Chapter V:

A Return to the Past; A Look to

the Future

Nor can it be questioned that the

Division as now organized and composed . . . of foot, animal, and motor elements,

all with varying rates of speed, is uneconomical, unwieldy and unadapted to

the demands of modern mobile warfare.

After establishing post-World

War I divisions, the Army experienced a prolonged period of stagnation

and deterioration. The National Defense Act of 1920 authorized a Regular

Army of 296,000 men, but Congress gradually backed away from that

number. As with the Regular Army, the National Guard never recruited its

authorized 486,000 men, and the Organized Reserves became merely a pool

of reserve officers. The root of the Army's problem was money. Congress

yearly appropriated only about half the funds that the General Staff

requested. Impoverished in manpower and funds, infantry and cavalry

divisions dwindled to skeletal organizations.

Meanwhile, the General Staff and

service schools searched for a divisional structure, particularly for

the infantry, that best suited the conditions of modern warfare. Like

their European counterparts, American military planners remembered,

above all, the indecisiveness that had dominated the battlefield in

World War I. The result had been a protracted war of hitherto unimagined

devastation. The search for a sound divisional organization was part of

the effort to find the means of restoring decisiveness to warfare.

Otherwise, victors might suffer as much as, or even more than, the

vanquished. These considerations drew attention especially to various

means of improving the division's mobility and maneuverability so that

the Army could avoid future wars of position that would force it to

adopt the bloody strategy of attrition.

Between 1923 and 1939 divisions

gradually declined as fighting organizations. After Regular Army

divisions moved to permanent posts, the War Department modified command

relationships between divisional units and the corps areas. It placed

elements of the 1st and 3d Divisions and the 8th, 10th,

[109]

26th Division parade, Fort Devens, Massachusetts, 1925

12th, 14th, 16th, and 18th

Infantry Brigades directly under the corps area commanders, making

division and brigade commanders responsible only for unit training. They

were limited to two visits per year to their assigned elements-and that

only if corps area commanders made funds available. Later, as a further

economy move, the War Department reduced the number of command visits to

one per year, a restriction that effectively destroyed the possibility

of training units as combined arms teams.2

In July 1926 the commander of

the 1st Division, Brig. Gen. Hugh A. Drum, wrote to the Second Corps

Area commander, Maj. Gen. Charles P. Summerall, that "it is not an

exaggeration to say that the division as a unit exists only on

paper."

3

Drum requested the return of all administrative,

logistical, and disciplinary functions for his divisional elements

within the corps area and authority to visit each divisional regiment

once a month and each brigade every three months. He also wanted to

organize a proper division headquarters. Summerall concurred with Drum's

request, but Chief of Staff Maj. Gen. John L. Hines denied it in the

interest of economy and simplicity of administration, supply, and

discipline. On 31 December 1926 Summerall, by then Chief of Staff,

reversed the decision and gave Drum command of all 1st Division units in

the Second Corps Area and permission to reorganize the divisional

headquarters. Drum could also coordinate inspection arrangements with

other corps area commanders where his units were stationed. The

following July Summerall restored the same privileges to the 3d

Division's commander,

[110]

General Summerall

Brig. Gen. Richmond P. Davis, at

Fort Lewis, Washington. Brigade commanders, however, were not granted

similar authority.4

While discussing the need to

reconstitute the 1st Division as a combat unit, Drum stressed the

importance of building esprit. Unfortunately, the few tangible symbols

the Army had used to enhance morale were initially denied to divisions

and brigades after the war. Regular Army soldiers returning from France

were not allowed to wear divisional shoulder sleeve insignia because

they "cluttered" the uniform. The men appealed to Secretary of

War Newton D. Baker, who subsequently approved the use of shoulder

sleeve insignia throughout the Army. When a division adopted a

"patch" design, soldiers put it on their uniforms and

emblazoned it on their divisional flag. The other item, the campaign

streamer, representing participation in a major operation was denied to

headquarters of divisions and brigades because they were command and

control units rather than fighting organizations. Although the policy

was contested, it was not until after the 1st and 3d Divisions

reestablished effective headquarters that the War Department granted

division and brigade headquarters the right to display on their flags

streamers symbolizing the campaigns in which they had directed their

subordinate units.5

A sharp decline in divisional

readiness occurred after 1922, when Congress again cut the Regular

Army's size, this time to 136,000 officers and enlisted men. The Chief

of Staff, General of the Armies John J. Pershing, reduced the strength

of the infantry division from 11,000 to 9,200 men, but he did not

authorize the inactivation of any divisional elements. Four years later

Congress expanded the Army Air Corps without a corresponding increase in

the Army's total strength. Rather than cut the size of ground combat

units, the War Department turned again to inactivating units. The Panama

Canal Division lost an infantry regiment, the 8th Brigade an infantry

battalion, and the 16th Brigade two infantry battalions. Given

continuing personnel shortages, the chief of infantry complained in 1929

that not another man could be taken from his units if they were to

conduct effective training. Therefore, another round of inactivations

took place. The 8th, 10th, 12th, 14th, and 18th Brigades and the

Philippine Division each lost a battal-

[111]

ion. A year later the Philippine

Division inactivated an infantry brigade headquarters, and in 1931 the

division lost another infantry regiment.6

Infantry divisions also suffered

shortages in the area of combat support. By 1930 the 1st and 2d

Divisions and the Philippine Division had the only active medical

regiments in the Regular Army, and they were only partially organized.

During the previous year the War Department had removed the air squadron

and its attached photographic section from the division. Simplicity of

supply, maintenance, and coordination and better use of personnel

justified the reduction. Offsetting that loss, a small aviation section

was added to the division headquarters to coordinate air activities

after air units were attached. In 1931, to provide quartermaster

personnel for posts and stations in the United States, the quartermaster

train in each active division except the 2d was reduced to two motor

companies and a motor repair section. Besides these units the 2d

retained one wagon company. No train headquarters remained active.7

Unlike the other organizations,

in theory divisional field artillery was increased during the interwar

years. Until 1929 the Army maintained two 75-mm. gun regiments for the 1st, 2d, and 3d Divisions and a battalion of 75s each for the Panama

Canal Division, the Philippine Division, and the separate infantry

brigades. The Hawaiian Division fielded one 155-mm. howitzer and two

75-mm. gun regiments, all motorized. During 1929 Summerall restored the

155-mm. howitzer field artillery regiment to all infantry divisions.

