-

-

- In 1939 the Army created a protective

mobilization force for the defense of the Western Hemisphere. The force

included the 1st, 2d, 3d, 5th, and 6th Divisions, which were organized under

the new triangular configuration. These forces, however, still needed to

be manned and trained for war. Congressional increases in the size of the

Regular Army, which began that year, provided much of the needed manpower,

while the largest peacetime maneuvers ever undertaken by the Army to date

provided a taste of war in 1940.2

Between 5 and 25 May 1940 the 1st, 2d, 5th, and 6th Infantry Divisions joined

the 1st Cavalry Division, the 7th Cavalry Brigade, a provisional brigade

of light and medium tanks, and other units for maneuvers near

-

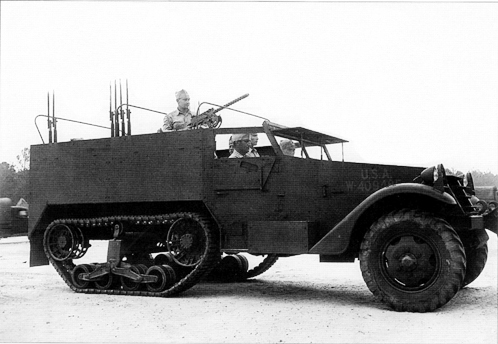

- 67th Infantry (Provisional Tank Brigade), at Third Army maneuvers,

1940

-

- the Louisiana and Texas border, a

step envisaged at the turn of the century to train an army corps. Not surprisingly,

the exercises highlighted weaknesses in most units in almost every area of

concern, including organization.3

-

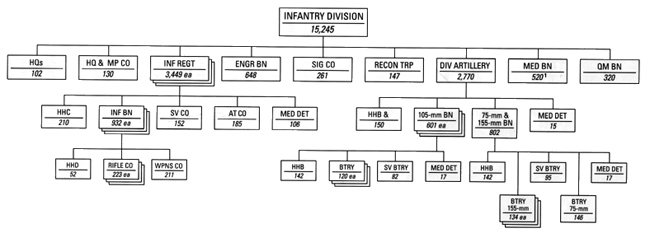

- To improve the infantry division,

it was again reorganized, making it more powerful and easier to command

and control. A headquarters and headquarters battery, which provided a fire

direction control center and a brigadier general as commander of the division

artillery, replaced the field artillery section in the division headquarters.

Four field artillery battalions, three direct support and one general support,

replaced the two regiments. The direct support battalions were to be armed

with newly approved 105-mm. howitzers, while the general support battalion

fielded 155-mm. howitzers and 75-mm. guns, the latter retained primarily

as antitank weapons. Each field artillery battalion also was outfitted with

six 37-mm. antitank guns. To counter operations such as the German blitzkrieg,

which had proven so successful in Poland, antitank resources were centralized

in the infantry regiments to form regimental antitank companies outfitted

with 37-mm. antitank guns. In infantry battalions the number of antitank

"guns"-the .50-caliber machine guns-was doubled. For targets of

opportunity, more 81-mm. mortars were added to the heavy weapons company

and three 60-mm. mortars were authorized for each rifle company. A reconnaissance

troop appeared in the division, reflecting the growth in its operational

area on the battlefield, and the number of collecting companies in the medical

battalion was increased from one to three. Finally, new tables of orga-

- [144]

- 37-mm. gun and crew, 1941

-

- nization eliminated the infantry section

with its general officer in the division headquarters but provided an assistant

division commander with the rank of brigadier general. These changes brought

the strength of the division to 15,245 officers and enlisted men, with its

combat power still focused in the three regimental combat teams (Chart

12).4

-

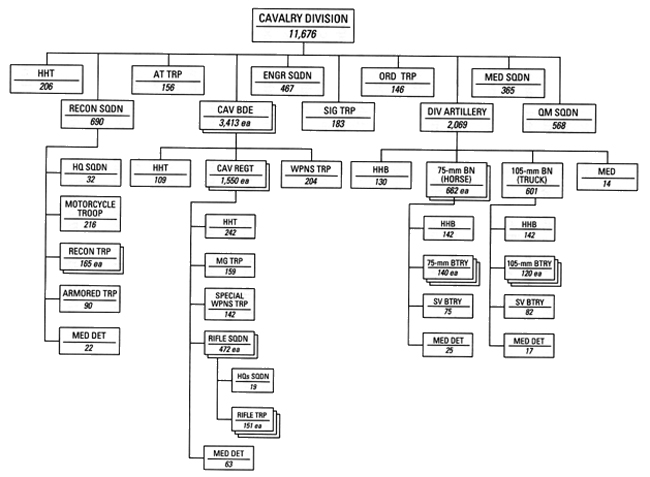

- Despite the trend in foreign armies

to replace horse cavalry with mechanized units, the Assistant Chief of Staff,

G-3, Maj. Gen. Frank M. Andrews, decided to table any organizational decisions

affecting the cavalry. Until a definite theater of operations could be ascertained,

the Army needed to prepare general purpose forces. The horse was capable

of going where a machine could not, and the cavalry division appeared to

have a place in the force. Among the questions Andrews wanted answered was,

again, whether the division should be built on a triangular or square configuration.

He also wanted to explore if and how horse and mechanized units could operate

together within a cavalry corps.5

-

- After the 1940 maneuvers Maj. Gen.

Kenyon A. Joyce, commanding the 1st Cavalry Division, recommended retention

of the square cavalry division. A division with two brigades, each with

two cavalry regiments, was easily split into strike and reserve forces.

If the division were organized along triangular lines, the regiments would

have to be enlarged to maintain their firepower, but it would make them

too large for effective command and control. Joyce suggested that the cavalry

regiment comprise a headquarters; headquarters and service, machine gun,

and special weapons troops; and two rifle squadrons of three troops each.

He

- [145]

- Infantry Division, 1 November 1940

-

- 1 Includes ten people for the surgeon's office in the division headquarters.

- AT = Antitank

-

- [146]

- wanted to strengthen the two-battalion

field artillery regiment by creating batteries of six rather than four 75-mm.

howitzers and adding a truck-drawn 105-mm. howitzer battalion. To improve

mobility, the division needed enough trucks to move horses and equipment to

the battlefield. He suggested the elimination of only one organization-headquarters,

special troops-which facilitated administration in garrison, but not in the

field.6

-

- Joyce decided that horse and mechanized

units were compatible within a cavalry corps since the 1st Cavalry Division

and the 7th Cavalry Brigade (Mechanized) had successfully conducted joint

operations during the maneuvers. He urged the Army to maintain a corps that

included both types of units. The proportion of horse and mechanized units

could vary to meet various tactical situations, but he thought the corps

should be strong in artillery and engineers and contain sufficient support

troops to enable it to operate with maximum speed, flexibility, and striking

power.7

-

- The revised cavalry division remained

square and was to have 11,676 officers and enlisted men (Chart 13).

