Chapter III:

The Test -- World War I

Both [French and British]

commissions were anxious for an American force, no matter how small . .

. . I opposed this on the ground that the small force would belittle our

effort; was undignified and would give a wrong impression of our

intentions. I held out for at least a division to show the quality of

our troops and command respect for our flag.

Maj. Gen. Hugh L. Scott 1

World War I, an unprecedented

conflict, forced fundamental changes in the organization of United

States Army field forces. The infantry division remained the Army's

primary combined arms unit, but the principles governing its

organization took a new direction because of French and British

experiences in trench warfare. Column length or road space no longer

controlled the size and composition of the infantry division; instead,

firepower, supply, and command and control became paramount. The cavalry

division received scant attention as the European battlefield offered

few opportunities for its use.

Between 6 April 1917, when the

nation declared war, and 12 June, when the first troops left the United

States for France, the War College Division of the Army General Staff'

revised the structure of the infantry division extensively. British and

French officers spurred the changes when they visited Washington, D.C.,

to discuss the nation's participation in the war. They believed the

American division lacked firepower and presented command and control

problems because of its many small units. But they also had their own

political-military agenda. Believing that time precluded organizing and

training U.S. units, they wanted the nation's immediate involvement in

the war to be through a troop replacement program for their drained

formations, a scheme that became known as "amalgamation.."2

Chief of Staff Maj. Gen. Hugh L.

Scott opposed Americans' serving in Allied units, believing that the

U.S. division could be reorganized to overcome any French and British

objections. Such a unit would prove the quality of the American soldier

and ensure that the Allies did not underestimate the nation's war

efforts. Scott directed the War College Division to study a divisional

structure comprising two infantry brigades, each having

two large

infantry regiments, as a means of reducing the span of control. It was

also to include light and heavy

[47]

General Scott

artillery, signal

and engineer troops, and service units. A small

division, some 13,000 infantrymen, would allow

greater mobility and enhance the ability to

exchange units in the line and maintain battle

momentum. The French and the British had found

that for each unit on line-army corps, division,

brigade, regiment, battalion, or company-they

needed a comparable unit prepared to relieve it

without mixing organizations from various

commands. The French had tried relief by army

corps but had settled on relief by small

divisions. Scott felt that his proposal would

ease the difficulty of exchanging units on the

battlefield.3

By 10 May 1917, Majs. John

McAuley Palmer, Dan T. Moore, and Brunt Wells of the War College

Division outlined a division of 17,700 men, which included about

11,000 infantrymen in accordance with Scott's idea. In part it

resembled the French square division. Planners eliminated 1 infantry

brigade and cut the number of infantry regiments from 9 to 4,

thereby reducing the number of infantry battalions from 27 to 12.

But regimental firepower increased, with the rifle company swelling

from 153 officers and enlisted men to 204, and the number of

regimental machine guns rising dramatically from 4 to 36. To

accommodate the additional machine guns, Palmer, Moore, and Wells

outlined a new infantry regimental structure that consisted of

headquarters and supply companies and three battalions. Each

battalion had one machine gun company and three rifle companies.

Given the reduction in the number of infantry units, the proportion

of artillery fire support per infantry regiment increased without

altering the number of artillery regiments or pieces. The new

division still fielded forty-eight 3-inch guns, now twelve pieces

per infantry regiment. The division was also authorized a regiment

of twenty-four 6-inch howitzers for general support, and twelve

trench mortars of unspecified caliber completed the division's

general fire support weapons.4

Cavalry suffered the largest

cut, from a regiment to an element with the division headquarters, a

change in line with British and French recommenda-

[48]

General Bliss

tions. The Allies argued that

trench warfare, dominated by machine guns and artillery weapons,

denied cavalry the traditional missions of reconnaissance, pursuit,

and shock action. Mounted troops, possibly assigned to the division's

headquarters company, might serve as messengers within the division

but little more. The Allies further advised that the Army should not

consider sending a large cavalry force to France. Horses and fodder

would occupy precious shipping space, and the French and British had

an abundance of cavalry. Engineer, signal, and medical battalions and

an air squadron rounded out the divisions. 5

To conduct operations, the

French advocated a functional divisional staff, that would include

a chief of staff and a chief of

artillery as well as intelligence, operations, and supply officers,

along with French interpreters. Although small, such a body would have

sufficient resources to allow the division to function as a tactical

unit while a small headquarters troop would furnish work details.

Adjutants alone were to comprise the staff of the infantry and

artillery brigades, which had no headquarters troop for work details.

The next higher headquarters, the army corps, would provide planning

and administration for active operations.6

General Bliss

tions. The Allies argued that

trench warfare, dominated by machine guns and artillery weapons,

denied cavalry the traditional missions of reconnaissance, pursuit,

and shock action. Mounted troops, possibly assigned to the division's

headquarters company, might serve as messengers within the division

but little more. The Allies further advised that the Army should not

consider sending a large cavalry force to France. Horses and fodder

would occupy precious shipping space, and the French and British had

an abundance of cavalry. Engineer, signal, and medical battalions and

an air squadron rounded out the divisions. 5

To conduct operations, the

French advocated a functional divisional staff, that would include

a chief of staff and a chief of

artillery as well as intelligence, operations, and supply officers,

along with French interpreters. Although small, such a body would have

sufficient resources to allow the division to function as a tactical

unit while a small headquarters troop would furnish work details.

Adjutants alone were to comprise the staff of the infantry and

artillery brigades, which had no headquarters troop for work details.

The next higher headquarters, the army corps, would provide planning

and administration for active operations.6

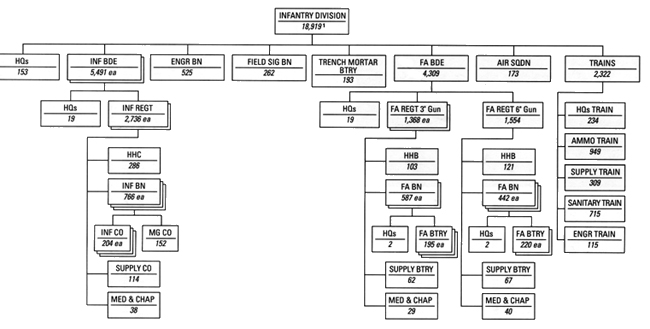

Based on the report of 10 May,

War College Division officers prepared tables of organization that

authorized 19,000 officers and enlisted men for the division (Chart

3), an increase of about 1,300. No basic structural changes took

place; self-sufficiency justified the additional men. On 24 May Maj.

