Scottish literature has been suffering up to the present time from prejudices allocating it to a Romanticism dating back to the 18th century that links it inevitably and almost exclusively to the names of Sir Walter Scott and Robert Burns. Nevertheless, in this century alone, this country has produced famous poets such as Hugh MacDiarmid and Edwin Muir. Their international standing has, however, adversely affected due recognition for more recent poets - with a few exceptions such as Alasdair Gray or Douglas Dunn, who have managed to become well known in Germany. The present state of Scottish poetry is characterised by its abundance of themes including politics, feminism and regionalism and of language with Scottish, English and Gaelic poetry. There is a lack of awareness of this diversity both abroad and unfortunately even in England as is the Scot's experience time and time again. It is typical for this situation that a poet such as Norman MacCaig should have received very little international attention despite the fact that he has received numerous awards, the latent being the most coveted poetry prize in England, the 'Queen's Gold Medal for Poetry'.

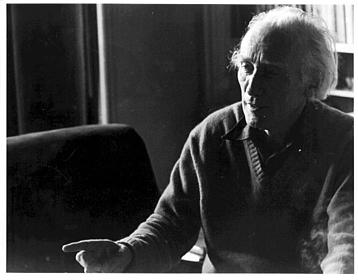

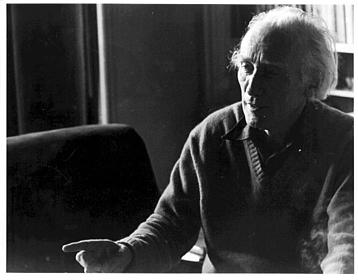

MacCaig could be described as the 'éminence grise' in today's Scottish literary scene; he had taken part in the discussions with a serious commitment to literature and poetry that took place in 'Milne's Bar' in the fifties; he knew all the main post-war poets and refers to himself as a representative of the older generation and even now, he always has a pithy comment to make. His verbal wit has often inspired fear in many an interviewer and is a reason why MacCaig's poetry readings were extremely popular events which were enjoyed not only by academics but also by school children. In the meantime his works have become a compulsory part of the literature syllabus in Scottish schools and universities. This popularity

Norman MacCaig, son of a chemist, was born in 1910 in Edinburgh where he still lives. On account of his Gaelic origins he feels himself to be Celt which is the basis for his love of a former Celtic area in the North West of Scotland called Assynt where he has been spending the summer months for over forty years. There are numerous references to Assynt in his poems. MacCaig read Classics at the University of Edinburgh from 1928 to 1932. His Gaelic origins and classical education have had a decisice influence on his work, as he once said in the following interview:

From 1934 to 1970 MacCaig worked as a secondary modern teacher and he taught at Sterling University as a "Writer in Residence" from 1970 to 1977 and also at Edinburgh University from 1977 to 1979. So not without a touch of irony, MacCaig describes himself: "I tell people I'm a retired schoolteacher" (The Scotsman, 3 July 1989). His Edinburgh flat still continues to be a meeting place for his circle of friends one of whom is the Irish poet Seamus Heaney.

Both in his life and in his work, Norman MacCaig distinguishes himself by his modesty which detests great gestures and words and which, on the contrary, loves whatever is inconspicuous. Although most of his poems mow more than six hundred in total deal with universal themes such as life and death, nature and man, they are placed in everyday situations. In his short poems MacCaig manages to capture a unique moment with a swift brush-stroke. He then stretches this moment of time in the most precise way possible in harmony with his principle of honesty both towards himself and others. In this way, the

This apparently modest demand which almost sounds naive contains the whole spectrum of MacCaig's scepticism that is expressed in questions: What can I see? How cxan I be true to an object I can only perceive from my own subjective point of view? Isn't my seeing already a new creation? In this way, the poem "Ego" leads the observer to the insoluble dilemma between the object and the self:

His first books of poems Far Cry (1943) and The Inward Eye (1946) fit in general into the literary movement called the New Apocalypse which was active during and after the second world war as a reaction to the rationalising poetry of the Auden generation. It tried to find new directions by shaping the unconscious mind (D.H. Lawrence's "Apocalypse", 1931) and by using surrealist forms. MacCaig's early poems are characterised by an excess of metaphors in rhyming stanzas. Themes such as nature, love, death, and time as well as a metaphysical questioning of reality appear in the poetry volumes. Later MacCaig distanced himself in no uncertain terms from these works which he did not include in his Collected Poems. After a nine-year long break from publication (MacCaig: "the long haul towards lucidity", ib.) the poet presents himself in Riding Lights (1955) with a controlled, precise style which was characteristic of all his later works. Succinct, terse poems convey in a clear form and with an apt use of metaphor the consciously experienced moment and the dilemma arising from subjective perception and the desire to be true to the uniqueness of what has been perceived and experienced. If an attempt can be made to find a pattern in his work of the last decades, then three phases can be distinguished with regard to the central theme of perception.

In the first phase which includes Riding Lights (1955), The Sinai Sort (1957), A Common Grace (1960), A Round of Applause (1962) and Measures (1965), the subjectivity of perception is the main theme within a complex thought process. Strict metrical control, well-structured verses and end rhymes provide the framework for the abstract content. Many of the poems make the transition from the visual object of the poem to the observer whose own perspective

Surroundings (1966) marks the beginning of the second phase, Rings on A Tree (1968), A Man in My Position (1969), Selected Poems (1971) to The White Bird (1973) also belong to this period. The poems of this phase display a new, critical dialectic in the processes of perception and presentation. The strict form breaks down to become flexible, free verse in which syntactic phrases and repetition determine the rhythm. The need for greater metrical flexibility and freedom is reflected in MacCaig's choice of new locations (New York and Italy). The poetic self is in a state of critical contention with its surroundings often represented by being addressed in the second person ("No wizard, no witch"). It sometimes expresses a clear criticism as in the inhuman behaviour of the tourists in "Assisi". The poems lament the inability of language to capture the essence of a person or thing ("No choice") as well as the subjectivity which arises of necessity from the naming of things in language ("No Nominalist"). In addition to abstract philosophising and the portrayal of concrete things or animals, real people belonging to MacCaig's circle of acquaintance are also described ("Aunt Julia"). The poems of the phase are characterised by their revolutionary, critical and rebellious spirit. This seems like a rebellion against the subjective limitations of human perception.

The third phase extends from The World's Room (1974), Tree of Strings (1977), The Equal Skies (1980) to Voice Over (1988). These poems contain personal experiences which now

MacCaig's basic principle of honesty towards oneself and others, controlled feelings expressed in a clear form and his commitment to everyday experience, are all reminiscent of Philip Larkin. In addition to John Donne MacCaig mentions the American poet Wallace Stevens. He has in common with this poet the theme of the dialectic which links the inner world of thought and imagination to external reality although MacCaig never loses sight of the concrete and tangible aspects. His preference for precise expression in simple ordinary language to recreate concrete reality can be compared to the Imagists, particularly William Carlos Williams's attitude of solemn amazement towards real things. Distrustful of language and art and their potential and conscious of the basis inability to capture the external world in its uniqueness. MacCaig's work belongs to a general direction of post-war international poetry. His acceptance of the world of objects affirming yet distancing at the same time sets him clearly apart from the self-analysing confessional poets.

Now that MacCaig is over 80, he can look back at a life's work which avoids the grand gestures in his unaffected language but which dazzles both in its profundity and variety. His poems are characterised by his own unique style which, with its awareness of form, expresses personal attitudes as well as abstract thoughts about human perception in such a way that the reader is inspired to close onservation whether the subject be a sleepy farm in summer ("Summer farm") or the beggar in "Assisi". All that is now to be hoped for is that this work will receive the attention it deserves and will finally be made available to German readers - even in translation. Bibliography Works by MacCaig: (All places of publication: London)

Anette Degott

Institut für Anglistik/Amerikanistik

Jena