CHAPTER III

The Philippines

The Philippine nation assisted the Republic of South Vietnam for many years. As early as 1953 a group of Philippine doctors and nurses arrived in Vietnam to provide medical assistance to the hamlets and villages throughout the republic. This project, known as Operation BROTHERHOOD, was mainly financed and sponsored by private organizations within the Philippines. Years later the Philippine government, a member of the United Nations and the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization, increased Philippine aid to Vietnam out of a sense of obligation to contribute to the South Vietnamese fight against communism. On 21 July 1964 the Congress of the Philippines passed a law that authorized the President to send additional economic and technical assistance to the Republic of Vietnam. The law was implemented through the dispatch to Vietnam of a group of thirty-four physicians, surgeons, nurses, psychologists, and rural development workers from the armed forces. Four such groups in turn served with dedication during the period 1964-1966.

In addition, and as a part of the Free World Assistance Program, sixteen Philippine Army officers arrived in Vietnam on 16 August 1964 to assist in the III Corps advisory effort in psychological warfare and civil affairs. They were to act in co-ordination with the U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam. Initially the officers were assigned in pairs to the three civil affairs platoons and three psychological warfare companies in the provinces of Binh Duong, Gia Dinh, and Long An, respectively. Of the remaining four, one functioned as the officer in charge, while one each worked with the Psychological Warfare Directorate, the III Corps Psychological Operation Center, and the 1st Psychological Warfare Battalion.

The efforts of the sixteen Philippine officers were directed at a lower governmental level than those of their US allies. Traveling and working with their South Vietnamese counterparts, these officers ensured that the psychological warfare and civil affairs portion of the pacification plan was being carried out. During the time they were in the field, the Philippine officers made an important contribution to the psychological warfare

[52]

effort. Their success prompted the South Vietnamese to ask for another group of sixteen officers.

Discussions between the US and Philippine governments regarding an even larger Philippine contribution to South Vietnam began in the fall of 1964. Philippine officials in Washington who arranged for the visit of President Diosdada Macapagal to the United States suggested that the Philippine government was prepared, under certain conditions, to play a greater role in South Vietnam; however, there was a wide variety of opinion in the United States as to the nature and extent of this additional aid. In Washington, US military officials believed that the Philippines should make contributions such as aircraft crews to support the Vietnamese Air Force; a special forces company; engineer platoons; medical platoons; technical personnel in the fields of communications, ordnance, transportation, and maintenance; and Marine and Navy personnel to assist South Vietnam in training its junk fleet and in other counterinsurgency operations. On the other hand, US civilian officials were inclined to believe that the Philippines should contribute medical and civic action workers and agricultural experts, and supply fertilizer.

In the course of his state visit to the United States, President Macapagal discussed a Philippine military contribution with President Johnson and Secretary of Defense McNamara. In response to President Macapagal's suggestion that his government increase its aid, Secretary McNamara replied that the United States would, along with the Philippine government, consider what further contributions it could make to the South Vietnamese counterinsurgency effort, and to what extent the United States could supplement the Philippine military budget.

Underlying his offer was President Macapagal's desire to make the Philippine military establishment "more flexible" in meeting a potential "threat from the South," Indonesia. For this reason he and his advisers pressed for an increase in the Military Assistance Program. Secretary McNamara reiterated his concern over the unsuitably low budget support the Philippine government provided its armed forces and held out the strong possibility that any increase in US aid would be contingent on an increase in the Philippine defense budget. During the discussion President Macapagal indicated that Philippine readiness to respond in South Vietnam would be related to the presence of other friendly Asians in Vietnam.

Following the Macapagal state visit, the US State Depart-

[53]

ment directed the ambassadors in Saigon and Manila to meet with Major General Lloyd H. Gomes, Chief, Joint US Military Assistance Group, Philippines, and General Westmoreland to compare South Vietnam's needs with the ability of the Philippines to fill them. Also on the agenda were such subjects as the specific units that might be deployed, timing, phasing, priorities, and funding details. The State Department thought that for significant impact any Philippine contingent should number approximately 1,000.

Washington, always anxious to increase the amount of assistance to Vietnam from other countries, saw the Philippines as another contributor. General Westmoreland, however, was quick to warn all concerned of the multiple logistics problems which would be encountered if adequate lead time was not given. Experience had shown that Vietnamese logistical support for Free World forces could not be depended upon, and the existing MACV logistical organization and resources could not absorb any substantial increase without additional resources and adequate time for planning and phasing of the deployment.

A staff meeting held on 14 December 1964 by the joint US Military Assistance Group, Philippines, and Headquarters, Armed Forces, Philippines, discussed the employment of Philippine forces in South Vietnam. The Philippine representatives stipulated that the United States fund the entire Philippine undertaking; replace all ground force equipment deployed on an item-for-item or equivalent basis; and agree to employ the Filipinos on strictly defensive civic action operations in the Bien Hoa area. Special forces and medical personnel could operate in the Tay Ninh area provided they were not near the Cambodian border. The Philippine representatives also revealed the size and composition of the task force they had in mind. President Macapagal had originally thought of sending a combat force to South Vietnam; Ferdinand E. Marcos, then head of the Liberal party, had strongly gone on record as opposing sending any force at all. Accordingly these early discussions restricted the role of the Philippines to a defensive civic action mission with the force tailored to fulfill that mission. The task force strength recommended was approximately 2,480 and was to include an infantry battalion, reinforced, an engineer battalion, reinforced, a support company, civic action personnel, a Navy contingent, and an Air Force contingent.

Early in 1965 the number of participants in discussions of Philippine aid was increased when the government of South Vietnam officially requested more aid from the Philippines. The

[54]

fate of this request was uncertain for several months. President Marcos, elected in the fall of the year, had been explicit on the subject of Vietnam aid some months earlier. Only after he had studied the situation did he modify his position by saying, "No, I will not send, I will not permit the sending of any combat forces. But I will get behind the idea of sending a civic action force." Once again the task force concept was modified to make the final product a mixture of an engineer construction battalion and medical and civic action teams with their own security support.

During the first half of 1966 President Marcos pressed for passage of a bill based on the civic action task force concept that permuted the force to be sent to South Vietnam. The legislation also provided for an allocation of funds for this purpose up to thirty-five million pesos ($8,950,000). The bill easily passed the House of Representatives but encountered opposition in the Philippine Senate. After much debate, delay, and extra sessions, the Senate passed the bill on 4 June by a vote of fifteen to eight. The bill was then referred to a joint House and Senate conference committee where it stayed until 9 June; President Marcos signed it on 18 June. The bill permitted the dispatch of a 2,000-man civic action group consisting of an engineer construction battalion, medical and rural community development teams, a security battalion, a field artillery battery, a logistics support company, and a headquarters element. The force was to undertake socio-economic projects mutually agreed upon by the Philippines and South Vietnam.

The preamble of the bill clearly stated the reasons for the decision of the Philippine Congress to expand the Philippine people's commitment m South Vietnam. Similar sentiments were contained in a statement by President Marcos who said: "I repeat that if we send engineers to Vietnam this will be because we choose to act on the long-held convictions of the Philippine people, that the option for liberty must be kept for every nation, that our own security requires that democracy be given the chance to develop freely and successfully in our own part of the world."

Not discounting these patriotic motives, it must be pointed out that in return for Philippine support the US Military Assistance Program granted aid to the Philippines in those areas suggested by President Marcos. Included were four river patrol craft for anti-smuggling operations, M 14 rifles and machine guns for one constabulary battalion combat team, and equipment for three engineer battalions. This aid was in addition to the previous commitments for one destroyer escort and several other patrol craft. Also being considered was the provision of one F-5

[55]

squadron and helicopter units. The unit was meanwhile assembling. On 1 June 650 officers and enlisted men began training at Fort Magsaysay while at other military areas groups of volunteers were awaiting transportation to Fort Magsaysay.

