to bottom and keep it alive.

(17b)

It was felt that figuration and abstraction were not incompatible.

(19a) They decided to hold an exhibition with substantial prizes.

(19b)AC

It was eventually decided to hold an exhibition with substantial prizes.

Such cases are open to a number of analyses: Aarts and Aarts (1988: 148) argue that in such sentences "the function subject is realized by the discontinuous constituent it + finite/non-finite clause" and refer to the it as an "anticipatory it". Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik (CGEL 18.31), however, describe this phenomeon as extraposition and argue that the "resulting sentences ... contains two subjects, which we may identify as the POSTPONED SUBJECT (the one which is notionally the subject of the sentence) and the ANTICIPATORY SUBJECT (it)." Huddleston (1984: 67-8), on the other hand, considers it and not the thatclause to be the subject of such sentences.34

Within a valency account it is perhaps of no great importance which of these analyses one favours since the postponed clause need not receive any further classification apart from that of complement. However, it is important to realize that a decision as to whether the it and the postponed clause are to be seen as two separate constituents or as one discontinuous constituent affects the quantitative valency attributed to the respective verb. In a two-constituent analysis, the verb be would be divalent in (16a), but trivalent in (16b). Similarly, decide would have to be regarded as a divalent verb in (19a) but as trivalent in

(19c)AC It was decided by them to hold an exhibition with substantial prizes.

which would attribute a different quantitative valency to active and passive sentences. Similarly, the examples given by Aarts and Aarts (1988: 157)

(20a)QE

I resented it that John was late.

(21a)QE

They would regard itas a mistake if you left.

would have to be seen as tri- and tetravalent uses of resent and regard to contrast with di- and trivalent uses of these verbs in

(20b)

I resented John's being late.

(21b)

They would regard leaving as a mistake.

For this reason35, but also since the occurrence of the anticipatory it is always dependent on the occurrence of the corresponding clause and since the corresponding question forms have only one constituent

(16c)

What was a real challenge?

(19d)

What was decided?

the analysis suggested by Aarts and Aarts as a discontinuous realisation of one complement (i.e. as a discontinuous complement36) seems more attractive.37

What is more difficult to resolve is the fact that in some cases extraposition is optional and in others obligatory, as Aarts and Aarts (1988: 148) point out.

(22a)QE

It would seem that he has been wrong all the time.

(22b)QE

*That he has been wrong all the time would seem.

(23a)

They say that one function of art is to make the familiar seem strange.

(23b)

It is said that one function of art is to make the familiar seem strange.

(23c)

*That one function of art is to make the familiar seem strange is said.

Whether this is a sufficient reason to distinguish between different complement classes - one where extraposition is an alternative and one where it is obligatory - is arguable, however. CGEL (18.33) points out that - with the exception of ing-clauses - extraposition "is more usual than the canonical position before the verb". The occurrence of such clauses in subject position (without extraposition) seems to be strongly dependent on the theme/rheme-structure of the sentence and on the presence of sufficient end-weight. Since sentences such as

| (23d) | That one function of art is to make the familiar seem strange is said by many. |

| (23e) | That one function of art is to make the familiar seem strange is often said. |

are acceptable, it is clear that the realisation of the one-constituent alternative is subject to strong contextual constraints. It seems debatable, however, whether factors such as the theme/rheme structure will suffice to rule out cases such as (22b).

