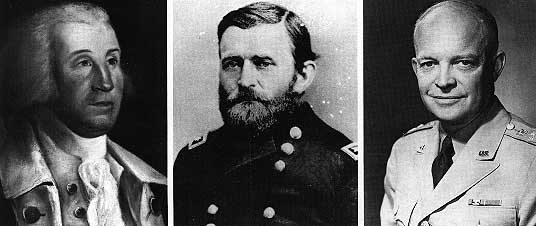

On 14 June 1775 the Second Continental Congress, meeting in Philadelphia, adopted a resolution under which ten companies of expert riflemen would be immediately raised, six in Pennsylvania, two in Maryland, and two in Virginia. The "compleated" companies were to "march and join the army near Boston, to be employed . . . under the command of the chief Officer of that army." On the following day the Congress elected George Washington, Esq., of Virginia to be general and commander in chief "of the forces raised and to be raised in defence of American Liberty." In these two conspicuous legislative resolves the United States Army was born and its first senior uniformed officer appointed.1 Neither the Army nor its commander sprang full-blown into being upon congressional cue. The institution would begin to take shape only in the fires of the war of American independence, while the individual would pass to his successors the problems inherent in the development and perpetuation of the senior military office.

From their earliest appearances on the North American continent, Europeans had found it necessary to defend themselves, first against the native inhabitants, later against each other as well as against the American Indian. As England and France developed footholds in the New World their interests clashed, and both dispatched military forces and cultivated indigenous allies in their attempts to prevail on the colonial frontier. By the time the English colonists along the Atlantic Coast of North America had become disenchanted with the mother country, they had participated as British subjects in colonial extensions of four world conflicts: the War of the Grand Alliance (1689–1697), known in America as King William’s War; the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714), identified in the colonies as Queen Anne’s War; the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748), called King George’s War in the New World; and the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763), distinguished in North America as the French and Indian War.

Colonial units carried the burden of operations in the first three of these conflicts and joined British regulars in the fourth. The colonists were thus well indoctrinated in British concepts of military and civil affairs, modified by their requirements and experiences in colonial life, as they moved down the road toward separation from the parent country and creation of their own. Their problem was to disengage from an armed, tenacious, and authoritarian monarchy; mold a group of highly independent colonies into a common government under new national authority; and bring a variety of colonial elements into a unified force under central command and control. Much of the burden would fall initially upon the new commander’s shoulders.2

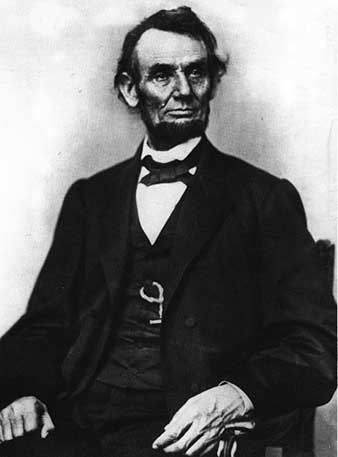

George Washington was the unanimous choice of his fellow delegates to command the American Army. A youthful surveyor of frontier lands, he became interested in things military as a member of the Virginia militia, and the colonial governor, Robert Dinwiddie, selected him to carry a message to the French on the Ohio frontier to warn them that they were encroaching upon lands claimed by England. When the French rejected the imputation and expanded their intrusion, Dinwiddie in 1754 commissioned Washington a lieutenant colonel and sent him with a small force to secure a British outpost at the forks of the Ohio River (near present-day Pittsburgh). Unfortunately, the French had captured it and had established Fort Duquesne there before Washington arrived, and although Washington defeated a French scouting party, he was then besieged in his fortified camp—Fort Necessity at Great Meadows, Pennsylvania—and forced to surrender.

In 1755 the British sent General Edward Braddock with a force of regulars against Fort Duquesne, and Washington went along as the commander’s aide. The French defeated the British in the Battle of the Monongahela, inflicting heavy losses,

[1]

mortally wounding Braddock, and putting the Redcoat remnants to flight. Washington was a tower of strength in getting the survivors back across the mountains to Virginia.

Dinwiddie next appointed Washington commander of all Virginia forces with the responsibility of defending 300 miles of frontier with a like number of men, an assignment that embodied on a regional level the multiform difficulties he would face on a national scale in the future. He joined a second expedition against Fort Duquesne, but when the French withdrew before the British reached the site, erasing a central problem of frontier defense, Washington resigned to take up private life once again.3

As a prominent Virginian and concerned citizen, Washington moved easily from military to civil affairs even as he pursued his private interests, and between 1758 and 1774, both as a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses sitting at Williamsburg and a justice of Fairfax holding court in Alexandria, he came to understand the negative influences of British colonialism. As the Second Continental Congress convened at Philadelphia in May 1775, George Washington of the Virginia delegation was recognized for his wide experience in military, civil, and business affairs; his sound ability and common sense; his scrupulous sense of honor and duty; his innate dignity and impressive bearing; and, above all, political and geographical contours with enough appeal to overcome sectional rivalries. All of this combined to ordain his selection as commander in chief.

Washington’s stewardship as the Army’s senior officer was unique and, by its nature, could not have been duplicated by his successors. He took office as the head of the forces of a budding nation whose government was still in its formative stages. Already at war, the country yet had no national army with established civilian leadership, no departmental military organization, no administrative rules and regulations, no supply system, no senior officer structure, no institutional seasoning. Much of this would have to be developed by the left hand as the right hand fought the war.

In the days following Washington’s appointment the Congress moved quickly to give substance to its plans, requirements, and intentions, authorizing two major generals and eight brigadier generals to serve under Washington; establishing the offices of adjutant general, quartermaster general, commissary general, paymaster general, and chief engineer, as well as some other positions; setting pay scales; and adopting Articles of War for the governance of the military establishment.4

Washington took command of the Army in the field at Cambridge, Massachusetts, on 3 July 1775. On the following day he issued the general order that formalized the American Army as a national institution under the authority of the central government: "The Continental Congress having now taken all the Troops of the several Colonies . . . into their Pay and Service . . . they are now the Troops of the United Provinces of North America."5 To bring "a mixed multitude of people" under order and discipline, he gave his personal attention to such matters as strength returns, roll calls, health and sanitation, efficiency, distinctions in rank, obedience to orders, and punishment of offenders. And as he kept the British Army bottled up in Boston, he dealt with such major problems as short-term enlistments, senior officer rivalries, scarcity of powder, inadequate military intelligence, and deficiencies in both organization and training.6

As the country fought for and edged toward true yet distant autonomy, it moved also, albeit slowly, toward the organizational and managerial arrangements that would provide for direction and control over the military forces of a free people. In the absence of a chief executive the Congress created boards and committees to carry out its policies, and one of its first moves along this line—antedating by three weeks the Declaration of Independence—was the establishment in June 1776 of the Board of War and Ordnance to see to "the raising, fitting out, and despatching [of] all such land forces as may be ordered for the service of the United Colonies."7 Among other things, the board was to keep a register of officers in the service of the colonies; maintain a record of the state and disposition of troops; account for arms, artillery, and other supplies; oversee the exchange of military correspondence between the Congress and the United Colonies; and preserve original letters and papers.

