- Chapter III:

-

- Growth of U.S. Armored Forces

in Vietnam

-

- The American elections of 1960 brought John F. Kennedy to the White House

and Robert S. McNamara to the Pentagon. The change spelled the end of the

strategy of massive retaliation and of the pentomic division with its five

battle groups designed to fight nuclear wars. The Army reorganization of 1963

restored the infantry battalion and provided a structure for the whole Army

that, at battalion and brigade level, was much like the separate battalions

within the combat commands of U.S. armored divisions after World War II. It

was clear that the new policy of flexible response demanded a force that could

fight in any kind of war, including so called wars of national liberation.

-

- In armored units there was little change. The 1963 reorganization reduced

each tank and mechanized infantry battalion to three line companies, but each

division had more battalions and support echelons. No one in armor seriously

believed that armored unit tactics needed to change. In 1957 Field Manual

17-1, Armor Operations, Small Units, devoted only two and one-half pages to

guerrilla warfare. By the early 1960's that coverage had been broadened; Field

Manual 17-35, Armored Cavalry Platoon, Troop and Squadron, carried an expanded

treatment of guerrilla fighting under the title, Rear Area Security.

-

- Many of the tactics set forth in the manual for employing armored cavalry

in rear area security missions proved useful in Vietnam. Road security, base

defense, air reconnaissance, reaction forces, and convoy escort were described.

Field Manual 17-1 included discussions of base camps, airmobile forces, tailoring

of forces for specific missions, encirclements, and ambushes. Both books stressed

surveillance, the use of the combined arms team, and the need for mobility.

Yet most counterinsurgency training was limited to work on patrols, listening

posts, and convoy security; the Army did not foresee a whole theater of operations

without a front line or a secure rear area.

-

- Although the helicopter was not specifically designed for counterinsurgency

warfare, it proved to be one of the most useful machines the U.S. Army brought

to Vietnam. As early as 1954 the Army had studied the use of helicopters in

cavalry units, and later experiments with armed helicopters had been conducted

at the

- [50]

- U.S. Army Aviation School at Fort Rucker, Alabama. By early 1959 the U.S.

Armor School at Fort Knox, Kentucky, and the U.S. Army Aviation School had

developed an experimental Aerial Reconnaissance and Security Troop-the first

air cavalry unit. This aerial combined arms team, composed of scouts, weapons,

and infantry, was tested in 1960 and recommended for inclusion as an organic

troop in divisional cavalry squadrons. In early 1962 the Army's first air

cavalry troop, Troop D, 4th Squadron, 12th Cavalry, was organized at Fort

Carson, Colorado, with Captain Ralph Powell as its commander. The troop mission

was to extend the capabilities of the squadron in reconnaissance, security,

and surveillance by means of aircraft. Over the next three years all divisional

cavalry squadrons in the Army were provided with air cavalry troops.

-

- In mid-1962 Lieutenant General Hamilton H. Howze headed a study group to

examine the possibilities of the helicopter in land warfare. The group concluded

that helicopters organic to the ground forces were an inevitable step in land

warfare. The Howze Board foresaw air assaults, air cavalry operations, aerial

artillery support, and aerial supply lines, and recommended the creation of

an air assault division. The outcome of the study was the formation of the

11th Air Assault Division, later to become the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile)

. The division organization included one unique unit, an air cavalry squadron

made up of one ground troop and three air cavalry troops.

-

- By 1965 when the U.S. Army began to send units to Vietnam, divisional armored

cavalry squadrons had three ground cavalry troops and an air cavalry troop,

tank battalions had three identical tank companies, and mechanized infantry

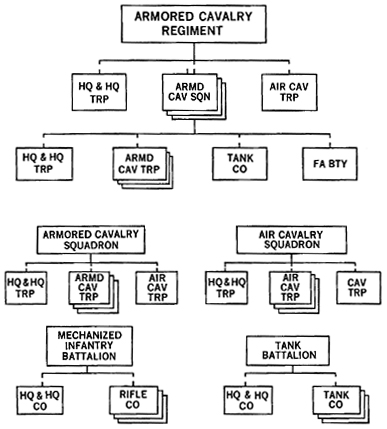

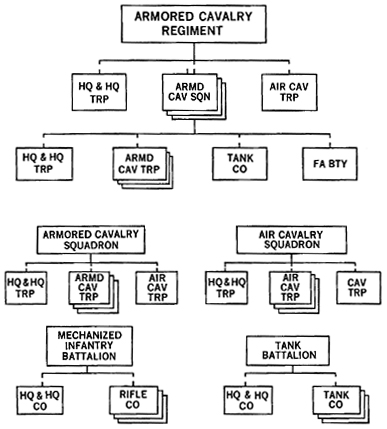

battalions had three mechanized companies mounted in APC's. (Chart 1)

Armored units were equipped with a mixture of M48 and M60 tanks, M 113 armored

personnel carriers, and M109 self-propelled 155-mm. howitzers.

-

- On the eve of the Army's major involvement in Vietnam, however, most armor

soldiers considered the Vietnam War an infantry and Special Forces fight;

they saw no place for armored units. The Armor Officer Advanced Course of

1964-1965 never formally discussed Vietnam, even when American troops were

being sent there. Armor officers were preoccupied with traditional concepts

of employment of armor on the fields of Europe; a few attempted to focus attention

on the use of armor in Vietnam, but in the main they were ignored. Many senior

armor officers who had spent years in Europe dismissed the Vietnam conflict

as a short, uninteresting interlude best fought with dismounted infantry.

- [51]

- CHART. U.S. ARMORED ORGANIZATIONS, 1965

-

- The Marines Land

-

- By early 1965 the American command in Vietnam had concluded that the South

Vietnamese could not hold off the combined Viet Cong and North Vietnamese

Army forces without U.S. assistance, and in February American forces began

a limited air and sea bombardment of North Vietnam and jet aircraft strikes

in South Vietnam. In late February General William C. Westmoreland, Commander,

U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, requested two U.S. Marine battalion

landing teams to assist South Vietnamese forces in making the airfield at

Da Nang secure.

-

- On 9 March 1965 Marine Corps Staff Sergeant John Downey

- [52]

-

U.S. MARINE CORPS FLAMETHROWER TANK IN ACTION NEAR DA

NANG. The U.S. Army no longer had flamethrower tanks but the Marine

Corps sent several to Vietnam.

-

- drove his M48A3 tank off a landing craft onto Red Beach 2 at Da Nang and

was followed by the rest of the 3d Platoon, Company B, 3d Marine Tank Battalion,

the first U.S. armored unit in Vietnam. Later in March the 1st Platoon, Company

A, 3d Marine Tank Battalion, landed with a second Marine team, and for the

remainder of the month these two platoons bolstered the defenses of the Da

Nang airfield.

-

- On 8 July 1965 the 3d Marine Tank Battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel

States R. Jones, Jr., debarked at Da Nang-the first U.S. tank battalion in

Vietnam. Consistent with U.S. Marine Corps concepts of tank employment, the

battalion's primary mission was to support Marine infantry. As Marine tactical

areas of responsibility expanded throughout 1965, so did the areas in which

tank units operated in support of infantry reaction forces, as support for

infantry strongpoints, or in sweep and clear operations.

-

- U.S. Marine Corps tank units took part in the first major battle involving

U.S. armored troops-Operation STARLITE. In mid-August

- [53]

- 1965 a large Viet Cong force believed to include the 1st Viet Cong Regiment

was reported to be preparing to attack the Chu Lai airfield, southeast of

Da Nang. To preempt the attack, a marine amphibious operation using helicopters

and three battalion teams was mounted. A tank platoon supported each battalion.

The operation lasted for two days, and was characterized by short, bitter

firefights as the Viet Cong attempted to evade encircling forces. When Operation

STARLITE ended, the marines had pushed the Viet Cong regiment against the

sea, killing over 700 men. In two days, seven tanks had been damaged by enemy

fire, three so badly that the turrets could not traverse, and one to the point

that it had to be destroyed by a demolition team. The Marine tank crews had

demolished many enemy fortifications, captured twenty-nine weapons, and killed

sixty-eight Viet Cong.

-

- Until their final withdrawal in late 1969, Marine Corps tanks continued

to support U.S. Marine Corps infantry units in Vietnam. During this time,

Marine armor, eventually two full battalions, participated in the battles

of Khe Sanh and Hue and was the main armor defense force of the Demilitarized

Zone in the north.

