Chapter IV:

The Eisenhower Reorganization

After World War II the United States abandoned its prewar

isolationism and assumed global responsibilities in international affairs

that vastly increased the commitments of its military establishment and required

new patterns of defense organization. The World War II Army of over eight

million was reduced by mid-1947 to approximately one million (including the

Army Air Forces), but was still five times greater than the Army of the 1930s.

This force was no longer deployed solely in the United States and its possessions

but was widely dispersed in occupation and other duties in Europe and Asia.

The Army could no longer be viewed as a virtually independent. entity but

as one interrelated in complex patterns with the other elements in the defense

establishment, including after 1947 a separate Air Force. The pace of technological

advance illustrated most dramatically by the appearance of the first atomic

bomb at the end of the war introduced further complications into the management

of defense and Army affairs. Between 1945 and 1950 Congress and the Executive

Branch wrestled with the problems of establishing a new defense organization

to fit the new circumstances. Within the Army itself these events produced

crosscurrents of opinion that led to a new phase in the long struggle between

rationalists and traditionalists over the nature of the organization of the

department.

General of the Army George C. Marshall repeatedly asserted

he could not have "run the war" without having radically reorganized

the department to provide centralized, unified control through decentralized

responsibility for administration. The essential features of his reorganization,

he strongly advised, should be retained after the war and the armed services

[129]

should be unified or integrated along the same lines.1

This

approach was preferable to continuing the unsatisfactory extemporaneous wartime

organization of the joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) . The JCS operated on the

traditional committee system, which, Marshall told Congress, made the development

of balanced national defense policies and effective control over the armed

services impossible. "Committees," he said, "are at best cumbersome

agencies." They reached agreement only after interminable delay. Their

decisions represented compromises among the competing interests of individual

agencies rather than rational calculations based on the interests of the nation

as a whole. They wasted time, men, money, and matériel.2

Marshall's basic proposition was to integrate the services

into a single department along the same lines as his wartime organization

of the Army. A civilian secretary would be responsible for the nonmilitary

administration of the services, a role similar to Secretary Stimson's during

the war. Under him would be a single Chief of Staff for the Armed Forces directing

the military activities of four operating commands: the Army, Navy, Air Forces,

and a Common Supply and Hospitalization Service patterned after Army Service

Forces. Overseas theater commanders would report directly to the Chief of

Staff.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff would continue as a top-level planning

and co-ordinating staff, with no administrative responsibilities, under a

"Chief of Staff to the President" like Fleet Admiral William D.

Leahy. The new Chief of Staff would present the views of the JCS to the President

instead of the reverse as Admiral Leahy had done. The JCS would also continue

to report directly to the President rather than through the civilian secretary.

Its vital function would be to recommend to the President military programs

which integrated military strategy and policy with the budgets required to

support them.

National military policies should be balanced against the

resources available to meet them, Marshall insisted. Otherwise the services

would find themselves again unable to carry out their assigned responsibilities.

He also sought to prevent the services from bypassing the Chief of Staff and

the Secretary as the technical services had done in obtaining

their own funds

[130]

directly from Congress. Thus General Marshall's plan also

involved a radical reorganization of the nation's defense budgets along rational

lines.3

Even before Pearl Harbor General Marshall realized the importance

of planning ahead to avoid the kind of chaotic demobilization which followed

World War I. On 18 November 1941 he recalled to active duty Brig. Gen. John

McAuley Palmer, with whom he had served under Pershing, as his personal adviser

on the postwar organization of the Army. On 24 June 1942 he also appointed

a Post-War Planning Board to advise General Palmer on postwar organization

matters. Its members, including the G1 and G-3, were too preoccupied with

current operating responsibilities to pay much attention to postwar problems.

Eventually they agreed on the need for a special staff agency that would devote

its entire time to problems of demobilization and postwar planning.

General Marshall then asked General Somervell on 14 April

1943 to initiate preliminary studies on demobilization planning. Accordingly,

General Somervell set up a Project Planning Division within the Office of

the Deputy Commanding General for Service Commands to define the problem in

the light of American experience in World War I and recommend a proper organization

and procedures for dealing with it.

Assisted by General Palmer, the Project Planning Division

submitted a Survey of Demobilization Planning to General Marshall on 18 June

1943. Based on these recommendations, Under Secretary Patterson on 22 July

1943 directed creation of a Special Planning Division as a War Department

Special Staff agency to develop plans for demobilization, universal military

training, a single department of defense, and the postwar organization of

the Army.

Taking over the personnel of ASF's Project Planning Division,

the Special Planning Division (SPD) was. a group of approximately fifty people

under Brig. Gen. William F. Tompkins and later Maj. Gen. Ray E. Porter. Col.

[131]

Gordon E. Textor became deputy director, and General Palmer

continued to serve as adviser. Collectively, they had sufficient rank to command

respect from the other War Department agencies and commands with whom they

had to work. 4

The Special Planning Division's internal organization consisted

of five functional branches: Organization; Personnel and Administration; Service,

Operations, and Transportation; Materiel; and Fiscal. Three other branches,

Legislative and Liaison, Administration, and Research, provided administrative

support.

The Organization Branch developed the War Department's Basic

Plan for the Post-War Military Establishment and the Army's positions on unification

and universal military training along the lines outlined by General Marshall.

The Personnel and Administration Branch prepared the Army's demobilization

program together with the Readjustment Regulations governing its operations.

The Service, Operations, and Transportation Branch, the Fiscal Branch, and

the Materiel Branch, which were combined in 1945 as the Supply and Materiel

Branch, concentrated on planning the Army's postwar supply organization and

industrial demobilization. The Research Branch collected and evaluated reports

from other staff agencies and prepared the division's periodic progress reports.

On military matters the SPD reported to the Chief to Staff and on industrial

matters to Under Secretary Patterson.5

The Special Planning Division followed traditional Army staff

action procedures. It assigned problems for investigation to appropriate staff

agencies or commands, reviewed their reports, and then submitted them for

comment and concurrence to all interested agencies. After adjusting conflicting

views, SPD submitted the final results to the General Staff, General Marshall,

Under Secretary Patterson, and Secretary Stimson for

[132]

approval. In September 1945, two and a half years after it

had begun operations, the SPD had completed action on about one half of the

150 problems initially assigned. Those remaining generally concerned Army

supply and administrative organization, the subject of heated debate between

ASF and the Army staff. While the Special Planning Division continued to exist

until May 1946, the Under Secretary's Office absorbed the functions of the

Materiel Branch in. September 1945, while the Patch-Simpson Board on the Postwar

Organization of the Army removed that function from the Organization Branch.6

A primary responsibility of the Special Planning Division

was the detailed planning required to carry out General Marshall's postwar

programs for unification of the armed services, universal military training

(UMT), and the postwar organization of the Army. Before any detailed planning

could be undertaken the SPD and the Army staff had to agree on certain operating

assumptions concerning the nature of the postwar world and likely U.S. military

commitments in that period.

