- Chapter I:

-

- Introduction

-

- In the aftermath of World War II the French colonial administration returned

to Indochina to resume control of French possessions. With it came units of

the French Army, among them mechanized and armored elements. These units remained

in Vietnam for more than ten years, until, in compliance with the Geneva Accords

of 1954, the last French soldier left the country in April 1956. The experience

of the French and their Vietnamese allies in those years had a strong influence

on concepts developed in the South Vietnamese Army for the employment of armored

forces. Their experience also influenced the thinking of American military

commanders and staffs when the U.S. Army eventually set about deciding how

many and what kinds of forces to send to Vietnam.

-

- Influence of French Use of Armor

-

- The U.S. Army in the early 1960's had very little information on the use

of armor in Vietnam, and most of that came from French battle reports and

the fact that the French Army had been supplied with World War II tanks, half-tracks,

and scout cars. Although most of this equipment was American, made originally

for the U.S. Army, there was little reliable information as to the amount,

condition, and use of it in Indochina. In 1954, after four years of American

aid, the French fleet of armored vehicles consisted of 452 tanks and tank

destroyers and 1,985 scout cars, halftracks, and amphibious vehicles, but

this armor was scattered over an area of 228,627 square miles. By comparison,

in June of 1969 the U.S. forces in Vietnam had some 600 tanks and 2,000 armored

vehicles of other types deployed over an area less than one-third that size.

-

- All the American equipment used by the French was produced before 1945.

In general the armor was not fit for cross-country movement and because of

its age was often inoperative. The logistical system, with supply delays of

six to twelve months, further hampered operations by making maintenance difficult.

Helicopters were not available in large numbers-there were ten in 1952, forty-two

in 1954; all were unarmed and were used for resupply and medical evacuation.

To the French command, impoverished in all resources, fighting with limited

equipment over a large area, the

- [3]

- M24 (CHAFFEE) AMERICAN LIGHT TANK USED BY FRENCH IN VIETNAM

-

- employment of armored forces became a perpetual headache. Armored units

were fragmented; many small remote posts had as few as two or three armored

vehicles. Such widespread dispersion prevented the collection or retention

of any armor reserves to support overworked infantry battalions. When French

armored units took to the field, they were roadbound. Roads prescribed the

axes of advance, and combat action was undertaken to defend a road and the

ground for a hundred meters or so on either side. The enemy was free to roam

the countryside. Since armored units were generally assigned to support dismounted

infantry, their speed and ability to act independently, an important part

of any armored unit's contribution to the battle team, were never used.

-

- All these facts were duly reported by the French in their candid, comprehensive,

and sometimes blunt after action reports. In the United States, because of

restrictive military security regulations and a general lack of interest in

the French operation in Indochina, there was no body of military knowledge

of Vietnam. What was known had been drawn not from after action reports but

from books written by civilians. Foremost among these was Bernard B. Fall's,

Street Without Joy, which greatly influenced the American military

attitude toward armored operations in Vietnam. One series of battles in particular

stood out from all the rest, epitomizing the French experience in American

eyes. Entitled "End of a

- [4]

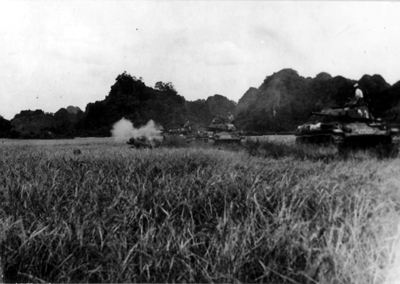

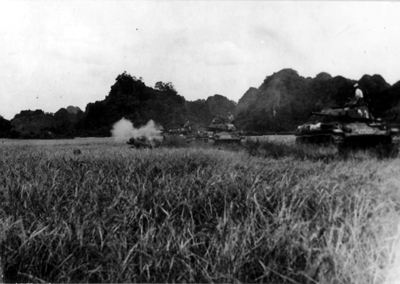

- TANKS FIRING IN SUPPORT OF FRENCH INFANTRY AT DIEN BEEN PHU

-

- Task Force," Chapter 9 of Fall's widely read book traced a six-month

period in the final struggles of a French mobile striking force, Groupement

Mobile 100. The vivid and terrifying story of this group's final days seemed

to many to describe the fate in store for any armored unit that tried to fight

insurgents in the jungles.