Development of a true war office and delineation of the responsibility and authority of the senior officer of the American Army came slowly, for there was a government to establish, a war to be fought, and experience to be gained through a long process of trial and error. Initially, the government was weak and the board became bogged down in minutiae, leaving General Washington, under the exigencies of field operations, to fill a void and make decisions on his own. This independence was consistent with Congress’ mandate to Washington. As supreme commander, he had been "vested with full power and authority to act as you shall think for the good and welfare of the service."8 Congress had been quite explicit in its reasoning, for

whereas all particulars cannot be foreseen, nor positive instructions for such emergencies so before hand given but that many things must be left to your prudent and discreet management, as occurrences may arise upon the place, or from time to time fall out, you are therefore upon all such accidents or any occasions that may happen, to use your best circumspection and (advising with your council of war) to order and dispose of the said Army under your

[3]

[4]

command as may be most advantageous for the obtaining of the end for which these forces have been raised, making it your special care in discharge of the great trust committed unto you, that the liberties of America receive no detriment.9

It was only natural that this broad mandate be curtailed as the central government broadened its knowledge of military matters and increasingly assumed its legitimate responsibilities. Step by step the composition of the war office was modified from five legislators to three nonlegislators, then to a mix of two congressmen and three outsiders. But there was a weakness in the committee process, and in February 1781 the Congress created the post of secretary at war to replace the Board of War and appointed Major General Benjamin Lincoln as its first occupant in October of that year.10

Lincoln picked up the reins of a war office with fairly well-defined powers and responsibilities. The secretary at war was directed by the Congress "to examine into the present state of the war-office [and] the returns and present state of the troops, ordnance, arms, ammunition, cloathing, and supplies of the armies of the United States . . . , to obtain and keep exact and regular returns of all the forces . . . , to prepare estimates for paying and recruiting the armies . . . , to execute all the resolutions of Congress respecting military preparations . . . , to transmit all orders and resolutions relative to the military land forces . . . , to make out, seal, and countersign all appointments . . . , [and] to report to Congress the officers necessary for assisting him in the business of his department."11

By and large, the parties primarily responsible for military matters in these formative years of the Republic found their terms of reference in their respective operational spheres in the field and at the seat of government, and although their functions were by no means mutually exclusive, the individuals were reasonable and dedicated men who saw what must be done and did it. Accumulating experience suggested, and the secretary at war and commander in chief worked out, a successful division of authority. Military business was conducted by correspondence and in personal visits to each other’s headquarters, and cooperation, not competition, was the order of the day.

Inescapably there were differences. In the period after the Cornwallis surrender at Yorktown, Virginia, Washington disagreed with Lincoln over the new secretary’s estimate of remaining British strength and intentions in North America and his assessment of American force requirements and general prospects, and the divergencies prompted

The British defeat at Yorktown in October 1781 ended major active campaigning in the Revolutionary War and opened a static period for the patriot forces facing remaining enemy troop concentrations at New York in the North and Charleston in the South. While lengthy peace negotiations proceeded an ocean away, American thoughts turned to consideration of the form and composition of a postwar Army. Since regulars and militia had shared

[5]

in the fighting and would share in the victory, sharp differences developed over the question of whether the future security of the nation should be entrusted to a standing Regular Army or to militia that would be called up in emergencies. This was only part of the larger question of whether the country would have a strong central government or a loose federation of states; whether, indeed, the citizen would assume not only the privileges of freedom and equality envisioned by the Declaration of Independence but the obligations and responsibilities, including military service, associated with a democratic system. As events unfolded, opinion came to favor a centralized government but for a long time shunned a standing Army.13

The transitional period from war to peace left the Army at its lowest ebb. After the signing of the Treaty of Paris on 3 September 1783, Washington, at congressional direction, began to demobilize the Army, a process that was completed after the British evacuated New York in November. On 23 December, the war concluded and his mission accomplished, George Washington resigned his commission and returned home to Virginia. He left Major General Henry Knox, the next senior officer, to preside over an Army reduced to one regiment of infantry and one battalion of artillery—about 600 men. The decline did not stop there.

Despite the conclusion of a peace treaty, a dual threat continued to hover over the young nation in the Northwest, where the British, in contravention of peace terms, continued to garrison a chain of posts along the inland waters bordering Canada and where state sessions of frontier lands to the central government saddled the Congress with the problem of Indian defense over a wide region. Obviously the United Colonies must have an Army, but of what form and nature? To deal with a complex set of circumstances that involved politics, land, money, manpower, and deployments, the Congress, as a first step, on 2 June 1784 directed General Knox to discharge all but 80 of the 600-man force and to station the remnant at West Point (55), New York, and Fort Pitt (25), Pennsylvania, to guard military stores. There being no need for a major general to command a company-size force, Henry Knox was retired and nominal command of the Army passed on 20 June 1784 to the next senior officer, Captain John Doughty, a veteran of Revolutionary War service and head of the detachment at West Point.14

Doughty’s seniority was necessarily short-lived, lasting only about seven weeks, and had an organizational rather than institutional complexion. Despite postwar disarray, sectional differences, Lincoln’s retirement, and deficiencies in the Articles of Confederation under which the government was operating, the Congress saw the need for action in the field of military affairs. Only one day after it reduced the Army to 80 men, and on the very eve of the current session’s adjournment, the legislators passed an act calling upon four states—Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania—to furnish a total of 700 men from their militias for the national army. Pennsylvania, with the largest quota (260 as opposed to 165 each from Connecticut and New York and 110 from New Jersey) and with an exposed position on the frontier, filled its assessment promptly, and, as a result, command of the new force went to a Pennsylvanian. Lieutenant Colonel Josiah Harmar, who had served with several of his state’s regiments during the Revolution, became the Army’s senior officer on 12 August 1784.15

As had been Doughty’s situation on a smaller scale, Harmar, despite his status as the ranking of-

[6]

ficer of the Army, became a field rather than a staff and institutional commander. With the war office vacant and with military concerns among the more pressing matters before it in the spring of 1785, the Congress appointed Henry Knox as the second secretary at war and issued a call to the four states of the previous year for new troops with longer enlistments to man the First American Regiment. Most of the Army was posted in detachments along the western frontier, and Harmar, far removed both organizationally and geographically from the seat of power, had all he could handle as the field commander. On top of that, the authoritarian Henry Knox was in the secretary’s chair, fully assured that his powers as secretary at war embraced those of commander in chief, a role which, by experience and inclination, he was well prepared to exercise.16

The secretary’s task was not an easy one, and in its way represented the problems of the government as a whole. To the existing Indian peril, British presence, and state dissension connected with the Western lands were added the difficulties of raising, supplying, and funding military forces. The government, lacking the power to tax and operating in a period of depression, faced serious fiscal problems that were reflected throughout the colonies. Discontent finally escalated into an open unrest among debtors that took its most organized and violent form in Massachusetts, where an insurrectionist band led by one Daniel Shays attacked the Springfield Arsenal.

Although Shays’ Rebellion was unsuccessful, it challenged both state and federal government, coalesced a gathering concern over the need for a national army and stronger central government, and lent impetus to a movement to convene a Constitutional Convention. In 1787 the government entered a two-year period of transition from the Confederation to a constitutional system, and the war office, the active focus of a variety of state functions, served as "the chief connective element."17

In formulating and refining the new nation’s system of government, the framers of the Constitution assigned to Congress the functions to raise and support armies, make rules for the government and regulation of the land forces, and declare war. They created what had been lacking under the Confederation—an executive branch of government—and made the president the commander in chief of the Army and Navy, thereby ensuring that this important command function would be entrusted to a civil rather than to a military official.

On 30 April 1789, George Washington, who had been the nation’s first senior military officer, became its first senior civil official under the new Constitution: president of the United States. Three months later, on 7 August 1789, the Congress established the Department of War, changed the title of the department head from secretary at war to secretary of war, and made that official directly responsible to the president rather than the Congress. Henry Knox remained in office to become the first secretary of war, and Josiah Harmar, who had been brevetted brigadier general in 1787 and was still on the frontier, remained the Army’s senior officer.