The SPD's Basic Plan for the Post-War Military Establishment,

dated 9 November 1945, assumed for planning purposes the existence of some

kind of international security organization like the proposed United Nations

"controlled by major powers," including the United States. Control

over the sea and air "throughout the world" would be the "primary

responsibility of the major powers, each power having primary control in its

own strategic areas." Finally, the "total power" of the world

organization would be sufficient to deter any aggressor, including one of

the major powers.

Within this framework the SPD and the Army staff made the

following planning assumptions concerning the nature of the next war. The

United States would have recognized the possibility of such a war at least

a year ahead and have undertaken some military preparations. The conflict

would be a "total war" begun without any declaration of war by an

"all-out" attack on the United States as the initial objective of

the aggressors. The war would last five years, and the United States would

be without major Allies for the first eighteen months.

[133]

Additional assumptions were that the United States would

be able to mobilize 4,500,000 men within one year and that the maximum rate

of production during the war would be that of 1943.

Given these assumptions the armed services should be strong

enough to maintain "the security of the continental United States during

the initial phases of mobilization," "support such international

obligations as the United States may assume," hold those "strategic

bases" required "to ensure our use of vital sea and air routes,"

and be able to expand rapidly through partial to complete mobilization.7

In summary, Army plans assumed the next war would be much

like the last, complete with another Pearl Harbor. Basing them on these assumptions

the Army submitted two versions of General Marshall's unification proposals

to Congress. General McNarney introduced the first version to a special House

Committee on Post-War Military Policy headed by Congressman Clifton A. Woodrum,

Democrat of Virginia, on 25 April 1944. The committee took no action because

of strong Navy opposition. A JCS Special Committee for Reorganization of National

Defense recommended certain changes in the Marshall-McNarney plan in the summer

of 1945. As a result the Army staff modified its earlier proposals, and Lt.

Gen. J. Lawton Collins, Deputy Commanding General and Chief of Staff, Army

Ground Forces, presented the second and final War Department proposals, the

Marshall-Collins plan, to the Senate Military Affairs Committee on 80 October

1945.

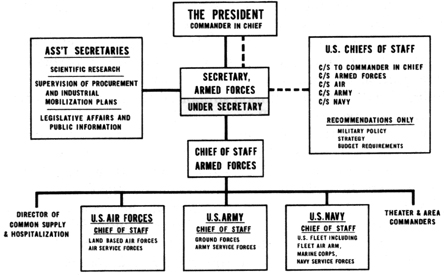

The basic features of these two plans followed General Marshall's

concept of unification. They also paralleled Marshall's wartime organization.

The new Secretary of the Armed Forces and his principal assistants would be

responsible for those nonmilitary functions Secretary Stimson and his staff

had handled-research and development, procurement, industrial mobilization,

legislative liaison, and public information. (Chart 11) The services together

with a separate Directorate of Common Supply would be autonomous operating

agencies like the Army Ground Forces, Air Forces, and Service Forces reporting

directly to the Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces rather than

[134]

THE MARS HALL-COLLINS PLAN FOR A UNIFIED DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMED FORCES,

19 OCTOBER 1945

Source: Thomas Committee Unification Hearing, p. 156.

through separate civilian secretaries. The Secretary of Defense

would supervise and direct the services through an integrated functional staff

rather than through a more traditional, service-oriented one. The Joint Chiefs

of Staff would be responsible for co-ordinating policies and programs with

the men and resources required, much as OPD had done for the Army during the

war.

Both General Marshall and General Collins in their Congressional

testimony stressed the integrating and co-ordinating functions of the JCS

more than any other feature of the Army's proposals. One feature they did

not discuss was the assignment of land-based air forces to the Air Forces

without any reference to land-based Marine Corps aviation. The omission was

significant because the role of Marine Corps aviation caused the most bitter

interservice disputes in the ensuing Congressional battles on unification.8

The second part of Marshall's postwar program which the Special

Planning Division worked on was universal military training. From the

beginning it was hobbled by a renewal of

[135]

the old Army dispute over whether the United States should

rely for its defense upon the Uptonian concept of a large standing army or

continue to rely upon a trained militia. Remembering that Congress had twice

rejected the Uptonian approach in the National Defense Act of 1916 and again

in 1920, Marshall did not believe Congress would support a permanent peacetime

army larger than 275,000. Consequently he, General Palmer, and Secretary Stimson

supported the traditional policy of relying upon trained Reserves against

the determined opposition of practically the entire Army staff which favored

the Uptonian view. Marshall proposed the UMT program as the most practicable

means of providing a trained militia. As developed by the SPD in agreement

with the Navy, the UMT plan proposed that every able-bodied male between seventeen

and twenty would receive a year's military training followed by five years

of service in the Organized Reserves or National Guard. UMT would be for training

only, and trainees would not be considered part of the armed forces available

for normal peacetime military operations. The peacetime military establishment

would be "no larger than necessary to discharge peacetime responsibilities"

because UMT would provide the forces needed in the event of a national emergency.

Paragraph II of War Department Circular 347 of 27 August

1944 instructed the War Department to follow the traditional American policy

of relying upon trained National Guard and Reserve forces as the basis for

its postwar planning. Despite General Marshall's directive the Army staff

continued to oppose reliance upon the militia right down to his retirement

in November 1945. A War Department Special Committee on the Strength of the

Permanent Military Establishment appointed in August 1945 under Brig. Gen.

William W. Bessell, Jr., initially proposed a million-man army. This figure

included the Air Staff's proposal for a seventy-group air force. Marshall

informed the Bessell Board that this total was unrealistic because Congress

would not provide the funds needed to maintain such a large force and because

without universal military training or the draft the Army could not obtain

the volunteers needed. The board then revised its estimates downward to about

550,000, but General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower, who succeeded Marshall

as Chief of Staff, rejected this

[136]

figure as inadequate. The cold war soon made these internal

Army disputes academic, while UMT was pigeonholed in Congress.9

The last part of Marshall's postwar program tackled by the

Special Planning Division was the future organization of the War Department

and Army. By the end of the war the Army staff had been unable to reach agreement

on this subject, and the SPD assumed "for planning purposes only"

the continued existence of the "Air Forces, Ground Fqrces, and Service

Forces." At this point the Board of Officers on the Reorganization of

the War Department under Lt. Gen. Alexander M. Patch took over this function

from SPD.