Divisional cavalry regiments conformed to Joyce's recommendations, but instead

of increasing the size of the field artillery regiment, one truck-drawn

105-mm. howitzer battalion and two 75-mm. pack howitzer battalions replaced

it. As in the infantry division, the cavalry division received antitank

weapons. The new wartime division tables authorized a divisional antitank

troop fielding twelve 37-mm. antitank guns and a weapons troop having antitank

guns and 81-mm. mortars within each brigade. The engineer, quartermaster

(formerly the division train), and medical squadrons were enlarged to meet

the needs of the bigger division. Draft, pack, and riding horses were limited

to the cavalry brigades and the division artillery, while other elements

of the division were motorized. Headquarters, special troops, was eliminated.8

-

- As the 1940 Louisiana maneuvers

drew to a close and the fall of France appeared imminent, the War Department

authorized an increase in the number of active Regular Army infantry divisions

and the adoption of the new tables. Between June and August 1940 the Army

activated the 4th, 7th, 8th, and 9th Divisions.

-

- Neither those divisions nor the

other active divisions had sufficient personnel to meet the new manning

levels. The 1st Cavalry Division did not adopt the revised configuration

until early in 1941 when it concentrated at Fort Bliss for training.9

-

-

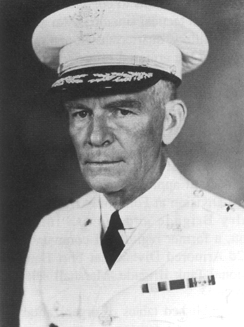

- During the 1940 maneuvers the Army

also had tested a provisional mechanized division. After the German invasion

of Poland in 1939, Brig. Gen. Adna R. Chaffee had called for "armored"

divisions separate from both infantry and cavalry. Chaffee's 7th Cavalry

Brigade (Mechanized), Brig. Gen. Bruce Magruder's Provisional Tank Brigade

(organized in 1940 with infantry tank units), and the 6th Infantry made

up the new unit. At the conclusion of the exercises, Chaffee; Magruder;

Col. Alvan C. Gillem, Magruder's executive officer; Col. George S.

- [147]

- Cavalry Division, 1 November 1940

-

-

- [148]

- General Chaffee

-

- Patton, commander of the 3d Cavalry

at Fort Myer, Virginia; and other advocates of tank warfare met with the G-3,

General Andrews, in a schoolhouse at Alexandria, Louisiana, to discuss the

future of mechanization. All agreed that the Army needed to unify its efforts.

The question was how. Both the chief of cavalry and the chief of infantry

had attended the maneuvers, but they were excluded from the meeting because

of their expected opposition to any change that might deprive their arms of

personnel, equipment, or missions.10

-

- Returning to Washington, Andrews

proposed that Marshall call a conference on mechanization. The crisis in

Europe had by then increased congressional willingness to support a major

rearmament effort, and at the same time the success of the German panzers

highlighted the need for mechanization, however costly. Andrews' initiative,

made three days after the British evacuated Dunkirk, noted that the American

Army had inadequate mechanized forces and that it needed to revise its policy

of allowing both infantry and cavalry to develop such units separately.

He suggested that the basic mechanized combined arms unit be a division

of between 8,000 and 11,000 men. With the chief of cavalry planning to organize

mechanized cavalry divisions, which mixed horse and tank units, such a conference

seemed imperative. Marshall approved Andrews' proposal.11

-

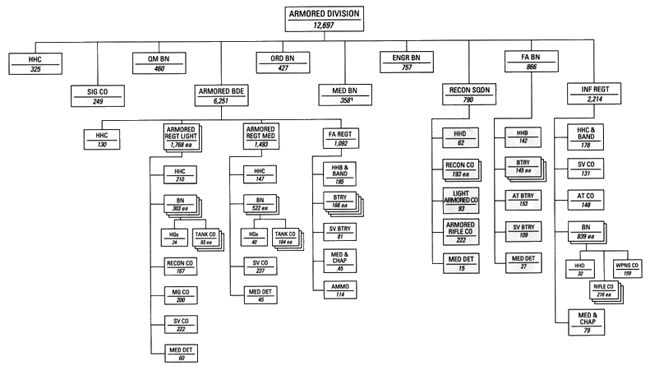

- From 10 to 12 June 1940 Andrews

hosted a meeting in Washington centering on the organization of mechanized

divisions. Along with the General Staff and the chiefs of the arms and services,

Chaffee, Magruder, and other tank enthusiasts attended. Andrews disclosed

that the War Department would organize an independent armored force, belonging

to neither the Infantry nor Cavalry branches, in the form of "mechanized

divisions." In such divisions the command and control echelon would

consist of a headquarters and headquarters company and a signal company.

A reconnaissance battalion with an attached aviation observation squadron

would constitute the commander's "eyes," which would operate from

100 to 150 miles in advance and reconnoiter a front from 30 to 50 miles.

At the heart of the division was an armored brigade made up of a headquarters

and headquarters company, one medium and two light armored regiments, a

field artillery regiment, and an engineer battalion. Using the two light

armored regi-

- [149]

- menu as the basis for two combat teams,

the division was to conduct reconnaissance, screening, and pursuit missions

and exploit tactical situations. An armored infantry regiment, along with

armored field artillery, quartermaster, and medical battalions and an ordnance

company, supported the armored brigade. Similar to the German panzer division,

it was to number 9,859 officers and enlisted men.12

-

- When approving the establishment

of the Armored Force to oversee the organization and training of two mechanized

divisions on 10 July 1940, Marshall also approved designating these units

as "armored" divisions. Furthermore, he directed the chief of

cavalry and the chief of infantry to make personnel who were experienced

with tank and mechanized units available for assignment to the divisions.

On 15 July, without approved tables of organization, Magruder organized

the 1st Armored Division at Fort Knox from personnel and equipment of the

7th Cavalry Brigade and the 6th Infantry. Concurrently, Brig. Gen. Charles

L. Scott, a former regimental commander in the 7th Cavalry Brigade, activated

the 2d Armored Division at Fort Benning using men and materiel from the

Provisional Tank Brigade. Marshall selected Chaffee to command the new Armored

Force.13

-

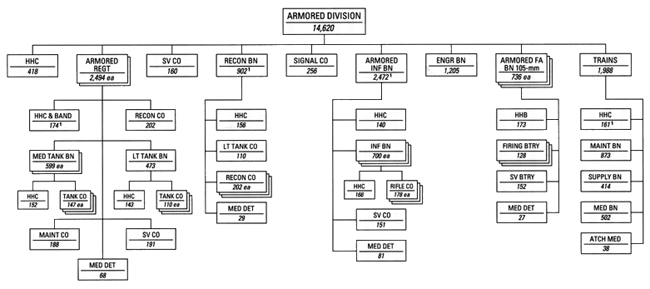

- Four months later the War Department

published tables of organization for the armored division (Chart 14).

It resembled the unit developed during the summer, except that the engineer

battalion was removed from the armored brigade and assigned to the division

headquarters, and the ordnance company was expanded to a battalion. To the

surprise of Chaffee, who had supervised the preparation of the tables, the

authorized strength of the division rose from 9,859 to 12,697, including

attached personnel.