If from the beginnings of constitutional government the role of the secretary as the minister charged with running the War Department—acting with the president’s authority and in his behalf in the conduct of military affairs—was codified, accepted, and understood, that of the senior officer of the Army was not so clear. During the century and a quarter from George Washington’s installation as commander in chief to Samuel B. M. Young’s induction as chief of staff, uncertainty, misunderstanding, and controversy swirled around the office, involving from time to time some of the leading figures of their day. The title as well as the authority of the incumbent seemed in a constant state of flux.

The inception of constitutional government ensured not only that "a politically responsible President replaced the hereditary monarch as Commander in Chief," but that Washington’s historical standing as the only uniformed commander in chief of the American Army was assured. After Washington resigned in 1783, fluctuations in the strength of the Army, the rank and location of the senior officer, the viewpoint of an incumbent secretary, and usage in government circles all influenced the designation and mode of operation of the senior officer. Commander in chief, general in chief, major general commanding in chief, commanding general of the Army, lieutenant general of the Army, General of the Army—all were applied at one time or another and in one way or another to the senior officer of the Army.

As with George Washington and Benjamin Lincoln, the senior civil and military figures of the early years of the Republic went about their business with little friction; the complexities of government, inexperience of officials, geographical separation, limitations of communication, and field operational requirements kept them absorbed in their respective spheres. Harmar, who served as the senior officer until March 1791 before returning to Pennsylvania to become state adjutant general; Major General Arthur St. Clair, who succeeded him for a one-year tour between terms as governor of the Northwest Territory; and Major General Anthony Wayne, the late Georgia congressman who occupied the Army post up to his death on 15 December 1796, were all involved in Indian warfare on the Northwestern frontier—Harmar and St. Clair disastrously, Wayne successfully—and could not have jousted with the secretary of war about lines of authority and separation of powers even had they been so inclined. Brigadier General James Wilkinson, at home with controversy and intrigue, might have relished

[7]

confrontation, but he, too, served in the western arena, where he led a force of volunteers against Indians north of the Ohio before being assigned to Wayne’s command. Upon the latter’s death, Wilkinson ascended to the ranking position in the Army for an eighteen-month stint, to July 1798, with duties that kept him on the frontier as a field rather than institutional commander.18

Throughout this period the Army commanders conducted their operations with inadequate strength and supplies, poorly trained troops, and imperfect logistical support. The Congress, prompted by the Harmar and St. Clair reverses, gradually increased the Army’s strength until Anthony Wayne was able to train a respectable force along legionary lines and, with some 3,000 men, redeem the Army’s reputation in the Battle of Fallen Timbers.19

External forces now intruded upon the young nation as French and British contentions spread across the Atlantic to involve American shipping and raise the possibility of war with France. George Washington, only sixteen months out of the presidency, received his country’s call once again as, early in July 1798, President John Adams dispatched Secretary of War James McHenry to Mount Vernon with Washington’s appointment as "Lieutenant General and Commander in Chief of all the armies raised or to be raised for the service of the United States. . . ." Unfortunately, Washington was sixty-six, the call was to some extent politically inspired, and a general controversy developed over which officer among three candidates—Alexander Hamilton, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, or Henry Knox—should be the senior major general and, in effect, second in command to the aging Washington. Although Knox outranked the others, Hamilton, at Washington’s behest, was elevated to the ranking position.20

Washington had informed the secretary of war that he would accept the new charge with the understanding that he would become fully active only if his presence should be required in the field. This stipulation kept him in the mold of his predecessors—a field rather than an institutional commander. As things turned out, his presence in the field was not required. Except for a visit to Philadelphia to work with McHenry and Hamilton on an organizational plan for a Provisional Army to meet the putative emergency, Washington exercised his command function principally from his Mount Vernon home, while the influential and ambitious Major General Hamilton, in combination with a weak secretary of war, carried the burden of day-to-day details at the seat of government under President Adams’ watchful and suspicious eye. Adams, in appointing Washington to the Army command, had acted not only to neutralize a strong sentiment for Hamilton’s selection to the post but also out of concern, however justified, for what uses Hamilton might have found for an Army he controlled.21

As 1799 unfolded, the French threat and the perceived need for Washington’s name and services receded, and the general’s death on 14 December brought the century and an era to a close.

As he had foreseen the possibilities, Alexander Hamilton was ideally positioned to succeed Washington as the Army’s senior officer, and on the day of his predecessor’s death he picked up the reins for an abbreviated tenure. He presided over the preparation of new drill regulations and the discharge of such of the Provisional Army as had been mobilized—about 4,100 of a planned 50,000 men—before departing military service on 15 June 1800.22 The evaporation of the emergency and the reduction of the Army to peacetime strength erased all prospects for the martial glory that might have held him in the service. Yet, as Washington’s aide, a former member of the Continental Congress, and the nation’s first secretary of the Treasury, Hamilton remained an influential citizen up to his death in 1804 in a dual with his bitter political rival, Vice President Aaron Burr.

Brigadier General James Wilkinson now returned to the scene for a second tour of nominal military seniority. In almost twelve checkered years spent principally on the southern frontier, he negotiated with the Indians, fraternized with the Spaniards, consorted then broke with Aaron Burr, served as governor of Louisiana Territory, and survived several courts of inquiry and a court-martial inspired by his excessive use of authority and private commercial dealings. His stewardship, if such it might be called in view of its organizationally disconnected and militarily incoherent character, was of a piece with the trials of the first decade of the nineteenth century when the nation and the Army were groping for policies and procedures to make government and institutions work. Regrettably, as the threat of war with France faded, the menace of renewed conflict with England increased. By the time the Congress declared war against England in June 1812, Wilkinson had reverted to a subordinate position and Major General Henry Dearborn had become the Army’s senior officer.23

Like many of the nation’s potential military leaders, Henry Dearborn had acquired more than enough campaign experience and reputation during the Revolutionary War to mark him as a candidate for recall in emergencies. After his discharge in 1783, he had maintained a tenuous military connection through militia ties, and from 1801 to 1809 he operated in the mainstream of military affairs as President Jefferson’s secretary of war. But like many veterans, he had turned sixty, and he was on the eve of his sixty-first birthday in January 1812 when President Madison made him the Army’s senior major general. With the outbreak of the War of 1812 he became, not the professional uniformed head of the Army posted in Washington, but a coordinate field

[8]

commander—and one of a number of aging officers not well equipped mentally or physically to deal with the rigors of campaign, a worthy enemy, and deplorable deficiencies in manpower, supply, and administration.24

After an inept performance on the northeastern Canadian front, and with recurring health problems, Dearborn, still the senior major general, was transferred in July 1813 to command at New York City, where he served until his discharge on 15 June 1815.

Seniority among the Army’s uniformed leaders passed next to Major General Jacob Jennings Brown. As commander in western New York in the late war, he had added much-needed luster to American arms in operations at Chippewa and Lundy’s Lane on the Niagara front. Unlike his predecessor, Brown was of a younger, post-Revolution generation; only forty, the vigor and zeal he brought to the ranking position were not to be dedicated to war so much as peace. His extended tenure carried him more than halfway through an era characterized as "The Thirty Years’ Peace," a period free of general conflict and marred only by occasional Indian troubles to the South and West, notably the First and Second Seminole Wars and the Black Hawk War.

On the heels of the War of 1812 the Congress passed the act of 1 May 1815 fixing the peacetime strength at 10,000 and establishing two geographical regions, the Division of the South commanded by Major General Andrew Jackson, and the Division of the North headed by General Brown. Some important evolutions occurred at the upper levels of the War Department during Brown’s incumbency.

