Chapter IV:

The Aftermath of World War I

that the work of this Board

was undertaken so soon after the close of hostilities that the members

were unduly influenced by the special .situation which existed during

our participation in the World War.

General John J. Pershing 1

The abrupt end of World War I

and the immediate demand for demobilization threw the Army into

disarray, but out of the disorder eventually came a new military

establishment. Between the armistice in November 1918 and the summer of

1923 the Army occupied a portion of Germany, demobilized its World War I

forces, helped revise the laws regulating its size and structure, and

devised a mobilization plan to meet future emergencies. Amid the turmoil

Army officers analyzed and debated their war experience, arguing the

merits of a large, powerful infantry division designed to penetrate an

enemy position with a frontal assault versus a lighter, more mobile unit

that could outmaneuver an opponent. The cavalry division received a

similar but less extensive examination. After close scrutiny, the Army

adopted new infantry and cavalry divisions and reorganized its forces to

meet postwar conditions.

Hostilities ended on 11 November

1918, but the Army still had many tasks to perform, including the

occupation of the Coblenz bridgehead on the Rhine River. For that

purpose, Maj. Gen. Joseph T. Dickman, at the direction of General

Pershing, organized the Third Army on 15 November. Ten U.S. divisions

eventually served with it-the 1st through 5th, 32d, 42d, 89th, and 90th

in Germany and the 33d in Luxembourg-as well as the French 2d Cavalry

Division. Also elements of the 6th Division began moving toward the

bridgehead in later April 1919, but that movement was halted in early

May. Divisional missions included the administration of civil

government, the maintenance of public order, and the prevention of

renewed aggression.2

The divisional structure proved

unsatisfactory for the military government role. Its organization could

not mesh with the civil government of Germany, and the Third Army lacked

the time and expertise needed to mature a uniform civil affairs program.

Furthermore, assigned areas for the divisional units shift-

[79]

American Troops cross the Rhine at Coblenz, Germany, January 1919.

ed rapidly as divisions departed

the bridgehead for the United States. Yet, under the terms of

occupation, the entire bridgehead had to remain under American

supervision. By the summer of 1919 American divisions had left for home,

and the military government functions moved from the tactical units to

an area command, the Office of Civil Affairs. With the departure of the

divisions, only brigade-size or smaller units remained in Germany, and

they too departed by January 1923.3

As the Third Army grappled with

occupation duty, officials in Washington confronted the problem of

demobilizing the wartime army. On 11 November 1918 a quarter of a

million draftees had been under orders to report for military duty. With

the signing of the armistice the War Department immediately halted the

mobilization process, but it had no plans for the Army's transition to a

peacetime role.4

One man, Col. Casper H. Conrad

of the War Plans Division, had begun to study demobilization, and he

submitted his report eleven days after the armistice. From Conrad's

several proposals on disbanding the forces, Chief of Staff March decided

to discharge soldiers by units rather than by individuals. Because

National Guard and National Army divisions originally had geographical

ties, he also ruled that units returning from overseas would be

demobilized at the centers nearest to where their men had entered the

services. 5

Demobilization began in November

1918. March first disbanded the partially organized divisions in the

United States, making their camps available as dis-

[80]

1st Field Artillery Brigade, 1st Division, on occupation duty

in Germany, August 1919

charge centers. In January 1919

Pershing sent home the divisions that had been skeletonized or had

performed replacement functions. Combat divisions followed, beginning

with the 92d, the Army's only black division. A year after the armistice

the Army had demobilized fifty-five of its sixty-two divisions,

including all the National Guard and National Army units (Table 7). Before

the units left service, the War Department gave the American people the

opportunity to show their appreciation to the men who had fought in the

war. Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington held

divisional parades and over five hundred regiments marched through the

streets of their hometowns.6

After November 1919 only the 1st

through the 7th Divisions and a few smaller units remained active.

All were Regular Army units. These divisions retained their wartime

configurations, but personnel authorizations for fiscal year 1920

prevented full manning. Divisional regiments had the strengths

prescribed in the prewar tables of organization issued on 3 May 1917,

and the ammunition, supply, and sanitary trains had only enough men to

care for their equipment. Within only a year, the mighty combat force

the Army had struggled to build during 1917-18 had vanished without any

plans to replace it.7

The helter-skelter pace of demobilization and the

lack of any sound transitional planning greatly undermined efforts to

create an effective peacetime force. A student of demobilization,

Frederic L. Paxon, characterized this situation as worse than a

"madhouse in which the crazy might be incarcerated. They were at

large." 8

[81]

