CHAPTER II

Thailand

The decision of Thailand to participate actively in the defense of Vietnam represented a departure from the country's traditional policy of nonintervention. At first this participation was minimal, but as the situation in South Vietnam worsened Thailand reappraised its role in Southeast Asian affairs.

Thailand's interest in increasing the size of its contribution to South Vietnam was in part a desire to assume a more responsible role in the active defense of Southeast Asia; it was also an opportunity to accelerate modernization of the Thai armed forces. Equally important, from the Thai point of view, was the domestic political gain from the visible deployment of a modern air defense system, and the international gain from a stronger voice at the peace table because of Thai participation on the battlefield. For the United States the increased force strength was desirable, but the real significance of the increase was that another Southeast Asian nation was accepting a larger role in the defense of South Vietnam. Some officials in Washington also believed that public acceptance of a further buildup of U.S. forces would be eased as a result of a Thai contribution. Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara was even more specific when he stated that from a political point of view a Thai contribution was almost mandatory.

How determined US efforts were to increase Thai participation can be judged by a message to Thai Prime Minister Kittikachorn Thanom from President Johnson which said in part:

. . . In this situation I must express to you my own deep personal conviction that prospects of peace in Vietnam will be greatly increased in measure that necessary efforts of United States are supported and shared by other nations which share our purposes and our concerns. I am very much aware of and deeply appreciative of steady support you and your Government are providing. The role of your pilots and artillerymen in opposing Communist aggressors in Laos; arrangements for utilization of certain Thai bases by American air units; and . . . steadfast statements which you have made in support of our effort in Southeast Asia are but most outstanding examples of what I have in mind. It is, nevertheless, my hope that Thailand will find ways of

[25]

increasing the scale and scope of its assistance to Vietnam, as a renewed demonstration of Free World determination to work together to repel Communist aggression. It is, of course, for you to weigh and decide what it is practicable for you to do without undermining vital programs designed to thwart Communist designs on Thailand itself . . . .

The first contribution to the Vietnam War effort by Thailand was made on 29 September 1964, when a sixteen-man Royal Thai Air Force contingent arrived in Vietnam to assist in flying and maintaining some of the cargo aircraft operated by the South Vietnamese Air Force. As an adjunct to this program, the Royal Thai Air Force also provided jet aircraft transition training to Vietnamese pilots.

The status of this early mission changed little until the Royal Thai Military Assistance Group, Vietnam, was activated on 17 February 1966 and a Thai Air Force lieutenant colonel was designated as commander. The Royal Thai Air Force contingent then became a subordinate element of the Royal Thai Military Assistance Group, Vietnam.

In March the commander of the Thai contingent asked the US Military Assistance Command to furnish one T-33 jet trainer from its assets to be used for jet transition training previously given South Vietnamese pilots in Thailand. This training program had been suspended the preceding month because of a shortage of T-33's in the Royal Thai Air Force. The Thais had also requested two C-123 aircraft with Royal Thai Air Force markings to allow the Thai contingent to function as an integral unit and to show the Thai flag more prominently in South Vietnam. General Westmoreland replied that jet transition training for Vietnamese pilots was proceeding satisfactorily and that a T-33 could not be spared from MACV resources. He suggested that the aircraft be procured through the Military Assistance Program in Thailand. However, MACV did grant the request for C-123's; the commander of the Pacific Air Force was asked to provide the aircraft. The commander stated that C-123 aircraft were not available from the United States and recommended bringing Thai pilots to South Vietnam to fly two C- 123's owned and maintained by the United States but carrying Thai markings. Arrangements were made to have these pilots in Vietnam not later than 15 July, assuming the Thai crew members could meet the minimum proficiency standards by that time. The crews, consisting of twenty-one men, became operational on 22 July 1966 and were attached to the US 315th Air Comman-

[26]

do Wing for C-123 operations. Five men remained with the Vietnamese Air Force, where they were assigned to fly C-47 aircraft. The Royal Thai Air Force strength in South Vietnam was now twenty-seven.

On 30 December 1966 four newspapers in Bangkok carried front page stories saying that the Thai government was considering the deployment of a battalion combat team of 700 to 800 men to South Vietnam. A favorable response had been expected from the Thai people, but the reality far exceeded the expectation. In Bangkok alone, more than 5,000 men volunteered, including some twenty Buddhist monks and the prime minister's son. One 31-year-old monk, when asked why he was volunteering for military duty, said: "The communists are nearing our home. I have to give up my yellow robe to fight them. In that way I serve both my country and my religion."

On the morning of 3 January 1967 'the Thai government made official a speculation that had appeared in the press several days earlier; it announced that a reinforced Thai battalion would be sent to fight in South Vietnam. The following reasons for this decision were given:

Thailand is situated near Vietnam and it will be the next target of communists, as they have already proclaimed. This is why Thailand realizes the necessity to send Military units to help oppose communist aggression when it is still at a distance from our country. The government has therefore decided to send a combat unit, one battalion strong, to take an active part in the fighting in South Vietnam in the near future.

This combat unit, which will be composed of nearly 1,000 men, including infantry, heavy artillery, armored cars, and a quartermaster unit will be able to take part in the fighting independently with no need to depend on any other supporting units.

This decision can be said to show far-sightedness in a calm and thorough manner, and it is based on proper military principles. The time has come when we Thais must awake and take action to oppose aggression when it is still at a distance from our country. This being a practical way to reduce danger to the minimum, and to extinguish a fire that has already broken out before it reaches our home. Or it could be said to be the closing of sluice-gates to prevent the water from pouring out in torrents, torrents of red waves that would completely innundate our whole country.

Opposing aggression when it is still at a distance is a practical measure to prevent our own country being turned into a battlefield. It will protect our home from total destruction, and safeguard our crops from any danger threatening. Our people will be able to continue enjoying normal peace and happiness m their daily life with no fear of any hardships, because the battlefield is still far away from our country.

