-

-

- In late 1945 the Army began to retool

for new missions, which included occupying former enemy territories and

establishing a General Reserve, while demobilizing the bulk of the World

War II forces. The point system developed earlier, which served as an interim

demobilization measure until the defeat of

- [207]

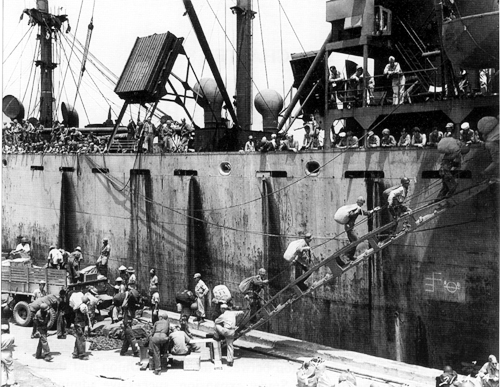

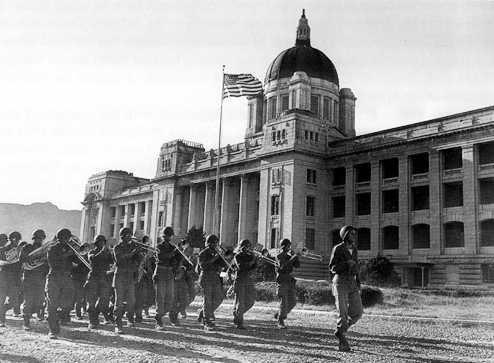

- 41st Infantry Division departs the Philippine Islands, July 1945.

-

- Japan, provided the basic methodology

for execution but did not control the pace of the reduction. As after World

War I, the Army failed to prepare a general demobilization plan. Demobilization

thus proceeded rapidly, driven largely by public pressure and reduced resources,

without the benefit of sound estimates about the size and location of the

occupation forces that the Army would need or the length of time that they

would have to serve overseas. The divisions that returned to the United

States in 1945 and 1946 were generally administrative holding organizations

without any combat capability. They were paper organizations "to bring

the boys home.."2

-

- Within a year after the end of the

war in Europe, the number of divisions on active duty dropped from 89 to

16 (Table 17); of these, 12 were engaged in occupation duty: 3 in

Germany, 1 in Austria, 1 in Italy, 1 in the Philippine Islands, 4 in Japan,

and 2 in Korea. The remaining 4 were in the United States. By the end of

January 1947 three more infantry divisions overseas were inactivated: the

42d in Austria; the 9th in Germany; and the 86th in the Philippine Islands.

In addition, the 3d Infantry Division was withdrawn from Germany and sent

to Camp (later Fort) Campbell, Kentucky, where it replaced the 5th Division.

When demobilization ended in 1947, the number of active divisions stood

at twelve.3

- [208]

- Status of Divisions,

1 June 1946

-

| Division |

Status |

Remarks |

| 1st

Armored |

Inactive |

Inactivated 25 April

1946 |

| 1st

Cavalry |

Active |

Japan |

| 1st

Infantry |

Active |

Germany |

| 2d Armored |

Active |

Fort Hood, Texas |

| 2d Infantry |

Active |

Fort Lewis, Washington |

| 3d Armored |

Inactive |

Inactivated 10 November

1945 |

| 3d Infantry |

Active |

Germany |

| 4th Armored |

Active |

Reorganized as Constabulary |

| 4th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 12 March

1946 |

| 5th Armored |

Inactive |

Inactivated 11 October

1945 |

| 5th Infantry |

Active |

Camp Campbell, Kentucky |

| 6th Armored |

Inactive |

Inactivated 18 September

1945 |

| 6th Infantry |

Active |

Korea |

| 7th Armored |

Inactive |

Inactivated 9 October

1945 |

| 7th Infantry |

Active |

Korea |

| 8th Armored |

Inactive |

Inactivated 13 November

1945 |

| 8th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 20 November

1945 |

| 9th Armored |

Inactive |

Inactivated 13 October

1945 |

| 9th Infantry |

Active |

Germany |

| 10th Armored |

Inactive |

Inactivated 13 October

1945 |

| 10th Mountain |

Inactive |

Inactivated 30 November

1945 |

| 11th Airborne |

Active |

Japan |

| 11th Armored |

Disbanded |

Disbanded 31 August

1945 |

| 12th Armored |

Inactive |

Inactivated 3 December

1945 |

| 13th Airborne |

Inactive |

Inactivated 25 February

1946 |

| 13th Armored |

Inactive |

Inactivated 15 November

1945 |

| 14th Armored |

Inactive |

Inactivated 16 September

1945 |

| 16th Armored |

Inactive |

Inactivated 15 October

1945 |

| 17th Airborne |

Inactive |

Inactivated 14 September

1945 |

| 20th Armored |

Inactive |

Inactivated 2 April

1946 |

| 24th Infantry |

Active |

Japan |

| 25th Infantry |

Active |

Japan |

| 26th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 29 December

1945 |

| 27th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 31 December

1945 |

| 28th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 13 December

1945 |

| 29th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 17 January

1946 |

| 30th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 25 November

1945 |

| 31st Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 21 December

1945 |

| 32d Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 28 February

1946 |

| 33d Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 5 February

1946 |

| 34th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 3 November

1945 |

| 35th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 7 December

1945 |

| 36th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 15 December

1945 |

| 37th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 18 December

1945 |

| 38th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 9 November

1945 |

-

- [209]