-

- The division fielded 381 tanks and

97 scout cars when all units were at war strength.14

Chaffee envisaged the establishment of corps-size units commanding both

armored and motorized divisions, the latter essentially an infantry division

with sufficient motor equipment to move all its personnel. On 15 July 1940

the War Department selected the 4th Division, which had recently been reactivated

as part of the Regular Army's expansion, for this role. Collocated with

the 2d Armored Division at Fort Benning, the 4th's divisional elements had

earlier experimented with motorized infantry. Eventually the department

published tables of organization for a motorized division that retained

the triangular structure but fielded 2,700 motor vehicles including over

600 armored half-track personnel carriers.15

-

- Along with the reorganization and

expansion of divisional forces, the Army increased unit manning levels and

concentrated units for training. A peacetime draft, adopted on 16 September

1940, provided the men, and eventually the strength of all divisions neared

war level. Prior to 1940 units were scattered over 130 posts, camps, and

stations in the United States, but with mobilization Congress provided funds

for new facilities. The Quartermaster Corps, during the winter of 19401,

built accommodations for 1.4 million men, including divisional posts of

the type constructed in World War I. 16

- [150]

- Armored Division, 15 November 1940

-

- 1 Includes ten people for the surgeon's office in the division headquarters.

-

- [151]

- Half-track personnel car, 1941

-

- But as in World War I, equipment shortages

could not be quickly remedied and greatly inhibited preparation for war. Among

other things, the Army lacked modern field artillery, rifles, tanks, and antitank

and antiaircraft weapons. Although acutely aware of the shortages, Marshall

believed that the Army could conduct basic training while the production of

weapons caught up. 17

-

-

- As the possibility that the nation

might be forced into the European war increased, some members of the War

Department favored federalization of the National Guard to correct deficiencies

in its training and equipment. In August 1940, after much debate, Congress

approved the induction of Guard units for twelve months of training. It

also authorized their use for the defense of the Western Hemisphere and

the territories and possessions of the United States, including the Philippine

Islands. 18

-

- Induction of Guard units began on

Monday, 16 September, with federalization of the 30th, 41st, 44th, and 45th

Divisions, less their tank and aviation units. These latter units eventually

served in World War II, but not as divisional organizations. The divisions

were considerably understrength, each having approximately 9,600 men, but

training camps were not prepared even for that number. To bring the divisions

to war level, the War Department supplied draftees and within

- [152]

- six months all eighteen Guard infantry

divisions had entered federal service and were training at divisional posts.

19

-

- Federal law required Guard units

to be organized under the same tables as the regulars. But the Guard divisions

had not yet adopted the triangular configuration, and the General Staff

hesitated to reorganize them immediately as they were in federal service

only for training. Furthermore, the staff feared political repercussions

when general and field grade officers were eliminated to conform to the

new tables.20

-

- The National Guard also maintained

two separate infantry brigades, the 92d and 93d, which did not fit into

any war plans of 1940. At the request of the National Guard Bureau, New

York converted the 93d to the 71st Field Artillery Brigade, and Minnesota

reorganized the 92d as the 101st Coast Artillery Brigade, and the units

entered federal service as such.21

-

- Although war plans did not call

for separate infantry brigades in the United States, the War Department

authorized a new 92d Infantry Brigade in the Puerto Rico National Guard

to command forces there. The new headquarters came into federal service

on 15 October 1940, but served less than two years without seeing combat.

In July 1942 the Caribbean Defense Command inactivated the brigade and replaced

it with the Puerto Rican Mobile Force.22

-

- Besides infantry divisions and brigades,

the National Guard maintained four partially organized cavalry divisions

and one cavalry brigade. As these forces did not fit into any current war

plans, the General Staff initiated a study in August 1940 to determine the

Guard's requirements for horse and mechanized units. It concluded that the

Guard needed both types of organizations, but not four horse cavalry divisions.

At the time of the study it was rumored that the personnel from two cavalry

divisions would form the nuclei of two armored divisions. The states, however,

objected to the loss of cavalry regiments, and Armored Force leaders believed

that armored divisions were too big and complicated for the Guard. On 1

November 1940 the National Guard Bureau withdrew the allotment of the 21st

through 24th Cavalry Divisions, which in effect disbanded them. Some of

their elements were used to organize mechanized cavalry regiments. After

November the 56th Cavalry Brigade, a Texas unit, remained the only large

unit authorized horses in the National Guard. It entered federal service

before the end of the year.23

-

- With 18 infantry divisions, 1 infantry

brigade, and 1 cavalry brigade from the National Guard undergoing training

in 1941, a crisis soon developed regarding their future. The 1940 law had

authorized the federalization of the Guard for only one year, and that period

was about to expire for some units. But the units were now filled with both

draftees and guardsmen, and the release of the latter from federal service

would completely break up these units. In the summer of 1941 the War Department

thus prevailed upon Congress to extend the Guard units and men on active

duty. This decision allowed Marshall to conduct the great General Headquarters

Maneuvers in the summer and fall of 1941.24

- [153]

-

- Using the protective mobilization

plan, in 1941 the Army also proceeded to increase the number of cavalry,

armored, and infantry divisions in response to the growing threat of war.

The Regular Army organized a second cavalry division against a backdrop

of domestic politics. As a result of debates over increasing the size of

the Army, Congress had provided "That no Negro because of race, shall

be excluded from enlistment in the Army for service with colored military

units now organized and to be organized." 25

In the midst of the 1940 presidential campaign prominent black leaders complained

bitterly to President Franklin D. Roosevelt about the limited number of

black units. Under political pressure the Army activated the 2d Cavalry

Division at Fort Riley, Kansas, on 1 April 1941, with one black and one

white brigade.26

-

- Armored divisions were viewed as

far more essential than cavalry divisions. As early as 6 August 1940, Chaffee,

commanding the Armored Force, planned more armored divisions, and he directed

the 1st and 2d Armored Divisions to maintain a 25 percent overstrength as

cadre for additional units. In January 1941 the War Department approved

the establishment of two more armored divisions, and on 15 April the Armored

Force activated the 3d and 4th at Camp Beauregard, Louisiana, and Pine Camp

(later Fort Drum), New York, respectively. Shortly thereafter plans surfaced

for two more armored divisions. The 5th Armored Division, added to the rolls

in August, became a reality in October, and the 6th joined the force in

January 1942.27

-

- The European war clearly demonstrated

a need to have antitank forces. Marshall had decided that all units had

an antitank role, but he also recognized the requirement for specific counter-armor

units. He did not want to assign them to an existing arm because their organization,

tactical doctrine, and development seemed beyond the scope of any one arm.

The problem struck the new Assistant Chief of Staff, G- 3, Brig. Gen. Harry

L. Twaddle, as similar to that of employing the machine gun during World

War I. As an expedient, separate machine gun battalions had been established,

although the guns were prevalent in all combat formations. Twaddle believed

that antitank units, which would not be a part of any existing arm, should

also be organized as an expedient to provide the strongest antitank capability

possible; later the Army could sort out whether they were infantry or field

artillery weapons.28

-

- Twaddle's staff developed plans

to provide four antitank battalions for each existing division. One battalion

would serve with the division and the three others would be held at higher

echelons for employment as needed. For the upcoming maneuvers the War Department

authorized the formation of provisional antitank battalions in June 1941,

using the antitank guns from field artillery battalions. The following December,

after the maneuvers, the battalions were made permanent organizations and

redesignated as tank destroyer units to indicate their offensive nature.