Gen. Tasker H. Bliss, the Acting Chief of Staff, 7

approved the tables,

but only for the initial expeditionary force. He hoped, as did the

staff, that Congress would authorize a larger infantry regiment,

providing it with more firepower. Bliss also recognized that the

expeditionary commander might wish to alter the division. With these

factors in mind, he felt that time would permit additional changes in

the divisional structure because a second division would not deploy in

the near future. If a large expeditionary force was dispatched in the

summer of 1917, its deployment would rest on political, not military,

objectives.8

Early in May Scott alerted

Maj. Gen. John J. Pershing, commander of the Southern Department,

about the possibility of sending an expeditionary force to France and

asked him to select one field artillery and four infantry regiments

[49]

Infantry Divisions, 24 May 1917

1 Memo, WCD for CofS, 21 May 1917, sub: Plans for a possible

expeditionary force to France, indicates that the division would total

19,922, but a check of the, math indicates that the total was 18,919.

[50]

16th Infantry, 1st Division, parades in Paris, 4 July 1917; below,

Gondrecourt, France, training area.

[51]

for overseas service. Pershing

nominated the 6th Field Artillery and the 16th, 18th, 26th, and 28th

Infantry. Following a preplanned protocol, the French requested the

deployment of a division to lift Allied morale, and President Woodrow

Wilson agreed.9

Shortly thereafter an

expeditionary force was organized. The regiments picked by Pershing, filled to war

strength with recruits, moved to Hoboken, New Jersey. On 8 June Brig. Gen.

William L. Sibert assumed command and began organizing the 1st Expeditionary

Division. Four days later its initial elements sailed for France without most of

their equipment, as the French had agreed to arm them. Upon arrival in France,

one divisional unit-the 2d Battalion, 16th Infantry paraded on 4 July in

Paris, where the French people enthusiastically welcomed the Americans. Following

the reception, the division's unschooled recruits, except the artillerymen,

underwent six months of arduous training at Gondrecourt, a training area

southeast of Verdun, while the division artillery trained at a French range near Le

Valdahon.10

Upon completion of the Army's

first World War I divisional study the 1st Expeditionary Division was

deployed. Even before that investigation was finished, however, two new

groups initiated additional studies. Pershing, who had been appointed

commander of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) on 26 May, headed one

group; Col. Chauncey Baker, an expert in military transportation and a

West Point classmate of Pershing, headed the other. Previously Majors

Palmer, Moore, and Wells had consulted Pershing as they developed their

ideas about the infantry division, and he found no fault with them.

Nevertheless, Pershing's staff began exploring the organization of the

expeditionary forces en route to France. Lt. Col. Fox Conner, who had

served as the War College Division interpreter for the French mission

while in Washington; the newly promoted Lieutenant Colonel Palmer; and

Majs. Alvin Barker and Hugh A. Drum assisted Pershing in this work.11

Independently, Secretary of War

Newton D. Baker directed Colonel Baker and twelve other officers to study

the British, French, and Belgian armies. After six weeks the secretary

expected Baker to make recommendations that would help in organizing

American forces. Colonel Baker himself met Pershing in England, and both

agreed to work together after Baker conducted separate investigations in

England, France, and Belgium. A single report, known as the General

Organization Project, resulted from these efforts. Reflecting a consensus

of the Baker and Pershing planners, it covered all aspects of the

organization of the AEF except for the service of rear troops. 12

The General Organization Project

described an infantry division of about 25,000 men consisting of two

infantry brigades (each with two infantry regiments and one three-company

machine gun battalion), a field artillery brigade (com-

[52]

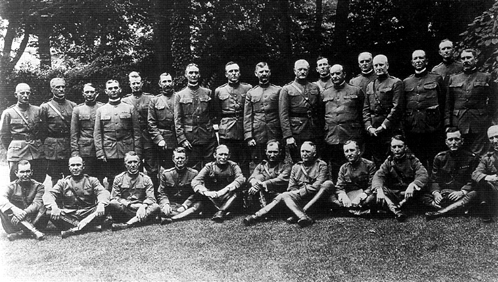

\

\

Officers of the American Expeditionary Forces and the Baker mission

prising one 155-mm. howitzer

regiment, two 3-inch [approximately 75-mm.] gun regiments, and one trench

mortar battery), an engineer regiment, a signal battalion, and trains. The

trains included the division's headquarters troop and military police,

ammunition, supply, ambulance, field hospital, and engineer supply units.

The air squadron was omitted from the division. 13

During the course of their work,

Pershing and Baker reversed the rationale for the division. Instead of an

organization that could easily move in and out of the trenches, the

division was to field enough men to fight prolonged battles. Both planning

groups sensed that the French and British wanted that type of division but

lacked the resources to field it because of the extensive losses after

three years of warfare. To sustain itself in combat, the division needed

more, not less, combat power. The infantry regiment reverted to its prewar

structure of headquarters, machine gun, and supply companies and three

battalions each with four rifle companies. The rifle companies were

increased to 256 officers and enlisted men, and each company fielded

sixteen automatic rifles.14

Because the law specified only one machine

gun company per regiment, the General Organization Project recommended the

organization of six brigade and five divisional machine gun companies.

These were to be organized into two battalions of three companies each and

one five-company battalion. Eight of these companies augmented the four in

the infantry regiments, thus providing each divisional infantry battalion

with a machine gun company. The three remaining companies were assigned as

the divisional reserve; two were comparable to those in the infantry

regiments, and the other was an armored motorcar machine gun company

labeled "tank" company.15

[53]

The major dispute between

Pershing's staff and the Baker Board developed over the artillery general

support weapon. The board's position, presented by future Chief of Staff

Charles E Summerall, was that one regiment should be equipped with either

the British 3.8- or 4.7-inch howitzer because of their mobility, while

Pershing's officers favored a regiment of French 155-mm. howitzers. The

need for firepower and the possibility of obtaining 155s from the French

undoubtedly influenced the staff, and its view prevailed. For high-angle

fire, Baker's group proposed three trench mortar batteries in the

division, but settled for one located in the field artillery brigade and

six 3-inch Stokes mortars added to each infantry regiment.16

The report also recommended

changes in cavalry and engineer divisional elements. An army corps, it

suggested, needed two three-squadron cavalry regiments to support four

divisions. Normally one squadron would be attached to each division, and

the army corps would retain two squadrons for training and replacement

units. The squadrons withdrawn from the divisions would then be

reorganized and retrained. Divisional engineer forces expanded to a

two-battalion regiment, which would accommodate the amount of construction

work envisioned in trench warfare. Infantrymen would do the simple digging

and repairing of trenches under engineer supervision, while the engineer

troops would prepare machine gun and trench mortar emplacements and

perform major trench work and other construction.17

Pershing sought a million men by

the end of 1918. He envisioned five army corps, each having four combat

divisions, along with a replacement and school division, a base and

training division, and pioneer infantry, cavalry, field and antiaircraft

artillery, engineer, signal, aviation, medical, supply, and other

necessary units. The base and training division was to process incoming

personnel into the theater, and the replacement and school division was to

provide the army corps with fully trained and equipped soldiers. Because

these support divisions did not need to be at full strength, Pershing

foresaw some of the soldiers serving as replacements in combat divisions

and others as cadre in processing and training units. He also anticipated

that some surplus units would be attached to army corps or armies.