3.5.2 Finite clause complements

On the basis of these considerations, the following clause complements can be identified:

| (i) that-clauses | ||

| [that-CL]a | That we really need a dictionary to find our way around the labyrinthine complexities of Jorge Luis Borges, this strange and lonely prospector in the gallery of words, seems to me moot.CC

It appears that few people have bothered to vote. DC |

[that-CL]a cannot occur in passive clauses |

| [that-CL]p | It was felt that figuration and abstraction were not incompatible. AC

The US says it will ask that the Security Council meet in special session next Thursday. DC We've arranged that I'll call and collect them after dinner. DC | |

| [that-CL]o | The real worry is that the whole system is breaking down. DC | |

|

(ii) that-clauses with optional that | ||

| [(that)-CL]p | Peter Lanyon felt strongly that figuration and abstraction were not incompatible. AC

It was estimated last night that the leadership's position would be endorsed by a mere 2,000 or so votes. CC | |

| [(that)-CL]o | He persuaded her that she'd learn seamanship a lot faster if she sailed with him. DC | |

|

(iii) wh-clauses | ||

| [wh-CL]a | It is not certain when this will happen. DC | |

| [wh-CL]p | And what we say influences how we feel. CC

How good the results are is influenced by when the seedlings, seeds or bulbs are actually planted. CC | |

| [wh-CL]o | Political Economy may instruct us how a nation may become rich. DC | |

|

(iv) as if-, as though-, like-clauses | ||

| [as if-CL]a

[as though-CL]a [like-CL]a |

It does seem as if, at least nominally, Berlin will be the capital city. DC

It seemed as though the black clouds in the students' spirits had finally been lifted. DC It doesn't seem like we are going to be very happy. DC |

extraposition obligatory |

| [as if-CL]o

[as though-CL]o [like-CL]o |

The two rooms were relatively small and discretely lit, making the pictures seem as if they were hanging in the private rooms for which they had been intended. DC

One of the ... candidates ... seems as though he would be quite happy not to win. DC | |

3.5.3

Non-finite clause complements

3.5.3.1 Di- and trivalent constructions

With non-finite clauses a distinction has to be made between clauses containing a subject and those without a subject. In some cases, this can result in structural homonymy between

| (a) | divalent patterns with a non-finite clause containing a subject - symbolized as [NP X-CL]38such as |

(24a)DC

I can't see him running the risk of taking on an uninsured worker.

| or (b) | trivalent patterns with a [NP]-complement followed by a non-finite clause without a subject [X-CL] as in |

Where such complements can occur as subjects of passive sentences, the subject can be analysed as a discontinuous complement because the subject-NP of the complement clause becomes the subject of the main clause, whereas the remaining clause follows the verb of the main clause.39

(24b)AC Artists were again to be seen painting on the foreshore.

Thus the following specification can be provided:

| [NP X-CL]a/o | a non-finite clause complement containing a noun phrase (in objective case) as its subject

: |

| [NP X-CL]p | a non-finite clause complement containing a noun phrase (in objective case) as its subject, which, if occurring as the subject of a passive clause, is realized as a discontinuous complement with the noun phrase (in subjective case) in subject position and the remaining clause following the verb of the predicate |

3.5.3.2 Types of infinitival complementation

In the case of infinitival complementation, the following complement types will be distinguished:

| [to-INF-CL]a/p/o | a complement that takes the form of a to-infinitive clause | |

| (26)AC | Artists began to come regularly to the fishing villages of Newlyn and St. Ives. |

| [INF-CL]a | a complement that takes the form of an infinitive clause without to

: |

| [INF/to-INF-CL]o | a complement that takes the form of an

|

(27a)DC

You made them laugh.

(27b)DC

Parents must be made to feel more responsible.

Accordingly, a distinction between [NP to-INF-CL], [NP INF-CL] and [NP INF/to-INF-CL] must be made.

3.5.3.3 Clause complements without subject

Clause complements without subjects occur in the following types:

| (i) to-infinitive clause complements | ||

| [to INF-CL]a | To vote was to gamble. CC

Would it shock readers to know that this magazine receives far more press information from Audax? DC | |

| [to INF-CL]p | They decided to hold an exhibition with substantial prizes.

