-

-

- In the late summer and early fall

of 1942, while preparing Task Force "A" to participate in Operation

TORCH, the invasion of North Africa, trained soldiers were still extremely

scarce. To fill the task force, the War Department deferred reorganizing

and filling the 97th Infantry Division, the last of the Organized Reserve

divisions to enter active military service, and reduced three partially

trained divisions to less than 50 percent of their authorized strengths.

To avoid stripping divisions again and disturbing their training, the War

Department designated the 76th and 78th Infantry Divisions as replacement

units to receive, train, and hold men until needed. The divisions served

in that capacity from October 1942 to March 1943, when replacement depots

took over. Both divisions, refilled, then began their combat training program

anew.2

- [179]

- In late 1942 the War Department

selected the 7th Motorized Division to be part of the assault forces to

be used to drive the Japanese from the Aleutian Islands. In spite of growing

doubts by Army Ground Forces about the usefulness of fully motorized divisions,

the division was chosen because of its high state of readiness. Furthermore,

it was located near Fort Ord, California, an amphibious training site, and

could conveniently undergo the training required for the operation. On 1

January 1943 the 7th Motorized Division reverted to a standard infantry

division.3

-

- Besides the shortage of trained

manpower, the nation also faced a severe shortage of ships large enough

to transport divisions to the combat theaters. For this and other military

and political reasons, plans for an early invasion of Europe across the

English Channel were postponed. Also, the expansion and deployment of Army

Service Forces and Army Air Forces units placed heavy demands on available

shipping, while the success of German submarines off the Eastern Seaboard

of the United States made that shortage of tonnage even more acute. Finally,

the demands of the hard-pressed Pacific theaters put an unprecedented strain

on shipping facilities. Therefore, from October 1942 to March 1943 no division

departed the United States, and from March to November 1943 only eleven

went overseas.4

-

- In October 1942, acting to alleviate

the growing shipping problem, Marshall directed Army Ground Forces, Army

Air Forces, and Army Service Forces to eliminate unnecessary vehicles and

excess noncombatants. He sought a 15 percent reduction in personnel and

a 20 percent reduction in vehicles. In particular, he deemed the requirements

for divisional transportation in the tables of organization and equipment

to be extravagant because they represented what division commanders asked

for rather than what they actually needed.5

-

- To accomplish these objectives,

McNair established the Army Ground Forces Reduction Board to review all

units under his control. Two principles, streamlining and pooling, guided

the work. The former limited a unit to what it needed on a daily basis,

while the latter gathered at corps 6

or army levels resources that were believed to be only occasionally required.

Pooling was derived from the assumption that a division would be usually

assigned to a corps or an army. 7

-

- After the Reduction Board concluded

its work on the infantry division in March 1943, 2,102 officers and enlisted

men and 509 vehicles were stripped from the divisional tables of organization.

The scalpel slashed most divisional elements. The cuts eliminated 363 men

and 56 vehicles from the infantry regiment, with the cannon company deleted

entirely. The regiment retained six 105mm. towed howitzers, which required

less shipping space than 75-mm. self-propelled guns, used less gasoline,

and did less damage to light bridging. These were placed in the regimental

headquarters company. The number of automatic rifles was pruned from 189

to 81, but the introduction of the new 2.36-inch rocket launchers (bazookas)

provided powerful antitank and antipillbox resources that required no designated

operator in the regiment. Reductions in medical, commu-

- [180]

- General McNair

-

- nication, and service personnel

accounted for most of the other regimental personnel losses. 8

-

- The board carved 475 men and 95

trucks from the division artillery. Firepower did not decline since the

number of artillery pieces remained at twelve 155-mm. and thirty-six 105-mm.

howitzers. The headquarters and service batteries were combined, and antitank

and antiaircraft platoons were eliminated. An antitank capability remained

with the addition of 166 bazookas. To save personnel spaces, the number

of truck drivers, mechanics, cooks, and orderlies was reduced. 9

-

- The board provided for the return

of the airplane to the infantry division, a step that reflected the expanded

width and depth of the battlefield. The aero squadron had been eliminated

from all divisions by 1940, but field artillery officers continued to request

their own aircraft to guide counterbattery and indirect fire. In 1941 and

1942 the field artillery experimented with light planes, and on 6 June 1942

two light observation aircraft were added to each field artillery battalion

and two to the headquarters of the division artillery. The board's decision

formalized these additions.10

-

- Divisional combat support and service

support units were severely cut. The engineer battalion and signal company

each lost about 100 men, mostly because certain bridging equipment was taken

from the engineer battalion and the radio intelligence platoon was detached

from the signal company. Both functions moved to army level. The quartermaster

company lost about 150 men, but the number of trucks remained approximately

the same. No basic changes took place in the medical battalion, ordnance

company, or military police platoon. 11

-

- The board also believed that the

division headquarters and its headquarters company had grown too large.

To reduce the size of the headquarters company, its strength was cut almost

in half by eliminating the defense platoon and some vehicles, drivers, and

orderlies. The band assumed the mission of protecting the divisional headquarters

as an additional duty. Divisional staff sections remained the same, but

the board cut some assistant staff officers and enlisted men. Total reductions

in the division represented a 13.5 percent decrease in all ranks and 23

percent in vehicles.12

-

- Marshall tentatively approved the

new division but directed that its tables of organization be sent to the

theater commanders for comment. To sell the new

- [181]

- structure, General McNair and Maj.