- TABLE 17-Continued

-

| Division |

Status |

Remarks |

| 40th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 7 April

1946 |

| 41st Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 31 December

1945 |

| 42d Infantry |

Active |

Austria |

| 43d Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 1 November

1945 |

| 44th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 30 November

1945 |

| 45th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 7 December

1945 |

| 63d Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 27 September

1945 |

| 65th Infantry |

Disbanded |

Disbanded 31 August

1945 |

| 66th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 8 November

1945 |

| 69th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 18 September

1945 |

| 70th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 11 October

1945 |

| 71stlnfantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 11 March

1946 |

| 75th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 14 November

1945 |

| 76th Infantry |

Disbanded |

Disbanded 31 August

1945 |

| 77th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 15 March

1946 |

| 78th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 22 May 1946 |

| 79th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 11 December

1945 |

| 80th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 4 January

1946 |

| 81st Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 20 January

1946 |

| 82d Airborne |

Active |

Fort Bragg, North Carolina |

| 83d Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 27 March

1946 |

| 84th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 21 January

1946 |

| 85th Infantry |

Disbanded |

Disbanded 25 August

1945 |

| 86th Infantry |

Active |

Philippine Islands |

| 87th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 21 September

1945 |

| 88th Infantry |

Active |

Italy |

| 89th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 17 December

1945 |

| 90th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 27 December

1945 |

| 91st Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 1 December

1945 |

| 92d Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 15 October

1945 |

| 93d Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 3 February

1946 |

| 94th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 7 February

1946 |

| 95th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 15 October

1945 |

| 96th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 3 February

1946 |

| 97th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 31 March

1946 |

| 98th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 16 February

1946 |

| 99th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 27 September

1945 |

| 100th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 10 January

1946 |

| 10 1st Airborne |

Inactive |

Inactivated 30 November

1945 |

| 102d Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 12 March

1946 |

| 103d Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 20 September

1945 |

| 104th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 20 December

1945 |

| 106th Infantry |

Inactive |

Inactivated 2 October

1945 |

| Americal |

Inactive |

Inactivated 12 December

1945 |

-

- [210]

- 7th Infantry Division Band on the capital grounds of Seoul, Korea,

1945

-

- To replace the divisions on occupation

duty in Germany that were being inactivated, the US. European Command organized

the US. Constabulary. Heavily armed, lightly armored, and highly mobile, the

Constabulary served as an instrument of law enforcement, supporting civil

authority, quelling civil disorders, and providing a covering force to engage

a hostile enemy until the United States could deploy larger tactical units

overseas. The 1st and 4th Armored Divisions, both experienced in mobile warfare,

furnished many of the Constabulary's units.4

-

- Although the US. Army saw no action

in Korea during World War II, the 6th, 7th, and 40th Infantry Divisions

arrived there in September and October 1945 to occupy the southern portion

of the country and assist in the demobilization of the Japanese Army. An

agreement with the Soviet Union had divided the former Japanese colony at

the 38th Parallel. The Korean contingent for a short time remained at three

divisions but soon dropped to two, the 6th and 7th Infantry Divisions. Following

establishment of an independent South Korean government in 1948, the Far

East Command inactivated the 6th and moved the 7th to Japan, leaving only

a military advisory group in Korea.5

-

- Demobilization and the ensuing personnel

turbulence played havoc with the active divisions. During a twelve-month

period the 88th Infantry Division in Italy received 29,500 officers and

enlisted men and shipped out 18,500. The 1st Cavalry Division in Japan operated

at one-fourth of its authorized strength during

- [211]

- the first year on occupation duty,

and most replacements were teenaged recruits. Divisions in the United States

fared no better. The 3d Infantry Division was authorized approximately 65

percent of its wartime strength but fell well below that figure. Demobilization,

far from being orderly, became what General George C. Marshall described

as a "tidal wave" that completely disrupted the internal cohesion

of the Army.6

-

- As the nation demobilized, Congress

approved, with the consent of the Philippine government, the maintenance

of 50,000 Philippine Scouts (PS) as occupation forces for Japan. On 6 April

1946 Maj. Gen. Louis E. Hibbs, who had commanded the 63d Infantry Division

during the war, reorganized the Philippine Division, which had surrendered

on Bataan in 1942, as the 12th Infantry Division (PS). Unlike its predecessor,

the 12th's enlisted personnel were exclusively Philippine Scouts.7

-

- The War Department proposed to organize

a second Philippine Scout division, the 14th, but never did so. After a

short period President Harry S. Truman decided to disband all Philippine

Scout units, determining that they were not needed for duty in Japan. The

United States could not afford them, and he felt the Republic of the Philippines,

a sovereign nation, should not furnish mercenaries for the United States.

Therefore, the Far East Command inactivated the 12th Infantry Division (PS)

in 1947 and eventually inactivated or disbanded all Philippine Scout units.8

-

- Besides the requirement for occupation

forces, an urgent need existed for some combat-ready divisions in the United

States, where none had been maintained since February 1945. The War Department

scaled back its earlier estimate for "strategic" forces and decided

to maintain one airborne, one armored, and three infantry divisions, all

at 80 percent strength. Initially the department designated the force as

the Strategic Striking Force but soon renamed it the General Reserve, to

reflect its mission more adequately. But the General Reserve quickly felt

the effects of demobilization, and it was soon reduced to four divisions

the 82d Airborne, the 2d Armored, and the 2d and 3d Infantry Divisions.9

-

- Departing from its post World War

I policy, the War Department kept divisional units in the United States

concentrated on large posts to foster training and unit cohesion. However,

shortages in personnel, obsolete equipment, and insufficient maintenance

and training funds prevented the divisions from being combat effective.

By the winter of 1947-48 the General Reserve consisted of the airborne division

at Fort Bragg at near war strength, two half-strength infantry divisions,

one at Fort Campbell and the other at Fort Lewis, and the armored division

at Fort Hood with fewer than 2,500 men.10

-

- As many divisions were eliminated

from the active rolls, various divisional commanders jockeyed to have their

units retained in the active force. By what some thought was chicanery,

the 3d Infantry and 82d Airborne Divisions had replaced the 5th Infantry

and the 101st Airborne Divisions on the active rolls. These changes caused

considerable resentment within the ranks, and unit desig-

- [212]

- nations became a contentious issue

with many active duty personnel as well as veterans. Thus, the adjutant

general solicited recommendations from the commanders of Army Ground Forces

and the overseas theaters for divisional numbers to be represented in the

Regular Army. In the ensuing study, the adjutant general recommended the

numbers 1 through 10 and 24 and 25 for infantry divisions (the 10th Mountain

Division to be redesignated as the 10th Infantry Division); the numbers

1, 2, 3, and 4 for armored divisions (when elements of the 4th Armored Division

serving in the Constabulary were inactivated, they were to revert to divisional

units); and 82 and 101 for airborne divisions. The recommendations also

included the priority for the retention of divisions on the active rolls.11

-

- The study recommended that the 1st

Cavalry Division be inactivated upon completion of its occupation duties and

its elements retained as nondivisional units. Large horse units were not to

be included in the post World War II Army. Chief of Staff General Dwight D.