Should we wait until the aggressors reach the gates of our homeland before we take any measures to oppose them, it would be no dif-

[27]

ferent from waiting for a conflagration to spread and reach our house, not taking any action to help put it out. That is why we must take action to help put out this conflagration, even being willing to run any risk to stave off disaster. We must not risk the lives of our people, including babies, or run the risk of having ~ to evacuate them from their homes, causing untold hardship to all the people, everywhere. Food will be scarce and very high-priced.

It is therefore most proper and suitable in every way for us to send combat forces to fight shoulder-to-shoulder with other countries in opposition to aggression, especially at a time when that aggression is still far away from our country. This is a decision reached that is most proper and suitable, when considered from a military, a political and an economic angle.

This decision led to a number of problems for the United States. The first was the amount of logistical support to be given Thailand. The United States assumed that the Thai unit would resemble the one proposed, that is, a group of about 1,000 men, organized into infantry, artillery, armored car, and quartermaster elements, and able to fight independently of other supporting forces. Assurances had been given to the Thai Prime Minister that support for the force would be in addition to support for the Thai forces in Thailand, and would be similar to that given the Thai forces already in South Vietnam. These assurances were an essential part of the Thai decision to deploy additional troops. Thus the Department of Defense authorized service funding support for equipment and facilities used by Thai units in South Vietnam, and for overseas allowances, within the guidelines established for support of the Koreans. Death gratuities were payable by the United States and no undue economic burden was to be imposed on the contributing nation.

With the Thai troop proposal now in motion, the Commander in Chief, Pacific, felt that U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, and US Military Assistance Command, Thailand, should begin discussions on organization, training, equipment, and other support problems pertaining to the deployment of the Thai unit. The US Embassy m Bangkok, however, was of a different mind. The ambassador pointed out that General Westmoreland had asked for a regimental combat team. This request had been seconded by the Commander in Chief, Pacific, the Secretary of State, and the Secretary of Defense. The ambassador said he still hoped to obtain a regimental-size unit but did not believe negotiations had reached the stage where detailed discussions as suggested by the Commander in Chief, Pacific, should be undertaken.

In the meantime representatives of the Vietnam and the Thai military assistance commands met and held discussions

[28]

during the period 27-30 January 1967 on various aspects of the pending deployment. In February the commitment of Thai troops was affirmed and on 13 March the unit began training. The Thai contingent would eventually be located with and under the operational control of the 9th US Infantry Division. On 15 March representatives of the Royal Thai Army and US Military Assistance Command, Thailand, met with the MACV staff to finalize the unit's tables of organization and equipment and allowances. Discussions were, held also on training, equipage, and deployment matters. The approved table of organization and equipment provided for a regimental combat team (minus certain elements) with a strength of 3,307, a 5 percent overstrength. The staff of the regimental combat team, with its augmentation, was capable of conducting field operations and of securing a base camp. Organizationally, the unit consisted of a headquarters company with a communications platoon, an aviation platoon, an M 113 platoon, a psychological operations platoon, a heavy weapons platoon with a machine gun section, and a four-tube 81-mm. mortar section; a service company consisting of a personnel and special services platoon and supply and transport, maintenance, and military police platoons; four rifle companies; a reinforced engineer combat company; a medical company; a cavalry reconnaissance troop of two reconnaissance platoons and an M 113 platoon; and a six-tube 105-mm. howitzer battery. On 18 March the approved table of organization and equipment was signed by representatives of MACV and the Royal Thai Army.

During the above discussions, the Royal Thai Army agreed to equip one of the two authorized M113 platoons with sixteen of the Thai Army's own armored personnel carriers (APC's) provided by the Military Assistance Program; the United States would furnish APC's for the remaining platoon. This was necessary because all APC's scheduled through the fourth quarter of fiscal year 1967 were programed to replace battle losses and fill the cyclic rebuild program for US forces. Subsequently, however, the Royal Thai Army re-evaluated its earlier proposal and decided to deploy only the platoon from headquarters company, which was to be equipped with APC's furnished from US project stocks. The platoon of APC's in the reconnaissance troop would not be deployed with Thai-owned APC's. The Royal Thai Army was agreeable to activating the platoon and using sixteen of its APC's for training, but insisted on picking up sixteen APC's to be supplied upon the platoon's arrival in South Vietnam. If this was not possible, the Thais did not plan to activate the reconnaissance platoon until the United States made a firm commit-

[29]

ment on the availability of the equipment. In view of this circumstance, MACV recommended that an additional sixteen M113's be released from project stocks for training and subsequent deployment with the regiment.

Thai naval assistance was also sought. In the latter part of May, MACV decided that the South Vietnamese Navy would be unable to utilize effectively the motor gunboat (PGM) 107 scheduled for completion in July. It was then recommended that the boat be diverted to the Royal Thai Navy and used as a Free World contribution. The Military Assistance Command, Thailand, objected, however, and preferred that the boat be transferred to the Thai Navy under the Military Assistance Program as a requirement for a later year. Since the Thai Navy was already operating two ships in South Vietnam, a request by the United States to operate a third might be considered inappropriate, particularly m view of the personnel problems confronting the Thais, and the ever-present insurgency threat facing Thailand from the sea. Since Thailand wanted to improve its Navy, the Thais saw no advantage in manning a ship that was not their own. In addition, the US Navy advisory group in Thailand had been continuously stressing the need for modernization of the Thai Navy. To suggest that the Thais contribute another Free World ship would appear contradictory. A more acceptable approach, the US Navy group reasoned, would be to offer the PGM-10'7 as a grant in aid of a future year, and then request Thai assistance in the coastal effort, known as MARKET TIME, by relieving the other PGM when it was due for maintenance and crew rotation in Thailand. This approach would give additional Royal Thai Navy crews training in coastal warfare, increase the prestige of the Thai navy, and meet the continuing need for a Thai presence in South Vietnam. Overtures to the Thai government confirmed the validity of the Navy group's reasoning. The Thais did not wish to man the new PGM-107 as an additional Free World contribution.