Demobilization of Divisions

| Division |

Returned to U.S. |

Demobilized |

Camp/Location |

| 1st |

September 1919 |

|

Zachary Taylor,

Ky |

| 2d |

August 1919 |

|

Travis, Tex. |

| 3d |

August 1919 |

|

Pike, Ark. |

| 4th |

August 1919 |

|

Dodge, Iowa |

| 5th |

July 1919 |

|

Cordon, Ga. |

| 6th |

June 1919 |

|

Grant,

Ill. |

| 7th |

June 1919 |

|

Funston, Kans. |

| 8th* |

September 1919 |

|

September 1919

Dix, N.J. |

| 9th |

# |

February 1919 |

Sheridan, Ala. |

| 10th |

# |

February 1919 |

Funston,

Kans. |

| 11th |

# |

February 1919 |

Meade, Md. |

| 12th |

# |

February 1919 |

Devens, Mass. |

| 13th |

# |

March 1919 |

Lewis, Wash. |

| 14th |

# |

February 1919 |

Ouster, Mich. |

| 15th |

# |

February 1919 |

Logan, Tex. |

| 16th |

# |

March 1919 |

Kearny, Calif |

| 17th |

# |

February 1919 |

Beauregard,

La. |

| 18th |

# |

February 1919 |

Travis, Tex. |

| 19th |

# |

February 1919 |

Dodge, Iowa |

| 20th |

# |

February 1919 |

Sevier, S.C. |

| 26th |

April 1919 |

May 1919 |

Devens, Mass. |

| 27th |

March 1919 |

April 1919 |

Upton, N.Y. |

| 28th |

April 1919 |

May 1919 |

Dix, N.J. |

| 29th |

May 1919 |

May 1919 |

Dix, N.J. |

| 30th |

April 1919 |

May 1919 |

Jackson, S.C. |

| 31st |

December 1918 |

January 1919 |

Cordon, Ga. |

| 32d |

May 1919 |

May 1919 |

Ouster,

Mich. |

| 33d |

May 1919 |

June 1919 |

Grant, Ill. |

| 34th |

January 1919 |

February 1919 |

Grant, Ill. |

| 35th |

April 1919 |

May 1919 |

Funston,

Kans. |

| 36th |

June 1919 |

June 1919 |

Bowie,

Tex. |

| 37th |

April 1919 |

June 1919 |

Sherman,

Ohio |

| 38th |

December 1918 |

January 1919 |

Zachary Taylor, Ky |

| 39th |

December 1918 |

January 1919 |

Beauregard, La. |

| 40th |

March 1919 |

April 1919 |

Kearny,

Calif. |

| 41st |

February 1919 |

February 1919 |

Dix, N.J. |

| 42d |

May 1919 |

May 1919 |

Dix, N.J. |

| 76th |

December 1918 |

January 1919 |

Devens, Mass. |

| 77th |

April 1919 |

May 1919 |

Upton,

N.Y. |

| 78th |

June 1919 |

June 1919 |

Dix, N.J. |

| 79th |

May 1919 |

June 1919 |

Dix, N.J. |

| 80th |

May 1919 |

June 1919 |

Lee, Va. |

| 81st |

June 1919 |

June 1919 |

Hoboken,

N.J. |

| 82d |

May 1919 |

May 1919 |

Upton, N.Y. |

| 83d |

January 1919 |

October 1919 |

Sherman, Ohio |

| 84th |

January 1919 |

July 1919 |

Zachary Taylor, Ky |

| 85th |

March 1919 |

April 1919 |

Ouster,

Mich. |

| 86th |

January 1919 |

January 1919 |

Grant, Ill. |

| 87th |

January 1919 |

February 1919 |

Dix, N.J. |

| 88th |

June 1919 |

June 1919 |

Dodge,

Iowa |

[82]

TABLE 7-Continued

| Division |

Returned to U.S. |

Demobilized |

Camp/Location |

| 89th |

May 1919 |

July 1919 |

Funston, Kans |

| 90th |

June 1919 |

June 1919 |

Bowie,

Tex. |

| 91st |

April 1919 |

May 1919 |

Presidio

of San Francisco, Calif. |

| 92d |

February 1919 |

February 1919 |

Meade,

Md. |

| 93d@ |

|

|

| 95th |

# |

December 1919 |

Sherman, Ohio |

| 96th |

# |

January 1919 |

Wadsworth, N.Y.

|

| 97th |

# |

December 1918 |

Cody, N.Mex. |

| 98th |

# |

November 1918 |

McClellan,

Ala. |

| 99th |

# |

November 1918 |

Wheeler, Ga. |

| 100th |

# |

November 1918 |

Bowie, Tex. |

| 101st |

# |

November 1918 |

Shelby,

Miss. |

| 102d |

# |

November 1918 |

Dix, N.J. |

Notes:

* Only part of the division

overseas.

# Did not go overseas.

@ Provisional division,

headquarters demobilized in France in May 1918.

[83]

Although rapid demobilization

destroyed the Army's combat effectiveness, military and congressional

leaders wanted to avoid what they considered the major mistake made

after every earlier war-the loss of well-trained, experienced, combat

soldiers. Notwithstanding that World War I was to have been "the

war to end all wars," perceived international realities required

that the nation be prepared for war. Both Congress and the War

Department had been considering changes in the National Defense Act, and

Brig. Gen. Lytle Brown, Chief of the War Plans Division, suggested that

March obtain the AEF's views on the new Army establishment. He suspected

that division, corps, and army organizations used in the "Great

War" might not meet future battlefield requirements because they

were tied so closely to trench warfare, a type of warfare he thought

unlikely to recur.9

Under War Department orders,

Pershing set up boards in France to examine the AEF experiences with the

arms and services and to draw appropriate lessons for the future. At his

staff's suggestion, he also convened the Superior Board to review the

other boards' findings. In April Pershing relieved Dickman as the

commander of Third Army and appointed him and other senior officers to

the review board. All its members had close professional ties to

Pershing and had witnessed from various positions the

"success" of the heavy infantry division during the war. The

board's primary mission was an examination of that infantry division.

After a two-month investigation, the Superior Board tendered its

recommendation, basically endorsing the World War I square division with

modifications. Changes centered on improvements in combat and service

support, firepower, and command and control. 10

[83]

5th Field Artillery troops at the 1st Division parade, September

1919

Changes in command and control

touched all divisional echelons. The board recommended headquarters

detachments for artillery and infantry brigades along with larger

staffs. Because the ammunition train served primarily with the artillery

brigade, it proposed making the train an organic element of that unit

but serving both artillery and infantry troops. Similarly, the board

members believed that the engineer train should be a part of the

engineer regiment. Following the principle of placing resources under

the control of those who used them, the board wanted to drop the machine

gun battalion from the infantry brigade and place a machine gun company

in each infantry battalion. The board members believed that only when

the infantry commander had his own machine gun company could he learn to

handle it properly. For training in mass machine gun fire, the board

advised that the companies assemble occasionally under a brigade machine

gun officer. It also advocated the retention of a divisional machine gun

officer and a divisional machine gun battalion to provide a reserve for

barrage or mass fire.

The board regarded the rear area

division train headquarters and the accompanying military police as

unnecessary. When needed, the division commander could appoint an

officer to command the rear elements. The military police could become a

separate company. The war had disclosed complex communication problems,

particularly in the use of radios, but no uniform signal organization

existed. To overcome that defect, the board advised that a closer

examination of divisional signal needs be conducted with consideration

given to dividing them along functional lines.

Turning to firepower, the

Superior Board recommended the elimination of ineffective weapons and

the addition or retention of effective ones. Based on wartime

experience, the 6-inch mortar battery in the field artillery brigade was

[84]

deleted and a howitzer company

added to the infantry regiment. The infantry was to continue to use

37-mm. guns and 3-inch Stokes mortars temporarily, but eventually

howitzers were to replace the mortars. The board found that mortars

lacked mobility, accuracy, and range and were difficult to conceal and

supply. The board looked upon tractor-drawn artillery pieces as a

success in combat and felt that retention of motorized artillery was

appropriate if future wars were fought in countries having an extensive

road net like that in France. For flexibility, however, the board

advised that one 75-mm. gun regiment remain horse-drawn and the other be

motor-drawn, along with a motorized 155-mm. howitzer regiment. They

decided that the new weapon, the tank, used during the war to break up

wire entanglements and to reduce machine gun nests, belonged to the

infantry, but instead of assigning tank units to the division, the

officers placed them at army level. Tanks could then be parceled out to

divisions according to need.