Secretary of War William H. Crawford, who entered office in August 1815 with the conviction that the country should have in place in peacetime the kind of headquarters organization required in war, consolidated and enlarged upon a general staff concept, created by the Congress in 1813, to deal with the Army’s housekeeping functions. But his fourteen-month tenure was too brief for a concerted effort to strengthen the peacetime Army. That fell to his successor, John C. Calhoun.

Before Calhoun took office in October 1817, however, and while Acting Secretary George Graham was in charge, an incident occurred that brought to a head some long-standing questions concerning the operation of the chain of command, the responsibility and authority of senior officials, and the relationships between staff and line.

Secretary Crawford had ordered Major Stephen H. Long to New York. Although Long, a topographical engineer, was assigned to General Jackson’s Division of the South, the field commander was not informed of the transfer, and when he learned of it he wrote the department asking for an explanation. When Acting Secretary Graham replied testily that the department assigned officers "at its discretion," Jackson complained to President Monroe, questioning

a practice under which Washington could move officers without a field commander’s knowledge. Upon learning that Jackson had instructed his attached officers to obey no departmental order that did not come through the commander, Monroe informed Jackson that the orders of the War Department were those of the president. As the case evolved, the central issue—proper use of the chain of command—became sidetracked in favor of a discussion of the president’s role as commander in chief.25

Despite the fact that he was the loser on the constitutional side of the question, Jackson was partially vindicated in the practical aspects when Calhoun, while sustaining the presidential prerogatives, announced that future orders would be issued through field commanders to the maximum extent possible. But the matter was far from settled. Jackson had raised the nagging problem of the distribution

[9]

of authority between staff and line; should communications between the heads of the technical services (Engineer, Quartermaster, Subsistence, Medical, etc.) in Washington and their assistants in the field, and from those subordinates back to their chiefs in Washington, be direct or through field command channels? Strangely enough, the senior officer of the Army, who might well have been at the center of the controversy, especially in light of his dual role as a division commander, was little more than a bystander. Yet the moment had come when that would change to some degree.26

The War of 1812 had demonstrated the need for more centralized control over the scattered elements of the Army. The creation of two main geographical divisions had answered this in part, but an apparently logical next step—that of establishing a single uniformed head of the whole Army—was left in suspense. Only George Washington had served in this capacity, first in 1775 during the Revolutionary War when the Congress elected him general and commander in chief, again in 1798 during the anticipated crisis with France when the president, with congressional authorization, had appointed him lieutenant general and commander in chief. In the first instance the country was at war, lacked a chief executive, and was desperately in need of an all-powerful field commander. In the second instance, the Congress and the president knew their man; knew that, as one who had served at the pinnacle in both military and civil capacities, he subscribed fully to the principle of separation of powers and knew his place. But without a Washington, what would a strong-willed figure in uniform—an Alexander Hamilton, for example, or an Andrew Jackson—make of the position of commander as opposed to senior officer, and despite the constitutional role of the president as commander in chief? How would the functions, the powers, the responsibilities be distributed? A partial answer was soon forthcoming.

Secretary Calhoun acted in conjunction with the reorganization of 1821, which cut the Army to about 6,000 men. The Divisions of the North and South were abolished, and were replaced by Eastern and Western Departments, commanded respectively by Brigadier Generals Winfield Scott and Edmund Pendleton Gaines. At the apex, a possible dilemma was negated when Major General Andrew Jackson left service to become governor of Florida. Calhoun then brought Major General Jacob Jennings Brown to Washington as commanding general of the Army.27

The formal establishment of the position of commanding general and Brown’s designation raised more questions than were answered. Hovering over the arrangement were a number of uncertainties: if the president was commander in chief of the Army and the secretary of war was his direct agent in the administration of the Army, what was the role of the commanding general? As his position was not defined constitutionally or by statute or regulation, what was his relationship to the president, the secretary, the bureau chiefs, the field commanders? Was he simply a professional military adviser to the secretary?

Jacob Brown seems not to have been disturbed by these considerations. Despite his energy and dedication, he appears to have been more interested in making an anomalous arrangement work than in making himself an agent of challenge or an instrument of disruption. What effect a wartime wound and an apparent stroke in late 1821 may have had on his efficiency is also unknown. In any case, his service under Secretaries of War Calhoun and Barbour

[10]

up to his death in February 1828 was unmarked by crisis, and many of the procedural questions went unanswered.28

Brown’s death left the Army with no major generals and opened the way for selection of a successor from among the regular brigadiers. At the moment, Winfield Scott and Edmund Pendleton Gaines, the department commanders, were the only two in that grade. Properly positioned in the chain of command, they were the logical candidates, except that, proud, ambitious, and arrogant individuals both, and highly sensitive to considerations of relative rank and General Brown’s mortality, they had long been locked in a public dispute over seniority that not only shook the Army to its foundations but escalated into a national scandal. So far as the record was concerned, the choice was a difficult one. Both had been promoted to colonel on 12 March 1813 and both to brigadier general on 9 March 1814. Gaines was the senior at the lieutenant colonel level, but Scott was senior in a brevet major generalcy.

Ultimately these considerations became academic, for President John Quincy Adams had had his fill of the spectacle of two of the country’s senior military figures publicly denouncing each other and making constant claims for preferment. He called a cabinet meeting to hear the views of his departmental secretaries on the subject, found a general consensus with his own impressions, and on 29 May 1828 reached down below the troublesome pair to appoint the chief of engineers, Colonel and Brevet Major General Alexander Macomb, as commanding general of the Army.29

A protege of Alexander Hamilton, and with an excellent record in the War of 1812 and later special assignments, Macomb wisely stepped aside to let the president and the secretary of war deal with Scott’s insubordinate announcement that he would ignore the new commander’s orders as those of a junior officer. Such fulminations led to Scott’s suspension

[11]

from his departmental command and placement on a list of officers awaiting assignment. His representations to both houses of Congress fell upon unsympathetic ears, and only after a change in national administrations was the suspension lifted. Scott then went abroad on a six-month leave of absence, and time and the counsel of friends finally prompted him to accept the facts of life and preserve his great abilities for future crises. Meanwhile, Macomb, to distinguish his preeminence over other two-star brevet major generals, resorted to the simple device of inserting in the Army Regulations of 1834 a provision that the insignia of the major general commanding in chief should be three stars. Thus in image if not in true rank, Macomb placed himself on a par with a distinguished predecessor, the General Washington of 1798.30

It was only natural that the basic considerations of leadership and chain of command—the essence of military operation—should suggest the permanent establishment at headquarters of a uniformed commander of the Army. If there were commanders at every other level, why not at the top? It might also have been assumed that the duties of the senior uniformed officer were so self-evident as to require no regulatory expression; only Washington, serving at the outset of nationhood, had been issued formal terms of reference by the civil authority, and these had related principally to the conduct of field operations. In the intervening years until Jacob Brown’s specific designation as commanding general, the senior officer seemed to see himself, and to be viewed by others, more as a field than an institutional figure. Even Brown did not depart noticeably from that mold despite his titular designation and station in Washington.

But now a statement of functions appeared in the Army Regulations of 1834—the same edition that sewed a third star on General Macomb’s epaulettes. Article XLI, titled "The Commander of the Army," delineated the top uniformed official’s responsibility and authority thus:

1. The military establishment is placed under the orders of the major general commanding in chief, in all that regards its discipline and military control. Its fiscal arrangements properly belong to the Treasury Department, under the direction of the Secretary of War. While the general in chief will not interfere with the concerns of the Treasury, he will see that the estimates for the military service are based upon proper data, and made for the objects contemplated by law, and necessary to the due support and useful employment of the army. The general will watch over the economy of the service, in all that relates to expenditure of money, supply of arms, ordnance, and ordnance stores, clothing, equipments, camp equipage, medical and hospital stores, barracks, quarters, transportation, fortifications, military academy, pay, and subsistence, in short, every thing which enters into the expenses of the military establishment, whether personal or material. In carrying into effect these important duties, he will call to his council and assistance, the staff, and those officers proper, in his opinion, to be employed in verifying and inspecting all the objects which may require attention. The rules and regulations established for the government of the army, and the laws relating to the military establishment, are the guides for the commanding general, in the performance of his duties.