Equipment problems were not limited to APC's and PGM's. The original plan of the joint Chiefs of Staff for allocation of the M 16 rifle for the period November 1966 through June 1967 provided 4,000 rifles for the Thais. A phased delivery of 1,000 weapons monthly was to begin in March. In February 1967, however, the Commander in Chief, Pacific, deferred further issue of the M16 rifle to other than US units. Complicating this decision was the fact that the Military Assistance Command, Thailand, had already informed the Royal Thai Army of the original delivery date. Plans had been made to arm the Royal

[30]

Thai Army Volunteer Regiment with the first weapons received, which would have permitted training before deployment. An acceptable alternative would have been to issue M 16's to the Thai regiment after it deployed to South Vietnam, had any weapons been available in Thailand for training; but all M 16 rifles in Thailand were in the hands of infantry and special forces elements already engaged with the insurgents in northeast Thailand. Failure to provide the rifles any later than April would, in the view of the commander of the Thai Military Assistance Command, have repercussions. Aware also of the sensitivity of the Koreans, who were being equipped after other Free World forces, the commander recommended that 900 of the M 16's be authorized to equip the Thai regiment and to support its pre-deployment training. The Commander in Chief, Pacific, concurred and recommended to the joint Chiefs that the 900 rifles be provided from the March production. Even with the special issue of M 16's, it was still necessary to make available another weapon to round out the issue. The logical choice was the M 14, and as a result 900 M 14's with spare parts were requested; two factors, however, dictated against this choice. The first was the demand for this weapon to support the training base in the continental United States, and the second was the fact that the Koreans were equipped with M 1's. Issuing M 14's to the Thais might have political consequences. As a compromise the Thais were issued the M2 carbine.

The liaison arrangements and groundwork for deployment of the Thai unit were completed in July. Following a liaison visit by members of the 9th US Infantry Division, the Royal Thai Army Volunteer Regiment was invited to send liaison men and observers to the 9th Division. As part of the training program in preparation for the scheduled September deployment, five groups of key men from the Thai regiment visited the 9th Infantry Division between 6 and 21 July 1967. Numbering between thirty-four and thirty-eight men, each group was composed of squad leaders, platoon sergeants, platoon leaders, company executive officers, company commanders, and selected staff officers. Each group stayed six days while the men worked with and observed their counterparts. During the period 12 to 14 July, the commander of the Royal Thai Army Volunteer Regiment, accompanied by three staff officers, visited the 9th US Division headquarters.

Debate over the date of deployment of Thai troops to. Vietnam arose when on 5 July the Thai government announced a plan to commit the Royal Thai Army Volunteer Regiment

[31]

against the Communist insurgents in northeast Thailand. The purpose of this move was to build up the regiment's morale and give it combat experience before it went to South Vietnam. At MACV headquarters the plan was viewed with disfavor for several reasons. An operation in northeast Thailand would delay deployment of the regiment in Vietnam from one week to two months. The additional use of the equipment would increase the probability that replacement or extensive maintenance would be necessary prior to deployment. Further, the bulk of the equipment programed for the Thai regiment had been taken from contingency stocks, thus giving the Thais priority over other Free World forces, and in some instances over US forces, in order to insure early deployment of the regiment. The Thai regiment was dependent, moreover, on the 9th Division for logistical support; therefore supplies and equipment scheduled to arrive after 15 August had been ordered to Bearcat where the 9th Division was providing storage and security. Delay in the arrival of the Thai regiment would only further complicate problems attendant in the existing arrangements. Finally, several operations had been planned around the Thai unit and delay would cause cancellation, rescheduling, and extensive replanning. Logistical, training, and operational requirements in South Vietnam had been planned in great detail to accommodate the Thai force on the agreed deployment dates, and any delay in that deployment would result in a waste of efforts and resources.

The weight of these arguments apparently had its effect, for on 27 July the Military Assistance Command, Thailand, reported that the Thai government had canceled its plans to deploy the regiment to the northeastern part of the country.

The deployment of the Royal Thai Army Volunteer Regiment (the Queen's Cobras) to South Vietnam was divided into four phases. Acting as the regiment's quartering party, the engineer company left Bangkok by Royal Thai Navy LST on I I July 1967 and arrived at Newport Army Terminal on 15 July. After unloading its equipment the company traveled by convoy to Bearcat, where it began work on the base camp. The advance party traveled by air to Bearcat on 20 August. The main body of the Queen's Cobras Regiment arrived during the period 19-23 September 1967. The last unit to reach Vietnam was the APC platoon, which had completed its training on 25 September and was airlifted to South Vietnam on 28 November.

Following a series of small unilateral and larger combined operations with Vietnamese units, the Thai regiment launched Operation NARASUAN in October 1967. In this, their first large-

[32]

SOLDIER'S OF THE QUEEN'S COBRAS conduct a search and sweep mission in Phuoc Tho, November 1967.

[33]

scale separate operation, the Thai troops assisted in the pacification of the Nhon Trach District of Bien Hoa Province and killed 145 of the enemy. The Thai soldier was found to be a resourceful and determined fighting man who displayed a great deal of pride in his profession. In addition to participating in combat operations, the Thai units were especially active in civic action projects within their area of responsibility. During Operation NARASUAN the Thais built a hospital, constructed 48 kilometers of new roads, and treated nearly 49,000 civilian patients through their medical units.

