Chapter II:

Genesis of Permanent Divisions

Officers who have never seen a

corps, division, or brigade organized and on the march can not be

expected to perform perfectly the duties required of them when war

comes.

At the opening of the twentieth

century, following the hasty organization and deployment of the army

corps during the War with Spain, the Army's leadership realized that it

needed to create permanent combined arms units trained for war.

Accordingly, senior officers worked toward that goal until the nation

entered World War I. Their efforts reflected the principal mission of

the Army at the time: to defend the vast continental United States and

its modest insular empire in the Caribbean Sea and Pacific Ocean. During

this period the infantry division replaced the army corps as the basic

combined arms unit. Growing in size and firepower, it acquired combat

support and service elements, along with an adequate staff, reflecting

visions of a more complex battlefield environment. The cavalry division,

designed to achieve mobility rather than to realize its combined arms

potential, underwent changes similar to those of the infantry division.

Army leaders also searched for ways to maintain permanent divisions that

could take the field on short notice. That effort accomplished little,

however, because of traditional American antipathy toward standing

armies.

The Army began closely examining

its organizations after the War with Spain. The War Department had been

severely criticized for its poor leadership during the 1898

mobilization. Under the guidance of Secretary of War Elihu Root, it

established a board to plan an Army war college that would "direct

the instruction and intellectual exercise of the Army."2

This

concept inspired creation of the General Staff in 1903, which led to

major reforms in Army organization and mobilization.3

Under the leadership of Maj.

Gen. Adna R. Chaffee, the Chief of Staff, the new organization had a

profound influence on the structure of the field army. In 1905 the War

Department published Field Service Regulations, United States Army, in

which Capt. Joseph T. Dickman, a General Staff member and future Third

Army commander, drew together contemporary thought on tactics and

[23]

logistics. Designed for the

first level of officer training within the Army's educational system,

the regulations covered such subjects as orders, combat, services of

information and security (intelligence), subsistence, transportation,

and organization. Under the guidance of Chaffee and other staff officers

Dickman's organizational section directed the formation of provisional

brigades and divisions during field exercises so that smaller permanent

units could train for war.4

With these new ordinances, the

Army departed from national and international practice, and the infantry

division replaced the army corps, which had been used in the Civil War

and the War with Spain, as the basic unit for combining arms. Since the

mid-nineteenth century a typical European army corps had consisted of

two or more divisions, a cavalry brigade, a field artillery regiment,

and supporting units-about 30,000 men. Divisions usually included only

infantry. Although they sometimes had artillery, cavalry, or engineer

troops, they rarely included service units.5

In march formation (infantry in

fours, cavalry in twos, guns and caissons in single file), a European

army corps covered approximately fifteen miles of road, a day's march.

To participate in a battle involving the vanguard, the corps' rear

elements might have a day's march before engaging the enemy. Any greater

distance meant that all corps elements could not work as a unit. In the

continental United States an army corps actually required about

thirty-five miles of road space because of the broken terrain and poor

roads. Within a moving army corps, however, a division occupied only

eleven miles.6

By replacing the army corps with

the division, Dickman's regulation sought an organizational framework

appropriate to the mission and the expected terrain. In 1905 the staff

did not identify specific adversaries, but the planners believed that if

war broke out a divisional organization was more appropriate for use in

North America. Their assumption was that the nation would not be

involved in a war overseas.7

For training, the regulations

outlined a division that included three infantry brigades (two or more

infantry regiments each), a cavalry regiment, an engineer battalion to

facilitate movement, a signal company for communications, and four field

hospitals. Nine field artillery batteries, organized as a provisional

regiment, served both the division and other commands such as corps

artillery. To attain a self-sufficient division, the planners added an

ammunition column, a supply column, and a pack train, all to be manned

by civilians. The regulations did not fix the strength of the

organization, but in march formation it was estimated to use fourteen

miles of road space. That distance represented a day's march,

paralleling the length of a contemporary European army corps.8

In the field, divisions were

both tactical and administrative units. Matters relating to courts

martial, supply, money, property accountability, and administration, all

normally vested in a territorial commander during peace, passed to the

division commander during war. To carry out these duties, the division

was to have a chief of staff, an adjutant general, an inspector general,

a provost marshal,

[24]