Furthermore, Pershing wanted a seventh division for each army corps, not

counted in his desired force of a million men, which was to be organized

and maintained in the United States to train officers before they came to

France. To assemble the first army corps, he asked the War Department to

send two combat divisions, followed by the replacement and school

division, the other two combat divisions, and finally the base and

training division. When five army corps arrived in France, Pershing would

have twenty combat divisions and ten processing and replacement divisions.

Also, five more divisions were to be in training in the United States.18

The General Organization Project

reached Washington in July, and Bliss noted the shift in divisional

philosophy. Instead of a division that could move quickly in and out of

trenches, Pershing wanted a unit with sufficient overhead (staff,

communications, and supply units) and enough infantry and artillery to

permit continuous fighting over extended periods. Because Pershing would

com-

[54]

mand the divisions sent

to Europe, neither Bliss nor the General Staff questioned his

preference. Also, the lack of experienced divisional-level officers

and staffs made a smaller number of larger divisions more practical.19

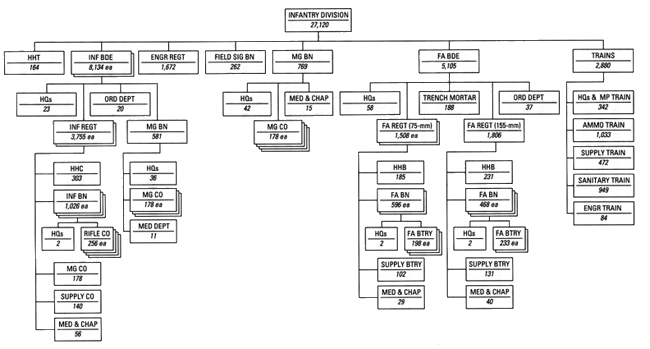

Using the General Organization

Project, the War College Division prepared tables of organization,

which the War Department published on 8 August 1917 (Chart 4). The

tables for what became known as the "square division"

included a few changes in the division's combat arms. For example, the

five-company divisional machine gun battalion was reduced to four

companies by eliminating the armored car machine gun unit. Pershing

had decided to submit a separate tank program because he considered

tanks to be assets of either army corps or field army. In the infantry

regiment, the planners made the 3-inch mortars optional weapons and

added three one-pounder (37-mm.) guns as antitank and anti-machine gun

weapons. The supply train was motorized, and the ammunition and

ambulance trains were equipped with both motor- and horse-drawn

transport. The additional motorized equipment in the trains stemmed

from the quartermaster general's attempt to ease an expected shipping

shortage, not to enhance mobility. Crated motor vehicles occupied less

space in an ocean transport than animals and fodder.20

The War College Division

also provided a larger divisional staff than Pershing had recommended

because the unit most likely would have both tactical and

administrative roles. The staff comprised a chief of staff, an

adjutant general, an inspector general, a judge advocate, and

quartermaster, medical, ordnance, and signal officers. In addition,

interpreters were attached to overcome any language barriers,

particularly between the Americans and the French. As an additional

duty, the commanders of the field artillery brigade and the engineer

regiment held staff positions. A division headquarters troop with 109

officers and enlisted men would furnish the necessary services for

efficient operations. The infantry brigade headquarters included the

commander, his three aides, a brigade adjutant, and eighteen enlisted

men who furnished mess, transportation, and communications services.

The field artillery brigade headquarters was larger, with nine

officers and forty-nine enlisted men, but had similar functions.

Planners did not authorize headquarters detachments for either the

infantry or field artillery brigade.21

While Pershing and Baker

investigated the organizational requirements for the expeditionary

forces, steps were taken to expand the Army at home. These measures

included the formation of all 117 Regular Army regiments authorized in

the National Defense Act of 1916 and the drafting of the National

Guard into federal service and of 500,000 men through a selective

service system. Draftees were to fill out Regular Army and National

Guard units and to provide manpower for new units. Organizations

formed with all selective service personnel eventually became

"National Army" units. Although the War Department was

unsure of either the final structure of the infantry division or the

number of divisions need-

[55]

Infantry Division, 8 August 1917

[56]

ed, it decided to organize 32

infantry divisions immediately, 16 in the National Guard and 16 in the

National Army. The Army contemplated no additional Regular Army divisions.

Although existing Regular Army regiments could be shipped overseas and

organized into divisions if necessary, most regulars were needed to direct

and train the new army. Unlike past wars, draftees rather than volunteers

would fight World War 1.22

To organize National Guard and

National Army divisions, the Army Staff adopted extant plans. For the

Guard it used the Militia Bureau's scheme developed following the passage

of the National Defense Act, and for the National Army it turned to a

contingency plan drawn up in February 1917 to guide the employment of

draftees. Divisions in both components had geographic bases. As far as

practicable, the area that supported a Guard division coincided with a

National Army divisional area.23

The thirty-two new divisions

needed training areas, but the Army had only one facility large enough to

train a division, Camp Funston, a subpost of Fort Riley, Kansas.

Therefore, the staff instructed territorial commanders to select an

additional thirty-two areas, each large enough to house and train a

division. Early in the summer Secretary Baker approved leasing the sites.

To save money, he decided to build tent cities for the National Guard

divisions in the southern states, where winters were less severe, while

camps for National Army divisions, which were to have permanent buildings,

were located within the geographic areas that supported them.24

Establishing a tentative occupancy

date of 1 September, the Quartermaster Corps began constructing the

training areas in June. It designed each site to accommodate a

three-brigade division as called for under the prewar tables of

organization. When Bliss approved the square division in August, the camps

had to be modified to house the larger infantry regiments. Although the

changes delayed completion of the training areas, the troops' arrival

date, 1 September, remained firm.25

The War College Division and the

adjutant general created yet another system for designating divisions and

brigades and their assigned elements. Divisions were to be numbered 1

through 25 in the Regular Army, 26 through 75 in the National Guard, and

76 and above in the National Army. Within the Regular Army numbers,

mounted or dismounted cavalry divisions were to begin with the number 15.