-

- Actually Groupement Mobile 100 was not an armored unit at all, but an infantry

task force of 2,600 men, organized into four truck-mounted infantry battalions,

reinforced with one artillery battalion and ten light tanks. Restricted to

movement on roads, deploying to fight on foot, it was extremely vulnerable

to ambush, and, indeed, a series of ambushes finally destroyed it. Because

most readers did not take the time to understand the organization and actions

of Groupement Mobile 100, its fate cast a pall over armored operations in

Vietnam for almost twelve years. The story of this disaster became a major

source for unfavorable references to French armored operations in Vietnam,

and contributed much to the growing myth of the impossibility of conducting

mounted combat in Vietnam.1

In fact, the myth was so widely

- [5]

- accepted that it tended to overshadow French successes as well as

some armored exploits of the Vietnamese Army, and it actually delayed development

of Vietnamese armored forces. Unfortunately, U.S. commanders were to repeat

many of the mistakes of the French when American armored units were employed.

-

- U.S. Armored Forces After 1945

-

- When World War II ended the United States Army had an armored force of sixteen

divisions and many other smaller armored units. The bulk of this force-the

divisions-included balanced, integrated, mobile fighting forces of armored

artillery, armored infantry, and tanks. Concepts for employment of these combined

arms forces recognized no limitations of geography or intensity of warfare.

The combined arms idea stressed tailoring integrated mobile forces to the

situation, taking stock of enemy, terrain, and mission. Mechanized

cavalry units were formed to supplement these forces by conducting reconnaissance

and providing security.

-

- The employment of U.S. armored divisions exclusively in Europe and Africa

during World War II caused many to conclude that only in those theaters was

warfare with armor possible. U.S. military studies of armor in the war were

based on accounts of combined arms warfare in Europe and North Africa. Most

American experience with armored units in the Pacific, and later in Korea

in the early 1950's, seemed to confirm the impression that armored units had

but limited usefulness in jungles and mountains. The Army staff therefore

concluded that while tanks for the support of dismounted infantry might be

required, there was no possibility for independent large-scale combined arms

action by armored forces such as those of the World War II armored divisions.

It was against this background that the U.S. Army grappled with decisions

on American troop deployments to Vietnam in the early 1960's. Combined with

the misconceptions of the French armored experience, this reasoning caused

most planners to conclude that Vietnam was no place for armor of any kind,

especially tanks.

-

- In the war in the Pacific there was slow, difficult fighting in island rain

forests. No armored division moved toward Japan across the Pacific islands.

Neither blitzkrieg tactics nor dashing armor leaders achieved literary fame

in jungle fighting. It was an infantry war; armored units were employed, but

what they learned was neither widely publicized nor often studied. To most

military men the jungle was a dark, forbidding place, to be avoided by armored

formations. Even after American military advisers began to replace

- [6]

- the French in the country, the very name, Vietnam, conjured up an image

of dense, tropical rain forests, rice paddies, and swamps.2

-

- To American military conceptions of jungle fighting, the Korean War added

some additional experience that weighed in the deliberations on troop deployments

to Vietnam. Korea has a monsoon climate, a seasonal change in the prevailing

wind direction, which is offshore in winter, onshore in summer. The deluge

of summer rains in Korea is a reality that no one who served there can forget.