Gen. Idwal Edwards, Assistant Chief of Staff, G-3, went to North Africa, where

they found no support. The division and corps commanders in the combat zone

rejected the cuts on the grounds that the division had already been reduced

to the lowest acceptable minimum.13

-

- With shipping and manpower shortages

still severe, Edwards' staff prepared another set of tables for the infantry

division that was a compromise between the Army Ground Forces proposal and

the desires of the overseas division and corps commanders. The new division

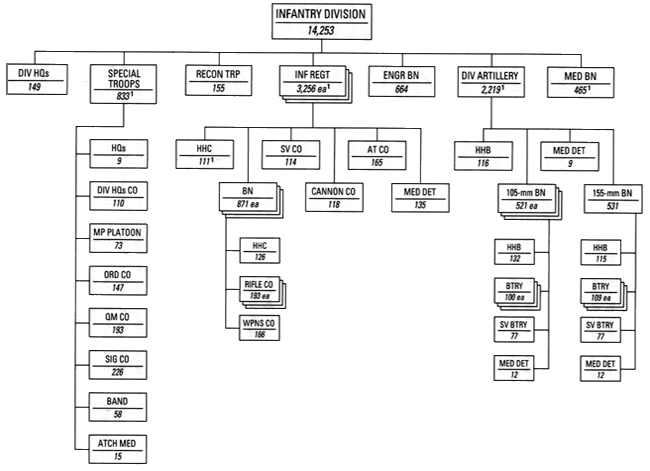

had 14,253 officers and enlisted men (Chart 19). Its combat support

and combat service elements remained about the same as those proposed by

the Reduction Board. To satisfy division and corps commanders in North Africa,

cannon companies were restored to the infantry regiments and service batteries

to the field artillery battalions. The 2.36-inch rocket launchers were retained

as antitank weapons, but 57-mm. antitank guns replaced the 37mm. guns. In

the division headquarters company the defense platoon reappeared, as did

the service platoon in the quartermaster company. Finally, Edwards' staff

added a new unit-headquarters, special troops-which provided administrative

support to the reconnaissance troop; to the signal, ordnance, and quartermaster

companies; and to the military police platoon. As for vehicles, the new

compromise organization had 2,012, almost the same as in the 1942 tables.14

-

- In January 1943 the Reduction Board

turned its attention to the motorized division concept. Several alternatives

had always existed. Since the motorized and infantry divisions had similar

organizations, the latter could simply be augmented as needed with 2-1/2-ton

trucks, permitting the simultaneous movement of all divisional elements.

Another option was to "armorize" the organization by equipping

it with tanks, armored personnel carriers, and self-propelled artillery.

McNair recommended to the Army Staff the reorganization of all motorized

divisions as standard infantry divisions, except for the 4th, which was

to be equipped with armored personnel carriers. The staff supported McNair's

recommendation.15

-

- On 12 March 1943 the Acting Chief

of Staff, General Joseph T. McNarney, approved replacing motorized divisions

with infantry divisions. He also approved the activation of additional truck

companies organized with black soldiers to motorize the infantry division

when necessary. The 4th Motorized Division, however, was to remain intact

pending its possible use overseas. Also, the armored division was to be

reorganized to achieve a better balance between infantry and armor elements.

The following May the 6th, 8th, and 90th Motorized Divisions were reorganized

as infantry divisions. Because the revised structure of the infantry division

was not settled, the divisions adopted and retrained under the 1942 infantry

division tables.16

-

- After the March decision, none of

the overseas commanders wanted the 4th Motorized Division because they thought

it would make inordinate demands on critical shipping space and the already

limited supply of tires and gasoline. The tires for a motorized division's

vehicles alone required 318 tons of rubber com-

- [182]

- Infantry Divisions, 15 July 1943

-

- 1 Includes chaplains.

-

- [183]

- pared to 166 tons for those in the

infantry division. Besides, the 4th was the only motorized division authorized

a full complement of equipment plus additional personnel and equipment to

constitute a special task force. Its potential punch in combat, however, did

not appear to justify the costs of shipping and logistical support. On 1 August

1943 the 4th reverted to the standard infantry division structure.17

-

- The organization of the armored

division had been in question for several months because of the imbalance

between armor and infantry forces. Some options existed for improvement.

Lt. Gen. Jacob L. Devers, Chief of the Armored Force, wanted to obtain a

better balance at corps level by having one motorized and two armored divisions

in a corps and by "armorizing" the motorized division.18

McNair believed that the armored division was "so fat there is no place

to begin." 19

He wanted either to increase the infantry or reduce the armor in the existing

division, changes that would result in a sweeping reorganization of the

unit. 20

-

- Eventually McNair directed the Reduction

Board to cut the divisional armor, believing the use of tanks had changed

since 1940. Both the British and the Germans had successfully used a division

that fielded fewer tanks than the American armored division. The armored

division was not free to roam at will, as first envisioned, because of improvements

in antitank weapons. McNair saw it as a unit of opportunity to exploit a

breakthrough, to take part in a pursuit, or to cover a withdrawal-all former

cavalry missions. Therefore, the armored division could be smaller. Furthermore,

McNair saw the need for fewer armored divisions in the total force, and

with fewer armored divisions more separate tank battalions, which were needed

to support infantry divisions, could be organized. 21

-

- Combat-experienced officers in the

North African theater opposed a major reorganization of the armored division.

In March 1943 the Fifth Army convened a review board, chaired by Maj. Gen.

Ernest N. Harmon, the commander of the 2d Armored Division. The board recommended

retention of the existing division structure with the addition of more infantry

and the assignment of tank destroyer and antiaircraft artillery battalions.

To simplify logistical and maintenance operations, the board wanted to reduce

the types of vehicles within the division, recommending that motorcycles

and amphibious trucks be replaced with 1/4-ton trucks and that obsolete

tanks be removed. Since the 1st Armored Division had been used in piecemeal

fashion on the Tunisian front and the 2d Armored Division was the only such

division to gain experience as a divisional organization, the board believed

that a major reorganization of the armored division was premature.22

-

- After months of study and discussion,

the War Department rejected the field recommendations and on 15 September

1943 published new armored division tables of organization that followed

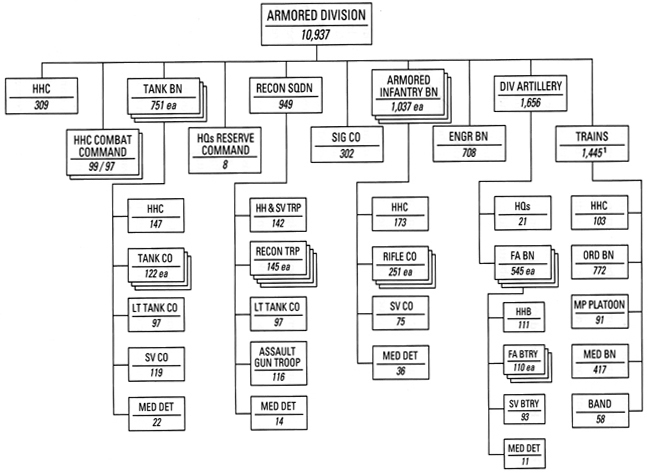

McNair's ideas (Chart 20). Three tank and three armored infantry

battalions replaced the armored and infantry regiments. Each tank battalion

included one light and three medium tank companies, and the

- [184]