-

-

- When the decision to send American ground forces to Vietnam was finally

made after a long, involved debate at high governmental levels it was conditional.

Troops were released to Vietnam in increments, each designed to support one

of the three principal ground strategies that followed one another in rapid

succession. The cumulative effect of rapidly changing strategy and the absence

of a clearly stated long-term goal with a definite troop commitment can be

easily seen in retrospect, but in the hectic days and months of the first

half of 1965 there was no one who could predict the length of the war, enemy

intentions and capabilities, and the extent of future U.S. commitment. It

was in this atmosphere that General Westmoreland and his planners labored

to develop troop lists of units they wanted sent to Vietnam.

-

- During the first half of 1965 the three principal ground strategies were

described as security, enclave, and search and destroy. Of the first two,

neither required the use of large mobile forces nor implied that U.S. troops

would stay in Vietnam for any length of time. Under the security strategy

American marines were sent to Vietnam to defend an airfield and took their

tanks along. The planners in the U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam,

had not examined the makeup of a marine battalion landing team and therefore

did not realize that the team had tanks. The marines, for

- [54]

- their part, saw no reason to leave their tanks behind. That tanks were sent

to Vietnam was, therefore, a kind of accident, and a not altogether popular

one. For example, U.S. Ambassador Maxwell D. Taylor was surprised and displeased

to learn that the marines had landed with tanks and other heavy equipment

"not appropriate for counterinsurgency operations."

-

- The security strategy was defensive in intent and limited in scope. In neither

it nor its successor, the so-called enclave strategy, was the use of armored

forces planned. The troops sent to carry out both strategies-the Marines,

the U.S. Army 1734 Airborne Brigade, and an Australian infantry battalion-were

therefore dismounted infantry elements whose stay in Vietnam was considered

temporary. In fact, the airborne troops were sent to Vietnam on temporary

duty. Force planners, trying to get all the combat troops on the ground they

could and still stay within the limited troop ceilings and the very restricted

capacity of the logistical base, chose infantry units that were easily deployed

and required only minimal support.

-

- The third strategy, search and destroy, began to evolve during June and

July of 1965. After receiving the authority to use U.S. ground forces anywhere

in Vietnam in search and destroy operations, General Westmoreland tried to

determine the forces that would be necessary to defeat the enemy. Throughout

1965 he personally studied every unit on the troop lists to insure the best

use of the authorizations, the earliest possible troop deployments, and the

most appropriate apportionment of troops among the armed services. Within

Army manpower authorizations, he also sought an effective distribution among

branches. The MACV staff continuously reevaluated the situation to determine

whether there was a need for additional troops. Because of the troop ceilings-the

first three troop increments were only 20,000 each, with no promise of more-the

severely limited logistical base, and the many misconceptions about the country,

armored units were not seriously considered for early employment in Vietnam.

-

- The first debate on the use of armored units arose during planning for the

deployment of the 1st Infantry Division. Directives from the Department of

the Army required reorganization of the division to eliminate the units designed

for nuclear war, the division's two tank battalions, and all the mechanized

infantry. The mechanized infantry units were to be organized into dismounted

infantry battalions. The rationale for these decisions was provided by the

Chief of Staff of the Army, General Harold K. Johnson, in a message on 3 July

1965 to General Westmoreland. Overruling an Army staff proposal that one tank

battalion be retained, General Johnson gave some of his reasons.

- [55]

- A. Korean experience demonstrated the ability of the oriental to employ

relatively primitive but extremely effective box mines that defy detection.

Effectiveness was especially good in areas where bottlenecks occurred on some

routes. Our tanks had a limited usefulness, although there are good examples

of extremely profitable use. On balance, in Vietnam the vulnerability to mines

and the absence of major combat formations in prepared positions where the

location is accessible lead me to the position that an infantry battalion

will be more useful to you than a tank battalion, at this stage.

-

- B. I have seen few reports on the use of the light tanks available to the

Vietnamese and draw the inference that commanders are not crying for their

attachment for specific operations.

-

- C. Distances and planned areas of employment of the 1st Division are such

that the rapid movement of troops could be slowed to the rate of movement

of the tanks.

-

- D. The presence of tank formations tends to create a psychological atmosphere

of conventional combat, as well as recalls the image of French tactics in

the same area in 1953 and 1954.

-

- General Johnson went on to say that the divisional cavalry, the 1st Squadron,

4th Cavalry, would be allowed to keep its medium tanks, M48A3's, to test the

effectiveness of armor. If circumstances required it later, General Johnson

was prepared to reinforce the division with a tank battalion. In his answer

to this message General Westmoreland declared that "except for a few

coastal areas, most notably in the I Corps area, Vietnam is no place for either

tank or mechanized infantry units."

-

- These two messages clearly show the prevailing attitude among American senior

officers toward the use of armored forces in Vietnam, and reflect the influence

of the French experience with armor. At the staff level, the commanders' misconceptions

were magnified by problems of force structure; troop ceilings and the limited

logistical base became further justification for rejecting armored units.

For example, when it was noted that a mechanized battalion required more than

900 troops and a dismounted infantry battalion only about 800, dismounted

infantry became the choice. Further, the mechanized battalion also needed

a direct maintenance support unit of over 150 troops and a security force

to guard its base. Although a tank battalion required but 570 men, its detractors

were quick to say that only 220 of these were fighters-the rest were support

troops. To support the tank battalion in combat still more maintenance and

security troops would be needed. This line of reasoning made the tank battalion

an unattractive package. One force planner in the Military Assistance Command,

Vietnam, commented that while no one was outspokenly prejudiced against the

use of armored forces in Vietnam there was no strong voice calling for their

employment.

- [56]

- The experience of the 1st Infantry Division illustrates some of the problems

faced by the commanders of armor units earmarked for Vietnam. Having lost

his tank and mechanized infantry units, Major General Jonathan O. Seaman,

the 1st Division commander, wanted to make sure that his one remaining armored

unit, the 1st Squadron, 4th Cavalry, was properly equipped. General Seaman,

noting the poor performance of the M114 reconnaissance vehicle in Vietnam,

recommended substituting M 113's for the squadron's M 114's. After considerable

resistance from the Army staff in Washington the exchange was finally approved.

The M113's, modified with additional machine guns and gunshields, came from

the pool of vehicles taken from the recently dismounted mechanized battalions.

Obtaining trained people was another matter. Some months before when General

Seaman had been told that only one of his brigades would go to Vietnam, he

had filled the deploying brigade with experienced officers and men from other

division units, including the 4th Cavalry. Subsequently the remainder of the

division was ordered to Vietnam. Filled with new officers and troops the cavalry

had time for only two weeks of unit training before it left.

-

- When the first armor units reached Vietnam their tactical employment was

equally frustrating for the squadron and battalion commanders; again the experience

of the 1st Squadron, 4th Cavalry, is illustrative. The brigades of the 1st

Division, each with a cavalry troop attached, were sent to three different

locations. The squadron headquarters was left with only the air cavalry troop

under its control. The first operation at squadron level took place in early

1966, over six months after the unit reached Vietnam. Cavalry tactics during

those first six months suffered from the "no tanks in the jungle"

attitude. Because General Westmoreland saw no use for tanks, the M48A3's were

withdrawn from the cavalry troops and held at the squadron base at Phu Loi.

It took six months for General Seaman and Lieutenant Colonel Paul A. Fisher,

the squadron commander, to convince General Westmoreland that tanks could

be properly employed on combat operations. Although the tank crews subsequently

proved themselves in combat, General Seaman's repeated requests for one of

his tank battalions that had been left at Fort Riley were refused. The same

fate befell similar requests by his successor throughout 1966.

-

- The air cavalry troop was also fragmented. Before the unit was sent to Vietnam

it was organized like an armed helicopter company: a troop of two platoons,

equipped with command and control helicopters and gunships. Training was based

on experience with

- [57]

- armed helicopters in Vietnam. Once in Vietnam, however, helicopters were

parceled out to the units that wanted them, and the aerorifle platoon was

attached to Troop C for use as long-range patrols and base camp security guards.

The troop continued to operate in this makeshift fashion for over a year until

the example of other air cavalry units brought about a change in organization

and tactics.