The rains made mounted combat difficult, if not impossible. The extensive

flooded rice paddies in the western Korean lowlands were added obstacles to

the movement of armored vehicles during the rice-growing season. When it became

known that Vietnam was a country with a monsoon climate and a rice culture,

Americans who had been to Korea remembered the drowning summer rains that

made the countryside impossible to traverse for almost half a year. Actually

the Vietnam monsoons are quite different from those in Korea and do not impose

the same limitations on movement. Vietnam's rice culture is, moreover, confined

to a narrow belt of lowlands along the coast and the vast stretches of the

Mekong Delta.

-

- One-half of Vietnam is mountainous. Recalling the impassable mountains of

some of the Pacific islands and Korea, and the extreme difficulty that armored

vehicles had in operating in both places, many planners concluded that Vietnam's

mountains were probably at least as rugged as those of Korea and were covered

with jungle as thick as that of the Pacific islands. These assumptions were

taken as additional evidence that armored vehicles had no place in Vietnam.

-

- Yet another contribution to the growing body of notions that formed early

U.S. Army attitudes toward armored units in Vietnam was a singular lack of

doctrine for mounted combat in areas other than Europe and the deserts of

Africa. As late as November 1961, Field Manual 17-30, The Armored Division

Brigade, in a section on combat in difficult terrain, devoted one brief fourteen

line paragraph to combat in woods, swamps, and lake areas. Here it was stated

that armored units should bypass, neutralize by fire, or let infantry clear

difficult terrain. The basic armored tactical manual, Field Manual 17-1, Armor

Operation, Small Units, devoted but six skimpy paragraphs to jungle operations.

- [7]