They were not divisional elements, as recommended by First, Third,

- [154]

- Tanks of the 68th Armored, 2d Division, participate in the Louisiana

Maneuvers, 1941

-

- and Fourth Army commanders after

the 1941 maneuvers, but assigned to General Headquarters (GHQ). This arrangement

placed the units outside the control of the existing arms, thus creating

basically a new homogeneous antitank force. The independent tank destroyer

battalions would later prove an organizational error, denying division commanders

a major resource that they habitually needed. It did, however, focus attention

on an area that was a growing tactical concern.29

-

- The possible theater of operations

shifted from the Western Hemisphere to the Pacific in 1941 as relations

deteriorated between the United States and Japan. To be prepared for that

contingency, Lt. Gen. Walter C. Short, commanding the Hawaiian Department,

requested permission to expand the square Hawaiian Division into two triangular

infantry divisions with the primary mission of defending Oahu, the most

populous of the islands and a major base of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. Recognizing

that the Regular Army lacked the units required for the reorganization,

Short proposed that Guard units complete the two divisions. The department

approved Short's proposal, and on 1 October he reorganized and redesignated

the Hawaiian Division as the 24th Infantry Division and activated the 25th

Infantry Division. Elements of the Hawaiian Division were distributed between

the two new divisions, and, as planned, each had one Hawaii National Guard

and two Regular Army infantry regiments. Divisional strengths hovered around

11,000 men.30

- [155]

- Provisional Tank Destroyer, Fort Meade, Maryland, 1941

-

- About the same time the Army introduced

two new distinctions into its official lexicon. First, the word "infantry"

was made a part of the official designation of such divisions. In the past

the word infantry was understood, but, because of the expanding variety of

divisions, the Army needed some way to distinguish among them. The adjutant

general specified that unit designations thus include the major combat element

or even the type of unit when the former was not sufficiently descriptive.

Some divisions issued general orders introducing infantry as a part of the

official name, and the adjutant general constituted the 25th specifically

as an infantry division. The term, however, was not officially added to the

tables of organization, documents that technically controlled the names of

units, until 1942.31

-

- The second change concerned the

meaning of the term "Army of the United States." Before 1940 it

had embraced the Regular Army, the National Guard while in the service of

the United States, and the Organized Reserves. With the growth of the force,

the term Army of the United States was broadened to encompass units that

had not been a part of the mobilization plans during the inter-war years.

The 25th Infantry Division was the first division-size unit activated under

the expanded definition.32

-

- In the Pacific area, the defense

of the Philippine Islands presented unique problems. They were too distant

and too scattered for ground defense. Nevertheless, Marshall asked the local

commander, General Douglas MacArthur, whether

- [156]

- Divisions Active on 7

December 1941

-

| Component |

Division |

Date Activated or Inducted Into Federal

Service |

Location |

| RA |

1st Infantry |

* |

Fort Devens,

Mass. |

| RA |

2d Infantry |

* |

Fort Sam

Houston, Tex. |

| RA |

3d Infantry |

* |

Fort Lewis,

Wash. |

| RA |

4th Infantry |

1 June 1940 |

Fort Benning,

Ga. |

| RA |

5th Infantry |

16 October

1939 |

Fort Custer,

Mich. |

| RA |

6th Infantry |

10 October

1939 |

Fort Leonard

Wood, Mo. |

| RA |

7th Infantry |

1 July 1940 |

Fort Ord,

Calif. |

| RA |

8th Infantry |

1 July 1940 |

Fort Jackson,

S.C. |

| RA |

9th Infantry |

1 August

1940 |

Fort Bragg,

N.C. |

| RA |

24th Infantry |

* |

Schofield

Barracks, Hawaii |

| AUS |

25th Infantry |

1 October

1941 |

Schofield Barracks,

Hawaii |

| NG |

26th Infantry |

16 January

1941 |

Camp Edwards,

Mass. |

| NG |

27th Infantry |

15 October

1940 |

Fort McClellan,

Ala. |

| NG |

28th Infantry |

17 February

1941 |

@Indiantown Gap

Military Reservation,

Pa. |

| NG |

29th Infantry |

3 February1941 |

@Fort George

G. Meade, Md. |

| NG |

30th Infantry |

16 September

1940 |

Fort Jackson,

S.C. |

| NG |

31st Infantry |

25 November

1940 |

Camp Blanding,

Fla. |

| NG |

32d Infantry |

15 October

1940 |

Camp Livingston,

La. |

| NG |

33d Infantry |

5 March

1940 |

Camp Forrest,

Tenn. |

| NG |

34th Infantry |

10 February

1941 |

Camp Claiborne,

La. |

| NG |

35th Infantry |

23 December

1940 |

Camp Joseph

T. Robinson, Ark. |

| NG |

36th Infantry |

25 November

1940 |

Camp Bowie,

Tex. |

| NG |

37th Infantry |

16 October

1940 |

Camp Shelby,

Miss. |

| NG |

38th Infantry |

17 January

1941 |

Camp Shelby,

Miss. |

| NG |

40th Infantry |

3 March

1941 |

Fort Lewis,

Wash. |

| NG |

41st Infantry |

16 September

1940 |

Fort Lewis,

Wash. |

| NG |

43d Infantry |

24 February

1941 |

Camp Shelby,

Miss. |

| NG |

44th Infantry |

16 September

1940 |

Fort Dix,

N.J. |

| NG |

45th Infantry |

16 September

1940 |

Camp Berkeley,

Tex. |

| RA |

1st Cavalry |

* |

Fort Bliss,

Tex. |

| RA |

2d Cavalry |

15 April

1941 |

Fort Riley,

Kans. |

| RA |

1st Armored |

15 July

1940 |

Fort Knox,

Ky. |

| RA |

2d Armored |

15 July

1940 |

Fort Benning,

Ga. |

| RA |

3d Armored |

15 April

1941 |

Camp Beauregard,

La. |

| RA |

4th Armored |

15 April

1941 |

Pine Camp,

N.Y. |

| RA |

5th Armored |

1 October

1941 |

Camp Cooke,

Calif. |

-

- NOTES: *Active before 1 September

1939.

- @En route from maneuvers, arrived

at home station 9 December 1941.

- [157]

- General Short reviews the Hawaiian Division, September 1941.

-

- he wanted a Guard division to reinforce

his ground units. MacArthur instead asked for authority to reorganize the

Philippine Division as a triangular unit and to fill its regimental combat

teams with Regular Army personnel. Since the division's formation in 1921,

most of its enlisted men were Philippine Scouts, and he wanted to use them

to help organize new Philippine Army units. Marshall approved the request

and initiated plans to send two infantry regiments, two field artillery battalions,

a headquarters and headquarters battery for the division artillery, a reconnaissance

troop, and a military police platoon to the islands. The Japanese attack on

Pearl Harbor and other installations in the Pacific on 7 December 1941 aborted

the plan.33

-

- At the time of the attack the Army

had thirty-six divisions, excluding the Philippine Division (Table 12),

and two brigades on active duty. The nation was thus much better prepared

for war in December 1941 than in April 1917.