Even before all elements of the Royal Thai Volunteer Regiment had arrived in Vietnam, efforts were being made to increase again the size of the Thai contribution. By mid-1967 the Thai government had unilaterally begun consideration of the deployment of additional forces to South Vietnam. On 8 September the Thai government submitted a request for extensive military assistance to the American Embassy at Bangkok. Specific items m the request were related directly to the provision of an additional army force for South Vietnam. The Thai Prime Minister proposed a one-brigade group at a strength of 10,800 men. This organization was to be composed of three infantry battalions, one artillery battalion, one engineer battalion, and other supporting units as required.

In an apparently related move, meanwhile, the chairman of the joint Chiefs had requested the joint General Staff to assess the Thai military situation. This assessment was to include a review of the security situation in Thailand, the military organization, and the ability of the Thais to send additional troops to South Vietnam. In turn the joint General Staff asked for the views of the US Military Assistance Command, Thailand, not later than 20 September 1967 concerning Thai capability. The Joint Staff wished to know how long it would take the Thai government to provide the following troop levels, including necessary supporting troops, to Vietnam: 5,000 troops (approximately two infantry battalions, reinforced); 15,000 troops (approximately four infantry battalions, reinforced); 20,000 or more troops (approximately eight infantry battalions, reinforced, or more). The staff also wanted to know the effect that furnishing troops at each level would have on Thai internal security.

The commander of the US Military Assistance Command, Thailand, Major General Hal D. McCown, concluded that the Royal Thai Army could provide a 5,000-man force without incurring an unacceptable risk to Thailand's internal security. He also believed it possible for Thailand to deploy a 10,000-man

[34]

(two-brigade) force, but the organization, training, and deployment had to be incremental to allow the Royal Thai Army to recover from the deployment of one brigade. In addition, he held that it was impractical to attempt to raise a force of 15,000 or larger because of the probable attrition of the training base. In forming the Royal Thai Army Volunteer Regiment, the Thai Army had drawn 97 percent of its men from existing units, despite the talk of maximizing the use of volunteers. There was every indication that it would follow the same pattern in providing additional forces to South Vietnam. Such a draw-down by the Royal Thai Army of its limited number of trained men was acceptable for a force of 5,000 and marginally acceptable for 10,000, but unacceptable for a force greater than 10,000.

With these comments as a basis, Admiral Sharp went back to the joint Chiefs with his recommendation, which stated:

Present negotiations with the Thais have centered around a deployment of a total 10,000 man force. CINCPAC concurs that this is probably the largest force the Thais could provide without incurring an unacceptable sacrifice in the trained base of the Thai Army and accepting more than undue risk insofar as the Thais' ability to effectively counter the present insurgency.

Concurrently, General Westmoreland was being queried on the ability of the United States to support the various troop levels under consideration. In making this appraisal he assumed that MACV would have to provide maintenance support for all new equipment not in the Thai Army inventory and all backup support above division and brigade level, including direct support units. Other maintenance requirements, such as organic support, including supply distribution, transportation, and service functions, the Thais would handle. In considering the various force levels he envisioned a brigade-size force (5,000 men) that would be attached to a US division for support. As such, the support command of the parent US division would require a minimum augmentation of 50 men to provide for the additional maintenance requirements. Attaching a force of 10,000 men or more to a US division would be impractical. A US support battalion-approximately 600 men, including a headquarters company, a maintenance and support company, a reinforced medical company, and a transportation truck company- would be required for direct support of a Thai force of that size. A Thai force of 15,000 to 20,000 would also need a special support command, including a headquarters company, a medical company, a supply and transport company, and a division maintenance battalion. The estimated strength of this command would be

[35]

1,000 to 1,200 men, requiring an increase in general support troops.

At that time there were no US combat service support units available in Vietnam to meet such requirements. Alternate methods for obtaining additional support units were to readjust forces within approved force ceilings, to increase civilian substitution in military spaces, or to increase the US force ceiling. Any attempt to provide logistical support for the Thai forces within the existing troop ceiling would have to be at the expense of US combat troops. Thus, General Westmoreland considered an increase in the US force ceiling the only practical course of action.

In response to a request by Major General Hirunsiri Cholard, Director of Operations, Royal Thai Army, and with the backing of the American Ambassador in Bangkok, Graham Martin, bilateral discussions began on 3 November 1967 concerning the organization for the Thai add-on force. General Westmoreland gave the following guidance. The missions assigned to the force would be the same type as the missions being assigned to the Royal Thai Army Volunteer Regiment. The area of employment would be generally the same. Reconnaissance elements should be heavy on long-range reconnaissance patrolling. Because of terrain limitations the units should not have tanks. Armored personnel carriers should be limited to the number required to lift the rifle elements of four rifle companies and should not exceed forty-eight. The use of organic medium artillery should be considered; 4.2-inch mortars are not recommended. An organic signal company should be included. The force should consist of at least six battalions of infantry with four companies each. There should be no organic airmobile companies; support will be provided by US aviation units. There should be one engineer company per brigade.

General Westmoreland's interest in whether the force would be two separate brigades or a single force was also brought up in the discussion that followed. On this point General Cholard replied that the guidance from his superiors was emphatic-the force should be a single self-sufficient force with one commander.

The US Ambassador to Thailand, Mr. Martin, established additional guidelines. On 9 November 1967 he advised the Thai government by letter of the action the US government was prepared to take to assist in the deployment of additional Thai troops to South Vietnam and to improve the capability of the Royal Thai armed forces in Thailand. In substance the United States agreed to

[36]

Fully equip and provide logistical support for the forces going to South Vietnam. The equipment would be retained by the Royal Thai government upon final withdrawal of Thai forces from South Vietnam.

Assume the cost of overseas allowance at the rates now paid by the US government to the Royal Thai Army Volunteer Regiment in South Vietnam.