Eisenhower disagreed with the elimination of the division. Therefore, the

Army Staff reworked the list, designating the 1st Cavalry Division eighth

on the retention list for infantry (the division had been organized partially

under infantry and partially under cavalry tables during World

- War II) and recommending modification

of the unit's designation to show its character

as infantry. After examining several proposals, Eisenhower approved the name

"1st Cavalry Division (Infantry)." 12

-

- No change in the number of divisions

on active duty resulted from the study; it simply provided the nomenclature

for the Regular Army's divisional forces. Eventually the 1st Cavalry Division,

the 10th Mountain Division, and the Constabulary units conformed to these

decisions. Also, the 101st Airborne Division and the 10th and 25th Infantry

Divisions (Army of the United States units) and the 82d Airborne Division

(an Organized Reserve organization) were allotted to the Regular Army. 13

-

-

- With the nation victorious in war

and alone armed with the most awesome weapon known to man, the atomic bomb,

a lasting peace appeared at hand. Some military planners believed, however,

that the need for ground combat units remained unchanged. Planning for a

postwar conventional force had begun in 1943, and over the next three years

those plans, which included reserves, were debated in Congress and by the

War Department and state officials. 14

-

- When Maj. Gen. Ellard A. Walsh,

president of the National Guard Association, learned the staff was studying

a postwar reserve structure, he pressed for consideration of reserve officers'

views, petitioning Congress to ensure that the War Department establish

reserve affairs committees in agreement with the provisions of the National

Defense Act. In August 1944 Deputy Chief of Staff McNarney appointed a six-member

committee of Regular Army and National Guard officers to prepare policies

and regulations for the Guard. Then, in October, he authorized a

- [213]

- similar committee for the Organized

Reserves. He also arranged for joint meetings of the two groups where they

discussed matters common to both.15

-

- On 13 October 1945 the War Department

published a postwar policy statement for the entire Army. It called for

a ground military establishment consisting of the Regular Army, the National

Guard of the United States, and the Organized Reserve Corps, 16

which were to form a balanced force for peace and war. The Regular Army

was to retain only those units required for peacetime missions, which were

the same as those identified after World War I. The dual-mission Guard was

to furnish units needed immediately for war and to provide the states with

military resources to protect life and property and to preserve peace, order,

and the public safety. The Organized Reserve Corps was to supplement the

Regular Army and National Guard contributions sufficiently to meet any projected

mobilization requirements. 17

-

- After the policy statement was published,

the Army Staff prepared a postwar National Guard troop basis, which included

twenty-four divisions. It derived that number by counting the prewar eighteen

National Guard infantry and four National Guard cavalry divisions, the Americal

Division (which had been largely composed of Guard units), and the 42d Infantry

Division. Most soldiers considered the 42d, initially organized with state

troops in 1917, as a Guard unit. The fact that the new plan allowed each

of the forty-eight states to have at least one general officer also helped

earn its acceptance. In the end it was necessary to approve a 27-division

structure with 25 infantry divisions and 2 armored divisions to accommodate

the desires of all the states. During this process New York, for example,

successfully petitioned the War Department for the 42d Infantry Division.

When the allotment was completed, the Guard contained the 26th through 48th

and the 51st and 52d Infantry Divisions and the 49th and 50th Armored Divisions.

The number 39 was used for the first time since 1923. Although a 44th Infantry

Division had existed during the interwar years, the postwar 44th in Illinois

was a new unit, as were the 46th, 47th, 48th, 51st, and 52d Infantry Divisions

and 49th Armored Division. The 50th Armored Division replaced the 44th Infantry

Division in New Jersey. 18

-

- While the states and the War Department

settled troop basis issues, the National Guard Bureau changed the procedures

for organizing the units. In the past states had raised companies, forming

regimental headquarters only when sufficient companies existed to make a

regiment. Under the new regulations, divisional and regimental headquarters

were to be organized first, and they were to assist the division commander

in raising the smaller units. 19

-

- During the spring of 1946 the National

Guard Bureau surfaced the complex problem of how to preserve historical

continuity in the Guard units. In 1942 the divisions had been reorganized

from square to triangular units, which left them only vaguely resembling

the formations inducted into federal service in 1940 and 1941. Furthermore,

the expanded troop basis of 1946 compounded the problem by adding units

that had never before existed. To keep from losing the historical

- [214]

- link with the prewar units, some

dating as far back as 1636, the bureau and the Historical Section, Army

War College, reaffirmed an earlier policy validated between World Wars I

and II. Units were to perpetuate organizations that had been raised in the

same geographic areas, regardless of type or designation. For example, New

Jersey, which had supported part of the 44th Division before the war, now

supported the 50th Armored Division. Therefore most of its elements "inherited"

the history of the organic units of the old 44th, and elements of the new

44th perpetuated the history and traditions of former units in Illinois.20

-

- The command arrangement within the

multistate divisions presented another quandary. The War Department did

not rule on the question, but some states that shared a division developed

and signed formal command arrangement documents. For example, Florida, Georgia,

and South Carolina, states that contributed to the 48th and 51st Infantry

Divisions, contracted to rotate command of the units every five years.21

-

- After the state governors formally

notified the National Guard Bureau that they accepted the new troop allotments

(Table 18), the bureau authorized reorganization of the units with

100 percent of their officers and 80 percent of their enlisted personnel.