-

-

- The Japanese attack and the ensuing

American declaration of war on Japan, Germany, and Italy immediately shifted

the focus of Army planning from hemispheric defense to overseas operations.

The first priority was to streamline the square National Guard divisions.

Even before the attack Marshall had asked Twaddle to explore that possibility,

believing that the surplus

- [158]

- units could be used overseas or to

create new organizations as some divisions appeared to lend themselves to

expansion. In November 1941 Twaddle took the 121st and 161st Infantry from

the square 30th and 41st Divisions and reassigned them. At the time of the

attack on Pearl Harbor he had replaced the 34th Infantry with the 121st Infantry

in the 8th Division and had slated the 34th and the 161st for deployment to

the Philippines. The day after the attack he attached one infantry regiment

each from the 32d, 33d, and 36th Divisions to the Fourth Army to augment the

forces protecting the West Coast. A week later the 124th Infantry from the

31st Division was assigned to the Infantry School at Fort Benning, Georgia.34

-

- On 31 December 1941, Marshall asked

Lt. Gen. Lesley J. McNair, Chief of Staff, GHQ, to investigate bottlenecks

that had developed during attempts to ship units overseas. Six days later

McNair told Marshall that the Guard divisions used to organize task forces

going overseas had "overheads" (noncombat personnel) that approached

the "grotesque" and recommended their immediate reorganization

as triangular divisions.35

Shortly thereafter Marshall directed the staff to prepare plans for reorganizing

thirteen of the eighteen Guard divisions, omitting five because they already

had orders for overseas duty. Ultimately either Marshall or his deputy approved

the conversion to triangular formations of all Guard divisions except one,

the 27th, which was targeted for Hawaii where that command was planning

to receive a square division. Twaddle's staff prepared instructions for

the reorganization, which he sent to the division commanders for comment.

Units that the states had not adequately supported were to be eliminated.36

-

- The reorganization began with the

32d and 37th Divisions on 1 February 1942. All infantry brigades were disbanded

except the 51st, an element of the 26th Division. One infantry brigade headquarters

company from each division was converted and redesignated as the division

reconnaissance troop, except in the 28th and 43d Divisions. In the 43d both

infantry brigade headquarters companies were disbanded, and in the 28th

one brigade headquarters company became the reconnaissance troop and the

other the division's military police company. The headquarters and headquarters

battery of each field artillery brigade became the headquarters and headquarters

battery, division artillery. Other divisional elements were reorganized,

redesignated, reassigned, or disbanded. The reorganization was completed

on 1 September 1942 when the 27th Division, which had arrived in Hawaii

that summer, adopted the triangular configuration.37

-

- In January 1942 the War Department

created Task Force 6814 from surplus National Guard units to help defend

New Caledonia, a French possession in the Pacific. Among these units were

the 51st Infantry Brigade headquarters and the 182d Infantry from the 26th

Division (Massachusetts) and the 132d Infantry from the 33d Division (Illinois).

The units arrived in New Caledonia in March and others quickly followed.

Eventually the Operations Division (OPD), War Department General Staff,38

instructed Maj. Gen. Alexander M. Patch, commanding Task Force 6814, to

organize a division. Because he lacked men and equipment for a

- [159]

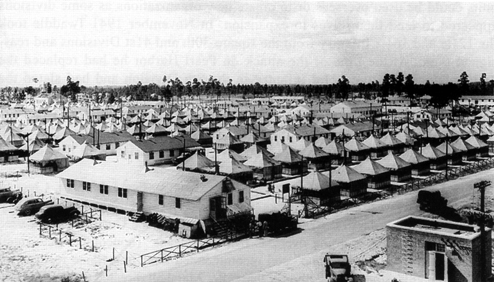

- Camp Shelby, Mississippi, home of the 37th and 38th Divisions, 1941

-

- complete table of organization unit,

the staff decided that the division would carry a name rather than a numerical

designation. Titles such as "Necal" and "Bush" surfaced,

but Patch turned to the men assigned to the task force for suggestions. Pfc.

David Fonesca recommended "Americal" from the phrase "American

Troops on New Caledonia," and on 27 May 1942 Patch activated the Americal

Division.39

-

-

- With the attack on Pearl Harbor

on 7 December the "great laboratory" phase for developing and

testing organizations, about which Marshall wrote in the summer of 1941,

closed, but the War Department still had not developed ideal infantry, cavalry,

armored, and motorized divisions. In 1942 it again revised the divisions

based on experiences gained during the great GHQ maneuvers of the previous

year. As in the past, the reorganizations ranged from minor adjustments

to wholesale changes.

-

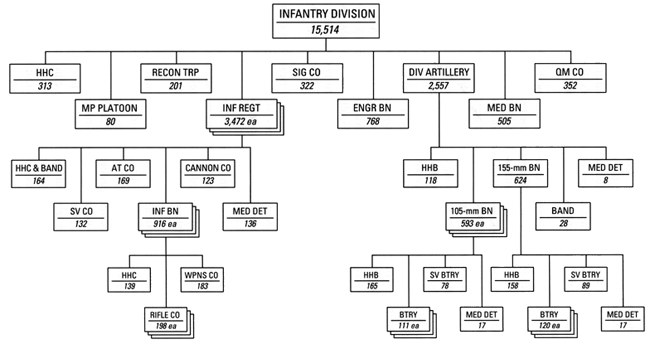

- The Chief of Infantry, Maj. Gen.

Courtney H. Hodges, proposed the principal change in the infantry division,

the addition of a cannon company to the infantry regiment to provide it

with artillery that could move forward as rapidly as the troops advanced

on foot. The Chief of Field Artillery, Maj. Gen. Robert M. Danford, opposed

the idea, contending that all cannon should be in artillery units. McNair,

appointed Chief of Army Ground Forces (AGF) in March 1942 and responsible

for organizing and training all ground combat units, also objected. For

five years the division had been in a state of flux in an effort to make

it light

- [160]

- and therefore easier to handle.

Command and control had replaced road space as the basic factor behind divisional

size. Constant changes were destroying those goals. McNair advised Marshall

that the division should have a maximum of 15,000 men with the arms being

fixed accordingly and that it should not be increased in size at the insistence

of arm-conscious chiefs. His view did not prevail. Hodges won the armament

battle, and a cannon company became a part of each infantry regiment.40

-

- The addition of regimental cannon

companies was not the only change in the infantry division. To increase

artillery firepower, the tables provided twelve rather than eight 155-mm.

howitzers and eliminated the 75-mm. guns, which had been assigned to tank

destroyer units, as antitank weapons. To protect the division from hostile

aircraft, the number of .50-caliber machine guns rose from sixty to eighty-four.