The board also addressed the

combat support needs of the division. Since the division routinely

employed aircraft for artillery observation, liaison, registration of

fire, and reconnaissance, the board suggested the addition of an air

squadron, a balloon company, a photographic section, and an intelligence

officer to the division. The board endorsed the addition of a litter

battalion to the sanitary train to improve medical support and the

elimination of all horse-drawn transportation from that unit and from the

rest of the division, except for artillery. Because engineers had often

been used as infantry in combat, some board members proposed reducing

the number of engineer troops. The board concluded, however, that while

engineers often had been employed as infantry, this practice stemmed

from a failure to understand their role. It advised the retention of the

engineer regiment.

Summarizing the requirements for

the future infantry division, the Superior Board recommended that it be

organized to meet varying combat and terrain conditions encountered in

maneuver warfare but have only those elements that it customarily

needed. The army corps or army level would supply infrequently used

organizations. The board's report endorsed a square division that

numbered 29,000 officers and enlisted men-an organization "imbued

with the divisional spirit, sense of comradeship and loyalty, that will

guarantee service . . . in critical moments when the supreme effort must

be made."11

Although Pershing had not

employed a cavalry division in France, the Superior Board also examined

its structure in light of Allied experiences, particularly in Italy and

Palestine. The board concluded that, except for distant reconnaissance

by airplanes, the missions of mounted troops-screening, shock action,

and tactical reconnaissance-remained important on the postwar

battlefield. To conduct such missions, the cavalry division needed to

capitalize on its mobility and firepower. Finding the 1917 unit of

18,000 men too large, the board entertained two proposals for

reorganizing it. One called for a division of three cavalry regiments,

an artillery regiment, and appropriate combat and service support units;

the other comprised two cavalry brigades, each with two cavalry

regiments,

[85]

Superior Board Members. Left to right, Maj. Gens. Joseph T.

Dickman, John L. Hines, and William Lassiter, Col. George R Spalding,

Brig. Gen. William Burtt, and Col. Parker Hitt.

and a machine gun squadron, an

artillery regiment, and auxiliary units. The board rejected the

three-regiment unit because it eliminated a general officer billet,

recommending instead a square cavalry division of some 13,500 men.

The Superior Board completed its

work on 1 July 1919, but Pershing held the report to consider its

findings. He did not

forward it to the War Department until almost a year later. 12

Although Pershing temporarily

shelved the Superior Board Report, Congress and the War Department

proceeded to explore postwar Army organization. On 3 August 1919,

Secretary Baker proposed a standing army of approximately 500,000 men

and universal military training for eighteen- and nineteen-year-old

males. With that number the department envisaged maintaining one cavalry

and twenty infantry divisions. March testified that before 1917, when

the Army was stationed at small, scattered posts, officers had no

occasion to command brigades or divisions or gain experience in managing

large troop concentrations. Under the proposed reorganization, officers

would have the opportunity to command large units and to train combined

arms units, thus correcting a major weakness of past mobilizations.13

[86]

After much debate Congress

amended the National Defense Act on 4 June 1920, providing for a new

military establishment but scuttling the unpopular universal military

training proposal. Instead it authorized a Regular Army of 296,000

officers and enlisted men, a National Guard of 435,000 men, and an

Organized Reserve (Officers Reserve Corps and Enlisted Reserve Corps) of

unrestricted size. To improve mobilization the law required that the

Army, as far as practical, be organized into brigades, divisions, and

army corps, with the brigades and divisions perpetuating those that had

served in the war. The new law replaced the old territorial departments

with corps areas, which assumed the tasks of administering and training

the Army. Each corps area was to have at least one National Guard or

Organized Reserve division. Corps areas were to be combined into army

areas for inspection, mobilization, maneuver, and demobilization. Rather

than mandating the structure of regiments as in the past, Congress

authorized the number of officers and enlisted men for each arm and

service and instructed the president to organize the units. To advise on

National Guard and Organized Reserve matters, Congress directed the

formation of committees with members from the Regular Army and both

reserve components.14

On 1 September 1920, the War

Department established the general outline of the postwar Army. It

consisted of three army areas divided into nine corps areas (Map 1).

Each army area supported one Guard and two Reserve cavalry divisions,

and each corps area maintained one Regular, two Guard, and three Reserve

infantry divisions, all to be sustained by combat support and combat

service support units to be perfected later. 15

Six committees of the War Plans

Division developed the postwar Army. Only one, however, the Committee on

Organization, dealt directly with the structure of the division through

the preparation of organizational tables. Until that work was completed,

no realistic calculation of future military requirements could be made.

The other committees defined the roles of the National Guard and the

Organized Reserves, estimated the number of Regular Army personnel

required to train and administer them, established manning requirements

for foreign garrisons, determined the number of regulars needed for an

expeditionary force, and fixed the distribution of the Regular Army in

the United States to meet strategic and training considerations.16

The Committee on Organization

prescribed a 23,000-man square division patterned after the unit of

World War I. Seeking comments from beyond the confines of the General

Staff, Col. William Lassiter of the War Plans Division sent the tables

to the commandants of the Infantry School at Fort Benning, Georgia; the

General Service Schools at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas; and the General

Staff College in Washington, D.C., as well as to General Pershing's AEF

headquarters in Washington.17

Faced with the possibility of

having a decision made without his views being considered, on 16 June

Pershing finally forwarded the Superior Board report along with his

comments about the infantry division, which differed substantially

[87]

[88-89]

from the board's findings, to

Baker. In comments prepared mostly by Col. Fox Conner, Pershing

suggested a 16,875-man division having a single infantry brigade of

three infantry regiments, an artillery regiment, a cavalry squadron, and

combat support and combat service support units, a design that

foreshadowed the triangular division the Army adopted for World War 11. 18

Pershing felt the Superior Board

undertook its work too soon after the close of hostilities and that its

report suffered unduly from the special circumstances on the Western

Front. After examining all organizational features, he concluded that no

one divisional structure was ideal for all battlefield situations.