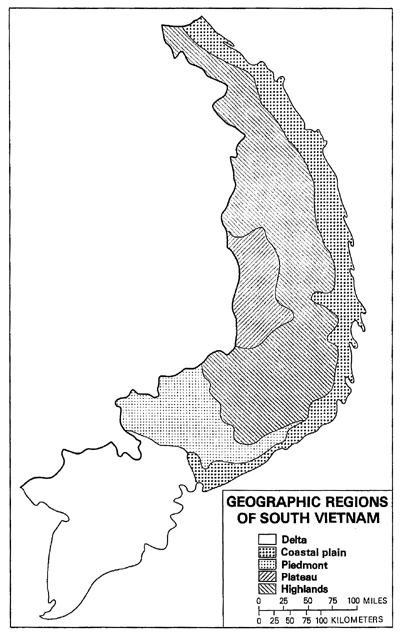

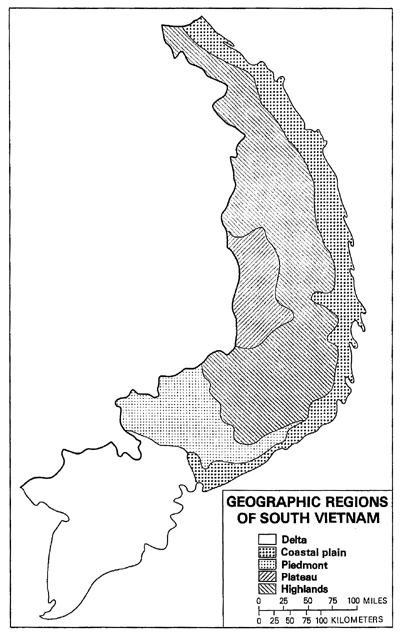

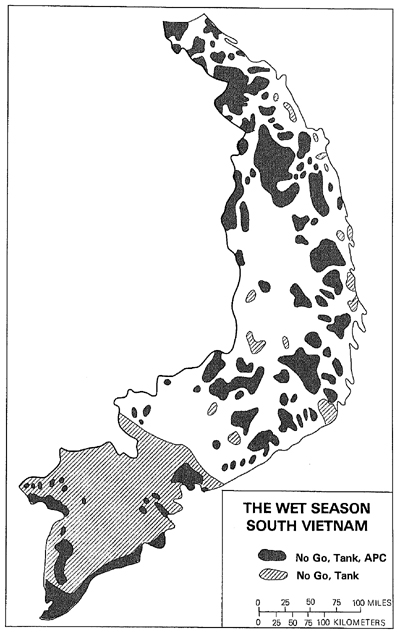

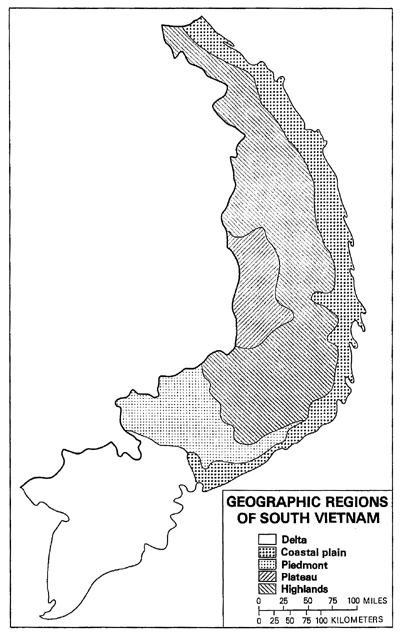

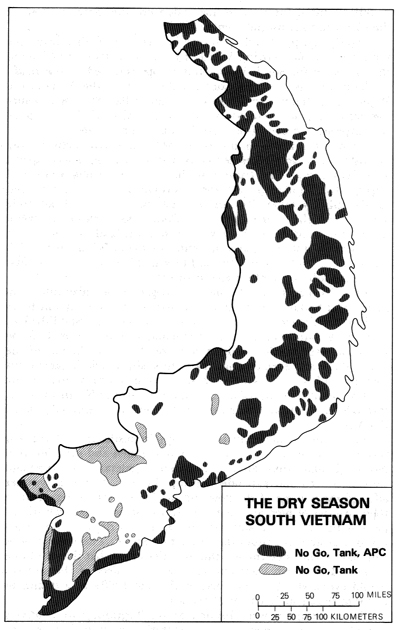

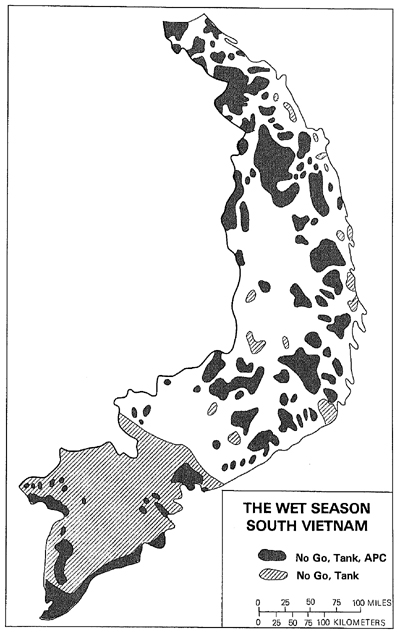

- MAP 1

[8]

- Vietnam as a Field for Armor

-

- In fact, Vietnam is not a land totally hostile to armored warfare. When

the terrain was examined in detail on the ground, as it was in 1967 by a team

of U.S. armor officers, it was found that over 46 percent of the country could

be traversed all year round by armored vehicles. During the Vietnam War operations

with armored units were conducted in every geographic area in Vietnam, the

most severe restrictions being experienced in the Mekong Delta and the central

highlands.

-

- The Mekong Delta, often below sea level and rarely more than four meters

above, is wet, fertile, and extensively cultivated. The area is so poorly

drained that the southern tip of the country, the Ca Mau Peninsula, is an

expanse of stagnant marshes and low-lying mangrove forests. Because the entire

delta is criss-crossed with streams, rivers, and canals, traffic was forced

to follow dikes, dams, and the few built-up roads.

-

- In contrast to the delta, the highlands are rugged small mountains of the

Annamite chain, with peaks rising to 2,600 meters. Heavily forested with tropical

evergreen and bamboo, they were a difficult but not impossible obstacle for

armored vehicles. Roads were poor and population centers small and scattered.