Improved reconnaissance capabilities were also added to the infantry division,

with ten light armored cars replacing the sixteen scout cars in the reconnaissance

troop. In the infantry regiments themselves, intelligence and reconnaissance

platoons replaced intelligence platoons.41

-

- The GHQ maneuvers of 1941 had also

revealed a need for more trucks in the division. McNair, however, believed

that the suggested number of trucks was excessive, requiring too much space

on ships when sent overseas. Although the number of trucks was cut at his

insistence, the division still had 315 more vehicles under the 1942 tables

than those of 1940. Finally, the new tables split the division headquarters

and military police company into two separate units, a headquarters company

and a military police platoon. These changes together added about 270 men

to the division (Chart 15).42

-

- Modifications continued even after

publication of the new tables of organization for the infantry division.

Army Ground Forces withdrew the small ordnance maintenance platoon from

the headquarters company of the quartermaster battalion and reorganized

the unit as a separate ordnance light maintenance company to improve motor

repair. After this change, food and gasoline supply functions became the

responsibility of the regiments and separate battalions in the division,

and the quartermaster battalion was reduced to a company to provide trucks

for water supply and emergency rations and to augment the division's ability

to move men and equipment.43

-

- The cavalry division retained its

square configuration after the 1941 maneuvers, but with modifications. The

division lost its antitank troop, the brigades their weapons troops, and

the regiments their machine gun and special weapons troops. These changes

brought no decrease in divisional firepower, but placed most weapons within

the cavalry troops. The number of .50-caliber machine guns was increased

almost threefold. In the reconnaissance squadron, the motorcycle and armored

car troops were eliminated, leaving the squadron with one support troop

and three reconnaissance troops equipped with light tanks. These changes

increased the division from 11,676 to 12,112 officers and enlisted men.44

- [161]

- Infantry Division, 1 August 1942

-

-

- [162]

- The GHQ maneuvers also had a significant

impact on the organization of the armored division. The exercises led to numerous

situations that called for infantry, artillery, and armor to form combat teams,

but the division lacked the resources to organize them. The division as organized

was heavy in armor but too light in both infantry and artillery. The armored

brigade complicated the command channel, while the service elements needed

greater control. To correct these weaknesses, the Armored Force, under the

direction of Maj. Gen. Jacob L. Devers, dramatically reorganized the division

(Chart 16). The armored brigade headquarters and one armored regiment

were eliminated, and the remaining two armored regiments were reorganized

to consist of one light and two medium tank battalions each. Three self-propelled

105-mm. howitzer battalions replaced the field artillery regiment and battalion,

and control of the division artillery passed to an artillery section in the

division headquarters. The infantry regiment was reorganized to consist of

three battalions of three companies each, and trucks replaced armored personnel

carriers. The engineer battalion was authorized four, rather than three, line

companies and a bridge company. Two combat command headquarters were authorized

but were to have no assigned units, allowing the division commander to build

fighting teams as the tactical situation dictated yet still have units in

reserve. Maintenance and supply battalions replaced ordnance and quartermaster

battalions, the maintenance unit taking over all motor repairs in the division.

For better control of the service elements, division trains were added and

placed under the command of a colonel. A service company was also added to

provide transportation and supplies for the rear echelon of the division headquarters

company.45

-

- The 4th Division had tested the

motorized structure along with attached tank, antitank, and antiaircraft

artillery units during the Carolina portion of the GHQ maneuvers in the

fall of 1941. At their termination, the division commander, Brig. Gen. Fred

C. Wallace, reported to General Twaddle that the force was "undesirably

large." Furthermore, deficiencies existed in command and control, traffic

control, administrative support, rifle strength, communications, motor maintenance,

ammunition supply, and engineer capabilities. Also, the attached units-tank,

antitank, and antiaircraft artillery battalions-needed to be permanently

assigned to the division.46

-

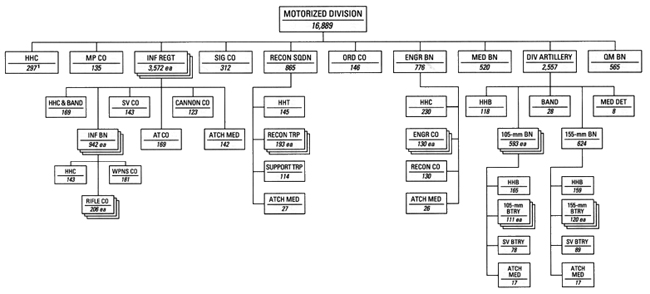

- When the War Department published

new tables of organization for the motorized division in the spring of 1942

(Chart 17), it differed considerably from the structure tested by

Wallace. In those tables, the hand of McNair, who almost always opposed

"special" units, was evident. The division closely resembled an

infantry division. Motorized infantry regiments were to have an organization

similar to standard infantry regiments. Gone were armored half-track personnel

carriers, but the regiment was to have enough trucks to move all its men

and equipment. The division headquarters and headquarters company and the

artillery were identical to their counterparts in the infantry division,

and the reconnaissance battalion was the same as that of the cavalry division.

A reconnaissance company was added to the engineer battalion. The ordnance

unit remained company size,

- [163]

- Armored Division, 1 March 1942

-

- 1 Includes chaplains.

-

- [164]

- Motorized Division, 1 August 1942

-

- 1 The table for a motorized division authorized the division

HHC 297 officers and enlisted men while the one for an infantry division

authorized the unit 313. Both divisions, however, used the same tables for

their headquarters and headquarters company

-

- [165]

- and a military police company was

added. As redesigned, the motorized division fielded nearly 17,000 men. Following

McNair's idea that a unit should have only those resources it habitually needed,

the division, as other infantry divisions, lacked organic tank, tank destroyer,

and antiaircraft artillery battalions.47

-

- Before all the tables for the revised

divisions were published in 1942, the War Department alerted the field commands

about the pending reorganization of their units. Divisions were to adopt

the new configurations as soon as equipment, housing, and other facilities

became available. Most divisions adhered to the revised structures by the

end of 1942.48

-

- In the summer of 1942 the Army organized

a fifth type of division. Between World Wars I and II it had experimented

with transporting units in airplanes, and in 1940 the chief of infantry

studied the possibility of transporting all elements of an infantry division

by air. When the Germans successfully used parachutists and gliders in Holland

and Belgium in 1940, the Army reacted by developing parachute units. The

mass employment of parachutes and gliders on Crete in 1941stimulated the

development of glider units. Both types of units were limited to battalion

size because tacticians did not envision airborne operations involving larger

units. Brig. Gen. William C. Lee, commander of the U.S. Army Airborne Command,

which had been established to coordinate all airborne training, visited

British airborne training facilities in England in May 1942 and following

that visit recommended the organization of an airborne division.49

-

- At that time the British airborne

division consisted of a small parachute force capable of seizing a target,

such as an airfield, and a glider force to reinforce the parachutists, leaving

the remainder of the division to join those forces through more conventional

means. Lee reported to McNair that the British had found the movement of

ordinary troops in gliders wasteful because about 30 percent of the troops

suffered from air sickness and became ineffective during air-land operations.

Since the British were organizing airborne divisions, in which glider personnel

were to receive the same training as parachutists, Lee suggested the U.S.