Although the 155-mm. howitzer still lacked the mobility of the 75-mm.

gun, the change made divisional artillery, in theory, commensurate with

that found in foreign armies.8

Besides a shortage of personnel,

the 2d Division, the only division housed on one post in the United

States, lacked adequate troop quarters. Living conditions at its home,

Fort Sam Houston, Texas, were deplorable for both officers and enlisted

men by the mid-1920s. To remedy the situation the War Department decided

to break up the division in 1927 and move its 4th Brigade to Fort D. A.

Russell, Wyoming, where suitable quarters were available. That move left

only the Hawaiian Division concentrated at one post, Schofield Barracks,

a situation that continued until the Army began to prepare for World War

II. Thus, despite the wishes of Army leaders, by 1930 the Army was again

scattered throughout the country in a number of isolated bases.9

The cavalry division illustrated

other aspects of the Army's dilemma between realism and idealism. In

1923 the 1st Cavalry Division held maneuvers for the first time,

intending to hold them annually thereafter. However, financial

constraints made that impossible. Only in 1927, through the generosity

of a few ranchers who provided free land, was the division able to

conduct such exercises again.10

In 1928 Maj. Gen. Herbert B.

Crosby, Chief of Cavalry, faced with personnel cuts in his arm,

reorganized the cavalry regiments, which in turn reduced the size of the

cavalry division. Crosby's goal was to decrease overhead while

maintaining or increasing firepower in the regiment. After the

reorganization the cavalry regiment consisted of a headquarters and

headquarters troop, a machine gun troop,

[112]

Officers quarters, Fort Sam Houston, Texas; below, 1st Cavalry

Division maneuvers.

[113]

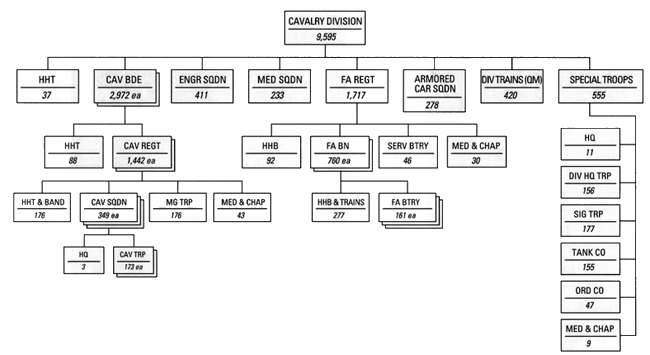

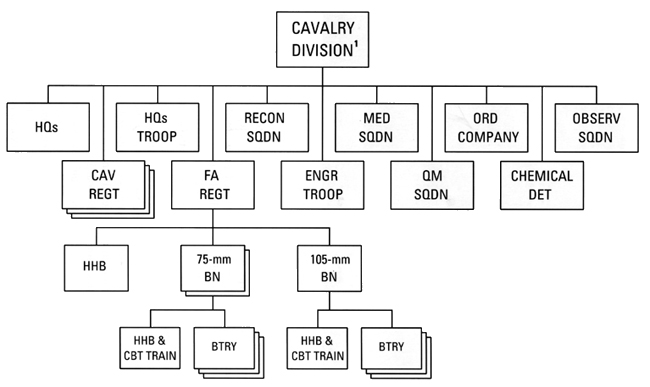

Cavalry Division, 1928

[114]

and two squadrons each with two

troops. The cavalry brigades' machine gun squadrons were inactivated,

while the responsibility for training and employing machine guns fell to

the regimental commanders, as in the infantry.11

About the same time that Crosby

cut the cavalry regiment, the Army Staff, seeking to increase the

usefulness of the wartime cavalry division, published new tables of

organization for an even larger unit. The new structure summarized

changes made in the division since 1921 (Chart 7), which involved

increasing the size of the signal troop, expanding the medical unit to a

squadron, and endorsing Crosby's movement of the machine gun units from

the brigades to the regiments. A divisional aviation section, an armored

car squadron, and tank company were added, and the field artillery

battalion was expanded to a regiment. Divisional strength rose to 9,595.

Although the new tables had little impact on the peacetime cavalry

structure, the 1st Cavalry Division did eventually receive one troop of

an experimental armored car squadron, and a field artillery regiment

replaced its field artillery battalion.12

Even with austere conditions,

the Army did not lose sight of its tactical missions. For example, Maj.

Gen. Preston Brown, commander of the Panama Canal Department, urged the

replacement of the Panama Canal Division with Atlantic and Pacific

command groups. Having examined the supply system, the probable tactical

employment of troops, and the advantages of other command systems, he

decided that a divisional structure did not represent the best solution

in the Canal Zone. The War Department agreed to inactivate the division

headquarters in 1932 with the understanding that special tables of

organization would be kept on file to facilitate the reorganization of

the division within a few hours. Such a situation, however, never

occurred, and the division remained inactive.13

The condition of reserve

divisions paralleled that of the Regular Army. In 1924, three years

after the states began reorganizing the National Guard divisions, the

Militia Bureau suspended federal recognition of new units because of the

chronic lack of money. The suspension lasted two years, until Secretary

of War Dwight R Davis lifted it to provide additional units for the

states. That decision permitted further organization of the 40th

Division (California), the least developed of all the Guard infantry

divisions. The repeal also allowed Minnesota and New York to organize

two infantry brigade headquarters, the 92d and 93d, respectively, for

nondivisional units to meet mobilization needs.14

Infantry divisions in the

National Guard remained basically stable organizations despite being

extremely under strength, and before 1940 only a few regimental changes

were made. In most divisions the artillery brigade's ammunition train

was not authorized because it had an exclusively wartime mission. As in

the Regular Army, the 155-mm. howitzer regiment was authorized in 1930,

and by mid-1937 all divisions had a federally recognized 155-mm.

howitzer regiment or

[115]