a judge advocate, a surgeon, and

a quartermaster, along with commissary, engineer, signal, ordnance, and

muster officers. The senior artillery officer served ex officio as the

chief of the division artillery.9

The cavalry division, also

described in the regulations, consisted of three cavalry brigades (two

or three cavalry regiments each), six horse artillery batteries, mounted

engineer and signal companies, and two field hospitals. Civilians were

to man ammunition and supply columns. Because mounted troops were likely

to be employed in small detachments, the cavalry division had no

prescribed staff. 10

Above the division level, the

regulations only sketched corps and armies. Two or three infantry

divisions made up an army corps, and several army corps, along with one

or more cavalry divisions, formed an army. Specific details regarding

higher command and control were omitted.11

When the Field Service

Regulations were published, General Chaffee harnessed them to training

and readiness. First, he directed the garrison schools to use them as

textbooks, taking precedence over any others then in use. Second, he

applied the regulations to both the Regular Army and the Organized

Militia when in the field. 12

Militia, or National Guard,

units had dual missions. Each served its state of origin but, when

called upon, also served in national emergencies. Under the Dick Act of

1903, National Guard units had five years to achieve the same

organizational standards as the Regular Army units. To accomplish that

goal, the federal government increased the funds for arms and equipment

and annual training and provided additional Regular Army officers to

assist with training. 13

Having an outline for field

organizations and units available to prepare for war, the Army turned

its attention to training. Combined arms training artillery, cavalry, and

infantry-had been a part of the school curriculum at Fort Leavenworth,

Kansas, since 1881, but Secretary Root gave such training added meaning

in 1899 when he noted that officers needed to see a corps, division, or

brigade organized and on the march to perform their duties in war. In

1902 some state and federal units held maneuvers at Camp Root, Kansas, 14

but the first large drill took place two years later near Manassas,

Virginia. At that time Guard units from eighteen states and selected

Regular Army units trained together a total of 26,000 men. Maneuvers on a

lesser scale were held in 1906 and 1908. These biennial maneuvers proved

beneficial to both professional and citizen soldiers. Regulars gained

command experience, and guardsmen refined their military skills. 15

Although periodic maneuvers had

their merits, the General Staff soon realized that they fell short of

preparing the Army for war. In 1906 the Regular Army was still dispersed

among posts that accommodated anywhere from two companies to a regiment.

To provide for more sustained training, the staff urged Secretary of War

William Howard Taft to concentrate the regulars at brigade-size posts.

Taft proved receptive, but most members of Congress opposed the reform,

particularly if closing a post might affect their constituents

adversely. 16

[25]

Public views the 1904 maneuvers, Manassas, Virginia; below, troops

pass in review, 1904 Manassas maneuvers

[26]

Maj. Gen. Henry C. Corbin and

Colonel Wagner

In 1909 Assistant Secretary of

War Robert Shaw Oliver, a veteran with experience as a volunteer,

Regular, and Guard officer, adopted another approach to readiness.

Following the European example of mixing regulars and reserves in the

same formation, he divided the nation into eight districts. Within each

district, Oliver planned to form brigades, divisions, and corps for

training Regular and Guard units. The district commander was to

supervise all assigned regulars, but to exercise only nominal control

over Guard units, which were to be federalized only during a national

emergency or war. Nevertheless, Oliver expected the district commander

to influence the citizen-soldier by manifesting an interest in the

reserve forces. The plan was voluntary for the National Guard, but by

early 1910 the governors of the New England states and New York had

agreed to have their units participate. 17

About the same time this

agreement was reached, the Army modified its field organizations,

retaining divisions but replacing the corps and army commands with a

field army. Since the mid-nineteenth century military theorists had

debated the need for the corps. Col. Arthur L. Wagner, a founding father

of the Army school system, believed that it was a necessary echelon

between division and army, but based on experience during the Civil War

Maj. Gen. Andrew A. Humphreys, former Chief of Staff of the Army of the

Potomac, disagreed. Humphreys wanted a strong division capable of

independent operations, noting that the terrain and poor roads in the

United States prevented the easy maneuver or movement of a large unit.

18

Agreeing with Humphreys, the

General Staff decided that a command made up of divisions, designated as

a field army, best fit the nation's needs. As described in the Field

Service Regulations of 1910, the field army comprised two or more

infantry divisions, plus support troops, which included pioneer infantry

(service troops for the forward area of the battlefield), heavy

artillery, engineers, signal and medical troops, and ammunition and

supply units, which could maneuver and fight independently. Cavalry

might be included in the division if appropriate.19

To fit within the new concept,

the General Staff, in conjunction with the Army School of the Line at

Fort Leavenworth, made the infantry division a

[27]

more powerful and

self-sufficient organization. A field artillery brigade of two regiments

with forty-eight guns replaced the provisional regiment. Infantry and

cavalry regiments benefited from additional firepower. Based on

experiments with machine guns in 1906, a provisional two-gun platoon had

been added to each infantry and cavalry regiment, and with the new

regulations the authorization was increased to six guns. Depending on

range, one machine gun equaled the firepower of between sixteen and

thirty-nine riflemen. Thus, divisional firepower grew substantially.