Army also organize them. Heeding Lee's suggestion, McNair outlined to Marshall

a 9,000-man airborne division that could have a varying number of parachute

or glider units in accordance with tactical circumstances.50

-

- Although the General Staff accepted

the proposal, it had several reservations. The division selected for the

airborne role had to have completed basic training but should not be a Regular

Army or National Guard unit, as many traditionalists in those components

wanted nothing to do with such an experimental force. For ease of training,

it also had be stationed where air facilities and flying conditions were

good. The 82d Division met the criteria. It was an Organized Reserve unit,

training under Maj. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway, and located at Camp Claiborne,

Louisiana. McNair recommended that it be the basis for two airborne divisions

with the existing parachute infantry regiments assigned to them. For the

designation of the second airborne division, the staff selected the 101st,

an Organized Reserve unit that was not in active military service.51

- [166]

- Paratroopers stage a special demonstration for members of Congress,

Fort Belvoir, Virginia, 1941.

-

- The Third Army and the Airborne

Command executed McNair's recommendation on 15 August 1942. The 82d Infantry

Division (less the 327th Infantry, the 321st and 907th Field Artillery Battalions,

the 82d Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop, and the Military Police Platoon) plus

the 504th Parachute Infantry became the 82d Airborne Division. Concurrently,

the adjutant general disbanded the 101st Division in the Organized Reserve

and reconstituted it in the Army of the United States, activating it as

the 101st Airborne Division at Camp Claiborne, Louisiana. The 502d Parachute

Infantry, the 327th Glider Infantry, and the 321st and 907th Glider Field

Artillery Battalions were assigned as divisional elements. Shortly thereafter

each division was authorized an antiaircraft artillery battalion, an ordnance

company, and a military police platoon. The parachute infantry elements

did not immediately join their divisions, but by early October 1942 all

elements of both divisions assembled at Fort Bragg for training.52

-

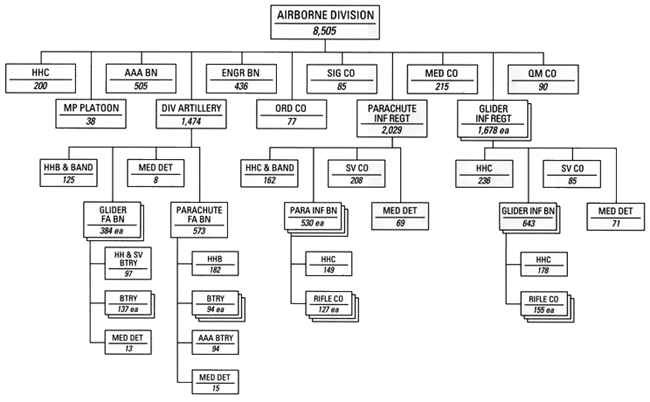

- On 15 October 1942 the War Department

published the first tables of organization for the airborne division (Chart

18). Reflecting the light nature of the unit, the parachute infantry

regiment had only .30-caliber machine guns and 60-mm. and 81-mm. mortars

besides the individual weapons, and its field artillery battalions used

75-mm. pack howitzers. In the division artillery, however, a new antitank

weapon was introduced, the 2.36-inch rocket launcher (the "bazooka").

Transportation equipment ranged from bicycles and handcarts to 2-1/2-ton

trucks,

- [167]

- Airborne Division, 15 October 1942

-

-

- [168]

- but the airborne division had only

401 trucks as opposed to over 1,600 in an infantry division. The new division

numbered 8,505 officers and enlisted men, of whom approximately 2,400 were

parachutists.53

-

- The Airborne Command also trained

smaller parachute and glider units and requested the authority to organize

tactical airborne brigades in 1942. The Deputy Chief of Staff, Lt. Gen.

Joseph T. McNarney, turned down the request, believing that only divisions

should conduct operations involving more than a regiment. The Airborne Command,

nevertheless, organized the 1st Parachute Infantry Brigade, a nondeployable

unit, to assist in training parachute units.54

-

-

- After 7 December 1941 the General

Staff also turned its attention to the future size of the Army and the number

of divisions required to wage and win the war. Some officers believed that

as many as 350 divisions might be needed, while others estimated considerably

fewer. Outside considerations included the manpower needs of the other services

and civilian industry as well as the speed at which divisions could be organized,

equipped, and trained given the limited pool of experienced leaders and

industrial limitations. On 24 November 1942, nearly a year after United

States entered the war, the War Department published a troop basis 55

that called for a wartime force structure of 100 divisions-62 infantry,

20 armored, 10 motorized, 6 airborne, and 2 cavalry-to be organized by 1943

within a total Army force of 8,208,000 men.56

-

- Meanwhile, the Army continued to

expand the number of divisions. Working with tentative troop bases early

in 1942, the General Staff decided to bring the Organized Reserve divisions

into active military service. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed an

executive order calling units of the Organized Reserves into active military

service for the duration of the war plus six months. The order was a public

relations document more than anything else because most Organized Reserve

personnel were already on active duty.57

-

- Members of General Twaddle's staff

next examined the sequence for inducting infantry divisions. They considered

such factors as the number of World War I battle honors earned by units;

the location and availability of training sites, particularly in the corps

areas where divisions were located; and the ability of the Army to furnish

divisional cadres. Based on these considerations, the staff established

a tentative order, beginning with the 77th Division, which had the most

combat service in World War I, and ending with the 103d, which had not been

organized during World War I.58

-

- Meanwhile, corps area commanders

prepared the Organized Reserve units for induction early in 1942 by placing

the infantry divisions under the 1940 tables of organization. Infantry and

field artillery brigades were eliminated, with the headquarters and headquarters

companies of the infantry brigades consolidated to form divisional reconnaissance

troops. As in the National Guard divisions, the

- [169]

- headquarters and headquarters batteries

of the field artillery brigades became the headquarters and headquarters

batteries of the division artillery. Other units within the division were

reduced, redesignated, reassigned, or disbanded to fit the triangular configuration.

The six Organized Reserve cavalry divisions were dropped from the tentative

troop program and disbanded.59

-

- Induction of the infantry divisions

began on 25 March 1942, and by 31 December, twenty-six of the twenty-seven

divisions were on active duty (Table 13). The 97th Infantry Division

was not inducted into active military service until February 1943 because

personnel were not available for its reorganization. Since none of these

divisions had reserve cadre or equipment, the Army Ground Forces had to

rebuild them totally. That process started when the War Department assigned

a commander and selected a parent unit to provide a cadre. Approximately

thirty-seven days before reorganization of the division, the commander and

his staff reported to the unit's station. Officers and enlisted cadre, about

1,400 men from the parent unit, followed some seven days later, and shortly

thereafter the remaining 500 officers arrived. Within five days after the

arrival of all officers and cadre, a stream of about 13,500 recruits began

to report. The division was considered reorganized and active fifteen days

after the first fillers reached the division. Fifty-two weeks of training

followed, which included seventeen weeks of basic and individual training.