-

- As the political and military power of the enemy continued to grow during

1965, General Westmoreland and his planners were convinced that the United

States would have to provide additional troops if the government of South

Vietnam was to survive. When the evolving strategy required additional American

forces, the President of the United States increased manpower authorizations,

and eventually more armored units were sent to Vietnam. In late 1965 General

Westmoreland requested deployment of the 11th Armored Cavalry and the 25th

Infantry Division. Included in the latter were the 3d Squadron, 4th Cavalry,

the 1st Battalion, 5th Infantry (Mechanized) , and the 1st Battalion, 69th

Armor. Major General Frederick C. Weyand, the 25th Division commander, insisted

on deploying the armor battalion despite resistance from staff planners in

both Department of the Army and Vietnam.

-

- Scouts Out

-

- In the U.S. cavalry of the late 1800's, the familiar call at the beginning

of a campaign was "scouts out"; so it was, too, in Vietnam, in 1965.

Earlier some ground cavalry units had been used in Vietnam, but in September

the first air cavalry unit, the 1st Squadron, 9th Cavalry (Air) , arrived

with the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile). While a brigade of the 101st Airborne

Division maintained security in the An Khe camp area, the air cavalry troopers,

together with the airmobile infantrymen of the division's traditional "cavalry"

battalions, were allowed a few days to move into and secure an area for building

a division base.1

By 18 September enough aircraft were available for the squadron to begin aerial

reconnaissance of the division base area.

-

- In late October 1965 reports of increasing enemy strength in the central

plateau brought commitment of the entire 1st Cavalry Division to an offensive

in western Pleiku Province. The 1st Squad-

- [58]

- ron, 9th Cavalry (Air) , the "eyes and ears" of the division,

was given the mission of finding the enemy as well as covering divisional

troop movements. Few enemy troops were spotted from the air at first but by

30 October the number of sightings began to increase. Troop C captured three

North Vietnamese soldiers, the first divisional unit to capture North Vietnamese

Army troops. On 1 November 1965 Troop B's scouts sighted and fired on eight

North Vietnamese soldiers. Shortly thereafter about forty more were spotted

and the troop's aerorifle platoon, already airborne, was landed to investigate.

For once the enemy stood and fought; the American platoon killed five of the

enemy and captured nineteen others. The troopers found the reason for the

enemy concentration when they moved into a nearby stream bed and discovered

a hospital. Fighting around the hospital continued while the captured soldiers,

medical equipment, and supplies, all part of the 33d North Vietnamese Army

Regimental Hospital, were evacuated. Late in the afternoon the 2d Battalion,

12th Cavalry (Airmobile) landed as reinforcements, and the 9th Cavalry aerorifle

platoon was withdrawn.

-

- Knowing that the enemy was in the area in strength, the 1st Squadron, 9th

Cavalry (Air), with Company A, 1st Battalion, 8th Cavalry (Airmobile), moved

to the Duc Co Special Forces Camp and by evening on 3 November 1965 had begun

a reconnaissance in force along the Cambodian border. The squadron ambush

force, consisting of three American aerorifle platoons, an attached Vietnamese

platoon, and a mortar section of Company A, 1st Battalion, 8th Cavalry, reconnoitered

and established three ambush sites. In the early evening the southernmost

ambush, manned by Troop C's aerorifle platoon, sighted a large, heavily laden

North Vietnamese Army company. The enemy soldiers, easily seen by the light

of the full moon, were laughing and talking and obviously felt secure in that

part of the jungle. The waiting cavalrymen detonated eight claymore mines

set along a 100-meter kill zone, and the troopers joined in with their M16

rifles as additional claymores and rifle fire from the flank security elements

sealed off the area. The firing lasted two minutes, and when there was no

answering fire from the enemy the aerorifle platoon returned to the patrol

base.

-

- One ambush platoon was still in position at 2200 when the three platoons

in the base were assaulted by an estimated enemy battalion. The first attack

was costly to the North Vietnamese, who withdrew. Enemy snipers remained in

the nearby trees, and, aided by bright moonlight, attempted to pick off the

defenders. With the help of the reinforcements from Company A, 1st Battalion,

8th

- [59]

- Cavalry, the Americans defeated another enemy attack just before daylight.

The defenders then made limited counterattacks to expand the perimeter and

provide a safer landing for the rest of the battalion. By dawn the enemy began

to break away, incoming fire slackened, and there was only occasional sniper

fire from the surrounding trees. The air cavalry platoons were then extracted,

leaving the 8th Cavalry to sweep the battlefield.

-

- For the second time in a week air cavalry soldiers had successfully battled

the enemy, later identified as the 66th North Vietnamese Army Regiment, recently

arrived in South Vietnam. These combat actions and the scouting activities

of the entire squadron supplied information on enemy locations that brought

major elements of the 1st Cavalry Division into action for almost a month

in the Ia Drang valley. The first stage of the Ia Drang campaign, which was

also the first major battle for an air cavalry squadron, showed how the air

cavalry should be used. For those commanders who employed it properly, the

air cavalry in Vietnam was a primary source for gathering intelligence information.

-

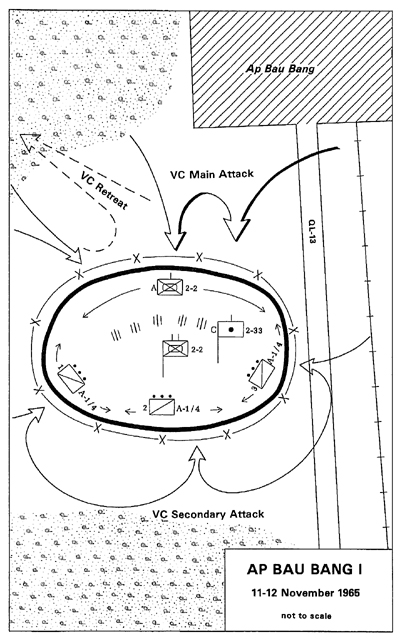

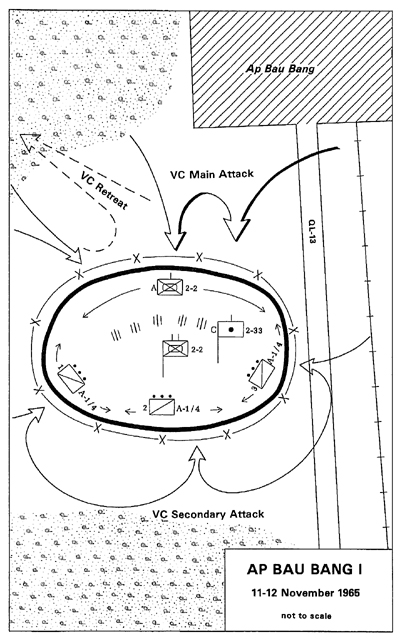

- Ap Bau Bang

-

- As the 1st Squadron, 9th Cavalry, was triggering the Ia Drang campaign,

far to the south Troop A, 1st Squadron, 4th Cavalry, participated in the first

major engagement of the 1st Infantry Division. The battle at Ap Bau Bang was

an early example of a combined arms defense of a night position. The action

was important because it occurred during the initial stages of U.S. troop

involvement and demonstrated the effectiveness of combined arms in jungle

warfare.

-

- A task force of the 2d Battalion, 2d Infantry, consisting of the battalion's

three rifle companies, its reconnaissance platoon, and Troop A (less the nine

tanks still at Phu Loi), was ordered to sweep and secure Highway 13 from the

fire base at Lai Khe to Bau Long Pond, fifteen kilometers north. The purpose

of Operation ROADRUNNER was to secure safe passage for a South Vietnamese

infantry regiment and provide security for Battery C, 2d Battalion, 33d Artillery,

which was moving north to support the South Vietnamese regiment. On 10 and

11 November 1965 the road was cleared without incident; medical teams even

visited the village of Bau Bang as part of a medical civic action program.

-

- During the afternoon of 11 November, Troop A, the artillery battery, the

command group, and Company A of the infantry battalion moved into a defensive

position south of Bau Bang. (Map 5) Concertina wire was installed,

individual foxholes were dug, and

- [60]

- MAP 5

- [61]

- patrols were setup for ambushes. Dragging the hull of a destroyed armored

personnel carrier around the perimeter, Troop A knocked down bushes and young

rubber trees to clear fields of fire. The night passed with only a light enemy

probe, but within minutes after the early dawn stand-to (a term applied

by armored units to first-light readiness of men, vehicles, and radios) fifty

to sixty mortar rounds exploded inside the perimeter. In the first few minutes

Troop A had two men wounded. Half an hour later a violent hail of automatic

weapons and small arms fire was added to the mortar fire. Under cover of this

fire, the Viet Cong moved to within forty meters of the defensive positions.