In the original planning the Philippine Civic Action Group had anticipated deploying approximately 120 days after the Philippine Congress passed the bill. This figure was based on a 60-day period for transport of the group's engineer equipment to the Philippines, including 15 days for deprocessing and movement to a training area, 45 days of training with the equipment, and 15 days for processing and transporting the unit to Vietnam. President Marcos, unhappy about the lengthy lead time required for the departure of his troops, felt that opponents of the bill would continue their opposition as long as the troops remained in the Philippines. In response, the US Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, pointed out that the deployment date could be moved up considerably if the training equipment could be made available in less than the 45 days scheduled, but apparently this was not possible. A Joint Chiefs of Staff proposal that the Philippine Civic Action Group, Vietnam, conduct all individual and unit training in South Vietnam MACV considered infeasible. MACV pointed out that if an untrained unit was deployed to Vietnam, US or Free World tactical forces would be obliged to provide security forces at a time when they would be otherwise committed to tactical operations. In addition, if an inadequately trained Philippine civic action group was attacked and did sustain significant casualties, the far-reaching political implications could adversely affect both the Philippine and the United States governments. An alternate proposal made by the Commander in Chief, Pacific, was that an advance planning group be sent, to arrive within 30 days following passage of the bill, with the advance party to arrive within a 60-day period and the main body at the end of 90 days. This proposal was believed to have merit, but only if it was absolutely necessary to deploy the Philippine group earlier than planned. Recognizing the importance of the training, President Marcos accepted the four-month timetable.

In the course of their training, the Filipinos were assisted by two US mobile training teams. One team from the United States Army, Vietnam, assisted in training with M16 rifles and tactics peculiar to operations in South Vietnam. A second team from the US Eighth Army in Korea conducted training on M 113 driving and maintenance. During the training period in the Philippines, the Philippine group experienced some difficul-

[56]

ties because of limited funds, lack of equipment, and interruptions caused by parades and ceremonies. Even though schedules were disrupted, however, the training was useful and had a steadying influence on the civic action group's later activities.

US support for the Philippine Civic Action Group, Vietnam, as it was finally worked out was approximately $36 million, most of which was for the purchase, operation, and maintenance of heavy equipment such as bulldozers and trucks. While the Philippine government paid the group its regular wages, the United States was committed to the payment of an overseas allowance and per diem at the rate of $1 for each person. The additional daily overseas allowance was paid according to rank.

| Brigadier General | $6.00 |

| Colonel | 5.00 |

| Lieutenant Colonel | 5.00 |

| Major | 4.50 |

| Captain | 9.00 |

| 1st lieutenant | 3.50 |

| 2nd Lieutenant | 3.00 |

| Master Sergeant | 1.50 |

| Sergeant 1st Class | .50 |

| Corporal | .20 |

| Private First Class/Private | .10 |

The United States further agreed to furnish the Filipinos in Vietnam with additional material, transportation, and other support. Class I supplies, subsistence (not to exceed the value of subsistence to US troops), was provided through the US logistic system except for rice-800 grams per man per day-and salt -15 grams per man per day-which were furnished through the Vietnamese armed forces supply system. Special Philippine dietary and other items not included in the US ration were purchased by the Philippine Civic Action Croup. The United States provided only transportation for these last items from ports in the Philippines to Vietnam.

All Class II and IV general supplies were furnished through the US logistical system with the following exceptions: items common to the Philippine group and the Vietnamese armed forces but not used by the US forces in Vietnam were supported through the Vietnam armed forces supply system; items peculiar to the Philippine group were supplied through the Philippine group supply system; a stockage level of forty-five days of third echelon repair parts was authorized to support those items of equipment provided through the Vietnamese armed forces supply system.

Class III supplies-petroleum, oil, and lubricants-were

[57]

provided through the US logistic system.

Class IV, ammunition-all items of ammunition and pyrotechnics-were provided through the US logistical system.

Maintenance through the third echelon was performed by the Philippine group as far as it was able. Equipment maintenance beyond the capacity of the Philippine group or the Vietnamese armed forces was provided by US Military Assistance Command, Vietnam. Equipment that became unserviceable and too costly to repair either through combat use, fair wear and tear, or other reasonable cause was replaced by the appropriate US or Vietnamese armed forces agency.

Transportation between Vietnam and the Philippines was provided by MACV for members of the Philippine group traveling in connection with Philippine group activities. Movements of personnel and equipment were made under the same conditions and system of priorities that applied to US units. This transportation included such authorized travel as the rotation of Philippine group personnel, recall of personnel to the Philippines, return of the dead, and movement of inspection teams in connection with Philippine group activities. Philippine group transportation facilities were used whenever available.

Other support accorded members of the Philippine Civic Action Group, Vietnam, by the Commander, US Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, consisted of permission to use US mess, billeting, club, religious, exchange, commissary, and mail facilities, and to participate in US military recreation programs.

The United States assisted the Philippine group in recovery of the dead and provided mortuary service. The United States further agreed to the provision of death gratuities for members to be administered along the same general lines as the payment of such gratuities to Korean troops.

As support and training questions were being resolved, General Ernesto S. Mata, chief of staff of the Armed Forces of the Philippines and nine other officers arrived in Saigon on 20 July 1966 for three days of talk and an inspection tour. In an unpublicized visit, General Mata emphasized to General Westmoreland the feelings of President Marcos about the strength of the Philippine Civic Action Group. Marcos believed that its organic firepower was inadequate, particularly in the areas of automatic weapons, large mortars, and artillery and that the security battalion did not have the armor and could not carry out the armed reconnaissance that was standard in a comparable US unit. He therefore wanted assurance of quick and effective reinforcement from nearby US and South Vietnamese combat elements in case of large-scale attacks on Philippine installations.

[58]

Most of these points were academic because MACV had some three days earlier authorized the Philippine group seventeen additional APC's (armored personnel carriers), six 105-mm. howitzers, eight 4.2-inch mortars, two M41 tanks, and 630 M16 rifles.

With the signing of the military working agreements between the Republic of the Philippines and the United States (Mata-Westmoreland Agreement, 20 July 1966) and between the Republic of the Philippines and the Republic of Vietnam (Mata-Tam Agreement, 3 August 1966), the way was clear to implement the provisions of the bill.

The military working agreements specified that tasks for the Philippine Civic Action Group, Vietnam, would be determined by the Free World Military Assistance Policy Council. Pursuant to these agreements the Philippine group's basic mission was "to render civic action assistance to the Republic of Vietnam by construction, rehabilitation, and development of public works, utilities, and structures, and by providing technical advice on other socioeconomic activities." Command and control was vested in the Commanding General, Philippine Civic Action group, Vietnam. The Philippine rural health teams and provincial hospital medical and surgical teams were to provide services on a mission basis in coordination with the Ministry of Public Health of the government of South Vietnam and the US Agency for International Development.

In considering the employment of the Philippine Civic Action Group, Vietnam, MACV had decided that Long An Province was unsuitable because its compartmented terrain precluded maximum use of the group and that the land in Hau Nghia Province was preferable. Partly because of the support of the Philippine military attaché for the Hau Nghia location, the area around the town of Bao Trai (Kiem Cuong) was selected. On 1 June, however, General Westmoreland directed that a staff study be conducted to determine the feasibility of relocating the Philippine group in Tay Ninh Province. He believed that the operations of the US 25th Infantry Division around Bao Trai would make it unnecessary to use the Philippine group in that area. In addition there was a certain historical affinity between Cambodia and the Philippines, and the new site would place the Philippine group near the Cambodian border. This suggestion of a border site for the Filipinos was met with some misgivings by the government of South Vietnam; the Vietnamese Minister of Defense, Lieutenant General Nguyen Huu Co, believed that there was a security risk in stationing a unit so close to War Zone C, but he added that it would be a great advantage if the group could pro-

[59]

vide support for the 100,000 loyal Cao Dai, members of a politically oriented religious sect, in Tay Ninh Province.