Other changes improved communications by replacing the signal company

with a two-company battalion and expanded the medical service by adding

four ambulance companies. For the first time, a directive fixed the

strength of a division at 19,850 men-740 officers, 18,533 enlisted, and

577 civilians, the last serving mostly in the ammunition and supply

units. Transport for a division included 769 wagons and carts, 48

ambulances, and 8,265 animals.20

While making the division more

powerful, the regulations realigned the division staff. The new staff

consisted of a chief of staff, an adjutant general, an inspector

general, a judge advocate, a quartermaster, a commissary officer, a

surgeon, the commander's three aides, and six civilian clerks. Engineer

and signal battalion commanders joined it at the discretion of the

division commander. The provost marshal was eliminated, as were the

ordnance, muster, and senior artillery officers, with most of these

positions moving to the field army headquarters.21

A new nomenclature for divisions

indicated their self-sufficiency. Instead of being numbered as the 1st,

2d, and 3d Divisions, I Army Corps, as during the Civil War and the War

with Spain, units were to be numbered consecutively in the order of

their formation. No reference to any field army appeared in divisional designations. As before, brigades were identified only as the 1st, 2d,

and 3d brigades of a division.22

The new ordinances also included

a 13,836-man cavalry division in the field army, and, as in the infantry

division, internal changes affected firepower, logistics, and staff. A

field artillery regiment replaced the six batteries, and each cavalry

regiment fielded a provisional machine gun troop. The engineer and

signal companies were expanded to battalions, and two ambulance

companies were added. A pack train completed the division. For the first

time, the cavalry division was given a staff similar to that in the

infantry division. Designations of cavalry divisions were also to be

numerical and consecutive in the order of their organization.23

Maj. Gen. James Franklin Bell,

the Chief of Staff of the Army, established the First Field Army on 28

February 1910. Although merely a paper organization before mobilization,

it consisted of three infantry divisions, each with three infantry

brigades. Each infantry brigade comprised three infantry regiments, and

the other divisional units included a cavalry regiment, an engineer

battalion, and medical and signal units. In place of the field artillery

brigade, each division had only one field artillery regiment. Because

the artillery and cavalry regiments

[28]

General Bell

were made up of both Regular

Army and National Guard elements, Bell designated them as

"National" regiments. The supply and ammunition trains, manned

by civilians, were to be formed after mobilization.24

Within a few months the new

Chief of Staff, Maj. Gen. Leonard Wood, reported to Secretary of War

Jacob M. Dickinson that the First Field Army existed in name only.

Noting that the Army lacked the required units and equipment to field

the organization, he nevertheless believed that the War Department had

taken the first step in organizing the Regular Army and the National

Guard for modern war.25

Not everyone in the War

Department agreed with the concept of the First Field Army. The Chief of

the Division of Militia Affairs, Brig. Gen. Robert K. Evans, recommended

that General Wood revoke the orders establishing the organization for

two reasons. First, the field army did not fit any plan for the national

defense, and, second, he believed that Regular and Guard units did not

belong in the same formation. He further contended that the orders

implied the existence of a field army. Events along the Mexican border

soon caused the Army to abandon the organization, and eventually the

secretary of war rescinded the orders.26

In March 1911, during disorders

resulting from the Mexican Revolution, the War Department deployed many

Regular Army units of the First Field Army to the southern border. Units

assembled at San Antonio, Texas, constituted the Maneuver Division and

the Independent Cavalry Brigade, while others, concentrated at

Galveston, Texas, and San Diego, California, made up separate infantry

brigades. The division, following the Field Service Regulations outline,

consisted of three infantry brigades, a field artillery brigade, an

engineer battalion, and medical and signal units, but no trains.

Thirty-six companies from the Coast Artillery Corps, organized as three

provisional infantry regiments, comprised the brigade at Galveston. The

brigade at San Diego had two infantry regiments and

small medical, signal, and

cavalry units, along with a provisional quartermaster (bakers and cooks)

unit. The Galveston and San Diego brigades were intended to defend

against possible attack by the Mexican Navy, while the Maneuver Division

readied for offensive operations against Mexico.27

The Army experienced great

difficulty with this assembly of troops. Scores of movement orders had

to be issued, and inadequate arrangements for transportation caused

innumerable delays. Upon arriving at their new stations, the units found

themselves considerably under strength. The division initially had about

8,000 officers and enlisted men but, with the addition of recruits, its

strength climbed to 12,809. That total represented only about two-thirds

of the authorized strength outlined in the regulations for the division.

Although the division impressed some American citizens, General Wood's

comment was "How little.."28

During the concentration of

troops along the border, which lasted for almost five months, the Army

learned many lessons about readiness. The foremost one concerned the

effects of the lack of a mobilization plan, which caused delays in

notifying and transporting units. Sixteen days were required to assemble

the small force. By comparison, the following year the Bulgarians needed

only eighteen days to mobilize 270,000 men against the Turks. After the

troops arrived at the mobilization sites, the division's inspector

general found many problems. No two units had the same tentage,

transportation equipment, or quartermaster supplies. The large numbers

of recruits overwhelmed the units and caused general confusion. Medical

units performed poorly since they had been haphazardly organized.29

To correct these faults, the

inspector general recommended that standard field equipment be issued to

all units, that their peacetime strength be increased, and that

permanent field hospitals and ambulance companies be maintained.