2. All estimates, exhibits, and reports, of the several branches of the military service, required annually to be made, with a view to their transmission to Congress, will be addressed to the commanding general of the army, who, after examining them, and fixing with the officers concerned, the amounts required for the service, will present them to the Secretary of War, for his consideration.31

In these paragraphs and two more in Article XLIV fixing the responsibilities of inspectors general to the commanding general, the central authority of the Army’s senior officer and the subordination of the staff were well established. Indeed, the provisions of the second paragraph appear to have been so objectionable to the bureau chiefs that it was dropped from the 1835 edition of the regulations, and the first paragraph was amended to shift fiscal control back to the staff bureaus, stipulating that the Army’s "fiscal arrangements properly belong to the administrative department of the staff and to the Treasury Department, under the direction of the Secretary of War." Despite the modification, the "General-in-Chief" still was directed to "see that the estimates for the military service are based upon proper data, and made for the objects contemplated by law, and necessary to the due support and useful employment of the army."32

It was the perceived intrusion of the commanding general into their operations and his presumed interdiction of their direct access to the secretary of war that disturbed the bureau chiefs. Their case, and the nature of the controversy over lines of authority and separation of powers, was set out by Colonel Roger Jones, the adjutant general of the Army, on 24 January 1829. In a beautifully engrossed paper addressed to Secretary of War Peter B. Porter under the title, "Analysis of the theory of the Staff which surrounds the Secretary of War," Colonel Jones noted that the Adjutant General’s, Ordnance, Quartermaster, Subsistence, Pay, and Medical Departments and the Corps of Engineers "constitute [the] many avenues through which the various acts and measures of the Executive . . . are communicated and executed, and such is the symmetry in this organization, that whilst each member of the military staff of the War Department is confined to the sphere of his own peculiar functions, all regard the Secretary as the common superior, the head of the harmonious whole."33

The adjutant general went on to point out that everything relative to military commissions, under the secretary of war, had been conducted in his office since 1797; that these were administrative duties under the secretary "in contradistinction to . . . Military Staff duties under the General in Chief. . . ." He wondered if these or similar execu-

[12]

tive functions had ever been assigned to any general officer of the line; whether, indeed, they were compatible with the high military duties of a commander of the Army? Ought a general in chief aspire to these comparatively subordinate responsibilities, and could it be to the interest of the Army that he assume them and virtually relinquish "the glories of the field?"34

If it did nothing else, Colonel Jones’ paper exposed some of the complexities inherent in the question of whether the Army’s senior officer was, or should be, a commander or a chief of staff. It was not a simple matter to resolve. Bureau chiefs were reluctant to surrender the authority and prestige of their independent jurisdictions; senior officers were proud and ambitious individuals, jealous of hard-won rank and status and fiercely protective of honor; and secretaries were transient civilians often uninitiated in military affairs and usually not in office long enough to come to grips with complicated military organization, procedures, and personalities. Accommodation among such disparate interests was not easy to achieve, and apart from competition and bias, it was not that clear in 1829 just how the senior officer of the Army should function. It would take three-quarters of a century and further clashes before the problem would be resolved.

After General Macomb died in office on 25 June 1841, Major General Winfield Scott, who had been waiting in the wings for thirteen years and had more than redeemed himself in official and public eyes in a series of skillfully conducted and eminently successful peacekeeping missions for the government, was appointed commanding general of the Army and took office on 5 July. The Second Seminole War was coming to a close, and the only cloud on the horizon was possible trouble with Mexico over its lost province of Texas. When James K. Polk won the American presidency on a platform that included annexation of Texas by the United States, and that process occurred in mid-1845, Mexico declared war on her northern neighbor.

President Polk, a Democrat and well aware that three of his predecessors—George Washington, Andrew Jackson, and William Henry Harrison—had been helped into office by battlefield achievements, saw further possibilities along this line as Brigadier General Zachary Taylor, a member of the Whig opposition, won a series of victories over the Mexicans along the Rio Grande. When it became apparent that the war could not be won in that northern theater, Polk turned with great reluctance to Winfield Scott, also a Whig and a former presidential contender in that party, to conduct a landing at Vera Cruz on Mexico’s east coast and drive inland against the enemy capital of Mexico City.The president, it may be noted, had been left with no alternative when the Congress rejected his proposal to create the rank of lieutenant general and place Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri, no soldier but a Democrat, in the post as commander of the coming expedition.35

The wartime emergency and the employment of the commanding general as a field commander perpetuated the ambiguities of the position. President Polk, in effect, vacated the office by assigning Scott to command the Vera Cruz expedition; by limiting him, upon his departure from Washington, to control over the field force; and by appointing no successor in Washington. The Army thus went without a commanding general from 24 November 1846 to 10 May 1849, raising questions as to the need for such an office. The president, the secretary of war, and the bureau chiefs operated as the headquarters of the Army, and in the absence of a uniformed professional head, President Polk and Secretary William L. Marcy served as their own general staff. Despite some mastery of military detail they had neither the time nor the training, much less the responsibility, for carrying out the planning and programming function of a general staff. How their successors might have met the challenge was yet another question. In any case, when Scott returned to the United States in 1848 and peacetime conditions obtained once again, Scott and Taylor, the two major generals, were assigned to co-equal divisions, Eastern and Western, and Scott assumed command of the former with headquarters in New York.36

When Zachary Taylor became president in 1849, Scott was restored to the position of commanding general. A special order of 10 May specified that, "In pursuance of the orders of the President of the United States, Major General Scott will resume the command of the Army. . . ." The order went on to prescribe that the headquarters of the commander of the Army would be "at, or in the vicinity of New York." Apparently the location was agreeable to both Taylor and Scott, although how a commander of the whole Army—even one as small as the 10,000 to 12,000 men of the moment—could possibly fulfill the responsibilities implied by the title when he was so far removed from the executive base in Washington was not explained. It was also apparent that the commanding general was still to be a field rather than an institutional commander.37

Scott, who had outlasted Generals Macomb and Gaines as well as President Polk, now survived President Taylor. After Taylor’s death in 1850, Scott transferred his headquarters back to Washington, where, at President Fillmore’s request, he served for about three weeks as acting secretary of war. In 1852, as the Whig candidate for president, he was defeated by Franklin Pierce. In January 1853 Scott moved his headquarters back to New York to put some distance between himself and the victorious incoming administration. From there he carried on a running battle with the new secretary of war, Jefferson Davis, over the settlement of his remaining outstanding Mexican War accounts and other matters. When he

[13]

[14]

questioned the secretary’s authority over the commanding general, he was overruled by the president.38

On 15 February 1855 the Congress, in a joint resolution, revived the grade of lieutenant general, and on 7 March the Senate confirmed General Scott as brevet lieutenant general to rank from 20 March 1847, the date of the capture of Vera Cruz. Scott thus became the first officer since George Washington to hold three-star rank. Yet the distinction was an honorary one for a deserving officer’s long and distinguished service—temporary elevation for an individual, not permanent creation of an additional echelon that would relieve a grade compression at the upper levels of the Army.39

Brevet Lieutenant General Scott spent the final months of a twenty-year tenure—the longest in office of all the senior officers of the Army even deducting the Mexican War hiatus—urging President Buchanan and Secretary of War John B. Floyd to act to protect military installations in the South as the slavery issue began to split the nation. Following President Lincoln’s inauguration in March 1861, Scott brought his headquarters back to Washington and a far more sympathetic administration. But age and infirmity were closing in on him, and on 1 November 1861, at seventy-five and upon his own application, the Army’s senior officer retired after half a century of military service.