While the cavalrymen returned the fire, M113's of the 3d Platoon roared out

and assaulted the enemy. The violence of this unexpected mounted counterattack

disrupted the Viet Cong attack, and the M113's returned to the perimeter.

The troop suffered three more wounded and one killed when ammunition in a

mortar carrier exploded after being hit by enemy mortar fire.

-

- The Viet Cong made their second assault from the jungle and rubber trees

south of the perimeter. Again supported by mortars and automatic weapons,

they crawled through the waist-high bushes of a peanut field and rushed the

concertina wire. One of the M113's in that section of the perimeter was driven

by Specialist 4 William D. Burnett, a mechanic. When the .50-caliber machine

gun on his APC failed to function, Specialist Burnett jumped from the cover

of the driver's compartment to the top of the vehicle, cleared the weapon,

and opened fire on the charging Viet Cong, killing fourteen. For this and

other actions during the battle, Specialist Burnett was awarded the Distinguished

Service Cross. The heavy fire from Burnett's machine gun and those of the

M113's near him broke the enemy assault.

-

- The Viet Cong next attacked west from Highway 13, and again were repulsed

by .50-caliber and small arms fire. Several times M113's were moved to weak

points on the perimeter so that their machine guns could fire into the enemy's

ranks at point-blank range. At 0645 an air strike directed by an airborne

forward air controller dropped bombs and raked the wooded area north of the

task force with 20-mm. cannon fire.

-

- At 0700 the Viet Cong began their main charge from the north out of Bau

Bang, supported by recoilless rifles and automatic weapons emplaced along

an east-west berm on the southern edge of the village and mortars in the village

itself. The main attack was stopped at the wire by the combined firepower

of Company A and Battery C, which in thirty minutes, using two-second delay

fuzes,

- [62]

- fired fifty-five rounds point-blank at the attackers. Despite this wall

of steel, one Viet Cong squad penetrated the perimeter and threw a grenade

into a howitzer position, killing two artillerymen and wounding four others.

Three infantry companies were meanwhile ordered by the 1st Infantry Division

to move toward the battle and to envelop the Viet Cong from the rear. At the

same time, armed helicopters flew to the scene.

-

- The enemy attacked again at 0900, this time from the northwest, with recoilless

rifles, automatic weapons, and mortars. Protected by the berm, these weapons

could not be destroyed by direct artillery fire. When an Air Force pilot reported

that the villagers were fleeing to the north of Bau Bang, and another pilot

sighted the mortar positions within Bau Bang, permission was obtained to hit

the village. Fighter planes bombed the enemy positions and armed helicopters

discharged rockets and strafed. For the next three hours, while mortars, artillery,

and air strikes hammered the enemy, the task force repelled successive attacks.

-

- The battle of Ap Bau Bang went on for more than six hours before the enemy

withdrew to the northwest, leaving behind his wounded and dead. Troop A, commanded

by Second Lieutenant John Garcia, suffered seven killed and thirty-five wounded;

two M 113's and three M 106 mortar carriers were destroyed and three M 113's

were damaged. Procedures and techniques learned in training had been proven

in battle. The clearing of fields of fire and the pre-dawn stand-to had insured

the full application of Troop A's fire-power. The 3d Platoon's foray into

the enemy position and the positioning of M113's on the perimeter had demonstrated

the unit's flexibility, and artillery and aerial fire support had provided

depth to the defense. The enemy had begun the fight; the combined arms team

had ended it.

-

- Deployments and Employments

-

- The 1st Squadron, 4th Cavalry, had made the case for armored forces. Upon

the recommendations of General Seaman and others, armored units of the 25th

Infantry Division were sent to Vietnam in early 1966. Before leaving, the

1st Battalion, 5th Infantry (Mechanized), had equipped its APC's with gunshields

and extra machine guns and the 1st Battalion, 69th Armor, had exchanged its

gasoline-powered M48A2C tanks for diesel-powered M48A3's. For these units

and others to follow, South Vietnamese Armor Command advisers had prepared

a packet that included information on the terrain, suggestions for modifications

to equipment, a description of enemy weapons and tactics, and suggested countermeasures

- [63]

- to the tactics. Such special South Vietnamese Army equipment as the M113

capstan recovery device was also described and detailed illustrations and

explanations of South Vietnamese modifications to the M113, notably gunshields

for the machine guns, were included.

-

- Within three weeks after their arrival, the three armored units of the 25th

Division participated in the first multibattalion armor operation to take

place in Vietnam. Operation CIRCLE PINES was carried out in the jungle and

rubber plantations twenty kilometers north of Saigon, where heavy growth favored

the concealment of Viet Cong base camps. In places soft marshy soil impeded

tank movement, but generally vegetation did not appreciably restrict either

tanks or armored personnel carriers. By the close of this eight-day operation,

more than fifty of the enemy had been killed and large amounts of arms and

supplies had been captured. Of more importance was the fact that a large armored

force had successfully invaded a Viet Cong jungle stronghold, forcing the

enemy to move his base camps. The myth that armor could not be used in the

jungle had been destroyed, and for that alone CIRCLE PINES will remain significant.

-

- During April and May the 1st Battalion, 5th Infantry (Mechanized) , continued

operations around the Cu Chi region, returning to enemy bases in the Filhol

Plantation and the Boi Loi and Ho Bo Woods. When conducting search and destroy

operations in the base areas, mechanized infantry usually fought mounted,

using the personnel carriers as assault vehicles. In the heavily wooded terrain

the vehicles moved in column formation, breaking paths through the trees and

thick brush and permitting the infantrymen to remain mounted and avoid booby

traps. When the infantry located the Viet Cong the vehicles were moved rapidly

toward enemy positions, with all guns firing in an attempt to overrun the

enemy before the troops dismounted to make a thorough search. Using these

techniques, in two months the battalion found and destroyed three base areas,

killed 130 of the enemy, and captured thirty-six weapons.

-

- In early June the 1st Battalion, 5th Infantry (Mechanized) , began Operation

MAKII, the first test of U.S. mechanized infantry's ability to operate in

III Corps Tactical Zone during the wet season. This maneuver took the unit

back into the Bao Trai-Duc Hoa area where it had fought in Operation HONOLULU

in March, when the rice paddies were hard and the canals dry. The plan called

for an immediate and rapid sweep of the respective company zones with the

object of finding and destroying all enemy forces. To gain as

- [64]

- much surprise as possible, Lieutenant Colonel Thomas U. Greer, the battalion

commander, had the unit leave the base camp at Cu Chi just early enough to

reach the line of departure by H-hour, which was 1100 on 3 June.

-

- As the battalion reconnaissance platoon entered the zone of operation, it

spotted and killed two Viet Cong soldiers. When the M113's churned over the

dikes, more Viet Cong came out of the water where they were attempting to

hide by submerging and breathing through hollow reeds. In a short time twelve

of the enemy had been killed and nineteen captured. For the next three days

the battalion searched the area, occasionally encountering a few Viet Cong

soldiers. On 8 June, acting on information from prisoners, Company C discovered

the second largest arms cache of the war to date-116 weapons and two tons

of ammunition. The battalion learned from this operation that M113's could

move through paddies covered with more than a foot of water but could not

navigate damp, muddy paddies that had no standing water. The conclusion drawn

from the maneuver was that most of the division area was suitable for mechanized

operations, even during the rainy season.

-

- Task Force Spur

-

- Armored units arriving early in the Vietnam War literally had to invent

tactics and techniques, and then convince the Army that they worked. While

there was basic doctrine upon which to improvise, for Vietnam it needed expansion,

modification, and, in some cases, combat testing. Not all innovations came

from experienced armor leaders. Frequently, improvisation was necessitated

by the tactical situation, but more often it came from the imagination of

soldiers.