Allotment of National Guard

Cavalry Brigades, 1927

| Corps Area |

Unit |

States Supporting a Brigade |

| First |

59th |

Massachusetts and New

Jersey |

| Second |

51st |

New York |

| Third |

52d |

Pennsylvania |

| Fourth |

55th |

Louisiana, Tennessee,

North Carolina, and Georgia |

| Fifth |

54th |

Ohio and Kentucky |

| Sixth |

53d |

Wisconsin, Illinois, and

Michigan |

| Seventh |

57th |

Iowa and Kansas |

| Eighth |

56th |

Texas |

| Ninth |

58th |

Wyoming and Idaho |

part of one. The strength of

infantry divisions varied, but no division reached the 11,000 men

prescribed in the peacetime National Guard tables of organization. The

nadir was in 1926, following the suspension of federal recognition. By

1939 Guard infantry divisions averaged 8,300 troops each.15

National Guard cavalry divisions

proved unsatisfactory because they were scattered over too large an area

for effective training. The Militia Bureau first attacked the problem in

1927, when it realigned some divisional elements to reduce the

geographic size of the divisions. Two years later the bureau limited

cavalry formations to brigade-size units, assigning one brigade to each

corps area (Table 11). The formation of the 59th Cavalry Brigade

was authorized to meet the need for the additional brigade called for in

the plan. At that time the bureau withdrew federal recognition from the

22d Cavalry Division headquarters, the only cavalry division to have a

federally recognized headquarters. Unlike Regular Army cavalry

regiments, Guard regiments retained their six line troops, except those

in the 52d Cavalry Brigade, whose regiments were able to recruit and

maintain sufficient personnel to support nine troops.16

Brigades remained the largest

cavalry units in the Guard until the mid-1930s, when Congress authorized

an increase in its strength. In 1936 the National Guard Bureau, formerly

the Militia Bureau, returned to federally recognizing cavalry division

headquarters. By mid-1940 the bureau had federally recognized

headquarters for the 22d, 23d, and 24th Cavalry Divisions, but not for

the 21st. At that time the 21st consisted of the 51st and 59th Cavalry

Brigades, the 22d of the 52d and 54th, the 23d of the 53d and 55th

Brigades, and the 24th of the 57th and 58th Cavalry Brigades; the 56th

Cavalry Brigade served as a nondivisional unit.17

The Organized Reserves

maintained infantry and cavalry divisions that were authorized a full

complement of officers but only enlisted cadres. Many divisions met or

exceeded their manning levels for officers, but enlisted strength fell

below

[116]

cadre level. In 1937 Secretary

of War Harry W Woodring held the opinion that the dearth of enlisted men

kept the Organized Reserves from contributing much to mobilization.

Under these conditions effective unit training was impossible.18

Mobilization underpinned the

maintenance of divisions, but the Army's preparedness program lacked

substance. Undermanned divisions had no higher command headquarters

despite ambitious plans to group all 54 infantry divisions in the United

States into 18 Organized Reserve army corps and these corps into 6

Organized Reserve armies with each army also having 2 cavalry divisions.

In 1927 the General Staff began to shift toward more realistic war

plans. When division and corps area commanders met in Washington to

discuss Army programs that year, one of the topics they examined was the

status of Regular Army divisions and brigades. The senior officers

believed that reinforced brigades serving as nuclei of divisions were

impractical. Chief of Staff Summerall argued that to mobilize a skeletal

division (a reinforced brigade) would take the same amount of time as

organizing a completely new division since both would have to be filled

with recruits.19

In August 1927 the staff

released new war plans for the Regular Army that reassigned the active

brigades of the 8th, 9th, and 7th Divisions to the 4th, 5th, and 6th

Divisions, respectively, and the inactive brigades of the last three

divisions to the first three. These were paper transactions only. In an

emergency, however, the Regular Army would now be able to field the 1st through the 6th Divisions. For the 4th, 5th, and 6th, it needed only to

activate divisional headquarters and support units. But with no station

changes, the Army leadership lost further sight of an important World

War I lesson: the need to have divisions concentrated for combined arms

training.20

Also in 1927, for echelons above

divisions in the Regular Army, the adjutant general constituted one

army, one cavalry corps, and three army corps headquarters. In addition,

the 3d Cavalry Division, a new Regular Army unit, was added to the rolls

to complete the cavalry corps. No army corps, cavalry corps, or army

headquarters was organized at that time, but moving these units in the

mobilization plans from the Organized Reserve to the Regular Army

theoretically made it easier to organize the units in an emergency. The

Organized Reserve units, after all, were to be used to expand the Army

following the mobilization of Regular Army and National Guard units.21

With increased tensions in the

Far East and the rearmament of European nations, Chief of Staff General

Douglas MacArthur scrapped existing plans for echelons above divisions

and created an army group in 1932. He established General Headquarters

(GHQ), United States Army, with himself as commander, and ordered the

activation of four army headquarters, one each for the Atlantic and

Pacific coasts and the Mexican and Canadian borders (Map 2). To the four

[117]

[118-119]

army headquarters he assigned

eighteen army corps headquarters, and to the corps headquarters the

fifty-four infantry divisions. The Regular Army cavalry corps, which

comprised the 1st, 2d, and 3d Cavalry Divisions, was assigned to the

Fourth Army, and the four mounted National Guard divisions to the GHQ.

Organized Reserve cavalry divisions remained in those areas where the

armies were to raise units.22

In planning for the four armies,

Brig. Gen. Charles E. Kilbourne, chief of the War Plans Division,

suggested to MacArthur that he drive home to the president, the

secretary of war, and the Congress exactly how the Army's strength had

affected readiness. The Army could not even field four infantry

divisions as a quick response force because of the lack the men to fill

such a force and the bases to accommodate it. Furthermore, if such a

force were concentrated, or even committed, it would be unable to

support training of the reserves. Kilbourne viewed an increase in Army

strength as unlikely but nevertheless recommended as a goal the

maintenance of four peace-strength infantry divisions, one for each

army, and five reinforced infantry brigades.23

The War Department established

an embryonic readiness force on 1 October 1933. Divisional forces

returned to their pre-1927 configuration, with the 1st, 2d, and 3d

Divisions having two active infantry brigades and the 4th through 9th

Divisions having only one active brigade each. In the Fourth Corps Area

the 4th Division also received a third active infantry regiment, another

step closer to the four-division ready force. The next year the field

artillery brigades of the 1st through 4th Divisions were realigned to

consist of one 155mm. howitzer and two 75-mm. gun regiments, and each

active infantry brigade was authorized a 75-mm. gun regiment. All field

artillery units were partially active. No division or brigade was

concentrated on a single post during the reorganization.24

The four-army plan introduced

some realism into the arrangements for mobilizing Regular Army infantry

divisions, but no true emergency force existed because of personnel

shortages. During the next few years the Army revised the preparedness

plans by reassigning divisions and assigning new priorities to them, but

no division could meet an immediate threat.