The first division granted federal recognition after World War II was the

45th Infantry Division from Oklahoma on 5 September 1946. Within one year

all Guard division headquarters had received federal recognition.22

-

- On Veterans Day 1946, at Arlington

National Cemetery, President Truman announced the return of the National

Guard colors and flags of those units that had served during the war. In

concurrent ceremonies in state capitals, forty-five governors received those

colors and flags. The other three states obtained their standards in separate

ceremonies. These actions did much to express the tie of the postwar National

Guard forces to prewar units.23

-

- The rebuilding of the Organized

Reserve Corps divisions posed some similar problems and others that were

unique to it. A tentative troop basis, prepared in March 1946 (after the

National Guard organizational structure had been presented to the states),

outlined 25 divisions-3 armored, 5 airborne, and 17 infantry. These divisions

and all other Organized Reserve Corps units were to be maintained in one

of three strength categories, labeled Class A, B, and C. Class A units were

divided into two groups, one for combat and one for service, and units were

to be at required table of organization strength; Class B units were to

have their full complement of officers and enlisted cadre strength; and

Class C were to have officers only. The troop basis listed nine divisions

as Class A, nine as Class B, and seven as Class C.24

-

- Maj. Gen. Milton A. Reckord, the

adjutant general of Maryland, and General Walsh of the National Guard Association

protested the provision for Class A divisions, whose cost, they believed,

would detract greatly from funds available to the Guard. They argued that

if Class A units were needed, they should be allotted to the Regular Army

or the National Guard, not to the Organized Reserve Corps, because these

units were augmentations to rather than essential components of

- [215]

- Location of National Guard Divisions

- Post-World War II

-

| Division |

States |

| 26th Infantry |

Massachusetts |

| 27th Infantry |

New York |

| 28th Infantry |

Pennsylvania |

| 29th Infantry |

Maryland and Virginia |

| 30th Infantry |

Tennessee and North

Carolina |

| 31st Infantry |

Alabama and Mississippi |

| 32d Infantry |

Wisconsin |

| 33d Infantry |

Illinois |

| 34th Infantry |

Iowa and Nebraska |

| 35th Infantry |

Kansas and Missouri |

| 36th Infantry |

Texas |

| 37th Infantry |

Ohio |

| 38th Infantry |

Indiana |

| 39th Infantry |

Arkansas and Louisiana |

| 40th Infantry |

California |

| 41st Infantry |

Washington and Oregon |

| 42d Infantry |

New York |

| 43d Infantry |

Connecticut, Rhode Island,

and Vermont |

| 44th Infantry |

Illinois |

| 45th Infantry |

Oklahoma |

| 46th Infantry |

Michigan |

| 47th Infantry |

Minnesota and North

Dakota |

| 48th Infantry |

Georgia |

| 49th Armored |

Texas |

| 49th Infantry* |

California |

| 50th Armored |

New Jersey |

| 51st Infantry |

Florida and South Carolina |

| 52d Infantry |

California |

-

- * The 52d Infantry was redesignated

the 49th Infantry in 1947.

-

- the immediate mobilization force.

Maj. Gen. Ray E. Porter, director of the Special Plans Division, supported

the Guard's view regarding funds and noted that facilities were not available

for use by Class A divisions. Furthermore, he believed the Organized Reserve

Corps divisions would compete with Guard formations for available personnel.

Porter therefore proposed reclassification of all Class A divisions as Class

B units. Eventually the War Department agreed and made the appropriate changes.25

-

- Although the dispute over Class

A units lasted several months, the War Department proceeded with the reorganization

of the Organized Reserve Corps

- [216]

- divisions during the summer of 1946.

That all divisions were to begin as Class C (officers only) units, progressing

to the other categories as men and equipment became available, undoubtedly

influenced the decision. Also, the War Department wanted to take advantage

of the pool of trained reserve officers and enlisted men from World War

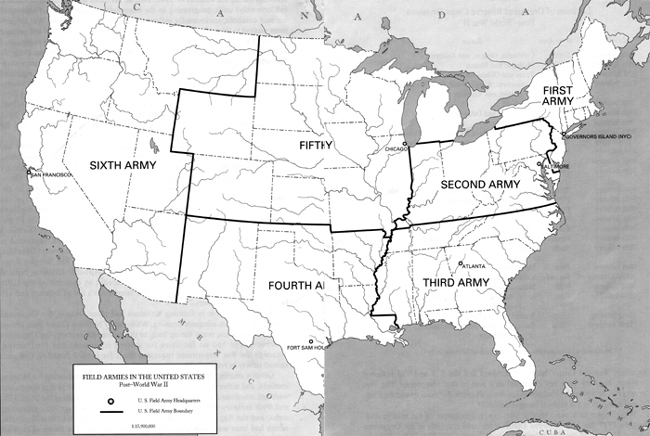

II. By that time Army Ground Forces had been reorganized as an army group

headquarters that commanded six geographic armies (Map 3). The armies

replaced the nine corps areas of the prewar era, and the army commanders

were tasked to organize and train both Regular Army and Organized Reserve

Corps units. The plan the army commanders received called for twenty-five

Organized Reserve Corps divisions the 19th, 21st, and 22d Armored Divisions;

the 15th, 84th, 98th, 99th, and 100th Airborne Divisions; and the 76th,

77th, 79th, 81st, 83d, 85th, 87th, 89th, 90th, 91st, 94th, 95th, 96th, 97th,

1024, 103d, and 104th Infantry Divisions. Demography served as the basic

tool for locating the units within the army areas, as after World War I.26

-

- The twenty-five reserve divisions

activated between September 1946 and November 1947 (Table 19) differed

somewhat from the original troop basis. The First Army declined to support

an airborne division, and the 98th Infantry Division replaced the 98th Airborne

Division. A note on the troop list nevertheless indicated that the unit

was to be reorganized and redesignated as an airborne unit upon mobilization

and was to train as such. After the change, the Organized Reserve Corps

had four airborne, three armored, and eighteen infantry divisions. The Second

Army insisted upon the number 80 for its airborne unit because the division

was to be raised in the prewar 80th Division's area, not that of the 99th.