Upon Scott’s retirement Lincoln appointed Major General George Brinton McClellan, forty years Scott’s junior, as commanding general of the Army. A graduate of the United States Military Academy, McClellan had served with Scott’s forces in the Mexican War, taught engineering at West Point, studied European military systems on the scene, and designed a first-rate saddle. His effective performance against Confederate forces in early operations in West Virginia, coupled with Brigadier General Irvin McDowell’s defeat at Bull Run, led Lincoln to appoint McClellan in July 1861 to head the Army of the Potomac. An able administrator who worked wonders in preparing the Army of the Potomac for coming battles, McClellan in the top military post proved to be slow at launching and cautious in executing field operations. Although he might have been more effective as the senior officer at the seat of government than as a field commander, he proved to be flawed in that role as well by arrogating to himself an excessive degree of power, even to the extent of blocking both the president and the secretary of war from his confidence. His methods could not long endure, and on 11 March 1862 President Lincoln relieved him as commanding general so that he could devote full attention to the upcoming Peninsular Campaign.40

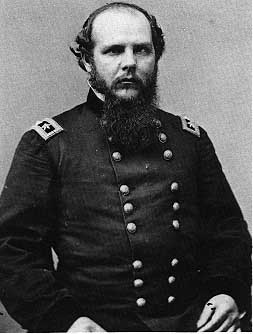

A second period now intervened when the office of commanding general lay vacant, for no suitable successor to McClellan was readily available. Standing by, however, were two figures ready to exercise the functions in addition to their own larger ones: President Lincoln and his new secretary of war, Edwin M. Stanton. In a four-month period they brought a measure of coordination into the operation of the Union armies, responded intelligently to Major General Thomas Jonathan ("Stonewall") Jackson’s Shenandoah Valley threat in May, and sought professional advice by tapping retired Major General Ethan Allen Hitchcock to head an advisory board composed of the bureau chiefs. But both were aware of their limitations and their constitutional obligations, and on 23 July 1862 President Lincoln brought Major General Henry W. Halleck to Washington as commanding general of the Army.41

A graduate of the United States Military Academy, Henry Wager Halleck had served in engineer assignments, published an influential book on military art and science, and held responsible positions in California during the Mexican War before resigning in 1854 to engage in railroad and mining enterprises. Seven years later, at the outbreak of the Civil War, he resumed Regular Army service as a newly commissioned major general, with assignment to the western theater. Upon his selection as senior officer in the summer of 1862, he left command of the Union forces in the West with a series of victories to his credit, in which subordinates—notably Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant—were largely instrumental.

Well fitted by training and experience to fulfill the joint command and administrative responsibilities embodied in the anomalous position of commanding general, Halleck, yet became bogged down in detail and buffeted by political pressures, and as events moved on he failed to live up to the command expectations of the president and the secretary of war. Eventually, Lincoln and Stanton resumed active control over military operations and both used Halleck more as an agent who translated their directions into military form and issued them to the field than as a commander in his own right.42

Although Lincoln endured this uncomfortable situation patiently for an extended period, he came increasingly to think about replacing Halleck, and inevitably his attention was drawn to the victor of Henry and Donelson, Vicksburg and Chattanooga—now Major General Ulysses S. Grant.

Like McClellan and Halleck, Ulysses Simpson

[15]

Grant was a graduate of the United States Military Academy. He had served with distinction in the Mexican War, first with Taylor’s forces as a troop officer, then with Scott’s as a quartermaster with a combat role. He had resigned from the Army in 1854 to try his hand, with uniformly little success, at a variety of civilian occupations, and returned through Illinois volunteer channels as the Civil War opened in 1861. As a commander under Halleck in the western theater, he gave the Union some badly needed victories, acquiring public acclaim in the process. A bill was introduced in the Congress to revive the grade of lieutenant general and confer it upon Grant in recognition of his outstanding battlefield performance. The occasion offered an opportunity to correct, at least in part, an inequity in grade structure that existed in the American Army.

The fact that the Army did not have sufficient separation in rank at the top levels of the uniformed service, vexing during the Scott-Gaines-Macomb discords and on through the Mexican War, had become even more manifest with the major expansion of the Union forces during the Civil War. It led to the unusual, if not absurd, situation under which the Union had a major general commanding a division, a major general commanding a corps, a major general commanding a field army, a major general commanding a geographical region, and a major general commanding all the armies of the United States. Five echelons thus were commanded by officers of the same rank, and the major general who commanded the American armies of more than a million men held no higher rank than the major general who commanded a field division of a few thousand men. Now, in the spring of 1864, this logjam might be broken, although not as an official correction of an inequitable system, but, as in the case of General Scott, through a personal tribute to an individual officer.43

Despite Grant’s reputation as a fighting and winning general, not all legislators were in favor of reviving the rank of lieutenant general and assigning it to Grant. In the light of recent experience, went the speculation, suppose the honor had been available to McDowell, McClellan, or Halleck? Why honor one general before the war was over? What could a lieutenant general do that a major general could not do as well? Should a distinguished field commander be sacrificed to the departmental bureaucracy? All of these equivocations were turned aside, and after an extended debate in the Senate as to whether Grant’s appointment should be recommended by name in the legislation (it was not), the measure was passed on 29 February 1864.44

On 12 March 1864 the Army issued orders of the president of the United States formalizing the new command arrangements. They contained some interesting distinctions concerning the position of senior officer. Major General Halleck, "at his own request," was relieved from duty as general in chief of the Army. Lieutenant General Grant was "assigned to the command of the Armies of the United States." It was stipulated that the "Headquarters of the Army will be in Washington, and also with Lieutenant General Grant, in the field" (italics added). Here again was that inclination to view the commanding general as a field commander, or, put another way, as commander of the armies in the field, not as a top staff coordinator at the seat of government. But now there was a striking concomitant in the second paragraph of the order: "Major General H. W. Halleck is assigned to duty in Washington as Chief of Staff of the Army, under the direction of the Secretary of War and the Lieutenant General Commanding."45

How much of this was a calculated effort to improve command arrangements and how much a propitiary gesture to Halleck who was suffering a demotion it is hard to say. Certainly the action gave Halleck a title and duties more in line with the manner in which he had been functioning all along, and like a good soldier, he served out the war in this capacity. Through the general order, the president made it known that he expected Halleck’s orders as chief of staff to be "obeyed and respected accordingly," and any blow Halleck may have felt over his change of status may well have been softened by the president’s official tender to him of "approbation and thanks for the able and zealous manner in which the arduous and responsible duties of [commanding general] have been performed."46 Halleck served in his staff role until the war ended in April 1865, then moved on to field assignments.

Grant brought to the role of commanding general the strategic direction and coordination the position had required all along. In Secretary Stanton, General Halleck, and Quartermaster General Montgomery C. Meigs he had an energetic and expert administrative and logistical team to provide the resources for his operational plans, while in President Lincoln he had a commander in chief who respected his abilities and applauded his initiative. He operated in the mode of the modern theater commander, maintaining his headquarters in the field, reporting directly to his civilian superiors, and, unlike McClellan, keeping them informed of his plans.