It was eventually decided to hold an exhibition with substantial prizes. AC | |

| [to INF-CL]o | Artists began to come regularly to the fishing villages of Newlyn and St. Ives. AC

This would certainly seem to be the case. DC | |

| :

(ii) Infinitives without to | ||

| [INF-CL]a | Turn off the tap was all I did. CC | restricted to certain types of pseudocleft sentence (CGEL 15.15): |

| INF/to-INF-CL]o | I made them amend the bill. DC

You can help save the lives of dolphins. DC Parents must be made to feel more responsible. DC | |

| :

(iii) V-ing-clauses | ||

| [V-ing-CL]a | Finding Trewyn Studio was a sort of magic. AC | |

| [V-ing-CL]p | Conforming to a system was considered emasculating and unnatural by men who had learnt their football with their friends in the streets and public parks. CC | |

| [V-ing-CL]o | Her father, county surveyor to the West Riding, often took her motoring with him across the Yorkshire Dales. AC

I can't bear being shouted at.DC | |

| :

(iv) wh-to-infinitives | ||

| [wh to-INF]a | But just how to proceed is unclear. CC

It would still be unclear how to evaluate the degree of support given to those neighbouring theories. DC | |

| [wh to-INF]p | The two of us have discussed how to tell him. DC

Let me explain how to do it. DC | |

| [wh to-INF]o | All you need to know is how to place your bet. DC | |

3.5.3.4 Non-finite clauses with subject

The following clause complements with subject can be identified:

| : | ||

| [NP V-ing-CL]a | Buses always being late annoys me. NON-CORPUS EXAMPLE | |

| [NP V-ing-CL]p | Don't let them catch you doing something wrong if you can possibly help it. CC

Bulldozers were seen felling trees in the project zone. CC | |

| [NP V-ing-CL]o | We don't want them coming here. CC | |

| : | ||

| [NP INF-CL]o | Today you can watch the catch come in at Hayle, St. Ives, Newlyn and Mousehole. DC | |

| : | ||

| [for NP to-INF-CL]a | For him to remain in Derbyshire seemed highly unlikely in midsummer. CC | |

| [for NP to-INF-CL]o | Please arrange for him to write the whole paper one week in the style of a bitter and hateful old man.CC

The scheme allowed for pensions to be calculated on the best twenty years of earnings. DC |

|

| : | ||

| [NP to-INF-CL]o | They demanded more planes to be made available. DC | |

| : | ||

| [NP V-ed-CL]o | I passionately want Labour elected next time. DC

If you want them shut, do it yourselves. CC | |

| : | ||

| [NP ADJ-CL]p | I wouldn't have believed it possible. DC | |

| [NP ADJ-CL]o | She wondered whether he would not prefer her dead. DC | |

| : | ||

| [NP ADV-CL]p41 | I want him in my team. CC | |

| [NP ADV-CL]o | He had thought she wished him there for Alan's sake. DC | |

3.5.3.5 Alternative analyses

As was indicated in 3.5.3.2, some of the complex complements identified above coincide at the surface with trivalent constructions. While

(28a)DC What do you want me to do?

is superficially the same as

| (29a)DC | This concession might persuade General de Gaulle to adopt a more friendly attitude towards European integration. |

| (30a)DC | She promised Beryl to keep an eye on him. |

the question criterion elicits the difference:

(28b)

What do you want?

(29b)

*What did it persuade?

(30b)

*What did she promise? - Beryl to keep an eye on him?

The type of analysis presented coincides with that of CGEL (16.20), where want is seen as an example of monotransitive

complementation. On the other hand, cases such as

(31a)QE

I heard someone shouting.

(24b)AC

Artists were again to be seen painting on the foreshore.

are analysed as complex transitive in CGEL (16.20/43), which is characterized by the fact "that the two elements following the verb (eg object and object complement) are notionally equated with the subject and predication respectively of a nominal clause". The reason given for this analysis is the passive, "where the O is separated from its complement". Jespersen (1914: 10), on the other hand, includes these among the "complex objects".42 If one permits discontinuous complements - as CGEL 18.39 does in the case of the only slightly different case of

| (32)QE | A rumour circulated widely that he was secretly engaged to the Marchioness. |

- then this does not argue against a divalent analysis of cases such as (24b) or (31a), especially since the corresponding question forms would be

(24c)

What was to be seen?