Finally, the 103d Infantry Division, organized in 1921 in New Mexico, Colorado,

and Arizona, was moved to Iowa, Minnesota, South Dakota, and North Dakota

in the Fifth Army area. The Seventh Army (later replaced by Third Army),

allotted the 15th Airborne Division, refused the designation, and the adjutant

general replaced it by constituting the 108th Airborne Division, which fell

within that component's list of infantry and airborne divisional numbers.27

-

- A major problem in forming divisions

and other units in the Organized Reserve Corps was adequate housing. While

many National Guard units owned their own armories, some dating back to

the nineteenth century, the Organized Reserve Corps had no facilities for

storing equipment and for training. Although the War Department requested

funds for needed facilities, Congress moved slowly in response.28

-

- Given a smaller Organized Reserve

Corps troop basis that called for infantry, armored, and airborne divisions,

six prewar infantry divisions in that component were not reactivated in

the reserves. The War Department deleted the 86th, 97th, and 99th Infantry

Divisions when other divisions took over their recruiting areas, and the

Regular Army, as noted, retained the 82d and 101st Divisions, which had

been reorganized as airborne during the war. The future of the 88th Infantry

Division, still on occupation duty in Italy, remained unsettled. Within

the

- [217]

-

- [218-219]

- Location of Organized

Reserve Corps Divisions

- Post-World War II

-

| Division |

Army Area |

States |

| 13th Armored* |

Sixth |

California,

Oregon, and Arizona |

| 21st Armored |

Fifth |

Michigan

and Illinois |

| 22d Armored |

Fourth |

Texas and

Oklahoma |

| 76th Infantry |

First |

Connecticut,

Rhode Island, New Hampshire, Maine,

and Vermont |

| 77th Infantry |

First |

New York |

| 78th Infantry |

First |

New Jersey

and Delaware |

| 79th Infantry |

Second |

Pennsylvania |

| 80th Airborne |

Second |

Maryland,

Virginia, and District of Columbia |

| 81st Infantry |

Third |

Georgia,

North Carolina, and South Carolina |

| 83d Infantry |

Second |

Ohio |

| 84th Airborne |

Fifth |

Indiana |

| 85th Infantry |

Fifth |

Illinois,

Minnesota, South Dakota, and North Dakota |

| 87th Infantry |

Third |

Alabama,

Tennessee, Mississippi, and Florida |

| 89th Infantry |

Fifth |

Kansas,

Nebraska, Wyoming, and Colorado |

| 90th Infantry |

Fourth |

Texas |

| 91st Infantry |

Sixth |

California,

Oregon, and Washington |

| 94th Infantry |

First |

Massachusetts |

| 95th Infantry |

Fourth |

Oklahoma,

Arkansas, and Louisiana |

| 96th Infantry |

Sixth |

Montana,

Washington, Idaho, Nevada, and

Utah |

| 98th Infantry |

First |

New York |

| 100th Airborne |

Second |

Kentucky

and West Virginia |

| 102d Infantry |

Fifth |

Missouri

and Illinois |

| 103d Infantry |

Fifth |

Iowa, Minnesota,

South Dakota, and North

Dakota |

| 104th Infantry |

Sixth |

Washington

and Oregon |

| 108th Airborne |

Third |

Georgia,

Florida, North Carolina, and Alabama |

-

- * 13th Armored Division replaced the

19th Armored Division in 1947.

-

- Organized Reserve Corps' block of

numbers fell the 92d and 93d Infantry Divisions, but they were not classified

as a part of that component. The War Department, however, decided not to

maintain all-black divisions or use their traditional numbers in the postwar

reorganization.29

-

- Two changes took place shortly after

the reorganization of the reserve divisions. In 1947 the 13th Armored Division

replaced the 19th in the Organized Reserve Corps, and the 52d Infantry Division

became the 49th in the National

- [220]

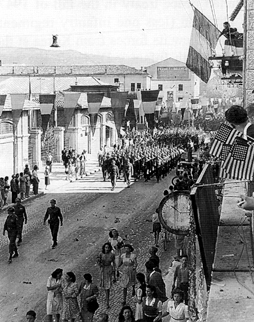

- 350th Infantry, 88th Infantry Division, parades in Gorizia, Italy,

1945

-

- Guard. Redesignation of the 52d

coincided with California's centennial celebration. The division's home

area covered the region where gold had been discovered in 1849, and the

state requested the name change to honor the "Forty-Niners" of

that era. The 13th replaced the 19th Armored Division, also at California's

bidding, because of the former unit's association with the state; the 13th

had served there during and after World War II.30

-

- The War Department tentatively planned

to organize the 106th Infantry Division in Puerto Rico using units from

all three components. The Regular Army and the National Guard were to furnish

the regimental combat teams and the Organized Reserve Corps the combat support

units. By early 1948 the combat elements had been organized, and the formation

of most other units had been authorized, including the headquarters company

of the division. The War Department determined, however, that the 106th

Infantry Division was not needed and never added it to the reserve troop

list. The division headquarters company was inactivated in 1950, but most

other units remained active as nondivisional organizations. 31

-

- Manning reserve units proved to

be a difficult task. Initially the Army planned that the rank and file of

the units would be men who had undergone universal military training in

centers operated by Regular Army divisions. With public sentiment opposed

to universal military training, Congress declined to

- [221]

- Divisions Designated

as Training Centers, 1947-50

-

| Division |

Location |

Dates |

| 3d Armored |

Fort Knox, Ky. |

July 1947-Active |

| 4th Infantry |

Fort Ord, Calif |

July 1947-Active |

| 5th Armored |

Camp Chaffee, Ark. |

July 1948-February 1950 |

| 5th Infantry |

Fort Jackson, S.C. |

July 1947-April 1950 |

| 9th Infantry |

Fort Dix, N.J. |

July 1947-Active |

| 10th Infantry |

Fort Riley, Kans. |

July 1948-Active |

| 17th Airborne |

Camp Pickett, Va. |

July 1948-June 1949 |

| 101st Airborne |

Camp Breckinridge, Ky. |

July 1948-May 1949 |

-

- approve it. The reserves therefore

relied upon volunteers who had prior service, the Reserve Officer Training

Corps (ROTC), and personnel who had to complete a commitment after serving

on active duty in conjunction with the draft, which was reenacted in 1948.