The National Defense Act of 1916 provided for sixty-five Regular Army

infantry regiments, including a regiment from Puerto Rico. From those

units, excluding the ones overseas, the War Department could organize

thirteen infantry divisions in addition to the 1st Expeditionary Division

already in France. This arrangement explains the decision to begin

numbering Regular Army cavalry divisions with the digit 15. The system did

not specify the procedure for numbering National Guard or National Army

cavalry divisions. It reserved blocks of numbers for infantry, cavalry,

and field artillery brigades, with 1 through 50 allotted to the Regular

Army, 51 through 150 to the National Guard, and 151 and

[57]

above to the National Army. The

designation of each Guard or National Army unit, if raised by a single

state, was to have that state's name in parentheses. Soldiers in

National Guard and National Army units were also to wear distinctive

collar insignia showing their component.26

As the summer of 1917 advanced,

the War Department announced additional details. In July it identified

specific states to support the first sixteen National Guard and the

first sixteen National Army divisions and designated the camps where

they would train. At that time the department announced that the

designations of the National Guard's 5th through 20th Divisions were to

be changed to the 26th through the 41st to conform with the new

numbering system. In August the adjutant general placed the 76th through

the 91st Divisions, National Army units, on the rolls of the Army and

announced the appointment of commanders for both National Guard and

National Army divisions. In addition to the 1st Expeditionary Division

in France, the War College Division adopted plans to organize six more

Regular Army divisions. No plans were made to concentrate their

divisional elements for training, but they were to be brought up to

strength with draftees.27

When the initial planning phase

for more divisions closed, the mobilization program encompassed 38

divisions-16 National Guard, 16 National Army, and 6 Regular Army. With

these, exclusive of the 1st Expeditionary Division in France,

redesignated on 6 July as the 1st Division, the War Department met

Pershing's requirement for thirty divisions. The divisions in excess of

Pershing's needs were to be held in the United States as replacement

units.

Between 22 August 1917 and 5

January 1918, the Army Staff authorized one cavalry and three

additional infantry divisions, for a total of forty-three divisions.

But establishing these units proved a monumental task for which the

Army was woefully unprepared. Besides unfinished training areas and

the absence of a system for classifying new recruits as they entered

service, the Army faced a shortage of equipment and officers. The

quartermaster general claimed that the only items of clothing he

expected to be available to outfit the National Army men were hats and

cotton undershirts. Except for a handful of Regular Army officers, the

National Army made do with newly minted officers fresh from twelve

weeks of training.28

Formation of the new Army

nevertheless began with the organization of the National Guard

divisions. In August Guard units, which had been drafted into federal

service and temporarily housed in state camps and armories, reported to

their designated training camps and formed divisions in agreement with

the 3 May tables. During September and October the division commanders

reorganized the units to conform to the new square configuration as the

26th through 41st Divisions (Table

3).

[58]

Geographic Distribution of National Guard Divisions, World War I

Old

Designation |

New

Designation |

Geographic Area |

Camp |

| 5th |

26th |

Maine, New Hampshire,

Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island,

and Connecticut |

-

Greene, N.C. I

|

| 6th |

27th |

New York |

Wadsworth, S.C |

|

7th

|

28th

|

Pennsylvania |

Hancock, Ga. |

| 8th |

29th |

New Jersey, Virginia,

Maryland, Delaware,2 and District of

Columbia |

McClellan, Ala. |

| 9th |

30th |

Tennessee, North Carolina, and

South Carolina |

Sevier, S.C. |

| 10th |

31st |

Georgia, Alabama,

and Florida |

Wheeler, Ga. |

| 11th |

32d |

Michigan and

Wisconsin |

MacArthur, Tex. |

| 12th |

33d |

Illinois |

Logan, Tex. |

| 13th |

34th |

Minnesota, Iowa, Nebraska, North

Dakota, and South Dakota |

Cody, N.M. |

| 14th |

35th |

Missouri and

Kansas |

Doniphan, Okla |

| 15th |

36th |

Texas and Oklahoma |

Bowie, Tex |

| 16th |

37th |

Ohio and West

Virginia3 |

Sheridan, Ala |

| 17th |

38th |

Indiana and Kentucky |

Shelby, Miss |

| 18th |

39th |

Louisiana,

Mississippi, and Arkansas |

Beauregard, La. |

| 19th |

40th |

California, Nevada,

Utah, Colorado,

Arizona, and New Mexico |

Kearny, Calif. |

| 20th |

41st |

Washington,

Oregon, Montana, and

Wyoming |

Fremont, Calif4 |

1 Division concentrated at

various locations in New England.

2 Delaware troops relieved

from the division 8 January 1918.

3 Reassigned to the 38th

Division.

4 Camp changed from Camp

Fremont, California, to Camp Greene, North Carolina.

[59]

At that time division commanders

broke up many historic state regiments to meet the required

organizations in the new tables, a measure that incensed the states and

the units themselves.29

The histories of the 26th and 41st Divisions were somewhat different. Deciding to send another division

to France as soon as possible, on 22 August Secretary Baker ordered

Brig. Gen. Clarence E. Edwards, commander of the Northeastern

Department, to organize the 26th Division in state camps and armories

under the square tables. Without assembling as a unit, the 26th departed

the following month for France, where it underwent training. To

accelerate the formation of the 41st Division, its training site was

shifted from Camp Fremont, California, which needed a sewage system, to

Camp Greene, North Carolina. Maj. Gen. Hunter Liggett took over the camp

on 18 September and the next day organized the 41st under the 8 August

tables. In October its first increment of troops departed for France.30

Before the 26th Division went

overseas in September, many states had wanted the honor of having their

units become the first in France and pressed Baker and the War

Department for that assignment. To stop the clamor, Baker proposed to

Bliss that he consider sending a division to Europe representing many

states. Maj. Douglas MacArthur, a General Staff officer, had earlier

suggested that when Guard divisions adopted the new tables some militia

units would become surplus and might be grouped as a division. MacArthur

described the division as a "rainbow," covering the entire

nation. After consulting Brig. Gen. William A. Mann, Chief of the

Militia Bureau, the War College Division drafted a scheme to organize

such a division with surplus units from twenty-six states and the

District of Columbia. On 14 August the 42d Division was placed on the

rolls of the Army, and six days later its units began arriving at Camp

Mills, New York, eventually a transient facility for soldiers going to

France. The following month Mann, who was reassigned from the Militia

Bureau and appointed the division commander, organized the "Rainbow

Division," which sailed for France a few weeks later.31

The organization of the sixteen

National Army divisions also began in August when the designated

division commanders, all Regular Army officers, and officer cadres

reported to their respective training camps. Immediately thereafter the

commanders established the 76th through the 91st Divisions and a depot

brigade for each (Table 4).32

On 3 September the first draftees arrived.