(31b)

What did you hear?

On the basis of the same considerations, complex complements of the type [NP ADV] can be identified to account for

(33a)DC

I didn't want him around.

(33b)CC

I want her in my team.

(33c)

What did I want?

Nevertheless it cannot be denied that there is a certain amount of gradience in the analysis of individual examples in this area. For instance

| (34)AC | In most of his work, John Park describes St. Ives welcoming the summer visitor. |

can be seen as a complex predicate or as a noun phrase with an ing-clause postmodifier, depending on how one interprets the semantic structure of the complement. Classificatory problems and borderline cases deserve much more detailed discussion; at this stage it is only important to identify complement classes as such.

3.6 Prepositional

complementation

3.6.1 Types of prepositional complement

Prepositional phrases occur as complements in sentences such as43

(35a)AC

In his letters he continuously refers to the 'wet sands'.

(36a)AC

They belonged to a new generation who had studied in Europe.

A distinction has to be made between prepositional complements such the wet sands in (35a), which can also function as the subject of a passive sentence, and those which cannot, such as the to-phrase in (36a):

(35b)

The wet sands were continually referred to in his letters.

(36b)

*A new generation was belonged to.

Such complements will be indicated in the following form: to-NPp and to-NPo; in general discussion P will be used for any preposition:

| [P NP]p | a prepositional complement that consists of a preposition and a noun phrase, which can function as the (discontinuous) subject of a passive sentence (the preposition remaining after the verb).

: |

| [P NP]o | a prepositional complement that consists of a preposition and a noun phrase, which cannot function as the subject of a passive sentence. |

The specification of the noun phrase element is necessary since prepositional complements can also take a different form:

| [P V-ing] | a prepositional complement that consists of a preposition and an ing-clause |

(37)AC

He obviously delighted in being a few doors along from Wallis.

| [P NP V-ing] | a prepositional complement that consists of a preposition and a non-finite clause consisting of a noun phrase and an ing-form |

(38)DC

My colleague and I both agree about Winter's Tale having fertility in it.

| [P wh-CL] | a prepositional complement that consists of a preposition and a wh-clause |

(39)DC

They would spend an hour trying to agree about which film they would go to.

| [P wh to-INF] | a prepositional complement that consists of a preposition and a wh-to-infinitive |

| (40)DC | The two houses of the United States Congress are continuing their efforts to agree about how to cut the federal budget deficit. |

These classes will then have to be indexed according to whether the nonprepositional constituent can function as a subject in a passive sentence or not. The following types occur:

| : | |

| [P NP]p | In his letters he continuously refers to the 'wet sands'. AC

Bernard Leach was looked upon with considerable suspicion by many townspeople AC |

| [P NP]o | They belonged to a new generation who had studied in Europe. AC |

| : | |

| [P V-ing]p | I object to being treated as a stupid peasant. |

| [P V-ing]o | He still maintains his links with teaching and has an appointment soon to speak to 500 country kids on preparing for exams. DC |

| : | |

| [P N-V-ing]p | You forgot about young James coming at Christmas. DC |

| [P N-V-ing]o | We believe in clubs developing their own players. DC |

| : | |

| [P wh-CL]p | They failed to agree on whether such elections should be held before or after unification.

DC

We forgot about how good they were.DC |

| [P wh-CL]o | The skill of politicians consisted in how clever they hid this elementary truth and gained votes by pretending the contrary. DC |

| : | |

| [P wh to-INF-CL]p | Senior staff were asked to comment on how best to handle a withdrawal. DC |

| [P wh to-INF-CL]o | You might find it interesting to inquire about how your children get on when you are not there. DC

The two houses of the United States Congress are continuing their efforts to agree about how to cut the federal budget deficit. DC |

3.6.2 Alternative analysis: prepositional verbs

One feature common to all approaches within the valency model is that they identify a prepositional complement class. Emons (1974: 122) takes it as the defining criterion for his commutation class E3. Since he also includes non-prepositional elements if they commute with prepositional elements, Emons's E3 does not fully coincide with the complement class [P NP] as established above. The distinction between [P NP]p and [P NP]o, however, corresponds to Allerton's (1982) between prepositional objects and prepositional objoids, but it should be noted that Allerton does not consider clause type complements.