-

- Several general officers advocated more armor. General Jonathan O. Seaman

as commander of the 1st Division, and later as commander of II Field Force,

constantly recommended the deployment of more armored units. Brigadier General

Ellis W. Williamson asked for armor to support his 173d Airborne Brigade when

the tanks of the 1st Squadron, 4th Cavalry, were being held at Phu Loi. General

Fred C. Weyand, commander of the 25th Division, insisted on deploying armored

units with his division. Brigadier General William E. DePuy, who as MACV J-3

was convinced that armored units could not be used, later changed his mind

and as commander of the 1st Division constantly employed his armored units

to seek out the enemy.

-

- Not all early users of armor were generals. In early April 1966 Colonel

Harold G. Moore, Jr., commander of the 3d Brigade, 1st

- [65]

- Cavalry Division (Airmobile), found a role for armored forces in the II

Corps Tactical Zone near Chu Pong Mountain, twenty-seven kilometers west of

Plei Me. The division was conducting Operation LINCOLN, and infantry units

requested heavy artillery-175-mm. and 8-inch-to provide close support. The

mission was given to Colonel Moore, who decided to move self-propelled artillery,

escorted by Troop C, 3d Squadron, 4th Cavalry, through twenty kilometers of

jungle where no roads existed. The armored column was to be guided and protected

by elements of the 1st Squadron, 9th Cavalry (Air) .

-

- On 3 April Task Force SPUR, with nine M48A3 tanks, seventeen M113's, and

the self-propelled artillery, struck out boldly from Plei Me into the jungle

to the west. Tanks of the 3d Squadron, 4th Cavalry, guided by scouts of the

1st Squadron, 9th Cavalry, picked their way toward the planned artillery site

with M113's, artillery, and cargo trucks following in their path. Task Force

SPUR went through the twenty kilometers of jungle in seven hours, and for

the next two days conducted search operations in the valley. When no Viet

Cong were found, the armored unit returned to the artillery position to escort

the guns back to Plei Me. The cavalrymen had covered over 108 kilometers of

trackless jungle with the aid of air cavalry, demonstrating a far greater

capacity for cross-country movement in the II Corps area than anyone had thought

possible.

-

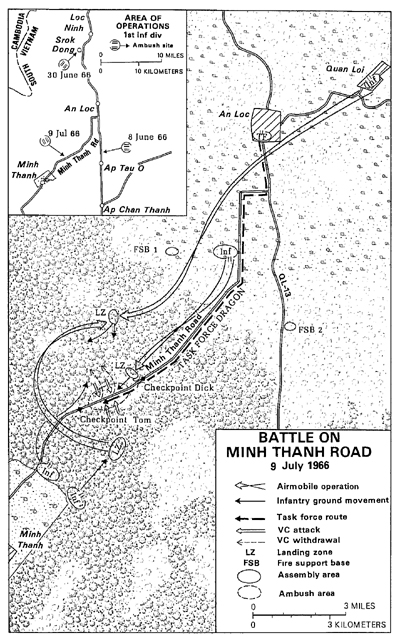

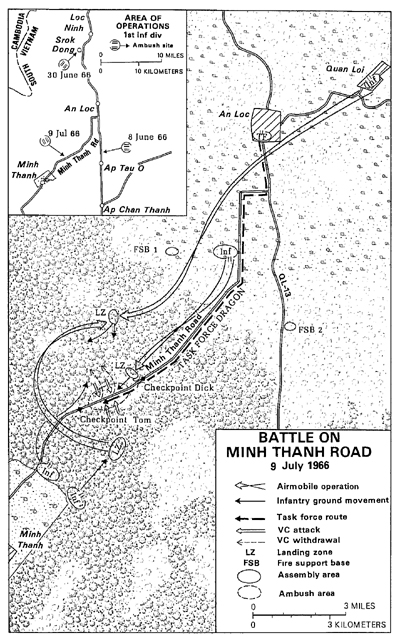

- Battles on the Minh Thanh Road

-

- In armored battles the mobility and heavy firepower of armored units often

compensated for tactical mistakes. Some battles were extremely close, and

caused changes to be made in operational procedures. One of these occurred

in the III Corps Tactical Zone in 1966 as the 1st Infantry Division, probing

into War Zone C, triggered a series of engagements on a dirt track called

the Minh Thanh Road.

-

- Operating with South Vietnamese forces, the U.S. 1st Infantry Division mounted

a series of operations in eastern War Zone C during June and July 1966. The

purpose was to open Route 13 from Saigon to Loc Ninh in Binh Long Province

and to destroy elements of the 9th Viet Cong Division. The 9th was reported

to be massing to seize the province capital of An Loc and several district

capitals. By the end of Operation EL Paso II in early September 1966, five

major engagements had been fought, and all three regiments of the 9th Viet

Cong Division had withdrawn into sanctuaries deep in War Zone C along the

Cambodian border, leaving behind some 850 dead. Highly effective counterambush

tactics

- [66]

- based on the firepower and mobility of armored forces were developed during

three of the five engagements. These battles showed that armored cavalry with

air and artillery support could more than hold its own against a numerically

superior force, giving airmobile infantrymen time to join forces with the

cavalry to defeat an enemy ambush.

-

- The first of the three U.S. engagements took place when Troop A, 1st Squadron,

4th Cavalry, was ambushed by the 272d Viet Cong Regiment on 8 June 1966, north

of the Ap Tau O bridge on National Highway 13. (See Map 6, inset.) The

Viet Cong were deployed along a five-kilometer stretch of road in positions

extending well beyond the length of the cavalry column. When the ambush was

sprung most of the American troopers were able to reach a small clearing near

the head of the column, where, with the help of artillery and air support,

they desperately fought off the Viet Cong for four hours. When the battle

ended, the enemy had lost over one hundred dead and four taken prisoner, as

well as thirty individual and twelve crew-served weapons. Although successful

the cavalry had made mistakes. Since original estimates of the enemy force

were low, supporting fire was used primarily against the Viet Cong in the

fighting positions near the cavalry force and other enemy forces were left

free to maneuver. Although an infantry reaction force was committed toward

the end,, it did not arrive in time to be a decisive factor. After the commander

and other principals had analyzed the battle, cavalry communications were

changed and coordination of air and artillery was improved. Plans for reinforcement

by airmobile infantry were developed to ensure quick arrival of reaction forces

designed to fight off the main attack and to provide troops for blocking the

enemy withdrawal routes.

-

- Lessons learned on 8 June paid dividends on 30 June when the 271st Viet

Cong Regiment attacked Troops B and C, 1st Squadron, 4th Cavalry, farther

north along Highway 13 near Srok Dong. This time, when the ambush hit Troop

B, Troop C rapidly maneuvered to reinforce. Coordination of fire support had

vastly improved and tactical air and artillery were immediately and effectively

employed. The relief force arrived in time to engage the Viet Cong before

they could withdraw, while exploitation forces were inserted behind the enemy

as far west as the Cambodian border, where another engagement took place.

Enemy losses were heavy-270 dead, 7 taken prisoner; 23 crew-served weapons,

and 40 small arms captured.

-

- Encouraged by the two earlier successes of the 1st Squadron, 4th Cavalry,

Major General William E. DePuy, 1st Infantry Division commander, directed

development of a plan to lure the enemy into

- [67]

- MAP 6

- [68]

- attacking an armored cavalry column. Colonel Sidney B. Berry, Jr., 1st Brigade

commander, prepared a two-phased flexible plan that could be easily modified

for attacks on either Route 13 or the Minh Thanh Road. Five possible enemy

ambush positions were selected during the planning, and, as it turned out,

the site selected as the most likely was where the enemy struck. To increase

the chances that the enemy would attack, rumors were circulated for the benefit

of Viet Cong agents that a small armored column would escort an engineer bulldozer

and several supply trucks from Minh Thanh to An Loc on 9 July. The true size

of the force, called Task Force DRAGOON, was a well-kept secret; actually

it was composed of Troops B and C, 1st Squadron, 4th Cavalry, and Company

B, 1st Battalion, 2d Infantry.

-

- Phase I, a deception plan involving an airmobile feint, covered the movement

of artillery and supporting forces. The infantry forces that were to attack

the flanks of the ambush and block withdrawal routes had to be in position

to act quickly if the ambush occurred. The 1st Brigade began positioning these

forces on 7 July, with infantry and artillery at Minh Thanh, more infantry

and artillery just north of Minh Thanh Road, and an infantry battalion near

An Loc. (Map 6) The trap was set.