The depot brigades processed the new draftees while the divisions began

a rigorous training program. Many of these men, however, quickly became

fillers for National Guard and Regular Army units going overseas, one of

the reasons that National Army divisions were unready for combat for

many months.33

One Regular Army infantry

division, the 2d, was organized in France. When the first troops

deployed, the U.S. Marine Corps wanted a share of the action, and

Secretary Baker agreed that two Marine regiments should serve with the

Army. The 5th Marines sailed with the 1st Expeditionary Division, and

Pershing assigned

[60]

Geographic Distribution of National Army Divisions World War I

| Designation |

Geographic Area |

Camp |

| 76th |

Maine, New Hampshire,

Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island,

and Connecticut |

Devens, Mass. |

| 77th |

Metropolitan New York

City |

Upton, N.Y. |

| 78th |

New York and northern

Pennsylvania |

Dix, N.J. |

| 79th |

Southern Pennsylvania |

Meade, Md. |

| 80th |

New Jersey, Virginia,

Maryland, Delaware, and District of Columbia |

Lee, Va.

|

| 81st |

Tennessee, North Carolina,

and South Carolina |

Jackson, S.C. |

| 82d |

Georgia, Alabama, and

Florida

|

Gordon, Ga.

|

| 83d |

Ohio and West Virginia |

Sherman, Ohio |

| 84th |

Indiana and Kentucky |

Taylor, Ky. |

| 85th |

Michigan and Wisconsin |

Custer, Mich. |

| 86th |

Illinois |

Grant, Ill. |

| 87th |

Arkansas, Louisiana, and

Mississippi |

Pike, Ark. |

| 88th |

Minnesota, Iowa, Nebraska,

North Dakota, and South Dakota |

Dodge, Iowa

|

| 89th |

Missouri, Kansas, and

Colorado |

Funston, Kans. |

| 90th |

Texas, Oklahoma, Arizona,

and New Mexico |

Travis, Tex.

|

| 91st |

Washington, Oregon,

California, Nevada,

Utah, Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming |

Lewis, Wash. |

them as security detachments and

labor troops in France. Shortly thereafter he advised the War Department

that the marines did not fit into his organizational plans and

recommended that they be converted to Army troops. The marines, however,

continued to press for a combat role. Eventually the Departments of War

and the Navy agreed that two Regular Army infantry regiments, initially

programmed as lines of communication troops, and the two Marine

regiments (one serving in France and one from the United States) should

form the core of the 2d Division. The adjutant general informed Pershing

of the decision, and Brig. Gen. Charles A. Doyen, U.S. Marine Corps,

organized the 2d Division on 26 October 1917 at Bourmont, Haute-Marne,

France. The division eventually included the 3d Infantry Brigade (the

9th and 23d Infantry and the 3d Machine Gun Battalion), the 4th Marine

Brigade (the 5th and 6th Marines and the 6th Machine Gun Battalion

[Marines]), the 2d Field Artillery Brigade, and support units.34

[61]

Draftees drill in civilian clothes, Camp Upton, New York

The 3d through the 8th

Divisions, Regular Army units, were organized between 21 November 1917

and 5 January 1918 in the United States. Of these divisions, only the

4th and 8th assembled and trained as units before going overseas because

the Guard and National Army units occupied the divisional training

areas. The 4th replaced the 41st Division at Camp Greene, and the 8th

occupied Camp Fremont upon its completion. To fill the divisions,

partially trained draftees were transferred from National Army units, a

process that eroded the concept of the three separate components-the

Regular Army, the National Guard, and the National Army.35

As the three-component idea

deteriorated, Baker discussed the elimination of such distinctions

altogether with Scott and Bliss. The officers opposed the action,

believing it would undermine the local pride that National Guard and

National Army units exhibited. General Peyton C. March, who had served

as Army Chief of Staff since the spring of 1918, disagreed. He announced

that the nation had but one army, the United States Army, and

discontinued the distinctive names and insignia for the three

components. After 7 August 1918, all soldiers, including those in

divisions, wore the collar insignia of the United States Army.

Nevertheless, the men still considered their divisions as belonging to

the Regular Army, the National Guard, or the National Army.36

All-black units comprised a

special category of troops. The draft of the

[62]

Camp Meade, Maryland, 1917

National Guard included some

black units, and the War Department directed the organization of

additional regiments if sufficient numbers of black draftees reported to

National Army camps. In October 1917 Secretary Baker ordered the units

at Camps Funston, Grant, Dodge, Sherman, Dix, Upton, and Meade to form

the 92d Division. Brig. Gen. Charles C. Ballou organized a division

headquarters at Camp Funston later that month, but the division did not

assemble or train in the United States. The following June the 92d moved

to France and first saw combat in the Lorraine area.37

After the organization of the

92d there remained the equivalent of four black infantry regiments in

the United States, and the staff anticipated that their personnel would

serve as replacements for the 92d or lines of communication troops in

France. For administrative purposes, these black troops were organized

in December 1917 as the 185th and 186th Infantry Brigades. Shortly

thereafter the Headquarters, 93d Division (Provisional), a small

administrative unit, was organized. Never intended to be a tactical

unit, it simply exercised administrative control over the two brigades

while they underwent training.38

Puerto Ricans comprised another

segregated group in the Army, and the General Staff gave special

consideration to them when organizing divisions. Initially it planned a

provisional Puerto Rican division using the prewar tables that called

for three infantry brigades, but that idea was soon dropped. Instead,

the War Plans

[63]

Division, which had

succeeded the War College Division, endorsed the creation of a

Spanish-speaking square division (less the field artillery brigade),

to be designated the 94th Division. Maj. Gen. William J. Snow, Chief

of Field Artillery, opposed the organization of the field artillery

brigade because the Army lacked Spanish-speaking instructors and an

artillery training area in Puerto Rico. He believed that a brigade

could be furnished from artillery units in the United States. Others

opposed formation of the division on ethnic grounds, arguing that

Puerto Ricans might not do well in combat. Proponents countered that

good leadership would guarantee good performance in combat. The staff

worked out a compromise. The divisional designation was to be

withheld, but the organization of the divisional elements was to

proceed. The infantry regiments were assigned numbers 373 through 376,

which would have been associated with the National Army's 94th

Division. During the war the Army organized only three of those

regiments, with approximately 17,000 Puerto Rican draftees, but never

formed the 94th Division itself 39

Pershing ignored French and

British recommendations that cavalry divisions not be sent to France.

Himself a cavalryman, the general decided that he might use such a

force as a mobile reserve. After all, both Allies still hoped for a

breakthrough and maintained 30,000 to 40,000 mounted troops to exploit

such an opportunity. Most of the Regular Army cavalry regiments,

however, had been scattered in small detachments along the Mexican

border and had furnished personnel for overseas duty. The cavalry arm

needed to be rebuilt. That process began when the secretary of war

approved the formation of the 15th Cavalry Division. On 10 December

1917, Maj. Gen. George W Reed organized its headquarters at Fort

Bliss, Texas; the 1st Cavalry Brigade at Fort Sam Houston, Texas; the

2d Brigade at Bliss, Texas; and the 3d at Douglas, Arizona. The

division had two missions: to prepare for combat in France and to

patrol the Mexican border.40

The breakup of the 15th

Cavalry Division began shortly after its formation. Responding to

Pershing's request for army corps troops, the War Department detached

the division's 6th and 15th Cavalry and sent them to France. Because

of the paucity of cavalry units, they were not replaced in the

division. In May 1918 Maj. Gen. Willard Holbrook, the Southern

Department commander, informed the chief of staff of the Army that the

situation on the border required the remainder of the division to

remain there. Holbrook further stated that border-patrol work could be

improved if the divisional organization were abandoned. On 12 May the

division headquarters was demobilized, but the division's three

cavalry brigades continued to serve on the border until July 1919,

when their headquarters were also demobilized. With the demobilization

of the division, Pershing's hope for a cavalry division died. Baker

informed him that all remaining mounted troops were needed in the

United States.41

When the first phase of the

mobilization ended on 5 January 1918, the Army had 42 infantry

divisions, 1 short-lived cavalry division, and 1 provisional division

of 2 infantry brigades. All divisions were in various stages of

training. Shortages of uniforms, weapons, and equipment remained

acute.