Factors such as the mobility and flexibility of the division to meet a

variety of tasks, the probable theater of operations, and the road or

rail network available to support the division had to be weighed. The

most likely future theater of war for the Army was still considered to

be North America, and he believed that the infantry divisions employed

in France were too unwieldy and immobile for that region. Therefore, he

recommended a small mobile division. 19

According to Pershing, specific

signposts marked the path to a smaller division, among them putting

infrequently used support units at the army corps or army level,

organizing the divisional staff to handle needed attached units, making

a machine gun company an integral part of the infantry battalion, and

providing horse- or mule-drawn vehicles throughout the division because

of the poor roads in the United States. Summarizing the requirements for

the infantry division, he wrote: "The division should be small

enough to permit its being deployed from . . . a single road in a few

hours and, when moving by rail, to permit all of its elements to be

assembled on a single railroad line within twenty-four hours; this means

that the division must not exceed 20,000 as maximum.."20

On 18 June representatives from

the General Staff and Pershing's headquarters conferred to iron out the

differences between the two positions. The conference failed to reach

agreement. Therefore, at Baker's direction, a special committee met to

solve this organizational issue.21

Like the Superior Board, the

Special Committee, commonly referred to as the Lassiter Committee, drew

upon the talents of former AFT officers. From the General Staff, besides

Colonel Lassiter, came Lt. Col. Brunt H. Wells, Maj. John W Gulick, and

Capt. Arthur W Lane. Majs. Stuart Heintzelman and Campbell King

represented the General Staff College; Maj. Hugh A. Drum, the General

Services Schools; and Col. Charles S. Farnsworth, the Infantry School.

Col. Fox Conner and Capt. George C. Marshall spoke for Pershing. Except

for Farnsworth, who had commanded the 37th Division during combat, all

had held army corps, army, and General Headquarters staff positions

where they had gained firsthand knowledge about the operation of

divisions and higher commands in France. In addition, Wells had helped

draft the initial proposal for the square division adopted during the

war; Conner had been a French interpreter for the General Staff in 1917

when the proposal was prepared; and Heintzelman had edited General

Pershing's report of operations in France.22

[90]

Meeting between 22 June and 8

July 1920, the committee examined three questions: Was the World War I

division too large? If so, should the Army adopt a smaller division

comprising three infantry regiments? Finally, if a division of four

infantry regiments were retained, could it be reduced to fewer than

20,000 men, a figure acceptable to Pershing?23

The committee reviewed all

previous divisional studies and recommendations; acquainted itself with

views held by officers of the General Staff, departments, and operating

services of the Army about divisions; and investigated the views about

them developed at the service schools since the end of the war.

Approximately seventy officers appeared before the committee, including

Col. William (Billy) Mitchell of the Air Service and Brig. Gen. Samuel

D. Rochenback, the former chief of the Tank Corps, who testified about

two new weapon systems used in the war-the airplane and the tank.24

From the evidence, the committee

concluded that the wartime infantry division was too large and unwieldy.

In reality it had been an army corps without the proper organization.

The division's size made moving the unit by road and railroad or passing

through lines an extremely complex and time-consuming process.

Furthermore, its size had complicated the problems of command and

control of all activities in combat.25

The committee examined various

organizational options. The argument for three (versus four) infantry

regiments in the division centered on the division's probable area of

employment, North America. Experts deemed another war in Europe

unlikely, and they doubted that the Army would again fight on a

battlefield like that seen in France. They felt technological advances

in artillery, machine guns, and aviation made obsolete stabilized and

highly organized lines and flanks resting on impassable obstacles, such

as those encountered on the Western Front. Future enemies would most

likely organize their forces in great depth; therefore, the Army had to

be prepared to overcome that challenge.

Nevertheless, the committee

believed a division of four infantry regiments, although lacking the

flexibility of Pershings suggested unit, would have the necessary

mobility and striking power. Divisional support troops needed to be

reduced, but the retention of the square division preserved the

organizations for army corps and armies that had been developed during

the war. Because most officers were familiar with those units, no change

in doctrine was required above the division level. On a more mundane

level, the retention of general officers' billets also influenced those

who wanted to keep the square division. Its brigades required brigadier

generals, which allowed officers to rise from second lieutenants to

general officers within their specialties, while a smaller triangular

division would terminate that progression at the colonel level.

Concluding its examination, the committee decided a field commander

could more readily modify the square division to oppose a lesser enemy

than strengthen a smaller organization to fight a powerful foe.26

The third question remained:

Could the Army reduce the size of the square division to increase

mobility'? Recommendations to achieve this included a reduc-

[91]