The divisions, after their initial fill, were to rely on replacement centers

for personnel.60

-

- Along with the reorganization of

the Organized Reserve units, the War Department expanded the number of divisions

in the Army of the United States. Reversing a post-World War I policy, the

staff planned to activate some all-black divisions to accommodate the large

number of black draftees. On 15 May 1942 Army Ground Forces organized the

93d Infantry Division at Fort Huachuca, Arizona. Although it had the same

number as the provisional Negro unit of World War I, it had no relationship

or lineal tie with the old 93d. Following its activation, the Army Staff

chartered at least three more all-black infantry divisions the 92d, 105th,

and 107th. The 92d Division, the all-black unit of World War I, was to be

reconstituted, but the other two were to be new units. Under the plan, the

93d Infantry Division was to furnish the cadre for the 92d, the 92d for

the 105th, and the 105th for the 107th. Army Ground Forces organized the

92d on 15 October 1942, but a shortage of personnel for worldwide service

units prevented the formation of the others. Eventually the 105th and 107th

Divisions were dropped from the activation list.61

-

- To meet the number of divisions

in the troop basis, the Armored Force activated nine more armored divisions

in 1942, the 6th through the 14th. In organizing them, it followed the same

cadre system as the Army Ground Forces used for infantry divisions.62

-

- With the increased number of armored

divisions, Brig. Gen. Harold R. Bull, the G-3 on the General Staff, discerned

a way to eliminate unwanted cavalry divisions. He suggested to Army Ground

Forces that it consider converting the two

- [170]

- Divisions Activated or

Ordered Into Active Military Service in 19421

-

| Component |

Division |

Date |

Location |

| AUS |

6th Armored |

15 February |

Fort Knox, Ky. |

| AUS |

7th Armored |

1 March |

Camp Polk, La. |

| OR |

77th Infantry |

25 March |

Fort Jackson, S.C. |

| OR |

82d Airborne |

25 March |

Camp Claiborne, La. |

| OR |

90th Infantry |

25 March |

Camp Berkeley, Tex. |

| AUS |

8th Armored |

1 April |

Fort Knox, Ky. |

| OR |

85th Infantry |

15 May |

Camp Shelby, Miss. |

| AUS |

93d Infantry |

15 May |

Fort Huachuca, Ariz. |

| AUS |

Americal |

27 May |

New Caledonia |

| OR |

76th Infantry |

15 June |

Fort George G. Meade,

Md. |

| OR |

79th Infantry |

15 June |

Camp Pickett, Va. |

| OR |

81st Infantry |

15 June |

Camp Rucker, Ala. |

| AUS |

9th Armored |

15 July |

Fort Riley, Kans. |

| AUS |

10th Armored |

15 July |

Fort Benning, Ga. |

| OR |

80th Infantry |

15 July Camp |

Forrest, Tenn. |

| OR |

88th Infantry |

15 July |

Camp Gruber, Okla. |

| OR |

89th Infantry |

15 July |

Camp Carson, Colo. |

| OR |

95th Infantry |

15 July |

Camp Swift, Tex. |

| AUS |

11th Armored |

15 August |

Camp Polk, La. |

| OR |

78th Infantry |

15 August |

Camp Butner, N.C. |

| OR |

83d Infantry |

15 August |

Camp Atterbury, Ind. |

| OR |

91st Infantry |

15 August |

Camp White, Oreg. |

| OR |

96th Infantry |

15 August |

Camp Adair, Oreg. |

| AUS |

101stAirborne |

15 August |

Camp Claiborne, La. |

| AUS |

12th Armored |

15 September |

Camp Campbell, Ky. |

| OR |

94th Infantry |

15 September |

Fort Custer, Mich. |

| OR |

98th Infantry |

15 September |

Camp Breckinridge, Tenn. |

| OR |

102d Infantry |

15 September |

Camp Maxey, Tex. |

| OR |

104th Infantry |

15 September |

Camp Adair, Oreg. |

| AUS |

13th Armored |

15 October |

Camp Beale, Calif. |

| OR |

84th Infantry |

15 October |

Camp Howze, Tex. |

| AUS |

92d Infantry |

15 October |

Fort McClellan, Ala. |

| AUS |

14th Armored |

15 November |

Camp Chaffee, Ariz. |

| OR |

99th Infantry |

15 November |

Camp Van Dorn, Miss. |

| OR |

100th Infantry |

15 November |

Fort Jackson, S.C. |

| OR |

103d Infantry |

15 November |

Camp Claiborne, La. |

| OR |

86th Infantry |

15 December |

Camp Howze, Tex. |

| OR |

87th Infantry |

15 December |

Camp McCain, Miss. |

-

- 1 Table in chronological order.

- [171]

- Regular Army horse divisions to mechanized

cavalry because there was no foreseeable role for horse-mounted units. Maj.

Gen. Mark W Clark, Chief of Staff of Army Ground Forces, disagreed, as did

Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson. The latter opposed the conversion because

the war was worldwide, and he believed that horse cavalry could be useful

in many places, particularly in areas where oil was scarce, a reference to

the other types of divisions that required large quantities of petroleum products.

He also opposed the conversion because of the time required to train new horse

cavalry units. Nevertheless, because of a shortage of men in the summer of

1942, the 2d Cavalry Division was inactivated to permit organization of the

9th Armored Division. White cavalrymen were assigned to the 9th, and the all-black

4th Cavalry Brigade became a nondivisional unit. Later, when preparing troops

for operations in the North African theater, the engineer and reconnaissance

squadrons and the 105-mm. howitzer battalion were withdrawn from the 1st Cavalry

Division and sent to North Africa.63

-

- With the activation of additional

armored divisions, General Twaddle decided to convert some infantry divisions

to motorized divisions. He selected the 6th, 7th, and 8th Divisions for

reorganization, which was accomplished by August 1942. The staff planned

to form three more such divisions that year, but Army Ground Forces reorganized

only the 90th because of shortages in personnel and equipment. On 9 April

1942 the adjutant general officially redesignated the 6th, 7th, and 8th

Divisions as motorized. The 4th Division issued general orders adopting

the "motorized" designation under an Army Ground Forces directive.64

-

- From the fall of 1939 to the end

of 1942 divisional designs fluctuated as the nation prepared for war. The

War Department revised infantry and cavalry divisions, developed and revised

armored and motorized divisions, and created airborne divisions. During

this period of organizational upheaval, the Army retained the basic idea

of three regimental combat teams for the infantry division and adopted the

same concept for the motorized and airborne divisions. The armored division

was held to two fighting teams, as was the horse cavalry division. Many

officers, however, wanted to eliminate the latter because they saw no role

for the horse on the modern battlefield. The trend within all types of divisions

was to increase firepower and standardize divisional elements so that they

could be interchanged. Organizational questions remained, however, such

as the nature and location of antitank weapons or the amount of organic

transportation in any tactical unit. The period proved fruitful, for the

Army organized the divisions needed to pursue the war. By 31 December 1942

the Army had fielded 1 cavalry, 2 airborne, 5 motorized, 14 armored, and

51 infantry divisions, for a total of 73 active combat divisions.

- [172]

Endnotes

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

page created 29 June 2001

Return to the

Table of Contents

-