Even though the status of

divisions between the two world wars fell far short of readiness because

of low manning levels, developments in at least organizational theory

were significant. Divisions designed to fight on a static front and

endure heavy casualties were no longer acceptable. World armies sought

divisions that could defeat an opponent with maneuver and firepower.

Writers such as the Englishmen J. F. C. Fuller and Basil Liddell Hart

led the way, advocating the employment of machines to restore mobility

and maneuverability to the battlefield.

[120]

Motorization, the use of

machines to move men and equipment, had begun early in the twentieth

century and progressively increased thereafter with technological

advances. As a means of movement and transportation behind the front

line in France, infantry divisions used cars, motorcycles, trucks, and

motorized ambulances. Some field artillery regiments also used

caterpillar tractors to move heavier artillery pieces. After World War I

all divisions were authorized some motorized vehicles, but neither

infantry nor cavalry divisions had enough to move all their men and

equipment. Field Service Regulations stipulated that infantry

divisions would depend upon army corps or army units to provide

transportation in the field.25

In 1927 the 34th Infantry, an

element of the 4th Division, conducted experiments using trucks to move

itself, disembark, and fight. Two year later, in 1929, the Army started

a program to motorize eight infantry regiments, four in the Hawaiian

Division and four in the United States assigned to the 4th and 5th

Divisions. To equip each of these small peacetime regiments, the staff

authorized 1 passenger and 4 cross-country cars, 15 motorcycles, and 50

trucks, with most vehicles coming from obsolete World War I stocks. In

1931 Congress appropriated money for the first significant purchase of

trucks since World War I, enabling the Army to motorize the supply

trains of the 1st, 2d, and 3d Divisions. One wagon company in the 2d

Division remained however, because of the reluctance to consign the

horse and wagon to the past.26

By 1934 the Army had developed

motorized equipment for field artillery that equaled the cross-country

mobility of the horse and had sufficient endurance to conduct high-speed

marches. Motorization of the Regular Army's field artillery began when

Congress gave the Public Works Administration money to buy vehicles for

the Army. Within five years all Regular field artillery regiments

assigned to infantry divisions had truck-drawn pieces.27

Besides providing mobility on

the battlefield, trucks helped the Army save money between World Wars I

and II. In 1932 a crisis developed in the National Guard infantry

divisions because they lacked a sufficient number of horses to train the

field artillery. After extensive evaluation, the Guard determined that

trucks were more economical than horses, and the following year it began

to motorize the 75-mm. guns. By the end of 1939 all Guard divisions had

truck-drawn field artillery, except for one regiment in the 44th

Division.28

Mechanization involved employing

machines on the battlefield as distinct from transporting personnel and

equipment. During World War I the British and French had developed tanks

to aid the infantry in the assault, and, using borrowed equipment, the

AEF had organized tank brigades before the end of the war. In combat,

however, tanks fought in small units, usually platoons, in infantry

support roles. Their slow speed and lack of electronic communications

capability made any other tactical employment impractical. After the war

the tank company replaced the motorized machine gun battalion in the

American infantry division. Postwar Army doctrine for tanks still

prescribed that they support infantry in

[121]

close combat to provide

"cover invulnerable to the ordinary effects of rifle and machine

gun fire, shrapnel, and shell splinters." 29

Although the British

and French Armies adopted similar doctrine, continuous improvements in

engines, suspension, and radios steadily increased the capabilities of

such machines. In 1926 the British, responding to the prodding of

Fuller, Liddell Hart, and others, tested an independent mechanized force

that could make swift, deep penetrations in an enemy's rear,

disorganizing and defeating an opponent before effective resistance

could be mounted.30

The following year Secretary of

War Davis observed a mechanized demonstration at Aldershot, England, and

upon returning home ordered development of a similar force. On 30

December 1927, he approved an experimental brigade consisting of two

light tank battalions, a medium tank platoon, an infantry battalion, an

armored car troop, a field artillery battalion, an ammunition train,

chemical and ordnance maintenance platoons, and a provisional motor

repair section, all existing units. In July 1928 units of what was

called the Experimental Mechanized Force assembled at Fort George G.

Meade, Maryland, under the command of Col. Oliver Estridge. For the next

three months the force, more motorized than mechanized, conducted field

tests. Automobile manufacturers contributed trucks and cars, but the few

available pieces of mechanized equipment were obsolete.31

Shortly after Davis approved the

organization of the Experimental Mechanized Force, Maj. Gen. Frank

Parker, Assistant Chief of Staff, G-3.32

adopted another approach toward

mechanization. He concluded that the mechanized experiment would lead

nowhere because the force "would lack the fixity of tactical

purpose and permanency of personnel on which to base experimental work,

and its equipment will be so obsolete as to render its employment very

dissimilar to that of a modernly-equipped mechanized force," 33

Parker

recommended that Summerall appoint a board to prepare tables of

organization and equipment for a mechanized force, establish the

characteristics of its vehicles, and develop doctrine. Summerall, with

Davis' concurrence. established the Mechanized Force Board on 15 May

1928. 34

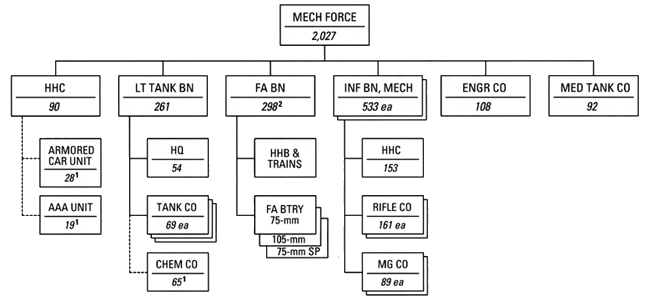

Within six months the board

designed a combined arms armored force of approximately 2,000 officers

and enlisted men. It consisted of a headquarters and headquarters

company, a light tank battalion with an attached chemical company, a

field artillery battalion, an engineer company, and two infantry

battalions each consisting of two rifle and two machine gun companies

(Chart a). A medium tank company, an armored car troop, and a

.50-caliber antiaircraft artillery detachment were to be attached to the

force. Probable missions embraced spearheading an attack, serving as a

counteroffensive force, penetrating enemy defenses, temporarily holding

a key position, and operating in the enemy's rear area to disorganize

his reserves. To carry out these missions, the officers drew up a

"shopping list" for light and medium tanks, armored

reconnaissance cars, semiautomatic rifles, rapid cross-country vehicles

for infantry,

[122]

Medium armored car of the

Mechanized Force

self-propelled 37-mm. antitank

guns, self-propelled 75-mm. and 105-mm. howitzers, and two-way radios.