tion in the number of platoons

in the infantry company from four to three and a cut in the number of

companies in the battalion by a like amount, a realignment of the ratio

between rifles and machine guns, elimination of the 155-mm. howitzers,

and the removal of unnecessary support troops. The division could obtain

additional troops from pools of combat support and service units located

at the army corps or army level. The Lassiter Committee concluded that

the square division could be cut in size yet retain much of its

firepower.27

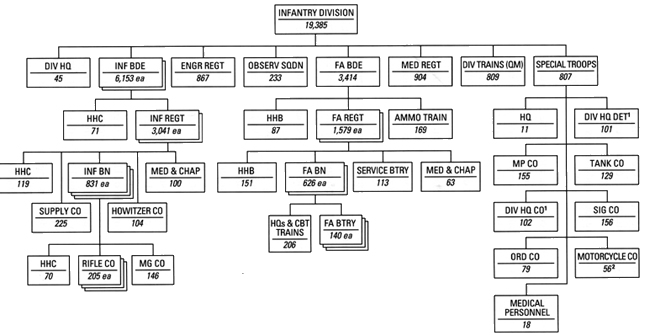

After making its report, the

Lassiter Committee prepared tentative tables of organization for the

division, which March approved on 31 August. When the War Department

distributed the draft tables in the fall of 1920 for the division, it

totaled 19,385 officers and enlisted men (Chart 5) and covered about

thirty miles of road space in march formation. To arrive at that

strength and size, each of the four infantry regiments lost 700 men. The

regiment consisted of three infantry battalions and supply, howitzer,

and headquarters companies. Each battalion included one machine gun

company and three rifle companies. The assignment of a machine gun

company to each infantry battalion simplified command and control of

those weapons, and the realignment of the guns created a substantial

saving in personnel. Machine gun units were eliminated from the infantry

brigades, and the divisional machine gun battalion was replaced by a

tank company, which was to serve as a divisional mobile reserve. The

committee endorsed Pershing's suggestion of a divisional tank company

but was aware that a single company could not mount an effective attack

on a stabilized front; the large numbers of tanks required for that type

of operation would have to come from the army level. The committee

dropped the 155-mm. howitzer regiment but stipulated its return to the

division when these weapons acquired the necessary mobility for use on

the North American continent. The engineer regiment and train were

combined and reorganized initially as a battalion because the planners

thought that the division had little need for large numbers of engineers

in mobile warfare, which precluded building extensive fortifications,

trenches, and similar works. The chief of engineers and others, however,

insisted that the regiment be retained to assure mobility, permit

training of lieutenant colonels and colonels, and provide the

opportunity for higher grade officers to serve at least one year in five

with troops. March thus decided to retain the engineer regiment but

reduced its number from 1,831 officers and enlisted men to 867. All

these changes husbanded personnel spaces and increased mobility without

lessening firepower.28

Substantial reductions also took

place in divisional services. The committee cut the size of the

ammunition train from 1,333 to 169 officers and enlisted men and changed

its mission to serve only the field artillery brigade. Ammunition

resupply for all other divisional elements shifted to the tactical units

and quartermaster train. That train consisted of half motorized and half

animal-drawn transportation, presuming the potential theater of

operations to be the rugged North American continent. Ordnance personnel

formerly

[92]

Infantry Division, 7 October 1920

Notes

1 Division headquarters detachment absorbed 27 April

1921 by the division headquarters company.

2 On 20 April 1921 the motorcycle company was moved to

the trains and the service company added to special troops.

[93]

attached to the various

regiments and the mobile repair shop were grouped in an ordnance

company, centralizing all ordnance maintenance. A signal company

replaced the signal battalion, and it assumed responsibility for message

traffic between division and brigade headquarters. Within the infantry

and field artillery regiments, men from the combat arms were to handle

all communications. The new division abandoned the train headquarters

and military police organization, following the recommendation of the

Superior Board, but retained a separate military police company. Given

the many small separate companies in its structure (division

headquarters, signal, tank, service, ordnance, and military police), the

division included a new organization, headquarters, special troops, to

handle their administration and discipline.

The committee substituted a

medical regiment for the sanitary train and revamped health services.

Three hospital companies replaced the four used during the war, and the

number of ambulance companies in the regiment was similarly reduced. In

addition, a sanitary (collecting) battalion comprising three companies

corrected the need for litter-bearers, who had previously been taken

from combat units. Veterinarians, formerly scattered throughout the

division, now formed a veterinary company. A laboratory section, a

supply section, and a service company completed the new regiment.

Despite the innovations, the regiment fielded about the same number of

men as its World War I counterpart.29

Attesting to the greater depth

envisaged for the battlefield, an air squadron of thirteen airplanes was

to serve as the reconnaissance unit for the division. As under the

wartime configuration, units for ground reconnaissance were to be

attached as needed.30

Although the committee's

infantry division was larger than that contemplated in Pershing's

proposal, the planners believed it had only those organic elements

necessary for immediate employment under normal conditions. In an

emergency, the new division could be quickly adjusted to meet an enemy

armed with inferior arms and equipment. The problem the planners tried

to address was how to design a division to deal with superior forces

without significantly modifying it. The committee's division,

nevertheless, had its opponents. Conner and Marshall of Pershing's staff

still preferred the smaller triangular division for its mobility and

ease of command and control. Years later Marshall recalled that if

Heintzelman and King had not been such "kindly characters,"

the triangular division would have been adopted instead of Drum's large

division.31

The question arises why

Pershing, after becoming chief of staff on 1 July 1921, failed to

replace the infantry division with one more compatible with his concept

of battlefield mobility. Marshall pointed out later that the basic

recommendation for retaining the square infantry division came from his

own officers, the Superior Board. To disavow their advice would have

been an embarrassment. Furthermore, by July 1921 the reorganization of

the divisions had already begun. To undo so much work would have been

unrealistic and would have implied a lack of leadership within the Army.

Therefore, the square

[94]

infantry division stood with the

understanding that it might be modified to deal with a particular enemy.32

The Lassiter Committee

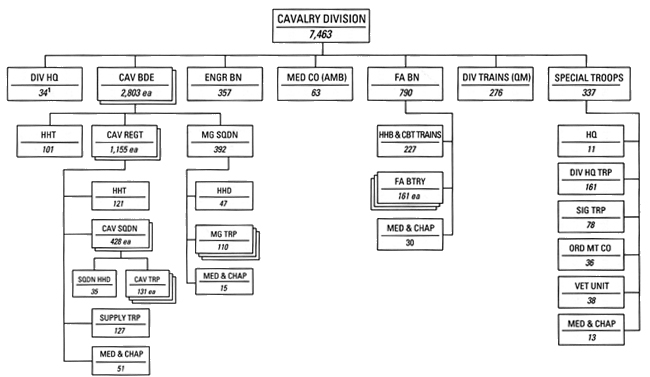

apparently devoted little attention to the cavalry division and recorded

less about its rationale for retaining the unit. Mobility and firepower

dominated the new organization. The Cavalry Journal, the official organ

for the arm, had repeatedly condemned the 1917 organization as an

absurdity. Burdened with more than 18,000 men and 16,000 animals, the

division was too large and cumbersome. It required a preposterous amount

of road space, roughly thirty miles, and was incapable of maneuver

because it lacked an efficient communication system.33

The postwar cavalry division,

approximately two-fifths the size of its predecessor, abandoned the

three-brigade structure (Chart 6). It included two cavalry brigades (two

cavalry regiments and one machine gun squadron each), one horse

artillery battalion, and combat and service support units. Each cavalry

regiment consisted of two squadrons (of three troops each), a

headquarters and headquarters troop and a service troop. Initially the

committee desired a third squadron to train men and horses, which

represented a major investment in time and money. March denied the

request because the Army was to maintain training centers. Unlike the

infantry, which incorporated the machine gun into the regiment, cavalry

maintained separate machine gun squadrons of three troops each because

of the perceived immobility of such weapons compared with other

divisional arms. A headquarters for special troops was authorized, under

which were placed the division headquarters troop, a signal troop, an

ordnance maintenance company, and a veterinary company. All

transportation was pack- or animal-drawn, except for 14 cars, 28 trucks,

and 65 motorcycles scattered throughout various headquarters elements in

the division. Without trains, the division measured approximately 6.5

miles if the men rode in columns of twos. The Army chief of staff

approved the new cavalry division on 31 August 1920.34

After approving both types of

divisions, March directed the preparation of final tables of

organization. When published the following year, the infantry division

fell just below Pershing's recommendation of 20,000, numbering 19,997

officers and enlisted men. The cavalry division totaled 7,463.35

As the War Plans Division

prepared the new tables, it also developed tables for understrength

peacetime units because the Army's leadership did not expect to be able

to maintain the number of men authorized under the National Defense Act.