Initially opposed to the change in locations, the Philippine government sent the commanding general of the Philippine Forces in Vietnam, Brigadier General Gaudencio V. Tobias, to survey the situation. He was given detailed briefings by the province chiefs of both Hau Nghia and Tay Ninh Province, and made a ground and air reconnaissance of each province. Members of the 25th US Infantry Division and II Field Force, Vietnam, briefed him on the support and security to be provided the Philippine group. Among the reasons given for the selection of Tay Ninh instead of Hau Nghia was the lower rate of Viet Cong incidents in Tay Ninh.

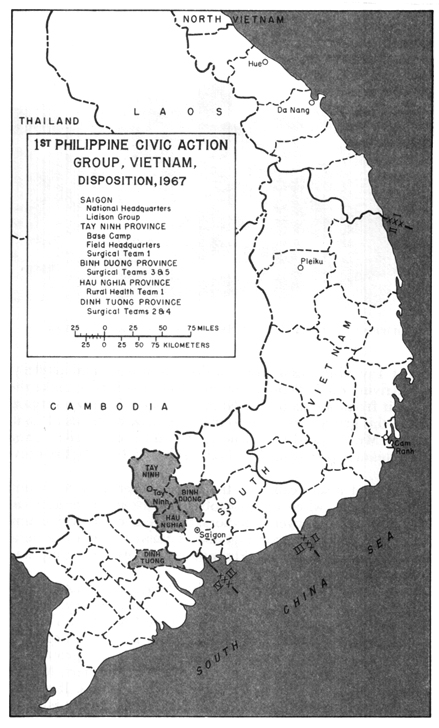

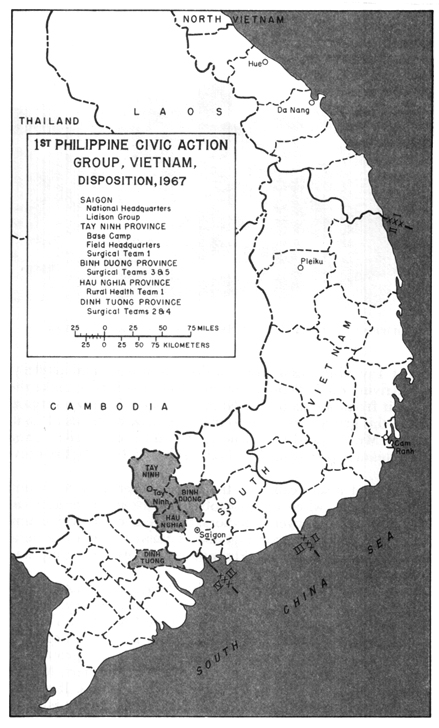

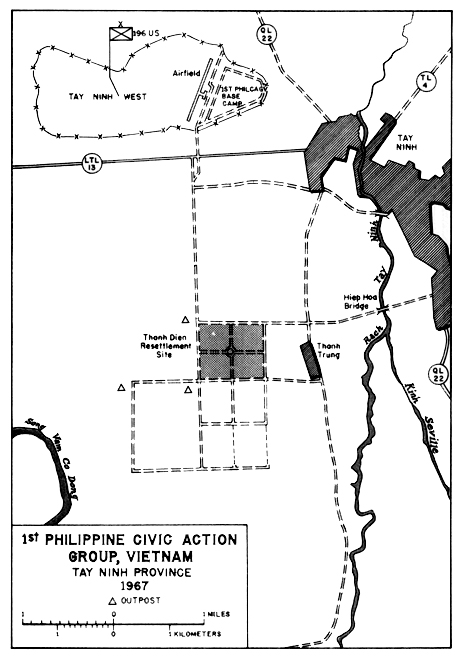

The new location was approved. (Map 3) The Philippine Civic Action Group, Vietnam, agreed to provide its own local security, upon arrival, while US forces would provide area security until the Philippine security battalion could assume the responsibility. In the future the Philippine group would be included in all mutual security arrangements in and around Tay Ninh City, would be supported by 105-mm. and 155-mm. units from their base locations, and would receive contingency support from the nearby 175-mm. guns. The security situation was further improved when the 196th Light Infantry Brigade was stationed in Tay Ninh.

The first element of the Philippine Civic Action Group arrived in South Vietnam on 28 July 1966 to survey and lay out the proposed base camp in Tay Ninh. On 16 August the first element was followed by an advance planning group of 100 officers and men charged with the task of co-ordinating with several Vietnamese and US military agencies involved in the reception, transport, and support of the rest of the group. Among this advance planning group were three civic action teams which initiated medical and dental projects within the surrounding hamlets. During their first seven weeks of operations, these teams treated an average of 2,000 medical and dental patients per week. The next increment of the Philippine group, the third, arrived on 9 September 1966 and consisted of sixty drivers, maintenance specialists, and cooks.

With the arrival of General Tobias and his staff on 14 September 1966, the Philippine Civic Action Group, Vietnam, became firmly and fully established. Two days later 741 men who had recently arrived from the Philippines were airlifted from Cam Ranh Bay to the Tay Ninh base camp, which was by this time sufficiently well prepared to handle large groups. Next to

[60]

MAP 3 - 1st PHILIPPINE CIVIC ACTION GROUP, VIETNAM, Disposition 1967

[61]

PHILIPPINE SECURITY TROOPS REBUILD A BASE CAMP BUNKER

arrive at Tay Ninh was a group of doctors, nurses, and artillerymen. Arriving on 26 September, they were the first to make the trip by air from Manila to Tay Ninh via Saigon. The two surgical teams in this group were sent to the provincial hospitals of Dinh Tuong at My Tho and Binh Duong at Phu Cuong, while a rural medical team was sent to Bao Trai, capital of Hau Nghia Province.

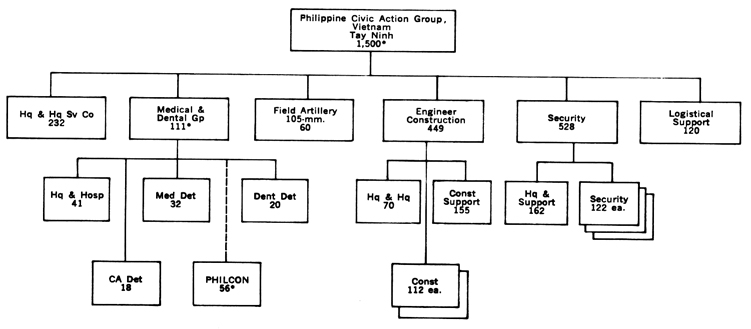

Additional assets came to the 1st Philippine Civic Action Group, Vietnam, when on 1 October operational and administrative control of the twenty doctors, nurses, and medical technicians of the Philippine contingent was turned over to General Tobias. By mid-October the Philippine Civic Action Group had reached full strength. (Chart 3)

From 15 to 19 October 1966 the Philippine armed forces accomplished the biggest air movement in their history. During this period the remainder of the Philippine Civic Action Group was transported directly from Manila International Airport to the Tay Ninh West airport adjacent to the Philippine group base camp. In accordance with instructions from President Marcos the troops departed during the early morning hours. It was his wish that the Philippine group be dispatched as quietly as possible, without publicity or opportunities for large gatherings at

[62]

CHART 3-PHILIPPINE CIVIC ACTION GROUPS VIETNAM

* Philippine Contingent strength is not included in Philippine Civic Action group, Vietnam, table of organization totals because support came from a separate Republic of the Philippines appropriation.

[63]

loading areas. With the arrival in Vietnam of these elements the group was at its full strength of 2,068.

During this early period the Philippine group's main effort was directed toward the construction of a base camp that would serve both as a secure area and as a model community eventually to be turned over to the people of Tay Ninh. This community, which was soon to contain over 200 prefabricated buildings, was the Philippine group's first major construction effort.

Toward the end of September, the group began limited engineering work, making road repairs in some of the hamlets bordering the eastern side of Thanh Dien forest. Once a Viet Cong stronghold, this forested area became the site of the second major Philippine group project. In time, portions of the forest would be cleared, and roads and bridges built to open about 4; 500 hectares of farmlands for refugee families from all over Tay Ninh Province.