- armored infantry battalion had three

line companies. For self-sufficiency, infantry and tank battalions each

had a service company that assumed many of the functions of the former regimental

headquarters and service companies and rendered some maintenance. No basic

change took place in the division's three field artillery battalions but,

as in the infantry division, the tables provided for liaison aircraft for

that arm. The results reduced the variety of vehicles. No additional organic

antitank or antiaircraft artillery battalions were included, for Army Ground

Forces believed that the divisions had sufficient antitank and antiaircraft

resources within their infantry, armor, and field artillery units. Besides,

the command felt the divisions could obtain additional antitank and antiaircraft

artillery resources from pools of such units at higher echelons.23

-

- The armored division continued to

field two combat commands as task force headquarters, which were to be used

to build flexible fighting teams of armor, infantry, and artillery with

support appropriate for the tactical requirements. A brigadier general led

one command and a colonel the other. The Reduction Board gave no explanation

for this curious rank arrangement. Undoubtedly one of the billets permitted

the assignment of a second general officer to the division to replace the

assistant division commander, whose slot had been eliminated. The reserve

command, a new organization led by an infantry colonel with a small staff,

served to clarify command and control in the division's rear area. In the

past the reserve commander had been the senior officer among those units.24

-

- The tables made substantial changes

in the armored division's combat support and combat service support arena.

The engineer battalion lost its bridge company (higher headquarters were

to supply bridging equipment) and the number of engineer line companies

fell from four to three. To compensate for the removal of reconnaissance

elements from tank and infantry units, the reconnaissance squadron included

a troop for each of the combat commands. In addition, the squadron had two

reconnaissance troops for divisional missions, an assault gun troop of four

platoons (one for each reconnaissance troop), and a light tank company.

The division trains comprised only medical and maintenance battalions, the

supply battalion having been eliminated. Each unit was made responsible

for its own resupply. Also, the divisional supply company was discarded

and its functions divided between the headquarters company of the division

and the headquarters company of the trains. These changes pared the division's

strength from 14,630 men to 10,937, slashed the number of tanks from 360

to 263, reduced the variety of vehicles to ease repair problems, and eliminated

the maintenance-prone motorcycles.25

-

- The War Department on 16 October

1943 summarized why the reorganizing of divisions and other units was necessary

in Circular 256. It cited the need to secure the maximum use of available

manpower, to permit transport overseas of the maximum amount of fighting

power, and to provide greater flexibility in organization in keeping with

the principle of economy of force and massing of military strength at the

decisive point. In addition, the reorganization was to reduce headquarters

and other noncombatants in order that command function

- [185]

- Armored Division, 15 September 1943

-

- 1 Includes chaplains

-

- [186]

- might keep pace with modern communication

and transport facilities and to provide commanders with the greatest possible

amount of offensive power through reduction in passive defensive elements.26

-

- Reorganization of infantry and armored

divisions began shortly after publication of the new tables. Infantry and

armored divisions, including those most recently activated in the United

States, adopted the new organizations between 1 August and 11 November 1943.

Overseas commands reorganized their infantry divisions as soon as possible

but had the authority to delay the changes if units were under alert, warning,

or movement orders or if they were engaged in maneuvers or active operations

against an enemy. The divisions needed time to retrain. Except for the 3d

and 34th Infantry Divisions, the eight infantry divisions in the European

and Mediterranean theaters were reorganized by the beginning of the new

year. The 34th came under the tables immediately prior to its participation

in the Anzio campaign in March 1944 and the 3d after Rome fell in June.

Of the twelve infantry divisions in the Pacific theater, eight were converted

by the beginning of 1944 and the remaining four by the following August.27

-

- Reorganization of the three overseas

armored divisions followed a somewhat different course. The 1st Armored

Division adopted the new structure while in a rest and training area in

Italy in 1944. The 2d and 3d Armored Divisions retained the 1942 configuration

throughout the war. During the fall of 1943 the commander of the European

Theater of Operations, General Devers, who had been a leading spokesman

for the heavy armored division decided that the war was too advanced to

permit changes in those units.28

-

- When the divisions in the Pacific

adopted the new tables, MacArthur restructured the Americal Division to

conform to other infantry divisions. On 1 May 1943 he placed it under the

tables prepared by the Reduction Board, the only division to use them, but

in September it was reorganized under the 15 July structure. Because of

the unit's widely acclaimed combat record, which included a Presidential

Citation (Navy) for its elements' service on Guadalcanal, the War Department

retained its name rather than give it a numerical designation.29

-

-

- Early in 1943 Army Ground Forces

developed a new type of unit, the light division, which the Operations Division

of the Army Staff had suggested earlier as a possibility for the Pacific

theater. Planners thought such a division could function in a variety of

combat conditions, such as jungles and mountains, simply by varying the

unit's mode of transportation. Initially, McNair, who disliked special units,

opposed the idea because of the unique training it required. Given the shortage

of shipping in the fall of that year, the Operations Division again put

forth the proposal. By this time planners had extended the idea to include

amphibious operations. When preparing for the invasion of North Africa,

the Solomon Islands, and New Guinea, infantry divisions had to be reorganized,

- [187]