However, the identification of a separate class or classes of prepositional complements distinguishes valency theory fundamentally from approaches which consider the preposition to form a lexical unit with the preceding verb. CGEL (16.3-8) or Aarts/Aarts (1988) use the term prepositional verb for such combinations.

There are two arguments in favour of this analysis44: Firstly, as is reflected in the definition of [P NP]p, the subject of a passive sentence is not formed by the prepositional phrase but only by a constituent of it, the preposition retaining its position after the verb:

(35b) The wet sands were continually referred to in his letters.

Although for sentences such as (35b), the prepositional verb analysis may indeed provide a more elegant solution, this does not apply generally because both analyses will need to account for the shiftability of the preposition in questions:

(35c)

To what did he refer in his letters?

(35d)

What did he refer to in his letters?

Secondly, a preposition can open up a set of syntactic options which again have to be specified individually so that they could indeed be seen as the valency of that preposition in combination with the verb. Defining the combination of preposition and noun phrase or of preposition and wh-clause as complement classes can thus be seen as a kind of shortcut.

The most important argument in favour of the prepositional complement analysis is that prepositional complements can then be analysed as part of the overall valency of the predicator. This not only has the advantage of formal consistency in the paradigm and of not obscuring semantic relationships, it also means that the number of lexical items to be identified need not be increased unnecessarily. The following table contrasts the prepositional complement approach of valency theory and the prepositional verb approach of CGEL:45

| (41a) | the question | |||

| (41b) | against | the car | ||

| (41c) | in favour of | the bus | ||

| (41d) | They | decided | on | the bus |

| (41e) | on | taking the bus | ||

| (41f) | to take the bus | |||

| (41g) | that they would take the bus | |||

CGEL identifies one verb decide for (41a) as well as three prepositional verbs decide against, decide in favour of, decide on and four types of complement. Since there is no semantic justification for considering the prepositional verbs identified as lexical units in their own right (as there is in the case of idiomatic combinations), their meaning is no more than the sum of the meanings of decide and the respective preposition.

The valency analysis, in contrast, only identifies one lexical unit decide in these examples and six different complement classes, which, however, are recurrent and can thus be taken as the basis of a generalizable semantic description in terms of the semantic roles expressed by different prepositional complements. Such parallels between prepositional complement classes are left unaccounted for in the prepositional verb approach.

In fact, it is difficult to see how CGEL would classify (41f) and (41g). Sentences such as

(42a)QE

They agreed (that) they would meet.

(42b)QE

They agreed to meet each other.

are analyzed in CGEL (16.28) as containing the prepositional verb agree on, where "the preposition disappears, and the prepositional object merges with the direct object of the monotransitive pattern." This is justified by the fact that the "preposition omitted before a that-clause can reappear in the corresponding passive" as in

(42c)CC

That they should meet was agreed on.

(42d)CC

It was agreed (on) eventually that they should meet.

Apart from the fact that this does not apply to the toinfinitive, it is difficult to see how in this model, monotransitive uses such as (41a) or

(42e)DC A deal was never agreed.

should be accommodated. Furthermore, (42a) could equally be seen as a form of agree about:

(42f) (?) That they should meet was agreed about.

Finally, such an analysis can be ruled out on the basis that comparable passive sentences also exist in cases where no corresponding active form can be found:

(43a)

(?) That they did not turn up will have to be accounted for.

(43b)

*They accounted that they did not turn up.