As lieutenant general and commanding general, Grant presided over four administrative field divisions embracing seventeen subcommands and employing half a million combat soldiers. That some further adjustments were needed in the grade structure was evident in the fact that, under the wartime structure of volunteer rank, Grant was senior to 73 major generals and 271 brigadier generals. The Union could take a back seat to the Confederacy in this regard, for the South had long before solved its grade structure problems by assigning full generals to command separate armies, lieutenant generals

[16]

to command corps, major generals to command divisions, and brigadier generals to command brigades. And at the apex, General Robert E. Lee was additionally appointed general in chief of the Armies of the Confederate States in February 1865. The Union did not bring its senior officer into line until after the war, when a bill was finally introduced to revive the rank intended for but never bestowed upon George Washington. The title of the grade was modified from the 1799 version—General of the Armies of the United States—to General of the Army of the United States. Ulysses Grant assumed four-star rank on 25 July 1866, and Major General William T. Sherman moved into the vacated lieutenant generalcy. Grant thus became Americas first full general under the Constitution, as Washington’s rank had been conferred in 1775 by the Continental Congress.47

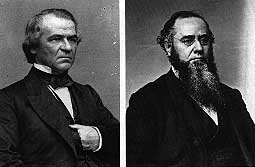

The end of the Civil War, Lincoln’s death, and Grant’s retention of the top military post during a period when the Army acquired a central role in the reconstruction process, placed the commanding general at center stage on the national scene. His position exposed him to problems that, endemic to the job and present in the best of times, were exacerbated by postwar agitation. President Andrew Johnson’s leniency in dealing with the South raised problems for the Army and led to the unusual situation in which the secretary of war and the commanding general found themselves allied with the Congress in opposition to the policies of the commander in chief. The sharp differences between the president and the Congress over how to proceed with reconstruction prompted the legislators to pass a series of acts to assert their supremacy and protect sympathetic executive officials, notably Stanton and Grant, from peremptory presidential reaction.

The Command of the Army Act, attached to the Army Appropriations Act of 1867 and of questionable constitutional validity, provided that presidential orders to the Army be issued through the commanding general whose headquarters would be in Washington, and who could not be removed from office without Senate approval. The Tenure of Office Act denied the president the right to remove cabinet officers—presumably his own appointees—from office without Senate approval, almost a reverse confirmation procedure. The Congress had Secretary Stanton, a Lincoln appointee, in mind in this measure, one that was also of dubious constitutionality. Finally, the First and Third Reconstruction Acts divided the South into five military districts and authorized their commanders, major general in rank, to superintend civil processes and report directly to Washington, essentially free of civil control. The net effect of all of this was to make the commanding general rather than the commander in chief the effective head of the Army, or at least that part of it assigned to reconstruction duty in the South.48

Highly sensitive to constitutional prerogatives, angered by congressional attempts to frustrate his reconstruction policies, and indignant over opposition within his executive family, President Johnson on 12 August 1867 suspended Stanton from office and appointed General Grant as secretary of war ad interim. Grant, ill-disposed to be at the center of a controversy between his departmental superior and the commander in chief, yet thoroughly devoted to the Army, accepted the assignment reluctantly and exercised the title while retaining his position as commanding general. When the Congress, which had been in recess, resumed its deliberations, the Senate refused to concur in Stanton’s suspension, invoked the Tenure of Office Act, and Grant relinquished and Stanton reclaimed the secretaryship in January 1868. Johnson retaliated by dismissing Stanton, by offering the post to General Sherman, who refused it, and by attempting to place Adjutant General Lorenzo Thomas in the office. The Congress then launched impeachment proceedings against the president.49

The Senate conducted the trial from March into May, and the final vote of 35 to 19 in favor of impeachment fell one short of the margin required for conviction. With the disruptive issue settled through constitutional processes but with none of the parties—president, Congress, secretary—so substantially vindicated as to revel in victory, Stanton resigned and the turmoil subsided. The president, and the Congress, perhaps subdued by the experience, agreed, although for different reasons, upon Major General John M. Schofield as a candidate to pick up the war office portfolio.

Only months later, Grant, little damaged by the imbroglio, was elected president of the United States. One day after his inauguration on 4 March 1869 he promoted Lieutenant General William T. Sherman to full general and commanding general of the Army. Major General Philip H. Sheridan was advanced one grade to fill the lieutenant general vacancy.50

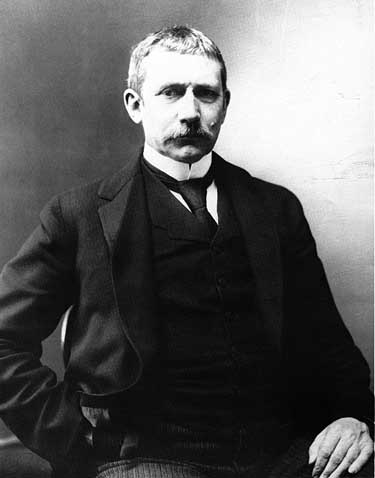

Like his three immediate predecessors, William Tecumseh Sherman had graduated from the United States Military Academy. Commissioned in 1840, he held various assignments in the southern states and then served as an aide and adjutant in the East and in California during the Mexican War. He resigned in 1853 to try his hand at banking and law, but his lack of success turned him to the more compatible and more successful occupation of superintendent of a military college in Louisiana. Back in the Army in time to command a brigade in the 1861 Bull Run disaster, he was transferred to the western theater and participated in a succession of operations that culminated in his command of the Union forces there and final defeat of the Confederate armies in the deeper South. He was in command of the Division of the Missouri, with headquarters at St. Louis,

[17]

when he was ordered to Washington in March 1869 to be the Army’s commanding general. Sheridan replaced him at St. Louis.

Having been exposed, as the Army’s senior officer and secretary ad interim, to the long-standing controversy between the commanding general and the bureau chiefs, if not the secretary of war, President Grant now had it in his power to resolve matters in the general in chiefs favor on behalf of his successor. To Sherman’s great satisfaction Grant did just that on 5 March 1869, directing through Secretary Schofield that "The Chiefs of the Staff Corps, Departments and Bureaus will report to and act under the immediate orders of the General commanding the Army. All official business, which by law or regulation requires the action of the President or Secretary of War, will be submitted by the General of the Army to the Secretary of War; and in general, all orders from the President or Secretary of War to any portion of the Army, line or staff, will be transmitted through the General of the Army."51

Sherman’s gratification was short-lived. A week later Schofield departed the War Department and Grant installed his principal wartime staff officer, John Aaron Rawlins, in the secretary’s chair. From that vantage point it was Rawlins’ interpretation, abetted by strong pressures from the bureau chiefs and congressional representations, that control of the bureaus should be in the hands of the secretary, not the commanding general. Grant deferred to Rawlins’ wishes, and only three weeks after the Schofield order, a Rawlins directive switched the channels of bureau business away from the commanding general and back to the secretary of war.52

Rawlins attempted to ease Sherman’s displeasure by routing his orders to the bureau chiefs through the commanding general’s office, but the action cooled Sherman’s relationship with Grant and represented another setback to a resolution of the War Department’s own ménage à trois. Rawlins’ death in early September and his replacement by William Worth Belknap in October raised the prospect of even further dissension. Little credit accrued to Sherman for a stint as secretary of war ad interim during the Rawlins-Belknap interregnum.

The new secretary was a strong personality, fully prepared to assume every ounce of power and authority prescribed by law and as much more as imprecise definition, administrative vacuum, and tolerant or irresolute officials might allow. Without hesitation, Belknap took over direction of the War Department bureaus and began to intrude upon Sherman’s domain, renewing, as Sherman described it, "all the old abuses . . . which had embittered the life of General Scott in the days of Secretaries of War Marcy and Davis. . . ."53

One of Sherman’s first encounters with Belknap involved the question of jurisdiction over sutlerships at Army posts. When the secretary infringed upon the commanding general’s prerogatives in this regard by replacing a sutler at Fort Laramie, Wyoming, Sherman restored the ousted party. Belknap then worked through friends in Congress to secure legislation that removed the authority from the general in chief and gave it to the secretary. He then installed his own man.