The report recommended that the force begin as a small unit and build

gradually to full strength. Since new mechanized equipment would not

become available before fiscal year 1930, the board saw no need to

assemble the unit until then. Davis endorsed the plan in November 1928.35

Two years later, just before

Summerall left office, Col. Daniel Van Voorhis organized the first

increment of the unit, which was designated the Mechanized Force, at

Camp Eustis, Virginia. Consisting of a tank company, an armored car

troop, a field artillery battery, and an engineer company, it totaled

roughly 600 men. There, however, the project stopped. Because of the

Great Depression, Congress never appropriated money for more new

equipment, and Van Voorhis' force had to make do with World War

I-vintage equipment along with horses and wagons. Of more concern, the

infantry, cavalry, and other arms and services opposed the use of scarce

Army funds to finance the new organization. With limited amounts of new

wine available, customers wanted their old bottles filled first.36

In May 1931 the new Chief of

Staff, General Douglas MacArthur, changed the direction of

mechanization. He observed that recent experimental units had been based

on equipment rather than on mission and that an item of equipment was

not limited to one arm or service. He therefore instructed all arms or

services to develop fully their mechanization and motorization

potential. Under MacArthur's concept, cavalry was to continue work with

combat vehicles to enhance its role in such areas as reconnaissance,

flank action, and pursuit, while infantry was to explore ways to

increase its striking power by using tanks. His decision spelled the end

of the separate Mechanized Force, and five months later it was

disbanded. Units and men assigned to the force were returned to their

former assignments, except for about 175 officers and enlisted men.

including Van Voorhis, who remained with mechanized cavalry. They

transferred to Camp Henry Knox (later Fort Knox), Kentucky, to create a

new armored cavalry unit.37

On 1 March 1932, Van Voorhis

organized the 7th Cavalry Brigade to experiment with mechanization. At

that time it consisted of only a headquarters, but the following January

the 1st Cavalry moved from Marfa, Texas, to Fort Knox where it

[123]

The Mechanized Force, 1928

1 Attached Units.

2 Internal Strengths not provided.

[124]

became part of the brigade.

Shortly thereafter the regiment adopted tentative tables of organization

that provided for a covering squadron, a combat car squadron, a machine

gun troop, and a headquarters troop. Each squadron had two troops, and

the regiment had a total of seventy-eight combat cars. That structure

lasted until 1 January 1936, when the War Department outlined a new

organization that consisted of a headquarters and band, two combat car

squadrons of two troops each, and headquarters, service, machine gun,

and armored car troops. The new tables authorized the regiment to have

seventy-seven combat vehicles, all developmental items. Eventually the

War Department assigned a second cavalry regiment, a field artillery

battalion equipped with 75-mm. guns (mounted on self-propelled half

tracks), ordnance and quartermaster companies, and an observation

squadron to the brigade. The brigade became the Army's first armored

unit of combined arms, contributing much to the development of

mechanized theory in the interwar years. However, bureaucratic

in-fighting often stifled the unit's development.38

Although many European theorists

urged the development of independent armored forces, their armies made

little progress toward the formation of such units. The British

abandoned their experiments in 1927 and did not organize their first

armored divisions until 1939. The French organized light armored

divisions in the 1930s, but put most of their tanks in various infantry

support roles. In the United States the Regular Army fielded two

partially organized tank regiments as a part of the infantry arm between

1929 and 1940.39

Both German and Russian Armies

took a different approach. Neither had employed tanks in World War I,

but both saw their potential. Only after Adolph Hitler abrogated the

military provisions of the Versailles Treaty in 1935, however, did the

German Army develop offensive-oriented armored panzer divisions. But

their interest in mechanization, especially tanks, was evident

throughout the period, as witnessed by the several visits by German

officers to the 7th Cavalry Brigade at Fort Knox in the mid-1930s. The

Russians experimented with tanks from all industrial nations and favored

the use of mass armor in the mid-thirties. On the eve of World War II,

however, the Russians had shifted emphasis to small tank units in

support of an infantry role.40

January 1929 marked the

beginning of a ten-year struggle to reorganize the infantry division.

The Assistant Chief of Staff, G-3, General Parker, reported that

European countries were developing armies that could trigger a war of

greater velocity and intensity than anything previously known. Great

Britain, France, and Germany were engrossed with "machines" to

increase mobility, minimize losses, and prevent stabilization of the

battlefront. The British favored mechanization and the French,

motorization, while the Versailles Treaty limited the Germans to ideas

and dreams. Some Europeans adopted smaller, more maneuverable,

triangular infantry divisions that were easier to command and control

than the

[125]

unwieldy square division. Since

the Army planned to introduce semiautomatic rifles and light air-cooled

machine guns, Parker suggested that the 2d Division conduct tests to

determine the most effective combination of automatic rifles and machine

guns. Summerall agreed to the proposal but extended the study to

encompass the total infantry division. The study was to concentrate on

approved standard infantry weapons, animal-drawn combat trains, and

motorized field trains. The chief of staff placed no limit on road

space, a principal determinant of divisional organization before and

immediately after World War I.41

The Chief of Infantry, Maj. Gen.

Robert H. Allen, who had responsibility for organizing and training

infantry troops, agreed to the examination but objected to having the

commander of the 2d Division supervise the tests, which he believed fell

within the purview of his own office. Eventually Summerall agreed, and

Allen assigned the job to the Infantry Board at Fort Benning, Georgia.42

During the investigation several

proposals surfaced for a triangular infantry division, which promised

greater maneuverability, better command and control, and simplified

communications and supply. Nevertheless, Army leaders turned down the

idea. Maj. Bradford G. Chynoweth of the Infantry Board attributed the

retention of the square division, which was imminently suitable for

frontal attacks, to Summerall. As a former division and army corps

commander in France, Summerall saw no need for change.43

The question of the infantry

division's organization lay dormant until October 1935, when Maj. Gen.