- reequipped, and retrained to make

assault landings. In addition, a light division structure also seemed appropriate

for the airborne division.30

-

- On 17 January 1943 McNair appointed

Col. Michael Buckley from the Army Ground Forces G-3 section as chairman

of a committee assigned the task of developing a structure for light units

using pack animals or light trucks. The committee's report called for a

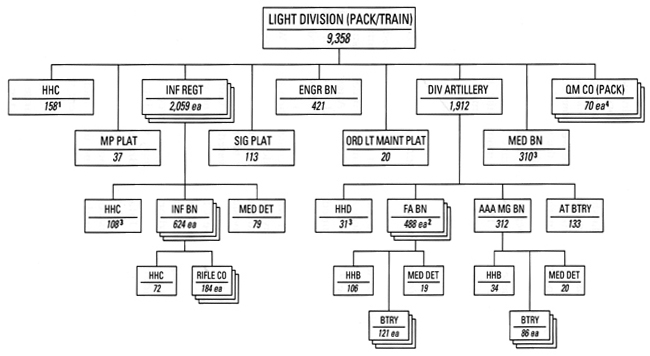

9,000-man triangular infantry division (Chart 21) with two types

of field artillery and quartermaster units. The pack division had over 1,700

animals, most of which were mules for the field artillery and quartermaster

units, while the truck division had only 267 1/4-ton trucks and 200 1/4-ton

trailers. Both divisions were also authorized numerous handcarts.31

-

- General McNarney, the Deputy Chief

of Staff, decided to test these organizations and on 21 June approved the

formation of three rather than two light divisions. One was to be truck,

another pack, and the third a modified pack. The modified pack division's

men and units were to be equipped with skis, snowshoes, toboggans, and cargo

sleds. Because of the growing number of troops undergoing special winter

training at Camp Hale, Colorado, Army Ground Forces suggested they be organized

under a divisional structure. The adjutant general added the 10th and 71st

Light Divisions to the rolls. On 15 July 1943 Brig. Gen. Robert L. Spragin,

a veteran of the Guadalcanal campaign, assumed command of the 71st at Camp

Carson, Colorado, and Maj. Gen. Lloyd E. Jones, former commander of the

U.S. Army Forces at Amchitka, Alaska, took over the 10th at Camp Hale. The

71st was built around the 5th and 14th Infantry, regiments that had served

in the jungles of Panama. The 10th was based on the 86th Infantry and other

units at Camp Hale that were undergoing winter warfare training. Eventually

the 87th Infantry, which had served in Alaska, joined the 10th. The 89th

Infantry Division at Camp Carson supplied fillers for both divisions. On

1 August 1943 the 89th itself was reorganized and redesignated as the 89th

Light (Pack) Division. Neither light amphibious nor light airborne divisions

were organized because the War Department opposed any change in the existing

airborne division and the Southwest Pacific Area Command lacked confidence

in the light amphibious concept, preferring standard infantry divisions

for amphibious operations.32

-

- Army leaders quickly noted some

major problems in the light divisions during their training. Neither the

71st Light (Truck) nor 89th Light (Pack) Division included adequate infantry

staying power; the 1/4-ton trucks lacked suitable mobility on wet, mountainous,

makeshift roads; the 75-mm. pack howitzer provided inadequate firepower;

the division lacked reconnaissance resources and had insufficient engineer

and medical capabilities; and the division staff was unable to operate twenty-four

hours a day within the authorized assigned personnel. The divisions were

not self-sustaining. Maj. Gen. John Millikin, who tested the divisions in

maneuvers, recommended, "That unless a definite need for these types

of divisions can be foreseen, the present Light divisions (motor and pack)

[should] be returned to a standard division status.."33

No need seemed to exist for the divisions, and even the Southwest Pacific

Area, the command for which they were originally designed,

- [188]

- Light Division, 1943

-

- 1 Includes medical detachment.

- 2 Pack 75-mm Howitzer Battalions. When the situation warranted, the Truck-drawn

75-mm Howitzer Battalions (362 men) may be substituted.

- 3 Includes Chaplains.

- QM Truck Company (209) men) may be substituted for the 3 QM Pack Companies.

-

- [189]

- wanted nothing to do with them. Army

Ground Forces therefore reorganized the 71st and 89th Divisions in May 1944

as standard infantry divisions.34

-

- The 10th Light (Alpine) Division

proved unsatisfactory for many of the same reasons as the truck and pack

units. Marshall, however, wanted it reorganized and retained in the force

because of its mountain warfare skills. Eventually Army Ground Forces recommended

the addition of three weapons companies to each of the division's infantry

regiments; an increase in the size of the engineer, signal, and medical

elements; and the provision of mule transport for all combat elements. In

November 1944 the War Department published tables of organization and equipment

reflecting these changes, which gave the division 14,101 officers and enlisted

men and 6,152 animals. The same month, the 10th Light Division became the

10th Mountain Division, and in December it moved to the Mediterranean theater.

The division went overseas without animals, receiving them from remount

stations in the theater before going into combat.35

-

-

- While Army Ground Forces and General

Staff officers revised divisional organizations, the number of divisions

expanded and a final determination was made regarding the total number needed.

Army Ground Forces organized the last reserve infantry division, the 97th,

in February 1943. By August 1943 it had also activated as a part of the

Army of United States the 42d, 63d, 65th, 66th, 69th, 70th, 75th, and 106th

Infantry Divisions; the 16th and 20th Armored Divisions; and the 11th, 13th,

and 17th Airborne Divisions (Table 14).36

-

- The 42d was a unique unit, for it

was a reconstitution of the World War I "Rainbow Division." Except

for the division headquarters, none of its earlier elements were returned,

but Army Ground Forces filled its new units with personnel from every state.

To emphasize the division's tie to its World War I predecessor, Maj'. Gen.

Harry J. Collins, the commander, activated the unit on 14 July, the eve

of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Champagne-Marne campaign in France

during which the "Rainbow" had helped to stem a German drive on

Paris.37

-

- In addition to activating more airborne

divisions in 1943, the War Department made changes in the airborne brigade

force. To emphasize both the parachute and the glider training missions,

the 1st Airborne Infantry Brigade replaced the 1st Parachute Infantry Brigade

as a training unit. The Airborne Command also formed the 2d Airborne Infantry

Brigade that year to help in training. The 1st Brigade existed for approximately

seven months and was disbanded after most nondivisional airborne units had

gone overseas. In the fall of 1943 the 2d Brigade deployed to Europe where

it continued to support airborne training.38

-

- The need for the cavalry division

remained questionable. Because Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson had insisted

on maintaining large horse units, Army Ground Forces replaced the organizations

withdrawn from the 1st Cavalry Division

- [190]

- Maj. Gen. Elbridge G. Chapman

and General McNair inspect the 13th Airborne Division, 13 May 1944.