[64]

By the spring of 1918 Pershing

had requested more divisions than he had outlined in the General

Organization Project because the Allies' fortunes had drastically

changed. Russia had been forced out of the war, and the British and

French armies had begun to show the strain of manpower losses sustained

since 1914. Although Germany also felt the effects of the long war, it

was busy transferring troops from the now defunct Eastern Front to the

West for one final offensive. Alarmed, the Allies wanted 100 U.S. Army

divisions as soon as possible. Within the War Department the request

caused considerable debate as to its feasibility, particularly with

regard to raw materials, production, and shipping of war supplies. Only

in July did President Wilson approve a plan to mount a 98-division force

by the end of 1919, 80 for France and 18 in reserve in the United

States.42

During the debate over force

structure, the War Plans Division considered whether the additional

divisions should be Regular Army or National Army units. Not all Regular

Army infantry regiments authorized under the National Defense Act of

1916 had been assigned to divisions, thus raising the question of why

those regiments should exist. The War Plans Division recommended that

the Regular Army infantry regiments become the nuclei of the next group

of divisions, which would be completed with National Army units. The

National Army units would pass out of existence after the war.43

In July 1918 Secretary Baker

approved the organization of twelve more divisions. Regular Army

infantry regiments in the United States and from Hawaii and Panama

formed the core of the 9th through 20th Divisions (Table 5).44

These

divisions, organized between 17 July and 1 September, occupied camps

vacated by National Guard and National Army divisions that had gone to

France. Conforming to Pershing's fixed army corps idea, the 11th and

17th Divisions were scheduled to be replacement and school divisions,

while the 14th and 20th were programmed as base and training divisions.

The only change in these divisions from the others was in their

artillery. The 11th and 17th had one regiment each of 3-inch

horse-drawn guns, 4.7-inch motorized howitzers, and 6-inch motorized

howitzers, while the 14th and 20th each had one 3-inch gun regiment

carried on trucks, one regiment of 3-inch horse-drawn guns, and one

regiment of 6-inch motorized howitzers. These artillery units were to be

detached from the divisions and serve as corps artillery, except the

3-inch gun regiment carried on trucks, which was to serve as part of

army artillery.45

As the Army Staff perfected

plans to organize additional Regular Army divisions, steps had been

taken to assure adequate military forces in Hawaii. On 1 June 1918, the

president called the two infantry regiments from the Hawaii National

Guard into federal service, and they replaced units that had transferred

to the United States from Schofield Barracks and Fort Shafter.46

The Philippine Islands also

proved to be a potential source of manpower for fighting World War 1.

When the United States entered the conflict, the Philippine

[65]

Expansion of Divisional

Forces, 1918

| Division |

Component |

Camp |

| 9th |

RA and NA |

Sheridan, Ala. |

| l0th |

RA and NA |

Funston, Kans. |

| 11th |

RA and NA |

Meade, Md. |

| 12th |

RA and NA |

Devens, Mass. |

| 13th |

RA and NA |

Lewis, Wash. |

| 14th |

RA and NA |

Custer, Mich. |

| 15th |

RA and NA |

Logan, Tex. |

| 16th |

RA and NA |

Kearny, Calif |

| 17th |

RA and NA |

Beauregard, La. |

| 18th |

RA and NA |

Travis, Tex. |

| 19th |

RA and NA |

Dodge, Iowa |

| 20th |

RA and NA |

Sevier, S.C. |

| 95th |

NA |

Sherman, Ohio |

| 96th |

NA |

Wadsworth, N.Y. |

| 97th |

NA |

Cody, N.M. |

| 98th |

NA |

McClellan, Ala. |

| 99th |

NA |

Wheeler, Ga. |

| 100th |

NA |

Bowie, Tex. |

| 101st |

NA |

Shelby, Miss. |

| 102d |

NA |

Dix, N.J. |

people offered to raise a

volunteer infantry division to be a part of American forces. The

offer was declined, but Congress authorized federalizing the

Philippine Militia to replace U.S. Army units if necessary. Nine

days after the armistice President Wilson ordered nascent militia

into federal service for training, and the 1st Division, Philippine

National Guard, was organized under the prewar divisional structure.

The division, however, lacked many of its required units, and its

headquarters was mustered out of federal service on 19 December

1918.47

There were also two Regular

Army nondivisional infantry regiments in the Philippine Islands. In

July 1918 they joined an international force for service in Siberia.

To bring the regiments to war strength, 5,000 well-trained

infantrymen from the 8th Division at Camp Fremont, California,

joined the Siberian Expedition.48

In July 1918 Secretary

Baker approved final expansion of divisional forces, which involved

black draftees. The plan required black units to replace sixteen white

pioneer infantry regiments serving in France. These white units were

to be organized into eight infantry brigades and eventually be

assigned to divisions partially raised in the United States. By 11

November the War Department had organized portions of the 95th through

the 102d Divisions in the United States (see Table 5), but the

brigades in France had not been organized.49

[66]

The General Staff had approved

several changes in the August 1917 structure when the Army began to

organize the last group of infantry divisions for World War I. Changes

included reducing the division's reserve machine gun battalion from a

four-company organization to a two-company unit and increasing the

infantry brigade's machine gun battalions from three to four companies.

Although the total number of machine gun units remained the same, the

realignment afforded better command and control within the infantry

brigades. More Signal Corps men were added, and more motorized

ambulances were provided for the sanitary trains. Usually each

modification brought a change in the strength of the division, which by

November 1918 stood at 28,105 officers and enlisted men.50

The demands of combat led to

several changes in divisional weapons. The French agreed to replace all

U.S. 3-inch guns with their 75-mm. guns in exchange for supplies of

ammunition. The 3-inch Stokes mortars, optional weapons in the infantry

regiment, were made permanent. To defend the division against enemy

airplanes, antiaircraft machine guns were authorized in the field

artillery regiments. The most significant change, however, involved

machine guns and automatic rifles. In September 1918 elements of the

79th and 80th Divisions used new machine guns and automatic rifles

invented by John M. Browning. The Browning water-cooled machine gun was

a lighter, more reliable weapon than either the British Vickers or the

French Hotchkiss, and the Browning automatic rifle (BAR) surpassed the

British Lewis and French Chauchat in reliability. New Browning weapons,

however, were not available in sufficient quantities for all divisions

before the end of the war.51

Pershing formally modified the

division staff during the war. In February 1918 he adopted the European

functional staff, which he had been tentatively using since the summer

of 1917. Under that system the staff consisted of five sections: G-1

(personnel), G-2 (intelligence), G-3 (operations), G-4 (supply), and G-5

(training). Each section coordinated all activities within its sphere

and reported directly to the chief of staff, thereby relieving the

commander of many routine details.52

Pershing and his staff also

changed plans for assembling army corps to meet conditions in France.