That year to stimulate interest in the Organized Reserve Corps, Congress

authorized pay for inactive duty training. With a small portion of the postwar

Army dependent upon the draft, it generated few reservists for the National

Guard and the Organized Reserve Corps, and those units fell considerably

below full strength.32

-

- Although the War Department did

not use divisions as a part of a universal military training program, it

decided to use divisional designations for replacement training centers

in the summer of 1947. The 3d Armored Division and the 4th, 5th, and 9th

Infantry Divisions were activated and their elements reorganized for that

purpose. The cadres who trained the recruits responded favorably to the

use of divisions as a means of building esprit since they wore the divisional

shoulder sleeve insignia, and the recruits were inspired by the accomplishments

of historic units. The Army authorized more training centers divisional

designations in the summer of 1948 (Table 20). As the training load

fluctuated, so did the number of "divisional" training centers,

which stood at four two years later.33

-

-

- In reorganizing the postwar divisions,

the Army used World War II tables of organization and equipment, but studies

of combat experience that were under way portended revisions. The U.S. European

Theater of Operations established the General Board, consisting of many

committees, to analyze the strategy, tactics, and administration of theater

forces. A committee headed by Brig. Gen. A. Franklin Kibler, formerly the

G-3, 12th Army Group, examined the requirements for various types of divisions.

After weighing divisional strengths and weaknesses and considering new combinations

of arms and services, the committee recom-

- [222]

- mended the retention of infantry,

armored, and airborne divisions. The committee concluded that a standard

infantry division could accomplish missions that might require either light

or mountain troops, and that therefore such special divisions were unnecessary.

However, it also recommended that the Army maintain at least one horse cavalry

division to guarantee that a few officers and enlisted men would continue

to be trained as mounted troops. No other postwar study urged the retention

of the cavalry division, and, as noted, the War Department rejected any

large horse units for the future.34

-

- Other General Board committees examined

the requirements for each type of division. The committee for the infantry

division surfaced many of the same requirements identified previously in

the spring of 1945 and recommended a unit of 20,578 men. Additional men

were needed in the infantry regiment to provide communications, intelligence,

reconnaissance, and administration, and improved weapons were required for

cannon and antitank companies. The committee proposed the development of

a low silhouette 105-mm. self-propelled howitzer, but until its adoption

the cannon company was to use a 105-mm. howitzer mounted on a medium tank.

To arm the antitank company, the planners proposed either a self-propelled

antitank gun or a medium tank, with most favoring the latter. Some committee

members advocated removing the antitank company from the infantry regiment

and adding a three-battalion tank regiment to the division. Because of the

size and complexity of the infantry regiment, the committee urged that its

commander be a brigadier general.35

-

- Cavalry and field artillery arms

were also expanded within the infantry division. To ensure adequate intelligence

and counterreconnaissance (i.e., security), a divisional cavalry squadron

replaced the troop. Because the division often lacked sufficient field artillery,

the committee recommended adding a towed 155-mm. howitzer battalion for

a total of two 155-mm. howitzer battalions and three self-propelled 105-mm.

howitzer battalions. All fifteen artillery batteries were to have six pieces

each.36

-

- Divisional combat and combat service

support also grew. An antiaircraft artillery battalion was added for air

defense, an engineer regiment replaced the battalion, and a military police

company supplanted the platoon. Given the increases in the arms and combat

support elements, the division needed greater maintenance and quartermaster

resources, and the committee urged expansion of these units to battalions.

Finally, a new reinforcement battalion was suggested to process and forward

replacements. In sum, the General Board committee preserved the division's

three regimental combat teams used during the war, but added or enlarged

units that had been organic or habitually attached and organizations to

service them.37

-

- The committee analyzing the airborne

division concluded it should have the same organization and equipment as

the infantry division, along with augmentations needed to perform its airborne

missions. Two sets of equipment were thus recommended for the division,

a lightweight set for airborne assaults and a

- [223]

- heavy set for sustained ground combat.

All divisional elements were to be trained in parachute, glider, and air

transport techniques, making all divisional elements airborne units.38

-

- The General Board's third committee

on divisional organization reviewed the armored division. Examination of

both the early heavy armored division and the lighter variant introduced

in 1943 revealed defects that had been corrected by attaching units. Using

the 1943 division as a base, the committee added a fourth 105-mm. howitzer

battalion, an antiaircraft artillery battalion, and a tank destroyer battalion.

During combat operations these units had been added to the division, as

was an infantry battalion or regiment, when available. The committee viewed

the combat command as a major weakness because it did not have assigned

units, a violation of unity of command. Furthermore, both types of armored

divisions had only two authorized combat commands, but in combat they normally

had operated with three. To provide the third command in the heavy division,

the headquarters and headquarters company of the armored infantry regiment

had been organized provisionally as a combat command headquarters, and in

the light division a headquarters and headquarters company of an armored

group augmented the reserve command. The committee recommended that the

combat commands be replaced with three regiments, each made up of one tank

and two armored rifle battalions, and that brigadier generals command the

regiments. Upon reflection, the committee omitted one unit previously attached

to the division, the tank destroyer battalion, because of the wartime trend

toward arming American tanks with high-velocity weapons capable of destroying

enemy armor, an evolution that made the lightly armored tank destroyer redundant.

The strength of the projected armored division rose to 19,377 officers and

enlisted men, nearly double the size of light armored divisions of 1943.39

-

- The Army Staff received the reports

from the General Board and passed them along to the Army Ground Forces.

In September 1945 that command began preparing new tables of organization

for the postwar Army, but General Devers, commander of Army Ground Forces,

refrained from making any decisions about divisional organization pending

review of the board's findings and the recommendations of infantry and armored

conferences being held in the spring of the following year. In July 1946

he finally forwarded proposals to the General Staff for new infantry and

armored divisions that combined recommendations of the committees and of

the conferences. The new tables for the infantry division were similar to

those developed in 1945 when restrictions were lifted on their manning.