-

- for the North African campaign and

reactivated the 2d Cavalry Division early in 1943 as an all-black unit split

between Camp Clark, Texas, and Camp Lockett, California.39

-

- Deployment of cavalry divisions,

however, proved to be a thorny problem. The units remained unpopular with

theater commanders because of the shipping space they required and the logistical

nightmare they presented, given their horses and equipment. The need for

units in the Southwest Pacific Area, however, led MacArthur to accept the

1st Cavalry Division as a dismounted unit. The division turned in its horses

and associated gear in March 1943 and left for Australia in June. Many of

the horses of the 1st Cavalry Division found a home in the 2d Cavalry Division.40

-

- In Australia the division was reorganized

partly under infantry and partly under cavalry tables. Each cavalry squadron

was allotted a heavy weapons troop similar to the weapons company in the

infantry battalion. The veterinary troop in the medical squadron became

a collecting troop, and the reconnaissance squadron was reduced to a troop

similar to the unit in the infantry division. Some of the personnel and

equipment of the reconnaissance squadron were used to create a light tank

company. The addition of a 105-mm. howitzer battalion gave the artillery

two 105-mm. and two 75-mm. howitzer battalions. Along with the reorganization,

the adjutant general redesignated the unit as the 1st Cavalry Division,

Special, because of its unique organization under infantry and cavalry tables

and the desire to retain the cavalry "name" among the divisional

forces. Having completed all changes by 4 December 1943, the division moved

to New Guinea for combat. More organizational changes took place thereafter,

particularly in the artillery, which eventually included four tractor-drawn

105-mm. howitzer battalions and an attached 155-mm, howitzer battalion.41

-

- Personnel shortages dictated a different

fate for the 2d Cavalry Division and the 56th Cavalry Brigade. The Mediterranean

theater needed service troops, and in September 1943 the War Department

decided to use the personnel of the 2d Cavalry Division in that role. Leaving

the country in February 1944, the division was inactivated shortly thereafter

in North Africa and its men reassigned to a variety of service units. Army

Ground Forces eliminated the 56th Cavalry Brigade when no use for it developed

overseas. Its headquarters troop became the

- [191]

- Divisions Activated in

1943

-

| Component |

Division |

Date |

Location |

| RA |

2d Cavalry |

25 February |

Fort Clark, Tex. |

| AUS |

11th Airborne |

25 February |

Camp Mackall, N.C. |

| OR |

97th Infantry |

25 February |

Camp Swift, Tex. |

| AUS |

20th Armored |

15 March |

Camp Campbell, Ky. |

| AUS |

106th Infantry |

15 March |

Fort Jackson, S.C. |

| AUS |

17th Airborne |

15 April |

Camp Mackall, N.C. |

| AUS |

66th Infantry |

15 April |

Camp Blanding, Fla. |

| AUS |

75th Infantry |

15 April |

Fort Leonard Wood, Mo. |

| AUS |

69th Infantry |

15 May |

Camp Shelby, Miss. |

| AUS |

63d Infantry |

15 June |

Camp Blanding, Fla. |

| AUS |

70th Infantry |

15 June |

Camp Adair, Oreg. |

| AUS |

42d Infantry |

14 July |

Camp Gruber, Okla. |

| AUS |

10th Light |

15 July |

Camp Hale, Colo. |

| AUS |

16th Armored |

15 July |

Camp Chaffee, Ark. |

| AUS |

71st Light |

15 July |

Fort Benning, Ga. |

| AUS |

13th Airborne |

13 August |

Fort Bragg, N.C. |

| AUS |

65th Infantry |

16 August |

Camp Shelby, Miss. |

-

- 56th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop,

Mechanized, but did not see combat. The former brigade's cavalry regiments

went on to fight in the Pacific and China-Burma-India theaters.42

-

- With ongoing manpower shortages,

the Army continually examined the relationship between the total military

force and the manpower pool available for military service. That relationship

was constantly balanced against the manpower required to maintain the productive

capacity of industry, which remained vital to the overall Allied war effort.

As the war progressed, staff studies suggested that the number of divisions

mobilized could be cut. Soviet armies had checked the German advance, and

it appeared that the Allies would gain air superiority over Europe. Therefore,

shortly before the invasion of northern France in 1944, the War Department

approved a troop basis that contained 90 divisions rather than 100 within

a total Army strength of 7,700,000. The French were to raise ten divisions,

and the United States was to equip them, which created equipment shortages.

That troop basis called for 1 light, 2 cavalry, 5 airborne, 16 armored,

and 66 infantry divisions. With the inactivation of the 2d Cavalry Division

in May 1944, the number of divisions in the troop basis was reduced by one

and the number of divisions raised during World War II remained at eighty-nine.

The decision to limit the number of divisions haunted War Department planners

during the remainder of the war for they feared that mobilization had not

gone far enough. Marshall, however, held to the eighty-nine divisions in

the troop basis.43

- [192]

-

- Although the Army began deploying

divisions shortly after the nation entered the war, the number of trained

and partially trained divisions still located within the United States mounted

in 1943 because of port and shipping problems. Unlike World War I, no troops

were to be sent to foreign stations unless the War Department could guarantee

their supply. In August 1943 sixty divisions were at various stages of readiness

in the United States.44

-

- Toward the end of 1943 the deployment

picture brightened. With the nation's massive ship-building program and

the retreat of German submarines from the western Atlantic, the War Department

was able to accelerate the deployment of divisions. Most went to Europe

to take part in the cross-Channel attack and the drive to strike at the

German heartland. Eventually 68 divisions-47 infantry, 16 armored, 4 airborne,

and 1 mountain -fought in Europe and 21 divisions-1 airborne, 1 cavalry

(organized as infantry), and 19 infantry-in the Pacific area. (Tables

15 and 16 give the date that each division moved to the port of embarkation.)

No division remained in the continental United States after February 1945.