These tables were designed so that the units could expand without having

to undergo reorganization. The peacetime infantry division was thus cut

to 11,000 with all elements retaining their integrity except the

division headquarters and military police companies, which were

combined. The peacetime cavalry division strength was set at 6,000. But

severe cuts in the War Department's budget made it impossible initially

even to publish the peacetime tables. Fortunately, the service journals

undertook that task.36

[95]

Cavalry Division, 4 April 1921

1 Includes four Medical Department personnel and two

Chaplains that were attached.

[96]

March directed the War Plans

Division to implement the tentative tables of organization he had

approved. Planning for reorganization of the Army had been under way

since 5 June 1920, when the War Plans Division had set up committees to

carry out the provisions of the National Defense Act. Officers from the

General Staff, the National Guard, and the Organized Reserves helped

formulate the plans.37

One committee, originally

charged with defining the missions of the National Guard and the

Organized Reserves, widened its task to encompass the Regular Army. The

committee delineated four missions for the regulars: form an

expeditionary force in an emergency; furnish troops for foreign and

coastal defense garrisons; provide personnel to develop and train the

reserve components; and supply the administrative overhead of the Army.

The National Guard's dual missions remained unchanged. It contributed to

the federal forces during national emergencies or war and supplied the

states with forces to maintain law and order and cope with local

disasters. The mission of the Organized Reserves was to expand the Army

during war or national emergencies. Because of the strong antiwar

sentiment after World War I, the expense of maintaining large numbers of

enlisted men, the lack of training facilities, and the possible adverse

effect on the recruitment for the Guard, units of the Organized Reserves

were to have only officers and enlisted cadres. After a declaration of

war or national emergency, the remainder of the enlisted men would come

from voluntary enlistments or the draft.38

Another committee looked into

the number of divisions that could be organized and supported during

peacetime. Given a Regular Army of 296,000 officers and enlisted men,

the committee determined that the War Department could maintain nine

infantry divisions (one per corps area), three cavalry divisions (one

per army area), and one infantry brigade of black troops in the United

States. Of these divisions, one cavalry and three infantry divisions

were to be ready for war while the others were to be at reduced

strength. This arrangement evenly distributed the expeditionary forces

throughout the nation and provided an infantry division to serve as a

model for the reserves within each corps area.39

In view of the great personnel

turbulence caused by the rapid demobilization, the committee recommended

that the Regular Army quickly rebuild its seven existing infantry

divisions to meet the strength in the new peacetime tables and permit

the units to conduct realistic training. The other two planned infantry

divisions could be organized after the first seven had reached their

reduced strength level, and when all nine attained that level one or

more divisions could be increased to full manning for war. How the

Regular cavalry divisions were to be formed remained unaddressed. With

486,000 men in the National Guard, the committee envisioned forming

eighteen Guard infantry divisions, two for each corps area, and three or

more Guard cavalry divisions, at least one for each army area. For the

Organized Reserves, twenty-seven infantry divisions were contem-

[97]

plated, three per corps area,

and three or more cavalry divisions, at least one for each army area.40

When March approved the

structure of infantry and cavalry divisions, he also sanctioned the

formation of divisions based on that report. Instead of three Regular

Army cavalry divisions, he saw a need for only two. The Army's

mobilization base would thus be fifty-four infantry divisions and eight

or more cavalry divisions.41

Reorganization of the Regular

Army began in late 1920 as the infantry elements of the 1st through 7th

Divisions began to adopt the new peacetime tables. In the 2d Division a

Regular Army infantry brigade, the 4th, replaced the Marine Corps unit

that had been attached to the division in France. As tables for other

divisional units became available, they too were put into effect.42

All this work quickly appeared

somewhat premature. By the fall of 1921, cuts in Army appropriations

indicated that the Regular Army could not support seven infantry

divisions in the United States. Secretary of War John W Weeks,

therefore, instituted a policy allowing inactive units to remain on the

"rolls" of the Army but in an inoperable status-that is,

without personnel and equipment. Congressional insistence on maintaining

the tactical division frameworks to ensure immediate and complete

mobilization made such arrangements necessary. Judging that nothing was

wrong with the mobilization plan, but recognizing the shortage of funds

for the fiscal year, Weeks directed that some units be taken "out

of commission" or inactivated. The policy represented a marked

departure from past Army experience. Previously, when a unit could not

be maintained or was not needed, it was removed from the rolls of the

Army either by disbandment or consolidation with another unit. Acting

otherwise threatened to obscure the Army's reduced strength through a

facade of paper units.43

Nevertheless, under the new

system the Army cut the divisional forces in September and October 1921

by inactivating the 4th through the 7th Divisions, except for the even

numbered infantry brigade in each. These brigades-the 8th, 10th, 12th,

and 14th-remained active to serve as the nuclei of their parent

divisions upon mobilization. To save even more personnel, the 2d

Division, programmed at wartime strength, was placed under the reduced

strength tables, leaving the Army without a fully manned division in the

United States.44

During the summer of 1921 the

General Staff turned its attention to Regular Army cavalry divisions. On

20 August the adjutant general constituted the 1st and 2d Cavalry

Divisions to meet partial mobilization requirements, and the following

month the commander of the Eighth Corps Area organized the 1st Cavalry

Division. The headquarters of the division and its 2d Brigade were

located at Fort Bliss, Texas, and that of the 1st Cavalry Brigade at

Douglas, Arizona. Resources were not available to organize a second

cavalry division until World War II.45

The Regular Army divisions

underwent postwar reorganization and reduction even before the War

Department could determine their permanent stations. A committee

established in June 1920 to make recommendations about posting units

never submitted a report because of the unsettled size of the Regular

Army.

