- Source: Timothy W Stanley, American Defense and National Security

(Washington: Public Affairs Press, 1956), p. 81.

-

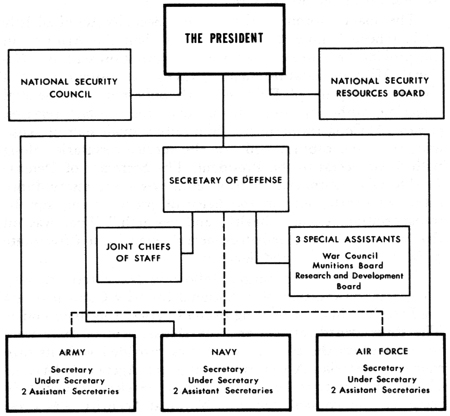

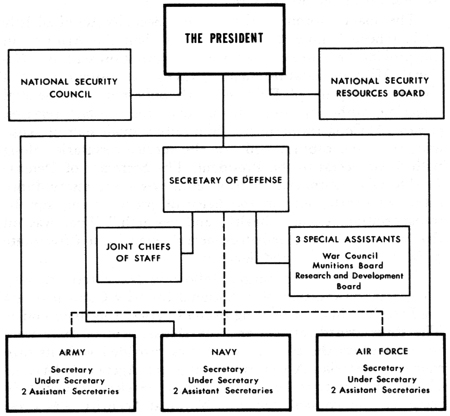

- D. Eisenhower commented a decade later: "In the battle over reorganization

in 1947 the lessons of World War II were lost. Tradition won. The resulting

National Military Establishment was little more than a weak confederacy of

sovereign military units . . . a loose aggregation that was unmanageable."

4

-

- Congress also did not make any provision for integrating military budgets

with military strategy. Supervising the military budgets was the responsibility

of the several civilian secretaries, and Congress continued to provide funds

according to an increasingly archaic appropriations structure. As a result

- [166]

- the gap was to widen between military strategies developed by the JCS and

the military budgets appropriated by Congress.5

-

- The immediate impact of the National Security Act on the Army was the final

separation and independence of the Army Air Forces. The Chief of Staff of

the Army and the Chief of Staff-designate of the Air Force signed an agreement

on 15 September 1947, known as the Eisenhower-Spaatz agreement, which provided

the framework within which men, money, and resources were to be transferred

from the Army to the new Department of the Air Force. Among other things it

said "Each Department shall make use of the means and facilities of the

other departments in all cases where economy consistent with operational efficiency

will result." The last phrase was a deliberately oracular expression

allowing the Air Force to justify creating its own supply system despite the

fact that it would duplicate and overlap facilities and services provided

by the Army in many cases.6

-

- The National Security Act made one minor change affecting the Army by redesignating

the War Department as the Department of the Army.

-

-

- While the Air Forces and the Navy struggled with each other over unification,

the Army sought to solve several internal problems created by the Eisenhower

reorganization. At a conference with General Eisenhower on 13 November 1946,

the Army staff proposed a radical reorganization of both the headquarters

and field establishment. General Eisenhower vetoed this plan. "Nothing

should be done," he said, "to disrupt

- [167]

- the relationships which have already been established until the outcome

of unification has been decided upon.7

-

- In the field, relations among the Army staff, the technical and administrative

services, AGF headquarters, and the ZI armies were confused. The problem was

aggravated by the constant referral of petty local disputes all the way up

the line to the General Staff and the Chief of Staff. Decentralization was

not working in this area.

-

- The Directorate of Organization and Training (DOT), responsible for implementing

and interpreting the Eisenhower reorganization, outlined the problem in a

staff study of 15 August 1947. Confusion, it said, existed at all levels of

command: at the installation level, in the ZI Army headquarters, in AGF headquarters,

and within the Army staff. In the field the greatest number of complaints

arose over the ZI Army commanders' responsibility for some sixty housekeeping

activities at Class II installations,8

those directly under the command of

chiefs of technical or administrative services in Washington.

-

- The Directorate of Organization and Training estimated an average of one

dispute a day was being referred to them by ZI Army commanders involving these

housekeeping functions, the number of people performing them, or the funds

required. The most important functions were repairs and utilities, including

custodial services, fixed communications services such as long-distance telephone

lines, and transportation services, particularly administrative motor pools.

The Army commanders, for instance, found it difficult to control the expenditure

of limited funds for long-distance calls between technical service installations

and their Washington headquarters. Differ-

- [168]

- ing ZI Army and technical service personnel systems and wage scales created

additional problems.

-

- A second problem concerned the divided loyalties of Army commanders reporting

to the War Department on administrative matters and to the Commanding General,

Army Ground Forces, on tactics and training. Headquarters, Army Ground Forces,

often intervened in primarily administrative matters.

-

- To solve these problems the Director of Organization and Training recommended

a detailed survey of Class II installations to determine which could be reclassified

and brought directly under the control of ZI Army commanders. It also recommended

removing Headquarters, Army Ground Forces, from the administrative chain of

command and restricting it to tactical and training functions.9

-

- A similar proposal discussed by Lt. Gen. J. Lawton Collins, the Deputy Chief

of Staff, with Lt. Gen. Raymond A. Wheeler, the Chief of Engineers, and Maj.

Gen. Thomas B. Larkin, the Quartermaster General, would have transferred responsibility

for all training, schools, and boards from the technical services to the Army

Ground Forces. Generals Wheeler and Larkin opposed this scheme because it

would deprive the technical services of a vital command function. The proposal

in their opinion was not only undesirable. It would not work. Only their own

personnel possessed the specialized knowledge and experience needed for proper

training.10

-

- General Jonathan M. Wainwright, Commanding General, Fourth Army, supported

the diagnosis and views of Lt. Gen. Charles P. Hall, Director of Organization

and Training, in a personal letter to General Eisenhower. He complained of

having to plan expenditures and account for funds spent by agencies over which

he had no control. The solution he recommended would place ZI Army commanders

in charge of all posts and installations in their areas. General Jacob L.

Devers, Commanding General, Army Ground Forces, agreed with General Hall and

proposed to reduce the number of Class II installations by limiting them to

those serving more than one

- [169]

- GENERAL LARKIN

-

- Army area, such as Ordnance arsenals and Quartermaster depots.11

-

- General Lutes, Director of Service, Supply, and Procurement, pointed out

that General Wainwright, in urging unity of command for the ZI armies, assumed

falsely that such armies were like overseas theaters. They were not, Lutes

said, because arsenals and depots within the United States served the entire

Army, not just the installations under a particular Army commander. Placing

them under local Army commanders would be impractical.12

-

- General Eisenhower referred the problem to an Advisory Group he had set

up in June 1946 under Lt. Gen. Wade H. Haislip to study Army organization

and management problems. In its final report, submitted on 29 December 1947,

known as the Cook report after its principal author, Maj. Gen. Gilbert R.

Cook, the Advisory Group recommended that Army Ground Forces should be eliminated

as such and become a special staff agency in Army headquarters with responsibility

for schools, combat arms boards, organization and training of

- [170]

- units and individuals, and combat doctrine. The field armies would command

all military installations in their areas including Class II installations

and report directly to the Chief of Staff. Each Army area would then be organized

and would function like an overseas theater of operations.