45

-

- Although most infantry and armored

divisions had been reorganized prior to seeing combat because of the delay

in moving them overseas, the Army reorganized its airborne divisions to

meet specific combat needs. The first modification, involving only the 82d,

took place during the preparation for the Sicilian campaign. Because of

a shortage of shipping space for gliders, a crated glider being one of the

largest pieces of equipment sent overseas, a parachute infantry regiment

replaced one of the glider regiments, and a second parachute field artillery

battalion was added. The change was in keeping with the original plan for

the division, which envisioned a task force organization.46

-

- After the Sicily campaign, General

Ridgway, the commander of the "All American" 82d, organized a

small pathfinder team to help divisional elements reach their targets. The

team's mission was to jump into the assault area and guide the remainder

of the division to the drop zone. After the team proved successful in Italy,

other airborne divisions organized similar units.47

-

- Combat operations soon demonstrated

that the airborne division lacked sufficient manpower and equipment for

sustained operations. In Sicily and Italy resources were not available to

relieve or replace the division with either an infantry or armored division

as quickly as planners had envisioned. In December 1943 Ridgway recommended

changes in the airborne division to correct major deficiencies. Because

it served primarily as infantry, he wanted more transportation resources;

additional medical, engineer, and quartermaster support; and greater infantry

and artillery firepower. Planners in Washington opposed the changes because

they thought the additional equipment and personnel would prevent the division

from serving as a light, mobile force, stripped to the bare essentials and

easily air transportable.48

- [193]

- Deployment of Divisions

to the Pacific Theater

-

| Division |

Date |

| 1st Cavalry |

June 1943 |

| 6th Infantry |

July 1943 |

| 7th Infantry |

April 1943 |

| 11th Airborne |

April 1944 |

| 24th Infantry |

* |

| 25th Infantry |

* |

| 27th Infantry |

March 1942 |

| 31st Infantry |

February 1944 |

| 32d Infantry |

April 1942 |

| 33d Infantry |

June 1943 |

| 37th Infantry |

May 1942 |

| 38th Infantry |

December 1943 |

| 40th Infantry |

August 1942 |

| 41st Infantry |

March 1942 |

| 43d Infantry |

September 1942 |

| 77th Infantry |

March 1944 |

| 81st Infantry |

June 1944 |

| 93d Infantry |

January 1944 |

| 96th Infantry |

July 1944 |

| 98th Infantry |

April 1944 |

| Americal |

* |

| Philippine |

# |

-

- * Unit organized outside the continental

United States.

- #Partially organized in 1941; surrendered

in April 1942.

-

- After the assault landings by the

82d and 101st in Holland in 1944, Ridgway again attempted to revise the

authorized structure of the divisions. The 82d had an additional 4,000 troops

attached in the Normandy jump and over 5,000 for its operations in Holland.

The 101st had also been augmented for both operations. Frustrated with the

bureaucracy, Ridgway, then commanding the XVIII Airborne Corps, appealed

personally to General Marshall for aid in reorganizing the divisions. Marshall

directed his staff to reconsider their structure and invited Ridgway or

his representative to Washington to explain his ideas. Instead of coming

himself, Ridgway sent Maj. Gen. Maxwell D. Taylor, the 101st's commander.

On the day the German Ardennes offensive began, the War Department published

new tables of organization and equipment for the airborne division. Marshall

described it to Ridgway as "in all probability wholly acceptable to

you and your associates." 49

-

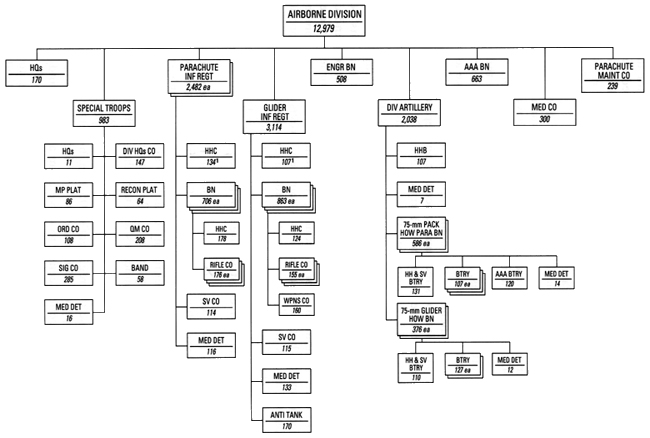

- The new airborne division consisted

of one glider infantry and two parachute infantry regiments, division artillery,

antiaircraft artillery and engineer battalions,

- [194]