When first introduced into the highlands, armored units cleared roads and

escorted convoys. Subsequently, as larger enemy forces appeared, combined

arms task forces operated in the mountain and jungle strongholds. (Map

1)

-

- The other regions of South Vietnam-the coastal plain, piedmont, and plateau-are

characterized generally by rolling or hilly terrain. Vegetation ranges from

scrub growth along the coast to rice paddies, cultivated fields, and plantations

through the southern piedmont, with bamboo, coniferous forests, or jungle

in the northern piedmont and plateau. These areas could be used by armored

ground vehicles over 80 percent of the time and were traversed by French and

Vietnamese armored forces before the arrival of American troops.

-

- The weather in Vietnam is controlled by two seasonal wind flows-the summer,

or southwest, monsoon and the winter, or northeast, monsoon. The stronger

of these winds, the summer monsoon, blows from June through September out

of the Indian Ocean, causing the wet season in the delta, the piedmont, and

most of the western highlands and plateau. The remainder of the country has

its wet season from November to February during the winter monsoon, when onshore

winds from the northeast shed their moisture over the northern one-third of

South Vietnam.

- [9]

- During the transition between wet and dry periods and in the dry periods

themselves, mounted combat was feasible in most parts of Vietnam. Even in

the wet season, armored units proved able to operate with relative ease in

many areas previously considered impassable. In 1967 a study under the title

Mechanized and Armor Combat Operations, Vietnam (MACOV) was undertaken to

make an extensive evaluation of the effects of Vietnam's monsoon climate on

the movement of armored vehicles. Although Army engineers had conducted earlier

surveys, the engineers were found to be conservative in their estimates. When

there was doubt that armored units would be able to maneuver in certain places

these were marked impassable by the engineers, who apparently took care that

no commander would find his units stuck in an area that had been marked good

for land navigation.