When four divisions had arrived in France, the 1st, 2d, 26th, and 42d,

the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) staff began planning a corps

replacement and school division. After reviewing the readiness status of

the divisions, the staff recommended that the 42d be reorganized as the

replacement and school unit. Pershing disagreed. For political reasons,

the "Rainbow" Division had to be a combat unit. Also, he did

not agree that the army corps required a replacement and school unit at

that time; he wanted a base and training division to receive and process

replacements. For that job he selected the 41st Division, which had just

begun to arrive in France.53

[67]

Shortly thereafter Pershing

revised the replacement system for the AEF. Instead of relying on a

replacement and school division and a base and training division for

each army corps, he split the replacement function between the army

corps and the "communications zone," the area immediately

behind the battlefield controlled by the "Service of the

Rear." In the communications zone a depot (base and training)

division would process personnel into the theater, while a replacement

(replacement and school) division in each army corps distributed new

personnel to their units. He assigned the 41st Division to the Service

of the Rear (later the Services of Supply) as a depot division, which

was to receive, train, equip, and forward replacements (both officers

and enlisted men) to replacement divisions of the corps, and designated

the 32d Division as the I Army Corps' replacement unit. But when the

German offensive began along the Somme (21 March to 6 April 1918), the

32d Division was assigned to combat duty. To channel replacements from

the depot division to their assigned units, each army corps instead

established a replacement battalion. The depot division processed

casuals into the theater, and the replacement battalions forwarded them

to the units. The 41st served as the depot division for the AEF until

July 1918. No replacement division was organized during World War 1.54

The German offensive on the

Somme upset Pershing's organizational plans. He offered all American

divisions to the French Army. The 1st, 2d, 26th, and 42d Divisions were

sent to various quiet sectors of the line, and they and more recent

arrivals did not come under Pershing's control until late in the summer

of 1918. He also placed the four regiments of the black 93d Division

(Provisional) at the disposal of the French with the understanding that

they would be returned to his control upon request. The French quickly

reorganized and equipped the regiments under their tables of

organization. Although they were to be returned to Pershing's control

after the crisis, they remained with French units until the end of the

war. The headquarters of the provisional 93d Division was discontinued

in May 1918.55

The Army and the nation did not

have enough ships to transport forces to France, and this lack was a

major obstacle to the war effort. After lengthy discussions in early

1918, the British agreed to transport infantry, machine gun, signal, and

engineer units for six divisions in their ships. Upon arrival in France,

these units were to train with the British. The divisional artillery and

trains were to be shipped when space became available, and they were to

train in American training areas. The British executed the program in

the early spring of 1918, eventually moving the 4th, 27th, 28th, 30th,

33d, 35th, 77th, 78th, 80th, and 82d Divisions. By June 1918 the

nation's transport capability had increased markedly. In addition, the

adoption of the convoy system greatly reduced the effect of German

submarines, allowing the number of divisions in France to rise rapidly (Table

6).

56

As more divisions arrived,

Pershing revamped his ideas about the army corps. He made it a command

consisting of a headquarters, corps artillery, technical troops, and

divisions. The divisions and technical troops could be varied for each

specific operation. Under his system, patterned after the French, the

army corps

[68]

165th Infantry, 42d Division, in trenches, June 1918

became a more mobile, flexible

command. The concept also took advantage of the limited number of

American divisions in the theater, shifting them among army corps as

needed. Eventually, Pershing organized seven army corps.

To maintain them, the 39th,

40th, 41st, 76th, 83d, and 85th Divisions served as depot organizations.

The 31st Division was slated to become the seventh depot division but

never acted in that role, having been broken up for needed replacements.

Because depot divisions needed only cadres to operate, most of the

personnel, except for men in the field artillery brigades, were also

distributed to combat divisions as replacements. After additional

training, the field artillery brigades assigned to the 41st, 76th, 83d,

and 85th Divisions saw combat primarily as army corps artillery. Those

assigned to the 39th and 40th were still training when the fighting

ended.57

When the Services of Supply

reorganized the 83d and 85th Divisions as depot units, some of their

elements were used as special expeditionary forces. The 332d Infantry

and 331st Field Hospital, elements of the 83d Division, participated in

the Vittorio Veneto campaign on the Italian front during October and

November 1918. The 339th Infantry; the 1st Battalion, 310th Engineers;

the 337th Ambulance Company; and the 337th Field Hospital of the 85th

constituted the American contingent of the Murmansk Expedition, which

served under British command in North Russia from September 1918 to July

1919.58

[69]

Deployment of Divisions to France

| Division |

Dates of Movement Overseas |

Remarks |

| 1st |

June-December |

1917 |

| 2d |

September 1917-March

1918 |

Organized in France |

| 3d |

March-June 1918 |

|

| 4th |

May June

1918 |

British shipping program |

| 5th |

March-June 1918 |

| 6th |

June-July 1918 |

| 7th |

July-September 1918 |

| 8th |

November

1918 |

Headquarters only |

| 26th |

September 1917-January

1918 |

| 27th |

May-July

1918 |

British shipping program |

| 28th |

April-June

1918 |

British shipping program |

| 29th |

June July 1918 |

| 30th |

May June

1918 |

British shipping program |

| 31st |

September-November

1918 |

Skeletonized |

| 32d |

January-March 1918 |

| 33d |

May-June

1918 |

British shipping program |

| 34th |

September October

1918 |

Skeletonized |

| 35th |

April-June

1918 |

British shipping program |

| 36th |

July-August 1918 |

| 37th |

June-July 1918 |

| 38th |

September-October

1918 |

Skeletonized |

| 39th |

August September

1918 |

Depot, later skeletonized |

| 40th |

July-September

1918 |

Depot |

| 41st |

November 1917-February

1918 |

Depot |

| 42d |

October-December 1917 |

| 76th |

July-August

1918 |

Depot |

| 77th |

March May

1918 |

British shipping program |

| 78th |

May June

1918 |

British shipping program |

| 79th |

July-August 1918 |

| 80th |

May-June

1918 |

British shipping program |

| 81st |

July-August 1918 |

| 82d |

April-July

1918 |

British shipping program |

| 83d |

June August

1918 |

Depot |

| 84th |

August-October

1918 |

Depot, later skeletonized |

| 85th |

July August

1918 |

Depot |

| 86th |

September-October

1918 |

Skeletonized |

| 87th |

June-September

1918 |

Broken up for laborers |

| 88th |

August-September 1918 |

| 89th |

June-July 1918 |

| 90th |

June-July 1918 |

| 91st |

June-July 1918 |

| 92d |

June-July 1918 |

| 93d |

December 1917-April

1918 |

Provisional unit, discontinued

May 1918 |

[70]

Heavy losses during the greatest

American involvement in World War I, the Meuse-Argonne campaign that

began on 26 September 1918, created a need for additional replacements.