- Deployment of Divisions

to the European Theater

-

| Division |

Date |

Division |

Date |

| 1st Armored |

- May 1942

|

42d Infantry |

November 1944 |

| 1st Infantry |

- June 1942

|

44th Infantry |

August 1944 |

| 2d Armored |

- September 1942

|

45th Infantry |

May 1943 |

| 2d Cavalry |

- February 1944

|

63d Infantry |

November 1944 |

| 2d Infantry |

- September 1943

|

65th Infantry |

December 1944 |

| 3d Armored |

- September 1943

|

66th Infantry |

November 1944 |

| 3d Infantry |

- September 1942

|

69th Infantry |

November 1944 |

| 4th Armored |

December 1943 |

70th Infantry |

November 1944 |

| 4th Infantry |

January 1944 |

71st Infantry |

January 1945 |

| 5th Armored |

February 1944 |

75th Infantry |

October 1944 |

| 5th Infantry |

April 1942 |

76th Infantry |

November 1944 |

| 6th Armored |

February 1944 |

78th Infantry |

October 1944 |

| 7th Armored |

May 1944 |

79th Infantry |

March 1944 |

| 8th Armored |

October 1944 |

80th Infantry |

June 1944 |

| 8th Infantry |

November 1943 |

82d Airborne |

April 1943 |

| 9th Armored |

August 1944 |

83d Infantry |

March 1944 |

| 9th Infantry |

September 1942 |

84th Infantry |

September 1944 |

| 10th Armored |

September 1944 |

85th Infantry |

December 1943 |

| 10th Mountain |

December 1944 |

86th Infantry |

February 1945 |

| 11th Armored |

September 1944 |

87th Infantry |

October 1944 |

| 12th Armored |

September 1944 |

88th Infantry |

November 1943 |

| 13th Airborne |

January 1945 |

89th Infantry |

January 1945 |

| 13th Armored |

January 1945 |

90th Infantry |

March 1944 |

| 14th Armored |

October 1944 |

91st Infantry |

March 1944 |

| 16th Armored |

January 1945 |

92d Infantry |

September 1944 |

| 17th Airborne |

August 1944 |

94th Infantry |

July 1944 |

| 20th Armored |

January 1944 |

95th Infantry |

July 1944 |

| 26th Infantry |

August 1944 |

97th Infantry |

February 1945 |

| 28th Infantry |

September 1943 |

99th Infantry |

September 1944 |

| 29th Infantry |

September 1942 |

100th Infantry |

September 1944 |

| 30th Infantry |

January 1944 |

101st Airborne |

August 1943 |

| 34th Infantry |

January 1942 |

102d Infantry |

September 1944 |

| 35th Infantry |

- May 1944

|

103d Infantry |

September 1944 |

| 36th Infantry |

April 1943

|

104th Infantry |

August 1944 |

|

|

106th Infantry |

October 1944 |

-

- medical and parachute maintenance

companies, and special troops, to which the division headquarters, ordnance,

and quartermaster companies; military police and reconnaissance platoons;

band; and medical detachment reported (Chart 22). The tables reversed

the proportion of parachute and glider infantry regiments and considerably

strengthened the units. The glider infantry regiment was authorized

- [195]

- a third battalion and an antitank

company, and both types of regiments fielded heavier weapons. In the engineer

battalion the number of parachute and glider companies was also reversed.

The four battalions in the division artillery, both parachute and glider units,

were authorized 75-mm. pack howitzers, but a note on the tables indicated

that one glider artillery battalion could be equipped with 105mm. howitzers

if more firepower was necessary. As in the other divisions, the field artillery

was authorized observation and liaison aircraft. The number of trucks jumped

from 400 to 1,000, and the authorized strength soared to 12,979. Approximately

50 percent of the men were parachutists.50

-

- To adopt the new structure, the

overseas commands were forced to rely on their own resources because the

War Department made no additional men available. Existing nondivisional

parachute infantry and field artillery units were assigned to the airborne

divisions, and other units, including 2d Airborne Infantry Brigade headquarters,

were disbanded to obtain personnel. In March 1945 the European Command reorganized

the 13th, 17th, 82d, and 101st Airborne Divisions. The 11th Airborne Division

in the Pacific was reorganized in July but, unlike the European divisions,

the unit was authorized two 105-mm. howitzer glider battalions in place

of two 75-mm. pack units, and one glider infantry regiment was converted

to parachute infantry. Throughout the war Maj. Gen. Joseph Swing, the 11th's

commander, had insisted upon cross-training glider and parachute troops.

Only the 17th Airborne Division participated in an assault landing after

the reorganization; all others served as infantry for the remainder of the

war.51

-

- Combat experience also led to alterations

in both the infantry and armored divisions after the 1943 revision. The

most significant change took place in the armored division, where the small

headquarters of the division artillery command was expanded to a headquarters

and headquarters battery, providing the division with a fire direction center.

Because of the many minor changes, the War Department published new tables

for both types of divisions in January 1945, incorporating all the changes

since 1943. At that time the strength of the infantry division stood at

14,037 and the armored division at 10,700.52

-

-

- Neither infantry nor armored divisions

proved to be completely satisfactory during combat because they lacked all

the resources habitually needed to operate efficiently. In the European

theater, when an infantry division conducted offensive operations it almost

always had attached tank, tank destroyer, and antiaircraft artillery battalions.

Because of the shortage of tank and tank destroyer units, these units were

not available to serve regularly with the same division, resulting in considerable

shuffling of attached units, which diminished effective teamwork. The cannon

company in the infantry regiment was hampered by the limited cross-country

ability of the 105-mm. howitzer's prime mover. Often tied to the division

- [196]

- Airborne Division, 1944

-

- 1 Includes chaplains.

-

- [197]

- artillery, the company also created

ammunition shortages for that headquarters. Divisional reconnaissance suffered

because the troop lacked sufficient strength and its vehicles were too lightly

armored and armed. The decision to have fewer divisions and to maintain them

through a constant flow of replacements proved costly. Many recruits were

killed or seriously wounded before they could be effectively worked into the

fabric of frontline units.53

-

- The armored division lacked sufficient

infantry and medium artillery. To solve this problem, attachments took place

when such units were available. Combat experience also dictated that the

division have three combat teams. Under the 1942 structure the infantry

regiment's headquarters in the 2d and 3d Armored Divisions was often provisionally

organized as a third combat command. In the other divisions, under the 1943

configuration, an armored group headquarters and headquarters company was

attached to serve as a combat command.54

These expedients created command and control problems and complicated teamwork.

The division's reconnaissance unit and replacement system suffered from

the same weaknesses as in the infantry division.55

-

- In January 1945, recognizing these

organizational problems, the War Department began to revise the infantry

division structure for units planned for redeployment from Europe, after

the defeat of Germany, to the Pacific theater to aid in the conquest of

Japan. The War Department cast aside its policy of rejecting changes in

units because of personnel considerations and directed staff agencies to

prepare tables for sound fighting teams. It ordered the elimination of dual

assignments for personnel, the addition of any equipment listed earlier

as special but that had been used routinely, provisions for more adequate

communications in all components, and an expansion of military police resources.

The infantry regiment was to receive more mobile, self-propelled howitzers

and better antitank weapons. Later the War Department instructions indicated

that the revised structure would not be limited to use in the war against

Japan.56

-

- On 1 March 1945 Army Ground Forces

submitted three proposals for reorganizing the infantry division. Each specified

different manning levels, but the planners recommended the one that maximized

the division's size and firepower. An enlarged infantry regiment with 700

additional men provided more punch. The weapons platoon in each rifle company

had two new sections, one with six 2.36-inch rocket launchers and the other

with three 57-mm. recoilless rifles.57

In the battalion's weapons company a new platoon of six 75-mm. recoilless

rifles augmented the two platoons equipped with light and heavy machine

guns. Because the regiment's 105-mm. howitzers lacked cross-country mobility

for close support, commanders had tied the cannon company to the field artillery

fire direction center to serve as an additional indirect fire battery. Army

Ground Forces thus replaced the cannon company with a tank company comprising

nine tanks. The tanks also replaced the 57-mm. towed guns in the antitank

company, which were too lightly armored and judged to be too road-

- [198]

- bound. The number of truck drivers,

communications and postal personnel, and ammunition bearers was increased.