Provide equipment and consumables for rotational training in an amount sufficient to meet the agreed requirements of forces in training for deployment; and undertake the repair and rehabilitation of facilities required for such rotational training. The equipment would be retained by the Royal Thai government following the final withdrawal of Thai forces from South Vietnam.

Assume additional costs associated with the preparation, training, maintenance, equipment transportation, supply and mustering out of the additional forces to be sent to South Vietnam.

Assist in maintaining the capability and in accelerating the modernization of the Royal Thai armed forces-including the additional helicopters and other key items-as well as increase to $75 million both the Military Assistance Program for fiscal year 1968 and the program planning for 1969.

Deploy to Thailand a Hawk battery manned by US personnel to participate in the training of Thai troops to man the battery. Provide the Thai government with equipment for the battery and assume certain costs associated with the battery's deployment.

Further discussion between US Military Assistance Command representatives of Vietnam and Thailand set a force size between 10,598 and 12,200 for consideration. As a result of suggestions from the commander of the US Military Assistance Command, Thailand, General McCown, and General Westmoreland, the Thai representatives began to refer to the add-on force as a division. The Royal Thai Army asked for the following revisions to the US concept for the organization of the division: add a division artillery headquarters; revise the reconnaissance squadron to consist of three platoons of mechanized troops and one long-range reconnaissance platoon (the US concept was one mechanized troop and two reconnaissance platoons); add one antiaircraft battalion with eighteen M42's, organized for a ground security role; add a separate replacement company, which would carry the 5 percent overstrength of the division; upgrade the medical unit from a company to a battalion; and upgrade the support unit from a battalion to a group.

The last two requests were designed to upgrade ranks. General Westmoreland had two exceptions to the proposed revisions: first, three mechanized troops were acceptable but the total number of APC's should not exceed forty-eight; and second,

[37]

MACV would provide the antiaircraft ground security support through each field force. The M42's would not be authorized.

As the conference in Bangkok continued, general agreement was reached on the training and deployment of the Thai division. The first of two increments would comprise 59 percent of the division and consist of one brigade headquarters, three infantry battalions, the engineer battalion minus one company, the reconnaissance squadron minus one mechanized troop, division artillery headquarters, one 105-mm. howitzer battalion, one 155mm. howitzer battery, and necessary support, including a slice of division headquarters. The cadre training was tentatively scheduled to begin on 22 January 1968 with deployment to begin on 15 July 1968. The second increment would then consist of the second brigade headquarters, three infantry battalions, one engineer company, one mechanized troop, the second 105-mm. howitzer battalion, the 155-mm. howitzer battalion minus one battery, and necessary support, including the remainder of the division headquarters. Assuming the dates for the first increment held true, the second increment would begin training on 5 August 1968 and deploy on 27 January 1969.

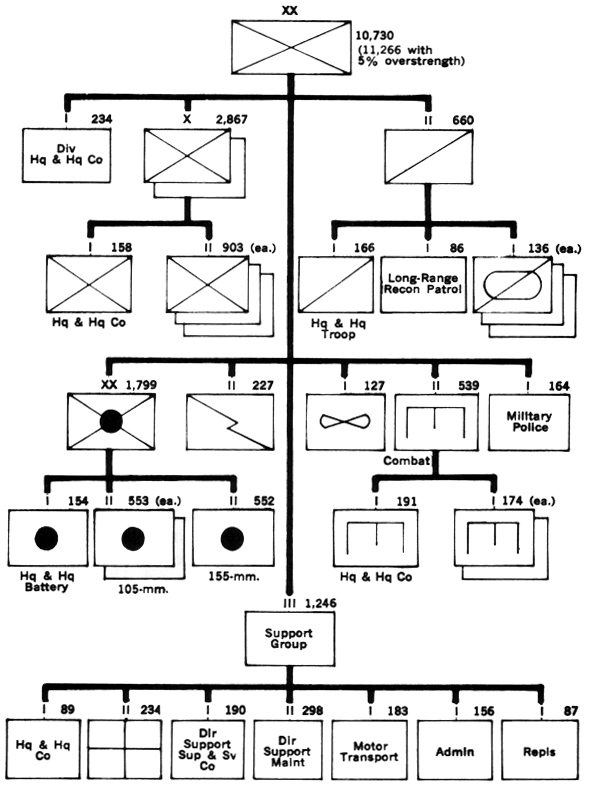

Work continued on the new Thai force structure and another goal was met when a briefing team from US :Military Assistance Command, Thailand, presented on 28 November 196'7 the proposed Thai augmentation force and advisory requirements to General Creighton B. Abrams, then Deputy Commander, US Military Assistance Command, Vietnam. The basic organization was approved and representatives from both MACV and US Army, Vietnam, returned to Thailand with the briefing team to assist in developing the new tables of organization and equipment and allowances. Concurrently, action was taken to initiate funding for table of organization and construction needs in order to meet the training and deployment dates agreed upon earlier. The final tables for the Royal Thai Army Volunteer Force (the Black Panther Division) were approved on 10 January 1968. The force totaled 11,266 men, including a 5 percent overstrength. (Chart 1)

For the final stages of the Thai training, Military Assistance Command, Thailand, proposed that Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, provide 120 advisers. These advisers would deploy with the Royal Thai Army Volunteer Force and the majority would remain with the Thai units while the units were in South Vietnam. General Abrams questioned the size of the requirement and it was subsequently reduced to 81, with 48 needed for the first increment. These 48 advisers were deployed in May 1968.