The War Department's basic plan assumed that the Air Forces

would be organized into "a headquarters and such Air Forces, Commands

and other elements as may be provided," that the Ground Forces would

similarly be organized into a "headquarters and such Army and Corps headquarters

and separate commands as may be provided," but concerning the Service

Forces it assumed only that they would be "organized administratively

to support the requirements of the Ground and Air Forces." The omission

of any reference to ASF headquarters was deliberate. The postwar organization

of the Army was to be heavily influenced by the bitter opposition provoked

within the Army staff by General Somervell's wartime proposals to reorganize

the Army's supply and administrative systems along functional lines.10

General Somervell and his industrial management experts in

the Control Division under General Robinson made four

[137]

proposals between 1948 and 1946 aimed at rationalizing the

Army's supply and administrative systems.

The first, made in both April and June 1943, would have established

General Somervell formally as the Chief of Staff's principal adviser on supply

and administration, replacing G-1 and G-4. The opposition of the Army staff,

including OPD, killed this plan. The next three proposals made in the fall

of 1948, the summer of 1944, and late 1945, all would have "functionalized"

the technical and administrative services out of existence as autonomous commands.

Secretary Stimson himself vetoed the first, Under Secretary Patterson the

second, while the third effort, disguised as logistics "Lessons Learned"

in World War II, remained buried in the files of ASF and its successor agencies.

General Somervell was not satisfied with his informal status

as General Marshall's chief adviser on supply and administration. With his

passion for organizational tidiness and clear-cut command channels he wanted

to make this position formal, resurrecting the dual position held by General

Goethals in World War I. In his view there was no need for G-1, G-4, or the

Logistics Division of OPD, and in April and June 1943 he proposed to abolish

them. His argument was that separating operations from planning was impractical.

G-1 and G-4 were unnecessary because ASF was actually performing their functions.

"The enforcement of policy inevitably tends to become the actual operation

of that policy with all of the extra administrative detail and personnel required

for an additional agency to do the work of another." 11

Going one step

further Somervell argued that the Operations Division ought to absorb G-3

functions, leaving as the General Staff only OPD and the Military Intelligence

Service, both essentially operating agencies. Thus the General Staff would

be eliminated as a coordinating or supervising agency. Summarizing this concept

several years later as one of the lessons learned in the war, General Robinson

wrote:

The commander of the logistic agency must be recognized as

the adviser to and staff ofcer for the Chief of Staff on logistic matters.

The General Staff should be a small body of direct advisers

and assist-

[138]

ants to the Chief of Staff, concentrating its attention primarily

on strategic planning and the direction of military operations. The Chief

of Staff and the General Staff should not be burdened with the coordination

and direction of administrative and supply activities, procedures and

systems.12

Without commenting one way or another, General Marshall submitted

these proposals to the General Staff and other interested agencies that almost

unanimously opposed them. G-1 and G-4 remained, and their staffs and functions

actually increased during the rest of the war, probably as a reaction to General

Somervell's projected plans. 13

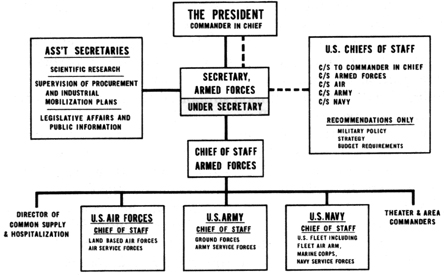

General Somervell's next campaign was to integrate the operations

of the technical services along functional lines. (Chart 12) This was the

heart of a proposed wholesale reorganization of the Army Service Forces from

the top down known as the Long-Range Organization Plan for the ASF prepared

in the Control Division. The reorganization of ASF headquarters actually carried

out was that in November 1943, which centered on a Directorate of Plans and

Operations. The headquarters of the several service commands were to be realigned

similarly.

The offices of the chiefs of the technical services were

also to be reorganized on parallel lines as the first step toward their complete

functional ization. In the last stage they would be divested of their field

commands and combined with the staff of ASF headquarters into a single functional

staff for procurement, supply, personnel, administration, fiscal, medical,

utilities, transportation, and communications. The field activities of the

technical services were to be transferred to six instead of nine service commands

and their various field operating zones realigned to correspond to the latters'

geographical boundaries. There would be no more Class IV installations or

"exempted stations" except for certain special installations such

as ports

[139]

LONG-RANGE ORGANIZATION PLAN FOR ARMY SERVICE FORCES, OCTOBER-NOVEMBER

1943

Source: Control Division, ASF, Report No. 56, OCt-Nov 43. Dir, SSP,

"Briefing Book: "The Pros and Cons of a Logistic Command,"

Feb-Apr 48.

[140]

of embarkation and proving grounds which would report directly

to ASF headquarters in Washington.14

General Marshall and General McNarney supported General Somervell's

plan, which they both recognized would wipe out the traditional technical

and administrative services. Secretary Stimson, Under Secretary Patterson,

and Mr. McCloy, on the other hand, realized the opposition and resentment

this would provoke among the technical services. The Secretary doubted that

the game would be worth the candle. General Somervell, "whose strong

point is not judicial poise," the Secretary confided in his diary, reminded

him in many ways of General Wood, especially "in his temperament."

He recalled for General Marshall how Wood's efforts to reform the Army back

in 1911-12 aroused such opposition that Stimson had all he could do to prevent

Congress from abolishing the position of Chief of Staff altogether. General

Marshall, whose experiences under General Pershing had taught him the political

power of the technical service chiefs, yielded at this point to the Secretary's

judgment. General McNarney, although overruled, continued to believe "washing

out" the technical services was a sensible idea.15

As if to underline Secretary Stimson's arguments, opponents

of General Somervell's plan within the Army leaked information about it to

the press, which in turn stirred up a hornet's nest in Congress, just as the

Secretary feared it would.16

One of those most strongly opposed to functionalization

was the resourceful Chief of Ordnance, General Campbell, who complained to

Bernard Baruch, a member of his Industrial Advisory Committee. Mr. Baruch

protested to President Roosevelt personally and also wrote Mr. Stimson. The

Secretary in reply said: "I stopped the foolish proposal in respect to

the Technical Services when it first reached me several weeks ago." 17

General Somervell was abroad on an important political mission for General

Marshall during all these events. Surveying the

[141]