Logistical problems stemmed from the lack of regulatory civilians in the

ammunition and supply trains. But rather than urging the organization of

those units, the inspector suggested that the Army experiment with

"autotrucks."30

In the communications arena, the

Signal Corps tested the telegraph, wireless telegraph (radio), and the

airplane during tactical exercises. Cavalry employed the wireless

telegraph, while infantry used telegraph wire, and both reported great

success. In addition to training officers to fly, the airplane was used

for reconnaissance in the division, which spurred further aeronautical

development.31

When the Maneuver Division and

the brigades were mobilized, General Wood expected that they could

remain on the border for three months without asking Congress for

additional money. He succeeded. The brigades at Galveston and San Diego

were discontinued in June 1911, and divisional elements began returning

to their home stations at the end of July. On 7 August the division

headquarters passed into history.32

The mobilization served many

purposes, not the least of which was to give impetus to General Wood's

preparedness campaign. The performance of the division and the brigades

illustrated the nation's unpreparedness for war.

[30]

After the breakup of the

division and brigades, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson requested the

General Staff to review national defense policies and to develop a

mobilization plan for the Army. Maj. William Lassiter, Capt. John

McAuley Palmer, and Capt. George Van Horn Moseley prepared the

recommendations submitted to Stimson in 1912 as the Report on the

Organization of Land Forces of the United States.33

Known as the Stimson

Plan, it set out the need for "A regular army organized in

divisions and cavalry brigades ready for immediate use as an

expeditionary force or for other purposes . . . ." Behind it was to

be "an army of national citizen soldiers organized in peace in

complete divisions and prepared to reenforce the Regular Army in time of

war." Finally, the plan called for "an army of volunteers to

be organized under prearranged plans when greater forces are required

than can be furnished by the Regular Army and the organized citizen

soldiery." 34

Although the Stimson Plan

received support throughout the Army and the nation, changing the

military establishment proved difficult. Congress balked at altering the

laws governing the Army. The General Staff therefore opted to improve

readiness by implementing as many of the recommendations as possible on

the basis of existing legislation. After conferences with general

officers, the National Guard, and concerned congressional members,

sixteen divisions emerged as a mobilization force. The Regular Army was

to furnish one cavalry and three infantry divisions, and the National

Guard twelve infantry divisions. With these goals established, the staff

developed plans to reorganize the two components. 35

On 15 February 1913, Stimson

announced his new arrangement for the Regular Army. To administer it, he

divided the nation into Eastern, Central, Western, and Southern

Departments and created northern and southern Atlantic coast artillery

districts, along with a third for the Pacific coast. These departments

and districts provided the framework for continued command and control

regardless of the units assigned to them. Second, he arranged to

mobilize field units into divisions and brigades. The 1st, 2d, and 3d

Divisions were allotted to the Eastern, Central, and Western

Departments, respectively, and the Cavalry Division (1st and 2d Cavalry

Brigades) to the Southern Department. The 3d Cavalry Brigade, a

nondivisional unit, was assigned to the Central Department. When

necessary, two regiments in the Eastern Department were to combine to

form the 4th Cavalry Brigade. The plan addressed primarily the defense

of the continental United States, but also included the territory of

Hawaii. The three infantry regiments stationed in the islands were to

form the 1st Hawaiian Brigade. 36

These arrangements fell short of

perfection. Divisional components remained scattered until mobilization,

thereby precluding continuous training. For example, the 1st Division's

elements occupied fourteen posts. All divisions lacked units prescribed

in the Field Service Regulations. Stimson, however, hoped that Congress

would eventually authorize completion of the units.37

[31]

To organize the National Guard

divisions, Stimson had to gain the cooperation of state governors who

controlled the Guard units until federalized. Captain Moseley devised a

system to divide the nation into twelve geographic districts, each with

an infantry division. Thirty-two states accepted the scheme, two states

remained noncommittal, and fifteen refused comment. Although the staff

failed to gain unanimous support of its proposal, in 1914 it adopted the

twelve-division force for the Guard (Table 1), to which was added three

multidistrict cavalry divisions. 38

Implementation of the plan moved

slowly in the states. Governors hesitated to form certain units needed

in the divisions, particularly expensive field artillery and medical

organizations that did not support the Guard's state missions. The staff

likewise moved slowly in developing procedures to instruct, supply, and

mobilize the units. One bright area, the District of New York, which had

maintained a division of its own design since 1908, quickly completed

its part of the plan, perhaps because the state had been a pillar of

support for the preparedness movement. Pennsylvania, the other state

constituting a divisional district, which had supported a nonregulation

division since 1879, gradually began to adjust its organization.