[38]

CHART 1- ORGANIZATION OF ROYAL THAI ARMY VOLUNTEER FORCE 25 JANUARY 1968

[39]

Both the US and Thai governments were anxious to speed up the deployment of additional Thai forces to South Vietnam. In this regard, the State Department queried the American Ambassador in Bangkok on the possibility of the Thais' augmenting some existing battalions and sending them to South Vietnam early in 1968 under the command of the Royal Thai Army Volunteer Regiment. As a parallel example, the State Department pointed out that the United States was expediting the deployment of infantry forces to the level of 525,000, and in some cases units were having to complete their final training in South Vietnam.

General Westmoreland did not concur with the concept of expediting the Thai augmentation forces to the point of curtailing their training. He believed that forces deployed to South Vietnam should be equipped and ready to accomplish unit missions upon arrival in their area of operations. Although an exception had been made in the case of certain US units, General Westmoreland did not agree in the case of Free World Military Assistance Forces units. He held it essential that, with the exception of limited orientation in Vietnam, Free World units be fully trained prior to deployment. Lacking full training, it would be necessary to divert troops from essential missions until the Free World troops were operational. The threat of a successful enemy attack on partially trained troops and the resultant adverse political consequences for the Free World effort had to be kept in mind.

For different but equally important reasons, the American Ambassador in Bangkok and the Military Assistance Command, Thailand, also viewed the State Department proposal with disfavor. The ambassador pointed out that the Thais were interested in an early deployment as shown by the one-month adjustment in deployment dates, but the suggestion of augmented battalions was impractical. The Thai government had repeatedly announced that the formation of the volunteer division would not detract from Thailand's ability to deal with internal security problems, and that the volunteer division would be a new and additional Army unit. Deploying an existing battalion would not be in accordance with the firm internal security commitment the Thai government had made to the Thai nation.

The Military Assistance Command, Thailand, also opposed early deployment, believing that the early deployment of one infantry battalion would have a serious impact on the activation, training, and deployment of the division. One of the most difficult problems to be faced in forming the division would be the

[40]

provision of trained cadre and specialists. To drain the Royal Thai Army of some 900 trained infantrymen at the same time the volunteer division was being formed would seriously handicap the division.

Nonetheless, the idea of hastening deployment persisted. In view of the high-level interest in accelerating the deployment of the Thai forces to South Vietnam, General Westmoreland suggested that an initial infantry battalion might be deployed six weeks early in accordance with the following concept: select the "best" of the three battalions being trained in the first increment of the Royal Thai Army Division, and send it to Bearcat upon completion of its company training. When it arrives at Bearcat, attach it to the Royal Thai Army Volunteer Regiment, which will partially stand down from active combat. The Thai regiment will be given the mission of completing the battalion phase of the unit's training. Other parts of the training will be completed after the arrival of the complete increment. This concept assumes that the battalion will be equipped and trained in accordance with the planned schedule and that the proposal will be acceptable to the Thai government. If this concept is approved, the deployment of the battalion could be accelerated by about six weeks, and would take place around 3 June 1968. The recommendation was not accepted and the schedule remained as planned.

The question of US support troops for the Thais was further discussed. The US Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, and the US Army, Vietnam, both opposed the idea of supplying US troops to assist in the training of the Royal Thai Army Volunteer Force; the United States was already committed to provide all required support for the activation, training, and deployment of the Thai force. Besides, the Thai Military Assistance Command had even identified certain additional forces required on a permanent basis to support this commitment. Admiral Sharp had concurred with the idea of additional forces and forwarded it to the joint Chiefs. The Department of the Army had then proposed that the additional forces be provided by the US Army, Vietnam, force structure to meet the required dates of January and March 1968. The Department of the Army would then replace these forces beginning in September 1968 from the training base of the continental United States. The Joint Chiefs requested Admiral Sharp's views on the Department of the Army proposal and Admiral Sharp in turn queried General Westmoreland. General Westmoreland replied that US Army, Vietnam, was unable to provide the required spaces

[41]

either on a temporary or permanent basis and that furthermore the requirement had to be filled from other than MACV assets. US Army, Pacific, made a counterproposal, concurred in by Department of the Army, which asked US Army, Vietnam, for 335 of the 776 men required. The remaining spaces would be filled from US Army, Pacific, resources outside of South Vietnam or from the continental United States. Admiral Sharp recommended adoption of the counterproposal and the joint Chiefs of Staff issued instructions to implement the plan.

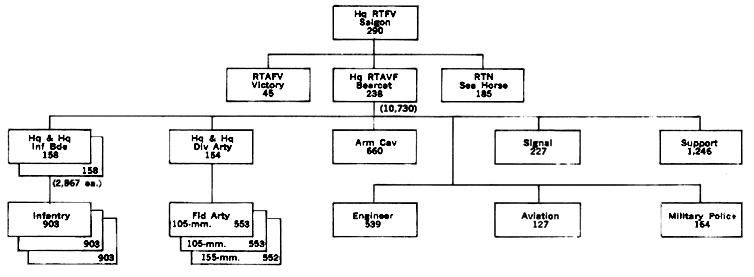

In conjunction with the deployment of the Thai volunteers, in April 1968 the Thai supreme command proposed an increase in the size of the Thai headquarters in South Vietnam from 35 to 228 men. There were several reasons for this request: the primary one was the requirement to administer a larger force. (Chart 2) The supreme command also wished to change the functioning of the Royal Thai Forces, Vietnam, from a headquarters designed to perform limited liaison to one conceived along conventional J-staff lines. The proposed organization, developed from experience and from recommendations from the Vietnam headquarters, would correct shortcomings in many areas such as security, public information, and legal and medical affairs. General Westmoreland, while agreeing in principle, still had to determine if the Military Assistance Command, Thailand, approved of the planned increase and whether the approval of the increase by the American Embassy at Bangkok and the US government was necessary. The Thailand command and the embassy both concurred in the planned headquarters increase, but the diplomatic mission in Thailand did not have the authority to approve the augmentation. Military Assistance Command, Thailand, recommended to Admiral Sharp that General Westmoreland be provided with the authorization to approve a proposed table of distribution and allowances for the enlarged Thai headquarters. This authorization was given and the applicable tables were approved on 19 June 1968. The deployment of the new headquarters began with the arrival of the advance party on 1 July 1968 and was completed on 15 July.

Thai troops quickly followed. The first increment of the Thai division known as the Black Panther Division (5,700 men) arrived in South Vietnam in late July 1968 and was deployed in the Bearcat area. The second increment of 5,'704 men began deployment in January 1969 and completed the move on 25 February. This increment contained the division headquarters and headquarters company (rear), the 2d Infantry Brigade of three infantry battalions, two artillery battalions, and the remainder of the

[42]

CHART 2-ROYAL THAI FORCES VIETNAM

STRENGTH RECAPITULATION

| Hq RTFV | 290 |

| RTAVF | 10,730 (11,266)* |

| Victory | 45 |

| Sea Horses | 185 |

| 11,250 (11,790) |

* Includes 5% over strength

[43]

TROOPS OF ROYAL THAI BLACK PANTHER DIVISION dock at Newport, Vietnam, July 1968, above. Royal Thai flag is carried down gangplank of USS Okinagon, below.

[44]

division combat, combat support, and combat service support elements. The division was under the operational control of the Commanding General, II Field Force, Vietnam.

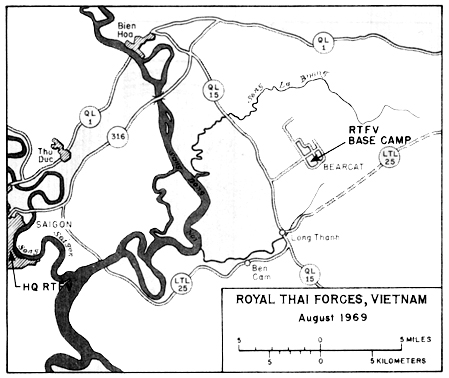

The third increment of the Royal Thai Volunteer Force was deployed to South Vietnam during July and August to replace the first increment, which returned to Thailand. The last of the third increment closed into Bearcat on 12 August 1969. The replacement brigade assumed the designation of 1st Brigade. In addition, the headquarters of the Royal Thai Army Volunteer Force completed its annual rotation. Throughout all of this there was little, if any, loss of momentum in the conduct of field operations. (Map 1)

The area of operations assigned to the Thais was characterized by a low level of enemy action because the land was used by the Viet Cong primarily as a source of food and clothing. Moving constantly and constructing new base camps, the enemy had little time for offensive action. As a result, enemy operations conducted in the Thai area of interest were not as significant as

MAP 1 - ROYAL THAI FORCES, VIETNAM August 1969

[45]

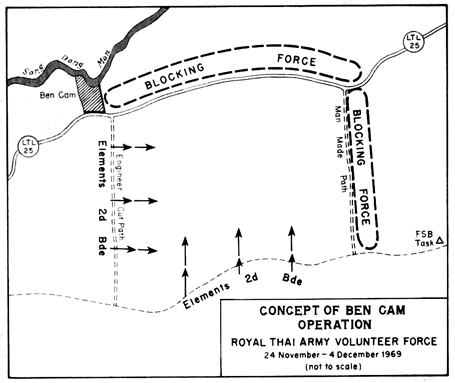

enemy operations elsewhere. Nonetheless, the Thais themselves could launch effective operations. A typical well-planned and successful Thai operation was a search and clear mission conducted by the 2d and 3d Battalions of the 2d Brigade, Royal Thai Army Volunteer Force. It took place in the vicinity of Ben Cam in the Nhon Trach District of Bien Hoa Province during the period 24 November 1969-4 December 1969.

The mission required that an enemy area to the south of Ben Cam village be sealed and then swept free of local guerrillas. Using six rifle companies, the Thais sealed an area bounded on the north by Highway 25, on the west by an engineer-cut path in the vicinity of Ben Cam village, and to the east by another manmade path some forty meters in width. The southern boundary consisted of a trail running from Fire Support Base Tak westward. (Map 2) Once the blocking forces were in position, the troop elements to the west began a sweep on a line approximately 500 meters wide. After this force had been moved eastward some 500 meters the southern blocking force was moved a like distance to the north. This process was repeated until the objective area was reduced to a one kilometer square. Kit Carson Scouts and one former enemy turned informer assisted the

[46]

search through the bunker complexes. As a result of these measures only two casualties were suffered from booby traps.

Two engineer bulldozers and two platoons of engineer troops were used throughout the sealing operation. Their mission consisted of cutting north-south, east-west trails in the area swept by the advancing troops. A route was selected to be cut and the engineers then cleared the jungle area with bangalore torpedoes. Bulldozers followed and increased the width of the cut to forty meters. Infantry elements provided security for the engineers during these operations.

Throughout the maneuver the advance of the infantry troops was on line and void of gaps as the sweeps forced the enemy toward the center. Thai night security was outstanding. On three successive occasions the Viet Cong tried to break out of the trap, and in all three instances they were repulsed. Intelligence reported that seven Viet Cong were wounded during these attempts.

In conjunction with the tactical operations, the U.S.-Thai team conducted psychological operations. All returnees under the Chieu Hoi (open arms) amnesty program were fully interviewed and in 60 percent of the cases tapes of these interviews were made. These tapes were normally played back to the Viet Cong within four hours. The themes were basically a plea to the Viet Cong to return to the fold of the government while it was still possible, to eliminate their leaders and rally, to receive medical care, and to bring their weapons. When Viet Cong rallied without their weapons, a weapons leaflet was dropped and the next returnees brought in weapons. Once all means of drawing the enemy out had been used and continued efforts were unsuccessful, a C-47 aircraft with miniguns was employed to saturate totally the sealed square kilometer area.

The results of this operation were 14 of the enemy killed, 6 prisoners, and 12 returnees. Some 21 small arms and 2 crew-served weapons were also captured.

While air support was used in the last stage of this particular operation, the Thais in general made limited use of air power. Liaison officers of the US Air Force participating in other Thai operations found that planned air strikes were more readily accepted by Thai ground commanders than close tactical air support. The Thai Army division headquarters requested one planned strike every day. The request was made so automatically and as a matter of routine that it seemed to US troops in the tactical air control party that the Thais were accepting the planned strikes out of typical Thai politeness.

[47]

For close-in troop support, helicopter and fixed-wing gunships were preferred. Requests for fighter-bombers were very rare. One air liaison officer stated that Thai ground commanders did not consider close air support a necessity during an engagement. They tended to request it only after contact had been broken off and friendly troops were a safe distance away from the strike. Thus, it became the job of the liaison officer to educate the ground commanders. With one of the two Thai brigades rotating every six months, the education process was a continuing one. As part of the education program, the US Army and Air Force conducted a bombing and napalm demonstration with the Thai observers placed three kilometers away. Even at this distance the results were very palpable and unnerving. Thereafter, as a result of this experience, Thai commanders invariably pulled their troops back approximately three kilometers away from the target before calling in air strikes.

In December 1969 the effects of the withdrawal of the Philippine Civic Action Group, Vietnam, and publicity given the activities of the Symington Subcommittee were felt in Thailand as elsewhere. The United States had welcomed the decision of the Thai government to contribute troops to South Vietnam and was willing to compensate it by logistical support and payment of certain allowances to Thai forces for duty out oŁ the country. These facts led to charges and countercharges regarding the expenditures of funds supporting the Thai division. On 19 December the Bangkok press reported that some twenty government party members of the Thai parliament had signed a letter to the prime minister urging the withdrawal of Thai troops from South Vietnam. The reasons given were that the situation in South Vietnam had improved as a result of the US Vietnamization program and other aid, as evidenced by US cutbacks, and that difficult domestic economic and security problems existed in Thailand. No reference was made to the "mercenary" and "subsidy" charges of the previous few days. On 21 December Thai Foreign Minister Thanat Khoman told newsmen that he had considered the withdrawal of Thai troops "because the United States recently issued another announcement regarding further withdrawals." He also stated that the subject had been discussed with South Vietnamese Foreign Minister Tran Chan Thanh, and had been under consideration for some time. The minister was cautious on the subject: "Before any action can be taken we will have to consider it thoroughly and carefully from all angles.

[48]

We must not do anything or reach any decision in a hurry, neither must we follow blindly in anybody's footsteps."

Two days later there was an apparent reversal of policy. After a cabinet meeting aimed at developing a unified position, the deputy prime minister announced:

Thailand will not pull any of her fighting men out of South Vietnam . . . . Thailand pull never contemplated such a move . . . . The operation of Thai troops in South Vietnam is considered more advantageous than withdrawing them. If we plan to withdraw, we would have to consult with GVN since we sent troops there in response to an appeal from them. It is true that several countries are withdrawing troops from South Vietnam but our case is different.

In addition to ground forces, the Thais had an air force contingent in South Vietnam. While never large, the Thai air force contingent achieved its greatest strength in late 1970. The total number of Thais serving with the Victory Flight, as their Vietnam transport operation was designated, had grown from the original sixteen to forty-five. Three pilots and five flight engineers flew with the Vietnamese in the Vietnam Air Force C47s; nine pilots, seven flight engineers, and three loadmasters were flying C-123K's with the U.S. Air Force 19th Tactical Airlift Squadron which, like the Vietnamese 415th Squadron, was equipped with C-47's and located at Tan Son Nhut. The remaining members of the flight had jobs on the ground in intelligence, communications, flight engineering, loading, and operations. Normally there was an equal balance between officers and enlisted men.

The subject of a Thai troop withdrawal, which arose in December 1969 and was seemingly resolved then, came up again three months later. In a meeting with the US Ambassador in March, the Thai Prime Minister indicated that in light of continued US and allied reductions, there was considerable pressure from the Thai parliament to withdraw. He stated that "When the people feel very strongly about a situation, the government must do something to ease the situation." Little occurred until the following November when the Thai government announced it was planning to withdraw its forces from South Vietnam by 1972. The decision was related to the deterioration of security m Laos and Cambodia and the growth of internal insurgency in Thailand, as well as the US pullback.

The withdrawal plans were based on a rotational phase-out. The fifth increment would not be replaced after its return to Thailand in August 1971. The sixth increment would deploy as planned in January 1971 and withdraw one year later to com-

[49]

THAI SOLDIERS BOARD C-130 AT LONG THANH FOR TRIP HOME

GENERAL ROSSON PRESENTS MERITORIOUS UNIT CITATION to Thai Panther Division.

[50]

plete the redeployment. Thai Navy and Air Force units would withdraw sometime before January 1972. The composition of the remaining residual force would be taken up in Thai-South Vietnamese discussions held later. A token Thai force of a noncombatant nature was under consideration.

The withdrawal plans were confirmed and even elaborated upon through a Royal Thai government announcement to the United States and South Vietnam on 26 March 1971. The Thais proposed that one-half of the Panther Division be withdrawn in July 1971, and the remaining half in February 1972; this plan was in line with their earlier proposals. The three LST's (landing ships, tank) of the Sea Horse unit would be withdrawn in April 1972 and Victory Flight would be pulled out by increments during the period April-December 1971. After July 1971 the Headquarters, Royal Thai Forces, Vietnam, would be reduced to 204 men. It would remain at that strength until its withdrawal in April 1972, after which only a token force would remain.

[51]

page created 18 December 2002