damage on his return, he ordered all papers and studies on

the whole project destroyed.18

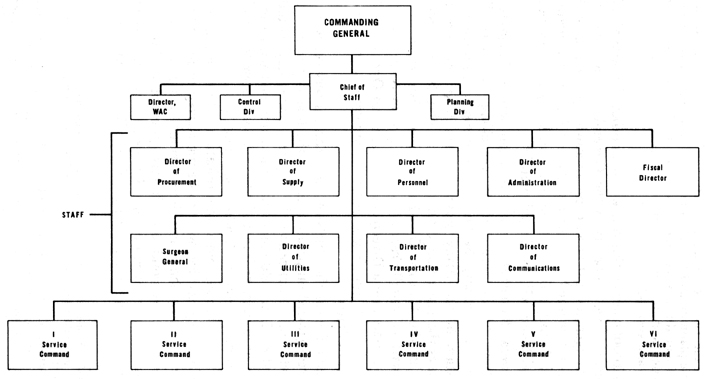

Undaunted, General Somervell and the Control Division continued

to press for consideration of their plan to functionalize the technical services.

Responding to a request from the Special Planning Division, the Control Division

on 15 July 1944 resubmitted a combined and revised edition of its earlier

proposals .as a Plan for Post-War Organization of the Army Service Forces.

This included its recommendations to confine the General Staff to strategic

planning and the direction of military operations, to make the Commanding

General, ASF, the Chief of Staff's adviser on supply and administration, and

to create a "single, unified agency for all supply and administrative

services for the Army," including the AAF. In addition to abolishing

G-1 and G-4, the report requested restoration of the War Department's budget

function to the ASF because "all fiscal operations should be placed in

one organizational unit," suggested abolition of the New Developments

Division because it duplicated and complicated the research and development

work of ASF headquarters, and asked that the civilian personnel functions

be transferred from the Office of the Secretary to ASF on similar grounds.

Complaining that the AAF was attempting to make itself completely

"self-contained and independent," the report recommended that ASF

should be responsible for most AAF housekeeping functions and for "the

procurement and supply of all items of supply and equipment, including those

peculiar to Army Air Forces. There is no more reason for making the present

exception for aircraft than for making an exception for tanks or radio or

artillery." Under the ASF there would also be one transportation system

for land, sea, and air, except for elements organic to tactical units.

[142]

ASF's mission, the Control Division argued, was "to

integrate in an economical manner all the supply, administrative, and

service functions of the Army." The continued existence in law of the

technical and administrative services as semiautonomous agencies was inconsistent

with this principle, and the National Defense Act should be amended accordingly.

The law ought only to provide for the principal officers of the department:

the Secretary, Under Secretary, and assistant secretaries, the Chief of Staff

and the General Staff, and the three major commands. The detailed subordinate

organization of the department should be left "for administrative determination"

by the Secretary of War. Similarly the commissioning of officers in the separate

arms and services was inconsistent with the organization of the Army into

three major commands. The law should provide for commissioning and assigning

all officers only in the "Army of the United States," and branch

insignia should be abolished.

The report again recommended abolishing the distinction between

Class I and Class IV installations and the adoption of a single organizational

pattern along functional lines under the service commands for all field activities

within the zone of interior.

The chiefs of the technical and administrative services would

continue to exist in this plan, unlike the previous one, but they would serve

simply as a functional staff and command no field agencies. Under this scheme,

the Office of the Chief of Ordnance, organized internally along commodity

lines, would be the staff agency responsible for procurement and production,

including research and development and maintenance and repair. (Chart 13)

The Quartermaster General's Office, also organized on a commodity basis,

would be responsible for storage, distribution, and issuance of all supplies

and equipment. The Office of the Chief of Engineers would be responsible for

all construction, real property (including national cemeteries), mapping,

and its traditional "civil functions," the Office of the Surgeon

General for all medical activities, the Office of the Chief of Transportation

for all types of transportation and the Army postal system, and the Office

of the Chief Signal Officer for signal communications and for photographic

[143]

POSTWAR ORGANIZATION, ARMY SERVICE FORCES, PROPOSED BY ASF HEADQUARTERS,

15 JULY 1944

(1) Primary duty of co-ordinating all planining and programing.

(2) Number of service commands would vary from time to time depending upon

workload.

(3) Staff organization parallels that of headquarters.

Source: Control Division, ASF, 020 Organization, 1944 file, Organization

of the Army Service Forces in the Post War Military Establishment,

Headquarters, ASF, 15 July 1944.

[144]

and motion picture services. The only office abolished would

be the Chief Chemical Officer.

The Judge Advocate General would be responsible for all legal

activities currently performed in the technical services. The Office of the

Provost Marshal General would be assigned responsibility for civil defense

in addition to its other duties. All fiscal activities of the technical services

would be transferred to the Office of the Chief of Finance, and The Adjutant

General's Office would be responsible for all personnel functions, publications

and records, personnel services, and labor relations. The National Guard Bureau

and the Office of the Executive for Reserve and ROTC Affairs would be abolished

and their functions assigned to the ASF Chief of Military Training and to

The Adjutant General.

The Control Division advocated organizing the supply and

administrative services of overseas theaters and commands on the same pattern

as the ASF and the service commands. All supply and service troops not organic

to a subordinate tactical unit would be placed under a single service of supply

whose commander would bear the same relation to the theater commander as General

Somervell did to General Marshall. Within tactical units from armies down

to regiments a single service troop commander would replace the special staff,

G-1 and G-4.

The Control Division concluded its report with a recommendation

that in any proposed single department of the armed services there should

be a separate Service Forces agency for common administration, supply, and

service activities.

These "reforms" were so radical and comprehensive

that they affected nearly every agency in the Army, the Navy, and the Air

Forces. To the extent that they were known throughout the Army they added

fuel to the existing animosity toward the ASK Under Secretary Patterson vetoed

the plan, saying that roles and missions of the technical services and the

service commands should be left unchanged. Consequently the proposal was not

submitted to the Special Planning Division, but General Robinson presented

a copy of it to the Patch Board a year later as part of his testimony.19

[145]

The final proposals developed in the Control Division for

inclusion as Chapter 16 of General Somervell's final report retained the same

basic organization proposed earlier with the following exceptions. The Chief

of Ordnance and the Quartermaster General would administer and control major

field activities including arsenals, large procurement and storage depots,

and major maintenance and repair facilities. The plan developed in some detail

the procedures by which the Army's supply system would operate under this

pattern of organization. Second, it proposed separate seacoast commands to

control ports of embarkation, holding and reconsignment points, distribution

depots, staging areas, and personnel replacement centers. Finally the report

offered a detailed war mobilization organization plan for the federal government

in which an Allocations Board would ration scarce resources, production facilities,

labor, and transportation among government agencies in a manner similar to

the Controlled Materials Plan of World War II.

These proposals, submitted to General Somervell in November

1945, were deleted from his final report, which was published in 1948 as "Logistics

in World War II: The Final Report of the Commanding General, Army Service

Forces," because the War Department reorganization of May 1946 and the

National Security Act of 1947 had overtaken them.20

The Army staff's opposition to continuing Army Service Forces

after the war stemmed from animosity engendered by General Brehon B. Somervell's

aggressiveness and the huge size of his headquarters as well as from opposition

to his various reorganization proposals. The opportunity to abolish ASF came

with General Marshall's retirement as Chief of Staff and his replacement by

General Eisenhower after the war. The latter's impending appointment was common

knowledge, at least in the higher echelons of the department, in the summer

of 1945.

In August 1945 Brig. Gen. Henry I. Hodes, Assistant Deputy

Chief of Staff, asked Maj. Gen. Ray E. Porter, Director of the Special Planning

Division, to recommend an appropri-

[146]

ate course of action on reorganizing the department. General

Porter replied by suggesting the appointment of an ad hoc board of high-ranking

officers representing the General Staff and the three major commands to assist

the Special Planning Division in developing a proper organization for the

department and the Army in the immediate postwar period.

Consequently General Thomas T. Handy, the Deputy Chief of

Staff on 30 August created a Board of Officers on the Reorganization of the

War Department, headed first by General Patch, and, after his death in November,

by Lt. Gen. William H. Simpson. Handy made the board itself rather than SPD

responsible for recommending a suitable organization, and appointed representatives

from the technical services instead of the three major commands, flatly rejecting

a personal request from General Somervell to appoint General Robinson. The

board included one representative each from OPD and SPD, the Chief Signal

Officer, and a veteran Ordnance organization and management expert, Maj. Gen.

Charles T. Harris, Jr. As head of a blue-ribbon Committee on the Post-War

Organization of the Ordnance Department Harris had recommended continuing

the department's division along commodity lines with responsibility "from

design to obsolescence" assigned on this basis, a concept directly contrary

to General Somervell's functional approach. Of all the members of the Patch-Simpson

Board General Harris was the only one with much experience in organizational

planning. General Patch himself, a blunt combat veteran with no General Staff

experience at all, was frankly baffled by the complex organization, procedures,

and vernacular of the department and relied heavily upon the judgment of his

colleagues. The end result was a committee deliberately weighted against the

Army Service Forces.21

The Patch Board based its recommendations on approxi-

[147]

mately seventy-five personal interviews and other communications

from War Department officials, civilian and military, and from General Eisenhower,

already selected as General Marshall's successor, and his European Theater

of Operations staff.

There was a small group of veterans who had been responsible

for the operation of the War Department during the war and who favored continuing

the Marshall organization. Besides General Marshall these included Mr. Patterson,

Mr. Lovett, General Somervell and his staff, Maj. Gen. Russell L. Maxwell,

the G-4, and General Joseph T. McNarney and the three members of his 1942

Reorganization Executive Committee, Brig. Gen. William. K. Harrison, Jr.,

Maj. Gen. Laurence S. Kuter, and Maj. Gen. Otto L. Nelson, Jr. The latter

were questioned primarily on the background and rationale of that reorganization.

General Marshall and - General McNarney emphasized the need to keep the General

Staff out of operations because its procedures delayed action too long. General

McNarney went further and recommended abolishing the technical services entirely.

The second and largest group consisted of representatives

from the technical services and General Eisenhower's staff who opposed ASF

because they regarded a separate supply command as violating the principle

of unity of command. General Handy was only formally neutral on ASF, while

Dr. Bush, Dr. Bowles, and Brig. Gen. William A. Borden were interested primarily

in the future status of the Army's research and development program.22

Knowing General Eisenhower would be the next Chief of Staff,

the Patch Board paid particular attention to a rough plan suggested by him

for dividing the Army staff into a small planning and co-ordinating staff

at the top and a series of functional operating "directorates" for

"technical coordination and supervision." Below these staff elements

the Air Forces, Ground Forces, and the technical services would exercise "command

functions." The board found it difficult to determine just what General

Eisenhower intended by having a planning and co-ordinating staff as well as

a system of directorates, and

[148]

his reference to the former as a "General Staff"

added to the confusion. General McNarney thought Eisenhower's plan was "a

more or less bastard conglomeration of the War Department General Staff and

the Naval System of Bureaus" with two of everything. To him it meant

a return to the prewar organization with the General Staff thoroughly involved

in operational matters, and everything bogging down. Why, he asked, go back

to an "outmoded" organization which was incapable of running the

department in an emergency. The only improvement he could see was that it

did not propose to resurrect the old combat arms chiefs.23

Where General Marshall had insisted that the General Staff

must stay out of operations, the Patch Board came to the opposite conclusion.

In its report it asserted that the "old theory that a staff must limit

itself to broad policy and planning activities has been proved unsound in

this war." It blamed the Marshall reorganization for stripping the General

Staff of its operating functions so that it could not perform its missions

properly. On the other hand, it stated that the General Staff "should

concern itself primarily with matters which must be considered on a War Department

level." Authority to act on all other activities must be "delegated

to the responsible commands." What the General Staff should do when these

commands disagreed among themselves the Patch Board did not say.

The board's proposed reorganization represented a return

to the prewar Pershing pattern with two exceptions. It did not recommend resurrecting

the old combat arms chiefs, and, second, it suggested that all officers should

be commissioned in the Army of the United States rather than by arm or service.

By comparison the Navy had been organized in this manner since 1889.

The Patch Board plan divided the department and the Army

into four echelons: the Office of the Secretary of War, the General and Special

Staffs for staff planning and direction, the administrative and technical

services restored to their prewar autonomy, and an operating level, the Air

Forces, Ground Forces, and Overseas Departments.

[149]

Within the Secretary's Office it proposed a new Assistant

Secretary for Research and Development aided by a civilian advisory council

and a separate Research and Development Division. These proposals reflected

recommendations by Dr. Bush, Dr. Bowles, and General Borden. They had insisted

that research and development must be removed from the control of procurement

and production officials because these two sets of functions were antithetical.

The General Staff divisions were designated Directorates

instead of Assistant Chiefs of Staff, emphasizing that they were not merely

staff advisers but would have "directive authority" as well. The

Operations Division was abolished and its functions parceled out among other

divisions. The control over overseas military operations went to the new Directorate

of Operations and Training. The Strategy and Policy Group became the nucleus

of a revived WPD known as the Plans Division. In restoring the technical services

the Patch Board recommended legislation to make the wartime Transportation

Corps a permanent agency. This was a major change from the interwar period

when transportation was fragmented among several services.

In the zone of the interior (ZI) the board recommended abolishing

the service commands and transferring their installations and housekeeping

functions to four Army commanders under AGE The Military District of Washington

would continue to operate under the direct jurisdiction of the department.

The technical services would be supervised by the new Directorate of Service,

Supply, and Procurement, which would combine G-4 with allied functions of

ASF headquarters. All other ASF administrative functions it would transfer

to appropriate General or Special Staff divisions. "Thus there is no

need for an Army Service Forces headquarters organization," the board

concluded.

Of the combat arms it recommended abolishing the Cavalry

arm and its replacement by an Armored arm and a merger of the Coast Artillery

with the Field Artillery into a single Artillery arm. These changes would

require Congressional action.

The whole organization, the Patch Board asserted, would be

more simple, flexible, and "capable of carrying out the

[150]

Chief of Staff's orders quickly and effectively." It

would have a single "clear-cut," continuous command channel from

top to bottom.24

The report, submitted on 18 October, was circulated among

all interested agencies within the department, among the three major commands,

and overseas. General Eisenhower approved the report, but added that he wanted

to limit procurement to only three or four services. General Marshall, not

wishing to tie his successor's hands, also approved.25

In a vigorous valedictory General Somervell dissented from

the report in principle and in particular. Although largely ignored at the

time, the objections he raised were important. They involved problems either

created or unsolved by the Patch Board and the ensuing reorganization that

would come up again and again in the next two decades.

The Patch Board's recommendations amounted to returning to

the prewar organization of the department, General Somervell asserted, repeating

the errors made after World War I and ignoring the lessons of World War II.

The ideal organization for supply and services was to place all command authority

and responsibility for such operations in one agency which would also act

as the Chief of Staff's adviser on these functions. General Goethals had managed

to develop such an organization which might have been more efficient than

the one ultimately adopted.

The basic organizational pattern might be functional, commodity,

geographical, or staff and line, but major industrial corporations had found

that combining more than two of these patterns resulted in "diffusion

of responsibility, crossing of lines of authority, and general confusion."

The Patch Board proposed to combine three or four different patterns and so

did not provide the same simple, clear-cut command channels it recommended

in the case of AGF. The logic of eliminating

[151]

the chiefs of the combat arms while retaining the chiefs

of the technical services Somervell found hard to follow.

If the Patch Board report were approved, General Somervell

suggested certain specific changes in its recommendations. He thought Congress

should be requested to amend the National Defense Act of 1916 to permit the

Secretary to change the internal organization of the department at his discretion

by administrative regulation.

Second, he objected strongly to the separation of research

and development from procurement and production. Instead he would place the

proposed Assistant Secretary under the authority of the Under Secretary who

was responsible for procurement and the proposed Research and Development

staff agency under the new Directorate of Service, Supply, and Procurement.

During the war, he asserted, it had been difficult to "reconcile conflicts

between the desirability of introducing improvements and the requirements

of mass production. Only if one agency included responsibility for both research

and procurement could the inevitable conflicts, . . . be settled expeditiously

so that deadlocks do not delay or prevent the procurement of adequate weapons

in the necessary quantities..."

Concerning the technical services he said there ought to

be a single command and communications line from the Director of Service,

Supply, and Procurement (SS&P) to all the technical services as there

was from the Director of Personnel. The many functions performed by the technical

services as autonomous commands-personnel, training, intelligence, planning,

and operations as well as supply-should pass through the Director of SS&P

and be co-ordinated by him with other General Staff divisions. Any other organization

would result in confusion, duplication, and overlapping of authority.

He also disagreed with the proposal to make the AGF and AAF

responsible for housekeeping and similar Army-wide services throughout the

zone of the interior. The ZI organization should have a permanency during

emergencies and mobilization which tactical organizations would be unable

to provide. Army Air Forces and Army Ground Forces were primarily tactical

and training organizations and should not be burdened with service and supply

functions not organic to their units. At

[152]

the least all service and supply functions should be assigned

to the technical services under the Director of Service, Supply, and Procurement

26

When General Patch died the board was reconvened in December

under General Simpson to consider changes suggested by various agencies and

to recommend a final reorganization plan. In its report submitted on 28 December

the Simpson Board singled out General Eisenhower's suggestion to limit procurement

to three or four services for special comment. Admitting that there was considerable

duplication among the services in procuring identical items, the Simpson Board

defended the existing conditions with each technical service doing its own

procuring. This was, it said, not an organizational but an administrative

matter to be dealt with by reviewing such cases item by item.

The board made several changes in the original plan. It proposed

placing research and development under the Under Secretary instead of adding

a separate Assistant Secretary, but it retained a separate division on the

General Staff. After protests from the Operations Division against splitting

responsibility for planning and operations the board reduced the number of

directorates by merging the Directorate for Plans with that of Operations

and Training and suggested six rather than four field armies. It also kept

the Civil Affairs Division and a new Historical Division, created on 17 November

1945, as special staff divisions.

These changes were relatively minor. More important was a

shift in emphasis. While the General Staff must operate and at the same time

decentralize operating responsibilities, the board said, it should also act

to eliminate duplication. While there should be greater autonomy for the AAF,

it should be granted without creating unnecessary duplication in supply, service,

and administration. "The only workable procedure for removing and preventing

duplication," it concluded, "lies in the good faith and friendly

collaboration of the using commands and services under the monitorship of

the appropriate General Staff director." Friendship, co-operation, persuasion,

[153]

and teamwork, as General Eisenhower himself said, would solve

such problems.27

On 23 January 1946 General Handy approved a final version

of the Simpson Board report with minor changes. Again, after comments from

the Operations Division the proposed Directorate of Operations, Plans, and

Training was split into separate divisions for Plans and Operations and for

Organization and Training. The former inherited OPD's principal responsibility

for integrating plans and operations. At the same time, General Handy appointed

five directors for the new organization. A few days later General Eisenhower

placed General Simpson in charge of executing the Simpson plan with authority

to decide all questions "that cannot be resolved by the interested parties"

and to "monitor and direct" the reorganization itself. 28

Originally set for 1 March the effective date of the reorganization

was postponed three months because certain problems required further study.

One concerned the relations between the Air Forces and the rest of the Army.

Until this matter had been finally settled, the Simpson Board decided not

to request formal legislation making the Transportation Corps a permanent

agency. As a result General Eisenhower found it necessary to reaffirm on 6

February the War Department's intention to request permanent status for the

Transportation Corps at some later date.

Pending Congressional action on a separate air force, the

relationship between the AAF and the AGF was based on the principle of granting

greater autonomy to the AAF. The Air

[154]

Forces would provide 50 percent of the officers assigned

to the General Staff as it theoretically had done under the Marshall reorganization,

while the number of technical and administrative service officers assigned

to the AAF would be decided by mutual agreement between the latter and the

individual technical services concerned. 29

Two attempts were made to establish greater General Staff

control over the technical services than that provided for in the Simpson

plan. General Lutes, General Somervell's successor and the first Director

of Service, Supply, and Procurement, requested that responsibility for supervising

"strictly" technical training be transferred to the Director of

Service, Supply, and Procurement from the Director of Organization and Training.

General Hodes rejected this proposal. The whole purpose of

the reorganization, he said, was to reduce the large War Department overhead.

That was why the Patch and Simpson Boards had recommended abolishing ASF headquarters

and the service commands in the first place. Under the new organization no

functions should be performed at the General Staff level if they could be

delegated to the administrative and technical services. Consequently the Director

of SS&P "must decentralize his activities" to the appropriate

services and "avoid duplicating and overlapping organizations on the

General Staff level." General Eisenhower and the Simpson Board intended

that the training of technical service troops not assigned to tactical air

or ground units should be "under the General Staff supervision of the

Director of Organization and Training." Thus were the basic principles

of the Simpson Board report spelled out in practical terms. Decentralization

and avoiding duplication meant that effective operational control over the

Army's supply and administrative systems would return to the chiefs of the

technical and administrative services. As a practical matter, on technical

training the services would

[155]

also have to report to the Director of SS&P. The General

Staff divisions thus had to deal with eight headquarters instead of one.30

General Simpson reiterated his and General Eisenhower's determination

to restore effective control over operations to the technical services once

more after a committee Simpson had appointed on the Territorial Sub-Division

of the Zone of the Interior proposed to transfer control over the assignment

of officer personnel from the services to the Directorate of Personnel.

The committee, headed by Brig. Gen. George L. Eberle, Acting

Assistant Chief of Staff, G-3, suggested that "personnel functions should

not be vested below the War Department." Following the pattern established

for officer personnel of the combat arms (and by the Navy in 1889) , he proposed

establishing a Central Officers Assignment Division under the Director of

Personnel and Administration to be staffed by senior field grade officers

from each arm and service selected by mutual agreement among the chiefs of

the services, AGF, and AAF. They would advise the Director of Personnel and

Administration on policies and procedures governing the assignment of officers.

They would also direct the assignment of officers, except general offfcers,

"to and from special details and assignments directly under the War Department"

and on the transfer of officers among the arms and services.

General Simpson rejected the Eberle Committee's proposal

that control over personnel not be delegated below the General Staff level.

There would be no changes "in the functions, duties, and powers"

of the chiefs of the technical and administrative services, and they would

continue "to exercise appropriate officer personnel ftfnctions. Further

centralization of authority in the War Department itself, he said, was "entirely

contrary to the principles of the Simpson Board." 31

[156]

The research and development functions of the War Department

received special emphasis on 29 April 1946 when General Eisenhower directed

the establishment, effective 1 May, of the Research and Development Division

as a General Staff division ahead of the general reorganization of the War

Department itself. In addition to his responsibilities as adviser on research

and development matters to the Secretary and the Chief of Staff, the Director

of Research and Development would also be responsible for supervising testing

of new weapons and equipment and for the development of tactical doctrines

governing their employment in the field. This proposal would have centralized

supervision over what became known later as "combat developments"

for the first time in a single General Staff agency.

The following day General Eisenhower issued a policy statement

on Scientific and Technological Resources as Military Assets, which stressed

the importance of research and development to the whole Army. World War II

could not have been won, the general stated, without the expert knowledge

of scientists and industrialists. In the future the Army should promote close

collaboration between the military and civilian scientists, technicians, and

industrial experts. The Army needed the advice of civilians in military planning

as well as for the production of weapons and should contract out to universities

and industry for this assistance. Such experts require "the greatest

possible freedom to carry out their research" with a minimum of administrative

interference and direction. In considering the employment of some industrial

and technological resources "as organic parts of our military structure"

in national emergencies, he thought there was little reason "for duplicating

within the Army an outside organization which by its experience is better

qualified than we are" to do this work.

The Army itself, he said, should separate responsibility

for research and development from "procurement, purchase, storage, and

distribution" functions. Finally, he believed all Army officers should

realize the importance of calling on civilian experts for assistance in military

planning. The more the Army can rely upon outside civilian experts in such

fields, "the more

[157]

energy we have left to devote to strictly military problems

for which there are no outside facilities." 32

Formal proclamation of the Eisenhower reorganization required

Presidential action. Under the First War Powers Act of 1941 (55 U.S. Statutes,

838) President Truman in Executive Order 9722 of 1$ May 1946 amended Executive

Order 1082 of 28 February 1942 by calling for "decentralization"

within the War Department. It "authorized and directed" the Secretary

of War within thirty days "to reassign to such agencies and officers

of the War Department as he may deem appropriate the functions, duties and

powers heretofore assigned to the services of supply command and to the Commanding

General, Services of Supply."

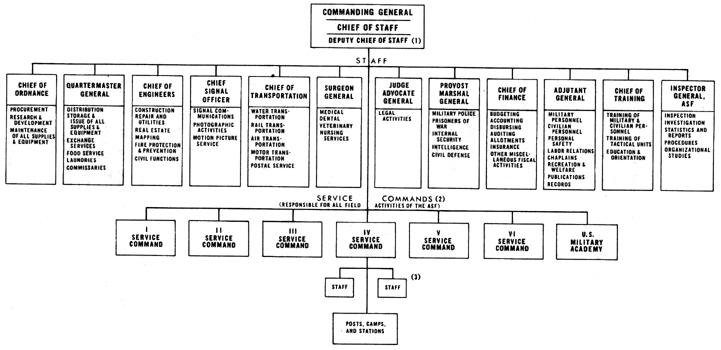

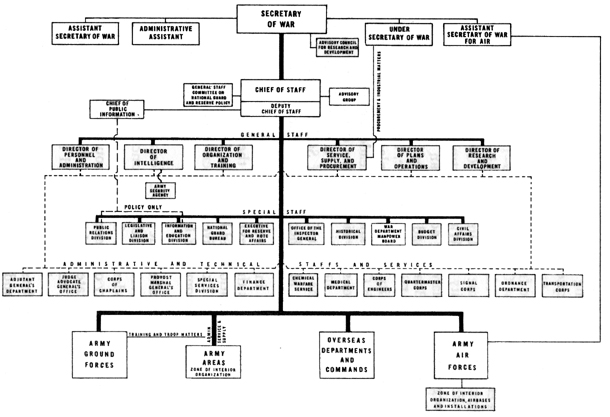

Carrying out this directive War Department Circular 138 of

14 May 1946 prescribed the new departmental organization effective 11 June

1946. (Chart 14) Formally abolishing ASF and the service commands,

it also provided greater autonomy for the AAF. At the General Staff level

greater emphasis on research and development had already been provided for

by removing this function from procurement and supply and making it a separate

General Staff directorate.

The reorganization directive explained that

The necessary degree of efficiency and initiative in the

top echelons of the War Department can be attained only through the aggressive

application of the principle of decentralization. Thus no functions should

be performed at the staff level of the War Department which can be decentralized

to the major commands, the Army areas or the administrative and technical

services without loss of adequate control by the General and Special Staffs.

The General and Special Staffs will "plan, direct, coordinate,

and supervise. They will assist the Chief of Staff in getting things done."

The AAF, it added, should be permitted the maximum degree of autonomy without

creating unwarranted duplication in the areas of supply and administration.

The reorganized General Staff was still functional in nature

with six instead of five divisions, renamed directorates to indicate their

directive as well as their advisory nature. The

[158]

ORGANIZATION OF THE WAR DEPARTMENT, 11 JUNE 1946

Source: War Department Circular No. 138, 14 May 1946.

[159]

changes made in addition to the new Directorate for Research

and Development were the demotion of OPD from its wartime position of a top

co-ordinating staff to theoretically one among equals. The reorganization

directive also called for "adequate means for carrying on . . . intelligence

and counterintelligence activities." In September 1945 a new field command,

the Army Security Agency, was established under the direct supervision of

G-2 and separate from the Military Intelligence Service.

The Assistant Chief of Staff, G-1, became the Director of

Personnel and Administration and G-2 Director of Intelligence. G-3 became

the Director of Organization and Training, with responsibility for War Department

as well as Army-wide organizational planning added as an afterthought because

the Patch-Simpson Board had neglected to consider this subject. G-4 became

the Director of Service, Supply, and Procurement with responsibility for logistical

planning, a function previously shared with OPD and ASF headquarters.

The Operations Division became the Directorate of Plans and

Operations, inheriting OPD's role as the Army's representative with the joint

Chiefs of Staff and its various committees, simply identified as "appropriate

joint agencies" because JCS as yet had no legal status. Except for the

Historical Division created in November 1945, the special staff agencies were

the same as those existing at the end of the war. By that time the Information

and Education Division, National Guard Bureau, and the Executive for Reserve

and ROTC Affairs had been removed from ASF headquarters and made separate

staff agencies.

Having abolished the service commands, the Eisenhower reorganization

transferred their functions to six zones of interior armies under the Commanding

General, AGF, on the principle of unity of command. Ground and Air Force officers

in the United States and the ETO had resented their lack of control over the

resources required to train troops and carry out military operations. The

friction between Ground and Air Forces commanders in the zone of interior

and post and installation commanders under the service commands had been paralleled

in the ETO. For example, Lt. Gen. Walter Bedell Smith, Eisenhower's chief

of staff, had complained that ASF was "a blood-sweating behemoth."

33

[160]

In the Eisenhower reorganization installations or activities

under the traditional command of the chiefs of technical services were exempted

from control by the AGF armies as was the Military District of Washington

which continued to operate directly under the Deputy Chief of Staff. When

technical or administrative service activities were located on installations

under AGF or AAF control, AGF and AAF were to perform approximately forty,

later sixty housekeeping or community service functions for their tenants.

These functions also included responsibility for national cemeteries, induction

centers, counterintelligence, and "action in domestic emergencies."

Finally a separate Replacement and School Command was set up distinct from

the ZI armies themselves and under the Commanding General, Army Ground Forces.

To add geographic to the existing functional decentralization of Army operations

the reorganization directive announced that Headquarters, Army Ground Forces,

would move to Fort Monroe, Virginia, as soon as practicable.

The Eisenhower reorganization was a victory for those favoring

a return to the Pershing organization based on the experiences of a single

operational theater command, such as the AEF in World War I, and Eisenhower's

ETO in World War II. It was a victory of the General Staff and the technicalservices

over the Army Service Forces, of Army Ground Forces and Army Air Forces over

the service commands, and for those insisting on separating research and development

from production and procurement.

The victory of the technical services was the most important.

In destroying ASF, they had re-established the traditional principle of vesting

effective executive control over the Army's supply and service activities

with the bureau chiefs. They had also knocked down an effort by combat arms

officers to place the assignment of officers under the Director of Personnel

and Administration. Internally they kept their own research and development

functions, which remained subordinate to production and procurement almost

by definition since the technical services were themselves commodity or service

commands. They had eliminated the ASF service commands in the zone of the

interior but retained their traditional exemption from control by Army field

commanders.

[161]

The War Department again became a "loose federation

of warring tribes" with "little armies within the Army," as

Mr. Lovett said to the Patch Board. In abolishing ASF and its agencies, the

department could not avoid the management problems which General Somervell

and General Marshall had solved by establishing firm executive control at

the top. The lack of effective control by the functionally oriented General

Staff over the multifunctional agencies and commands they were supposed to

supervise and direct remained an unsolved problem. General Eisenhower's view

was that teamwork, cooperation, and persuasion were better than tight executive

control as a management philosophy. He stated:

Each bureau, each section, each officer in this War Department,

has to be part of a well-coordinated team. Our attitude one toward the other

has to be that of a friend expecting assistance and knowing that he will get

it. If we will always remember that the other fellow is trying to fulfill

our common purpose just as much as each one of us is, I think no more need

to be said about teamwork. But I will insist on having a happy family. I believe

that no successful staff can have any personal enmities existing in it. So

I want to see a big crowd of friends around here.34

[162]

Endnotes

Previous Chapter

Next Chapter

Return to the

Table of Contents