-

- At 0700 on 9 July 1966 Phase II started as the task force moved south from

An Loc on National Highway 13, turned southwest on Minh Thanh Road, and arrived

at Checkpoint Dick at 1025 without incident. There were artillery and air

preparations on the western side of the bridge at Checkpoint Dick to soften

up possible enemy concentrations. Following the air strikes, the 3d Platoon,

Troop C, supported by covering fire, moved across the bridge with two engineer

minesweeper demolition teams. A quick check was made for demolition charges

and mines but no evidence of an enemy attempt to sabotage the bridge was found.

Since the cavalrymen were now only 1,500 meters from the site selected earlier

as the most likely ambush location, tension among the troops mounted. The

Troop C commander directed the 1st Platoon to cross the bridge, pass through

the 3d Platoon, and advance down the road toward Minh Thanh.

-

- As the 1st Platoon moved past the 3d Platoon, a planned air strike was made

near Checkpoint Tom while a CH-47, a helicopter with four.50-caliber machine

guns, a 40-mm. grenade launcher, and two 7.62-mm. machine guns, struck the

area southwest of Checkpoint Tom. There was no return fire. At 1100, midway

between Checkpoints Dick and Tom, the crew of the lead vehicle of the 1st

Platoon spotted ten Viet Cong running across the road. Minutes

- [69]

- later when ten more crossed, the 1st Platoon's lead tank blasted them with

canister. The tank fire brought an almost unbelievable volume of enemy fire

on the entire Troop C column. The enemy had taken the bait.

-

- At the beginning the 1st Platoon took the brunt of the enemy fire; the commander

of the lead tank was killed. Within a few minutes the platoon leader reported

his scout section out of action, and a little later he himself was wounded.

As the platoon began to draw back under the heavy pressure, the platoon sergeant,

who had taken command, moved to the front of the column to get the lead tank

remanned and fighting. He directed the M132, a flamethrower, to send liquid

fire into the enemy positions on the north side of the road. Two of the 1st

Platoon's M113's were hit and burst into flames. The 1st Platoon now had two

tanks and four M113's firing at the enemy. The 2d Platoon, leading with an

M48A3 tank, closed rapidly on the 1st Platoon and deployed in a herringbone

formation, concentrating its fire to the north side of the road.2

The 3d Platoon, heavily engaged as soon as the first rounds were fired,

could not move forward to join the 1st Platoon and a 300-meter gap existed

between the two platoons. The Viet Cong were unable to take advantage of the

gap, however, because of the intense fire. Tracked vehicles along the entire

column were firing as rapidly as possible, continuing to jockey for position

and avoid the enemy antitank fire while artillery fire and air strikes hit

the enemy positions.

-

- The task force commander ordered Troop B forward to relieve the enemy pressure

and called for more artillery and air support. At first the enemy's main attack

had seemed to come from the south, but it was soon apparent that the enemy

force was concentrated to the north side of the road. The plan for infantry

reinforcement was put into action while the cavalrymen fought. When Troop

B closed on the tail of Troop C, the fighting intensified. Within forty-five

minutes the tanks had fired more than 50 percent of their canister and the

M113's were nearly out of .50-caliber ammunition. Several Troop B tracked

vehicles filled the 300-meter gap between the 2d and 3d Platoons of Troop

C, and one platoon was assisting the lead element of Troop C.

-

- With Troop B well disposed throughout the length of the Troop C column,

the squadron commander ordered Troop C to

- [70]

- pull back to Checkpoint Dick for resupply. Some supporting infantry were

by then attacking the flanks of the ambush force while others were flown north

in helicopters to take blocking positions. The battle raged for another half-hour,

then the enemy began to leave protective cover and run away from the withering

fire of the cavalrymen and supporting forces. As the Viet Cong fled, infantry,

artillery, and tactical aircraft intercepted and destroyed them. An infantry

sweep the following day discovered small groups of Viet Cong still trying

to escape the trap. The searching forces found 240 of the enemy dead, took

8 prisoners, and captured 13 crew-served weapons and 41 small arms. By 1630

of 10 July the search was complete, and the 1st Squadron, 4th Cavalry, withdrew

to Minh Thanh. The enemy plan to seize An Loc failed; the 1st Squadron, 4th

Cavalry, had reopened Route 13, a vital line of communications, and had assisted

in defeating the 9th Viet Cong Division.

-

- Two significant facts emerge from these engagements. First, contrary to

tradition, armored units were used as a fixing force, while airmobile infantry

became the encircling maneuver element. Second, the armored force, led by

tanks, had sufficient combat power to withstand the mass ambush until supporting

artillery, air, and infantry could be brought in to destroy the enemy. Engagements

with armored elements forcing or creating the fight and infantry reinforcing

or encircling were typical of armor action in 1966 and 1967.

-

- Armored forces, like other American units, generally. avoided deliberate

night actions in the early days of the Vietnam War. The scarcity of night

fighting equipment, poor training of U.S. forces in night fighting, the difficulty

of crashing through a dark jungle in armor at night, fear of ambush, and a

general reluctance to fight at night, all militated against planned night

actions. Armored operations at night were either reactions to enemy attacks

or defenses of night positions. Such techniques as the use of helicopters

and artillery flares for directing armored units and the employment of tank

searchlights to illuminate likely ambush sites were eventually developed,

but for most of the early years the night belonged to the enemy.

-

- In an effort to change this situation armored leaders developed several

techniques. One, nicknamed thunder run, involved the use of armored vehicles

in all-night road marches using machine gun and main tank gun fire along the

roadsides to trigger potential ambushes. While this procedure increased vehicle

mileage and maintenance problems, it often succeeded in discouraging enemy

- [71]

- road mining and ambushes. Highway 13 from Phu Cuong to Loc Ninh became known

as Thunder Road because of the frequency of these runs and their similarity

to those in the Robert Mitchum movie. Roadrunner operations, named after the

cartoon character, although similar to the thunder runs were carried out by

larger units on armed route reconnaissance that looked for trouble spots.

These operations took place both day and night.

-

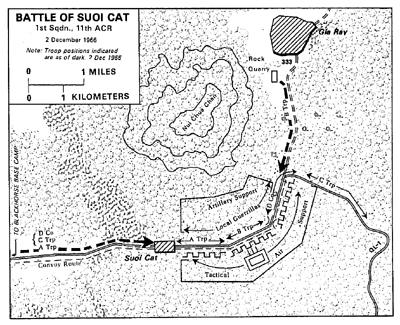

- The Blackhorse Regiment

-

- Although armored operations in Vietnam were catalysts for new concepts and

innovations, there seemed to be, at MACV staff level, a lingering reluctance

to deploy armored forces, especially those with M48A3 tanks. Nowhere is this

better illustrated than in the events that preceded the arrival of the 11th

Armored Cavalry Regiment, the Blackhorse Regiment.3

Proposals were made to move the 11th Cavalry to Vietnam as early as December

1965, when General Westmoreland requested the regiment for the purpose of

maintaining security along Route 1. His subsequent desire to use the unit

for other missions precipitated a discussion of the regiment's table of organization

and equipment. In late December 1965, the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam,

requested equipment modifications to the 11th Cavalry tables, including substitution

of light M41A3 tanks for medium tanks in the tank companies of the regiment's

squadrons and M 113's for both medium tanks and M114 reconnaissance vehicles

in the cavalry platoons. After evaluating the proposed changes, the Department

of the Army concluded that the regiment could not be sent as early as General

Westmoreland had requested if all proposed changes were made.

-

- The answer of the U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, that a mechanized

brigade was required in lieu of the regiment, created considerable consternation

among armor officers in the 11th Cavalry and in the Pentagon. It seemed that

the largest armor unit yet requested for Vietnam would be eliminated before

it had a chance to perform, and with it would go the hopes of many who believed

that more armored forces were needed. The request for a brigade prompted a

study by the Army staff, which considered as alternatives deploying a mechanized

brigade, reshaping the 11th Cavalry, or sending the 11th Cavalry as it was

then organized.4

- [72]

- Deployment of a modified 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment, with M113's substituted

for the medium tanks and reconnaissance vehicles of the cavalry platoons,

was considered the best alternative in view of the regiment's unusual capability

for decentralized operations. The cavalry regiment had a higher density of

automatic weapons, possessed long-range radios, and had more aircraft than

a mechanized brigade. It had better means of gathering intelligence, was capable

of rapid internal reinforcement, and possessed its own artillery in its squadron

howitzer batteries.