John B. Hughes, Assistant Chief of Staff, G-3, revived it. In a

memorandum for General Malin Craig, MacArthur's successor as Chief of

Staff, Hughes suggested that the General Staff consider modernization of

the Army's combat organizations. Although great strides had been made in

weapons, equipment, transportation, and communications, organizations

were still based on World War I experiences. He also noted that such

organizational initiatives were the purview of the General Staff, an

obvious reference to the resistance of the chief of infantry in 1929 to

reexamine divisional organizations. Since the General Staff was

responsible for total Army organization, Hughes thought it should

conduct any such examination.44

In November Craig canvassed

senior commanders regarding reorganization issues. He noted the infantry

division in particular had foot, animal, and motor units, all with

varying rates of speed, which did not meet the demands of modern

warfare. Craig wondered if the division were too large, and, if so,

whether or not could it be reduced in size. Possibilities for reduction

included moving support and service functions to army corps or army

level, cutting infantry to three regiments, and reorganizing the field

artillery into a three-battalion regiment. No consensus emerged. Even

the three champions of infantry the Infantry School, the Infantry Board,

and the chief of infantry-failed to agree on a suitable organization,

differing especially on the continued existence of infantry and field

artillery brigades as intermediate headquarters between the regiment and

the division.45

[126]

General Craig

On 16 January 1936 Craig created

a new body, the Modernization Board, to examine the organization of the

Army. Under the supervision of Hughes, the board was to explore such

areas as firepower, supply, motorization, mechanization, housing,

personnel authorization, and mobilization. It was to consider

recommendations from the field, the General Staff, service schools, and

any earlier studies, including those concerned with foreign armies.

Despite this broad charter, the board members nevertheless addressed

only the infantry division, considering the total Army organization too

extensive and too complex to be covered in one study. Besides, the board

concluded that the formation of higher commands rested upon the

structure of the infantry division.46

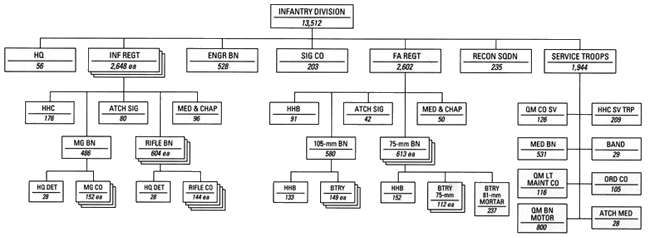

The board's report, submitted on

30 July 1936, rejected the square infantry division and endorsed a

smaller triangular division (Chart 9), which could easily he organized

into three "combat teams." Its proposal cut the infantry

division from 22,000 officers and enlisted men to 13,500 and simplified

the command structure. The brigade echelon for infantry and field

artillery was eliminated, enabling the division commander to deal

directly with the regiments. The enduring problem of where to locate the

machine gun was dealt with again; one machine gun battalion was included

in the infantry regiment, which also had three rifle battalions. The

field artillery regiment consisted of one 105-mm. howitzer battalion and

three mixed battalions of 75-mm. howitzers and 81-mm. mortars. The

latter were to be attached to the infantry regiments in combat. To

assist in moving, searching, and operating quickly on a broad front,

cavalry returned to the division for the first time since before World

War I in the form of a reconnaissance squadron, to be equipped with

inexpensive unarmored or lightly armored cross-country vehicles. The

anticipated rapid movement of the division minimized the need for

extensive engineer work, except on roads. Therefore, an engineer

battalion replaced the existing regiment. Because engineers would be

primarily concerned with road conditions, they were also to provide

traffic control in the divisional area. A signal company was to maintain

communications between the division and regimental headquarters, and

attached signal detachments were to perform these services within

regiments.47

To increase mobility, the

division's combat service support elements underwent radical changes. A

battalion of trucks and a quartermaster service company of

[127]

Proposed Infantry Division, 30 July 1936

[128]

laborers formed the heart of a

new supply system. They handled the baggage and noncombat equipment of

all divisional elements. Each divisional unit was responsible for its

own ammunition resupply. The new arrangement led to the elimination of

the ammunition train, regimental field trains, and the quartermaster

regiment. A quartermaster light maintenance company was added to service

the motor equipment. The maintenance of hospitals passed to the army

corps. A newly organized medical battalion collected and evacuated

casualties, while infantry, field artillery, cavalry, and engineer units

kept their medical detachments to provide immediate aid. A11 service

elements were placed under a division service troops command, headed by

a general officer, with a headquarters company that performed the

provost marshal's duties and included the division's special staff.48

To comply with Craig's directive

for the division to employ the latest weapons, the board recommended

that its infantrymen be armed with the new semiautomatic Garand rifle,

which the War Department had approved in January. For field artillery,

the board wanted the even newer 105-mm. howitzer, which was not yet even

in the Army's inventory.49

Members of the board concluded

that they had given the division all the combat and service support

resources needed for open warfare. Those elements not required were

moved up to the army corps or army echelon. Additional units, such as

heavier field artillery, antimechanized (antitank), tank, antiaircraft,

aviation, motor transport, engineer, and medical units, might be

required, but the board made the divisional staff large enough to

coordinate the attachment of such troops. Although small, the new

division was thought to have equal or greater firepower than the square

division and occupied the same frontages as its predecessor.50

In a separate letter to Craig,

Hughes summarized the advantages and disadvantages of the new infantry

division. Pluses included its highly mobile nature, the ease with which

infantry and field artillery could form combat teams, and the reduction

in the number of command echelons and amount of administrative overhead.

He also pointed to improvements in transportation, supply, and

maintenance, since all animal transport was eliminated. Given such a

division, he believed that the Regular Army could achieve a viable

readiness force without an increase in authorized personnel. Drawbacks

appeared minor. The states might not accept a reallotment of National

Guard infantry divisions in peacetime. As a federal force, those

divisions served only in national emergency or war, but as state forces

they had been located and frequently used to cope with local emergencies

and disasters. Hughes questioned splitting communication functions

between the arms and the signal company and the pooling of

transportation for baggage and other noncombat equipment into the

service echelon. Both arrangements could generate friction because the

functions would be outside the control of the user. He was also

concerned about the loss of the infantry and field artillery brigades

because they eliminated general officer positions. Finally, training

literature would need revision and dissemination to the field.51

[129]

After reviewing the report,

Craig decided to test the proposed division with attached antimechanized

(antitank) and antiaircraft artillery battalions and an observation

squadron. He selected the 2d Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. James K.