Furthermore, other verbs, probably the majority of those listed in CGEL (16.28), which do have that-clause complementation do not have a corresponding prepositional passive:

(44a)DC

Many will object that policies of this kind are prohibitively expensive.

(44b)

*That policies of this kind are prohibitively expensive is objected to.

Thus, prepositional passives with a that-clause subject will have to be part of a valency description in any case so there is no need to assume the preposition is deleted in the active. A further argument against the prepositional verb approach is presented by trivalent constructions such as

(45a)

He invested his money in property.

(45b)

He invested in property.

(45c)

He invested his money.

(45d)

He invested.

In a valency approach these four constructions are described in terms of a verb invest with different NP and PNP-complements. In CGEL (16.7), (45a) is analysed as containing a "prepositional verb type II", (45b) a "prepositional verb type I", and (45c) presumably as containing a monotransitive verb. Apart from the fact that the notion of a multi-word verb into which the direct object is inserted may not be particularly convincing, strictly speaking, such an approach must also see cases of correspondence such as

(10a)

Pour me a drink.

(10b)

Pour a drink for me.

as belonging to two different verbs - pour and pour for. From a valency perspective, the failure to recognize a complement class of verbs containing prepositions reveals a number of serious inadequacies in these approaches.

3.7 The category [ADV]

All complement classes established so far can be regarded as formal categories since they are defined in terms of a particular type of phrase or clause. There seem to be advantages in not following this approach consistently in the light of certain types of adverbial illustrated by the following examples:

| (46a)AC | The steep streets leading down to the harbour were a scene of continuous activity. |

| (46b)AC | This lead into a grantive-paved yard. |

| (46c)AC | Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth pursued independent yet parallel paths in a development that led towards total abstraction. |

| (47a)AC | Wood remained in and around Donarnenez until midSeptember. |

Although these examples contain prepositional phrases which no doubt have complement status they differ from the class of prepositional complements in that the choice of preposition is quite clearly not dependent on the governing words. Furthermore, prepositional phrases of this kind can be replaced by one-word adverbs:

(46d) The streets leading there were a scene of continuous activity.

(47b) Wood remained there.

Often, an adverbial wh-clause is also possible in such cases:

(47c) Wood remained where he was.

Thus, it seems convenient to introduce a complement class adverbial [ADV], which allows for a wide range of formal realizations:

| [ADV] | a complement which can take the form of either

|

Although [ADV] often coincides with the functional category adverbial, it should be seen as a shortcut for [ADV: AdvP/PP/wh-CL], i.e. a complement class representing various formal realizations and, as such, as a formal category. In cases where not all possible realizations of [ADV] can occur, more detailed specifications will have to be provided (of the type [ADV: AdvP] for an adverb phrase or [ADV: PP] for a prepositional phrase where the choice of preposition is not dependent on the governing word):

(48)DC A noodle will cut easily.

Adverbials can occur as subjects of pseudo-cleft sentences and as [ADV]o :

(i) [ADV]a

| (49a)QE | Here would be too noisy. |

| (49b)QE | Within two miles of the airport would be too noisy. |

| (49c)AC | Here was a studio, a yard and garden where I could work in open air and space. |

(ii) [ADV]o

(47a)AC Wood remained in and around Donarnenez until midSeptember.

The restrictions on the formal realizations of these adverbials are the same as the ones determining the occurrence of adjuncts, and, in fact, this complement class shows remarkable parallels with adjuncts with respect to the tests used to establish the distinction between complements and adjuncts. In the above examples, it is the obligatory character of the elements which clearly marks them as obligatory complements. However, it must be said that this is precisely the area where the distinction between complements and adjuncts is particularly difficult to draw if elements are optional.

3.8 Complement types [Quote] and [Sentence]

3.8.1 [Quote]

A similar problem regarding the complement status of an element is presented by a category which, following Sinclair (1990: 7.14), will be termed [Quote]. As with the category [ADV] the formal realizations of [Quote] can vary: