Chapter X:

Project 80: The End of a Tradition

At Secretary Stahr's request

General Decker appointed a General Staff committee under the Comptroller

of the Army, Lt. Gen. David W. Traub, to study the Hoelscher Committee

report and recommend what action the Army should take. The Office of the

Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics, Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff

for Military Operations, and Office of the Chief of Research and

Development (OCRD) were directed to prepare supporting studies with

recommendations on the internal organization of the proposed logistics,

training, and combat development commands.1

At the same time Secretary

Stahr forwarded the report to Secretary McNamara notifying him that the

Traub Committee would probably take three or four weeks to make any

recommendations but that it was "better to be right than

rapid." While he welcomed suggestions from Mr. Vance and would

supply him with whatever information he wanted in accordance with

Secretary McNamara's instructions, he firmly believed that as Secretary

of the Army he should retain the initiative in Project 80 until he had

submitted his recommendations.2

Instead Secretary McNamara

seized the initiative. At the end of October he told Secretary Stahr he

wanted more details on the internal organization of the new commands,

especially the logistics command. The lack of clear-cut assignment of

responsibility for requirements, procurement, and supply particularly

bothered him.3

[344]

For the Hoelscher Committee

veterans, Project 80 soon became a series of frenzied crash actions in

response to a continuing barrage of detailed questions from Secretary

McNamara and Mr. Vance, such as should there be four, five, seven, or

ten subordinate commands within the logistics command? How many people

would be assigned the new commands and where would they come from? What

major steps were required in changing over from the old to the new

organization? What were the pros and cons of alternative proposals for

grouping the various commodity commands and the functional supply

command? Secretary McNamara also wanted detailed organization charts for

each of the new commands showing where they would come from.4

Secretary McNamara and Mr. Vance

bypassed the Traub Committee and worked directly with the harried band

of Project 80 veterans under Col. Edward W. McGregor. General Illig's

office in DCSLOG and the office of Lt. Col. Wilson R. Reed, Deputy

Director for Plans and Management in OCRD, provided expert assistance in

rushing through one organization chart after another. These Colonel

McGregor personally carried from one office to another for approval and

finally to Mr. Vance's office.

This disregard for traditional

staff procedures dismayed the Army staff. The Traub Committee could not

keep up with the rapidity of Secretary McNamara's requests and

decisions. A disagreement between DCSLOG and OCRD over the internal

organization of the logistics command proved very embarrassing when it

went directly to Secretary McNamara. Under Secretary Stephen Ailes

directed General Traub to "insure that everything that goes

forward, to OSD from now on out in fact represents an Army position as

decided by the Undersecretary or other proper authority." Finally

on 28 November Mr. Ailes was able to recommend creating five subordinate

commodity commands under the logistics command: missiles, munitions

(including chemical, biological, and radiological material), weapons and

mobility, communications and electronics, and

[345]

general equipment (formerly

Quartermaster and Engineer functions). Secretary McNamara approved this

disposition without further changes.5

Similar procedures were followed

in developing the internal organization of the Combat Developments

Command.

While Secretary McNamara was

principally interested in Army logistics, the Traub Committee worked on

training and Army headquarters organization. These were also the major

areas where the final decisions made departed substantially from the

Hoelscher Committee recommendations. At the insistence of the Deputy

Chief of Staff for Personnel, Lt. Gen. Russell L. Vittrup, the Traub

Committee deliberately avoided the area of personnel management on the

grounds that this function should be dealt with by DCSPER. The only

substantive comment the Traub Committee made was that OPO begin

operations by simply taking over in place the personnel management

staffs of the technical services pending physical consolidation when

space became available in the Pentagon. There were no organization

charts or annexes on OPO's internal structure. Neither its functions nor

its relations with DCSPER and the rest of the Army were clearly defined.6

The Traub Committee rejected the

principal Hoelscher Committee recommendations on Army headquarters

except for agreeing that OPO should be an additional Army staff agency.

Its members were unanimous in opposing a Director of the Army Staff as

unnecessary.7

They objected to the Hoelscher Committee's recommendation

for splitting DCSOPS into one agency for joint planning and military

operations and a separate one for training and programs. Neither the

Vice Chief of Staff, General Clyde D. Eddleman, nor the Deputy

Chief of Staff for

[346]

Military Operations, Lt. Gen.

Barksdale Hamlett, saw any need for a separate Deputy Chief of Staff for

Plans, Programs, and Systems. Instead the committee recommended creating

a new post of Director of Army Programs within the Chief of Staff's

secretariat who would be responsible for co-ordinating plans, programs,

and systems within the Army staff itself. It rejected the proposal for a

new Chief of Administrative Services and the abolition of The Adjutant

General's Office. On the other hand it accepted the Hoelscher Committee

proposal to abolish the Office, Chief of Military History, assigning its

functions to TAGO.

To reduce the number of separate

agencies reporting to the Chief of Staff directly, the committee

proposed to group the special staff, except for the Chief of

Information, the Inspector General, and the Judge Advocate General's

Office, under the existing Deputy Chiefs of Staff, including the

vestigial technical and administrative services. Finally the Traub

Committee ignored recommendations concerning improved management and

co-ordination of the Army's plans, programs, and systems and for

streamlining Army staff procedures.8

Concerning training, the Traub

Committee, following recommendations from DCSOPS and CONARC, recommended

making "individual training" a directorate within CONARC

headquarters under a Deputy Commanding General for Training instead of

creating a separate command. The training centers would in this case

continue to remain under the several CONUS armies.9

In accepting the Hoelscher

Committee proposals for a Combat Developments Agency which it designated

as a field command, the Traub Committee recommended expanding its

functions. It suggested transferring from the Army's school system those

functions and personnel connected with the development of doctrine,

preparation of tables of organization and equipment, and combat

developments field manuals. Within the schools these functions were

often assigned to individuals whose main responsibilities were for

training ox teaching and who neglected combat developments as a consequence.10

[347]

Considering the magnitude of the

proposed reorganization the Traub Committee thought eighteen months

would be a highly optimistic estimate for an operation involving nearly

200,000 people and nearly two hundred installations. There would be

three phases: planning, activation, and adjustment. While it might take

only three months to reorganize Army headquarters and the Office of

Personnel Operations, it might take ten months to set up the Combat

Developments Command headquarters. Another factor determining how long

it would take to complete the reorganization was the location of the new

commands. To avoid losing key technical service personnel, the committee

thought the logistics command should be headquartered in the Washington

area where the people were.11

The Traub Committee recommended

assigning "General Staff responsibility" for planning and co-ordinating

the actual reorganization to the Comptroller of the Army, General Traub.

To assist him it recommended creating a special "project

office" within the Office of the Comptroller to "maintain

current information on the progress of the planning or execution as

appropriate" of the reorganization and to serve as "the focal

point for all coordination, periodic reports, and information required

prior to and during the transition." Other Army staff agencies

should "assist" as required.12

After approving the Hoelscher

Committee report, as amended by the Traub Committee and himself,

Secretary McNamara sought the support of General Maxwell D. Taylor, then

President Kennedy's military adviser. A formal briefing for him by Mr.

Hoelscher and the Department of the Army Reorganization Project Office (DARPO)

staff was arranged for 22 November 1961.

General Taylor had earlier told

members of the Hoelscher Committee personally that he considered the

Army's mission was to support the fighting man and that everything

should be subordinated to this goal. Mere change for its own sake was

[348]

wrong because any organization

the size of the Army required stability to function effectively. This

comment represented the position of combat arms officers generally. He

might organize the services along functional lines, were he starting

from scratch. But, considering Army traditions and the large number of

people accustomed to them and to the existing system, he questioned

whether any drastic changes were really desirable such as a major

overhaul of the technical services.13

At his Thanksgiving DARPO

briefing General Taylor repeated these ideas, again emphasizing the

importance and value of Army traditions for Army morale. The proposal to

eliminate the technical services was not new, and he wryly wished the

committee good luck in its venture.

While impressed with the

thoroughness of the Hoelscher Committee report, he wanted further

details on Army logistics under the current organization as well as the

proposed future organization. Taylor also asked for more details on

personnel management and training, the impact of the Combat Developments

Command on the combat arms, and the effect of the reorganization on the

Army's "combat readiness." Last he wanted to know the views of

the technical service chiefs and other Army staff officials on Project

80 proposals. 14

To answer these questions a

second briefing for General Taylor was scheduled for 21 December. In the

meantime two formal briefings for the technical service chiefs were held

on Friday, 8 December, known afterward as Black Friday among the once

proud technical service headquarters, to obtain their views. Observers

noted at the outset three empty chairs reserved for Secretary Stahr,

General Decker, and Mr. Vance. When they did appear toward the end of

the briefing they were preceded by Secretary McNamara whose presence had

been unannounced. He said that while he would welcome the views of the

technical service chiefs, he also felt that when the

[349]

President made his decision,

they should support it and not engage in public controversy.

The technical service chiefs did

not present a united front. General Colglazier, a Reserve officer and

civil engineer in private life, Was not a career technical service

officer himself and had spent most of the previous decade dealing with

DCSLOG management problems. The new Defense Supply Agency would remove

the bulk of the Quartermaster Corps from the Army and as a result had

created some confusion among the chiefs. Few appeared to have digested

the details or to have read the several volumes of the Hoelscher

Committee report. They were very concerned about those proposals which

would relieve them of their responsibilities for training and for

officer personnel management. They did not believe the new organizations

could or would provide the kind of trained specialists the Army needed

to keep up with changing technology.

The Chief of Ordnance, Lt. Gen.

John H. Hinrichs, questioned some details of the organization, to which

Secretary McNamara replied that he was interested primarily in the view

of the chiefs on the broad concepts of Project 80, not the details. Maj.

Gen. Webster Anderson, the Quartermaster General, complained that the

new DSA had practically eliminated his agency. The Surgeon General, Lt.

Gen. Leonard D. Heaton, was neutral. Maj. Gen. Ralph T. Nelson, the

Chief Signal Officer, favored the reorganization, while Maj. Gen.

Marshall Stubbs, the Chief Chemical Officer, violently opposed Project

80 since it proposed to eliminate his office entirely. The Chief of

Engineers, Lt. Gen. Emerson C. Itchner, objected to Project 80 proposals

dealing with the training functions of his office. Maj. Gen. Frank S.

Besson, Jr., the Chief of Transportation, who favored the

reorganization, strongly endorsed the basic management concepts advanced

by the Hoelscher Committee. Those present at the briefing were not

surprised later when General Besson was selected as commanding general

of the Army Materiel Command and promoted rapidly to a four-star

general.

After Secretary McNamara had

left, General Hinrichs returned to the attack, accusing the Army staff

of allowing itself

[350]

GENERAL BESSON. (Photograph taken in 1972.)

to be stampeded by the Secretary

of Defense who, he asserted, had taken over the direction of Project 80

from them.15

At his second briefing on 21

December General Taylor expressed greatest concern over technical

service officer personnel management, reflecting the lack of precise

information on the division of responsibility for this function in the

Hoelscher Committee report. Like the technical service chiefs, General

Taylor asked how the proposed Officer Personnel Division of OPO would

improve the quality of technical service officer personnel management.

Lt. Col. Lewis J. Ashley, Project 80's veteran on personnel management,

said that the officer personnel branches of the technical services would

be transferred intact. They would retain their separate service

identities but under larger control groups "combat, combat support,

support, and colonels," permitting greater flexibility in career

management than had been possible under technical service control. A

separate Specialist Branch would manage careers of officers assigned to

the Army's nine specialist programs of which aviation and logistics were

currently the largest. Technical

[351]

service officer personnel

management under OPO would be "branch-oriented, but not

branch-tied." The proposed assignment of officer personnel to OPO,

from all branches of the Army, would also promote greater flexibility on

the career management of officers based on the interests of the Army as

a whole rather than its separate branches.

Colonel Ashley also stressed

that officers would continue to be assigned on the basis of their

technical service branch and that there would continue to be technical

service units identifiable as such in the field. All that really was

eliminated was the "command functions" of the technical

service chiefs. In the 1942 Marshall reorganization the chiefs of the

combat arms had been abolished, but officers continued to be assigned as

infantrymen or artillerymen to infantry and artillery units. Under the

Office of Personnel Operations this concept would be extended to the

technical services with the advantage that positions associated with

particular services or as "branch immaterial" with no

particular service could be filled by the best-qualified personnel

regardless of their assigned branch.

Second only to officer personnel

management was General Taylor's interest in testing new equipment in the

field and on maneuvers. His particular concern was that, under the

proposed Combat Developments Command, the "consumers" or

"users," the combat arms, would not have sufficient voice in

deciding the weapons and equipment they would have to use. He thought a

combat arms officer should command the new Test and Evaluation Agency

under the Army Materiel Command. When General Taylor was told that under

Project 80 combat arms officers would serve with technical service

officers on tests boards and in the environmental or field maneuver

testing center and that it was intended that a combat arms officer

command the Test and Evaluation Agency, he appeared satisfied.

Eleven other topics were

discussed at this second and final briefing of General Taylor. General

Traub said the proposed reorganization affected Army headquarters only

and would not have any direct effect on the Army's combat formations or

on their combat readiness. Mr. Vance, speaking for Secretary McNamara,

outlined the alternative organizational patterns considered for Army

logistics. He said the Secretary believed the

[352]

Army took.too long to make

decisions and that the technical services were a major cause for this

delay. Those alternatives which left the technical services intact with

only one or two major functions removed did not seem much of an

improvement over existing conditions. A return to the holding company

concept of ASF was rejected for similar reasons and because it would

leave a number of services and functions that properly belonged at the

Army staff level under a subordinate command. Alternatives which would

remove more than two functions from the technical services seemed just

as drastic as "functionalizing" them entirely. In the end, Mr.

Vance said, it seemed "better to go all the way," although he

admitted it was "radical surgery.

General Taylor indicated his

approval of the over-all reorganization, but he also wanted a summary of

the problems anticipated in dealing with Congress, the public, and

within the Army itself. Mr. Vance said OSD wanted approval from the

President to notify Congress of the proposed reorganization as soon as

possible according to the terms of the McCormack-Curtis amendment to the

Defense Reorganization Act of 1958, which allowed Congress thirty days

to reject or amend the plan. But for this provision Secretary McNamara's

proposals would have had to run the usual gamut of hearings and action

in both houses of Congress, including the possibilities of amendment and

rejection. Those opposed to the changes involved, especially the

technical services, might have organized their forces successfully to

scuttle the project as they had in the past.16

From the middle of November 1961

to the end of January 1962 Colonel McGregor and his staff prepared over

Seventy-five formal briefings besides those for General Taylor and the

technical service chiefs, including the White House staff and key

Congressional leaders such as Chairmen Carl Vinson and Richard B.

Russell of the House and Senate Armed Services Committees. They also

prepared a summary, Report on the

[353]

Reorganization of the Department

of the Army, explaining the proposed plan. Known as the Green Book, this

was the document through which the Army and the public at large learned

of Project 80.17

On 10 January Secretary McNamara

issued an executive order on the reorganization of the Army which

abolished the statutory positions of the technical service chiefs and

transferred them to the Secretary of the Army subject to Congressional

approval. The same day he forwarded to the President identical letters

for Congressmen Russell and Vinson explaining Project 80 and including

copies of the reorganization plan. President Kennedy formally

transmitted Secretary McNamara's letters to Congress on 16 January. 18

Careful preparation of

Congressional briefings under the direction of Mr. Horwitz helped ensure

favorable Congressional reaction to Project 80. Chairman Vinson's public

endorsement on 5 February seemed to indicate this. "I am satisfied

in my own mind," he said, "from the information I have

received, that this is an important and forward moving step on the part

of the Department of the Army and that its adoption will lead to more

efficiency, particularly in procurement activities and in personnel

planning in the Army." 19

Some adjustments were required.

In response to protests from Michigan's congressmen and governor,

Secretary McNamara personally decided not to transfer functions from

Detroit's Ordnance Tank-Automotive Command to the proposed new Weapons

and Mobility Command at the Rock Island Arsenal. As a consequence the

Weapons and Mobility Command was separated into a Weapons Command with

headquarters at Rock Island and a Mobility Command with headquarters in

Detroit.20

No formal objections arose in

Congress to Secretary Mc-

[354]

Namara's reorganization plan and

it went quietly into effect at 1115 on 17 February.21

Carrying out the reorganization

was the responsibility of the Department of the Army Reorganization

Project Office. This was another name for the Management Resources

Planning (MRP) Branch of the Comptroller of the Army's Directorate of

Organization and Management Systems (ODOMS) . Brig. Gen. Robert N.

Tyson, the Director of ODOMS, had created this office on 10 November

1961 under Colonel McGregor as chief so that Project 80 would have a

formal organization base. The formal functions of the new branch

involved "broad basic research" in the fields of management

and organization and long-range Army planning in these areas.

Temporarily its mission was to provide administrative support for

Project 80 until final decisions had been made and then to direct and

supervise the resultant reorganization under General Traub. DARPO's

location within the Comptroller's Office instead of the Chief of Staff's

Office was to create awkward problems of co-ordination in dealing with

other, coequal General Staff divisions. 22

From a small staff of eight

people with only two clerks during the hectic days of November, the

DARPO headquarters staff had expanded by March 1962 to twenty people,

including six clerks and technical assistants.23

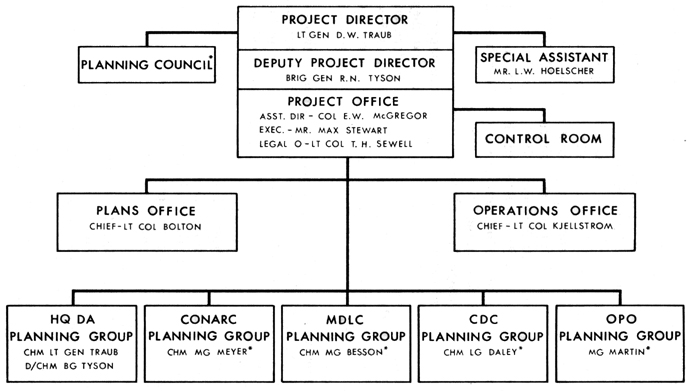

As finally organized,

under a TAGO letter of 26 January 1962, the Department of the Army

Reorganization Project Office operated under the direction of a Project

Planning Council, consisting of General Traub as chairman and the newly

appointed chairmen of the reorganization planning groups, one each for

Army headquarters, Continental Army Command, Combat Developments

Command, Office of Personnel Operations, and Army Materiel Command, who

provided the detailed planning required to carry out Project 80. (Chart

30) In the Project Office one section, an Operations Office, was

responsible for briefings, Congressional relations, and other special

assignments, while a

[355]

DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY REORGANIZATION PROJECT, FEBRUARY 1962

* Member Planning Council

Source: DARPO files

[356]

Plans Office, as its name

implied, developed and co-ordinated the detailed planning and execution

of the reorganization.

The Planning Council met weekly

to review progress and resolve problems and conflicts that arose among

its members on the basis of majority rule. Two of the planning group

chairmen, General Besson and Lt. Gen. John P. Daley, were also slated to

be the first commanding generals of Army Materiel Command and Combat

Developments Command and thus had a vested interest in the success of

the reorganization. Maj. Gen. George E. Martin, temporary chairman of

the OPO Planning Group, was in ill-health and about to retire. Not until

April was a commanding general of the Office of Personnel Operations

selected, Maj. Gen. Stephen R. Hanmer, who then became the OPO Planning

Group chairman.

General Traub in addition to

being Comptroller of the Army and Project Director was also chairman of

the Headquarters, Department of the Army, Planning Group. Consequently,

Col. Frederick B. Outlaw of ODOMS, acted as chairman of the latter group

most of the time. General Decker, General Eddleman, and General Traub

were all to retire soon and, unlike Generals Besson and Daley, would not

have to live with the consequences of their decisions. As a result the

Headquarters, Department of the Army, Planning Group, lacked strong

executive support in dealing with other General Staff agencies and

planning groups.

General Traub's position as

Comptroller and merely one among equals also complicated his role as

Project Director because his colleagues on the General Staff refused to

accept the decisions of the Planning Council, composed largely of

"outsiders," where their interests were involved. General

Vittrup, the Deputy Chief of Staff for Personnel, bluntly told the Chief

of Staff that he would accept the Planning Council's decisions so long

as CDC and AMC did not attempt to make decisions affecting the General

Staff. General Decker and General Eddleman finally agreed that they

personally would have to settle disagreements arising between the DARPO

Planning Council and the General Staff. As a result General Eddleman

[357]

himself had to decide finally

which individuals were to be transferred from the General Staff to the

new commands.24

Secretary McNamara played as

vital a role in the execution of Project 80 as he had in its initiation.

The principal reason for his later intervention was the Army's slowness

in carrying out the reorganization. The final detailed planning

directive, known as DARPO 10-1, did not appear until 19 March.

Preliminary implementation plans, or PIPS, would not be ready until the

end of April. They were then to be revised as "Activation

Plans." The Army Materiel Command was scheduled to begin its

operations on 19 September 1962 and assume full responsibility for the

Army's logistics system in February or March 1963.

At the end of March 1962

Secretary McNamara told Secretary Stahr to accelerate the reorganization

so that AMC would be in full operation by 1 July 1962, nine months ahead

of the DARPO schedule. Secretary Stahr protested. This decision

was only the latest in a series of what he considered unwarranted

interferences by Secretary McNamara in the internal affairs of the Army.

On 2 May he resigned and was replaced in July by Cyrus Vance, who

supervised the final stages of Project 80.25

The General Staff also protested

that the proposed revised schedule would seriously disrupt current

operations, create unnecessary turmoil among personnel, and turn the

reorganization into a series of crash actions of "gargantuan

proportions." Several DARPO planning group chairmen complained that

the General Staff was dragging its feet and delaying decisions. At this

stage neither the principal subordinate commanders of Army Materiel

Command had been selected nor the sites of their headquarters. The

location of AMC headquarters was also undecided.26

[358]

Despite these problems General

Besson and his staff developed a three-stage plan under which Army

Materiel Command would assume responsibility for the Army's logistics

system by 1 July, simply by "taking over in place" the

materiel functions and elements of the technical services. This depended

on the prompt assignment of two hundred key personnel for AMC

headquarters and those of its subcommands to provide essential

continuity of operations. The complete transfer of all personnel

assigned to AMC would take another six months beyond 1 July.

After approval by the General

Staff and Under Secretary Ailes, the Besson plan was finally approved by

Secretary McNamara on 25 April. The only change made in the Besson plan

timetable was to advance the date when Army Materiel Command would

assume its operational responsibilities from 1 July to 1 August.27

On 1 August 1962, when AMC

assumed responsibility for the Army's wholesale logistics system, the

Offices of the Quartermaster General, the Chief of Ordnance, and the

Chief Chemical Officer disappeared. AMC took over most of the Chief of

Ordnance's responsibilities. The Defense Supply Agency had already

assumed most of the Quartermaster General's functions. The remainder,

certain personnel support and supply services, including the care and

disposition of deceased Army personnel and responsibility for the

National Cemetery System, became the responsibility of the new Chief of

Support Services.

The most difficult problem DARPO

and the Planning Council had to deal with was the transfer of

functions and personnel from DA headquarters to the field commands.

Ultimately about 3,200 persons were transferred from the Army staff to

the field, although most of them remained in the Washington area in Army

Materiel Command or Combat Developments Command headquarters.

[359]

Secretary McNamara's

intervention had exacerbated the already existing antagonism between the

General Staff and the DARPO Planning Councll.28

The General

Staff's refusal to accept decisions by "outsiders" on the

DARPO Planning Council continued to delay transferring people from

Headquarters, Department of the Army, to the new field commands because,

among other reasons, the demand for such personnel exceeded the supply.

How to separate command and staff functions inextricably intertwined at

the General Staff level, how to deal with the "hidden field

spaces" in various Washington headquarters staffs, how to allocate

spaces for overhead administrative support, and how to determine where

to assign an individual performing functions belonging to several

organizations under the new dispensation-were the specific issues which

delayed action.29

Faced with this critical

situation, the new Vice Chief of Staff, General Barksdale Hamlett,

agreed that he would personally decide what people were to be

transferred based on recommendations from DARPO. On 8 June he approved

the personnel ceilings for the Army staff and the new commands on the

basis of which DCSPER then made bulk allocations to the new commands

which they could draw on as needed.30

There were other disagreements

about transferring functions and personnel. Beginning in March, CONARC

and CDC disagreed over assigning responsibility for preparing tables of

organization and equipment and field manuals. CONARC insisted that

transferring these functions to CDC, as the reorganization directive

proposed, would disrupt the operations of its school system. The

Planning Council backed by the Chief of Staff decided in favor of CDC,

but dividing the functions, spaces, and personnel involved remained a

problem. The basic issue was the fragmentation of these disputed

functions among CONARC school personnel whose primary responsibilities

were for training. In many cases, the same person was perform-

[360]

ing both training and doctrinal

functions. In the end DARPO had to send a three-man team to visit the

schools, investigate the problems, and make recommendations. Lt. Gen.

Charles Duff, the new Comptroller and Project 80 director, approved the

recommendations of the teams on 31 August.31

Another dispute arose between

the Office of Personnel Operations and CONARC over controlling the

"Flow of Trainees through the Training Base," a battleground

already worked over by the Hoelscher Committee. CONARC wished to control

enlisted assignments from induction through basic training. OPO,

supported by DCSPER, wished to retain TAGO's former responsibilities for

induction. General Traub appointed an ad hoc task force to study

the problem and make recommendations. Its solution, acceptable to both

CONARC and OPO and approved by General Traub, was that OPO should

exercise "staff supervision" over trainees while CONARC would

exercise "operational" control over them from induction

through basic training. At that point OPO would assume responsibility

for future assignments.32

In other areas OPO lost its

responsibilities for Army headquarters civilian personnel management and

for military personnel support and morale services. On 22 March General

Eddleman ordered Army headquarters civilian personnel management to

remain where it was within the Office of the Chief of Staff. Personnel

Support and Morale Services remained within TAGO.33

The principal Army staff

deviation from the Green Book involved the Office of the Chief of

Military History which the DARPO Planning Council agreed should retain

its special staff status and not be transferred to TAGO where it might

be submerged under records keeping. Otherwise the Army staff emerged

from Project 80 relatively unscathed except for the painful transfer of

personnel, spaces, and functions to the new field commands which reduced

it from approximately 13,700 to 10,500 people. DARPO as such ceased

operations on 30

[361]

September 1962, and

responsibility for further reorganization of the Army staff passed to

the secretariat in the Chief of Staff's Office under Project 39a.34

Project 39a, announced by

Secretary McNamara in May 1962, aimed at streamlining decision-making

within the three service headquarters and reducing their personnel by 30

percent during 1963. The reduction of the Army staff under Project 80

was to count for one-half this total, or 15 percent. Mr. Horwitz was

again project co-ordinator and on 11 July 1962 outlined for the three

service secretaries the criteria and objectives of this review.

Secretary Vance took personal responsibility for this study, acting

through Brig. Gen. Arthur W. Oberbeck, Director of Coordination and

Analysis, whom he designated as Project Director. He did not want the

completed report submitted to the General Staff for its opinions.

Instead he wanted it sent through General Wheeler, the new Chief of

Staff, directly to him for approval.35

Army staff agencies made

detailed manpower surveys of their offices to determine how the new 15

percent reduction could be achieved without any mass reduction in force

by consolidating similar functional elements, eliminating overhead and

duplication, and transferring some functions to the field. After

reductions had been made based upon these surveys, the secretariat

claimed that Army headquarters personnel had been reduced during 1963 by

another 14.8 percent, a total of 38 percent-from 13,700 people before

Project 80 to about 8,500.36

The relationship between the

Army staff and the Secretary of the Army's secretariat was reviewed. Mr.

Vance, to avoid developing a civilian staff which duplicated the work of

the

[362]

General Staff, undertook to

confine himself and his staff to broad policy and program decisions

demanding his personal attention.

Streamlining the Army staff's

decision-making process was the subject of an Office of the Chief of

Staff memorandum on 28 May 1963, which attempted to reach a compromise

between the rapid decisions of Secretary McNamara and the slower

traditional summary staff actions of the Army staff.37

One result was to establish a

Staff Action Control Office within the Office of the Chief of Staff to

improve co-ordination. The functions of the Director of Coordination and

Analysis were also redefined to include responsibility for

cost-effectiveness studies and systems analysis within the Army staff.

The most important

organizational change by Project 39a was to resurrect at Mr. Vance's

request the recommendation of the Hoelscher Committee to split DCSOPS

into two agencies. DCSOPS would remain responsible for joint planning

and serve as the Army's contact with the JCS and the joint staff. The

Office of the Assistant Chief of Staff for Force Development, OACSFOR,

created by Department of the Army General Order 6 of 7 February 1963,

would be responsible not only for training and doctrine but also for

force planning and programs, weapons systems, Army aviation, chemical,

biological, and radiological (CBR) material, and later nuclear

operations.38

A minor organizational change eliminated the Office of

the Chief of Army Reserve and ROTC by merging it with the Offfce of the

Chief of Reserve Components under Department of the Army General Order 7

of 13 February 1963.