Parson, to conduct the test between September and November 1937. The

resulting Provisional Infantry Division (PID) included 6,000 men from

the 2d Division and a similar number from other commands, which also

furnished much of the equipment. The examination, the first in the

history of the Army, was held in Texas, where space and terrain

permitted a thorough analysis of the unit.52

Even before the test ended, Maj.

Gen. George A. Lynch, Chief of Infantry, vetoed the proposed

organization in a report to the staff in Washington. Having witnessed

part of the exercise, he viewed the separation of the machine gun from

the rifle battalion and the attachment of the signal detachment and

mortar battery to the infantry regiment as mistakes. The first prevented

teamwork in the regiment, and the second interfered with unity of

command. Lynch considered the attached antitank battalion an infantry

unit because it used the same antitank weapons as the infantry regiment.

He objected to the commander of the service troops, contending that the

presence of a general officer in this position complicated the chain of

command. Furthermore, since the movement of the trains depended on the

tactical situation, only the division commander could make the decision

to move them. Because field, supply, and ammunition trains operated to

the rear of the combat units, Lynch discerned no need for them in the

division. He suggested that the Army return to the fixed army corps, in

which divisions did the fighting and the corps provided the logistical

support.53

Shortly after Lynch's negative

account, the New York Times reported that Craig planned to

appoint a special committee to design an infantry division based on the

PID test. The article claimed that the committee was to include Maj.

Gen. Fox Conner, Col. George C. Marshall, and a third unnamed officer.

Eventually Brig. Gen. Lesley J. McNair, the Chief of Staff of the RID,

was identified in private correspondence as the third member. Conner and

Marshall, former members of the Lassiter Board, had supported Pershing's

small division. Conner had also served as Craig's personnel

representative at the PID test. Within a few days Marshall, writing from

Vancouver Barracks, Washington, told a friend that such a board would

look like a "stacked deck" to secure a small division. As it

happened, any plans for the group fell through when Conner retired for

medical reasons.54

The final report on the PID

test, mostly the work of McNair, noted many of the divisional weaknesses

identified by Lynch, but, instead of assigning the division to a fixed

army corps, McNair proposed a new smaller and more powerful division. To

attain it, he recommended that the infantry regiment have an antitank

company and three battalions, each with one machine gun and three rifle

companies. The machine gun company was to be armed with both machine

guns and mortars. Inclusion of the antitank company in the regiment

eliminated the need to attach such a battalion to the division. Like

Lynch, he suggested eliminating signal detachments in favor of infantry,

artillery, and cavalry troops. To increase

[130]

firepower and range, McNair

wanted to replace 75-mm. howitzers with 75-mm. guns and one battalion of

105-mm. howitzers with 155-mm. howitzers. He felt that mortars had no

place in the division artillery because they could not provide close

support for infantry and their rate of fire, range, and accuracy failed

to meet field artillery standards. Another battery of 75-mm. guns in

each direct support battalion was to replace the mortars. Because the

reconnaissance squadron operated considerably in front of the division

and on its flanks, he proposed that it be moved to the corps level.

McNair sensed an overabundance of engineers. In a war of movement,

engineers would not have the time to do extensive road work. Another

responsibility, that of traffic control, could return to the military

police. Therefore, the engineer battalion could be reduced to a company

and a separate military police unit would combine provost marshal and

traffic control missions. McNair also faulted the special command for

the service troops organization and advised its elimination. He believed

the ordnance company and band were unnecessary and advocated their

reassignment to higher echelons. The quartermaster service company and

motor battalion were to be combined as a quartermaster battalion, which

was to supply the division with everything except ammunition. Each

combat element was to remain responsible for its own ammunition supply.

These changes produced a division of 10,275 officers and enlisted men.55

After analyzing all reports and

comments, the Modernization Board redesigned the division, retaining

three combat teams built around the infantry regiments. Each regiment

consisted of a headquarters and band, a service company, and three

battalions, each with one heavy weapons company armed with 81-mm.

mortars and .30and .50-caliber machine guns and three rifle companies,

but no antitank unit. The .50-caliber machine guns in the heavy weapons

companies and the 37-mm. guns in the regimental headquarters companies

were to serve primarily as antitank weapons. The large four-battalion

artillery regiment was broken up into two smaller regiments, one of

three 75-mm. gun battalions and the other with a battalion of 105-mm.

howitzers and a battalion of 155-mm. howitzers. Although the test had

shown that the field artillery commander had no problems with the

four-battalion unit, school commandants and corps area commanders

questioned the quality of command and control within the regiment. Two

general officers assisted the commander, one for infantry and one for

field artillery, but they were not in the chain of command for passing

or rewriting orders. Within the combat arms regiments, signal functions

fell under the regimental commanders, while the divisional signal

company operated the communication system to the regiments. The engineer

battalion was retained but was reduced in size and consisted of three

line companies in addition to the battalion headquarters and

headquarters company. Traffic control duties moved to a new military

police company that combined those activities with the provost marshal's

office.56

The board completely reorganized

the supply system. The combat arms were given responsibility for their

own ammunition resupply and baggage. Therefore, the motor battalion was

eliminated. A new quartermaster battalion was established.

[131]

which included a truck company

to transport personnel and rations, a service company to furnish

laborers, and a headquarters and headquarters company. The headquarters

company could do minor motor maintenance requiring less than three

hours, while major motor maintenance moved to the army corps level. The

quartermaster light maintenance and ordnance companies were removed from

the division. Medical service within the division was based on the

assumption that it would be responsible for the collection and

evacuation of the sick and wounded to field hospitals established by

corps or higher echelons. The former headquarters company, service

troops, was incorporated into the division headquarters company.57

With no change expected in total

Army strength, the new division had two authorized strengths, a wartime

one of 11,485 officers and enlisted men and a peacetime one of 7,970.

During peacetime all elements of the division were to be filled except

for the division headquarters and military police companies, which were

to be combined. Other divisional elements required only enlisted

personnel to bring them up to wartime manning levels.58

After the Modernization Board

redesigned the division, Craig decided to spend a year evaluating it

before he determined its fate. The 2d Division, selected once more for

the task, again borrowed personnel and equipment from other units to

fill its ranks. Between February 1939 and Germany's invasion of Poland

on 1 September, the "Provisional 2d Division" commanded by

Maj.

Gen. Walter Krueger tested the proposed unit. Krueger found the

organization sound except for the quartermaster battalion and the need

to make some minor adjustments in a few other elements. The

quartermaster battalion lacked enough laborers and trucks to supply the

division, and he recommended increases in both. With its many pieces of

motorized equipment, the division required more maintenance personnel.