-

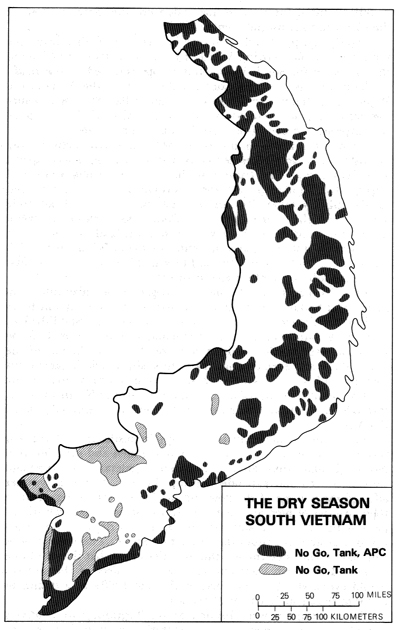

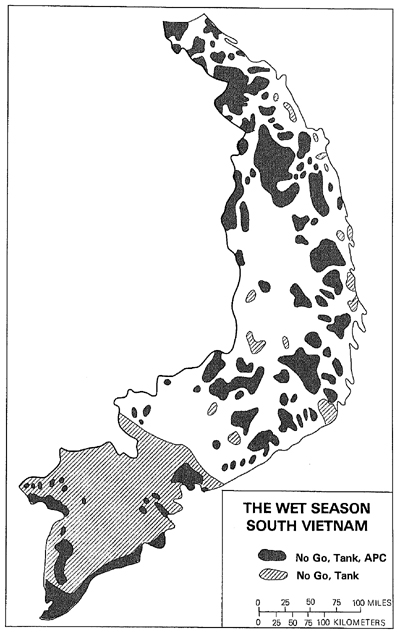

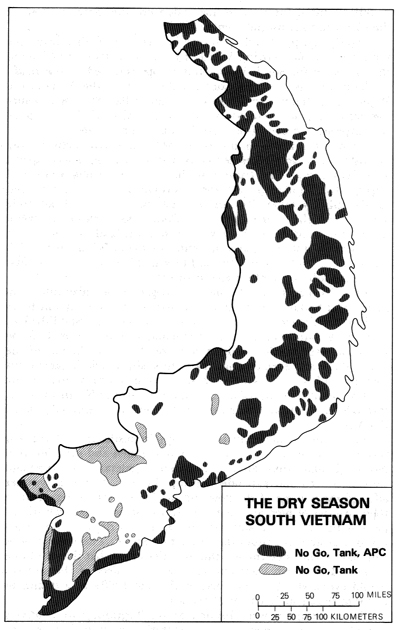

- The group conducting the study approached the matter positively; that is,

it indicated as feasible for operations any terrain where experience showed

tracked vehicles had gone and could go with organic support. Applying terrain

analysis data to the "go or no go" concept, the team produced maps

of Vietnam for both the dry and the wet seasons. (See Maps 2 and 3.) More

definitive and more optimistic than the engineers, the group determined that

tanks could move with organic support in 61 percent of the country during

the dry season and in 46 percent during the wet season. Armored personnel

carriers could move in 65 percent of Vietnam the year-round.

-

- The study confirmed what was already known to the Vietnamese: major portions

of Vietnam were suitable for armored operations. But this study was not completed

until almost two years after the arrival of the first Army ground combat units.

During those two years many of the units were sent to Vietnam without their

tanks and armored personnel carriers. Some units were even converted from

mechanized infantry to infantry before deployment. The earlier studies had

provided the overriding rationale for the decisions of 1965 and 1966.

-

- The Enemy in Vietnam

-

- By the late 1950's the insurgents in South Vietnam were known as Viet Cong,

a contraction of a term that meant Vietnamese Communists. Although the enemy's

methods of fighting and his ultimate goals had not really changed since the

campaigns against the French, neither Vietnamese nor U.S. military observers

recognized the fact. Enemy soldiers were variously described as bandits, rebels,

or political malcontents; closer study revealed that the enemy was

- [10]

- MAP 2

- [11]

- a well-organized force whose methods were the same as those of the Viet

Minh against the French.

- Lightly equipped and operating in a country with a primitive road network,

fast-moving Viet Cong forces on foot proved more than a match for South Vietnamese

troops confined to the roads. In the first stages, the Viet Cong avoided units

of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam and operated as guerrillas. Sabotage,

bombing, terrorism, and assassination were their hallmark. Speed, security,

surprise, and deception were keys to their success.

-

- There were many in the early 1960's who still believed the enemy was a loosely

organized body with no staying power against a modern army. The truth was

that the Viet Cong were well organized in regular (main) forces, provincial

(local) forces, and village military (guerrilla) forces. This organization

did not come about overnight; rather the Viet Cong passed through several

stages that were dictated by various military and administrative situations

in different parts of South Vietnam. Thus, many U.S. observers in Vietnam

and the military in general did not at first realize the full extent of the

enemy threat.

-

- After 1959 small Viet Cong units began to organize into companies and battalions;

guerrilla operations were a complementary tactic. Guerrilla strength grew,

and secret bases were established all over the Republic of Vietnam, particularly

in the lower Mekong Delta, the area north of Saigon, and the remote highlands

of the north. Raids and even occasional battalion-size attacks became more

frequent. These large-scale operations were centrally directed by the Lao

Dong, a branch of the Communist Party of North Vietnam, through the Central

Office for South Vietnam, commonly called COSVN.

-

- An important factor in the enemy's intensification of the war was the establishment

of routes for moving men and supplies from North Vietnam. Infiltration routes

were in operation by 1960 and were improved and expanded during the war. Monsoon

weather affected the volume of the flow and produced a pulsating effect in

these arteries of men and materiel. In dry seasons and transitional periods

between monsoons the flow increased dramatically, often up to four and five

times the ordinary volume. The regularity of this flow in turn determined

the intensity of combat that could be supported in South Vietnam. This seasonal

effect of the weather would eventually be recognized in the late 1960's as

a dominant factor in the enemy's scheme of operations.