[98]

When Congress funded a Regular

Army of 150,000 enlisted men for 1922, the Acting Chief of Staff, Maj.

Gen. James G. Harbord, directed a new war plans group to prepare an

outline for stationing these troops. If possible, he wanted units to

have adequate housing and training facilities as well as to be located

where the men could assist in the development of the reserve components.

The recommendations called for the Second and Ninth Corps Areas each to

have an infantry division, the Eighth Corps Area to have both infantry

and cavalry divisions, and the remaining corps areas each to have a

reinforced brigade.46

As the existing divisions and

brigades moved to their permanent stations in 1922, the Army organized

the 16th and 18th Infantry Brigades to complete the Regular Army portion

of the plan (Table 8). To fulfill mobilization requirements for

nine Regular Army infantry divisions, the adjutant general also restored

the 8th and 9th Divisions to the rolls in 1923, but they remained

inactive except for their 16th and 18th Infantry Brigades. The

stationing plan allowed the regulars to support the reserves, but only

the 2d Division was concentrated at one post-Fort Sam Houston, Texas.47

The last large unit recommended

for the Regular Army in 1920 was a black brigade scheduled for service

along the Mexican border. However, only four black regiments, two

cavalry and two infantry, remained after the war, and the War Department

decided that they should not be brigaded. In 1922 two of them, the 10th

Cavalry and the 25th Infantry, served along the border. Of the

remainder, the 9th Cavalry was stationed at Fort Riley, Kansas, the home

of the Cavalry School, and the 24th Infantry was posted to Fort Benning,

Georgia, where the Infantry School had been established.48

The post-World War I Army also

maintained forces in the Philippine Islands, China, the Panama Canal

Zone, Puerto Rico, Germany, and Hawaii. To assure that these areas were

adequately garrisoned, the War Plans Division examined their manning

needs. Based upon its findings, March approved the formation of the

Panama Canal, Hawaiian, and Philippine Divisions. In 1921 the commanders

of those overseas departments organized their units as best they could

from available personnel and equipment. The infantry and field artillery

brigades and many of the other divisional elements had numerical

designations that would be associated with the 10th, 11th, and 12th

Divisions. These elements, all table of organization units, could be

assigned wherever needed in the force. Because the divisions themselves

were not expected to serve outside of their respective territories, they

had territorial designations. The division headquarters were at Quarry

Heights, Canal Zone; Schofield Barracks, Hawaii; and Fort William

McKinley, Philippine Islands. Personnel for the Hawaiian and Panama

Canal Divisions came from the Regular Army, but the Philippine Division

was filled with both regulars and Philippine Scouts, with the latter in

the majority.49

Section V of the National

Defense Act prescribed a committee to devise plans for organizing the

National Guard divisions. Formed in August 1920, this group consisted of

Regular Army and Guard officers who represented their embryonic

[99]

Distribution of Regular Army

Divisions and Brigades, 1922

| Corps Area |

Unit |

Station |

| First |

18th Infantry Brigade

(9th Division) |

Fort

Devens, Mass. |

| Second |

1st Division |

Fort Hamilton,

N.Y. |

| Third |

16th Infantry Brigade

(8th Division) |

Fort

Howard, Md. |

| Fourth |

8th Infantry Brigade

(4th Division) |

Fort

McPherson, Ga. |

| Fifth |

10th Infantry Brigade

(5th Division) |

Fort

Benjamin Harrison, Ind. |

| Sixth |

12th Infantry Brigade

(6th Division) |

Fort

Sheridan, Ill. |

| Seventh |

14th Infantry Brigade

(7th Division) |

Fort

Omaha, Neb. |

| Eighth |

2d Division

1st Cavalry Division |

Fort Sam

Houston, Tex. Fort Bliss,

Tex. |

| Ninth |

3d Division |

Fort Lewis,

Wash. |

(Units in parentheses are the

inactive parent organizations.)

corps areas. Within a short time

the committee presented the states with a blueprint for eighteen

infantry divisions. Corps area commanders were to resolve any divergent

views or disputes among the states over the allotment of the units. The

plan offered the states the 26th through the 41st Divisions, organized

during World War I, and three new units, the 43d, 44th, and 45th

Divisions, as Guard units. The 42d "Rainbow" Division was

omitted because it lacked an association with any particular state or

geographic area. All corps areas except the Fourth received two

divisional designations. The states in the Fourth Corps Area, which had

raised the 30th, 31st, and 39th Divisions during World War I, decided

to reorganize the 30th and 39th Divisions. By the spring of 1921 the

states had agreed on the allotment of most units in the infantry

divisions, the War Department had furnished the new divisional tables of

organization, and the states had begun to reorganize their forces

accordingly. Between 1921 and 1935 the National Guard Bureau granted

federal recognition to the headquarters of all eighteen Guard infantry

divisions (Table 9). Although a few divisions lacked federally

recognized headquarters until the 1930s, most of the divisional elements

were granted federal recognition in the 1920s.50

The historical continuity of

Guard units rested upon geographic areas that supported the

organizations, and during the reorganization most units adopted the

designations used during World War I. Some shifting of units to new

geographic areas took place, resulting in some designation changes. For

example, in World War I Arkansas, Louisiana, and Mississippi had raised

the 39th Division, but

[100]

when the 39th was reorganized in

the postwar era Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana supported

the unit. Subsequently, a joint board of Regular and Guard officers

recommended that the division be renamed the 31st Division, a unit that

during the war had raised troops from Florida, Alabama, and Georgia.