One week of combat left divisions so depleted that Pershing ordered

personnel from the 84th and 86th Divisions, which had just arrived in

France, to be used as replacements.59

The arrangement was supposed to be

temporary, and at first only men from infantry and machine gun units

served as replacements. Eventually all divisional personnel were

swallowed up, except for one enlisted man per company and one officer

per regiment who maintained unit records. The manpower shortage

persisted. On 17 October the 31st Division, programmed as the depot

division, was skeletonized and its men used as replacements. The 34th

and 38th Divisions were also stripped of their men as they arrived from

the United States. Nevertheless, the high casualty rate took a toll on

all combat units, and Pershing slashed the authorized strength of

infantry and machine gun companies from 250 to 175 enlisted men, thereby

temporarily reducing each division by 4,000 men. Smaller combat

divisions, however, conducted some of the fiercest fighting of the

war-attacks against the enemy's fortified positions on the hills between

the Argonne Forest and the Meuse River.60

While scrambling for personnel,

Pershing again reorganized the replacement system, trying to improve its

responsiveness to the flexible army corps and army organizations. Army

corps replacement battalions failed because divisions left the corps so

rapidly that the battalions were unable to keep up with them. Therefore,

he ordered the 40th and 85th Divisions to serve as regional replacement

depots for the First and Second Armies, respectively, and the 41st and

83d as depot divisions in the Services of Supply. The other two depot

divisions, the 39th and 76th, were stripped of their personnel. The

replacement system, however, remained unsatisfactory to the end of the

war.61

Divisions in France also

suffered from a shortage of animals for transport. As the quartermaster

general had

predicted in 1917, units never had more than half the

transportation authorized in their tables of organization for lack of

animals. In some divisions artillerymen moved their pieces by hand. To

overcome the shortage, Pershing's staff planned to motorize the 155-mm.

howitzer regiments and one regiment of 75-mm. guns in each division. By

November 1918, however, only eleven 155-mm. howitzer regiments had been

thus equipped.62

Troop shortages also hit support

units. During the fall of 1918 the commander of the Services of Supply,

Maj. Gen. James G. Harbord, requested personnel from three combat

divisions for labor units in his command. On 17 September Pershing's

headquarters reassigned three divisions scheduled to arrive from the

United States to Harbord. Only one of these, the 87th, reported before

the end of the fighting, and it was broken up for laborers in the

Services of Supply.63

Handicapped by the scarcity of

men and animals, Pershing sought ways to make divisions more effective

combat units. In October 1918 he advised new division commanders to use

their personalities to increase the patriotism, morale,

[71]

Traffic congestion in the Argonne, November 1918

and fighting spirit of their

men. One way to develop unit esprit, Pershing suggested, was for

divisions to adopt distinctive cloth shoulder sleeve insignia. At that

time the 81st Division had already begun using such insignia. On his

return to the United States after visiting the Western Front in the fall

of 1917, the division commander, Maj. Gen. Charles J. Bailey, had

authorized a shoulder sleeve insignia for his unit. He instructed the

men not to wear the patch until after leaving the United States. When

the division arrived in France, the insignia came to Pershing's

attention. Bailey explained that no official sanction existed for the

emblem, but that it created comradeship among the men, helped to develop

esprit, and aided in controlling small units in open warfare. Pershing

apparently liked the idea for he ordered all divisions to adopt shoulder

sleeve insignia. Within a short time the other divisions had their own

shoulder patches, many adopting their divisional property symbols. Along

with the insignia, the men began to adopt divisional nicknames, such as

"Big Red One" and "Wildcat" for the 1 stand 81st

Divisions, respectively.64

Combat, particularly in the

Meuse-Argonne campaign, tested the assumptions that lay behind the large

square division. Designed to conduct sustained frontal attacks, not

maneuver, it was thought to possess tremendous firepower and endurance.

The division's firepower, however, proved ineffective. The lack of wire

and the continual movement of infantry units in the offensive hindered

communications between infantry and artillery. In addition, the French

transportation

[72]

network could handle only so

many men, guns, and supplies. Traffic congestion bogged down the

movement of units and also prevented communication. When divisions were

on the line they suffered from the lack of food, ammunition, and other

supplies. Part of the logistical problems also rested with a division's

lack of combat service troops to carry rations, bury the dead, and

evacuate casualties.65

By Armistice Day, 11 November

1918, the Army had fielded 1 cavalry division, 1 provisional infantry

division, and 62 infantry divisions. Of this total, 42 infantry

divisions and the provisional division deployed to Europe (see Table

6),

with one, the 8th Division, not arriving until after the fighting had

ended. On the Western Front in France, 29 divisions (7 Regular Army, 11

National Guard, and 11 National Army) fought in combat. Of the others, 7

served as depot divisions, 2 of which were skeletonized, and 5 were

stripped of their personnel for replacements in combat units, laborers

in rear areas, or expeditionary forces in North Russia or Italy. The

provisional black division was broken up, but its four infantry

regiments saw combat. Starting from a limited mobilization base, this

buildup, lasting eighteen months, was a remarkable achievement.

Despite the difficulties, World

War I brought about more coordination among the combat arms, combat

support, and combat service organizations in the infantry division than

ever before. Infantry could not advance without support from engineers

and artillery; artillery could not continue to fire without a constant

supply of ammunition. Transportation and signal units provided the vital

materiel and command connections, while medical units administered to

the needs of the wounded. This complex type of combined arms unit became

possible because of advances in technology, weapons, communications, and

transportation.

The adoption of the unwieldy

square division, however, proved to be less than satisfactory.

Pershing's staff believed that a division of 28,000 would conserve the

limited supply of trained officers, maximize firepower, and sustain

itself effectively in combat. In practice, the square division lacked

mobility. Its deficiencies became apparent during the important

Meuse-Argonne offensive, when American divisions bogged down and

suffered excessive casualties. The successes and failures of the

infantry division's organization set the stage for a debate that would

surround it for the next twenty years.

[73]

Endnotes

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

page created 29 June 2001

Return to the

Table of Contents

-