The Offices of the Chief of

Ordnance and the Quartermaster General had disappeared under Project 80.

The functions of the Chief Chemical Officer, absorbed by DCSOPS under

Project 80 as a separate CBR directorate, were now

[363]

transferred to the new Office of

the Assistant Chief of Staff for Force Development. Placed under the

general staff supervision of DCSOPS on 1 August 1962 the Chief Signal

Officer became the Chief of Communications-Electronics, still under

DCSOPS, on 1 March 1964 by Department of the Army General Order 28 of 28

February 1964, and its field activities were transferred to a new major

field command, the United States Army Strategic Communications Command.

Department of the Army General Order 39 of 11 December 1964 redesignated

the Office of the Chief of Transportation on 15 December as a

Directorate of Transportation within the Office of the Deputy Chief of

Staff for Logistics (ODCSLOG). Of the traditional technical service

chiefs only the Office of the Surgeon General and the Chief of Engineers

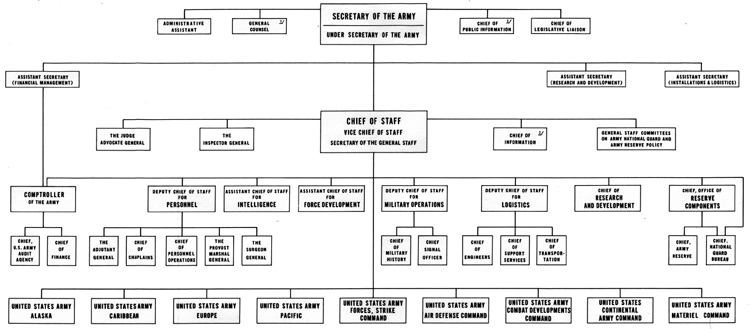

remained in 1965. The Department of the Army major command structure and

the organization of Headquarters, Department of the Army, as of April

1963 are outlined in Chart 31.

In summary, the chief impact of

Secretary McNamara's reforms on the organization and administration of

the Department of the Army was the elimination of the offices of five of

the chiefs of the technical services. Their command functions were taken

over by the Defense Supply Agency and by the new field commands of the

Army, Army Materiel Command and Combat Developments Command, their

training functions by CONARC, their personnel functions by DCSPER, and

their staff functions distributed among the remaining Army staff

agencies.

While the Army staff, especially

DCSLOG, lost about a third of its personnel to the new field commands,

it had successfully rejected a number of changes proposed by the

Hoelscher Committee, particularly in the area of personnel management.

DCSPER remained heavily involved in personnel operations, while TAGO

continued to combine administrative and personnel functions.

Instead of creating a new

three-star position of Director of the Army Staff as recommended by the

Hoelscher Committee, the role and functions of the Secretary of the

General Staff under the Vice Chief as a super co-ordinating staff were

expanded.

While the McNamara reforms, and

Project 80 in particular,

[364]

ORGANIZATION OF THE DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY, APRIL 1963

1 The General Council also Serves as Assistant to the Secretary of the

Army for Civil Functions.

2 The Chief of Public Information also serves as Chief of Information.

Source: AR 10-5, Change 2, 19 Apr 63.

appeared on the surface to be

radical surgery, they were in fact part of a continuing evolutionary

process dating back to the Marshall reorganization of 1942. Reformers

within and outside the Army had struggled for over twenty years to

rationalize the Army staff along recognizably functional lines.

Traditionalists, represented by the chiefs of the technical services,

countered by conducting a series of rearguard actions aimed at

preserving their dual status as both staff and command agencies.

At the same time the Department

of the Army was growing larger and its operations more complex and

diverse. Reformers sought a means of establishing more effective

executive control over these expanding activities along lines similar to

those developed by DuPont and General Motors in the 1920s. One means was

to functionalize the archaic structure of Army and Defense Department

appropriations and later to reorganize them on the basis of military

missions performed. Another and parallel effort was to establish such

controls through a top-level staff above the Army staff which would

co-ordinate and integrate military budgets with military plans. Project

80 and Project 89a were part of this evolutionary process which, judging

on the basis of past performance, was likely to continue indefinitely

into the future.

[365]

Endnotes

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

Return to the Table of Contents