-

- When agreement on the unit's organization was reached, the 11th Cavalry

began final preparations for Vietnam. Since M113's were to replace tanks in

the cavalry platoons, they were modified for use as fighting vehicles by attaching

a shield for the .50-caliber machine gun, and pedestals and shields for two

side-mounted M60 machine guns. The concept and design were exactly that adopted

by the South Vietnamese armor forces three years earlier, and subsequently

recommended to American units by the advisers to the Vietnamese Armor Command.

With the modifications the M113 was called the armored cavalry assault vehicle,

or ACAV, a name coined by the 11th Cavalry troopers, probably in memory of

the tanks the M 113's replaced.

-

- The 11th Cavalry arrived in Vietnam in early September 1966. Shortly after

its arrival the Military Assistance Command welcomed its second U.S. Army

tank battalion, the 2d Battalion, 34th Armor, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel

Raymond L. Stailey. Part of the 4th Infantry Division before being sent to

Vietnam, the battalion was attached to II Field Force in the III Corps Tactical

Zone to replace the 1st Battalion, 69th Armor, which had moved to the II Corps

area. On 19 September Company B was detached to the 1st Infantry Division

at Phu Loi, and on 5 October Company A was detached to the 25th Infantry Division

at Cu Chi. Finally, Company C was sent north to I Corps Tactical Zone until

December. The practice of parceling out its tank companies was to haunt this

battalion throughout its service in Vietnam; seldom did it have more than

one tank company under battalion control. This unfortunate practice, so characteristic

of the French in Indochina, was symptomatic of a command with few armored

units. It reached a new high later in the war when, for a period of several

months, the commander of the 2d Battalion, 34th Armor, again had no tank companies

to command. The 11th Cavalry also suffered from the

- [73]

- ACAV PREPARES TO ESCORT A TRUCK CONVOY

-

- detachment practice, and there were periods when the headquarters controlled

only the regimental air cavalry troop.

-

- After Operation ATTLEBORO in September and October 1966, units of the 11th

Cavalry returned to Bien Hoa to continue Operation ATLANTA, whose mission

was to clear and secure lines of communication in three provinces near Saigon

and to secure the new Blackhorse Base Camp, 13 kilometers south of Xuan Loc.

At first the operation was limited to clearing and securing Route 1 from Xuan

Loc to Bien Hoa and Route 2 to the base camp. As ATLANTA continued, however,

the 11th Cavalry extended its operations away from the roads and throughout

the area.

-

- From the standpoint of the number of enemy killed, and, more important,

from the number of roads opened to military and civilian traffic, ATLANTA

was a success. Regimental experience varied from roadrunner and convoy escort

duties to cordon and search operations in which the squadrons sealed off an

area and then worked, both mounted and dismounted, to drive out the enemy.

Throughout, the regiment was able to move at will both on and off the roads,

and experienced little difficulty with the ter-

- [74]

- rain. Areas hitherto considered Viet Cong sanctuaries were entered by armored

columns that destroyed base camps, fortifications, and supplies.

-

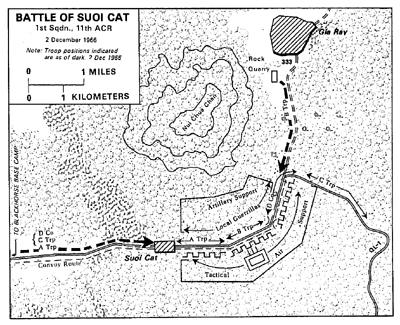

- It was during Operation ATLANTA that the 11th Cavalry fought its first major

battle. Twice the enemy tried to ambush and destroy resupply convoys escorted

by units of the 1st Squadron, but in both attempts was defeated by the firepower

and maneuverability of the cavalry. The second of these two ambushes took

place on 2 December 1966 near Suoi Cat, fifty kilometers east of Saigon. The

steps taken in this action illustrate a procedure for dealing with ambushes

that became standard in the regiment.

-

- When intelligence reports indicated that there was an enemy battalion in

the vicinity of Suoi Cat, the 1st Squadron conducted a limited zone reconnaissance

but found no signs of the enemy. Shortly thereafter, on 2 December 1966, Troop

A was handling base camp security, Troop B was securing a rock quarry near

Gia Ray, and the balance of the squadron was performing maintenance at Blackhorse

Base Camp. (Map 7) Early that morning a resupply convoy from Troop B, consisting

of two tanks, three ACAV's (modified M113's) and two 21/2-ton trucks, had

traveled the

- MAP 7

- [75]

-

TANKS AND ACAV'S FORM DEFENSE PERIMETER AT BRIDGE SITE.

Distance between vehicles was much less than armor doctrine stated because

of need for mutual support and to prevent infiltration.

- [76]

- twenty-five kilometers from the rock quarry to Blackhorse without incident.

-

- At 1600 the convoy commander, Lieutenant Wilbert Radosevich, readied his

convoy for the return trip to Gia Ray. The column had a tank in the lead,

followed by two ACAV's, two trucks, another ACAV, and, finally, the remaining

tank. Lieutenant Radosevich was in the lead tank, and after making sure that

he had contact with the forward air controller in an armed helicopter overhead,

moved his convoy out toward Suoi Cat. As the convoy passed through Suoi Cat,

the men in the column noticed an absence of children and an unusual stillness.

Sensing danger, Lieutenant Radosevich was turning in the tank commander's

hatch to observe closely both sides of the road when he accidently tripped

the turret control handle. The turret moved suddenly to the right, evidently

scaring the enemy into prematurely firing a command detonated mine approximately

ten meters in front of the tank. Lieutenant Radosevich immediately shouted

"Ambush! Ambush! Claymore Corner!" over the troop frequency 5

and led his convoy in a charge through what had become a hail of enemy

fire while he blasted both sides of the road. Even as Lieutenant Radosevich

charged, help was on the way. Troop B, nearest the scene, immediately headed

toward the action. At squadron headquarters, Company D, a tank company, Troop

C, and the howitzer battery hastened toward the ambush. Troop A, on perimeter

security at the regimental base camp, followed as soon as it was released.

The gunship on station immediately began delivering fire and called for additional

assistance, while the forward air controller radioed for air support.

-

- When the convoy reached the eastern edge of the ambush, one of the ACAV's,

already hit three times, was struck again and caught fire. At this point Troop

B arrived, moved into the ambush from the east, and immediately came under

intense fire as the enemy maneuvered toward the burning ACAV. Troop B fought

its way through the ambush, alternately employing the herringbone formation

and moving west, and encountering the enemy in sizable groups.

-

- Lieutenant Colonel Martin D. Howell, the squadron commander, arrived over

the scene by helicopter ten minutes after the first fire. He immediately designated

National Highway 1 a fire coordination line, and directed tactical aircraft

to strike to the

- [77]

- east and south while artillery fired to the north and west. As Company D

and Troop C reached Suoi Cat, he ordered them to begin firing as they left

the east side of the village. The howitzer battery went into position in Suoi

Cat. By this time Troop B had traversed the entire ambush area, turned around,

and was making a second trip back toward the east. Company D and Troop C followed

close behind, raking both sides of the road with fire as they moved. The tanks

fired 90-mm. canister, mowing down the charging Viet Cong and destroying a

57-mm. recoilless rifle.6

Midway through the ambush zone, Troop B halted in a herringbone formation,

while Company D and Troop C continued to the east toward the junction of Route

333 and Route 1. Troop A, now to the west of the ambush, entered the area,

surprised a scavenging party, and killed fifteen Viet Cong.

-

- The squadron commander halted Troop A to the west of Troop B. Company D

was turned around at the eastern side of the ambush and positioned to the

east of Troop B. Troop C was sent southeast on Route 1 to trap enemy forces

if they moved in that direction. As Troops A and B and Company D consolidated

at the ambush site, enemy fire became intense around Troop B. The Viet Cong

forces were soon caught in a deadly crossfire when the cavalry units converged.

As darkness approached, the American troops prepared night defensive positions

and artillery fire was shifted to the south to seal off enemy escape routes.

A search of the battlefield the next morning revealed over 100 enemy dead.