-

- Realizing the proposed changes could not be made overnight, the Advisory

Group recommended selecting a specific ZI army as a theater of operations

and giving its commander complete control over every Army installation, facility,

and activity in his army's assigned area for about six months in order to

give the idea a fair trial.13

-

- After studying these recommendations General Collins instructed General

Hall to prepare a revision of War Department Circular 138 that would redesignate

Headquarters, Army Ground Forces, as Headquarters, Army Field Forces, and

limit its functions to staff supervision over all Army training, "including

training of technical and administrative troops," to supervision of all

service schools and former Army Ground Forces boards and to responsibility

for the development of tactical doctrine. Army Field Forces was to be "removed

from the chain of command and administration" except for specified training

functions. Collins also tentatively decided to war game the theater of operations

proposal of the Advisory Group for a three to six months period to determine

its practicality.14

-

- After consideration and amendment by the Army

staff General Collins' plan emerged as Department of the Army Circular 64

of 10 March 1948. Army Ground Forces, stripped of its command functions, became

the Office, Chief of Army Field Forces, the field operating agency for the

Department of the Army within the continental United States, for the general

supervision, co-ordination, and inspection of all matters pertaining to the

training of all individuals utilized in a field army.15

It was responsible

for supervising training, preparing training literature, developing

tactical doctrine, and supervising the activities of Army Ground Forces boards

in developing military equipment. Because the technical and administrative

services commanded personnel and schools not "utilized in a

- [171]

- field army" the circular urged "the closest collaboration and

coordination between the Chief, Army Field Forces, and the heads of the Administrative

and Technical Services in all matters of joint interest." Exempting Class

II activities and installations from control by the ZI Army commanders was

a major departure from the recommendations of General Collins and the Advisory

Group and another victory for the technical services.

-

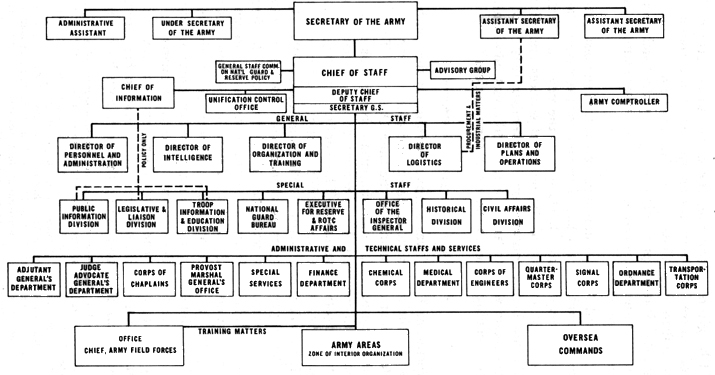

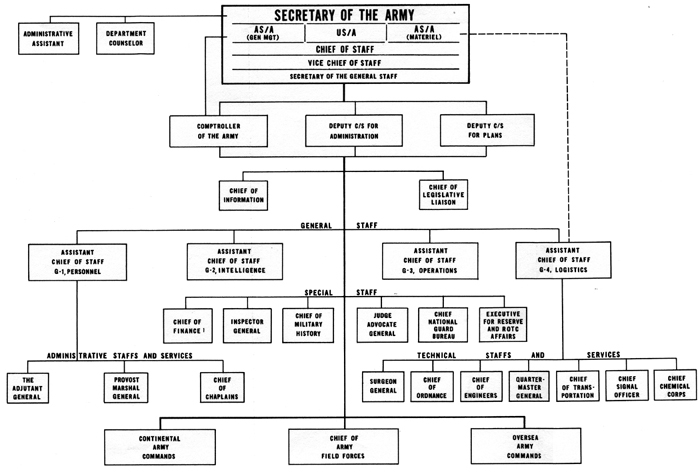

- There were minor changes under Circular 64 in Army headquarters. The Secretary

of the General Staff appears for the first time on the official organization

chart of Department of the Army headquarters, and the Director of Service,

Supply, and Procurement was redesignated as Director of Logistics. (Chart

16) One major change, the abolition of the Directorate of Research and Development

as a separate staff agency and its absorption by the Directorate of Service,

Supply, and Procurement, had taken place earlier under Department of the Army

Circular 73 of 19 December 1947. The ostensible reason for this change was

to limit the number of agencies reporting to the Chief of Staff. A more practical

reason was the lack of funds for research and development activities.

-

- The next step was to carry out General Collins' decision to war game the

theater of operations concept. The Third Army area was chosen and the project

was designated as the Third Army Territorial Command Test (TACT). In October

1948 the Director of Logistics placed all production, supply, and training

activities and installations in that area, including control over their operating

funds, under the Third Army commander for six months. Later the experiment

was extended to 1 November 1949.

-

- The technical service chiefs remained opposed to transferring their Class

II functions and to Operation TACT. The substantive issue was control over

those installations and related activities with Army-wide responsibilities,

arsenals, Quartermaster depots, and ports of embarkation. The Chief of Ordnance

complained that placing control over such operations under an Army commander

removed from the agency responsible for such functions the authority necessary

to do the job. Such a move was a clear violation of the principle of unity

of command which asserted that a commander assigned a task

- [172]

- ORGANIZATION OF THE DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY, 10 MARCH 1948

-

-

- Source: DA Circular 64, 10 Mar 48.

- [173]

- should be given control over the means to perform it. This was, of course,

the very reason the ZI Army commanders wished control over Class II installations.

Unity of command was not the clear-cut principle envisaged by the Patch-Simpson

Board, but rather a misleading expression which simply fueled factional disputes.

-

- The Third Army commander considered the test a success and recommended that

Class II installations remain under his control. General Wade H. Haislip,

as the new Vice Chief of Staff, decided in favor of the technical services

and directed that the test be discontinued on 1 November 1949. The only changes

made were to assign a few additional administrative or housekeeping duties

to the Army commanders.16

-

-

- Operation TACT was a minor skirmish in the continuing battle over the role

of the technical and administrative services as independent commands. At the

time Operation TACT was first being considered, a more important battle took

place over a proposal to resurrect Army Service Forces in some form as an

Army logistics command. This conflict had begun on 15 February 1947 when General

Eisenhower appointed General Haislip president of a Board of Officers to Review

War Department Policies and Programs, a board composed of representatives

from the Army staff, the Air Forces, and the Ground Forces. The Haislip Board,

as it was known, made two reportsa preliminary one on 25 April 1947 and a

final one on 11 August 1947. Like the Chief of Staff's Advisory Board the

Haislip Board was interested in attaining greater unity within the Army and

greater efficiency and economy of operation. This policy meant greater executive

control over the department's operations than the Eisenhower reorganization

had provided. As one means of accomplishing this goal, both boards recom-

- [174]

- mended limiting the number of staff agencies reporting to the Chief of Staff

directly. This recommendation was one factor in eliminating the Research and

Development Division in December 1947. The Haislip Board suggested expanding

the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff by adding an assistant for planning

and another for operations in order to keep these functions separate. The

Cook report suggested a deputy for ZI administration and one for field operations.

Once these agencies were operational "authority to issue orders to the

field [should] be withdrawn from levels below the Deputy Chiefs of Staff."

17

-

- An obvious means of limiting the number of agencies reporting directly to

the Chief of Staff was to resurrect ASF. General Eisenhower had kept the issue

alive after the demise of ASF in a hurried penciled note in December 1946

to the Deputy Chief of Staff, stating: "My own belief is that if war

should come, ASF should be immediately reestablished. Should not our plans

so state?" 18

-

- Sometime later he directed General Lutes, the Director of Service, Supply,

and Procurement, to develop an organization capable of expansion as the headquarters

for such a materiel command. General Lutes himself believed the best solution

was to create a materiel command similar to that of the newly created Department

of the Air Force in peacetime, if only to train its personnel to operate as

a team in war.

-

- The subject came up at a meeting attended by General Eisenhower, General

Omar N. Bradley, who was shortly to succeed him as Chief of Staff, General

Collins, the Deputy Chief of Staff, and Lt. Gen. Henry S. Aurand, General

Lutes' successor as Director of Service, Supply, and Procurement, on 21 January

1948. General Eisenhower said the Directorate of Service, Supply, and Procurement

should remain as a staff division in peace "under the concept of Circular

188, but provide the nuclear organization for an ASF as an operating command

in war." This command would also absorb the lo-

- [175]

- gistic functions of the Army staff but not the administrative services as

ASF had done in World War II,19

-

- General Collins then instructed General Aurand on 2 February 1948 to develop

an "outline plan for a wartime ASF" in co-operation with the other

General Staff directorates. An informal ad hoc committee headed by an officer

from General Aurand's office considered several alternative methods. The committee

considered first three parallel commands, personnel, training, and logistics,

each under a General Staff director. The training command would include the

training of technical and administrative service personnel. These three commands

would function under a "Deputy Chief of Staff for Mobilization"

and ZI administration. A "Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations"

would be responsible for overseas commands and any ZI combat operations. Within

the continental United States the Army commanders would control housekeeping

functions in their areas along the lines suggested in Operation TACT.

-

- Such a plan would have stripped the technical and administrative services

of their training and personnel functions, subordinating them to the Deputy

Chief of Staff for Mobilization. In the field the services would be subordinate

to the Army commanders. Those services performing such unique functions as

medicine, communications, construction, and transportation would become Army

staff directorates. The Chemical Warfare Service would be eliminated.

-

- A less drastic alternative proposed to adopt the ASF Post-War Organization

Plan of 1944, retaining the technical and administrative services as such.

The final proposal suggested a Logistics Command similar to that recommended

in the Somervell Plan of 1943. Under a "Director of Logistics" and

five functional directorates, plans, requirements and resources, operations,

administration, and control, the technical services would be reorganized into

functional groups-research and

- [176]

- GENERAL BRADLEY. (Photograph taken in 1945.)

-

- development, procurement, supply, fiscal, construction, communications,

medical, and transportation.20

-

- General Aurand wanted to present these proposals to the General Staff for

comment first and, after obtaining agreement within the General Staff on what

position to take, to consult the technical services. Learning that General

Aurand was to brief the Assistant Secretary of the Army, Gordon Gray, on The

Pros and Cons of a Logistics Command, the Chief of Engineers, General Wheeler,

acting as spokesman for all the technical service chiefs, requested permission

to present their case to Mr. Gray at the same time. At this point General

Eisenhower revised his earlier position. In a letter to General Bradley written

after he had resigned as Chief of Staff and retired he said his 1946 note

did not "imply any thought that the technical and procurement services

should be abolished." To this he was "violently" opposed. He

simply meant that "in war, a single command, responsible only to the

Chief of Staff should

- [177]

- be established over all this type of activity and organization." This

system was not "desirable in peace." 21

-

- Armed with a copy of this letter General Wheeler and the other technical

service chiefs confronted General Aurand on 13 April 1948 in Mr. Gray's office.

Speaking for his colleagues, General Wheeler attacked the proposed logistics

command. He cited the Patch-Simpson Board recommendation that ASF be abolished,

General Eisenhower's letter, and the current organization of the Army staff

outlined in Department of the Army Circular 64, 10 March 1948. He referred

to the contributions made by the technical services in two world wars and

emphasized the undesirability of introducing an additional staff layer between

the technical services and the Chief of Staff which would require additional

scarce technical specialists. He claimed that industry favored the Army's

present "technical procedures."

-

- Eliminating the technical services, he said, would require reorganization

and re-education of all the armed forces and war industries. Further, the

proposed logistics command did not deal with other important technical service

problems like training and intelligence. In conclusion, General Wheeler stated

that the chiefs of the technical services believed a logistics command would

result in confusion and conflict in command and "in conspicuous extravagance

in the utilization of critical personnel." In substance they opposed

creating another ASF or logistics command whether in peace or in war.22

-

- Faced with this opposition Assistant Secretary Gray suggested continued

planning for a wartime ASF but designated the project more euphemistically

as a proposal rather than a plan since it had not yet been approved. General

Aurand, concluding that the decision earlier agreed upon in favor of formal

planning for a wartime ASF had been practically abandoned, asked that his

office be relieved of responsibility in the matter. General Collins agreed

and ordered responsibility

- [178]

- for studying the issue of a logistics command transferred to the Management

Division of the new Army Comptroller's Office.23

-

-

- Both the Advisory (or Cook) and Haislip Board reports had recommended establishment

of a management planning or comptroller's office at the General Staff level.

On 8 September 1947 Secretary of War Kenneth C. Royall, who had served under

General Somervell in ASF headquarters during the war, appointed Edwin W. Pauley

as his special assistant to study the Army's various logistics programs and

"business practices" and to recommend improvements "in the

interest of economy and efficiency as contemplated by unification legislation."

24

-

- Mr. Pauley in investigating Army fiscal procedures found that no one from

the Secretary on down, including the chiefs of the technical services, knew

the real dollar costs of the operations for which they were responsible. The

principal reason was that each technical service employed its own unique accounting

system which did not cover all its functions and missions. Pauley recommended

organizing an office of "Comptroller" for the Army to correct these

deficiencies through the development of sound business management and cost

accounting practices which would cover the total costs of the Army's major

missions, programs, and activities, including the operating costs of each

Army installation by major activity. These revolutionary proposals required

a degree of control by the Secretary and the Chief of Staff over the Army's

budget which traditional Congressional methods of appropriating funds would

hardly permit 25

- [179]

- The Haislip Board had also criticized the Army's financial management in

the context of its broad review of the Army's missions and the resources needed

to fulfill them. Noting the inadequacy of the Army's current budget, it warned,

"Either the War Department must revise its programs downward to come

within the means which the country seems willing to furnish in men and dollars,

or the country must revise upward its estimate of the imminence of the threat

to its security and increase the means to meet the War Department's requirements."

-

- Inadequate funds made economy of operations all the more essential, but

in the board's opinion ". . . neither the organization, the procedures,

nor the general attitude of the Army is conducive to maximum economy."

It did not see how substantial economies could be made within the existing

fiscal structure of the Army "which largely divides fiscal authority

from command responsibility." It urged employment of improved management

techniques in "organization, procedures, statistical reporting, budgeting,

cost accounting," and similar activities. As a first step in this direction

it recommended establishing in the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff "an

agency similar to the Navy's Management Engineer or the Air Force's Comptroller

to attack this problem on a specialized and continuing basis." 26

-

- Similarly General Cook had recommended that Congress enact legislation freeing

the Army from an archaic budget structure where the tail wagged the dog. The

existing appropriations structure recognized only the technical services.

New legislation should provide that money be appropriated for the Department

of the Army and not to individual technical services and that budget categories

be related to the Army's missions. The Army itself net-ded an agency where

organizational, management, and financial problems would be treated together

as one problem. A staff division concerned with "organization and training"

was not such an agency. The least the Army could do would be to set up a management

planning branch within the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff. The Cook report

recommended placing such functions under a Deputy Chief of

- [180]

- Staff for Zone of Interior Administration along with responsibility for

Army logistics and personnel.27

-

- After considering these reports, both Secretary Royall and General Eisenhower

agreed on the need for an agency at the General Staff level which would be

responsible for the Army's budget and fiscal programs as well as organization

and management. Secretary Royall favored appointment of a civilian as comptroller

who would work directly under the Secretary, while General Eisenhower preferred

that the comptroller be part of his military staff.28

-

- General Eisenhower's view prevailed. Department of the Army Circular 2 of

2 January 1948 provided for a military comptroller with a civilian as deputy

within the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff. The directive transferred

to this office the functions and personnel of those staff agencies principally

concerned with the Army's financial management, the Budget Office, the War

Department Manpower Board, the Central Statistical Office, and the Chief of

Staff's Management Office. As the department's fiscal director the Comptroller

was to supervise also the operations of the Office of the Chief of Finance.

Department of the Army Circular 394 of 21 December 1948 additionally transferred

supervision of the Army Audit Agency to his office from the Assistant Secretary

of the Army. As the Army's management engineer the Comptroller would play

a major role in the Army management and organization in the next decade.

-

- The functions and responsibilities of the Army Comptroller lacked statutory

authority until the passage of the National Security Act amendments of 10

August 1949, which emphasized the Comptroller's fiscal responsibilities.29

- [181]

-

- Col. Kilbourne Johnston, the son of Brig. Gen. Hugh S. Johnson of World

War I and NRA fame, was the first Chief of the Management Division of the

Comptroller's Office. Like his father before him he was an aggressive promoter

of the concept of a functionally organized Army staff. Like his father he

also encountered bitter opposition from the chiefs of the technical services.

-

- Among his first assignments was the development of a plan for reorganizing

the Army staff under a proposed "Army Bill of 1949," including a

re-examination of the question of resurrecting Army Service Forces in some

form or other. The result was a lengthy two-volume interim staff study on

The Organization of the Department of the Army,

submitted on 15 July 1948. Known as the Johnston plan, it was the first detailed

analysis of Army organization in the postwar period and the predecessor of

several more to come.30

-

- In the Johnston plan the Management Division noted that previous studies

by the Organization and Training Division, the Haislip and Cook Boards, and

the Logistics Division had raised two basic questions: "Are the Technical

Services to be functionalized?" and "Are Departmental functions

to be decentralized to area commands through a single command channel?"

-

- Echoing General Somervell's views, it asserted that in both world wars the

Army had had to abandon its "permanent statutory structure" and

create an emergency organization for two major reasons: the lack of a genuinely

functional staff with single staff agencies responsible to the Chief of Staff

for each of the department's major functions, and "an unwieldy span of

control" with too many agencies responsible and reporting directly to

the Chief of Staff.

-

- After both wars the emergency organization had been abandoned because it

had placed single-function operating agencies like ASF on top of permanent

multifunction bureaus.

- [182]

- A tremendous headquarters staff and much duplication of effort was the result.

Another reason was overcentralized control by wartime agencies which had created

friction, delay, and difficulties in co-ordination. On top of this most military

personnel misunderstood or misinterpreted the reasons which led to creating

wartime organizations and their emergency procedures.31

-

- The Management Division next surveyed current departmental operations and

concluded that there were eight major weaknesses. Too many agencies were reporting

directly to the Chief. of Staff, a situation duplicated in the internal structure

of the various staff agencies themselves. Army staff functions, such as training

and supply, were fragmented among several agencies and staff levels, producing

conflict and duplication. There was too much centralization within each agency.

There were multicommand channels including the technical and administrative

services and various special staff agencies in addition to the General Staff.

There was a gap between strategic and logistical functions within the General

Staff and the technical services, little integration and control, continual

duplication, and a waste of manpower and money which still failed to produce

any "authoritative, integrated logistical-strategical plans." The

General Staff neglected its planning functions because it was involved in

daily operational details. The staff's complicated organizational structure

caused delays through excessive staff-layering and too much attention to minor

activities. The survey counted 294 divisions, 884 branches, and 638 sections

in Army headquarters plus 86 standing committees and boards, not to mention

many temporary committees. Last, rigid compartmentalization created situations

in which the left hand did not know what the right hand was doing, and intramural

disputes, even on minor matters, continued to go all the way up the chain

of command to the top. Consequently the Army staff and individual agencies

could not act promptly and effectively.

-

- All these were age-old problems dating back at least to Mr. Root's day,

but there were others. On the basis of the Haislip Board's study of the Army

fiscal year 1949 budget requests, the Management Division agreed there were

no effective procedures for integrating and balancing requirements with resources.

The

- [183]

- General Staff's logistics planning bore little relation to the Congressional

archaic appropriation structure based on the technical services. Additionally,

appropriations failed to follow recognized channels of command. No adequate

machinery existed for readjusting budgets after the Bureau of the Budget and

Congress had altered the Army's initial budget request. Finally, diffusion

and fragmentation of manpower controls among many agencies made integrated,

rational control over manpower impossible.32

-

- The current organization of the Army, the study said, was bad enough, but

when the President's authority under the First War Powers Act of 1941, which

Congress had extended several times, expired things would be worse because

the department would have to return to its even more chaotic prewar organization.

-

- Permanent legislation was necessary to provide a sound organization that

would not require drastic changes in order to fight a war, would improve efficiency,

and reduce overhead in Washington. As the basis for such legislation the Johnston

plan suggested a number of guiding principles, repeating many familiar ASF

arguments.

-

- The Army should have a functional staff where single agencies were responsible

to the Chief of Staff for each major functional program. "Traditional

service organization is neither functionally nor professionally constituted

in the light of modern warfare even though originally so conceived. Evolution

has rendered the Technical Services bureaucratic to the point of obsolescence."

There should be a reduction in the number of agencies reporting to the Chief

of Staff, a single staff layer in the General Staff, and genuine decentralization

of operations to the field. A properly organized staff should provide a simple,

easily understood structure, divorce operations from planning, integrate current

program planning with war and mobilization planning, integrate logistical

operations and planning, provide a single command channel to the field,

reduce the size of Army headquarters by limiting such activities in Washington

to those which had to be performed there, and

- [184]

- provide "self-contained" continental Army areas capable of independent

action in case of a national emergency.33

-

- The three principal features of the Johnston plan designed to achieve these

objectives were (1) to reduce the number of agencies reporting to the Chief

of Staff by creating a Vice Chief of Staff and two Deputy Chiefs of Staff

who would supervise the General Staff; (2) to functionalize the Army staff,

meaning the technical and administrative services, along lines similar to

the old Somervell-Robinson proposals; and (8) to place all ZI field installations

and activities under the Army commanders, including those Class II installations

commanded by the chiefs of the technical and administrative services. In summary,

the principal aim of the Johnston plan, like its predecessors, was to abolish

the technical services as independent commands, making them purely staff agencies.

-

- The Johnston plan provided the Secretary with two new assistant secretaries,

one for politico-military matters and the other under the Under Secretary

for resources and administration. The Chief of Staff would have a vice chief

and two deputy chiefs, one for plans and another for operations, which would

keep these functions separate. Other agencies reporting directly to the Chief

of Staff would be the Army Comptroller, the Chief of Information, and the

Inspector General. Under the two deputy chiefs the plan proposed ten functional

directorates Personnel and Administration which would supervise The Adjutant

General's Office; Intelligence; Training, which would supervise the Chief

of Army Field Forces; the Quartermaster General for Supply and Maintenance;

the Chief of Transportation; the Chief Chemical Officer for Research and Development;

the Chief of Ordnance for Procurement; the Chief of Engineers for Construction;

the Chief Signal Officer for Communications; and the Surgeon General. As alternatives,

it suggested placing the Chief of Transportation under the Quartermaster General,

reverting to the pre-World War II pattern, or placing the Chief Chemical Officer

as Director for Research and Development under the Chief of Ordnance.34

-

- Since all these changes could not be made overnight the Johnston plan suggested

reorganizing the General Staff itself

- [185]

- as "Phase I." Functionalizing the technical and administrative

services would come later. Under Phase I the vice chief and two deputy chiefs

would be appointed to carry out the reorganization. The existing Plans and

Operations Directorate would be transferred to the Deputy Chief of Staff level

to assist them, along with four reorganization "command posts,"

one each within the secretariat, in Plans and Operations for the zone of interior,

in the Director of Logistics Office to reorganize the technical services,

and one under the Director of Personnel and Administration for the administrative

services.

-

- Colonel Johnston thought transferring personnel, administrative, and training

functions to appropriate staff divisions could be done with little difficulty

as a second phase of the reorganization. The last phase, transferring logistical

functions, would be much more difficult because it involved many field installations.35

-

- To reduce the number of agencies reporting to the Chief of Staff the Johnston

plan proposed to place the Office of the Chief of Finance under the Comptroller

and the Historical Division under The Adjutant General, the Inspector General

in the Office of the Vice Chief of Staff, and the Legislative and Liaison

Division, the Public Information Division, and the Troop Information and Education

Division under the Office of the Chief of Information. The technical

and administrative services would "normally report" to the Chief

of Staff "through" either the Director of Logistics or the Director

of Personnel and Administration.36

-

- Colonel Johnston submitted his study and recommendations on 15 June 1948

to the Deputy Chief of Staff, General Collins, to the Chief of Staff, General

Bradley, on 20 July, and to the General Staff and technical services for comment

in August.37

Most of the General Staff agreed with the general

- [186]

- principles of the Johnston plan. Maj. Gen. Harold R. Bull, Acting Director

of Organization and Training, however, proposed an alternative solution that

was closer to the organization finally adopted. Separating plans and operations,

he said, would create an awkward span of control for the Deputy Chief for

Operations. Instead there should be three deputy chiefs, one for plans, another

for operations, and a third for administration, including logistics. He would

also replace the existing directorates with four functional Assistant Chiefs

of Staff. He would not functionalize the technical services, but he would

relegate them to a purely advisory role by removing from them control over

personnel, intelligence, training, and logistics operations and taking away

their command over field installations and activities.38

-

- Maj. Gen. Daniel Noce, the Deputy Director of Logistics, told General Aurand

the technical services might oppose the Johnston plan. He recalled their successful

opposition to General Somervell's earlier proposals. Unless they were "brought

into the picture" and "sold . . . as partners in the new reorganization,"

their opposition would wreck the Johnston plan. Its chief defect, he thought,

was the concept of functionalization itself which would divide responsibility

for commodities among several agencies.39

-

- Brig. Gen. John K. Christmas, an Ordnance officer serving as Chief of the

Logistics Directorate's Procurement Group, recommended retaining the technical

and administrative services. He would go no further than placing them solely

under the supervision of the Directors of Personnel and Administration and

of Logistics. His Ordnance background was apparent when he asserted functionalization was unworkable in any organization which produced, procured, and used

as many and as wide a variety of products as the Army did. Functionalization

would divide responsibility for producing, procuring, and supplying commodities

instead of placing responsibility for them properly in one agency "from

factory to firing line." 40

- [187]

- Except for Maj. Gen. Frank A. Heileman, the Chief of Transportation, the

technical service chiefs opposed the Johnston plan in principle and in detail,

both individually and collectively, in writing and in person. Collectively,

on 31 August 1948, they signed a joint round robin protest to the Chief of

Staff. As their appointed spokesman Maj. Gen. Everett S. Hughes, the Chief

of Ordnance, expressed in person their opposition on 15 September 1948 to

the Chief of Staff, General Bradley, and the Army staff.

-

- General Hughes said the basic proposition of the Johnston plan was to abolish

the technical services through functionalization. The Army had debated this

issue before. The Patch-Simpson Board had rejected it, and General Eisenhower

himself was on record as "violently" opposed to the concept. Industrial

leaders whom he had consulted opposed functionalization. He would agree to

the control over the technical services but not to their abolition or consolidation.

The question he did not consider was how a functionally oriented organization

like the General Staff could effectively control the operations of commands

with multiple functions like the technical services.

-

- General Hughes then presented another round robin letter signed by himself

and six other technical service chiefs opposing the Johnston plan. In an organization

the size of the Army which had developed through "generations of experience,"

it stated, major changes should not be made unless they were "conclusively

advantageous." The proposed reorganization was not. It was unsound. It

would break up the technical services which had proven themselves in all American

wars and had a right to continue serving the country. It would destroy "their

team spirit, their team knowledge, their team power for action and their team

contacts with each other and with the industrial and professional world."

Instead of the Johnston plan, they proposed:

-

- to continue the present responsibility and statutory authority of the various

Technical Services, which means they should continue to render specialized

services, to train personnel, to do research and develop, to design procure,

store, issue and maintain the closely related family groups of commodities

with which they are charged.

-

- Additionally they asked that the technical services continue to

- [188]

- command their own field installations, personnel, and operations.

-

- After General Hughes' talk, General Bradley said no firm decision had yet

been made. It would not be easy to reach one, but he and others felt something

had to be done. It was not enough to say that because we have always "done

it this way" that we should continue doing it. General Collins urged

the technical service chiefs to consider at least reducing the procurement

services to Ordnance, Quartermaster, and Signal.41

-

- Colonel Johnston then revised his plan after conferences with the General

Staff. The principal change, reflecting the views of the Director of Organization

and Training, involved the functions of the two new Deputy Chiefs of Staff.

Instead of one for plans and another for operations, there was one for plans

and operations and another for administration. Phase I would also place the

technical and administrative services directly under the authority of the

Directors of Personnel and Administration and of Logistics.

-

- General Bradley urged approval of Phase I of the Johnston plan at least

because "We are every day convinced that the present organization here

at the top will break down. We just can't handle it." Secretary Royall

still hoped to restrict procurement to Ordnance and Quartermaster. General

Lutes also reminded him there was no provision for effective control over

the technical services because their supervision was divided among the Army

staff. General Eisenhower, who was also present warned against rejecting the

technical service chiefs' views as "hopeless" and "bureaucratic."

They sincerely believed they could perform properly under the existing system.

But he did wonder what had become of his earlier suggestion to limit the number

of technical services involved in procurement.

-

- General Aurand and his staff also opposed the Johnston plan proposal to

divide responsibility for commodities along, functional lines. He did criticize

the Ordnance Department for continuing to base its field organization on Ordnance

districts

- [189]

- which handled all commodities in their areas, a system abandoned by the

other technical services in favor of single national procurement offices for

individual commodities or groups of commodities.42

-

- Following conferences with Generals Bradley and Collins, and with Colonel

Johnston, Secretary Royall on 20 September said he enthusiastically agreed

with the ultimate goals of the Johnston plan as well as the detailed proposals

for Phase I. He agreed to place the technical services under the control of

the Director of Logistics but wanted a parallel link to the Assistant Secretary

of the Army in charge of procurement. Secretary Royall asked that the concept

of a single personnel and administrative agency be explored further. Finally,

he selected General Collins as the new Vice Chief of Staff, Lt. Gen. Albert

C. Wedemeyer as Deputy Chief of Staff for Plans and Operations, and General

Haislip as Deputy Chief of Staff for Administration.43

- A General Staff working committee revised Colonel Johnston's amended plan

further. The knottiest problem remained the relations between the General

Staff directorates and the technical services now that they were to be placed

under the control of the Director of Logistics. The Acting Director of Organization

and Training pointed out that "All General Staff Divisions have a vital

interest in both budget and manpower requirements of the Technical Services

in carrying out their assigned missions." The Director of Logistics,

he said, should review rather than control these operations. General Aurand,

on the other hand, while agreeing to allow direct communications between the

Director of Personnel and Administration or the Director of Intelligence and

the technical services, strongly opposed direct dealings between the technical

services and the Director of Organization and Training on manpower allocations

or the Comptroller on budget requests. He insisted that the Director of Logistics

should be responsible for allocating manpower and appropriations among the

several technical services. The services objected to being cut off

from direct

- [190]

- contact with other General Staff agencies because of the tremendous amount

of daily business they had to conduct with them.44

-

- On 18 October 1948 Secretary Royall approved the revised Phase I proposals

with one more major change. He thought there was insufficient civilian control

over the business and financial side of the Department of the Army and requested

amending the draft circular to stress the civilian secretariat's supervisory

role over Army logistics.45

-

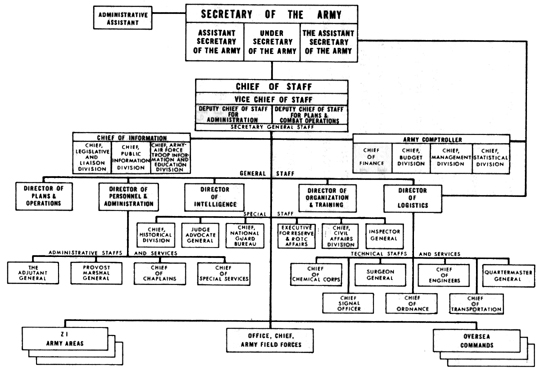

- Phase I of the Johnston plan was announced in Department of the Army Circular

342, 1 November 1948, effective 14 November 1948. (Chart 17) The three principal

changes from the Johnston plan were (1) the creation of two Deputy Chiefs

of Staff, one for plans and combat operations and another for administration,

(2) spelling out in greater detail the role of the Assistant Secretary of

the Army in procurement and industrial relations in accordance with Secretary

Royall's request, and (3) an attempt to delineate more precisely the authority

of the Director of Logistics over the technical services in their relations

with

other Army staff agencies.

-

- Minor changes resulted in retaining both the judge Advocate General and

the Historical Division as independent special staff agencies reporting directly

to the Chief of Staff instead of placing the former under the Director of

Personnel and Administration and the latter under The Adjutant General.

-

- Circular 342 stressed the temporary nature of the reorganization, pending

development of a "more effective organization." At the same time

it stressed that the only changes being made concerning the technical and

administrative services were to place them "under the direction and control"

of the Directors of Logistics and of Personnel and Administration so far as

their relations with the rest of the Army staff were concerned. "The

- [191]

- ORGANIZATION OF THE DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY, 11 NOVEMBER 1948

-

-

- Source: DA Circular 342, 11 Nov 48.

- [192]

- Directors of Personnel and Administration and Logistics," it said,

were "placed in the direct channel of communication" between the

services, and other Army staff agencies. The two directors would direct and

control the services' operations and activities, while other General Staff

directorates would supervise their functions through them. The Assistant Secretary

of the Army would also exercise some supervision over the services, contacting

them normally through the Directors of Personnel and Administration and of

Logistics.

-

- The precise nature of the control to be exercised by the Directors of Logistics

and Personnel and Administration over the still powerful technical services

remained unclear. They still retained their own personnel, intelligence, and

training functions and their own budgets even if under supervision by the

General Staff. They still continued to command their own field installations.

The question remained how a staff agency like the Directorate of Logistics,

responsible for a single function, could effectively control all the activities

of such multifunctional staff agencies and military commands. As General Larkin

explained it to General Collins some months later: "My first act as Director

of Logistics was to tell the Service Chiefs that, despite their appearing

under me on the chart, I expected them to deal with any appropriate Director

without coming through me." In practice the control of the Director of

Logistics over the technical services was limited to those logistical matters

he had formerly controlled and no more. Under Department of the Army Circular

342 there was no change in the traditional status of the technical services

so far as their supervision and control were concerned.46

-

-

- The Management Division continued to urge action on the later phases of

the reorganization supposedly initiated by Department of the Army Circular

342. After additional investigation Maj. Gen. Edmond H. Leavey, the Comptroller,

recommended in March 1949 the consolidation of training functions under the

Army Field Forces and personnel functions under the Directorate of Personnel

and Administration as

- [193]

- "Phase II" of the Johnston plan. He also wanted further planning

on development of a new system for "program review and analysis,"

the consolidation of materiel functions, and transforming the technical services

into functional staff agencies.

-

- The existing organization, he said, was unsatisfactory because it was "neither

a true functional staff nor a true integrating staff," both of which

Secretary Royall had approved as organizational objectives. Department of

the Army Circular 342 was only a step in the right direction. Revising the

National Defense Act of 1916, as amended, would be another.47

-

- A six-month independent staff study by the management advisory firm of Cresap,

McCormick and Paget, requested by Assistant Secretary Gordon Gray in October

1948, also demonstrated the need for improving further the organization of

the department. Cresap, McCormick and Paget formally submitted its study to

Secretary Royall on 15 April 1949. This and General Leavey's proposals for

further reorganizing the Army staff provoked an angry outburst from Lt. Gen.

Thomas B. Larkin, the new Director of Logistics. As Quartermaster General

he had strongly opposed the Johnston plan, and his new position gave the technical

services a much stronger voice on the Army staff. He complained to General

Leavey that the latter's apparent objective was "a functional organization,

naively assumed as a panacea for all ills real or imaginary." His own

experiences overseas during the war contradicted this idea. "Concrete

results [in improving the operation of the Army's logistics system] will appear

soon if I am not forced to waste the time of my staff probing abstruse theories

as desired by Col. Johnston." The plans of Colonel Johnston's he had

seen "would make top organization still more complex. Much is beyond

my comprehension." As for the Cresap, McCormick and Paget Survey, he

added, "I do not see where it helps to pay outside firms large sums to

tell the Army how to organize." Instead he recommended reducing the Army

staff 30 percent across the board and giving "the organization a chance

to work without constantly proposing changes to try out new theories.

- I do not understand why the Army should persist in harassing

- [194]

- itself with unproved theories instead of devoting full time and attention

to the job in hand." 48

-

- The principal reason for his antagonism toward the Cresap, McCormick and

Paget survey was evident. Like the Johnston plan it recommended functionalizing

the Army staff. Its final report identified several familiar problem areas

in the Department of the Army. The department's activities cost too much money

and required too many people to perform them. Departmental personnel lacked

"cost consciousness." It took too long and was too difficult to

get action or decisions. There was too much duplication and red tape, inadequate

co-ordination, inadequate planning, and too much centralization. The department

had poor procedures for planning, programing, and controlling its operations.

Its organizational structure was weak because its headquarters was divided

into too many separate agencies. At the same time some important functions

were not being performed at all, and responsibility in some instances was

assigned to the wrong agency. Finally, organizational relations between Army

headquarters and field installations were too complicated and confusing.

-

- To economize on manpower and money, to get prompt action, to cut down red

tape and eliminate confusion, to create an organization more nearly like those

of the Navy and Air Force and one suitable for wartime expansion, Cresap,

McCormick and Paget proposed a number of objectives. The Army should integrate

responsibility for long-range, basic planning and separate it from operational

planning and operations themselves which should remain integrated. The Army's

budget structure should parallel its organizational responsibility. The Army

staff should be functionalized by concentrating responsibility for basic functions

in single agencies, reducing the number of independent and autonomous agencies,

and in general grouping related activities. Finally, departmental relations

with the field should follow a single staff and line command channel.

-

- The Cresap, McCormick and Paget proposals were similar to those of General

Somervell and to the Johnston plan. The organization Cresap, McCormick and

Paget proposed for the

- [195]

- top level of the Army staff was similar to those established under Department

of the Army Circular 342, with one important difference. Instead of a Deputy

Chief of Staff for Plans and Combat Operations and one for Administration,

it proposed a functional realignment with plans and programs, including programing

and budgeting, under one deputy and operations and administration under another.

The Army Comptroller would become in effect a third deputy. This

three-deputy

concept, as it later became known in the Army staff, essentially provided

for broad, across the board planning, execution, and control or review and

analysis of performance. It was the type of centralized executive control

engineered earlier at DuPont and General Motors and adopted in the Marshall

reorganization. Following World War II an increasing number of major industries

adopted this approach, notably the Ford Motor Company.49

-

- The Cresap, McCormick and Paget study proposed that the only other Army

staff agencies reporting directly to the Chief of Staff would be The Adjutant

General, Judge Advocate General, the National Guard Bureau, the Executive

for Reserve and ROTC Affairs, the Chief of Information, and the Inspector

General.

-

- The Army's functional staff would consist of nine directorates under the

Deputy Chief of Staff for Administration: War Plans and Operations, Personnel,

Security, Training, the Surgeon General, the Chief Signal Officer, the Chief

of Engineers, Procurement (Ordnance), and Supply (Quartermaster). Finally

the Cresap, McCormick and Paget proposals would make all Army headquarters

agencies purely staff advisers to the Chief of Staff with operating responsibilities

decentralized to the field. The continental armies and other regional commands

would direct all field operations under the staff supervision of the Department

of the Army. 50

-

- Representatives from Cresap, McCormick and Paget explained their proposals

to the Army staff and the technical

- [196]

- service chiefs at two conferences in May and June 1949. The Management Division

also prepared a review of the proposals. The principal objections came from

General Larkin and the technical service chiefs. For the third time in less

than a year they presented united opposition to any proposals for functionalizing

their agencies out of existence. In yet another round robin letter, dated

19 May 1949, the chiefs complained to the Chief of Staff:

-

- The recommendations made in the report revolve about the theory that a functional

breakdown of the Army's mission is a more suitable basis for primary organization

than is a product-technical division. Nowhere in the report is this statement

proven, and nobody has even been able to present to us an example where such

a type of organization has proven effective when applied to an operation of

the magnitude, diversity, and scope of the United States Army.51

-

- The Chief of Ordnance, General Hughes, sent a memorandum to the Comptroller,

General Leavey, wondering whether $25,000 paid to some other firm instead

of the $75,000 paid to Cresap "would not have elicited a more reasoned

report.

-

- The report is basically unsound in its reasoning. It follows the line that

any error in a huge organization can be cured only by a reorganization. I

have been in the Army since 1908 and in the Ordnance Department since 1912.

During that time I have participated in n + 1 reorganizations and have observed

that always afterward the ignorant, the undisciplined, the empire-builders,

the lazy, and the indecisive continued to make the same mistakes they made

prior to the reorganization.

-

- Hughes denied that the "buck-passing" and "red-tape,"

which Cresap, McCormick and Paget asserted were endemic in Army administration,

were caused by faulty organization. The proposals to functionalize procurement

and supply at the level of the Army staff were "both unwise and dangerous."

- [197]

- The only proponents of such a scheme whom I have known to date have been

theorists who have not lived and worked in a Technical Service and have not

become familiar with the complete and absolute necessity for an organization

established on a product basis from research and development through to final

disposition of the end item . . . . I conclude that the report is biased and

unscientific and prepared not to reach a conclusion but to support a conclusion

already in mind.52

-

- In another, more detailed memorandum General Hughes said:

-

- The proposed reorganization would prove thoroughly unsatisfactory at the

management level, the operational level, and the field level. The cost of

the change would be exorbitant in time, money, personnel, efficiency, and

morale. The present approach to merge the Technical Services and the General

Staff into one Army Staff can only result in failure of the Army to accomplish

its mission in a time of emergency . . . .53

-

- All of Cresap's arguments were founded, he said, on the erroneous idea that

a functional organization was more suitable than the existing product-technical

organization of the technical services. The National Defense Act recognized

that the Army had two radically different missions, military operations on

the one hand and procurement and industrial mobilization on the other. Recognizing

this difference the National Defense Act kept them separate by statute. The

Cresap proposal to "scramble" these two different missions was unsupported

by anything but opinion. He saw no need for any basic change in the technical

services currently assigned responsibilities for co-ordination, operation

and direction of research, development, procurement, and supply or for their

command over their own field installations and activities.54

-

- Similar comments came from other technical service chiefs. General Larkin,

on 13 June 1949, endorsed the views of his former colleagues. Based on "a

preconceived idea of functional organization advanced a year ago by the Army

Comptroller," the Cresap, McCormick and Paget plan would abolish the

technical services in all but name. "With them would go

- [198]

- decades of sterling service in peace and war." It would discard proven

ability to perform specialized services for "an entirely unproved theory."

It would diffuse responsibility for individual commodities or services instead

of concentrating them as the existing system did in the technical services.

Larkin questioned the so-called economies to be obtained from adopting the

Cresap, McCormick and Paget recommendations. He objected to the fact that

a civilian organization was prescribing for a purely military organization

instead of the "best professional Army minds." He doubted that any

major reorganization was necessary other than to reduce the size of the Army

staff and improve its quality.

-

- Among General Larkin's specific objections was the proposal to align the

Army budget along organizational or functional lines. Co-ordinating a functional

budget program would be at least as difficult as co-ordinating the existing

budget, he thought, and might result in creating "a more severe financial

strait-jacket." In a final criticism he denied that the technical services

were "autonomous" or independent agencies. They were not. Their

budgets and personnel ceilings were established by higher authority "just

as any other Army agency." In the field their operating agencies were

responsible to the regional Army commanders on a great many matters. The Organization

and Training Division approved their organization, equipment, and functions.

The Director of Personnel and Administration supervised the career management

of their military personnel and Army Field Forces their schools and

training.55

-

- The Management Division in its Final Recommendation to the Chief of Staff

for Action on the Report of the Cresap, McCormick and Paget Survey of the

Department of the Army asserted that the crux of the issue lay in the difficulty

the Army's functionally organized General Staff had in controlling the operations

of the technical services, which individually performed all General Staff

functions for themselves as independent field commands. The Cresap, McCormick

and Paget report, said the Management Division, had firmly asserted that

- [199]

- ...if the parallel, duplicating, and overlapping product-technical or "bureau"

organization is adhered to multiple command channels are unavoidable. If there

are multiple command channels at the top of each there must be a Commanding

General-not a staff officer. It is thus necessary to organize a complex of

headquarters and over this complex to superimpose another headquarters staff.

That is why there is so much "red-tape" and "layering."

. . . If a single command channel is provided and operating functions decentralized

down that chain, all that need remain in Washington is the pure staff coordinating

function and the necessary central control function appropriate to a supreme

headquarters. This is the fundamental argument on which the CMP recommendations

are based. The [other] deficiencies . . . were largely found to stem from

this basic deficiency. It is the main root of the trouble. Any definitive

organizational solution must correct this root evil. CMP recommends a single

command chain.56

-

- The Management Division prepared a synthesis of all comments and criticisms

on the Cresap report with summaries of previous Army staff surveys and the

current reports of the Hoover Commission on Organization of the Executive

Branch of the Government. It concluded that the CMP report and its recommendations

were sound although it suggested some changes. Instead of eliminating Class

II installations, it suggested retaining them until the entire Army supply

system could be reorganized and integrated. In the department it recommended

retaining instead of abolishing the traditional General and Special Staff

system. It would retain rather than eliminate the Director of Logistics to

direct the Ordnance Department, Quartermaster Corps, and Chemical Warfare

Service as the nucleus of a reorganized Army supply system. The Transportation

Corps would retain its current special staff status instead of being merged

with the Quartermaster Corps again. Finally, the Management Division would

leave The Adjutant General's Office within the Directorate of Personnel and

Administration instead of separating its administrative from its personnel

functions.

-

- The Cresap, McCormick and Paget recommendations the Management Division

approved were the consolidation of all personnel offices under the Director

of Personnel and Administration, including the Civilian Personnel Division

in the Under Secretary's Office and the Army's manpower ceiling and

- [200]

- bulk allocation functions; consolidation of all Army staff training functions

under the Director of Organization and Training and all training operations

under the Office, Chief of Army Field Forces; and transfer of the troop basis

and mobilization planning functions to the Deputy Chief of Staff for Plans

and Operations. After consolidating the Army's supply system under the Director

of Logistics it would change the Corps of Engineers on military matters, Signal,

Medical, and Transportation Corps into advisory staff agencies. It would place

the Historical Division under the Chief of Information and retain the civilian

component, National Guard and the Reserve, offices as special staff agencies.

Concerning the Army's financial affairs it recommended that the Army adopt

the Hoover Commission's concept of a "performance budget" reorganized

along regular command lines. The Army Comptroller should be responsible for

integrating the Army's "program review and analysis" functions with

the rank of a third Deputy Chief of Staff. 57

-

- General Haislip, the Vice Chief of Staff and a strong wartime critic of

the Army Service Forces, made the principal decisions to accept, modify, or

reject the Management Division's recommendations. On 23 December the new Chief

of Staff, General J. Lawton Collins, forwarded his recommendations based largely

on those made by General Haislip, to Secretary of the Army Gordon Gray, who

had replaced Mr. Royall, accompanied by a lengthy memorandum of explanation.58

-

- "Reorganization itself," General Collins said, "was not a

panacea for all ills." Economy and efficiency depended more on capable

administration than on organization as such. Many

- [201]

- of the proposals made by Cresap, McCormick and Paget and the Management

Division did not analyze problems in sufficient detail to determine whether

the troubles were those of administration or organization, and where they

lacked sufficient detail or analysis Collins had rejected them. Where he had

to reach decisions arbitrarily or "unilaterally," he said he had

relied heavily upon his own experience and judgment which had taught him that

a proper organization should be based on the sound principles of Field Manual

101-5, the staff officer's handbook.

-

- The internal self-analysis of Army organization over the past two years

had been useful, he said, but there had to be some organizational stability

if the Army was to operate effectively. "The Army can ill afford the

loss of day to day operating efficiency which arises from spasmodic, major

organizational change. Since the termination of World War II, our Army organization

has been in a state of flux. I believe that the time has now come when a measure

of stability must be assured."

-

- General Collins' major recommendations dealt with the number of ZI armies,

the relations between Class II installations and the Army commands, the degree

of centralized control over the Army supply system, the role of the Army Comptroller,

the suitability of the General and Special Staff system for directing the

Army, the assignment of personnel to the General Staff, and the further decentralization

of operations from the General Staff to Army Field Forces, the Army commanders,

and the chiefs of the technical and administrative services.

-

- Collins recommended retaining the existing number of six ZI armies and the

Military District of Washington and rejected any substantial changes in the

existing Class II command structure. Based on the results of Operation TACT,

he suggested adding further housekeeping functions for Class II installations

to the responsibilities of the ZI Army commanders. He would also increase

their responsibilities for local operations and activities confined to a single

Army area. In continuing to exempt Class II functions from ZI Army control,

General Collins had followed the judgment of General Larkin and the chiefs

of the technical services.

-

- He thought the existing Directorate of Logistics could be

- [202]

- expanded in the event of war into a consolidated service force or materiel

command without any major reorganization. He asserted the technical and administrative

services had functioned successfully and effectively during two world wars,

and he could see no reason for any major change in their structure or missions.

The Director of Logistics was directed to study the possibility, however,

of reducing the number of procurement agencies to three: Quartermaster, Ordnance,

and Signal. He recommended that The Adjutant General's Office absorb the functions

of the Chief of Special Services except for procurement, which the Quartermaster

General should perform. He recommended giving the Comptroller the status and

authority of a Deputy Chief of Staff but not the title.

-

- Collins would retain the General and Special Staff system on the grounds

"that our departmental staff organization should be as analogous as possible"

to Field Manual 101-5, "with which the entire Army is familiar and which

has proven itself so often." This meant returning to a four-division

General Staff with each division headed by an Assistant Chief of Staff. He

recommended consolidating the Organization and Training and the Plans and

Operations Divisions into one staff agency and transferring manpower controls

from Organization and Training to G-1 and Army Field Forces. He would initiate

programs for improving the quality of officers assigned to the General Staff

while reducing its numbers by decentralizing more operating responsibilities

to the Chief of Army Field Forces, Army commanders, and the chiefs of the

technical and administrative services.

-

- He rejected the recommendations for consolidating all personnel functions

in a single agency, removing personnel functions from The Adjutant General's

Office, and consolidating all Army training, including the technical services,

into a single agency.59

-

- General Collins' recommendations were another clear vic-

- [203]

- tory for the technical services over functional reformers. A memorandum

of 14 November 1949 from General Larkin to General Haislip shows how much

influence he had on the Chief of Staff's final recommendations. General Larkin,

reviewing once more the history of recent organizational developments affecting

Army logistics, repeated arguments he had made earlier against the Johnston

plan and the Cresap, McCormick and Paget report. The technical services had

performed their missions effectively during war and in peace time. They had

"an esprit de corps, a professional focus and internal and external relationships"

impossible in the "indistinctive," "nebulous" functional

organization proposed to replace them.60

-

- Secretary Gray replied to General

Collins on 9 January 1950, accepting with minor exceptions his recommendations.

He had serious reservations, however, about General Collins' preference for

adhering as closely as possible to the principles of Field Manual 101-5.

-

- The organizational arrangements envisaged by Field Manual 101-5 have indeed

admirably met the exacting demands of combat operations and I do not question

their suitability. But we are here concerned with different problems and different

requirements. To me the differences are striking, and it does not seem logical

that the organizational design of the headquarters of an Army Group, an Army

Corps or Division should closely resemble the organizational design of the

D/A.

-

- He listed dissimilarities, such as public and Congressional relations, relations

with other defense and governmental agencies, industrial mobilization, the

military implications of foreign policies, and relations with the Army's civilian

components.

-

- A field army, corps or division, etc. it [sic] is not required to provide

for most of these responsibilities, except in unusual circumstances. And when

such circumstances arise, as for example, during occupation, the organization

of the field headquarters concerned undergoes many changes. There are perhaps,

therefore, persuasive reasons for supposing that the influences which have

twice compelled major reorganizations at the Seat of Government when war was

upon us, flow from the inclination to conform our organization here to that