The armored division retained its 1943 configuration with augmentations

to correct organizational deficiencies. Devers believed these divisions

would meet the Army's needs for versatile, mobile, hard-hitting units. Despite

the availability of the atomic bomb, the nature of ground combat had not

changed. The infantry division was capable of operating in jungle, arctic,

desert, and mountain terrain or on plains; the armored division remained

a highly mobile unit to break through a

- [224]

- line or exploit success on the battlefield.

He questioned, however, the appropriate rank for commanders of the new infantry

combat teams (formerly infantry regiments) in the infantry division and

combat commands in the armored division-a colonel or brigadier general.40

-

- Eisenhower sent the divisional proposals

to senior officers, including his own advisory group, for comment.41

He was concerned that units were too large, possessing everything they might

need under almost any condition, violating the principles of flexibility

and economy of force followed during the war. He also requested the officers'

views as to whether the Army should break each division into three smaller

units, and if so whether the infantry regiment should be renamed an infantry

combat team.42

-

- The advisory group concurred with

the Army Ground Forces proposals. It did not believe that divisions had

too many people and too much equipment; they had only those units habitually

attached during combat. The group did not fear a diminution of morale because

the infantry regiment was to be known by another name. Moreover, it supported

the rank of brigadier general for the commanders of infantry combat teams

in the infantry division and combat commands in the armored division because

it was commensurate with the assigned responsibilities.43

-

- Among the other general officers

who commented on the divisions, General Omar N. Bradley, head of the Veterans

Administration, wanted the staff to develop a division organization that

combined aspects of both infantry and armored divisions. For the time being,

however, he deemed the proposed units sound. Lt. Gens. Walton H. Walker

and Oscar W Griswold, the Fifth and Seventh Army commanders, also endorsed

the organizational proposals but disagreed on the appropriate rank for combat

command and infantry combat team leaders. Eisenhower approved the divisions

on 21 November 1946, but disapproved the change in general officer positions

and the new name for infantry units. The following month Army Ground Forces

prepared draft tables of organization for a 17,000-man infantry division

and a 15,000-man armored division.44

-

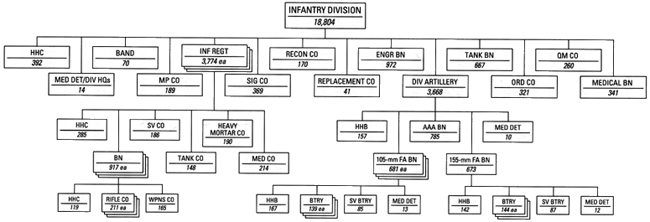

- In 1948, when the Department of

the Army 45

finally published new tables for the infantry division, it authorized 18,804

officers and enlisted men (Chat 23). The division, however, remained

basically the same as approved by Eisenhower. The ratio of combat to service

troops was 4 to 1, and a 50 percent increase in firepower was attained by

merely authorizing each field artillery firing battery six pieces.46

-

- Some changes made between the time

Eisenhower approved the division and publication of its tables, however,

are noteworthy. In the medical service, a medical company replaced the attached

medical detachment in each infantry regiment, and artillery, engineer, and

tank battalions fielded organic medical detachments as did the division

headquarters. The medical battalion was to provide only clearing and ambulance

services. The reconnaissance troop was redesignated as a reconnaissance

company to eliminate the term "troop" from the Army's nomenclature

except for cavalry and constabulary units. At the insistence of officers

who attended an Infantry conference in 1946 that discussed the status of

the arm,

- [225]

- Infantry Division, 7 July 1948

-

-

- [226]

- Army Ground Forces added a replacement

company to receive and process incoming personnel. One unit that did not survive

the postwar revision was headquarters, special troops, because it was deemed

unnecessary. A major general continued to command the division, and it was

authorized two brigadier generals, the assistant division commander and the

artillery commander. Regimental commanders remained colonels.47

-

- A controversial area that affected

development of the tables for the infantry division was the postwar battlefield's

greater depth and breadth, which increased the difficulty of conducting

reconnaissance and intelligence collection. Ten airplanes had been assigned

to the division artillery in 1943 and an additional three to the infantry

regiments in 1945. In 1946 Army Ground Forces proposed assigning aircraft

to the division headquarters and to tank and engineer battalions. The Army

Staff endorsed the additional planes but wanted them pooled in one unit,

except for those in the division artillery. Opposition to that proposal

came from the Army Air Forces, which argued that all air units came under

their jurisdiction.48

The Army countered that the National Security Act of 1947 authorized it

to organize, train, and equip aviation resources for prompt and sustained

combat incident to operations on land.49

Nevertheless the tables provided no aviation unit, but ten planes were assigned

to the division artillery and eight to the division headquarters company.50

-

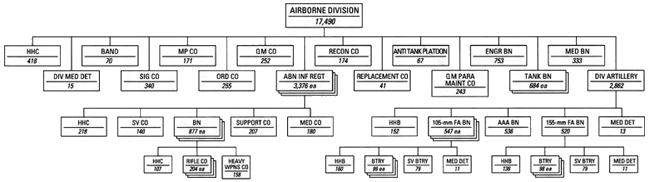

- The postwar armored division (Chart

24) retained the flexible command structure of the 1943 organization

with three medium tank battalions, three armored infantry battalions, and

three 105-mm. howitzer battalions, along with some significant changes.