Progress in the multistate districts, not unexpectedly, fell behind

Pennsylvania.39

As it developed plans for the

tactical reorganization of the Army, the General Staff pioneered the

creation of tables of organization for all types of units. Forerunners

of those used today, the tables brought together for easy comparison a

mass of information about unit personnel and equipment previously buried

in

National Guard Infantry Divisions, 1914

| Division |

District |

| 5th |

Maine, New Hampshire,

Massachusetts, Vermont,

Rhode Island, and Connecticut |

| 6th |

New York |

| 7th |

Pennsylvania |

| 8th |

Delaware, New Jersey,

Maryland, District of Columbia, Virginia, and West Virginia |

| 9th |

North Carolina, South

Carolina, Florida, and Georgia |

| 10th |

Alabama, Mississippi,

Tennessee, and Kentucky |

| 11th |

Michigan and Ohio |

| 12th |

Illinois and Indiana |

| 13th |

Wisconsin, Minnesota, North

Dakota, South Dakota, and Iowa |

| 14th |

Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska,

Colorado, and Wyoming |

| 15th |

Arkansas, Arizona, New

Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, and Louisiana |

| 16th |

California, Oregon,

Montana, Utah, Idaho, Nevada, and Washington |

[32]

various War Department

publications, greatly easing the task of determining requirements for

mobilizations. Although the new tables did not alter the basic combat

triad structure of the infantry division, their formulation was

accompanied by internal changes in the infantry regiments and the

divisional support echelon. Revisions eliminated the pack train,

authorized a small engineer train, and manned the engineer, supply, and

ammunition trains with military personnel instead of civilians.40

In 1912 Congress created a

service corps within the Quartermaster Corps to replace civilian

employees and soldiers detailed from combat units for duty as

wagonmasters, teamsters, blacksmiths, and other such laborers and

artificers. Only nineteen civilians-veterinarians and clerks-remained in

the division. For the first time, sources for military police and train

guards were specified. Traditionally, commanders gave regiments or

battalions that had suffered severely in battle the honor of serving as

provost guards, especially those that had conducted themselves with

distinction.41

In the infantry regiment,

besides the provisional machine gun company provided for in 1910,

provisional headquarters and supply companies were to provide mounted

orderlies and regimental wagon drivers. The arrangement eliminated the

need to detail men from rifle companies, a practice that had plagued

unit commanders since the Revolutionary War. These and other changes

raised the division's strength to 22,646 officers and enlisted men and

19 civilians.42

The place of possible employment

continued to influence the division's basic structure. Before the tables

of organization were prepared, the staff debated whether a division

should have two or three infantry brigades, noting that European armies

continued to use a two-division corps organization. Maj. Nathaniel E

McClure, appointed as an instructor in military art at the Army Service

Schools, Fort Leavenworth, in 1913, attributed the European organization

to economy in the use of personnel and to the proper use of

sophisticated road networks. He concluded, however, that what the

Europeans really wanted was a corps built upon multiples of

three-regiments, brigades, and divisions. When preparing the Stimson

Plan, the officers determined that a division with two infantry brigades

limited the commander's ability to subdivide his forces for frontal and

flank attacks while at the same time attempting to maintain a reserve.

Along with ease of command, deployment on a road influenced the

decision. Because a division containing two infantry brigades would make

less economical use of road space than one of three brigades, the

three-brigade division remained the Army's basis for combining arms. In

march formation, it measured about fifteen miles.43

The revision of the cavalry

division in many ways paralleled that of the infantry division. Military

personnel manned ammunition and supply trains, and troopers from the

cavalry regiments served as military police and train guards. Each

cavalry regiment was authorized provisional headquarters and machine gun

troops similar to those in the infantry regiment. The most significant

change was in the division's three cavalry brigades, with each being

reduced from three to

[33]

two regiments since three

cavalry regiments in a brigade required too much road space. The

division's strength stood at 10,161, approximately 4,000 fewer men than

the 1910 unit.44

To complement the 1914 tables of

organization, Maj. James A. Logan revised the 1910 Field Service

Regulations. The new edition emphasized the division as the basic

organization for conducting offensive operations in a mobile army. Logan

defined the division as "A self-contained unit made up of all

necessary arms and services, and complete in itself with every

requirement for independent action incident to its operations."45

His definition became the customary description of a division.