Secretary Weeks approved the change, and on 1 July 1923 the 39th

Division was replaced by the 31st Division.51

The allocation and organization

of the Guard cavalry divisions followed the same procedure as the

infantry divisions. But in order to use all existing cavalry units, a

fourth cavalry division was added to the force. In 1921 the formation of

the 21st through 24th Cavalry Divisions began with the First, Second,

and Third Army Areas supporting the 21st, 22d, and 24th Cavalry

Divisions, respectively. The 23d was the nation's at-large cavalry

division, supported by all army areas (Table 10). In a short time

the divisions had the prescribed cavalry regiments and machine gun

squadrons but not the majority of their support organizations. 52

The organization of the third

component's units began in 1921 when the War Department published

Special Regulations No. 46, General Policies and Regulations for the

Organized Reserves. The regulations explained the procedures for

administering, training, and mobilizing the Organized Reserves and

provided a tentative outline for the corps area commanders to follow in

organizing the units. Using the outline and a 6 April 1921 troop

allotment for twenty-seven infantry divisions, corps area commanders set

up planning boards to establish the units. In locating them, the boards

considered the distribution and occupations of the population,

attempting to station the units where they would be most likely to

receive effective support. For example, a medical unit was not located

in an area where there was no civilian medical facility. After

determining the location of the units and giving the Guard some time to

recruit, thus avoiding competition with it, officers began to organize

the 76th through the 91st and the 94th through the 104th Divisions.53

Recruiting the units proved to

be slow. Regular Army advisers were armed with lists of potential

reservists and little else. There were not enough recruiters, office

space and equipment, or funds available to accomplish the work.

Furthermore, a marked apathy toward the military prevailed throughout

the nation. By March 1922, however, all twenty-seven infantry divisions

had skeletal headquarters (see Table 9).54

To complete the divisional

forces in the Organized Reserves, the War Department added the 61st

through the 66th Cavalry Divisions to the rolls of the Army on 15

October 1921. Corps area commanders followed the same procedures used

previously for the infantry divisions in allotting and organizing them.

Within a few months they too emerged as skeletal organizations (see

Table 10).55

Thus, in early 1923 the Army had

66 divisions in the mobilization force shared among three components11

in the Regular Army (2 cavalry and 9 infantry), 22 in the National Guard

(4 cavalry and 18 infantry), and 33 in Organized Reserves (6 cavalry and

27 infantry). In addition, three understrength

[101]

Allotment of Reserve Component

Infantry Divisions, 1921

| Corps Area |

Division |

Component |

Location |

First

|

26th

43d |

NG

NG |

Massachusetts

Connecticut, Maine, Rhode Island, and Vermont |

| |

76th

94th

97th |

OR

OR

OR |

Connecticut

and Rhode Island

Massachusetts

Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont |

Second

|

27th

44th |

NG

NG |

New York

New Jersey, New York, and Delaware |

|

77th

78th

98th |

OR

OR

OR |

New York

New Jersey and Delaware

New York |

| Third |

28th

29th |

NG

NG |

Pennsylvania

Maryland, Virginia, and District of Columbia |

|

79th

80th |

OR

OR |

Pennsylvania

Maryland, Virginia, and District of Columbia |

|

99th |

OR |

Pennsylvania |

| Fourth |

30th |

NG |

Georgia, Tennessee,

North Carolina, andSouth Carolina |

|

39th |

NG |

Alabama, Florida,

Mississippi, and Louisiana |

|

81st

82d

87th |

OR

OR

OR |

North Carolina and

Tennessee

South Carolina and Georgia

Louisiana, Mississippi,

and Alabama |

Fifth

|

37th

38th |

NG

NG |

Ohio

Kentucky, Indiana, and West Virginia |

|

83d

84th

100th |

OR

OR

OR |

Ohio

Indiana

Kentucky and West

Virginia |

Sixth

|

32d

33d

85th

86th

101st |

NG

NG

OR

OR

OR |

Michigan and

Wisconsin

Illinois

Michigan

Illinois

Wisconsin |

| Seventh |

34th |

NG |

Iowa, Minnesota,

North Dakota, and South Dakota |

|

35th

88th |

NG

OR |

Nebraska, Kansas, and

Missouri

Minnesota, Iowa, and North

Dakota |

[102]

TABLE 9-Continued

| Corps Area |

Division |

Component |

Location |

|

89th |

OR |

South Dakota,

Nebraska, and Kansas |

|

102d |

OR |

Missouri and Arkansas |

Eighth

|

36th

45th

|

NG

NG

|

Texas

Oklahoma, Colorado, New

Mexico, and Arizona |

|

90th

95th

103d |

OR

OR

OR |

Texas

Oklahoma

New Mexico, Colorado, and Arizona |

Ninth

|

40th

41st

|

NG

NG

|

California, Nevada,

and Utah

Washington, Oregon,

Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho |

|

91st

96th

104th |

OR

OR

OR |

California

Oregon and Washington

Nevada, Utah, Wyoming,

and Idaho |

Allotment of Reserve Component

Cavalry Divisions, 1921

| Division |

Component |

Location |

| 21st |

NG |

New York, Pennsylvania,

Rhode Island, and New Jersey |

| 22d |

NG |

Georgia, Illinois, Indiana,

Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Ohio, West Virginia, and Wisconsin |

| 23d |

NG |

Alabama, Massachusetts, New

Mexico, North Carolina, Tennessee, Texas,

and Wisconsin |

| 24th |

NG |

Idaho, Iowa, Kansas,

Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, Utah,

Washington, and Wyoming |

| 61st |

OR |

New York and New Jersey |

| 62d |

OR |

Maryland, Virginia,

District of Columbia, and Pennsylvania |

| 63d |

OR |

Tennessee, Louisiana,

Georgia, North Carolina, Texas, Oklahoma, and Colorado |

| 64th |

OR |

Kentucky, Massachusetts,

Vermont, and New Hampshire |

| 65th |

OR |

Illinois, Michigan, and

Wisconsin |

| 66th |

OR |

Nebraska, Missouri, Utah,

and North Dakota |

[103]

infantry divisions were located

overseas. No separate brigades existed. In almost every case, however,

these divisions, which varied from inactive units to partially manned

organizations, were "paper tigers:"

After World War I the Army

quickly demobilized its forces, but memories of the unpreparedness of

1917 caused the nation to change the way it maintained its military

forces. Infantry and cavalry divisions, rather than regiments or smaller

units, became the pillars that would support future mobilization.

Officers examined the structure of those pillars and adopted a modified,

but powerful, square infantry division designed for frontal attack and a

small light cavalry division for reconnaissance. Although the lessons of

war influenced the structure of these divisions, more traditional

criteria regarding their local geographical employment continued to

affect their organization. But with no real enemy in sight and the

nation's adoption of a generally isolationist foreign policy, it is not

surprising that Congress provided neither the manpower nor the materiel

to equip even a caretaker force adequately.

[104]

Endnotes

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

page created 29 June 2001

Return to the

Table of Contents

-