-

- Enemy supplies were limited at the beginning to relatively unsophisticated

weapons and war material in limited quantities. Troops were usually former

residents of South Vietnam, indoctri-

- [12]

- MAP 3

- [13]

- nated by North Vietnam as replacements for Viet Cong units. As the supply

of South Vietnamese dwindled, North Vietnamese soldiers began to appear, first

as replacements in Viet Cong units, then as entire units of the North Vietnamese

Army. The appearance of whole units marked the transition to the last phase

of the war, which was a clash between modern armies, even though Viet Cong

guerrilla activities continued.

-

- Viet Cong and North Vietnamese battle tactics invariably followed a simple

formula, adopted originally from the Chinese combat doctrine of Mao Tse-tung:

When the enemy advances, withdraw; when he defends, harass; when he is tired,

attack; when he withdraws, pursue. To this formula was added a combat technique

of "one slow, four quick," practiced with meticulous precision in

almost every situation.

-

- The first step, one slow, meant prepare slowly; a thorough and deliberate

planning preceded any tactical operation. Each action was rehearsed until

every leader and individual was familiar with the terrain and his specific

job. Only when the commander was convinced that the rehearsal was perfect,

was the operation attempted.

-

- Execution was in four quick steps, the first of which was advance quickly.

The Viet Cong moved rapidly from a relatively secure area to the objective

and there moved immediately into the second step, assault quickly. In the

assault, they tried to insure surprise, pouring large volumes of fire on their

objective. They swiftly exploited success and pursued the enemy, killing or

capturing. The third step, clear the battlefield quickly, consisted of collecting

and carrying away all weapons, ammunition, and equipment, and destroying anything

that could not be carried off. The Viet Cong made every effort to evacuate

their wounded and dead. Finally, with orderly precision, the fourth step,

withdraw quickly, was taken. The troops moved over planned withdrawal routes,

with large units quickly breaking into small groups and losing themselves

in as large an area as possible. Later, the scattered groups reassembled in

a safe area.

-

- Perhaps the most unusual Viet Cong fighting technique was that of carrying

on a different kind of war in each of South Vietnam's forty-four provinces.

South Vietnamese defenders in the northern highlands were confronted with

enemy tactics that were in sharp contrast to those used in the broad southern

deltas. Even more unusual was the fact that the level of conflict in each

province varied surprisingly. Often one province would be simultaneously subjected

to large-scale mobile attacks and guerrilla harassment, while a neighboring

province was left entirely alone. This selective

- [14]