The Mexican border remained a

troubled area. Following the mobilization of 1911, the Army patrolled

the frontier with small units, but when insurrectionists overthrew the

Mexican government in 1913, President Taft decided on a show of force

similar to the earlier concentration of troops. On 21 February he

ordered Maj. Gen. William H. Carter, commander of the Central

Department, to assemble the most fully manned of the Army's divisions,

the 2d, on the Gulf coast of Texas. Unlike its mobilization of the

Maneuver Division in 1911, the War Department used a mere five-line

telegram to deploy the unit. Carter, who arrived with his staff in Texas

within three days, established the division headquarters and its 4th and

6th Brigades at Texas City and the 5th Brigade at Galveston. The

division lacked, however, some field artillery, medical, signal, and

engineer elements and all its trains.46

Tension remained high between

the United States and Mexico in 1914, and in response President Woodrow

Wilson adjusted the deployment of military units to protect American

interests. United States naval forces occupied Vera Cruz, Mexico, and

soldiers soon relieved the sailors ashore. On 30 April the 5th Brigade,

2d Division, augmented with cavalry, field artillery, engineer, signal,

bakery, and aviation units, and almost the entire divisional staff took

up positions in the city. To placate uneasy United States citizens along

the border, the 2d and 8th Brigades, elements of the 1st and 3d

Divisions, and some smaller units moved to the southern frontier. In

November the crisis at Vera Cruz ended and the 5th Brigade returned to

Galveston, but activity resumed the following month when the 6th

Brigade, 2d Division, deployed to Naco, Arizona. For the next few months

no major changes took place in the disposition of forces. Then, in

August 1915, a hurricane hit Texas City and Galveston, killing thirteen

enlisted men and causing considerable damage to the 2d Division's

property. Officials in Washington decided that the division was no

longer needed there and ordered its units moved to other posts in the

Southern Department. The divisional headquarters was demobilized on 18

October 1915.47

Before the Vera Cruz expedition,

General Carter had evaluated the 2d

[34]

27th Infantry, 2d Division, encampment, Texas City, Texas

Division. Although he found no

glaring deficiencies in the unit, he recommended the maintenance of

permanent headquarters detachments for divisions and brigades in

peacetime to ease mobilization and to prevent the breakup of regimental

organizations for division details. Carter also recommended that all

communications equipment be centralized in the signal unit because the

training of men assigned to combat arms units to operate signal gear

seemed wasteful.48

On 9 March 1916, trouble flared

again on the southern border when Mexican bandits raided Columbus, New

Mexico, killing and wounding several soldiers and civilians. The

following day the Southern Department commander, Maj. Gen. Frederick

Funston, ordered Brig. Gen. John J. Pershing, commander of the 8th

Brigade, to apprehend the perpetrators. For his mission Pershing

organized a provisional division and designated it as the Punitive

Expedition, United States Army.49

This division differed

considerably from the organizations outlined in the Field Service

Regulations. It consisted of two provisional cavalry brigades (two

cavalry regiments and a field artillery battery each) and one infantry

brigade (two regiments and two engineer companies), with medical,

signal, transportation, and air units as divisional troops. The design

of the division followed the organizational axiom that it adapt to the

terrain and roads where the enemy was located. In hostile and barren

northern Mexico, Pershing planned to pursue the bandits with cavalry and

to protect his communication lines with infantry.50

[35]

4th South Dakota Infantry on the Mexican border, 1916

Violence intensified along the

border during the spring of 1916, causing a general mobilization. After

a raid in May at Glen Springs, Texas, President Wilson called the

National Guard of Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas into federal service.

Following another raid on 16 June, he federalized all Guard units

assigned to tactical divisions designated in the Stimson Plan.51

This final call exposed flaws in

the nation's war plans. In some states mobilization locations were

inaccessible, quartermaster supplies were insufficient, and even

required forms were in short supply. Guard units were under strength and

poorly trained. Some men failed to honor their enlistments, while others

who were physically unfit entered the service. Besides these and other

deficiencies, the need to have troops on the border meant that only two

divisions, the 6th from New York and the 7th from Pennsylvania,

mobilized in accordance with the Stimson Plan. On 4 August the War

Department directed General Funston to organize ten divisions and six

brigades provisionally from the remaining Guard units. But not all of

these organizations could be formed because of the rapid shifting of

units to and from the border. Although the mobilization pointed out many

weaknesses in the nation's preparation for war, it provided an

invaluable training opportunity for the Guard.52

The Punitive Expedition stayed

in Mexico until February 1917. When hostile acts had abated along the

border during the fall of 1916, the War Department had begun to

demobilize the Guard. By the end of March most units had returned to

state control. Pershing, the new Southern Department commander following

[36]