The toll, however, was heavier than that. Enemy documents captured in May

1967 recorded the loss of three Viet Cong battalion commanders and four company

commanders in the Suoi Cat action.

-

- The success of the tactics for countering ambushes developed during ATLANTA

resulted in their adoption as standard procedure for the future. The tactics

called for the ambushed element to employ all its firepower to protect the

escorted vehicles and fight clear of the enemy killing zone. Once clear, the

cavalry would regroup and return to the killing zone. All available reinforcements

would be rushed to the scene as rapidly as possible to attack the flanks of

the ambush. Artillery and tactical air would be used to the maximum extent.

This technique was used with success by the 11th Cavalry throughout its stay

in Vietnam.

- [78]

- Mine and Countermine

-

- Although tanks and ACAV's were effective against the enemy when he could

be found, they were vulnerable to the explosive antivehicular mine. For example

in June 1966, while moving back into the Boi Loi and Ho Bo woods in III Corps

Tactical Zone, the 1st Battalion, 5th Infantry (Mechanized) , lost fourteen

M113's to mines in eight days of operation. Only eight M 113's were eventually

returned to service. In the period January-March 1967 on Highway 19 east of

Pleiku in 11 Corps, the 1st Battalion, 69th Armor, found 115 mines; 27 were

detected and disarmed, 88 exploded and damaged tanks. From June 1969 to June

1970, the 11th Cavalry encountered over 1,100 mines in the northern III Corps

Tactical Zone. Only 60 percent were detected; the other 40 percent accounted

for the loss of 352 combat vehicles.

-

- Generally, tank hulls proved capable of absorbing the shock of a mine explosion,

preventing serious injuries to the crews and damage to interior components.

But when an APC hit a mine, particularly an APC that was gasoline-fueled,

several crew members were usually wounded seriously or killed. Drivers were

especially vulnerable, and crew members frequently rotated this dangerous

job. For these reasons tanks normally led in clearing operations or reconnaissance

in force. A study of the six-month period from November 1968 to May 1969 found

that throughout Vietnam 73 percent of all tank losses and 77 percent of all

armored personnel carrier losses were caused by mines. Another study conducted

in December 1970 found that mines accounted for over 75 percent of all combat

vehicles lost. This was not news to armor troopers.

-

- In past wars countermine equipment had been chiefly designed to clear lanes

through minefields where the mines were laid in patterns. In Vietnam, however,

such minefields were never encountered; instead, the enemy planted mines at

random on a massive scale. Antitank mines ranged from pressure-detonated to

improvised mines, some as heavy as 250 pounds. The enemy also recovered unexploded

artillery and mortar shells and aircraft bombs and rigged them with pressure-detonated

or command-detonated fuzes. Mines were set on roads and off roads, in open

field and dense jungle. There seemed to be no pattern that applied countrywide.

-

- American units dealt with the mine problem by trying to prevent the enemy

from laying mines, by trying to detect implanted mines, and by deliberately

detonating mines-usually with a tank. Traditionally, countermine operations

were efforts to detect mines

- [79]

- ENGINEER MINESWEEPING TEAM CLEARS HIGHWAY 13

-

- after they were emplaced but in Vietnam, with no set battle lines, the enemy

could be attacked as he attempted to lay mines. Ambush patrols were set up

at likely enemy mining locations, and sensors were used to detect the people

emplacing mines. The best way to defeat random mining was to kill the soldiers

who were laying the mines or destroy the supply system that furnished the

mines. Anything short of that was bound to be frustrating work with little

promise of success.

-

- Units like the 2d Battalion, 2d Infantry (Mechanized), used night roadrunner

operations in an attempt to discourage or kill those placing mines along the

road at night.7

In addition to conducting runs at random intervals, the roadrunners

called for planned artillery fire and reconnoitered by fire between friendly

night defensive positions. The 11th Armored Cavalry employed thunder runs

using tanks, and where possible fired harassing artillery fire on habitually

mined sections of road. Other units made extensive studies of the tactical

areas and developed mine incident charts. These studies pinpointed areas that

were constant mine problems

- [80]

- and invariably exposed three common factors: all the pinpointed spots were

close to areas dominated by the local Viet Cong; all afforded the enemy good

cover and routes in and out; and all had a high rate of mine incidents when

armored units were present.

-

- The information, gathered from these studies indicated that the use of ambush

patrols at night could be a valuable means of preventing mining operations,

but it was limited, particularly in armored units, by the number of men that

could be spared from other duties. Since armored units ranged over wide areas

it was also impossible to study each area long enough to acquire sufficient

information to act upon. Sensors, used in locations where there was repeated

mining, were passive in nature but were responded to by artillery fire when

activated. While their use seemed to reduce incidents, the precise effect

was difficult to measure.

-

- If the enemy could not be prevented from laying mines, the next step was

to find the mines by some means other than running over them with vehicles.

A mine sweeping team or troops familiar with an area could often visually

locate mines. Informers who received on-the-spot cash payments and a degree

of anonymity for themselves were a moderately reliable source of information.

Metallic mine detectors and individual probing were useful but time consuming.

On the whole, more road mines were spotted by alert armor crewmen than were

found by mine detectors. Armored units were often the security element for

clearance teams, and in most corps tactical zones had a daily mission of road

clearance by probing and by using minesweepers and vehicles. Clearing units

used one tank on the road and one on each shoulder; the tanks on the shoulders

preceded the roadbound vehicle to destroy any wires to command-detonated mines

in the road. The wheeled vehicles carefully followed in the tracks of the

lead vehicle. Even fake mine-laying by the Viet Cong was successful since

it also had to be checked. No system of mine detection was markedly effective,

however, and losses occurred regularly in clearing operations.

-

- Most armored vehicle crewmen took preventive measures to reduce mine injury

to themselves and damage to their vehicles. The men always wore flak jackets

and steel helmets. The floors of tracked vehicles were sometimes overlaid

with sandbags, ration and ammunition boxes, or unusable flak jackets to prevent

mine blast penetration.8

In most units troops rode on top of the vehicles,

- [81]

- feeling that it was better to get blown off the top than to be blown up

inside. The Viet Cong countered by placing mines in trees. Some armor leaders

even went so far as to have the crews of lead vehicles wear ear plugs to reduce

ear damage when a mine was detonated. Tanks survived mine damage much better

than M 113's. To reduce mine damage to M 113's, "belly armor" kits

arrived in 1969. When this supplemental armor was applied to M113's and Sheridans,

it protected them from mine blast rupture, saved many lives, and gave the

crews added confidence, but it did not solve the mine problem.

-

- As early as 1966 commanders in the field began to ask for better devices

to deal with the mine danger. They were in particular need of a mine detector

that could be mounted on a vehicle and that was capable of finding any type

of mine, metallic or nonmetallic, no matter how fuzed. Finally, in 1969, the

U.S. Army, Vietnam, asked the Mobility Equipment Research and Development

Center to provide a device that could detect or destroy low-density mines

on roads and that could move faster than a man carrying the portable mine

detector then in use. The center's answer was the expendable mine roller,

a mechanism to be mounted on and pushed in front of an M48 tank. The roller

was tested at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, and delivered to Vietnam for combat

evaluation in the fall of 1969.

-

- Although the 11th Cavalry, which made the first test, felt strongly that

the device would tie down a much needed vehicle, it fitted one tank with the

roller and tested for over eighty kilometers, but no mines were found. Eventually

the device was damaged when it was taken into the jungle, for which it was

not intended. The regiment concluded that it was unsatisfactory, primarily

because of its twenty-ton weight and maintenance requirements. Again in the

fall of 1969 the 1st Brigade, 5th Infantry Division (Mechanized), tested the

roller in Quang Tri near the Demilitarized Zone, where it proved unsuitable

for the soft sandy soil of the region and was eventually ruined by a mine.

The 4th Infantry Division made the third test of the mine roller, which was

mounted on a combat engineer vehicle in lieu of a tank. In an experiment the

roller detonated four mines and the 4th Division requested more rollers. Eventually

twenty-seven were used in Vietnam. At the end of American participation in

the war, the mine roller had not been fully accepted, and there was still

need for a mine destroyer that would allow rapid movement.

- [82]

- TANK-MOUNTED MINE ROLLER PREPARES TO CLEAR HIGHWAY 19

- [83]

-

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

-

- page created 17 January 2002

-

Return to the

Table of Contents

-