Uncomfortable in the political atmosphere of Washington, unlikely to prevail in clashes with his civilian superior, and with his authority largely circumscribed by the secretary, Sherman followed perhaps the only course open to him during the Belknap administration—that of absenting himself from the capital. From April to June 1871 he made an inspection tour on the Indian frontier, visiting Army units and installations in Texas (where he narrowly escaped a collision with a Kiowa war party), Indian Territory, Kansas, and Nebraska. From November 1871 to September 1872 he made the grand tour of Europe, traveling as a private citizen but accorded the highest honors, official and social, in most of the

[18]

countries he visited. Then in 1874, taking a lead from Winfield Scott, he moved his headquarters to St. Louis.54

Sherman remained away from the seat of government, abdicating to Belknap the running of the Army as well as the War Department, until 1876. In March of that year the chairman of the legislative committee on expenditures reported to the House of Representatives that Belknap was guilty of malfeasance in office, as a result of having accepted money in return for the award of a post tradership at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. The evidence led the House to vote unanimously to impeach the secretary of war, but Belknap resigned even as the Senate’s vote fell short of the two-thirds margin required for conviction.55

President Grant then appointed Alphonso Taft as secretary of war, and Taft moved at once to get Sherman and Army headquarters back to Washington. His formal order of 6 April returned a goodly measure of control to the commanding general, stipulating that "all orders and instructions relative to military operations, or affecting the military control and discipline of the Army, issued by the President through the Secretary of War, shall be promulgated through the General of the Army, and the Departments of the Adjutant General and the Inspector General shall report to him and be under his control in all matters relating thereto." Said General Sherman: "This was all I had ever asked."56

Sherman spent his remaining years as commanding general on good terms with the last four of the eight secretaries he served under in almost fifteen years as general in chief: James Donald Cameron, George Washington McCrary, Alexander Ramsey, and Robert Todd Lincoln. He saw the Army through its "Dark Ages," when strength, appropriations, pay, and even rank levels were under legislative assault, and he turned aside active attempts to get him to stand as a presidential candidate. He acted with rare consideration when, faced with the statutory requirement to retire at age 64, he relinquished the title of commanding general in November 1883 so that his successor would have time to prepare the Army’s congressional presentation for the coming year.57

When Sherman retired from the Army in February 1884, the troublesome constitutional and statutory problems that surrounded the office of commanding general were yet unresolved. That they had not succumbed to the best efforts of a famous, well-connected, able, strong-willed leader suggested that

[19]

the very nature of the senior officer’s job was uncertain. An irascible Sherman had tried to straighten things out but had failed; now a combative Sheridan would have his turn.

As with his four immediate predecessors, Philip Henry Sheridan had graduated from West Point. He served on the Rio Grande frontier and against Indians in the Northwest before the Civil War drew him into operations in the border states and the South. His instrumental role at Chickamauga and Chattanooga brought him into Grant’s circle, and to command of the cavalry of the Army of the Potomac when Grant took over the main Union forces. A key figure in the final operations in Virginia, he went on to administer the Division of the Gulf during the external threat represented by Maximilian’s suzerainty in Mexico, and was military governor of New Orleans during reconstruction. He followed Sherman to the Division of the Missouri and its Indian campaigns, and to Washington as commanding general, picking up the reins on 1 November 1883.

At the time Sheridan entered office the responsibility and authority of the General of the Army was touched upon in the Army Regulations of 1881. Several of the provisions harkened back to the first published expressions of 1834–1835, and a tenuous trail had appeared in general orders and regulations at intervals down through the years, although the provisions fell far short of the required substance. Article XV of the 1881 edition of the regulations referenced earlier publications for antecedence:

THE GENERAL OF THE ARMY

125. The military establishment is under the orders of the General of the Army in all that pertains to its discipline and military control. The fiscal arrangements of the Army belong to the several administrative departments of the Staff, under the direction of the Secretary of War, and to the Treasury Department.—[G.O. 28, 1876; R.S. 1133, et seq.]

126. All orders and instructions relating to military operations, or affecting the military control and discipline of the Army, issued by the President or the Secretary of War, will be promulgated through the General of the Army.—[G.O. 28, 1869; G.O. 28, 1876.]58

The dichotomy that placed the military establishment under the commanding general for discipline and control and under the secretary and the staff bureaus for fiscal affairs perpetuated the command problem. "Basic to the controversy was an assertion of the primacy of the line over the staff departments, for which there was a theoretical foundation in the developing conception of war as a science and the practice of that science as the sole purpose of military forces. Since the Army existed only to fight, it followed that its organization, training, and every activity should be directed to the single end of efficiency in combat. Therefore, the staff departments, which represented technicism, existed only to serve the purposes of the line, which represented professionalism. From that proposition it followed that the line in the person of the Commanding General, should control the staff."59

Remarking that Sherman "threw up the sponge," Sheridan moved to the attack by announcing it as his interpretation that the president’s order assigning him to command the Army necessarily included all of the Army, not excepting the chiefs of the staff departments. To prove the point, he ordered one of the bureau chiefs out on an inspection tour without informing Secretary of War Robert Todd Lincoln. When Lincoln learned that the head of one of his staff departments had departed on a field trip without his sanction, he informed Sheridan in writing that he was sure the commanding general had missed the true meaning of the president’s order relative to command of the Army.60

Sheridan’s lesson in humility did not stop there. When the secretary of war was absent from Washington, the senior bureau chief served as acting secretary. Thus, as General Schofield later described it, Sheridan, "the loyal subordinate soldier who had commanded great armies and achieved magnificent victories in the field while those bureau chiefs were purveying powder and balls, or pork and beans," had to submit to this because of "the theory that the general of the army was not an officer of the War Department and hence could not be appointed Acting Secretary of War." Although this construction did not endure, it lasted long enough for General Sheridan to suffer a situation under which the adjutant general, junior in rank and supposedly a subordinate under the commanding general, served as acting secretary of war, supposedly over the commanding general.61

Chafing under the compromise of the general in chief’s authority, Sheridan lost no opportunity to raise the problem and press for action to codify the government and regulation of the military establishment and to position the commanding general in the direct line of command at the top of the uniformed service. When General Schofield addressed the subject in his 1885 report to Sheridan concerning developments in the Division of the Missouri, the lieutenant general of the Army was impressed. "I most heartily coincide with the remarks of General Schofield on the need of military legislation," he informed Secretary of War William C. Endicott in his own summary report. "His views are of so much importance that I transfer them bodily to my report:"

There is a great need in the military service of legislation under the power conferred by the Constitution upon Congress to make rules for the government and regulation of the land and naval forces.

It is sometimes of supreme importance that the responsibilities of military administration and command be clearly defined by law. And it is important at all times that the rules for the government of the military service be established, like other laws, by competent authority, after due consideration, and under all the light which experi-

[20]

ence can bring to the aid of the legislature. Regulations thus established, and subject to change only by Congress, would have such degree of stability as to become the basis of a sound military system which up to the present time has not existed in this country.

Although the regulations have undergone changes almost without number, the most important questions involved in the command and government of the Army which have been the source of constant embarrassment and the cause of much controversy for many years, remain unsettled at the present time. No commanding general, from the highest to the lowest, can know the extent or limits of his authority, and no one can have any staff responsible to him for the faithful execution of his orders.