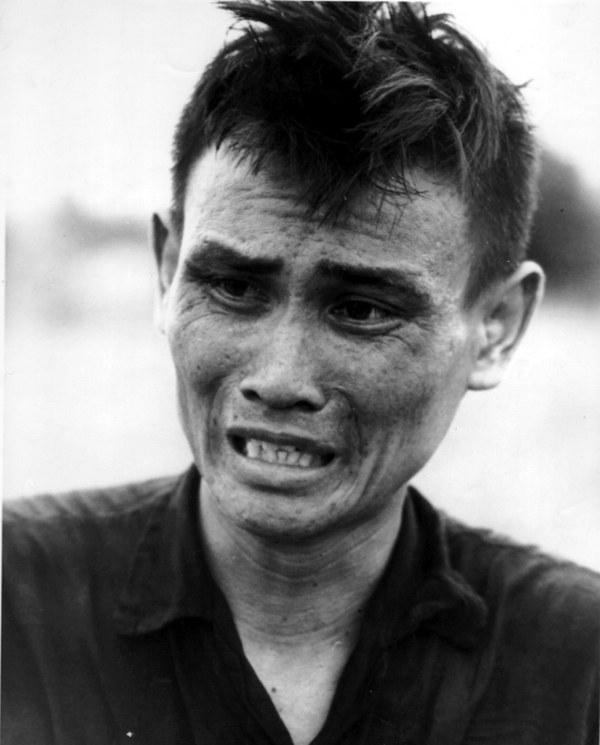

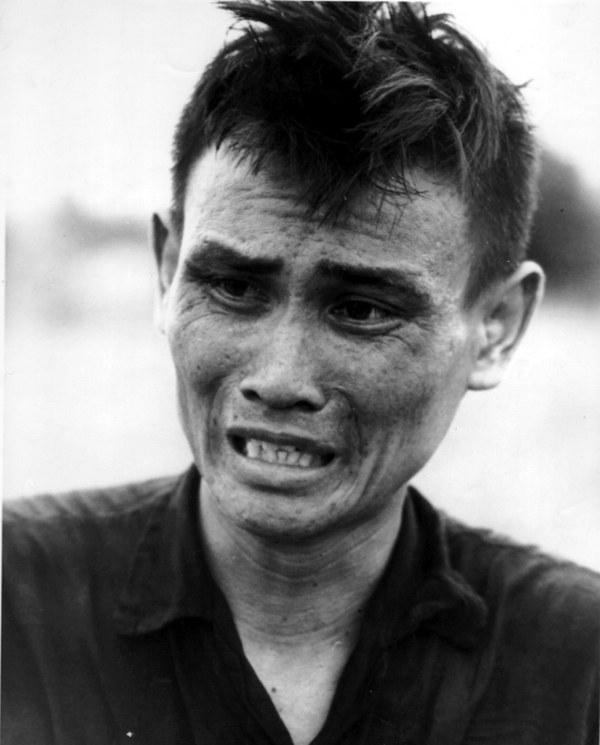

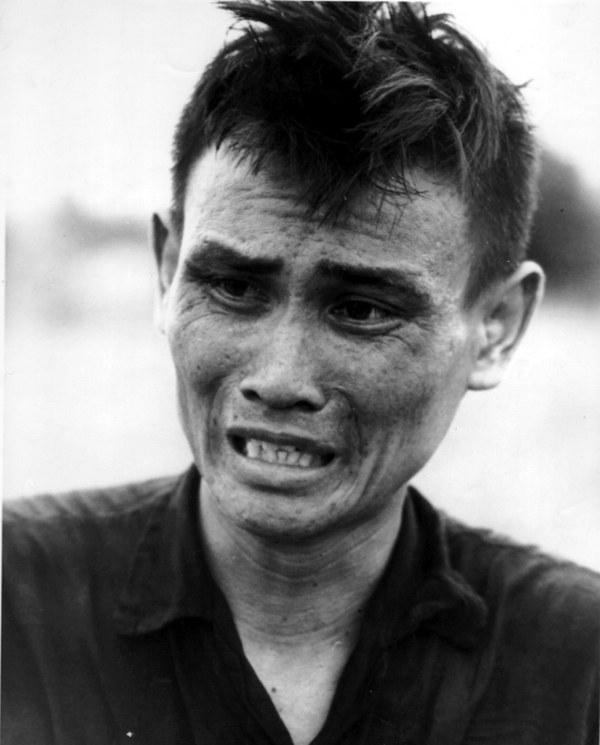

- VIET CONG SOLDIER

- [15]

- intensification of the war by the Viet Cong confused American observers,

and hid the true nature of the conflict. The American image of the enemy as

loosely organized groups of bandits or guerrillas was not real. The enemy

had a plan and worked his plan well, so well in fact that by 1964 he was ready

to make the transition to the last phase of the conflict, full-scale mobile

war.

- [16]

-

Endnotes

Next Chapter

-

- page created 17 January 2002

-

Return to the

Table of Contents

-