Funston's sudden death from a

heart attack in February 1917, realigned the Regular Army forces. He

organized provisionally a cavalry brigade and three infantry divisions,

but they existed for less than three months. With the nation's entry

into World War I and the need for troops in Europe, Pershing's divisions

were disbanded. Smaller units, however, continued border surveillance.53

While the Army concentrated most

of its regulars in the United States on the Mexican border in 1915, the

ongoing war in Europe prompted Secretary of War Lindley M. Garrison to

reexamine national defense policies. Among other matters, he asked the

General Staff to investigate the organizations and strength figures

needed by the Regular Army and National Guard, the reserve forces

required, and the relationship of the regulars and guardsmen to a

volunteer force. Garrison held the opinion that the federal government's

lack of control over the National Guard was a fundamental defect.54

Members of the General Staff

worked for six months to answer Garrison, and the War Department

published their findings as the Statement of Proper Military Policy in

1915. It outlined a 281,000-man Regular Army and a 500,000-man federal

reserve. An additional 500,000 reserve force was to buttress the

reserves. Under the new policy the National Guard was downgraded to a

volunteer contingent force that would be used only during war.55

Proposed legislation based on

the policy statement, which was dubbed the "Continental Army"

plan, quickly ran into congressional opponents who were unwilling to

abandon the National Guard. But the debate led eventually to the

National Defense Act of 1916. The new act provided that the "Army

of the United States" would consist of the Regular Army, the

Volunteer Army, the Officers' Reserve Corps, the Enlisted Reserve Corps,

the National Guard in the service of the United States, and such other

land forces as were or might be authorized by Congress. The president

was to determine both the number and type of National Guard units that

each state would maintain. Both the Regular Army and the National Guard

were to be organized, insofar as practicable, into permanent brigades

and divisions. Command echelons above divisions reverted to army corps

and armies, the traditional command system; no mention was made of

independent field armies directly controlling divisions. Undoubtedly the

war in Europe, which involved large armies, caused the staff to revert

to that system. To resolve the long-standing question of whether Guard

units could be used outside the United States, the law empowered the

president to draft units into federal service under certain conditions.

Men in drafted units would be discharged from state service and become

federal troops subject to employment wherever needed. Congress continued

to dictate regimental organizations. 56

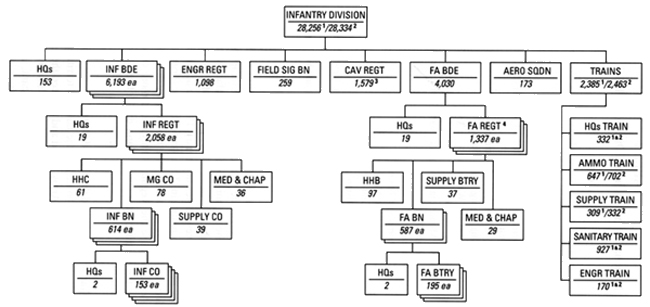

The War Department published new

tables of organization for infantry and cavalry divisions in May 1917.

The structure of the infantry division remained

[37]

similar to that mandated in

1914. Internal changes dealt with firepower, another consequence of

observing the pattern of the European war. Infantry regiments gained

additional riflemen, and the provisional headquarters, supply, and

machine gun companies were made permanent. The field artillery brigade

also gained considerable firepower, with one regiment of 3.8-inch

howitzers and two regiments of 3-inch guns replacing the two regiments

authorized in 1914. A two-battalion engineer regiment replaced the

battalion, the signal battalion grew in size, and an aero squadron

equipped with twelve aircraft joined the division for reconnaissance and

observation. Enlarged ammunition, supply, engineer, and sanitary trains

supported the arms, and the tables provided for the trains to be either

motorized or horse-drawn. The tables also called for a headquarters

troop for the division and headquarters detachments for infantry and

artillery brigades. These units were to furnish mess, transport, and

administrative support for the division to operate on a more complex

battlefield. The redesigned division for war numbered 28,256 officers

and enlisted men when the trains were authorized wagons or 28,334 when

they were authorized motorized equipment (Chart 1).57

The staff, in rationalizing the

division, divided the road space it would use between combat and support

elements. Combat elements used fourteen miles, while the support

elements, depending on whether the trains were motorized or horse-drawn,

used five to six miles. Although it required about twenty miles in march

formation, a 25 percent increase in road space over the 1914

organization, the division was still thought to be able to move to

battle on a single road.58

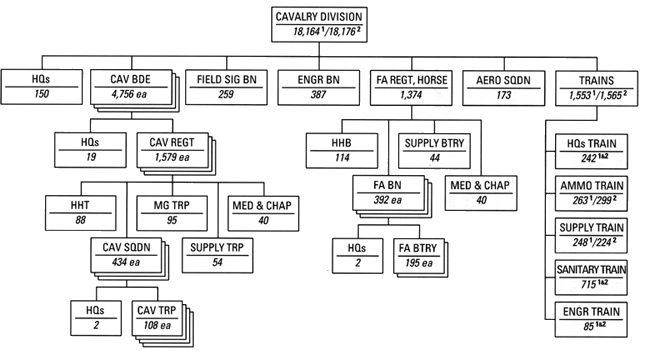

The new tables dramatically

changed the structure of the cavalry division for war. Cavalry brigades

reverted to three regiments each, and the nine cavalry regiments

acquired permanent headquarters, supply, and machine gun troops. As in

the infantry division, the cavalry division fielded an aero squadron.