Army Ground Forces made the reserve command identical to the two existing

combat commands, replaced the attached tank destroyer battalion with a heavy

tank battalion, and added an antiaircraft artillery battalion, and a replacement

company. Paralleling the infantry division, the military police platoon

was expanded to a company and the reconnaissance squadron was redesignated

as a battalion. A 155-mm. self-propelled howitzer battalion was added to

give the division more general support fire, and, in the division trains,

the quartermaster supply battalion, eliminated in 1943, was restored to

transport fuel, provide bath and laundry facilities, and assume graves registration

duties. Besides the field artillery's aircraft, ten planes were placed in

the division headquarters company to serve division and combat command headquarters,

the engineer battalion, and the reconnaissance battalion. The number of

general officers was increased from two to three, a division commander and

two combat command commanders. The commanders of the reserve command and

the division artillery remained colonel billets.51

-

- Infantry and armored divisions were

reorganized between the fall of 1948 and the end of 1949. Most divisions,

however, never attained their table of organization strengths prior to the

Korean War. Only the 1st Infantry Division in Germany was authorized at

full strength. Strengths in other Regular Army divisions fell between 55

and 80 percent. In the National Guard the strength of the divisional elements

varied, with some units being cut by individuals, by crews

- [227]

- Armored Division, 8 October 1948

-

-

- [228]

- (the field artillery batteries had

four rather than six gun crews), or by companies (the engineer battalion had

three instead of four line companies and there was no divisional replacement

company). Strengths in the Guard units ranged between 5,000 and 10,500 men

of all ranks. The divisions of the Organized Reserve Corps remained either

Class B or Class C units.52

-

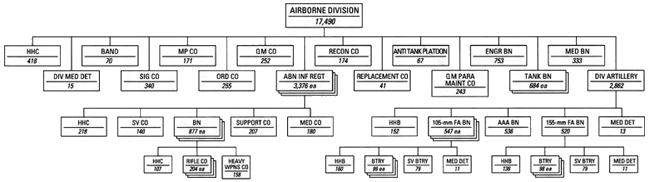

- The development of the postwar airborne

division took almost two years longer than infantry and armored divisions.

On 16 August 1946 Army Ground Forces forwarded to the General Staff an outline

for an airborne division. It was an infantry division with the addition

of a pathfinder platoon and a parachute maintenance company. The division

had approximately 19,000 jump-qualified officers and enlisted men and two

sets of equipment, one for air assault and the other for sustained combat.

Eisenhower rejected the proposal because the unit could not be air-transported.

He directed Army Ground Forces to prepare an organization that could be

moved by existing aircraft. Eisenhower also rejected the resulting proposal,

but a third idea developed by the Organizational and Training Division of

the General Staff won acceptance. The staff proposed an airborne division

with two categories of units, organic elements that could be airlifted and

attached ground units that were to link up with them. To make the unit air-transportable,

the staff eliminated heavy mortars and tanks from infantry regiments and

restricted the number of howitzers in field artillery batteries to four.

The attached units included two heavy tank battalions, a 155-mm. howitzer

battalion, a reconnaissance company, a medium maintenance company, and a

quartermaster company, which totaled 2,580 officers and enlisted men. Those

units along with the division's organic elements, which numbered 16,470,

made the division's size approximately the same as the Army Ground Forces

proposa1.53

-

- With the proposed airborne division

attempting to meet two competing needs, strategic mobility and tactical

sustainment, the General Staff decided to test it. The 82d Airborne Division

(less one regimental combat team at Fort Benning) adopted the new structure

on 1 January 1948. After the test, Army Field Forces (AFF), the successor

of Army Ground Forces, recommended organizing the airborne division in the

same manner as an infantry division. As organized for the test, the airborne

division was not air-transportable. The Army Staff, nevertheless, still

sought a large airborne unit for strategic mobility. Therefore, on 4 May

1949 the new Chief of Staff, General Omar Bradley, directed that the attached

combat elements be made organic to the division and that only 11,000 of

its 17,500 men be airborne qualified. The Department of the Army published

new tables (Chart 25) mirroring these decisions on 1 April 1950.

Reorganization of Regular Army and Organized Reserve Corps airborne divisions

followed shortly thereafter. 54

-

-

- While the Army developed and reorganized

its postwar divisions, it continued to maintain and redeploy its existing

forces to meet changing international

- [229]

- Airborne Division, 1 April 1950

-

-

- [230]

-

- A final parade in Gorizia, before the 88th Division departs, 1947;

below, 82d Airborne Division troops at the New York City victory parade,

1946.

-

-

- [231]

- situations. With the ratification

of the Italian peace treaty in the fall of 1947, the Army inactivated the

88th Infantry Division (less one infantry regiment, which remained in Trieste)

and, as noted, withdrew its forces from Korea at the end of 1948. To make

room in Japan for the 7th Infantry Division, the 11th Airborne Division, which

had been stationed there since 1945, redeployed to Fort Campbell, Kentucky,

where it was reorganized with only two of its three regimental combat teams.

The reduction of forces in Korea also resulted in the inactivation of the

6th Infantry Division.55

-

- Four years after the end of World

War II the number of Regular Army divisions had fallen to ten. Overseas

the 1st Infantry Division was scattered among installations in Germany,

while the 1st Cavalry Division and the 7th, 24th, and 25th Infantry Divisions

were stationed throughout Japan. In the United States the 2d Armored Division

was split between Camp (later Fort) Hood, Texas, and Fort Sill, Oklahoma.

The 2d Infantry Division was based at Fort Lewis, Washington; the 3d Infantry

Division at Fort Benning, Georgia, and Fort Devens, Massachusetts; the 11th

Airborne Division (less one inactive regimental combat team) at Fort Campbell,

Kentucky; and the 82d Airborne Division at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. The

twenty-five Organized Reserve Corps and twenty-seven National Guard divisions

were at various levels of readiness.

-

- Initially overwhelmed by the tidal

wave of demobilization after World War II, the Army had struggled to rebuild

both Regular Army and reserve divisions during the late 1940s. Its new divisional

structures were based on combat experiences during the war, under the assumption

that atomic weapons would not alter the nature of ground combat. Units previously

attached to divisions from higher headquarters during combat were made organic

to divisions, which also received additional firepower. Although the postwar

divisions of the era were not fully prepared for combat because they were

not properly manned and equipped, they nonetheless represented an unprecedented

peacetime force in the Army of the United States, reflecting the new Soviet-American

tensions.

- [232]

Endnotes

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

page created 29 June 2001

Return to the

Table of Contents

-