The military police force grew from a platoon to a company and a signal

battalion replaced the signal company. A tank battalion was added to the

division and a fourth company to the division engineer battalion. To expand

the "eyes and ears" of the division, the reconnaissance troop

was increased in size and authorized two light aircraft. These changes together

resulted in a proposed divisional strength of 18,285 personnel, an increase

of 4,248 men over the January 1945 figure.58

-

- On 5 April the Army Staff informed

Army Ground Forces that because of expected personnel shortages divisions

could not be reorganized according to any of the proposed changes. Instead,

the staff directed the command to prepare another set of tables that would

increase personnel for communications, replace the military police platoon

with a company, enlarge each 105-mm. and 155-mm. howitzer battery from four

to six pieces, and restructure the infantry regiment along the lines of

the March proposal. Shortly after issuing these instructions, the staff

told Army Ground Forces that about fifty more men could be added to the

division for various service duties.59

-

- On 1 June the War Department published

tables for the infantry division calling for 15,838 officers and enlisted

men. The division met most of the Army Staff's guidance, except for the

proposed increases in the artillery batteries. The planners believed that

the new organization gave the division more mobility, flexibility, and firepower,

in particular for tank warfare. No unit, however, adopted the structure

until October 1945.60

-

-

- The war ended in Europe in May 1945,

and the Army had to come to grips with demobilization while still engaged

in the war against Japan. Aware that the call to "bring the boys home"

would eventually be irresistable, as early as 1943 Acting Secretary of War

Robert E Patterson had appointed Maj. Gen. William F. Tompkins to head the

Special Plans Division (SPD), War Department Special Staff, to plan for

demobilization and reorganization of the postwar Army.61

-

- Tompkins began with the assumptions

that the war in Europe would end first, that an occupation force would be

needed there, and that those who had served the longest should be released

as quickly as possible. Enough soldiers had to be retained to conclude the

war in the Pacific. With these ideas in mind, the Special Plans Division

and the overseas commands worked out a redeployment policy based on a point

system. Under it, men received points for length of service, combat participation,

military awards, and time spent overseas. Soldiers who were parents were

also to receive special consideration. Out of this rating system, four categories

of soldiers emerged: those to be retained for service in a command; those

to be transferred to a new command; those to form new units in a command;

and those to be discharged.62

- [199]

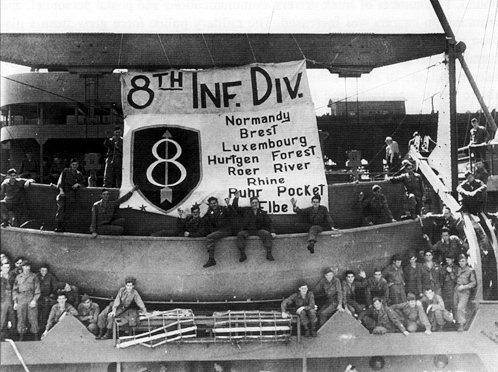

- 8th Infantry Division arrives at Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation,

1945

-

- When the War Department approved the

redeployment policy in the spring of 1945, planners believed the European

command would need to furnish fifteen divisions to end the war in the Far

East and twenty-one to the United States to reconstitute a strategic reserve,

which had ceased to exist in February 1945. Following the German offensive

in the Ardennes in December 1944, the last seven divisions in the ninety-division

troop program had been sent to Europe. With the point system and a tentative

troop basis in place, redeployment waited only for the fighting to end in

Europe.63

-

- On 12 May, four days after the surrender

of Germany, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander,

set the readjustment program into motion. High and low point men switched

units, and in June the 86th, 95th, 97th, and 104th Infantry Divisions left

Europe for reassignment. Arriving home, the men took thirty-day leaves before

undergoing training to prepare for the Pacific theater. But the successful

use of atomic bombs against Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August skewed all

readjustment plans toward demobilization. By September 1945, 19 divisions1

airborne, 1 mountain, 2 armored, and 15 infantry returned from Europe for

use elsewhere. Of those units, only the 86th and 97th Infantry Divisions

moved to the Far East, arriving in the Philippines and Japan after the fighting

had ended.64

- [200]

- Compared to World War I, divisional

organizations had rapidly adjusted to the demands of the Second World War.

Initially three considerations greatly influenced the organization of the

various divisions: the availability of men to field the units desired by

the Army; the availability of shipping space to move them to the combat

theaters; and the availability and quality of equipment. The last proved

influential, continually forcing the Army to make structural changes to

accommodate improved weapon systems or, in some cases, to eliminate those

that proved less than successful in combat. In 1943 McNair attempted to

reorganize divisional structures based on experiences acquired during the

maneuvers of 1940 through 1942 and on the battlefield, where infantry, armored,

and airborne divisions had to be augmented routinely, in particular to oppose

tanks and airplanes. As the European war came to a close, the General Staff

attempted to give infantry divisions the additional resources they habitually

needed, but this effort came too late to benefit them during the conflict.

-

- Before and during World War II the

Army also sought to develop several new types of divisions and to achieve

an acceptable balance between firepower and mobility. Planners tried not

to sacrifice either capability to the other, seeking instead to serve both

masters. This effort proved reasonably successful in the acid test of battle,

especially by comparison with the performance of divisions during World

War I. The accumulated experience of the twentieth century eased the task

of making periodic organizational adjustments to satisfy changing requirements.

Nevertheless, this evolutionary process would continue after World War II

as the pace of technological developments and expanded global security roles

of the United States Army forced it down roads that had never been traveled

before.

- [201]

Endnotes

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

page created 29 June 2001

Return to the

Table of Contents

-