In an effort to facilitate the execution of this mission, the Philippine Civic Action Group produced and distributed more than 83,000 leaflets in the Vietnam language containing the text of Republic Act 4664 (aid-to-Vietnam bill) and explaining the Philippine presence in Vietnam and the humanitarian missions to be accomplished. (See Appendix A.)

It was also in September that the Philippine group suffered its first casualties. While on convoy duty to Saigon, seven enlisted men were wounded by a claymore mine at Tra Vo in Tay Ninh.

Seasonal rains throughout September and early October restricted the use of heavy construction equipment, but despite the adverse weather conditions some engineering work was still carried out.

On 1 December 1966 the clearing of the resettlement site at Thanh Dien forest began. A task force designated BAYANIHAN and composed of elements of one reinforced engineer construction company, one reinforced security company, one explosive ordnance disposal team, one artillery forward observer team, and two civic action teams had the mission of clearing the project site. External security for the task force was provided by four Vietnamese Regional Forces or Popular Forces companies. In this operation the explosive ordnance disposal team was extremely busy since almost every inch of the area had to be cleared of mines, booby traps, and duds. In addition, Task Force BAYANIHAN was subjected to harassing fire from mortars, rifle grenades, and snipers on four separate occasions during the month of December.

In December also, at the request of Philippine President

[64]

Marcos, General Westmoreland visited Manila, where he praised the excellent performance of the Philippine Civic Action Group, Vietnam, and suggested that if the Philippine government wanted to increase its contribution to South Vietnam it might consider providing a squadron of UH-1 D helicopters for civic action work. Another possibility was Philippine assistance in training a South Vietnamese constabulary similar to the Philippine constabulary; some Philippine advisers could go to South Vietnam while some Vietnamese cadres could be placed with the Philippine constabulary for training in the Philippines.

President Marcos appeared genuinely interested in the idea of forming a helicopter squadron, particularly if his country was to be permitted to keep the aircraft after the completion of the Vietnam mission. He was also in favor of the US proposal to train additional helicopter pilots with the thought that they might be available for duty in South Vietnam, and showed interest in the proposal to have ten helicopters in Vietnam while six were retained in the Philippines for training purposes. But Marcos was not yet ready to approve the entire project, even though the US Embassy in Manila and General Gomes, Chief, Joint US Military Assistance Group, Philippines, concurred in the project and recommended its implementation. Both the ambassador and General Gomes were aware, however, of limiting factors. The Philippine Military Assistance Program could not absorb funding for the squadron without destroying its current program. Furthermore, all of the initial training would have to conducted in the United States because there were no facilities available in the Philippines.

General Westmoreland believed that a Philippine helicopter squadron would be a welcome addition to Free World forces in South Vietnam, especially if it could support civic action missions of the expanding Philippine program. He preferred a squadron of twenty-five helicopters with the exact table of equipment to be determined through discussions with the Philippine Civic Action Group. The squadron would have to be equipped with UH-1D's since production of UH-1 B helicopters was being curtailed, but there were not enough helicopters in Vietnam to do this without affecting existing operations. If the aircraft could not be supplied from sources outside Vietnam, then the squadron would have to be equipped first with H-34 helicopters and then with UH-1D helicopters the following year. The usual ten hours of transition flying would be required to qualify Philippine H-34 pilots in the Huey aircraft. Philippine Air Force helicopter squadrons were capable of organic third and fourth echelon

[65]

maintenance, and except for the supply of spare parts no significant maintenance problems were anticipated.

Admiral Sharp, Commander in Chief, Pacific, believed the MACV concept to be practical, but was quick to point out that worldwide demands for the UH-1 were such that accelerated deliveries to the Philippine government were unlikely. In light of the aircraft shortages, the limited capability of the Philippine Air Force, and the lukewarm attitude of the Philippine government, Admiral Sharp viewed the plan as impractical. The proposal was again reviewed by the Secretary of State and the Secretary of Defense, who concluded that a Philippine helicopter squadron to support the Philippine Civic Action Group could not be justified and would be an uneconomical use of the limited helicopter resources. The use of Philippine pilots in South Vietnam to support operations of the Philippine group, however, would be militarily beneficial. Washington finally decided that U.S. authorities should neither raise the question of a Philippine helicopter squadron nor take the initiative in obtaining Philippine pilots to serve with US units supporting the Philippine group. Should the Philippine government again raise the question, however, the US response would be that a careful review of the helicopter inventory and competing high priority military requirements appeared to preclude the formation of a separate Philippine squadron in the near future.

While high-level discussions of additional Philippine support were taking place, work continued on the Philippine pacification effort, the Thanh Dien Resettlement Project. Indeed its establishment and presence had bred complications. By January 1967 the Viet Cong began to realize that the project was a threat to their cause. Harassment of work parties became more frequent and intense. In eases where innocent civilians were not involved, the task force returned the enemy's fire with all available organic and supporting weapons. Even with these interruptions work progressed on the resettlement project and related tasks and the first refugee families were resettled in early April.

Enemy opposition to the Philippine group intensified. The Viet Cong attacked the Thanh Dien area both directly and indirectly. In addition to attacks by fire and a propaganda campaign, attempts were made to infiltrate the Philippine equipment park at Hiep Hoa although attacks had little effect.

In the Philippines developments indicated that there would be extended debate over the appropriation for the Philippine Civic Action Group, Vietnam, for the next fiscal year. Although the appropriation bill had passed in the House by an overwhelm-

[66]

ing vote (81-7) the previous year and more closely in the Senate (15-8), indications pointed to increased opposition. It was contended by one opposition block that the 35-million-peso allocation could be better spent on Philippine roads and irrigation.

The new appropriations bill for the Philippine Civic Action Group, Vietnam, went before the Philippine Congress in March 1967. Speaker of the House Cornelio T. Villareal and other congressmen suggested tying the bill to an over-all review of US Philippine relations, with particular emphasis on the fulfillment of US military aid commitments. Possibly in an attempt to bolster the bill's chances, South Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyen Cao Ky asked President Marcos to consider extending the tour of duty and enlarging and expanding the activities of the Philippine group. Ky's note, written in the first person, reached President Marcos on 13 March and began with an expression of appreciation for the Philippine group's efforts. President Marcos responded to the note during his surprise visit to South Vietnam.

Accompanied by General Mata, now Secretary of National Defense, and others, on 16 July Marcos arrived at the Philippine group's base camp at Tay Ninh. During his stay the Philippine president made a presentation of awards, was briefed by General Tobias, and toured the Thanh Dien Resettlement Project. News of his nine-hour visit became known during the afternoon of 16 July and by that evening Filippinos were expressing their admiration for Marcos and comparing his sudden and well-kept secret trip to that made by President Johnson the previous year. In response to press questions of whether the Philippines would increase their participation in Vietnam, Marcos said:

No, there is no plan to increase our participation. But it has been suggested by some elements here in the Philippines that we should increase such participation. There are many factors to consider: and therefore, as ~ said, right now there is no plan to increase our participation but, of course a continuing study is being made on all these problems, and this is one of those problems . . . .

General Westmoreland learned in August 1967 that there were plans for replacement forces. The Philippine government was then assembling volunteers for the second Philippine Civic Action Group, Vietnam, at Fort Magsaysay. The planning dates, all tentative, indicated that the advance party would leave for South Vietnam around 30 September 1967. A portion of the main force of about 600 officers and men would arrive on 20 October 1967, with the remainder reaching Vietnam before 16 December 1967. Final deployment dates were to be made firm in

[67]

December. In discussions with the Philippine government, General Gomes pressed for maximum training of the second civic action group, using returning group members and equipment, and suggested that Philippine mobile training teams should be introduced early in the training phase. This would permit training to lie conducted by men who were familiar with the equipment, procedures, and area of operations in South Vietnam. With regard to other aspects of the training, the Philippine armed forces were insistent that MACV provide mobile training teams for instruction on U.S. supply procedures and the US Army equipment records system.