Minor changes included augmentations to the divisional intelligence

(G-2) and operations (G-3) staff sections, a slight increase in the

signal company to handle communications for the second field artillery

regiment, a complete motorization of the engineer battalion, and the

replacement of the five regimental bands with one divisional band.59

Maj. Gen. Herbert J. Brew,

Eighth Corps Area commander and the test director, concurred with most

of Krueger's findings except for the engineer and quartermaster

battalions. He opposed completely motorizing the engineer unit because

the engineers were to be limited to the divisional area instead of a

broad front. He favored an increase in the number of trucks in the

quartermaster battalion but not to the extent suggested by Krueger. Brew

also saw no need for infantry and artillery sections having their own

general officers, because the commander could easily deal with all

elements, but he recommended a staff officer, not necessarily a general

officer, to coordinate field artillery fire. To make room for a second

general officer in the division, he suggested that the division's chief

of staff become the second-in-command with the rank of brigadier general

because he would know more about the division than anyone else except

for the commander.60

[132]

General Marshall

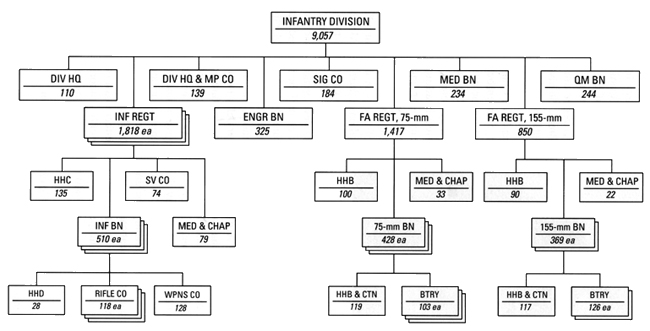

On 14 September 1939, Lt. Col.

Harry Ingles of the Modernization Board summarized the evolution of the

division's organization, focusing on the report of Krueger and the

comments of Brew. He also recommended resolutions to the disputed

points. Two days later Marshall, who had replaced Craig as Chief of

Staff on 1 September, approved a new peacetime division, which included

infantry and artillery sections headed by general officers in the

division headquarters, a motorized engineer battalion, a divisional band

within the headquarters company, and an increase in the number of trucks

in the quartermaster battalion (Chart 10). Marshall's division was

completely motorized.61

Still, the new organization did

not totally satisfy Marshall. Having followed its development closely as

chief of the War Plans Division and later as deputy chief of staff, he

believed that the division should be even stronger to cope with

sustained combat. In Marshall's view, however, the new organization's

overwhelming advantage was that the National Guard divisions could

easily adopt it. Furthermore, the onset of war in Europe added urgency

because the Army could no longer delay modernization.62

A few days after Marshall

approved the new structure he authorized the reorganization of the 1st,

2d, and 3d Divisions and the activation of the 5th and 6th Divisions,

each with a strength of 7,800 officers and enlisted men. No division was

concentrated because the Army did not have a post large enough to house

one. Divisional elements, however, were conveniently located within

corps areas to ease training. Geographically, the divisions were

distributed so that one division was on each of the seaboards (Atlantic

and Pacific), one near the southwest frontier, and two centrally located

to move to either coast or the southwest. With the outbreak of war in

Europe, Congress quickly authorized increases in the strength of the

Army, and by early 1940 the infantry division stood at 9,057.63

The Modernization Board took up

the cavalry division in 1936. Most officers still envisioned a role for

the horse because it could go places inaccessible to

[133]

Infantry Division (Peace), 1939 Corrected to 8 January 1940

CTN = Combat Train

WPNS = Weapons

SV = Service

[134]

1st Cavalry Division maneuvers, Toyahvale, Texas, 1938

motorized and mechanized

equipment. Taking into account recommendations from the Eighth Corps

Area, the Army War College, and the Command and General Staff School,

the board developed a new smaller triangular cavalry division (Chart

11),

which the 1st Cavalry Division evaluated during maneuvers at Toyahvale,

Texas, in 1938. Like the 1937 infantry division test, the maneuvers

concentrated on the divisional cavalry regiments around which all other

units were to be organized.64

Following the test, a board of

1st Cavalry Division officers, headed by Brig. Gen. Kenyon A. Joyce,

rejected the three-regiment division and recommended retention of the

two-brigade (four-regiment) organization. The latter configuration

allowed the division to deploy easily in two columns, which was accepted

standard cavalry tactics. However, the board advocated reorganizing the

cavalry regiment along triangular lines, which would give it a

headquarters and headquarters troop, a machine gun squadron with special

weapons and machine gun troops, and three rifle squadrons, each with one

machine gun and three rifle troops. No significant change was made in

the field artillery, but the test showed that the engineer element

should remain a squadron to provide the divisional elements greater

mobility on the battlefield and that the special troops idea should

[135]

Cavalry Division, 1938

1 Strengths not available

[136]

be extended to include the

division headquarters, signal, and ordnance troops; quartermaster,

medical, engineer, reconnaissance, and observation squadrons; and a

chemical warfare detachment. One headquarters would assume

responsibility for the administration and disciplinary control for these

forces.65

Although the study did not lead

to a general reorganization of the cavalry division, the wartime cavalry

regiment was restructured, effective 1 December 1938, to consist of a

headquarters and headquarters troop, machine gun and special weapons

troops, and three squadrons of three rifle troops each. The special

troops remained as structured in 1928, and no observation squadron or

chemical detachment found a place in the division. With the paper

changes in the cavalry divisions and other minor adjustments, the

strength of a wartime divisional rose to 10,680.66

Such paper changes characterized

much of the interwar Army's work. Although planners lacked the resources

to man, equip, and test functional divisions, they gave considerable

thought to their organization. They developed a new concept for the

infantry division, experimented with a larger cavalry division, and

explored the organization of a mechanized unit. Designing the new

infantry division with a projected battlefield in North America,

officers took into account the span of control, the number of required

command echelons, the staff, the balance between infantry and field

artillery, the location of the reconnaissance element, the role of

engineers, and the best way to organize the services and supply system.

The triangular infantry division appeared to offer the best solution to

these requirements according to the planners, who Marshall thought were

among "the best in the Army."67

[137]

Endnotes

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

page created 29 June 2001

Return to the

Table of Contents

-