The tables also introduced a divisional engineer train and enlarged the

ammunition, supply, and sanitary trains. The division headquarters and

headquarters troop and brigade headquarters and headquarters detachments

rounded out the unit. Given these changes, the size of the division rose

from 10,161 to 18,164 when the trains were equipped with wagons and

18,176 when they were equipped with motorized vehicles (Chart 2), and it

occupied approximately

nineteen miles of road space on the

march.59

To achieve the mobilization

force that the Statement of Proper Military Policy proposed-six cavalry

brigades, two cavalry divisions, and twenty infantry divisions-the Army

needed more troops. In 1916 Congress increased the number of Regular

Army regiments to 118 (7 engineer, 21 field artillery, 25 cavalry, and

65 infantry) and increased the size of the National Guard, 800 men for

each senator and representative, to be raised over the next five years.

Several developments, however, interfered with implementation of the

Regular Army portion of the act, especially activities along the Mexican

border, a reduction in the General Staff that prevented appropriate

planning, and the nation's plunge into the European war.60

[38]

Infantry Division, 1917

1 Division trains equipped with wagons

2 Division trains equipped with motorized vehicles

3 Chart 2, Cavalry Division, 1917, depicts the structure of the

Cavalry Regiment

4 Contains two 3" gun regiments and one 3.8" howitzer

regiment

[39]

National Guard Infantry

Divisions, 1917

| Division |

District |

| 5th |

Maine, New Hampshire,

Massachusetts, Connecticut, Vermont, and Rhode Island |

| 6th |

New York |

| 7th |

Pennsylvania |

| 8th |

New Jersey, Delaware,

District of Columbia, Maryland, and Virginia |

| 9th |

North Carolina, South

Carolina, and Tennessee |

| 10th |

Alabama, Georgia, and

Florida |

| 11th |

Michigan and Wisconsin |

| 12th |

Illinois |

| 13th |

Iowa, Minnesota, Nebraska,

North Dakota, and South Dakota |

| 14th |

Kansas and Missouri |

| 15th |

Oklahoma and Texas |

| 16th |

Ohio and West Virginia |

| 17th |

Indiana and Kentucky |

| 18th |

Arkansas, Louisiana, and

Mississippi |

| 19th |

Arizona, California,

Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah |

| 20th |

Idaho, Montana, Oregon,

Washington, and Wyoming |

Meanwhile the Militia Bureau,

formerly the Division of Militia Affairs, began work on new plans to

organize Guard divisions. It scrapped the voluntary Stimson Plan and

directed the organization of sixteen infantry and two cavalry divisions.

Brig. Gen. William A. Mann, Chief of the Militia Bureau, sent the states

advance copies of the new tables in January 1917 to acquaint them with

the types of units they needed to maintain. Then on 5 May he forwarded

the plan for organizing the divisions (Table 2), which gave the infantry

divisions priority over the cavalry divisions. Because the Regular Army

could more expeditiously organize new units for the existing emergency,

Mann did not ask the states to raise any units at that time.61

Between the War with Spain and

the United States' intervention in World War I, the Army's principal

mission was to defend the national territory and its insular

possessions. During this period the Army tested and adopted the infantry

division as its basic combined arms unit. The underlying planning

assumption was that the infantry division would fight in the United

States. This meant, in turn, that one of the principal determinants of a

division's size was road-marching speed. The cav-

[40]

Cavalry Division,1917

1 Division trains equipped with wagons

2 Division trains equipped with motorized vehicles

[41]

alry division, although not

neglected, remained more or less a theoretical unit. As the Army

mobilized for the Mexican border crisis and took note of trends in

foreign armies during the initial campaigns of World War I, its leaders

became increasingly convinced of the need to create permanent tactical

divisions. Congress approved them in 1916, but the nation entered World

War I before these plans had been perfected.

Events during the next two

years, however, profoundly affected divisional organizations, the

infantry division in particular. For the first time in the nation's

experience, the United States Army mobilized a huge expeditionary force

to fight overseas in Western Europe, a mission for which it was

thoroughly unprepared. The day of the old constabulary army was over.

Faced with threats to national security of hitherto unimagined scope

emanating from the Old World, the nation had to revolutionize its army

to wage war against a formidable continental opponent. The necessity for

an effective combined arms organization would force extraordinary

changes in its entire structure.

[42[

Endnotes

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

page created 29 June 2001

Return to the

Table of Contents

-