General Westmoreland concurred in the training proposal of General Gomes, particularly since the mission of the Philippine Civic Action Group, Vietnam, had not changed. He suggested that the procedure for deployment utilize the overlap of personnel on the individual and small unit level to give on-the-job training to the second civic action group without an undue loss of operating efficiency. The training plan not only permitted the job orientation of the replacement force in Vietnam, but also maintained continuity of the established relationships with the Vietnamese and the Americans, minimized a surge in airlift requirements and facilitated redeployment of returning aircraft, and reduced security considerations associated with assembly and movement of large groups.

In spite of the advantage of individual and small unit rotation, the Philippine government could not support financially any extended overlap and only a two-day period was envisioned. Once a deployment date was set, the entire unit was to be rotated as quickly as possible, depending upon the availability of aircraft.

Preparation for the relief of the Philippine Civic Action Group began on 27 September 1967, when the first group of military training teams was sent to the Philippines to assist in the training of the replacement units.

In November 1967 the American Embassy in Manila established parameters for Philippine armed forces proposals that might lead to additional Philippine contributions to Vietnam, especially engineer units. It was almost certain that whatever contributions were made, the armed forces of the Philippines would insist on some form of Philippine command structure to provide command and control of their units. Units that could be substituted for US personnel spaces would be organized under a Philippine logistical support group with a small headquarters for command and control. The logistical group would contain one to three engineer construction battalions and might also include the engineer unit then in South Vietnam.

[68]

The Philippine Navy and Air Force made their own proposals. The Philippine Navy proposed in order of priority: crews totaling 400 for LST's (landing ships, tank) or 224 officers and men to operate a sixteen LCM (landing craft, mechanized) board group, or 100 officers and men to operate a division of twelve PCPs (coastal patrol craft or Swift craft) in Operation MARKET TIME, or 100 officers and men to operate a division of four PGM's (motor gunboats) in MARKET TIME.1

Using U.S. aircraft and equipment, the Philippine Air Force proposed to operate in a support role in South Vietnam. A squadron of twelve aircraft, preferably C-7A's (Caribous) or C-123's (Providers), was considered. On the basis of sixty flying hours per month for aircraft and no base support requirements, the squadron would have required 50 officers and 203 enlisted men.

After considering the proposals, the State Department believed the best force from the standpoint of both South Vietnam and the Philippines would be three Philippine Army engineer battalions of about 2,100 officers and men. The United States would accept the idea of a Philippine security support force if the Republic of the Philippines insisted but did not want the spaces for the security force to come from the engineer battalions.

The 14 November Philippine Senate elections meanwhile would have a bearing on the future status of the Philippine Civic Action Group, Vietnam. The matter of whether or not to retain the group was injected into the campaign by the opposition Liberal party candidates, who termed the group's presence in Vietnam a diversion of needed funds from domestic Philippine requirements. President Marcos sought to remove the issue from the campaign by postponing his request for an appropriation for the Philippine Civic Action Group in the expectation that his Nationalist party would retain control of the Senate.

The outcome of the election was that the Nacionalista party captured six of the eight contested Senate seats. Marcos lost little time in introducing a $9 million appropriation bill for the continued deployment of the Philippine Civic Action Group, but the bill, while easily passing the House, came under fire not only from members of the Liberal party but also from elements of the ruling Nacionalista party. Senate opposition stemmed in part from a small minority critical of US policies in Vietnam and of

[69]

the presence of US bases in the Philippines. It was also possible that a good share of the opposition resulted from factional maneuvering for control of the Senate itself.

In an effort to placate its critics, the Marcos administration introduced a revised bill that extended the Philippines Civic Action Group, Vietnam, for that calendar year. The bill also reduced the engineer elements and increased proportionally the number of medical personnel.

Since funds to support the group were practically exhausted, the government intended to make a token troop withdrawal to forestall criticism of spending without appropriation and to point out to the Senate that the group was at the end of its rode. Unless Congress did something soon the Marcos administration would have to pull the entire unit out for lack of funds. The goal was to restore the force to full strength when the new appropriations bill was passed, but when the regular session of Congress ended there was still no action on the appropriations bill. A special Congressional session convened on 8 July, but had no more luck than its predecessor at passing the appropriations bill. The strength of the Philippine group in Vietnam had declined over the months to about 1,800 because returning troops were not being replaced.

It was not surprising then that the armed forces of the Philippines informed the American Embassy in Manila on 31 July 1968 that it had the day before issued instructions to reduce the Philippine unit in Vietnam from 1,'735 men to 1,500; in accordance with instructions from President Marcos, the reduction was to be accomplished by 15 August. There was speculation that this action may have been a political compromise on the part of President Marcos against pressures for an even greater reduction of the Philippine Civic Action Group. The Philippine President's decision was serious enough to cause the American Embassy in Manila to ask General Gomes to see Mr. Mata, the Philippine Secretary of Defense, as soon as possible. The American Ambassador wished to express to Mr. Mata his concern that this reduction would be badly misinterpreted outside the Philippines. In light of his own conversation with President Marcos, the ambassador further wished General Gomes to confirm personally with the Philippine President that the purported reduction really represented Marcos' views.

General Gomes met with Mata on 3 August and examined in detail the various arguments against a reduction in the current size of the Philippine group in Vietnam. Mata indicated that he fully appreciated the US position on this matter. On 8 August

[70]

the Philippine Secretary of Defense informed General Gomes that he had talked with President Marcos; the order for the reduction of the Philippine group stood. The following day the American Embassy received a message from the Western Pacific Transportation Office containing an official request from the Philippine Civic Action Group, Vietnam, for a special airlift on 10, 11, 12, and 13 August 1968 to return home 235 members of the Philippine group.

In a news story released on 5 September 1968, Philippine armed forces chief Manuel Yan hinted that the replacement unit then in training would take the place of the Philippine group in Vietnam sometime that month. Yan reportedly told newsmen that financing of the replacement unit would come from the Philippine armed forces regular budget which had already absorbed financing of the civic action group. These were funds made available from other savings in the national budget. He further stated that the mission of the replacement unit was the same as that of the Philippine Civic Action Group, Vietnam, but that greater emphasis would be placed on medical and dental services. In addition, the table of equipment had been changed to increase the number of surgical and rural health teams by five each. To achieve this increase there was a corresponding reduction in the number of men assigned to the engineer battalion. In order to maintain the capabilities of the engineer construction battalion, men assigned to the security battalion were being cross-trained in engineer skills. Philippine Civic Action Group members who had completed a two-year tour in South Vietnam were replaced during the period 16 September- 15 October 1968. The strength reduction and table of equipment change were intended to re-emphasize the noncombatant role of the group to the Philippine Congress and the Philippine people.

On 17 September, the official designation of the Philippine Civic Action Group, Republic of Vietnam, I, was changed to Philippine Civic Action Group, Republic of Vietnam. This was merely an administrative change within the armed forces of the Philippines.

In the Philippines, after the 1968 reduction, the issue of the Philippine group in Vietnam was temporarily out of the public eye. President Marcos had apparently decided that the Philippine national interest was best served by the group's continued presence in South Vietnam. This presence would guarantee a Philippine right to sit at the Vietnam settlement table and to claim a share of the war surplus material. Domestic critics in the

[71]

Philippines, however, soon began calling for a complete withdrawal of the unit. Some members of the Philippine Congress wanted to "punish" the United States for imagined support of Malaysia during the Sabah crises. Other critics felt that there was a legitimate need for the unit at home to oppose a Huk insurgency in central Luzon. Still others considered that supporting even the modest cost of maintaining the civic action group in Vietnam was a continuing financial burden. Since the required funds had been refused by the Philippine Congress, the group was being financed by regular armed forces funds plus $17 million for engineer equipment and $1.5 million annual support provided by the United States.

When the new table of equipment was approved in February 1969 little attention was given to the occasion either by the press or by the public and there were no significant displays of feeling against the Philippine group in Vietnam. In March, however, the Nacionalista party House caucus voted to withdraw the civic action group and replace it with a medical contingent. At the same time approaches were being made to US officials for complete financing of the Philippine Civic Action Group by the United States. This situation raised the question of whether the United States should pick up the entire cost of the Philippine Civic Action Group or be prepared to see the group pull out.

A review revealed that while the Philippine group had done a "passable job" on those construction jobs it had completed, the group could have done more, and that South Vietnamese or US resources could have accomplished the same results. The security battalion and artillery battery had not been assigned offensive missions and had thus contributed nothing to the power of the US Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, to carry on offensive operations. The Philippine force did provide a degree of security to the population of the Tay Ninh City area in which it worked, but since Philippine units engaged in combat only in self-defense, the secure area did not extend beyond the immediate vicinity of the Philippine base camp or work sites. As for any psychological impact, the trade-off was between the loss of some allied solidarity-tempered by the fact that a contingent would remain in South Vietnam-and the resentment that many Vietnamese felt against the Philippine force. This resentment was strengthened by the traditional Vietnamese xenophobia and reluctance to accept assistance from a nation which had its own problems of internal corruption, underdevelopment, and even limited insurgency. In mid-April the US Embassy stated:

On balance, therefore, we feel that we should not ourselves take any

[72]

initiative to maintain PHILCAG in Vietnam. If we relent and acquiesce to the Philippine demands that we pick up the entire check, we will only serve to make it impossible to demand that PHILCAG improve its performance, since one does not preface an effort to shape up a unit by begging them to stay.

The State Department took notice of the embassy position but hoped "for a continuation of the present situation." It was believed that with 1969 an election year in the Philippines, the subject of the Philippine Civic Action Group, Vietnam, could be kept at a low key if the United States would contribute to the discussion by clarifying the choices available to the Philippines.

The existing situation was temporary and lasted only until 5 June, when the Philippine Senate passed its version of the national budget. The budget included funds for the Philippine Civic Action Group but restricted spending to the support of a "phased withdrawal." As the Philippine presidential campaign developed, by early October the civic action group had become a critical issue. President Marcos announced to the press the day after the election a proposed meeting to discuss a plan by which a small medical team would be maintained in South Vietnam. He also indicated that he would not ask Congress for further funding. On 14 November the following communication was received at the US Embassy in Manila:

Excellency: I have the honor to inform you that the Philippine Government has decided to withdraw the Philippine Civic Action Group (PHILCAG) from Vietnam. This decision is taken pursuant to the recommendation of the Foreign Policy Council. Accept: excellency, the renewed assurances of my highest consideration. Signed Carlos P. Romulo, Secretary of Foreign Affairs.

The most immediate problem caused by the announced withdrawal of the Philippine group was its possible impact on other contributing countries. The first effects were noticed in Thailand when on 20 November the Thai Foreign Minister, General Thanat Khoman, discussed the withdrawal with US Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker. The minister expressed his bewilderment that the Free World allies had not been consulted before the Philippine decision to withdraw and indicated that the future of the other contributors to South Vietnam would be a subject for early discussions with other allies. Some Free World forces voiced the suspicion that the United States had been informed beforehand of the Philippine government's most recent action.

Redeployment planning for the Philippine force began on 25 November 1969. The advance party was transported by US C130 aircraft in two increments, the first on 1 December and the second a week later. The main body moved by Philippine LST's

[73]

between 13 and 15 December. Upon its departure the base camp at Tay Ninh was transferred to the US 25th Infantry Division. Headquarters, Philippine Civic Action Group, Vietnam, was then reopened at Camp Bonaficio, Philippines.

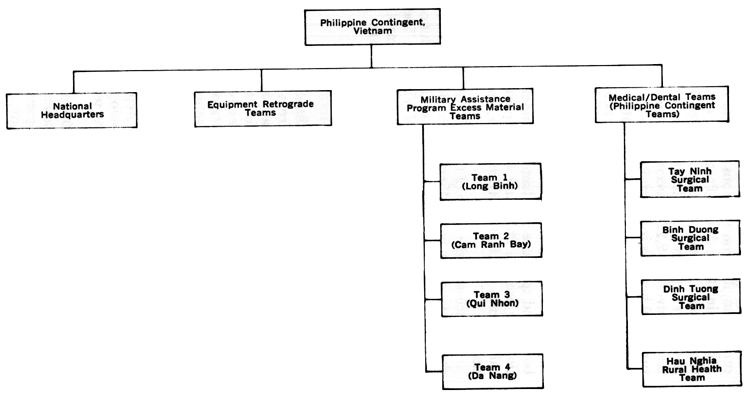

When the main body departed, an equipment retrograde team of forty-four men remained behind to turn in US and South Vietnamese equipment formerly in the hands of the Philippine group. On 21 January 19'70 most of the team departed, leaving only fourteen people to complete the documentation of the equipment turned in. The last of this group left Vietnam on 15 February. The residual force was redesignated Philippine Contingent, Vietnam, and consisted of a headquarters element, four Military Assistance Program excess material teams, and four medical and dental teams. (Chart 4) All members of the contingent belonged to the armed forces of the Philippines, and the unit had an authorized strength of 131. Of these 131, there were 66 qualified medical, dental, and surgical doctors and technicians assigned to teams based in the cities of Tay Ninh, My Tho, Phu Cuong, and Bao Trai. The Military Assistance Program element consisted of 36 logistic specialists with four excess material teams of nine members each. The teams were located in Long Binh, Da Nang, Qui Nhon, and Cam Ranh Bay. The balance of the contingent was assigned to command and administrative duties at the national headquarters in Saigon.

The US Military Assistance Command, in co-ordination with the Chief, Joint General Staff, Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces, provided security for the Philippine contingent. Members of the Philippine headquarters were assigned to US billets in the Saigon area and the operational elements were located within South Vietnamese or US installations. In keeping with former policy, members of the Philippine contingent carried arms only for the purpose of self-defense in the event of enemy attack. The Philippine contingent did not engage in offensive military operations.

The cycle was now completed. In 1964 the first unit of the Philippine Contingent, Vietnam, consisting of medical, dental, and surgical teams had arrived in South Vietnam. When the Philippine Civic Action Group, Vietnam, I, arrived in 1966, the original contingent was attached to this larger force with its capabilities integrated into the civic action mission. At the beginning of 1970 Philippine Contingent, Vietnam, became the Philippine designation of the rear party of the Philippine Civic Action Group. Basically it was the former Philippine Contingent, Vietnam, element and with no change in mission.

[74]

CHART 4-ORGANIZATION OP PHILIPPINE CONTINGENTS VIETNAM

[75]

During its existence the Philippine group in Vietnam made certain tangible contributions that will bear listing. Under the Engineering Civic Action Program it constructed 116.4 kilometers of road, 11 bridges, 169 buildings, 10 towers, 194 culverts, and 54 refugee centers. It also cleared 7'78 hectares of forest land; converted 2,225 hectares to community projects; and turned 10 hectares into demonstration farms. Under the Miscellaneous Environmental Improvement Program it rehabilitated, repaired, or engaged in minor construction work on 2 airstrips; 94 kilometers of roads; 47 buildings; 12 outposts; and 245 wells. It also trained 32 persons in use and maintenance of equipment; 138 in health education; and gave vocational training to 217. It resettled 1,065 families, distributed 162,623 pounds of food boxes, and sponsored 14 hamlets. Under the Medical Civic Action Program, the Philippine Group contributed 724,'715 medical missions, 218,609 dental missions, and 35,844 surgical missions.

In discussing the value of the Philippine Civic Action Group during its stay in South Vietnam, President Thieu remarked: PHILCAGV has greatly contributed to the revolutionary development program of the Republic of Vietnam. Their untiring efforts also helped bring under government control many people previously living under Communist rule and . . . [gave] them confidence in the national cause.

The pacification efforts of the Philippine Civic Action Group, Vietnam, are impossible to separate from a general history of the unit since pacification was an integral part, if not the whole, of the group's mission. There are certain aspects of the day-to-day operations, however, that can be clearly identified as pacification-oriented and as such can be separated from the basic study.

The Philippine Civic Action Group, Vietnam, came into being when the Philippine Congress passed a bill that authorized the government to send a contingent of engineer construction, medical, and rural development workers to South Vietnam. Briefly, their mission was to assist the Republic of Vietnam by the construction, rehabilitation, and development of public works, utilities, and buildings, and by offering technical advice on socioeconomic activities.

To accomplish this mission, a 2,000-man force was organized with an engineer construction battalion as its nucleus. Other units included a headquarters company with five civic action teams, a headquarters service company, a security battalion, and

[76]

a field artillery battery. Attached to this force were six surgical teams and one rural health team which had been working in Vietnam under an earlier Philippine assistance program.

'Me plan called for the deployment of the Philippine Civic Action Group to Tay Ninh Province where it would clear the Thanh Dien forest, which for years had been a Viet Cong base area near the provincial capital. In addition, the group was to prepare the site for a refugee resettlement village of 1,000 families and at the same time conduct extensive civic action projects in the surrounding area.

The Philippine advance party arrived in Vietnam on 16 August 1966 to co-ordinate the arrival of the main body. With this group were three civic action teams that immediately began to conduct medical and dental programs in the area surrounding the base camp.

After the arrival of the main body in October 1966, work commenced in full. The first major project was the construction of the base camp on the eastern side of Tay Ninh West airfield. The construction was planned so that the base camp could be converted into another refugee resettlement village after the withdrawal of the Philippine Civic Action Group, Vietnam; 150 permanent prefabricated buildings of Philippine design were constructed, along with ten kilometers of road, a drainage system, and an electric lighting system.

The completed complex was more elaborate than was needed for a Vietnamese village, and most observers believed that in the long term the site could have been used more productively as a major training facility. Some American observers criticized the amount of work and materials which went into the construction of the base camp. Some said that by any standards, it was one of the "plushest" military camps in South Vietnam. It appeared to some that the Philippine Civic Action Group was intent on building a showplace that would impress visitors, especially those from the Philippines, and by so doing offset criticism leveled against the Philippine presence in South Vietnam. Much of the time and material used in the base camp construction, the critics felt, could have been better used on projects outside the camp.

Several alternate proposals for the use of the site were made early in the camp's history. One was that it be turned over to the South Vietnamese as a base camp for government troops; but this was not practical since there were few regular troops in the Tay Ninh area. A second proposal, more serious at the time because it had been expressed publicly by the province chief, was that the camp be used as the nucleus of a new university. When

[77]

PHILIPPINE CIVIC ACTION GROUP MEMBER DISTRIBUTES MEDICINES

questioned about the complexity and enormity of such a project and the vast amount of funds that would be required, the province chief replied that the Americans would help him. Another suggestion, which also suffered from a lack of funds, was that an agricultural college be established. The only proposal to merit further attention was the suggestion by the Chief of Staff, Philippine Civic Action Group, Vietnam, that the site be converted into a civil affairs training center.

The Philippine group did not begin to clear Thanh Dien Forest until December 1966 because of the efforts required to secure the base camp. Military operations had to be conducted by US and South Vietnamese forces to clear the forest of Viet Cong. Meanwhile plans for projects were prepared and small-scale action activities were carried out, including the repair of some twenty-five kilometers of road, renovation of dispensaries and schools, construction of playgrounds, and implementation of medical civic action programs. One psychologically important activity was the repair and upgrading of thirty-five kilometers of roadways feeding the Long Ha market area, adjacent to the Cao Dai Holy See. This project did much to gain acceptance of the

[78]

Philippine Civic Action Group, Vietnam, by the Cao Dai sect.

Two formal organizations were created to coordinate Philippine activities with US forces and South Vietnamese officials in Tay Ninh. The first of these, the Tay Ninh Friendship Council, consisted of the Tay Ninh province chief, the commanding general of the 196th Infantry Brigade, and the commanding general of the Philippine Civic Action Group, Vietnam. The council convened only a few times and then ceased its formal activities when other and more informal channels of coordination were found.

The Tay Ninh Friendship Council did produce, nonetheless, a document outlining the responsibilities for co-ordinating the activities and interests of the members. Titled the "Agreement of Mutual Assistance and Cooperation between PHILCAGV, US 196th Brigade and Tay Ninh Province," this document created a Civic Action Committee, the second formal organization. The province chief of Tay Ninh acted as chairman of the committee, which was composed of a senior representative from the Philippine group; the deputy province chief of administration; a representative from the US Agency for International Development; a representative from the joint US Public Affairs Office; the secretary general for rural reconstruction; the chief of information and of the Chieu Hoi amnesty program; the chief of social welfare; the chief of economic services; the chief of health services; the chief of education services; the US S-5 adviser to the Tay Ninh sector; the S-5 of the US 196th Infantry Brigade; the Vietnamese S-5 of the Tay Ninh sector; another representative from the Philippine group; and the chief of any district concerned.

The committee hoped to meet at least once a month, but the organization proved too cumbersome and was difficult to convene. Hence, it rarely met and was of little significance in assisting the coordination between the Philippine group and Tay Ninh Province officials. In actual practice, the Philippine Civic Action Group resorted to more informal face-to-face means of contact. Coordination and co-operation were in turn left to ad hoc arrangements and personal relationships developed between Philippine officers and the Vietnamese officials.

In carrying out various civic action projects, the Philippine group introduced several new pacification techniques to the Republic of Vietnam. The group first explained the Philippine mission in South Vietnam to the local population in leaflets outlining the text of the Philippine Congress resolution which had sent the Philippine Civic Action Group to Vietnam. Philippine

[79]

PHILIPPINE GROUP CLEARS DEBRIS AFTER VIET CONG MORTAR HIT

civic action teams in the rural areas continually stressed their role: to build and not to fight. As a result the people were more receptive to the Philippine efforts than they would have been toward similar activities carried out by a combat unit.

The Philippine civic action teams were efficiently organized and adequately staffed to carry on numerous activities in any one hamlet on a given day. Typically, a Philippine civic action team would arrive in a hamlet and set up a bathing station and clothing distribution point for children; distribute school kits to children and teachers' kits to instructors; distribute food to the poor; and deliver kits to be used for prefabricated schools, or perhaps for a new hamlet office or a maternity dispensary. Subsequently, with the help of the hamlet residents, the Philippine team would erect the structures. The medical members of the civic action team then would set up a clinic which included instruments for minor surgery and special examining chairs. Simple dentistry work was then routinely provided and could be greatly appreciated by the inhabitants because of its rarity. Many times, modest engineering projects such as the repair of a hamlet road would be carried out.

[80]

In addition to the planned visit of an entire civic action team, each company-size unit was required to sponsor a hamlet in the Philippine area of interest and to conduct its own civic action program of modest projects on a permanent basis. Consequent, each of these units became intimately acquainted with a hamlet and its residents. The projects carried out were always small, but were well chosen for psychological impact. Requests for projects originated with the hamlet residents who were asked for advice by the unit. Philippine soldiers and the people then worked alongside each other to complete the project.

The major engineering undertaking of the Philippine Civic Action Group, the Thanh Dien Refugee Resettlement Project, provided much valuable experience that could be applied elsewhere in South Vietnam. The actual clearing of the forest was very similar to US Rome Plow operations conducted elsewhere, but the difference lay in the fact that the Philippine engineers then developed the cleared land by constructing a model village.

Although the Philippine mission did not include the destruction of the Viet Cong, this did not prevent the group from implementing an active and productive campaign of psychological warfare designed to support the Chieu Hoi program. When a civic action team moved into an area, Philippine civic action group intelligence tried to identify the families with Viet Cong members. Attempts were then made to win over these families in order to encourage them to rally to the government cause and persuade their relatives to rally.

The security plans for the Philippine group as a noncombatant force were defensive in nature. The engineering projects were protected by Vietnamese Regional Forces or Popular Forces outposts during the hours of darkness and by their own security troops during the day. In addition, when an area had been chosen for a major project, all the neighboring hamlets received extensive civic action attention in order to develop a favorable atmosphere in the vicinity of the project. The idea was to generate good will among the people and thus perhaps to receive early warning of any impending Viet Cong incursion. Philippine units operated only within range of friendly artillery, and liaison officers were situated at the Tay Ninh sector tactical operations center and the tactical operations centers of nearby US forces. These locations were also linked to the headquarters of the Philippine group by several means of communications.

The Philippine civic action efforts won the friendship and appreciation of many people in Tay Ninh Province. As Asians, the members of the Philippine group were well qualified to un-

[81]

ENTERTAINERS OF PHILIPPINE GROUP PLAY TO VILLAGERS

derstand and communicate with the Vietnamese people. They were not the target of anti-European feelings that were a legacy of the colonial period.

Other Vietnamese in Tay Ninh were less favorable toward the Philippine civic action group for several reasons. Reports made by the rural technical team of CORDS (Civil Operations Revolutionary Development Support) indicated that some people disapproved of what they termed "black marketeering and womanizing" by Philippine members. Prominent civilian and government persons in Tay Ninh Province expressed similar views. During a confidential conversation in July 196'7 the Tay Ninh province chief commented unfavorably on the extent of the Filipinos' amorous activities and cited the numerous reports he had received of Filipino soldiers selling post exchange items and stolen material on the local black market. The province chief also claimed that the Vietnamese considered the Filipinos to come from an inferior culture without Vietnam's long history. This attitude, shared by other Vietnamese, had not been expressed overtly, but there were indications that this feeling constituted a barrier affecting the cooperation between provincial officials and Philippine officers.

[82]

The Thanh Dien Refugee Resettlement Project

The Thanh Dien Refugee Resettlement Project, undertaken by the Philippine Civic Action Group, Vietnam, at the suggestion of the province chief of Tay Ninh, involved the clearing of about 4,500 hectares of forested area for agricultural use, the development of 100 hectares for residential lots, and the construction of 41 kilometers of road. In addition, abridge was constructed that linked Thanh Dien and a newly created hamlet, Phuoc Dien (Happy Riceland), with Highway 22. This resettlement site became the home of some 1,000 refugee families.

A Viet Cong stronghold for twenty years, the Thanh Dien forest was the home of the C-40 Regional Viet Cong Company, two Viet Cong guerrilla squads, and one Viet Cong special mission squad. Their presence in the Thanh Dien forest area threatened Tay Ninh City, the provincial capital, as well as the villages and hamlets of Phuoc Ninh District along Route 13 in the north and the villages and hamlets of Phu Khuong District along Highway 22 in the east. By clearing the Thanh Dien forest it was believed that the Viet Cong could be driven south. Government control would then extend up to the Vain Co Dong River.

Before work could begin, the forest had to be swept of organized resistance. This was accomplished before the project starting date by the U.S. 196th Light Infantry Brigade and units of the Vietnamese Regional Forces and Popular Forces through extensive search and clear operations.

The Philippine Civic Action Group began work on the project with Task Force BAYANIHAN On 1 December 1967. The force consisted of one reinforced engineer construction company, one reinforced security company, one explosive ordnance demolition team, one artillery forward observer team, and two civic action teams. Task Force BAYANIHAN approached the project area from the pacified hamlet of Ap Thanh Trung and then proceeded westward along an oxcart trail previously used only by Viet Cong and Viet Cong sympathizers. (Map 4) The troops literally inched across the forested area, defending themselves against enemy snipers and sappers and always keeping a close vigil for mines and booby traps. During this stage of the operation three to four Regional Forces companies provided outer security and protected the task force.

Despite this protection and the exercise of great caution, Task Force BAYANIHAN was, during the first six months of work, subjected on eight occasions to harassing fire from small arms, grenade launchers, and mortars; two Philippine enlisted men

[83]

MAP 4 - 1st PHILIPPINE CIVIC ACTION GROUP, VIETNAM, Tay Ninh province 1967

were killed and ten more wounded. In addition, two bulldozers and an armored personnel carrier were badly damaged, and a road grader and a tank were lightly damaged. With the degree

[84]

of resistance increasing, it became obvious that the project was a threat to the Viet Cong hold on the area and the completion date of 30 July began to appear a little optimistic.

As the land was cleared Philippine engineers laid out the street pattern for the model village and began preparing farm plots. The Province Refugee Service then constructed refugee-type housing on the prepared sites. The Philippine group completed the engineering tasks that were beyond the means of the province. By the end of March the eastern half of the community subdivision was completed and on 4 April the first fifty refugee families were resettled by the province administration.

The province then formed a military and civil team composed of Regional Forces, Popular Forces, and Vietnamese government officials from the various provincial agencies. This team, working closely with a Philippine special civic action team, assisted the newly settled refugees to develop a viable community. CORDS, (ARE (Co-operative for American Remittances to Everywhere), and Catholic Relief Service supplied commodities for distribution. Economic activities, tailored to the capabilities and skills of the villagers, were developed to assist them in becoming self-sufficient. For example, a carpentry shop started with donated tools made furniture for the Philippine enlisted men's club; a cooperative was begun for the manufacture of straw hats; small, short-term agricultural loans were made; vegetable seeds were distributed; piglets were given to selected families; and a pilot project was started to grow IR-8 rice developed by the Rockefeller International Rice Research Institute in the Philippines. As the clearing and the grading of the land proceeded, each new family received a half hectare of land for rice cultivation.

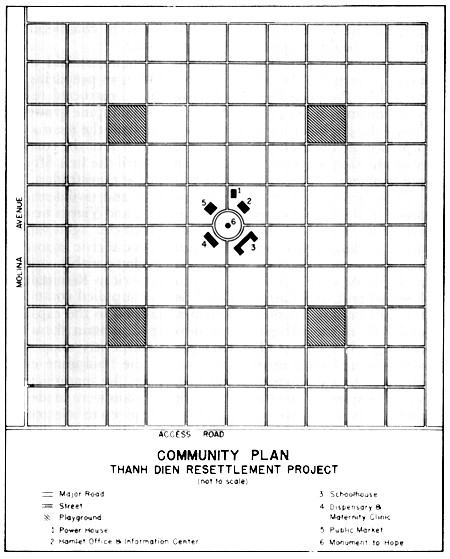

The development of the refugee resettlement site not only involved clearing and subdivision of the area, but the construction of community installations and facilities as well. Around the community center, the Philippine Civic Action Croup constructed a hamlet office and information center, a dispensary and maternity clinic, and a ten-room schoolhouse. The province administration contributed to the project by constructing a public market and a powerhouse. Last, as an inspirational symbol, the Philippine group constructed a monument of "Hope" in the center of the community. (Map 5)

Economic improvements were not the only goals; efforts were also made to establish political institutions. A village chief was appointed by the province chief and the families were organized into residential blocks, each having a designated spokesman.

[85]

MAP 5 - COMMUNITY PLAN THANH DIEN RESETTLEMENT PROJECT

On 30 November 1967 the Thanh Dien Refugee Resettlement Project and the Hiep Hoa bridge were completed. Both projects were turned over to South Vietnamese authorities in a special ceremony on the following day. The bridge was opened with South Vietnamese Defense Minister Nguyen Van Vy as the guest of honor. At a parade staged in his honor, Minister Van Vy presented the Republic of Vietnam Presidential Unit Citation to the Philippine group for its civic action work. Philippine Ambassador Luis Moreno-Salcedo also presented the Philippine Presi-

[86]

dential Unit Citation to the group in appreciation of its contributions in South Vietnam.

Unfortunately, this was not to be the last time the war touched Thanh Dien. On 16 December 1967 an estimated 200 Viet Cong guerrillas entered the hamlet. After holding a propaganda lecture and warning the new settlers to leave the community, they blew up the hamlet office, the powerhouse, and the brick home that had been built on a pilot basis. Similar, but less destructive incidents were to occur in other hamlets within the village but the Philippine Civic Action Group, Vietnam, was always quick to repair the damage.

[87]

Notes for Chapter III

1 On 1 April 1967 the PGM or motor gunboat was redesignated the PG or patrol gunboat. On 14 August 1968 the PCF or patrol craft, coastal (fast), was renamed patrol craft, inshore, although it was still called the PCF. (Return to page)

page created 18 December 2002